Abstract

Sexual satisfaction (SS) may be an important predictor of broader quality of life (QOL; e.g. life satisfaction, etc.). However, past studies have rarely examined moderating variables of this association. The current study examined gender differences in the association between QOL and satisfaction with both intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of sex (e.g. one’s physical pleasure vs. quality of emotional connection with a partner). 188 adults completed measures of SS and QOL. SS was moderately correlated with a range of QOL outcomes. Satisfaction with intrapersonal aspects of sex was generally a stronger predictor of QOL for men whereas satisfaction with interpersonal factors was sometimes more predictive of QOL in women. Implications regarding the broader impact of sexual well-being are discussed.

Lay Summary:

Men and women may differ regarding how sexual satisfaction is associated with quality of life. Satisfaction regarding internal components of sex like physical pleasure may most important for men, while satisfaction with interpersonal components of sex like emotional connection may be most important to women.

Sexual satisfaction (SS) has been defined as an “affective response arising from one’s subjective evaluation of the positive and negative dimensions associated with one’s sexual relationship” (Byers, Citation1999, p. 98). SS has been shown to be distinct from a number of related constructs such as sexual function (e.g. sexual desire, frequency of orgasm; Bancroft et al., Citation2003) and sexual distress (e.g. anxiety, shame, anger regarding one’s sexual experiences and functional problems; Stephenson & Meston, Citation2010). Given that sexual activity has been reported as important across cultures (Laumann et al., Citation2006), it is unsurprising that SS has been a common focus of researchers over the past few decades (Buczak-Stec et al., Citation2019).

A number of studies have suggested that SS is not only important in and of itself, but that it also predicts various aspects of broader (non-sexual) quality of life (QOL; e.g. life satisfaction, mental health, happiness, and relationship satisfaction; Flynn et al., Citation2016; Kashdan et al., Citation2018; Ryan & Deci, Citation2001). For example, the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors (Laumann et al., Citation2006) suggested that, across cultures, those reporting high levels of SS also reported higher overall life satisfaction. This finding is mirrored by other studies with male (e.g. Thompson et al., Citation2005) and female (e.g. Stephenson & Meston, Citation2015) samples. In addition to life satisfaction, SS has repeatedly been shown to be associated with mental health (e.g. Atlantis & Sullivan, Citation2012; Nicolosi et al., Citation2004; Vanwesenbeeck et al., Citation2014) and relationship satisfaction (e.g. Byers, Citation2005; McNulty et al., Citation2016).

However, while it is established that SS is associated with quality of life on average, we have limited understanding of the nuances of this link. The strength of association between SS and QOL varies widely across studies, with some effects quite weak (e.g. β = .08 between life satisfaction and sexual satisfaction; Buczak-Stec et al., Citation2019), and others moderate-to-strong (e.g. r = .48 between life satisfaction and sexual satisfaction; Neto & Pinto, Citation2015). There also may be important individual differences that moderate the association between SS and QOL (e.g. Stephenson & Meston, Citation2015). Furthermore, SS and QOL may consist of multiple, potentially distinct components, and the strength of the association between the two may differ depending on which components are considered. In other words, some aspects of sexual satisfaction may be more strongly associated with QOL for some people than for others.

One individual difference that may be important in moderating the link between SS and QOL is gender. While a number of past studies report consistency across genders in terms of the link between SS and QOL (e.g. Buczak-Stec et al., Citation2019; Heiman et al., Citation2011; Henderson-King & Veroff, Citation1994, Mark et al., Citation2014), others have reported potentially important differences between men and women. For example, in the area of mental health, Wylie et al. (Citation2002) found that, among individuals with psychiatric disorders, a larger proportion of men also reported low sexual satisfaction (48%) as compared to 36% of women. Flynn et al. (Citation2016) similarly demonstrated a stronger correlation between SS and diagnoses of anxiety and depression in U.S men (B = −16.31) than in U.S women (B = −0.33). Laumann et al. (Citation2006) found that, in older adults from Western and European Countries, higher sexual satisfaction was linked with lower rates of depression, but that this correlation was stronger in men (B = −.103) than women (B = −.058). However, other studies have found little gender difference in the strength of association between SS and mental health (e.g. Heywood et al., Citation2018; Morgan et al., Citation2018).

The pattern of findings tends to be similarly inconsistent in research focusing on other aspects of QOL. A number of studies suggest that men may exhibit slightly stronger correlations between sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction. For example, Penhollow et al. (Citation2009) assessed older adults and found that the male partners’ SS was more closely linked with relationship satisfaction than female partners (Men: t = 6.30; Women: t = 1.99). Similarly, Sprecher (Citation2002) found that that men exhibited a stronger correlation between SS and relational satisfaction (r = .54 vs. .37 in women). In many other studies, however, there seems to be minimal differences between men and women in this association (e.g. Del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes & Sierra, Citation2015; Heiman et al., Citation2011; Schoenfeld et al., Citation2017), although even in cases of non-significant gender effects, men can exhibit slightly stronger associations between factors (e.g. Mark et al., Citation2014).

Research assessing life satisfaction, in contrast, seems to consistently find an absence of gender differences. For example, Buczak-Stec et al. (Citation2019), assessed the relationship between SS and life satisfaction in adults 40 years or older and found no difference between genders. Heywood et al. (Citation2018) also found identical strength of association between SS and life satisfaction in men and women, as did Skałacka and Gerymski (Citation2019) and Penhollow et al. (Citation2009).

In sum, research suggests that, in some cases, males may exhibit a stronger link between SS and QOL than women. However, there are many other studies that suggest minimal gender differences. One possible reason for this inconsistency is that SS has been measured and conceptualized differently across studies. Indeed, defining and effectively measuring the structure of sexual satisfaction has proven challenging. Early scales (e.g. Pinney et al., Citation1987) tended to conflate the affective and evaluative components of satisfaction with distinct constructs like sexual function (e.g. frequency of orgasm). More recent scales have tended to explicitly exclude measurement of sexual function, but continue to conceptualize sexual satisfaction in different ways.

For example, Byers, (Citation1999) conceptualized SS as a single-factor rated on a continuum from positive to negative. The assumption that sexual satisfaction is best captured as a single factor is also evident in the large number of studies that use single item measures (e.g. Davison et al., Citation2009; Laumann et al., Citation2006). Alternatively, measures like the Sexual Satisfaction Scale (Meston & Trapnell, Citation2005) include multiple subscales that distinguish positively valanced factors like “contentment” from negatively valanced ones like “concern.” Other recently constructed measures similarly use multiple subscales to distinguish between positive and negative aspects of sexual satisfaction (e.g. sexual satisfaction vs. sexual dissatisfaction; Shaw & Rogge, Citation2016).

Another potential distinction between aspects of SS that has rarely been examined is satisfaction with interpersonal vs. intrapersonal aspects of one’s sexual experiences. This distinction has been shown to be of potential importance in a number of studies. For example, McClelland (Citation2011) asked participants to sort statements about SS according to levels of personal importance before engaging in semi-structured interviews about what SS means to them. Participants’ responses implied an important distinction between satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of sex (e.g. their partner’s enjoyment of sexual activity) and intrapersonal dimensions (e.g. their own ability to orgasm). Similarly, when Pascoal et al. (Citation2014) asked participants to identify what constitutes being sexually satisfied, two distinct facets were identified: satisfaction with intrapersonal aspects of sex (e.g. one’s own pleasure, positive feelings, arousal, etc.) and interpersonal aspects (romance, expression of feelings, etc.).

A recently created scale, The New Sexual Satisfaction Scale (NSSS; Štulhofer et al., Citation2010), explicitly differentiated between these two components of SS by including subscales assessing “ego-centered” (i.e. intrapersonal) SS and “partner-centered” (i.e. interpersonal) SS. Items in the intrapersonal subscale include satisfaction with (for example) “the quality of my orgasms” and “my focus/concentration during sexual activity,” whereas items in the interpersonal subscale include satisfaction with “my partner’s initiation of sexual activity” and “my partner’s emotional opening up during sex.”

It is likely that conceptualizing and measuring satisfaction in one of these ways vs. another could alter the strength of association between SS and QOL. The distinction between intrapersonal and interpersonal SS might be particularly important, with one being more predictive of QOL than the other. Furthermore, gender differences in the link between SS and QOL may also differ depending on whether a distinction is made between satisfaction with intrapersonal vs. interpersonal aspects of sex.

A number of studies suggest that, in general, women’s experiences with sexuality may be more dependent on the relational context than men’s. For example, Birnbaum and Laser-Brandt (Citation2002) reported that women were more focused on relationship-relevant behaviors during intercourse (e.g. focusing on signs of love and emotional closeness), whereas men tended to focus on physical pleasure. Another study found that sexual frequency and physical factors (e.g. erectile function) exhibited the strongest associations with male’s SS, while psychosocial and relational factors were more strongly associated with SS for women (Kim & Jeon, Citation2013). Similarly, in a study generally critical of stereotyped gender differences regarding sex, Perrin et al. (Citation2011) nevertheless reported one stable difference: Women reporting a greater desire for relationship support surrounding sexual activity.

If the relational context of sex is of relatively greater importance for women on average, it is possible that gender differences in the link between SS and QOL may be most prominent when a distinction is made between satisfaction with interpersonal vs. intrapersonal aspects of sexual activity. In particular, women’s satisfaction with interpersonal components of sexual interactions might be more predictive of QOL as compared to men. Alternatively, men’s satisfaction with intrapersonal components of sexual activity may be more predictive of QOL as compared to women. However, we are aware of no studies that have explicitly tested these hypotheses.

Such gender differences would be important to inform basic scientific understanding of how men and women may experience sexual activity differently, and would also have a number of practical applications. For example, while there are numerous interventions meant to improve the quality of one’s sex life, different interventions may differentially impact interpersonal vs. intrapersonal components of SS. For example, pharmaceutical treatments such as Sildenafil (i.e. Viagra; Goldstein et al., Citation1998) and Flibanserin (i.e. Addyi; Joffe et al., Citation2016) specifically target intrapersonal components of sexual experiences (one’s arousal and desire), but not necessarily interpersonal aspects of sex like emotional connection with one’s partner. It is likely that such interventions may increase intrapersonal SS (e.g. Heiman et al., 2007; Katz et al., Citation2013) more so than interpersonal SS. This same pattern may apply to psychotherapeutic interventions that do not explicitly focus on relational processes, such as individual exposure/vaginal dilator treatment for female sexual pain (e.g. Ter Kuile et al., Citation2013) and the “squeeze technique” for male premature ejaculation (e.g. Shindel et al., Citation2008). Alternatively, couple therapies such as Emotion-Focused Therapy (Denton et al., Citation2000) or Integrative Behavioral Couples Therapy (Christensen et al., Citation2004) which focus on broader relational dynamics much more than specific sexual behaviors or processes (e.g. Johnson & Zuccarini, Citation2011), might be expected to increase interpersonal SS (Soleimani et al., Citation2015; Wiebe et al., Citation2019) significantly more than intrapersonal SS.

If interpersonal vs. intrapersonal aspects of SS are differentially predictive of QOL, then it is possible that these distinct interventions could have significantly different impacts on broader QOL. For example, Viagra may increase physiological arousal in both genders (e.g. Berman et al., Citation2003), however, this increase in arousal (and, theoretically, satisfaction with one’s arousal) may result in a greater increase in QOL for men (e.g. Moncada et al., Citation2009) than for women (e.g. Basson et al., Citation2002). Alternatively, couples therapy may increase satisfaction with interpersonal components of sexual activity more than intrapersonal components like physical pleasure or orgasm. Such a change may translate to larger improvements in QOL for women than for men.

To provide a foundation for exploring such questions, the overall goal of the current study was to explore possible gender differences in the link between SS and QOL. We conceptualized QOL as being multi-faceted, including measurement of mental health and satisfaction/happiness as independent constructs (e.g. Keyes, Citation2005), and differentiating between individually-focused vs. relationally-focused well-being (e.g. Keyes et al., Citation2002).

Based on available research, we predicted:

Men would exhibit a slightly stronger association between SS (broadly defined) and QOL than women

Across genders, interpersonal vs. intrapersonal aspects of SS might differ in strength of association with QOL (these analyses were considered exploratory based on limited past research in this area)

Men would exhibit stronger associations between intrapersonal aspects of SS and QOL than women, while women would exhibit stronger associations between interpersonal aspects of SS and QOL than men.

Method

Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited from two sources from 2018 to 2019. First, online advertisements were posted to craigslist.org, and the lab website of the senior author. Advertisements were posted in area-specific craigslist pages across the United States and included inclusion criteria for the study: 18 years of age or older, currently in a monogamous relationship (given relationship satisfaction as an outcome of interest), and sexually active in the past month. Advertisements also stated that study participation involved answering questions of a sexual nature regarding current and past sexual experiences, and that participants would be entered into a drawing for compensation. Interested individuals contacted the lab via email and were then sent a link to a secure online survey. After completion of measures, participants were entered into a drawing to win one of four $50 gift cards.

Participants were also recruited from an undergraduate Introduction to Psychology participant pool at a small liberal arts university. Students completed the survey in a computer lab while sitting at least one seat apart to ensure anonymity of responses. Student participants received partial course participation credit. Only responses from students who met all inclusion criteria were included in the current analyses. For both samples, order of scales was randomized. All study procedures were approved by the IRB at Willamette University.

The final sample consisted of 188 participants: 61.70% women and 37.80% men. 82 (43.6%) of participants were recruited from Introduction to Psychology courses and 106 (56.4%) were recruited from the general population. The average age of participants was 26.71 years (SD = 11.65). Additional demographics information can be found in .

Table 1. Participant demographic information and descriptive statistics.

Measures

Sexual satisfaction

The New Sexual Satisfaction Scale (Štulhofer et al., Citation2010) is a 20-item measure of sexual satisfaction which evaluates two dimensions of SS: “Ego-centered” (e.g. “My body’s sexual functioning”) and “partner-centered” (e.g. “my partner’s initiation of sexual activity”) - as well as a total score. Participants are asked to rate their satisfaction with each item while thinking about their sex life over the last six months. Responses range from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest possible score (not at all satisfied) and 5 being the highest (extremely satisfied). Reliability and validity have been assessed in a number of studies including (e.g. Mark et al., Citation2014). Štulhofer et al. (Citation2010) analyzed seven independent samples and found moderately high convergent validity with related constructs including sexual boredom, intimacy, sexual satisfaction, and communication about sex, as well as strong test retest reliability and internal consistency. In the current analyses, the ego-centered subscale was used to represent intrapersonal SS and the partner-centered subscale was used to represent interpersonal SS. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .90, 91, and .94 for the ego-centered subscale, partner-centered subscale, and total scale score respectively.

Quality of life

Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a 5-item self-report measure which assesses participants’ perceived level of life satisfaction through their agreement or disagreement with statements (e.g. “in most ways, my life is close to my ideal;” Diener et al., Citation1985). Responses fall on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) - higher scores indicate greater satisfaction. The SWLS has been widely used (Pavot, Citation2014), and shown to have strong psychometric properties, including high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha between .79 to .89) and temporal reliability, with a two-month stability coefficient of .82 and a four-year stability of .42 (Pavot & Diener, Citation1993). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Mental health

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). is a 21-item self-report measure of mental health concerns including depression (e.g. “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all”), anxiety (e.g. “I felt like I was using a lot of nervous energy”), and stress (e.g. “I found it hard to wind down”). Participants are asked to rate statements regarding their experience in the past week on a scale from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much) with higher scores indicating more symptoms (i.e. worse mental health). However, in the current study, we reverse coded all values such that higher scores indicated better mental health to allow for consistency of interpretation across outcomes. The DASS has demonstrated excellent reliability (e.g. Cronbach’s alpha of .89; test- retest and split-half reliability coefficient scores of 0.99 and 0.96), as well as convergent validity with other scales of anxiety, depression, and stress (Brown et al., Citation1997; Crawford & Henry, Citation2003). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .82, .77, and .71 for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales respectively.

Relationship satisfaction

The Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI; Funk & Rogge, Citation2007) is a 16-item self-report scale of relationship satisfaction. Items assess overall happiness (e.g. “Please indicate the degree of happiness, all things considered, of your relationship”), strength of relationship (e.g. “Our relationship is strong”), how rewarding the relationship is (e.g. How well does your partner meet your needs”), and emotions felt about the relationship. Response options differ across items, with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction with the relationship. The CSI is a well-validated, reliable, and commonly used scale to measure relationship satisfaction with correlations between .84 and .99 when comparing with related scales and a Cronbach’s alpha of .94 (Funk & Rogge, Citation2007; Graham et al., Citation2011). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .97.

Data analysis

We began by conducting basic comparisons (using ANOVA) between the two samples, and between genders to assess any significant differences in terms of demographics and/or average scores in factors of interest.

To assess associations between SS and QOL, five sets of analyses were conducted for each QOL outcome (life satisfaction, depression, anxiety, stress, and relationship satisfaction). The first analysis included all participants of any gender. Linear regression was used to assess the degree to which intrapersonal and interpersonal SS predicted QOL. In these models, both SS subscales were included as predictors and age and relationship length were included as covariates (given that they exhibited associations with outcomes; analyses not included here). These models allowed for examination of unique effects of each aspect of SS across genders.

The second and third sets of analyses included only male participants or only female participants respectively, and included the same predictors (both aspects of SS and covariates) as previous models. These analyses allowed for examination of unique effects of each aspect of SS within genders. The fourth and fifth set of analyses used linear regressions to test the interaction between SS (intrapersonal or interpersonal) and gender in predicting QOL. Each model included age and relationship length as covariates, one aspect of SS (intrapersonal or interpersonal), gender, and the interaction between gender and SS. These analyses explicitly tested for gender differences in the strength of association between each aspect of SS and QOL.

Results

Differences between samples and genders

The two samples significantly differed in terms of age (Intro Psych M = 19.06, Craigslist M = 32.62; F (1, 186) = 93.68, p < .001), average length of relationship (Intro Psych M = 13.17 months, Craigslist M = 72.66 months; F (1, 160) = 23.06, p < .001), and anxiety (Intro Psych M = 1.96, Craigslist M = 2.22; F (1, 175) = 6.66, p < .05). The Introduction to Psychology sample was on average younger, in briefer relationships, and had slightly higher reported anxiety. Participants in the Introduction to Psychology sample was also less likely to be married and more likely to be dating (χ2 = 40.57, p < .001). These differences were expected, and help justify the inclusion of age and relationship length as control variables in subsequent analyses. There were otherwise no significant differences between samples. Additionally, there were no significant differences between genders in terms of demographics or mean values of study variables. Correlations between all study variables, separated by gender, can be found in .

Table 2. Correlation matrix of study factors.

Association between SS and QOL, across and within genders

Life satisfaction

When both genders were included, the model with life satisfaction as the outcome was significant (F (4, 139) = 8.86, p < .001). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .17 (p < .001; see ). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .39, p < .001), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = .02, p > .05).

Table 3. Associations between sexual satisfaction and quality of life across and between genders.

When only men were included, the model was significant (F (4, 51 = 3.79, p < .01). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .15 (p < .05). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .56, p < .01), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = −.31, p > .05).

When only women were included, the model was significant (F (4, 82 = 6.73,p < .001). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .23 (p < .001). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .28, p < .05), and interpersonal sexual satisfaction was a marginally significant predictor (β = .25, p = .08).

Depression

When both genders were included, the model with depression as the outcome was significant (F (4, 139 = 4.06, p < .01). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .09 (p < .01). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .23, p < .05), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = .08, p > .05).

When only men were included, the model was significant (F (4, 50 = 3.85, p < .01). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .19 (p < .01). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .57, p < .01), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = −.20, p > .05).

When only women were included, the model was marginally significant (F (4, 83 = 2.06, p = .09). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .07 (p = .06). Neither intrapersonal sexual satisfaction (β = .03, p > .05), or interpersonal sexual satisfaction (β = .23, p > .05) were unique predictors.

Anxiety

When both genders were included, the model with anxiety as the outcome was significant (F (4, 139 = 3.23, p < .05). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .04 (p < .05). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique marginally significant predictor (β = .19, p = .09), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = .03, p > .05).

When only men were included, the model was significant (F (4, 50 = 4.75, p < .01). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .17 (p < .01). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .58, p < .01), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = −.27, p > .05).

When only women were included, the model was significant (F (4, 81 = 3.23, p < .05). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .04 (p > .05). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was not a unique significant predictor (β = −.17, p > .05), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was marginally significant (β = .30, p = .05).

Stress

When both genders were included, the model with stress as the outcome was significant (F (4, 135 = 4.08, p < .01). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .06 (p < .05). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique marginally significant predictor (β = .20, p = .09), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = .06, p > .05).

When only men were included, the model was significant (F (4, 48 = 2.89, p < .05). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .10 (p = .06). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .43, p < .05), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = −.17, p > .05).

When only women were included, the model was marginally significant (F (4, 79 = 2.36, p = .06). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .07 (p < .05). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was not a unique significant predictor (β = −.05, p > .05), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was marginally significant (β = .31, p = .05).

Relationship satisfaction

When both genders were included, the model with relationship satisfaction as the outcome was significant (F (4, 137 = 23.70, p < .001). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .33 (p < .001). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .36, p < .001), as was interpersonal sexual satisfaction (β = .28, p < .01).

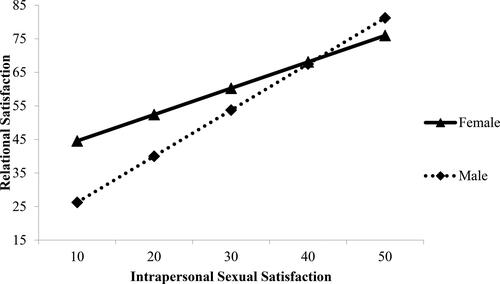

When only men were included, the model was significant (F (4, 48 = 11.11, p < .001). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .36 (p < .05). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a unique significant predictor (β = .64, p < .001), however, interpersonal sexual satisfaction was not (β = −.02, p > .05).

When only women were included, the model was significant (F (4, 83 = 14.26, p < .001). The proportion of variance explained by sexual satisfaction over and above age and relationship length was .36 (p < .001). Intrapersonal sexual satisfaction was a marginally significant predictor (β = .23, p = .06), and interpersonal sexual satisfaction was a significant predictor (β = .42, p < .01).

Interaction models

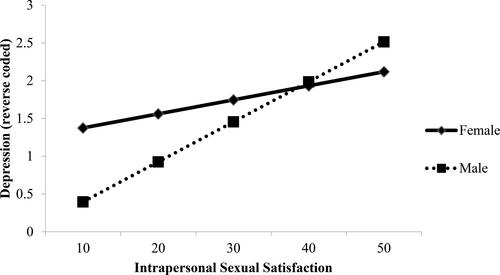

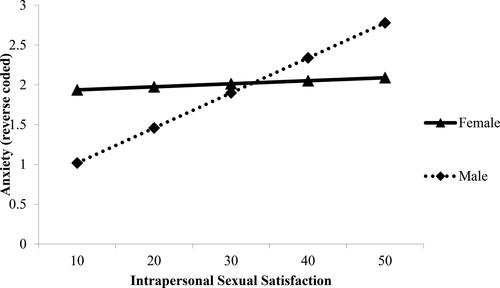

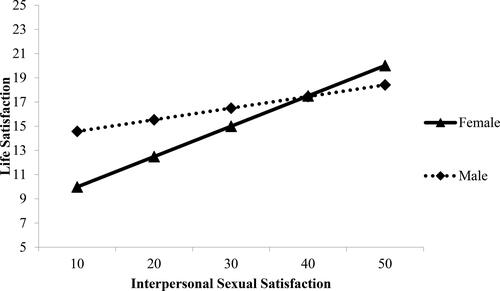

Of the eight interaction models tested, four produced interaction terms that were significant or marginally significant. Men exhibited a stronger or marginally stronger link between intrapersonal SS and depression (), anxiety (), and relational satisfaction () than did women. In each case, low SS was more likely to be associated with lower QOL for men than for women. Additionally, women exhibited a marginally stronger link between interpersonal SS and life satisfaction than did men (), with low SS more likely to be associated with low life satisfaction for women. Parameters for all models can be found in .

Table 4. Interaction models testing gender differences in the association between SS and QOL.

Discussion

The goal of the current analyses was to explore associations between SS and QOL, including how these may differ across genders, and across different aspects of SS. When examining the association between overall SS (both interpersonal and intrapersonal) and QOL for the sample as a whole, the strength of association differed depending on which aspect of QOL was measured (from a low of 4% of variance in anxiety scores accounted for to a high of 33% of variance in relational satisfaction accounted for). The effect sizes were generally weak-to-moderate. Both the size of effects and the variability across outcomes are in line with results from past studies (Chao et al., Citation2011; Flynn et al., Citation2016; Neto & Pinto, Citation2015; Penhollow et al., Citation2009)

When men and women were considered in isolation, different patterns of effects emerged. In terms of overall strength of association between QOL and total SS, men exhibited somewhat stronger links between SS and mental health factors of depression and anxiety than did women. Alternatively, women exhibited a very slightly stronger association between SS and life satisfaction than did men, and men and women were identical in terms of the strength of association between SS and relational satisfaction. These results are in line with previous research suggesting a potentially stronger link between SS and mental health in men (e.g. Flynn et al.,Citation2016; Wylie et al., Citation2002), and similar to the multiple studies that have found no gender differences in the link between SS and relational satisfaction (Heiman et al., Citation2011; Schoenfeld et al., Citation2017) or life satisfaction (e.g. Buczak-Stec et al., Citation2019; Heywood et al., Citation2018).

When comparing the relative statistical effects of intrapersonal vs. interpersonal SS for the sample as a whole, intrapersonal SS, but not interpersonal SS, was a significant predictor of QOL across outcomes (relational satisfaction was an exception, where both aspects of SS were unique predictors). However, this pattern again differed when examining men and women in isolation. For men, intrapersonal SS was the only significant predictor of QOL in every case (including relational satisfaction). Alternatively, for women, the results were more varied. In some cases, neither aspect of SS was a significant predictor (depression), in others only interpersonal SS was a significant (or marginally significant) predictor (anxiety and stress), and in other cases, both aspects of SS were unique predictors (life satisfaction and relational satisfaction). In other words, intrapersonal SS seemed of primary importance in statistically predicting men’s quality of life, whereas for women, interpersonal SS was as (or more) predictive of QOL than intrapersonal SS. These results were mirrored by interaction models which suggested that intrapersonal SS was a significantly stronger predictor of QOL for multiple outcomes for men than women, whereas interpersonal SS was a marginally stronger predictor of life satisfaction for women than men.

These results may help explain the inconsistent findings across previous studies in this area. In particular, studies that have examined possible gender differences in the link between SS and QOL often used single-item measures or single-factor scales of SS (e.g. Byers, Citation1999; Davison et al., Citation2009; Laumann et al., Citation2006) which cannot account for the potentially multifaceted nature of sexual satisfaction. It may be the case that, for women, both intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects may be uniquely important whereas, for men, their personal experiences and performance may be of primary importance. This pattern is consistent with the idea that the relational context of sexual activity may be of relatively greater importance to women.

There are a number of alternative explanations for these findings. It is certainly possible that men are simply less concerned than women about their partners’ experiences (e.g. Barnett et al., Citation2018). However, it’s also possible that men in relationships with women are simply less aware (on average) of the quality of their partners’ sexual experiences. Multiple studies have suggested that women perceive, and may act in accordance with, stereotypes that they take less active roles in creating their own sexual experiences (Fetterolf & Sanchez, Citation2015; Hundhammer & Mussweiler, Citation2012; Kiefer & Sanchez, Citation2007). One likely consequence of these internalized stereotypes is that women feel less comfortable engaging in explicit communication about their sexual preferences and the quality of their sexual experiences (e.g. Willis et al., Citation2019).

This limited sexual communication, combined with the less visually explicit nature of female sexual arousal and orgasm makes it unsurprising that (in heterosexual relationships) men are less likely to be aware of the level of a partner’s arousal (e.g. Fallis et al., Citation2014; Muise et al., Citation2016), or whether they experienced an orgasm (e.g. Jonason, Citation2019; Salisbury & Fisher, Citation2014). This limited understanding of a partner’s experience may decrease the degree to which interpersonal SS is key in shaping men’s broader QOL. It is possible, therefore, that interpersonal SS may be of relatively greater importance to men in cases where there is more extensive sexual communication and resulting understanding of partners’ experiences. Of course, future research is necessary to explore these possibilities.

The current study had a number of important limitations that should temper any interpretations. First and foremost, the methodology was non-experimental and, as such, no causal conclusions can be drawn. While it is possible that SS contributes in a causal way to QOL for many individuals (e.g. Sprecher & Cate, Citation2004), it is likely that causality can also operate in the opposite direction in some cases (e.g. Kalmbach et al., Citation2015), and/or there could be a reciprocal causal relationship (e.g. Byers, Citation2005; Peleg-Sagy & Shahar, Citation2013). Alternatively, correlations between SS and QOL may be at least partially the result of unmeasured “third variables” (e.g. Neuroticism; Fisher & McNulty, Citation2008). To determine the degree to which SS contributes to QOL, more longitudinal and experimental studies are needed.

Additionally, the current sample was relatively young, white, and educated, a common problem in psychological research in general (Henrich et al., Citation2010). It will be important to replicate these findings using larger, more diverse samples. In addition to demographic diversity, it is also important to assess whether these patterns of results differ among individuals with sexual dysfunction, who may exhibit unique cognitive and behavioral processes related to sexual satisfaction (e.g. Wiegel et al., Citation2007).

Furthermore, while we attempted to include well-established scales assessing multiple components of QOL, these choices came with limitations. For example, the scales used to assess QOL had differing instructions for completion (e.g. the DASS asks about mental health concerns in the past week while the CSI does not provide a time-frame) and the range of factors measured was in no way exhaustive. Indeed, how to best conceptualize and measure well-being is a complex area of research with sometimes mixed findings regarding the applicability of different theories (e.g. Disabato et al., Citation2016). Future studies would benefit from using self-contained scales that include multiple components of QOL, and which are related to an organized theory of well-being (e.g. The Scales of Psychological Well-Being; Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995).

Lastly, the current study focused on individuals who identified as male or female only and, importantly, did not assess for identification as cisgender vs. transgender. While it is likely that LGBTQ + individuals are similar to cisgender, heterosexual individuals in most ways, studies do suggest important differences in terms of their sexual experiences and well-being (Flynn et al., Citation2017; Lindroth et al., Citation2017; Stephenson et al., Citation2017). It is unclear whether and how the current findings, which are specific to male and female gender identities, may apply to non-binary individuals and/or interact with different sexual orientations.

Despite these limitations, the current results have a number of potential implications. First, future research on sexual satisfaction should explicitly describe how the factor is conceptualized, and acknowledge that single-factor or single-item measurement may overlook important sub-components of well-being. Second, the current findings suggest new considerations in treatment-outcome research. While multiple behavioral (Brotto & Basson, Citation2014; Seiter et al., Citation2020), pharmacological (Abdo et al., Citation2008; Nijland et al., Citation2006), and educational (e.g. Zippan et al., Citation2020) interventions have been shown to increase sexual satisfaction, little is known about the degree to which interventions specifically targeted at sexual experiences improve non-sexual quality of life.

The current results suggest that the effects of sexual treatments on broader well-being may depend on the nature of the treatment. For example, improving sexual arousal via medication may primarily improve satisfaction with intrapersonal components of sexual experiences, and this change may have a larger impact on QOL for men than for women. Alternatively, addressing interpersonal components of sexual experiences via couples-based sex therapy (or non-sexual couples therapy) may result in higher satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of sexual interactions, which may have a larger impact on QOL for women than for men. We urge researchers assessing the impact of various interventions to improve sexual well-being to consider including measures of broader quality of life so these important issues can be explored.

In sum, the current results provide preliminary evidence that that men and women may differ in how closely SS is related to their QOL, but that the larger gender effect may be in which aspects of sexual satisfaction are most important. Satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of sexual experiences may be particularly important to women, and satisfaction with intrapersonal aspects of sexual experiences may be more important to men. Taken together, these results suggest that the question of how closely linked SS is to overall well-being is a complex one, and that any conclusion must address the multi-faceted nature of these constructs, and important individual differences.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Phil Doherty, Ross Enlow, and Whitney Widrig for help with data collection and cleaning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kyle R. Stephenson

Kyle Stephenson is an Associate Professor in the School of Psychology at Xavier University. His research interests include sexual well-being and dysfunction, Cognitive-Behavioral and Mindfulness-Based Therapies, romantic relationships, and trauma/PTSD.

Camryn Pickworth

Camryn Pickworth graduated from Willamette University in 2021 with a BS in Civic Communication & Media and a minor in Psychology. Her research interests include relationships and sexuality, especially as it pertains to the well-being of couples.

Parker S. Jones

Parker Jones is currently an undergraduate student at Willamette University majoring in Studio Art and Psychology. His research interests lie in clinical psychology broadly.

References

- Abdo, C. H. N., Afif-Abdo, J., Otani, F., & Machado, A. C. (2008). Sexual satisfaction among patients with erectile dysfunction treated with counseling, sildenafil, or both. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(7), 1720–1726. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00841.x

- Atlantis, E., & Sullivan, T. (2012). Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(6), 1497–1507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02709.x

- Bancroft, J., Loftus, J., & Long, S. (2003). Distress about sex: A national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32(3), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023420431760

- Barnett, M. D., Moore, J. M., Woolford, B. A., & Riggs, S. A. (2018). Interest in partner orgasm: Sex differences and relationships with attachment strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 124, 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.015

- Basson, R., McInnes, R., Smith, M. D., Hodgson, G., & Koppiker, N. (2002). Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 11(4), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1089/152460902317586001

- Berman, J. R., Berman, L. A., Toler, S. M., Gill, J., & Haughie, S. (2003). Safety and efficacy of sildenafil citrate for the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: A double-blind, placebo controlled study. Journal of Urology, 170(6), 2333–2338. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000090966.74607.34

- Birnbaum, G. E., & Laser-Brandt, D. (2002). Gender differences in the experience of heterosexual intercourse. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 11(3–4), 143–158. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-22539-003

- Brotto, L. A., & Basson, R. (2014). Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.001

- Brown, T. A., Chorpita, B. F., Korotitsch, W., & Barlow, D. H. (1997). Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00068-x

- Buczak-Stec, E., König, H.-H., & Hajek, A. (2019). The link between sexual satisfaction and subjective well-being: A longitudinal perspective based on the German ageing survey. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 28(11), 3025–3035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02235-4

- Byers, E. (1999). The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction: implications for sex therapy with couples. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 33(2), 95–111.

- Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552264

- Chao, J.-K., Lin, Y.-C., Ma, M.-C., Lai, C.-J., Ku, Y.-C., Kuo, W.-H., & Chao, I.-C. (2011). Relationship among sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life in middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 37(5), 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.607051

- Christensen, A., Atkins, D. C., Berns, S., Wheeler, J., Baucom, D. H., & Simpson, L. E. (2004). Traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy for significantly and chronically distressed married couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(2), 176–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.176

- Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2003). The depression anxiety stress scales (DASS): Normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466503321903544

- Davison, S. L., Bell, R. J., LaChina, M., Holden, S. L., & Davis, S. R. (2009). The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(10), 2690–2697. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01406

- Del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, M., & Sierra, J. C. (2015). Sexual satisfaction in a heterosexual and homosexual Spanish sample: The role of socio-demographic characteristics, health indicators, and relational factors. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(2), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2014.978275

- Denton, W. H., Burleson, B. R., Clark, T. E., Rodriguez, C. P., & Hobbs, B. V. (2000). A randomized trial of emotion-focused therapy for couples in a training clinic. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 26(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2000.tb00277.x

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S., (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Disabato, D. J., Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L., & Jarden, A. (2016). Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000209

- Fallis, E. E., Rehman, U. S., & Purdon, C. (2014). Perceptions of partner sexual satisfaction in heterosexual committed relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 541–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0177-y

- Fetterolf, J. C., & Sanchez, D. T. (2015). The costs and benefits of perceived sexual agency for men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(4), 961–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0408-x

- Fisher, T. D., & McNulty, J. K. (2008). Neuroticism and marital satisfaction: The mediating role played by the sexual relationship. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 22(1), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.112

- Flynn, K. E., Lin, L., Bruner, D. W., Cyranowski, J. M., Hahn, E. A., Jeffery, D. D., Reese, J. B., Reeve, B. B., Shelby, R. A., & Weinfurt, K. P. (2016). Sexual satisfaction and the importance of sexual health to quality of life throughout the life course of US adults. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(11), 1642–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.08.011

- Flynn, K. E., Lin, L., & Weinfurt, K. P. (2017). Sexual function and satisfaction among heterosexual and sexual minority U.S. adults: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One, 12(4), e0174981. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174981

- Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the couples satisfaction index. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 21(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572

- Goldstein, I., Lue, T. F., Padma-Nathan, H., Rosen, R. C., Steers, W. D., & Wicker, P. A. (1998). Oral sildenafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(20), 1397–1404. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199805143382001

- Graham, J. M., Diebels, K. J., & Barnow, Z. B. (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 25(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022441

- Heiman, J. R., Long, J. S., Smith, S. N., Fisher, W. A., Sand, M. S., & Rosen, R. C. (2011). Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(4), 741–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9703-3

- Heiman, J., Talley, D., Bailen, J., Oskin, T., Rosenberg, S., Pace, C., Creanga, D., & Bavendam, T. (2007). Sexual function and satisfaction in heterosexual couples when men are administered sildenafil citrate (viagra®) for erectile dysfunction: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 114(4), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01228.x

- Henderson-King, D., & Veroff, J. (1994). Sexual satisfaction and marital well-being in the first years of marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(4), 509–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407594114002

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Beyond WEIRD: Towards a broad-based behavioral science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10000725

- Heywood, W., Lyons, A., Fileborn, B., Hinchliff, S., Minichiello, V., Malta, S., Barrett, C., & Dow, B. (2018). Sexual satisfaction among older Australian heterosexual men and women: Findings from the sex, age & me study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1366959

- Hundhammer, T., & Mussweiler, T. (2012). How sex puts you in gendered shoes: Sexuality-priming leads to gender-based self-perception and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028121

- Joffe, H. V., Chang, C., Sewell, C., Easley, O., Nguyen, C., Dunn, S., Lehrfeld, K., Lee, L., Kim, M.-J., Slagle, A. F., & Beitz, J. (2016). FDA approval of flibanserin-treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(2), 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1513686

- Johnson, S. M., & Zuccarini, D. (2011). EFT for sexual issues: An integrated model of couple and sex therapy. In J. L. Furrow, S. M. Johnson, & B. A. Bradley (Eds.), The emotionally focused casebook: New directions in treating couples (pp. 219–246). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jonason, P. K. (2019). Reasons to pretend to orgasm and the mating psychology of those who endorse them. Personality and Individual Differences, 143(1), 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.026

- Kalmbach, D. A., Pillai, V., Kingsberg, S. A., & Ciesla, J. A. (2015). The transaction between depression and anxiety symptoms and sexual functioning: A prospective study of premenopausal, healthy women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(6), 1635–1649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0381-4

- Kashdan, T. B., Goodman, F. R., Stiksma, M., Milius, C. R., & McKnight, P. E. (2018). Sexuality leads to boosts in mood and meaning in life with no evidence for the reverse direction: A daily diary investigation. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 18(4), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000324

- Katz, M., DeRogatis, L. R., Ackerman, R., Hedges, P., Lesko, L., Garcia, M., Jr., & Sand, M. (2013). Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results from the BEGONIA trial. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(7), 1807–1815. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12189

- Keyes, C. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539

- Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007–1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007

- Kiefer, A. K., & Sanchez, D. T. (2007). Scripting sexual passivity: A gender role perspective. Personal Relationships, 14(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00154.x

- Kim, O., & Jeon, H. O. (2013). Gender differences in factors influencing sexual satisfaction in Korean older adults. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 56(2), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2012.10.009

- Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., Glasser, D. B., Kang, J.-H., Wang, T., Levinson, B., Moreira, E. D., Nicolosi, A., & Gingell, C. (2006). A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: Findings from the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-005-9005-3

- Lindroth, M., Zeluf, G., Mannheimer, L. N., & Deogan, C. (2017). Sexual health among transgender people in Sweden. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1301278

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S., & Reece, M. (2014). A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.816261

- McClelland, S. I. (2011). Who is the “self” in self reports of sexual satisfaction? research and policy implications. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 8(4), 304–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-011-0067-9

- McNulty, J. K., Wenner, C. A., & Fisher, T. D. (2016). Longitudinal associations among relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and frequency of sex in early marriage. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0444-6

- Meston, C., & Trapnell, P. (2005). Development and validation of a five-factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale for women: The sexual satisfaction scale for women (SSS-W). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 2(1), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20107.x

- Moncada, I., Martínez-Jabaloyas, J. M., Rodriguez-Vela, L., Gutiérrez, P. R., Giuliano, F., Koskimaki, J., Farmer, I. S., Renedo, V. P., & Schnetzler, G. (2009). Emotional changes in men treated with sildenafil citrate for erectile dysfunction: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(12), 3469–3477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01514.x

- Morgan, P. C., Durtschi, J. A., & Kimmes, J. G. (2018). Sexual and relationship satisfaction associated with shifts in dyadic trajectories of depressive symptoms in German couples across four years. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 44(4), 655–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12302

- Muise, A., Stanton, S. C. E., Kim, J. J., & Impett, E. A. (2016). Not in the mood? Men under- (not over-) perceive their partner’s sexual desire in established intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(5), 725–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000046

- Neto, F., & Pinto, M. d C. (2015). A cross-cultural investigation of satisfaction with sex life among emerging adults. Social Indicators Research, 120(2), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0604-z

- Nicolosi, A., Moreira, E. D., Jr., Villa, M., & Glasser, D. B. (2004). A population study of the association between sexual function, sexual satisfaction and depressive symptoms in men. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.008

- Nijland, E., Davis, S., Laan, E., & Schultz, W. W. (2006). REVIEW: Female sexual satisfaction and pharmaceutical intervention: A critical review of the drug intervention studies in female sexual dysfunction. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3(5), 763–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00285.x

- Pascoal, P. M., de Santa Bárbara Narciso, I., & Pereira, N. M. (2014). What is sexual satisfaction? thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.815149

- Pavot, W. (2014). Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS), an overview. In: Michalos A.C. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2576

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

- Peleg-Sagy, T., & Shahar, G. (2013). The prospective associations between depression and sexual satisfaction among female medical students. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(7), 1737–1743. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12176

- Penhollow, T. M., Young, M., & Denny, G. (2009). Predictors of quality of life, sexual intercourse, and sexual satisfaction among active older adults. American Journal of Health Education, 40(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2009.10599074

- Perrin, P. B., Heesacker, M., Tiegs, T. J., Swan, L. K., Lawrence, A. W., Smith, M. B., Carrillo, R. J., Cawood, R. L., & Mejia-Millan, C. M. (2011). Aligning Mars and Venus: The social construction and instability of gender differences in romantic relationships. Sex Roles, 64(9-10), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9804-4

- Pinney, E. M., Gerrard, M., & Denney, N. W. (1987). The Pinney Sexual Satisfaction Inventory. Journal of Sex Research, 23(2), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498709551359

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

- Ryan, R .M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Salisbury, C. M. A., & Fisher, W. A. (2014). “Did you come?” A qualitative exploration of gender differences in beliefs, experiences, and concerns regarding female orgasm occurrence during heterosexual sexual interactions?. Journal of Sex Research, 51(6), 616–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.838934

- Schoenfeld, E. A., Loving, T. J., Pope, M. T., Huston, T. L., & Štulhofer, A. (2017). Does sex really matter? Examining the connections between spouses’ nonsexual behaviors, sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(2), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0672-4

- Seiter, N. S., Quirk, K., Hardy, N., Zinbarg, R. E., Goldsmith, J. Z., & Pinsof, W. M. (2020). Changes in commitment and sexual satisfaction: Trajectories in couple therapy. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(3), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2019.1677274

- Shaw, A. M., & Rogge, R. D. (2016). Evaluating and refining the construct of sexual quality with item response theory: Development of the quality of sex inventory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(2), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0650-x

- Shindel, A., Nelson, C., & Brandes, S. (2008). Urologist practice patterns in the management of premature ejaculation: A nationwide survey. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(1), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00638.x

- Skałacka, K., & Gerymski, R. (2019). Sexual activity and life satisfaction in older adults. Psychogeriatrics, 19(3), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12381

- Soleimani, A. A., Najafi, M., Ahmadi, K., Javidi, N., Hoseini Kamkar, E., & Mahboubi, M. (2015). The effectiveness of emotionally focused couples therapy on sexual satisfaction and marital adjustment of infertile couples with marital conflicts. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility, 9(3), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.22074/ijfs.2015.4556

- Sprecher, S. (2002). Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. Journal of Sex Research, 39(3), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552141

- Sprecher, S., & Cate, R. M. (2004). Sexual satisfaction and sexual expression as predictors of relationship satisfaction and stability. J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 235–256). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2010). Differentiating components of sexual well-being in women: Are sexual satisfaction and sexual distress independent constructs? The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(7), 2458–2468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01836.x

- Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2015). The conditional importance of sex: Exploring the association between sexual well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2013.811450

- Stephenson, R., Riley, E., Rogers, E., Suarez, N., Metheny, N., Senda, J., Saylor, K. M., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2017). The sexual health of transgender men: A scoping review. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 424–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1271863

- Štulhofer, A., Buško, V., & Brouillard, P. (2010). Development and bicultural validation of the new sexual satisfaction scale. The Journal of Sex Research, 47(4), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903100561

- Ter Kuile, M. M., Melles, R., de Groot, H. E., Tuijnman-Raasveld, C. C., & van Lankveld, J. J. D. M. (2013). Therapist-aided exposure for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list control trial of efficacy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 1127–1136. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034292

- Thompson, I. M., Tangen, C. M., Goodman, P. J., Probstfield, J. L., Moinpour, C. M., & Coltman, C. A. (2005). Erectile dysfunction and subsequent cardiovascular disease. JAMA, 294(23), 2996–3002. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.23.2996

- Vanwesenbeeck, I., Ten Have, M., & De Graaf, R. (2014). Associations between common mental disorders and sexual dissatisfaction in the general population. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 205(2), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.135335

- Wiebe, S. A., Elliott, C., Johnson, S. M., Burgess Moser, M., Dalgleish, T. L., Lafontaine, M.-F., & Tasca, G. A. (2019). Attachment change in emotionally focused couple therapy and sexual satisfaction outcomes in a two-year follow-up study. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 18(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2018.1481799

- Wiegel, M., Scepkowski, L. A., & Barlow, D. H. (2007). Cognitive-Affective processes in sexual arousal and sexual dysfunction. In E. Janssen, & E. Janssen (Eds.), The psychophysiology of sex (pp. 143–165). Indiana University Press.

- Willis, M., Hunt, M., Wodika, A., Rhodes, D. L., Goodman, J., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2019). Explicit verbal sexual consent communication: effects of gender, relationship status, and type of sexual behavior. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(1), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2019.1565793

- Wylie, K. R., Steward, D., Seivewright, N., Smith, D., & Walters, S. (2002). Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in three psychiatric outpatient settings: a drug misuse service, an alcohol misuse service and a general adult psychiatry clinic. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 17(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990220121284

- Zippan, N., Stephenson, K. R., & Brotto, L. A. (2020). Feasibility of a brief online psychoeducational intervention for women with sexual interest/arousal disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(11), 2208–2219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.07.086