ABSTRACT

The Gaelic tree alphabet is an ancient connection between trees and writing. In the Highlands of Scotland, it has recently been used as a structure for engaging people in interdisciplinary encounters at the boundary between forestry and literature, through a project called A-B-Tree. Poetic inquiry methods enabled exploration of how making a creative response to a tree can influence learning and attitudes. The A-B-Tree project has amassed evidence that tree-related wordplay is good for our well-being and stimulates and deepens thinking about trees. The poetic inquiry method has itself been a source of insights into the epistemological edge-zone between ways of knowing in poetry, folklore and forest ecology in particular and more generally between artistic practice and scientific knowledge.

Introduction: the A-B-tree project

For nearly a decade, in a project called A-B-Craobh (A-B-Tree in English) I have used the Gaelic tree alphabet to facilitate learning and creativity linking forests and literature, mostly, but not exclusively, in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. The project has at its heart an interdisciplinary knowledge base about the native woodland species which have traditionally been linked to the eighteen letters of the alphabet used in the Scottish and Irish Gaelic languages. The knowledge base consists of thousands of titbits of information about ecology, folklore, place names, practical and medicinal uses, plus an anthology of poems (Haggith Citation2013). It began from research I did for my first novel, The Last Bear, which uses the alphabet as a structure for the narrative, and it evolved into a set of prompts for creative writing exercises and then into web pages, growing organically over the years as people have interacted with it, correcting and adding to its contents. These poems and snippets of knowledge have been used in a wide variety of contexts, from woodland walks to therapeutic workshops and latterly in school and college classes, to support people to write creatively.

The A-B-Tree project began in 2011, with a series of creative writing events in woods and gardens around Scotland to celebrate the International Year of Forests. In 2013 a similar event series was organised as part of a poetry residency in the Royal Botanical Gardens, Edinburgh. In 2018 the project moved into the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) (partly funded by the government agency, Scottish Forestry) to explore in a more systematic manner the potential for the Gaelic tree alphabet to be used for creativity and learning. Over the decade more than 1,000 people have participated in events delving into tree folklore, ecology, practical uses and nomenclature including Gaelic, and have been encouraged to respond creatively. This paper will focus on the last two years, during which more than 300 people have been involved, including schoolchildren and their families, and students and academics in creative writing, literature and forestry. A community of practice is growing at UHI (and in partner organisations), linking forestry and literature/creative writing, with plans for further work including curriculum developments, work with artists in residence, production of materials and facilitation guidance for use in educational contexts.

The A-B-Tree project aims to generate insights about how to facilitate tree-related creativity and to investigate what students learn when they take part in interdisciplinary activity between literature and forestry, as an example of ‘transcending the Humanities/STEM divide’ (Watkins and Tehrani Citation2020). The methodology is poetic inquiry (Vincent Citation2018), using poems in four ways: as experimental materials to prompt participant responses; as data providing evidence of participant attitude or knowledge; by adopting the process of writing poems as an analytical and reflective technique; and for dissemination of findings. Indeed analysis through poem-writing has been one of the central innovations in the project, and this paper’s focus is on what has been learned both through and about poetic inquiry technique and the creation of ‘poemish’ texts, i.e. texts that are not conventional poems but which arrange words in playful and poetic ways, such as by exploiting sound patterns, shapes or figurative language, also referred to as ‘good enough research poetry’ (Lahman, Richard and Teman Citation2019, 215). By adopting this radical methodological approach, it could be argued that in addition to being interdisciplinary this research qualifies as ‘transdisciplinary’, as it attempts to transcend the disciplinary divides ‘by disobeying their barriers and norms’ (Peterson Citation2019, 69).

Poetic inquiry is a form of Arts Based Research, which uses poetry as a way to reveal and explore the meaning that people find in the world and to understand their lived experience (Leavy Citation2015; Faulkner Citation2017). Poems can be used in several different ways in research: poems stimulate dialogue and expression by participants; research participants may be encouraged to write poetry, either individually or collectively, as a way of generating data about their experiences, views or feelings; researchers can write poems to draw out salient issues from qualitative, textual data such as interview transcripts; researchers can write poems as a way to analyse and reflect upon research processes; and finally poems may be used as reporting or dissemination tools. A poetic inquiry research study may involve some or many of these methods. A-B-Tree uses them all, with poetry being written throughout the project.

Some of this poetry is conventional, publishable work where at least part of the aim in writing is literary quality, while some is deliberately playful ‘poemish’ writing that is used primarily for the insight it generates or voice it gives to a key person or issue (Lahman et al. Citation2010; Lahman, Richard and Teman Citation2019). The use of ‘poemish’ writing is a novel, attractive and non-threatening way to collate and integrate a wide range of views from diverse groups of people. While reading and writing poetry may not seem an obvious analytical method, it involves a similarly close attention to the detail of participants’ words as more conventional discourse analysis methods, highlighting repetitions and common themes, while also drawing out resonances and nuances in language that can shed light on issues in a novel way and honouring the lived, emotional experiences being expressed. Without assuming any absolute or objective reliability of people’s statements of their emotional states, poetry can provide active, disruptive, interestingly provocative analyses of textual data and ‘produce findings and insights not readily discoverable via more conventional research methods’ (Owton Citation2017, 7). Poetic inquiry has been most frequently used in education and the health sciences (Gitlin and Peck Citation2008), but there is a burgeoning body of work in the natural sciences and on resource management, where problems are ‘wicked’, meaning that they are difficult or impossible to solve due to their complexity or due to inconsistent, changing or interconnected requirements (DeFries and Nagendra Citation2017). Scientific or social science research ‘often fails to account for culture, agency and lived experience of those dependent upon … natural resource systems’, whereas poetry offers a ‘method to reach a deeper level of understanding and collaborative learning than available … through conventional modelling and survey research’ (Fernández-Giménez, Jennings and Wilmer Citation2019, 1089).

The gaelic tree alphabet

The Gaelic tree alphabet links each of the letters of the Gaelic alphabet to a native woodland species, mostly, but not all, trees. It is uncertain how old this tradition is, and its origin is contested, although it was prevalent by the fourth century and may be older. It is based on an inscription script, called Ogham, which looks rather like (and may have evolved from, or alongside) Norse runes, and takes a different sequence to the Latin alphabet, with all the vowels at the end. Ogham may be an early form of writing that predates the arrival of the Latin alphabet to Britain, with the Romans and then Christianity, or it may be a local variant of the Latin alphabet originating in Ireland (O’Sullivan and Downey Citation2014). The earliest form of the alphabet had 20 letters, although modern Gaelic uses only 18 (having ceased to use Q, Ng and St/Z and added P). There are a number of different versions of the Gaelic tree alphabet and some controversies about which species should be associated with each letter. Some letters are uncontroversial: the first letter, B, is almost universally agreed to represent beithe, meaning birch; C is always hazel (coll or calltain); D is always oak (doir or darrach); S is always willow (sail or suillean). However there is debate about whether A is elm or pine, whether M is vine or bramble, whether T or O is gorse, and which species should represent the late-arrival P. Neopagan, druidic and new age mystical writers have developed a range of interpretations of the alphabet (Murray and Murray Citation1988; Blamires Citation1997; Kindred Citation1999), some inspired by and others resisting the Celtic revivalist elaborations of Robert Graves (Citation1948). Apart from Herbert Edlin’s Citation1950 work, digging into an old Irish source (1950), few foresters have paid it much attention, although there have been some instances of the alphabet being incorporated as a structure for community woodland planting schemes, notably the Millennium Forest project ‘A’ Craobh’, at Borgie, Sutherland, and for educational displays such as the one at Inverness Museum (Sutherland and Beith Citation2000).

In much of the Scottish Highlands and Islands Gaelic is the indigenous language and is used for most place names in non-urbanised contexts. Gaelic is seen increasingly as a ‘language of nature’, as so many rural landscape names describe habitats or species found there, for example, the island of Iona is named for yew trees and my neighbouring township is Baddidarach, or ‘place of the oaks’. The notion that the world is legible through nature is currently fashionable, popularised by the success of Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks (Citation2016), but it has long been a key concept for geologists who read the past in the rocks and it can be traced back through Barry Lopez to Aldo Leopold in North America and in Britain through John Clare and William Blake back to the Mediaeval church scholars with their ‘book of nature’. The even earlier link between the letters of the Gaelic alphabet and trees suggests that nature and writing are very fundamentally connected.

Gaelic is threatened as the number of native speakers reduces and this threat is being addressed through government policy and community-driven initiatives. The language therefore plays an important part in debates about conservation and ways to make it visible and relevant to people are widely welcomed. The A-B-Tree knowledge base is rich in Gaelic place names, etymology and characters or phrases from Gaelic literature, which can help people to understand and appreciate more about trees, whilst also showing how they are embedded in the language and broader culture. When connected to ecological or technical facts about trees, this helps to blur the boundary between science and culture, limit participants’ expectations that the research is seeking ‘the truth’ about trees and promote a sense that their own knowledge and experience of trees is relevant, wherever it originates.

The A-B-Tree project has adopted a pragmatic approach to the alphabet, treating it as an organisational principle for knowledge and celebrating its potential for stimulating creativity in response to woods and trees. The version of the alphabet that the project uses is in . The traditional sequence of letters is adhered to, with the vowels at the end, so the alphabet begins with birch (matching all its folklore connotations of birth, conception and inspiration, its ecological role as a pioneer species and practical value as a firelighter) and ends with yew (with all its connotations of death and toxicity). More details of the specific letter choices I have made is published in Scottish Forestry (Haggith Citation2020b).

Table 1. The Gaelic Tree Alphabet

Method: poetree leaves

In order to find out what people learn by writing creatively about trees, I organised 21 creative encounters with a range of groups of people: schoolchildren and their families and teachers; adult learners both in formal education and informal workshops; and academics. Each encounter involved a single species and at least one event was organised for each letter of the Gaelic tree alphabet. Facilitation methods included free-writing, collective word generation, encouragement to write from all five senses, question and answer prompts and support to write based on model poems (Haggith Citation2020a).

In all encounters a selection of titbits of knowledge about the tree were shared among the participants, giving a spread of information that included folklore, ecology, practical uses and naming conventions, plus a selection of drawn and photographic imagery. Usually this was done by handing out slips of paper to be read out, and sometimes by giving participants prior access to a webpage to read. In all outdoor encounters, participants had the opportunity to use all their senses to become familiar with the tree. I took care to make events accessible and worked with support staff to enable participation in sessions by people with limited hearing, vision or mobility or with mental health problems.

In a poetic inquiry process, poems can play a role in the research in various ways, and in this project their first role was stimulation of participants. In every encounter at least one poem, in most cases several poems, were read out and discussed, sometimes in considerable depth. For example, with a group of third year literature undergraduates, discussion focused on an untitled poem about pine by Scottish poet Alan Spence, a haiku by Kobayashi Issa (eighteenth century Japanese poet) and ‘Pine Tree Tops’ by American poet Gary Snyder. A workshop with first year creative writing undergraduates on blackthorn explored ‘Sloes’ by Vicki Feaver, ‘In a Blackthorn Spring’ by Lynne Wycherley and ‘Sloe Gin’ by Seamus Heaney. By contrast, with a group of primary school children, the poetry injection was limited to my own diminutive willow poem.

tundra tree

tiny teacher

of tenacity

The second role poems played was as data gathered from participants. Asking research subjects to compose poetry or generate poetic words or phrases is a relatively unusual method of data gathering, compared to questionnaires or interviews, but it can be viewed from a postmodern perspective as a way to do what Jacques Derrida calls ‘opening of space’ (Citation1976) and as a challenge to the concept that certain conventional data forms generate ‘the “right” or the privileged form of authoritative knowledge’ (Richardson Citation2000, 928). Poetic inquiry begins by questioning the cost of giving a privileged status to numbers or prose, ‘and what knowledge this privilege has lost or obscured’ (Lahman et al. Citation2010, 46). As a poet, I know that when I compose poetry I think deeply, connecting my wonder at the world with wondering about it, and it is that blend of affective and cognitive response that I am keen to discover by encouraging my participants to write ‘poetically’.

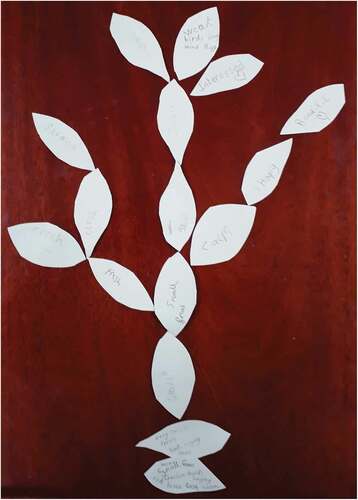

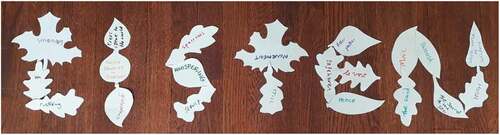

From a practical perspective, most encounters involved getting participants to write words and phrases on paper leaves or equivalent small pieces of paper or card. In some cases the events were run online, either because the participants were geographically distributed or because of the COVID-19 lockdown, or both, and in these cases participants wrote using an online chat facility during a video conference. A number of different prompts were provided to stimulate participants, such as, ‘How do trees make you feel?’, ‘What do trees mean to you?’, ‘What can you hear/see/smell/touch/taste?’, ‘What does this species evoke for you?’ In many cases several prompts were given, for example, asking people what trees meant to them before and after the session in order to have comparative material, with different coloured leaves used for each question to help the answers to be distinguished. As well as gathering the colour-coded leaves as data for the project, they were often also used in creative ways during the session, to generate collective poems in the form of a ‘poetree’ (see ) or other playful form (see ).

Figure 2. Paper leaves with words evoked by the sound of trees formed into a poem ‘Listen’, which later formed part of a large floor-installation called ‘Listen Feel Wonder Under’, exhibited in the Sawyer Art Gallery at Inverewe Garden, September 2019.

Whole poems written by participants were sometimes gathered as data for exploring what had been learned in the encounters and for analysing which of the interdisciplinary titbits made an impact; however other than in some controlled class situations it was often extremely hard to capture the poems produced, as every poet is shy about sharing draft material, and novice poets particularly so. Nonetheless, in most encounters guidance and encouragement were given for participants to write their own poem. This ranged from encouragement to create an acrostic or haiku, for beginners, to more extensive guidance on poetry drafting for experienced writers, building on the use of all five senses, using example poems as formal models, and so on. While the resulting body of poetry is partial, it can still indicate what has been learned by a participant. The following example from a workshop on ash trees shows a creative writing student absorbing a range of technical language (e.g. ‘keys’), ecological knowledge (a preference for fertile soil), folklore (the allusion to lightning strikes) and practical uses (medicinal use).

Mother

Late in life her keys spun out of control,

and two saplings grew,

flourishing beneath her wine-soaked branches

when the ground was fertile,

surviving the stony and barren times.

Her bark became withered, slightly acidic

caused by Daily Mail mulch.

Three times lightning struck,

each time she rose with wine drenched blossom,

smoking to holy ash, her magic cure.

Charlotte usher

The third role poems played in the A-B-Tree project was as a method for analysis of data. After each event, I gathered up the words that people wrote on paper leaves (or equivalent, including in the chat box in video conferences) and used them as a lexicon to generate one or more poems. This is a process of what Terry Barrett calls ‘hard fun’, as I played with the words to see what patterns they suggested (Citation2011, 8). It draws on the experiences of the many hundreds of poetic inquirers (reviewed by Adam Vincent, for example (2018) who see ‘poetic rumination’ as a way of knowing and viewing the world that keeps emotive and cognitive content inherently connected (Leggo Citation1999, Citation2008).

The fourth role of poetry in the project was as a way of reporting on results in publications such as this one, in person at conferences and other meetings and on YouTube and other internet sites. A poem installed in an art gallery, on a magazine cover, performed at literary festivals or open mic events, and shared on social media, can achieve a far wider dissemination than conventional research results.

Results: poemish writing

Poetry’s power for analysis has proven substantial during this project and merits more consideration. I have written at least one poem for each encounter event, thirty-six altogether, in order to analyse the written responses of participants. My approach to poetry is that I am basically a lyric nature poet, with a preference for surface lucidity and conventional grammar, but also a fondness for exploration of the shape and texture of poems. This undoubtedly influences the approach I take to this analysis, in which I mostly seek to blend and harmonise multiple participants’ contributions (without changing them) in order to achieve at least an illusion of a ‘group voice’. Sometimes my stylistic approach to what is effectively ‘found poetry’ deliberately seeks to challenge and highlight lexical features in more graphic ways, as the examples below show.

Some of the poems written from participants’ words, and with their involvement, appear simply fun, yet are powerful demonstrations of key research findings. One of the most successful examples is called ‘Trees Make Us Feel Happy’. It was generated from an open day at the Scottish School of Forestry, Balloch, during which 158 people wrote words on paper leaves in answer to the question ‘How do trees make you feel?’, more than 50 of which were ‘happy’ in English, Gaelic, Dutch or French. During the open day the leaves were formed into a huge ‘poetree’ on a picnic table. Afterwards I tried to find a way to combine all the words into a single poem. Having so many instances of a single word was clearly a problem, poetically speaking, and the solution was to use a refrain: ‘Trees make us feel happy, happy, happy/Trees make us feel happy!’ It is a delightful poem to perform, as a way of showing people both what my process is and how it can reveal dominant themes as well as the patterns of variation among participant responses.

As well as sound and video poems, the process of creation with paper leaves lends itself to creative visual forms, so the resulting body of poems is fully multi-media. One of the most interesting of these originated in a workshop on oak at Inverewe Garden, involving gardeners and visitors in answering questions about how trees make them feel, what they hear when they listen to the trees, and what trees mean to them. The resulting three poems were combined with one of my own about the roots of a tree in a non-linear hyper-poem, ‘Listen Feel Wonder Under’, installed on the floor of the Sawyer Art Gallery as part of an exhibition in September 2019 and printed on the cover of volume 80 of Writing in Education.

The poems, both individually and as a collection, reveal themes that come up repeatedly. The most common words by far that participants write are ‘happy’, ‘life’, ‘peaceful/peace’, ‘calm’, and other terms suggesting a strong connection between their experience of trees and wellbeing. As in the example above of ‘Trees Make Us Feel Happy’, refrains are a useful poetic solution to the problem presented by multiply repeated words. In many events the species name came up many times and needed similar poetic treatment. It should be noted that in some sessions with children, participants were obviously copying each others’ words! It is interesting to reflect on the basis of word repetitions; on the day fifty people wrote ‘happy’ another fifteen participants wrote ‘calm’ on their leaves. This could either be expressions of genuine feeling or suggested by seeing what others write. The positive connotations of the vast majority of words may of course be because people who don’t like trees won’t take part in my research activities or self-consciously edit themselves; however, there are always some critical voices (see ‘Trees spoil the view’, below). Nonetheless, the fact that the same words kept coming up at different events, in different locations, surely indicates genuinely widespread associations.

Paradoxically, and perhaps as a result of the use of the wide-ranging knowledge titbits, as well as repetition, the words reveal a huge breadth of topics, from scientific terms, like ‘oxygen’ and ‘biodiversity’ alongside words about myths and folklore, like ‘dryads’ and ‘magic’. So a challenge for me was to show in the poems the wonderful diversity of voices in what one participant called the ‘leaf-page lexicon’. The following poem is an example of how both the repetition (convergence) and diversity (disparity) were revealed. Its title, a phrase provided by one participant, deliberately elevates the Gaelic language as a reminder of its significance to the project.

Freumhaichte ach a’ coimhead a dh’ ionnsàgh nèamh (Rooted but with eyes to the heavens)

An outdoor cathedral

beautiful life

A calm space

peaceful life

Rooted air

regenerative life

Sustainable shelter

verdant life

Shade, growth

green life

Wind in the willows

beautiful life

Free mind fuel

lush life

Peace, love, peace, love

tranquil life

State of grace

tall life

Water history

strong life

Air regenerator

peaceful life

Past, present and future

live life

In all cases I made sure that the poem included all of the words written by participants and in most cases restricted myself to only those words. In a few instances, I ‘cheated’ by adding phrases or words, but I used typography to reveal this. As discussed later, I sometimes took substantial liberties with the meanings and tone presumably intended by participants. It was often necessary to be creative in the use of nouns or adjectives as verbs in order to make any sense at all. I occasionally got lucky and spotted a creative way to use an otherwise unpromising collection of words, as the following example shows.

Dear friends,

Shelter childhood

(magnificent shelter,

God’s affirmation

and Robin’s retreat)

for innocence.

Love

us

xx

In a few cases the only feasible way of using the words was in a concrete form, such as this one which came from the words written by a small group of primary school children.

birds

birds tweeting

birds twitting tweeting

birds singing tweet tweet

the birds are singing songs

the lovely birds are singing

I think it is a swish of the wood

leaves ruffling trees blowing

wind stomps woody things

I can smell flowers

I can smell mint

smoky leaves

smelly wood

fresh

minty

smell

of

nachos

The greatest satisfaction came from constructing the words into the narrative arc of a poem, by finding a progression of some sort: dry to wet, cold to warm, sad to happy, quick-slow-quick, busy to peace, objective to subjective, past to future and so on. The following poem illustrates this point.

Trees spoil the view

They are ancient and unfamiliar,

claustrophobic, exotic,

full of memories of getting lost

in the quietness and darkness,

the silence of their shelter.

Their shelter is protection,

a return to home. The smell of birch in spring:

a symbol of the home environment.

The birch tree’s breath

smells of life, fun,

life, living and being in the world,

integrated with nature,

delighting in life and folklore,

magic and spells,

change.

They tell the time of year,

giant visual clocks, show time shifting,

Christmas to Spring,

the year’s stability,

sustainability and beauty.

Tree lives are barometers of climate,

weather, wind, air.

They produce beautiful effects of light.

Experience their sound – peacefulness and calm –

da swish o leaves in da wind.

And yet, they spoil the view.

Can poems save forests?

The poem above is perhaps most revealing when it is compared with the poem created from the words offered by some of the same participants at the end of a process which involved learning and writing about willow trees. Although some people could not stay until the very end of the session, it is interesting to see what those who did wrote in answer to the same question that had generated the poem above when asked at the start of the session: ‘What do trees mean to you?’

Connections

I am not supposed to breathe the air

the way I am reputed to,

but as a forest interbeing

with memories of the future absence time,

we do.

Tree persons probably have a protection relationship

with inhabitants of Scotland,

wolves and German angels.

They are wisdom guardians,

deep wisdom guardians,

vital knowledge keepers for our safety.

Trees are mythical kinds of beings.

Two things are interesting about this poem. One is that the poem is a rather contorted piece of ‘poemish’ – there was little in the way of ‘easy’ functional language to hang it together or help it to flow. However, the more interesting point is that the frequency of material and physical words has reduced and cultural, even spiritual, connotations are much more pronounced. This might be interpreted as a recognition of the deep connection with trees in Gaelic culture.

Here is an example from a small group of young adults who met to learn and write about hawthorn, and were asked the same question, ‘What do trees mean to you?’ at the start and end of the workshop. Again, the language and concepts used in the second poem suggest that trees now have considerably more significance to the participants than they did at the beginning.

Before

Trees are green,

protecting life,

strength, shelter, fuel,

they live so much longer than me.

After

Trees are vessels for emotional exploration,

a lot more than just big plants -

life-support machines

soaking up the past, pumping out the future,

lighthouses of nature, wardens of time.

This third example from a session with creative writing undergraduates combines the ‘before’ and ‘after’ words into a single poem, and illustrates my addition of some additional phrases, indicated by the non-italicised text.

Aspen otherness

Even before we talk about aspen trees

the writers say trees mean

inspiration. Inspiration!

Clean air, clean air.

(Like thrushes, writers say everything at least twice.)

Quality of life, life, life.

Breathing.

Recreation and employment.

Nature, wonder and peace.

Knots and tangles and space.

After they’ve looked and listened,

written and talked,

trees still mean recreation and employment,

life, life, life and living,

nature and wonder

but now there is also

otherness, intuitions and survival.

They are awe-inspiring and beautiful

yet also shelter, comfort and companionship.

Trees feed us and clothe us.

They paid for Christmas to happen.

Among untold stories,

they are part of me,

something not human,

wildness,

silence.

This phenomenon of enrichment of the language and concepts used to describe trees was replicated over several sessions, which seems to be real evidence that engaging in a process of interdisciplinary learning and creativity about trees can genuinely deepen people’s attitudes towards them. Pertinent next questions include whether that attitudinal change is lasting, and whether it could lead to changes in activity to reduce pressure on forests.

Discussion

Overall, considerable wealth of language and breadth of thinking is revealed by the poems. They are emotional, evocative, poignant and fun and seem to show that people engage deeply with trees. It is not hard to get people to do this – I never find I have to coerce participants. Even casual passers-by are easily persuaded to pick up a pen and write something on a paper leaf, and the words they write are often profound and moving. The results above show that these responses tend to deepen after further creative writing and learning is encouraged.

Events with students so far suggest that crossing the disciplinary divide between arts and sciences is beneficial for students from both sides. In one workshop focusing on Gaelic tree language, forestry students wrote on their paper leaves an expression of tree-love that amazed their lecturer, and in another session they surprised everyone by writing haiku. These sessions, coupled with other activities at the Scottish School of Forestry, demonstrate that a cultural layer in forestry education can lead to a sense of pride in their heritage and pleasure in creativity. Correspondingly, post-event written and verbal feedback indicates that exposing arts and creative writing students to trees gives them great pleasure and stimulating content, helping them deepen their thinking about and recognise connections between Gaelic and trees, for example in landscape feature names.

There are plenty of questions that the poetic inquiry has raised and not answered. For example, I have a hunch that people seem to write more creatively on paper leaves that are beautiful than on those that are roughly cut (compare ). More importantly, while I hope that when people deepen their thinking about trees through creativity they will value trees more and this will lead to changes in behaviour, more research would be needed to generate evidence one way or the other, and it is not clear that a poetic inquiry could generate such evidence.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I always asserted that an outdoor, physical encounter with a tree was a necessary component of the process of making a creative response to it, but some events had to happen online due to the lockdown, and one of the surprises was how deeply those students responded to the tree when only seeing pictures, reading poems and being urged to imagine the texture of bark, the sound of twigs in the breeze and the smell of leaf litter underfoot. The aspen poem above was the result of an online workshop and it seems to show just as much of a deepening of response as outdoor workshops. It will be interesting to explore further whether and how engagement with nature through poetry and other creative writing can be supported in a virtual learning environment.

One of the most interesting insights this project has generated concerns my own practice at the boundary of my roles as poet and teacher and how poetic inquiry has pushed me out beyond the edges of my normal poetic practice. The project has made me question which phrases and words I am willing to take ownership of and use in my writing, while still feeling a sense of integrity in putting my name to the content of a poem. At what point does the poem become ‘mine’ and not simply an amalgam of the words of others? I have found it interesting to catch myself wanting to distance myself from some of the phrases used by the participants, finding them discomfiting. Sometimes I have deliberately subverted them. As a simple example, when I took the phrases ‘not pleasant’ and ‘raining’ and in my poem wrote ‘pleasant’ and ‘not raining’, or when I broke up what I perceived as a cliché, such as ‘the swish of the leaves’, and used the words in different combinations, I could put my hand on my heart and say I used all and only the words used by participants, but I have actually turned those participants’ meanings on their heads. The poem ‘Trees Spoil the View’, above, is an example of how I have married my own passion for trees with some Shetlandic participants’ wariness of them. My work as a poet and my work as a researcher are uneasy bedfellows.

There is a deeper boundary issue at stake here as well: that between science and art. Part of the epistemological divide between these two domains lies in the contrast between ways of knowing: propositional (knowledge that) versus experiential (knowledge how). But that distinction feels inconsequential compared to the way literature (indeed all art) has an inherently subjective dimension, whether that be a reflection of the experiences of the artist in the work or the right to the reader or viewer’s own felt response, whereas science seems to require at least a passing respect for the idea of objectivity. The dichotomy between subjective malleability and objective hardness shows up in different ways of thinking about data. Data, looked at from a scientific perspective, is ‘hard’ and should not be meddled with, and even in qualitative, post-positivist social science methodologies, editing data is strictly against the rules, but in a poetic inquiry, when the data are words, it is hard to deny the instinct of a poet to polish, smooth, refine and tweak. The poetic inquirer inhabits a paradox: as a creative practitioner, the urge to enhance the literary quality of the poem is admirable, but as a researcher, it’s a kind of corruption.

Yet the starkness of this paradox can and should be questioned, as it does not correspond to how the disciplines can actually be blended. Poetry is an ancient kind of knowing, like the Gaelic folklore and story-telling tradition, in which modification of found material is de rigeur, and tales are twisted and moulded to fit the teller and their audience. Nonetheless, at the heart of many folklore stories there are nuggets that can be given explanations in ‘hard science’. For example, there is an ancient taboo about bringing hawthorn blossom into the house, told through a host of stories about curses and baby-murdering witches, which has a scientific justification due to the flowers’ emissions of trimethylamine, which attracts carrion-feeding, and thus disease-carrying, flies. Many myths or ‘old wives tales’, despite perhaps millennia of modification and personalisation, retain at their core a deep and scientifically provable truth. The poetry-science boundary blurs further when we see, (currently very clearly demonstrated in the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic), that the frontier of scientific knowledge is itself a region of interpretation, dialogue, endless revision and exploration into the unknown. Feeling comfortable with nuanced working and reworking in a context of profound uncertainty and unreliable information is in fact a vital attribute of a scientist, just as it is for a poet.

One corollary of this is that we all need to explore which aspects of our data are merely artefacts of our method of data gathering, rather than signals from the real world. In the case of my words on leaves, should I smooth away spelling errors, to show the intended words, or let them sing as they are? Do mis-spelled words speak ‘authentically’ of children’s voices? Or it is better to reject them as noise? The following poem illustrates a decision to retain them: there is something delightful in the inclusion of the mysterious ‘brisboirgtre’ and sonorous ‘brassingong’ in what would otherwise be a rather bland piece of poetree (and note that like many of the other poems, this one again demonstrates the overwhelming positivity of trees’ effect on us – they really do make most of us feel happy).

happy

full of life happy

safe safe safe happy

nice nice nice nice nice happy

brisboirgtre bon brassingong happy

calm calm calm calm happy

good kind happy

enjoyed happy

curious happy

sad

sad

quiet

want to climb

One final observation about the poetry generated in the project is that while none of the poems are the kind of thing I would normally write, and they vary from publishable-quality found poems to rather odd pieces of ‘poemish’ text, they have a collective integrity and interest akin to an ecosystem. As I play with the words generated by project participants, grouping them into lines, I blur the boundaries between what is theirs and what is mine, what is teaching and what is art, what is art and what is science, and in doing so I discover that, as Timothy Morton Citation2010 puts it, ‘When life, when writing, has begun, we find ourselves unable to draw a thin, rigid line around it’ (2010, 15).

As well as the questions raised earlier about influences of poetry on behaviour and the potential for virtual learning about nature, future developments of the A-B-Tree project will include more learning encounters and use of creative writing to deepen understanding and attitudes about nature and forests more broadly. Participants in the project have said they want more and longer sessions to create better poems. A community of practice is developing to explore how we can develop creative activities to deliver much more genuinely inter- (and trans-) disciplinary learning and research that transcends the institutional boundaries in the landscape of practice between the arts and sciences (Wenger-Trayner et al. Citation2014). The ‘wicked’ complexity of the world’s forest crisis (intricately entwined as it is with the climate emergency) demands a holistic, rather than a scientific solution. We must continue to nurture the culture in silviculture.

It is perhaps appropriate to give the very last words in this poetic inquiry to participants in a session about yew, the last species in the Gaelic tree alphabet.

Questions asked to trees, and their answers

What’s the greatest hope you have for the future?

For all to vibrate quietly. To be known. To listen.

What does the sun taste like?

Sweet and lemony, warm and mellow.

What is your favourite music?

Birdsong - woodwind breath - the voice of a true heart.

Why are we here?

I am here to give you strength, solace and shelter.

What would you tell humans to give them some much needed wisdom?

Stop for a while and listen to the trees.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was partly funded by Scottish Forestry and the Learning and Teaching Academy. Thanks are due to the participants in all A-B-Tree project events, particularly for the words they have written on leaves and the poems they have shared.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mandy Haggith

Mandy Haggith started her academic career with a PhD in artificial intelligence, then was a forest activist for twenty years, before returning to academia in 2018 as a lecturer in literature and creative writing at the University of the Highlands and Islands. She is the author of five novels, four poetry collections and a non-fiction book, and editor of a tree poetry anthology.

References

- Barrett, T. 2011. “Breakthroughs in Action Research through Poetry.” Educational Action Research 19 (1): 5–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2011.547393.

- Blamires, S. 1997. Celtic Tree Mysteries. St. Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications.

- DeFries, R., and H. Nagendra. 2017. “Ecosystem Management as a Wicked Problem.” Science 356 (6335): 265–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1950.

- Derrida, J. 1976. Of Grammatology. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

- Edlin, H. L. 1950. “The Gaelic Alphabet of Tree Names.” Scottish Forestry 4 (3): 72–75.

- Faulkner, S. L. 2017. “Poetic Inquiry: Poetry As/in/for Social Research.” In Handbook of Arts-based Research, edited by P. Leavy, 208–230. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Fernández-Giménez, M. E., L. B. Jennings, and H. Wilmer. 2019. “Poetic Inquiry as a Research and Engagement Method in Natural Resource Science.” Society & Natural Resources 32 (10): 1080–1091. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2018.1486493.

- Gitlin, A., and M. Peck. 2008. “Educational Poetics: An Aesthetic Approach to Action Research.” Educational Action Research 16 (3): 309–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802260224.

- Graves, R. 1948. The White Goddess. London: Faber and Faber.

- Haggith, M., ed. 2013. Into the Forest. Glasgow: Saraband Books.

- Haggith, M. 2020a. “A-B-Tree: Using Tree Lore and Literature to Support Creative Writing Learners.” Writing in Education 80.

- Haggith, M. 2020b. “Celebrating the Culture in Silviculture.” Scottish Forestry 74 (3): 29–34.

- Kindred, G. 1999. The Tree Ogham. Glennie Kindred Books.

- Lahman, M. K. E., M. R. Geist, K. L. Rodriguez, P. E. Graglia, V. M. Richard, and R. K. Schendel. 2010. “Poking around Poetically: Research, Poetry, and Trustworthiness.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (1): 39–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800409350061.

- Lahman, M. K. E., V. M. Richard, and E. D. Teman. 2019. “Ish: How to Write Poemish (Research) Poetry.” Qualitative Inquiry 25 (2): 215–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417750182.

- Leavy, P. 2015. Method Meets Art. New York: Guildford Press.

- Leggo, C. 1999. “Research as Poetic Rumination: Twenty-six Ways of Listening to Light.” The Journal of Educational Thought 33 (2): 113–133.

- Leggo, C. 2008. “Astonishing Silence: Knowing in Poetry.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research, edited by J. G. Knowles and A. L. Cole, 166–175. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Macfarlane, R. 2016. Landmarks. London: Penguin Books.

- Morton, T. 2010. “Ecology as Text, Text as Ecology.” The Oxford Literary Review 32 (1): 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.3366/olr.2010.0002.

- Murray, L., and C. Murray. 1988. The Celtic Tree Oracle: A System of Divination. New York: St Martin’s Press.

- O’Sullivan, M., and L. Downey. 2014. “Ogham Stones.” Archaeology Ireland (Summer) 26–29.

- Owton, H. 2017. Doing Poetic Inquiry. Milton Keynes: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Peterson, J. D. 2019. “Doing Environmental Humanities: Inter/transdisciplinary Research through an Underwater 360° Video Poem.” Green Letters 23 (1): 68–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14688417.2019.1583592.

- Richardson, L. 2000. “Writing: A Method of Inquiry.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 923–948. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Sutherland, G., and M. Beith. 2000. A’ Chraobh: The Tree. Dornoch: Dornoch Press.

- Vincent, A. 2018. “Is There a Definition? Ruminating on Poetic Inquiry, Strawberries, and the Continued Growth of the Field.” Art/Research International 3 (2): 48–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.18432/ari29356.

- Watkins, A., and Z. Tehrani. 2020. “Brave New Worlds: Transcending the Humanities/STEM Divide through Creative Writing.” Honors in Practice 16: 29–51.

- Wenger-Trayner, E., M. Fenton-O’Creavy, S. Hutchison, C. Kubiak, and B. Wenger-Trayner, eds. 2014. Learning in Landscapes of Practice: Boundaries, Identity, and Knowledgeability in Practice-based Learning. London: Routledge.