?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The Turkish presidential election in 2023 marked a pivotal moment for the ruling Justice and Development Party and Erdoğan, grappling with criticism over their handling of the economic crisis. Six parties formed the Nation Alliance to challenge the incumbent, but negotiations for the alliance’s presidential candidate collapsed, leading to the breakdown of the alliance. This study analyzes the divided opposition and its difficulty in nominating a likeable candidate as another reason for the continuation of President Erdoğan’s rule. A Response Surface Analysis (RSA) approach is utilized to describe the potential outcomes of the options that opposition parties considered regarding their presidential candidate. The analysis shows that the leader of the Republican People’s Party, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, was weaker in appealing to the centre-right wing voters of the alliance partner, the Good Party, yet fared better in gathering the support of the Kurdish voter base of the Peoples’ Democratic Party.

Introduction

Inquiries into how incumbents in competitive authoritarian regimes remain in office primarily focus on the lack of a level-playing field created by institutional and structural challenges. Incumbents in competitive authoritarian elections create advantages through changes in the election system, privileged access to campaign finance, and control over the media, which makes winning voters’ hearts easier (Esen and Gumuscu Citation2016; Morse Citation2012). This article focuses on another factor that may stack cards in favour of the incumbent autocrat: the difficulty of finding a competitive opposition candidate.

Incumbents in competitive authoritarian regimes win or lose elections based on complex judgements of their performance. Following simple Downs (Citation1957) logic, these judgements could combine retrospective and prospective orientations, focusing on salient policy domains. When the incumbent’s performance fares better (or worse) than its competitors in either a hypothetical retrospective judgement about how they could have performed if they were in power instead of the incumbent or a prospective judgement about likely performance in the future, the incumbent has an electoral (dis)advantage. These judgements are complex because they reflect a mixture of different time orientations and policy domains and are likely to be weighted differently by different voters (Blumenstiel and Plischke Citation2015; Vecchione et al. Citation2013). This level of complexity is likely to rise in a non-linear fashion when an incumbent faces various potential candidates with a divided opposition. An excess of contenders against an autocratic incumbent can splinter votes, hindering consensus on a single opposition candidate. Yet, identifying a challenger capable of defeating the incumbent amid this array remains a formidable challenge.

On 14 May 2023, Turkey held a critical election for the Turkish Grand National Assembly (Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi – TBMM) and presidency. These elections were significant because Turkey has seen an erosion of democratic institutions and principles in recent years, raising concerns about the regime’s transformation into competitive authoritarianism. As such, these elections held the potential to counter democratic backsliding by challenging the incumbent Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi - AKP) and its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The opposition, emboldened by the success of the 2019 local elections, stood at a unique crossroads.

Given these considerations, this study explores the fragmented opposition and its struggle to find an appealing candidate to challenge the two-decade tenure of the AKP and President Erdoğan. We examine the respective appeal of three presidential candidate options that the opposition parties considered in the build-up to the elections: Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (the eventual opposition candidate), Ekrem İmamoğlu, and Mansur Yavaş. To do so, we utilize response surface analysis (RSA) methodology, which allows us to assess the joint effects of two independent variables, namely, trust in the constituency of respective alliance party members, on the likeability of alternative candidates.

The next section offers a concise overview of Turkey’s political context, highlighting the challenges for the incumbent AKP and the emergence of the opposition alliance. Subsequently, we delve into existing literature on pre-election alliances and candidate selection. Following this, a detailed summary outlines the candidate selection process of the opposition alliance. The subsequent sections present the data, results, and implications. Our findings indicate a sense of unease among the constituencies of the Good Party (İyi Parti - IYIP) regarding Kılıçdaroğlu as a candidate for the Nation Alliance. Imamoğlu and Yavaş were perceived more favourably than Kılıçdaroğlu in these constituencies. However, our results also suggest that when facing a typical Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi - HDP) voter, Kılıçdaroğlu enjoyed a likeability advantage. Hence, the decision against Kılıçdaroğlu involved a difficult choice between alternatives whose vote potential differed across constituencies.

The political context before the 2023 election

Many political pundits in Turkey considered the 2023 elections for TBMM and presidency an opportunity for the opposition because the ruling AKP and its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who had been in power for nearly 21 years, faced concerns of inadequate performance on several issue domains or the so-called ‘metal fatigue’ in the administration. This term was first coined during the campaign period for the local elections in 2019 when several incumbent AKP mayors were pressured to retire and did not seek re-election. In the 2023 presidential election, mayors of Ankara and Istanbul, who won highly prized municipal mayorships in the 2019 local elections, participated in the opposition campaign.

The prolonged economic crisis, exacerbated by the president’s insistence on strict control and low interest rates, disregarding market dynamics, resulted in money market imbalances, currency depreciation, and increased inflation, which was an essential reason for so-called metal fatigue. Additionally, the slow response and inadequate handling of the aftermath of the two earthquakes in 12 southeastern provinces, home to almost 10% of the population, by the administration fuelled the perception that the AKP suffered from metal fatigue.

As the incumbent AKP seemed to face backlash due to its inadequate performance on many issue fronts, the opposition parties and their leaders showed a solid determination to cooperate and present a united front against the incumbent establishment. Six political parties spanning the ideological spectrum formed an election alliance, Nation Alliance (Millet İttifakı) and presented a broad range of policy alternatives while aiming to field and campaign for a single joint candidate to secure a majority in the TBMM and presidency.

However, identifying a candidate with a mass appeal that could secure a winning majority proved more challenging than anticipated. Approximately a month after a devastating earthquake struck the country, resulting in the loss of over 50,000 lives, negotiations for the Alliance’s presidential candidate collapsed following heated public statements. The leadership of the IYIP, the second-largest party in the alliance, expressed growing frustration with the process of selecting a candidate. Specifically, they argued that if Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of the largest alliance member, the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi - CHP), were to be the candidate, winning the presidency would be a significant challenge, if not impossible. Consequently, the IYIP suggested finding an alternative candidate, implying that metropolitan mayors of either Istanbul or Ankara would be more suitable, appealing to the ideologically heterogeneous voter base of the parties in the Nation Alliance. However, both mayors were elected from the CHP and were unwilling to challenge their party leader for a presidential candidacy.

The Nation Alliance suffered a breakdown when the leadership of the IYIP was reportedly pressured to accept Kılıçdaroğlu’s presidential candidacy. However, with elections less than three months away, the opposition had no alternative plans for cooperation and was forced to reconvene to negotiate a new deal that would allow Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu to run against Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Central to this deal was the addition of mayors of Istanbul and Ankara, both of whom successfully defeated incumbent AKP candidates in the 2019 local elections, Kılıçdaroğlu’s running mates. Kılıçdaroğlu ran a campaign alongside the two metropolitan mayors and other alliance party leaders. Although Kılıçdaroğlu was able to push the presidential election to a second run-off, he ultimately lost the election by approximately 2.3 million votes. The Nation Alliance was also unable to control the majority of the TBMM and lost both critical elections.

Whether the Nation Alliance could win the elections if, as the IYIP leadership suggested, either Istanbul or Ankara mayors were selected as the alliance candidate remains highly debated. Although we cannot definitively answer this question, we can infer and compare the potential of these three politicians based on their appeal to voters from various parties, including CHP and IYIP. An analysis of the consequences of the selection of Kılıçdaroğlu as the alliance candidate over the mayors of Istanbul and Ankara also needs to consider the viability of these candidates among the constituencies of the HDP.

In short, given the state of the economy and the inadequacy of relief efforts after the massive earthquakes just before the May 2023 elections, an unrealized expectation of a win for the opposition was created. These expectations overlooked the challenge of finding strong candidates for the divided opposition. As discussed later, the opposition could only secure the presidency with a credible and likeable candidate capable of appealing to incumbent alliance supporters, persuading some to switch sides, and keeping opposition alliance supporters united. To what extent did the opposition candidate, Kılıçdaroğlu, fulfil this competitive and likeable candidate requirement? In the next section, we briefly expand on pre-election alliances in majority-run-off systems and provide some insights from the literature. This is then followed by the section regarding the dilemma faced by the Nation Alliance in selecting a presidential candidate to run against incumbent Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. We then present our data and results and evaluate their implications.

Electoral alliances and candidate selection

Theoretical and empirical analyses of electoral alliances are motivated by the majority-run-off (MR) electoral system, where a second round of election occurs among the top two highest vote-obtaining candidates unless a candidate receives the majority of votes in the first round. MR systems tend to result in highly disproportional seats-votes outcomes in multiparty systems (Duverger Citation1954). Under these conditions, political parties and candidates have strong incentives to form electoral alliances. Sartori (Citation1994) found that this arrangement creates clear choices for voters on the demand side and pushes parties and candidates on the supply side to cooperate. The run-off arrangement is used in elections for legislative seats but most often in elections for executive positions, such as presidents (Blais et al. Citation1997).Footnote1 Using an analytical model, Golder (Citation2006) shows that electoral coalitions are more likely when potential allies are ideologically close and when there is extreme opposition to the incumbent.Footnote2

Post-election coalitions have attracted attention in Turkish political science literature. Most of these works focus on the pre-1980 period, despite the fact that the 1990s exemplify many coalitions in the TBMM due to fractionalized election results.Footnote3 More recent attention to pre-election alliances has focused mostly on the consequences of these alliances under the newly imposed legal framework before the 2018 elections.Footnote4 Başkan et al. (Citation2022) provide the only in-depth analysis of the ideological similarities within the newly formed alliances and diagnose that while the People’s Alliance (Cumhur İttifakı) of 2018 was between ideologically similar parties, the opposition Nation Alliance was built amongst dissimilar parties.

As in 2018, electoral support constellations before the May 2023 elections provide a somewhat contrasting setting to the analytical expectations of the models used in the literature. While the People’s Alliance is built among right-of-centre parties such as the AKP, Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi - MHP), The Great Unity Party (Büyük Birlik Partisi - BBP), the New Welfare Party (Yeniden Refah Partisi - YRP), and the Free Cause Party (Hür Dava Partisi – HÜDA-PAR), the opposition Nation Alliance included the centre-left CHP, centre-right IYIP, right-of-centre Democracy and Progress Party (Demokrasi ve Atılım Partisi - DEVA), and the Future Party (Gelecek Partisi - GP) as well as the pro-Islamist Felicity Party (Saadet Partisi - SP). The existence of extreme opposition to the Cumhur Alliance may be valid only if the Kurdish HDP’s presence on the left margin of the Turkish left-right spectrum is considered. Even this consideration is not entirely satisfactory since ideological similarities are apparent between some members of both alliances. The ideological positions of SP, DEVA, and GP are similar to those of at least some of the parties in the Cumhur Alliance. Hence, the expectation of extreme ideological opposition does not hold for either alliance.

Nevertheless, as outlined next, the ideological congruity of the parties in a pre-election alliance is only one of the factors that influence the extent to which opposition voters will mobilize to vote for a joint candidate. For example, especially when a coalition comprises parties of varying sizes and ideological stances, questions about the viability of the candidate – whether voters think that the candidate can beat the incumbent – can be a key determinant of whether voters will mobilize for a candidate (Utych and Kam Citation2014). Indeed, as discussed hereinabove, questions about the viability of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu were one of the key reasons why IYIP, the second largest party in the opposition alliance, was against nominating him as the opposition candidate.

Another factor that prior literature underscores as a key predictor of whether a candidate will win over ideologically heterogeneous voters is the character attributions that voters make about the candidate. Marsh (Citation2007), for instance, reports that one theme that most frequently appeared in response to the question about the main reason for voting for a candidate was the candidate’s personal characteristics. This theme was related to characteristics related to the candidate’s warmth and likeability, such as ‘good’ness and ‘sincere’ness. Close to 40% of the responses referenced personal characteristics as a major factor contributing to voting decisions. Likewise, emphasizing the importance of candidate traits over issue stances, Garzia (Citation2013) reports that perceptions of leaders’ personal traits play a significant role in election results.

Politicians may attract or repel votes based on how voters perceive their personality traits, which is distinct from the electoral impact of their stance on issues. Bittner (Citation2011) argues that evaluating leaders’ character (honesty, compassion, warmth, or empathy) is central to voting decisions because this is how we process other human beings, making the evaluation of candidates relatively easy for voters, particularly those with limited interest in politics. Complementing these results on the influence of character traits on vote choice, Aaldering et al. (Citation2018) assert that the valence of the media portrayal of a leader’s character traits (general competence, honesty, friendliness) influences electorates’ support for a candidate.

Recent research on other competitive authoritarian regimes with strong incumbents supports the idea that candidate traits play a significant role in encouraging strategic voting against the incumbent. For instance, Turchenko and Golosov (Citation2023) found that opposition candidates/parties perceived as closer to the status quo are less likely to benefit from strategic voting in pre-electoral alliances against an autocratic incumbent. Therefore, successful opposition candidates are likely to differ significantly from incumbents in terms of their relevant attributes. The 2022 Hungarian parliamentary election provides an illustration of this. During the primaries, Péter Márki-Zay, an independent politician, emerged as the candidate for a six-party anti-Orbán alliance. Márki-Zay’s candidacy stood in sharp contrast to other candidates with close ties to the parties in the alliance, potentially making him more appealing to right-wing voters (Popescu and Gábor Citation2021). However, despite these efforts, Viktor Orbán won the re-election, extending his tenure as Hungarian prime minister for a fourth term. While the factors contributing to Orbán’s victory are beyond the scope of this discussion, a relevant point to note is that Márki-Zay faced difficulties in building rapport with opposition voters. For instance, a recent study by Metz and Plesz (Citation2023) found that both pro-Orbán and opposition voters had low emotional connections with Márki-Zay.

Analyses of candidate traits, however, suffer from inherent endogeneity due to the partisan identity of respondents being directly linked to the way they evaluate the candidates. Candidates of one’s own party tend to be evaluated as better independent of candidate traits. Shephard and Johns (Citation2008, 324) report that ‘even controlling for the partisanship of both the “candidate” and the respondent, trait evaluations based on appearance are significant and, in the case of “warmth” traits like likeability and caring, powerful predictors of probability to vote.’

Similarly, Nai et al. (Citation2021) experimentally manipulated a candidate’s personality traits and assessed their subsequent effects. Their results indicate that the public dislikes ‘dark’ politicians and rates them significantly and substantially lower in likeability. However, voters who score higher on ‘dark’ personality traits (e.g., Machiavellianism) tend to like dark candidates. The influence of candidates’ personality traits was more substantial for respondents with weaker partisan attachments.

The salience of partisan identification for candidate evaluations and the lack of ideological coherence in the Nation Alliance creates a dilemma in candidate selection. While the CHP in the opposition alliance has a long party history with relatively more solid party identification within its party rank and file, other alliance members like the IYIP, DEVA, and GP are much younger organizations for which party identification is not expected to be as strong. As such, given the results from Nai et al. (Citation2021), it is likely that the personality traits summarized by the likeability of alliance candidates are more likely to be influenced by partisan identification reflected in trust in constituencies of other parties within the coalition. Our research builds on this observation and provides empirical evidence of these difficulties. Below, we provide an in-depth evaluation of the inner dynamics that made candidate selection difficult for the Nation Alliance.

Selection of the opposition candidate in 2023

As of May 2023, as the presidential and assembly elections approached, the electoral appeal of the incumbent AKP and its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, deteriorated. A major step in this decline in electoral support was the loss of major metropolitan municipalities in Istanbul, Ankara, İzmir, and Adana in March 2019. Although the İzmir municipality was never under AKP control, the Adana municipality was controlled by AKP’s coalition partner MHP mayors’ decade-long tenures. More significantly, Ankara’s and Istanbul’s greater city municipalities have been controlled by the AKP or its pro-Islamist predecessor party mayors for more than two decades. President Erdoğan’s political career began with a successful mayoral race in 1994 as a pro-Islamist Welfare Party (Refah Partisi - RP) candidate.

Losing both metropoles after almost a quarter of a century was not an easily acceptable defeat for the AKP leadership, who led the effort for cancelling the Istanbul election by the Supreme Election Council because of ‘situations which affected the results and honesty of the polls.’Footnote5 This cancellation led to a re-election on 23 June 2019, in which the opposition candidate İmamoğlu won with an undisputable margin. İmamoğlu’s remarkable win in an uneven competition against the well-known AKP candidate Binali Yıldırım in Istanbul catapulted him into the national political arena (Esen and Gümüşcü Citation2019). Even though he was initially an unknown mayor of Beylikdüzü, one of the 39 districts in Istanbul, İmamoğlu was immediately recognized as a potential presidential candidate for the upcoming elections. İmamoğlu came to the Istanbul race with the credentials of being the mayor of Beylikdüzü, a minor electoral district containing only about 2% of Istanbul’s 10.5 million voters. Erdoğan actively campaigned against İmamoğlu but ultimately failed to eliminate him from electoral politics and unwittingly contributed to his popular rise in national politics as an opposition leader. İmamoğlu’s win in Istanbul also showcased the strategic appeal of electoral alliances against the incumbent AKP. Similar to the presidential race, where the first-past-the-post election system was applied, İmamoğlu put together a winning coalition of unlikely partners. He not only became popular among the CHP constituencies but was also able to attract voters from the right-of-centre IYIP and left-of-centre Kurdish voters of the HDP. His potential as a challenger to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is underscored by the threat of a political ban he faced after a Turkish court sentenced him to prison in a ruling that was made six months before the election. Many critics saw the court’s decision as politically motivated (Kenyon Citation2022).

Mansur Yavaş, a lawyer, was also a winner against a major figure of the AKP, Mehmet Özhaseki, by a slim margin of less than 124 thousand votes. Özhaseki was elected mayor of Melikgazi central district of Kayseri in 1994. He eventually moved up to win the Greater City Municipality race and served as mayor of Kayseri between 1998 and 2015. He was then elected to the TBMM and became the Minister of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change until he ran as a mayoral candidate for Ankara Greater City Municipality in 2019. Hence, he carried the weight of local government experience in a prominent central Anatolian metropolitan city and the experience of a ministry with a significant budget and major projects directly relevant to the local government.

Mansur Yavaş’s political career began in the MHP, where he served as the mayor of Beypazarı, a district of Ankara, from 1999 to 2009. He then left the MHP and joined the CHP in 2013, becoming a candidate for the mayorship of Ankara’s Greater City Municipality. However, he lost the election to Melih Gökçek with a narrow margin of 37 thousand votes. Yavaş’s candidacy from the Nation Alliance in the 2019 Ankara mayoral election was successful due to his ability to mobilize right-of-centre IYIP voters with his MHP background. In contrast to İmamoğlu, who gained significant support from both IYIP and Kurdish voters in Istanbul, Yavaş primarily relied on the Turkish nationalist electoral base to complement the CHP vote required to win the Ankara mayoral race. Both İmamoğlu and Yavaş demonstrated the logic of the Nation Alliance by bringing together a winning majority of electoral constituencies with different ideologies. Kurdish ethnic votes and left- and right-of-centre electoral bases were mobilized to win in Ankara and Istanbul, respectively. These two candidates successfully balanced the opposing ends of their support base.

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu has gradually developed the idea and built the Nation Alliance. An economist by training, Kılıçdaroğlu was a civil servant who headed the Social Insurance Institution before entering TBMM in 2002. In 2009, he ran an unsuccessful campaign for the mayoral candidate of Istanbul Greater City Municipality. A year later, after a momentous scandal that toppled CHP leader Deniz Baykal, he was elected as the chairman of the CHP. At the helm of the main opposition party, he ran four general election campaigns before the May 2023 elections. His party’s electoral support fluctuated around 25% between 2011 and 2015 before settling on 22.7% in 2018. However, the opposition vote base expanded in 2018 with the IYIP entering the electoral scene after splitting from the MHP and began appealing to disenchanted AKP supporters closer to the ideological spectrum’s centre.

After an unsuccessful challenge to the MHP party leadership and insistence on a no vote in the 2017 constitutional referendum, the IYIP had only five seats in the TBMM and could not form a parliamentary group, a requirement for a party to secure its running in the 2018 elections without having to collect signatures for its presidential candidate. Kılıçdaroğlu orchestrated a ‘loan’ of 15 CHP representatives to IYIP that allowed IYIP to not only form a parliamentary group but also avoid having to collect signatures for its party leader to run against Erdoğan in the presidential election. Subsequently, the IYIP joined the Nation Alliance with the CHP, SP, and Democrat Party (Demokrat Parti - DP) in the TBMM elections, securing 9.96% of the vote. As a presidential candidate, Meral Akşener, the leader of the IYIP, received only 7.3%, a lower vote share than her party’s support in the TBMM election. However, the Nation Alliance’s first elections in 2018 showed that the alliance logic lures dissatisfied conservative constituency votes away from the AKP-MHP, primarily to more centrist IYIP and possibly to other right-of-centre parties such as the pro-Islamist SP.

With the 2023 elections approaching, two prominent figures from the AKP, the former foreign affairs minister and Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, formed his party, the GP, and again, the former foreign affairs minister and deputy prime minister responsible for the economy Ali Babacan formed DEVA. These departures from the AKP were seen as a signal that it would be possible to appeal to dissatisfied AKP supporters, providing yet another incentive to expand the opposition Nation Alliance to include these new parties. Eventually, both GP and DEVA joined the Nation Alliance, comprising three parties of the splinters from AKP and MHP, the IYIP, GP, and DEVA, one old-guard pro-Islamist SP, one minor centre-right DP, and the main opposition, social-democratic CHP.

The last important element in the Nation Alliance’s electoral logic was the assumed support of the HDP constituency for Nation Alliance candidates in presidential elections. The Kurdish vote was potent in securing a sizable group of parliamentarians for TBMM. However, the HDP opted against having a separate presidential candidate since this candidate, with the potential to secure about 10–13% of the vote, would have no chance against other major candidates. In this light, implied support from the HDP could have been critical to the election’s eventual outcome. If no candidate could secure more than 50% of the votes in the first round, the support of HDP constituents could potentially help determine the winner in the second run-off round.

However, appealing to the Kurdish constituency proved extremely difficult. The HDP was threatened by the Constitutional Court, where the MHP filed an appeal for its closure. The Nation Alliance argued that since the HDP is still legal, it should be treated as any other party. Hence, official or unofficial talks or negotiations were expected. However, the campaign by the incumbent AKP-MHP, which continued to associate HDP with the PKK and terrorism, dissuaded the Nation Alliance, especially the IYIP leadership rooted in the nationalist movement, from engaging with the HDP.

Our analyses build on these dynamics and evaluate different Nation Alliance candidates’ likeability as a function of trust in typical voters of the Nation Alliance. We expect İmamoğlu and Yavaş to be more favourable in facing the IYIP constituency than Kılıçdaroğlu. However, while Yavaş is not expected to be favoured by the HDP constituency, Kılıçdaroğlu and Imamoğlu are likely to appeal to these voters.

Methodology

Procedures

Our data were obtained from a nationwide three-wave panel survey conducted face-to-face in Turkey. The survey was conducted with eligible voters using a probability sampling procedure: the first wave took place between 28 January and 5 March, the second between 1 April and 6 May, and the third between 13 June and 2 July 2023. In total, 1532 respondents participated in the first wave, 995 in the second wave, and 783 in the third wave. The sampling procedure began by using the Turkish Statistical Institute’s 12 NUTS-1 regions, and one province was selected from each region using the propensity proportionate-to-size principle.Footnote6 The target sample was then distributed according to each region’s share of the urban population. Random neighbourhoods were selected, and a starting address was provided for each. The remaining households were selected using a random walk rule for every third household. Twenty households from each neighbourhood were targeted, and individuals in the households were selected based on a lottery method. No incentives were provided to the respondents.

Participants

Our analysis will use data from the second wave of the study (n = 995), which contained questions about the extent to which respondents liked the Nation Alliance candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu as well as the two CHP members, Ekrem İmamoğlu and Mansur Yavaş, whose named were proposed as alternatives to Kılıçdaroğlu, particularly by IYIP, the second largest party in the Nation Alliance. The mean age of the respondents was 41.3 (SD = 15.2), and 49.8% were female. 22% of the respondents reported having five years or less of formal education (primary school), 12% had completed eight years of education (secondary school), and 43% had a high school degree.

Measures

Trust in voters of political parties

To measure respondents’ affinity to each political party, we used items that asked respondents to rate on an 11-point scale (0 = do not trust at all, 10 = trust completely) how much they trusted voters of major political parties, including the three political parties we focus on CHP (M = 4.9, SD = 3.8), IYIP (M = 3.6, SD = 3.2), and HDP (M = 1.9, SD = 2.9). We use trusting voters of different political parties as a proxy for alliance congruence and the strength of partisan identity. We assume that higher trust in voters of other alliance members reflects proximity in the political space when using a spatial voting framework.Footnote7 Voters with weak partisan identification are also expected to have higher trust in the supporters of other parties on average. This negative link between partisan ID and trust in other party supporters is especially pertinent when polarization is on the rise. Turkey exhibits an exemplary case for a highly polarized setting in a comparative context, supporting our expectations concerning trust in other party supporters and party identification.Footnote8

Liking of candidates

Empirical works assessing the voters’ judgements predominantly use leader or candidate like-dislike scales primarily because these scales are more efficient than using multiple variables to capture the personal attributes and policy stances of leaders or candidates (Ferreira Da Silva Citation2018, 64). In addition to capturing the personality traits of the candidates, like-dislike scales also account for short-term changes in the likeability of candidates. Better-liked candidates are assumed to perform better in complex political issue spaces. Similar to Lobo and da Silva (Citation2018) and Ferreira Da Silva (Citation2018), the survey asked respondents to indicate on an 11-point scale (0 = Do not like at all, 10 = Like very much) how much they liked political leaders, including Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (M = 4.9, SD = 3.9), Ekrem İmamoğlu (M = 4.6, SD = 3.5), and Mansur Yavaş (M = 5.1, SD = 3.7).

Presidential vote in the second round of run-off

The third wave of the survey included a question asking the respondents to report which presidential candidate (Kılıçdaroğlu = 1; Erdoğan = 2) they voted for in the second round of the elections. Of the 602 respondents who answered this question, 54% reported having voted for Kılıçdaroğlu.

Analytical approach: response surface analysis

Response Surface Analysis (RSA) is an analytical technique used to account for the conjoint effects of two independent variables on a dependent variable. The method is being used increasingly in social sciences to study the impact of congruency (e.g., the influence of perceived similarity between the personality of a voter and a candidate on voting decisions, Koppensteiner and Stephan Citation2014) and incongruency (e.g., divergence between job clarity and job autonomy in predicting job satisfaction, Stoermer et al. Citation2022) of two independent variables on a dependent variable. Edwards (Citation2002) and, more recently, Nestler et al. (Citation2019) offer a detailed description of how RSA can be conducted. This section summarizes how RSA is applied and interpreted.

The first step in the RSA is a polynomial regression containing two independent variables, their quadratic transformations to test the nonlinear effects, and the interaction between the independent variables. For the research questions discussed above, the polynomial regression is as follows:

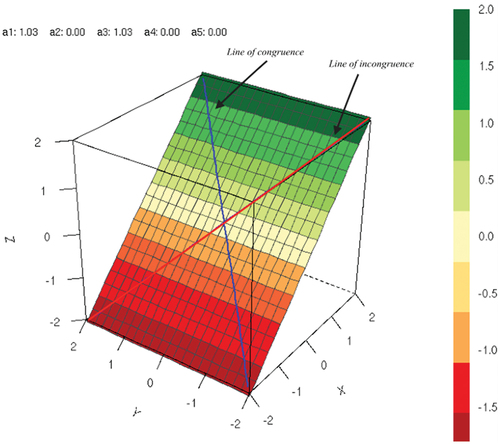

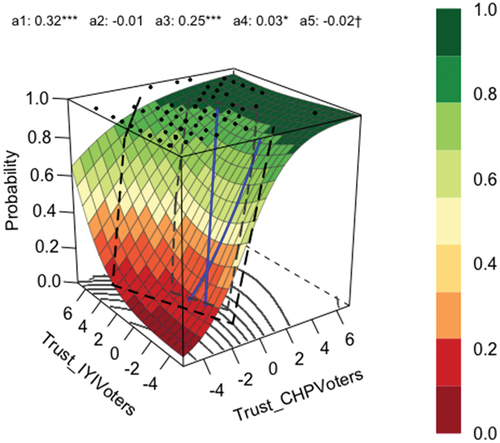

Polynomial regression coefficients are used to compute RSA coefficients and construct a three-dimensional plot of the relationship between liking a candidate and the independent variables (trust in voters of each political party). In , we summarize how RSA coefficients are calculated and what they would mean for the relationship between trust in voters of political parties and liking a presidential candidate.

Table 1. Meaning of polynomial regression and RSA coefficients.

The RSA coefficients summarized in can be used to make inferences about the conjoint effects of trust in each political party’s voters. First, coefficients a1 (b1 + b2) and a2 (b3 + b4 + b a2) represent what is called the line of congruence (LOC; the blue line in connects the lower right-hand corner and the higher left-hand corner of the cube). The Z-axis refers to the liking scores of different candidates (İmamoğlu, Kılıçdaroğlu, or Yavaş), while the Y- and X-axes refer to trust in different party voters. On the response surface, we are tracing how the liking of different candidates changes in response to shifts in the level of trust in a typical party (i.e., CHP, IYIP, HDP) voter. The line of congruence is where trust in the voters of both parties has the same value. When a1 is significant and positive, the candidate is liked more when the respondents’ trust in Party X (CHP) and Party Y (IYIP or HDP) voters is higher. This is what should be expected when analysing the impact of trust in the voters of two alliance parties on the candidate supported by the alliance. When a1 is significant and negative, this means that the candidate is liked less when respondents’ trust in Party X and Party Y voters is higher. Coefficient a2 indicates whether the relationship observed in a1 is linear or curvilinear. That is, a significant a2 should be interpreted as meaning that the line of congruence is not linear but instead produces a parabolic shape.

The coefficients a3 (b1 – b2) and a4 (b3 – b4 + b5) represent the line of incongruence (LOIC; the red line in connects the lower left-hand corner and the higher right-hand corner of the cube). The LOIC is orthogonal to the LOC. Regarding our research question, LOIC pertains to scenarios when trust in Party X and Party Y voters diverge (i.e., Trust in Voters of Party X = - Trust in Voters of Party Y). A significant and positive a3 would indicate that the liking of a given candidate increases when trust in voters of Party X is higher than that in voters of Party Y. Conversely, a negative a3 suggests that liking a candidate is higher when trust in voters of Party X is lower than trust in voters of Party Y. Coefficient a4 indicates whether the LOIC is linear or curvilinear. That is, a significant a4 should be interpreted as meaning that the line of incongruence produces a parabolic shape.

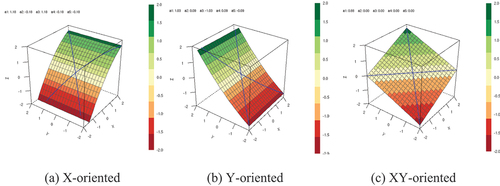

Following this basic summary of how RSA coefficients relate to the interpretation of the surfaces we estimate, next, we discuss our expectations regarding the pattern of the response surface if the liking scores of the respective candidates (i.e., Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, Ekrem İmamoğlu, and Mansur Yavaş) are to benefit from the alliance. A helpful guide for the expected shapes comes from prior research on actor-partner interdependence patterns that are observed in dyadic relationships (Schönbrodt et al. Citation2018). The first extreme is the X-oriented pattern (i.e., what Schönbrodt et al. name as the actor-oriented pattern), within which the outcome measure (in our case, the candidate’s liking) is affected only by the scores on the X-axis (see panel A, X-oriented in ). In panel A, holding the level of X constant, we observe no change in the height of the response surface as Y takes on different values; hence, at a given level of trust in voters of Party X, the liking of the candidate in question remains constant as we move along with different values of trust in typical voters of party Y. The estimated surface only changes in response to changes in trust in a typical Party X supporter. The second extreme is the Y-oriented pattern, within which the outcome measure is affected only by the scores on the Y-axis (see panel B, Y-oriented in ).

In comparison to these two extremes, an XY-oriented pattern would be observed when the outcome is affected by any combination of the X and Y axes (see panel C, XY-oriented in ). We expect that for the alliance to be of benefit to a candidate, the response surface pattern should approach the XY-oriented pattern because this would imply that when trust in voters of one political party (e.g., CHP) is low, the trust in voters of the other political party (e.g., IYIP) can compensate for the lack of trust in voters in CHP. Similarly, when trust is high for voters of both parties, the resulting liking for the candidates should also be high.

Results

We used the ‘RSA’ package in R to produce surface plots (Schönbrodt Citation2015). We first centred the predictor variables using the variable-wise mean of each predictor variable. We then created squares of the centred variables (b3, b5) and computed the interaction term (b4). Finally, we obtained the response surface coefficients using polynomial regression coefficients (i.e., a1-a4). The listwise deletion method was used for missing data, and the number of observations used for the analyses ranged from 870 to 880.

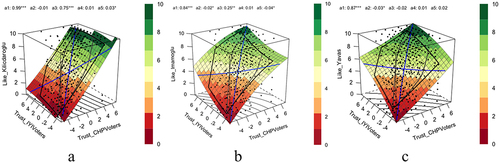

summarizes the polynomial regression coefficients and surface parameters predicting respondents’ ratings for liking Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, Ekrem İmamoğlu, and Mansur Yavaş as a function of trust in CHP voters and trust in IYIP voters. In polynomial regressions, for all candidates, trust in CHP and trust in IYIP voters positively predicted liking the candidate. For Ekrem İmamoğlu, the coefficient of the quadratic term for trust in CHP voters (b3) was significant and negative, suggesting that the slope of the liking scores for İmamoğlu became less positive at higher levels of trust in the CHP.

Table 2. Polynomial regression coefficients and surface parameters with trust in CHP voters and trust in IYIP voters as predictors.

provides a visual summary of the information obtained from the response surface analysis regarding the impact of trust in CHP voters and trust in IYIP voters predicting liking, with the predictor variable on the X-axis being trust in CHP voters and the predictor variable on the Y-axis being trust in IYIP voters. For all three candidates, a1 was positive, indicating that candidates were liked more when trust in both CHP and IYIP voters was higher. For both İmamoğlu and Yavaş, the negative a2 parameter suggests that the LOC was curvilinear, with higher scores for the predictor variables reducing the positive slope of the LOC.

Figure 3. Response surfaces predicting respondents of rating of how much they like Kılıçdaroğlu (A), Imamoğlu (B), Yavaş (C). The X-axis indicates respondents’ trust of CHP voters and Y-axis shows respondents’ trust of IYIP voters.

Concerning LOIC, the a3 parameters for Kılıçdaroğlu and İmamoğlu were positive. This implies that there is a higher liking for Kılıçdaroğlu and İmamoğlu when trust in voters of CHP is higher than that in voters of IYIP. On the other hand, a3 for Yavaş was not significant, implying that the liking of Yavaş was comparable for respondents whose trust in CHP voters was higher than that of IYIP voters and for respondents whose trust in IYIP voters was higher than that of CHP voters.

It is important to note that the parameters should not be interpreted in isolation but in conjunction with each other (Humberg, Nestler and Back Citation2019). Accordingly, to claim that a broad congruence effect (i.e., the hypothesis that agreement between two predictor variables should positively affect the outcome) is insufficient to observe a significant line of congruence. It is also necessary that the first principal axis should match the LOC (this condition is satisfied for all three candidates), a4 is significantly negative (this condition is not satisfied for any of the candidates), and a3 is not significant (this condition is satisfied for only Mansur Yavaş). In other words, it is impossible to make a congruence effect claim to argue that a higher agreement in terms of trust in CHP voters and trust in IYIP voters increases the liking ratings of any candidate.

Nevertheless, the a3 (LOIC) parameters and the ensuing surface patterns for Kılıçdaroğlu, İmamoğlu, and Yavaş are indicative of the potential for each candidate to compensate for respondents’ lower trust in one political party’s voters (CHP vs IYIP) with higher trust for the other political party’s trust (IYIP vs CHP). At one extreme, for Kılıçdaroğlu (, Panel A), what we observe is akin to the X-oriented interdependency shown in Panel A . This implies that respondents’ liking of Kılıçdaroğlu is almost solely affected by trust in CHP voters (which is higher among CHP voters). Hence, increased trust in IYIP voters (which is higher among IYIP voters or voters who feel closer to the voter base of the IYIP) is unlikely to compensate for the lower trust in CHP voters. This contrasts with Yavaş (, Panel C), whose response patterns are similar to the XY-centric interdependency pattern shown in , Panel C. This implies that the liking scores are similar across the LOIC line, potentially indicating that higher trust in the voter base of either party can help increase respondents’ chances of liking Mansur Yavaş as a candidate. Also important to note is that the LOIC line for İmamoğlu (, Panel B), while significant, is flatter than the LOIC line for Kılıçdaroğlu (with the a3 parameter for İmamoğlu lower than Kılıçdaroğlu’s), resulting in a pattern that approaches the XY-centric interdependency pattern shown in , Panel C.

The discussion above underscores that, from the standpoint of appealing to voters of both parties of the Nation Alliance, Yavaş had a considerable advantage compared to Kılıçdaroğlu and a minor advantage compared to İmamoğlu. However, as discussed in the literature review, another factor to consider is the extent to which the candidates may appeal to a significant block of voters with an affinity towards HDP, which had finished the 2018 parliamentary elections as the third major party (after AKP and CHP).

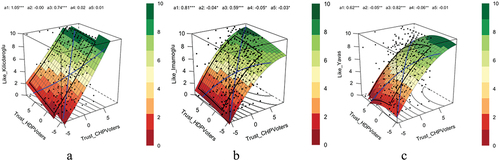

summarizes the polynomial regression coefficients and surface parameters predicting respondents’ ratings for liking Kılıçdaroğlu, İmamoğlu, and Yavaş as a function of trust in CHP voters and trust in HDP voters. For polynomial regression coefficients, one important result is that trust in HDP voters significantly increases the liking of Kılıçdaroğlu. The positive linear relationship between trust in HDP voters and liking İmamoğlu is marginally significant, and the linear relationship between trust in HDP voters and liking Yavaş is not significant. These regression results imply that Kılıçdaroğlu had an advantage in terms of appealing to voters with an affinity for HDP. However, the response surface patterns displayed in (Panel A for Kılıçdaroğlu, Panel B for İmamoğlu) indicate that, for both candidates, the response patterns were akin to the X-centric (, Panel A) pattern, which indicates that the liking of both candidates was mainly driven by the X-axis (trust in CHP voters). However, when trust in HDP voters is very high, the liking scores of Yavaş are relatively lower at higher levels of trust in CHP voters, putting Yavaş in a disadvantaged position.

Figure 4. Response surfaces predicting respondents of rating of how much they like Kılıçdaroğlu (A), Imamoğlu (B), Yavaş (C). The X-axis indicates respondents’ trust of CHP voters and Y-axis shows respondents’ trust of HDP voters.

Table 3. Polynomial regression coefficients and surface parameters with trust in CHP voters and trust in HDP voters as predictors.

Following the analyses regarding the impact of affinity to CHP, IYIP, and HDP on the likeability of Kılıçdaroğlu, Imamoğlu, and Yavaş, we ran an RSA predicting respondents’ reported votes (Erdoğan vs. Kılıçdaroğlu) in the second round of the run-off elections from affinity with CHP and IYIP voters (). Accordingly, while affinity with CHP voters increased the probability of voting for Kılıçdaroğlu, affinity with IYIP voters had no significant main effect on the probability of voting for Kılıçdaroğlu. Additionally, the interaction between affinity with CHP voters and affinity with IYIP voters was such that the positive impact of affinity with CHP voters on the probability of voting for Kılıçdaroğlu was more substantial among respondents who had low affinity with IYIP voters. The RSA surfaces () likewise indicate that affinity with CHP voters was the driver of voting for Kılıçdaroğlu. Among respondents with lower levels of affinity with CHP voters and higher levels of affinity with IYIP voters, the probability of voting for Kılıçdaroğlu was only about %60.

Figure 5. Response surfaces predicting reported vote in the second round of the run-off elections erdoğan (1) and Kılıçdaroğlu (2). The X-axis indicates respondents’ trust in CHP voters, and the Y-axis shows respondents’ trust in IYIP voters. Higher values on the Z-axis mean a higher probability of voting for Kılıçdaroğlu.

Table 4. Polynomial regression coefficients and surface parameters with trust in CHP voters and trust in HDP voters as predictors and reported presidential vote (binary) as the dependent variable.

Discussion and conclusion

In 2023, Turkey found itself at a critical juncture as the nation embarked on a significant electoral event encompassing the parliament and the presidency, posing a formidable challenge to the established 21-year rule of the AKP under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Within the opposition, a sense of optimism prevailed, fuelled by underlying issues that eroded the credibility of the AKP in recent years. The latter part of the AKP’s prolonged tenure was marred by a persistent economic crisis, a predicament primarily attributed to President Erdogan’s steadfast insistence on an ‘unorthodox’ approach to reducing interest rates to fight inflation. This policy choice set a troublesome cycle of currency depreciation and inflation in motion, contributing significantly to the economic woes faced by the nation. Administrative lapses were added to the growing discontent in the aftermath of the 2023 earthquake. The mishandling of the post-earthquake situation further exacerbated existing concerns about the effectiveness and responsiveness of the government, setting the stage for a meaningful electoral contest.

Another pivotal reason behind the optimism within the opposition stemmed from the belief that the 2019 local elections could serve as a strategic blueprint for effectively challenging Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s dominance. Historically, the metropolises of Istanbul and Ankara were under the control of the AKP or its pro-Islamist predecessors for over two decades. Notably, in 1994, Erdoğan secured the majority of votes as the RP candidate for Istanbul Greater City Municipality, a win often considered a seminal moment in his political ascent.

Indeed, the 2019 local elections marked a significant departure from the historical trend. In a ground-breaking turn of events, the opposition not only managed to break the long-standing hold of the AKP in Istanbul and Ankara but also secured vital victories in other major cities across Turkey. This shift was attributed to a combination of factors, including the prevailing dissatisfaction with the economic situation. A crucial element contributing to this success was forming a strategic alliance among opposition parties, throwing their support behind candidates Ekrem İmamoğlu (for Istanbul) and Mansur Yavaş (for Ankara).

The success of this alliance during the local elections bolstered the confidence that it could be a formidable force in challenging Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on a national scale by 2023. Unlike past coalitions in Turkey that formed after elections, this alliance, established before the electoral contest, comprised six parties spanning the ideological spectrum. Notably, the Alliance had a proactive approach to developing comprehensive policy alternatives to address various issues, including economic concerns and constitutional reform. The distinctive nature of this alliance sets it apart from previous political collaborations in Turkey, creating a sense of anticipation for its potential impact on the broader political landscape.

One lingering issue revolved around the decision regarding a single joint candidate to secure the presidency. This challenging process ultimately resulted in the nomination of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of the CHP and the alliance’s largest party, as a candidate. Once on the brink of withdrawing, the IYIP, the second-largest alliance party suggested either Ekrem İmamoğlu or Mansur Yavaş as candidates. Despite their CHP affiliation, the IYIP and experts argued that they could better resonate with the right-leaning voter base within the alliance. While nominating Kılıçdaroğlu might seem strategically questionable, another vital factor was the candidates’ appeal to the substantial voter base of the Kurdish HDP, which, despite not being part of the alliance, could play a crucial role in Turkey’s potential second-round run-off election system.

Against the background of this intricate political context, our objective in this article has been to employ a novel analytical technique known as Response Surface Analysis (RSA) to assess the viability of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, Ekrem İmamoğlu, and Mansur Yavaş. In addition to analysing, using polynomial regressions, the main effects of voters’ affinity to each political party (i.e., CHP, IYIP, and HDP) on their liking of the three politicians, RSA also helps investigate the conjoint effects of party affinity on liking presidential candidates. In this context, this allowed us to explore the intricate relationships between trust in party voters of respective parties and liking for these three prominent politicians.

We observed that the positive association between liking for all candidates and trust in CHP and IYIP voters aligns with the conventional expectations. This suggests that respondents tend to favour candidates when their trust in the supporters of the respective parties is higher. However, as we discussed at the beginning of this article, ideally, in an alliance, we expect to observe patterns whereby affinity towards either party would increase a candidate’s likeability. To illustrate, consider IYIP voters with a low affinity for CHP. For the alliance to be strategically beneficial for a given candidate, even among IYIP voters with a low affinity towards CHP, a higher affinity with their party base should increase positive feelings towards that candidate. This is the pattern observed in the example in (XY-oriented interdependence). When we plotted interdependence between CHP and IYIP for each of the candidates, the candidate who seemed to benefit least from such XY interdependence was Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, and the candidate who appeared to benefit the most from such XY interdependence was Mansur Yavaş. This may indicate that Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu had low intrinsic appeal to the non-CHP members of the alliance or that the IYIP party’s campaign was not strong enough to mobilize the IYIP party voter base in favour of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. In either case, these results suggest that when considered from the point of view of the strategic suitability of the candidate for the alliance, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu was at a disadvantage, and Mansur Yavaş may have had an advantage in terms of mobilizing IYIP voters. These findings are corroborated by the analysis we ran regarding respondents’ votes in the second round of the run-off elections. Specifically, we observed that affinity with IYIP voters did not have a significant impact on the probability of voting for Kılıçdaroğlu.

Expanding the analysis to include trust in HDP voters introduces another layer of complexity. The lack of a significant positive relationship between trust in HDP voters and liking for Mansur Yavaş is both expected and underscores the fact that his appeal would be lower for voters with an affinity for HDP. From this perspective, both Kılıçdaroğlu and, to a lesser extent, Ekrem İmamoğlu stand out as more strategically suitable choices for mobilizing HDP voters. However, the CHP-centric response patterns for both Kılıçdaroğlu and İmamoğlu reveal that their likeability is predominantly driven by trust in CHP voters, indicating that the influence of affinity on HDP voters is only secondary.

It is important to note that despite the use of probability sampling for the recruitment of the participants for the data we utilized in our analysis, our dataset overrepresented CHP voters and underrepresented voters of AKP, IYIP, and HDP. Part of the reason for this is the attrition of respondents over the three waves of data collection; however, even in the first wave of the study, the distribution of voting intentions deviated from the election results. Nevertheless, our findings underscore the multifaceted nature of voter preferences in the 2023 elections in Turkey, emphasizing the need to consider the intricate interdependencies between trust in voters of different parties. The distinctive response patterns of each candidate highlight the importance of tailoring political strategies to leverage strengths and address vulnerabilities, with implications for a broader political landscape.

From a broader theoretical perspective, our findings underline the crucial importance of ideological proximity in forming successful electoral alliances. Finding a presidential candidate who appeals to all alliance members becomes difficult when such proximity is absent among alliance members. The presence of significant constituencies that a candidate could target also complicates the calculus of the candidate choice for the alliance.

Ethics Approval and Compliance

Ethical approval for this study/case/case series was obtained from Koç Üniversitesi Committee on Human Research (2021.348.IRB3.150). Online informed consent was obtained from participants of the study.

Author Bios.docx

Download MS Word (12.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2024.2324523

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lemi Baruh

Lemi Baruh Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, Annenberg School for Communication, 2007 is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Communication and Arts at the University of Queensland and an honorary Associate Professor at Department of Media and Visual Arts, Koç University. He is the co-founder of the Social Interaction and Media Lab at Koç University, Istanbul. His research spans various topics, including the effects of social media on interpersonal attraction, surveillance, online security, privacy in online environments, and the role of media in shaping public opinion.

Ali Çarkoğlu

Ali Çarkoğlu is currently a professor of political science at Koç University. He received his Ph. D. at the State University of New York-Binghamton in 1994. He previously taught at Boğaziçi and Sabancı Universities in Istanbul. He was a visiting professor in 2017-2018 at the Center for Political Studies-Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan and was a resident fellow in 2008-2009 at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS). His areas of research interest include voting behavior, elections, public opinion, and party politics in Turkey. His publications appeared in the International Journal of Communication, Political Communication, Electoral Studies, Political Behavior, European Political Science Review, Democratization, European Journal of Political Research, International Journal of Press/Politics, Environmental Politics, Turkish Studies, New Perspectives on Turkey, South European Society and Politics, Middle Eastern Studies, Political Studies and in edited volumes.

Notes

1. On analytical properties of run-off elections see Bordignon (Citation2016), Bouton et al. (Citation2022). On comparative evaluations of the run-off systems see Alcántara (Citation2012), Blais and Indridason (Citation2007), Passarelli and Bergman (Citation2023).

2. See also Blais and Indridason (Citation2007), Griebeler and Resende (Citation2021).

3. On coalition politics in Turkey see Ergüder (Citation1990), Kalaycioğlu (Citation2016), Kumbaracıbaşı (Citation2018).

4. On the consequences of new election law in 2018 elections see Arslantaş et al. (Citation2020), Çarkoğlu and Yıldırım (Citation2018), Evci and Kaminski (Citation2021).

5. See coverage by al-Jazeera at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/06/turkey-istanbul-set-histor ical-rerun-mayoral-vote −190,618,121,542,677html.

6. Mediterranean (Adana and Antalya) and southeastern Anatolia (Diyarbakır and Gaziantep) regions had two provinces.

7. See Enelow and Hinich (Citation1984) on spatial models of voting and Çarkoğlu and Hinich (Citation2006) for an estimate of political space for Turkey.

8. On polarization in Turkey see Somer (Citation2019). Wagner (Citation2021) places Turkey amongst the most highly polarized countries in a comparative setting.

References

- Aaldering, L., T. Van Der Meer, and W. Van Der Brug. 2018. Mediated leader effects: The impact of newspapers’ portrayal of party leadership on electoral support. The International Journal of Press/politics 23, no. 1: 70–94. doi:10.1177/1940161217740696.

- Alcántara, M. 2012. Elections in Latin America 2009-2011: A comparative analysis. Kellogg Institute for International Studies. Working Paper 386.

- Arslantaş, D., Ş. Arslantaş, and A. Kaiser. 2020. Does the electoral system foster a predominant party system? Evidence from Turkey. Swiss Political Science Review 26, no. 1: 125–43. doi:10.1111/spsr.12386.

- Başkan, F., S.B. Gümrükçü, and F. Orkunt Canyaş. 2022. Forming pre-electoral coalitions in competitive authoritarian contexts: The case of the 2018 parliamentary elections in Turkey. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 24, no. 2: 323–43. doi:10.1080/19448953.2021.2006006.

- Bittner, A. 2011. Platform or personality? The role of party leaders in elections. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Blais, A., and I.H. Indridason. 2007. Making candidates count: The logic of electoral alliances in two-round legislative elections. The Journal of Politics 69, no. 1: 193–205. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00504.x.

- Blais, A., L. Massicotte, and A. Dobrzynska. 1997. Direct presidential elections: A world summary. Electoral studies 16, no. 4: 441–55. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(97)00020-6.

- Blumenstiel, J.E., and T. Plischke. 2015. Changing motivations, time of the voting decision, and short-term volatility – the dynamics of voter heterogeneity. Electoral Studies 37, no. March: 28–40. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2014.11.003.

- Bordignon, M., T. Nannicini, and G. Tabellini. 2016. Moderating political extremism: Single round versus runoff elections under plurality rule. American Economic Review 106, no. 8: 2349–70. doi:10.1257/aer.20131024.

- Bouton, L., J. Gallego, A. Llorente-Saguer, and R. Morton. 2022. Run-off elections in the laboratory. The Economic Journal 132, no. 641: 106–46. doi:10.1093/ej/ueab051.

- Çarkoğlu, A., and M. Hinich. 2006. A spatial analysis of Turkish party preferences. Electoral Studies 25, no. 2: 369–92. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2005.06.010.

- Çarkoğlu, A., and K. Yıldırım. 2018. Change and continuity in Turkey’s June 2018 elections. Insight Turkey 20, no. 4: 153–82. doi:10.25253/99.2018204.07.

- Downs, A. 1957. An economic theory of democracy. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Duverger, M. 1954. Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state. London: Methuen.

- Edwards, J.R. 2002. Alternatives to difference scores: Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology. In Measuring & analyzing behavior in organizations: Advances in measurement & data analysis, ed. F. Drasgow and N. Schmitt, 350–400. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Enelow, J.M., and M.J. Hinich. 1984. The spatial theory of voting: An introduction. Vol. 1. Cambridge (Cambridgeshire): Cambridge University Press.

- Ergüder, Ü. 1990. Coalition governments and political stability: Turkey and Italy. Il Politico 55, no. 4: 673–89.

- Esen, B., and S. Gumuscu. 2016. Rising competitive authoritarianism in Turkey. Third World Quarterly 37, no. 9: 1581–606. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1135732.

- Esen, B., and S. Gumuscu. 2019. Killing competitive authoritarianism softly: The 2019 local elections in Turkey. South European Society & Politics 24, no. 3: 317–42. doi:10.1080/13608746.2019.1691318.

- Evci, U., and M.M. Kaminski. 2021. Shot in the foot: Unintended political consequences of electoral engineering in the Turkish parliamentary elections in 2018. Turkish Studies 22, no. 3: 481–94. doi:10.1080/14683849.2020.1843443.

- Ferreira Da Silva, F. 2018. Fostering turnout? Assessing party leaders’ capacity to mobilize voters. Electoral Studies 56: 61–79. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2018.09.013.

- Garzia, D. 2013. Can candidates’ image win elections? A counterfactual assessment of leader effects in the second Italian republic. Journal of Political Marketing 12, no. 4: 348–61. doi:10.1080/15377857.2013.837303.

- Golder, S.N. 2006. The logic of pre-electoral coalition formation. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

- Griebeler, M.D.C., and R.C. Resende. 2021. A Model of electoral alliances in highly fragmented party systems. Journal of Theoretical Politics 33, no. 1: 3–24. doi:10.1177/0951629820963182.

- Kalaycioğlu, E. 2016. The conundrum of coalition Politics in Turkey. Turkish Studies 17, no. 1: 31–38. doi:10.1080/14683849.2015.1136087.

- Kenyon, P. 2022. Turkey’s attempt to ban an Erdogan rival from politics is drawing a backlash. NPR. December 21. https://www.npr.org/2022/12/21/1144466364/turkey-politics-erdogan-istanbul-mayor-ekrem-imamoglu

- Koppensteiner, M., and P. Stephan. 2014. Voting for a personality: Do first impressions and self-evaluations affect voting decisions? Journal of Research in Personality 51: 62–68. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2014.04.011.

- Kumbaracıbaşı, A.C. 2018. Theories of coalition government formation and party politics in Turkey. In Party politics in Turkey, ed. S. Sayarı, P. Musil, and Ö. Demirkol, 157–78. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lobo, M.C., and F.F. da Silva. 2018. Prime ministers in the Age of Austerity: An increase in the personalisation of voting behaviour. West European Politics 41, no. 5: 1146–65. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1380354.

- Marsh, M. 2007. Candidates or parties? Objects of electoral choice in Ireland. Party Politics 13, no. 4: 500–27. doi:10.1177/1354068807075944.

- Metz, R., and B. Plesz. 2023. An insatiable hunger for charisma? A follower-centric analysis of populism and charismatic leadership. Leadership 19, no. 4: 318–38. doi:10.1177/17427150231167524.

- Morse, Y.L. 2012. The era of electoral authoritarianism. World Politics 64, no. 1: 161–98. doi:10.1017/S0043887111000281.

- Nai, A., J. Maier, and J. Vranić. 2021. Personality goes a long way (for some). An experimental investigation into candidate personality traits, voters’ profile, and perceived likeability. Frontiers in Political Science 3, no. March: 636745. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.636745.

- Nestler, S., S. Humberg, and F.D. Schönbrodt. 2019. Response surface analysis with multilevel data: Illustration for the case of congruence hypotheses. Psychological Methods 24, no. 3: 291–308. doi:10.1037/met0000199.

- Passarelli, G., and M. Bergman. 2023. Runoff comebacks in comparative perspective: Two-round presidential election systems. Political Studies Review 21, no. 3: 608–24. doi:10.1177/14789299221132441.

- Popescu, M., and T. Gábor. 2021. The Hungarian opposition primaries of Fall 2021: Testing the feasible in an authoritarian regime. Studia Politica – Romanian Political Science Review 21, no. 2: 409–33.

- Sarah, H., S. Nestler, and M.D. Back. 2019. Response surface analysis in personality and social psychology: Checklist and clarifications for the case of congruence hypotheses. Social Psychological & Personality Science 10, no. 3: 409–19. doi:10.1177/1948550618757600.

- Sartori, G. 1994. Comparative constitutional engineering. New York: New York University Press.

- Schönbrodt, F.D. 2015. RSA: An R package for response surface analysis. https://cran.r-project.

- Schönbrodt, F.D., S. Humberg, and S. Nestler. 2018. Testing similarity effects with dyadic response surface analysis. European Journal of Personality 32, no. 6: 627–41. doi:10.1002/per.2169.

- Shephard, M., and R. Johns. 2008. Candidate image and electoral preference in Britain. British Politics 3, no. 3: 324–49. doi:10.1057/bp.2008.8.

- Somer, M. 2019. Turkey: The slippery slope from reformist to revolutionary polarization and democratic breakdown. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no. 1: 42–61. doi:10.1177/0002716218818056.

- Stoermer, S., J. Lauring, and J. Selmer. 2022. Job characteristics and perceived cultural novelty: Exploring the consequences for expatriate academics’ job satisfaction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 33, no. 3: 417–43. doi:10.1080/09585192.2019.1704824.

- Turchenko, M., and G.V. Golosov. 2023. Coordinated voting against the autocracy: The case of the ‘smart vote’ strategy in Russia. Europe-Asia Studies 75, no. 5: 820–41. doi:10.1080/09668136.2022.2147485.

- Utych, S.M., and C.D. Kam. 2014. Viability, information seeking, and vote choice. The Journal of Politics 76, no. 1: 152–66. doi:10.1017/S0022381613001126.

- Vecchione, M., G. Caprara, F. Dentale, and S.H. Schwartz. 2013. Voting and values: Reciprocal effects over time. Political Psychology 34, no. 4: 465–85. doi:10.1111/pops.12011.

- Wagner, M. 2021. Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies 69: 102199. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199.