?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Bondage/discipline, dominance/submission, and sadism/masochism (BDSM; “kink”) are frequently pathologized as derivatives of abuse. Although the link is unsubstantiated, some kink-identified people who happen to be survivors of trauma may engage in kink, or trauma play, to heal from, cope with, and transform childhood abuse or adolescent maltreatment. The present study sought a thematic model (Braun & Clarke, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101, 2006) of trauma recovery through kink using a critical realist, inductive approach to inquiry. Participants were eligible if they had experienced early abuse, were adults, and practiced kink. Six superordinate themes were generated from semi-structured interviews with 20 participants from five countries: cultural context of healing (e.g. using BDSM norms and previous therapy to reframe kink and trauma), restructuring the self-concept (e.g. strengthening internal characteristics which had been harmed or distorted), liberation through relationship (e.g. learning to be valued by intimate others), reclaiming power (e.g. setting and maintaining personal boundaries), repurposing behaviors (e.g. engaging in aspects of prolonged exposure), and redefining pain (e.g. transcending painful memories through masochism). Notably, participants only reported retraumatizing experiences prior to learning about the structural safeguards of BDSM. Research and clinical implications are discussed by drawing on general models of trauma recovery.

Lay summary

Positive aspects of the BDSM community may help some trauma survivors, under conditions identified in this paper, transform traumatic memory. This study challenges the idea that BDSM is retraumatizing. Kink-oriented clients with trauma histories may benefit from kink-aware, affirming therapists who encourage insight between BDSM, early abuse, and recovery.

Bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadomasochism (BDSM; Ortmann & Sprott, Citation2013), as well as other forms of non-traditional, alternative sexual practices (e.g. fetishism; collectively, “kink”), have been linked to childhood abuse within some studies (Hopkins et al., Citation2016; Nordling et al., Citation2000; Yost & Hunter, Citation2012). In contrast, other studies have found no association between early abusive experiences and adulthood BDSM (A. Brown et al., Citation2020; Hillier, Citation2019; Richters et al., Citation2008; Ten Brink et al., Citation2020) and, in one study (Hughes & Hammack, Citation2020), fewer than 19% of participants linked their kink to trauma. Although it is unlikely that BDSM interests derive from abusive experience (Hillier, Citation2019; Kink Clinical Practice Guidelines Project, Citation2019), early abuse may motivate kink involvement among some people (Labrecque et al., Citation2021), while some therapists have reported that kink-identified clients with trauma histories are not unusual (e.g. Lawrence & Love-Crowell, Citation2008). Indeed, some people may use kink scenes to process their trauma (Thomas, Citation2020). Although kink “is not therapy […] it can be therapeutic” (Easton, Citation2007, p. 228). However, existing qualitative work on kink, trauma, and recovery is limited and no study has examined kink as trauma recovery systematically. Therefore, the present study uses a sex-positive framework (D. Williams et al., Citation2015) to explore how survivors of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse during childhood or adolescence use kink to heal from, cope with, and transform their trauma.

Pathology and prevalence

Kink behaviors are frequently pathologized (Powls & Davies, Citation2012; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016; Weiss, Citation2015). Popular media outlets in the United States frame members of the BDSM and kink communities as criminals (e.g. Croft, 2017), a cultural discourse of perversion perceived by 84.3% of kink-identified community members (National Coalition for Sexual Freedom, Citation2013). Scholars contend that the popular and professional stigma against BDSM and kink are reminiscent of the pathologizing of homosexuality (Coppens et al., Citation2020; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016; Simula, Citation2019). Between 2005 and 2017, a total of 808 parents contacted the NCSF, a legal advocacy organization, because their kink behaviors were entered as issues in child custody litigation (Wright, Citation2018). BDSM behaviors tend to be conflated with perversion, disorder, and criminality (Langdridge & Barker, Citation2007; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016; Shindel & Moser, Citation2011; Southern, Citation2002; Wright, Citation2018), despite mounting evidence suggesting that kink is a healthy expression of sexuality (e.g. Lawrence & Love-Crowell, Citation2008; Sprott, Citation2020; Wismeijer & van Assen, Citation2013). Thus, kink-identified clients, or people seeking therapy for a variety of concerns who happen to have recurring thoughts and behaviors that fall under the kink umbrella, may navigate stigma. Kink-based stigma erroneously suggests that BDSM interests are abnormal and perverse. Thus, the present study provides evidence to suggest that kink is not merely normative (Ten Brink et al., Citation2020), but given certain conditions, can be perceived as curative for survivors of early abuse.

Insofar as stigma is a function of ignorance, content analyses of social work textbooks (Prior et al., Citation2019), mental health counseling journals (Zeglin et al., Citation2019), and The Counseling Psychologist and the Journal of Counseling Psychology (Crowell et al., Citation2017) demonstrate that diverse sexual practices beyond stable models of sexual orientation are poorly misunderstood by generalist counselors, therapists, and psychologists. Indeed, although 70% of clinicians stated they would not target kink behavior for reduction without client consent, 48% stated that they lacked competence with this population (Kelsey et al., Citation2013). Kink-identified clients endure in-session prejudice (Hoff & Sprott, Citation2009; Kolmes et al., Citation2006; Waldura et al., Citation2016), possibly a function of poor clinical delineation between kink practices and deleterious behaviors (e.g. non-suicidal self-injury; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016), and report using session time to educate their therapists about their sexualities (Lawrence & Love-Crowell, Citation2008). Given the history of kink as trauma-derived (e.g. Yost & Hunter, Citation2012), kink-identified clients who present with trauma may anticipate provider stigma that could interfere with their trauma recovery. In summary, cultural and professional stigma may influence the trauma recovery of this population.

A systematic review estimated that BDSM interests occur in about 20% of the population among Western societies (A. Brown et al., Citation2020). Thus, mental health practitioners will likely encounter clients who engage in BDSM or kink. While clinical guidelines for providing competent care to people with kink sexualities are available (KCPGP, Citation2019), stigma remains prevalent among healthcare professionals (Sprott & Randall, Citation2017). Thus, greater empirical attention to the lived experiences of kink-identified clients who use kink as trauma recovery may increase equitable care and promote kink-aware therapy.

Early abuse

In the present study, early abuse was defined as experiences of interpersonal trauma before the age of 18 years old, including physical and sexual abuse, psychological or emotional violence (e.g. ridicule, threats, rejection, etc.), bullying, and neglect perpetrated by caregivers, sexual partners, peers, acquaintances, or strangers (World Health Organization, 2020). Synthesizing data from population-based surveys globally, Hillis et al. (Citation2016) estimated that 1 billion children (or about 50%) experienced early abuse within the past year.

Many survivors of early abuse experience negative health outcomes. From a loss perspective, early abuse “overwhelms resources” to impair healthy attachment, social and emotional competence, and community connection (Cloitre et al., Citation2006, p. 4). Among people in a community probability sample administered in Ontario, Canada (MacMillan et al., Citation2001), the odds ratio (adjusted for sex, age, and socioeconomic status) for any psychiatric disorder predicted by early abuse was 1.9, rising as high as 2.5 for major depressive disorder and 3.7 for antisocial behaviors. Early abuse is significantly associated with severe substance misuse and psychological distress in adulthood (Halpern et al., Citation2018; Min et al., Citation2007) and predicts the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Briere, Citation2002; Cloitre et al., Citation2006), with meta-analytic evidence suggesting a weak, average, weighted association between early abuse and PTSD (.14 r

.19; Brewin et al., Citation2000). In an another meta-analysis of medical outcomes (Wegman & Stetler, Citation2009), early abuse was associated with several physical health problems (d = 0.42), of which neurological (d = 0.94) and musculoskeletal (d = 0.81) issues exhibited the largest effect sizes. Moreover, evidence suggests that early abuse alters brain regions, including the areas responsible for emotion regulation and reward response (for a review, see Teicher & Samson, Citation2016).

Given the alarming prevalence of early abuse and the deleterious health outcomes, coping strategies may emerge that do not involve professional therapy, even though the latter can be effective (Briere, Citation2002). Some coping strategies, while necessary for survival as a child (Herman, Citation1992), are typically less helpful as an adult, such as defense mechanisms (e.g. denial, minimization, memory suppression, etc.), addictive behaviors, dissociation, rumination, self-blame, isolation, wishful thinking, and behavioral and psychological disengagement (Min et al., Citation2007; Walsh et al., Citation2010). Walsh et al.’s (Citation2010) review indicated that survivors also use adaptive coping strategies, such as reappraisal, reframing, achieving closure, emotional expression, seeking social support, self-discovery, discussing the abuse, releasing emotion, and managing powerlessness. Coping responses are the initial phase of posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004), an experience of positive change that flows from incredibly challenging experiences, such as early abuse. Hence, if kink transforms early abuse, then mechanisms of change may involve adaptive coping and qualities of posttraumatic growth.

Models of healing from early abuse suggest additional mechanisms of change. Establishing safety, remembering losses, and reconstructing one’s trauma story contribute to empowerment and reconnection (Herman, Citation1992). In his integrative model of trauma recovery, Briere (Citation2002) identified Herman’s factors and underscored reprocessing, gradual exposure, distress tolerance, boundary setting, and memory consolidation. In terms of recovery from childhood sexual abuse, models include meaning-making, addressing the consequences of the abuse, supportive relationships, acceptance, and reclaiming one’s life (Arias & Johnson, Citation2013; Draucker et al., Citation2011; Hitter et al., Citation2017). For example, female survivors of childhood sexual abuse developed positive sexual self-concepts through sexual exploration, relationships, bodily comfort, and the celebration of their sexualities (Hitter et al., Citation2017). Kink practices may align with these therapeutic elements thereby facilitating trauma recovery (Barker et al., Citation2007; Easton, Citation2007; Hammers, Citation2014, Citation2019; Ortmann & Sprott, Citation2013; Thomas, Citation2020), but to date, this possibility remains underexamined and insufficiently explicated.

Curative benefits of kink

Medicalized conceptualizations of kink as a derivative of early abuse assume that BDSM is essentially harmful and maladaptive (A. Brown et al., Citation2020)—a recapitulation of abuse that retraumatizes kink-identified clients. However, under certain conditions for some survivors of early abuse, kink may function as an adaptive coping response to trauma. Moreover, this pathologizing line of reasoning overlooks the experiences of community members who describe their kinks as expressions of spirituality (Baker, Citation2018; Harrington, Citation2016), avenues for social connection (Weiss, Citation2006), coping strategies for neurological dysfunction (Kaldera & Tashlin, Citation2013), methods to manage chronic illness and distress (Labrecque et al., Citation2021), and catalysts for personal growth (Sprott, Citation2020). At least 40% of kinky people use BDSM as a coping strategy for general distress (Schuerwegen et al., Citation2020). Evidence suggests that kink relationships are highly structured dynamics in which kink-identified clients may use pain play or power exchange to manage personal problems (Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016), reduce the stress hormone cortisol (Sagarin et al., Citation2009), experience altered states of consciousness (Ambler et al., Citation2017), and achieve psychological well-being (Sprott & Randall, Citation2019). Kink scenes and relationships rely on the fundamentals of the BDSM community (Cascalheira et al., Citation2021)—safewords, debriefing, aftercare, consent negotiation—to maximize benefit and to reduce risk (Langdridge & Barker, Citation2007; Ortmann & Sprott, Citation2013; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016). Given these benefits, kink seems to inhere a curative, coping, and growth-oriented potential among some community members. Thus, if kink facilitated trauma recovery, it is likely that survivors of early abuse would draw from these adaptive benefits of BDSM.

Previous scholarship indicates that at least some kink-identified clients perceive their kinks as therapeutic. Barker et al. (Citation2007) documented “healing narratives” of popular BDSM media that “many in the BDSM community see […] as reflective of their lived experiences” (p. 211). Indeed, some members of the kink community engage in kink explicitly to process past pain (Lindemann, Citation2011; Ortmann & Sprott, Citation2013). For some kink-identified clients, for instance, leather may function as symbolic permission to explore “darker aspects of [their] humanity […] in a safe and heavily structured space” (Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016, p. 36), a process known as shadowplay (Easton, Citation2007; Levand et al., Citation2019). In defining the term, Easton (Citation2007) described a punishment scene that reminded them of the physical abuse from their childhood, noting that “somehow that scene […] where I got to be storm-tossed and hurt and sad and pathetic had brought me into a profound feeling of love […] for my younger self” (pp. 225–226). In other words, kink transformed their perception of early abuse.

Contemporary authors call the kink-generated transformation of early abuse trauma play, defined here as using kink deliberately to embody individual traumatic memory (Thomas, Citation2020), or using scenes to “reenact” or to rework “trauma through BDSM” (Hammers, Citation2019, p. 491). In an essay reporting initial findings from a larger ethnographic study, Hammers (Citation2019) argued that queer participants “needed to embody, so as to expunge, their trauma” (p. 495). Hammers illustrates trauma play in the case of Ann, who used consensual non-consent (i.e. rape play) to rework her rape, reporting community witnessing, trust in her partner, somatic intensity, physical reintegration, and greater confidence. In an earlier article, Hammers (Citation2014) reported similar findings, but focused specifically on the body as the site of trauma and healing, presenting the narratives of three women who rewrote their “rape script” (p. 87) somatically to reclaim power, control, and body. Hammers illuminated the power of reworking trauma through kink while synthesizing theories of desire, abjection, and queerness to situate trauma play in a broader feminist discourse, but both articles are primarily critical (i.e. no description of analytic process, etc.) and only included cisgender women. While Hammers’ interpretations are compelling and consistent with their epistemological assumptions, there are advantages to a team-based approach to coding qualitative data (Hill et al., Citation2005; MacQueen et al., Citation1998), such as increasing confirmability and credibility by involving peer researchers throughout the interpretative process (Morrow, Citation2005). Therefore, a team-based, empirical study of kink, early abuse, and healing with greater participant diversity would complement and extend Hammers’ critical perspective.

Thomas (Citation2020), on the other hand, produced an autoethnography about their experience with trauma play. Like Easton (Citation2007), Thomas provided an intimate portrait of the trauma play experience, inviting readers into the terror, detachment, and strength necessary to submerge oneself into present pain and traumatic memory. Like the female participants in the ethnography of Hammers (Citation2014, Citation2019), Thomas (2020) reported “taking at least some of the power back” (p. 926), less shame, greater integration, and awareness of risk. Thomas concluded by commenting on the sparse research in the area of trauma play and called for systematic research. The present article seeks to answer this call.

Kink-aware therapy in conjunction with client-initiated BDSM and kink as a means to process past trauma may facilitate positive outcomes. Kink-aware is a term used to describe therapists who are familiar with and leverage BDSM, fetishism, and paraphilias in their work with kink-identified clients (Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016). Ortmann and Sprott (Citation2013) present a case study of a heterosexual couple who used skin-breaking spanking to help the male partner, Darren, process traumatic memories of his mother humiliating and beating him throughout adolescence. “The goal was catharsis,” the couple told their therapist, “and a reclamation of power by [Darren’s] consenting to the same physical […] pain from his youth—only this time as an adult […] on his terms” (p. 61). While the kink scene and requisite aftercare were perceived as curative, Darren’s presenting problems were not completely resolved (Ortmann & Sprott, Citation2013). That is, he needed the support of a kink-aware therapist to achieve clinically significant therapeutic change, suggesting that mental health practitioners who create space in session to process kink in relation to early abuse not only prevent stigma-based harm, but may improve clinical outcomes.

The present study

Using a sex-positive framework to center strength and wellbeing (D. Williams et al., Citation2015), the present study sought a pragmatic, critical realist thematic analysis of trauma recovery among kink-identified clients. A cultural context of kink-specific stigma was assumed. To our knowledge, no study has constructed a descriptive model of kink as a method of healing from abusive experiences as a minor, so we present qualitative data to address this gap in the literature, thereby answering a call for the systematic investigation of trauma play (Thomas, Citation2020). We sought an answer to the research question: how do survivors of early abuse use kink to heal from, cope with, or transform their trauma?

Materials and methods

Participants

After receiving IRB approval from New Mexico State University, criterion-based purposeful sampling guided participant recruitment (Morrow, Citation2005). That is, of the participants that contacted the researchers, an effort was made to recruit a demographically diverse sample to move the data towards maximum variation (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). A sample size of 20 was selected a priori to reach saturation (Guest et al., Citation2006; Hennink et al., Citation2017). The team used peer debriefing and analytic memos to monitor whether saturation was tenable. Interested people contacted the lead author and were eligible to participate if they (a) were over the age of 18 years old, (b) experienced abuse before the age of 18, and (c) participated in kink activities currently. Eligible participants were invited to schedule an interview if they (a) had or were willing to discuss their abusive experiences in detail, (b) had access to a mental health professional, and (c) had a reliable social support system. These final three eligibility criteria were specified because the sample was recruited from online spaces (i.e. interviewers had limited opportunity to intervene if participants had experienced a negative reaction to questions) and minimizing potential participant harm was prioritized.

Demographic features of this international sample (N = 20) are shown in . Participants ( = 27.2, SD = 7.61) were from the United States (75%), the United Kingdom (10%), Algeria (5%), Australia (5%), and Greece (5%). They lived in cities (65%), suburban developments (25%), and small towns (10%). Most had obtained a bachelor’s degree (35%) or attended some college (35%), while others held graduate (15%) or associate’s (5%) degrees, a trade school certificate (5%), or a high school diploma (5%).

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Although many abusive experiences were represented in the current sample, nearly everyone had been sexually abused (95%), including rape and molestation. A majority (65%) experienced verbal and mental abuse, such as knowing their perpetrators had escaped justice, receiving poor responses from helpers, experiencing manipulation, withstanding threats, undergoing reparative therapy, or witnessing abuse between caregivers. Over half (65%) had suffered physical abuse, ranging from spankings to torture. Nearly a third (30%) had been bullied by peers or discriminated against based on sexual orientation. A quarter (25%) reported emotional abuse, such as name calling, shaming, forced isolation, identity-based parental rejection, and abandonment. Finally, a minority (15%) reported childhood neglect.

Procedure

The team met to compose the semi-structured interview protocol and to create recruitment materials. The fourth author assembled a team of doctoral students interested in sexual diversity and trauma to compose the interview questions, drawing on kink-specific literature and work on sexual self-schema development following trauma (e.g. Hitter et al., Citation2017; Langdridge & Barker, Citation2007; Ortmann & Sprott, Citation2013). The interview protocol and recruitment materials were reviewed by two BDSM experts from NCSF prior to recruitment. Solicitations were posted to online BDSM community forums (e.g. FetLife, Reddit) after receiving permission from gatekeepers. After passing screening questions, eligible participants were invited to an interview. On the day of the interview, participants provided informed consent, were provided an opportunity to select pseudonyms, and completed their interviews over Skype or Zoom. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Seventeen participants provided written consent and three provided verbal consent, which was recorded, prior to the interview. The interview times ranged from 36–80 minutes (M = 52, SD = 12.30) and participants received a $10 Amazon.com Gift Card as compensation. The first, second, and third authors met monthly during the data collection phase to discuss their initial reactions to the participant narratives. Transcripts were analyzed with QSR NVivo. The interview protocol, transcripts, and NVivo file were stored on the Open Science Framework (OSF; Cascalheira, 2020) to support data adequacy (Morrow, Citation2005).

Philosophical assumptions

Anchored in the interpretative framework of pragmatism, we synthesized elements from critical theory to establish our philosophical assumptions (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Ontologically, we were concerned with what works for trauma survivors. From a critical perspective, we assumed that participants constructed their reality of healing within a mental health milieu in which kink is marginalized and pathologized. We describe our positionalities below and documented our reactions in reflexive journals because we assumed that our sex-positive values, professional principles as counseling psychologists (e.g. oriented toward potential instead of pathology; Gelso et al., Citation2014), and personal involvement in the BDSM community shaped the inquiry. We positioned ourselves critically to challenge the stigma surrounding kink and abuse with the aim of calling helping professionals to action.

Epistemologically, the project centered participant perspectives as the source of validity (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Our participatory role in knowledge construction relied on a critical realist approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) Given the shame and silence resulting from early abuse, “many aspects of a person’s experience and identity are left misunderstood or are not understood at all” (Cloitre et al., Citation2006, p. 290). The generation of latent themes using a constructionist approach risked moving too far beyond our participants’ experiences, possibly conveying an “arbitrary […] exercise of power” (Herman, Citation1992, p. 95) reminiscent of perpetrators who interpreted experience for the participant instead of listening. Therefore, our critical realist approach honored participant narratives by assuming that their language reflected motivation, meaning, and experience (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Delving deeper than the semantic level of meaning across participant narratives was considered inconsistent with our interpretative framework. Methodological assumptions are presented in a subsequent section.

Reflexivity

The first author is a doctoral student in counseling psychology interested in sexual subcultures and mental health. He is a White cisgender man who identifies as gay. He is involved in several ongoing research projects about BDSM, works on national teams with kink experts, and used to create and to promote BDSM events in New England. The second author is a Black cisgender woman who identifies as pansexual. She is a doctoral student in counseling psychology who specializes in minority mental health using a relational-cultural approach. Her interests broadly include social justice, spirituality, and sexual and relational well-being. The third author, also a doctoral student in the same discipline, is a White cisgender woman who identifies as pansexual. She specializes in counseling sexual and gender diverse clients. Her interests include working with individuals who have experienced trauma and using nature-based mindfulness practices within a framework of inter- and intra-relational healing. The fourth author is a licensed counseling psychologist and associate professor with extensive clinical experience working with trauma survivors. She identifies as a White, pansexual, cisgender woman. The fifth author is a White cisgender woman who identifies as bisexual. She is an undergraduate student of counseling and community psychology.

Reflexive journals, which are publicly available on the OSF (Cascalheira, 2020), also served as audit trails (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). The reflexive journals include the authors’ analytic memos, which were used to reflect on initial coding ideas after each interview and during the coding process. Analytic memos can also be found in the NVivo file. In terms of trustworthiness (Morrow, Citation2005), hosting the reflexive journals, audit trails, and analytic memos on the OSF support dependability and confirmability.

Approach to inquiry

Methodologically, we used thematic analysis to generate themes across the dataset (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2012). From a critical realist position, our focus was the generation of semantic themes using a primarily inductive analysis to provide an overall description of the data. Consistent with the six-step approach specified by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), we first noted our initial ideas while reading over the transcripts. Second, the first, second, and fourth authors generated initial codes inductively, forming a codebook that was used to code the data deductively. We retained analytical flexibility by shifting between inductive and deductive coding throughout the process. The three coders performed negative case analysis (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018) and met to discuss and collate their codes, thereby triangulating the interpretation (Morrow, Citation2005). In the third phase (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), the first, second, and fourth authors combined codes into preliminary themes and met with the third and fifth authors, who audited the themes and codes. Fourth, we reviewed the themes until consensus was reached, organized them hierarchically, and created a thematic map. During the fifth step, we defined, named, and networked our themes following best practices (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012) and sent our thematic network to participants for feedback (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018; Morrow, Citation2005). After composing the analytic narrative, participants were provided an opportunity to amend the themes or narrative. No participants requested amendments.

Results

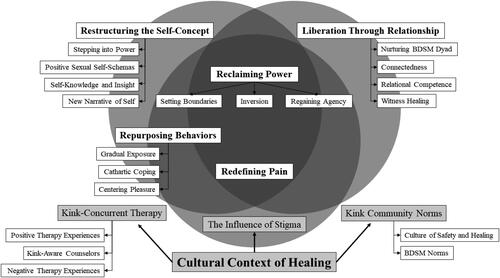

Thematic analysis generated six superordinate themes (see ). Participants healed from, coped with, and transformed their trauma in a cultural context of healing. From within this cultural context, the other five superordinate themes emerged: restructuring the self-concept, liberation through relationship, reclaiming power, repurposing behaviors, and redefining pain. Importantly, 19 participants used kink in conjunction with a package of coping, healing their early abuse with activities such as trauma support groups, yoga, meditation, and hobbies (e.g. artwork).

Figure 1. Thematic map of curative kink among survivors of early abuse. Five of the themes occurred in the cultural context of healing, which is represented by overlapping circles. These five themes occurred at the center of the three-way overlap. Thus, in the diagram, the themes are positioned for readability.

Cultural context of healing

Participants described three contextual factors that facilitated and foiled their rescripting of early abuse. Generally, kink-concurrent therapy and kink community norms facilitated healing, but negative case analysis revealed contradictory instances (e.g. therapist was not supportive for one participant). The influence of stigma functioned similarly by foiling the healing process, although a minority of participants reported no stigma (n = 5). Participants applied therapeutic lessons and language to their kink to integrate play and trauma, situating themselves in a “positive kink community” (Jen) where structural safeguards (e.g. safewords) enabled transformation, and resisting social stigma where possible. In summary, the cultural context of healing was marked by values of healing, consent, support, and intracommunity norms as well as reactions or resistance to negative experiences in therapy and the wider culture (i.e. stigma).

Before entering the cultural context of healing, however, some participants coped with comorbid conditions and ongoing trauma. Eight participants reported abuse-related mental health conditions aside from PTSD (i.e. depression, addiction), often finding symptom relief once they entered the cultural context of healing. For example, Erik, who was recovering from drug use, described the kink community as an “unofficial twelve-step program,” equating mentors with sponsors and technique-building with step work. Six participants described how their early abuse “allowed [them] to stay in abusive relationships and get treated poorly” (Luna). Ruby, for instance, did not “view sex in a healthy manner” after being molested by her brother and then raped by a partner subsequently: sex “was dread and it was anger and it was a lot of deep-rooted pain.” Like Samantha, who “was very naïve and […] didn’t know anything about BDSM” or Erik, who found himself “in situations where [he] would be victimized again,” these six participants initially lacked access to therapy and the structural safeguards of kink community norms to protect them from being retraumatized.

“Helped me gain great perspective”: kink-concurrent therapy

All participants reported simultaneous professional help or previous therapeutic gains to frame their kink experiences.

Positive therapy experiences

Sixteen participants recalled “amazing” (Tiffany) and “incredible” (Lo) therapeutic relationships. Kink-concurrent therapy, including trauma counseling, was “a lifesaver” (Anna). The “act of processing” (Faith) “laid down a foundation” (Luna) for identifying therapeutic elements in kink.

Kink-aware counselors

When participants (n = 7) had kink-aware counselors, therapy seemed to amplify the benefits of trauma play, as Samantha explained:

When I first started in the kink community […] I didn’t realize why [hair pulling] causes me so much discomfort. So, I really didn’t put two and two together until I started seeing my counselor […] because at the time I couldn’t figure out why […] then, once we started going through the stories of what happened to me when I was a kid, [my therapist] put it together.

Negative therapy experiences

Eleven participants felt “stuck” (Reddaza) with a counselor at some point, refusing to “share” about kink and early abuse even when they had “been to counseling three or four times” (Khalil). When asked why he never told his long-term therapist about his fetish for urine and feces, David stated:

I’ve had a lot of guys […] especially when I get into pig play stuff, a lot of them have, like, mega backlash and saying I need help, that I’m a psycho, that I need to be hospitalized […] But, I guess that I haven’t talked to my therapist about it because, of course, that stigma backlash.

“Is that, like, a dirty sex act?”: the influence of stigma

Negative case analysis revealed that a quarter of participants did not consider stigma as a factor in their healing through kink; nine participants felt comfortable enough to reveal their kink to friends, but only Natalie and Jen told family members. A majority of participants (n = 11) concealed their kink practices and identities from everyone except sexual partners, citing stigma and worry about association with the kink community. Maria worried whether shibari was “technically legal,” for instance, when her top posted pictures online, and described how stigma “made [her] way more afraid for [her] first event than” she “should have been.” Anticipated stigma was a concern for six participants, such as Odessa:

Kink shaming is a huge thing, especially when you tell people, like, “hey, I’m into rape play” […] because I always kind of had this fantasy and was definitely shamed for it in the past […] I felt like a crazy person, like, there must be something wrong with me if this was something I enjoyed […] a lot of my friends, like, are into bondage and impact play but I’m pretty sure that if I said to any of them that I have a rape play fantasy, they would think that I was out of my mind.

“The ethos of the lifestyle”: kink community norms

Despite negative therapy experiences and social stigma, “the type of people” (Ruby) in the kink community normalized BDSM behaviors and taught “safe BDSM practices” (Faith) which, in turn, facilitated healing from early abuse.

Culture of safety and healing

Twelve participants described people within the kink community as “very kind” because “they understand […] the gravity of sexual abuse” (Ruby). Participants described a community that accepted diverse body shapes, fostered a sense of belonging, and cared for each other beyond kink scenes. Although participants encountered newcomers who were unaware that “kink does not mean you’re just gonna give it up” (Odessa) or established members who tried to “take advantage” (Jen), they tended to perceive the community as “safe” (Reddaza), an important quality for trauma survivors. Micala said:

I think the community has been a great resource for me in coping with a lot of the shame and horrible feelings surrounding my abuse that I, you know, grew up with. And in surrounding myself with people who are friends and mentors, but who are also exceptionally open-minded and open sexually, it’s much easier to have a dialogue with them about, you know, my life and be honest about my experiences without having to feel so much of the shame and be burned by the stigma.

BDSM norms

Ten participants reported the importance of structural safeguards in facilitating a cultural context of healing. Features of BDSM practice—safewords, aftercare, references, debriefing, skill-building, mentorship, scene setting, and the “cornerstone of […] consent” (Faith)—were antithetical to memories of early abuse. For example, Khalil, whose abusive stepmother “wouldn’t stop no matter what [he] said,” having a safeword became an integral part of his relationship with his partner.

“The confidence is stemming from something”: restructuring the self-concept

Drawing on kink-concurrent therapy and kink community norms, all participants strengthened internal constructs, which had been harmed, exploited, or distorted during early abusive experiences.

Stepping into power

Through kink, participants were able to gain a sense of confidence and esteem, standing in their truth and authenticity. Like Faith, for instance, who experienced a “general boost in confidence,” participants (n = 9) described aspects of their lives where they experienced an increased feeling of self-assurance. Kahlil who struggled with insecurities “became much more confident” through kink play with his partner. Lil shared how during kink play, “you kind of like relinquish all your insecurities,” helping her build her “self-worth.” Similarly, Luna who often felt undeserving, found worth beyond her physical appearance:

I have spent so long not seeing myself, […] just not acknowledging that I am a being. And now, I’ll look at myself in the eyes, I can acknowledge, like right now I am breaking out pretty bad […] and I’m able to look in the mirror and acknowledge that I don’t like that, and that doesn’t dictate my worth. […] I don’t feel that way every single day, all day, and I never felt that way before. And so, I’d say there’s more positive, much more positive thoughts and feelings about myself now.

I can’t lose weight like a normal person. I eat like a piece of cake and I can gain like 20 pounds [….]. So, I called my parents up. I called my brother up and I told him flat out “if you make any comments about my weight this Christmas […] I’m going to beat your ass […] I’ve had enough.” […] I called my mother and I told her the same thing […] I said, “I’m thirty years old and enough is enough. I’ll eat what I want, I’ll weigh as much as I want to weigh—it’s none of your business” […] so she said one or two comments but not as much as she did before, and I think she’s getting the hint that, you know, I am who I am and that’s going to be it. I’m not going to live the rest of my life with her putting me down, so I have to do something.

Positive sexual self-schemas

As the participants began stepping into power, 12 of them began to rework their sexual self-schemas, originally tainted by their abuse experiences (n = 8), into more positive self-images. Sex became enjoyable. Whereas Ruby’s early abuse experiences had taught her to view herself as “a masturbation tool for guys,” kink allowed her to build intimacy and connection with her partners, eventually allowing her to “not see [her] self as an object” in sexual situations. For sexual trauma survivors like Lil, engaging in nonsexual BDSM practices helped reshape her views of sex:

And I think taking away the penetrative aspect of it is what helps me heal, or at least change my perception of sex into a positive light.

Self-knowledge and insight

Participants (n = 11) described the new learnings about themselves that had come about from engaging in kink. Growth through kink helped four participants understand their sexuality, something Tiffany experienced some rigidity around when she was younger:

I think that my relationships have definitely evolved over time. I used to be a serial monogamist back in my late teens, early twenties. I’m now in my mid-, my late-early-thirties (laughter) […] and I’m now in mostly open poly relationships. I used to be in only heterosexual relationships, and now I’m in multigender relationships.

New narrative of self

By stepping into power and gaining new self-knowledge and insight, eight of the participants were able to develop a new narrative of themselves. For Lil, whose initial abuse experiences involved “weight and other things like that,” engaging kink helped her learn that she is “desirable.” Natalie came to “embrace” her experience of rape stating, “I am who I am because of this and I wouldn’t change who I am.” Micala shared how her self-concept was radically restructured through kink:

I think it’s fundamentally changed my conception of myself, as a sexual being, and as a trauma survivor and the intersection between those two things.

“Simply being there for me”: liberation through relationship

Within the culture of safety and healing, 19 participants allowed themselves to be valued, found themselves mattering to others, deepened their interpersonal effectiveness, and rescripted shame through relationship.

Nurturing BDSM dyad

The unique relationships and dynamics formed through engaging in kink served as a vessel for healing for most of the participants (n = 16). For Jen, when things were “under [her] control” as a “master/dom [… she] knew everything [would] be safe” and she could “create that safety for [… her] partner.” Samantha, who often felt unprotected as a child, was able to “feel safe and secure” as a “little” in her relationship. By stepping into power, participants were able to choose to take on roles that gave them what they needed, because they (n = 7) were able to put their “trust into someone” (Ruby). David stated:

Like, I am a very submissive person, but for the right dom or dominant person, someone who I know will take care of me and won’t at all mistreat me or confuse me, then I can feel safe and secure, as opposed to growing up: I never felt safe and secure in both my home environment and the environment I was living in.

Even though it was just strictly BDSM, no actual sexual relationship almost […] it was still some kind of intimacy, and I’ve never been so connected with anyone in my entire life as I am with my boyfriend right now. And I’ve never been just so comfortable being myself […]. I’ve never felt so safe in a relationship […] I’ve done the most experimenting and the most crazy stuff and the most, like, the weirdest stuff I never thought I would be into, I never thought I would try out.

Connectedness

The nurturing BDSM dyads gave space for half of the participants to build rich and deep connections. Jen, for instance, felt liked she finally had “a community to rely upon.” Ruby shared she could be “honest” and “not feel ashamed” in her relationships. Odessa elaborated on the supportive networks she had built in the kink community:

I’m still definitely working on the healing part, but I do think that these kink relationships have helped and, if nothing else, I’ve made friends I can talk to about other stuff. So, one of my really good, like probably my first friend—in-person friend—in the kink world, I text him whenever I’m feeling crappy, you know. He does the same […] I don’t talk to my [vanilla] friends about the sexual abuse […] I went through when I was a kid […] so [the kink community] gives me, like, outside people to talk to […] about it.

Relational competence

Participants (n = 8) described experiences of increased vulnerability and openness through BDSM, gaining tools to better articulate their needs. Jen, who dropped out of high school due to abuse and was “very shy,” learned how to “communicate with people effectively” through interactions with the kink community. Micala’s ability to communicate her “wants,” “needs,” and “desires” improved. Maria highlighted some of the distinctions between kink community norms around communication and communication in “vanilla relationships”:

I think that the communication tools are so much for use, like, the way that people talk to each other is so different. And it, like, it acknowledges each other as human beings, as opposed to the weird dichotomy that tends to happen a lot of the time in vanilla relationships, where it’s like you’re playing a game and you’re, like, not really telling each other what you want.

Witnessing healing

As some participants (n = 6) moved through their journeys of survival and growth, witnessing healing was an important part of their process of liberation. Erik found it “rare to meet somebody in the BDSM community who hasn’t experienced […] trauma.” Samantha described how, through hearing other people’s stories of abuse, she slowly began to heal from hers:

It has just helped. Just by looking at, scrolling at pictures, or even articles that people have written about their healing. And that helps me, you know. They have talked about different things that have happened to them and that has helped me heal as well.

“All of a sudden […] I had more control”: reclaiming power

Whereas early abuse left them disempowered, kink enabled 19 participants to specify their limits, to invert concepts of power, and to restore their autonomy.

Setting boundaries

Thirteen trauma survivors drew on BDSM norms to learn how to set and to honor their personal boundaries. Safewords, for example, enabled five participants to reclaim bodily integrity, something Khalil lacked with an abusive stepmother:

My stepmother wouldn’t stop no matter what I said. But with me and my partner, we can get a bit aggressive, but we always have safewords that we can say, and so that one party would stop instantly and check on the other.

Inversion

Eleven participants inverted power to reclaim it. Whereas Ashely’s abusers “always had the power over [them],” kink transformed their victimized memories by providing a new, corrective experience—“now [… they had] the power over what happens.” For trauma survivors like JB who assumed the dominant role, power play inverted the history of herself as victim:

[Being a dom] was like stepping into myself for the first time. I think the thing that I needed the most from being the dom was the ability to choose when, where, and why with no questions asked […] a lot of it, unfortunately, seems to be a fantasy or fetish for men. And, you know, I don’t really want to partake in that unless they want to actually submit themselves to my control.

While I know that, ultimately, I’m still in control, I’m also letting—I don’t know—I don’t have to be the one who’s thinking about every single thing. I can just kind of let my mind go. I don’t have to plan out everything.

Regaining agency

By setting boundaries and engaging in power inversion, half of the participants regained their sense of autonomy. For Lil, who still “shudders when men look at her […] a certain way,” engaging in kink “empowered” her to “demand [her] respect.” JB summarized how greater power transcended kink-specific events:

A lot of it, I think, has to do with the fact that I—that it’s, like, it’s my way to regain agency. That was kind of, like, taken from me when I was younger, so in a way, that’s why it’s appealing. Just getting really embedded in it, as much as I felt I could or wanted to, brought out in me so much more of a dominant person in my day-to-day life

“I was taking it back”: repurposing behaviors

Eighteen participants described reworking their early abuse through processes that resembled prolonged exposure and behaviors that induced positive affect.

Gradual exposure

Through kink, participants slowly approached frightening stimuli that, before entering the cultural context of healing, could trigger adverse reactions. Like Lo, for instance, who experienced fewer flashbacks during kink scenes, participants (n = 10) described a continuum of limits, which were related to early abuse. When Faith had their hard limit crossed (i.e. punching), they “curled up for like an hour having a bad flashback.” Kuri recalled partners who disclosed, “I don’t do X because it reminds me of X when I was a kid.” Erik, who was tortured as a child, sought to push his limits with safe partners in a pre-negotiated “scene.” That is, the nurturing BDSM dyad heals, in part, because it served as a container to “go […] into the unknown” (Natalie). Tiffany stated:

What helped me work through my childhood molestation the best wasn’t going to psychotherapy. It wasn’t talking to friends and family about it. It was roleplaying it with a man that I was in love with, and it was the most twisted but romantic roleplay ever. But it really helped me.

You can start out on the little end […] what you’ll allow, like, stuff that doesn’t bother you […] You can start out with the things that don’t bother you at all, and then slowly work towards little things that, I guess, trigger you […] something that […] hurt at some point [… My husband and I have] worked with spanking. I was not a big fan of it at first […] because of issues with a broken tailbone with […] my mother beating me with a paddle. So, we’ve worked on that. I’m more—I didn’t like the hair pulling when I first started with any of it because of what my mother used to do to me, but now that I’m—now that I can explore with my sex and my sexuality, I’m a big fan of hair pulling now (laughing) […] not a problem for me at all anymore.

Cathartic coping

Participants (n = 9) described experiencing catharsis, using kink to relax, and coping with negative emotional states through BDSM. Tiffany reported that kink “unclouds your brain,” which was useful for managing comorbid mental health issues related to her early abuse. Ashley “explored” their girlfriend more, which was different from “walking on eggshells” as a terrified child, too worried about disparaging criticism or unexpected assaults. Exploring kink allowed participants to be present with their bodies, focusing on their pleasure.

Centering pleasure

Centering pleasure was an important mechanism of repurposing behavior (n = 8). When Khalil’s partner “tied [him] up,” he “felt a memory” but noticed how his present-moment experience was “nice, intimate” instead of frightening, like his early abuse. Whereas Ruby’s sexual assaults left her feeling objectified, the pleasure of rope suspension enabled her to experience being wanted without coercion. She said: “I’m starting to recognize the difference between someone seeing my soul and […] someone just seeing me as a sex object.” For Micala, the “pleasure and joy” of kink created “a better reality” from the one she remembered. David, who was teased for his “body odor” as a child began to “really like [his] man-smell” through raunch play. Odor was no longer a source of humiliation. Ashley described how, through pleasure, they salvaged their body (i.e. once a target of violence) and behavior (i.e. once the perceived cause of violence) from abuse-laden memories:

I was taking it back. That this could be enjoyable. And I was not letting my past do anything with it. I was not letting my past interfere with it.

“It’s about caring about your pain”: redefining pain

Ten participants reported how pain play changed their perception of early abuse. Through kink, Ashley learned that she enjoyed pain—that it was not the actual pain that came with her abuse experiences that bothered her, it was the “humiliation.” While Ashley liked to receive pain, Erik who experienced physical abuse preferred to give pain as an “outlet” to “cope with [his] trauma.” Natalie, a masochist, used BDSM pain to transcend her painful memories. After a scene, she noted, “you have a need to care about the pain […] and care for yourself.” Exploring pain outside the context of abuse allowed participants to figure out their relationship with and understating of pain.

Discussion

The present article was neither interested in whether early abuse exhibited an association with kink practices in adulthood (Hillier, Citation2019; Hopkins et al., Citation2016; Richters et al., Citation2008) nor whether kink was healing for everyone who engages it (Barker et al., Citation2007). Rather, it is the first study to seek a model of trauma recovery among kink-identified clients who use kink to heal from, cope with, and transform their early abuse. Six superordinate themes were generated from 20 semi-structured interviews, a process of trauma recovery we define as curative kink. Once this sample of survivors entered a cultural context of healing, they used previous or ongoing therapeutic insights and subcultural norms of the BDSM community to resist stigma. From within this cultural context of healing, participants transformed their trauma through kink by restructuring the self-concept, achieving liberation through relationship, reclaiming power, repurposing behaviors, and redefining pain. Delineation of the mechanisms of trauma recovery for kink-identified survivors of early abuse is the central contribution of this study with implications for generalist clinicians, sex therapists, and researchers of human sexuality.

Unlike case studies that frame BDSM as retraumatizing (e.g. Southern, Citation2002), results from our systematic investigation indicated that kink may be a conduit of posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004) through the iteration of abuse analogues, behaviors which, under the conditions identified herein, are gradually divorced from their traumatic context. Participants experienced kink as a form of active healing (Arias & Johnson, Citation2013; Walsh et al., Citation2010) in which elements of scenes, roles, and behaviors not only “set the process of growth in motion,” but “may accompany the enhancement and maintenance of posttraumatic growth” (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004, pp. 12–13) because kink evoked manageable levels of distress reminiscent of early abuse. Without the context of kink, stimuli related to abuse can overwhelm a survivor’s capacity to regulate emotion (Briere, Citation2002). However, our results provided evidence that kink behaviors disrupt the conditioned response to environmental cues that were originally threatening. Instead of retraumatizing participants, kink rescripted elements of the traumatic event. For participants endorsing the repurposing behaviors theme, for example, a “traumatic memory [… was] activated” (i.e. Samantha remembered her mother pulling her hair) “in the presence of information incompatible with that fear structure” (i.e. she experienced safety and control instead of danger and boundary violation; Briere, Citation2002, p. 194). Since all participants experienced some level of posttraumatic growth through kink, our results align with contemporary research to suggest that kink is not a maladaptive coping response to early abuse (Ten Brink et al., Citation2020).

Indeed, many of the adaptive coping strategies used by survivors of childhood abuse were evident in participant narratives. For example, during cathartic coping, participants reduced overwhelming feelings (Briere, Citation2002; Walsh et al., Citation2010) and, during liberation through relationship within a culture of safety and healing, participants sought social support and discussed their abuse (Draucker et al., Citation2011; Hitter et al., Citation2017; Walsh et al., Citation2010). From a loss perspective (Cloitre et al., Citation2006), the emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems flowing from early abuse were transformed by centering pleasure, redefining pain, greater connectedness, and improved relational competence, thereby increasing this sample’s functional capacity to cope. Furthermore, from an attachment perspective (Bowlby, Citation1983; Ten Brink et al., Citation2020), caregivers who become abusers rupture a fundamental process, blurring the roles of “protector and perpetrator” (Cloitre et al., Citation2006, p. 13). The nurturing BDSM dyad seemed to repair this rupture within a cultural context that empowered the early abuse survivor, shifting power to the survivor (i.e. safewords, consent) and amplifying the protector role of the partner (i.e. aftercare, consent honoring, debriefing), at least among participants who preferred submissive roles. For dominant partners like Faith or JB, becoming the protector transcended the role of victim; power to protect a submissive partner generalized to protecting the self (e.g. greater agency, confidence). Thus, abuse perpetration was inverted, defanged, and rescripted to transform the ways in which survivors saw themselves in relation to interpersonal others. Their sexual self-schemas became positive through relational healing (Hitter et al., Citation2017) and, by extension, internal characteristics grew in strength (i.e. a crucial process in trauma recovery; Arias & Johnson, Citation2013).

Our findings are consistent with the “three transformative aspects of BDSM” (Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016, p. 91): relationships, community, and pain. First, participant narratives evinced that the nurturing BDSM dyad functioned as an interpersonal container characterized by trust, honesty, openness, and care (Dancer et al., Citation2006; Langdridge & Barker, Citation2007; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016). Within this container, participants seemed to consolidate their trauma recovery (Briere, Citation2002). Like J. Williams (2017), whose content analysis revealed how two BDSM bloggers learned to appraise their bodies positively through relationships with their kink partners, participants in the present sample used the nurturing BDSM dyad to challenge narratives about their bodies as contemptible or shameful. Second, as observed in other work (A. Brown et al., Citation2020; Ortmann & Sprott, Citation2013; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016; Weiss, Citation2006), the kink community enabled social support while socializing participants into the fundamentals of BDSM practice (Cascalheira et al., Citation2021), thereby allowing this sample to explore their trauma as risk-aware community members (Thomas, 2020; D. Williams et al., Citation2014). The community element paralleled the supportive relationships phase in the Arias and Johnson (Citation2013) model of healing from childhood sexual abuse. Finally, participants in the present sample reported the transcendent quality of pain, which is consistently identified in the literature as a motivator for BDSM involvement (Labrecque et al., 2021; Langdridge & Barker, Citation2007; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016).

Departures from previous studies

Results depart from aspects of the BDSM literature, trauma recovery models, and emergent work on trauma play. Regarding the general literature on kink, the spiritual component of BDSM reported in previous work (Ambler et al., Citation2017; Baker, Citation2018; Harrington, Citation2016) was underdeveloped in the present study. Only one participant (Ruby) mentioned spirituality, although this may have been a byproduct of the interview protocol which did not assess spirituality directly. Given the importance of spirituality in trauma recovery (Arias & Johnson, Citation2013; Draucker et al., Citation2011; Herman, Citation1992; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004), the present thematic model may require additional qualitative work to account for this dimension. According to sex therapist Gina Ogden (Citation2018), however, the spiritual dimension of sex can be conceptualized as experiences of connection. From this perspective, the theme of liberation through relationship may express this spiritual dimension. Nonetheless, future studies would advance knowledge about trauma recovery through kink by aiming an empirical lens to this important dimension.

Aside from the sparse presence of spirituality, other divergences from trauma recovery models were observed. For example, the present model is not stage-like (Arias & Johnson, Citation2013; Draucker et al., Citation2011), even though future studies may discover a phased process. Whereas the current themes reflect most of the constructs of trauma recovery identified by Arias and Johnson (Citation2013), thereby supporting the credibility of our thematic model (Morrow, Citation2005), the grappling stage of the Draucker et al. (Citation2011) model was less prominent. Few participants focused on the period between the abusive incident(s) and the recovery behaviors. There was also no evidence of making meaning from intergenerational abuse and the present model does not outline enabling factors that promote movement through trauma recovery (Draucker et al., Citation2011).

The present findings diverge from previous qualitative work on kink and trauma in two important ways. First, although kink-related healing was active for these participants, there was limited evidence of deliberate engagement in BDSM to evoke traumatic memory, which characterizes trauma play (Thomas, Citation2020). For example, Thomas described setting up scenes that would arouse specific memories, whereas in the current study, most participants recognized the curative potential of kink post hoc (e.g. Tiffany after her roleplay). The clearest examples of deliberate trauma play came from Micala and Samantha, but neither woman defined their behavior as such. Second, aside from the redefining pain theme, there was less emphasis on the corporeal or somatic dimension in this sample, even though ethnographic studies on BDSM and trauma emphasize the body (Hammers, Citation2014, Citation2019). Both departures could be artifacts of the interview protocol because we neither mentioned trauma play nor delved into the somatic dimension. Consequently, the scope of transferability may be limited to cognitive, affective, and interpersonal dimensions of trauma recovery.

Implications

The present investigation contributes to sex research and kink studies. A growing body of evidence describes the positive benefits of kink participation (e.g. A. Brown et al., Citation2020; Sprott, Citation2020; Sprott & Randall, Citation2017), to which this study adds. Although sexologists arguably have known about healing narratives and kink for over a decade (Barker et al., Citation2007; Easton, Citation2007), no thematic model of trauma recovery through BDSM has emerged. If applied to existing examinations of kink and coping (Kaldera & Tashlin, Citation2013; Labrecque et al., 2021; Schuerwegen et al., Citation2020), the model suggests underexamined constructs, such as prolonged exposure. Although the gradual exposure subtheme of repurposing behaviors has been suggested conceptually in a recent clinical guideline article (Levand et al., Citation2019), this construct lacks systematic investigation in BDSM studies. Given the large effect size of prolonged exposure in clinical research (Powers et al., Citation2010), perhaps the process of gradual exposure is a driver of kink-related coping with distress beyond trauma. Additionally, the prominence of cultural context within the present study aligns with the emphasis on contextual determinants of sexual behaviors that is gaining traction in sex research (R. D. Brown & Weigel, Citation2018; Wignall & McCormack, Citation2017). While individual differences and dispositional attributes are important levels of analysis, without the contextual substrate identified by participants in the present model, it is unclear whether kink would have emerged as transformative. Thus, future research into kink sexualities may benefit from greater attention to contextual influences.

Clinically, these results call for kink-aware training and support existing clinical guidelines. Becoming a kink-aware helping professional requires examining one’s sexual attitudes, learning about the community, and seeking supervision from other competent professionals (Pillai-Friedman et al., Citation2015; Shahbaz & Chirinos, Citation2016). Given the historical backdrop of abuse as the etiological source of BDSM interests (e.g. Nordling et al., Citation2000; Southern, Citation2002), clinicians may be reluctant to support kink-identified clients who engage in trauma play, although such an intervention was perceived as helpful for some of our participants. The present data move beyond cautioning professional helpers to reexamine conceptualizations of BDSM as retraumatizing (e.g. Kolmes et al., Citation2006). Instead, we advance the idea that, given a cultural context of healing, kink behaviors could be leveraged to help some kink-identified clients process their early abuse. In training programs, these results should be combined with other explorations of trauma recovery through kink (Hammers, Citation2014, Citation2019; Thomas, 2020) to enhance cultural competence with kink-identified clients (Lawrence & Love-Crowell, Citation2008; Pillai-Friedman et al., Citation2015) and to broaden the interventional repertoire of therapists (Levand et al., Citation2019).

However, kink was not examined as an intervention per se in the present study. Notably, participants perceived and interpreted their kink behaviors as curative. Strictly speaking, our data provide evidence that, among participants with the conditions identified in the present article, kink behaviors were perceived as transformative, but at this point, we cannot claim that kink directly stimulated healing. Nonetheless, while working with kink-identified clients who happen to be survivors of early abuse, clinicians should consider how BDSM could be used to facilitate insight and posttraumatic growth.

As similar evidence accumulates, the present study could be used to support the expansion of the fourth clinical guideline in work with kink-identified clients (i.e. kink is not necessarily a response to trauma; KCPGP, Citation2019). Presently, these results provide evidence for guideline 3 (e.g. kink is not pathology), guideline 9 (e.g. kink can lead to healing, growth, empowerment), guideline 16 (e.g. stigma influences kink experience), guideline 18 (e.g. stigma influences the therapeutic process), and the set of training guidelines, 20 to 23.

Limitations & future directions

Methodological limitations qualify the interpretation of results. In terms of data integrity, three limitations are apparent. First, use of an online sample may have resulted in participants whose participation in kink is different from people who live in larger urban areas with many dungeons, munches, or BDSM conventions. Recruitment from these community spaces may have strengthened participant diversity, although the overrepresentation of White, educated, urban, and rich participants may have remained a limitation. Additionally, although our data expand the demographic diversity found in previous work on kink and trauma play (Hammers, Citation2014, Citation2019; Thomas, Citation2020), the current sample still presents challenges to generalizability. Most participants were White, identified as sexual or gender minorities, had access to mental health services, and were under 40 years old. As such, participant experiences with kink, BDSM, stigma, and healing may not be typical of abuse survivors from other demographic categories. For example, overreporting positive therapeutic experiences may have occurred given that eligibility criteria required access to a therapist. Thus, an examination of our thematic structure among community members without access to mental health services would be an important next step and, in general, further study with a more varied sample is recommended.

Second, recruitment materials solicited people who perceived themselves as using BDSM for trauma recovery and limited eligibility to participants with access to therapy. We do not know how other survivors of trauma, who also participate in kink without linking their behaviors to traumatic memories, understand their experience. Stated differently, framing kink behavior as trauma recovery is not without its problems, such as suggesting that the mechanisms of change identified presently are the only ways to heal through kink or that healing is the primary motivation for BDSM engagement (Barker et al., Citation2007). Neither conclusion is the intent of this study. It is possible that trauma survivors engage in kink without any attributable interest to early abuse, finding recovery outside of scenes. Moreover, although limiting eligibility to participants who had access to therapy and social support minimized harm, this ethical strategy likely narrowed our sample (e.g. low-income participants with limited resources for therapy, people who tried BDSM but were retraumatized). In summary, these qualities of the data limit the scope of transferability.

Third, retrospective reports of early abuse can entail an appreciable rate of false negatives (for a review, see Hardt & Rutter, Citation2004). Although this thematic model suggests a causal process, it is important to note that the claim of kink as curative for the current sample is based on participant perceptions. Our approach to inquiry assumed validity in participant narrative, which is consistent with a trauma-informed approach to counseling (Herman, Citation1992), but retrospective recall may have introduced bias into these data (e.g. participant misremembering abuse severity). An associated limitation is that participants may have attributed healing, coping, and transformation to kink when, chronologically, other factors accounted for a greater proportion of the variance in trauma recovery. After all, 19 participants engaged in other coping behaviors that they perceived as helpful. Additionally, since it was a requirement for participants to have seen a mental health professional, it is unclear whether kink would promote trauma recovery among early abuse survivors with less access to healthcare. For example, pain is an important somatization element in the present and previous work (Hammers, Citation2014, Citation2019), but it unclear how pain promotes embodiment differently than other behaviors (e.g. yoga; Rhodes, Citation2015). Thus, if the present thematic model was tested quantitatively, access to coping resources aside from BDSM would be important covariates or moderators.

In addition to using different data sources or a quantitative approach to extend these findings, future studies could use a different qualitative approach to enrich scientific understanding of BDSM as trauma recovery, especially since the knowledge base is limited. For example, although our thematic analysis enabled some attention to process, a grounded theory design would yield a superior investigation of the antecedents and consequences of curative kink. Relatedly, this study did not fully explore the intentionality of participants engaging in kink for trauma recovery, and intentionality is a key element in shadowplay (Easton, Citation2007) or trauma play (Thomas, Citation2020). Thus, future investigators might apply thematic analysis, phenomenology, or consensual qualitative research to these phenomena specifically.

Although this study is an important contribution to study of kink and trauma, the area is rich for future research. We did not, for instance, investigate closely related concepts, such as cultural trauma. Future studies could examine the ways in which kink enables minority participants to challenge and to heal from racial and heteronormative trauma (Bauer, Citation2008, Citation2018; Kuzmanovic, Citation2018). Indeed, reclaiming power may manifest in nuanced ways in this context. Additionally, a comprehensive analysis of age differences was beyond the scope of the present project even though the age at which people experience abuse may have profound consequences on symptoms, development, and function (e.g. Van Nieuwenhove & Meganck, Citation2019). Investigators could examine whether the processes identified herein replicate across people who experienced abuse in early childhood versus late adolescence. For example, perhaps earlier abuse is processed among some survivors with unique kink practices, such as dark ageplay.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Cory J. Cascalheira, Yelena Salkowitz, and Tracie L. Hitter; Methodology: Cory J. Cascalheira, Yelena Salkowitz, and Tracie L. Hitter; Formal analysis and investigation: all authors; Writing: Cory J. Cascalheira, Ellen E. Ijebor, and Yelena Salkowitz; Writing—review and editing: all authors; Funding acquisition: Cory J. Cascalheira; Resources: Tracie L. Hitter; Supervision: Tracie L. Hitter.

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors have complied with all ethical standards.

Consent

All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Data transparency

Data, reflexive journals, and audit trails are available upon request and can be accessed from the Open Science Framework, located at: https://osf.io/ay685/.

Ethics approval

The Institutional Review Board of New Mexico State University approved this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Susan Wright and Russell J. Stambaugh of the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom for their helpful feedback on the interview guide and recruitment materials; Andrew Pari of Sexual Assault Awareness for his feedback on the thematic model and suggestion to explore prolonged exposure; Amber Johnson and Aurora Tomberlin for their transcription; and the caretakers of FetLife and the moderators of Reddit for their gracious support during the recruitment phase. Finally, we thank the editors and anonymous peer reviewers whose feedback has improved this manuscript substantially.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on the Open Science Framework, located at: MASKED FOR REVIEW.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interest to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by the Love of Learning Award, a $500 grant awarded by Phi Kappa Phi to Cory J. Cascalheira.

References

- Ambler, J. K., Lee, E. M., Klement, K. R., Loewald, T., Comber, E. M., Hanson, S. A., Cutler, B., Cutler, N., & Sagarin, B. J. (2017). Consensual BDSM facilitates role-specific altered states of consciousness: A preliminary study. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000097

- Arias, B. J., & Johnson, C. V. (2013). Voices of healing and recovery from childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 22(7), 822–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2013.830669

- Baker, A. C. (2018). Sacred kink: Finding psychological meaning at the intersection of BDSM and spiritual experience. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 33(4), 440–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2016.1205185

- Barker, M., Gupta, C., & Iantaffi, A. (2007). The power of play: The potentials and pitfalls in healing narratives of BDSM. In D. Langdridge & M. Barker (Eds.), Safe, sane and consensual: Contemporary perspectives on sadomasochism (pp. 197–216). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bauer, R. (2008). Transgressive and transformative gendered sexual practices and White privileges: The case of the dyke/trans BDSM communities. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 36(3/4), 233–253.

- Bauer, R. (2018). Bois and grrrls meet their daddies and mommies on gender playgrounds: Gendered age play in the les-bi-trans-queer BDSM communities. Sexualities, 21(1–2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460716676987

- Bowlby, J. (1983). Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748

- Briere, J. (2002). Treating adult survivors of severe childhood abuse and neglect: Further development of an integrative model. In J. E. B. Myers, L. Berliner, J. Briere, C. T. Hendrix, T. Reid, & C. Jenny (Eds.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (2nd ed., pp. 175–203). Sage Publications.

- Brown, A., Barker, E. D., & Rahman, Q. (2020). A systematic scoping review of the prevalence, etiological, psychological, and interpersonal factors associated with BDSM. Journal of Sex Research, 57(6), 781–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1665619

- Brown, R. D., & Weigel, D. J. (2018). Exploring a contextual model of sexual self-disclosure and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 55(2), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1295299

- Cascalheira, C. J. (2020). Curative kink. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AY685

- Cascalheira, C. J., Thomson, A., & Wignall, L. (2021). A certain evolution’: A phenomenological study of 24/7 BDSM and negotiating consent. Psychology & Sexuality, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1901771

- Cloitre, M., Cohen, L. R., & Koenen, K. C. (2006). Treating survivors of childhood abuse: Psychotherapy for the interrupted life. The Guilford Press.

- Coppens, V., Ten Brink, S., Huys, W., Fransen, E., & Morrens, M. (2020). A survey on BDSM-related activities: BDSM experience correlates with age of first exposure, interest profile, and role identity. Journal of Sex Research, 57(1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1558437

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Croft, J. (2017, July 5). What we know about the FetLife fetish site. https://www.cnn.com/2017/07/04/us/fetlife-illinois-kidnapping-suspect/index.html