Abstract

In recent years artistic practice has developed into a major focus of research activity, both as process and product, and discourse in various disciplines have made a strong case for its validity as a method of studying art and the practice of art. This paper presents a methodological approach to creative practice as research, and includes an overview of the different types of practice-related research currently undertaken across a variety of disciplines; discussion of the purposes and applications of creative practice research; and the Practitioner Model of Creative Cognition sample methodology I developed through my own creative practice research. The online version of this paper is a living discussion of practice-based methodologies in creative practice research, included as part of the special issue The Disrupted Journal of Media Practice, and invites reader contributions and discussion for future revisions.

Introduction

Footnote1Art, literary, music, and film analysts examine, dissect, and even deconstruct the art that we create in order to study culture and humanity, pulling the techniques and references and motivations apart to develop knowledge of how works of art relate to the culture and society in which they are produced, as well as to the development of particular art forms over time. Practice-related researchers push this examination into a more direct and intimate sphere, observing and analysing themselves as they engage in the act of creation, rather than relying solely on dissection of the art after the fact.

The practice-related method presented here was developed through my research into creative practice, specifically in creative writing. While writers have always been researchers – conducting background research, observing human interaction, analysing literary techniques – creative writing as a field of academic inquiry is a relatively recent emergence. As a result, when I began my research in the field, there were few existing methods from which to draw.

Practice-related research is an accepted methodology in medicine, design, and engineering (where it is often called ‘action research’ [Reason and Bradbury 2001], referring to field-based research and participatory experiments as opposed to laboratory tests). While it has always been present to some extent in the arts and humanities, recently artistic practice has developed into a major focus of research activity, and several recent textsFootnote2 as well as discourse in various disciplines have made a strong case for its validity as a method of studying both the process and product of art. Note, however, that this paper defines a methodological approach rather than strictly defined methods; I offer a framework for practice-related researchers to apply to a variety of research questions about creative practice.

The method described in the following pages is one I devised based largely on this approach to practice-related research, combined with my own knowledge as a one-time researcher in biological anthropology. As a scientist, I developed knowledge about my subject through protocol-based testing and observation, always with clearly defined methods for clearly stated research goals: to study and understand the processes and interactions of life. As a writer, I found parallel processes of experimentation across various forms of media, text, art, and performance. When we as practitioners pursue our art as research, we not only offer insights into art and the practice of art as it occurs, but can throw new and unexpected light onto a range of topics including cognition, discourse, psychology, history, culture, and sociology.

As creative practice expands as a field of academic research, there is a need to establish an ongoing discourse on and resource for appropriate practice-based methodologies. This paper is the opening volley in that discourse, and includes an overview of the different types of practice-related research currently undertaken across a variety of disciplines. The online version of this paperFootnote3 is a living discussion of practice-based methodologies in creative practice research. As such it includes all materials and discussions from this print article, as well as the opportunity for readers to comment on the various sections, contribute toward ongoing revisions, and expand upon the sample methodology with their own examples. It also includes links to further research and teaching resources.

The Practitioner Model of Creative Cognition

This paper presents a methodology for creative practice-based research, based on my own research into creative digital writing (and using that work as examples where helpful). It begins with an examination of practice-based research, then compiles a model of practice-based research that pulls from the strengths of various methods of observation and analysis from several different fields, a targeted combination of auto-ethnomethodology, reflection applied to cognitive composition and creativity models, and post-textual media-specific analysis of the creative artefacts. The following sections examine each of these models of research, followed by the combined methodology model that is not only appropriate to the field of creative digital writing, but one that can be applied to practice-related research in a wide array of creative practice projects.

Practice-Based Research

Practice-related research can be hard to define, as the notion of ‘practice’ encompasses many potential activities from artistic to analytical. As such, practice-related research is referred to in many different ways; in related literature, ‘the terms “arts-based research”, “practice-based research”, “practice-led research”, “practice-centered research”, [and] “studio-based research” are more or less used synonymously’ (Niedderer and Roworth-Stokes Citation2007, 7). The term ‘practice-led research’ is typically the one used most consistently in the literature (cf. Perry Citation2008; Stewart Citation2006; Smith and Dean Citation2009; Sullivan Citation2009), perhaps because it puts the creative practice ahead of the research, a horse before a cart, as it were. This section defines four categories of practice-related research, according to the relationship between the creative practice and the communication of scholarly knowledge generated by such practice.Footnote4

The first two categories are likely the most familiar to the arts and humanities field: practice-and-research, and practice-as-research. Practice and research have long gone hand-in-hand in various arts disciplines; poets draw from their own creative practice in their textual analyses and criticisms of others’ poetry, as do creative writers and dramatists. This approach, practice-and-research, is the most established in literature departments, journals, and publishing houses. The practitioner-researcher’s creative artefacts and critical outputs are disseminated separately, while knowledge acquired from the creative practice informs the critical explorations. In some fields, particularly music, practice-as-research is also common, wherein the research consists entirely of the creative practice, with no explicit critical exegesis deemed necessary. The creative artefact is considered the embodiment of the new knowledge; emphasis is placed on creative exploration and innovation in the given artistic practice.

Where we begin to tread new territory is in the realms of practice-led and practice-based research. These categories of practice-related research ‘[involve] the identification of research questions and problems, but the research methods, contexts and outputs then involve a significant focus on creative practice’ (Sullivan Citation2009, 48). The outcomes of such research are intended to develop the individual practice and the practice of the field, to build theory related to the practice in order to gain new knowledge or insight (Niedderer and Roworth-Stokes Citation2007, 10; Sullivan Citation2009, 48). Linda Candy makes a distinction between these two, though it can often be a rather blurry line in actuality (2006).Footnote5 Practice-led research focuses on the nature of creative practice, leading to new knowledge of operational significance for that practice, in order to advance knowledge about or within practice. The results of practice-led research may be communicated in a critical exegesis without inclusion of the creative artefact, though the creative practice is an integral part of the research.

In practice-based research, the creative artefact is the basis of the contribution to knowledge. This method is applied to original investigations seeking new knowledge through practice and its outcomes. Claims of originality are demonstrated through the creative artefacts, which include musical performances, musical recordings, fiction, scripts, digital media, games, film, dramatic performances, poetry, translation, and other forms of creative practice. The creative artefact is accompanied by a critical discussion of the significance and context of the claims, and a full understanding can only be achieved through the cohesive presentation of the creative artefact and the critical exegesis.

Put simply, in practice-based research (hereafter ‘PBR’), the creative act is an experiment (whether or not the work itself is deemed ‘experimental’) designed to answer a directed research question about art and the practice of it, which could not otherwise be explored by other methods. We create art to connect with others, to connect with ourselves, and often just for the sake of it. We experiment with our art in order to push boundaries, to ask questions, to learn more about our art and our role within it. This is nothing new. What emerges, then, from this methodology, is the exegesis that accompanies the creative work: that knowledge that has remained implicitly within the artist, made explicit and seated within the context of the scholarly field.

Graeme Sullivan’s 2009 model identifies a framework of four key areas in which a practice-led or -based research methodology is applicable and appropriate. The first is theoretical, in which the practitioner-researcher is exploring research issues and problems; this paper can be seen as an exegesis of theoretical PBR, as the methodology it communicates was developed during the composition of a significant work of creative practice as experiment, in the absence of any existing methodologies that could be applied. In Sullivan’s second category, conceptual, ‘artists give form to thoughts in creating artefacts that become part of the research process’ (Ibid, 50); often, this type of practice-related research is conducted as an attempt to understand the creative artefacts themselves, rather than to respond to a gap in scholarly technique or cultural context. A writer may be interested in the affects of different narrative perspectives on a short story, or a sculptor might explore the affordances of different sculpting media; in my work, I am interested how constructing narratives in different media affects me as a writer, and the structures of the stories that result. Dialectical practice-related research explores the human process of experiential meaning-making: how we connect to other minds through the middle-men of artistic media, how art conveys meaning beyond mere communication of actants and/or events. The final category is contextual, in which the practice is an effort to bring about social change (morality plays, for example).

The remainder of this model of practice-based methodology will focus on practice-based research as the foundation approach, primarily in the category of conceptual (though, as noted, other results do arise serendipitously; the categories are not mutually exclusive). Embedded within this foundation are methods of observation and analysis that provide a far more robust framework than relying solely on post-composition reflection for translating the implicit knowledge practitioners naturally develop through their creative practice into an explicit exegesis that the field can engage with. This framework consists of a modified ethnomethodology, cognitive analysis, and media-specific post-textual analysis.

Auto-ethnomethodology

Reflective analysis is a method practitioners frequently apply to their creative projects. Reflection, however, dependent as it is upon memory, and conducted after the creative act rather than during (or as close to as possible), can be an unfortunately fallible method, and often fails to offer insights into the cognitive processes of creation that are frequently the focus of PBR. Ernest A. Edmonds, et al. note, ‘[t]he investigation of creativity as it takes place in naturalistic settings has been difficult to achieve and most studies of creativity draw on retrospective accounts of the creative process’ (2005, 4). While some researchers decry any self-observation or reflection as inherently biased (cf. Bochner Citation2000), in PBR subjectivity is not as problematic as memory and lack of inquiry-directed observation. Thus, I call for the employment of a self-directed form of ethnomethodology during the composition of the texts, in the form of a research log (noting insights, process, difficulties), and draft materials and revision notes (which can later be analyzed as in situ utterances). Together, these methods of documentation constitute a ‘creative analytical processes (CAP) ethnography’ in which the creative process and products, and the analytical process and products are deeply intertwined, offering opportunity for insight and nuance into the creative practice through a necessarily subjective record (L. Richardson and St. Pierre 2008).

Harold Garfinkel defines ethnomethodology as ‘the investigation of the rational properties of indexical expressions and other practical actions as contingent ongoing accomplishments of organised artful practices of everyday life’ (1967, 11); ethnomethodologists observe their subjects’ speech and activities within a given context in order to make these actions ‘visibly-rational-and-reportable-for-all-practical purposes (Ibid, vii). Garfinkel is careful not to identify ethnomethodology as method, for, like PBR, its method must be designed on the basis of each individual study. Social scientists practice ethnomethodology when observing people’s everyday activities, in order to use those activities as recordable and reportable data that can then be interpreted for the activities’ temporal features and sequencing, establishment of the subject’s knowledge of setting or activity, establishment and evaluation of models of activity, and evaluation of how people use their knowledge and experience to make decisions or take action. Interestingly, Garfinkel presents Karl Mannheim’s ‘documentary method of interpretation’ (Ibid, 78), which bears significant parallels to the field of semiotics: this method treats the actual appearance of an activity (arguably the signifier) as evidence ‘documenting’ that activity’s underlying pattern (that which is signified). For instance, a writer marking a draft-in-progress with the note ‘Where does this go from here?’ is an observable, recordable signifier documenting the underlying cognitive pattern of composition (signified), which can be examined and interpreted by the observer.

Deborah Brandt argues for just such a practice of ethnomethodology for writers, building upon Linda Flower & John R. Hayes’s 1981 Cognitive Process Model of composition (examined in the next section), wherein the cognitive activity of planning and executing composition activity is mapped as ‘a way of sustaining the social contexts that account for or display emerging understanding’ (1992, 329). Brandt notes that ‘[s]ense-making in writing entails more than producing a coherent and appropriate text; fundamentally, writers must also make continual sense to themselves of what they are doing’ (Ibid, 324). The process of this continual sense-making is often expressed in notes, journal entries, and comments on revised drafts: observable documentation of the composition practice.

Garfinkel also favors observing activities carried out by individuals whose competence is high enough that the activities are taken for granted – essentially, activities that are familiar and practiced, even those with significant cognitive loads – then making the activities visible by applying a ‘special motive’ to make them of ‘theoretic interest’ (1967, 37). This notion is highly suited to an auto-ethnomethodological approach to PBR, as the research often ‘start[s] with familiar scenes and ask[s] what can be done to make trouble’ (Ibid). This methodology calls for the creative practitioner to begin with a familiar activity that has arguably been mastered (in my case, prose writing, whose mastery is evidenced by professional publications and advanced writing degrees), and introduce an unfamiliar element as a ‘special motive’ (e.g., composing stories in prose and electronic versions, the latter being unfamiliar). The documentary method of interpretation — as applied to in situ notes and drafts — in combination with media-specific analysis of the resulting artefacts, offers aspects of theoretical interest to the practice of the particular art (digital writing) and the domain of its scholarly study (transmedia narratology).

In many practice-based projects, autoethnography can also play a role, as creative research questions are often inseparable from artist identity, experiences, and culture. Autoethnography is an approach that seeks to describe and analyze personal experience in order to extrapolate understandings about wider cultural experience (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011); in terms of creative practice, autoethnography can help the practitioner-researcher to extrapolate their artistic experiences to those of the wider artistic community. Many of the methods associated with autoethnography can be applied to PBR, including reflexive ethnographies, narrative ethnographies, and layered accounts (Ibid). The method that I developed for my own practice incorporated aspects of autoethnography, as I documented and logged my experiences as research notes and observations.

While I acknowledge the limitations of self-observation and reflection through autoethnography, it is important to note that PBR is impossible without them. Indeed, reflexivity is key to developing a critical consciousness of how the practitioner-researcher’s identity, experiences, position, and interests influence their creative practice (Pillow Citation2010, 273). I have also attempted to mitigate these limitations in this methodology by stipulating that the practitioner-researcher A) approach the creative activity from a clearly defined research question; B) observe his/her activities in situ, but interpret these observation records (creative notes, drafts, research logs) after a time period that allows for a distanced perspective; and C) supplement these observations of process with media-specific analysis of the creative artefacts themselves (as discussed in a later section). A clearly defined research question not only helps to determine the scope of the creative practice, it provides a framework for examining the creative activity. Thanks to this focused frame, the practitioner-researcher can more easily distinguish and recognize the effects of the ‘trouble’ of the unfamiliar ‘special motive’ on his/her familiar activity. This benefits not only real-time observations, but also reflection on creative activities and later interpretation of the observation notes, creative drafts, and research logs. Similarly, by distancing the practitioner-researcher both in time and perspective (the latter by applying post-textual analysis) from the creative practice, s/he is able to identify patterns in the creative process and narrative artefacts that may not have been apparent while the activity was underway. Combination of methodological approaches, therefore, provides a more robust approach to examination of creative practice than reflection or post-textual analysis provide on their own.

Cognitive Approach

Not all PBR projects seek answers to questions about how the artist thinks and conceives of a work. Many focus on the actual steps and behaviours of an artist’s activities, without attempting to dive into the cognitive processes underlying those actions. Others still focus on creative outcomes: how do the materials shape the artefact, how do techniques influence the art, how does discourse enter into the work, etc. My research interests, however, lie in large part in the interior landscape of the creative mind: where do ideas emerge, how does the imagined work translate into the final artefact, how do the artists’ thoughts and experiences shape the creative work, and more. In order to pull apart questions about creative cognitive processes, it is important to establish a shared framework that allows analysis and ongoing discourse; my Practitioner Model of Creativity (below) builds upon previous models of cognition to provide a framework for these questions in PBR in the arts.

Linda Flower & John R. Hayes’s 1981 Cognitive Process Model of composition serves as a base for evaluating composition activities. Flower & Hayes identify three key cognitive elements of the writing process: the writer’s knowledge of topic, audience and context (also termed the ‘long-term memory’); the task environment (including everything external to the writer, the rhetorical problem, and the developing text); and the writing process itself (including planning activities, the actual writing of the text, and ongoing revision of the text). This model is a hierarchical model of composition, as opposed to a stage-based model: it describes the more fluid mental processes of composition, rather than a linear progression of activities from one stage to the next. For example, a writer is likely to engage in goal setting for their text at any point in the composition, reshaping the goals for the text as review of the produced text enhances the writer’s understanding of the rhetorical situation.

The model is not a perfect one, as it is largely self-contained to the particular text currently underway, and does not explicitly account for external influences such as interruptions, long-term breaks in the creation process, or simultaneous work on other texts. It is also notable that this cognitive process model does not in the first instance incorporate multimodal forms of creation, which Andy Campbell calls a ‘liquid canvas’ (2011, n.p.); incorporating Flower & Hayes’ 1984 Multiple Representation Thesis, however, offers a more fluid aspect. This theory offers relevant insight into the development of Gunther Kress’s ‘synaesthetic process’ (1998, in Fortune Citation2005, 53) necessary for multimodal composition: essentially, that it is already inherent in the process of composition. ‘Writers at work represent their current meaning to themselves in a variety of symbolic ways’, including nonverbal, procedural, and imagistic representations of ideas and knowledge (L. Flower and Hayes Citation1984, 129). The process of translating this abstract knowledge into written text is a difficult one, and the authors note that multimodal texts offer a significant advantage in that ‘some goals are better accomplished with different representations … Which representation is in force at a given moment is probably drven [sic] by a combination of one’s goals at that moment and the forms of the particular representation already stored in memory’ (Ibid, 151). The argument can be made here that composing multimodally engages more naturally and fluidly with the planning process of composition.Footnote6 Alan Sondheim (Citation2006) and Jenny Weight (Citation2006) respectively echo this thesis in their practice-based explorations of their own digital composition process, and Jason Ranker likewise describes this effect in his 2008 ethnographic study of students composing in digital media.

Embedding this Cognitive Process Model within the framework of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s 1996 Systems Model of Creativity assists in consideration of external influences. The Systems Model defines creativity as occurring when ‘a person, using the symbols of a given domain … has a new idea or sees a new pattern, and when this novelty is selected by the appropriate field for inclusion into the relevant domain’ (Ibid, 28); this creative novelty either changes the domain, or transforms it to a new one. Domain encompasses a set of symbolic rules and procedures that identify an area of knowledge; field is the individuals who act as gatekeepers for that domain; person is used to identify the individual engaging in the creative activity, which Csikszentmihalyi notes requires an internalization of the system — familiarity with the domain and field in which the creative act is engaged. According to this model, an act, idea, or product is not creative unless it is acknowledged by the relevant domain and field (which can be difficult, depending upon the domain and field’s ability to recognize and incorporate the novelty’s validity and implications). Accepting that the person engaged in the act of composition employs Flower & Hayes’s ‘long-term memory’, and that this must, according to Csikszentmihalyi, incorporate knowledge of domain and fieldFootnote7, offers a way to account for these external influences in the cognitive processes of composition.

Another gap in Flower & Hayes’s model rests in the ‘generating’ box. Theirs is an encapsulated model of composition, offering a useful overview of the major categories, but giving little attention to the age-old fan question: Where do ideas come from? Incorporating The Geneplore Model (Finke, Ward, & Smith 1992 in Finke Citation1996) within the overarching framework of the ‘generating’ phase of the Cognitive Process Model offers additional hierarchical levels of exploring the creative writing process. In this model, the authors propose a cycle of idea generation and exploration, which, like Flower & Hayes’s model, can be revisited as and when needed. The Geneplore Model’s generative processes mirror Flower & Hayes’s Multiple Representation Thesis (1984): ‘in addition to visualised patterns and object forms, [generative processes] may include mental blends, category exemplars, mental models, and verbal or conceptual combinations’ (Finke Citation1996, 385). The generative process is a brainstorm of ideas pulling from existing examples, recombination of elements from those exemplars, and novel approaches to the rhetorical problem. The resulting pre-inventive structures can then be explored and interpreted, then reshaped as needed (per rhetorical situation, which includes product constraints) through further generative processes. For instance, this framework offered insight into how the cognitive effects of immersion in digital tools and environments led to fragmentation and layers of narration in my own work (Skains Citation2016b).

Finally, an aspect of the composition process that should be incorporated is serendipity, defined as ‘a process of making a mental connection that has the potential to lead to a valuable outcome, projecting the value of the outcome and taking actions to exploit the connection, leading to a valuable outcome’ (Makri and Blandford Citation2012a, 2, emphasis original). Arguably, serendipity is the confluence of cognitive activity and external stimulation that most often leads to so-called ‘eureka moments’ for creators. S. Makri & Ann |Blandford (Citation2012a; Citation2012b) outline a model identifying this cognitive process as something more than luck; rather, it is the convergence of the knowledge and experience to make the mental connection and to recognize the significance of that connection, with the skills necessary to exploit the connection and produce a worthwhile outcome or artefact. Serendipity is likely behind the advent of many narrative evolutions, such as the combination of genres into new forms (tech-noir, space opera); the concept also enabled me to analyse the effects of digital appropriation in my multimodal fiction, digging deeply into how an idea developed and evolved through the processes of creation (Skains Citation2016a).

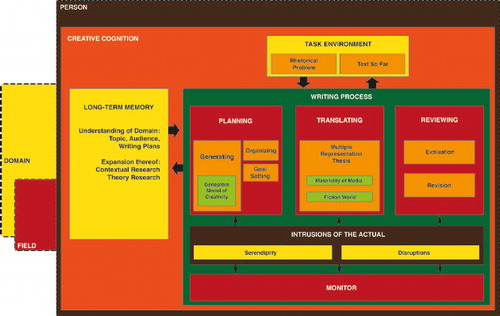

I have gathered these cognitive and creativity models into a cohesive structure that best represents the composition context and cognition: the Practitioner Model of Creative Cognition. This model is based upon the strong foundation provided by Flower & Hayes’s Cognitive Process Model (1981), but widens it somewhat beyond the internal cognitive processes to incorporate the overall system of the practitioner’s creative context using Csikszentmihalyi’s Systems Model of Creativity (1996), allowing for the examination of external influences upon the writing process.

Makri & Blandford’s (Citation2012a; Citation2012b) model of serendipity is incorporated as a mediating function of the monitoring process, where expanding awareness of the domain, the field, and the emerging text converge to form an optimal state for serendipitous mental connections and discoveries. Within the generating process, I have embedded the Geneplore Model, in order to unpack the aspect of how ideas are shaped and remodeled (Ward, Smith, & Finke in Finke Citation1996). Flower & Hayes’s Multiple Representation Thesis (1984) offers insight into the translation process, whether the practice is mono- or multimodal. The translation process also now includes considerations of materiality; though materiality also clearly comes into play in the ‘product constraints’ aspect of the Geneplore Model, it is a significant factor in the translation of narratives, particularly multimodal narratives.

Similarly, the fiction world has been embedded into the translation process as a distinct element, drawing from Todd Lubart’s argument that the writer in the process of translation is constantly shifting between the writing world and that of the fiction: ‘[t]he fiction world seems to involve productive thinking, improvisation, and a lack of reflective, evaluative thought … In contrast, the writer’s world is active, critical, and directive’ (2009, 159). While consideration of the fiction world is inherent in monitoring, evaluating, and reviewing the text produced so far, there is also a specific aspect of translation in which the fiction world plays out independently from the writer’s goals and plans, and thus is worth additional consideration in the model.

This is a model formulated from introspection, self-observation, and reflection upon my own artistic practice, based upon the models discussed in this section; it has not been drawn from larger ethnomethodological studies of other practitioners at work. As such, it may be subject to future adjustments, and it may not be applicable to every individual. By drawing upon more widely accepted models, and integrating the insight of an experienced practitioner engaged in a targeted, practice-based project, however, the Practitioner Model of Creative Cognition gains validity.

Post-textual Analysis

As discussed above, post-textual analysis provides additional insight into the practitioner’s process and work, as well as adding robustness to auto-ethnomethodological observations. Post-textual analysis methods will vary according to the art, genre, practice, and/or research question at hand; my research is particularly interested in fictional narratives and digital writing. As such, several seminal theories provide a foundation for examining the creative texts. Narratology offers three key directions of analysis: transmedia narratology, largely based upon the theories of Marie-Laure Ryan (Citation2006); cognitive narratology, as presented by David Herman (Citation2007); and unnatural narration, based upon the work of Brian Richardson (Citation2006), Jan |Alber, et al. (Citation2010; 2012), Jan Alber & Rüdiger Heinze (2011), and Alice Bell & Jan Alber (2012). Transmedia narratology offers insights into the techniques and structures a text utilizes across and within media, which are useful for comparing creative artefacts across a variety of forms and media. Cognitive narratology enables yet another approach to understanding the process of composition, complementing the auto-ethnomethodological observations and interpretations. Theories of unnatural narration contextualize digital works (which remain largely outside of natural narration and convention) within the larger literary domain, as well as offering a specific framework to analyse the evolution of narrative practice into techniques with which the writer might not have previously engaged.

Within the overarching theoretical framework of narratology, the base for examination of the creative artefacts for meaning-making lies in N. Katherine Hayles’s 2002 media-specific analysis (MSA), which facilitates analysis of the materiality of the multimodal texts, and how that materiality shapes the resulting narrative. This MSA includes semiotic analysis of visual grammar and design (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006), of hyperstructures such as navigation and interactivity (Ryan Citation2006; Bouchardon and Heckman Citation2012), and of source codeFootnote8 (Marino Citation2006; Montfort Citation2003; Montfort Citation2011). This approach is applicable not only to a digital work as displayed, in order to examine the effects of digital media upon the works themselves, but also source code, in order to discuss aspects of process and composition.

Clearly, the theories identified here are applicable to a specific project, an investigation into how shifting to digital writing affects a creative writer’s process and narrative. Research projects should employ a base of theoretical research appropriate to the area in question in both their research design and post-textual analysis.

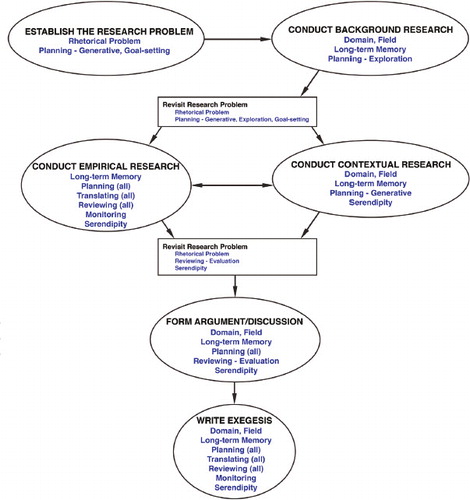

Outline of Practice-Based Method

The method I propose (), drawn from the combination of these ethnographic and analytical approaches, is based upon the Practitioner Model of Creative Cognition presented in . The basic method is to engage in the creative practice in order to explore a research question: how does applying something unfamiliar/new/different to a familiar act/practice affect the practitioner’s process and the creative artefacts? In addition to the creative practice, significant contextual research is generally warranted in the scholarly domains pertinent to the creative project, including close readings of extant creative works as well as awareness and understanding of relevant critical theory. This research not only contributes toward contextualization and analysis of the creative work, it also has significant impact upon the creative process and artefacts. What follows in this section is a detailed overview of the entire method; used in combination with the Practitioner Model of Creative Cognition, it serves as a robust foundation from which to conduct PBR in the creative arts.

Figure 2. Outline of Practice-based Research Method. Elements in blue refer to the Practitioner Model of Creative Cognition outlined in .

Establish the Research Problem

Establishing the research problem, which could be termed the overall rhetorical problem of the entire project, engages the processes of planning (idea generation and goal-setting). While this initial step appears quite straightforward — identify the area of interest, identify key gaps in knowledge, and formulate a research question designed to fill those gaps — in PBR this stage can be nebulous. It can be difficult to identify gaps when the researcher is engaged in an entirely new area or creative endeavor, as a basic level of knowledge and experience is required to, in essence, know what it is we do not yet know. PBR is often a process of exploration and discovery, with many key insights arriving via serendipity, rather than as part of experiment design. Thus, the initial research question is often vague and typically open-ended, to permit flexibility in the practice and space for such serendipitous discoveries to occur.

In my project, the research question was: How does shifting from an established prose writing practice to a new digital composition practice affect the writer’s process and the resulting narratives? This question established a rhetorical situation and implied specific goals: the need for creative texts that permitted exploration and analysis that would answer the question. Thus, the creative text was designed to be coherent as a print novella, yet modular in the digital version, which enabled each digital chapter to experiment with a different digital platform. In order to facilitate an informed approach to the creative practice, however, a fundamental grounding in the domain was required: background research.

Conduct Background Research

This phase of the research is fairly straightforward. It is intended to firmly ground the researcher’s long-term memory in knowledge of the relevant domain, in terms of both critical theory and contextual creative works. This enables the practice-based researcher to ‘know what she doesn’t know’, in order to identify gaps and to engage fully in the planning process: generating and exploring ideas and setting goals for the creative practice. This stage is also commonly known as a literature review, and has the same purposes. With the long-term memory bolstered by this increased awareness of domain, the research question can be revisited to determine whether it remains pertinent or needs to be revised.

In my project, the research question itself remained valid; the background research into electronic literature and specifically digital fiction served largely to promote the planning process of the creative work. Exposure to and close readings of digital fictions (in various platforms such as Flash, interactive fiction, Javascript, hypertext, etc.) offered a reader’s perspective on the genre. I was able to identify key aspects that inspired me or added meaning in these texts, in order to plan their incorporation into my own works. These aspects included meaning-making through visuals (imagery and layout), reader participation (interactivity, contribution to narrative), and navigational structures.

Conduct Empirical Research / Continue Contextual Research

The major phase of research is led by the creative practice, engaging in all aspects of the creative cognitive process. In order to explore the main research question, the practitioner-researcher designs a creative project that appeals to him/her in his/her particular art/genre/form that will foster insights into the process of composition, and that will permit a uniquely practice-based perspective on the question at hand. This is where PBR enters its most unpredictable phase: creative work often diverges quite significantly from its initial concept for a variety of reasons, including time, tools, affordances, materiality, subsequent inspiration (and its evil counterpart, the lack thereof), and other ‘whims of the muses’. What is important in this phase is to remain open to these new directions – to serendipity – and to maintain the in situ research log and observation notes throughout.

It is also worth noting there may be significant effects on the composition process of continuing contextual research in theory and creative works. It could be argued that continuing this contextual research while still engaged in the creative work introduces confounds, raising the question: what proportion of the practitioner’s process and creative changes are due to the newly introduced ‘special motive’, and what is due to his/her growing long-term memory? I would respond that in such qualitative studies as these must be, quantifying these effects is not possible, and likely not informative in any case. The benefits of further engaging in the new domain weigh far more heavily: the creative artefacts benefit from the practitioner’s increased awareness of their chosen domain, and the critical examination benefits from serendipitous connections s/he can make while still engaged in the creative practice.

Form Argument Leading to Exegesis

The research question can be revisited and refined at any point in the PBR process, and I would argue that it should be frequently examined. As discussed previously, PBR is given to exploration and significant moments of discovery, which are largely unpredictable at the start of the project. Thus serendipity can lead to new perspectives on the research, reshaping the project goals throughout. As the primary research activities begin to draw to a conclusion, these serendipitous connections begin to emerge as answers to specific aspects of the research question. For instance, a wholly serendipitous connection necessitated a significant refinement to my research question, presenting a previously unconsidered angle — How does appropriation affect narrative? — as I discovered that appropriating the digital resources available online significantly affected my creative artefacts, and determined to dig deeper into what those effects were (Skains Citation2016a). Again, the need to remain open to these serendipitous connections throughout the practice-based project is essential, as is the habit of recording even the mildest of these mental connections so they may be examined in more depth later.

Argument formation and exegesis are set out here as a final step in the research method, though it is clear that the researcher is engaged in argument formation throughout the primary research phase as discoveries are made and serendipity occurs. Nevertheless, more thorough post-textual analysis of the creative artefacts is required to deepen the understanding of these discoveries, and directed critical research is required to contextualize the conclusions within the domain. Thus a new round of research is called for as needed during argument formation and exegesis write-up, which bears strong resemblance to the traditional practice of post-textual analysis and discourse. The exegesis draws upon relevant aspects of the primary and secondary research as required for specific arguments: auto-ethnomethodological observations, post-textual analysis (of both the creative artefacts and contextual creative works), and critical theory.

Conclusion

In this manner, the various strengths of PBR, ethnomethodology, cognitive process, and post-textual analysis are combined into a robust method of evaluating the activities of the practitioner-researcher. While many of the aspects detailed in this paper may be more or less applicable to different projects (the particulars of post-textual analysis theory, for instance, are likely to be highly individual to each project), the overall framework is widely applicable to a broad array of creative endeavours. The limitations of reflective analysis and self-observation are offset by a directed research plan and post-textual examination of both creative artefacts and in situ notes and drafts. The resulting creative work and critical exegesis are thus bound inextricably together, informing one another in their communication of knowledge just as the research and creative practice informed one another. The resulting text can and should consist of both elements, the creative and the critical.

Practice as an empirical form of research, while common in fields such as design, engineering, and medicine, is a relatively recent innovation in the humanities, and particularly in the academic study of literature and writing. These fields, for various reasons, have long kept the creative act separate from the study of both the composition process and the creative work itself, apart from the insights applied by writers and artists who are also scholars. Yet artists – whether student, amateur, or professional – are notably keen to know how creativity works. Where do great ideas come from? How and why do we choose this narrator versus that one, this medium over the other? How does intent translate into text, and how does text translate into intent? Answering these questions through observation and/or post-textual analysis is, at best, conjecture; at worst, it is impossible. It may even be impossible for the creator his/herself (through the process of reflection, or answering such questions as those posed by readers), as quite often our attention is on the creative act, rather than the metatextual level of observing ourselves at work.

PBR, and this methodology in particular, provide us with a robust, nuanced research approach to help answer these fundamental questions about practicing and performing art. As interest in this particular combination of practice and research continues to grow, it is important that the critical knowledge developed through creative practice is based in a clear, strong, carefully considered methodology, rather than as an afterthought. Doctoral candidates should not expect to receive a research degree merely for creating an artwork and then reflecting upon it, as that does not meet the criterion of offering new knowledge to the domain; it might be new knowledge to the candidate, but it is also applicable only to the candidate, rather than the domain as a whole. We as the field serving as gatekeepers to our creative writing/arts domain must stand by this criterion, and expect no less of creative research than we do of ‘traditional’ (read: familiar) arts and humanities research. This methodology supports maintaining a stringent standard of critical knowledge developed through thorough research (which, in this case, also includes creative practice; it does not exclude close readings or discourse on theory, as noted previously), and provides us with a new, robust approach that will bring us closer to answering questions about practice and creative work that have previously proven difficult or impossible.

Notes

1 Available at http://scalar.usc.edu/works/creative-practice-research/

2 Smith and Dean Citation2009; Brophy Citation2009; Sullivan Citation2010; McNiff Citation2013; McNiff Citation1998; Gray and Malins Citation2004; Macleod and Holdridge Citation2006; Carter Citation2004.

3 Available at http://scalar.usc.edu/works/creative-practice-research/

4 It is noted that all research endeavors can be argued to be ‘creative’, and conversely all creative practice can be argued to incorporate research and knowledge development, however implicitly. For the purposes of clarity in this particular discussion, I am drawing an artificial distinction between creative practice and scholarly knowledge as is generally communicated through academic discourse, while acknowledging that in practice, the two can be rather blended. Insights and alternative approaches that can enhance this discussion are welcomed in the comments of the online version of this paper.

5 Both approaches center on creative practice as a primary method of knowledge development. The distinction lies in the role of the creative artefact. For practice-led projects, the artefact is not as important as the process of creating it. In practice-based projects, however, the final artefact is a key element. In my research, I was interested in how changing from a prose writing practice to a digital writing practice affected my process and the narratives I produced. The former is a practice-led element, while the latter is practice-based.

6 When I encountered significant difficulties composing a particular chapter of a prose novella that I intended to adapt to a digital fiction, I eventually found that creating the digital (multimodal, interactive) version before the prose version was more conducive to the story. I discuss this in Skains Citation2017.

7 In my case, my domain is the field of Creative Writing (both prose and digital); my field is largely comprised of creative writing researchers, creative writers, literature scholars, e-literature scholars, and narratologists; and I am an experienced prose writer (short stories, unpublished novels). Throughout the course of this research, I gained knowledge and established long-term memory in digital fiction and digital writing. I discuss how the acquisition of this knowledge to my long-term memory affected my creative practice in Skains Citation2017.

8 Mark Marino’s 2006 treatise on Critical Code Studies primarily focuses on post-textual analysis of a work’s source code; however, it is also relevant to approach source code from a practice-based perspective, examining how the practice of composing a creative work through the material medium of code (which the computer then translates into artefact) affects the composer and the work itself.

References

- Alber, Jan, and Rüdiger Heinze, eds. 2011. Unnatural Narratives - Unnatural Narratology. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Alber, Jan, Stefan Iversen, Henrik Skov Nielsen, and Brian Richardson. 2012. ‘What Is Unnatural about Unnatural Narratology?: A Response to Monika Fludernik.’ Narrative 20 (3): 371–82. doi:10.1353/nar.2012.0020.

- Alber, Jan, Stefan Iversen, Henrik Skov Nielson, and Brian Richardson. 2010. ‘Unnatural Narratives, Unnatural Narratology: Beyond Mimetic Models.’ Narrative 18 (2): 113–36. doi:10.1353/nar.0.0042.

- Bell, Alice, and Jan Alber. 2012. ‘Ontological Metalepsis and Unnatural Narratology.’ Journal of Narrative Theory 42 (2): 166–92. doi: 10.1353/jnt.2012.0005

- Bochner, Arthur P. 2000. ‘Criteria Against Ourselves.’ Qualitative Inquiry 6: 266–72. doi:10.1177/107780040000600209.

- Bouchardon, Serge, and Davin Heckman. 2012. ‘Digital Manipulability and Digital Literature.’ Electronic Book Review. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/heuristic.

- Brandt, D. 1992. ‘The Cognitive as the Social: An Ethnomethodological Approach to Writing Process Research.’ Written Communication 9 (3): 315–55. doi:10.1177/0741088392009003001.

- Brophy, Peter. 2009. Narrative-Based Practice. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Campbell, Andy. 2011. ‘Fiction of Dreams.’ Lecture, December 14.

- Candy, Linda. 2006. ‘Practice Based Research: A Guide.’ Sydney: Creativity & Cognition Studios.

- Carter, Paul. 2004. Material Thinking. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1996. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins.

- Edmonds, Ernest A, Alastair Weakley, Mark Fell, Roger Knott, and Sandra Pauletto. 2005. ‘The Studio as Laboratory: Combining Creative Practice and Digital Technology.’ International Journal of Human Computer Studies 63 (4–5): 452–81. http://research.it.uts.edu.au/creative/COSTART/pdfFiles/IJHCSSIpaper.pdf. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2005.04.012

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2011. ‘Autoethnography: An Overview.’ Forum Qualitative Social Research 12 (1). Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589/3095.

- Finke, Ronald A. 1996. ‘Imagery, Creativity, and Emergent Structure.’ Consciousness and Cognition 5 (3): 381–93. doi:10.1006/ccog.1996.0024.

- Flower, L., and J. R. Hayes. 1984. ‘Images, Plans, and Prose: The Representation of Meaning in Writing.’ Written Communication 1 (1): 120–60. doi:10.1177/0741088384001001006.

- Flower, Linda, and John R Hayes. 1981. ‘A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing.’ College Composition and Communication 32 (4): 365–87. doi: 10.2307/356600

- Fortune, Ron. 2005. ‘“You’re Not in Kansas Anymore”: Interactions among Semiotic Modes in Multimodal Texts.’ Computers and Composition 22 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.012.

- Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Gray, Carole, and Julian Malins. 2004. Visualizing Research: A Guide to the Research Process in Art and Design. Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. 2002. Writing Machines. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Herman, David. 2007. ‘Storytelling and the Sciences of Mind: Cognitive Narratology, Discursive Psychology, and Narratives in Face-to-Face Interaction.’ Narrative 15 (3): 306–34. doi:10.1353/nar.2007.0023.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. 2nd ed. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Lubart, Todd. 2009. ‘In Search of the Writer’s Creative Process.’ In The Psychology of Creative Writing, edited by Scott Barry Kaufman and James C. Kaufman, 149–65. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Macleod, Katy, and Lin Holdridge, eds. 2006. Thinking Through Art: Reflections on Art as Research. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Makri, S., and Ann Blandford. 2012a. ‘Coming Across Information Serendipitously : Part 1 – A Process Model [Open Access Version].’ Open access version. Journal of Documentation 68 (5): 684–705. doi:10.1108/00220411211256030.

- Makri, S., and Ann Blandford. 2012b. ‘Coming Across Information Serendipitously : Part 2 - A Classification Framework [Open Access Version].’ Journal of Documentation 68 (5): 706–24. doi:10.1108/00220411211256049.

- Marino, Mark C. 2006. ‘Critical Code Studies.’ Electronic Book Review. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/codology.

- McNiff, Shaun. 1998. Art-Based Research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, Ltd.

- McNiff, Shaun. 2013. Arts as Research: Opportunities and Challenges. Bristol: Intellect.

- Montfort, Nick. 2003. Twisty Little Passages. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Montfort, Nick. 2011. ‘Toward a Theory of Interactive Fiction.’ In IF Theory Reader, edited by K. Jackson-Mead and J.R. Wheeler, 25–58. Boston, MA: Transcript On Press.

- Niedderer, Kristina, and Seymour Roworth-Stokes. 2007. ‘The Role and Use of Creative Practice in Research and Its Contribution to Knowledge.’ In IASDR07: International Association of Societies of Design Research. Hong Kong. http://www.sd.polyu.edu.hk/iasdr/proceeding/papers/THE ROLE AND USE OF CREATIVE PRACTICE IN RESEARCH AND ITS CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE.pdf.

- Perry, Gaylene. 2008. ‘The Non-Verbal and the Verbal: Expanding Awareness of Practice-Led Research in Creative Writing.’ In The Creativity and Uncertainty Papers: The Refereed Proceedings of the 13th Conference of the Australian Association of Writing Programs. http://aawp.org.au/files/Perry_2008.pdf.

- Pillow, W.S. 2010. ‘Dangerous Reflexivity: Rigour, Responsibility and Reflexivity in Qualitative Research.’ In The Routledge Doctoral Student’s Companion, edited by Pat Thomson and Melanie Walker, 270–82. London: Routledge.

- Ranker, Jason. 2008. ‘Composing Across Multiple Media: A Case Study of Digital Video Production in a Fifth Grade Classroom.’ Written Communication 25 (2): 196–234. doi:10.1177/0741088307313021.

- Reason, Peter, and Hilary Bradbury. 2001. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. London: SAGE.

- Richardson, Brian. 2006. Unnatural Voices: Extreme Narration in Modern and Contemporary Fiction. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press.

- Richardson, Laurel, and Elizabeth Adams St. Pierre. 2008. ‘Writing: A Method of Inquiry.’ In Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 3rd ed., 473–500. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2006. Avatars of Story. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Skains, Lyle. 2016a. ‘Creative Commons and Appropriation: Implicit Collaboration in Digital Works.’ Publications 4 (1). http://doi.org/10.3390/publications4010007.

- Skains, Lyle. 2016b. ‘The Fragmented Digital Gaze: The Effects of Multimodal Composition on Narrative Perspective.’ Qualitative Inquiry, Special Issue: Hypermodal Inquiry 22 (3): 183–90. doi:10.1177/1077800415605054.

- Skains, Lyle. 2017. ‘The Adaptive Process of Multimodal Composition: How Developing Tacit Knowledge of Digital Tools Affects Creative Writing.’ Computers and Composition 43: 106–17. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2016.11.009.

- Smith, Hazel, and Roger T. Dean. 2009. Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Sondheim, Alan. 2006. ‘My Future Is Your Own Aim.’ Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 12 (4). UNIVERSITY OF LUTON: 375–81. http://sws.humanities.mcmaster.ca/~artistsnewmedialeague/docs/Sondheim_My_Future_is_Your_Own_Aim.pdf.

- Stewart, Robyn. 2006. ‘Mindful Practice: Research and Interdisciplinary Dialogues in the Creative Industries.’ In InSEA World Congress: Interdisciplinary Dialogues in Arts Education, 1-5 March 2006, 1–10. Viseu, Portugal: International Society for Education through Art. http://eprints.usq.edu.au/5356/1/Stewart_InSEA_2006_AV.pdf.

- Sullivan, Graeme. 2009. ‘Making Space: The Purpose and Place of Practice-Led Research.’ In Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts, edited by Hazel Smith and Roger T. Dean, 41–65. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Sullivan, Graeme. 2010. Art Practice as Research: Inquiry in Visual Arts. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Weight, Jenny. 2006. ‘I, Apparatus, You: A Technosocial Introduction to Creative Practice.’ Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 12 (4): 413–46. doi:10.1177/1354856506068367.