Abstract

Infidelity is a relationship betrayal that can lead to multiple negative individual and relational outcomes. Multiple clinicians have developed practice-based models of couple healing from infidelity; however, few of these models have been systematically examined. One such model is Butler et al.’s clinical model, grounded in attachment theory and the concept of relational ambivalence. In the present study, we sought to systematically examine and refine Butler et al.’s model of couple healing from infidelity using deductive qualitative analysis of seven publicly available online blogs written by non-straying partners. Informed by the clinically based model, we generated sensitizing constructs and engaged in open, focused, and theoretical coding. Our results support several key components of the original model, while also suggesting refinements to the concept of ambivalence for straying partners as well as couple-level responses. Our results suggest that a meaningful expansion to the original model is non-straying partners’ efforts to heal individually throughout the entire healing process. We suggest clinical implications and opportunities for future research based on our analysis.

LAY SUMMARY

Infidelity is a relationship betrayal that can lead to individual distress and relationship disruption. In this article, we evaluated an existing descriptive model of couple healing from infidelity using seven online blogs. Our results suggest that the existing model of couple healing can be improved by incorporating non-straying partners’ individual healing.

In romantic relationships, infidelity—a violation of relationship boundaries that can include physical, emotional, and sexual components—can be a traumatic, disruptive experience for both partners (Warach & Josephs, Citation2021). Research suggests that infidelity is common, with the General Social Survey of married U.S. adults suggesting a lifetime prevalence of approximately 21.2% for men and 13.4% for women (Labrecque & Whisman, Citation2017). Infidelity is associated with diffuse negative personal and relationship outcomes, including divorce, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and subjective distress (Laaser et al., Citation2017; Warach & Josephs, Citation2021). With the various individual and relational challenges it brings, infidelity is viewed as one of the most difficult presenting problems to address in therapy (Mitchell et al., Citation2021).

Butler et al.’s (Citation2021) descriptive model of couple healing from infidelity is one of multiple models of healing (see Baucom et al., Citation2017; Bird et al., Citation2007; Fife et al., Citation2008; Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006). Few clinical models of healing from infidelity have been subjected to systematic empirical examination, an essential step toward evaluating the effectiveness of the models and establishing commonalities in healing (Gilgun, Citation2014). Though preliminary, the present study is an initial effort to systematically examine Butler et al.’s (Citation2021) model and to suggest refinements and expansions to the model based on our results.

Literature review

Attachment theory

Attachment theory informs multiple models of healing from infidelity (Butler et al., Citation2021; Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006; Mitchell et al., Citation2021; Schade & Sandberg, Citation2012) and can significantly enhance other models (Baucom et al., Citation2017; Bird et al., Citation2007; Fife et al., Citation2008, Citation2011; Olson et al., Citation2002). In attachment terms, infidelity is an attachment injury or an attachment betrayal, an interpersonal trauma that triggers powerful emotions and attachment-organized survival responses (Butler et al., Citation2021; Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006; see also Baucom et al., Citation2017). Couple healing requires the resolution of this trauma as the straying partner provides safe holding for the non-straying partner’s experience and demonstrates consistent trustworthiness (Butler et al., Citation2021; Schade & Sandberg, Citation2012).

Models of couple healing

Although a full review of multiple models is beyond the scope of this paper, we highlight commonalities in healing between them, based on an attachment-oriented reading.

Initial reactivity

Consistent with attachment theory, various models suggest that the early moments after discovery/disclosure are characterized by emotional extremes and, for non-straying partners, a profound sense of betrayal and loss of trust (Butler et al., Citation2021; Fife et al., Citation2008; Olson et al., Citation2002). To move forward, some models emphasize cognitive understanding of the causes and consequences of the infidelity (Baucom et al., Citation2017) and others prioritize managing difficult emotions (Fife et al., Citation2008; Olson et al., Citation2002). Over time, reactivity gives way to a shared commitment to the relationship, conditioned on healing and reparatory efforts (Butler et al., Citation2021; Fife et al., Citation2008).

Responding to the infidelity

Following the emotional milieu attending discovery/disclosure, several authors suggest that couples enter a period of relatively less reactivity (Butler et al., Citation2021; Olson et al., Citation2002). Non-straying partners may avoid discussing the infidelity and engage in behaviors meant to numb their painful emotions (Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006). Straying partners may apologize for the infidelity, and non-straying partners may express their intent to forgive (Fife et al., Citation2011; Mitchell et al., Citation2021). It is during this period that couples often seek therapeutic intervention (Abrahamson et al., Citation2012; Bird et al., Citation2007; Fife et al., Citation2008).

Processing the infidelity

As emotional safety increases, couples gradually become more able to discuss the infidelity and contributing factors that led up to it, including systemic patterns and individual and couple vulnerabilities (Baucom et al., Citation2017; Butler et al., Citation2021; Fife et al., Citation2008; Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006). Common components and outcomes of healing include forgiveness, re-establishing trust, and meaning making (Abrahamson et al., Citation2012; Baucom et al., Citation2017; Butler et al., Citation2021; Fife et al., Citation2011; Olson et al., Citation2002). The straying partner plays a crucial role in inviting trust through accountability and trustworthy actions. Transformative change allows many couples to transcend the infidelity and re-establish trust and connection, while for others healing may remain tentative and incomplete (Baucom et al., Citation2017; Butler et al., Citation2021).

The hypothesized model

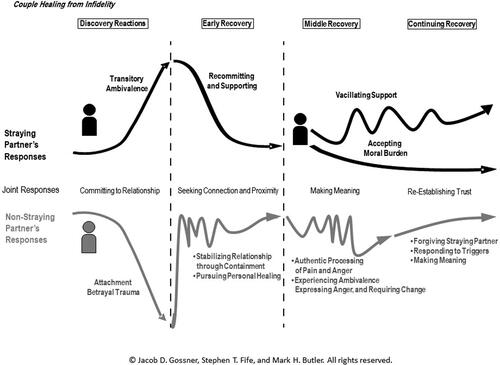

Butler et al.’s (Citation2021) descriptive model of couple healing is grounded in attachment theory and attachment dynamics (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007) and the experience of relational ambivalence. Their model (hereafter referred to as the hypothesized model) considers alternating attachment-organized non-straying partner (NonSP) and straying partner (SP) responses in turn and organizes healing into four processual stages: betrayal-disruption; ambivalence-containment; recommitment-ambivalence; and moral burden-healing (Supplemental figure 1).

Betrayal-Disruption

In the hypothesized model, infidelity is conceptualized as a form of betrayal trauma that erodes the attachment foundation of the relationship and severely threatens its viability. NonSPs feel betrayed in response to SPs’ actions; yet durable, resilient pair-bond attachment leads to efforts to preserve the relationship.

Ambivalence-Containment

The hypothesized model proposes that in the aftermath of infidelity, SPs experience ambivalence, torn between wanting to and not wanting to remain in or work on the primary relationship, as either choice involves some kind of relationship “ordeal.” SPs’ ambivalence is perceived by NonSPs as an attachment threat, and in response they attempt to stabilize the relationship by engaging in three interrelated behavioral responses: containment, holding the pain and anger inside; proximity seeking, attempting to be close physically, emotionally, and sexually to SPs; and caregiving, meeting SPs’ needs. The model suggests that one function of NonSPs’ behaviors is to incentivize the primary relationship, thereby inviting SPs to resolve ambivalence in favor of recommitment.

Recommitment-Ambivalence

Given the durability and resiliency of attachment relationships, in response to NonSPs’ stabilizing efforts, many SPs recommit to the relationship. Their recommitment, reinvestment, and efforts to change gradually signals to NonSPs that the relationship is stable enough for them to now safely process their own experience. This leads NonSPs to release containment, which in turn can lead to their own period of ambivalence and increased relationship conflict. Nevertheless, the model asserts that this processing is essential to restoring trust and relationship balance.

Moral burden-healing

Joined with SP change, couple healing comes full circle as NonSPs authentically process their experience and SPs accept the moral burden of “holding” NonSP pain and dutifully attending to NonSP healing. SPs’ role in couple healing is benevolent witnessing. NonSPs’ role in couple healing centers on processing anger as benevolent indignation rather than internalizing or externalizing it. In the hypothesized model, these four alternating attachment-organized responses help couples transcend betrayal trauma and achieve relationship healing and renewal.

Purpose of the study

Most models of healing from infidelity are based on clinical experience rather than systematic investigation (see DuPree et al., Citation2007). In contrast, empirical descriptions of the process of healing from the perspective of those who have stayed together are rarely organized into a full model. This study seeks to merge both strands of inquiry by (a) systematically examining the process of healing from infidelity using longitudinal data collected in a naturalistic setting and (b) testing and refining the hypothesized descriptive model of healing from infidelity (Butler et al., Citation2021). To accomplish these ends, we used deductive qualitative analysis (Gilgun, Citation2019; DQA) to analyze seven publicly available online blogs written by NonSPs who remained in the relationship following infidelity.

Methodology

Deductive qualitative analysis

Deductive qualitative analysis (DQA) is a qualitative methodology designed to test, refine, and refute existing theory (Gilgun, Citation2019). DQA developed out of the Chicago School tradition of qualitative research, the same tradition that gave rise to grounded theory (Gilgun, Citation2014). Whereas researchers use grounded theory to generate new theory (Charmaz, Citation2014), researchers using DQA begin their analysis with an existing theory and systematically examine it with the intent to develop a refined theory based on supporting, contradicting, refining, and expanding evidence (Gilgun, Citation2014, Citation2019). Four key processes within DQA are (a) generating sensitizing constructs from the guiding theory, (b) collecting a purposive sample, (c) coding and analysis, and (d) theorizing.

Generating sensitizing constructs

In DQA, researchers use an existing theory, referred to as the hypothesized model, to either provide sensitizing constructs that guide analysis or to generate testable propositions (Gilgun, Citation2014, Citation2019). In the present study, we included the following core concepts from each stage of the hypothesized model (Butler et al., Citation2021) as sensitizing constructs in our analysis: attachment betrayal trauma (NonSP); ambivalence (SP); containment, caregiving, and proximity seeking (NonSP); recommitment (SP); releasing containment and ambivalence (NonSP); accepting or rejecting moral burden (SP); and couple healing. These sensitizing constructs provided an initial, deductive focus to coding. We also operated inductively, searching for additional concepts through open coding, negative case analysis, multiple readings of the data, memo-ing, and team meetings (Gilgun, Citation2014).

Sample collection and characteristics

To accomplish our study, we used a previously collected sample of publicly available online blogs written by NonSPs. We chose to use online blogs as our medium of data collection because it presented a rich, longitudinal view of the healing process, allowing us to examine both variation and consistency. While we had hoped to include blogs written by SPs to present a more balanced perspective on healing, we were only able to locate one blog written by a SP where the couple demonstrated healing by the end of the blog. Rather than potentially misrepresenting SPs’ experience by using too small of a sample, we confined our sample to only NonSPs. This decision came with important limitations in describing the process of healing, discussed further in our limitations section.

To be included in the present study, blogs needed to (a) be written by the non-straying partner; (b) have the committed relationship continue throughout the duration of the blog (excluding those who got divorced or separated); and (c) explicitly or tacitly demonstrate couple healing by the end of the blog, defined as a reduction in anger and pain and an increase in trust and emotional security. These inclusion criteria led to a final sample of seven blogs. The university Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that our research was exempt from IRB approval because publicly available data did not meet the definition of research involving human subjects.

While limited demographic information was available for collection, all couples were heterosexually married both at the time of infidelity and at the time of data collection. Six NonSPs were female and one (Blogger 1) was male. Each SP engaged in sexual infidelity, ranging from a single sexual encounter to multiple affairs over multiple years. Six NonSPs referenced God or religion, while one did not. Six blogs were started shortly after discovery and one blog (Blogger 1) was written retrospectively four years after discovery. Duration and length were as follows: Blogger 1, 10 months, 38 pages; Blogger 2, 15 months, 59 pages; Blogger 3, 17 months, 159 pages; Blogger 4, 12 months, 79 pages; Blogger 5, 20 months, 113 pages; Blogger 6, 18 months, 144 pages; Blogger 7, 6 months, 111 pages—for an average time span of 14 months and a total of 703 single-spaced pages. To facilitate coding, each blog was copied into a separate word processing file and then loaded onto MAXQDA 2018, a qualitative data analysis software.

Coding and analysis

Coding in DQA studies frequently follows grounded theory conventions (Gilgun, Citation2014). We used Charmaz’s (Citation2014) constructivist grounded theory coding method, consisting of open coding and focused coding. Informed by the sensitizing constructs from the hypothesized model, we began our open coding by analyzing a subset of our sample, using both deductively and inductively derived codes. We also intentionally identified and analyzed negative cases, comparing those individuals or instances that departed from the hypothesized model (Gilgun, Citation2014). We compiled these inductively and deductively derived codes into a working codebook.

Analysis in DQA includes attending to four types of evidence: supporting, contradicting, refining, and expanding evidence. Supporting evidence supports the sensitizing constructs and the role they played in the guiding theory. Contradicting evidence counters the importance or role of the sensitizing constructs in the process under examination. Refining evidence suggests the need to modify the role or importance of the sensitizing constructs within the guiding theory. Finally, expanding evidence suggests the importance of additional, inductively derived constructs within the refined theory.

After initial coding of a subset of the sample, we reviewed our preliminary findings and created analytic memos detailing data that supported, contradicted, refined, or expanded the hypothesized model (Charmaz, Citation2014; Gilgun, Citation2019; Saldana, Citation2016). In addition to coding that supported sensitizing constructs from the hypothesized model, our initial coding resulted in several inductively derived categories that were not included in the hypothesized model, such as NonSP individual healing, seeking external support, and joint healing efforts. We discussed our preliminary findings in team meetings. While there was consensus on several categories, there was disagreement on others. We dialogued about differences in interpretation and possible alternative explanations. Based on these discussions, we revised our codebook and incorporated the categories with consensus and those that required further analysis.

We then applied these data-supported categories to the full sample. We engaged in focused coding, seeking to parsimoniously and comprehensively represent bloggers’ experience and ensure that all components of our emerging model were grounded in the data (Charmaz, Citation2014). We paid particular attention to new negative cases that arose in the full sample and analyzed the trajectories of each blogger for commonalities with and departures from the hypothesized model.

Theorizing

The product of both DQA and grounded theory is theory development (Gilgun, Citation2019). To ensure high quality theorizing (Knapp, Citation2009), we utilized an analysis strategy akin to grounded theory’s constant comparison method, comparing case with case, case with the hypothesized model, and case with the revised model (Charmaz, Citation2014). Throughout our analysis, we ensured that all elements of our results were supported by data from multiple bloggers. As a research team, we defined the primary themes and analyzed supporting, contradicting, refining, and expanding evidence for each of them from each blogger. Through discussion, we determined whether the balance of evidence warranted revision for each component of the hypothesized model (Gilgun, Citation2019). We also examined evidence for additional concepts that were generated inductively during the coding process (Gilgun, Citation2014). Finally, we considered theoretical explanations for these revisions and expansions to the hypothesized model.

Reflexivity and trustworthiness

With DQA studies, it is essential that researchers practice reflexivity—acknowledging their influence on the research—and engage in rigorous analysis; otherwise, there is the risk that confirmation bias will distort results (Gilgun, Citation2014). All authors are male, White, and clinically trained. The first author is a graduate student and the second and third authors are professors. All authors have published previously on the process of healing from infidelity. More specifically, the authors of this paper are the developers of the hypothesized model, a practice-based model developed over years of treating couples who have experienced infidelity. We recognized the limitations of our model, given its grounding in our clinical experience and its lack of empirical scrutiny, and we desired to begin the process of improving it through systematic evaluation.

The first author performed the majority of coding and writing and had final say in determining the structure and content of the analysis. To ensure trustworthiness and promote rigor, the first and second authors consulted regularly about the project, using both memo-ing and team analysis to prevent premature conclusions and to limit the risk of confirmation bias. When there were disagreements on the meaning of codes or themes, the research team reviewed the relevant coding excerpts and determined which reading most closely matched the data. For example, a preliminary theme proposed by the first author was experiencing healing in cycles. However, through discussion and review of the data, we determined that this theme could be better captured by including the influence of triggers throughout the healing process and thus collaboratively adjusted the theme. Research meetings were recorded to allow for later review, and analytic memos served to track the developing analysis. Both the first and second authors were familiar with the dataset. The third author reviewed and provided feedback on coding excerpts, preliminary findings, codebook, methodology, and manuscript without directly coding the data.

Results

Informed by the hypothesized model, we organized the deductively and inductively developed results of our analysis into four stages: discovery reactions, early recovery, middle recovery, and continuing recovery. Within these stages, we examine non-straying partners’ (NonSPs) self-reported processes, their descriptions of their partners’ (SPs) processes, and their descriptions of couple processes. We label each theme as supported if our evidence supported the hypothesized sensitizing construct, refined if our evidence suggested the need for modification of the original sensitizing construct, and expanded if the theme was constructed inductively during analysis. Although our stages describe the general progression of healing, we acknowledge that healing was not experienced as fully linear; rather, the process of healing varied and involved multiple setbacks and triggers, which we have attended to throughout our model ().

Discovery reactions

Supported theme: attachment betrayal trauma (NonSPs)

When NonSPs discovered their partners’ infidelity, they experienced it as a traumatic betrayal that led them to lose trust in their partners and in themselves. Blogger 1 reflected on their “profound sense of insecurity” following discovery and wrote, “the person you trusted the most has betrayed you, so you doubt everyone.” NonSPs reported experiencing contradicting, conflicting emotions of pain, anger, and love. Blogger 7 reported her immediate reactions as, “I cried into the chest of the man who caused this pain. Loving him and hating him so fiercely I didn’t know which way was up.” Feelings of betrayal reoccurred throughout the healing journey, particularly in response to triggers, such as seeing the affair partner’s car or remembering formerly happy memories that were now tainted by the infidelity. Blogger 4 explained that "every memory for 18 years was gone. I couldn’t look back and have any good or happy thoughts about where we had been, things said, things we had done.”

Although several NonSPs initially assumed that their marriage was over, all NonSPs in our sample quickly decided to work on reconciling with their partners. Blogger 7 wrote that the day following discovery, she realized that “divorce is NOT (sic) the answer… our marriage is worth fighting for.” NonSPs cited multiple factors that influenced their decision to stay together, including love, commitment to marriage vows, and concern for their child(ren). Blogger 3, who originally wanted to throw her partner out of the house, reported, “I looked at him, and I looked at our little boy, and I wondered how I would feel if he walked out the door and never came back?” Reflecting on her love for her partner and son motivated her to attempt to repair the relationship. NonSP discovery reactions thus included emotional and relational disorientation and a decision to attempt reconciliation.

Refined theme: transitory ambivalence (SPs)

Upon NonSPs’ discovery of the infidelity, SPs were presented with the choice of continuing the infidelity or attempting to reconcile with their partners. Several NonSPs wrote that their partners immediately chose to attempt reconciliation. Blogger 1 confronted his partner with an ultimatum and he reported her as saying, “I want to give us a shot,” and then ending the infidelity. Other NonSPs described their partners as experiencing ambivalence, caught between choosing the infidelity relationship or their marriage. However, within 36 hours of discovery, all SPs in our sample ended the infidelity and gave verbal commitment to staying in the relationship. Blogger 6, whose partner initially chose the infidelity relationship, reported being told by her partner that he "loved me then as much as he always had, but that he couldn’t imagine a life without [his infidelity partner].” She further explained that her partner’s ambivalence ended when he realized that meant “he’d lost me. At that point, his world came crashing down.” This realization led him to end the infidelity and recommit to the marriage.

Although NonSPs wrote that their SPs ended the infidelity relatively quickly, they made it clear that some were initially more conciliatory than others. Some of the SPs expressed immediate regret for their actions, asked for forgiveness, and provided details about the infidelity. These actions led NonSPs to believe that SPs were sincere in wanting to put the infidelity behind them. Blogger 5 wrote that her partner had “begged me to forgive him and said he would do anything. I believe him. I’m not saying that I trust him again. But I believed him when he said he loved me.” On the other hand, other SPs attempted to avoid or minimize the impact of the infidelity, such as by refusing to answer questions about the infidelity or blaming the infidelity on their spouse or the infidelity partner. When SPs engaged in these behaviors, NonSPs felt like the infidelity was not truly over, shown by Blogger 2’s comment that, “his reluctance to share information with me kept the affair alive: he was protecting the affair rather than protecting me, so the liaison still existed.”

Refined theme: joint commitment to relationship

The NonSPs reported that both they and their partners were committed to attempting to preserve and repair their relationship. The NonSP committed first in each couple, but shortly after discovery both partners separately chose to remain in their relationship and expressed this commitment to each other. Blogger 3 explained that in the aftermath of infidelity, “we both chose each other. In spite of everything we’ve done to each other, I don’t want a life without him and he doesn’t want one without me either. We love each other.” Motivated by this perceived shared commitment, couples moved into early recovery rather than relationship dissolution.

Early recovery

Supported theme: stabilizing the relationship through containment (NonSPs)

Following discovery of infidelity, multiple bloggers reported that they felt “dead” inside but that they attempted to present the relationship as being normal. They reported various motivations for this, including promoting reconciliation, sparing children from the pain of knowing what had happened, and keeping up appearances in their social circles. One of the primary ways NonSPs stabilized the relationship was redirecting their anger away from their partners and towards the affair partner or themselves. Blogger 3 explained that “managing my hate and anger by placing it on [the affair partner] helps… . Because I love [my partner], because I still want to pursue a future with him, I try to temper my hate and anger.” Blogger 4 observed, “I was afraid to show my anger, I didn’t know how to show or feel this type of anger and because the fear of him going to her and leaving our marriage was [too] great.”

Although they were open about their experiences with their readers, multiple bloggers reported that they had contained the pain of the infidelity from loved ones and some reported that they had also contained their pain from their partners. Blogger 1, who endeavored to keep the infidelity “private,” wrote, “after the affair, I walled myself off from everyone. I felt so isolated … I was never a very open person to begin with, but after the affair I quit reaching out entirely.” This highlights the high emotional and relational costs of NonSPs containing their experience. Consistent with the hypothesized model, NonSPs reflected that their efforts to stabilize the relationship by acting as if nothing had happened (e.g., containment) did not directly heal the relationship. Blogger 2 wrote, “I was fed up with behaving myself and taking it ‘well’ … Being stoic didn’t help anything, it only postponed the crash.”

The NonSPs in our sample attributed their partners’ infidelity to their unmet needs and responded by working to understand and meet them. Blogger 6, who viewed relationship imbalance as the cause of the infidelity, wrote, “since the affair, I have made a huge effort to be a listener. To be interested even when it’s a struggle … it’s worked out well and the relationship has felt more even.”

Some NonSPs also offered encouragement and support to SPs to counteract the shame they felt for having engaged in infidelity. The NonSPs who engaged in these behaviors reported feeling caught between supporting their partners versus acknowledging and processing their own pain. Blogger 5 explained, “I struggle with how his suffering makes me feel. I feel as though I need to love him and support him through his pain. But I should be more concerned about myself, right?” Refining the hypothesized model, NonSPs engaged in containment and sought to meet SPs needs, but with varied motives extending beyond stabilizing the marriage and combined with internal ambivalence about their actions.

Expanded theme: pursuing personal healing (NonSPs)

Early on, NonSPs reported intentionally choosing to pursue a path they hoped would lead to healing. Blogger 3 explained, “I want to be happy. And that means that at some point, I’ll have to let the affair go … I can’t live with one foot in the pain camp and the other in the love camp and then ask why I can’t move on from all this.”

Relatedly, NonSPs focused significant attention on themselves and their own needs following the infidelity. Focusing on themselves allowed them to begin to restore personal well-being while at the same time invigorating their efforts to keep the relationship intact. Some NonSPs reported realizing that they could find happiness even if their relationship ended. After realizing this, Blogger 1 explained, “I wasn’t desperate. I was hopeful and I was willing to work hard to meet my goals, but my life did not depend on my marriage working.”

Throughout their healing journey, but particularly early on, NonSPs emphasized the critical role of external support—therapy, family, friends, God, readers, and other online blogs—in helping them move forward from the infidelity and find healing. Blogger 6 expressed, “My best friend visited this week and I cried … I felt like with her I could be honest about the fact it still hurts.” Several of the bloggers reported that their readers’ support was crucial to their healing. Writing directly to her readers, Blogger 7 explained, “I had to let you in on a piece of my heartache, so I could move forward in my tragedy. And, just as I hoped, you lovingly supported me.” As this blogger makes clear, blogging about their experience and receiving support from others helped NonSPs to cope with their emotions; for many NonSPs, it also reinforced their commitment to stay in the relationship.

Supported theme: recommitting and supporting Non-Straying partner (SPs)

Intertwined with NonSPs’ efforts to stabilize the relationship, they described their partners as becoming progressively recommitted to their marriage as evidenced by their reinvestment in the relationship and efforts to repair the damage caused by the infidelity. As evidence of reinvestment, Blogger 3 wrote, “He looks me in the eye. He’s playing with our toddler. He’s present, and he hasn’t been present for a very long time.” SPs’ reinvestment led to meaningful changes to the emotional vibrancy of the relationship. Blogger 6 explained, “For the 5 months since [discovery] I have felt immense love and remorse from him. He talks to me differently, he looks at me differently.”

As SPs accepted responsibility for the infidelity, they actively worked to support their partners and repair the damage their actions had caused. Blogger 1 explained that his partner, “seemed to realize what she had done and what it had cost, what she had let herself become.” While NonSPs described their partners as generally remorseful, honest, and transparent, they also wrote that at times their partners still struggled to support them (NonSPs) in their pain. In some more extreme instances, some NonSPs felt that their partners were distant and withdrawn from healing, leading them to feel abandoned and subsequently resentful. Blogger 2 explained, “I felt that my husband was removed, emotionally distant from our crisis and that I was, essentially, alone with the devils he brought home.” Consistent with the hypothesized model, NonSPs described SPs’ recommitment, reinvestment, and active support as facilitating their healing and SPs’ emotional distance as impeding their healing.

Refined theme: jointly seeking connection and proximity

In the days and weeks following discovery, NonSPs reported that they spent hours talking with their partners, both to understand the infidelity and to connect with one another. Blogger 6 explained, “We talked for hours every day for four days. At times we were so close and loving [that] it was bliss. Bliss with the added torment of what I was going through in my head.”

Physical closeness, sexual and non-sexual, was also important in establishing connection. Within days to weeks after discovery, all the female NonSPs in our sample reported that they engaged in sexual intimacy with their partners, although they were conflicted about these behaviors. Blogger 5 wrote, “Since I found out about the affair, the comfort of lying in his arms and feeling his body alongside mine has been the security we both need at the end of each day.” She also wrote, “Maybe I shouldn’t want to make love to him, but I do … I want him to never question my passion and love.” Despite conflicting emotions, female NonSPs emphasized the beneficial role that sex played in facilitating healing for both partners. Blogger 6 explained, “The fact is, the sex helps—a lot. It helps us feel close, helps us connect.” Refining the hypothesized model, NonSPs reported both partners engaging in multiple strategies to re-establish their attachment connection, even while acknowledging conflicting feelings; in turn, this connection bolstered their commitment to the relationship and facilitated emotional processing.

Middle recovery

Supported theme: authentic processing of pain and anger (NonSPs)

All bloggers made it clear that the pain of the betrayal persisted months and years into recovery. Months into her blog, Blogger 2 disclosed, “We are still living in a world of hurt and pain. Yes, the pain is in the background now, but it is still ever present … will our relationship always be a façade or will it ever be real again?” As NonSPs transitioned into processing their emotional experience, they reported actively talking about their pain with others, including their partner, and engaging in behaviors meant to help them process their emotions, such as yoga, prayer, or meditation. Blogger 3 explained, “My husband has been great, encouraging me to talk to him, ask him question[s] and just cry when I need to. He apologizes over and [over] again.” While moving forward from their pain was a personal journey, NonSPs reported that their partner’s support was essential. Reflecting on this, Blogger 1 explained, “If I had just said [to my partner], ‘You cheated, I’m hurting, and it’s your job to make it better,’ I’d still be waiting. She couldn’t make it stop hurting.” He concluded, “I had to grow for the pain to stop.”

Over time, NonSPs in our sample allowed themselves to feel “rage” and “hate” towards their partners for their actions. This processing of anger represented a shift from blaming self or the affair partner to holding SPs accountable for their actions. Blogger 6 wrote, “My recent anger has made me see things a lot more balanced. Suddenly, a whole 11 months past [discovery], my husband took some of the blame from [the affair partner]—in my eyes.” NonSPs were aware of the potential negative outcomes of expressing their anger directly to their partner and remained cautious in how they manifested it. Blogger 2 explained, “I seemed to fear releasing my rage … I had worked very hard at keeping my reactions civil over the past year and I certainly did not want to undo all of that work with a freaked-out meltdown.” Consistent with the hypothesized model, eventually, NonSPs gradually transitioned from containment to authentic processing directly in the couple relationship.

Supported theme: experiencing ambivalence and requiring change (NonSPs)

As NonSPs processed their pain and reflected on the healing journey still ahead, several of them reported feeling conflicted themselves about staying in the relationship and reported considering a revenge affair, separation, or divorce. Writing two years after she discovered her partner’s infidelity, Blogger 4 explained, “I was on the fence. I had one foot in my relationship with him and one foot out. Suddenly I realized that I was not committed to our relationship, nor was I committed to getting out.” Some NonSPs connected their uncertainty with questioning whether healing from infidelity was truly possible and what staying in the relationship communicated to their partners. Blogger 5 expressed, “As much as I have grown in the past ten months, there are still moments when the affair hits me like a ton of bricks and I question whether I can forgive him completely.” Several NonSPs wrote that they wanted to pursue reconciliation while also wanting to make their partner feel the same pain they had felt.

While NonSPs had required some changes from their partners early in the recovery process, by this point in healing they expected to see consistent progress. Several NonSPs reported that if their partners had not made these changes, or if they had relapsed, they would have divorced them. Blogger 3 explained, “I don’t expect that he can turn around old habits in a week’s time. But his grace period has an expiration date, and he needs to show me progress. Every. Single. Day.” Consistent with the hypothesized model, some NonSPs experienced ambivalence about staying in the relationship as they processed the infidelity and required relationship change in order to counteract this ambivalence.

Supported theme: accepting moral burden or vacillating support (SPs)

As NonSPs worked to process their experience, most described their partners as becoming deeply involved in supporting their healing. After struggling with triggers, Blogger 5 wrote, “My husband’s response to my emotional frustration was to both comfort me and tell me he wants to help me heal and move forward. He said he feels like I’ve helped him figure out what happened … now he wants to figure out how to help me get to the next phase of our healing.” NonSPs openly confided in their partners and their partners actively worked to facilitate their healing. Blogger 7 reported, “a sentence I used with [my partner] a lot is ‘I am in a bad place today’… [he] was always good to wrap me in his arms and pray over me when I was struggling.”

At the same time, some NonSPs described their partners as vacillating in their willingness or capacity to support them, offering comfort in one instance and rejecting responsibility in the next. Several SPs had occasions where they demanded forgiveness or rejected responsibility to help NonSPs heal, and one SP even reported relapsing, although the nature and extent of this relapse was not disclosed. Blogger 6’s experience is illustrative; months into healing, she wrote, “138 days on, [my partner] is still willing to answer every question, go over every detail and talk about it whenever I need to. He still says sorry, and he stills holds me when I cry.” However, just a few weeks later she wrote, “It feels like [my partner] is going back to taking me and our marriage for granted again. Like I’m not worth listening to.” She later wrote, “at times, he finds it very difficult to deal with the way things can be sailing along quite lovely, then BAM (sic), a bad day hits.” NonSPs suggested several reasons for SP vacillation, including anger at themselves and impatience with the healing process. Blogger 4 explained that her partner “continues to hope that I will love him like I did before he cheated.” Consistent with the hypothesized model, we found support for SPs accepting their moral burden as crucial to healing, contrasted by some NonSPs’ descriptions of fluctuations in SPs’ emotional availability and responsiveness.

Expanded theme: joint making meaning of infidelity

In conjunction with NonSPs’ processing of pain and anger and SPs’ efforts to support NonSPs’ healing, couples actively engaged in rituals intended to reclaim their relationship from the infidelity. Several couples reported renewing vows, buying new wedding rings, moving, or visiting the location where the infidelity occurred in order to signify a turning point in their healing. For example, a year into recovery, Blogger 7 visited the site of the infidelity with her husband. She explained her reasoning by comparing infidelity to a wound, writing, “Before it heals up, I want it thoroughly cleaned. So much so, that we NEVER have to reopen this wound again to deal with ‘infection.’” By engaging in meaning-oriented rituals together, couples re-defined what the infidelity meant for them and began a new “chapter” of their relationship.

Continuing recovery

Expanded theme: Forgiving (NonSPs)

Multiple NonSPs referenced forgiving their partners as an important part of healing individually and as a couple. Several NonSPs expressed forgiveness to their partners within days of discovery. Early expressions of forgiveness were motivated by multiple factors, especially love and religion. Blogger 7 explained, “I need Christ to simply flow His forgiveness through me to [my partner]. My job is to merely be open to this, I don’t have to be healed, or ‘in a good place emotionally’ for this to occur.” Even for bloggers who expressed forgiveness early on, later forgiveness based on SPs’ efforts to repair the relationship was an important component of healing. Blogger 1 wrote, “[To forgive, I had to believe] that she understood how badly her decisions hurt me. For that, I needed her to apologize (she did) and I needed to see her remorse (I did).” Continued forgiveness was a daily choice, as Blogger 7 explained, “I had to make a decision after I forgave [him], to not speak down to him, or throw in little jabs that came from the deep hurt in my heart.” Forgiving expands the hypothesized model; early expressions of forgiveness may have been connected with containment, whereas later, more durable forgiving followed the transition from containment to emotional processing.

Expanded theme: Responding to triggers (NonSPs)

In their continuing pursuit of healing over months and years, NonSPs frequently referenced experiencing triggers that set them back in their healing process. While no blogger reported having fully overcome these triggers, they did report learning how to prepare for and respond to them and noted that this was an important component of their healing. Blogger 1 reported that he disarmed triggers by “[repeating] truths to myself, sometimes even writing them down, and fight[ing] my bad logic with good logic.” Several couples established an on-going, as-needed dialogue about the infidelity in order to respond to triggers together. Blogger 5 explained that if something concerned her, “I can bring it up and he can never say, ‘I thought you were over that already.’ I promise to not hold grudges … but I am not expected [to] keep silent either.”

Expanded theme: Making and refining meaning (NonSPs)

NonSPs’ ongoing healing involved repeatedly making meaning out of their experience, as evidenced by the fact that multiple bloggers wrote and rewrote accounts of the infidelity, its immediate effects, and its impact on their relationship up to that point. Most bloggers looked for and emphasized personal and relational growth they had experienced in healing, such as feeling triggered less often, being able to argue without the infidelity coming up, and making plans together for the future. Blogger 1 wrote, “It doesn’t seem so personal anymore … It feels more like we went through a bad storm or car accident that was scary and painful, but we went through it together and survived it together.” The result of recognizing their healing was increased hopefulness and determination to continue the healing journey.

Expanded theme: Joint re-establishing trust

Through concerted healing work, over significant time couples incrementally re-established trust in their relationship, founded on the belief that they had altered both the individual and any relationship vulnerabilities that led to infidelity, such as patterns of emotional disengagement or not prioritizing the relationship. Blogger 1 explained, “As the evidence stacked up that she wanted to be faithful and that she was structuring her life to make it less likely that she would repeat the same mistakes, I would trust her more.” Blogger 5, who described her partner’s insecurities as creating vulnerability to the infidelity, later observed, “Trust in marriage is not about ‘will he cheat or keep his promises.’ Trust is about having faith that we can communicate our vulnerabilities [and our] emotional and physical needs with each other.” In this regard, Blogger 4, whose partner ‘relapsed,’ cited her partners’ increased ability to communicate his needs and to be responsive to her needs as evidence that she could still rebuild trust with him. Blogger 6 summarized her belief in her husband’s transformative changes at the conclusion of her blog, writing, “I am back to trusting him not to betray me, lie to me, cheat on me. I would bet my life on him never, ever having an affair again. Truly.”

Discussion

Informed by Butler et al.’s (Citation2021) model of couple healing from infidelity, we used deductive qualitative analysis to empirically examine the process of healing from infidelity from the perspective of seven non-straying partners. Our deductively and inductively developed results include evidence that supports, contradicts, refines, and expands Butler et al.’s (Citation2021) clinically based model. We summarize salient supported, refined, and expanded themes based on our analysis. We note that, several of our inductively derived themes lend support for components of healing already present in the hypothesized model but not included as a priori sensitizing constructs. Other inductively derived themes constitute significant expansions or refinements to the hypothesized model, most notably NonSPs’ individual healing and joint contributions to healing.

Supported themes

Attachment betrayal trauma (NonSPs)

Consistent with attachment theory, other research (Fife et al., Citation2008; Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006; Olson et al., Citation2002; Warach & Josephs, Citation2021), and the hypothesized model, despite the NonSPs experiencing infidelity as a traumatic betrayal with subsequent emotional upheaval, attachment bonds (love for their partner and/or concern for their children) led each of them to attempt reconciliation, despite recognizing reasons to leave.

Stabilizing the relationship through containment (NonSPs)

In the early recovery stage, we found evidence for NonSPs stabilizing the relationship by containing their pain, redirecting their anger, and attempting to meet SPs’ needs. All three of these responses are consistent with attachment-oriented behavioral responses and survival responses to trauma (Butler et al., Citation2021; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007). Containment has similarities to what Baucom et al. (Citation2017) referred to as the “flight to health,” where partners attempt to return to normalcy in the relationship without processing the infidelity (p. 209). While Butler et al. (2021) propose that containment is a transitory attachment crisis response facilitating stability, Butler et al. join with Baucom et al. (Citation2017) in warning that chronic containment will preclude healing. Eventual transition to processing the trauma and pain is essential. Our participants confirmed this sense, noting that containment served to preserve the relationship, but itself did not directly lead to healing, either for themselves or for the relationship. Thus, our findings align with Butler et al. (Citation2021) and Baucom et al. (Citation2017). Future research is recommended to identify criteria demarcating boundaries between transitory functional containment and chronic affective suppression that stymies, stagnates, and stalls healing.

Recommitting and supporting NonSPs (SPs)

In early recovery, NonSPs described SPs as recommitting to their marriage and working to repair the damage from the infidelity. Each NonSP expressed that SPs’ recommitment to the relationship was pivotal for healing, which is consistent with both the hypothesized model (Butler et al., Citation2021) and other research (Abrahamson et al., Citation2012; Fife et al., Citation2008). SPs’ reinvestment in the relationship, as evidenced in the couple relationship by emotional availability, responsiveness, and willingness to communicate, and more broadly by spending time with children, was particularly important in beginning the process of re-establishing trust. Our results are consistent with other research suggesting that SPs’ combined reinvestment in the relationship, efforts to change, and partner support (taking up their moral burden), all facilitate couple healing and reinforce NonSPs’ motivation to remain in and work on the relationship (Bird et al., Citation2007; Mitchell et al., Citation2021).

Authentic processing of pain, anger, and ambivalence (NonSPs)

In middle recovery, consistent with Butler et al.’s (Citation2021) framing of containment as a temporary adaptation to be followed by authentic relating around the infidelity, as NonSPs felt emotionally ready and that the relationship was sufficiently stable, they shifted from containing their pain and redirecting their anger to more open processing of these emotions, both personally and with their partner. Our finding that this shift occurred after SPs recommitted to the relationship is consistent with the hypothesized model and attachment theory (Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006). This suggests that containment as we have described it is not the problematic enduring affective suppression Baucom et al. (Citation2017) are concerned with, but a functional, stabilizing, and temporary attachment dynamic serving the couple’s relationship.

Individually—and again supporting the hypothesized model—this processing of emotions, including expression of benevolent, corrective indignation (prosocial anger; Butler et al., Citation2018; Meloy-Miller et al., 2018) allowed NonSPs to begin to move forward from the infidelity, and was thus critical to their personal healing (Butler et al., Citation2021; see also Baucom et al., Citation2017). Relationally, for some this processing led to a surge in tension, distress, and sometimes conflict in the relationship and led several NonSPs to question whether to remain with their partners. NonSPs conditioned their staying in the relationship on their partner’s meaningful effort to take up their moral burden, accepting and offering safe holding of the NonSPs’ pain. This finding is consistent with the hypothesized model and represents a notable departure from and clarification of most clinical literature, which suggests that NonSPs typically question the relationship immediately after discovery rather than months into the healing process (Baucom et al., Citation2017; Fife et al., Citation2008). Our study supports the importance of attending to NonSP relational uncertainty throughout the healing process—recognizing that the greatest vulnerability may occur well beyond discovery. Therapy may provide vital help through offering additional empathic space—relational scaffolding—for NonSPs as they wrestle with their feelings and difficult relationship decisions.

Accepting moral burden or vacillating support (SPs)

While our small sample size limits our ability to discuss different trajectories in healing, we note that some SPs seemed to accept the moral burden of helping their partners by becoming increasingly conciliatory and responsive, whereas others vacillated in their support and exhibited defensiveness or passivity. This is consistent with the hypothesized model (Butler et al., Citation2021), specifically the assertion that the transition out of containment may at first lead to a spike in SP defensiveness or resentment (see also Olson et al., Citation2002). How differing SP responses to moral burden uptake play out in terms of relational healing versus chronic distress and ongoing instability is an invaluable point of focus for future research. NonSPs suggested that vacillation in moral burden uptake could be tied to SPs wanting to just ‘put it all behind them’—whether out of impatience, lack of empathic resonance, or their own distress over the healing process. Therapeutic intervention targeting these areas could lead to improved outcomes.

Refined themes

Ambivalence (SPs)

While some NonSPs described instances of SPs’ transitory ambivalence, all SPs ended the infidelity relatively quickly. This departure from the hypothesized model may be due to a contextual sampling bias—namely, greater SP ambivalence could lead to relationship termination, which would have excluded the NonSPs blog from inclusion in the present study. Regardless, some SPs in our sample engaged in both conciliatory behaviors (e.g., expressing remorse) and minimizing behaviors (e.g., withholding information). This supports the hypothesized model’s emphasis on SPs experiencing ambivalence regarding reconciliation because of their awareness of the “ordeal” entailed in healing, even though they may not overtly consider trying to “escape” the ordeal by leaving the relationship (see also Abrahamson et al., Citation2012).

Joint contributions to healing

Our results suggest that a meaningful refinement to the hypothesized model is making explicit couples’ joint efforts to heal their relationship, such as reinforcing each others’ commitment to the relationship, seeking connection and proximity, and engaging in rituals. This is consistent with other models of healing (Baucom et al., Citation2017; Bird et al., Citation2007). While the hypothesized model assumed that the NonSP would initiate and benefit from seeking connection and proximity, the bloggers emphasized that both partners needed this closeness, suggesting the influence of each partners’ attachment bond (Mitchell et al., Citation2021). Additionally, nearly every blogger reported engaging in a meaning-oriented ritual with their partner to mark a turning point in their healing, such as moving, getting new wedding rings, or renewing vows. Each of these rituals marked a salient shift in healing, as supported by other research identifying the importance of meaning making in healing (Abrahamson et al., Citation2012; Olson et al., Citation2002). Future research should explore effective forms and timing of these rituals.

Expanded themes

Pursuing personal healing (NonSPs)

A notable gap in both the hypothesized model and in other models of couple healing is NonSPs’ efforts and experience of individual healing. Pursuing personal healing, responding to triggers, making meaning, and forgiveness all combine here to provide holistic understanding of NonSPs’ individual healing. NonSPs reported that throughout their experience, their personal healing was intricately wrapped up in their own actions and experience, distinct from their interactions with their partners. While the hypothesized model emphasized the influence of relational attachment dynamics on couple healing, our results suggest the additional role of each partner’s individual actions in healing, but especially those of NonSPs. Although NonSPs appreciated and relied on their partners for emotional support, they nevertheless engaged in their own healing work, even when SPs were committed to the relationship and supportive.

As they pursued personal healing, professional and non-professional support was particularly salient, as others have suggested (Abrahamson et al., Citation2012; Bird et al., Citation2007; Fife et al., Citation2022). Several participants described their blogging as a means to process their experience without needing to continually talk with their partners or others who knew them in real life. This offers a potential expansion to the idea of containment from the hypothesized model, clarifying that containment is perhaps more completely characterized as a “diverted” processing of NonSPs’ experience, away from the couple relationship to other outlets. Sparing the couple relationship reduces the risk of destabilizing it, while diverting the pain allows it to be processed elsewhere. In this way, NonSPs were able to work on their personal healing even before their partners were prepared to offer empathetic support and compassionate witnessing. Nevertheless, consistent with the hypothesized model, our findings suggest that for couple healing to occur, the infidelity must ultimately be processed within the couple relationship.

NonSPs wrote of the infidelity as a traumatic betrayal that led them to experience triggers even years after discovery and reported that they were continuing to pursue personal healing through adaptive responses to triggers and also making meaning of their experience. We join with Baucom et al. (Citation2017) in recommending trauma-informed care that attends to understanding and proactively responding to triggers. The importance of making meaning as a way of coping is well documented, both with adversity generally and with infidelity specifically (Abrahamson et al., Citation2012; Olson et al., Citation2002). In discovering and crafting higher purpose, participant bloggers found it particularly meaningful to share their experiences with others, both to gain support and to offer support to others facing similar challenges.

Lastly, the NonSPs in our sample also emphasized the role of forgiveness in promoting personal and relational healing, in line with other models that emphasize forgiveness as a primary healing outcome (Fife et al., Citation2011; Laaser et al., Citation2017). Current models of forgiveness that suggest that the decision to forgive may precede affective, felt forgiveness are particularly relevant (Enright & Fitzgibbons, Citation2015). Our results suggest that early forgiveness and continuing forgiveness may be distinct in function and depth, yet both are important along the longitudinal trajectory of first holding the couple relationship together and finally healing. Conceptually, some early expressions of forgiveness may have been influenced by containment, a desire to bypass the pain and promote stability. In contrast, forgiveness catalyzed by SPs’ efforts to repair the relationship evidenced a fuller processing of emotional experience.

Clinical implications

The primary implication of our findings is that healing from infidelity involves interwoven couple-level and individual-level processes. Therapists working with couples seeking healing from infidelity should carefully structure therapy so as to actualize both dimensions, incorporating not only enactments and couple-level processing, but also individual work with each partner or collaboration with personal therapists.

Supporting the hypothesized model, our results suggest that clinicians should be attuned to efforts by NonSPs to stabilize the relationship early in recovery (e.g., containment, Butler et al., Citation2021). For some NonSPs, this tendency may be tied to concerns about the current fragility of the attachment bond; for others, these behaviors may predate the infidelity and be more ingrained. We recommend that clinicians meet individually with NonSPs to (a) assess for the presence of these relationship stabilizing responses—particularly their duration—and (b) identify the relationally beneficial yet potentially personally harmful results (e.g., relational imbalance and inequity), and then (c) work collaboratively with the couple to facilitate authentic expression and processing of the pain as soon as the relationship is sufficiently stabilized (see also Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006). Our results support the possibility that temporary containment can be a functional attachment response stabilizing the relationship, while also highlighting the necessity of couples transitioning to emotional processing when both partners are ready (Butler et al., Citation2021). To facilitate this transition, therapists can validate and affirm the right of NonSPs to seek healing, normalize stabilizing responses while providing psychoeducation about the necessity of processing the infidelity, and help the NonSP engage with supportive others.

During middle and continuing recovery, structured enactments may play a critical role in helping de-escalate emotionally reactive interactions, emotionally engage partners and invite softening, facilitate expression of underlying attachment needs, and promote attachment engagement and relational responsiveness (Davis & Butler, Citation2004; Makinen & Johnson, Citation2006; Tilley & Palmer, Citation2013). Structured enactments can be adapted to couples’ emotional reactivity and skills, progressing from shielded enactments, where communication passes through the therapist, to eventual autonomous couple interactions without direct therapist intervention (Butler & Gardner, Citation2003). Healing is further facilitated as SPs accept responsibility and accountability for their actions and their moral burden in helping healing. In relationship enactments, therapists play a vital role in assisting SPs who struggle to provide consistent support as NSPs verbalize their deep sense of betrayal and loss of trust. Clinicians can normalize the ongoing, labile experience of healing and foster patience, empathy, and persistence.

Limitations

Our research used a naturalistic, longitudinal dataset spanning months of consistent posting to examine the process of couple healing from infidelity. However, limitations recommend both further research and tentativeness in applying our findings. First, our small, non-representative sample requires that the findings of our study be viewed as tentative and preliminary. Second, because all the blogs were written by non-straying partners, with only occasional comments from straying partners, the data were weighted toward non-straying partners’ perceptions of and contributions to couple healing. This could leave out important aspects of healing (e.g., potential early SP ambivalence, SP personal healing). Third, due to the nature of internet-based research, most sociocultural variables for our bloggers are uncertain, decontextualizing their responses and potentially eclipsing salient differences.

Conclusion

The findings from our study lend support to multiple aspects of Butler et al.’s (Citation2021) model, including periods of relationship ambivalence for one or both partners, NonSPs seeking to stabilize the relationship through containing their pain and redirecting their anger, and SPs taking up their moral burden in healing by actively supporting NonSPs in processing their experience. Our findings expand on the hypothesized model by incorporating the critical importance of NonSPs’ efforts to heal as individuals, as well as aspects of couples’ joint contributions to healing perhaps only implicit in the hypothesized model. We believe that this refined model can usefully inform effective clinical intervention.

Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (99 KB)References

- Abrahamson, I., Hussain, R., Khan, A., & Schofield, M. J. (2012). What helps couples rebuild their relationship after infidelity? Journal of Family Issues, 33(11), 1494–1519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11424257

- Baucom, D. H., Pentel, K. Z., Gordon, K. C., & Snyder, D. K. (2017). An integrative approach to treating infidelity in couples. In J. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Foundations for couples’ therapy: Research for the real world (pp. 206–215). Routledge.

- Bird, M. H., Butler, M. H., & Fife, S. T. (2007). The process of couple healing following infidelity: A qualitative study. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 6(4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/J398v06n04_01

- Butler, M. H., & Gardner, B. C. (2003). Adapting enactments to couple reactivity: Five developmental stages. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01209.x

- Butler, M. H., Gossner, J. D., & Fife, S. T. (2021). Partners taking turns leaning in and leaning out: Trusting in the healing arc of attachment dynamics following betrayal. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2021.1926388

- Butler, M. H., Meloy-Miller, K. C., Seedall, R. B., & Dicus, J. L. (2018). Anger can help: A transactional model and three pathways of the experience and expression of anger. Family Process, 57(3), 817–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12311

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Davis, S. D., & Butler, M. H. (2004). Enacting relationships in marriage and family therapy: A conceptual and operational definition of an enactment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 30(3), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01243.x

- DuPree, W. J., White, M. B., Olsen, C. S., & Lafleur, C. T. (2007). Infidelity treatment patterns: A practice-based evidence approach. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(4), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180600969900

- Enright, R. D., & Fitzgibbons, R. P. (2015). Forgiveness therapy: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association.

- Fife, S. T., Theobald, A. C., Gossner, J. D., Yakum, B. N., & White, K. L. (2022). Individual healing from infidelity and breakup for emerging adults: A grounded theory. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(6), 1814–1838. doi:10.1177/02654075211067441.

- Fife, S. T., Weeks, G. R., & Gambescia, N. (2008). Treating infidelity: An integrative approach. The Family Journal, 16(4), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480708323205

- Fife, S. T., Weeks, G. R., & Stellberg, F. J. (2011). Facilitating forgiveness in the treatment of infidelity: An interpersonal model. Journal of Family Therapy, 35(4), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2011.00561.x

- Gilgun, J. F. (2014). Chicago School traditions: Deductive qualitative analysis and grounded theory. Amazon.

- Gilgun, J. F. (2019). Deductive qualitative analysis and grounded theory: Sensitizing concepts and hypothesis-testing. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of current developments in grounded theory (pp. 107–122). Sage.

- Knapp, S. J. (2009). Critical theorizing: Enhancing theoretical rigor in family research. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 1(3), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00018.x

- Laaser, D., Putney, H. L., Bundick, M., Delmonico, D. L., & Griffin, E. J. (2017). Posttraumatic growth in relationally betrayed women. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(3), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12211

- Labrecque, L. T., & Whisman, M. A. (2017). Attitudes toward and prevalence of extramarital sex and descriptions of extramarital partners in the 21st century. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 31(7), 952–957. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000280

- Makinen, J. A., & Johnson, S. M. (2006). Resolving attachment injuries in couples using emotionally focused therapy: Steps toward forgiveness and reconciliation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1055–1064. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1055

- Meloy–Miller, K. C., Butler, M. H., Seedall, R. B., & Spencer, T. J. (2018). Anger can help: Clinical representation of three pathways of anger. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 46(1), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2018.1428130

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford.

- Mitchell, E. A., Wittenborn, A. K., Timm, T. M., & Blow, A. J. (2021). Examining the role of the attachment bond in the process of recovering from an affair. American Journal of Family Therapy, 49(3), 221–236. https://doi-org.lib-e2.lib.ttu.edu/10.1080/01926187.2020.1791763

- Olson, M. M., Russell, C. S., Higgins-Kessler, M., & Miller, R. B. (2002). Emotional processes following disclosure of an extramarital affair. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28(4), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2002.tb00367.x

- Saldana, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Schade, L. C., & Sandberg, J. G. (2012). Healing the attachment injury of marital infidelity using emotionally focused couples therapy: A case illustration. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 40(5), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2011.631374

- Tilley, D., & Palmer, G. (2013). Enactments in emotionally focused couple therapy: Shaping moments of contact and change. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 39(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00305.x

- Warach, B., & Josephs, L. (2021). The aftershocks of infidelity: A review of infidelity-based attachment trauma. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 36(1), 68–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2019.1577961