ABSTRACT

The Paris Agreement establishes provisions for using international carbon market mechanisms to achieve climate mitigation contributions. Environmental integrity is a key principle for using such mechanisms under the Agreement. This paper systematically identifies and categorizes issues and options to achieve environmental integrity, including how it could be defined, what influences it, and what approaches could mitigate environmental integrity risks. Here, environmental integrity is assumed to be ensured if the engagement in international transfers of carbon market units leads to the same or lower aggregated global emissions. Four factors are identified that influence environmental integrity: the accounting for international transfers; the quality of units generated, i.e. whether the mechanism ensures that the issuance or transfer of units leads to emission reductions in the transferring country; the ambition and scope of the mitigation target of the transferring country; and incentives or disincentives for future mitigation action, such as possible disincentives for transferring countries to define future mitigation targets less ambitiously or more narrowly in order to sell more units. It is recommended that policy-makers combine several approaches to address the significant risks to environmental integrity.

Key policy insights

Robust accounting is a key prerequisite for ensuring environmental integrity. The diversity of nationally determined contributions is an important challenge, in particular for avoiding double counting and for ensuring that the accounting for international transfers is representative for the mitigation efforts by Parties over time.

Unit quality can, in theory, be ensured through appropriate design of carbon market mechanisms; in practice, existing mechanisms face considerable challenges in ensuring unit quality. Unit quality could be promoted through guidance under Paris Agreement Article 6, and reporting and review under Article 13.

The ambition and scope of mitigation targets is key for the incentive for transferring countries to ensure unit quality because countries with ambitious and economy-wide targets would have to compensate for any transfer of units that lack quality. Encouraging countries to adopt ambitious and economy-wide NDC targets would therefore facilitate achieving environmental integrity.

Restricting transfers in instances of high environmental integrity risk – through eligibility criteria or limits – could complement these approaches.

1. Introduction

International carbon market mechanisms provide flexibility as to where and when greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are reduced, and could thereby reduce the costs of mitigating climate change. This can help countries to adopt more ambitious mitigation targets. If not designed and implemented appropriately, however, international carbon market mechanisms could lead to higher global GHG emissions and could thereby also increase the costs of mitigating climate change.

International carbon market mechanisms have been implemented under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and in bilateral agreements, including the international linking of emissions trading systems and bilateral crediting mechanisms such as the Joint Crediting Mechanism initiated by Japan.

The Paris Agreement establishes a new framework for voluntary cooperation that can involve international carbon market mechanisms to achieve climate mitigation contributions (UNFCCC, Citation2015). Article 6.2 allows countries to use ‘internationally transferred mitigation outcomes’ (ITMOs) to achieve their nationally determined contributions (NDCs), while Article 6.4 establishes a new crediting mechanism under international oversight. Environmental integrity is a key principle of Article 6 and the Paris Agreement.

This paper identifies and categorizes key issues and options for achieving environmental integrity, both for international carbon market mechanisms in general as well as for the specific context of the Paris Agreement. The paper first explores possible options for defining environmental integrity. Drawing upon available research on specific aspects of environmental integrity, the paper then systematically identifies and categorizes what factors influence environmental integrity and how environmental integrity could be undermined. This is followed by a systematic identification and categorization of possible approaches to mitigate environmental integrity risks in the context of the Paris Agreement. Based on this analysis, conclusions and recommendations are provided.

The environmental integrity of international carbon market mechanisms has, so far, mainly been investigated in the context of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Research on the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under Article 12 of the Protocol focussed on the additionality of projects (Cames et al., Citation2017; Erickson, Lazarus, & Spalding-Fecher, Citation2014; Gillenwater, Citation2011; Greiner & Michaelowa, Citation2003; Haya & Parekh, Citation2011; He & Morse, Citation2013; Michaelowa & Purohit, Citation2007; Schneider, Citation2009b; Spalding-Fecher et al., Citation2012; Stua, Citation2013; Trexler, Broekhoff, & Kosloff, Citation2006); the establishment of emission baselines (Bailis, Drigo, Ghilardi, & Masera, Citation2015; Fischer, Citation2005; Kartha, Lazarus, & Bosi, Citation2004; Schneider, Citation2011), including their standardization (Hayashi & Michaelowa, Citation2013; Hermwille, Arens, & Burian, Citation2013; Kartha, Lazarus, & LeFranc, Citation2005; Lazarus, Kartha, Ruth, Bernow, & Dunmire, Citation1999; Spalding-Fecher & Michaelowa, Citation2013) and how national policies should be considered in demonstrating additionality and establishing baselines (Liu, Citation2015; Spalding-Fecher, Citation2013). Other research areas include leakage effects (Calvin et al., Citation2015; Geres & Michaelowa, Citation2002; Kallbekken, Citation2007; Schneider, Lazarus, & Kollmuss, Citation2010; Sonter, Barrett, Moran, & Soares-Filho, Citation2015; Vöhringer, Kuosmanen, & Dellink, Citation2006), monitoring of emission reductions (Shishlov & Bellassen, Citation2016; Warnecke, Citation2014), and how the CDM could provide global net emissions reductions (Chung, Citation2007; Erickson et al., Citation2014; Kollmuss & Lazarus, Citation2011; Schneider, Citation2009a; Vrolijk & Phillips, Citation2013; Warnecke, Wartmann, Höhne, & Blok, Citation2014). Less literature is available on the environmental integrity of Joint Implementation under Article 6 of the Protocol (Kollmuss, Schneider, & Zhezherin, Citation2015; Michaelowa, Citation1998; Schneider & Kollmuss, Citation2015) and International Emissions Trading under Article 17 of the Protocol (Aldrich & Koerner, Citation2012; Tuerk, Fazekas, Schreiber, Frieden, & Wolf, Citation2013).

Relevant research was also conducted in the context of the negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) prior to the adoption of the Paris Agreement. This included mainly research on accounting for international transfers (Hood, Briner, & Rocha, Citation2014; Lazarus, Kollmuss, & Schneider, Citation2014; Levin et al., Citation2015; Prag, Aasrud, & Hood, Citation2011; Prag, Hood, & Barata, Citation2013; Prag, Hood, Aasrud, & Briner, Citation2011; Schneider, Kollmuss, & Lazarus, Citation2015); additionality and baseline setting for new, up-scaled carbon market mechanisms (de Sépibus & Tuerk, Citation2011; Fuessler, Herren, Kollmuss, Lazarus, & Schneider, Citation2014); and governance arrangements (de Sépibus, Sterk, & Tuerk, Citation2013).

The environmental integrity of international carbon market mechanisms has also been studied outside the context of the UNFCCC and its Kyoto Protocol, with a focus on international linking of emissions trading schemes (Beuermann, Bingler, Santikarn, Tänzler, & Thema, Citation2017; Bodansky, Hoedl, Metcalf, & Stavins, Citation2015; Ranson & Stavins, Citation2016; Schneider, Lazarus, Lee, & van Asselt, Citation2017); the incentives for countries to enhance or lower the ambition of mitigation targets if they can engage in international carbon market mechanisms (Carbone, Helm, & Rutherford, Citation2009; Helm, Citation2003; Holtsmark & Sommervoll, Citation2012); and non-governmental crediting programmes (Erickson & Lazarus, Citation2013; Lee, Lazarus, Smith, Todd, & Weitz, Citation2013).

The Paris Agreement provides a new context for ensuring environmental integrity of international carbon market mechanisms. The diversity of NDC targets and less international oversight than under Kyoto Protocol could pose challenges for ensuring environmental integrity. Moreover, countries might implement new types of carbon market mechanisms, such as broad carbon pricing approaches or measures at the sectoral level, which may require new methods for quantifying emission reductions and ensuring environmental integrity.

A practical challenge is that the provisions of the Paris Agreement relating to environmental integrity are relatively general – which could be seen as ‘constructive ambiguity’ in order to achieve consensus – and are interpreted by Parties in different ways. For example, there is no agreement whether and how the international guidance under Article 6.2 should address environmental integrity.

The available research on environmental integrity in the context of the Paris Agreement focuses mainly on specific aspects, in particular accounting for international transfers, the design of crediting mechanisms, governance issues, incentives and disincentives for raising ambition, and the possible transition of the Kyoto mechanisms to the framework of the Paris Agreement (Bodansky et al., Citation2015; Broekhoff, Füssler, Klein, Schneider, & Spalding-Fecher, Citation2017; Cames et al., Citation2016; Greiner, Howard, Chagas, & Hunzai, Citation2017; Hermwille & Obergassel, Citation2018; Howard, Citation2017, Citation2018; Howard, Chagas, Hoogzaad, & Hoch, Citation2017; Kreibich, Citation2018; Kreibich & Hermwille, Citation2016; Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2016; La Hoz Theuer, Schneider, Broekhoff, & Kollmuss, Citation2017; Marcu, Citation2017; Michaelowa et al., Citation2016; Michaelowa & Butzengeiger, Citation2017; Mizuno, Citation2017; Schneider et al., Citation2017; Schneider & La Hoz Theuer, Citation2017; Spalding-Fecher, Citation2017; Spalding-Fecher, Sammut, Broekhoff, & Fuessler, Citation2017; Stavins & Stowe, Citation2017; Warnecke, Höhne, Tewari, Day, & Kachi, Citation2018).

These specific aspects have not yet been assessed and categorized in a systematic manner. This paper analyses the relevant provisions of the Paris Agreement, reviews the relevant literature, and evaluates submissions by Parties to the UNFCCC secretariat (http://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionPortal/Pages/Home.aspx), with a view to defining environmental integrity (Section 2), identifying and categorizing risks to environmental integrity (Section 3), and identifying and categorizing approaches to address them (Section 4). Based on this analysis, conclusions and recommendations are provided (Section 5).

The paper employs specific terminology and makes several assumptions. Mitigation targets communicated in NDCs are referred to as ‘NDC targets’. For simplicity, the term ‘international transfers’ is used to refer to transfers of both mitigation outcomes generated under Article 6.2 and emission reductions resulting from the Article 6.4 mechanism. It is assumed that international mechanisms under Article 6 issue ‘units’ which are expressed as metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e), although the findings of this paper also hold if no formal units were issued. It is further assumed that countries achieve their NDC targets and that units are internationally transferred and used towards achieving NDC targets, and not for other purposes such as voluntary cancellation.

2. How could environmental integrity be defined?

The term ‘environmental integrity’ is used in various UNFCCC decisions and the Paris Agreement but not defined. Article 6.1 and 6.2 of the Paris Agreement refer to ‘promoting’ and ‘ensuring’ environmental integrity. The provisions of the Article 6.4 mechanism do not refer to environmental integrity specifically, but include several elements that aim to safeguard it, such as that mitigation benefits be ‘real, measurable and long term’; that ‘additionality’ be ensured; and that emission reductions be ‘verified and certified by designated operational entities’. Environmental integrity is also referred to in other parts of the Paris Agreement and its decision on adoption (Article 4.13 and paragraphs 92 and 107 of decision 1/CP.21).

Based on a review of submissions and the literature (IPCC, Citation2014; Woerdman, Citation2005), three possible definitions for environmental integrity are identified for the context of Article 6:

Aggregate achievement of mitigation targets: Environmental integrity would be ensured if the engagement in international transfers does not lead to a situation where aggregate actual emissions would exceed the aggregated target level.

No increase in global aggregate emissions: Environmental integrity would be ensured if the engagement in international transfers leads to aggregated global GHG emissions that are no higher as compared to a situation where the transfers did not take place.

Decrease of global emissions: Environmental integrity would be ensured if the engagement in international transfers leads to a decrease in global GHG emissions as compared to a situation where the transfers did not take place.

The first approach would imply that global GHG emissions could increase as a result of engaging in international transfers. It would enable countries to engage in transfers that are not associated with any ‘mitigation outcomes’, as referred to in Article 6.2. This approach also seems inconsistent with the principle in Article 6.1 that cooperation should ‘allow for higher ambition’. The third approach would build on the objective in Article 6.1 to ‘allow for higher ambition’ and that in Article 6.4 to ‘deliver an overall mitigation in global GHG emissions’. However, enhancing ambition and ensuring environmental integrity are two separate concepts in the Paris Agreement. Combining these concepts may be more complex to operationalize and could dilute each of them. In the following, the second definition is therefore employed.

3. What influences environmental integrity?

Various factors influence the global GHG emissions outcome from using international carbon market mechanisms. Drawing on the review of submissions and the literature, four main factors are identified:

Accounting for international transfers;

Quality of units;

Ambition and scope of the mitigation target of the transferring country; and

Incentives or disincentives for future mitigation action.

3.1 Accounting for international transfers

Robust accounting of international transfers is a key prerequisite to ensure environmental integrity: if international transfers are not accounted for robustly, global GHG emissions could increase as a result of the transfers. A lack of robust accounting could undermine environmental integrity in several ways.

First, if emission reductions are double counted, actual global GHG emissions are higher than the sum of what individual countries report. Double counting occurs when a single GHG emission reduction is counted more than once towards achieving mitigation targets. This can occur in three ways (Hood et al., Citation2014; Prag et al., Citation2011; Prag et al., Citation2013; Schneider et al., Citation2015; UNFCCC, Citation2012):

Double issuance occurs if more than one unit is issued for the same emissions or emission reductions.

Double claiming occurs if the same emission reductions are counted twice towards fulfilling targets: by the country where the reductions occur, through reporting of its reduced GHG emissions, and by the country or entity using the units issued for these reductions. It could also occur between national mitigation targets and international mechanisms to address emissions from international aviation or international shipping, such as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO, Citation2016).

Double use occurs if the same issued unit is used twice to achieve a mitigation target.

Second, the time frame of mitigation targets is a critical issue when accounting for international transfers. If the time period in which transferred mitigation outcomes occur – also referred to as the ‘vintage’ of mitigation outcomes – differs from the year or period in which they are used to achieve a mitigation target, cumulative global GHG emissions could increase (Hood et al., Citation2014; Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2016; Lazarus et al., Citation2014; Prag et al., Citation2013; Rich, Bhatia, Finnegan, Levin, & Mitra, Citation2014; Schneider et al., Citation2017). This could, for example, occur if a country uses international transfers from a cumulative mitigation effort over a period to achieve a single-year target.

Third, if countries use different metrics for mitigation targets, such as different values for global warming potentials (GWPs), the international transfer of carbon market units can – if not converted appropriately – increase global GHG emissions.

Lastly, international transfers can involve activities that may result in emission reductions or removals that are only temporary, such as in the land-use, land-use change and forestry sector or in the case of geological storage of CO2. If reversals of emission reductions or removals are not appropriately accounted for, cumulative global GHG emissions could increase.

Under the Paris Agreement, the diversity of NDCs is a key challenge for ensuring robust accounting for international transfers. Mitigation commitments under the Kyoto Protocol were economy-wide and expressed in absolute amounts of GHG emissions. They were also based on common multi-year periods, GHGs and GWP values. Under the Paris Agreement, however, countries communicated a variety of mitigation targets in their NDCs. Some targets are not economy-wide but cover only some sectors, gases, activities or geographical areas. The absolute level of GHG emission targets is not always clear, in particular when targets represent a deviation from a business as usual emissions pathway that could be updated in the future. Many countries communicated also targets in metrics other than GHG emissions, such as targets for renewable energy deployment. Most countries communicated only targets for a specific year and not a period, and countries use different GWP values (Graichen, Cames, & Schneider, Citation2016). If countries with different target metrics, target years or GWP values engage in international transfers, this could lead to higher global GHG emissions.

A further challenge specific to the Paris Agreement is that many NDCs include targets that are ‘conditional’ on support from other countries, sometimes in combination with less ambitious ‘unconditional’ targets. Some countries have stated in their NDC that such support could include the use of international market mechanisms. If, however, the same emission reductions are used to achieve both the conditional NDC of the transferring country as well as the NDC of the supporting country, this constitutes double claiming and leads to a weakening of overall ambition, compared to a situation where support is provided through forms of climate finance, in which the supporting country does not use the emission reductions to achieve its own NDC.

3.2. Quality of units

International carbon market mechanisms typically issue units which can be transferred through registries. Here, units are defined as having quality if the underlying mechanism ensures that the issuance or transfer of one unit, expressed as 1 tCO2e, directly leads to an emission reduction of at least 1 tCO2e in the transferring country, compared to the situation in the absence of the mechanism. Hence, here the direct emissions outcome from the underlying mechanism is considered, independently of other more indirect factors, such as the ambition and scope of the mitigation target of the transferring country.

The factors that influence the unit quality vary according to the type of mechanism.

Under crediting mechanisms, the quality of credits is, in principle, ensured if the mitigation action is additional – that is, it would not occur in the absence of the incentives from the crediting mechanism – and if the emission reductions are not overestimated. Ensuring that emission reductions are not overestimated involves several aspects, including that the emission reductions be real, measurable and attributable to the credited activity and that indirect emission effects be appropriately considered.

In a market situation where the supply of credits considerably exceeds demand, however, the GHG emissions impact from creating further demand for credits is more complex. If in such a market situation projects have already been implemented – and hence investment costs are sunk – a key consideration for the global GHG emissions impact is whether the projects would continue to reduce GHG emissions even without credit revenues, or whether they are at risk of discontinuing GHG abatement (Schneider & La Hoz Theuer, Citation2017; Warnecke et al., Citation2017).

Under emission trading systems (ETSs), the quality of allowances mainly depends on whether the ETS cap is set below the emissions level that would occur in the absence of the trading system, and whether emissions are monitored appropriately. Other design features, such as price collars, allowance reserves, import of credits, and provisions for banking of allowances, also affect unit quality – mainly by altering the cap. If an ETS with an ambitious cap is linked to one that is over-allocated, linking could reduce aggregated abatement from both systems (Green, Sterner, & Wagner, Citation2014).

The Paris Agreement could also enable direct bilateral government-to-government transfers, without using a crediting mechanism or linking ETSs, akin to transfers of assigned amount units (AAUs) under Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol. In some instances, these transfers could be underpinned by mechanisms: under the Kyoto Protocol, for example, countries established Green Investment Schemes (GISs) under which revenues from international transfers of AAUs were invested in activities designed to assist climate change mitigation (Tuerk et al., Citation2013). Where mitigation outcomes from specific mitigation actions are transferred, the quality of the transferred units hinges on similar criteria as for crediting mechanisms. Where direct bilateral transfers occur without implementing any mitigation action, the transferred units would not have quality.

3.3. Ambition and scope of the mitigation target of the transferring country

The mitigation target of a transferring country can affect the global GHG emissions impact of international transfers indirectly, because the target's scope and ambition may determine whether the transfer of units that lack quality impacts the country's efforts in achieving its target. Assume a country that issues units lacking quality. The units are issued for emission reductions that fall within the scope of the country's target and are transferred to another country which uses them to achieve its target. If the transferring country has an ambitious target – which requires the country to pursue further mitigation action to achieve its target – it may have to compensate for the transfer in order to still achieve its target, either by further reducing emissions or by purchasing units. The country thus has an incentive to ensure that units generated by mechanisms have quality. The same may not be true, however, for a country with a target that is less stringent than its business-as-usual (BAU) emissions – i.e. which does not require the country to take mitigation action to achieve its target – or for units issued for emissions or emission reductions that fall outside the scope of the target. In these instances, the country might accrue more financial revenues from over-estimating emissions reductions and selling the resulting units, without infringing its ability to achieve its target.

The more ambitious a mitigation target is, the more likely it is that a country would compensate for the transfer of units that lack quality and therefore only authorize the transfer of quality units. This is supported by evidence from Joint Implementation under the Kyoto Protocol where units from countries with ambitious Kyoto Protocol targets were assessed to have a significantly higher quality than those from countries with targets less stringent than the likely BAU emissions (Kollmuss et al., Citation2015). Whether a country compensates for a lack of unit quality and has incentives to ensure unit quality may also depend on when transfers are made. Before the target year or period, the country may not have certainty whether it will achieve its target and may thus be cautious in authorizing projects. However, once over-achievement of the target becomes certain, the country may have less incentive to ensure unit quality because it may no longer have to compensate for the transfer of units that lack quality.

Under the Paris Agreement, a key challenge is that countries self-determine the ambition and scope of their mitigation targets. Independent evaluations indicate that the ambition of current NDC targets varies strongly, despite the uncertainties and limitations in assessing such ambition. A number of countries are projected to significantly over-achieve their NDC targets with current policies in place. Moreover, the scope of many NDC targets is limited to some gases or sectors (Aldy & Pizer, Citation2016; CAT, Citation2017; Höhne, Fekete, den Elzen, Hof, & Takeshi, Citation2018; La Hoz Theuer et al., Citation2017; Meinshausen & Alexander, Citation2017; Rogelj et al., Citation2016).

Two important conclusions can be drawn from these considerations. First, a lack of unit quality is critical in two situations: if the emission sources are not included within the scope of a mitigation target, or if the transferring country has a target that does not require further mitigation action. Second, the ambition and scope of targets is key for the incentive to ensure unit quality. Encouraging countries to adopt ambitious and economy-wide NDC targets may therefore also facilitate achieving environmental integrity under Article 6.

3.4. Incentives or disincentives for future mitigation action

International carbon markets could lower the cost of mitigation, and thereby enable countries to adopt more ambitious mitigation targets. Article 6.1 of the Paris Agreement explicitly envisages that the engagement of countries in international transfers allows for ‘higher ambition’ in their mitigation actions. In practice, however, the possibility to engage in international carbon market mechanisms could provide both incentives and disincentives for future mitigation action – and thereby indirectly affect GHG emissions both positively and negatively.

For acquiring countries, using international carbon markets could lower the costs of achieving their targets, and thereby enable these countries to adopt more ambitious targets. Yet for transferring countries, the possibility to use international carbon markets could create incentives to set mitigation targets at unambitious levels, or to define their scope narrowly, in order to accrue more benefits from transferring units internationally (Carbone et al., Citation2009; Green, Citation2016; Helm, Citation2003; Holtsmark & Sommervoll, Citation2012; Howard, Citation2018; Spalding-Fecher, Citation2017; Warnecke et al., Citation2018).

International carbon market mechanisms could also affect mitigation efforts in more indirect ways:

Implementing market mechanisms could help to build capacity and increase awareness of climate issues, which might lead to enhanced mitigation efforts in the future (Spalding-Fecher et al., Citation2012).

Under crediting mechanisms, transferring countries could have perverse incentives not to adopt mitigation policies, because such policies might lower the potential for generating and exporting credits (Liu, Citation2015; Spalding-Fecher, Citation2013; Strand, Citation2011). This poses a dilemma: if crediting mechanisms require project developers to consider mitigation policies and regulations in the demonstration of additionality, they may discourage policy-makers from adopting such policies. If they allow project developers to ignore mitigation policies and regulations, they may credit activities that are not additional, because they would be implemented anyway due to the policies and regulations.

Crediting mechanisms could also create perverse incentives for project developers to pursue a more GHG-intensive course of action, so that the baseline from which emission reductions are credited is higher (Schneider, Citation2011; Schneider & Kollmuss, Citation2015).

Depending on how carbon market mechanisms are implemented, market participants could favour mitigation actions that are cost-effective in the short and medium term, and neglect mitigation actions that are costlier but foster transformational change and avoid lock-in of more carbon-intensive technologies. For example, crediting landfill gas capture could provide incentives to continue pursuing landfilling, while other waste management practices, such as composting or recycling, would lead to lower GHG emissions.

4. Addressing environmental integrity under the Paris Agreement

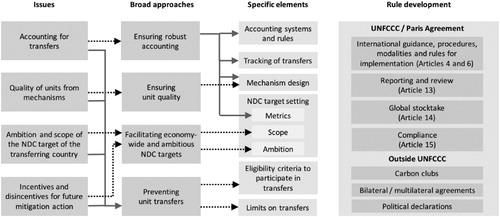

Environmental integrity could be addressed in different ways, which are clustered here into four broad approaches: robust accounting; ensuring unit quality; facilitating economy-wide and ambitious mitigation targets; and restricting international transfers. Here we discuss how these four approaches could be implemented in the context of the Paris Agreement. For each approach, specific elements to implement it are identified and briefly discussed (). The effectiveness and the political and practical feasibility of the approaches may strongly hinge on how they would be implemented and is subject to further research.

4.1. Robust accounting

The Paris Agreement and decision 1/CP.21 include several provisions to achieve robust accounting: Article 4.13 requires countries to ‘account for their NDCs’. Article 6.2 requires countries engaging in international transfers to ‘apply robust accounting to ensure, inter alia, the avoidance of double counting’. Article 6.5 requires that emission reductions resulting from the Article 6.4 mechanism be used by only one Party to achieve its NDC. This is complemented by the transparency framework in Article 13, which requires countries to track progress towards achieving NDCs, and the global goals of the Paris Agreement.

Accounting for NDCs is an important prerequisite for accounting for international transfers. This requires that NDC targets are clearly defined (e.g. with regard to their geographical coverage, the emissions sources and GHGs included and the time frame covered); that they are expressed in quantifiable terms (e.g. GHG emissions or megawatts of renewable power capacity); that the target level be clearly specified (e.g. in relation to historical data or a BAU emissions path); and that progress towards NDC targets be tracked.

Accounting for international transfers requires several additional elements to be implemented. Establishing an accounting system and accounting rules for international transfers is a central element, in particular to avoid double claiming and to ensure that the accounting for international transfers is representative of the mitigation efforts by Parties over time.

Paragraph 36 of decision 1/CP.21 envisages that double claiming be avoided on the basis of ‘corresponding adjustments’ for emissions or removals. Corresponding adjustments could be applied to reported emission totals or to an emissions budget that reflects the emissions level of the NDC target, similar to the ‘assigned amounts’ established under the Kyoto Protocol. Both approaches avoid double claiming and imply that the transferring country would, for each unit transfer, need to reduce its emissions below its NDC target. Corresponding adjustments could be applied to transferring countries in two ways: either they are only applied if the emission reductions fall within the scope of the NDC target, or they are applied in an all cases, regardless of the scope of the transferring country. And they could apply to international transfers in the context of both Article 6.2 and Article 6.4, or different approaches could be employed for international transfers of emission reductions generated under the Article 6.4 mechanism (Howard et al., Citation2017; Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2016; Schneider et al., Citation2017; Spalding-Fecher, Citation2017).

Several practical challenges arise from the diversity of current NDCs. Targets in non-GHG metrics could be accounted for by applying adjustments in the respective metric of that target. For example, if a country has a target of installing 100 Megawatt of renewable power capacity and authorizes the international transfer of emission reductions from a 5 Megawatt wind power project, it could apply an adjustment of 5 Megawatt to its reported progress in achieving its renewable power target (Schneider et al., Citation2017).

Countries that communicated a target range would need to clarify which target is used as basis for accounting for international transfers. If double claiming should be avoided also with regard to conditional targets, international market mechanisms could still be used, but only if the acquiring country does not use emission reductions that are also counted towards achievement of the transferring country's NDC.

A critical element is appropriate accounting for the time frame of mitigation targets and when the mitigation outcomes occurred. In contrast to the Kyoto Protocol, many NDCs only include single-year targets. Carbon market mechanisms, however, typically issue units for multi-year periods. Several options could be pursued to address this challenge: (a) using continuous multi-year target trajectories or budgets, such as under the Kyoto Protocol, (b) accounting for transfers only in common single-year targets, or (c) approaches to make the transfers of mitigation outcomes representative over time, such as averaging transfers over defined time periods (Howard et al., Citation2017; Lazarus et al., Citation2014; Prag et al., Citation2013; Schneider et al., Citation2017).

Other necessary elements for accounting for international transfers include systems to track international transfers, such as electronic registries or international transaction logs, as they were for example implemented under the Kyoto Protocol; appropriate design of market mechanisms in order to avoid double issuance of units; and the use of common metrics (e.g. GWPs), as envisaged in paragraph 31a of decision 1/CP.21.

4.2. Ensuring unit quality

Under the Paris Agreement, unit quality could be addressed through the rules, modalities and procedures of Article 6.4 and through international guidance on Article 6.2, though Parties have different views on whether the latter should address environmental integrity issues other than robust accounting (Obergassel & Asche, Citation2017). Including provisions on unit quality in the guidance under Article 6.2 may help to prevent a situation where countries evade requirements under Article 6.4 by transferring units with less quality under Article 6.2 instead (Michaelowa et al., Citation2016). Countries could also be required to report on how they ensure unit quality, and the reported information could be reviewed under Article 13.

Ensuring unit quality requires appropriate design of carbon market mechanisms. In practice, ensuring unit quality could be challenging, in particular if international guidance is general and vague. Crediting mechanisms face challenges in assessing additionality and emissions baselines, mainly due to the information asymmetry between project developers and regulators, and uncertainty of assumptions on future developments, such as international fuel prices (Cames et al., Citation2017; Fischer, Citation2005; Gillenwater, Citation2011; Kollmuss et al., Citation2015; Schneider, Citation2009b; Spalding-Fecher et al., Citation2012). Another challenge inherent to the concept of crediting is that offsets subsidize the deployment of low-emitting technologies rather than penalizing the deployment of high-emitting technologies. As a consequence, offsets lower the costs of energy (or other commodities or services), which can lead to greater use of energy (or other commodities or services). Such effects, also referred to as ‘market leakage’, are commonly not accounted for under existing crediting mechanisms, and may thus lead to an overestimation of emission reductions (Calvin et al., Citation2015; Kallbekken, Citation2007; Vöhringer et al., Citation2006). The ambition of ETSs also varies, and several existing ETSs face challenges with surplus allowances (Haites, Citation2018; Narassimhan, Gallagher, Koester, & Alejo, Citation2018). Ensuring unit quality for new types of mechanisms, such as broad carbon pricing policies or measures at the sectoral level, may require new approaches such as modelling or extensive data collection. Exchange rates, discount rates, and GISs have been used or proposed as means to mitigate concerns over varying unit quality, but these approaches also face challenges (Macinante, Citation2015; Marcu, Citation2015; Schneider et al., Citation2017; Tuerk et al., Citation2013).

4.3. Facilitating economy-wide and ambitious mitigation targets

Article 4.3 of the Paris Agreement calls for a ‘progression’ of NDCs reflecting the ‘highest possible ambition’, and Article 4.4 encourages developing countries to move over time towards economy-wide targets. While these provisions guide Parties, NDCs are ultimately self-determined by them. Parties could, however, decide to establish participation requirements for engagement in international transfers under Article 6 that provide incentives for countries to expand the scope of their NDCs, such as by limiting international transfers to emission reductions generated from sectors or gases covered by the NDC of the transferring country or, alternatively, by requiring that countries commit to expand the scope of their NDCs to economy-wide targets in the future in order to participate in Article 6. Enhancing the ambition and scope of NDC targets could also be facilitated indirectly, such as through guidance on transparency and understanding of NDCs under Article 4.8, reporting and review under the transparency framework under Article 13, the global stocktake under Article 14, or the mechanism to facilitate implementation and promote compliance under Article 15.

4.4. Restricting international transfers

Approaches that restrict international transfers are not included in the Paris Agreement but were proposed by some Parties and are being considered in the negotiations of the rulebook for the Paris Agreement. International transfers could be restricted in situations where risks to environmental integrity are considered higher, for example, if a system to account for international transfers is not in place, if the units were issued under a mechanism without international oversight, or if the emission reductions were generated outside the scope an NDC target. The latter approach could partially also address concerns that countries could have perverse incentives to set future NDC targets unambitiously or to define their scope narrowly, in order to sell more units; if transfers were effectively prevented in such situations, these countries would have less benefits from setting targets unambitiously or narrowly.

International transfers could be restricted in two ways:

Eligibility criteria could require countries to meet certain requirements before they can participate in international transfers under Article 6. Countries could, for example, be required to have an accounting system in place or to have demonstrated that their mechanisms comply with internationally agreed principles on unit quality.

Limits on international transfers could reduce or, in some instances, prevent international transfers. Limits could be established with the aim of (a) generally reducing the amount of international transfers and thereby limit detrimental effects on unit quality, or (b) addressing specific environmental integrity risks, such as preventing transfers from countries with targets levels below BAU emissions while allowing countries with ambitious NDC targets to engage in transfers without limitations (La Hoz Theuer, Schneider, & Broekhoff, Citation2018).

Both limits and eligibility criteria were established under the Kyoto Protocol but were mainly used to ensure robust accounting and did not specifically address the quality of units or ambition of mitigation targets. The ‘commitment period reserve’ limited the extent to which countries could transfer units and mainly addressed the risk of over-selling. Eligibility requirements to participate in international carbon markets focussed on reporting of GHG inventories and the establishment of registry infrastructure (Yamin & Depledge, Citation2004).

4.5. International rules versus responsibility by countries

A key question in the negotiations on the rulebook for the Paris Agreement is to what extent environmental integrity will be addressed through international rules and how much responsibility will lie with the Parties engaging in international transfers. All the approaches identified above could be implemented through international rules or under the responsibility of countries. Some authors also caution against establishing onerous international requirements that could dampen incentives for ambitious international cooperation (Mehling, Metcalf, & Stavins, Citation2018).

In either case, international reporting and review under Article 13 of the Agreement could help enhance transparency, and thereby provide incentives for countries to ensure environmental integrity and address any shortcomings in response to review findings.

If international rules are not deemed sufficient, countries could address environmental integrity issues by forming ‘carbon clubs’ or committing to political declarations (Keohane, Petsonk, & Hanafi, Citation2017). Yet these approaches can only address environmental integrity by the participating countries, which may limit their effectiveness.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

This paper has identified and categorized environmental integrity risks of international carbon market mechanisms and ways to overcome them under the Paris Agreement.

The risks for environmental integrity are notable. The diverse scope, metrics, types and timeframes of NDC targets pose challenges for robust accounting. The experience with existing carbon market mechanisms suggests that ensuring unit quality can be challenging. The diverse ambition and the limited scope of some NDCs reduces the incentives that countries have for ensuring unit quality. The literature also suggests that there is a material risk of countries choosing targets less ambitiously or more narrowly in order to sell more carbon market units.

Addressing these risks is challenging but important. If environmental integrity is not ensured, international carbon market mechanisms do not achieve their objectives – they would neither reduce emissions nor cut the costs of mitigating climate change. This paper identified four broad approaches to address environmental integrity risks.

Robust accounting is a key prerequisite for ensuring environmental integrity. It would be greatly facilitated if countries move towards economy-wide GHG emissions targets based on continuous multi-year periods and common GWPs. Relevant decisions under the Paris Agreement could encourage or require countries to adopt such types of targets in future NDCs if they wish to engage in international transfers. With regard to current NDCs, it is recommended that international guidance specifically address how and when corresponding adjustments should be applied, how international transfers should be accounted for in the case of single-year targets and targets in metrics other than GHG emissions, and how international transfers should be transparently tracked and reported upon. Given that significant demand for carbon market units could arise from CORSIA, it is also important that double counting is effectively avoided between NDCs under the Paris Agreement and offsetting obligations by airline operators under CORSIA.

The adoption of ambitious and economy-wide targets significantly reduces environmental integrity risks. Although NDCs are ultimately self-determined by Parties, the adoption of such targets could be facilitated through a range of measures, including through international guidance on clarity, transparency and understanding of NDCs, or the global stocktake referred to in Article 14 of the Paris Agreement.

The available experience suggests that ensuring unit quality can be challenging in practice. The environmental integrity risks may, however, differ between mechanisms and activities. Countries could prioritize carbon market mechanisms or activities that pose lower risks to environmental integrity, such as internationally linking emissions trading systems with similar ambition levels.

Restricting transfers in instances of higher environmental integrity threats could serve as a safeguard and mitigate other environmental integrity risks, but may also face practical challenges and constraints.

The feasibility and practical implementation of these four broad approaches is subject to further research. Which of these approaches – or combinations – are effective may depend on how they are implemented. For example, vague international guidance on unit quality and weak governance arrangements to ensure adherence may not affect the type and scale of transfers countries engage in. Whether an approach is effective may thus largely depend on the political feasibility of designing it in a meaningful manner.

Given that environmental integrity risks are significant, that each of the approaches faces challenges and limitations, and that the identified approaches can be complementary rather than mutually exclusive, it is recommended that policy-makers pursue all four broad approaches to promote environmental integrity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Lambert Schneider http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5704-0965

Stephanie La Hoz Theuer http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5606-655X

References

- Aldrich, E. L., & Koerner, C. L. (2012). Unveiling assigned amount unit (AAU) trades: Current market impacts and prospects for the future. Atmosphere, 3(1), 229–245. doi: 10.3390/atmos3010229

- Aldy, J. E., & Pizer, W. A. (2016). Comparing emissions mitigation efforts across countries. Climate Policy, 17(4), 501–515. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2015.1119098

- Bailis, R., Drigo, R., Ghilardi, A., & Masera, O. (2015). The carbon footprint of traditional woodfuels. Nature Climate Change, 5(3), 266–272.

- Beuermann, C., Bingler, J., Santikarn, M., Tänzler, D., & Thema, J. (2017). Considering the effects of linking emissions trading schemes: A manual on bilateral linking of ETS. Umweltbundesamt. Retrieved from https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/emissions-trading/Linking_manual.pdf?_blob=publicationFile&v=3

- Bodansky, D., Hoedl, S. A., Metcalf, G. E., & Stavins, R. N. (2015). Facilitating linkage of climate policies through the Paris outcome. Climate Policy, 3062(November), 1–17.

- Broekhoff, D., Füssler, J., Klein, N., Schneider, L., & Spalding-Fecher, R. (2017). Establishing scaled-up crediting program baselines under the Paris Agreement: Issues and options. Washington DC. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28785

- Calvin, K., Rose, S., Wise, M., McJeon, H., Clarke, L., & Edmonds, J. (2015). Global climate, energy, and economic implications of international energy offsets programs. Climatic Change, 133(4), 583–596.

- Cames, M., Harthan, R., Füssler, J., Lazarus, M., Lee, C., Erickson, P., & Spalding-Fecher, R. (2017). How additional is the clean development mechanism? Analysis of the application of current tools and proposed alternatives. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/clima/sites/clima/files/ets/docs/clean_dev_mechanism_en.pdf

- Cames, M., Healy, S., Tänzler, D., Li, L., Melnikova, J., Warnecke, C., & Kurdziel, M. (2016). International market mechanisms after Paris. German Emissions Trading Authority (DEHSt) at the German Environment Agency. Retrieved from https://newclimateinstitute.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/international_market_mech_after_paris_discussion_paper.pdf

- Carbone, J. C., Helm, C., & Rutherford, T. F. (2009). The case for international emission trade in the absence of cooperative climate policy. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 58(3), 266–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2009.01.001

- CAT. (2017). Tracking (I)NDCs: Assessment of mitigation contributions to the Paris Agreement. Retrieved from http://climateactiontracker.org/countries.html

- Chung, R. K. (2007). A CER discounting scheme could save climate change regime after 2012. Climate Policy, 7(2007), 171–176. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2007.9685647

- de Sépibus, J., Sterk, W., & Tuerk, A. (2013). Top-down, bottom-up or in-between: How can a UNFCCC framework for market-based approaches ensure environmental integrity and market coherence? (No. 2012/31 – July 2012).

- de Sépibus, J., & Tuerk, A. (2011). New market-based mechanisms post-2012: Institutional options and governance challenges when establishing a sectoral crediting mechanism. Retrieved from http://www.nccr-climate.unibe.ch/research_articles/working_papers/papers/paper201106.pdf

- Erickson, P., & Lazarus, M. (2013). Implications of international GHG offsets on global climate change mitigation. Climate Policy, 13(4), 433–450. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2013.777632

- Erickson, P., Lazarus, M., & Spalding-Fecher, R. (2014). Net climate change mitigation of the clean development mechanism. Energy Policy, 72, 146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2014.04.038

- Fischer, C. (2005). Project-based mechanisms for emissions reductions: Balancing trade-offs with baselines. Energy Policy, 33(14), 1807–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2004.02.016

- Fuessler, J., Herren, M., Kollmuss, A., Lazarus, M., & Schneider, L. (2014). Crediting emission reductions in new market based mechanisms – Part II: Additionality assessment & baseline setting under pledges. Retrieved from http://www.infras.ch/e/projekte/displayprojectitem.php?id=5183

- Geres, R., & Michaelowa, A. (2002). A qualitative method to consider leakage effects from CDM and JI projects. Energy Policy, 30(6), 461–463. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4215(01)00113-6

- Gillenwater, M. (2011). What is additionality? Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://ghginstitute.org/research/

- Graichen, J., Cames, M., & Schneider, L. (2016). Categorization of INDCs in the light of Art. 6 of the Paris Agreement. Berlin. Retrieved from https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/project-mechanisms/Categorization_of_INDCs_Paris_agreement_discussion_paper.html

- Green, J. F. (2016). Don’t link carbon markets. Nature, 543, 484–486. doi: 10.1038/543484a

- Green, J. F., Sterner, T., & Wagner, G. (2014). A balance of bottom-up and top-down in linking climate policies. Nature Climate Change, 4(12), 1064–1067. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2429

- Greiner, S., Howard, A., Chagas, T., & Hunzai, T. (2017). CDM transition to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Retrieved from http://www.climatefocus.com/publications/cdm-transition-article-6-paris-agreement-options-report

- Greiner, S., & Michaelowa, A. (2003). Defining investment additionality for CDM projects – practical approaches. Energy Policy, 31(10), 1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4215(02)00142-8

- Haites, E. (2018). Carbon taxes and greenhouse gas emissions trading systems: What have we learned? Climate Policy, 18(8), 955–966. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1492897

- Haya, B., & Parekh, P. (2011). Hydropower in the CDM: Examining additionality and criteria for sustainability (Energy and Resources Group Working Paper ERG-11-001). Berkeley Energy and Resources Group Working Paper. Berkeley. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2120862

- Hayashi, D., & Michaelowa, A. (2013). Standardization of baseline and additionality determination under the CDM. Climate Policy, 13(2), 191–209. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2013.745114

- He, G., & Morse, R. (2013). Addressing carbon offsetters’ paradox: Lessons from Chinese wind CDM. Energy Policy, 63, 1051–1055. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257068805_Addressing_carbon_Offsetters_Paradox_Lessons_from_Chinese_wind_CDM

- Helm, C. (2003). International emissions trading with endogenous allowance choices. Journal of Public Economics, 87(12), 2737–2747. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00138-X

- Hermwille, L., Arens, C., & Burian, M. (2013). Recommendations on the advancement of the CDM Standardized Baselines Framework. Retrieved from https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/project-mechanisms/CDM_Discussion_Paper_Standardised_Baselines.pdf?_blob=publicationFile&v=1

- Hermwille, L., & Obergassel, W. (2018). Additionality après Paris. Stronghold for Environmental Integrity?, Wuppertal. https://epub.wupperinst.org/frontdoor/index/index/searchtype/all/start/1/rows/10/has_fulltextfq/true/docId/7124

- Höhne, N., Fekete, H., den Elzen, M. G. J., Hof, A. F., & Takeshi, K. (2018). Assessing the ambition of post-2020 climate targets: a comprehensive framework. Climate Policy, 18(4), 425–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1294046

- Holtsmark, B., & Sommervoll, D. E. (2012). International emissions trading: Good or bad? Economics Letters, 117(1), 362–364. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2012.05.034

- Hood, C., Briner, G., & Rocha, M. (2014). GHG or not GHG: Accounting for diverse mitigation contributions in the post-2020 climate framework. Climate Change Expert Group (Vol. 2014). Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/env/cc/GHG or not GHG_CCXGsentout_May2014_REV.pdf

- Howard, A. (2017). Voluntary cooperation (Article 6). In D. Klein, M. P. Carazo, M. Doelle, J. Bulmer, & A. Higham (Eds.), The Paris Agreement on climate change: Analysis and commentary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-paris-agreement-on-climate-change-9780198789338?cc=de&lang=en&#

- Howard, A. (2018). Incentivizing mitigation: Using international carbon markets to raise ambition. Retrieved from: https://www.carbonmechanisms.de/fileadmin/media/dokumente/Publikationen/Studie/Studie_2018_KoruClimate_Incentivizing.pdf

- Howard, A., Chagas, T., Hoogzaad, J., & Hoch, S. (2017). Features and implications of NDCs for carbon markets. Retrieved from http://www.climatefocus.com/publications/features-and-implications-ndcs-carbon-markets-final-report

- ICAO. (2016). Assembly Resolution A39-22. Retrieved from https://www.icao.int/Meetings/a39/Documents/WP/wp_193_en.pdf

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. Working Group III contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (O. Edenhofer, R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, … J. C. Minx, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/

- Kallbekken, S. (2007). Why the CDM will reduce carbon leakage. Climate Policy, 7(3), 197–211. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2007.9685649

- Kartha, S., Lazarus, M., & Bosi, M. (2004). Baseline recommendations for greenhouse gas mitigation projects in the electric power sector. Energy Policy, 32(4), 545–566. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4215(03)00155-1

- Kartha, S., Lazarus, M., & LeFranc, M. (2005). Market penetration metrics: Tools for additionality assessment? Climate Policy, 5(2), 147–165. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2005.9685547

- Keohane, N., Petsonk, A., & Hanafi, A. (2017). Toward a club of carbon markets. Climatic Change, 144(1), 81–95. doi: 10.1007/s10584-015-1506-z

- Kollmuss, A., & Lazarus, M. (2011). Discounting offsets: Issues and options. Carbon Management, 2(5), 539–549. doi: 10.4155/cmt.11.49

- Kollmuss, A., Schneider, L., & Zhezherin, V. (2015). Has joint implementation reduced GHG emissions? Lessons learned for the design of carbon market mechanisms (Working Paper No. 2015-07). Stockholm. Retrieved from http://www.sei-international.org/publications?pid=2803

- Kreibich, N. (2018). Raising ambition through cooperation. Using Article 6 to bolster climate change mitigation, Wuppertal. https://epub.wupperinst.org/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/7122/file/7122_Raising_Ambition.pdf

- Kreibich, N., & Hermwille, L. (2016). Robust transfers of mitigation outcomes: Understanding environmental integrity challenges (JIKO Policy Paper No. 02/2016). Wuppertal. Retrieved from http://www.carbon-mechanisms.de/fileadmin/media/dokumente/publikationen/PP_2016_02_Robust_Transfers_bf.pdf

- Kreibich, N., & Obergassel, W. (2016). Carbon markets after Paris. How to account for the transfer of mitigation results? (JIKO Policy paper No. 01/2016). Wuppertal.

- La Hoz Theuer, S., Schneider, L., & Broekhoff, D. (2018). International transfers under Article 6 in the context of diverse ambition of NDCs. Environmental integrity risks and options to address them. Climate Policy. Retrieved from https://www.sei.org/publications/international-transfersarticle-6-ndcs/

- La Hoz Theuer, S., Schneider, L., Broekhoff, D., & Kollmuss, A. (2017). International transfers under Article 6 in the context of diverse ambition of NDCs. Environmental integrity risks and options to address them (Working Paper No. 2017–10). Stockholm. Retrieved from https://www.sei-international.org/publications?pid=3248

- Lazarus, M., Kartha, S., Ruth, M., Bernow, S., & Dunmire, C. (1999). Evaluation of benchmarking as an approach for establishing clean development mechanism baselines. Boston. Retrieved from https://www.sei-international.org/mediamanager/documents/Publications/Climate/evaluation_benchmarking_cleandev_mechanism.pdf

- Lazarus, M., Kollmuss, A., & Schneider, L. (2014). Single-year mitigation targets: Uncharted territory for emissions trading and unit transfers (Working Paper No. 2014-01). Stockholm. Retrieved from https://www.sei-international.org/publications?pid=2487

- Lee, C. M., Lazarus, M., Smith, G. R., Todd, K., & Weitz, M. (2013). A ton is not always a ton: A road-test of landfill, manure, and afforestation/reforestation offset protocols in the U.S. carbon market. Environmental Science and Policy, 33, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.05.002

- Levin, K., Rich, D., Finnegan, J., Barata, P. M., Dagnet, Y., & Kulovesi, K. (2015). Accounting framework for the post-2020 period. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. Retrieved from doi:10.6027/TN2014-566 TemaNord

- Liu, Y. (2015). CDM and national policy: Synergy or conflict? Evidence from the wind power sector in China. Climate Policy, 15(6), 767–783. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2014.968764

- Macinante, J. (2015). Key elements of the net mitigation value assessment process. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23812/Networked0carb0e0assessment0process.pdf?sequence=1

- Marcu, A. (2015). Mitigation value, networked carbon markets and the Paris climate change agreement. Retrieved from http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/pubdocs/publicdoc/2015/9/840951442526241099/Mitigation-Value-Networked-Carbon-Markets-and-the-Paris-Climate-Change-Agreement.pdf

- Marcu, A. (2017). Governance of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and lessons learned from the Kyoto Protocol. Retrieved from https://www.cigionline.org/publications/governance-article-6-paris-agreement-and-lessons-learned-kyoto-protocol

- Mehling, M. A., Metcalf, G. E., & Stavins, R. N. (2018). Linking climate policies to advance global mitigation. Science, 359(6379), 997–998. doi: 10.1126/science.aar5988

- Meinshausen, M., & Alexander, R. (2017). NDC & INDC factsheets.

- Michaelowa, A. (1998). Joint implementation – the baseline issue: Economic and political aspects. Global Environmental Change, 8(1), 81–92. doi: 10.1016/S0959-3780(97)00022-8

- Michaelowa, A., & Butzengeiger, S. (2017). Ensuring additionality under Art. 6 of the Paris Agreement rethinking additionality. Retrieved from http://www.perspectives.cc/fileadmin/Reports/Art._6_Additionality_Perspectives_PRINT.pdf

- Michaelowa, A., Greiner, S., Hoch, S., LE Saché, F., Brescia, D., Galt, H., … Diagne, E.-H. M. (2016). The Paris Agreement: The future relevance of UNFCCC-backed carbon markets for Africa. ClimDev-Africa Policy Brief. Retrieved from http://www.climatefocus.com/publications/paris-agreement-future-relevance-unfcc-backed-carbon-markets-africa

- Michaelowa, A., & Purohit, P. (2007). Additionality determination of Indian CDM projects. Retrieved from http://climatestrategies.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/02/additionality-cdm-india-cs-version9-07.pdf

- Mizuno, Y. (2017). Proposal for guidance on robust accounting under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Retrieved from https://pub.iges.or.jp/proposal-guidance-robust-accounting

- Narassimhan, E., Gallagher, K. S., Koester, S., & Alejo, J. R. (2018). Carbon pricing in practice: A review of existing emissions trading systems. Climate Policy, 18(8), 967–991. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1467827

- Obergassel, W., & Asche, F. (2017). ). Shaping the Paris mechanisms Part III. An update on submissions on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Wuppertal. Retrieved from http://www.carbon-mechanisms.de/fileadmin/media/dokumente/Publikationen/Policy_Paper/PP_2017_05_Art_6_Submissions.pdf

- Prag, A., Aasrud, A., & Hood, C. (2011). Keeping track: Options to develop international greenhouse gas unit accounting after 2012. Paris.

- Prag, A., Hood, C., Aasrud, A., & Briner, G. (2011). Tracking and trading: Expanding on options for international greenhouse gas unit accounting. Paris.

- Prag, A., Hood, C., & Barata, P. M. (2013). Made to measure: Options for emissions accounting under the UNFCCC. Paris. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=COM/ENV/EPOC/IEA/SLT%282013%291&docLanguage=En

- Ranson, M., & Stavins, R. N. (2016). Linkage of greenhouse gas emissions trading systems: Learning from experience. Climate Policy, 16(3), doi: 10.1080/14693062.2014.997658

- Rich, D., Bhatia, P., Finnegan, J., Levin, K., & Mitra, A. (2014). Policy and action standard. Retrieved from http://www.wri.org/publication/policy-and-action-standard

- Rogelj, J., den Elzen, M., Fransen, T., Fekete, H., Winkler, H., Schaeffer, R., … Meinshausen, M. (2016). Perspective : Paris agreement climate proposals need boost to keep warming well below 2°C. Nature, 534(June), 631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature18307

- Schneider, L. (2009a). A clean development mechanism with global atmospheric benefits for a post-2012 climate regime, International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 9(2), 95–111.

- Schneider, L. (2009b). Assessing the additionality of CDM projects: Practical experiences and lessons learned. Climate Policy, 9(January 2013), 242–254. doi: 10.3763/cpol.2008.0533

- Schneider, L. (2011). Perverse incentives under the CDM: An evaluation of HFC-23 destruction projects. Climate Policy, 11(January 2013), 851–864. doi: 10.3763/cpol.2010.0096

- Schneider, L., Füssler, J., Kohli, A., Graichen, J., Healy, S., Cames, M., … Cook, V. (2017). Robust accounting of international transfers under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Berlin. Retrieved from https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/projektmechanismen/Robust_accounting_paris_agreement_discussion_paper_28092017.pdf?_blob=publicationFile&v=2

- Schneider, L., & Kollmuss, A. (2015). Perverse effects of carbon markets on HFC-23 and SF6 abatement projects in Russia. Nature Climate Change, 5(12), 1061–1063. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2772

- Schneider, L., Kollmuss, A., & Lazarus, M. (2015). Addressing the risk of double counting emission reductions under the UNFCCC. Climatic Change, 473–486. doi: 10.1007/s10584-015-1398-y

- Schneider, L., & La Hoz Theuer, S. (2017). Using the clean development mechanism for nationally determined contributions and international aviation. Stockholm. Retrieved from https://www.sei-international.org/mediamanager/documents/SEI-PR-2017-Using-the-Clean-Development-Mechanism.pdf

- Schneider, L., Lazarus, M., & Kollmuss, A. (2010). Industrial N2O projects under the CDM: Adipic acid – a case of carbon leakage, Somerville. https://www.sei.org/publications/industrial-n2o-projects-cdm-adipic-acid-case-carbon-leakage/

- Schneider, L., Lazarus, M., Lee, C., & van Asselt, H. (2017). Restricted linking of emissions trading systems: Options, benefits, and challenges. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(6), 883–898. doi: 10.1007/s10784-017-9370-0

- Shishlov, I., & Bellassen, V. (2016). Review of the experience with monitoring uncertainty requirements in the clean development mechanism. Climate Policy, 16(6), 703–731. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2015.1046414

- Sonter, L. J., Barrett, D. J., Moran, C. J., & Soares-Filho, B. S. (2015). Carbon emissions due to deforestation for the production of charcoal used in Brazil’s steel industry. Nature Climate Change, 5(4), 359–363. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2515

- Spalding-Fecher, R. (2013). National policies and the CDM rules: Options for the future. Swedish Energy Agency. Retrieved from https://www.energimyndigheten.se/contentassets/2600659ecfa54ec995b835a4c99d75fb/carbon-limits---national-policies-and-cdm.pdf

- Spalding-Fecher, R. (2017). Article 6.4 crediting outside of NDC commitments under the Paris Agreement: issues and options. Oslo. Retrieved from http://www.energimyndigheten.se/contentassets/2600659ecfa54ec995b835a4c99d75fb/spalding-fecher_crediting-outside-ndcs---final-report.pdf

- Spalding-Fecher, R., & Michaelowa, A. (2013). Should the use of standardized baselines in the CDM be mandatory? Climate Policy, 13(1), 80–88. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2012.726129

- Spalding-Fecher, R., Narayan Achanta, A., Erickson, P., Haites, E., Lazarus, M., Pahuja, N., … Tewari, R. (2012). Assessing the impact of the clean development mechanism. Report commissioned by the high-level panel on the CDM policy dialogue. Retrieved from http://www.cdmpolicydialogue.org/research/1030_impact.pdf

- Spalding-Fecher, R., Sammut, F., Broekhoff, D., & Fuessler, J. (2017). Environmental integrity and additionality in the new context of the Paris Agreement crediting mechanisms. Carbon Limits.

- Stavins, R., & Stowe, R. (2017). Market mechanisms and the Paris Agreement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Project on Climate Agreements.

- Strand, J. (2011). Carbon offsets with endogenous environmental policy. Energy Economics, 33(2), 371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2010.11.006

- Stua, M. (2013). Evidence of the clean development mechanism impact on the Chinese electric power system’s low-carbon transition. Energy Policy, 62(December 2005), 1309–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.07.039

- Trexler, M., Broekhoff, D., & Kosloff, L. (2006). A statistically-driven approach to offset-based GHG additionality determinations: What can we learn? Sustainable Development Law & Policy, VI(2), 30–40.

- Tuerk, A., Fazekas, D., Schreiber, H., Frieden, D., & Wolf, C. (2013). Green investment schemes: The AAU market between 2008 and 2012. Retrieved from http://climatestrategies.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/cs-gis-discussion-paper-formatted-final-rev2a.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2012). Various approaches, including opportunities for using markets, to enhance the cost-effectiveness of, and to promote, mitigation actions, bearing in mind different circumstances of developed and developing countries (Technical Paper (FCCC/TP/2012/4)). Retrieved from http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2012/tp/04.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2015). Adoption of the Paris Agreement: Decision 1/CP.21. (UNFCCC, Ed.).

- Vöhringer, F., Kuosmanen, T., & Dellink, R. (2006). How to attribute market leakage to CDM projects. Climate Policy, 5(5), 503–516. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2006.9685574

- Vrolijk, C., & Phillips, G. (2013). Net mitigation through the CDM. Retrieved from http://www.energimyndigheten.se/Global/Internationellt/Net mitigation through the CDM.pdf%5CnVrolijk, Phillips 2013 - Net Mitigation through the CDM.pdf

- Warnecke, C. (2014). Can CDM monitoring requirements be reduced while maintaining environmental integrity? Climate Policy, 14(4), 443–466. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2014.875285

- Warnecke, C., Day, T., Schneider, L., Cames, M., Healy, S., Harthan, R., … Höhne, N. (2017). Vulnerability of CDM projects for discontinuation of mitigation activities: Assessment of project vulnerability and options to support continued mitigation. Retrieved from https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/project-mechanisms/vulnerability-of-CDM.pdf?_blob=publicationFile&v=3

- Warnecke, C., Höhne, N., Tewari, R., Day, T., & Kachi, A. (2018). Opportunities and safeguards for ambition raising through Article 6. The perspective of countries transferring mitigation outcomes. Retrieved from https://newclimate.org/2018/05/09/opportunities-and-safeguards-for-ambition-raising-through-article-6/

- Warnecke, C., Wartmann, S., Höhne, N., & Blok, K. (2014). Beyond pure offsetting: Assessing options to generate net-mitigation-effects in carbon market mechanisms. Energy Policy, 68, doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2014.01.032

- Woerdman, E. (2005). Hot air trading under the Kyoto Protocol: An environmental problem or not? European Environmental Law Review, 14(3), 71–77. Retrieved from http://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/17591854/HotAirTrading_EELR.PDF

- Yamin, F., & Depledge, J. (2004). The international climate change regime. A guide to rules, institutions and procedures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.