ABSTRACT

In the realm of multi-species ecologies and relationships, there are often unseen dynamics, unheeded threats and unacknowledged suppressions. The objectives of the research were to develop an experimental approach to expose some of the hidden, overlooked or ignored aspects of specific watery environments, and hidden violence of associated human-animal relationships and to reflect on the role of creative methods of activation and empathy-building in such scenarios. Using a trans-disciplinary geopoetic approach inspired by dark ecology thinking and methods based on creative provocations, this experiment offers insights into relationality around two water-connected species, the European Eel and the Black-legged Kittiwake. Adaptations of everyday objects were created and used within a performative market-stall installation to engage people in conversation. Our work illustrates the potential for creative provocation as a method within ecology-focussed enquiry, harnessing the productive tension between what is regarded as scientific ‘fact’ and creative/imaginative activations.

Kittiwake; Eel; Dark Ecology; Geopoetics; Water Landscape; Hydrocitizenship

1. Introduction

The complex entanglements between natural processes, human and non-human species generate a myriad of cultural practices, meanings, associations and representations. These representations include content from ecological observations which are useful in understanding the dynamics of cultural and landscape change over time. Recognition of the vital importance of multi-species ecological awareness has led to an appreciation of the potential to gain deeper and wider knowledge and understanding of ecological processes, activated through approaches such as transdisciplinary methods, citizen science, creative practice and inter-species encounters (Arts et al. Citation2017; Post and Pijanowski Citation2019). Contemporary challenges can manifest as wicked environmental problems (Morton Citation2016; Pihkala Citation2018; Post and Pijanowski Citation2019; Wilson Citation2016), including species collapse (Haraway Citation2015), Anthropocene thinking (Crutzen Citation2002, Citation2006), the impacts of intra-species inequality (Malm and Hornberg Citation2014), increasing environmental variability (Verboom et al. Citation2010) and climate catastrophe (Wallace-Wells Citation2019). While common understanding and media reporting of the science behind these problems is patchy (Legagneux et al. Citation2018), popular concern is evidenced through widespread support for contemporary activist movementsFootnote1 (Lancet Planetary Health Citation2019).

A key issue highlighted by researchers and activists is non-human species decline, particularly biodiversity loss and extinction, and large-scale habitat degradation as a result of the activities of humans (Hall., Jordaan and Frisk Citation2011; National Biodiversity Network Citation2019). Biodiversity collapse is evidenced by the statistics collated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Currently there are more than 98,500 species on the IUCN Red List, with more than 27,000 threatened with extinction, including 40% of amphibians, 34% of conifers, 33% of reef-building corals, 25% of mammals and 14% of birds (IUCN Citation2019). The Red List Index (RLI) demonstrates this general decline; for example, numbers of birds in the critically endangered category rose from 168 to 224 between 1996 and 2019, and 157 to 489 in the case of fish species over the same period (IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Citation2019). The World Wide Fund for Nature suggests that the rapid loss of species presently occurring is between 1,000 and 10,000 times higher than the natural extinction rate (WWF Citation2019). The continuing lack of action to effectively address these issues by governments and supra-national bodies has been attributed to the power of corporate interests and to lack of vision, as well as the resistance of policy leaders and governments to action (Novacek Citation2008). Susanna Lidström and Greg Garrard (2014) indicate that decision-making to achieve greater environmental sustainability is as much about overcoming affective obstacles as scientific or political barriers. Research also indicates that tools to address species decline include public pressure through raised awareness, and activism to influence political will, as well as developing new and often experimental approaches in protection, conservation and management of landscapes, such as nature-based solutions and rewilding (Keesstra et al. Citation2018; Pereira and Navarro Citation2015). However, the complexities of the arguments and figures relating to biodiversity loss, and the intertwining of ecological processes and human activities, hinder the identification of clear paths towards good environmental planning (Keesstra et al. Citation2018) and for achieving multi-species environmental justice (Haraway Citation2018).

Although there is a recent surge of nature writing addressing human/multi-species entanglements, there is little acceptance in contemporary policy-making of what Michael Novacek (Citation2008) describes as inspirational, or creative approaches that can help build connections between people and natural processes. However, it has long been recognised that encouraging an appreciation of wonder towards the mysterious rhythms of the natural world (Carson Citation2011) and the telling of nature-based stories (Bowman Citation2007; Cronon Citation1992) have untapped potential for encouraging public involvement in critical ecological issues, based not on ignoring or avoiding difficult issues, but, as suggested in Donna Haraway’s (2018) book on ‘Staying with the Trouble’. This paper describes a research process which sought to develop a creative and provocative approach to the issue of people’s disconnection from ecological processes. In testing this approach, we investigated two particular species related to water – the Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) () and the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) () – both of which have a strong association with the two river-port cities of Newcastle and Bristol in the UK.

2. Establishment of enquiry objectives

The two objectives of the research were stimulated by the contexts described above, and by the consequent ambition to reveal hidden human/more-than-human relationships. Investigating non-western cultures, David Abram (Citation1997) poetically explores the theme of detrimental human alienation from reciprocal engagement with elemental natural dynamics. Bas Pedroli, Pinto-Correia and Cornish (Citation2006) identified the disjuncture between westernised human behaviours and the arbitrary notion of the environment which ‘allows us to conveniently ignore the hidden costs’, and how, whilst immersed in nature, we nevertheless ‘act as though we are somehow separated from it’ (426). Western-dominated capitalist/extractive industrialisation both hides and increases the hidden costs, which include adverse impact on species, including people and communities, who are not amongst the privileged few. Implicated in these costs is a hidden violence in human/more-than-human relationships, amplified by people’s lack of understanding of many species (Naess Citation1977), and also a lack of recognition that humans are hopelessly entangled in the mesh of life (Morton Citation2010a).

The first objective of the research was to develop an experimental approach to expose some of the hidden, overlooked or ignored aspects of specific local environments, and hidden violence of human-animal relationships with particular reference to water. The second objective was to test the role of creative methods of evocation, provocation and empathy -building in such an agenda, to prompt fresh connections with local riverine landscapes based on thinking and feeling, with a particular focus on ecological issues. These objectives were conceived as requiring braided strands of activity and content, involving associative body, mind, myth, memory, waste, food, emotion, politics, etc. plus the understandings of the water ecology that formed the basis of the study. The objectives recognise the need to transform existing data into new knowledge (a key issue identified by Pedroli, Pinto-Correia and Cornish Citation2006) rather than establish new primary biophysical data. Therefore, in the conceptualisation, we began thinking about how existing data could be looked at, and applied, in different ways.

3. Theoretical approach development: water and dark ecology

The academic literature relating to water can be found across the disciplines in natural sciences, creative arts, engineering and humanities. There is a clear global political and policy focus on the importance of the many aspects of water and water security, in particular as a human right recognised within the UN Sustainable Development Goals (HLPW Citation2018). What is often forgotten within a functional focus on water security are the myths, legends, spiritual and intangible cultural associations relating to water which can be found in every culture. These interpret and give meaning to the physical presence and interactions between humans and water in landscapes, and are often expressed in multi-sensorial and associative terms (Jones, Gorell-Barnes and Lyons Citation2019; Nagy Citation1985-86). Ivan Illich (Citation1986) describes how industrialisation brought with it the view of water as stuff out of a tap. We have lost what Illich calls ‘the water of dreams’ – what we have left is just H₂0 – ‘a social creation of modern times, a resource that is scarce and that calls for technical management’ (76). Increasingly, digital media outlets and contemporary writing by naturalists as well as academic authors reflect the loss of spiritual, sensory and meaningful connections with water (Bachelard Citation1983; Chen MacLeod and Neimanis Citation2013; Deakin Citation2014; France Citation2001; Strang Citation2004). Illich mourned the lack of ‘opportunities to come in touch with living water’ (1986, 76), which is recognised as an increasing problem in designing for water in the public realm, exacerbated by a lack of good information and a litigious culture in western environmental planning (Trammel et al. Citation2018). Water is widely represented in the literature as both central to survival and the substance that makes this planet liveable (Younger Citation2012), but also something that is dangerous, frightening and unpredictable and has the instrumental qualities described by Illich.

In reviewing the literature, we were particularly interested in exploring a multi-faceted presentation and communication of ecological information concerning water in ways that might lead to novel understandings and questioning. The concept of dark ecology was particularly helpful. Developed by Timothy Morton (Citation2009) this suggests that ecological awareness is strange and uncanny rather than obvious. Building on a concept of the interconnectedness of all living and non-living things, Morton (Citation2016) proposes a new mindset where the irony, ugliness, and horror of ecology is expressed. He goes on to compare this to the film noir idea whereby the observer becomes implicated in the action of the film (Citation2010b). He describes how such an approach pushes the viewer, stating that ‘ugliness and horror are important because they compel our compassionate coexistence to go beyond condescending pity’ (7). Also useful was Viktor CitationShklovsky’s ([1917]1998) proposed concept of ostranenie where objects are made unfamiliar in order to understand them better. Frank Kessler (Citation2010) interprets ostranenie by suggesting that the purpose of art is to make everyday objects unfamiliar and thereby we see things that were unseen through the veil of familiarity. Similarly, Morton’s (Citation2016) description of ecognosis (ecological awareness) derived from both natural science and humanities thinking is an important part of his concept of dark ecology. This suggests a looping process where exposure to the unfamiliar, strange or unsettling, may in turn prompt new insights into complex relationships between all species. In other words, by exposure to provocative alternative views and inputs, the perceptions of human and non-human relationships can be transformed.

Expression of such knowledge is also found in creative and particularly geopoetic practice (Lyons Citation2018; Magrane and Jonson Citation2017). A geopoetic creative approach fuses rational and imaginative perspectives in order to reveal hidden dimensions of human/non-human relationships. It is understood to be an interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary approach where the exploration is in the ‘liminal zone between science, society, ecology and art’ (Lyons Citation2018, 5). Haraway suggests that inventive practices involving play, storytelling and joy can, through apparently contradictory approaches using creative light-heartedness, engage people in exploring and depicting serious environmental problems (Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2019). She argues that these experiments are needed if multispecies environmental justice is to be achieved and that problems arise in societies and situations when there is a lack of inventive thought and imagination. Haraway exemplifies this through her own work, which commonly uses a complex intertwining of scientific evidence, philosophy, allusion, creative imagery and storytelling that harnesses diverse creative works of others. An example is the Crochet Coral Reef project by Christine and Margaret Wertheim working with over ten thousand participants around the globe. Haraway identifies the key role of playfulness, fantasies and speculative fabulation in creating crocheted models of vulnerable reef systems based on mathematics, biosciences, and arts to foment ‘active caring through practical crafted beauty’ (Haraway Citation2019, 568). Eric Otto (Citation2012) identifies transformative environmental movements, particularly those that focus on the need to change attitudes, habits and behaviours that cause environmental damage. His thesis is that dystopian writing which challenges the imagination can help people understand and grasp the seriousness of the global environmental crisis in a way that presentation of hard scientific facts does not. In particular, the ways in which estrangement and extrapolation are used in such texts ‘compel readers towards critical reflection on seemingly invisible everyday attitudes and habits’ (Ibid, 7).

Brian Wattchow (Citation2013) identifies four signposts to a place-responsive pedagogic approach which may be useful in considering connecting (or reconnecting) people with water. First is the development of perceptual acuity towards natural phenomena; second, is using the power of place-based stories and narratives (Waller and Flader Citation2010), particularly ones with cultural significance such as those which map water features in the landscape and which help build the invisible threads that connect people to places and features that are visible; third, by blending the first two approaches and through immersion in a place (sensory immersion and narrative), or working with people in places, listening, responding and reflecting in an attentive manner; fourth, representation of the learning process in text, film, design, etc. as a process of cultural meaning-making that will change over time. Lidström and Garrard’s analysis identifies the potential of creative narrative text to capture the sensory relations and responses to natural environments – or the complexities of the ‘inner and outer environments’ (Citation2014, 43). They suggest that creative responses can provide ‘open-ended, multiple and even contradictory levels of meaning’ and that this ‘makes them especially interesting to look to for images that challenge established patterns of environmental thought and address complex, labyrinthine twenty-first century human-environment relations between local and global, social and ecological, perception and imagination.’(Ibid 37). In turn, we were interested in how provocations using unsettling narratives – and imagery – could help elicit reactions and personal stories about ecological interdependencies. In our project, we interpreted these concepts in terms of five key fascination premises which we used as a framework for reflection and analysis ().

Table 1. Fascination Framework

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Transdisciplinary approach using experimental provocation

Our aim was to develop a model which embraced a belief that perceptions, reactions and values based on confusion, disturbance and revulsion could be used to both attract and repulse people, and to encourage reflection or provide fascination. We used a case study approach sited in two areas in the UK – the River Avon, Bristol, and the River Tyne at Newcastle. The experimental transdisciplinary process incorporated social science relational and creative arts-based methods and portrayals of situated multi-species narratives. While understandings of ‘transdisciplinary’ research and integrative working vary considerably (Tress et al. Citation2005; Ostrom and Walker Citation2003), transdisciplinary – or more-than-disciplinary – allows for working not only within the interstices of disciplines (interdisciplinary), but also so that both ‘insiders’ (those with experiential or indigenous knowledge) plus ‘outsiders’ (those with expert and other knowledge) build new knowledge together (Roe and Stead Citation2021f). The focus on water was enacted particularly through revealing the cultural significance and meanings of two species that were also identified on the Red List of endangered species. The sources of information and evidence included current and archival documents, texts, images and other representations (online and paper-based), research notes following conversations with a range of respondents (see below) and the reflective observations of researchers following collaborative activities.

5. Methodologies

5.1. The strategy for research was based on four main stages

Stage 1: Immersive mapping

As researchers, we mapped the literature and were immersed in the issues which were revealed through the literature, conversations and reflections. The focus was on water-based ecological processes; the meshing of relationships and entanglements as seen through an examination of species-based stories, with a focus on two locally significant signature species, the Black-legged Kittiwake and the European eel, alongside the human socio-cultural layers. Both species are experiencing plummeting global populations: the European Eel is critically endangered, and the kittiwake is identified as vulnerable (Henderson et al. Citation2012; Jacoby and Gollock Citation2014; JNCC Citation2017; BirdLife International Citation2018; RSPB Citation2017; Wilson and Venerata Citation2019). An extensive literature and archival review and analysis was carried out, including a wide range of secondary sources that provided statistical data, current knowledge on the life-cycles and species characterisation information. We also examined fictional literature and natural history narratives that provided cultural information on attitudes, beliefs and meanings concerning the species. Birds, including the kittiwake, have in recent years been the focus of a considerable creative and humanities-based literature (Armitage and Dee Citation2009; Couzens Citation2017; Doughty Citation1974; Merritt Citation2016) as well as natural sciences (Coulson Citation2002, Citation2011; Hátún, Olsen and Pacariz Citation2017). The focus on both species – but eels in particular – has addressed the topic of cultural connection, including place-names, myths and folklore (Cocker and Mabey Citation2005; McCarthy Citation2014; Makel Citation2011; Nagy Citation1985-86; Prosek Citation2011); literature, art, poetry (Kuroki, Van Oijen and Tsukamoto Citation2014; Reading Citation1983), and particularly food cultures (Cox Citation1866; Kitchiner Citation1817; Righton and Roberts Citation2014; Schweid Citation2004; Simon Citation1942, Citation1944; Tsukamoto and Kuroki Citation2014), including marine food (Probyn Citation2016; Woolgar Citation2003).

These species were selected following discussions within a wider research project – Towards Hydrocitizenship – which focused on people’s relationship with water environments. We identified a need to address gaps in understanding concerning the sensory and associative, conscious and unconscious explorations of people’s relationship with water and species. Eels are diadromousFootnote2 and both species connect fresh and saltwater through reliance on river/freshwater and sea/saline habitats, with both having extensive Atlantic journeys as part of their life-cycles (Davies et al. Citation2004; Hoestlandt Citation1991). This provided the basis for thinking at both the local and global scales. It emerged that a very visceral bodily reaction based on smell and water, and perceptions of darkness and decay might be linked to the eel realm, while kittiwakes represent perceptions of light and air, immediate and enduring sound-memory and a sprite-like identity. Human geographies of the two river corridors were juxtaposed and entangled with the undercurrents of eel ecologies. The River Tyne’s site-specific relevance of the kittiwake was analysed to expose some of the cultural significance, meanings and mythologies of species and their long-durational – and sometimes problematic – interaction with people.

Material was also gathered through discussion with interest groups and experts such as the Sustainable Eel Group and the Natural History Society of Northumbria. Observational information was obtained through site visits, which included a number of river journeys on foot and by boat, where we held discussions with species experts on current issues, cultural histories and current evidence relating to the species of interest. Emotional responses by researchers and interviewees were also discussed and recorded as field notes.

The examined archival material included sources such as recipe books, naturalist treatises, visual representations and descriptions of traditions, incidents and practices related to the species. The information was synthesised into characterisations of the two species and their ambiguous, sometimes disturbing, cultural associations.

5.1.1. Stage 2: Creative interpretation

Analysis of the primary and secondary material was consolidated through a series of creative exchanges and interpretations expressed in written form (short papers relating to species characterisation; migration, cooking/eating/hunting) and verbal/written exchanges. Through the creation of the species stories which incorporated current scientific knowledge, cultural associations and historical evidence of interactions between the species and humans in relation to water and landscapes, the focus on fascination and unsettling guided the creative responses and the production of imaginative printed assemblagesFootnote3 and performative installations.Footnote4

5.1.2. Stage 3: Creative intervention and dialogues

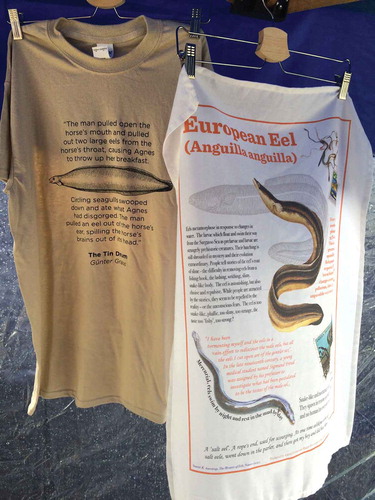

Expressions of the species’ stories and our own emotional responses were examined and expressed in written form, including blogs, images, and the development of treatments for the production of everyday printed items (six tea-towel and eight T-shirt designs – see ). The tea-towel format, as commonly used, has standard dimensions and material composition. It is an ordinary item that has developed from a domestic necessity to an essential designer kitchen accessory. While familiar and often overlooked, it is also a container of concise messages and stories in both visual and textual form. Commonly, these are pithy observations, recipes and souvenir images of attractions and tourist sites. Our objective in using this form for part of the creative installation was to encourage a double-take by the observer based primarily on the ostranenie concept (see , above). What you think you see, is perhaps not what you get. By extension, we used the T-shirt format because it is commonly recognised as providing opportunities for self-expression, advertising, souvenir messages, and protests. T-shirts provide low-cost wearable art and while they often exhibit immediate messages, our designs aimed to provoke a second glance and perhaps a second thought.

A concept of interaction, evocation and provocation through a market-stall installation was developed and sited in harbourside markets in each of the two locations (Bristol and Newcastle) (). As public spaces, markets provide the opportunities for casual interaction and conversation (Cattell et al. Citation2008) that we were looking for. Presenting tea-towels and T-shirts in a staged manner, the aim was to mimic a genuine merchandise-selling outlet, but also to disrupt expectations through the hybrid or mutant conflation of both informative and disturbing content. Two initial day-long markets provided opportunities to display/exhibit and actually sell the items (merchandise) and by doing so, engage in provocations or conversations about the species’ stories portrayed and people’s own stories and reactions to the intervention. The use of familiar domestic-intimate (tea-towels) and worn-intimate (T-shirts) objects in a common public realm or market scene aimed to unsettle by stealth. Summaries of the conversations were recorded as field notes. These were followed up by public exhibitions and conversations in three further locations.

5.1.3. Stage 4: (Analysis and discussion)

Analysis of the market-stall performative installations was carried out to identify themes within the stories/conversations and reflections on the spontaneous responses to the stall as a creative scenographic intervention.

6. Findings and analysis

The findings of the research were collated at Stage 2 (species characterisation) and Stage 4 (market-stall installation conversations). The findings of the species characterisation were synthesised and then images and text arranged, through a co-creative process, to produce the tea-towel designs. The text characterisation captured both the scientific data and the associations and meanings of the human interactions and emotional responses to the two species. Quotations and images were also selected from these compilations for the creation of the T-shirt designs, in conjunction with Nick Hand of the Letterpress Collective () and an illustrative exhibition booklet printed (Lyons, Roe and Hand Citation2017).

The initial findings provided a rich opportunity for creative response. Both the kittiwakes of the River Tyne and the eels of the River Severn/Avon travel long distances by, with, from and in water. They rely on water and both spend little time on land. The cultural associations are rich but indicate that perception of them can be described as ambiguous or existing in liminality (Szakolczai Citation2009); (Thomassen Citation2006); (Turner Citation[1969] 1991). The associations and stories surrounding each are very different, as indicated through the creative expressions of our exploration. Eels were once abundantly present in many rivers of the UK, but are now rare, and endangered by the impacts of human intervention in their habitat, particularly pollution, wetland drainage, river dams and other obstructions which mean they cannot complete their 4,000 mile journey from the Sargasso Sea to travel up rivers to grow to maturity, and then back down rivers to spawn. The kittiwakes that nest on the Tyne Bridge and some nearby buildings are more immediately obvious to visitors than eels within rivers. The kittiwakes have been fiercely defended and studied by an active community of naturalists and locals who watch and record kittiwake information. While the local council spends scarce financial resources clearing the pavement around nesting sites of guano droppings, there is also recognition of the role these birds play in relation to the identity of the River Tyne and the city of Newcastle, now recorded through the live webcam of the local Wildlife Trust.

6.1. Street market provocation

During the Street Market creative provocations, the market stalls were established to fit in with the familiar market streetscape in both Bristol and Newcastle. The riverside locations of both provided visual and sensory connections with the water as well as the market scene. Passers-by were attracted to buy the goods and in a number of cases these were purchased for others, for example a Newcastle woman with her son bought the ‘Kittiwake Decline’ t-shirt for her husband, because ‘he likes things that mean something’. The attraction was for all ages, in groups, couples and families (), and we observed that a number of people peered at the stall, walked past and then turned around and returned to look more closely and engage in conversation. When asked why they were interested, it was often an attraction to eels in particular: a family on the Newcastle Quayside said: ‘We like eels!’ People were initially attracted by the visual objects to take a closer look with a subsequent wide variety of reactions from confusion, disgust ‘oh that’s horrible!’ (woman at the Bristol Harbourside Market), to interest in the overall concept, the project and the research. Some found the ambiguity of the stall, the images and our presence (not there for commercial reasons, or as activists, but as researchers) initially difficult to understand, but also intriguing. During conversations, people commonly volunteered their own stories and often spent a considerable time in conversation with us and with others looking at the stall: As a Newcastle man and woman bought a kittiwake tea-towel they talked about their knowledge of the link between the millinery industry and collecting birds at Flamborough Head (Yorkshire). In another case a French woman, who bought an Eel Migration tea-towel, talked at length about her memories of her French grandmother going to the fish market in Marseilles to buy eels to take home to cook. She remembered her experience of Marseilles and the Camargue as a place rich in eels, flamingos and horses.

7. Discussion and conclusions

Morton’s concept of dark ecology (Citation2009, Citation2016) provided an important and useful focus for our work, particularly as a basis for our interpretation of shadowy, ambiguous and slippery cultural associations/meanings. Our findings revealed the understanding that people’s relationships with species and landscapes are intricate, interconnected and reflect physical, cultural and emotional change and interactions. These are constantly changing attributes, with relationships and environmental conditions in a constant state of flux. Many conversations were about the half-remembered and ambiguous associations that the merchandise creations prompted in the passers-by.

Traditional nature writing is generally (but not always) reflective of a warmth in feeling, or golden memories and experiences (e.g. Waterton Citation1838) which seem to cherry-pick the realities of ecological processes and are primarily about natural science (Farber Citation2000). One of key importance to focus on the darker side is Rachel Carson’s work, Silent Spring (Citation1962) which has become highly influential globally, changing popular environmental thinking and public policy. While the research indicated people’s sense of wonder towards the natural world in the associations of species we examined, the understanding of the state of environmental problems and particularly biodiversity decline, as well as detailed knowledge of particular locally-relevant species, was poor.

The process of deliberately intertwining the scientific with the emotional and sensory (a geopoetic approach) revealed stories about changing cultures, uses and the shaping of both human behaviours and landscapes. It disclosed a rich history of these species and their relationship to human scarcity, prosperity, skills, meanings, traditions, changing tastes and fashions. Devising ways to portray this complexity provided a response to the need to develop images to ‘help us make emotional sense’ (Lidström and Garrard Citation2014, 36) of wicked problems such as climate change and biodiversity loss (Pihkala Citation2018). Our work indicates that provocations which instigate personal expression of, and opportunities to consider, a common heritage of eco-relationships may help people towards more activist thinking rather than the eco-anxiety paralysis reported by Pihkala (Citation2018). This thinking may be reflected by increasing concepts of darkness emerging (e.g. Macfarlane Citation2019), the Dark Mountain Project Footnote5 and the recent eruption of popular activity related to existential questions, particularly the climate emergency.

Our research indicates that the fascination approach resonated with the present zeitgeists of lifting the lid on the idealisation of nature and providing a more realistic portrayal of the state of biodiversity loss, animal behaviour and relationships and human/non-human histories. However, it also side-stepped the common contemporary mode of doom and gloom in policy and media. Morton (Citation2016) and Haraway (Citation2018) suggest that we need to harness the darkness and violence of our relationships to other species rather than allow these to remain hidden; and that using a dose of reality in a creative form may be a more constructive strategy.

Our merchandise creations provoked considerable reflection between ourselves and in/with others, and indicated that using discomfort or making what seems familiar into that which is strange or uncanny (ostranenie) was useful in attracting attention. The intentional ambiguity, particularly in the images we used, based on Victor CitationTurner’s ([1969] 1991) disorientation concept, proved to be particularly useful in pulling people into conversations. We deliberately placed ourselves and our merchandise shop in an everyday public realm space (a market) which provoked curiosity. Located between food stalls, our experimental installation encouraged casual conversation, interest, repulsion and joy. Markets are liminal spaces of multi-sensory experience of smell, taste and noise, movement and bustle. As suggested by Vicky Cattell et al. (Citation2008) we found that these markets on the quaysides in Newcastle and Bristol were particularly good places to encourage the kind of casual and serendipitous encounter we were seeking. People were prepared to browse, linger and speak to strangers. The riverside locations and in the case of Newcastle, being surrounded by kittiwakes on the quayside, provided an important sensory link to water and the species under focus which was also useful in catalysing the conversations.

The stories presented on the printed merchandise helped people to reflect on both this content, and their own experience. Media representations of both these species – kittiwakes and eels – are often based on sensationalist stories, which provide a limited and sometimes scientifically inaccurate picture causing confusion and a lack of understanding of the human/non-human relationships. We aimed to probe the transdisciplinary science-creative space as a space for innovation. We feel there is considerable potential in using the productive tension between what is regarded as scientific fact and creative/imaginative activations and this is supported by a growing interest in artist-academic collaborative working. CitationTurner ([1969] 1991) emphasises the importance of experiential learning and the use of rationality, volition and memory and their development through life, and although our conversations were primarily with adults, our work with schoolchildren in another part of the overall Hydrocitizenship ProjectFootnote6 supports an eco-realistic creative approach.

This project opens up many interesting questions for collaborative transdisciplinary creative working. A key issue was the extent of the contact and exposure that we could achieve by such methods and while we found our representations did challenge and act as a fascinator, further work is needed to explore such methods. However, the specific work in-context was reflected in our conversations, so the location on the quaysides next to water was important. The centrality of water – and water settings – was the core framework for our creative research and experimental interventions. The species in question are fluid entities, existing in intimate contact with sea and rivers. We sought to bring centre-stage some of the affective presence and agency of water and watery species; to present emotional landscapes. In parallel to our central focus on two species, we encountered, and were acutely aware of, many of the wider narratives around water at these locales – such as the transience of human imprints and infrastructure; flooding and the deep-time patterns that will inevitably assert themselves; migration too of humans – journeying over water to new lands. Taken together, these encounters all point to modes of respect and interbeing that are often missing, but which are vital for healing and regeneration. As Daniel Wahl (Citation2016) puts it ‘We can choose to activate and embody the story of separation or the story of interbeing’ (246).

Overall, the project has provoked much interest in a number of arenas and while we are unable to determine the long-term impact of our work, we feel that it indicates that Morton’s (Citation2016) suggestion of a knowledge loop where exposure to unsettling by stealth can release or build better human/non-human awareness or understandings may be useful, particularly in places (such as markets) where presentations or provocations about these subjects are not normally encountered.

Acknowledgments

The ‘Hydrocitizenship’ project was a 3-year Arts and Humanities Research Council project that involved creative co-production methods in rethinking our relationships with water, and with each other through water. In four UK case study areas, 15 Researchers from 9 universities collaborated with arts practitioners, community groups and policy-makers. We acknowledge the collaboration of The Letterpress Collective, Bristol in the development and creation of the objects and events described in this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maggie Roe

Maggie Roe Reader in Landscape Planning Research & Policy Engagement and Dean of Postgraduate Studies, Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, Newcastle University, UK. She is a Fellow of the Landscape Institute, a Member of Natural England’s Science Advisory Committee (NESAC), an Editor of the international peer-review journal Landscape Research and a panel member of REF2021. Her research is based on principles of landscape planning and landscape ecology and examines issues of landscape planning and sustainability with a special focus on participatory landscape planning, new cultural landscapes and landscape change. Recent work focuses on water and food in the landscape working in interdisciplinary contexts with creative practitioners and communities.

Maggie has given numerous keynotes, lectures and examined in many countries. Funded by national and international government agencies, research councils and environmental bodies, she has published widely and has extensive reviewing experience. Recent research includes the transdisciplinary AHRC-funded ‘Hydrocitizenship’ project https://www.hydrocitizenship.com/and the Northern Heartlands Great Place HLF project https://northernheartlands.org/. Current projects include the Seascapes project: Tyne Tees Shores & Seas see http://www.exploreseascapes.co.uk/and two Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) projects: UKRI GCRF Water Security & Sustainable Development Hub https://www.watersecurityhub.org/and the UKRI Living Deltas Hub https://www.livingdeltas.org/Further information: http://www.ncl.ac.uk/apl/staff/profile/maggieroe.html#background

Antony Lyons

Antony Lyons is an independent artist-researcher working on landscape-related topics in the UK, Ireland and further afield. Creative methods include video-sonics, photography and installation. With a background in eco/geo-sciences and landscape design, many of his projects are concerned with ecological processes, environmental change and nature-culture relationships. His research and production methods rely on creative fieldwork and geopoetic assemblages of imagery, sculptural materials, archives, field-recordings and conversations - developed in the context of both ‘slow’ and ‘intensive’ artist-residencies. This brings together scenarios of land abandonment, ecological recovery, rising coastal waters and the intentional submergence of lands by constructed dams/reservoirs.He was Lead Artist with the Hydrocitizenship project and Senior Creative Fellow with the 4-year international AHRC ‘Heritage Futures’ project. In 2018/9, Lyons conducted a suite of artist residencies under the title ‘Limbo Landscape Lab’. This included a year-long residency in 2018 with Wheal Martyn Museum (Cornwall, UK), and in 2019 with the National Trust organisation, working with staff and volunteers at Orford Ness (Suffolk, UK). He is now working on a residency project in the iconic Elan Valley in Wales, a place with multi-layered poetic narratives, weaving together people, water, heritage and the natural world.

Notes

1. For example, it is estimated that six million people marched in cities around the world during the month of the UN Climate Action Summit in 2019 (Lancet Planetary Health Citation2019)

2. Diadromous fishes are unusual in that they spend part of their life in saltwater and part in freshwater.

3. An assemblage is art created by assembling various elements or objects. These may often be everyday objects and three-dimensional.

4. A performative installation is a creative intervention based on a theatrical or scenographic approach.

5. The Dark Mountain Projectwwwdark-mountain.net is an online and book-publishing initiative, substantially based around new ecological writings addressing ‘humanity’s delusions of difference, of its separation from and superiority to the living world which surrounds it’ and the fact that ‘We are the first generations born into a new and unprecedented age – the age of ecocide.’

6. See ‘Protect the Eels’ an animation created by children from Victoria Park Primary School Bristol, in conjunction with Lucy Izzard http://www.lucyizzard.co.uk/animation/protect-the-eels/

References

- Abram, D. 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Vintage Books.

- Armitage, S., and T. Dee, eds. 2009. The Poetry of Birds. London: Viking.

- Arts, B., M. Buizer, L. Horlings, V. Ingram, C. Van Oosten, and P. Opdam. 2017. “Landscape Approaches: A State-of-the-Art Review.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 42 (1): 439–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060932.

- Bachelard, G. 1983. Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, eds. E. R. Farrell. Dallas, Tx: Pegasus Foundation.

- BirdLife International 2018. Rissa Tridactyla. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: E.T22694497A132556442. Accessed 02.06.19. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22694497A132556442.en

- Bowman, D. 2007. “Using Landscape Ecology to Make Sense of Australia’s Last Frontier.” Key Topics in Landscape Ecology. edited by J. Wu and R. Hobbs, 214–226. Cambridge: CUP. doi-org.libproxy.ncl.ac.uk/10.1017/CBO9780511618581.013

- Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Carson, R. 2011. The Sense of Wonder. 1956. New York: Open Road Media.

- Cattell, V., N. Dines, W. Gesler, and S. Curtis. 2008. “Mingling, Observing, and Lingering: Everyday Public Spaces and Their Implications for Well-being and Social Relations.” Health & Place 14 (3): 544–561. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.10.007.

- Chen, C., J. MacLeod, and A. Neimanis, eds. 2013. Thinking with Water. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Cocker, M., and R. Mabey. 2005. Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Coulson, J. C. 2002. “Black-legged Kittiwake.” In The Migration Atlas: Movements of the Birds of Britain and Ireland, edited by C. Wernham, M. Toms, J. Marchant, J. Clark, G. Siriwardena, and S. Baillie, 377–380. London: T. & A. D. Poyser.

- Coulson, J. C. 2011. The Kittiwake. London: T&AD Poyser.

- Couzens, D. 2017. Songs of Love & War: The Dark Heart of Bird Behaviour. London: Bloomsbury.

- Cox, I. E. B., ed. 1866. Sea Gulls, to Cook: The Country House, a Collection of Useful Information and Recipes. London: Horace Cox.

- Cronon, W. 1992. “A Place for Stories: Nature, History and Narrative.” The Journal of American History 78 (4): 1347–1376. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2079346.

- Crutzen, P. J. 2002. “Geology of Mankind.” Nature 415 (6867): 23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/415023a.

- Crutzen, P. J. 2006. “The ‘Anthropocene’.” In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene: Emerging Issues and Problems, edited by E. Ehlers and T. Kraftt, 13–18. Berlin: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-26590-2_3.

- Davies, C., J. Shelley, P. Harding, I. McLean, R. Gardiner and G. Pearson. 2004. Freshwater Fishes in Britain. Colchester: Harley Books.

- Deakin, R. 2014. Waterlog: A Swimmer’s Journey through Britain. London: Vintage.

- Doughty, R. W. 1974. Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation: A Study in Nature Protection. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Eagleton, T. 1990. The Ideology of the Aesthetic. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Farber, P. L. 2000. Finding Order in Nature: The Naturalist Tradition from Linnaeus to E. O. Wilson. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- France, R.L. 2001. Thoreau on Water: Reflecting Heaven. Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Hall., C. J., A. Jordaan, and M. G. Frisk. 2011. “The Historic Influence of Dams on Diadromous Fish Habitat with a Focus on River Herring and Hydrologic Longitudinal Connectivity.” Landscape Ecology 26 (1): 95–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-010-9539-1.

- Haraway, D. 2015. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6 (1): 159–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934.

- Haraway, D. 2018. “Staying with the Trouble for Multispecies Environmental Justice.” Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (1): 102–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820617739208.

- Haraway, D. 2019. “It Matters What Stories Tell Stories; It Matters Whose Stories Tell Stories”, a/b: Auto/Biography Studies. 34 (3): 565–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08989575.2019.1664163.

- Haraway, D. J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hátún, H., B. Olsen, and S. Pacariz. 2017. The Dynamics of the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre Introduces Predictability to the Breeding Success of Kittiwakes. Frontiers in Marine Science 4: 123. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00123.

- Henderson, P. A., S. J. Plenty, L. C. Newton, and D. J. Bird. 2012. “Evidence for a Population Collapse of European Eel (Anguilla Anguilla) in the Bristol Channel.” Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 92 (4): 843–851. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531541100124X.

- HLPW. 2018. Making Every Drop Count: An Agenda for Water Action. UN & World Bank, Accessed 23. 07.19. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/17825HLPW_Outcome.pdf

- Hoestlandt, H., ed. 1991. The Freshwater Fishes of Europe 2: Clupeidae Anguillidae. Wiesbaden: AULA-Verlag.

- Illich, I. 1986. H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness: Reflections on the Historicity of “Stuff. London: Marion Boyars.

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). 2019. Summary Tables (Table 2: Changes in Numbers of Species in the Threatened Categories (CR, EN, VU) from 1996 to 2019). Accessed 02. 06.19. https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/summary-statistics

- Jacoby, D., and M. Gollock. 2014. Anguilla Anguilla. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: E.T60344A45833138. Accessed 02 06 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T60344A45833138.en

- JNCC (Joint Nature Conservation Committee). 2017. Black-legged Kittiwake Rissa Tridactyla. Accessed 06 07 2017. http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-2889

- Jones, O., L. G. Barnes, and A. Lyons. 2019. “Voicing Waters: (Co-)creative Reflections on Sound, Water, Conversations and Hydrocitizenship.” In Sounding Places More-Than-Representational Geographies of Sound and Music, edited by K. Doughty, M. Duffy, and T. Harada, 76–96. London: Edward Elgar. doi:https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788118934.00014.

- Keesstra, S., J. Nunes, A. Novara, D. Finger, D. Avelar, S. Kalantari, and A. Cerda. 2018. “The Superior Effect of Nature Based Solutions in Land Management for Enhancing Ecosystem Services.” Science of the Total Environment 610-611: 997–1009. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.077.

- Kessler, F. 2010. “Ostranenie, Innovation and Media History.” In Ostrannenie: On “Strangeness” and the Moving Image. The History, Reception, and Relevance of a Concept, edited by A. Van Den Oever, 61–79. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Kitchiner, W. 1817. Apicius Redivivus; Or, the Cook’s Oracle. Accessed 07.07.2017. London: Bagster. https://archive.org/stream/apiciusredivivu00kitcgoog#page/n5/mode/2up

- Kuroki, M., M. J. P. Van Oijen, and K. Tsukamoto. 2014. “Eels and the Japanese: An Inseparable, Long-standing Relationship.” In Eels and Humans, edited by K. Tsukamoto and M. Kuroki, 91–108. Tokyo: Springer.

- Lancet Planetary Health. 2019. Editorial: Looking for Leaders, 3:e399.Accessed 26 10 2019. www.thelancet.com/planetary-health

- Legagneux, P., N. Casajus, K. Cazelles, C. Chevallier, M. Chevrinais, L. Guéry, C. Jacquet, M. Jaffré, M.-J. Naud, F. Noisette, et al. 2018. “Our House Is Burning: Discrepancy in Climate Change Vs. Biodiversity Coverage in the Media as Compared to Scientific Literature.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 5: 175. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2017.00175.

- Lidström, S., and G. Garrard. 2014. “Images Adequate to Our Predicament: Ecology, Environment and Ecopoetics.” Environmental Humanities 5 (1): 35–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615406.

- Lyons, A. 2018. “Sunless Waters of Forgetfulness (A Geopoetic Assemblage).” In Water, Creativity and Meaning; Multidisciplinary Understandings of Human-water Relationships, edited by L. Roberts and K. Phillips, 54–69. London: Routledge.

- Lyons, A., M. H. Roe, and N. Hand. 2017. Undercurrents, Pop-up Stall at AHRC Connected Communities Conference, The Water Shed, Bristol 13. 07.17.Exhibition booklet available: https://www.hydrocitizenship.com/uploads/2/6/4/2/26426437/undercurrents_low_res.pdf

- Macfarlane, R. 2019. Underland: A Deep Time Journey. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Magrane, E., and M. Johnson. 2017. ““An Art–science Approach to Bycatch in the Gulf of California Shrimp Trawling Fishery”.” Cultural Geographies 24 (3): 487–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474016684129.

- Makel, J. 2011. Memories of Egg Collecting at Bempton Cliffs. Accessed 06. 06.17. http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/humberside/hi/people_and_places/nature/newsid_9382000/9382433.stm [

- Malm, A., and A. Hornberg. 2014. “The Geology of Mankind? A Critique of the Anthropocene Narrative.” The Anthropocene Review 1 (1): 62–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019613516291.

- McCarthy, T. K. 2014. “Eels and People in Ireland: From Mythology to International Eel Stock Conservation.” In Eels and Humans, edited by K. Tsukamoto and M. Kuroki, 113–140. Tokyo: Springer.

- Merritt, M. A. 2016. Sky Full of Birds: In Search of Murders, Murmurations and Britain’s Great Bird Gathering. London: Rider/Penguin.

- Morton, T. 2009. Ecology without Nature. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Morton, T. 2010a. “Thinking Ecology: The Mesh, the Strange Stranger and the Beautiful Soul.” Collapse VI: 265–293.

- Morton, T. 2010b. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Morton, T. 2016. Dark Ecology. New York: Columbia Univ. Press.

- Naess, A. 1977. “Spinoza and Ecology.” Philosophia 7 (1): 45–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02379991.

- Nagy, J. F. 1985-86. “Otter, Salmon, and Eel in Traditional Gaelic Narrative.” Studia Celtica 20-21: 123–144.

- National Biodiversity Network. 2019. State of Nature Report. Accessed 27 10 2019. https://nbn.org.uk/stateofnature2019/

- Novacek, M. 2008. “Engaging the Public in Biodiversity Issues.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of America 105 (Supplement 1): 11571–11578. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0802599105.

- Ostrom, E., and J. Walker. 2003. Trust and Reciprocity: Interdisciplinary Lessons from Experimental Research. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Otto, E. C. 2012. Green Speculations: Science Fiction and Transformative Environmentalism. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Pedroli, B., T. Pinto-Correia, and P. Cornish. 2006. “Landscape – What’s in It? Trends in European Landscape Science and Priority Themes for Concerted Research.” Landscape Ecology 21 (3): 421–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-005-5204-5.

- Pereira, H. M., and L. M. Navarro, eds. 2015. Rewilding European Landscapes. London: Springer Open. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12039-3.

- Pihkala, P. 2018. ““Eco-anxiety, Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Climate Change” (The Wicked Problem of Climate Change).” Zygon 53 (2): 545–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/zygo.12407.

- Post, J., and B. Pijanowski. 2019. “Coupling Scientific and Humanistic Approaches to Address Wicked Environmental Problems of the Twenty-first Century: Collaborating in an Acoustic Community Nexus.” MUSICultures 45 (1–2): 71–91.

- Probyn, E. 2016. Eating the Ocean. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Prosek, J. 2011. Eels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World’s Most Mysterious Fish. New York: HarperCollins.

- Reading, P. 1983. “At Marsden Bay.” In Diplopic. London: Martin Secker & Warburg.

- Righton, D., and M. Roberts. 2014. “Eels and People in the United Kingdom.” In Eels and Humans, edited by K. Tsukamoto and M. Kuroki, 1–12. Tokyo: Springer.

- Roe, M. H., and S. Stead. 2021f. “Shared Socio-cultural Values for Seascape Planning.” In A Seascape Handbook, edited by G. Pungetti. Oxford: Routledge.

- RSPB. 2017. Birds of Conservation Concern. Accessed 07.07.2017. http://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/birdsofconservationconcern4_tcm9-410743.pdf

- Schweid, R. 2004. Consider the Eel: A Natural and Gastronomic History. Boston, Ma: Da Capo Press.

- Shklovsky, V. 1998. “Literary Theory: An Anthology.” In Art as Technique, edited by J. Rivkin and M. Ryan, 15–21. 1917. Malden: Blackwell Publishing .

- Simon, A. L., edited by. 1942. A Concise Encyclopaedia of Gastronomy. Section II Fish London: Wine & Food Society.

- Simon, A.L. edited by. 1944. A Concise Encyclopaedia of Gastronomy Section VI Birds and Their Eggs. London: Wine & Food Society

- Strang, V. 2004. The Meaning of Water. Oxford: Berg.

- Szakolczai, A. 2009. “Liminality and Experience: Structuring Transitory Situations and Transformative Events.” International Political Anthropology 2 (1): 141–172. www.politicalanthropology.org.

- Thomassen, B. 2006. “Liminality.” In Encyclopedia of Social Theory, edited by A. Harrington, B. Marshall, and H.-P. Müller, 322–323. London: Routledge.

- Trammell, E. J., S. K. Carter, T. Haby, and J. J. Taylor. 2018. “Evidence and Opportunities for Integrating Landscape Ecology into Natural Resource Planning across Multiple-Use Landscapes.” Current Landscape Ecology Reports 3 (1): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40823-018-0029-5.

- Tress, B., G. Tress, G. Fry, and P. Opdam. 2005. From Landscape Research to Landscape Planning: Aspects of Integration, Education and Applications. NL: Springer.

- Tsukamoto, K., and M.Kuroki, eds. 2014. Eels and Humans. Tokyo: Springer

- Turner, V. 1991. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. 1969. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

- Verboom, J., P. Schippers, A. Cormont, M. Sterk, C. C. Vos, and P. F. M. Opdam. 2010. “Population Dynamics under Increasing Environmental Variability: Implications of Climate Change for Ecological Network Design Criteria.” Landscape Ecology 25 (8): 1289–1298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-010-9497-7.

- Wahl, D. C. 2016. Designing Regenerative Cultures. Axminster: Triarchy Press.

- Wallace-Wells, D. 2019. The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming. New York: Tim Duggan Books.

- Waller, D. M., and S. Flader. 2010. “Leopold’s Legacy: An Ecology of Place.” In The Ecology of Place: Contributions of Place-Based Research to Ecological Understanding, edited by I. Billick and M. Price, 40–62. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Waterton, C. 1838. Essays on Natural History. London: Longman. https://archive.org/stream/essaysonnatural04wategoog#page/n252/mode/2up/search/kittiwake

- Wattchow, B. 2013. “Landscape and a Sense of Place; a Creative Tension.” In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies, edited by P. Howard, I. H. Thompson, and E. Waterton, 87–96. London: Routledge.

- Wilson, E. O. 2016. Half-earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Wilson, K., and L. Veneranta, eds. 2019. Data-limited Diadromous Species – Review of European Status. Copenhagen: ICES Cooperative Research Report, 348. 273. doi:https://doi.org/10.17895/ices.pub.5253.

- Woolgar, C. M. 2003. “‘Take This Penance Now, and Afterwards the Fare Will Improve’: Seafood and Late Medieval Diet.” In England’s Sea Fisheries: The Commercial Sea Fisheries of England and Wales since 1300, edited by D. J. Starkey, C. Reid, and N. Ashcroft, 36–44. London: Chatham Publishing.

- WWF. 2019. How Many Species are We Losing? Accessed 02. 06.19. http://wwf.panda.org/our_work/biodiversity/biodiversity/

- Younger, P. L. 2012. Water: All that Matters. London: Hodder & Stoughton.