ABSTRACT

Democracy is backsliding throughout Southeast Europe but there are no signs of full democratic breakdown. Instead, political parties and their leaders incrementally undermine challenges to governmental authority while keeping electoral contest largely intact. This article introduces a special issue that aims to examine and explain democratic decline by looking at the prevalence of illiberal politics across countries and issues. In order to overcome the limitations of fixed regime classification we adopt a procedural lens and look into governing practices that gradually tilt the electoral playing field. Utilizing the concept of Illiberal politics allows us to examine sets of policies enacted by political parties in government with the aim to remain in power indefinitely. By tracing democratic decline in Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Albania, and Croatia we observe different patterns of weakness, but also common causes arising from weak institutions and inherited governance practices that preserve executive dominance, patronage, and informality.

1. Introduction

Has the third wave of democratization come to an end? This question is debated among scholars with no clear answer in sight. Diverging trends show continued, albeit weak, democratization but also erosion or collapse of democracy in different countries of the world. In the multiple instances of democratic backsliding, including some long-standing and consolidated democracies, authors notice an emerging global trend where some elements of democracy are kept intact while others have eroded (Bermeo Citation2016; Levitsky and Way Citation2015; Lührmann et al. Citation2018). The countries of Southeast Europe are no exception to these developments. It is possible to identify instances of incremental democratic backsliding in each throughout the past 10 years, although the speed of change and the final outcomes vary. This special issue aims to look at how the emerging democratic decline has and continues to play out in the countries politically labelled the ‘Western Balkans’.Footnote1 We utilize the procedural concept of illiberal politics that gives prominence to the role of political parties and their leaders. At the same time, it is our aim to include as many contributions of local academics coming from the region who live and work under conditions of deteriorating democracy and have strong personal investments in the countries they study.

In recent years, several authors have developed increasingly precise and empirically grounded classifications for regimes that are not fully democratic, but not authoritarian either (Merkel Citation2004; Schedler Citation2013; Levitsky and Way Citation2010). Still, there is no agreement on where to set the borderline between highly deficient democracies (democracies with adjectives) and authoritarian regimes that incorporate some elements of democracy (autocracies with adjectives). Classifying countries in this grey zone along a democracy–autocracy continuum, especially those with weak and unconsolidated governing institutions such as in Southeast Europe, is not straightforward. This is where it makes sense to initially focus on the aggregate of policies enacted by governing parties and rulers in order to map the direction of change taking place. By utilizing the concept of liberal politics, we aim to do just that. Illiberal politics are sets of policies that extend an electoral advantage for governing parties with the aim to remain in power indefinitely. This includes perpetuating advantageous socio-economic structures and governing practices, as well as specific and targeted restrictive actions against political opponents and independent institutions. By comparing the magnitude and intensity of illiberal politics we are able to draw conclusions on democratic and authoritarian trajectories of countries and the region as a whole.

Southeast Europe has seen its fair share of illiberal politics in recent years. Some of the most noticeable include the abuse of power with regard to elections, media, rule of law and public finances by the VMRO-DPMNEFootnote2 in North Macedonia, the SNSFootnote3 in Serbia, the SNSDFootnote4 in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the DPSFootnote5 in Montenegro. Yet all countries have been affected by politicians willing to bend the rules of the game to create an advantage for themselves and their party. This trend is confirmed by several indices that measure the quality of democracy, including the Varieties of Democracy index (V-Dem) used in this article. While elections are currently not under threat, what comes before and after elections very much is. A level playing field can no longer be taken for granted.

The rationale behind this special issue is to address the perceived lack of academic literature on the topic and to look more specifically into the practices and structures behind non-democratic governance. While there have been several recent publications addressing democratic backsliding in Southeast Europe (Bieber Citation2018; Kmezić and Bieber Citation2017; Perry and Keil Citation2018; Bieber et al. Citation2018; Bieber Citation2020), they either do not specifically look into the role of governing political parties, or do not cover most countries and several crucial topics, such as media, rule of law, and social movements. With this special issue, we want to examine the prevalence of illiberal practices, explore similarities across countries, and examine whether they are grounded in structural weaknesses particular to the region. This will allow us to draw conclusions on consequences for party competition and democracy in countries that aspire to join the European Union. An additional aim is to unpack the concept of democratic backsliding and the related concept of autocratization by adopting a procedural lens and looking into practices that, while not undermining democracy on their own, incrementally add up to create regimes that can no longer be called democratic.

This special issue adds value to the recent renewal of both academic and policy interest for democracy in Southeast Europe. A first set of articles consists of individual country case studies covering Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Kosovo, Albania, and Croatia. The authors highlight a common issue where governing parties readily use executive power to circumvent checks and balances for political and economic gain, while undermining institutions through reliance on informal politics. A second set of comparative articles examines the control of media, rule of law, and social movements, showcasing structural weaknesses while at the same time addressing the possibility to increase governmental transparency and accountability.

Our argument is that countries in Southeast Europe are not experiencing a sudden democratic reversal or breakdown of democracy. Rather, structural deficiencies centred around a strong executive, weak checks and balances and institutionalized informality are exploited by political parties to tilt the electoral playing field through the use of illiberal governing practices, while maintaining competitive elections. The following section gives a theoretical perspective on what makes these countries structurally similar and what constitutes illiberal politics. The subsequent section provides a comparative analysis of democracy in Southeast Europe using data from V-Dem. Finally, we give an overview of the contributions to this special issue.

2. Going, going, gone! Situating the concept of illiberal politics

Countries regularly experience slight shifts in levels of democracy, while sudden and noticeable regime change is rare. When small change is continuous and moves in a single direction, either towards democracy or authoritarianism, we can speak of incremental regime change. Most of academic literature is focused on the classification of regimes (Zakariah Citation1997; Merkel Citation2004; Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Schedler Citation2013). Yet it is equally important to look at the sum of processes affecting democratic institutions in order to understand incremental democratic decline. Almost all countries in Southeast Europe are in the midst of incrementally moving towards authoritarian rule.

This is well encompassed by what Bermeo calls democratic backsliding, especially in the form of gradual changes ‘that are legitimated through the very institutions that democracy promoters have prioritized’ but that do not lead to outright regime change (Bermeo Citation2016, 6). A conceptually broader but related term is autocratization that captures any deliberate change that move a regime away from a full democracy, including democratic backsliding, breakdown and authoritarian consolidation (Lührmann et al. Citation2018, 896). Such incremental changes largely target challenges to governmental authority, while keeping the electoral process intact. The term we use to describe the policies behind these changes is illiberal politics. By illiberal politics, we understand policies that are enacted (or proposed) by political parties in government with the aim to remain in power indefinitely while maintaining competitive elections. The resulting regimes maintain competitive multiparty elections but are neither democratic nor fully authoritarian. They have alternatively been described as ‘illiberal democracy’ (Zakariah Citation1997), ‘defective democracy’ (Merkel Citation2004), ‘competitive authoritarianism’ (Levistky and Way Citation2010), and ‘electoral authoritarianism’ (Schedler Citation2013).

Of the several attempts to classify regimes in the grey zone between democracy and authoritarianism, we will elaborate on the most relevant for regimes in Southeast Europe. All countries in this region can be described as hybrid regimes and Zakariah’s illiberal democracy is applicable to most of them. These are regimes that, while democratically elected, ignore constitutional limits to their power and limit basic rights and freedoms of citizens (Zakariah Citation1997, 22). Yet, illiberal democracy is a vague concept as it groups countries with minor deficiencies together with those that display serious authoritarian traits. Levitsky and Way’s competitive authoritarianism can be used to describe the regime in three countries, Serbia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia until 2017 (Bieber Citation2018), where competition is real but highly unfair. Regimes are competitive authoritarian when ‘formal democratic institutions exist and are widely viewed as the primary means of gaining power […] but they are not democratic because the playing field is heavily skewed in favour of incumbents’ (Levitsky and Way Citation2010, 5). The authors specify empirical conditions for such a regime based on attributes of free elections, broad protection of civil liberties, and a reasonably level playing field.Footnote6 The concept of competitive authoritarianism is currently the most suitable for classifying regimes in Southeast Europe as all regimes can be defined in relation to it. Other concepts, such as defective democracy (Merkel Citation2004) or electoral authoritarianism (Schedler Citation2013) have some value but are either imprecise or have limited applicability.

Classifications in the academic literature generally describe regime change once it has occurred, not the process of moving away from democracy. But using a single concept for the myriad of different ways that regimes (of Southeast Europe) move towards authoritarian rule does not allow us to understand this change in the absence of evident democratic breakdown. Therefore, more flexibility is needed to identify incremental erosion of democracy in regimes that are sliding towards competitive authoritarianism but are not ‘gone’ yet. This is exactly where illiberal politics is a useful tool for academic inquiry. By adopting a process-oriented approach that looks at governing practices of parties in power, illiberal politics can identify trends of incremental regime change that do not fully disregard democratic and liberal institutions and norms (to paraphrase, regimes that are ‘going, going … ’). Nevertheless, once a threshold is passed these regimes are considered ‘gone’ and can best be described as competitive authoritarian, or even as fully authoritarian. To put it in other words, while (competitive) authoritarianism is a strong symptom, illiberal politics are the disease that causes it, that can be identified, and ultimately addressed.

Illiberal politics play out in two broadly defined arenas, centred around the electoral component of democracy and the liberal component of democracy. What can be termed as constitutional liberalism is different from electoral democracy in a fundamental way, even though both are key components of a procedural understanding of democracy (Dahl Citation1989). While the electoral process serves to enable and concentrate political power, constitutional liberalism recognizes the need to restrict power through a protection of civil liberties and institutional checks and balances (Zakariah Citation1997, 22, 30). In this sense, the electoral lens has a positive, power-enabling view on democracy while the liberal lens has a negative power-restricting view on democracy. Both components are described in academic literature, both are empirically situated, and they can be challenged separately by actors with authoritarian agendas.

The electoral component of democracy can be subverted by manipulating free and fair elections as well as by creating an electoral playing field tilted in favour of incumbents. Illiberal politics erode the central electoral criteria of procedural democracy by limiting suffrage and the right to run for office, restricting freedom of expression, independent media and associational autonomy in the run-up to elections and in their aftermath (Dahl Citation1989). These measures target core elements of democracy and make rulers less accountable to citizens. Tilting the electoral playing field focuses on policies that limit the political opposition or that favour the ruling party in order to gain electoral advantage. Also called strategic electoral manipulation (Bermeo Citation2016, 13) it occurs long before elections are held and is centred on access to resources, media, and the rule of law (Levitsky and Way Citation2010, 10). This can include monopolizing and abusing political and economic power and resources, the use of state resources and institutions for partisan purposes, restricting independent media or supporting media biased in favour of incumbents, a subverted legal process that targets opposition and favours the party in power, or a mix of the above.

Empirical examples of illiberal politics aimed at the electoral component of democracy that were identified in Southeast European countries include: legal or physical limitations enacted on parts of the population that restrict their right to vote or to run for office; changes to electoral rules so they favour incumbents; hampering of voter registration and tampering of electoral rolls; gerrymandering electoral districts; political party control of electoral commissions; intimidation and restriction of opposition parties and independent candidates, whether legally, financially or physically, and keeping them off the ballot; laws or regulations that penalize public government criticism or discussing certain topics; prohibitions or restrictions of public assembly and association and other limitations to the freedom of expression; policies and actions that target the editorial, financial, and personnel independence of media and journalists and that censor media or lead to self-censorship; the use of government funds for partisan purposes and campaigning; and budgetary allocation preferences that closely align with partisan aims and party structures.

The liberal component of democracy is undermined by a lack of horizontal accountability and in more extreme cases by a dominance of executive power unrestrained by checks and balances. What Bermeo terms executive aggrandizement ‘occurs when elected executives weaken checks on executive power one by one.’ They accomplish this through legal channels by gradually disassembling institutions that effectively might challenge them and by restraining opposition (Bermeo Citation2016, 10–11). Targets usually include institutional and/or professional autonomy of the legislature, judiciary, media, and independent agencies (for example anti-corruption agencies). Constitutionally guaranteed civil liberties are a key element in protecting individuals and groups from the tyranny of the majority. If such protections are removed, limited or restricted through illiberal politics, parties in government can target vulnerable groups, minorities, or issues such as gender equality and reproductive rights for political gain. Democracy is thus subverted into unchecked rule of the majority dominated by the discourse of the governing party.

There is certain overlap of policies between the electoral and liberal components of democracy. A non-extensive list of illiberal politics in Southeast Europe that target the liberal component of democracy includes: stronger and persistent executive control over the legislature, judiciary and independent institutions; actions that circumvent existing legislative and judicial procedures; appointment of loyal individuals as heads of independent agencies instead of merit-based appointments; a roll back of checks and balances; policies that weaken the rule of law; an increased reliance on informal and non-institutional executive decision-making; legal, financial or thematic restrictions enacted on civil society; intimidation and harassment of protesters by police and government officials; conscious indifference in upholding and protecting civil liberties equally for all citizens; public shaming of vulnerable groups, minorities and government critics as tainted and a threat to the nation; and the removal of constitutionally protected civil liberties and group rights.

Policies from both components can be used to reinforce the position of the governing party, to weaken accountability or to counteract opposition politics. While (mostly) borderline legal, illiberal politics tend to create governance structures and practices that tend to reproduce themselves over time and that exert influence both formally (through policies and institutions) and informally (through networks and perceptions). In order to enact and implement policies that stabilize a competitive authoritarian regime both strong parties and coercive state capacities need to be in place (Levitsky and Way Citation2010). When they are not, competitive authoritarianism is more easily challenged by opposition, such as in the case of North Macedonia. Due to historical institutional legacies, we understand that there are distinct features of politics in each country studied in this issue. Therefore, we do not propose a common codebook of illiberal policies that are widely applicable. The contributing authors are given the freedom to identify and describe illiberal politics in a given context.

In order to identify common trajectories among countries, it is necessary to explore theoretical explanations for illiberal politics that are rooted in structural conditions specific to Southeast Europe. Here we rely on historical institutionalist insights on post-communist power relations and informality. For this purpose, we need to understand the moment of regime change that occurred across most of the Southeast Europe in the early 1990s. As a critical juncture, a historical moment of unusually high contingency, regime change from communist rule proved crucial in directing subsequent outcomes (Dolenec Citation2013, 6). Instead of paving the way for democracy like in most countries of East Europe, the introduction of competitive elections in the early 1990s led to the establishment of competitive authoritarian regimes that exploited structural weaknesses, and governance practices left over from the period of state socialism. The newly elected ‘democratic’ parties set themselves as an impendent to the development of free and fair electoral competition. Violent conflict that engulfed many countries shortly thereafter solidified the competitive authoritarian regimes. Structural constraints arising out of the overlapping political, social, and economic transitions (Offe Citation2003), as well as from transitions towards independence and from war to peace, made democratization all the more difficult and led to the entrenchment of newly elected elites.

To explain the governance practices that coalesced into competitive authoritarian rule Zakošek (Citation1997) highlights the absence of the rule of law and identifies three processes of post-communist power mutation, which are further elaborated by Dolenec (Citation2013). First is the concentration of power in the executive over parliamentary and judiciary branches of government, where the balance in division of power is subverted through legal means. Second, a conversion of political into economic power which helps create new economic elites out of political party affiliates and leads to the establishment of a clientelist relationship centred around the perpetuation of economic benefits. Finally, third, is a power dispersion from state administration and public institutions into a web of informal, party-controlled networks accompanied by a weakening of state capacity (Dolenec Citation2013, 20–24, 46–48, 55). The authoritarian parties that dominated regime change and politics in the 1990s used variations of these three processes to consolidate power and to remain in power.Footnote7 The practices they adopted became a new norm for electoral contestation that inhibited future democratization. While regimes did become noticeably more democratic in the 2000’s by adopting sets of liberal democratic policies, the engrained party practices of executive dominance, patronage and informality did not disappear. It is merely the tools, the illiberal politics used to achieve party aims, that have become more sophisticated, less repressive, and more informal (Vladisavljević and Krstić Citation2019). In this sense the ‘democratic rupture’ of the 2000s was real but at the same time shallow. The party leaders pushing illiberal politics today still rely on processes established decades ago as enduring obstacles to substantive democratization (Dolenec Citation2013).

Illiberal politics has produced an array of contemporary more or less misaligned ‘frankenstates’ in Southeast Europe (Krastev and Holmes Citation2018). These regimes combine elements of liberal democracy in a way that subverts its original meaning, leaving only empty shells of liberal democratic institutions as a façade to retain outside recognition. Beneath are established authoritarian practices of executive dominance, patronage, and informality that are used to enforce political stability. To sum up, the theoretical argument that this introductory article advances is that today’s illiberal politics have their roots in the post-communist power mutation set up in the early 1990s and with strong links to socialist governance practices. Actions of parties in government that manipulate elections, tilt the electoral playing field, disassemble checks and balances, and restrict civil liberties arise out of inherited governance practices that preserve executive party dominance, maintain clientelist linkages between the party and economy, and instrumentalize weak state institutions through informality.

3. Tracking democratic backsliding in Southeast Europe

Comparative measurement of democracy is always an imperfect business as there are few objective criteria to compare levels of democracy among regimes. Some of the most widely used indices of democracy, such as the Freedom in the World Index, rely on expert surveys or expert-coding. The complexity of the concept of democracy and its multiple meanings guarantee that each measure is a reflection of the selected attributes, coding decisions of authors, rules of aggregation, and structural conditions the experts are familiar with (Munck Citation2009).Footnote8 In this sense, democracy indices measure how well countries match scholarly and expert perceptions of a specific definition of democracy.

The V-Dem data we use in this article, more specifically the Liberal Democracy Index (LDI), are based on a definition of democracy well suited to measure democratic backsliding as defined earlier. The index adopts an empirical measure for a ‘thin’ definition of democracy ‘which recognises that liberal-democratic systems are the sum of two core components, democracy and liberalism’ rather than one that includes all desirable characteristics under a single definition (Mounk Citation2018, 99). This allows us to identify threats to independent institutions, the rule of law, and minority rights in countries that uphold competitive elections.

The V-Dem LDI is composed of two empirically distinct components that individually measure the electoral and liberal aspects of democracy. The Electoral Democracy Index (EDI) measures the elements of Robert Dahl’s polyarchy definition as it conforms to electoral democracy where rulers are responsible to citizens (Lührmann et al. Citation2018, 1322). It is an essential component for any understanding of democracy and is based on indicators of free and fair electoral contest and a level playing field, both before and in between elections. The Liberal Component Index (LCI) supplements electoral democracy in a way that reflects the presence of executive constraints, rule of law, and civil liberties that protect individual and minority rights against abuse from the state and the elected majority (Coppedge et al. Citation2019). As each indicator is available for comparison before aggregation, the ‘nuanced nature of the V-Dem data also makes it possible to discern unevenness across different traits of democracy, down to the level of specific indicators’ (Lührmann et al. Citation2018, 1330). The index is based on expert surveys and on a mix of additive and multiplicative aggregation rules. All data below are from V-Dem Dataset version 9 (Coppedge et al. Citation2019), while figures and tables are calculated by the author.

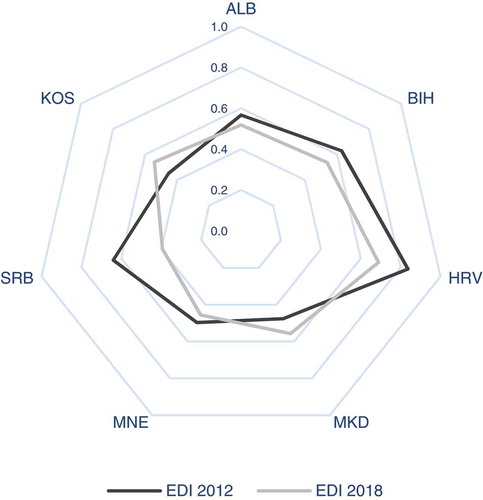

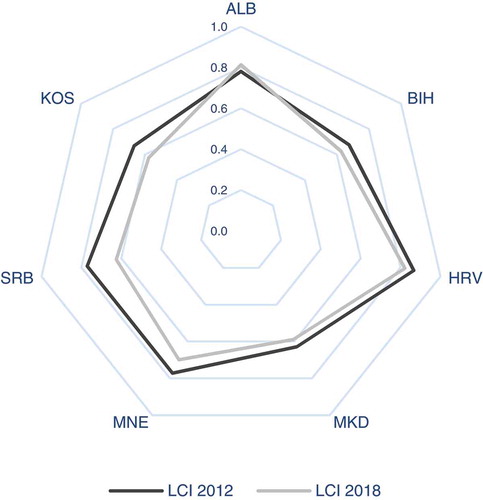

The general trend for Southeast Europe, according to the LDI, shows stagnation at best and democratic regression at worst. The data cover the past 7 years, coinciding with the final year of the European debt crisis, just before Croatia joined the European Union, and the last year data is available for at the time of writing. There are significant differences between countries and components of the index. As demonstrated in , the level of democracy in the region as a whole has not changed significantly. In fact, the countries ended up becoming more similar in 2018. Throughout the whole period levels of liberal democracy in Croatia are well above the regional average, largely due to high standards in the electoral process, but are in decline here as well. The onset of democratic backsliding did not occur simultaneously, and in some cases, it happened many years prior to the data presented here. For example, while decline in levels of liberal democracy in Croatia was preceded by a continuous rise until 2012, in North Macedonia they were already declining since 2004. During this period change has been most dramatic in Serbia, North Macedonia, and Croatia, while Montenegro, BiH, and Albania generally show a pattern of stagnation.

Disaggregating the LDI, it is possible to identify the challenges and weaknesses that each country faces. Also, change does not occur equally across both electoral and liberal components of democracy and not along the same components in all countries ( and ). Looking at the change between 2012 and 2018 across the EDI and LCI indices confirms relative stagnation in Albania while showing that Croatia and BiH largely experienced decline in the electoral component of democracy. Montenegro and Kosovo show decline in the liberal component, along with an improvement on the EDI in the latter country. Serbia shows sharp decline along both components, while recent developments in North Macedonia boosted its EDI score above the 2012 levels, with the LCI still remaining low. The regional average indicates incremental decline in levels of both liberal and electoral democracy.

Observing the aggregate yearly change over a longer period of time (since the 2004 European Union expansion) shows us the amount and direction of change in each country during those 14 years. All countries have experienced a decline in levels of liberal democracy (LDI) or stagnation, while Kosovo’s improvement is negligible. Decline is most pronounced in Serbia and North Macedonia, despite recent improvements in the latter (). Decline in the electoral component (EDI) is again noticeable in all cases except Albania and Kosovo, and most significant in Serbia, followed by BiH and Croatia. The liberal component (LCI) shows an improvement in Croatia and Albania, while decline is most pronounced in North Macedonia and Serbia. In other words, the level of democratic backsliding is largely due to deficiencies related to the electoral process in Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro, and BiH, and due to shortcomings of the liberal component in North Macedonia and Kosovo.

Table 1. Aggregate change for LDI, EDI and LCI, 2004–2018.

The intensity of change can be observed by aggregating the absolute values of yearly change for LDI (). We notice that Kosovo and Croatia have experienced significant change over the past 14 years, as well as North Macedonia and Serbia. These four regimes can be described as dynamic. Whereas Serbia largely experienced democratic decline, Croatia experienced both an increase and decline in levels of liberal democracy that largely evened out the final LDI score. On the other hand, BiH, Albania and Montenegro have seen very little change over the same period and can best be described as static regimes.

It is also possible to identify variables for each country that significantly contribute to democratic backsliding using the V-Dem data (Coppedge et al. Citation2019). For the three regimes identified as static, any backsliding happened largely due to issues related to tilting the playing field before elections and executive aggrandizement that ignores judicial and legislative competences. The dynamic group exhibits a much more diverse set of flaws. The main issue in Croatia is lacking freedom of expression, little media independence, and media censorship. This is also the case in Serbia, along with tilting the playing field before elections and a lack of legislative constraints on the executive. Kosovo has a problem with judicial constraints on the executive, as well as civil liberties and equality before the law. Finally, North Macedonia has issues with all forms of executive constraints, deficient freedom of expression and media independence, as well as civil liberties.

The literature on democratic backsliding in Southeast Europe is very recent, although the trend became evident at least as far back as 2012. Countries where democratic decline has been ongoing for almost a decade are present in the literature as case studies. Yet, there have been few attempts to explore systemic issues that cross-cut individual cases or the important role of political parties in shaping this change.

Dolenec (Citation2013) authored one of the first works that looks at how authoritarian practices persist in the region. While not specifically examining democratic backsliding, her book addresses both systemic explanations and the role of political parties and leaders, with most of the empirical analysis limited to Croatia and Serbia. A policy study by the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group (edited by Kmezić and Bieber Citation2017) was an early foray into exploring the crisis of democracy in Southeast Europe through the lens of local adaptation to external (European Union) policy, resulting in what the authors term ‘stabilitocracies’. Under a stabilitocracy regime actions that may be considered repressive are legitimized domestically with reference to European standards and through piecemeal adoption of European Union policy guidelines. The personal legitimation of national leaders with authoritarian traits is also important and occurs through multilateral summits and supportive statements from European leaders. Survey-based research with a focus on youth in Southeast Europe has found that support for leaders with an authoritarian style of governance, unchecked by legislative and judicial institutions and unquestioned by media, is significant and with marginal differences between countries (see Turčilo et al. Citation2019). This corresponds to the processes of post-communist power mutation that emphasize the political, economic and personalized power of strong leaders. Even though these young peoples had no experience of communist authoritarian rule, their perceptions of a leader’s qualities are shaped by the institutional legacy and practices inherited from and embedded during early post-communist democratization.

In his forthcoming book, Bieber (Citation2020) expands on an earlier article (Bieber Citation2018) and examines the return of competitive authoritarianism by looking at internal and external driving factors and restrictions. He notices a different type of non-democratic rule than in the 1990s, one that pays more attention to maintaining a semblance of competitive elections while exploiting an institutional weakness to undermine civil liberties and tilt the electoral playing field. A special issue of Southeastern Europe (edited by Perry and Keil Citation2018) explores the emergence of various forms of state capture by predatory elites. Their aim, according to the authors, is not to explicitly undermine democracy, but to capture weak state institutions in order perpetuate clientelist forms of economic power. In the end, these regimes end up weakening democracy in their path. Bochsler and Juon (CitationForthcoming) look at the systemic effect of populist governments on the quality of democracy in the region and find a consistent negative effect on the quality of competition, while effects on the quality of democracy are context dependent. Finally, a volume edited by Bieber et al. (Citation2018) tackles issues of democratic backsliding by examining the role of political elites through a large number of case studies from Eastern Europe but does not cover more recent events in North Macedonia, Serbia or BiH.

The region of Southeast Europe is clearly regressing in quality of democracy, with exceptions in few countries and segments. Albania, in particular, presents a case where it is necessary to look deeper into governance and electoral practices and trace whether democratization has been able to make a break with the past. The reasons for the recent regression in Croatia warrant further attention, as does Kosovo’s failure to make a significant move towards democracy. The change of government in North Macedonia has created possibilities for a new push to further democratize and it is pertinent to follow those developments and learn from the past. Recent civic protests in Serbia and BiH could have potential to halt democratic breakdown and induce change if they are able to mobilize a broad, national following. But all progress is tentative and uncertain as the region has for several decades remained volatile and stuck between a historical legacy of authoritarian rule and a democratic future that has not materialized.

4. Contributions to the special issue

This special issue aims to examine democratic backsliding by looking at the prevalence of illiberal politics across countries and issues. The case studies of Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, BiH, Kosovo, Albania, and Croatia all roughly follow a common structure. These articles give a brief description of the country context, including the party system and contentious political issues. The main section of each focuses on governance practices or enabling factors of democratic decline. The authors identify proposed or enacted policies by governing parties that are aimed at perpetuating their rule. This includes policies targeting the electoral and liberal components of democracy and their four dimensions: explicit electoral manipulation, tilting the electoral playing field, removing checks and balances on the executive, and restricting civil liberties. As specific illiberal policies are context dependent and differ between countries, the authors of the case studies are left to decide which ones to prioritize. Finally, the case study articles address possible causes for the rise in illiberal politics. The authors explore whether these can be linked to structural factors embedded in a historical understanding of institutions, or to actors’ motivations driven by opportunity, threat perceptions or identity-related narratives.

The first article by Dušan Pavlović examines the gradual demise of democratic institutions in Serbia. He argues that since coming to power in 2012, the SNS has undermined almost all elements of democracy, including free and fair elections and independent media, and has extensively misused public resources. Especially the latter is important as the party improved an existing system of extractive institutional design. The system rewards privileged access to public resources in exchange for electoral support, thus creating and reinforcing an uneven electoral playing field. The sum of illiberal policies has propelled the regime in Serbia back into the competitive authoritarianism of the 1990s.

Borjan Gjuzelov and Milka Ivanovska Hadjievska examine the case of North Macedonia by looking at the institutional and symbolic aspects of illiberal politics during the 11-year rule of VMRO-DPMNE. The institutional aspect examines party abuse of electoral processes, media reporting, access to rule of law, and distribution of public resources with the aim to create an uneven electoral playing field. The symbolic aspect looks into the intertwined Macedonian nationalism and ‘antiquization’ policies of VMRO-DPMNE that sought to legitimize illiberal politics and discredit opposition through a focus on identity politics. As a prime example of competitive authoritarianism in Southeast Europe, North Macedonia is also the only country that, at least seemingly, has been able to break the trend of democratic backsliding.

The case study of Montenegro, written by Olivera Komar, examines a country that is touted as the front-runner of European integration but where critical voices have been systematically weakened. She focuses on three illustrative examples of illiberal politics that have been successful at keeping the DPS party (and its party leader) continuously in government for almost three decades. Through cases of party control over public broadcasting, use of public resources to secure votes, and curtailing the independence of academic institutions, Komar examines illiberal policies enacted by DPS that have incrementally positioned Montenegro as a competitive authoritarian regime.

Damir Kapidžić looks at illiberal politics at the subnational level in order to explain the absence of democratic breakdown in BiH. He finds that autocratization is contained within subnational arenas by dominant parties representing a single ethnic group and constrained by multi-level and cross-ethnic checks and balances. While consociational power-sharing enables subnational leaders to establish competitive authoritarian regimes, it limits the spread and ramifications of illiberal politics to higher levels of government. Kapidžić analyses three cases of illiberal politics dealing with restrictions to the freedom of assembly, weakening independent media, and patronage in elections. He identifies deliberate attempts by ruling parties, especially the SNSD, to create and maintain an uneven electoral playing field. The result is differentiated democratic backsliding where parts of the country are significantly more authoritarian than others.

Writing on Kosovo, Adem Beha and Arben Hajrullahu trace how policies aimed at democratization and Europeanization have been misused by political elites to remain in power and to capture public resources. Policy priorities for Kosovo were largely defined by international actors and focused on keeping the country stable rather than on democratization and sustainable development. However, policy development and implementation relied on Kosovar political parties that use weak state institutions to subvert policymaking into a struggle for power and resources, while masking the effort as democratization and Europeanization. The weak economy, incomplete international recognition and divided society all contribute to the primacy of strong party-based clientelist networks.

The case study of Albania by Gentiana Kera and Armanda Hysa examines clientelist practices and private funding of election campaigns. Backed up by interview data, they adopt an ethnographic lens in order to identify donors, recipients and the impact of informal clientelism. Their research uncovers a widespread practice where, in order to gain an electoral advantage, parties engage in informal contracts with private donors, thus side-lining official regulations on party financing. Undeclared private money or services during election campaigns are found to increase the risk of future political favours for involved actors. The repercussion is a general dissatisfaction with the electoral process, especially in regard to influence of money on politics, and a perception of implicit reliance on clientelism for employment, education and services even beyond electoral contest.

The article on democratic decline in Croatia, written by Dario Čepo, focuses on the period after the country’s accession to the European Union. The author finds that during this time the ruling HDZFootnote9 was able to maintain an electoral advantage by relying on structural weaknesses of the political system it had shaped during the transition in the 1990s. Through illiberal politics the party systematically weakened autonomous institutions, preserved influence over the judiciary, and subverted independent media. While the extent of all these practices is still limited, their impact adds up to consistent but incremental democratic backsliding that is still ongoing.

The comparative articles focus on specific issues across several (but not necessarily all) Southeast European countries. Their aim is to gain a broader understanding of the relevance of individual aspects of democracy in Southeast Europe. As these issues have central importance in defining liberal democracy, any deficiencies and restrictions can significantly reduce democratic quality. At the same time, they are most often the target of government policies and practices that we have identified as illiberal politics.

Věra Stojarová’s comparative article looks at control of media and constraints on media independence in Southeast Europe. She argues that illiberal politics target all aspects of the profession not with the explicit aim to eliminate independent media or silence dissent, but to overpower it with pro-government reporting. Her article examines the legislative framework and the role of regulatory bodies, issues of defamation and media ownership, economic pressure and censorship, as well as physical and verbal intimidation of journalists. Throughout the region the role of independent media is found to be weak and compromised. Instead of being a watchdog, the most influential and relevant media outlets engage in favourable reporting of executive leaders while critical voices are side-lined.

The second comparative article focuses on the nexus between rule of law and democracy. Marko Kmezić argues that the absence of a democratic rule of law is purposefully exploited by ruling elites in order to misuse fragile institutions to their advantage. He demonstrates this through a comparative analysis of elements related to electoral processes (exploitation of public resources, media dominance, electoral registers and voter fraud) and media freedom (historical legacies, weak regulation, informal pressure and government influence). In this sense, he argues that due to deficiencies in rule of law, the countries of the region lack the substance not just of liberal but also of formal democracy.

Gazela Pudar Draško, Irena Fiket and Jelena Vasiljević examine the role of social movements and their potential to generate democratic change in authoritarian societies. Based on an ethnographic approach and in-depth interviews the authors compare social movements in Serbia and North Macedonia and assess their capacity to act as a corrective when other institutions are subverted, when trust in official public institutions is critically low and when competitive electoral contest is no longer certain. They conclude that while there are several similarities across the two cases, the Macedonian movements displayed greater capacity to cooperate with each other, as well as with other social players, in comparison to emerging social movements in Serbia, to greater effect.

In the concluding article to this special issue, Věra Stojarová focuses on the central themes which link all articles: undermining free and fair elections, weakening independent media, limiting the role of judiciary, gaining privileged access to public resources, and independent institutions and executive oversight. She examines the prevalence of illiberal politics and similarities among Southeast European countries across these themes. In searching for causes of democratic decline she explores the impact of structural deficiencies, unrestrained executives, and institutionalized informality.

Tracing the recent rise of illiberal politics in Southeast Europe is not straightforward. So far there has not been an abrupt democratic breakdown or descent into authoritarianism in any country of the region. Instead what we notice are incremental changes, executed by governing parties through illiberal policies, that target a broad range of issues and actors with the aim to reduce governmental accountability and electoral competitiveness. The contributions to this special issue aim to shed light on a region-wide political process and to examine the causes of democratic decline in each country individually and comparatively. By examining structural deficiencies that were institutionalized during the post-communist transition period the authors highlight country-specific enabling factors that allow political parties and their leaders to subvert democracy to their own gain. The topic of this special issue is both timely and relevant as the countries of the Western Balkans redefine their relationship towards the European Union or adopt to shifting internal policies of the European Union, in the case of Croatia.

In a region where democracy has not been fully consolidated it is not prudent to advance an agenda of political stability at the expense of liberty. With the European Union accession process at a standstill and third actors exerting increasing influence, it becomes necessary to assess threats to democratic institutions in Southeast Europe arising from illiberal politics of their elected leaders.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Nebojša Vladisavljević, Daniel Bochsler, and Věra Stojarová for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Damir Kapidžić

Damir Kapidžić is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at the Faculty of Political Science, University of Sarajevo in Bosnia and Herzegovina. His research looks at ethnic conflict, political parties and power-sharing, as well as formal and informal processes through which democratic or authoritarian politics are institutionalized. Much of his focus is on countries in Southeast Europe, but also includes comparative perspectives from Southeast Asia, East Africa and the Middle East.

Notes

1. The countries we examine are: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. We include Croatia because it shares very many traits with other countries, even though it is no longer officially part of the Western Balkans after joining the European Union in 2013. While we acknowledge the difference between the terms ‘Western Balkans’ and ‘Southeast Europe’, individual articles in this special issue use the terms interchangeably.

2. Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization – Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity.

3. Serbian Progressive Party.

4. Alliance of Independent Social Democrats.

5. Democratic Party of Socialists.

6. To calculate their measures for classification, the authors exclusively rely on multiplicative aggregation of variables which leads to an exaggeration of single structural flaws in the classification (Levitsky and Way Citation2010, 365–371).

7. Vladisavljević (Citation2008) argues that these trends have roots even further back in the past, in the radical decentralization of political and economic power in Yugoslavia in the 1970s and 1980s, and were propagated by centrifugal nationalist mobilization in the early 1990s.

8. The Democracy Barometer attempts to provide an alternative solution by relying on objective and comparable data instead of expert assessments but is (still) limited in scope and therefore comparability (Merkel et al. Citation2018).

9. Croatian Democratic Union.

References

- Bermeo, N. 2016. On democratic backsliding. Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1: 5–19. doi:10.1353/jod.2016.0012

- Bieber, F. 2018. Patterns of competitive authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. East European Politics 34, no. 3: 337–54. doi:10.1080/21599165.2018.1490272

- Bieber, F. 2020. The rise of authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bieber, F., M. Solska, and D. Taleski, eds. 2018. Illiberal and authoritarian tendencies in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Bochsler, D., and A. Juon. forthcoming. Authoritarian footprints in Central and Eastern Europe. East European Politics.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C.H. Knutsen, S.I. Lindberg, J. Teorell, D. Altman, M. Bernhard, et al. 2019. V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] dataset v9. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. doi:10.23696/vdemcy19.

- Dahl, R. 1989. Democracy and its critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dolenec, D. 2013. Democratic institutions and authoritarian rule in Southeast Europe. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

- Kmezić, M., and F. Bieber, eds. 2017. The crisis of democracy in the Western Balkans. An anatomy of stabilitocracy and the limits of EU democracy promotion. Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group. https://biepag.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/final.pdf.

- Krastev, I., and S. Holmes. 2018. Imitation and its discontents. Journal of Democracy 29, no. 3: 117–28. doi:10.1353/jod.2018.0049

- Levitsky, S., and L.A. Way. 2010. Competitive authoritarianism: hybrid regimes after the cold war. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Levitsky, S., and L.A. Way. 2015. The myth of democratic recession. Journal of Democracy 26, no. 1: 45–58. doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0007

- Lührmann, A., V. Mechkova, S. Dahlum, L. Maxwell, M. Olin, C. Sanhueza Petrarca, R. Sigman, M.C. Wilson, and S.I. Lindberg. 2018. State of the world 2017: Autocratization and exclusion? Democratization 25, no. 8: 1321–40. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1479693

- Merkel, W. 2004. Embedded and defective democracies. Democratization 11, no. 5: 33–58. doi:10.1080/13510340412331304598

- Merkel, W., D. Bochsler, K. Bousbah, M. Bühlmann, H. Giebler, M. Hänni, L. Heyne, et al. 2018. Democracy barometer. Methodology. Version 6. Aarau: Zentrum für Demokratie.

- Mounk, Y. 2018. The undemocratic dilemma. Journal of Democracy 29, no. 2: 98–112. doi:10.1353/jod.2018.0030

- Munck, G. 2009. Measuring democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Offe, C. 2003. Herausforderungen der Demokratie: Zur Integrations- und Leistungsfähigkeit politischer Institutionen. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

- Perry, V., and S. Keil. 2018. The business of state capture in the Western Balkans. An introduction. Southeastern Europe 42, no. 1: 1–14. doi:10.1163/18763332-04201001

- Schedler, A. 2013. The politics of uncertainty. Sustaining and subverting electoral authoritarianism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Turčilo, L., A. Osmić, D. Kapidžić, S. Šadić, J. Žiga, and A. Dudić. 2019. Youth study 2018. Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Vladisavljević, N. 2008. Serbia’s antibureaucratic revolution: Miloševic, the fall of communism and nationalist mobilization. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vladisavljević, N., and A. Krstić. 2019. Competitive authoritarianism and populism in Serbia under Vučić in political cartoons. Unpublished manuscript.

- Zakariah, F. 1997. The rise of illiberal democracy. Foreign Affairs 76, no. 6: 22–43. doi:10.2307/20048274

- Zakošek, N. 1997. Pravna država i demokracija u postsocijalizmu. Politička misao 34, no. 4: 78–85.