?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

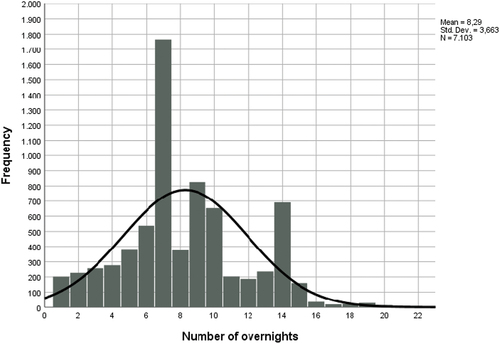

This empirical case study aims to illuminate the specific Yugoslav model of domestic social tourism and the related social responsibility of corporations and the public sector invested in their holiday accommodations managed by trade unions. TwoStep cluster analysis and cross-tabulation, overlooked in historical studies, were also used to analyse 7,178 guests over a 10-year period. The results show that guests spent an average of 8.29 days in holiday homes and that this was not associated with employment status. Moreover, guests can be divided into two statistically different clusters: Employed and Non-employed guests. The fact that low-ranking workers, assistants and the non-employed also had the opportunity to go on a summer holiday points to the social responsibility of employers in the 1950s and 1960s. Nevertheless, they were operating under challenging socioeconomic (non-democratic) circumstances.

Introduction

All authoritarian regimes in Europe in the 20th century exploited tourism as a tool for the affirmation and promotion of their ideologies, creating and maintaining peoples’ loyalty and building the cult of the state or emperor (Kavrečič Citation2020).Footnote1 For example, the communist regime of the former Soviet Union (USSR) ‘intended to produce physically and ideologically healthy Soviet citizens’ (Gorsuch Citation2003, 761). Especially during the last period of Stalin’s rule, it was not recommended for USSR citizens to travel abroad since foreign countries, especially in the West, were perceived as enemies. Similar views and approaches in the post-WWII period can be found in other Eastern European countries, with the exception of the somewhat more ‘liberal’ Yugoslavia (Hall Citation1984; Horna, Citation1988; Banaszkiewicz et al. Citation2017; Slocum and Klitsounova Citation2020), where a more benevolent attitude towards Westernization and commercialization was observed (Calic Citation2019, 206). In socialist Yugoslavia, tourism was important for ideological and economic reasons; the state distanced itself from the USSR and the Eastern Bloc, introduced liberties, including open borders for domestic and international travellers, and had a higher standard of living (Hall Citation1984; Tchoukarine Citation2010, Citation2015; Kukić, Citation2018).

The present empirical case study focuses on a rather contentious area of the Upper Adriatic, which from 1954 to 1991 administratively belonged to socialist Yugoslavia, and from 1991 onwards to the Republic of Slovenia, one of its successors (see ). Due to its attractive natural resources such as climate, salt and thermal water, as well as cultural and historical sights, it has been internationally recognized since the time of the Habsburg Monarchy (Kavrečič Citation2017, Šuligoj, Citation2015). Tourism in this period was primarily associated with health services (health tourism) and elitism (Kavrečič Citation2017, Šuligoj, Citation2015, Citation2020, Kranjčević Citation2019). Grado, Opatija, the Brioni islands, Lovran, and Portorož were the most prominent localities with a gradually developed accommodation sector. The area was in the post-WWII period further affected by the Italian-Yugoslav border dispute and the change in the socio-political system (Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021). The latter caused a shift from elite to socially coloured tourism, with domestic workers at the forefront.

Figure 1. Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Accordingly, this article aims to illuminate the specific Yugoslav model of domestic tourism focused on the working class, a pillar of the then-socialist society. Previous research (e.g., Repe Citation1996, Taylor and Grandits, Citation2010, Tchoukarine Citation2015, Duda Citation2015, Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021) has addressed mainly the socio-political and economic aspects of the development of Yugoslav tourism. Comprehensive empirical analysis, on the other hand, has not been provided to complement the existing historiographical knowledge. This empirical case study on Portorož (Municipality of Piran), a recognizable tourist area at the time, focusing on the early period of Yugoslav socialism (the 1950s and 1960s), specific accommodation facilities and characteristics of domestic tourists, attempts to reduce this gap. Consequently, the aim is linked to corporate social responsibility, defined by Bowen (Citation1953) and social tourism by Hunziker (Citation1951, Citation1957). This reflects the complexity and interdisciplinarity of tourism (Graff Citation2016). The study also follows Kavrečič and Šuligoj’s (Citation2021) suggestion for further research on tourism in Portorož during the socialist era.

Tourism in the service of socialist regimes

In the post-WWII period, tourism was subject to the processes of popularization and massification. The changed social, political and economic situation also enabled the differentiation of tourist supply and, with that, accessibility even for the less privileged citizens. In the USSR, the ‘principal socialist state’ conceived tourism as a means of reinforcing the Soviet identity and the creation of a correct understanding of the ‘socialist homeland’ (Gorsuch Citation2003, 761). In addition to trade union members, according to the Soviet regime’s philosophy, some vulnerable social groups also deserved holidays. The socialist regime did not forget to remind the workers of their good luck and the given rights provided by the state. However, during the first post-WWII years, only some workers, ‘the best and most respected members of the nation’s coal mining industry,’ were able to enjoy holidays (Gorsuch Citation2003, 769).

Other socialist regimes, which consistently followed the Soviet model, adopted specific approaches towards the role of tourism. Ivanov (Citation2009, 18) pointed out that tourism was not only aimed at promoting the Bulgarian coastline, the countryside, mountain resorts, wines, nature parks and historical heritage but also the ‘success of socialism and communism.’ Light and Dumbrăveanu (Citation1999) highlighted the Romanian promotion of domestic tourism. The state promoted social tourism with trade unions, which arranged and provided affordable holidays to destinations such as the Black Sea and medical visits to spas and mountain resorts. Moreover, educational excursions for students and schoolchildren took place, promotion of visits to monuments of historical importance and, of course, ‘contemporary monuments of socialist achievement’ (Light and Dumbrăveanu Citation1999, 901). In contrast, Stefan (Citation2022, 1) presents how the Romanian socialist regime shifted from the political ideology to ‘commercialism and market-driven strategies when promoting Romania as a tourist destination in the “West.”’ She studies the period between the 1960s and the 1980s and asserts that there was a continual shift between using tourism as an ideological tool and a certain pragmatism that was needed to turn socialist Romania into a desirable tourist destination. Other former socialist countries also encouraged and strove for foreign tourism development and promoted destinations such as the Lake Balaton in Hungary or the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria (Stefan Citation2022, 2). Czechoslovakia focused mainly on the domestic market until the 1960s but later opened up to international travellers (Mücke Citation2021, 77–8). Tourism in Albania, on the other hand, was primarily used for national affirmation purposes (Hall Citation1984, 544), where the sector was centralized and monopolized: Albturist was the main service provider and was in charge of both international and domestic tourism. It covered ‘all tourist activities-accommodation, catering, transport, foreign exchange shopping, guides, and contacts with foreign travel organizations’ (Hall Citation1990, 42). However, domestic tourists were also organized through trade unions or pioneer groups (children) (Hall Citation1990, 42). The state did not implement approaches like other socialist states, right the opposite: ‘(…) [Enver Hoxha declared that] … the country was closed to “enemies, spies, hippies and hooligans,” but open to friends (Marxist or non-Marxist), to revolutionaries and progressive democrats, to honest tourists who did not interfere in our affairs. Socialist Albania was not a hotbed of bourgeois degeneration, nor was it dazzled by dollars or roubles’ (Logoreci Citation1977, 209–210, Hall Citation1984, 547). The domestic tourists were accommodated in the party, trade union, and governmental facilities, mainly on the Albanian coast and on the eastern shore of Ohrid Lake (Hall Citation1984, 548–550).

Socialist Yugoslavia, separated from the Eastern Bloc after the Tito-Stalin split, is a notable example. However, after WWII and before Tito – Stalin split in mid-1948, a ‘Soviet-style’ communist political, social and economic regime was established in Yugoslavia, and the Communist Party abolished liberal democracy and the market economy and introduced a planned economy. In 1946, the Law of Nationalization (Zakon o nacionalizaciji zasebnih gospodarskih podjetij [Law on the nationalisation of private enterprises], Citation1946) was issued, which significantly changed the ownership structure of business entities, including those in tourism (Glažar Citation2000, 2). The new socialist administration primarily promoted industrialization and the reconstruction of war-affected infrastructure. Investing in technological development within the process of industrialization was a significant priority. After 1948, a gradual economic reformation started in a climate of difficult relationships with foreign countries, both Western and Eastern (Prinčič Citation1997, 5).

In 1955 President Josip Broz Tito started to support the political faction that demanded a transition from the agenda of accelerated industrialization to a new economic policy that also supported other branches of the economy. In the same year, the resolution for the new economic policy was adopted. The premise was to support the thus-far neglected sectors, including agriculture, commerce, trade, craft, hospitality and the whole tourism industry. Due to the economic crisis of the early 1960s, Yugoslavia partially introduced or developed specific forms of consumer society (Prinčič Citation1997, 7–11). These structural and cultural changes significantly affected the initially ignored tourism sector in the new socialist state (Repe Citation1996, Citation2006, Calic Citation2019).

Gradualist affirmation of tourism in socialist Yugoslavia

In the second half of the 1940s and in the 1950s, tourism was a deprivileged sector. The level of inbound tourism was almost negligible. The lack of tourism infrastructure, unattractive supply, and poor investments were all problems impeding the viability of tourism as a sector. The entry visa requirement was an administrative barrier to the arrival of international tourists, especially those from ideologically different Western democratic countries (Repe Citation2006, 62).Footnote2 However, the new socialist Yugoslavia initiated the development of domestic tourism and, thus, the construction of tourism infrastructure on its coastline. Authorities and companies started to construct special accommodations suited for them. It should not be neglected that the primary attention was paid to the domestic working class, which was the ‘main player’ of the new socio-political system (see Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021). Tourist accommodation for the domestic elites, as described by Flere and Rutar (Citation2021), was not at the forefront of public discussions and plans.

During the 1960s, tourism, in general, became a priority of the regime (Repe Citation1996, Calic Citation2019). In the second five-year plan (1957–1961), tourism was mentioned in the plan’s section for ‘the improvement of non-commodity international trade’ (Prinčič Citation1997, 49). The general right to annual holiday leave for the population of socialist Yugoslavia encouraged the development of the tourism industry as part of the ‘modern way of life.’ In fact, ‘when Yugoslavia was recreated as a socialist state in 1945, the new leadership defined holidays with pay and recreation for workers as crucial elements of the new state’s social project’ (Taylor and Grandits Citation2010, 3). In this process, the coast along the Adriatic Sea was the centre of leisure tourism activities in the state. This was also facilitated by the growing popularity of seaside summer tourism, which spread worldwide during the second half of the 20th century. With its natural resources, the long Yugoslav coast offered the then-so-popular ‘sea, sun and sand’ (3S tourism). Nevertheless, it should be noted that the northern part of the ‘Yugoslav Adriatic’ was better developed and more recognizable as a tourist destination than the southern part, today’s Dalmatia and Montenegro. Compared to other (already established) Mediterranean tourist destinations, socialist Yugoslavia, due to its lower standard of living, was also more affordable (Kavrečič Citation2017, Šuligoj, Citation2015).

Economic-political changes were also reflected in tourism statistics. Two years after WWII ended, the number of tourists in Yugoslavia had already reached the pre-war numbers, although the nationalities of the tourists had changed completely. Of about 212,000 guests, only 6,720 (3%) were international tourists, 10 times less than in 1938. In 1950, the number of tourists was lower (107,786), but the share of international tourists was slightly higher (5%). In 1953, the percentage of international tourists increased again. Exactly 134,648 (89%) domestic tourists and 16,425 (11%) international ones were registered (Repe Citation2006, 64, 67). The numbers of registered arrivals in the central and eastern parts of Yugoslavia’s most northern republic, Slovenia,Footnote3 were and remain very interesting to researchers and experts. According to Glažar’s (Citation2000) research of the archive collection of the Federal Conferences on Tourism, the following are noteworthy: in 1938, the Drava Banate (province of Slovenia in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1929 to 1941) was visited by 62,946 international guests, but only 3,134 in 1946, and 6,478 in 1947 (Glažar Citation2000, 81). Another comprehensive study on tourism is Kavrečič and Koderman’s (Citation2014, 93) work, based on the data from the Statistical Yearbook of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (Statistički godišnjak Kraljevine Jugoslavije), which indicates a trend of constant growth starting in 1933 with 175,535 tourists and ending in 1938 with 196,864 tourists; in 1939 a decline in the number of tourists was recorded. In 1938, the number of domestic tourists was 136,405, and the number of international tourists was 60,459, mostly from Germany (31,088), Italy (6,039), Czechoslovakia (5,422) and Austria (4,246) (Kavrečič and Koderman Citation2014, 93).Footnote4 Before WWII, international guests represented about 25% of guests. After the war, the number drastically fell to only 1.9% in 1946 and to 3% in 1947 (Glažar Citation2000, 81). As mentioned, disputed territory along the Italian border assigned to Yugoslavia in 1954 was not included in reports and discussions of experts/scholars of tourism conferences organized in the first years after the war.

A report from the conference in the Yugoslavian capital Belgrade in March 1947 primarily concentrated on the issue of international guests. Here are some highlights: (a) visas should be arranged with the help of the Putnik agency with its offices in London, Paris and New York, (b) international guests were only allowed to travel in the state with special permits, (c) a list of tourist destinations for international guests, which included Bled and Rogaška Slatina, Opatija, Crikvenica, Rab, Dubrovnik, Split and some other parts of Yugoslavia, was created, (d) prices for domestic and international guests should be the same (Glažar Citation2000, 76).Footnote5 During the conference of December of the same year (again held in Belgrade), the issue of the selection of facilities for unions, youth and homes for the disabled, as well as holiday colonies, was raised (Glažar Citation2000, 77).

Since the Yugoslav part of the Upper Adriatic () is our focus, we want to point out some related representative figures. In 1941, the tourism industry represented the second most important economic branch, creating around 20% of the national product (GDP) of the coastal region (Rogoznica Citation2014, 74), which today belongs to Slovenia. This number drastically decreased due to WWII and the post-war border dispute/issue between Yugoslavia and Italy. During the Yugoslav People’s Army administration of the FTT’s Zone B, most of the pre-war tourist facilities in the zone were not operating or were used for other purposes (e.g., military, cultural, health, and social institutions). The administration aimed to apply and develop the ‘socialist-style’ tourist supply for the working masses and to reopen accommodation and other facilities. Nonetheless, in 1951, only 542 international guests were registered in Portorož. Most of them stayed at the Palace Hotel. In the same year, 284 international guests were registered in St. Nikolaj in the Ankaran border area. As pointed out by Rogoznica (Citation2005, 407), only a part of the guests came from other European countries or even the USA; the majority came from the nearby Trieste (Italy).

One of the reasons for a post-war change in the structure of tourists and growth is the orientation towards domestic tourism, which includes the construction of holiday homes. This special type of social tourism was oriented towards social groups that had been overlooked in the past, which is completely compatible with its definitions of social tourism by Hunziker (Citation1951, 1, Citation1957, 12); in his latter definition, he explained social tourism as ‘a particular type of tourism characterized by the participation of people with a low income, providing them with special services, recognized as such.’ Various Yugoslav companies and public sector organizations were investors in accommodation facilities intended for their workers (Kavrečič, Citation2020, Jeraj Citation1995). As a result, 19 holiday homes were recorded in Piran in 1955 (Brezovec Citation2015, 122),Footnote6 and in 1962, there were 110 holiday homes in the Municipality of Piran with a total of 3,880 beds (Skupščina občine Piran s Predhodniki, SI PAK PI 36). As previously mentioned, the attitude towards tourism changed in the 1960s, when the state changed its priorities and focused on international commercial tourism (Duda Citation2010, Repe Citation1996, Calic Citation2019). New hotels intended predominantly for international tourists and domestic elites were constructed (e.g., in Portorož). Social/workers and commercial tourism coexisted during the whole period of socialist Yugoslavia. However, all this was not comparable to trends in more developed capitalist states (see Quek Citation2012).

The Yugoslav worker: a pillar of domestic social tourism and society

Soon after the establishment of the new regime in Yugoslavia, important reforms in socio-economic life were introduced. The system’s political doctrine was focused on workers, the pillar of the new social order (Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021), who deserved a reward for their tireless work. In these post-war years, the share of the working population rose slowly, and in 1953 it was only 3% higher than the inactive population. Exactly 45% of the Slovenian population was inactive in 1953, predominantly homemakers (Balkovec Citation2017, Calic Citation2019). Different labour rights were introduced, such as (a) the annual two weeks paid leave in 1946 (Uredba o plačanem letnem dopustu delavcev, namešcencev in uslužbencev [Regulation on paid annual leave for workers and employees], Citation1946, Jeraj Citation1995) with extensions of days in the following decades, and (b) ‘regres’ (annual holiday allowance) in 1965. The new political regime thus significantly emphasized the social role of tourism, which also gained ideological connotations: tourism and leisure should belong to the working people to gather new strength for further work (Duda Citation2010, 34–36; Kavrečič, Citation2020; Rogoznica Citation2014, 76). Even the most recognizable elite tourist destinations, such as Bled in the Slovenian Alps, were introduced in a new context and thus intended for workers (Repe Citation1996, 158). The same applied to the Adriatic centre of Portorož. Hence, ‘paid leave was a constitutional entitlement: employers had to accept it and employees had to take it’ (Duda Citation2010, 34–36). Taking a holiday became a kind of obligation. While enjoying the beauties of the country and the ‘greatness’ of the regime, the worker rested and regained strength for further work and the building of socialism. The new socialist regime meant that workers who could not afford to go on holiday in the past became an important factor in the development of domestic tourism. Paid leave, annual allowance, and affordable accommodations were the main promoters of the accommodation sector development. In fact, until the 1960s, trade unions largely supported and organized tourism services for workers. Affordable accommodations would have been difficult to achieve without rapid prior nationalization (Glažar Citation2000, 78) of private villas and hotels and an adaptation of abandoned houses in the town centres or nearby surroundings. Special prices and discounts for travel to tourist destinations for members of the trade unions were also implemented (Duda Citation2010, 36–38; Repe Citation1996; Rogoznica Citation2014, 76). In practice, this meant direct benefits granted by the Ministry of Finance (Rogoznica Citation2014, 76). Calic (Citation2019, 201) understands this as ‘one of the most important social achievements of workers’ self-management.’ The Yugoslav authorities, especially in the first years after the end of the war, thus distinctly emphasized the social role of tourism and focused on the domestic workers as a pillar of the socialist economy. Accordingly, holiday homes managed by Yugoslav unions (Rosenbaum Citation2015, Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021) were exempted from the austerity measures of the post-war crisis (Odredba o ukrepih za varčevanje s predmeti široke potrošnje [Decree on measures to save consumer goods], Citation1950, Čepič, Citation1999).

The Yugoslav post-WWII changes related to tourism must be illuminated in the context of a broader social, economic, and political transformation. In the frame of the socialist ideology, the process of providing social equality also involved other aspects of life. With the modern Federal Constitution of 1946, women were granted equal rights as men (Calic Citation2019, 204). Consequently, within their newly acquired rights, women actively obtained a better education and employment, which enabled them to earn their own money (regular wages) and to become financially more independent. Women also had the right to paid holidays (Sitar Citation2020, Jeraj Citation1995, Jeraj Citation2003). However, women’s unemployment was a significant socio-economic problem, so many measures were implemented to mitigate it (Balkovec Citation2017, Kukić, Citation2018). Another group that received attention and financial ‘rewards’ for their past work were retirees. Special attention was also given to children, youth, and disabled people. In the frame of the socialist system, a so-called state-socialist welfare system was set up.Footnote7 The Slovenian Republic’s Constitution of 1947 (Ustava Ljudske Republike Slovenije, Citation1947) normatively ensured social security through socio-economic regulation. Social security was tied to work. The state also cared for war victims, disabled people, and their relatives.

In addition to holiday homes, employers provided other types of social gatherings, such as union excursions, social events, cinema, playgrounds for children, urban parks and similar (Vodopivec Citation2014, Citation2015). However, management (especially top management) is neglected in the above explanation, as they usually spend their leisure time differently, away from the masses of workers (e.g., in hotels, in their own secondary homes).Footnote8 Notwithstanding this deviation from principled social equality (see Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021), it should be pointed out that Yugoslav corporations and the public sector were quite socially responsible and thus advanced for the 1950s. Bowen’s (Citation1953) concept of responsibility expresses a fundamental morality, which means ethical behaviour within legal and regulatory environments that is, in fact, the company’s attitude towards society, in general, was thus followed. Moreover, Davis (Citation1960) claims that businessmen/managers have a relevant obligation towards society in terms of economic and human values. The concept thus also covers workers and their quality of life (Bowen Citation1953, Carroll Citation1999, Latapí et al., Citation2019). If this concept was very advanced at the time (Carroll Citation2008), then the same can be said for the Yugoslav practice of corporate and public sector management and its impact on quality of life. This is thus also compatible with the principles of Hunziker’s (Citation1951, 1, Citation1957, 12) social tourism supported by Yugoslav authorities (Rosenbaum Citation2015, 165). All of the above descriptions help to explain the socio-economic context of an undemocratic European country without a free market economy.

In the next sections, with the empirical analysis, we will focus on guests in holiday homes in the Municipality of Piran, one of the internationally well-known (Yugoslav) Upper Adriatic destinations (). As previously mentioned, the new socialist regime was built on the solidarity and equality of all population classes, which was also reflected in the working environment and leisure practices (corporate social responsibility, social tourism). From this, we can conclude that this was also applied in the field of summer holidays, where, however, not only the working population was most likely active. There are still some gaps in knowledge, so we have developed the following research questions:

RQ1:

Who were guests in the holiday homes of domestic corporations and the public sector?

RQ2:

How long did they spend their holidays on average and, is this associated with their employment status?

RQ3:

In how many groups can we classify and describe guests of holiday homes according to their demographic (employment) characteristics?

Data and methods

To study the (workers as domestic) tourists in the Municipality of Piran in the 1950s and 1960s, when all political disputes and the socialist revolution were over, we compiled both primary and secondary sources. First, diverse references were consulted, including various research by historians and websites focused on business entities, legal documents and other socio-economic and historical content. Then, we collected primary data (guest books) in the Piran Unit of the Regional Archives of Koper. According to James and Vincent (Citation2016, 165), guests’ books are ‘tools to reconstruct tourist markets, and also records of commercial evolution, intercultural encounter, discursive practice, cultural evaluation, literary cultures, and book history’ (see also McNee Citation2020, Fyfe and Holdsworth Citation2009). During two months in 2019, we scanned 19 holiday home guest books (SI PAK PI 36), which were all available books for the period under study. The data set thus included 7,178 guests with the following, from the point of view of personal data protection indisputable, demographics (variables): time of arrival, time of departure, gender, nationality, place of residence, and profession. For the purposes of the analysis, we also recorded the owner of the holiday homes (employers) and the year of the book in the database. Due to the heterogeneity of individual entries, it was necessary to form groups for each variable and then place each entry into these groups. We separately calculated the number of nights spent by each guest and then formed time intervals. Missing data as a result of reckless guest registration were a special issue. All this is shown in .

Table 1. The main features of the guests in the database.

Then, we carried out an empirical analysis. In addition to descriptive statistics (including cross-tabulation with Cramer’s V (φc) and Eta Coefficient (η)), TwoStep clustering (using BIC clustering criteria) was done.Footnote9 The latter is based on seven nominal demographics, while η (a method for determining the strength of association) is calculated from the nominal values and not grouped as presented in ; characteristics are mostly related to employment. Afterwards, the φc for the identification of the strength of association between clusters and variables was employed. A p < 0.05 was taken into account. Some authors have already used this approach for classifications in the accommodation sector (e.g., Zabukovec Baruca and Čivre Citation2012, Rittichainuwat Citation2013), while it is less common in socio-economic and tourism/leisure historiography. Its application in quantitative historical research was observed, see, for example, Light and Seaman (Citation1982), Szołtysek and Ogórek (Citation2020), Sesma et al., (Citation2022). Categorical, scale, and interval historical data are appropriate for these methods. Consequently, the effectiveness of the abovementioned analysis methods when using historical data was also checked. For the statistical analysis, SPSS version 24 was used.

Table 3. Clustered guests by demographics.

Characterization of guests in workers’ holiday homes

In relation to RQ1, shows the structure of guests of holiday homes in the 10-year period of their operation. The data from the guest book covers guests employed in the for-profit and public sectors, with 72.5% coming from the for-profit sector. According to the data, the guests were on holiday between April and September, but most were present in the summer season. The data in the table show a considerable diversity of guests who were employed in different economic sectors and lived mostly in cities (63.6%). The dominance of domestic Slovenian guests was expected; however, we did not expect international guests in holiday homes (0.5%) at all (i.e., Czechoslovaks, Austrians, Poles, Soviets, Turks, Dutch, French, Germans, and Danes). This points to the international connections of domestic trade unions within distinct economic sectors, which also managed the holiday homesFootnote10; this clearly shows that the Yugoslav approach was more open and friendly compared to other Eastern European regimes, such as Albania (Hall Citation1984, Citation1990), USSR (Gorsuch Citation2003). Some ambiguities are the ‘others’ (i.e., Italians, Hungarians, Albanians), as they may also have been members of the indigenous national minorities in Yugoslavia.Footnote11

Also, unexpectedly, this form of domestic social tourism was practised by managers (1.1%), although due to their higher social and financial status, they usually used other accommodation facilities. The same can be said for highly skilled workers who were placed in the group ‘workers’, e.g., surveyors, engineers, doctors, and professors. The 27.2% of non-employed guests (i.e., female homemakers, hereafter homemakers, disabled people, pupils/students, retirees), who had, in addition to low-ranking manual workers and assistants, the opportunity to use holiday homes, shows the social responsibility of employers. In this context, they were in accordance with the then-socialist philosophy, although Marx’s and Lenin’s interpretations did not include tourism (Hall Citation1990, 38); it was defined later. Socialist managers and authorities were socially aware and thus acted accordingly to the concept of social responsibility, which was formed in the capitalist USA (Bowen Citation1953, Davis Citation1960, Carroll Citation1999, Latapí et al., Citation2019). In this manner, we can ‘refute’ Carroll’s (Citation1999) arguments that Bowen (Citation1953) was ahead of his time since social responsibility towards workers was well established in socialist Yugoslavia in the 1950s. In accordance with the above explanations on the significance of the working class for a Yugoslav socialist society, also reflects specific holiday practices of workers and other social groups that were systematically supported by authorities (Duda Citation2010); this was the practice, despite the difficult economic (Čepič, Citation1997, Citation1999) and non-democratic socio-political situation, also stained with state violence (Sindbaek Citation2013).

In addition to the socio-economic backgrounds of guests, we were also interested in how long they spent on their holidays on average and whether this is associated with their employment status (RQ2). Guests in holiday homes in the Municipality of Piran spent an average of 8.29 days (); the median is 7.00, and the mode is 7.00 days (). In general, on average, about half of the statutory minimal leave (Uredba o plačanem letnem dopustu delavcev, namešcencev in uslužbencev, Službeni list FNRJ, 56/1946; Jeraj, Citation1995; Duda Citation2010, 34–36) was spent on summer holidays (in holiday homes), where they could also spend their annual holiday allowance. Combining this with previous research by Duda (Citation2010, 34–36), Kavrečič (Citation2020), and Rogoznica (Citation2014, 76), the abovementioned figures confirm the formation of the social and leisure component of domestic tourism, while ideological directed to build loyal and hard-working residents, can be confirmed only indirectly.

We also examined the association between and employment status. Employing crosstab with 6,136 guests included (85.5% of all), we found that η = 0.087 and η2 = 0.00756. This shows that only 0.756% of the variance in the number of overnights is attributed to employment status. This means a completely negligible association between the two variables (RQ2). At first glance, some non-employed guests spent on average a few more days on holidays than the employed did. For example, 52.9% of homemakers and pupils/students spent 8–14 days, while a slight majority of employed spent 1–7 days (see ). However, the η does not confirm this difference. This is also a surprise, as in relation to RQ1, we found a significant proportion of non-employed guests with no formal work obligations to employers. As stated by Šorn (Citation2017, 259), retired workers were also able to benefit from the holiday homes of former employers, but with some limitations: out of the tourist season and only if the holiday home was not already occupied by employed guests. Also, it is very interesting that a neglected social group were unemployed (married) homemakers (Balkovec Citation2017, Čepič, Citation1997, Čepič, Citation1999), which was also detected by the present study; in the database, 15.5% of guests were homemakers (). Summer holidays need to be also understood in the context of family holidays, where individual members may be non-employed, in our case, children (pupils/students) or wives (homemakers). In any case, this is compatible with the socialist doctrine of egalitarianism and inclusiveness (see Hall Citation1990, 38), which Rosenbaum (Citation2015, 170) problematizes in his essay.

Table 2. Days spent on holidays by employment status.

The last issue was the classification/clustering of guests in holiday homes. The cluster quality chart of the TwoStep clustering indicates that the overall model quality is ‘fair.’ As shown in , a two-cluster solution was created, where the large cluster is 2.18 times larger than the smaller one. Employment status and status in the organization have proven to be the most influential (IM) in creating clusters, while settlement of residence and nationality are completely negligibly associated with clusters. Moreover, φc indicates the strength of association between variables and clusters and further confirms the previous finding.

A typical guest type in Cluster 1 is a non-employed female homemaker whose husband/life partner is employed in the construction sector and stays in a holiday home for 8–15 days on average (). Interestingly, this cluster includes all non-employed guests, whose vast majority are females. This confirms the statements from Balkovec (Citation2017, 148) and Calic (Citation2019, 205) on the burning issue of women’s unemployment in Yugoslavia, which was clearly reflected in the field of domestic tourism. This social group also had the opportunity/possibility to go on a summer holiday in conjunction with working husbands/life partners, which likely reduced their social exclusion. As mentioned before, this can be linked to the context of the then-defined corporate social responsibility (Bowen Citation1953) and social tourism (Hunziker, Citation1951, Citation1957). This goes beyond the mere aspect of individual employers and needs to be understood from the perspective of broader socio-economic sensibility and equality in socialist Yugoslavia (Calic Citation2019). In describing this cluster, however, we should not overlook that the guests classified here are related to 11 economic sectors, with construction dominating. Furthermore, the share of tourists who spent an average of 1–7 days on holiday is only slightly less than 50%. However, from the point of view of influence (IM), these two characteristics are not as important.

The following cluster identified as Employed includes all employed guests of holiday homes (Cluster 2, ). Specifically, this includes all trained manual and other workers, as well as assistants. The same applies to various managerial positions, although we did not expect them here (Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021). Nevertheless, this fact can be considered as a development of a better sense of belonging and integration among different (social) groups of workers and managers. Vodopivec (Citation2014, Citation2015, 136) wrote about these tendencies (internal integration, cohesion and solidarity), albeit in a different context (the textile industry). Moreover, it is not necessary that they spent their holiday in the holiday home of their employer, but in the unit of the of his/her partner/husband/wife’s employer. Hence, despite the slight dominance of men (with 52.8%), the gender structure is quite balanced here, which is relevant from the point of view of the Yugoslav equality policy (Calic Citation2019, Sitar Citation2020, Jeraj Citation2003, Citation1995). However, this is heterogeneous and also the largest cluster that includes workers in 11 sectors; workers in the textile industry dominate. This characteristic, as well as others marked by W or N, is less important and can be ignored (). As this cluster also includes lower-ranking workers and assistants, it can also be linked to Bowen’s (Citation1953) corporate social responsibility and Hunziker’s (Citation1951, 1, Citation1957, 12) social tourism. Hence, linking holidays with improved labour rights (Jeraj Citation1995), understanding leave as some kind of obligation for employed people, reward and stimulation for further work (Duda Citation2010, 34–36), significantly emphasized the social role of domestic tourism as well as self-management, as explained by Calic (Citation2019, 201).

Conclusions

In this article, we have provided a new perspective on the Yugoslav model of domestic tourism characteristic of the 1950s and 1960s, a different, more ‘liberal’ model than that of Eastern European countries at the time. With the help of a robust empirical, methodological approach, we now know the heterogeneous structure of guests in holiday homes (RQ1), the average number of nights spent, and its non-association with employment status (RQ2). Moreover, based on the cluster analysis results, we find that in addition to employed, non-employed (i.e., homemakers, disabled, pupils/students, retirees) also represented an important group/cluster of guests in holiday homes (RQ3). This way, we fully achieved the aim of the research, where we also assumed that the researched model of domestic summer tourism is related to corporate social responsibility defined (Bowen Citation1953) and social tourism (Hunziker, Citation1951, Citation1957). The significance of these findings for modern European economic and tourism/leisure historiography can be explained multi-dimensionally.

First, Yugoslav employers, with the support of the socialist authorities, acted on the principles of Bowen’s (Citation1953) social responsibility, despite the difficult (undemocratic) socio-economic circumstances in the state. We have relied only on that part of this concept, which is related to the workforce. In this respect, we found that Yugoslav practices, globally speaking, were advanced in the 1950s and 1960s. Consequently, we can be restrained to the claims of Carroll’s (Citation1999) arguments on Bowen’s concept in the 1950s and its precociousness.

Second, in conjunction with the previous argument, we found that Yugoslav domestic social tourism corresponded to its definitions by Hunziker (Citation1951, Citation1957). Socialist Yugoslavia was one of the important investors in the development of social tourism (Rosenbaum Citation2015, 165) from its beginning. The present empirical case study confirms this, although Rosenbaum (Citation2015, 170) previously expressed some doubts about egalitarianism in this domain. Not to be neglected, the ‘holiday for all’ direction also had an ideological background (Repe Citation1996, Duda Citation2010, Kavrečič and Šuligoj Citation2021, Rogoznica Citation2014), otherwise characteristic of undemocratic regimes of the 20th century in Europe (Kavrečič Citation2020).

Third, the claims of some authors (e.g., Repe Citation1996, Calic Citation2019) that tourism gained importance in the 1960s are found to be not entirely accurate. This applies in particular to inbound tourism and the related foreign money inflow, which was not a Yugoslav peculiarity (Hall Citation1984, Citation1990, Banaszkiewicz et al. Citation2017). Domestic (summer) tourism, an important part of tourism in general, gained importance on the Upper Adriatic coast immediately after WWII (Rogoznica Citation2005, 407), especially after the border issue with Italy was resolved. After the stabilization of the situation, domestic tourism temporarily dominated, as in the more autocratic and closed countries of the Eastern Bloc. Simultaneous post-WWII industrialization and the introduction of socialist ideology created the conditions for the rapid implementation of social tourism, which was inherently associated with corporate social responsibility. Since a growing number of workers needed holidays at affordable prices, social tourism was thus also inherently linked to industrialization. The present empirical study thus complements Rosenbaum’s (Citation2015), Duda’s (Citation2010, Citation2015), and Kavrečič and Šuligoj’s (Citation2021) findings on domestic tourism and the social significance of such tourism. In fact, this empirical research is the first to introduce the Yugoslav model of domestic tourism into Hunziker’s (Citation1951, Citation1957) concept of social tourism, as defined at the time. Moreover, it concretizes/complements Banaszkiewicz, Graburn and Owsianowska’s (Citation2017, 112) and Rosenbaum’s (Citation2015) general claims about the boom of social tourism during socialism in Eastern Europe.

Finally, methodologically speaking, the statistical methods’ effectiveness for processing historical data was checked. By conscientiously following each method’s assumptions (e.g., multinomial distribution for categorical variables, n > 200), the chosen approach proved to be completely appropriate. Consequently, this study also has methodological implications.

One of the main limitations of this empirical case study is that we are considering only one tourism destination, although it is in the more developed part of the Yugoslav Eastern Adriatic. Accordingly, we consider it a representative example in terms of tourism. Moreover, guest books of holiday homes offer a limited set of data, which in turn affects the possibilities of statistical processing (methodological limitations). Hence, social tourism and corporate social responsibility are not discussed in their entire scope and complexity. Accordingly, a multi-contextual and multi-conceptual microhistorical exploration (Szijártó Citation2002) of tourism in a socialist socio-political system(s) or comparatively with capitalism would lead to a better understanding of the phenomenon. We believe that future quantitative and qualitative research will also address these issues.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. Our sincere thanks go to M. I., M. M. and D. M., who have been involved in this project. This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Metod Šuligoj

Metod Šuligoj is an Associate Professor at the Department for Management in Tourism at the Faculty of tourism studies – Turistica, University of Primorska, Slovenia. His area of research relates to dark tourism, special interest tourism and hospitality management. He often blends and bridges theory from a variety of disciplines (e.g. management, different, sociology, geography, history) in order to explain social phenomena in tourism, especially in the Balkan and Upper Adriatic context.

Petra Kavrečič

Petra Kavrečič, Associate Professor, historian, University of Primorska, Faculty of Humanities. Her study field is economic and social history of tourism. She has published a scientific monograph and several scientific articles at home and abroad, co-edited monographs, focusing on the development of modern tourism in today’s western Slovenia and the relation between tourism and political ideology on the case of commemorative practices of WWI battlefields. She has been and is involved in several research projects financed by the Slovene Research Agency. She conducts her research in domestic and foreign archives.

Notes

1. See also Hall (1984), Hall (1990), Rosenbaum (2015), Banaszkiewicz, Graburn and Owsianowska (2017).

2. However, these were not just the weaknesses of socialist Yugoslavia, as Hall (1984) pointed out almost identical problems in Albania.

3. Its Western border and region overall remained problematic until the resolution of the Italian-Yugoslav border issue. This was/is taken into account when displaying statistics.

4. Some inconsistencies were observed between the data of Glažar (2000) and Kavrečič and Koderman (2014). However, both studies clearly show the trend we were primarily interested in. A discussion on inconsistency would go beyond the purpose of this study.

5. Accordingly, Brezovec and Brezovec (2021) discussed tourism promotion of the Yugoslav coast.

6. Exactly 68 holiday homes were planned in Piran in 1958 (Jule, 1958).

7. More can be found in Jeraj (1995) and Balkovec (2017).

8. More on their second homes can be found in Jeršič (1968), Opačić and Koderman (2018).

9. The TwoStep Cluster Analysis is an exploratory technique designed to reveal natural groupings/clusters of categorical and continuous variables that would otherwise not be apparent (Tkaczynski 2017).

10. More can be found in Kavrečič and Šuligoj (2021).

11. Since the section in the guestbook was/is called ‘nationality’ and not ‘citizenship’, this cannot be interpreted with certainly.

References

- Balkovec, B. 2017. “Delavec in delavka se starata” [Male and female workers are getting older.” In Starost – izzivi historičnega raziskovanja, Vpogledi 18, ed. M. Šorn, 143–59. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino.

- Banaszkiewicz, M., N. Graburn, and S. Owsianowska. 2017. Tourism in (Post)socialist Eastern Europe. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 15, no. 2: 109–21. doi:10.1080/14766825.2016.1260089.

- Bowen, H.R. 1953. Social responsibilities of the businessman. Iowa: University of Iowa Press.

- Brezovec, T. 2015. “Razvoj hotelske ponudbe na slovenski obali” [Development of the hotel services on the Slovenian coast.” In Retrospektiva turizma Istre, ed. M. Šuligoj, 111–42. Koper/Capodistria: Založba Univerze na Primorskem.

- Brezovec, T., and A. Brezovec. 2021. “Yugoslavia awaits you: Post WW2 tourism promotion of the Yugoslav coast.” In Coastal tourism in Southern Europe in the XXth century: New economy and material culture, ed. P. Battilani and C.L. Rodríguez, 171–86. Berlin: Peter Lang GROUP International Academic Publishers.

- Calic, M.-J. 2019. A history of Yugoslavia. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press.

- Carroll, A.B. 1999. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society 38, no. 3: 268–95. doi:10.1177/000765039903800303.

- Carroll, A.B. 2008. “A history of corporate social responsibility: Concepts and practices.” In The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility, ed.A. Crane, D. Matten, A. McWilliams, J. Moon, and S.D. Siegel, 19–46. New York: Oxford University Press 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211593.003.0002

- Čepič, Z. 1997. “Zakonske osnove racionirane preskrbe v Jugoslaviji 1945-1948” [Legal basis of rationed provision in Yugoslavia 1945-1948]. Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 37, no. 2: 451–61.

- Čepič, Z. 1999. “Oris načel zagotovljene preskrbe v Jugoslaviji v obdobju 1948-1953” [An outline of the guaranteed supply scheme in Yugoslavia between 1948 and 1953]. Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 39, no. 2: 157–68.

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library. 1999. The Former Yugoslavia. Retrieved from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/705487?ln=en

- Davis, K. 1960. Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? California Management Review 2, no. 3: 70–76. doi:10.2307/41166246.

- Duda, I. 2010. “Workers into Tourists: Entitlements, desires, and the realities of social tourism under Yugoslav Socialism.” In Yugoslavia’s Sunny Side: A History of Tourism in Socialism (1950s–1980s), ed.H. Grandits and K. Taylor, 33–68. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press 10.1515/9786155211874-004

- Duda, I. 2015. “Socijalni turizam i socijalizam: slučaj Fažana” [Social tourism and socialism: the case of Fažana.” In Zbornik javnih predavanja 3 [Collection of public lectures], ed. M. Cerić and M. Mrak, 49–58. Pazin: Državni arhiv u Pazinu.

- Flere, S., and T. Rutar. 2021. Why do political elites fracture? The unusual case of the Yugoslav communist elite. Journal of Historical Sociology 34, no. 4: 652–64. doi:10.1002/johs.12340.

- Fyfe, D., and D. Holdsworth. 2009. Signatures of commerce in small-town hotel guest registers. Social Science History 33, no. 1: 17–45. doi:10.1017/S0145553200010890.

- Glažar, N. 2000. Slovenske in zvezne turistične konference 1945–1949 [Slovene and Yugoslav conferences on tourism]. Arhivi 23, no. 2: 75–82.

- Gorsuch, A.E. 2003. “There’s no place like home”: Soviet tourism in late stalinism. Slavic Review 62, no. 4: 760–85. doi:10.2307/3185654.

- Graff, H. 2016. The ‘problem’ of interdisciplinarity in theory, practice, and history. Social Science History 40, no. 4: 775–803. doi:10.1017/ssh.2016.31.

- Hall, D.R. 1984. Foreign tourism under socialism: The Albanian ‘Stalinist’ model. Annals of Tourism Research 11, no. 4: 539–55. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(84)90047-1.

- Hall, D.R. 1990. Stalinism and Tourism: A study of Albania and North Korea. Annals of Tourism Research 17, no. 1: 36–54. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(90)90113-6.

- Horna, J.L.A. 1988. Leisure studies in Czechoslovakia: Some east‐west parallels and divergences. Leisure Sciences 10, no. 2: 79–94. doi:10.1080/01490408809512179.

- Hunzicker, W. 1957. “Cio che rimarrebbe ancora da dire sul turismo sociale” [What would still remain to be said about social tourism]. Revue de tourisme 2: 52–57.

- Hunziker, W. 1951. Social tourism: Its nature and problems. Berne: Impr. Fédérative.

- Ivanov, S. 2009. Opportunities for developing communist heritage tourism in Bulgaria. Tourism 57, no. 2: 177–92.

- James, K.J., and P. Vincent. 2016. “The guestbook as historical source.” Journal of Tourism History 8(2): 147–66. doi: 10.1080/1755/182X.2016.1199602ć

- Jeraj, M. 1995. Slovenski sindikati in socialna politika 1945 – 1950 [Slovenian trade unions and social policy 1945 – 1950]. Ljubljana: Arhiv Republike Slovenije.

- Jeraj, M. 2003. Komunistična partija, Antifašistična fronta žensk in uresničevanje ženske enakopravnosti v Sloveniji (1943-1953) [Communist party, Anti fascist women’s league and the realisation of the equality of women in Slovenia (1943-1953)]. Arhivi 26, no. 1: 161–78.

- Jeršič, M. 1968. “Sekundarna počitniška bivališča v Sloveniji in Zahodni Istri” [Weekend houses or dwellings in Slovenia and on the West-Istrian shore]. Geografski vestnik 40: 53–67.

- Jule. 1958. ““Počitniški domovi se že odpirajo” [Holiday Homes are already opening].” Slovenski Jadran: glasilo SZDL April 25: 9

- Kavrečič, P. 2017. Turizem v Avstrijskem primorju. Zdravilišča, kopališča in kraške jame (1819-1914) [Tourism in the Austrian Littoral. Spas, baths and karst caves (1819-1914)]. Koper: Založba Univerze na Primorskem.

- Kavrečič, P. 2020. Tourism and fascism: Tourism development on the eastern Italian border.”Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino. Contributions to Contemporary History 60, no. 2: 99–119. doi:10.51663/pnz.60.2.05.

- Kavrečič, P., and M. Koderman. 2014. ““Slovenski izseljenci in turistični obisk Dravske banovine s posebnim poudarkom na poročanju Izseljeniškega vestnika” [Slovenian emigrants and tourist visits to the Drava banovina according to the reports in the journal “Izseljeniški vestnik”].” Annales Histoire, Sciences Sociales 24, no. 1: 77–94.

- Kavrečič, P., and M. Šuligoj. 2021. “Socialist- style tourist accommodation.” In Coastal Tourism in Southern Europe in the XXth century: New economy and material culture, ed. P. Battilani and R.C. Larrinaga, 155–70. Berlin: Peter Lang GROUP International Academic Publishers.

- Kranjčević, J. 2019. “Tourism on the Croatian Adriatic coast and world war I.” Academica Turistica - Tourism and Innovation Journal 12, no. 1: 39–50. doi:10.26493/2335-4194.12.41-53.

- Kukić, L. 2018. “Socialist growth revisited: Insights from Yugoslavia.” European Review of Economic History 22, no. 4: 403–29. doi:10.1093/ereh/hey001.

- Latapí, A., M. Andrés, L. Jóhannsdóttir, and B. Davídsdóttir. 2019. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 4, no. 1: 1–23. doi:10.1186/s40991-018-0039-y.

- Lee, D.K. 2016. Alternatives to P value: Confidence interval and effect size. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology 69, no. 6: 555–62. doi:10.4097/kjae.2016.69.6.555.

- Light, D., and D. Dumbrăveanu. 1999. Romanian tourism in the post-communist period. Annals of Tourism Research 26, no. 4: 898–927. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00033-X.

- Light, D.B., and R.J. Seaman. 1982. Cluster analysis of organizational memberships: A methodology for the reconstruction of association patterns from organizational records. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 15, no. 1: 11–15. doi:10.1080/01615440.1982.10594075.

- Logoreci, A. 1977. The Albanians: Europe's forgotten survivors. London: Gollancz.

- McNee, A. 2020. ‘Arry and ‘Arriet ‘out on a spree’: Trippers, tourists and travellers writing in late-Victorian visitors’ books. Studies in Travel Writing 24, no. 2: 142–56. doi:10.1080/13645145.2020.1847836.

- Mücke, P. 2021. Hidden, yet visible workers of Czechoslovak international tourism. Macro and micro-historical views of ČEDOK’s branches abroad and tour guides during the period of late socialism (1968–1989). Journal of Tourism History 13, no. 1: 75–94. doi:10.1080/1755182X.2020.1854353.

- Odredba o ukrepih za varčevanje s predmeti široke potrošnje [Decree on measures to save consumer goods]. 1950. Uradni list FLRJ [Official gazette of the federal people’s republic of Yugoslavia], 59, October 18, 937–39.

- Opačić, V.T., and M. Koderman. 2018. “From socialist Yugoslavia to the European Union: Second home development in Croatia and Slovenia.” In The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities, ed.C.M. Hall and D. Müller, 167–78. New York, Abingdon (Oxon): Routledge 10.4324/9781315559056-14

- Prinčič, J. 1997. Slovensko gospodarstvo v drugi Jugoslaviji [The Slovenian economy in the second Yugoslavia]. Ljubljana: Modrijan.

- Quek, M. 2012. Globalizing the hotel industry 1946–68: A multinational case study of the Intercontinental Hotel Corporation. Business History 54, no. 2: 201–26. doi:10.1080/00076791.2011.631116.

- Repe, B. 1996. “Turizma ni mogoče zavreti, čeprav bi ga prepovedali z zakonom” [Tourism cannot be suppressed, even if it is prohibited by law.” In Razvoj turizma v Sloveniji: zbornik referatov, ed. F. Rozman and Ž. Lazarevič, 57–164. Ljubljana: Zveza zgodovinskih društev Slovenije.

- Repe, B. 2006. “Turistična zveza in razvoj turizma v Sloveniji po drugi svetovni vojni” [The tourist association and the development of tourism in Slovenia after the Second World War].” In Turizem smo ljudje: zbornik ob 100-letnici ustanovitve Deželne zveze za pospeševanje prometa tujcev na Kranjskem, Turistične zveze Slovenije in organiziranega turizma v Sloveniji: 1905-2005, ed. S. Šajn, 61–99. Ljubljana: Turistična zveza Slovenije.

- Rittichainuwat, B.N. 2013. ’tourists’ perceived risks toward overt safety measures. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 37, no. 2: 199–216. doi:10.1177/1096348011425494.

- Rogoznica, D. 2005. Obnova in razvoj turizma na območju cone Svobodnega tržaškega ozemlja (s posebnim ozirom na okraju Koper. [The Groundwork and Development of Tourism in Zone B of the Free Territory of Trieste (With Special Emphasis on the Koper District)] Acta Histriae 13, no. 2: 395–422.

- Rogoznica, D. 2014. “Aplikacija in uveljavitev modela socialističnega turizma na slovenski obali (1947─1990)” [The application of the socialist tourist model on the Slovenian coast (1947-1990)]. Arhivi 37, no. 2: 73–84.

- Rosenbaum, A.T. 2015. Leisure travel and real existing socialism: New research on tourism in the Soviet Union and communist Eastern Europe. Journal of Tourism History 7, no. 1–2: 157–76. doi:10.1080/1755182X.2015.1062055.

- Sesma, C.D., J. Kok, and M. Oris. 2022. “Internal migrant trajectories within the Netherlands, 1850–1972: Applying cluster analysis and dissimilarity tree methods.” Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History doi:10.1080/01615440.2022.2047852.

- Sindbaek, T. 2013. Usable History: Representations of Yugoslavia’s Difficult Past from 1945 to 2002. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press 10.2307/j.ctv62hhpn

- Sitar, P. 2020. “Workers becoming tourists and consumers: Social history of tourism in socialist Slovenia and Yugoslavia.” Journal of Tourism History 12(3): 254–74. Skupščina občine Piran s Predhodniki, SI PAK PI 36. Regional Archive Koper [Pokrajinski arhiv Koper, enota Piran/Archivio Regionale di Capodistria, unità Pirano]. doi: 10.1080/1755182X.2020.1857096.

- Slocum, S.L., and V. Klitsounova eds. 2020. Tourism development in post-soviet nations: From communism to capitalism. Palgrave Macmillan Cham. 10.1007/978-3-030-30715-8

- Šorn, M. 2017. “Odnos med zaposlenimi v Dekorativni in Pletenini ter njihovimi upokojenkami in upokojenci” [Relationship between the employees of the Dekorativa and Pletenina factories and their pensioners].” In Starost – izzivi historičnega raziskovanja, Vpogledi 18, ed. M. Šorn, 253–65. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino.

- Stefan, A. 2022. “Unpacking tourism in the cold war: International tourism and commercialism in socialist Romania, 1960s–1980s.” Contemporary European History:1–20. doi:10.1017/S0960777321000540.

- Šuligoj, M., ed. 2015. Retrospektiva turizma Istre [Retrospective of Istria’s tourism]. Koper: Založba Univerze na Primorskem.

- Šuligoj, M. 2020. Characterization of health-related hotel products on the Slovenian coast. Geoadria 25, no. 1: 39–52. doi:10.15291/geoadria.3158.

- Szijártó, I. 2002. Four arguments for microhistory. Rethinking History 6, no. 2: 209–15. doi:10.1080/13642520210145644.

- Szołtysek, M., and B. Ogórek. 2020. How many household formation systems were there in historic Europe? A view across 256 regions using partitioning clustering methods. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 53, no. 1: 53–76. doi:10.1080/01615440.2019.1656591.

- Taylor, K., and H. Grandits. 2010. “Tourism and the making of socialist Yugoslavia. An Introduction.” In Yugoslavia’s Sunny Side: A History of Tourism in Socialism (1950s–1980s), ed.H. Grandits and K. Taylor, 1–30. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press 10.1515/9786155211874-003

- Tchoukarine, I. 2010. “The Yugoslav road to international tourism. Opening, decentralization, and propaganda in the early 1950s.” In Yugoslavia’s Sunny Side: A History of Tourism in Socialism (1950s–1980s), ed. H. Grandits and K. Taylor 107–38. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press. 10.1515/9786155211874-006

- Tchoukarine, I. 2015. Yugoslavia’s open-door policy and global tourism in the 1950s and 1960s. East European Politics and Societies 29, no. 1: 168–88. doi:10.1177/0888325414551167.

- Tkaczynski, A. 2017. “Segmentation using two-step cluster analysis.” In Segmentation in Social Marketing, ed. T. Dietrich, S. Rundle-Thiele, and K. Kubacki 109–25. Singapore: Springer. 10.1007/978-981-10-1835-0_8

- Uredba o plačanem letnem dopustu delavcev, namešcencev in uslužbencev [Regulation on paid annual leave for workers and employees]. 1946. Službeni list FNRJ [Official Gazette of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia], 56, July 12, 650.

- Ustava Ljudske Republike Slovenije. 1947. [Constitution of the People’s Republic of Slovenia of 1947]. Ljubljana: Prezidij Ljudske skupščine Ljudske Republike Slovenije.

- Vodopivec, N. 2014. “Družbene solidarnosti v času socialističnih tovarn in individualizacije družbe” [Social solidarities in the times of socialist factories and societal individualization]. Ars & Humanitas 8, no. 1: 136–50. doi:10.4312/ars.8.1.136-150.

- Vodopivec, N. 2015. Labirinti postsocializma, socialni spomini tekstilnih delavk in delavcev [Labyrinth of post-socialism, social memories of textile workers]. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino.

- Zabukovec Baruca, P., and Ž. Čivre. 2012. How do guests choose a hotel? Academica Turistica: Tourism & Innovation Journal 5, no. 1: 75–84.

- Zakon o nacionalizaciji zasebnih gospodarskih podjetij [Law on the nationalisation of private enterprises]. 1946. Uradni list FLRJ [Official gazette of the federal people’s republic of Yugoslavia], 98, December 6, 1245–47.