ABSTRACT

REDD+ was designed globally as a results-based instrument to incentivize emissions reduction from deforestation and forest degradation. Over 50 countries have developed strategies for REDD+, implemented pilot activities and/or set up forest monitoring and reporting structures, safeguard systems and benefit sharing mechanisms (BSMs), offering lessons on how particular ideas guide policy design. The implementation of REDD+ at national, sub-national and local levels required payments to filter through multiple governance structures and priorities. REDD+ was variously interpreted by different actors in different contexts to create legitimacy for certain policy agendas. Using an adapted 3E (effectiveness, efficiency, equity and legitimacy) lens, we examine four common narratives underlying REDD+ BSMs: (1) that results-based payment (RBP) is an effective and transparent approach to reducing deforestation and forest degradation; (2) that emphasis on co-benefits risks diluting carbon outcomes; (3) that directing REDD+ benefits predominantly to poor smallholders, forest communities and marginalized groups helps address equity; and (4) that social equity and gender concerns can be addressed by well-designed safeguards. This paper presents a structured examination of eleven BSMs from within and beyond the forest sector and analyses the evidence to variably support and challenge these narratives and their underlying assumptions to provide lessons for REDD+ BSM design. Our findings suggest that contextualizing the design of BSMs, and a reflexive approach to examining the underlying narratives justifying particular design features, is critical for achieving effectiveness, equity and legitimacy.

Key policy insights

A results-based payment approach does not guarantee an effective REDD+; the contexts in which results are defined and agreed, along with conditions enabling social and political acceptance, are critical.

A flexible and reflexive approach to designing a benefit-sharing mechanism that delivers emissions reductions at the same time as co-benefits can increase perceptions of equity and participation.

Targeting REDD+ to smallholder communities is not by default equitable, if wider rights and responsibilities are not taken into account

Safeguards cannot protect communities or society without addressing underlying power and gendered relations.

The narratives and their underlying generic assumptions, if not critically examined, can lead to repeated failure of REDD+ policies and practices.

1. Introduction

Since it was first proposed in 2005, the mechanism for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and the enhancement of carbon stocks (REDD+) has involved a wide range of policies, measures and practices. State and non-state actors are implementing REDD+ policies and projects at global, national and sub-national levels based on a diversity of ideas and perspectives of what constitutes REDD+, even as the same actors continue to negotiate on various aspects of its design. One aspect of REDD+ that generates debate is that of benefit sharing (Dunlop & Corbera, Citation2016), defined as the ‘distribution of indirect and direct net gains from the implementation of REDD+’ (Luttrell et al., Citation2013, p. 54).

Conceptualizations of REDD+ have evolved over the past decade (Angelsen, Citation2017), yet REDD+ remains at its core a financial mechanism directing incentives such as results-based payments (RBPs) towards countries and areas tackling deforestation. The Paris Agreement, by highlighting REDD+ as both a result-based incentive and a policy approach,Footnote1 has increased a focus on performance. With this turn, discussions on benefit sharing reflect heightened concerns of how to access REDD+ finance, of assessing REDD+ policy performance and results, of generating co-benefits, and of resolving issues around equity and safeguards (Wong et al., Citation2016).

These discussions are notable extensions to early debates on benefit sharing, which shied away from looking beyond the local level and generally dealt with the ‘why’, ‘to whom’, ‘what’ and ‘how’ REDD+ finance should be spent and distributed at the local level. As a consequence, hard questions remain about how REDD+ financial flows should accrue across a nation or at jurisdictional levels. Despite these changes, discussions in the scholarly literature on the evolution and expectations for REDD+ now that the Paris Agreement is in force highlight how concerns around benefit sharing continue to be entangled in four common narratives that have persisted since the early days of REDD+ (see for example, Corbera & Schroeder, Citation2017; Hein, Guarin, Frommé, & Pauw, Citation2018; Skutsch & Turnhout, Citation2018; Turnhout et al., Citation2017). We summarize the narratives as follows: (1) RBP is an effective and transparent approach to reducing deforestation and forest degradation; (2) emphasis on co-benefits risks diluting carbon outcomes; (3) directing REDD+ benefits predominantly to poor smallholders, forest communities and marginalized groups helps address equity; and (4) social equity and gender concerns can be addressed by well-designed safeguards.

The first narrative around RBPs stems from the initial idea of REDD+ as an international Payment for Environmental Services (PES) scheme, in which payments conditional upon reduced emissions were considered as both effective and efficient (Angelsen et al., Citation2009; Wunder, Citation2009). This idea continued even as REDD+ shifted from the notion of a market-based mechanism to that of a mechanism based on performance-based aid (Angelsen Citation2017), despite mixed evidence and skepticism around conditionality in the aid sector (Paul, Citation2015). The second narrative revolves around the risks of a backlash to the inclusion of multiple co-benefits of livelihoods, biodiversity and development onto the REDD+ agenda. Early concerns that a REDD+ solely focused on carbon benefits would lead to a ‘carbonization’ of forest governance at the expense of other non-carbon benefits (Vijge, Brockhaus, Di Gregorio, & Muharrom, Citation2016; Visseren-Hamakers, McDermott, Vijge, & Cashore, Citation2012) led to a focus on co-benefits, which were also seen as more likely to be achieved (Turnhout et al., Citation2017). In response, fears that REDD+ would lose its focus from reducing (measurable) carbon emissions increasingly began to emerge (Brockhaus, Di Gregorio, & Mardiah, Citation2014). The third narrative on the importance of directing benefits predominantly to poor smallholder and forest communities stems from concerns that REDD+ projects might create new risks and few benefits for these groups (Peskett, Citation2011; Skutsch, Torres, & Fuentes, Citation2017). This pro-poor equity rationale (Luttrell et al., Citation2013) is reflected in most REDD+ countries’ benefit sharing plans (Pham et al., Citation2013) and in policy and civil society spaces. There is also the expectation that involving communities will increase the legitimacy of REDD+ (Skutsch & Turnhout, Citation2018). The fourth narrative grew from the 16th Conference of the Parties (COP 16) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Cancun in 2010,Footnote2 which established safeguards for REDD+ to protect environmental and social co-benefits and enable more equitable outcomes. The seven safeguards relate to governance, rights, participation, consent, permanence and leakage, and focus on avoiding harm and realizing opportunities for synergies, but with less attention on ‘problem amelioration’ (McDermott, Levin, & Cashore, Citation2011).

We argue that it is important to critically unpack and challenge these narratives. These simplified stories describe problems, identify and label selected root causes and perpetrators, and justify proposed solutions (Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005). Narratives are understood to be an integral facet of policy-making, as policy necessarily acts on a simplified version of ‘reality’ and requires a clear cultural script for action (Leach & Fairhead, Citation2002). However, if left unchallenged, these narratives may solidify into homogenous understanding of the problem and lead to narrowly defined policies that are not reflective of the complexity of the deforestation problem.

We briefly outline methods and data in the next section. We then illustrate and analyse the four narratives around benefit sharing using evidence from our reviews and case study research of eleven BSMs from within and beyond the forest sector. We discuss each narrative in light of these findings and highlight implications for an effective, efficient, equitable and legitimate REDD+.

2. Methods and approaches

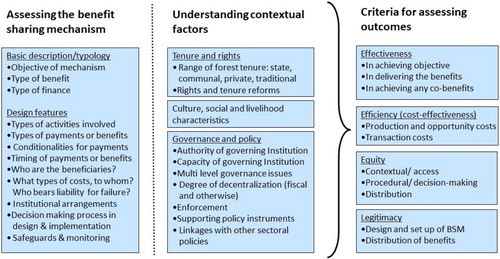

We combine results of extensive literature reviews of BSMs in sectors other than REDD+, case study research on BSMs in practice, and existing scholarly literature on REDD+. First, in our reviews and case studies, we identified design features of these BSMs and the contexts in which they emerge, and applied an adapted 3E (effectiveness, efficiency, equity and legitimacy) lens to assess the outcomes of these BSMs (Wong et al., Citation2017; see ). We matched design features and criteria of BSMs with key terms and framings based on common themes in the scholarly literature. For example, safeguards and monitoring as design features, and outcomes such as social equity, are crucial to consider when assessing an existing BSM (Visseren-Hamakers et al., Citation2012; Vijge et al., Citation2016). These terms and framings are reflected in particular narratives, such as that the establishment of safeguard systems in REDD+ will deliver social equity. In a final step, we then examined how findings from our BSM reviews and case study assessments variably support (or not) the different narratives and the contextual conditions underlying them.

Figure 1. Framework used for assessing BSMs: design features, contextual factors and outcome criteria.

Note: How a specific set of design features in a BSM can lead to specific outcomes will depend on which contextual factors are in place and how they interrelate.

As part of a Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR)-led project on REDD+ benefit sharing,Footnote3 we carried out extensive reviews and empirical case studies of related governance practices from within and beyond the forest sector to draw lessons for REDD+ (see ). These were selected on the basis that they are functioning BSMs, and provide a case to examine a specific BSM design feature and/or a specific contextual factor (i.e. governance practice). A variety of institutional means, governance structures and instruments to distribute benefits from natural resource provision have already been implemented, in some cases, for decades. To structure the reviews, we developed an analytical framework to pull out targeted lessons for REDD+ (see ). The reviews and case studies looked at a range of basic benefit sharing characteristics (type of finance, benefits and objectives) and design features (targeting, activities, allocation of benefits and decision-making processes) of the BSMs, and how they can lead to outcomes in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, equity and legitimacy. We consider contextual factors (such as tenure, governance and policy) as critically important as they both affect how the design features translate into certain outcomes and inform how the outcomes should be interpreted and understood for their relevance and applicability to other settings. For example, the case studies in Vietnam and Cameroon focused on how equity is perceived within the different contexts in relation to the BSM reviewed. In addition, we also derived information from the ongoing Global Comparative Study on REDD+Footnote4 also led by CIFOR for broader policy and contextual understanding.

Table 1. List of reviewed BSMs and governance practices to derive lessons for REDD+.

We understand ‘effectiveness’ as the extent to which REDD+ achieves reduced emissions. In the case of our reviews and case studies, effectiveness relates to the extent to which the reviewed BSM achieves its specific objectives. ‘Efficiency’ is defined as the relative costs of options to achieve the outcomes, and ‘equity’ as the distributional aspects of costs and benefits and the procedural aspects of decision-making within the specific contexts of access, power and capabilities (Angelsen et al., Citation2009; McDermott, Mahanty, & Schreckenberg, Citation2013). Following Luttrell et al. (Citation2013), a system is legitimate when it is ‘justifiable, according to given moral principles and social norms, with evidence of consent and acknowledgment by the governed to validate the ruler’s claim to authority’ (p. 59). The reviews and case studies were produced and peer reviewed by external experts in the relevant sectors between 2013 and 2017. Most were published as briefs or technical papers to facilitate immediate sharing during a period of high demand for such information, and to increase accessibility among different types of stakeholders.

We synthesized the information gathered from these reviews and case studies around four narratives in the benefit sharing debate drawing lessons as to how similar concerns have been addressed in other sectors. The process of synthesizing the information was iterative and deductive; it involved engaging at least one author of each of the reviews/case studies to summarize key insights or lessons relative to the outcomes, particularly in connection to the basic characteristics and design features of the BSM in question, and in the interplay with different contextual factors. Insights often appear contradictory at first given the diverse socio-cultural and political contexts. To resolve these, there were regular discussions and debates amongst the authors to identify those lessons that are relevant and transferable, and under what conditions. We used this process to extract the evidence and lessons salient to addressing the narratives highlighted here.

3. Results and discussion

This section is structured following the four narratives, identifying the lessons derived from our reviews and case studies, and discussing their implications for REDD+ in terms of the outcome criteria of its effectiveness in reaching the objectives, cost efficiency, equity and legitimacy (see summary in ).

Table 2. Linkages between the reviews/case studies with the analytical framework and outcomes.

3.1. Results-based payment is an effective and transparent approach to reducing deforestation and forest degradation

Conditional aid has been used to induce policy reform since the 1980s, notably with the Structural Adjustment Programs of the World Bank (Angelsen, Citation2017). With REDD+ funding dominated by development aid, the narrative of conditionality is gaining traction (Birdsall & Kuczynski, Citation2015) and is particularly appealing to donors as development budgets contract (Seymour & Busch, Citation2016). Savedoff (Citation2016, p. 1) argues that a cash-on-delivery model for REDD+ would provide ‘greater recipient autonomy, simplicity, and transparency’ as governments would realign behaviour to achieve agreed results – but only if the results are well-defined, agreed upon and adequately rewarded. In the 1990s, mixed efficacy from aid conditionality led to the call for linking conditions to domestic political preferences and interests (Collier, Guillaumont, Guillaumont, & Gunning, Citation1997). Similarly, Brockhaus et al. (Citation2016) advise that REDD+ policy reforms require critical factors such as national ownership, coalitions for change, and inclusive policy processes, and state autonomy from key interests in deforestation, all major challenges in their own right.

The experience to date shows the importance of intermediary steps such as the establishment of governance structures. What would be considered as outcomes from REDD+ are quite different depending on the scale and the phase of REDD+ implementation, and would require different metrics for measuring performance (Wertz-Kanounnikoff & McNeill, Citation2012). At the global level, REDD+ finance has largely been allocated for REDD+ institutional- and capacity-building activities, development of national REDD+ strategies and to a lesser extent, for policy reforms. In this regard, identifying and defining unambiguous indicators for REDD+ performance will be a negotiated process.

It is not always clear how performance for RBPs would be reflected at different levels. In the case of Brazil, international donors (primarily Norway and Germany) have made payments into the Amazon Fund based on Brazil’s reduced emissions from lowered deforestation rates (Forstater, Nakhooda, & Watson, Citation2013; van der Hoff, Rajão, & Leroy, Citation2018). However, the Amazon Fund does not allocate finance for reduced emissions at local levels, but for intermediary steps such as monitoring and control, promotion of sustainable production, and land and territorial planning (Gebara et al., Citation2014). While conditionality is often a lauded feature of REDD+, there is ongoing debate whether conditionality is always required for achieving programme objectives. Evidence from the programme to reduce school dropout rates in Malawi demonstrates that both conditional cash transfer (CCT) and unconditional cash transfer (UCT) approaches produce desired measurable impacts. There is some evidence that CCT programmes are more effective but UCT programmes are considered as more equitable (Wong, Citation2014). There are also efficiency implications as more defined conditionality criteria to increase effectiveness or more complex eligibility criteria to ensure equity outcomes will entail higher costs to implement and to monitor. The national Payment for Forest Environmental Service (PFES) programme in Vietnam distributes payments based on inputs or as equal payments to meet local equity concerns rather than on outcomes (Le, Loft, Tjajadi, Pham, & Wong, Citation2016; Pham et al., Citation2014). It is shown that PFES not based on conditions can still be effective if it is perceived as equitable (Le et al., Citation2016; Loft et al., Citation2017). Other experiences from PES recommend linking conditional payments to effort and input, so long as the ecosystem service is maintained (Loft, Pham, & Luttrell, Citation2014). Targeting benefits in this way to the objective of the benefit-sharing mechanism increases efficiency (Loft et al., Citation2014).

Similar to the national level, evidence from PES and certification and standards programmes suggests that up-front payments that are not results-based and regular payments based on interim progress can be effective at the local level (Loft et al., Citation2014; Tjajadi, Yang, Naito, & Arwida, Citation2015). Upfront payments have enabled wider participation in the programmes, including among poorer stakeholders, and helped to mitigate some of the risks and costs involved. In addition, regular payments based on agreed performance benchmarks have motivated participants to maintain their commitment to programme objectives. Although this approach will increase the overall costs, one might also argue that it is better to pay twice for a result than to pay once for no result (Angelsen, Citation2017). Aimed at improving social, economic and environmental conditions of rural areas in the EU, the Rural Development Program developed a flexible, mixed payment approach that provides differential payments at different phases of implementation. Inputs into specified actions (for example, tree planting) are compensated in the initial ‘establishment costs’ and further payments are made annually based on ‘maintenance costs’. Such payments are differentiated according to the opportunity costs of land and the type of trees/forest being cultivated, (Yang, Wong, & Loft, Citation2015).

So, while RBPs can contribute to effective reduced emissions, these findings suggest that from local to national levels, an effective payment approach has to consider how results are defined and agreed, and include mixed approaches to enable social and political acceptance.

3.2. Emphasis on co-benefits risks diluting carbon outcomes

The experimental character of REDD+, with a high diversity of pilot projects and flexibility in implementation at the national level (Sills et al., Citation2014; Vijge et al., Citation2016) has meant that REDD+ has stretched to accommodate multiple perspectives and priorities in the different contexts. The most prominent is the inclusion of development and poverty reduction goals. In many countries, REDD+ is being embedded not only in national climate change strategies or nationally determined contributions (NDCs), but also within narratives around green growth/ green economy/ low carbon emission development and sustainable landscape approaches (Pham, Moeliono, Brockhaus, Le, & Katila, Citation2017), highlighting the dynamism of how narratives collide or collude. Cameroon, for example, considers ‘REDD+ as a tool for development and improvement of livelihoods’ (Cameroon ER-PIN, Citation2016, p. 16). While this strategy may be useful for broader political and social acceptance of REDD+, there are also concerns that REDD+ would be diverted from needed policy reforms to tackle the drivers of deforestation and forest degradation. Recent studies have highlighted this potential discord when linking malleable concepts such as the green economy or green growth with REDD+, and the conventional worldview of economic growth and technical and market solutions tends to dominate over reforms (Pham et al., Citation2017).

At the local level, priorities for co-benefits are most obvious and in many cases necessary. State and REDD+ project implementers collaborate in various ways to redistribute benefits, rights and services to targeted communities or sectors, with the explicit expectation that these lead to improved production and consumption practices and ultimately to forest conservation behaviour. Case analyses of 23 REDD+ initiatives (Sills et al., Citation2014) show that most are rooted in integrated conservation and development project blueprints and leverage on the co-benefits of poverty alleviation and welfare improvement. For example, incentives in the form of agriculture extension services are designed to shift communities away from subsistence practices that are seen as forest degrading. The nuances and underlying local motivations for behaviour change, however, are highly contextual and how co-benefits are perceived can either support or hinder the objectives of REDD+.

Analyses of case studies around land use and benefit sharing arrangements in Peru and Indonesia emphasize the importance of co-benefits (capacity building, infrastructure and access to natural resource decisions) particularly when direct monetary benefits are uncertain or small (Kowler, Tovar, Ravikumar, & Larson, Citation2014; Myers, Ravikumar, & Larson, Citation2015). Participants in REDD+ have also leveraged on the policy process to secure rights to land (Duchelle et al., Citation2018; Myers, Sanders, Larson, & Ravikumar, Citation2016). Studies of Vietnam PFES highlight that how benefits are structured can have significant impacts on perceptions of wellbeing and equity (Pham et al., Citation2014; Pham, Wong, Le, & Brockhaus, Citation2016). Benefits and co-benefits are more likely to be influenced by social and political relationships rather than economic motivation alone (Haas, Loft, & Pham, Citation2019). For rural communities in Vietnam, the focal point of information is the village authority, and levels of trust in the authority significantly influence expressed preferences over how PFES benefits should be distributed, along with local interpretations of equity. Where there is little trust, villagers perceive direct cash payments divided equally across all participants to be most equitable, even though the payments are likely to be minimal. Where there is trust, they are more likely to express preferences for co-benefits such as local infrastructure and social services.

There are also cases of non-monetary burdens associated with intended benefits. The assessment of different cases of land use change to protected areas, community forestry schemes, REDD+ projects and oil palm plantations in Indonesian Kalimantan (Myers et al., Citation2015, Citation2016) highlighted issues such as conflicts related to payments, reduced access to land and livelihood impacts, reduced tenure security and perceived injustices related to decision-making processes. In most of these cases, communities considered the benefits they received to be inadequate compensation for the burdens. These perceived burdens have also undermined conservation behaviour (Myers & Muhajir, Citation2015). In Cameroon, overly cumbersome bureaucracy and opaque processes of the state fiscal system in redistributing forest and wildlife tax revenues not only deprives local communities of needed finance and development co-benefits, but has potentially reinforced the marginalization of minorities (Assembe-Mvondo, Wong, Loft, & Tjajadi, Citation2015).

In the design of a BSM, the timing for delivery of payments and benefits can also generate co-benefits. In our studies of the PFES programme in Vietnam, the timing of payments is generally erratic and dictated by limited local government resources, and often does not match local needs for investments related to farming seasons or schooling periods (Pham, Wong, et al., Citation2016). This results in missed opportunities for generating useful development co-benefits as there is evidence that a pattern of fixed, regular and predictable transfers can help strengthen household productivity (Wong, Citation2014). The role of forests within livelihood strategies, trust in local governance structures, culture, perceptions of injustice or inequity, and risk behaviour all play roles in how the design of a REDD+ BSM can generate both reduced carbon emissions and co-benefits. This calls for a BSM that incorporates a flexible and reflexive approach, rather than a top-down benefit sharing structure focusing exclusively on performance in avoided deforestation. Evidence suggests that the narrative of co-benefits overloading REDD+ is flawed. As financing for REDD+ is still inadequate relative to the opportunity costs of deforestation (Seymour & Busch, Citation2016), co-benefits will likely remain integral to the objectives of REDD+.

3.3. Directing REDD+ benefits predominantly to poor smallholders, forest communities and marginalized groups helps address equity

Equity concerns are multi-dimensional and not as easily measured. The prevalent rationales on equity in REDD+ range from arguing that benefits should go to those with legal rights over the forest, to forest stewards who have been managing forests, to those incurring costs as a consequence of REDD+, to effective facilitators of REDD+ implementation, and to the poor (Luttrell et al., Citation2013). In practice, these rationales are not distinct from each other, but rather interweave in ways that reflect socio-political values and current policy objectives. An influential rationale expressed by most policy and non-government actors is that REDD+ should have a pro-poor focus and be targeted to the poor smallholder communities living near forests (Atela, Minang, Quinn, & Duguma, Citation2015). Indeed, many REDD+ pilot initiatives have focused on forest conservation activities involving poor smallholders with upfront livelihood and social welfare activities (Sills et al., Citation2014).

The targeting of poor smallholders and forest communities raises the question of effectiveness, if indeed these are the actors driving deforestation and forest degradation. A review of REDD+ country strategies highlights that most tend to focus on activities to reduce forest degradation and enhance forest carbon stocks, rather than on tackling deforestation typically caused by large commercial actors (Salvini et al., Citation2014). This need to involve communities runs throughout REDD+ policy documents and programmes, and not only problematically evokes simplistic notions of egalitarianism and legitimacy but also ignores inequalities within communities (Skutsch & Turnhout, Citation2018). Targeting local communities is perhaps politically easier than tackling powerful large-scale drivers of deforestation that are often tied to national growth ambitions (Thaler & Anandi, Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2016).

REDD+ initiatives also involve a transfer of costs and burdens. The emphasis on communities as critical to REDD+ success is also accompanied by recognition that they often do not have formal rights to the forest (Skutsch & Turnhout, Citation2018). Land rights is at the core of the politics of forest and land use in many places (see Myers et al. (Citation2016) and Thaler and Anandi (Citation2017) for cases in Kalimantan, and Yang et al. (Citation2016) for Vietnam). As many REDD+ or PES payments are combined with the allocation of certain rights and conditions over forest resources, authorities are reshaping the motivations and the material practices of communities by restricting or delegitimizing certain local land uses, or by trading short-term management rights for long-term tenure.

Experience from the extractives sector (Luttrell & Betteridge, Citation2017) points to the advantages of targeting benefits to those incurring costs or holding ownership rights. If emission reduction is classified as a national good (Loft et al., Citation2015) or incurs costs to the nation, the accrual of REDD+ revenues across the whole nation may be perceived to be a more equitable approach with better development outcomes. The reality is that trade-offs occur and hard choices may be necessary. Finding that balance between effectiveness, efficiency, equity and legitimacy will depend on how REDD+ interventions address the many drivers of forest loss and degradation, the social costs involved (and to whom they accrue), and on recognizing different equity concerns in different contexts. In light of the narrative that seems to equal equity in REDD+ with a smallholder or community focus, our findings suggest a much more complex and uncomfortable reality.

3.4. Gender and social equity concerns can be addressed by well-designed safeguards

The UNFCCC COP 17, held in Warsaw in 2013, established that national-level Safeguard Information Systems (SIS) and regular reporting on social and environmental impacts are prerequisites for REDD+ RBPs (Duchelle & Jagger, Citation2014). This provided an opportunity for safeguards to support more equitable outcomes, and be structured to manage risks to REDD+ results (Brockhaus et al., Citation2014). The legitimacy of REDD+ benefit-sharing arrangements, for example, are compromised when there is a lack of inclusive consultation with, and participation of, groups that consider themselves to be stakeholders (eg local institutions and actors, customary authorities and indigenous leaders). This lack has resulted in local conflicts that undermine conservation behaviour (Gebara et al., Citation2014; Kowler et al., Citation2014; Myers et al., Citation2015). The Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) processes embedded in certification and standards is seen as an avenue for local stakeholders to negotiate and secure rights to resources (Tjajadi et al., Citation2015). While there is some evidence that FPIC processes in forest certification have helped secure indigenous rights (Cerutti et al., Citation2014), a top down process is common in our case studies on PFES in Vietnam (Le et al., Citation2016; Loft et al., Citation2017), forest, wildlife and land fees redistribution in Cameroon (Assembe-Mvondo, Brockhaus, & Lescuyer, Citation2013, Assembe-Mwondo et al., Citation2015), and in the case of the Kayapo indigenous fund in Brazil (Gebara et al., Citation2014). Examples of top down processes often result in sessions to disseminate information or decisions rather than meaningful engagement of local groups in decision making.

Safeguarding can be easily relegated as simple checklist exercises for participation without a strategy for addressing power and gendered relations that influence how information is shared and decisions are made (Bee & Sijapati Basnett, Citation2017; Westholm & Arora-Jonsson, Citation2018). Many national REDD+ documents characterize women’s empowerment and gender mainstreaming both as a co benefit and a strategic focus (Westholm & Arora-Jonsson, Citation2018). Indonesia, for example, highlights gender as a cross-cutting concern in both REDD+ strategy and safeguards (Arwida, Maharani, Basnett, & Yang, Citation2017), but gender is only mentioned once with regards to participation. Despite safeguarding for inclusivity at all levels, women continue to be marginalized in such consultation or participatory processes. A comparative study found that women’s participation in, and basic understanding of, REDD+ in five countries (Peru, Brazil, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cameroon) was limited to attending meetings and training while the male-dominated forest user groups engaged with, and participated in, decision making, monitoring and rule enforcement activities (Larson et al., Citation2015).

REDD+ interventions to create transformative forest governance may indeed succeed in changing some of the formal and visible institutional forms, but subtle power relations and socio-political differentiations within local communities and the political arena tend to persist (Brockhaus, Di Gregorio, & Carmenta, Citation2014). In Vietnam, for example, women’s representation on the National REDD+ Committee increased from 13% in 2012–50% in 2015, but all of the women committee members see themselves as narrowly representing the positions of their institutions, and not gender issues (Pham, Mai, Moeliono, & Brockhaus, Citation2016). As a consequence, despite representation, gender concerns and preferences in BSM design are invisible, increasing the risk of REDD+ inadvertently reinforcing structures that widen inequality. In many cases, social and gender equity in REDD+ is simplistically equated to widened economic opportunities, increased incomes and access to non-timber forest products. However, local elites in many rural and forest communities hold power of access to information and exert influence over local decision-making processes to capture a disproportionately larger share of the benefits. Elite capture does not only occur at the local level – it is also identified as one of the major constraints to the implementation of equitable REDD+ BSMs at all levels of governance where land rights and institutions are weak and participation in decision-making processes are constrained (Assembe-Mvondo et al., Citation2015; Pham et al., Citation2014). The study on forest, wildlife and land revenue redistribution in Cameroon highlighted the urgent need for the forest financial committees to be made more accountable and transparent (Assembe-Mvondo et al., Citation2013; Assembe-Mvondo et al., Citation2015), signalling the importance of a grievance mechanism and verification of REDD+ benefits (Pham, Wong, et al., Citation2016; Tjajadi et al., Citation2015).

Safeguards can only act as an effective grievance and dispute resolution mechanism if countries develop adequate social and institutional criteria and indicators and monitoring procedures. Dispute-resolution mechanisms will need to identify multiple platforms (including intermediaries), acknowledge and incorporate traditional methods, and find culturally appropriate ways for handling and resolving disputes in order to be more accessible to indigenous and local communities and smallholders (Tjajadi et al., Citation2015).

There are several lessons to be learnt from different sectors in the governance of REDD+ and in the design of safeguards for transparency, multi-stakeholder engagement and coordination, and authority. The study on Anti-Corruption Measures in Indonesia highlighted the important roles of sub-national and local-level governance structures in monitoring and verification and in particular, the need for appropriate authority to coordinate functions (Arwida, Mardiah, & Luttrell, Citation2015). One example of a governance structure is the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative, which creates a platform for transparent monitoring of industry royalties and government revenues implemented through multi-stakeholder coalitions in member countries (Arwida et al., Citation2015). Multi-stakeholder processes are also key in the Forest Law Enforcement and Trade Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA) development process in Indonesia, demonstrating that accountability and transparency can be enhanced by clarifying roles, responsibilities and decision-making mandates (Luttrell & Fripp, Citation2015). The VPA have structured their timber legality assurance systems to enable independence in auditing and monitoring. While independence can generate credibility and trust, its impact can be enhanced by official recognition of its role, by establishing complaints mechanisms and by formalizing access to information. All these practices contribute towards legitimacy of an initiative.

The design of safeguards will need to be deeply rooted in context to be relevant to realities. The findings also highlight that a critical feature for effective safeguarding of a community and society, namely making claims in cases of violations to hold state and non-state actors to account, will require shifts in power relations. Theses shifts have not yet resulted from the establishment of REDD+ safeguards.

3.5. Cross cutting issues

Our assessment of the four REDD+ benefit sharing narratives highlighted common themes. A key theme relates to how equity and legitimacy can resonate with effectiveness. For example, effectiveness and equity can be achieved via mixed and flexible payment mechanisms that are responsive to local contextual conditions, as implemented by some certification and standards programmes such as Fairtrade, and EU Rural Development Policy. However, these come with higher costs of implementation and can affect efficiency. Further, co-benefits as integral to supporting local welfare outcomes and commitment is evident in the Vietnam PFES where monetary benefits are often trivial compared to opportunity costs. Likewise directing REDD+ benefits predominantly to poor stakeholders is not necessarily either effective or equitable, when other more powerful actors are the bigger threat to forests. Contextualizing the design of a BSM to address drivers and actors related to forest loss can bring increased accountability and legitimacy. Concerns around the inclusion of gender and poor smallholder communities in REDD+ remain high on the environmental-social justice agenda and cannot be addressed by safeguard checklists alone. Supporting shifts in power and gendered relations may – at the first glance – come at the expense of short term efficiency, nevertheless this would be wholly necessary if REDD+ is to be a game changer for meeting its goal of emission reductions effectively and equitably. This corroborates the argumentation of Brockhaus and Angelsen (Citation2012) that to achieve a major change away from business as usual will require not only shifts in economic incentives and discursive practices, but also shifts in power relations. The evidence from our reviews and case studies challenges the assumptions behind the four narratives and calls for a re-set of policies based on them.

4. Conclusion

The narratives colouring debates in REDD+ benefit sharing have been quite persistent even as conceptualizations of REDD+ have evolved over the past decade. These narratives not only influence the selection of BSMs by REDD+ policymakers (Pham et al., Citation2013), and definitions of who should benefit and why (Luttrell et al., Citation2013), but they are also borne out of discourses related to the prioritization of REDD+ objectives and actions (Di Gregorio et al., Citation2015). If left critically unexamined, there is a risk that the wider literature on REDD+ repeats to some extent the same unjustified assumptions and contributes to the persistence of these narratives in policy making without due attention to the structural inequities and contextual nuances that affect outcomes (Kemerink-Seyoum, Tadesse, Mersha, Duker, & De Fraiture, Citation2018).

This paper provides evidence that conditionality is not always a necessary prerequisite for REDD+ to be effective and efficient, and performance indicators for RBP should aim for transformative reforms. Additionally, co-benefits are shown to be an important mix in REDD+ BSMs to support equity concerns and should be designed based on contextual relevance. There is evidence that targeting poor smallholders and communities as REDD+ beneficiaries to address equity and legitimacy concerns may overlook the larger scale drivers to effectively reduce deforestation and will require an examination of how burdens are transferred. Last, but not least, the paper shows that social and gender equity concerns cannot be addressed by safeguards alone without examining underlying power and gendered relations. These findings still hold true with the shift of REDD+ towards a development-oriented agenda. What becomes more prominent is the contextualization of forest governance and drivers of deforestation, and their underlying politics. Context-relevant safeguards for enabling inclusivity in decision processes, transparency of information and accountability measures will play even more important roles for equity and legitimacy in REDD+.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Article 5.2 of the Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf, accessed 10 May 2018.

2 Safeguards are detailed in paragraph 2 of Appendix 1 in the Cancun Agreement: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf, accessed April 30, 2019.

3 The CIFOR project ‘Opportunities and challenges for implementing REDD+ benefit sharing mechanisms in developing countries’ was implemented from 2012 to 2016 with case studies in Brazil, Peru, Cameroon, Tanzania, Indonesia and Vietnam.

References

- Angelsen, A. (2017). REDD+ as result-based aid: General lessons and bilateral agreements of Norway. Review of Development Economics, 21(2), 237–264. doi: 10.1111/rode.12271

- Angelsen, A., Brockhaus, M., Kanninen, M., Sills, E., Sunderlin, W. D., & Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S. (2009). Realising REDD+: National strategy and policy options. Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

- Arwida, S., Maharani, C., Basnett, B. S., & Yang, A. L. (2017). Gender relevant considerations for developing REDD+ indicators: Lessons learnt for Indonesia (Info Brief 173). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Arwida, S., Mardiah, S., & Luttrell, C. (2015). Lessons for REDD+ benefit-sharing mechanisms from anti-corruption measures in Indonesia (Info Brief 120). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Assembe-Mvondo, S., Brockhaus, M., & Lescuyer, G. (2013). Assessment of the effectiveness, efficiency and equity of benefit-sharing schemes under large-scale agriculture: Lessons from land fees in Cameroon. The European Journal of Development Research, 25(4), 641–656. doi: 10.1057/ejdr.2013.27

- Assembe-Mvondo, S., Wong, G., Loft, L., & Tjajadi, J. (2015). Comparative assessment of forest revenue redistribution mechanisms in Cameroon: Lessons for REDD+ benefit sharing (Working Paper 190). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Atela, J. O., Minang, P. A., Quinn, C. H., & Duguma, L. A. (2015). Implementing REDD+ at the local level: Assessing the key enablers for credible mitigation and sustainable livelihood outcomes. Journal of Environmental Management, 157, 238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.04.015

- Bee, B. A., & Sijapati Basnett, B. (2017). Engendering social and environmental safeguards in REDD+: lessons from feminist and development research. Third World Quarterly, 38(4), 787–804. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1191342

- Birdsall, N., & Kuczynski, P. P. (2015). Look to the forests: How performance payments can slow climate change. Working group on performance-based payments to reduce tropical deforestation. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

- Brockhaus, M., & Angelsen, A. (2012). Seeing REDD+ through 4Is: A political economy framework. In Analysing REDD+: Challenges and choices (pp. 15–30). Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research.

- Brockhaus, M., Di Gregorio, M., & Carmenta, R. (2014). REDD+ policy networks: Exploring actors and power structures in an emerging policy domain. Ecology and Society, 19(4), 1–32. doi: 10.5751/ES-06799-190401

- Brockhaus, M., Di Gregorio, M., & Mardiah, S. (2014). Governing the design of national REDD+: An analysis of the power of agency. Forest Policy and Economics, 49, 23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2013.07.003

- Brockhaus, M., Korhonen-Kurki, K., Sehring, J., Di Gregorio, M., Assembe-Mvondo, S., Babon, A., … Zida, M. (2016). REDD+, transformational change and the promise of performance-based payments: A qualitative comparative analysis. Climate Policy, 17(6), 708–730. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2016.1169392

- Brockhaus, M., Wong, G., Luttrell, C., Loft, L., Pham, T. T., Duchelle, A., … Di Gregorio, M. (2014). Operationalizing safeguards in national REDD+ benefit-sharing systems: Lessons on effectiveness, efficiency and equity (REDD+ Safeguard Brief 2). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Cameroon ER-PIN. (2016). Forest carbon partnership fund emissions reductions program idea note (ER-IN) final. Retrieved from http://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/cameroon

- Cerutti, P. O., Lescuyer, G., Tsanga, R., Kassa, S. N., Mapangou, P. R., Mendoula, E. E., … Yembe, R. Y. (2014). Social impacts of the forest stewardship council certification: An assessment in the Congo Basin (Occasional Paper 103). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Collier, P., Guillaumont, P., Guillaumont, S., & Gunning, J. W. (1997). Redesigning conditionality. World Development, 25(9), 1399–1407. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00053-3

- Corbera, E., & Schroeder, H. (2017). REDD+ crossroads post Paris: Politics, lessons and interplays. Forests, 8, 508. doi: 10.3390/f8120508

- Di Gregorio, M., Brockhaus, M., Cronin, T., Muharrom, E., Mardiah, S., & Santoso, L. (2015). Deadlock or transformational change? Exploring public discourse on REDD+ across seven countries. Global Environmental Politics, 15(4), 63–84. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00322

- Duchelle, A. E., & Jagger, P. (2014). Operationalizing REDD+ safeguards: Challenges and opportunities (Safeguards Brief 1). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Duchelle, A. E., Seymour, F., Brockhaus, M., Angelsen, A., Larson, A. M., Moeliono, M., … Martius, C. (2018). REDD+: Lessons from national and subnational implementation. Ending tropical deforestation series. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- Dunlop, T., & Corbera, E. (2016). Incentivizing REDD+: How developing countries are laying the groundwork for benefit-sharing. Environmental Science & Policy, 63, 44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2016.04.018

- Forstater, M., Nakhooda, S., & Watson, C. (2013). The effectiveness of climate finance: A review of the Amazon Fund. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Gebara, F., Muccillo, L., May, P., Vitel, C., Loft, L., & Santos, A. (2014). Lessons from local environmental funds for REDD+ benefit sharing with indigenous people in Brazil (Info Brief 98). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Haas, J. C., Loft, L., & Pham, T. T. (2019). How fair can incentive-based conservation get? The interdependence of distributional and contextual equity in Vietnam’s payments for forest environmental services program. Ecological Economics, 160, 205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.02.021

- Hajer, M., & Versteeg, W. (2005). A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7, 175–184. doi: 10.1080/15239080500339646

- Hein, J., Guarin, A., Frommé, E., & Pauw, P. (2018). Deforestation and the Paris climate agreement: An assessment of REDD+ in the national climate action plans. Forest Policy and Economics, 90, 7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2018.01.005

- Kemerink-Seyoum, J. S., Tadesse, T. M., Mersha, W. K., Duker, A. E. C., & De Fraiture, C. (2018). Sharing benefits or fueling conflicts? The elusive quest for organizational blue-prints in climate financed forestry projects in Ethiopia. Global Environmental Change, 53, 265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.007

- Kowler, L., Tovar, J., Ravikumar, A., & Larson, A. (2014). The legitimacy of multilevel governance structures for benefit sharing REDD+ and other low emissions options in Peru (Info Brief 101). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Larson, A. M., Dokken, T., Duchelle, A., Atmadja, S., Resosudarmo, I. A. P., Cronkleton, P., … Selaya, G. (2015). The role of women in early REDD+ implementation: Lessons for future engagement. International Forestry Review, 17(1), 43–65. doi: 10.1505/146554815814725031

- Le, D. N., Loft, L., Tjajadi, J. S., Pham, T. T., & Wong, G. Y. (2016). Being equitable is not always fair: An assessment of PFES implementation in Dien Bien, Vietnam (Working Paper 205). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Leach, M., & Fairhead, J. (2002). Changing perspectives on forests: Science/policy processes in wider society. IDS Bulletin, 33, 1–12.

- Loft, L., Gebara, M. F., & Wong, G. Y. (2016). The experience of ecological fiscal transfers: Lessons for REDD+ benefit sharing (Occasional Paper 154). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Loft, L., Le, D. N., Pham, T. T., Yang, A. L., Tjajadi, J. S., & Wong, G. Y. (2017). Whose equity matters? National to local equity perceptions in Vietnam’s payments for forest ecosystem services scheme. Ecological Economics, 135, 164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.01.016

- Loft, L., Pham, T. T., & Luttrell, C. (2014). Lesson from payments for ecosystem services for REDD+ benefit-sharing mechanism (Info Brief 68). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Loft, L., Ravikumar, A., Gebara, M., Pham, T. T., Resosudarmo, I. A. D., Assembe-Mvondo, S., … Andersson, K. (2015). Taking stock of carbon rights in REDD+ candidate countries: Concept meets reality. Forests, 6(4), 1031–1060. doi: 10.3390/f6041031

- Luttrell, C., & Betteridge, B. (2017). Lessons for multi-level REDD+ benefit sharing from revenue distribution in extractive resource sectors (oil, gas and mining) (Occasional Paper 166). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Luttrell, C., & Fripp, E. (2015). Lessons from voluntary partnership agreements for REDD+ benefit sharing (Occasional Paper 134). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Luttrell, C., Loft, L., Gebara, M., Kweka, D., Brockhaus, M., Angelsen, A., & Sunderlin, W. (2013). Who should benefit from REDD+? Rationales and realities. Ecology and Society, 18(4), 52–70. doi: 10.5751/ES-05834-180452

- McDermott, C. L., Levin, K., & Cashore, B. (2011). Building the forest-climate bandwagon: REDD+ and the logic of problem amelioration. Global Environmental Politics, 11, 85–103. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00070

- McDermott, M., Mahanty, S., & Schreckenberg, K. (2013). Examining equity: A multidimensional framework for assessing equity in payments for ecosystem services. Environmental Science & Policy, 33, 416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.10.006

- Myers, R., & Muhajir, M. (2015). Searching for justice: Rights vs ‘benefits’ in Bukit Baka Bukit Raya National Park, Indonesia. Conservation and Society, 13(4), 370–381. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.179886

- Myers, R., Ravikumar, A., & Larson, A. (2015). Benefit sharing in context: A comparative analysis of 10 land-use change case studies in Indonesia (Infobrief 118). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Myers, R., Sanders, A. J., Larson, A. M., & Ravikumar, A. (2016). Analyzing multilevel governance in Indonesia: Lessons for REDD+ from the study of landuse change in Central and West Kalimantan (Working Paper 202). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Nawir, A., Paudel, N., Wong, G., & Luttrell, C. (2015). Thinking about REDD+ benefit sharing mechanism (BSM): Lessons from community forestry (CF) in Nepal and Indonesia (Infobrief 112). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Paul, E. (2015). Performance-based aid: Why it will probably not meet its promises. Development Policy Review, 33, 313–323. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12115

- Peskett, L. (2011). Benefit sharing in REDD+: Exploring the implications for poor and vulnerable people. Washington, DC: World Bank and REDD-net.

- Pham, T. T., Brockhaus, M., Wong, G., Le, N. D., Tjajadi, J., Loft, L., … Assembe-Mvondo, S. (2013). Approaches to benefit sharing: A preliminary comparative analysis of 13 REDD+ countries (Working Paper 108). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Pham, T. T., Mai, Y. H., Moeliono, M., & Brockhaus, M. (2016). Women’s participation in REDD+ national decision-making in Vietnam. International Forestry Review, 18(3), 334–344. doi: 10.1505/146554816819501691

- Pham, T. T., Moeliono, M., Brockhaus, M., Le, D. N., & Katila, P. (2017). REDD+ and green growth: Synergies or discord in Vietnam and Indonesia. International Forestry Review, 19(Suppl. 1), 56–68. doi: 10.1505/146554817822407385

- Pham, T. T., Moeliono, M., Brockhaus, M., Le, N. D., Wong, G., & Le, T. (2014). Local preferences and strategies for effective, efficient, and equitable distribution of PES revenues in Vietnam: Lessons for REDD+. Human Ecology, 42(6), 885–899. doi: 10.1007/s10745-014-9703-3

- Pham, T. T., Wong, G. Y., Le, N. D., & Brockhaus, M. (2016). The distribution of payment for forest environmental services (PFES) in Vietnam: Research evidence to inform payment guidelines (Occasional Paper 163). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Salvini, G., Herold, M., De Sy, V., Kissinger, G., Brockhaus, M., & Skutsch, M. (2014). How countries link REDD+ interventions to drivers in their readiness plans: Implications for monitoring systems. Environmental Research Letters, 9(7), 074004. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/9/7/074004

- Savedoff, W. (2016). How the green climate fund could promote REDD+ through a cash on delivery instrument: Issues and options (Policy Paper no 72). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

- Seymour, F., & Busch, J. (2016). Why forests? Why now? The science, economics and politics of tropical forests and climate change. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Sills, E. O., Atmadja, S. S., de Sassi, C., Duchelle, A. E., Kweka, D. L., Resosudarmo, I. A. P., & Sunderlin, W. D. (2014). REDD+ on the ground: A case book of subnational initiatives across the globe. Bogor: CIFOR.

- Skutsch, M., Torres, A. B., & Fuentes, J. C. C. (2017). Policy for pro-poor distribution of REDD+ benefits in Mexico: How the legal and technical challenges are being addressed. Forest Policy and Economics, 75, 58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2016.11.014

- Skutsch, M., & Turnhout, E. (2018). How REDD+ is performing communities. Forests, 9(10), 638–654. doi: 10.3390/f9100638

- Thaler, G. M., & Anandi, C. A. M. (2017). Shifting cultivation, contentious land change and forest governance: The politics of swidden in East Kalimantan. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(5), 1066–1087. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1243531

- Tjajadi, J., Yang, A., Naito, D., & Arwida, S. (2015). Lessons from environmental and social sustainability certification standards for equitable REDD+ benefit-sharing mechanisms (Infobrief 119). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Turnhout, E., Gupta, A., Weatherley-Singh, J., Vijge, M. J., De Koning, J., Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., … Lederer, M. (2017). Envisioning REDD+ in a post-Paris era: Between evolving expectations and current practice. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 8(1), e425.

- van der Hoff, R., Rajão, R., & Leroy, P. (2018). Clashing interpretations of REDD+ “results” in the Amazon Fund. Climatic Change, 150(3-4), 433–445. doi: 10.1007/s10584-018-2288-x

- Vijge, M. J., Brockhaus, M., Di Gregorio, M., & Muharrom, E. (2016). Framing national REDD+ benefits, monitoring, governance and finance: A comparative analysis of seven countries. Global Environmental Change, 39, 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.002

- Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., McDermott, C., Vijge, M. J., & Cashore, B. (2012). Trade-offs, co-benefits and safeguards: Current debates on the breadth of REDD+. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(6), 646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2012.10.005

- Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S., & McNeill, D. (2012). Performance indicators and REDD+ implementation. In A. Angelsen, M. Brockhaus, W. D. Sunderlin, & L. V. Verchot (Eds.), Analysing REDD (pp. 233–246). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Westholm, L., & Arora-Jonsson, S. (2018). What room for politics and change in global climate governance? Addressing gender in co-benefits and safeguards. Environmental Politics, 27(5), 917–938. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2018.1479115

- Wong, G. (2014). The experience of conditional cash transfers: Lessons for REDD+ benefit sharing (Infobrief 97). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Wong, G., Angelsen, A., Brockhaus, M., Carmenta, R., Duchelle, A., Leonard, S., … Wunder, S. (2016). Results-based payments for REDD+: Lessons on finance, performance, and non-carbon benefits. Bogor: CIFOR.

- Wong, G. Y., Loft, L., Brockhaus, M., Yang, A. L., Pham, T. T., Assembe-Mvondo, S., & Luttrell, C. (2017). An assessment framework for benefit sharing mechanisms to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation within a forest policy mix. Environmental Policy and Governance, 27(5), 436–452. doi: 10.1002/eet.1771

- Wunder, S. (2009). Can payments for environmental services reduce deforestation and forest degradation? In Realising REDD+: National strategy and policy options (pp. 213–224). Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research.

- Yang, A., Nguyen, D. T., Vu, T. P., Le Quang, T., Pham, T. T., Larson, A. M., & Ravikumar, A. (2016). Analyzing multilevel governance in Vietnam: Lessons for REDD+ from the study of land-use change and benefit sharing in Nghe An and Dien Bien provinces (Working Paper 218). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Yang, A., Wong, G., & Loft, L. (2015). What can REDD+ benefit sharing mechanisms learn from the European rural development policy? (Infobrief 126). Bogor: CIFOR.