ABSTRACT

This article explores to what extent strategic planning is important for the implementation of co-creation, the process through which public authorities solve problems with partners outside their organization. The article explores local government in Croatia and Slovenia, where structural conditions – problems with administrative capacity, low strategic planning capacities, a weakly embedded civil society and the private sector in the provision of public services – are unfavourable for the implementation of co-creation. Results show that strategic planning has a positive effect on the uptake of co-creation. How comprehensively co-creation is implemented also depends on the motivation and preparedness of professionals. Even in an environment where dialogue and collaboration between different partners and levels of government are not well-embedded, co-creation is on the rise and most frequently used for agenda setting.

Introduction

Public authorities have seen a promotion of collaborative approaches that aim to both reinvigorate their democratic legitimacy and their ability to solve problems efficiently and effectively (Sørensen and Bentzen Citation2020). One of these approaches is co-creation, defined here as a collaborative process through which public authorities attempt to generate solutions to problems and seek value by working together with citizens and partners in the private, public and voluntary sectors (Torfing et al. Citation2019, 802).

Co-creation is argued to be the solution to austerity (Bovaird et al. Citation2017), the trust deficit (Fledderus et al. Citation2014) and a lever for the post-pandemic recovery (Ansell et al. Citation2020; Scognamiglio et al. Citation2022). The principles that underpin co-creation – partnership across society and citizen participation – are at the core of sustainable development goals (United Nations Citation2019; Ansell et al. Citation2022) and promoted by the OECD (Citation2017), the Council of Europe (Citation2018) and the United Nation’s programme for urban development (UN Habitat Citation2009). Due to the complexity and interdependence of today’s problems and the recognition that solutions require collaboration across sectors of society and with citizens, co-creation has become a principle of public sector reforms in Europe and worldwide.

To achieve its promised outcomes, co-creation requires government support, new types of leadership, a trained and motivated professional workforce and willing partners to co-create, all underpinned through strategy (Baptista et al. Citation2020; Jukić et al. Citation2021; Van Gestel and Grotenbreg Citation2021; Torfing et al. Citation2021). This article explores the importance of strategy for co-creation by asking to what extent does strategic planning help local governments with the implementation of co-cration. The role of strategic planning for co-creation is not well explored in the literature. Most of the research is qualitative and supportive of a positive relationship (Ongaro et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Sicilia et al. Citation2019). Hypothesis testing and generalizable data are rare (Parrado et al. Citation2013). Based on original survey data, this article provides quantitative evidence on what tangible actions an organization (the meso level) can take in terms of devising a strategy for implementing co-creation while taking macro (e.g., government support) and micro level (e.g., the role of professionals or street-level bureaucrats) variables into account.

Co-creation appears to have diffused across Northern Europe and in countries with a well-organized civil society with traditions of public-private collaboration (Fotaki Citation2011; Parrado et al. Citation2013; c.f. Van Gestel and Kuiper Citation2022). On the other hand, little is known about the coverage and the application of co-creation in conditions that can be described as less favourable. These include administrative traditions where public organizations exhibit lower administrative capacity and where the private sector, civil society and citizens are traditionally weakly embedded in the provision of public services.

We find such conditions in South-Eastern Europe (SEE) among post-communist countries with a legacy involving centrally-planned state economies. This article studies the role strategic planning plays in the implementation of co-creation among local authorities in SEE drawing on the example of Croatia and Slovenia. Under the auspice of democratization and European integration, greater commitment to partnership, collaboration and dialogue in day-to-day government practices has been pursued in this part of Europe, calling for greater attention to the region. Because institutions in post-communist countries are less stable and responsive to the needs of society, co-creation might be even more important than in democratically advanced nations as an opportunity for citizens, businesses and others to develop services that suit their needs helping governments to serve citizens better.

In pursuing the outlined research objectives, the article makes several contributions to the literature. Firstly, the article links the macro (contextual) level of an organization with its meso level (organizational strategy on co-creation). In doing so, it pairs the literature on strategic management with the one on administrative traditions. The study controls for the involvement of professionals (street level bureaucrats) as those located the micro level of organizations. The research design, therefore, makes it possible to outline the importance of strategic planning in terms of what an organization can do on its own, given its administrative context and provided what happens at the front line. Secondly, the article expands our understanding on local government co-creation to territories in the ‘new Europe’ which have thus far been rarely explored in comparative research (Wiktorska-Święcka Citation2018). Finally, the article provides a methodological contribution by developing an operational definition of co-creation which can be applied and developed in future research.

Theoretical framework

Co-creation

Co-creation is one of the public policy approaches promoted under post-New Public Management (NPM) governance narratives (Sorrentino et al. Citation2018). In post-NPM governance, relations between public authorities and societal actors move away from regulative and legal-authoritative relations and become more deliberative and dialogic. Public institutions recognize that contemporary challenges cannot be solved by the state alone and that there is a benefit to include other societal actors as policy-making partners. In these circumstances, the role of the state is to facilitate and enable participation and collaboration through administrative capacity and other resources.

This article defines co-creation as (Torfing et al. Citation2019, 802):

a process through which two or more public and private actors attempt to solve a shared problem, challenge, or task through a constructive exchange of different kinds of knowledge, resources, competences, and ideas that enhance the production of public value in terms of visions, plans, policies, strategies, regulatory frameworks, or services, either through a continuous improvement of outputs or outcomes or through innovative step-changes that transform the understanding of the problem or task at hand and lead to new ways of solving it.

The implementation of co-creation varies in breadth and coverage given the partners and the type of activities that partners are involved in. The core objective of co-creation is to move from consulting with stakeholders to co-creating services and policies with partners. This includes co-creation for design, production, planning, implementation, delivery, and the evaluation of services and policies. Partners play an active role, but the extent of policy activity varies. Most of the literature places activity on a continuum. For instance, Torfing et al. (Citation2019) developed the co-creation ladder where higher rungs feature the design and implementation of new and improved solutions. The most advanced rung involves collaborative innovation based on joint agenda-setting, problem definition, joint design, coordinated implementation and evaluation (‘enhanced co-production’). The lowest rung involves the improvement of existing services (the co-production of services, consumer co-production or lower order co-creation, see Osborne and Strokosch Citation2013; Nabatchi et al. Citation2017). At this rung partners are mainly service users and their role is decided by managers and professionals (Bovaird and Loeffer Citation2012).

On the example of citizens, Nambisan and Nambisan (Citation2013) distinguish activity by partner roles. As ‘ideators,’ partners conceptualize solutions to well-defined problems in public services. In the role of ‘designers,’ they design or develop implementable solutions to well-defined problems. As ‘diffusers,’ partners directly support and facilitate the adoption and diffusion of innovations among targeted populations. Bovaird and Loeffer (Citation2012) distinguished between the co-planning of policy (deliberation), co-design of services (consultation), co-prioritization of services (decision-making), co-financing, co-management, co-delivery and co-assessment. There are, therefore, different elements to co-creation based on the actors involved and the aimed activity. This study captures these elements together in the operationalization of co-creation.

Strategic planning

While co-creation is promoted for resolving today’s complex problems, it is not easy to set up and implement (Bryson et al. Citation2015). Because co-creation evolves around complex and dynamic multi-partner and cross-sector collaborations, several scholars have suggested that a strategically planned approach is necessary for the successful implementation of co-creation (Osborne and Strokosch Citation2013; Torfing Citation2016; Baptista et al. Citation2020; Sicilia et al. Citation2019; Ferlie Citation2021).

Strategic planning is warranted for managing rapidly changing environments (Jacobsen and Johnsen Citation2020). Strategy in different shapes and forms can help organizations navigate through actions for implementing reforms and adapting to the environment’s present and future needs (Brown and Osborne Citation2012; Ferlie and Ongaro Citation2015; Bryson et al. Citation2009). These needs relate to the external environment, internal organizational structures and the behaviours and attitudes of the professionals, managers and people tasked with implementation (Johanson Citation2009). A strategic approach addresses all of these aspects and goes beyond the day-to-day operational level in the sense that it focuses on the long-term and adopts an organizational-wide approach (Ansoff Citation1980; Ferlie Citation2021). Writing about local government, Hințea et al. (Citation2019, 242) define strategic planning as ‘a set of actions that would significantly change the community over a long period of time.’

In this article, strategic planning is conceived as a set of concepts, procedures and tools that organizations use when determining their overall strategic direction and objectives (Bryson Citation2011). Strategic planning is a formal and rational process that allows organizations to analyse the internal and external environment (Ansoff Citation1980; Poister et al. Citation2013). Strategy-making consists of formal strategies, plans, mission statements as well as practices to regularly review, monitor and upgrade plans through tools and mechanisms as new information comes about (Bryson Citation2011; Poister et al. Citation2013).

Strategic planning is associated with NPM reforms as a tool for organizing budgeting, measuring performance and increasing efficiencies. In post-NPM narratives, it can help organizations in their evolution or transition towards collaborative forms of governance such as co-creation (Joyce et al. Citation2014). In this sense, strategic planning is indispensable for co-creation, because bringing together diverse partners requires planning. Strategic planning can also formalize roles and objectives, potentially clarifying responsibilities and mobilizing partners for co-creation. Existing studies support the positive effects of strategic planning for co-creation. Sicilia et al. (Citation2019) found, for example, that managers can influence the adoption and implementation of co-production through organizational (e.g., professionals roles and managerial tools) and procedural (e.g., decisions over recruitment, preparation and process design) elements. Other studies found that strategic planning helps to introduce strategic thinking at different stages of co-creation by linking resources with objectives and embedding new partners in existing organizational decision-making structures (Ongaro, Mititelu et al. Citation2021a; Ongaro, Sancino et al. Citation2021a). These findings are congruent with some of the literature exploring the effect of strategic planning for performance (Walker and Andrews Citation2015; Johnsen Citation2019; Elbanna et al. Citation2016; c.f. Desmidt and Meyfroodt Citation2018).

Opportunities for co-creation in Croatian and Slovenian local governments

Co-creation reportedly flourishes in decentralized countries with strong local autonomy, a tradition of collaboration between the private and the public sectors and a vital civil society (Torfing et al. Citation2019). Local government in Croatia and Slovenia faces challenges in all these, meaning that co-creation is unlikely to be well-embedded within society, leading to an expectation of isolated examples. Having transitioned from a communist to a democratic political order in the 1990s, the public administration and local government of Slovenia and Croatia are commonly studied from the perspective of ‘Eastern European,’ ‘new’ and ‘post-communist’ democracies or the Balkan and South-Eastern European model (Heinelt et al. Citation2006; Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019). Democratization meant that accountability systems had to be put in place as prescribed in the Weberian old public administration model. The implementation of accountability mechanisms coincided with NPM reforms becoming the dominant reform trend in consolidated democracies (e.g., market mechanisms promoting efficiency and choice). Under pressure from international donors, Slovenia and Croatia introduced reforms combining Weberian and NPM public management models which resulted in inconsistent reforms and a fertile ground for the existence of conflicting demands on the public administration.

Both countries have a legal-statutory tradition where the constitution specifies territorial competences which aligns them with the Continental Napoleonic model of traditional public administration (Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019). Compared with some post-communist countries, Croatian and Slovenian local authorities have lower fiscal discretion and functional responsibilities, contributing to a weaker institutional position vis-à-vis the central government (Alibegović et al. Citation2013; Kukovič et al. Citation2016). Because regulatory changes are required for local government to act upon own initiatives, innovation and change at the local level are dependent on support and incentives provided through central government policy. Innovation in post-communist countries might therefore proceed with a top-down dynamic meaning that co-creation is mandated from the top, typically through central government laws and initiatives, rather than administrative and legal leeway at the bottom.

Similarly to Southern European countries with longer democratic traditions, Croatia and Slovenia feature small scale and fragmented local government structures, which affect the quality of administrative capacity. Decentralization has been a key reform priority to improve the quality of service delivery but both countries have been slow to decentralize. To manage territorial fragmentation and stalling decentralization, government policy in both countries promotes inter-municipal cooperation, which one can see as a form of co-creation between public sector entities (Rakar et al. Citation2015; Koprić et al. Citation2015). Co-creation between public and private partners has been eased with public-private partnerships laws implemented in the 2010s (Grafenauer and Klarić Citation2011). However, local private sector engagement is not developed due to administrative burdens that discourage firms and a negative perception of the public towards the private sector as a service provider (Hrovatin Citation2010; Metaxas and Preza Citation2015).

Increasing citizen participation has also been challenging even though legal frameworks establishing mechanisms for democratic accountability and direct citizen participation have existed since the early 1990s (Council of Europe Citation2011; Citation2016). The local self-government acts of Croatia and Slovenia provide citizens opportunities for direct participation in decision-making through assemblies, referendums and popular initiatives. Several cities have introduced participatory budgeting but struggle to achieve good levels of participation (Švaljek et al. Citation2019; Fiedler et al. Citation2020). Persistent political instability and corruption have also alienated citizens from local government (Škrbec and Dobovšek Citation2013; Vukovič Citation2017).

Structural conditions are not all unfavourable to co-creation. Croatia and Slovenia’s accession to, and current membership in, the EU have been influential for shifting from a ‘government’ mode or ‘governing over society’ to a ‘governance’ mode or ‘governing with society’ (Börzel and Buzogány Citation2010; Börzel Citation2010). The effects of the partnership principles beyond EU programmes and the local government are empirically unexplored (Demidov Citation2017; Dąbrowski Citation2014). Interests groups have become a constitutive part of the political system and are relatively well formalized (albeit some lack stable streams of income) but still lack the power and opportunities to deliver services (OECD Citation2022) and influence policy-making beyond information sharing through consultations (Novak and Fink-Hafner Citation2019; Petak Citation2019). Partnership with interest group organizations is centred around transparency and accountability (consultations) and has yet to improve towards channelling input into concrete policy-making measures.

Strategic planning in the Croatian and Slovenian local governments

Strategic planning is widely spoken of in local government but needs to be implemented and better understood in the case of Central and Eastern European local authorities (Kwon et al. Citation2014; Poister and Streib Citation2005; Hințea et al. Citation2019). Strategic planning is assumed to work well in stable and decentralized environments (Bryson et al. Citation2015), which local authorities in post-communist countries tend not to be due to political volatility and income dependency on the central state level (Barati-Stec Citation2019).

The Croatian and Slovenian governments have implemented laws that mandate a planned and strategic approach to regional development following the principles of partnership and multi-annual programming introduced to manage EU-funded programmes.Footnote1 Regional development strategies have been adopted at the national level and it is not unusual for local authorities to develop development plans (some of these plans, such as spatial plans are mandated through law). However, strategies and plans are slowly implemented indicating that there are various obstacles in the strategic planning abilities of municipalities (e.g., Cepuš et al. Citation2019; Istenič and Zrnić Citation2022).

EU accession and membership has contributed to the quality of the planning capacity through the programming principle in Cohesion policy which requires multi-annual and place-tailored development programmes/strategies (Ferry and McMaster Citation2013; Dąbrowski Citation2014). At the same time, pressure to absorb EU funds, political patronage and the centralized nature of programme implementation poses limits to local authorities’ strategic planning in formulating and implementing plans.

The weak planning capacity at the local level is a long-standing issue for the implementation of reforms in Slovenia and Croatia (Grčić Citation2015; Deželan et al. Citation2014). Both countries exhibit below EU-average strategic planning capacities for supporting decision-making and implementation (BertelsmannStiftung Citation2020). A survey established that less than a fifth of Slovenia’s municipalities have a highly developed managerial capacity in terms of workforce size, the implementation of control activities, the use of information technology systems, the planning of objectives and resource availability (Kukovič and Haček Citation2012). Insufficient strategic planning capacities, including the lack of expertise and unwillingness/inability to develop strategies have also been documented for local government in Croatia (Alibegović Citation2007; Government of the Republic of Croatia Citation2017). This can be problematic as sufficient administrative-professional capacity is linked to an effective start of co-creation and the ability to gain results from strategic planning (Bryson Citation2011).

Strategic planning is deemed important for co-creation because local development plans can be successful only when there is a shared commitment and responsibility over the development priorities for a territory. In this sense strategic planning and co-creation seem unalienable. Summing it up, the main expectation is that strategic planning is important for the implementation of co-creation but that the context in the local government of Croatia and Slovenia might mask its relevance.

Research design

Data collection

The article uses data from an online survey developed in the EU-funded Horizon 2020 research consortium COGOV. The intent of the survey was to explore the different forms of co-creation based on partners and activities. The survey was designed through three rounds of consultations with researchers with expertise in strategic management, public administration and co-creation. The pilot phase tested the content of the questions and answer options by contacting respondents with expert knowledge on the population or representatives of the population. This article is based on a subset of the data on local government units in Croatia and Slovenia.

Data was collected using a common sampling protocol. Efforts were made to cover as much of the population of local government units as possible. A list of senior managers (heads of administration or their deputies) in an executive position, and their contacts was composed by visiting websites of each local government unit. When we could not find data on senior managers, we sent the email to service leads or mayors.Footnote2 The survey was administered in local languages. Since the survey was sent to senior managers, an analysis of their views is provided.

The Croatian local government is composed of 428 municipalities and 127 towns and cities. In Slovenia, there are 212 unitary local government units. The Croatian sample consisted of 485 respondents at the municipality level and 171 respondents at the city level for a total of 656 respondents.Footnote3 In Croatia, we received 97 responses (15% response rate) and 64 were fully completed. In Slovenia, 212 local government units received the survey and 96 responses were received (45% response rate) and 47 were fully complete.

The start of the survey coincided with COVID-19 lockdowns in March 2020. The Slovenian survey was closed in August 2020 after a satisfactory survey response rate was achieved. In Croatia, the survey ran until December 2020. To increase the response rate in both countries, traditional methods such as email reminders and personal appeals were made. In addition, in Croatia, a number of organizations were approached for assistance in the distribution. The survey was advertised on the Association of Cities’ website and opened for new respondents. However, these efforts did not significantly increase the response rate. While the Slovenian survey provided a good response rate, the Croatian survey data is not as optimal. Considering this caveat several statistical checks were performed (described below).

It is difficult to assess the representativeness of the sample and how complete the email lists of respondents were since neither Croatia nor Slovenia publish official lists of people working for local government. However, given the extensive search on the websites of local government units, there is a degree of confidence that the survey included a large share of the population based on which a representative sample could be achieved.

Method of analysis

The analysis consists of descriptive statistics and linear fixed effects regression models. Robust standard errors are reported in the regression tables. The analysis was performed using all the available data and on complete survey responses only (reported in the Appendix). The variance inflation factor was calculated for all models and results suggests that multi-collinearity is not a problem.

Internal scale consistency and reliability were checked for all latent constructs with Cronbach’s α and factor loadings based on a principle component analysis. A Kruskal-Wallis test estimated differences between Slovenia and Croatia for all survey items. These tests revealed small or no difference, giving confidence that Croatia and Slovenia can be treated as examples of similar local government administrative traditions.

Operationalization

Dependent variable: co-creation

Co-creation is measured with the co-creation index that can be interpreted to mean the comprehensiveness of co-creation implementation in terms of the partners involved and the activities that partners perform (Cronbach’s α = 0.85, factor loadings are above 0.50 and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin statistics shows sampling adequacy). The index was inspired by Torfing et. al’s definition distinguishing co-creation on partners and activities, and calculated based on the mean value on two survey questions.Footnote4 In the first question, respondents were asked to determine the extent they involve partners in co-creation, distinguishing between public sector organizations, private sector organizations, voluntary sector organizations, citizens in the role of service users, programme beneficiaries, clients or customers, and citizens in the role of volunteers, non-beneficiaries of programmes or non-users of services. Users and non-users were differentiate to tap into the difference between co-production and co-creation as outlined earlier. In the second question, respondents were asked about the activity in which co-creation partners are involved, distinguishing agenda-setting, policy design, decision-making, implementation and evaluation. Values ranged from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (To a very great extent). The appendix reports the full question-wording.

Independent variable: strategic planning

To measure strategic planning, a scale tapping into the steps necessary for the formulation and implementation of plans was developed. Formal planning involves the development of guidelines, plans, mission statements and other similar strategic documents which provide a course of action and serve as a basis for implementation (Bryson Citation2011). The quality and time that an organization dedicates to preparations increases the odds that formal strategies will be implemented (Mintzberg Citation2000). The survey took into account the design activity through which an organization establishes its fit with the environment through analysis. A formal strategic plan should always be evaluated as this offsets some of the inflexibilities of initial formal strategies (Joyce et al. Citation2014). Therefore, the survey included an item on the continuous evaluation of strategies which pairs planning with incremental learning (Poister et al. Citation2013; Mintzberg Citation2000). Here the survey controlled for the extent that planning consists of adjustments through which organizations ensure that working ways achieve the objectives the organization set in the first place. When developing strategies, organizations also need to take into account the response of those a who will have to implement formally adopted strategies (Elbanna et al. Citation2016). Therefore, a fourth item was included linking planning with implementation, where organizations seek staff agreement or buy-in for strategies. Based on the obtained values, an index measuring formal strategic planning (Strategy) was computed. The measure is statistically reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.77, factor loadings all above 0.69, KMO suggesting sampling adequacy).

Control variables

Managers’ skills, resources and motivation are key to the realization of strategies, as professionals are in charge of implementation (Johanson Citation2009). Even when staff are to some extent involved in the adoption of formal strategies, it does not necessarily mean that they are prepared for implementation. Overall, it is plausible to expect professionals’ preparedness affects co-creation. Therefore, we control for the readiness of professionals. To measure the degree that professionals – the employees in local government who are involved in developing and implementing public services and policies – are prepared to co-create, a scale consisting of four items was used. The scale was evaluated with standard techniques (Cronbach’s α = 0.81; factor loadings all above 0.71) and the index Professionals was computed based on mean values.

The take-up of co-creation requires that governments create a persuasive and attractive environment that rises awareness, facilitates learning and promotes opportunities for co-creation. Where formal institutions such as laws, rules, and frameworks are put in place, they tend to positively affect the introduction of co-creation and other forms of collaborative governance (Bryson et al. Citation2017; Wiktorska-Święcka Citation2018). Therefore, we control for the possibility that co-creation will be more prevalent among local government authorities which feel institutionally supported. Institutional support is measured with a dummy variable (Gov. support), where 72 respondents agreed that government encourages co-creation while 39 either disagreed or felt neutral.

Strategies that work for collaborative governance need to enable relationship-building, mutual trust and a working environment eliciting ideas (Crosby and Bryson Citation2005). Organizations need to adopt an equitable model of ownership, control and decision-making and put aside ‘chain in command’ structures. Leadership becomes collaborative and a property of a group of interacting individuals who work together in multi-actor settings to solve problems. The study controlled for the possibility that local government authorities exhibiting collaborative leadership use co-creation more widely. The extent of collaborative leadership in local authorities is measured with three survey items (see appendix). Based on the items a scale was composed (Cronbach’s α = 0.82; factor loadings all above 79) and the index Coll. lead. computed.

Digital is a dummy variable distinguishing respondents that (strongly) agreed that their organization is at the forefront of using new technology (N = 56) compared to those who disagreed or felt neutral (N = 56). Digital platforms – alongside analogue or traditional physical spaces – help in the implementation of co-creation processes. We control for this as there is an extensive literature on digital era governance crediting technology for innovation.

A further variable is organization size (Org. size), measured as the number of full-time employees that work in the local authority of respondents. Size allows to control for the fact that larger local authorities have more resources and can potentially implement co-creation more easily. Slovenia is a dummy distinguishing Croatian (N = 97) and Slovenian (N = 96) respondents. presents the descriptive statistics for numerical variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Results

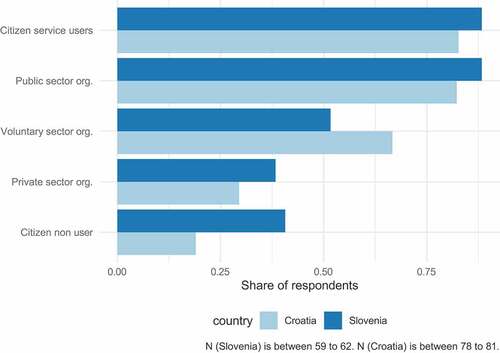

At the start, some descriptive statistics on the dependent variable are presented. presents the variations of partners that local authorities involve in co-creation. There is extensive use of co-creation with citizens in the capacity of service users or programme beneficiaries (co-production) and with public sector organizations. On the other hand, co-creation with citizens that are neither users nor beneficiaries is the least common form of co-creation in Croatia. In Slovenia, co-creation with lay citizens and private sector organizations occurs with similar frequencies. As one might expect, given the role of the voluntary sector and private firms in Slovenia and Croatia, co-creation with them is less extensive than co-creation among public authorities. There are some statistically significant but weak differences between Slovenian and Croatian respondents for the involvement of non-users, public sector organizations and voluntary sector organizations.

Figure 1. Share or respondents reporting that their organization engages with the following partners to a (very) great extent.

When respondents reported that their local authority co-created with organizations in the public sector, they were asked about the territorial level of the public sector organizations they co-create with. More than three quarters of all the respondents (N = 70) reported that their local authority co-creates with public sector organizations across all levels of government (national, regional and local public authorities). Less than ten percent of the respondents reported that their local authority co-creates only across one level of government. Fifteen percent of respondents reported that their local authority co-creates with an organization at some other level of government. These patterns shows that when co-creation is taking place among public sector organizations it transcends territorial levels.

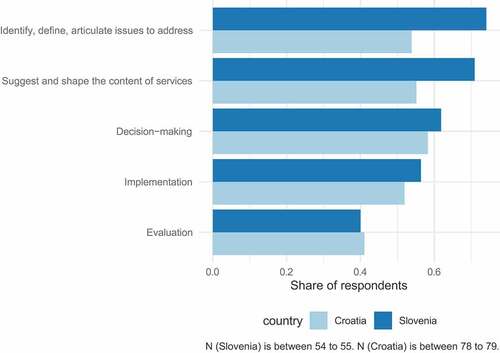

shows that there are multiple activities for which local authorities engage partners in co-creation. Co-creation partners most often take the role of explorers, meaning that local authorities ask partners to identify, define and articulate issues to address (agenda-setting). Another extensively attributed use of co-creation is design, where partners are asked to suggest and shape the content of already existing services, projects, plans and policies. Surprisingly, the use of co-creation to explore new issues is more common than the use of co-creation to improve already existing services (co-production). One conclusion could be that local authorities employ co-creation to deal with unmet needs, but are reluctant to use it for disrupting existing services. Another observation is that according to respondents, local authorities use co-creation more frequently for implementing services, projects, plans and policies than making decisions over services, projects, plans and policies. The least frequent co-creation activity is the evaluation of services, projects, plans and policies.

Figure 2. Share of respondents reporting to engage partners to a (very) great extent in the following co-creation activities.

To contextualize respondents’ self-reported values, the survey asked how the uses of co-creation changed over the last five years. The question was important for contextualizing any reporting bias as it might be that only those respondents where co-creation is already taking place replied to the survey, while respondents where co-creation is not that prevalent opted out. Almost three fifths of all respondents (N = 81) reported that considering the last five years, the use of co-creation in their local authority has increased, with seven percent reporting it decreased (N = 9).

Overall, local government respondents from Croatia and Slovenia reported a frequent and varied use of co-creation in their organizations. In most of the cases co-creation involved service users and other public sector organizations. Co-creation is not restricted to one level of government and there is a clear evidence showing local authorities are increasingly turning to co-creation.

Managing co-creation strategically

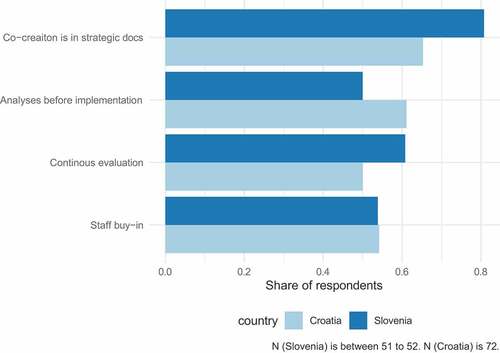

shows that more than three-fifths of all respondents (strongly) agree that co-creation is enshrined in the strategic documents of their local authorities. The performance of analysis before the implementation of co-creation (e.g., assessment of external and internal threats and opportunities, stakeholder analyses and feasibility assessments), seeking and acquiring buy-in from staff and the continued evaluation of co-creation appear on the other hand to be less frequent. These findings are in line with the observation that post-communist countries such as Slovenia and Croatia are fairly advanced in formally adopting new reforms but less committed to implementation through analysis and preparation. No statistically significant differences between Slovenia and Croatia have been detected.

Figure 3. Share of respondents reporting to (strongly) agree with the following statements on strategic planning.

The effect of formal strategic planning on co-creation was tested with a series of linear regression models. estimates the effect of strategic planning on co-creation based on the co-creation index. do the same but by separating co-creation partners and activities in two separate indices. While the dependent variable changes in each table, the effect of strategic planning is tested with the same model set-up:

The first model regresses co-creation on strategic planning while controlling for the mean difference between Croatian and Slovenian respondents.

The second model adds further controls, including the readiness of professionals, collaborative leadership and government support.

The third model includes organizational size differences.

Table 2. Co-creation index (robust std errors).

Table 3. Co-creation partners (robust std errors).

Table 4. Co-creation activities (robust std errors).

shows that strategic planning has a statistical significant effect on the co-creation index at at least the five percent level across all three models. The result is not supported in , where the effects of strategic planning are estimated on the range of partners involved in co-creation. The effect is supported in , where the dependent variable are the activities targeted in co-creation. The logical conclusion is that strategic planning matters for co-creation in term of activities but does not play a role in mobilizing a variety of partners. For the latter, the role of professionals is more important.

Results in show that the readiness of professionals has a consistent and statistically significant effect on the extent of partners and activities involved in co-creation in all models and independently on the measurement of co-creation. Its effect is even stronger than formal strategic planning. The result indicates that the extent professionals feel prepared and resourced for co-creation affects the implementation of co-creation with benefits for the range of partners involved and the activities co-creation is applied to.

Neither gvernment support for co-creation nor collaborative leadership have a consistent statistically significant effect. Similarly, the size of organizations is not statistically significant. Government support was not found to be a determinative factor (at least given our operationalization) in advancing co-creation. The finding can be interpreted as positive since much of the literature refers to the weak autonomy of local government and the necessity of adequate financial and legal frameworks for action at the local level.

Discussion

Overall, the expectations set out in the beginning are largely supported in the data. The implementation of co-creation benefits from a formal strategic planning paired with well-prepared professionals. This finding corroborates research on strategic planning showing that planning and implementation in terms of preparing professionals goes hand in hand (Van Gestel et al. Citation2019; Van Gestel and Grotenbreg Citation2021). Results also show that formal strategic planning is important for planning the activities co-creation is aimed at but does not contribute to the variety of partners a local authority engages with. For the latter, the preparedness of professionals is important. This finding supports the calls for a better understanding of professionals in co-creation (Vrbek and Kuiper Citation2022).

The importance of professionals is also interesting from the perspective of the administrative tradition and its development since the democratic transition in Croatia and Slovenia. During the integration process into the EU, both countries have been motivated to increase their administrative capacity for implementing the common rules and laws of the EU. The findings here reaffirm the continued importance of strengthening administrative capacity. Where professionals are skilled, motivated, resourced and knowledgeable, co- creation can advance. On a practical level, it means that developing administrative capacity should remain an important priority for public administration in Croatia and Slovenia.

Given the common politico-administrative tradition, it is not surprising that Croatia and Slovenia exhibit similar co-creation patterns. The most common partners are citizens in the role of service users and other public sector organizations. Co-creation with voluntary and private sector partners is less common, suggesting that the rise of co-creation is driven through activities between public authorities and citizens as service users. A practical implication of these findings is that to further the potentials of co-creation, local authorities have to take strategic steps in addressing engagement from the private and voluntary sectors. Another implication for studying public administration comparatively is that even with administrative traditions where dialogue and collaboration between different partners and levels of government are not well-embedded in society, co-creation is on the rise.

There are limits to these findings. Strategic planning is a multifaceted phenomenon requiring a more precise measurement, such as a scale with multiple statistically reliable components. The measure used here does not capture the practice component of strategic planning. The measurement of strategic planning probed into the existence of a co-creation strategy without revealing whether the content of such strategies facilitates co-creation, for instance producing greater responsiveness to collaborative ways of working across organizational boundaries. The study has in fact focused on a definition of strategic planning that emphasizes its formality and procedural character. Any future study would benefit from developing items that probe into the exact content of strategies. One way to proceed would be to research the extent strategic planning is helping organizations in establishing trust-based steering systems based on learning and self-evaluations, a culture of experimentation that balances risks and benefits, the use of technology and the promotion of professional cultures that value mediation, dialogue and openness.

Conclusion

Based on survey data from respondents in local government authorities in Croatia and Slovenia, the article tested the importance of formal strategic planning to implement co- creation. Regression analysis showed that formal strategy planning, including mission statements and staff buy-in, increases the adoption of co-creation. These findings imply that the consolidation of strategic planning in Croatia and Slovenia is likely to increase the use of co-creation and its potential benefits. The preparedness and beliefs of professionals affect the prevalence of co-creation and appear to be even more important than formal strategic planning. Considering similar features in the Croatian and Slovenian local government, a common post-communist administrative tradition limiting the applicability of co-creation was assumed. Yet, findings show that even in an environment where dialogue and collaboration between different partners and levels of government need to be better embedded in society – as is the case in Slovenia and Croatia – co-creation is on the rise.

The survey explored what single organizations can do to adopt and make co-creation work. Future quantitative research could map existing co-creation processes and research the collaborative strategic efforts, namely what degree of strategic planning is adopted before and during a co-creation process between partners. This kind of research should put more emphasis on strategy as a co-created activity where relationship building and the discursive element of planning should be given attention beyond formal planning.

Co-creation was operationalized to emphasize the ability of local government to partner up across sectors, levels of government and with citizens. To nuance co-creation further, the research took into account different activities in which partners can be engaged in (agenda setting, problem solving, implementation, evaluation, etc.). Future research should focus on the outputs and outcomes of co-creation by exploring public values such as efficiency vs. efficacy, cost vs. gain (i.e., cost for resources vs satisfaction levels) and intended vs. unintended consequences.

Acknowledgement

I acknowledge the contribution of the Faculty of Public Administration, University of Ljubljana that implemented the survey in Slovenia and other COGOV partners who provided feedback and comments (Aix-Marseille University, Cardiff University, City of Rijeka King’s Business School, Northumbria University, Open University, Roskilde University, TIAS Business School).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andreja Pegan

Andreja Pegan is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Management of the University of Primorska, Koper (Slovenia). She researchers the representative institutions in the European Union, the democratic qualities of policy-making and new public governance. Research for this article was conducted while she was a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Northumbria at Newcastle (UK).

Notes

1. These laws are the Promotion of Balanced Regional Development Act (2011) in Slovenia and Law on Regional Development (2019) in Croatia.

2. The data shows that the sample includes 59 senior managers, 41 middle managers and 11 junior managers.

3. The number of respondents is larger than the number of Croatian municipalities because when a response was not received after three reminders, another municipality respondent was identified and included in the sample.

4. Only complete responses were used with no imputing for missing values.

References

- Alibegović, D. J. 2007. Strateško planiranje i programski proračun: Put do pazvojnih rezultata na lokalnoj i regionalnoj razini?” [Strategic planning and program budget: the path to development results at the local and regional level?] Hrvatska Javna Uprava 2: 395–420.

- Alibegović, D.J., S. Slijepčević, and Ž. Kordej-De Villa. 2013. Can local governments in Croatia cope with more responsibilities? Lex Localis-Journal of Local Self-Government 11, no. 3: 471–95. doi:10.4335/11.3.471-495(2013).

- Andreou, G., and I. Bache. 2010. Europeanization and multi-level governance in Slovenia. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10, no. 1: 29–43. doi:10.1080/14683851003606861.

- Ansell, C., E. Sørensen, and J. Torfing. 2020. The covid-19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? The need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Public Management Review 42, no. 2: 124–28. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272.

- Ansell, C., E. Sørrensen, and J. Torfing. 2022. Co-creation for sustainability: The UN SDGs and the power of local partnerships. Bingley: Emerald.

- Ansoff, H.I. 1980. Strategic Issue Management. Strategic Management Journal 1, no. 2: 131–48. doi:10.1002/smj.4250010204.

- Bache, I., G. Andreou, G. Atanasova, and D. Tomšić. 2011. Europeanization and multi-level governance in South-East Europe: The domestic impact of EU Cohesion policy and pre-accession aid. Journal of European Public Policy 18, no. 1: 122–41. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.520884.

- Bache, I., and D. Tomšić. 2010. Europeanization and nascent multi-level governance in Croatia. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10, no. 1: 71–83. doi:10.1080/14683851003606770.

- Baptista, N., H. Alves, and N. Matos. 2020. Public sector organizations and cocreation with citizens: A literature review on benefits, drivers, and barriers. Journal of Nonprofit Public Sector & Marketing 32, no. 3: 217–41. doi:10.1080/10495142.2019.1589623.

- Barati-Stec, I. 2019. Strategic planning in post-communist settings: The examples of Hungary. In Strategic Planning in Local Communities. A Cross-National Study of 7 Countries, ed. C.E. Hințea, M.C. Profiroiu, and T.C. Țiclău, 45–70. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- BertelsmannStiftung. 2020. Strategic capacity report. Sustainable governance indicators. https://www.sgi-network.org/docs/2020/thematic/SGI2020StrategicCapacity.pdf/7D.

- Börzel, T.A. 2010. Why you don’t always get what you want: EU enlargement and civil society in Central and Eastern Europe. Acta Politica 45, no. 1–2: 1–10. doi:10.1057/ap.2010.1.

- Börzel, T.A., and A. Buzogány. 2010. Governing EU accession in transition countries: The role of non-state actors. Acta Politica 45, no. 1: 158–82. doi:10.1057/ap.2009.26.

- Bovaird, T., S. Flemig, E. Loeffer, and S.P. Osborne. 2017. Debate: Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes. Public Money & Management 37, no. 5: 363–64. doi:10.1080/09540962.2017.1294866.

- Bovaird, T., and E. Loeffer. 2012. From engagement to co-production: The contribution of users and communities to outcomes and public value. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 23, no. 4: 1119–38. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9309-6.

- Brown, K., and S. Osborne. 2012. Managing Change and Innovation in Public Service Organizations. London; New York: Routledge.

- Bryson, J.M. 2011. Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Bryson, J.M., B.C. Crosby, and J.K. Bryson. 2009. Understanding strategic planning and the formulation and implementation of strategic plans as a way of knowing: The contributions of actor-network theory. International Public Management Journal 12, no. 2: 172–207. doi:10.1080/10967490902873473.

- Bryson, J.M., B.C. Crosby, and M.M. Stone. 2015. Designing and implementing cross-sector collaborations: Needed and challenging. Public Administration Review 75, no. 5: 647–63. doi:10.1111/puar.12432.

- Bryson, J., A. Sancino, J. Benington, and E. Sørensen. 2017. Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Management Review 19, no. 5: 640–54. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1192164.

- Cepuš, S., K. Strmšnik, M. Harmel, A. Krajnc, M. Premelč, E. Harmel, and S. Weldt. 2019. The Effectiveness of the SEA Process in Slovenia. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 37, no. 3–4: 312–26. doi:10.1080/14615517.2019.1595934.

- Council of Europe. 2011. Local and regional democracy in Croatia. https://rm.coe.int/1680718c83%7D.

- Council of Europe. 2016. Local and regional democracy in Slovenia. https://search.coe.int/congress/Pages/resultdetails.aspx?ObjectId=0900001680718dbe/7D.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Additional protocol to the European charter of local self-government on the right to participate in the affairs of a local authority. https://rm.coe.int/european-charter-for-local-self-government-english-version-pdf-a6-59-p/16807198a3/7D

- Crosby, C.B., and J.M. Bryson. 2005. A leadership framework for cross-sector collaboration. Public Management Review 7, no. 2: 177–201. doi:10.1080/14719030500090519.

- Dąbrowski, M. 2014. Towards place-based regional and local development strategies in central and Eastern Europe? EU cohesion policy and strategic planning capacity at the sub-national level. Local Economy 29, no. 4–5: 378–93. doi:10.1177/0269094214535715.

- Demidov, A. 2017. Europeanisation of interest intermediation in the Central and Eastern European member states: Contours of a mixed model. East European Politics 33, no. 2: 233–52. doi:10.1080/21599165.2017.1300145.

- Desmidt, S., and K. Meyfroodt. 2018. Debate: unravelling strategic planning effectiveness? What about strategic consensus? Public Money & Management 38, no. 4: 255–56. doi:10.1080/09540962.2018.1449456.

- Deželan, T., A. Maksuti, and M. Uršič. 2014. Capacity of local development planning in Slovenia: Strengths and weaknesses of local sustainable development strategies. Lex Localis-Journal of Local Self-Government 12, no. 3: 547–73. doi:10.4335/12.3.547-573(2014).

- Elbanna, S., R. Andrews, and R. Pollanen. 2016. Strategic planning and implementation success in public service organizations: evidence from Canada. Public Management Review 18, no. 7: 7. doi:10.1080/14719037.2015.1051576.

- European Commission. 2014. Delegated Regulation (EU) No 240/2014. 7 January 2014 On the European Code of Conduct on Partnership in the Framework of the European Structural and Investment Funds. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/93c4192d-aa07-43f6-b78e-f1d236b54cb8

- European Commission. 2016. Implementation of the Partnership principle and multi-level governance in 2014-2020 ESI funds. https://ec.europa.eu/regionalpolicy/sources/policy/how/studiesintegration/implpartnerreporten.pdf.

- Ferlie, E. 2021. Concluding discussion: key themes in the (possible) move to co-production and co-creation in public management. Policy & Politics 49, no. 2: 305–17. doi:10.1332/030557321X16129852287751.

- Ferlie, E., and E. Ongaro. 2015. Strategic management in public services organizations: Concepts, schools and contemporary issues. First ed. London; New York: Routledge.

- Ferry, M., and I. McMaster. 2013. Cohesion policy and the evolution of regional policy in Central and Eastern Europe. Europe-Asia Studies 65, no. 8: 1502–28. doi:10.1080/09668136.2013.832969.

- Fiedler, K., D. Ložar, M. Primc, and K. Babič. 2020. Participativni proračun v Sloveniji [Participatory budgeting in Slovenia]. https://skupnostobcin.si/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/3_raziskava_participativni-proracun.pdf.

- Fledderus, J., T. Brandsen, and M. Honingh. 2014. Restoring trust through the co- production of public services: a theoretical elaboration. Public Management Review 16, no. 3: 424–43. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.848920.

- Fotaki, M. 2011. Towards developing new partnerships in public services: users as consumers citizens and/or co-producers in health and social care in England and Sweden. Public Administration 89, no. 3: 933–55. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01879.x.

- Government of the Republic of Croatia. 2017. Strategija regionalnog razvoja Republike Hrvatske za razdoblje do kraja 2020 [Regional development strategy of the Republic of Croatia for the period until the end of 2020]. https://razvoj.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/O%20ministarstvu/Regionalni%20razvoj/razvojne%20strategije/Strategija%20regionalnog%20razvoja%20Republike%20Hrvatske%20za%20razdoblje%20do%20kraja%202020._HS.pdf%7D.

- Grafenauer, B., and M. Klarić. 2011. Alternative service delivery arrangements at the municipal level in Slovenia and Croatia. Lex Localis - Journal of Local Self- Government 1, no. 1: 67–83. doi:10.4335/9.1.67-83.

- Grčić, F.M. 2015. Menadžerske inovacije u funkciji razvoja učinkovitosti lokalne samouprave u Republici Hrvatskoj Managerial Innovations in the Function of Developing the Efficiency of Local Self-Government in the Republic of Croatia]. Rijeka: University of Rijeka.

- Heinelt, H., N.K. Hlepas, and A. Magnier. 2006. Typologies of Local Government System. In The European mayor: political leaders in the changing context of local democracy, ed. H. Bäck, H. Heinelt, and A. Magnier, 21–42. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Hințea, C.E., M.C. Profiroiu, and T.C. Țiclău. 2019. Transnational Perspectives on Strategic Planning in Local Communities. In Strategic Planning in Local Communities. A Cross-National Study of 7 Countries, ed. C.E. Hințea, M.C. Profiroiu, and T.C. Țiclău, 241–50. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hrovatin, N. 2010. Public-private partnerships in Slovenia: reverse financial innovations enhancing the public role. In Innovations in Financing Public Services, ed. B. Stephen, V. Pekka, and A.-V. Anttiroiko, 87–113. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Istenič, S.P., and V.G. Zrnić. 2022. Visions of cities’ futures: a comparative analysis of strategic urban planning in Slovenian and Croatian cities. Urbani Izziv 33, no. 1: 122–33. doi:10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2022-33-01-05.

- Jacobsen, D.I., and Å. Johnsen. 2020. Alignment of Strategy and Structure in Local Government. Public Money & Management 40, no. 4: 276–84. doi:10.1080/09540962.2020.1715093.

- Johanson, J.-E. 2009. Strategy Formation in Public Agencies. Public Administration 87, no. 4: 872–91. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01767.x.

- Johnsen, Å. 2019. Does formal strategic planning matter? An analysis of strategic management and perceived usefulness in norwegian municipalities. International Review of Administrative Sciences 87, no. 2: 380–98. doi:10.1177/0020852319867128.

- Joyce, P., J.M. Bryson, and M. Holzer. 2014. Introduction. In Developments in strategic and public management studies in the US and Europe, ed. P. Joyce, J.M. Bryson, and M. Holzer, 1–20. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jukić, T., I. Pluchinotta, R. Hržica, and S. Vrbek. 2021. Organizational maturity for co-creation: towards a multi-attribute decision support model for public organizations. Government Information Quarterly 39, no. 1: 101–623. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2021.101623.

- Koprić, I., M. Škarica, and B. Milošević (Eds.). 2015. Cooperation and development in local and regional self-government. Zagreb: Institute for Public Administration.

- Kuhlmann, S., and H. Wollmann. 2019. Introduction to Comparative public administration: administrative systems and reforms in Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kukovič, S., and M. Haček. 2012. “Analiza raziskave upravljavske sposobnosti slovenskih občin” [Research analysis on the management ability of Slovenian municipalities]. In Upravljavska sposobnost slovenskih občn: Primeri dobrih praks [The administrative capacity of Slovenian municipalities: Examples of good practices], ed. M. Haček, 89–112. Ljubljana, Zagreb: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung in Fakulteta za družbene vede.

- Kukovič, S., M. Haček, and A. Bukovnik. 2016. The issue of local autonomy in the slovenian local government system. Lex Localis - Journal of Local Self-Government 14, no. 3: 303–20. doi:10.4335/14.3.303-320(2016).

- Kwon, M., F.S. Berry, and J.H. Soun. 2014. To use or not to use strategic planning: factors city leaders consider to make this choice. In Developments in Strategic and Public Management Studies in the US and Europe, ed. P. Joyce, J.M. Bryson, and M. Holzer, 163–78. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Metaxas, T., and E. Preza. 2015. Public-private partnerships in Southeastern Europe: Croatia. International Journal of Public Policy 11, no. 1–3: 86–109. doi:10.1504/IJPP.2015.068845.

- Mintzberg, H. 2000. The rise and fall of strategic planning. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Nabatchi, T., A. Sancino, and M. Sicilia. 2017. Varieties of Participation in Public services: the who, when, and what of coproduction. Public Administration Review 77, no. 5: 766–76. doi:10.1111/puar.12765.

- Nambisan, S., and P. Nambisan. 2013. Engaging Citizens in Co-Creation in Public Services. IBM Center for The Business of Government.

- Novak, M., and D. Fink-Hafner. 2019. Slovenia: Interest group developments in a postsocialist-liberal democracy. Journal of Public Affairs 19, no. 2: e1867. doi:10.1002/pa.1867.

- OECD. 2017. Recommendation of the Council on Open Government. Adopted on 14 December 2017. https://www.oecd.org/gov/Recommendation-Open-Government.

- OECD. 2022. Boosting social entrepreneurship and social enterprise development in Slovenia. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/publications/boosting-social-entrepreneurship-and-social-enterprise-development-in-slovenia-8ea2b761-en.html

- Ongaro, E., and W. Kickert. 2020. EU-Driven Public Sector Reforms. Public Policy and Administration 35, no. 2: 117–34. doi:10.1177/0952076719827624.

- Ongaro, E., C. Mititelu, and A. Sancino. 2021a. A strategic management approach to co-commissioning public services. In The Palgrave Handbook of Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes, ed. E. Loeffer and T. Bovaird, 2265–84. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ongaro, E., A. Sancino, I. Pluchinotta, H. Williams, M. Kitchener, and E. Ferlie. 2021b. Strategic management as an enabler of co-creation in public services. Policy & Politics 49, no. 2: 287–304. doi:10.1332/030557321X16119271520306.

- Osborne, P.S., and K. Strokosch. 2013. It takes two to tango? understanding the co-production of public services by integrating the services management and public administration perspectives. British Journal of Management 24: S31–47. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12010.

- Parrado, S., G.G.V. Ryzin, T. Bovaird, and E. Löffer. 2013. Correlates of co-production: Evidence from a five-nation survey of citizens. International Public Management Journal 16, no. 1: 85–112. doi:10.1080/10967494.2013.796260.

- Petak, Z. 2019. Policy-Making Context and Challanges of Governance in Croatia. In Policy-Making at the European Periphery: The Case of Croatia, ed. Z. Petak and K. Kotarski, 20–45. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Poister, T.H., L.H. Edwards, O.Q. Pasha, and J. Edwards. 2013. Strategy formulation and performance: evidence from local public transit agencies. Public Performance & Management Review 36, no. 4: 585–615. doi:10.2753/PMR1530-9576360405.

- Poister, T.H., and G. Streib. 2005. Elements of strategic planning and management in municipal government: status after two decades. Public Administration Review 65, no. 1: 45–56. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00429.x.

- Rakar, I., B. Tičar, and M. Klun. 2015. Inter-Municipal Cooperation: Challenges in Europe and in Slovenia. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 11, no. 45: 185–200.

- Scognamiglio, F., A. Sancino, F. Calo, C. Jacklin-Jarvis, and J. Rees. 2022. The public sector and co-creation in turbulent times: a systematic literature review on robust governance in the covid-19 emergency. Public Administration. doi:10.1111/padm.12875.

- Sicilia, M., A. Sancino, T. Nabatchi, and E. Guarini. 2019. Facilitating co-production in public services: management implications from a systematic literature review. Public Money & Management 39, no. 4: 233–40. doi:10.1080/09540962.2019.1592904.

- Škrbec, J., and B. Dobovšek. 2013. Corruption Capture of Local Self-Governments in Slovenia. Lex Localis-Journal of Local Self-Government 1, no. 13: 615–30. doi:10.4335/11.3.615-630(2013).

- Sørensen, E., and T. Bentzen. 2020. Public Administrators in Interactive Democracy: A Multi-Paradigmatic Approach. Local Government Studies 46, no. 1: 139–62. doi:10.1080/03003930.2019.1627335.

- Sorrentino, M., M. Sicilia, and M. Howlett. 2018. Understanding Co-Production as a New Public Governance Tool. Policy and Society 37, no. 3: 277–93. doi:10.1080/14494035.2018.1521676.

- Švaljek, S., I. Rakarić Bakarić, and M. Sumpor. 2019. Citizens and the City: The Case for Participatory Budgeting in the City of Zagreb. Public Sector Economics 43, no. 1: 21–48. doi:10.3326/pse.43.1.4.

- Torfing, J. 2016. Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector. Washington DC: George-town University Press.

- Torfing, J., E. Ewan Ferlie, T. Jukić, and E. Ongaro. 2021. A Theoretical Framework for Studying the Co-Creation of Innovative Solutions and Public Value. Policy & Politics 49, no. 2: 189–209. doi:10.1332/030557321X16108172803520.

- Torfing, J., E. Sørrensen, and A. Røiseland. 2019. Transforming the public sector into an arena for co-creation: barriers, drivers, benefits, and ways forward. Administration & Society 51, no. 5: 795–825. doi:10.1177/0095399716680057.

- UN Habitat. 2009. International guidelines on decentralization and access to basic services for all. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme. https://unhabitat.org/international-guidelines-on-decentralization-and-access-to-basic-services-for-all

- United Nations. 2019. Sustainable development goal 16: focus on public institutions. World Public Sector Report https://publicadministration.un.org/publications/content/PDFs/World

- Van Gestel, N., and S. Grotenbreg. 2021. Collaborative Governance and innovation in public services settings. Policy & Politics 49, no. 2: 249–65. doi:10.1332/030557321X16123785900606.

- Van Gestel, N., and M. Kuiper. 2022. Strategies and transitions to public sector co-creation across Europe. Paper Presented at the 38th Egos Conference, Vienna, 7-9 July.

- Van Gestel, N., M. Kuiper, and W. Hendrikx. 2019. Changed roles and strategies of professionals in the (co)production of public services. Administrative Sciences 9, no. 3: 59. doi:10.3390/admsci9030059.

- Voorberg, W.H., V.J.J.M. Bekkers, and L.G. Tummers. 2015. A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review 17, no. 9: 1333–57. doi:10.1080/14719037.2014.930505.

- Vrbek, S., and M. Kuiper. 2022. Command, control and co-creation: drivers and barriers faced by professionals co-creating in the Slovenian public sector. Central European Public Administration Review 20, no. 1: 33–56. doi:10.17573/cepar.2022.1.02.

- Vukovič, V. 2017. The political economy of local government in Croatia: Winning coalitions, corruption, and taxes. Public Sector Economics 41, no. 4: 387–420. doi:10.3326/pse.41.4.1.

- Walker, R.M., and R. Andrews. 2015. Local government management and performance: A review of evidence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25, no. 1: 101–33. doi:10.1093/jopart/mut038.

- Wiktorska-Święcka. 2018. Co-creation of public services in Poland in statu nascendi. A case study on senior co-housing policy at the urban level. Polish Political Science Review 6, no. 2: 26–54. doi:10.2478/ppsr-2018-0012.

Appendix

1.1 Regression models

The following models in are based on a smaller sample, where only the responses of the respondents who answered all the questions (i.e. no missing value) in the survey were used. The regressions models are the same as the ones reported in the article. The regression results presented in the tables below serve as robustness checks. The results do not vary compared to the model reported in the article.

Table A1. Co-creation index (robust std errors).

Table A2. Co-creation partners (robust std errors).

Table A3. Co-creation activities (robust std errors).

1.2 Survey questions and items

1.2.1 Co-creation

To what extent does your organization engage in co-creation with the following partners?

Response options: Not at all, To a little extent, To a moderate extent, To a great extent, To a very great extent, I don’t know

• Citizens in the role of service users, programme beneficiaries, clients or customers

• Citizens in the role of volunteers, non- beneficiaries of programmes or non-users of services

• Public sector organisations

• Voluntary sector organisations

• Private sector organisations

To what extent does your organization engage in co-creation with stakeholders in the following activities?

Response options: Not at all, To a little extent, To a moderate extent, To a great extent, To a very great extent, I don’t know

• To identify, define and articulate issues to address (agenda-setting)

• To suggest and shape the content of services, projects, plans and policies (design)

• To make decisions over services, projects, plans and policies (decision-making)

• To implement services, projects, plans and policies (implementation)

• To evaluate services, projects, plans and policies (evaluation)

The following definition of co-creation was provided to respondents: Co-creation is a collaborative process through which public sector organizations attempt to transform how complex problems, challenges or tasks are met by working together with one or more partners in the private, public or voluntary sector and citizens. The core objective of co-creation is to move from consulting with partners to co-creating services and policies with them. This can include co-creation in terms of the design, production, planning, implementation, delivery, and evaluation of services and policies. You might be familiar with co-creation under the labels of co-production, co-design, co-delivery and co-evaluation. In this study, these are understood to be forms of co-creation.

1.2.2 Strategic planning

To what extent do you agree with the following statements on the strategic planning processes for implementing co-creation in your organization?

Response options: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly agree, I don’t know

• Co-creation is enshrined in the strategic plans of my organization (e.g. vision statements, organizational missions, action plans and strategies).

• My organization undertakes analyses before implementing co-creation (e.g. assessment of external and internal threats and opportunities, stakeholder analyses and feasibility assessments).

• My organization continuously evaluates, monitors, and updates its strategic plans involving co-creation as new information becomes available.

• My organization has effectively achieved staff buy-in for co-creation.

1.2.3 Professionals

To what extent do you agree with the following statements on professionals?

Response options: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly agree, I don’t know

• Professionals in my organization have the skills to co-create with stakeholders;

• Professionals in my organization have a clear understanding of what they need to do in co-creation;

• Professionals in my organization believe that co-creation with stakeholders improves their ability to solve problems.

• Professionals in my organization are easily motivated to co-create with stakeholders.

A fifth item ‘Professionals in my organization have a clear understanding of what they need to do in co-creation.’ was included in the survey, but excluded from the professionals scale, as its removal increased Cronbach’s alpha and the item did not load strongly with the other items in the principal component analysis. Respondents were provided with the following definition of professionals: Professionals in the public sector are public servants in ministries or local and regional government, as well as employees in government agencies, as long as they are affected by, or involved in developing and implementing public services and policies.

1.2.4 Collaborative leadership

To what extent do you agree with the following statements?

Response options: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly agree, I don’t know

In my organization, it is common that individuals with different skills and knowledge come together to complete a particular task.

In my organization, individuals balance each other’s skill gaps.

In my organization, it is less about heroic leaders and more about leadership as a collaborative endeavour.