ABSTRACT

This article explores changing water (in)securities in a context of urbanization and climate change in the peri-urban spaces of four South-Asian cities: Khulna (Bangladesh), Gurugram and Hyderabad (India), and Kathmandu (Nepal). As awareness of water challenges like intensifying use, deteriorating quality and climate change is growing, water security gets more scientific and policy attention. However, in peri-urban areas, the dynamic zones between the urban and the rural, it remains under-researched, despite the specific characteristics of these spaces: intensifying flows of goods, resources, people, and technologies; diversifying uses of, and growing pressures on land and water; and complex and often contradictory governance and jurisdictional institutions. This article analyses local experiences of water (in-)security, conflict and cooperation in relation to existing policies. It uses insights from the analysis of the case studies as a point of departure for a critical reflection on whether a ‘community resilience’ discourse contributes to better understanding these cases of water insecurity and conflict, and to better policy solutions. The authors argue that a community resilience focus risks neglecting important insights about how peri-urban water insecurity problems are experienced by peri-urban populations and produced or reproduced in specific socio-economic, political and policy contexts. Unless supported by in-depth hydro-social research, such a focus may depoliticize basically political questions of water (re) allocation, prioritization, and access for marginalized groups. Therefore, the authors plead for more critical awareness among researchers and policy-makers of the consequences of using a ‘community resilience’ discourse for making sense of peri-urban water (in-)security.

Key policy insights

There is an urgent need for more (critical) policy and scientific attention to peri-urban water insecurity, conflict, and climate change.

Although a changing climate will likely play a role, more attention is needed to how water insecurities and vulnerabilities in South Asia are socially produced.

Researchers and policy-makers should avoid using depoliticized (community) resilience approaches for basically socio-political problems.

1. Introduction

The world is rapidly urbanizing, with important socio-economic and environmental consequences. Urban growth creates spaces called ‘peri-urban’, defined by Leaf (Citation2011, p. 528) as ‘the coming together and intermixing of the urban and the rural, implying the potential for the emergence of wholly new forms of social, economic and environmental interaction that are no longer accommodated by these received categories’. As the rural-urban dichotomy has long dominated research and policy, the peri-urban has received relatively little attention. Yet its dynamic character and impact on peri-urban life require a better understanding – especially of the diversifying uses of, and growing pressures on, key resources like land and water in a context of complex governance and jurisdictional institutions (Narain & Prakash, Citation2016; Simon, Citation2008).

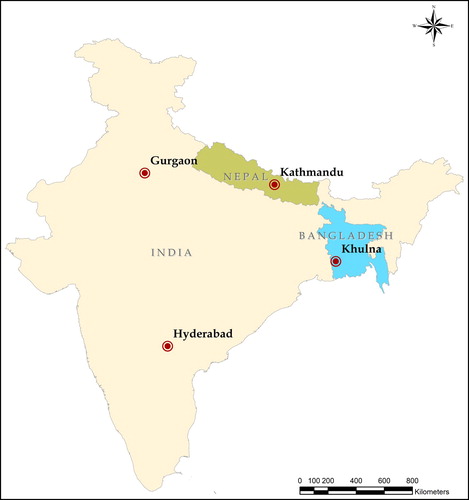

Water (in-)security and water-related conflicts are growing peri-urban problems. This article discusses water security in a context of urbanization and climate change in the peri-urban spaces of four South-Asian cities: Khulna in Bangladesh, GurugramFootnote1 and Hyderabad in India, and Kathmandu in Nepal. Peri-urban changes in land tenure, use and control, livelihoods and economic activities, groundwater and surface water uses, landscapes (increased infrastructure; soil hardening; disappearance of water bodies), and water quality deeply affect the water security of peri-urban populations. Changes in land tenure, in particular, are key drivers of peri-urban changes generally. For all three countries the huge impact of changing land tenure, transfers of land control and dispossession in urbanizing areas, by legal and illegal means, including class politics, collusion, corruption, threats and violence, is extensively reported (for Bangladesh: Adnan, Citation2013, Citation2016; Feldman & Geisler, Citation2012; For India: Levien, Citation2012; for Nepal: International Land Coalition, Citation2011; Upreti, Breu, & Ghale, Citation2017).

These processes are also deeply influencing peri-urban water rights and control, as well as water quantity and quality more specifically (see Narain & Prakash, Citation2016; Simon, Citation2008 for South Asia). Peri-urban water sources, for instance, often become major providers of groundwater and surface water for growing urban needs, and dumping sites for solid urban waste and polluted water. The changing climate is generally expected to add to peri-urban water insecurities. There is no doubt that climate change-induced changes in the water cycle, sea-level rise and salinity intrusion, changing monsoon patterns and greater frequency and intensity of extreme weather events (floods, droughts, storms, rainfall) are a reality in all research areas (Khan, Mondal, Sada, & Gummadilli, Citation2013; Narain & Prakash, Citation2016). But is there any strong evidence of climate change as a main ‘driver’ of changes in peri-urban water security and as a cause of water-related conflict?

Little is known about how peri-urban water insecurities are co-produced by urbanization, population growth, climate change, and socio-political and institutional processes at multiple scales (Lele, Srinivasan, Thomas, & Jamwal, Citation2018; Wilson, Citation2012). Earlier research suggests that economic and demographic processes have much more impact on water than climate change (Vörösmarty, Green, Salisbury, & Lammers, Citation2000). However, although changes in water security cannot be unequivocally attributed to climate change, in both science and policy, such ‘wicked’ problems are increasingly cast into a climate discourse, with climate-induced vulnerability as the problem and adaptation and (creation of) ‘(community) resilience’ as solutions (see MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2012). These framings have nowadays become a default point of departure for many research and development projects, as well as activist agendas and social movements (Béné, Citation2014; Cutter, Citation2016; MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2012; Taylor, Citation2014).

The CoCooN/CCMCC programme,Footnote2 of which the research for this article was part, is a case in point. CoCooN/CCMCC aimed at better understanding (1) the dynamics of resource-related cooperation and conflict in a context of climate change, its policies and management; (2) how to effectively build resilience of poor communities; and (3) the consequences for policies and programmes. Although the programme focused on a potentially interesting domain of science-policy interactions, its framing in terms of ‘adaptation’, ‘management’ of climate change, and ‘building community resilience’ points to a rather managerial and interventionist approach.Footnote3 Especially in funding contexts, these framings of problems, causalities and policy solutions are discursively and otherwise reproduced, and thus perpetuated rather that critically reviewed. Political ecologists like Taylor (Citation2014) rightly argue that such framings, and research and intervention practices based on them, are not self-evident but require serious scientific scrutiny.

This article, then, has a dual objective: as a first objective, it explores issues of water (in-)security and water-related conflict and cooperation in the peri-urban spaces of the cities mentioned above. The article is based on in-depth research on how changing water (in-)securities, water conflicts and forms of cooperation are locally experienced. Questions guiding the research were: (1) what changes in peri-urban water security are taking place and how are they experienced by various actors? (2) what is the role of water- and climate-related policies in relation to water insecurity problems? (3) what kinds of conflict and cooperation are developing around these experiences of changing water security? As a second objective, we use the insights from the case studies to briefly reflect on what we have learnt about the problematic relations of these insights with framings in terms of ‘community resilience’, which were central to the CoCooN/CCMCC research programme.

The article is structured as follows: in the next section, relevant concepts, approaches and research locations are introduced. Following this, short case studies on water security and conflicts in the context of the researched peri-urban spaces are presented. In the analysis, we draw further insights from these case studies, which form the basis of the key policy insights for this article. Next, the discussion critically reflects on the sense (or non-sense) of a ‘community resilience’ focus for a research programme like CoCooN/CCMCC. The discussion is followed by a short conclusion.

2. Concepts, approaches, and research locations

2.1. Concepts and approaches

In line with the ‘community’ focus of the CCMCC programme, this study presents an analysis of peri-urban water (in-)securities as experienced locally, by inhabitants of peri-urban communities. It also takes an ‘íntegrative’ approach to water security, recognizing its complexity and the importance of analysis in context (Zeitoun et al., Citation2016). This approach is more socially driven than ‘reductionist’ approaches, by taking into account, for instance, local notions of water rights and justice. Boelens and Seemann (Citation2014, p. 3), likewise, approach water security as an ‘intrinsically relational, political, and multi-scale relationship of access and control that takes shape in contexts of unequal power relations’, shifting the focus away from generalizing (naturalizing, technifying and depoliticizing) approaches while foregrounding political power and agency, inequality and marginalization, and water rights and justice (see Boelens, Perreault, & Vos, Citation2018; Joy, Kulkarni, Roth, & Zwarteveen, Citation2014).

Resource-related conflict and cooperation have long been approached from a resource-deterministic perspective (e.g. Homer-Dixon, Citation1999; see Bavinck, Pellegrini, & Mostert, Citation2014). Approaches were characterized by (1) bias to violent conflicts; (2) assumptions of linear causality between ‘scarcity’ (or ‘abundance’) and (violent) conflict; (3) labelling of conflict as ‘bad’, cooperation as ‘good’; (4) treatment of conflict and cooperation as mutually exclusive; (5) a one-dimensional perspective; and (6) assumptions of the ‘manageability’ of conflict. Stimulated by criticism from political ecologists (e.g. Peluso & Watts, Citation2001), more nuanced approaches have developed in relation to types of conflicts and causes; to valuation of conflict and cooperation (recognizing the potentially perverse character of cooperation and transformative potential of conflict, no longer treated as mutually exclusive); to the multiple layers and dimensions of conflicts; and to the ‘manageability’ of conflict (see Bavinck et al., Citation2014). In line with these insights, this article takes such a nuanced approach to conflict and cooperation. Conflict can be defined in many ways (Nursey-Bray, Citation2017, p. 164); we use a definition by Bavinck et al. (Citation2014, p. 4) of conflict as ‘confrontations between groups or categories of people’.

Although this is not the place to present an exhaustive discussion of the concept of resilience and the debates its popularity has generated, some remarks are due here, in view of the discussion at the end of this article. With the burgeoning attention that disasters and climate change are attracting, the concept (in relation to vulnerability and adaptation) has become increasingly popular in both the scientific and policy worlds (Béné et al., Citation2014; Boas & Rothe, Citation2016; Lele et al., Citation2018; MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2012). However, the mix of scientific claims, normative and ideological biases, policy recipes and interventionist agendas that the concept has come to represent is also increasingly criticized (see e.g. Béné et al., Citation2014; Cutter, Citation2016; Neocleous, Citation2013).

In response to earlier criticism of the concept’s engineering and systems ecological biases, characterized by a focus on restoration of system equilibrium and status quo (‘bouncing back’), ‘social resilience’ was defined as ‘the ability of groups or communities to cope with external stresses and disturbances as a result of social, political, and environmental change’ (Adger, 2000; in Brand & Jax, Citation2007, p. 23).Footnote4 However, this approach also has its critics. Taylor, for instance, criticizing framings in terms of vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience as the ‘holy trinity’ (Citation2014, p. 53) of climate change adaptation, pleads for more critical attention to how this produces ‘specific ways of thinking about and acting upon processes of social and ecological change’ (Citation2014, p. 10). We want to pinpoint three aspects of the debates about resilience that seem most relevant here: its multiple meanings, its depoliticizing impact, and its local community focus (‘community resilience’).

Firstly, the increasingly vague meanings of resilience are much criticized. Although its ‘boundary’ character – vague, flexible and open to multiple interpretations – attracts a variety of actors who embrace it (Béné et al., Citation2014; Boas & Rothe, Citation2016), its analytical power has decreased due to growing ambiguity and multiple meanings (Béné et al., Citation2014; Brand & Jax, Citation2007). This lack of conceptual clarity has made resilience ‘a concept that by attempting to mean everything ends up meaning nothing of analytical value’ (Boyden & Cooper, Citation2007, p. 12). According to Brand and Jax (Citation2007) it has become a metaphor for normatively defined flexibility. This is especially problematic in relation to the normative development agendas in which the concept has gained such prominence. It remains to be seen how resilience thinking as a ‘new paradigm for intervention and problem solving’ (Joseph, Citation2016) translates into and merges with such development and intervention practices. Who determines, for instance, what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’ resilience? Can translation into top-down, depoliticized and technocratic routines be avoided?

Secondly, while political to the core by its attempted ‘colonization of the political imagination’ (Neocleous, Citation2013, p. 7), the resilience discourse has some worrying depoliticizing effects. Swyngedouw (Citation2010) convincingly argues that the consensual politics of climate change, central to which are the notions of vulnerability, adaptation and resilience, are not only an expression, but also a formative force, of a depoliticized, ‘post-political’ climate managerialism, in which ‘post-politics refers to a politics in which ideological or dissensual contestation and struggles are replaced by techno-managerial planning, expert management and administration’ (Swyngedouw, Citation2010, p. 225). In a similar vein, Taylor (Citation2014) criticizes the focus on external disrupting forces that still dominates resilience thinking, blind to the ‘complex forms of socio-ecological production that operate across varied spatial scales, temporal horizons and social divides’ (Citation2014, p. 18). Many authors (e.g. Béné et al., Citation2014; Keck & Etzold, Citation2013; MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2012; Olsson, Jerneck, Thoren, Persson, & O’Byrne, Citation2015) have stressed that the resilience concept, with its background in ecological systems theory, is not the most suitable to deal analytically with the key issues of poverty, inequality, power, agency, and social transformation. In that sense, and notwithstanding re-definitions, it is a conservative concept (Cote & Nightingale, Citation2012). Especially in combination with technocratic and top-down forms of development, it will have a depoliticizing effect (Ojha et al., Citation2015).

Thirdly, the notion of ‘community resilience’ only adds to these problems, because of the problematic character of the community concept itself (Agrawal & Gibson, Citation1999; Béné et al., Citation2014; see however Wilson, Citation2012). Why are communities targeted as the ideal unit for ‘creating’ resilience? At least part of the answer lies in the managerialism of development and climate change policies that need a target unit for their interventions (Roth, Citation2016). However, ‘the community’ is not just objectively there waiting to be mobilized, it is a sociospatial construct defined as a collectivity, to be used for interventionist policy purposes. One of the specific dangers with the community focus, especially if ‘the community’ is framed as homogeneous, undifferentiated and consensual, is that existing inequalities (e.g. class, caste, gender, religion, ethnicity) and issues of societal transformation, agency, power, and knowledge tend to be neglected (MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2012; see also Béné et al., Citation2014; Keck & Etzold, Citation2013; Nagoda, Citation2015; Ojha, Citation2015; Wilson, Citation2012). Another point of criticism is the focus on the community as the unit that should ‘become resilient’. Aside from the fact that the normative definitions of resilience as the ultimate objective of development and/or adaptation tend to be externally defined (Cote & Nightingale, Citation2012; MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2012), many authors point out that this predilection for the local sits well with neoliberal forms of governance that shift to ‘the community’ the responsibility of becoming and remaining resilient through continuous adaptation (see e.g. Boas & Rothe, Citation2016; Cutter, Citation2016; Frerks, Warner, & Weijs, Citation2011; Joseph, Citation2016; Neocleous, Citation2013). It is questionable, moreover, whether ‘the community’ is the right place for dealing with major multiscalar challenges like globalization, capital accumulation and state policies that create and perpetuate local vulnerabilities. MacKinnon and Derickson (Citation2012, 263) rightly argue that ‘the promotion of [community] resilience … normalizes the uneven effects of neoliberal governance and invigorates the trope of individual responsibility with a renewed “community” twist’

2.2. Research locations and case studies

Building on earlier research on peri-urban water (in-)security (e.g. Khan et al., Citation2013; Narain & Prakash, Citation2016), this article adds a focus on conflict and cooperation. Although in differing contexts, the case study locations share major characteristics of peri-urban spaces: changing landscapes driven by land-use changes; a dynamic population; a mix of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ characteristics and life-styles; economic and livelihood diversification; pressure on natural resources; increasing socio-economic differentiation and inequality; and specific problems of administration, jurisdiction and governance (see Narain & Prakash, Citation2016; Simon, Citation2008). These processes also introduce or intensify important water quantity and quality problems, deeply influencing locally experienced water (in-)securities (Khan et al., Citation2013; Narain & Prakash, Citation2016).

All research locations experience climate variability and change. Khulna in coastal south-western Bangladesh, has a tropical monsoon climate. Just above sea-level, it is susceptible to tidal influences, sea-level rise, extreme river discharges, waterlogging and salinity. Climatic variables (temperature, sunshine, humidity, rainfall) have shown increases since 1980. Extreme events (cyclones, storm surges, floods) are also increasing, interacting with sea-level rise. Kathmandu Valley, located 1300 m above sea-level, has a more diverse, mainly subtropical cool and temperate climate. Temperature and number of hot days are increasing, with indications of an urban heat island effect in Kathmandu Valley, but no significant changes in total rainfall. Gurugram, located 32 km from New Delhi, has a low-humidity climate, hot summers and cold winters. Analysis shows a rising trend in maximum and minimum temperatures, shorter winters and longer summers. Frequency, intensity and seasonal distribution of rainfall are changing, while the monsoon period is weakening. Hyderabad, situated on the semi-arid Deccan plateau, has a tropical, hot and semi-arid climate. Temperatures are rising, with decreasing variability. Annual rainfall is slightly increasing, but with a growing inter-year variability (Khan et al., Citation2013).

To better understand existing vulnerabilities (including water insecurity), many authors stress the importance of in-depth research on how these are locally experienced and understood (Nagoda, Citation2015; Ojha et al., Citation2015; Wilson, Citation2012; Zeitoun et al., Citation2016). This has also been the point of departure for the research reported here, focusing on what changes in water security are taking place and how water users experience them. This formed the entry point for further research on water conflicts and cooperation. Case selection was based on scoping studies in all areas, using mixed methods. Although selected cases can never fully represent the many and multi-scalar water problems in these areas nor possible scalar linkages with climate change, they do represent frequently occurring issues: salinity and gate control in Khulna, changing water flows and increasing wastewater use in Gurugram, pollution and water scarcity in Hyderabad, and increasing groundwater exploitation in Kathmandu Valley ().

3. Water (in-)security, conflict and cooperation: four peri-urban cases from South Asia

This section briefly presents the main insights emerging from our peri-urban research through short case studies of typical peri-urban water problems in the four research sites. We do not claim that these are the biggest or most frequently occurring problems. However, together they illustrate the kinds of water security problems and conflicts experienced in these cases.

3.1. Khulna, Bangladesh: salinization, pollution and gate control conflicts

3.1.1. Khulna

Khulna (1.05 million people; 138 km2) is the third largest city in Bangladesh. Although the city’s population has declined by around 10.8% between 2001 and 2011, mainly due to closure of major industries, in-migrants are settling in peri-urban areas and urban pockets (Jones, Mahbub, & Haq, Citation2016; Saha, Citation2017). These are located predominantly in the tidal floodplains of the Rupsha and Bhairab rivers, with low relief and numerous water channels, tidal marshes and swamps. Urbanization causes conversion of lowlands, fallow lands and water bodies. While the latter are decreasing, built-up areas are increasing. The peri-urban areas show typical features like multiple institutional arrangements, rural and urban resource-based livelihoods, and hydrological and water pollution linkages. The Mayur River links urban and peri-urban areas, and provides important ecosystem services to residents. It drains into the Rupsha-Bhairab River near Alutala Village. Agriculture- and aquaculture-based communities of Alutala depend on the river for their livelihoods.

3.1.2. Policy context

National policies most relevant for Khulna, also considering climate change, are the National Water Policy (Ministry of Water Resources, Citation1999), the National Policy for Safe Water Supply and Sanitation (Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives, Citation1998), the Environmental Conservation Rules (Ministry of Environment and Forest, Citation1997) and the Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (Ministry of Environment and Forest, Citation2009). NPSWSS has different policies for urban and rural areas. Because of the different characteristics of peri-urban spaces, specific peri-urban policy attention is badly needed. Furthermore, BCCSAP apprehends that, with sea-level rise, salinity will move inland, reducing safe drinking water availability. Such challenges are not recognized in NPSWSS, so there is a need for coordination between these two policies.

Although peri-urban (fresh)water security is deeply influenced by urbanization, regional development and climate change, it is generally ignored in policies and planning. Because of the fluidity of peri-urban spaces, clear national policies for these spaces and their resources do not exist. Current national policies largely ignore even urban issues. A draft urban policy from 2014 is awaiting finalization and approval, but does not address peri-urban spaces. Consequently, peri-urban water governance has remained predominantly the purview of urban institutions, in cooperation or conflict with peri-urban formal and informal institutions and power brokers. In this process, new alliances and forms of cooperation among powerful actors create social exclusion and marginalization of less powerful groups.

3.1.3. Key water security issues

While water availability in adequate quantity and quality is important for peri-urban livelihoods, rapid urbanization and land-use changes (often driven by elite interests), climate change, and interventions in natural flows have limited it, especially for the poor who are most vulnerable to these changes. Development projects like a 70-km pipeline and a water treatment plant are being implemented to import fresh river water for urban water supply, but peri-urban water needs are not addressed. Conversion of lowlands and encroachment of water bodies for urban development continue to reduce peri-urban freshwater availability.

Urban water management infrastructure, particularly sluice gates for storm water drainage and flood management, ignores urban-peri-urban hydraulic connectivity and the adverse impact of urban water management on peri-urban water security. Urbanization by lowland conversion threatens the natural flow of the Mayur River. Untreated urban waste discharge and increased salinity intrusion make peri-urban water unsuitable for irrigation, aquaculture or domestic use. In response, farmers conserve water by placing temporary dams across canals or switching to less water-demanding winter crops. Due to this shortage of freshwater, peri-urban residents increasingly depend on groundwater for domestic needs. However, the number of tube-wells is insufficient to meet growing peri-urban demands.

3.1.4. Water conflict and cooperation

Competition for water between urban and peri-urban user groups has created conflicts. The sluice gate at Alutala, at the outfall of the Mayur River, was constructed in the 1980s to protect Khulna from tidal flood, storm surge and salinity intrusion. With increased wastewater generation, the gate became important for the city’s wastewater and stormwater discharge into the Rupsha River. Freshwater fishing in the Mayur River was the only livelihood option for many Alutala households. However, in the 1990s gate control was gradually taken over by powerful urban elites to allow and retain saline water for their shrimp farms into the canals and lowlands inside the gate. They also leased parts of the river and linked canals for the same purpose. This gate and river control in favour of saline-water fish farms adversely affected freshwater fisheries and jeopardized the livelihoods of fishing communities. Salinization of surface water also made it unsuitable for dry-season (irrigated) paddy farming.

The fishing communities organized to protest against commercial shrimp farming. However, the owners, backed up by urban elites, filed a lawsuit against this protest. Local NGOs and human rights organizations, supporting river rehabilitation and open-water fisheries, provided legal support. They also facilitated consultation with the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) and Department of Fisheries to mobilize assistance for fishing communities. Paddy farmers also joined the protests. Although the lawsuit ended in favour of open-water fisheries, the conflict between fishermen and local elites still exists and transforms into new alliances among the actors, such as unregistered freshwater fish farms. But the ‘gate control’ remains the central politicized issue. Devolution of gate operation responsibility from the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) to the Khulna City Corporation (KCC) in 2012 through negotiations and local advocacy has led to cooperation between KCC and peri-urban communities in resolving these conflicts. The National Water Policy recommends handing over small-scale structures to the Local Government Engineering Department (LGED). In peri-urban areas, however, city corporations are better positioned than LGED for conflict management, which indicates a need for policy adjustment.

3.2. Gurugram, India: private sector-driven expansion and changing water flows

3.2.1. Gurugram

Covering 231 km2, Gurugram has grown steadily from the 1980s to a population of 870,000 in 2001, and almost 2.5 million in 2017. It has become a major recreation, residential and outsourcing hub, on land acquired by the state and private actors. The haphazard development of commercial centres gave rise to gated colonies and residential enclaves. Urban elites massively buy land and build farmhouses for recreation in Gurugram’s fringe villages, while village commons (shrubs, forest, water bodies) and agricultural land are replaced by buildings or infrastructure like roads, canals and water treatment plants. Water (primarily groundwater) is ever more intensively exploited. For peri-urban people with mainly agriculture-based livelihoods, life is becoming increasingly difficult, with access insecurities in drinking, domestic and agricultural water.

3.2.2 Policy context

Since 1991, India’s economic policies have been dominated by principles of privatization and liberalization. The focus is urban-centric capitalist growth, often disregarding distributive principles, mainly around large metropolises (see e.g. Le Mons Walker, Citation2008). Peri-urban spaces are ideal for profit-maximizing enterprises and services like hotels, housing estates, hospitals and educational institutions. Land needed for these purposes is made available through conversion of agricultural land. Population growth, settlement, and economic growth create immense pressures on water, often resulting in inequitable access. In an interaction with emerging signs of climate change, these are causing critical peri-urban water governance challenges.

However, coordinated policy for peri-urban issues is almost absent. Many peri-urban areas are still governed by rural bodies and not municipal administration. The 74th Constitution Amendment Act (1992) recognizes ‘transitional areas’, granted status as ‘nagar (town) panchayats’. However, though the act empowers states to create this peri-urban unit, this has seldom been implemented, keeping the administrative rural-urban binary. The (rural) gram panchayats have no mandate, nor financial and staffing capacity to even provide basic water services. Hence in peri-urban areas of many Indian cities private institutions have emerged to commercially provide drinking water.

The Indian National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) shows increasing concern for climate change impacts, with attention to social justice, poverty, vulnerability, and inclusive sustainable development. However, this contradicts the actual trend towards state withdrawal from service provision and greater private sector involvement in, e.g. health, education and water provision, raising social justice and equity concerns. The National Water Mission (NWM) of 2011, under the NAPCC, calls for citizens’ and local bodies’ participation, both elected and unelected, in water management (Government of India, Citation2011, p. 11). This is consistent with the evolution visible in earlier water policies (1987, 2002), where state responsibilities were gradually transferred to local bodies. However, according to the National Water Framework Bill (Ministry of Water Resources, Citation2016), legally any water problem must be dealt with at the highest level of the judiciary.

Gurugram’s expansion results from this neoliberal policy. From the 1990s, the state has facilitated initiatives of mainly private developers, through, for example, special economic zones. Weak or overlapping governance institutions facilitate over-appropriation of resources by urban residents and the state to meet urban needs, while many peri-urban poor are struggling for survival. Land acquisition is power- and money-driven, with little scope for peri-urban communities to influence these processes (Narain & Prakash, Citation2016). Policies thus reflect a larger politics of urban planning. The state’s policy response to growing pressures on urban water is to augment supply by building treatment plants and canals to provide projects with peri-urban water. This has further affected access to land and water of peri-urban populations.

One mission of the NAPCC incorporates the National Water Mission. The NAPCC addresses climate change impacts through various natural resources departments. Consequently, Haryana’s climate change plan is addressed through its water policy. The Haryana State action plan (Government of Haryana, Citation2011) prioritizes judicious water allocation, increased efficiency, conservation and optimum water use, effective groundwater management, technological upgrading and anticipation of climate change impacts, and integrated planning. However, this sectoral approach, focusing on conventional categories of urban and rural development, hardly reflects local realities. This planning style also influences climate adaptation approaches, which are not equipped to address specific peri-urban vulnerabilities.

3.2.3. Key water security issues

These changes deeply affect water quantity (shortage; waterlogging) and quality. Major manifestations are growing surface water scarcity, due to the disturbance of water bodies and sources. This increases pressures on groundwater, causing the groundwater table to decline. While well-to-do water users continue extracting groundwater using expensive pumping technologies, the poor lose out. Surface and groundwater pollution, waterlogging, and salinity worsen the situation. In irrigation there is a growing farmer dependence on wastewater conveyed from the city through canals. Thus, changing rural-urban water flows, in combination with emerging effects of climate variability and change (see Khan et al., Citation2013; Narain & Prakash, Citation2016), create increasingly insecure access to water for some, while guaranteeing safe and secure access for others. Depending on context, this can either lead to conflicts or stimulate collective action.

3.2.4. Water conflict and cooperation

New forms of cooperation are developing around wastewater canals. Their development, exploitation and management entail new arrangements for allocation and distribution, and patterns of in- and exclusion. Farmers’ investments of capital, labour or materials in infrastructure (canals, furrows, ponds, division works) create water rights. In one village, farmers collectively built a furrow to carry wastewater to a storage pond, from where it is pumped to farmers’ fields. This was a collective response to uncertain wastewater availability when canal supply falls short. Although conflicts are rare around these canals, sometimes they do erupt, for example, when a farmer using wastewater forgets to close the outlet and this wastewater damages a neighbour’s crop, or when too little water is released from the headworks. Reactions by affected farmers, such as pressure put on the gate operator to release more water, may result in verbal or even physical confrontation. Farmers’ daily access to wastewater is also mediated by norms of cooperation for wastewater use. Below the outlet, wastewater is distributed on the basis of norms of mutual cooperation – locally referred to as ‘brotherhood’ – that have a strong local social legitimacy. This allows wastewater to be shared with farmers beyond those with sanctioned pipe outlets.

3.3. Hyderabad, India: industrial expansion, pollution and water insecurity of marginalized groups

3.3.1. Peri-urban Hyderabad

Hyderabad has a population of 8 million, growing 5% yearly. Farah Nagar is a cluster of Malkaram Village in peri-urban Hyderabad, with poor living conditions and water insecurity due to haphazard economic expansion without adequate infrastructural measures and transfer of financial-administrative powers. The cluster is home to a huge landfill site of the Hyderabad Municipal Corporation and an educational institution, the Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS). It has 125 households belonging to a very poor Muslim community, many of them labourers or drivers in the landfill site. Farah Nagar lacks basic infrastructure like roads, lighting and sewer lines. Its only water source is groundwater, accessed through a borewell on the mosque premises. The groundwater is heavily contaminated by wastewater discharge from BITS and the (leaking) landfill. As public water supply is absent, residents use this water to meet domestic needs.

3.3.2. Policy context

The Indian national policy context has been described above. Important for this case is the fact that the 74th Constitution Amendment Act’s recognition of ‘transitional areas’ has rarely been implemented. In view of the gram panchayats’ lack of mandates and governance capacities (see above), many private institutions have emerged in peri-urban Hyderabad to commercially provide drinking water.

3.3.3. Key water security issues

Domestic water in Farah Nagar comes from the borewell and drinking water from alternative sources like private reverse osmosis (RO) filter plants. In summer, especially in drought years, people face extreme water scarcities when the borewell runs dry. While elsewhere purchasing tanker water is common to meet domestic needs in such situations, in Farah Nagar only few households can afford this. During normal seasons RO-treated water is priced around USD 0.06 to USD 0.13 per 20 litres, which almost doubles during Summer. Hence many poor households switch to consuming polluted groundwater during lean seasons. If households use purchased water under extreme scarcity, they prioritize drinking and food preparation.

Extreme water scarcities in 2015, a drought year, made residents look for alternative sources: fetching water from a neighbourhood cluster that receives treated water throughout the year, purchasing tanker water, and purchasing or borrowing from borewell-owning neighbours. Only few people purchase tanker water, as the price almost doubles during summers. Most households depend on water from neighbouring clusters. It is freely available, but used by people from outside at times causes conflicts. Women report extreme hardships in fetching water, as they can carry only one pot at a time, which results in making several long trips. Pollution of water sources exacerbates water scarcities, while the wastewater flow from BITS has degraded living conditions.

3.3.4. Water conflict and cooperation

While Farah Nagar is extremely water insecure, it has not shown any conflicts, nor promising collective action, nor negotiations with agencies to change the situation. Two other clusters of the same village are better-off for water access, having successfully negotiated supply of treated water with the responsible agency. The poor lower-class status of the inhabitants in combination with their status as a (Islamic) religious minority in Farah Nagar explains their lack of social and political bargaining power with the government or other relevant actors. Insights from fieldwork also reveal internal conflicts and mistrust among individuals and groups in the cluster, preventing them from acting collectively or formulating effective negotiation strategies vis-à-vis government and private agencies. Instead, some inhabitants come to depend on better-off individuals regarded as more effective in solving their problems, which strengthens dependencies and patron-client like relationships.

3.4. Kathmandu, Nepal: increasing groundwater use, management and conflict

3.4.1. Kathmandu valley and Jhaukhel

Kathmandu Valley has a population of around 2.5 million, growing by 6% yearly. Urbanization accelerated from the 1970s, with urban coverage increasing from 20.19 (1976) to 139.57 km2 (2015). Deficiencies in basic services, including water, are increasing. The valley has faced water scarcity for over two decades. Rapid urbanization driven by, among others, in-migration, a real estate sector boom driven by remittances, weak land governance and corruption, has degraded surface and groundwater quantity and quality, causing major water security challenges. In 1997, the Government of Nepal initiated the Melamchi Water Supply Project (MWSP) for inter-basin water transfer, which faced serious delays. Increasing demand-supply gaps and inadequate public supply led to the expansion of private water supply using tankers and bottled water. Over 90% of these tankers use peri-urban groundwater. Urbanization-induced challenges to water security will probably be exacerbated by climate change.

Jhaukhel belongs to Bhaktapur District. Lacking surface sources, Jhaukhel has always been groundwater-dependent. The emergence of groundwater extraction from household and communal wells, financed from local development funds, made life easier compared to earlier dependence on traditional water sources. However, it also stimulated commercial water extraction from 2000 onwards, causing groundwater level decline and drying up of sources. Apart from many unregistered private suppliers, there are about ten registered drinking water suppliers, most registered as water-bottling factories but also supplying tanker water. Brick kilns extract groundwater as well. Over-extraction has caused a rapid groundwater decline, also negatively affecting traditional sources (spouts, wells, springs) and creating a need for ever deeper wells.

3.4.2. Policy context

The 1992 Water Resources Act (WRA) vests ownership of water in the government. To improve water management, the Kathmandu Valley Water Supply Management Board (KVWSMB), responsible for water supply and sanitation, was established in 2006. Although KVWSMB is authorized to regulate groundwater use in the valley, its services are largely limited to urban centres. KVWSMB formulated the Groundwater Management Policy (Citation2012) for sustainable use and management. It reserves shallow groundwater for domestic use, and the deep aquifer for all uses, including commercial extraction, but with a license from KVWSMB. The policy requires commercial extractors to obtain a license from KVWSMB, which has prepared guidelines for licensing and volumetric restrictions on commercial extraction from the deep aquifer. However, water vendors continue extracting shallow groundwater for commercial uses, claiming that earlier registration of water factories at the Department of Cottage and Small Industries (DSCI), prior to KVWSMB, is a permit for commercial groundwater extraction. Hence, notwithstanding restrictive policy, commercial extraction continues. Extraction without any formal registration continues as well.

Groundwater crucially contributes to achieving the national target of ‘universal access to safe drinking water and sanitation for all’.Footnote5 In addition, it is considered less vulnerable to climate fluctuations than surface sources. This makes groundwater crucial in climate change adaptation strategies. Nepal formulated its national Climate Change Policy in 2011. Its main focus is community-based local adaptation, as mentioned in the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA), which was developed in 2010. The NAPA identifies national priorities and also recognizes the importance of groundwater in adaptation, prioritizing its sustainable management, especially in urban areas.

3.4.3. Key water security issues

Population growth and urbanization in Kathmandu Valley have quickly changed the formerly rural landscape. Land use changes, resource extraction, and building are increasingly disturbing quality and quantity of surface sources. Inadequate urban and peri-urban water supply have led to increasing non-commercial and commercial (over-)extraction of groundwater from shallow and deep aquifers. In Jhaukhel, more specifically, the impact of diversifying and expanding economic activities (water vending, sand-mining, brick production) on groundwater is the greatest water challenge. Around 30% of the houses in Jhaukhel have government-supported piped drinking water. Its users are mainly higher-caste people who can pay, making them independent from traditional sources. Over the years, many traditional sources have declined or dried up. Alternatives for daily needs are communal and private wells. However, with a declining water level, water provision from these sources is not without frictions, especially in the dry season. While many people buy water, the provision of free water by vendors and brick factories to their neighbours prevents open conflicts with local users, but also makes it possible for vendors to legitimize and continue their commercial extraction practices.

3.4.4. Water conflict and cooperation

In the mid-1990s, environmental concerns led to a campaign against brick factories. Air pollution was a major concern, but groundwater was not yet so. When the district government showed indifference, in 1997 villagers formed the Jhaukhel Environment Committee. It submitted petitions to ministries and environmental organizations, and filed a lawsuit against unregistered factories. In 2002, it organized an awareness campaign against leasing out land to brick factories. On the campaign day, the brick kiln owners intervened and the campaign turned violent. After this experience, inhabitants became afraid and refrained from further protesting against the brick kilns.

Following several petitions against groundwater extraction, the village government issued a public notice declaring water tanker operations illegal. As implementation was poor, in 2012 protesters against water vending blocked the main road. Although operations were temporarily halted, no major action was taken to control extraction; new water vendors have even emerged. Inhabitants stress the nexus between commercial extractors and government authorities, as extractors generate revenue for the district government. Political representatives do not take local concerns to the district government because of their hidden interests, including the involvement of relatives in resource extraction. Moreover, many local people support the norm that land control includes rights to groundwater extraction, and think commercial users with a permit have the right to extract water. Many people plead for better regulation rather than total closure. This nexus - loyalty towards relatives, government indifference, fear of violence, and local notions of rights – explains the absence of open conflicts, despite growing water insecurities.

4. Analysis and discussion

What do these case studies illustrate about local experiences of changing water security, the role of policies, and conflict and cooperation? Although in a context of increasing pressures on water caused by multiple changes (hydrological, demographic, social, economic, climate etc.), the key peri-urban water security issues described above mainly illustrate the crucial ways in which these changes are related to wider issues of poverty, inequality, power relations, and political conditions and policy choices that support specific socio-economic priorities, strategies, activities, and interest groups, often threatening the water security of poor groups.

Khulna most clearly illustrates the complex interactions between urbanization, climate change and water security. A key water security issue is growing salinity, partly attributable to climate change but to a large extent also reflecting competing resource interests. While a shrimp-cultivating elite tries to control hydraulic structures and canals to retain or increase salinity, other groups defend their freshwater interests for domestic uses, fishing and agriculture. In Gurugram, the building and investment boom continues, driven by the privatization of common land and in the absence of policies to protect resource-dependent peri-urban populations. This causes growing water insecurity as a consequence of increasing pressures on surface and groundwater. In the case of peri-urban Hyderabad, the same happens in a more extreme form: an excessively poor, powerless and marginalized group fully dependent on scarce, polluted and expensive water sources. The joint impacts of class and religion make for extreme marginalization, water insecurity and neglect. Finally, the Kathmandu case shows how commercial groundwater extraction interests have come to prevail over water security for domestic and drinking uses. In a context of lack of public water provision and weak regulatory arrangements, this means that people are made increasingly dependent on commercial sources.

In Khulna, major conflicts exist around hydraulic structures that regulate freshwater availability, saline-water intrusion and wastewater discharge. Forms of cooperation and alliances play an important role for all parties: either to strengthen their case and mobilize support against salinity intrusion and wastewater discharge, or to perpetuate their control of land, saline or fresh water, and hydraulic structures through connections with bureaucrats, administrators and other powerful actors. Gurugram illustrates how peri-urban farmers adapt their agricultural practices to changing water security conditions by using wastewater and organizing around its infrastructure. This establishes new forms of collective action and cooperation in water allocation. While wastewater use brings new potential sources of conflict, there is also a basis of local norms of cooperation with a strong local legitimacy that reduces the conflict potential and expands water access. Hyderabad, on the contrary, illustrates a water insecurity situation where an extremely poor group, marginalized along lines of class and religion, is internally too divided to engage in collective action and too powerless to negotiate improved water security with more powerful external actors. The Kathmandu case shows that local groups were engaging in a collective protest against pollution and, later, groundwater extraction, but are also hesitant after experiencing how protests resulted in violence. Complicating factors are the various perverse forms of cooperation based on shared vested interests, social networks and ties of loyalty and dependence, as well as local norms that legitimize groundwater extraction.

The policy contexts of all cases point to the problems caused by the dichotomous nature of urban and rural governance, planning and development, in which their basically interlinked character is either totally ignored or, if acknowledged, leads to policies reproducing the worst of both worlds. Urban-rural dichotomies and sectoral divisions hamper more integrated policy approaches and reproduce business-as-usual policies. In Khulna, peri-urban water governance issues are dealt with by urban institutions, often in problematic interaction with peri-urban ones and in a context of powerful elite interests influencing policy institutions. Coordination between related issues (e.g. water and climate) is lacking in policies that separates them into different domains. In Gurugram, relevant policies (land, water, climate) seem to be subservient to a policy agenda of neoliberal economic growth. Although there are linkages between climate and water policies, these policies are sectoral and based on the rural-urban dichotomy. The same goes for the Hyderabad case, in which rural administrative units do not have a mandate nor the governance capacities to provide basic water services, while the water insecurities of poor and marginalized groups are subordinated to the overall priority of capitalist economic growth. In peri-urban Kathmandu, policies exist to restrict commercial groundwater exploitation and stimulate sustainable use in line with national climate change policies. However, as restrictions are not systematically enforced, over-exploitation of groundwater continues.

The analysis of hydro-social changes in the four cases illustrates the importance of an ‘integrative’ approach to water security (Boelens & Seemann, Citation2014; Zeitoun et al., Citation2016). The examples of conflict and cooperation give further support to approaches that avoid the simplifications that have long dominated many resource conflict studies, especially the normative assumptions about conflict and cooperation framed in terms of a good/bad dichotomy of mutually exclusive modes (see Bavinck et al., Citation2014). Many types of conflict are brewing in peri-urban areas, but not all violent and never directly causally related to an assumedly climate-induced ‘scarcity’. The often invisible forms of cooperation through networks of interest and power tend to remain under the radar of normative and managerial approaches to conflict and cooperation. However, they prove crucial in establishing and perpetuating both access and exclusion, allocating burdens and benefits, and increasing equality or inequality. The same can be said about the role of local notions of water rights and equitable access to water. Rather than as a consequence of ‘scarcity’, water-related conflicts often occur in those places where water re-allocations, redistributions or uses are contested because their effects negatively affect specific (groups of) water users.

Finally, most peri-urban water security issues and conflicts described above point to severe problems, primarily with how water is governed under conditions of socio-environmental change, how the burdens and benefits of these changes are allocated, and the extent to which those holding political power and policy institutions are able (and willing) to deal with these issues in a way that takes into account the specific characteristics of peri-urban spaces, populations and livelihoods under pressure. Even where the effects of a changing climate are most visible – in the tidal floodplains of Bangladesh – the conflicts are primarily socio-political, about exertion of power and control over people, resources, and water infrastructure by networks of political and entrepreneurial elites.

How does this relate to the focus of the CoCooN / CCMCC programme on ‘community resilience’ – especially with regard to its multiple meanings, depoliticizing effects and community discourse? As for the first: the CCMCC programme actually illustrates the role of the resilience concept as ‘empty signifier’ in a research programme at the research-policy interface. The concept is important for the donor organization, the funded research organization incorporates it in the research questions of the programme call, and the applicants can (of course) relate to it in their proposals. However, (community) resilience was not defined, theorized, debated, problematized, and actually hardly used in the various projects. Notably, the more intervention-oriented development part of the programme (see note 2) aimed at creating tools and intervention strategies for building community resilience! Undefined and hardly used, ‘resilience’ remained a feel-good concept without any further analytical or practical value for the programme.

As for the depoliticizing effects of the resilience concept, the evidence from the peri-urban water security cases discussed above shows the importance of keeping critical distance from the ‘post-political’ (Swyngedouw, Citation2010) consensual and managerial resilience discourse that has emerged as a core element in many development and climate adaptation policies and interventions. The cases clearly illustrate the importance of precisely those elements, attention to which is found lacking in many resilience approaches: issues of poverty and inequality, exclusion and marginalization, and agency and power. The water insecurities and conflicts discussed above are primarily created in and through socio-political and policy processes in which inequalities are reproduced, elite interests prioritized, and socially transformative policies and interventions blocked by networks of cooperation and decision-making that maintain the socio-political status quo.

As for the community focus of resilience interventions, the case studies show that, especially in the socially and otherwise highly diverse and dynamic peri-urban spaces discussed above, it is often far from clear what constitutes a community and how it could be targeted for community resilience interventions in ways that solve the water insecurities experienced by poor and marginalized water users. The highly differentiated character of ‘communities’ and the increasing internal differences in water access and water security of peri-urban populations make a community resilience approach an unlikely solution. Moreover, most water-related vulnerabilities and insecurities experienced by peri-urban water users are produced by multi-scalar structures, processes and relationships that tend to be too big to be solved by community-oriented ‘creation of resilience’ approaches.

5. Conclusion

In this article, four typical cases of changing peri-urban water security (Khulna in Bangladesh, Gurugram and Hyderabad in India, and Kathmandu in Nepal) were presented and analysed. For each site, relevant water, climate and other policies, changes in peri-urban water security as locally experienced by peri-urban citizens, and examples of water-related conflict and cooperation developing around the site-specific water security issues were described. Although insights from this study need to be treated with modesty about their wider implications, three major conclusions can be drawn here that relate to the policy insights formulated for this article.

First, there are problematic frictions between these dynamic peri-urban spaces, and static policies dichotomized along the urban-rural divide, compartmentalized in responsible government agencies, and framed in a one-size-fits-all way. While ‘more policy’ is not necessarily a solution and ‘more of the same’ would even worsen the situation, a major challenge for peri-urban water security in relation to climate change is how to influence policy processes and networks in a broader sense. Policy is more than just the government instruments of spatial, land, water and climate governance. Policies are made and remade, partly embraced and rejected, circumvented, debated and contested by multiple actors (Shore, Wright, & Però, Citation2011). Policy processes in this broader sense – policies as made and transformed by multiple governmental, non-governmental, citizen, scientific and other actors – are needed to critically appreciate, confront, re-make and especially re-focus existing governmental policies towards the peri-urban and its urgent water insecurity problems.

Second, such policy attention should avoid decontextualized and universalistic approaches that cannot deal with the multidimensional character of peri-urban water insecurity. Policies (including donor-funded policies) should build on awareness that peri-urban water insecurities are, primarily, socially (and politically) produced through development and urbanization strategies, policy choices and priorities, power relations and decision-making processes dominated by elite interests. While climate variability and change clearly influence peri-urban water insecurity, the latter cannot be causally attributed to the changing climate only. This social production of water insecurity tends to be neglected, especially where framings of such complex problems through climate change discourses, funding structures and received wisdom about policy solutions are increasingly influential. Climate change-framed policies (e.g. Nepal’s climate change adaptation policies: Nagoda, Citation2015; see Ojha et al., Citation2015) are often universalistic, decontextualized, technocratic and depoliticized, thus completely missing out on essentials like locally experienced water insecurities and related vulnerabilities, and how these are produced in specific social-environmental and political contexts, differentially benefiting or burdening specific groups (see Swyngedouw, Citation2010).

Third, avoiding such biases and simplifications requires more critical attention to the ways in, and degree to, which funding structures, discursive framings of problems and solutions, and policies based on them shape research agendas and interventions through programmes and projects. This is why funders, researchers and policy actors need to be much more critical of reductionist framings of problems and solutions for complex problems (such as water security) in terms of generalizing and decontextualized vulnerability, adaptation and (community) resilience approaches. Rather than a ‘technocratic politics of intervention’ (Taylor, Citation2014, p. 62; see Ribot, Citation2011) based on such framings, the peri-urban water security problems discussed here require attention to precisely those issues that are often found missing: local experiences and perceptions of water insecurity and other vulnerabilities, understood in a context of power relations, social and political agency, inequality, and poverty.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Until 2017 Gurugram was named Gurgaon.

2 CCMCC (Conflict and Cooperation in the Management of Climate Change; 2014–2018) was part of the research programme CoCooN (Conflict and Cooperation over Natural Resources in Developing Countries). In CCMCC, seven projects, combining agendas of Research, Development, and Capacity Development, were funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Department for International Development (DFID) in the United Kingdom. The programme aimed at strengthening the evidence on the impact of climate change (and climate change policies, finance) on issues of conflict and cooperation in developing countries. For the programme, see https://www.nwo.nl/en/research-and-results/programmes/conflict±and±cooperation±in±the±management±of±climate±change±%28ccmcc%29. For the CCMCC project reported on here – Climate Policy, Conflicts and Cooperation in Peri-urban South Asia: Towards Resilient and Water Secure Communities – see https://www.nwo.nl/en/research-and-results/programmes/Conflict±and±Cooperation±over±Natural±Resources±in±Developing±Countries±%28CoCooN%29/Project±Dr±Roth.

3 Community resilience can be defined in many ways, depending on how ‘community’ and ‘resilience’ are approached. Berkes and Ross (Citation2013), for instance, note an often-used understanding of community resilience as ‘the capacity of its social system to come together to work toward a communal objective’.

4 For more definitions, see MacKinnon & Derickson (Citation2012).

References

- Adnan, S. (2013). Land grabs and primitive accumulation in deltaic Bangladesh: Interactions between neoliberal globalization, state interventions, power relations and peasant resistance. Journal of Peasant Studies, 40, 87–128. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.753058

- Adnan, S. (2016). Alienation in neoliberal India and Bangladesh: Diversity of mechanisms and theoretical implications. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13, 1–20.

- Agrawal, A., & Gibson, C. C. (1999). Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development, 27(4), 629–249. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00161-2

- Bavinck, M., Pellegrini, L., & Mostert, E. (Eds.). (2014). Conflicts over natural resources in the global south: Conceptual approaches. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Béné, C., Newsham, A., Davies, M., Ulrichs, M., & Godfrey-Wood, R. (2014). Review article: Resilience, poverty and development. Journal of International Development, 26(5), 598–623. doi: 10.1002/jid.2992

- Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society and Natural Resources, 26, 5–20. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2012.736605

- Boas, I., & Rothe, D. (2016). From conflict to resilience? Explaining recent changes in climate security discourse and practice. Environmental Politics, 25(4), 613–632. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2016.1160479

- Boelens, R., Perreault, T., & Vos, J. (2018). Water justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boelens, R., & Seemann, M. (2014). Forced engagements: Water security and local rights formalization in Yanque, Colca Valley, Peru. Human Organization, 73(1), 1–12. doi: 10.17730/humo.73.1.d44776822845k515

- Boyden, J., & Cooper, E. (2007). Questioning the power of resilience: Are children up to the task of disrupting the transmission of poverty? Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC) working paper 73. University of Oxford.

- Brand, F. S., & Jax, K. (2007). Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and boundary object. Ecology and Society, 12(1), 23. doi: 10.5751/ES-02029-120123

- Cote, M., & Nightingale, A. J. (2012). Resilience thinking meets social theory. Progress in Human Geography, 36(4), 475–489. doi: 10.1177/0309132511425708

- Cutter, S. L. (2016). Resilience to what? Resilience for whom? The Geographical Journal, 182(2), 110–113. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12174

- Feldman, S., & Geisler, C. (2012). Land expropriation and displacement in Bangladesh. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(3–4), 971–993. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.661719

- Frerks, G., Warner, J., & Weijs, B. (2011). The politics of vulnerability and resilience. Ambiente & Sociedade, XIV(2), 105–122. doi: 10.1590/S1414-753X2011000200008

- Government of Haryana. (2011). Haryana State action plan on climate change. Retrieved from http://www.moef.nic.in/sites/default/files/sapcc/Haryana.pdf

- Government of India. (2011). National water mission (Draft) under national action plan on climate change. Ministry of water resources, New Delhi.

- Homer-Dixon, T. (1999). Environment, scarcity and violence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- International Land Coalition. (2011). The land development boom in Kathmandu valley. Rome: Author.

- Jones, G., Mahbub, A. Q. M., & Haq, M. I. (2016). Urbanization and migration in Bangladesh. Dhaka: United Nations Population Fund, Bangladesh Country Office.

- Joseph, J. (2016). Governing through failure and denial: The new resilience agenda. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 44(3), 370–390. doi: 10.1177/0305829816638166

- Joy, K. J., Kulkarni, S., Roth, D., & Zwarteveen, M. (2014). Re-politicising water governance: Exploring water re-allocations in terms of justice. Local Environment, 19(9), 954–973. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.870542

- Keck, M., & Etzold, B. (2013). Resilience refused. Wasted potentials for improving food security in Dhaka. Erdkunde, 67(1), 75–91. doi: 10.3112/erdkunde.2013.01.07

- Khan, M. S. A., Mondal, M. S., Sada, R., & Gummadilli, S. (2013). Climatic trends and variability in south Asia: A case of four peri-urban locations. Hyderabad: SaciWATERs and IDRC.

- KVWSMB. (2012). Groundwater management policy 2012. Kathmandu Valley Water Supply Management Board, Lalitpur, Nepal.

- Leaf, M. (2011). Periurban Asia: A commentary on “becoming urban”. Pacific Affairs, 84(3), 525–534. doi: 10.5509/2011843525

- Lele, S., Srinivasan, V., Thomas, B. K., & Jamwal, P. (2018). Adapting to climate change in rapidly urbanizing river basins: Insights from a multiple-concerns, multiple-stressors, and multi-level approach. Water International, 43 (2), 281–304. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2017.1416442

- Le Mons Walker, K. (2008). Neoliberalism on the ground in rural India: Predatory growth, agrarian crisis, internal colonization, and the intensification of class struggle. Journal of Peasant Studies, 35(4), 557–620. doi: 10.1080/03066150802681963

- Levien, M. (2012). The land question: Special economic zones and the political economy of dispossession in India. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(3–4), 933–969. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.656268

- MacKinnon, D., & Derickson, K. D. (2012). From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 253–270. doi: 10.1177/0309132512454775

- Ministry of Environment and Forest. (1997). Environmental conservation rules. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Environment and Forest. (2009). Bangladesh climate change strategy and action plan (BCCSAP). Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives. (1998). National policy for safe water supply & sanitation (NPSWSS). Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Water Resources. (1999). National water policy (NWPo). Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India. (2016). National water framework bill (NWFB) (draft). Ministry of water resources, New Delhi. pp. 1–29.

- Nagoda, S. (2015). New discourses but same old development approaches? Climate change adaptation policies, chronic food insecurity and development interventions in northwestern Nepal. Global Environmental Change, 35, 570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.014

- Narain, V., & Prakash, A. (Eds.). (2016). Water security in peri-urban South Asia. Adapting to climate change and urbanization. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Neocleous, M. (2013). Commentary. Resisting resilience. Radical Philosophy, 178, 2–7.

- Nursey-Bray, M. (2017). Towards socially just adaptive climate governance: The transformative potential of conflict. Local Environment, 22(2), 156–171. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2016.1181618

- Ojha, H. R., Ghimire, S., Pain, A., Nightingale, A., Khatri, D. B., & Dhungana, H. (2015). Policy without politics: Technocratic control of climate change adaptation policy making in Nepal. Climate Policy, 16(4), 415–433. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2014.1003775

- Olsson, L., Jerneck, A., Thoren, H., Persson, J., & O’Byrne, J. (2015). Why resilience is unappealing to social science: Theoretical and empirical investigations of the scientific use of resilience. Science Advances, 1(4), 1–11. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1400217

- Peluso, N. L., & Watts, M. (Eds.). (2001). Violent environments. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Ribot, J. (2011). Vulnerability before adaptation: Toward transformative climate action. Global Environmental Change, 21(4), 1160–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.07.008

- Roth, D. (2016). Understanding and governing the peri-urban: Some critical reflections. South Asian Water Studies, 5(3), 1–6.

- Saha, S. K. (2017). Cyclone Aila, livelihood stress, and migration: Empirical evidence from coastal Bangladesh. Disasters, 41(3), 505–526. doi: 10.1111/disa.12214

- Shore, C., Wright, S., & Però, D. (Eds.). (2011). Policy worlds. Anthropology and the analysis of contemporary power. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

- Simon, D. (2008). Urban environments: Issues on the peri-urban fringe. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 33, 167–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.environ.33.021407.093240

- Swyngedouw, E. (2010). Apocalypse forever? Post-political populism and the spectre of climate change. Theory, Culture & Society, 27, 213–232. doi: 10.1177/0263276409358728

- Taylor, M. (2014). The political ecology of climate change adaptation: Livelihoods, agrarian change and the conflicts of development. London: Routledge/Earthscan.

- Upreti, B. R., Breu, T., & Ghale, Y. (2017). New challenges in land use in Nepal: Reflections on the booming real-estate sector in Chitwan and Kathmandu Valley. Scottish Geographical Journal, 133(1), 69–82. doi: 10.1080/14702541.2017.1279680

- Vörösmarty, C. J., Green, P., Salisbury, J., & Lammers, R. B. (2000). Global water resources: Vulnerability from climate change and population growth. Science, 289(5477), 284–288. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.284

- Wilson, G. A. (2012). Community resilience, globalization, and transitional pathways of decision-making. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 43(6), 1218–1231.

- Zeitoun, M., Lankford, B., Krueger, T., Forsyth, T., Carter, R., Hoekstra, A. Y., … Matthews, N. (2016). Reductionist and integrative research approaches to complex water security policy challenges. Global Environmental Change, 39, 143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.010