ABSTRACT

When and under what conditions do ideologically similar nationalist parties adopt different positions and discourses about refugees and immigrants? We address this question by examining nationalist parties’ approaches toward Syrian refugees in Turkey. Documenting these differences based on an original Twitter dataset and party manifestos, we argue that electoral dynamics under the new presidential system have shaped nationalist parties’ discourses about refugees in the country. In particular, we explore how pre-electoral alliances and a strategic opening in the political space have motivated nationalist parties to amplify, ambiguate, or silence their otherwise conservative and nativist refugee discourses. Additionally, we maintain that urbanization has influenced the discursive strategies of nationalist party elites toward immigrants and refugees, giving rise to contradictory forms of nationalism in urban areas, including both far-right and liberal nationalisms. Overall, this study offers valuable insights into the complex interactions between refugee politics, electoral dynamics, nationalism, and urbanization in Turkey.

Introduction

Turkey hosts 3.8 million refugees, who comprise about five percent of its population.Footnote1 It is now the top refugee-hosting country in the world.Footnote2 The vast majority of its refugee population, 3.6 million, are from Syria, and the remainder are from several countries, including Afghanistan, Somalia, and Eritrea. The country has also become a safe haven for migrants from Russia, Ukraine, Iran, Iraq, and the wider Middle East. Migration policies have become a top priority for the disgruntled masses amidst the recent economic downturn.Footnote3 There is now a pool of voters who are disappointed by the government’s refugee policies and are thus very receptive to mobilization around these issues. Public opinion data demonstrate that 86 percent of Turkish citizens want refugees and immigrants to be sent back home.Footnote4 This is an opinion shared not only by the supporters of the opposition parties but also by the supporters of President Recep T. Erdoğan, who for years mostly pursued an open-door policy toward refugees and immigrants.

These massive waves of migration occurred during a period of rapid urbanization in Turkey. When the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, AKP) came to power in 2002, roughly 35 percent of the Turkish population lived in rural areas. However, by 2018, the rural population fell to 16 percent. Today, more than half of the population lives in big cities such as Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, and Bursa.Footnote5 Such urbanization, along with the massive inflow of refugees in the last decade, has transformed nationalist tendencies. Reflecting this complex relationship between urbanization and nationalism, nationalist voters in Turkish cities have developed both liberal and far-right nationalist sentiments.

Currently, Turkey is home to three prominent nationalist parties: the Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP), the Good Party (İyi Parti), and the Victory Party (Zafer Partisi). These three parties collectively represent nearly 25 percent of the vote and hold considerable electoral significance. However, these otherwise ideologically similar parties have taken different positions regarding the sources of and solutions to the Syrian refugee issues, reflecting the variations within Turkey’s nationalist political landscape.

As part of the People’s Alliance (Cumhur İttifakı), the MHP largely aligns its position with that of the ruling AKP, and it does not advocate for an immediate and forced return of refugees. Instead, it emphasizes that the return of Syrians to their country should be voluntary and only considered after peace is restored in Syria. On the other hand, the Good Party promises to facilitate the return of refugees to Syria through negotiations with political actors, primarily Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, in accordance with international refugee laws. At the far-right end of the spectrum, the Victory Party’s political campaign centers around the forced return of refugees to Syria. It not only holds the government responsible but also blames refugees for various societal, political, and economic issues.

Emphasizing the growing support for nationalist-oriented parties, the existing political party literature offers valuable insights into the electoral pressures on migration policies.Footnote6 Electoral dynamics such as issue salience, party competition, and pre-electoral coalition formation impact parties’ stances on migration in a multiparty system.Footnote7 Existing studies that investigate the impact of these factors on parties’ stances primarily focus on liberal democracies within the Western context.Footnote8

However, electoral dynamics also play a significant role in shaping parties’ stances on migration in non-Western contexts. Studying these non-Western contexts is particularly important for refugee studies because approximately eighty-three percent of refugees are hosted in low- and middle-income countries.Footnote9 By centering these contexts we can achieve a more inclusive and accurate analysis of global refugee politics. Against this background, this article first explains the differences in nationalist parties’ positions on refugees and immigrants in Turkey based on Twitter data. Subsequently, it accounts for them by exploring the impact of a set of electoral dynamics (pre-electoral coalition formation and strategic openings in the political space) and the transformation of the nationalist ideology.

This article makes four significant contributions. Firstly, it illustrates the complexities surrounding Syrian refugee politics in Turkey. Secondly, the study improves our understanding of party politics in the country by explaining how electoral dynamics influence party positions and discourses about refugees. Thirdly, the article offers a distinct narrative on the transformation of nationalism, the most dominant political ideology in modern Turkish history. Lastly, it contributes to the measurement and analysis of party positions on refugees by introducing a unique approach that defines these positions based on dynamic and interactive Twitter data.

Electoral dynamics, nationalism, and attitudes toward refugees

In this study, we define two factors that constitute electoral dynamics: pre-electoral coalitions (also known as alliances or pacts) and strategic openings in the political space. Pre-electoral coalitions or alliances are formal partnerships formed between two or more political parties before a presidential election. These alliances are typically aimed at achieving a common goal, such as increasing the chances of winning the presidential election or obtaining a majority of seats in the legislative body that works alongside the presidency.

Multiparty pre-electoral coalitions in presidential systems differ from pre-electoral and post-electoral coalitions in parliamentary systems. Unlike some parliamentary pre-electoral coalitions where parties present separate electoral lists and announce plans to govern together if given the opportunity, presidential pre-electoral coalitions always involve a nomination agreement.Footnote10 Additionally, coalition partners typically have a lesser role in influencing policy decisions and sharing political power through negotiations and compromises in multiparty presidential coalitions than in multiparty parliamentary coalitions, as the immediate risk or cost of not fulfilling the promises made to alliance partners during the pre-electoral period is minimal. The existing literature has primarily focused on the impact of pre-electoral coalitions in presidential systems on various political outcomes such as the distribution of political power, cabinet stability, and polarization.Footnote11 However, this study particularly examines how presidential pre-electoral coalitions shape party positions and discourses about refugees.

The other electoral dynamic we explore is strategic openings in the political space. This concept refers to the opportunities that arise in a political environment following critical changes. In this study, we consider the inability of primary competitors to align their positions on a key electoral issue with the expectations of the public as a form of strategic opening in the political space. This might result in voters being more open to switching their vote in favor of an entirely new alternative, including niche parties, if they are disappointed with the existing approaches and policies on that particular issue.Footnote12 For political parties, a strategic opening provides a chance to gain a comparative advantage over their opponents by emphasizing the differences between their preferred policies and those of their rivals.

In this context, we argue that the emergence of the Victory Party in Turkey can be explained by a strategic opening in the political space, where none of the existing political parties’ and alliances’ stances on refugees and immigrants aligned with that of the public. We also find support for this fragmentation within the nationalist party landscape from the strategic entry theory. This theory posits that new parties are more likely to appear when the institutional costs of launching a party are low, and the presidency holds significant power with direct elections, thereby offering additional benefits from holding political offices, especially when electoral viability is high.Footnote13

Shifting the focus to the nationalism-migration politics nexus, two types of nationalism have gained prominence in the contemporary world: civic and ethnic nationalism. The former is characterized as liberal and inclusive, whereas the latter is seen as exclusionary, illiberal, and prone to violence, authoritarianism, and social hierarchy.Footnote14 Many studies have found a strong association between ethnic nationalism and anti-immigrant and refugee attitudes.Footnote15 In contrast, liberal nationalists tend to endorse a form of democracy that emphasizes both inclusive citizenship and collective nationalist sentiments as crucial components for fostering trust, transparency, and the common good in society.Footnote16

Situated within this literature, our study explores the complex relationship between urbanization and nationalism in Turkey. We maintain that urbanization leads to the rise of contradictory forms of nationalism in cities: civic-liberal and far-right-nativist, thereby affecting the strategies of nationalist parties’ elites. On the one hand, it increases identification with liberal and secular values due to better access to education, higher economic prospects, and exposure to diversity.Footnote17 On the other hand, it fuels nativist and nationalist attitudes toward immigrants and refugees due to increased economic competition, cultural differentiation, and political polarization. In light of the theoretical framework discussed above, the next section introduces the Turkish case and presents the central arguments of the study.

The Turkish case: evolution of nationalism, new government system, and Syrian refugees

After the establishment of the Republic in 1923, Turkishness emerged as the official state ideology, serving as the foundation of state and nation-building efforts. The imagined Turkish community during this period was described as Muslim yet secular, Turkish yet with a Western orientation.Footnote18 While non-Muslim communities (Greeks, Jews, and Armenians) were legally recognized as religious minorities in accordance with the Treaty of Lausanne, non-Turkish Muslim groups like the Kurds were not granted recognition as a minority possessing their own language, traditions, and culture by the newly-formed Turkish state.

By the 1930s, the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP), led by Mustafa Kemal, solidified the foundation of the Turkish state by institutionalizing six core principles, known as the Six Arrows: Republicanism, Populism, Etatism, Nationalism, Laicite, and Revolutionism. During the early years of the republic, the state and nation were viewed as inseparable, organic, and singular. Etatist nationalism was accompanied by ethnic nationalism after the transition to a multiparty system in the second half of the twentieth century. Many nationalist parties emerged in the following decades. Among these, the MHP, the AKP’s current alliance partner, has been the most resilient and long-lasting.

We contend that the massive refugee and migrant flows in the face of rapid urbanization have contributed to the emergence of two new forms of nationalism in Turkey, which are distinct from the traditional, conservative nationalism of the MHP. The first form is secular and liberal nationalism, embodied by the Good Party, which primarily garners support from the coastal cities with higher socio-economic indicators. The two-decades of conservative rule of the AKP has also emboldened this secular nationalist opposition. The second form is populist, far-right nationalism embodied by the Victory Party, founded in 2021 amid an economic downturn that significantly impacted metropolitan areas and large cities densely populated by Syrian refugees. However, during these years the MHP’s nationalism became less secular and less urban, increasingly aligning with the AKP’s conservative nationalist values.

The rise of the nationalist movement party (MHP) in Turkish politics

The MHP is a right-wing nationalist party that puts a strong emphasis on the security and survival of the state, often highlighting domestic and external threats with a sense of alarmism.Footnote19 The origins of the MHP can be traced back to the Cold War era when communism and left-wing activism were portrayed as the primary threats to the Turkish nation and state. Colonel Alparslan Türkeş, who had been involved in the 1960 military coup, assumed leadership of the Republican Villagers Nation Party in 1965 and subsequently transformed it into the MHP in 1969. Under his leadership, the party’s main ideological framework, the ‘Nine Lights Doctrine’, was laid out. This doctrine envisioned a purely nationalist and nativist government, rejecting foreign ideologies such as capitalism, communism, and liberalism.Footnote20 In a way, the ‘Nine Lights’ represented a reaction to the Six Arrows of the CHP, the founding political party of the Turkish Republic.

Undisputed loyalty to the party and the state has been the main pillar of boundary-making within MHP cadres. While communism was the main threat during the 1970s, the pro-Kurdish insurgency and political movement became the main threat for MHP cadres in the 1990s.Footnote21 Muslimhood and Turkishness are considered indivisible aspects of national identity by the party.Footnote22 Türkeş went on to formulate this approach by highlighting that ‘we are as Turkish as Mount Tengri/Tian Shan, and as Muslim as Mount Hira,’ (Tanrı Dağı kadar Türk, Hira Dağı kadar Müslümanız).Footnote23

The MHP’s electoral success reached its peak under the leadership of Devlet Bahçeli, securing around 18 percent of the vote in the 1999 elections. Following these elections, the MHP formed a coalition with the center-left party led by Bülent Ecevit. However, in the 2000s, the party became increasingly concerned about the rise of the Islamic-oriented AKP, led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In its early years, the AKP attempted to blend Islamist ideology with pro-European Union (EU) and liberal rhetoric, which posed a challenge for the MHP. The AKP also initiated moderation and peace talks with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a move that did align with the MHP’s national threat perceptions, resulting in a rift between the two parties.

However, the dynamics of the MHP-AKP relationship completely changed after 2015 when President Erdoğan escalated the conflict with the PKK and after the 2016 coup attempt, during which the Turkish military faced considerable distress. It was at this juncture that Bahçeli opted to support Erdoğan, laying the groundwork for the formation of the People’s Alliance between the AKP and MHP in February 2018. The AKP’s more assertive and nationalist stance in response to perceived threats to national security in the subsequent years further solidified the MHP’s conservative nationalism. However, the party’s share of the vote did not experience a significant improvement after entering into an alliance with the AKP, as it secured only 11.1 and 10.08 percent of the vote in the 2018 and 2023 elections, respectively.Footnote24

The good party

The Good Party was established on October 25, 2017, under the leadership of Meral Akşener, alongside other prominent former MHP members such as Ümit Özdağ and Koray Aydın. The impetus for the Good Party’s establishment was dissent against Bahçeli’s leadership, which arose during the 2017 referendum on 18 constitutional amendments, the most significant of which aimed to transform the country’s parliamentary system into a presidential one. While Bahçeli supported Erdoğan, Akşener opposed the proposed change. Initially she challenged Bahçeli for leadership of the MHP. When this was unsuccessful, she opted to create a new political party. The MHP’s alignment with the AKP thus came at the cost of intra-party cohesion, leading several party elites to perceive greater political opportunities outside the MHP and subsequently splinter to form new political parties.

The Good Party positions itself as a centrist party and promotes a more liberal and secular conception of nationalism.Footnote25 The party’s strategic focus is on effective governance and broad-based appeal to diverse segments of the population. In this way, it distinguishes itself from the conservative nationalist stance of the MHP.

We argue that one of the key factors contributing to the Good Party’s rapid consolidation of a substantial support base in Turkish politics is the urban-rural cleavage. Since the 1990s, Turkey has witnessed significant urbanization, marked by the growing embrace of a more liberal and secular form of Turkish nationalism, particularly among the more educated and younger populations. Currently, only seven percent of people in Turkey reside in rural areas, whereas 40 percent live in mid-size cities. A majority, 53 percent, inhabits large metropolitan areas.Footnote26 While the social and cultural origins of Turkish nationalism are mostly reflective of the rural and conservative values of Anatolia, increasing urbanization since the 1990s has created divergences in the nationalist imaginations of the society.

MHP voters have gradually clustered in western and central Anatolia among the less-educated and less-secular population groups, whereas more highly-educated younger generations in the urban centers of large western cities have gradually espoused more secular and liberal conceptions of nationalism.Footnote27 On the one hand, this has been an outcome of reconciling urban and liberal lifestyles with secular and nationalist values. On the other hand, it has been a reaction to the AKP’s increasing Islamist rhetoric and ambivalent approach toward Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s legacy as the founder of the secular republic, which has marginalized large secular nationalist groups who view the Good Party as a platform to voice their grievances and uphold more secular principles.

Although the party was founded only in 2017, it garnered nearly the same vote share as the MHP, the country’s oldest nationalist party in the 2018 and 2023 parliamentary elections, securing 9.96 and 9.69 percent of the vote, respectively.Footnote28 Showing its departure from the MHP’s voter base, the Good Party received the highest percentage of its vote from the more urban, liberal, and industrialized Aegean region as opposed to conservative central Anatolia.Footnote29 In alignment with its objective of evolving into a catch-all party, the party’s support base is also omposed of a heterogeneous group of individuals. Survey data reveals that among Good Party voters, 40 percent had voted for nationalist parties, 32 percent for leftist parties, 20 percent for center-right parties, and 10 percent for religious-conservative parties in the 1990s.Footnote30 Therefore, its rapid rise and success not only position it as a promising contender against the MHP but also as an increasingly alternative mass party that fuzes two dominant ideologies of Turkish politics: nationalism and secularism. In 2018, the Nation’s Alliance (Millet İttifakı) played a crucial role for the Good Party, helping it exceed the 10 percent electoral threshold and secure seats in parliament. With the threshold lowered to 7 percent in 2022, not surpassing the threshold but amplifying the opposition against President Erdoğan by nominating a joint presidential candidate became the primary incentive for the Good Party to join the Nation’s Alliance.

The victory party

Defectors from the MHP founded the center-right Good Party. However, within the Good Party, a faction led by Ümit Özdağ moved toward the opposite end of the political spectrum and established Turkey’s first European-style populist radical-right party, the Victory Party, deepening the fragmentation within the nationalist party landscape.Footnote31 The Victory Party’s entire political campaign revolves around a single issue: the forced return of refugees to Syria. Similar to the Good Party, the Victory Party also upholds a secular conception of Turkish nationalism and shows loyalty to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. However, it diverges from the Good Party with its unapologetic racism toward Syrian and Arab refugees.

Ümit Özdağ, the leader of the Victory Party, employs the term ‘istila’ (invasion) to describe the forced migration of Syrians, aiming to mobilize voters who are dissatisfied with the government’s refugee policies. He portrays refugees as a threat to Turkish culture, language, customs, and traditions, exploiting identity politics to build a support base for his party. Urban anxieties played a unique role in the formation of his support base. The Victory Party was founded in 2021 during a significant economic downturn when the working urban poor were distressed by the devaluation of the Turkish lira, higher inflation rates, and weakened purchasing power. Economic distress created a social and political environment conducive to the rise of far-right tendencies in highly multiethnic and multicultural urban areas.

Syrian refugees are largely perceived as an economic threat by city dwellers as they face increasing pressure to compete for a limited number of jobs and accept lower wages. This competition for employment is particularly evident in certain urban enclaves, where internal Kurdish migrants also vie for similar job opportunities, leading to communal tensions.Footnote32 These emerging urban anxieties have impacted the electoral calculus of nationalist parties’ strategists and elites. The Victory Party, in particular, has capitalized on the escalation of anti-migration sentiments among the secular lower middle classes and urban working poor who are more severely impacted by the heightened competition in the labor market.

The party gained significant prominence and bargaining power during the 2023 Presidential elections when two dominant electoral alliances, Nation’s Alliance and People’s Alliance, veered toward the far-right to secure the support of Sinan Oğan, the ultra-nationalist candidate of the Ancestral Alliance (Ata İttifakı), which the Victory Party had joined. During the second round of the 2023 Presidential elections, the opposition candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu promised three ministries, including the Interior Ministry, and the leadership of the National Intelligence Organization (MİT), to the Victory Party in exchange for its support.Footnote33

The party received most of its votes from the cities hosting the largest number of Syrian refugees in Turkey, including Istanbul, Ankara, Bursa, Gaziantep, Izmir, Kocaeli, and Konya.Footnote34 Although the party secured a relatively low vote share of 2.3 percent in the elections, the intensity of competition between the main blocs and the need for the support of the Ancestral Alliance’s presidential candidate helped distinguish the party from others with similar vote shares. As refugee issues continue to shape public opinion and discourse, the Victory Party is likely to enhance both its vote share and bargaining power in future elections.

The arguments presented in this study regarding nationalist party positions on Syrian refugees in Turkey can be summarized as follows. First, we highlight that the MHP’s alliance with the AKP within the People’s Alliance has motivated it to strategically silence its earlier criticism of the AKP’s refugee policies. Before the alliance, MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli’s rhetoric regarding refugees was more critical and antagonistic toward the AKP. However, the alliance has influenced the MHP’s approach, causing its leaders to tone down their criticism. Nevertheless, we also acknowledge that there is a certain threshold to ideological accommodation, and if such an accommodation requires compromising too much on the party’s core ideology, it may not be tolerated. For instance, the MHP’s resistance to a negotiated settlement to the Kurdish issue, the Democratic Opening Process (Çözüm Süreci) in 2009, illustrated that such a policy was well beyond the boundaries of tolerable accommodation for the MHP.Footnote35

Secondly, we contend that the Good Party’s alliance with the CHP within the Nation’s Alliance has provided it with an electoral incentive to adopt an ambivalent approach on refugees and minimize conflicts within the alliance. On the one hand, the Good Party did not advocate for an immediate and forced return of refugees, emphasizing that Syrians’ return to their country should be voluntary and only after peace is restored. On the other hand, it emphasized that the prolonged presence of refugees was a symptom of the AKP’s failure and promised to facilitate their return to Syria through negotiations with various political actors including Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Notably, there was a discernible difference between the party’s discourse on refugees and immigrants within the alliance and beyond it.

Finally, we posit that the lack of sufficient differentiation between the two alliances’ refugee policies, despite the growing electoral salience of refugee issues, created a strategic opening/niche in the political space. This opening enabled the formation of a single-issue populist radical-right party (PRRP), the Victory Party, which bases its entire campaign on the involuntary repatriation of Syrian refugees. PRRP refers to a family of parties sharing a core ideology that includes a combination of nativism, authoritarianism, and populism.Footnote36 By fuzing nativism and populism, the Victory Party has become the first European-style PRRP in Turkey. While members of both dominant alliances support the return of refugees to Syria to varying degrees, they expect it to be voluntary, safe, and compliant with domestic and international laws, at least in principle.Footnote37 The Victory Party’s position on refugees aligns more closely with recent nativist trends in public opinion, favoring an immediate and forced return of refugees to Syria.Footnote38

The distinction between the voluntary and involuntary return of refugees is crucial. Voluntary return occurs when refugees decide to return based on their own assessment of the security conditions in their home country. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) considers voluntary return a durable solution to refugee situations. In contrast, involuntary return, also known as forced return or repatriation, happens when refugees are sent back to their home country against their own will, often under pressure or coercion. Involuntary return is a matter of concern as it may expose refugees to risks, including persecution, violence, or human rights abuses. Therefore, it is important to understand that political parties promoting the voluntary return of refugees in compliance with international humanitarian laws hold a significantly different policy position than political parties demanding the involuntary and immediate return of them without considering the conditions in their home countries.

The new governmental system

Political parties, as rational actors seeking to maximize their votes and seat shares, operate within a framework of ideological and institutional conditions and constraints. When political structures change, so do the opportunities, constraints, and strategies of party elites. Similarly, after the transition to the executive presidency, the electoral infrastructure of the Turkish political system underwent significant changes. The country adopted a variety of electoral systems for different types of elections. For parliamentary elections, Turkey uses a 7 percent nationwide threshold and employs the D’Hondt method, a party-list proportional representation system, to elect 600 members to parliament. In presidential elections, a two-round system is in place, in which the top two candidates (assuming no one has a majority of the vote) compete in a run-off election after the initial election. Lastly, local elections are conducted using a first-past-the-post system, where the winning candidate must obtain a plurality of the vote.

Reflecting Duverger’s law, the introduction of a two-round majority vote encouraged the emergence of a two-party or two-alliance system in the country. Consequently, two major electoral alliances, The People’s Alliance and The Nation’s Alliance, emerged following the transition to the new system of executive presidency.Footnote39 However, the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi, HDP), as the most important outside actor, faces a type of cordon sanitaire, a systemic exclusion by other alliances. While it may be too optimistic to argue that these electoral coalitions are formed purely out of ideological conviction, they currently function as the superstructures of the Turkish political system, shaping the dynamics of political competition.

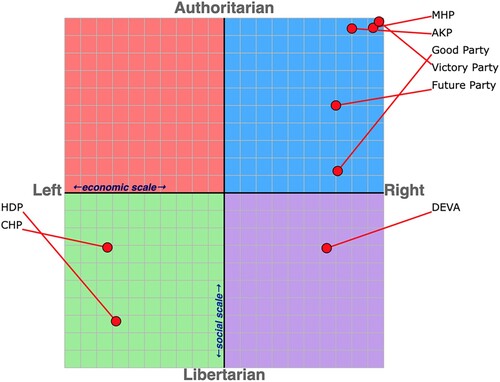

The transition from a parliamentary system to a presidential one after the April 2017 referendum also intensified intra-party conflicts and triggered the emergence of a high number of splinter parties. While only 31 political parties participated in the 2015 elections prior to the 2017 referendum, Turkey is currently home to 132 political parties.Footnote40 The number of new parties is often very high at the start of a transition to a presidential system. However, it is likely to decrease after subsequent elections once the electoral performance of the new parties becomes more predictable and the electoral arena stabilizes. Over time, most of these splinter parties may merge, dissolve, or lose significance in the political landscape. below illustrates the 2023 pre-electoral alliances and political parties in Turkey and places the major parties on the Turkish political spectrum.

Figure 1. Positions of Major Political Parties in Turkey.Footnote63

Table 1. Pre-electoral Alliances and Political Parties in Turkey.

Examining the relationship between party competition dynamics and fragmentation within the nationalist party landscape, the emergence of electoral alliances under the presidential system has had significant effects on nationalist parties. First, it enabled the Good Party, as a member of the Nation’s Alliance, to surpass the 10 percent electoral threshold and secure seats in parliament in 2018. Second, it granted the Victory Party, a non-member of the two dominant electoral blocs, substantial bargaining power due to the intense competition between these blocs and the electoral salience of refugee issues.

Additionally, the dynamics of power-sharing and governability in multiparty presidential coalitions may differ significantly from multiparty parliamentary coalitions. Coalition partners typically have a stronger role in influencing policy decisions and sharing political power through negotiations and compromises. However, in multiparty presidential systems, the concentration of power in the hands of the president complicates the fulfillment of promises made to alliance partners during the pre-electoral period. Presidential candidates may promise their alliance partners that they will distribute the political posts and be eager to compromise if they come to power. Yet, research on multiparty presidential systems indicates that the promises made to partners under presidential pre-electoral coalitions often go undelivered due to the winner-take-all-system and governability problems.Footnote41

The pre-electoral agreements and promises made by the CHP’s Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the candidate of the opposition Nation’s Alliance during the 2023 Presidential elections, provide a good example of the complexities and challenges of power-sharing in multiparty presidential systems. In an effort to maximize electoral support and build a broad coalition, Kılıçdaroğlu signed an agreement with five parties that supported his candidacy. This agreement included promises to appoint leaders of the supporting parties as vice presidents if Kılıçdaroğlu assumed power. However, Ümit Özdağ’s claim of a secret agreement between his party and Kılıçdaroğlu during the second round of the elections, where his party was promised three ministries and control of the National Intelligence Agency in exchange for their support, generated skepticism and suspicion among his coalition partners and may weaken the cohesion of this coalition in the future elections. Furthermore, the negative reactions of the five parties to the secret agreement already indicated that these promises would be highly unlikely to be fulfilled even if Kılıçdaroğlu assumed power.Footnote42

Data and methodology

A growing body of research has utilized Twitter (rebranded X in July 2023) data to study various phenomena including political mobilization, polarization, conflict dynamics, sectarianism, and ideology.Footnote43 However, there is a lack of research employing Twitter data to document party positions and discourses on refugees, particularly in the context of Turkey and the Middle East. In today’s world, nearly every political leader maintains a Twitter account and utilizes the platform to disseminate up-to-date political information to supporters and the broader public. As a result, Twitter has become the primary mode of communication for many party leaders, making it also an effective source to locate and document their opinions and positions on various issues, including migration.

Studies on party positions have traditionally relied on party manifestos as their main source of information.Footnote44 Manifestos offer several advantages, including being universal (as most parties produce manifestos), readily available through parties’ websites, and providing firsthand information about parties’ positioning in the political landscape.Footnote45 However, there are also limitations to using manifestos, such as not covering all major issues, being potentially outdated, and lacking dialectical or dynamic content.

In contrast, Twitter data offers distinct advantages, especially the ability to develop real-time measures of the relative salience of political discourses. This enables a more comprehensive understanding of party positions. For these reasons, we primarily employ Twitter data and supplement it with available party manifestos. By leveraging Twitter data, we can capture the evolving nature of party discourses on Syrian refugees and relate them to the broader political landscape in Turkey and the Middle East. This approach provides valuable insights into how political communication and party positions respond to changing events and issues in the digital age.

Although tweets are limited to 280 characters, they aid politicians in communicating a wide range of opinions, emotions, and beliefs in real-time. Social media platforms like Twitter also play a significant role in democratizing media representation, especially in authoritarian contexts where traditional media is controlled by the ruling party and the opposition is systematically excluded from the media’s power, authority, and visibility in shaping the public imagination. However, the spread of social media has also given rise to digital authoritarianism, where authoritarian regimes extend their control and influence into the digital realm. They use surveillance, repression, and manipulation of information to shape public discourse.

Turkey’s experience with Twitter reflects both the potential of the platform for political engagement and the challenges it poses to the government. Twitter has been banned multiple times in Turkey, especially during times of political upheaval, to control the flow of information and dissent.Footnote46 Despite these challenges, Turkey has a significant Twitter user base, ranking 7th in the world with 18.6 million active Twitter accounts.Footnote47 This highlights the platform’s importance in shaping political discourse and public opinion in the country, even amidst government attempts to control it.

In this study, we have chosen to focus on the tweets of the leaders from three dominant nationalist parties: the Nationalist Movement Party, the Good Party, and the Victory Party. During the selection process, we systematically excluded the parties where nationalism is considered secondary to the dominant party ideology, such as secularism and Islamism as observed in the cases of the CHP, the AKP, and several other parties. Additionally, we did not include smaller nationalist parties like the Great Unity Party, as they a strong stance on Syrian refugees and were not formed as a result of the recent fragmentation within the nationalist party landscape. The three chosen parties place nationalism at the core of their party ideologies and have demonstrated high electoral significance during the 2023 Presidential elections.

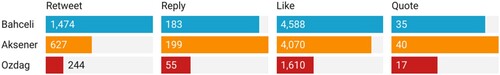

Furthermore, the leaders of these parties have a substantial Twitter following. Bahçeli (the MHP) and Akşener (the Good Party) each have around six million followers, while Özdağ (the Victory Party) has three million followers. For our study, we collected a total of 42,144 tweets from the Twitter accounts of these party leaders using the Twitter Streaming API (Application Program Interface). This API enabled us to access and analyze public Twitter data. In addition to tweets, we also gathered data on the number of retweets, likes, quotes, and replies, as well as the posting times and locations.

However, we need to offer some caveats about the use of Twitter data. We understand that some of the likes, quotes, or replies might belong to Twitter bots or automated Twitter accounts, as Twitter estimates the percentage of bot accounts to be around 5 percent.Footnote48 Nonetheless, as researchers, we do not have the means or resources to validate the authenticity of follower accounts. Additionally, we acknowledge that Twitter users are not a representative sample of the general population, and the views expressed on Twitter may not necessarily reflect the views of the broader public. Therefore, to mitigate potential biases and ensure the reliability of our findings, we collected data only from the official accounts of the party leaders.

The timeline of posts varies for each leader, as they began their tenure at different times. For Devlet Bahçeli, the data covers the period from March 2011 to November 2022, for Meral Akşener October 2017 to November 2022, and for Ümit Özdağ August 2021 to November 2022. The dataset includes 6,391 posts from Bahçeli, 10,217 posts from Meral Akşener, and 25,480 posts from Ümit Özdağ. Next, we filter the tweets related to refugees and nationalism using novel dictionaries we created. These dictionaries contain key phrases and words that feature prominently in the parties’ refugee and nationalism discourses in Turkey.Footnote49

After filtering the data, our analysis proceeds in the following manner. First, we assess the volume and frequency of tweets and different types of reactions they receive, such as retweets, likes, quotes, and replies. This examination of the volume and frequency of refugee-related tweets allows us to conceptualize the importance that each party places on refugee issues and whether they assert ownership over them. Second, we create word clouds based on the weight of keywords in party leaders’ tweets concerning refugees. These word clouds visually represent the most salient themes and topics in party leaders’ refugee discourses.

The quantitative content analysis in this study was automated using Python, thereby eliminating the risks and challenges associated with intercoder reliability. We conducted quantitative content analysis rather than critical discourse analysis or thematic analysis because content analysis permits systematic, replicable coding and quantification of textual data, making it suitable for research that aims to identify patterns, frequencies, or relationships in large datasets. Nevertheless, we supplement and expand our quantitative analysis of how dominant nationalist parties construct and communicate their positions on refugees in Turkey by grounding them in the broader political landscape that provides incentives and disincentives for politicians to frame refugee issues in particular ways.

For external validation and data triangulation, we employ party manifestos alongside party leaders’ Tweets. Although there is not a high volume of party manifestos, they also help identify and track changes in the positions of nationalist parties. The patterns observed in these manifestos largely align with the insights drawn from our Twitter dataset.

Results

Salience of refugee issues for nationalist political parties and levels of audience interactions on Twitter

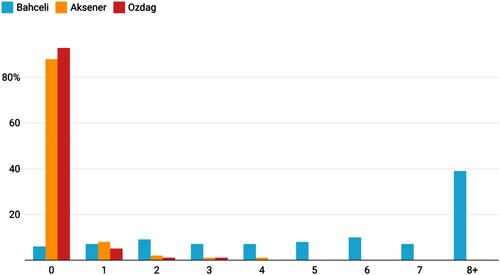

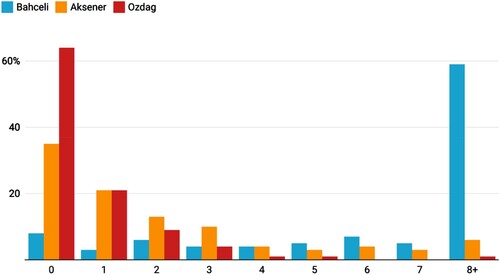

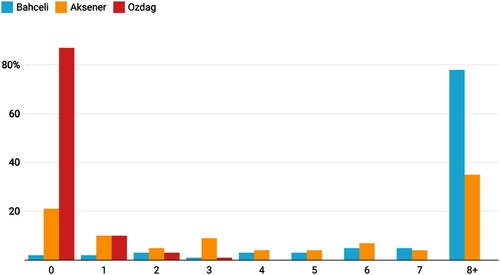

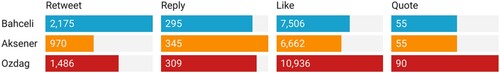

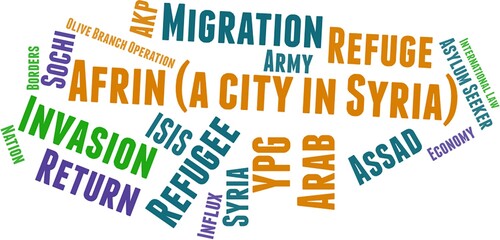

present the frequency of tweets by the party leaders, and show the levels of audience interactions with these tweets. In , the horizontal line represents the number of days elapsed between two consecutive tweets and the vertical line represents the ratio of total tweets posted within that time frame to all tweets in that category. For this analysis, we exclude threads from the sample as they are a series of connected tweets and cannot be considered independent.

As shown in , Akşener and Özdağ predominantly post tweets with a zero-day interval, indicating their higher activity and more frequent use of Twitter compared to Bahçeli, the leader of the MHP, whose tweet intervals are longer and more evenly distributed, ranging from zero to eight days. This suggests that the leaders of the two splinter parties (the Good Party and the Victory Party) maintain a larger social media presence and tweet more frequently than their primary counterpart, Devlet Bahçeli.

Similarly, illustrates that the time interval for the majority of nationalism-related tweets posted by Akşener and Özdağ is zero days, meaning they tweet about nationalism almost every day. In contrast, Bahçeli’s nationalism-related tweets have a longer interval of eight days, indicating that he tweets about nationalism almost once a week. This trend may be attributed to Akşener and Özdağ’s efforts to assert control over the nationalist ideology. As newly-formed nationalist parties, they pose a challenge to the MHP’s long-standing claim to the nationalist ideology, given that the MHP is the oldest nationalist party in the country.

Furthermore, presents the frequency of refugee-related tweets by these leaders. The data shows that the time interval for the majority of Özdağ’s refugee-related tweets is zero days, indicating that he tweets much more frequently than his counterparts about refugees. In contrast, for Akşener and Bahçeli, the frequency of refugee-related tweets is more evenly distributed, ranging from zero to eight days. This finding provides significant evidence for the centrality of Syrian refugee issues in the political campaigning of the Victory Party and its attempt to gain ownership over them.

In terms of reactions to the leaders’ tweets, illustrates the various types and levels of interactions. We employ four metrics to gauge the engagement with leaders’ tweets: likes, retweets, quote retweets, and replies. The findings reveal a mixed pattern concerning the interactions with the leaders’ tweets. While Bahçeli’s tweets generally receive a greater number of retweets and likes, they are not quoted and replied to as frequently as Akşener’s tweets. Quote retweets refer to tweets that are shared with a personal comment alongside the original tweet, whereas normal retweets are shared without any additional comments. Furthermore, replies refer to responses to another person’s tweet. In essence, likes and retweets may be considered passive indicators of engagement, while quote retweets and replies serve as active indicators. Considering this distinction, we conclude that Akşener’s tweets have received a higher level of engagement overall, as they have generated more active interactions in the form of quote retweets and replies.

Although we do not have demographic data on Twitter users, we suspect that the differences in the types of Twitter reactions may be closely linked with the voter profiles of these parties. The Good Party voters, unlike the MHP, tend to come from urban, educated, and high-income backgrounds, displaying higher levels of political engagement in general.Footnote50 However, we must exercise caution and note that a high level of engagement does not necessarily mean a high level of support because Twitter users engage with content for various reasons, including expressing agreement or disagreement, sharing information, or participating in discussions without showing endorsement. While the observed differences in Twitter reactions offer valuable insights into the online activity of party supporters, it is essential to combine this data with other forms of research and data sources to draw more comprehensive conclusions about party support and public opinion.

presents the levels of interaction with the nationalism-related tweets of these leaders, and the results are mixed. On the one hand, Özdağ’s nationalism tweets receive significantly higher likes and quote retweets compared to his counterparts. On the other hand, Bahçeli’s nationalism tweets are retweeted more frequently, while Akşener’s nationalism tweets receive more replies. The data shows that the party leaders’ promotion of the nationalist ideology find support among their Twitter followers albeit in different ways.

Finally, demonstrates the levels of interactions with the refugee-related tweets of these leaders. We observe a similar dichotomy in terms of the type of reactions to Bahçeli and Akşener’s refugee-related tweets, with higher numbers of likes and retweets compared to quote retweets and replies. However, reactions to Özdağ’s refugee-related tweets are significantly higher than his counterparts. This not only provides significant evidence for Özdağ’s considerable efforts to assert ownership over refugee issues but also highlights how deeply this resonates with a segment of the nationalist voters on Twitter. Özdağ has successfully established a connection with these nationalist voters and distinguished his party from other nationalist parties.

Discussion: party positions and political context

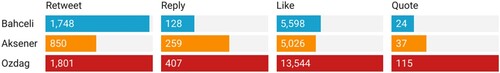

We generated word clouds based on the frequency of words in tweets related to refugees from leaders of three nationalist parties. The word clouds help characterize their positions regarding Syrian refugees and connect these with their positions on other issues. presents a word cloud of Bahçeli’s refugee-related tweets. His rhetoric predominantly centers around national security and military campaigns such as ‘Operation Olive Branch’ and ‘Operation Euphrates Shield,’ both Turkish military actions against the Syrian-Kurdish YPG (People’s Protection Unit) and ISIS in northern Syria. Bahçeli views the YPG as an extension of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) and its consolidation of power and mobilization of Kurdish population in northern Syria as a growing threat to the territorial integrity of Turkey. He believes that Kurdish autonomy in Syria could fuel Kurdish secessionism in Turkey.Footnote51

For these reasons, Bahçeli strongly criticized the AKP’s refugee and foreign policies during the early years of the Syrian Civil War. In its June 7, 2015 election statement, his party attributed theft, robbery, riot, the spread of epidemics, drug use, child marriage, illegal labor, and increased rent prices to refugees. Additionally, they presented the AKP’s involvement in the Syrian Civil War as part of the US’s Greater Middle East Initiative (GMEI),Footnote52 which they believed began with the disintegration of Iraq.Footnote53 According to Bahçeli, this process could culminate in a total breakdown of the Syrian regime and the rise of a wide range of non-state or proto-state actors such as ISIS and YPG in the region, thereby increasing Turkey’s vulnerability to ethnic insurgency and terrorist attacks.Footnote54

The same election statement also characterized the PKK-Turkish Peace Process, which began in 2013, as a threat to the unitary structure of the Turkish state. However, the tensions exacerbated by the Syrian Civil War and the involvement of both Turkey and the Kurds in the conflict brought the collapse of the peace process in July 2015. This event drew the MHP closer to the AKP and facilitated the formation of a pre-electoral alliance between the two parties before the June 2018 snap elections. Otherwise, negotiating a peace agreement with the PKK would have been a deal breaker for the MHP, given its core nationalist ideology.

After the formation of a pre-electoral coalition, Bahçeli’s criticisms of the AKP’s Syria and refugee policies have toned down and gradually been replaced by strategic silence. Unlike the 2015 election statement, the MHP’s 2018 election statement did not include any criticisms of the AKP’s Syria and refugee policies. Instead, it only urged for the better management of refugee affairs.Footnote55 Bahçeli’s tweets also reflect a similar change in the tone and content of his Syria and refugee rhetoric. In the following years, his tweets on refugees cautioned against the politicization of the issue by opposition parties. He emphasized the importance of avoiding tensions between local communities and refugees, rather than placing blame on the government for mishandling Syrian foreign policy and contributing to the refugee crisis.

Next, presents a word cloud of Akşener’s refugee-related tweets. Unlike Bahçeli, Akşener openly criticizes the government for its brotherhood narrativeFootnote56 and for its allocation of the country’s much-needed resources to Syrians. Nevertheless, similar to Bahçeli, Akşener also underscores the national security needs of the country, including operations in Afrin and Idlib, (bordering northern Syrian cities and Turkey’s safe zones) and the importance of containing YPG. Additionally, Akşener frequently proposes to negotiate a deal with President Bashar al-Assad to facilitate the safe return of refugees. This plan has also been incorporated into the party’s National Migration Doctrine, which was launched in September 2022.Footnote57

Contrary to Akşener, negotiating a refugee deal with the regime is considered a red line by the AKP and the MHP because these parties view President al-Assad as responsible for the forced displacement of Syrians. The AKP, therefore, focused its diplomatic efforts rather on the international supporters of the Assad regime, Moscow and Tehran, and participated in the Sochi and Astana Peace Talks. The Good Party’s manifestos propose specific plans to limit refugee and immigrant flows. These include stricter border protection measures, creating humanitarian buffer zones, devising international mechanisms to return immigrants and refugees to the countries of transit, and having more countries share the economic burden of resettling large refugee populations.Footnote58

provides a word cloud of Özdağ’s refugee-related tweets. In contrast to Bahçeli and Akşener, Özdağ’s rhetoric primarily revolves around the idea of forcibly returning refugees to Syria. He characterizes the influx of refugees as an invasion and scapegoats them for the chronic economic and political problems of the country. Additionally, Özdağ criticizes the government for its pursuit of Islamic foreign policy and the granting of citizenship to Syrians. These political campaigns are grounded in an exclusive conception of Turkish national identity that views admitting refugees from another country as an attack on the purity and wholesomeness of society. His rhetoric incites fears about the perceived other (i.e. the Syrian Arabs) and intensifies hostile prejudice toward refugees and immigrants.

In an attempt to carve out an autonomous political space for his party, Özdağ emphasizes that the Nation’s Alliance is not a viable alternative to the People’s Alliance when it comes to refugee policies, because they also promote lax and liberal policies. Özdağ denounces the CHP in particular for not upholding Atatürk’s principles and secular nationalism. The party’s founding manifesto draws analogies between the Turkish War of Independence (19 May 1919–1924 July 1923) and the Syrian refugee influx, depicting the latter as a socially engineered invasion of the country and an attack against its sovereignty.

Özdağ maintains that the refugee influx may exacerbate existing ethnic tensions and lead to political turmoil in the near future.Footnote59 Reminiscent of US President Donald Trump’s calls to build a wall along the US-Mexico border, Özdağ proposed ‘The Castle of Anatolia Project’ and pledged to launch a massive border surveillance system.Footnote60 The term ‘castle’ here symbolizes ownership and communicates the desire to institute a series of barriers, including physical walls, border patrols, and restrictive visa policies to prevent migrants and asylum seekers from entering the country’s borders.

In conclusion, these word clouds shed light on the complex and divergent positions of nationalist parties regarding Syrian refugees. Bahçeli’s rhetoric centers on national security concerns and military campaigns, with his criticisms of the AKP’s refugee policies waning after forming a pre-electoral alliance with it. Akşener presents the government’s Syria policies as a failure and seeks a negotiated settlement for the safe return of refugees. Meanwhile, Özdağ portrays refugees as scapegoats and advocates for their forced return. As Turkey navigates the challenges posed by the refugee crisis, these stances will continue to shape the refugee politics in the country.

Conclusion

Against the backdrop of massive refugee and migration flows, there has been a surge in global right-wing politics. Within this context, this study investigates the conditions and factors influencing the divergence and convergence of discourses and policies on refugees and immigrants among ideologically similar nationalist parties in Turkey.

The existing literature often emphasizes a nationalist right-wing convergence against refugees. However, our study demonstrates that these reactions are not always constant and homogenous and are more nuanced than assumed. We contend that new electoral dynamics and strategic openings might motivate nationalist parties to amplify, ambiguate, or silence their otherwise conservative and nativist refugee discourses.

In the past decade, Turkey has witnessed an unprecedented surge of migration, causing a demographic shock within its traditionally self-assured society and giving rise to new nationalist sentiments across the entire political spectrum. Currently, three prominent nationalist parties that belong to the same party family hold substantial electoral power in the country: The MHP, the Good Party, and the Victory Party. While the Good Party positions itself on the left side of the MHP, exhibiting more liberal tendencies, the Victory Party falls to its right, embracing a far-right nationalist discourse characterized by fierce opposition to both forced and voluntary migration. Intrigued by the variations in the refugee policies and discourses of these ideologically similar nationalist parties, this study examines the effects of pre-electoral coalitions, strategic openings in the political space, and the emergence of new forms of nationalism.

We maintain that the pre-electoral alliance between the AKP and the MHP has played a crucial role in incentivizing the MHP to reverse its earlier discourse and embrace strategic silence on Syrian refugee issues after 2015. Additionally, we argue that the Good Party’s ambivalent rhetoric toward refugees and immigrants is primarily driven by its desire to appear respectful of international humanitarian norms and to minimize the potential for intra-alliance conflicts. The party strategically prioritizes effective governance and aims to appeal to diverse segments of the Turkish population. It recognizes that advocating for the forced return of refugees may challenge its international legitimacy and sought-after broad appeal if it were to assume power in the future.

In the upcoming 2024 local elections, the Good Party has decided to field its own candidates instead of supporting joint candidates from the Nation’s Alliance. This strategic decision carries the potential to reshape the Good Party’s somewhat ambiguous stance on refugees. Notably, the party leader, Akşener, has recently adopted a nativist tone in her refugee rhetoric. She has blamed all Syrian refugees for fleeing their country and urged them to go to Gaza to fight against the Israelis.Footnote61 However, it is essential to underline that our dataset spans from March 2011 to November 2022, preventing us from comparing the Good Party’s stance on refugees before and after the 2023 presidential elections. Future research could explore how the refugee and immigration discourses of nationalist parties, along with their other policy positions, evolve when participating in alliances versus running independently, capturing the political communication and policy effects of these alliances in Turkey.

Furthermore, we maintain that the lack of sufficient differentiation in the refugee policies of the two dominant pre-electoral alliances has created favorable conditions for the emergence of a PRRP, the Victory Party in Turkey. This finding contributes to our understanding of the dynamics behind party splits and the formation of new political parties. The Victory Party’s ultra-nationalist voters view the Good Party as not radical enough, and they also believe that the MHP’s alliance with the Islamist AKP, which implemented relatively lax refugee policies, has further exacerbated immigration pressures. However, the Good Party continues to appeal to secular upper middle classesFootnote62 who desire more rational policy solutions to immigration and refugee issues as well as other issues faced by the country.

Finally, we examine the impact of two emerging forms of nationalism (far-right and liberal), as alternatives to the traditional rural-conservative nationalism, on the approaches of nationalist parties toward Syrian refugees. The intertwining of urbanization and nationalism has given rise to conflicting social and political tendencies. On the one hand, it has fostered a more secular and liberal nationalist voter base, driven by increased exposure to education and diversity. On the other hand, it has unsettled and agitated the urban working poor due to heightened competition in the labor market.

Notably, the persistent economic decline has exacerbated xenophobic sentiments among the urban poor in major cities. Recognizing this as a strategic opening in the political opportunity structure, Özdağ broke away from the Good Party and established the first European style PRRP in Turkey, aiming to attract reactionary refugee votes. The party gained significant traction, particularly during the second round of the 2023 Presidential elections, when they offered their support to the opposition candidate, Kılıçdaroğlu, in exchange for ministerial positions.

Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the complex interactions between refugee politics, electoral dynamics, the evolution of nationalism and the nationalist party landscape, and urbanization in Turkey. Utilizing an original Twitter dataset, it documents and explains the positions of three nationalist parties on Syrian refugees. Future studies could further build upon this research by exploring additional topics such as the intersection of Islamophobia and anti-Arab sentiments within secular Turkish nationalism, the impact of new immigrant and refugee flows on historically competing Turkish and Kurdish nationalist visions, and the instrumentalization of the open-door policy to advance geopolitical interests and foreign policies.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the W. K. Kellogg Foundation and Mershon Center for International Security Studies at Ohio State for research funding. We are also thankful to Teri Murphy, Zaynab Quadri, and Brooks Marmon for their comments on earlier versions of this article. Special thanks go to Burak Kakillioglu, Ayse Esra Arikan, Andrew Mackey, and Laeeq Khan for their research assistance. Additionally, we presented this paper at MPSA 2023 Conference in Chicago on the Parties and Policymaking in the Middle East panel. We are grateful to Salih Yasun, Dersu Ekim Tanca, and Huseyin Emre Ceyhun for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

We used an original Twitter dataset in this article. All data replication materials for this article are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YJOSFY

, Harvard Dataverse. We provided a link to this dataset in the article as well.Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sefa Secen

Sefa Secen is currently a postdoctoral scholar at the Mershon Center for International Security Studies at Ohio State and a research fellow on the Islamic Family Law Project at Syracuse University. He received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University in July 2022. He primarily studies party policies and public attitudes toward refugees with a focus on the social construction of threat and security perceptions.

Serhun Al

Serhun Al received his PhD in Political Science from the University of Utah in 2015. He is in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Izmir University of Economics, Turkey. He was a visiting scholar at Ohio State during the 2022–2023 academic year. His research interests include politics of identity, nationalism and ethnic conflict, and security studies within the context of modern Turkey and the Kurdish Middle East.

Bekir Arslan

Bekir Arslan earned his bachelor's degree from Trakya University and completed his Master of Computer Science at the University of Nevada, Reno. Currently, he works as a software engineer at Chase Bank in Columbus Ohio.

Notes

3 https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/syrian-refugees-in-turkey-changing-attitudes-and-fortunes

4 “The information was drawn from the “Dimensions of Polarization in Turkey 2020 Survey,” which was conducted by Istanbul Bilgi University in cooperation with the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

6 Barone et al., “The Role of Immigration”; Dinas, et al., “Waking up the Golden Dawn”; Hangartner et al., “Refugee Crisis”; Tabellini, “Gifts of the Immigrants”; and and Gessler and Hunger, “Radical Right Parties.”

7 Secen, “Explaining the Politics,” and Secen, “Electoral Competition Dynamics.”

8 Morales, Pardos-Prado, and Ros, “Issue Emergence,” and Vrânceanu, “The Impact”.

10 After a daunting period of uncertainty, the parties that joined the largest opposition coalition in Turkey, known as The Nation’s Alliance, also signed a nomination agreement. Detailed information can be found in the following article: https://www.euronews.com/2023/03/06/turkish-opposition-picks-presidential-candidate-to-run-against-erdogan

11 Chiru, “Early Marriages”; Debus, “Pre-Electoral Commitments”; and Albala, Borges, and Couto, “Pre-electoral Coalitions.”

12 Hug, Altering Party Systems.

13 Cox, Making Votes Count, and Tavits, “Party Systems.”

14 Miguel, “Tribe or Nation”; Tudor and Slater, “Nationalism, Authoritarianism, and Democracy”; and Bonikowski and Zhang, “Populism.”

15 Major, Blodorn, and Blascovich, “The Threat”; Abrajano and Hajnal, “White Backlash”; and Zárate et al., “Cultural Threat.”

16 Charney, “Identity and Liberal Nationalism.”

17 Luca et al., “Progressive Cities.”

18 Al, Patterns of Nationhood.

19 Başkan, “Globalization and Nationalism.”

21 Opçin, “The Nationalist Action Party,” and Cengiz, “Resistance to Change.”

22 Erken, “Politics of Nationalism.”

23 Mount Tengri, situated in the Tian Shan mountain range on the China, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan tripoint, east of Lake Issyk Kul, holds tremendous significance in Turkish mythology and legends. It is claimed that Turkish culture originated and spread from Mount Tengri. Similarly, Mount Hira (Jabal al-Nour), located about two miles from the Kaaba, is the site where Prophet Muhammad received the first revelations in 610 CE.

27 http://www.teamarastirma.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/%C4%B0Y%C4%B0_Parti_Se%C3%A7men_Analizi.pdf

30 http://www.teamarastirma.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/%C4%B0Y%C4%B0_Parti_Se%C3%A7men_Analizi.pdf

31 For more information on the party, see http://turkishpolicy.com/blog/104/zafer-partisi-refugees-and-the-upcoming-elections-in-turkey

32 Secen and Gürbüz, “Between hospitality and hostility,”and Secen, “Self-representation.”

35 Celep, “Turkey’s Radical Right.”

36 Mudde, “Populist Right Parties.”

37 The content and tone of CHP’s refugee discourse changed dramatically during the second round of the 2023 presidential elections when it formed an alliance with the far-right Victory Party to improve its electoral prospects. However, our analysis of the Twitter dataset and the alliance’s memorandum of understanding (available at https://en.chp.org.tr/haberler/memorandum-of-understanding-on-common-policies-january-30-2023) indicates that CHP’s position was nowhere close to the far-right stance before the elections.

38 “The information was drawn from the “Dimensions of Polarization in Turkey 2020 Survey,” which was conducted by Istanbul Bilgi University in cooperation with the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

39 The People’s Alliance consisted of four conservative parties: the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the New Welfare Party (YRP), and the Free Cause Party (HUDAPAR). In contrast, the Nation’s Alliance, also known as the Table for Six, formed a coalition of ideologically diverse opposition parties, including the country’s main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Good Party (a splinter from MHP), the Islamist Felicity Party (SP), Democrat Party (DP), and two AKP splinter parties, the Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA) and the Future Party (GP). The first elections in which these alliances participated were the June 2018 elections. During those elections, the People’s Alliance secured victory with 52 percent of the vote in the first round. In Turkey’s May 14, 2023 elections, the People’s Alliance once again secured victory, this time with 52 percent of the vote in the second round. A total of 36 parties competed, and more than half of them formally joined or pledged to join one of the two dominant alliances.

41 Kellam, “Pre-Electoral Coalitions”; Mainwaring and Shugart, “Presidentialism”; Samuels and Shugard “Presidents”; and Colomer and Negretto “Presidentialism and Parliamentarism.”

43 Lynch, The Arab Uprisings; Zeitzoff, “Using Social Media”; Conover et al., “Political Polarization”; and Siegel, “Twitter Wars.”

44 Budge and Farlie “Explaining and Predicting,” and Dancygier and Morgalit, “The Evolution”

45 Odmalm, “Coding and Using Party Manifestos.”

49 All data replication materials for this article are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YJOSFY on Harvard Dataverse.

50 http://www.teamarastirma.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/%C4%B0Y%C4%B0_Parti_Se%C3%A7men_Analizi.pdf

51 Cagaptay and Yalkin, “Syrian refugees.”

52 For more information on GMEI, see https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-new-u-s-proposal-for-a-greater-middle-east-initiative-an-evaluation/

56 It is important to note that all political parties referenced diverse historical contexts, events, memories, and images to justify their preferred policies and strategies toward Syrian refugees. The ruling party (AKP), in alignment with its Islamist ideology, utilized religious analogies by likening the Syrian refugees to the Muhajirun (early Muslims who migrated from Mecca to Medina due to oppression) and positioning themselves as the Ansar (early Muslims from Medina who helped the Muhajirun).

60 ibid.

62 Refer to Konda’s analysis of the ballot boxes for the General Parliamentary and Presidential Elections on May 14 and 28, 2023.

63 We have constructed this political spectrum figure using data the 2019 Chapel Hill expert survey, which encompasses political parties in 32 countries, including all European Union member states as well as Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, and Turkey. The survey details are available at https://www.chesdata.eu/ches-europe. As the survey only five Turkish political parties (AKP, CHP, MHP, the Good Party, and HDP), we needed to estimate the newly established parties’ positions (DEVA, Future Party, and Victory Party) based on the positions of comparable parties in other European countries. For instance, we assigned DEVA, identified as a liberal-conservative party, the positioning of Germany’s Free Democrats (FDP). Similarly, the positioning of European far-right parties such as AfD and Le Pen guided us in determining the position of the Victory Party. Additionally, we considered the positioning of modestly conservative parties like the Christian Social Union (CSU) when estimating the position of the Future Party. We acknowledge that this methodology may not be perfect, but it represented the most viable approach to create a political spectrum with the available data on Turkish party positions.

References

- Abrajano, Marisa, and Zoltan L. Hajnal. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Al, Serhun. Patterns of Nationhood and Saving the State in Turkey: Ottomanism, Nationalism and Multiculturalism. New York: Routledge, 2019.

- Albala, Adrián, André Borges, and Lucas Couto. “Pre-electoral Coalitions and Cabinet Stability in Presidential Systems.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 25, no. 1 (2021): 64–82.

- Barberá, Pablo. “Birds of the Same Feather Tweet Together: Bayesian Ideal Point Estimation Using Twitter Data.” Political Analysis 23, no. 1 (2015): 76–91.

- Barone, Guglielmo, Alessio D’Ignazio, Guido de Blasio, and Paolo Naticchioni. “Mr. Rossi, Mr. Hu, and Politics. The Role of Immigration in Shaping Natives’ Voting Behavior.” Journal of Public Economics 136 (2016): 1–13.

- Başkan, Filiz. “Globalization and Nationalism: The Nationalist Action Party of Turkey.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 12, no. 1 (2006): 83–105.

- Bonikowski, Bart, and Yueran Zhang. “Populism as Dog-Whistle Politics: Anti-Elite Discourse and Sentiments Toward Minority Groups.” Social Forces 102, no. 1 (2023): 180–201.

- Budge, Ian, and Dennis J. Farlie. Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-Three Democracies. London: Allen & Unwin, 1983.

- Cagaptay, S., and M. Yalkin. “Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 22, 2018, accessed March 14, 2023 at https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/syrian-refugees-turkey.

- Celep, Ödül. “Turkey’s Radical Right and the Kurdish Issue: The MHP’s Reaction to the Democratic Opening.” Insight Turkey 12, no. 2 (2010): 125–142.

- Cengiz, Fatih Çağatay. “Resistance to Change: The Ideological Immoderation of the Nationalist Action Party in Turkey.” Turkish Studies 22, no. 2 (2021): 462–480.

- Charney, Evan. “Identity and Liberal Nationalism.” American Political Science Review 97, no. 2 (2003): 295–310.

- Chiru, Mihail. “Early Marriages Last Longer: Pre-Electoral Coalitions and Government Survival in Europe.” Government and Opposition 50, no. 2 (2014): 165–188.

- Colomer, Josep M., and Gabriel L. Negretto. “Can Presidentialism Work Like Parliamentarism?” Government and Opposition 40, no. 1 (2005): 60–89.

- Conover, M., J. Ratkiewicz, M. Francisco, B. Goncalves, F. Menczer, and A. Flammini. “Political Polarization on Twitter.” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 5, no. 1 (2021): 89–96.

- Cox, Gary W. Making Votes Count: Strategic Coordination in the World’s Electoral Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Dancygier, Rafaela, and Yotam Margalit. “The Evolution of the Immigration Debate: Evidence from a New Dataset of Party Positions Over the Last Half-Century.” Comparative Political Studies 53, no. 5 (2020): 734–774.

- Debus, Marc. “Pre-electoral Commitments and Government Formation.” Public Choice 138 (2009): 45–64.

- Dinas, Elias, Konstantinos Matakos, Dimitrios Xefteris, and Dominik Hangartner. “Waking Up the Golden Dawn: Does Exposure to the Refugee Crisis Increase Support for Extreme-Right Parties?” Political Analysis 27, no. 2 (2019): 244–254.

- Erken, Ali. “Ideological Construction of the Politics of Nationalism in Turkey: The Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP), 1965–1980.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 20, no. 2 (2014): 200–220.

- Gessler, Theresa, and Sophia Hunger. “How the Refugee Crisis and Radical Right Parties Shape Party Competition on Immigration.” Political Science Research and Methods 10, no. 3 (2022): 524–544.

- Hangartner, Dominik, Elias Dinas, Moritz Marbach, Konstantinos Matakos, and Dimitrios Xefteris. “Does Exposure to the Refugee Crisis Make Natives More Hostile?” Stanford-Zurich Immigration Policy Lab Working Paper No. 17-02, 2017.

- Hug, Simon. Altering Party Systems. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

- Jolly, Seth, Ryan Bakker, Lisbeth Hooghe, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Anna Vachudova. “Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999-2019.” Electoral Studies 75 (2022): 102420.

- Kellam, Marisa. “Why Pre-Electoral Coalitions in Presidential Systems?” British Journal of Political Science 47, no. 2 (2017): 391–411.

- Luca, Daniele, Juan Terrero-Davila, Jonathan Stein, and Neil Lee. “Progressive Cities: Urban–Rural Polarisation of Social Values and Economic Development Around the World.” Urban Studies 60, no. 12 (2023): 2329–2350.

- Lynch, Marc. The Arab Uprisings Explained: New Contentious Politics in the Middle East. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Matthew Soberg Shugart. Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Major, Brenda, Alison Blodorn, and Galen Major Blascovich. “The Threat of Increasing Diversity: Why Many White Americans Support Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 21, no. 6 (2018): 931–940.

- Miguel, Edward. “Tribe or Nation?: Nation Building and Public Goods in Kenya versus Tanzania.” World Politics 56, no. 3 (2004): 327–362.

- Morales, Laura, Santiago Pardos-Prado, and Víctor Ros. “Issue Emergence and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition around Immigration in Spain.” Acta Politica 50 (2015): 461–485.

- Mudde, Cas. “Three Decades of Populist Radical Right Parties in Western Europe: So What?” European Journal of Political Research 52 (2013): 1–19.

- Odmalm, Pontus. “Coding and Using Party Manifestos: Pros, Cons, and Pitfalls.” In Sage Research Methods Cases Part 2. London: Sage, 2019.

- Opçin Kıdal, Arzu. “Continuity and Change in the Ideology of the Nationalist Action Party (MHP), 1965-2015: From Alparslan Türkeş to Devlet Bahçeli.” PhD diss., Bilkent University, Ankara, 2020. http://repository.bilkent.edu.tr/handle/11693/54497

- Samuels, David J., and Matthew S. Shugart. Presidents, Parties, and Prime Ministers: How the Separation of Powers Affects Party Organization and Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Secen, Sefa. “Explaining the Politics of Security: Syrian Refugees in Turkey and Lebanon.” Journal of Global Security Studies 6, no. 3 (2021): ogaa039. doi:10.1093/jogss/ogaa039.

- Secen, Sefa. “Electoral Competition Dynamics and Syrian Refugee Discourses and Policies in Germany and France.” European Politics and Society (2022. doi:10.1080/23745118.2022.2142399.

- Secen, Sefa. “Self-representation of Syrian Refugees in the Media in Turkey and Germany.” Forced Migration Review 70 (2022): 19–20.

- Secen, Sefa, and Mustafa Gürbüz. “Between Hospitality and Hostility: Public Attitudes and State Policies toward Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” In From Territorial Defeat to Global ISIS: Lessons Learned, edited by J. Goldstein, E. Alimi, S. Ozeren, and S. Cubuku, 193–202. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2021.

- Siegel, Alexandra. “Twitter Wars: Sunni-Shi’a Conflict and Cooperation in the Digital Age.” In Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East, edited by Frederic Wehrey, 157–180. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Tabellini, Marco. “Gifts of the Immigrants, Woes of the Natives: Lessons from the Age of Mass Migration.” The Review of Economic Studies 87, no. 1 (2020): 454–486.

- Tavits, Margit. “Party Systems in the Making: The Emergence and Success of New Parties in New Democracies.” British Journal of Political Science 38, no. 1 (2008): 113–133.

- Tudor, Maya, and Dan Slater. “Nationalism, Authoritarianism, and Democracy: Historical Lessons from South and Southeast Asia.” Perspectives on Politics 19, no. 3 (2021): 706–722.

- Vrânceanu, Alina. “The Impact of Contextual Factors on Party Responsiveness Regarding Immigration Issues.” Party Politics 25, no. 4 (2019): 583–593.

- Zárate, Michael A., Berenice Garcia, Azenett A. Garza, and Robert T. Hitlan. “Cultural Threat and Perceived Realistic Group Conflict as Dual Predictors of Prejudice.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40, no. 1 (2004): 99–105.