ABSTRACT

The Global Stocktake (GST) takes a central role within the architecture of the Paris Agreement, with many hoping that it will become a catalyst for increased mitigation ambition. This paper outlines four governance functions for an ideal GST: pacemaker, ensurer of accountability, driver of ambition and provider of guidance and signal. The GST can set the pace of progress by stimulating and synchronizing policy processes across governance levels. It can ensure accountability of Parties through transparency and public information sharing. Ambition can be enhanced through benchmarks for action and transformative learning. By reiterating and refining the long term visions, it can echo and amplify the guidance and signal provided by the Paris Agreement. The paper further outlines preconditions for the effective performance of these functions. Process-related conditions include: a public appraisal of inputs; a facilitative format that can develop specific recommendations; high-level endorsement to amplify the message and effectively inform national climate policy agendas; and an appropriate schedule, especially with respect to the transparency framework. Underlying information provided by Parties complemented with other (scientific) sources needs to enable benchmark setting for collective climate action, to allow for transparent assessments of the state of emissions and progress of a low-carbon transformation. The information also needs to be politically relevant and concrete enough to trigger enhancement of ambition. We conclude that meeting these conditions would enable an ideal GST and maximize its catalytic effect.

Key policy insights

The functional argument developed in this article may inspire a purposeful design of the GST as its modalities and procedures are currently being negotiated.

The analytical framework provided serves as a benchmark against which to assess the GST's modalities and procedures.

Gaps and blind spots in the official GST can and should be addressed by processes external to the climate regime in academia and civil society.

1. Introduction

The Global Stocktake (GST) established in Art. 14 of the Paris Agreement (PA) is a key feature of the new international climate governance architecture. The GST is a process that establishes a feedback mechanism connecting short-term, contemporary climate action with the overall long-term targets of the PA (Northrop, Dagnet, Höhne, Thwaites, & Mogelgaard, Citation2018). Its purpose is to review the implementation of the PA and to ‘assess the collective progress’ towards the collectively agreed goals (UNFCCC, Citation2016b, Art. 14.1).

The GST can be seen as the central cog in the ambition mechanism of the PA. In other words, it is the primary explicit institutional feature of the PA that is supposed to catalyze dynamic increases in the level of ambition over time (Müller & Ngwadla, Citation2016; van Asselt, Citation2016). While other drivers of ambition exist, e.g. the ever increasing engagement of non-state and subnational actors (Chan et al., Citation2019), the GST is supposed to transfer this momentum and galvanize national governments into more ambitious climate action represented in significantly more progressive subsequent Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (cf. UNFCCC, Citation2016b, Art. 4.3). This is required as the discrepancy between the high ambition expressed in the long-term temperature goal and the current ambition level of NDCs remains vast (UNFCCC, Citation2016a). It is therefore necessary that the level of ambition of NDCs is increased considerably in subsequent iterations of the NDC cycle.

Despite the important role of the GST, the corresponding academic literature remains relatively scarce (exceptions that touch upon the GST in various ways include Friedrich, Citation2017; Holz & Ngwadla, Citation2016; Huang, Citation2018; Jacoby, Chen, & Flannery, Citation2017; Milkoreit & Haapala, Citation2017; Milkoreit & Haapala, Citation2018; Müller & Ngwadla, Citation2016; Northrop et al., Citation2018; Tompkins, Vincent, Nicholls, & Suckall, Citation2018; van Asselt, Pauw, & Sælen, Citation2015; Winkler, Mantlana, & Letete, Citation2017). With the adoption of the modalities of the GST as part of the Paris Agreement ‘Rulebook’ at the 24th Conference of the Parties (COP24) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Katowice in 2018, the foundations for the first GST in 2023 have been laid. On the other hand, the provisions are not very detailed and allow for ample flexibility for the negotiation Chairs and Facilitators, as well as the UNFCCC Secretariat, to set it up in a way that maximizes the catalytic effect of the GST (Hale, Citation2018). Focusing on a mitigation perspective, this article aims at providing insights to achieve just this.

In section 2 we propose four governance functions by which the GST can help foster a cycle of climate action leading current, insufficient, levels of ambition towards a self-reinforcing transformation pathway enabling a sustainable and low carbon future. Section 3 then asks what is necessary to fully operationalize the catalytic effect of the GST. We establish process- and information-related conditions to implement the four functions and assess how these conditions are reflected in the modalities of the GST as adopted in Katowice. Section 4 concludes.

2. Functions of the Global Stocktake

Limiting global warming to well below 2°C or even 1.5°C as aspired to in the PA's long-term temperature goal requires a fundamental transformation of global economies and societies. This includes the socio-technical systems that support them. In that sense the PA has institutionalized a transformative ambition. The question is, how can transformational change occur and, more specifically, how can the GST support the required transformational change? The subsequent discussion of the functions of the GST specifies four different functions by which the GST can drive change. These are: (1) acting as a pacemaker to synchronize and stimulate national and subnational policy processes, (2) ensuring accountability, (3) driving NDC ambition, and (4) providing guidance and signal.

2.1. Pacemaker function

North (Citation1990) argues that institutions – the ‘rules of the game’ – are a central determinant of economic behaviour by reducing complexity and enabling routines that allow us to function efficiently. One way in which the GST can support transformative change is by creating new institutions, and new rules, that help to align climate policy-making across various governance levels in order to improve policy coherence and thereby increase ambition.

The PA contains relatively few mandatory legal requirements on nation states in terms of ‘obligations of results’. There are, however, a range of ‘obligations of conduct’ (Oberthür & Bodle, Citation2016): procedural obligations, particularly with respect to the preparation and communication of NDCs – Articles 4.2, 4.3, and 4.8 – and accounting of NDCs as well as greenhouse gas (GHG) emission inventory reporting – Articles 4.13 and 13.7 (Bodansky, Citation2016a).Footnote1

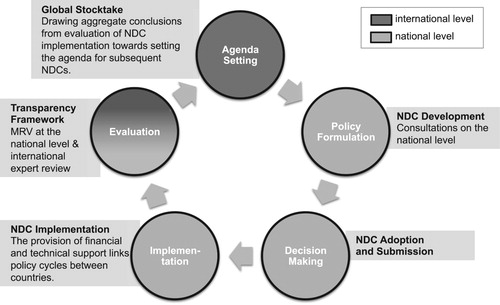

The procedural rules of the PA – the 5-yearly cycle of NDC updates, assessment and review of national action and support, as well as the aggregate assessment of implementation in the form of periodic GSTs – create a ‘pacemaker’ that helps to stimulate and synchronize climate policy processes (Obergassel et al., Citation2016). Essentially, the NDC cycle resembles a prototypical policy cycle (see ) (Jann, Wegrich, Fischer, Miller, & Mara, Citation2007). But what is the specific role of the GST within this policy cycle? The GST reinforces the periodic 5-yearly rhythm of the PA: it bridges the evaluation stage and the agenda setting stage for subsequent NDC cycles. It aggregates the individual country-level evaluations in order to formulate conclusions at the global level. These conclusions will inform the respective national climate policy agendas for the next round of NDCs.

What is required to enable the GST to effectively function as an agenda setting mechanism? First and foremost, the GST can only effectively aggregate and conclude on the individual country evaluations if they are available as inputs in time (also see section 4.1.1).

Secondly, to have a significant effect on national policy processes, the GST's outputs should be formulated in a way that resonates with the national discourse of as many countries as possible. This can be achieved by providing specific information addressing sectoral transformation challenges and providing information targeted to specific actors. Also, aligning information with other relevant international agendas, particularly the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development with its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as UN Habitat's New Urban Agenda, would be beneficial. General statements and mere calls for urgency will most likely not have a strong impact. It may be necessary to differentiate and formulate specific challenges that, for example, correspond to different stages of economic development. For that purpose, data and analyses need to be supplied that enable formulation of nuanced policy narratives at the technical level.

2.2. Ensuring accountability

Climate change has been characterized as a collective action problem (IPCC, Citation2014). In this context, a rationalist theory of (transformative) change is often assumed, according to which change is typically understood to be incremental and market-driven. Prices (whether they are monetary, political, or any other kind) are the drivers of change. The GST could make a contribution by highlighting the costs (incl. political costs) of inaction.

In this regard, one of the key criticisms of the PA is its lack of legal compulsion (Depledge, Citation2016; Rajamani, Citation2016) thus limiting the ability to impose costs for non-compliant governments. To some extent, legal obligation has been substituted by a focus on transparency in the hope that a threat of ‘naming and shaming’ can discipline policy makers to adequately implement their NDCs (Bodansky, Citation2016a; Obergassel et al., Citation2015, Citation2016; Oberthür & Bodle, Citation2016). But what is required in order to make naming and shaming effective and what can the GST contribute to this?

For the ‘naming’ part a key requirement is transparency. Without accurate and sufficiently granular data it remains impossible to determine whether, and to what extent, countries have attained their NDCs. For the ‘shaming’ part, a critical level of public attention is required. The transparency framework will most likely not be sufficient in this regard. It is unlikely that the technical expert reviews, i.e. independent reviews of a Party's reporting by a team of international experts, will receive a lot of public attention unless they are somehow highlighted at an international event.Footnote2 Also, the review reports may not be written in a format easily accessible to the media and to the wider public.

This is where the GST could make a contribution: by publicly receiving, reviewing and appraising individual country reports in a format amenable for a wider public. However, the GST has a very narrow mandate (if at all) in this regard: Art. 14.1 postulates that the GST is supposed to assess collective progress only. Hence, Milkoreit and Haapala (Citation2017) argue that there is no scope for ‘naming and shaming’ within the GST. This seems correct in the sense that the ultimate outcome(s) of the GST need to summarize individual country data in order to draw global conclusions. The GST is not supposed to compare country performance, but, ideally, it would still support comparability. Conceptualizing the GST as a process, its initial phase merits particular attention in this regard: the GST process will require input from the Enhanced Transparency Framework and other ‘best available science’ sources to be received and reviewed. The question is, to what extent can this be done publicly? While this kind of public appraisal of country-specific information would arguably strengthen the efficacy of the PA, it is also likely to receive strong political contestation.

The GST is unprecedented in that it focuses exclusively on collective action (Milkoreit & Haapala, Citation2018). While individual countries will not be put into the spotlight in the official process, the GST could still create an echo chamber for the transparency framework that helps to attract the necessary public attention. If collective progress is on the political agenda at the global level, the natural next question at the national level would be to ask what each country contributed to the status quo (for a detailed discussion of pathways towards accountability see Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen et al., Citation2018).

2.3. Driving NDC ambition

As outlined in the introduction, the current level of ambition still falls short of what is necessary (UNFCCC, Citation2016a). To make up for this, Parties’ next round of NDCs will at least have to comply with Art. 4.3 of the PA in that they ‘will represent a progression beyond the Party's then current nationally determined contribution and reflect its highest possible ambition’ (UNFCCC, Citation2016c, Art. 4.3).

Firstly, the GST could determine benchmarks that may help to operationalize what is meant by ‘highest possible ambition’ and what constitutes a progression beyond the current NDC. Such benchmarks would make it easier to reward ambitious action exceeding the benchmark and at the same time to identify lack of ambition. That way, the GST could help raise the political costs or benefits of (in-)action.

One benchmark would be to determine what kind of level of ambition is required in the upcoming NDC period, taking into account the achievements and shortfalls of the current NDC period. Modelling studies have already explored the necessary increase in global ambition levels for 2030 and 2035 given the current NDCs and, along with further analyses, should inform the first GST (see for example Luderer et al., Citation2018; Rogelj et al., Citation2016; Vandyck, Keramidas, Saveyn, Kitous, & Vrontisi, Citation2016). This could then serve as a yardstick against which to assess the newly proposed NDCs. It is not within the mandate of the GST to assess individual NDCs, but it could provide the means for others – including national policymakers and civil society organizations – to carry out such work.

Another useful benchmark would be to identify and showcase particularly ambitious NDCs or policies and measures taken to date. This would help to raise the bar of what is commonly perceived as ‘the highest level of ambition’. Covering a diverse portfolio of countries at different stages of development and a wide range of specific national circumstances would help to account for the latter part of Art. 4.3: the reference to equity and national circumstances.

This kind of benchmark leads us to another important contribution the GST could make in order to enhance the ambition of NDCs. Milkoreit and Haapala (Citation2017, p. 2) have proposed to ‘use the GST as a peer-learning platform for “how to do transformational change”’. This could be achieved if the GST were to identify synergies and transformative potentials to facilitate sustainable development in broader terms than just focussing on mitigation potentials. Parties may be motivated much more by positive development potentials and synergetic opportunities than by yet another call for urgency (also see Hale, Citation2018).

Milkoreit and Haapala (Citation2017, p. 9) further highlight that enhancing ambition could be achieved by creating a mechanism that relies on ‘pride and fame’ over ‘fear and shame’ to motivate Parties to implement their NDCs. To this end, they suggest inviting Parties to voluntarily subject themselves to international review, mirroring the modalities of the voluntary review of the UN High-Level Political Forum for Sustainable Development that assesses progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

2.4. Guidance and signal

There is yet another mechanism of change which the GST could support: Ideas and values shape the way we see the future and therefore transformational change requires a fundamental ‘mindshift’ (Göpel, Citation2016; also see Milkoreit, Citation2017). Change occurs when new collective ideas emerge associated with shifting cultural values and world views that guide everyday decision making (see Geels & Schot, Citation2010). Specifically, the GST can foster change by institutionalizing a global vision of a decarbonized and sustainable future. Through periodic goal setting and benchmarking the GST can drive normalization of ambitious climate action and shift expectations of stakeholders across all governance levels (Hale, Citation2018).

More specifically, the international relations literature increasingly recognizes that many international institutions, including the PA, assume a guidance and signal function that extends beyond the international level (Bodansky, Citation2016b; Falkner, Citation2016; Hermwille, Obergassel, Ott, & Beuermann, Citation2017; Morseletto, Biermann, & Pattberg, Citation2017). In the words of Oberthür et al. (Citation2017, p. 16), the adoption of strong collective goals and pathways to achieve those goals

signals the resolve of governments (or other members of international institutions) to pursue a certain course of action and hence indicates likely policy trajectories to business, investors and other actors operating at all levels of governance. As such, the signal and direction provided has the potential to help synchronise and align developments across levels of governance and across the boundaries of different countries.

Yet, for some sectors the signal provided seems much clearer than for others. For many sectors, a great deal of ambiguity remains of what the 1.5°C goal actually means. While the challenges are largely known for the power sector and the electrification of passenger transport, they remain relatively vague for example on emission intensive industries, agriculture and land-use including forestry (IPCC, Citation2018; Kuramochi et al., Citation2018).

In the light of this discussion, what is the role of the GST? First of all, the GST is an opportunity to reiterate and reinforce the signal already provided in Paris. More importantly, though, the GST could further develop and refine the existing signal including by ensuring consistency with other international Agendas like the SDGs and the New Urban Agenda. The IPCC special report on the 1.5°C goal outlines the paths to 1.5°C in the context of sustainable development in more detail and further highlights the risks of exceeding the Paris temperature limits. The GST could and should process this new information and help infuse it into the NDC revision process. More concretely, for mitigation, it would be particularly helpful if the GST collated and institutionalized sectoral visions that spell out more clearly sector-specific transformation challenges and consider sector interdependencies. It could assess and/or endorse sectoral visions (e.g. developed by sectoral transnational governance initiatives) and assess barriers and facilitators (e.g. financial and technological support) towards the realization of these visions (Rayner et al., Citation2018). Also, the IPCC in its 6th and subsequent assessment reports could provide the scientific basis for this.

Refining the signal provided from the PA would not only help guide the next round of NDCs, but could also serve as an updated reference point for all kinds of governance initiatives (including non-state and subnational actors). It would provide legitimation and orientation for transnational governance initiatives and thus help ‘orchestrate’ the groundswell of climate action (Hale & Roger, Citation2014). The PA was able to raise global recognition and awareness of climate change throughout all layers of society. The ideal GST would garner this attention and tune it to the fact that the climate change problem remains unresolved.

3. Operationalizing the functions: what is needed to exercise the functions

Whether or not the GST will be able to fulfil its functions will crucially depend on how it is designed. In this section, we discuss which process- and information-related conditions are needed to fully enable the catalytic effect of the GST, and consider the extent to which the adopted modalities of the GST meet those conditions.

3.1. Process-related preconditions

In order to fulfil its governance functions, the GST needs to be understood as a process rather than an event or a specific outcome (also see Milkoreit & Haapala, Citation2018). This is also reflected in the Paris ‘rulebook’. The modalities of the GST foresee three phases for it: information collection and preparation, technical assessment, and a political phase of the ‘consideration of outputs’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018a). The GST will commence 1.5–2 years (depending on the timing of the publication of the 6th Assessment Report of the IPCC) before the final consideration of outputs that will take place during COP29 in 2023. In this section we will derive key process-related preconditions for the latter two phases, namely, the technical assessment and the consideration of outputs.

3.1.1. Technical assessment

The first step of the GST is to gather and process relevant data and information, particularly information provided from the transparency framework. Ideally, this would happen in the form of a public appraisal of inputs, particularly the transparency reports and communications from Parties, and including the possibility for public consultations/feedback on those inputs. This process could further be facilitated by a technical synthesis report by the Secretariat that systematically collates the results of the technical expert reviews by country, focussing on the progress in implementing and achieving the NDC. It may also include the identified deficits and proposed ‘areas of improvement’ as well as insights from the facilitative, multilateral consideration of progress which is supposed to conclude the review process (UNFCCC, Citation2016b, Art. 13.11-12). The modalities of the GST as adopted in Katowice provide such a mandate. In fact, they request the Secretariat to prepare four synthesis reports on the state of emissions, the progress of NDC implementation, the state of adaptation efforts, and the state of financial flows.

As discussed above, singling out individual countries will not be possible under the GST. Nevertheless, the accountability function of the GST could be strengthened with the inclusion of an anonymised ‘transcript of grades’. This could include statements like ‘X countries representing Y per cent of global emissions show significant implementation deficits and are unlikely to meet their targets unless implementation is improved’. The report could be the basis of discussions and serve as a means to hold countries accountable. It would be accessible to various stakeholders and could be leveraged to create political pressure on the national level. How these reports will be considered in the technical assessment is however not currently specified in the modalities for the GST.

Complementary to this suggested public appraisal of inputs, a more facilitative and issue specific workstream would be required to enable information sharing and ‘transformational learning’ (Milkoreit & Haapala, Citation2017). The GST modalities structure its work according to three ‘thematic areas’ – mitigation, adaptation, and means of implementation and support. Notably and after substantial controversy, Parties agreed to open the process to also consider loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change. On each of these themes, technical dialogues will be held by means of ‘in-session round tables, workshops or other activities’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018a, para. 6).

This creates ample leeway for the Chairs of the subsidiary bodies – the GST will be supported by a joint contact group of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) and the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) – and the assigned co-facilitators of that contact group to provide a meaningful structure for the technical assessment. The facilitators have the responsibility to make sure that the exchange is focused and oriented towards actual positive learning. It must not result in an endless repetition of previously stated commitments nor must it become a forum for greenwashing lack of ambition, demonstrating effective shirking of responsibility, or pretence of ambition.

Ideally, this would take the form of structured dialogues of experts, which should focus on relatively concrete (sectoral) transformation challenges in order to fully exploit their potential. Input from non-state and subnational initiatives could be particularly valuable here and the modalities of the GST enable this stakeholder engagement. Non-Party stakeholder participation was one of the more contentious issues in Katowice. But, ultimately, Parties decided that the GST will be ‘conducted in a transparent manner and with the participation of non-Party stakeholders’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018a, para. 6). Opportunities for participation include provision of written submissions as input to the GST and engagement in the technical dialogues outlined above. Somewhat worrying is another formulation: the decision specifies that the inputs will be made ‘fully accessible by Parties’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018a, para. 10 and 21, emphasis added). While this does not explicitly exclude that the inputs will be publicly available, the phrase caused some concern among observers that the GST could end up being a rather secretive endeavour.

How could these technical dialogues be structured? Huang (Citation2018) draws parallels between the GST and the voluntary national reviews under the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals. Countries that have made good progress could volunteer to undergo an in-depth review in order to promote their success stories even further. Milkoreit and Haapala (Citation2018) suggest that the first periodic review (2013–2015) of the adequacy of, and overall progress toward, achieving the long-term global goal could serve as a valuable precedent, in particular the Structured Expert Dialogue that was conducted under this review. Alternatively, the dialogues could be modelled, for example, after the existing Technical Examination Processes (TEPs) held under the joint auspices of the UNFCCC's Subsidiary Bodies for the topics of mitigation and adaptation, or the Technical and Economic Assessment Panel (TEAP) under the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Hermwille, Citation2018). The latter has been particularly successful in translating technical work at the expert level into a gradual increase of ambition at the political level (Andersen & Sarma, Citation2002; Gonzalez, Taddonio, & Sherman, Citation2015). Finally, the Talanoa Dialogue that concluded at COP24 in Katowice was seen as a precedent for the GST. It solicited a large amount of input from all kinds of stakeholders. The process produced a synthesis report of all the inputs received and discussions held over the course of the year (UNFCCC, Citation2018c) and resulted in the ‘Talanoa Call for Action’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018b). However, that call did not trigger immediate political response in terms of more ambitious targets. Within the negotiations it lacked a high profile and given these limitations it seems doubtful whether it can effectively stimulate further action (Obergassel et al., Citation2019).

To ensure engagement and support of all Parties, the technical dialogues will need to consider equity issues, both in their design and in the content considered. In terms of process, the dialogues should be scheduled in a manner that is inclusive, accessible, and manageable to all Parties, and broad in the scope of issues considered. At the same time, the technical assessment should also more directly address equity and the extent to which Parties, or groups of Parties, are falling short on their equitable contributions (Climate Action Tracker, Citation2019; Holz, Kartha, & Athanasiou, Citation2018; Pan, den Elzen, Höhne, Teng, & Wang, Citation2017; Robiou du Pont et al., Citation2016). A key challenge here is that equity issues are inherently differentiated, which clashes with the mandate of the GST to assess collective progress. The aforementioned transcript of grades approach could be used with a focus on metrics of a more equitable world, such as access to energy, shifts in per capita emissions, or number of countries with contributions to climate finance. Alternatively, assessing equity by grouping countries according to NDC type or socioeconomic circumstances could be explored.

The GST should also take into account, and relate itself to, other relevant international agendas endorsing sectoral transformation pathways, particularly the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development with its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as UN Habitat's New Urban Agenda. The goals of any single Agenda can only be achieved in accordance with the other Agendas (Obergassel, Mersmann, & Wang-Helmreich, Citation2017; von Stechow et al., Citation2016). Looking at context beyond climate change mitigation will not only help to create more consistent narratives, it also increases the likelihood that the results of the GST are actually taken up on national political agendas. The modalities of the GST provide at least one inroad to do so: ‘Relevant reports from United Nations agencies and other international organizations, that should be supportive of the UNFCCC process’ are explicitly listed as one of the information sources to be considered (UNFCCC, Citation2018a, para. 37f).

Finally, a key procedural requirement for the technical phase of the GST is adequate timing. The inputs from the Enhanced Transparency Framework, such as the data and information from the technical reviews, need to be prepared and published at an appropriate time. Likewise, the results of the technical phase need to duly feed into the political phase of the GST and the political phase must be concluded in a timely manner to have an effect on national political agendas regarding the development of subsequent NDCs. At least for the first GST, this requirement will not be met. The provisions of the Enhanced Transparency Framework will only be applied as of 2024 (cf. Obergassel et al., Citation2019). The first GST, therefore, will have to rely on the more limited information provided in the more limited previous transparency framework, namely National Communications, Biennial Reports and Biennial Update Reports. For subsequent GSTs the timing as determined by the Paris Rulebook will meet the requirements.

3.1.2. Political phase: consideration of outputs

Apart from the adequate timing, two other procedural aspects are particularly important for the GST to succeed. The first aspect relates to the pacemaker function. Metaphorically speaking, the impulses from the GST process as a pacemaker must be strong enough to effectively stimulate national and subnational governance levels. The political weight of the suggested ‘public appraisal of inputs’ could be maximized if the corresponding reports and stakeholder comments were formally ‘acknowledged’ or ‘taken note of’ through a high-level endorsement as part of the political phase. This could generate the level of public attention required to impact on national political agendas. The modalities foresee high-level events for the conclusion of the GST, which would identify good practices and opportunities for enhancing action. The modalities also state that the events could provide a summary of key political messages and recommendations. However, they leave open the question of whether these events would result in a formal COP decision or a political declaration with a lesser legal footing (UNFCCC, Citation2018a, para. 34).

Finally, the political phase of the GST needs to include a renewed political commitment. Parties need to reaffirm that they still honour the PA and its goals and demonstrate their continued resolve to act upon them. Doing so will not only raise the stakes in terms of the reputational repercussions of non-compliance at the international level (Simmons, Citation1998). It will also enable stakeholders to hold their respective governments accountable at the national level, in the event that they do not fully implement or achieve their NDC. Periodically expressing collective allegiance to the Paris Agreement may help to maintain support for it, and make it more costly for policymakers to (silentlyFootnote3) abandon climate ambition.

3.2. Information-related conditions for an ideal Global Stocktake

We now turn to the information-related conditions for an ideal GST that enable it to fulfil its functions. In the following we describe what kind of information inputs would be necessary for a successful implementation of the process.

3.2.1. Setting benchmarks

Firstly, information inputs to the GST need to set benchmarks for the global mitigation progress required to meet the well below 2°C or 1.5°C target. Benchmarks are not only required to set overall collective goals, they also describe policy trajectories to reach them and provide guidance and signalling on necessary political action to individual governments, as well as subnational and non-state actors. The information provided should allow the necessary level of global ambition to be broken down to the national level and enable comparability of ambition between subsequent NDCs of individual countries. Without such information, it would be impossible to assess the ambition of countries’ NDCs against the necessary level of mitigation action to achieve the 1.5°C target. Meaningful benchmarks are thus a precondition for enhancing the ambition of future NDCs and for providing orientation and guidance to countries regarding pathways to reach collective goals and implement transformation strategies. To fulfil that purpose, sector-specific information is needed. The IPCC plays a crucial role in this regard as it is the globally most prominent and legitimate institution synthesizing and providing such information. Benchmarks that are differentiated at the regional or national level are needed to reflect national circumstances so that they are both relevant and take into account equity considerations.

3.2.2. Transparent, high-quality reporting on the state of emissions and the level of transformation

Information sources that are used as inputs to the GST need to be able to transparently quantify the emission reductions implied in countries’ NDCs as well as clearly indicate the current progress made by countries in reducing their emissions to date and working towards their future mitigation targets. To this end, the information reported in countries’ GHG inventories is particularly important. To ensure the necessary data quality, information reported on GHG emissions needs to be transparent, accurate, complete, consistent, and comparable (TACCC principles, see IPCC, Citation2006). The PA explicitly refers to this standard by requiring Parties to ‘promote environmental integrity, transparency, accuracy, completeness, comparability and consistency, and ensure the avoidance of double counting … ’ (UNFCCC, Citation2016b, Art. 14.3). To make this possible, Parties shall provide the information necessary for clarity, transparency and understanding of their NDCs (UNFCCC, Citation2016b, Art. 4.8). However, the diverse nature of bottom-up defined NDCs is a challenge and creates the need for differentiated information requirements for different types of NDCs (for a discussion of information requirements for NDCs see Briner & Moarif, Citation2016; Herold, Siemons, & Herrmann, Citation2018; Schneider et al., Citation2017).

Moreover, information related to progress made in transitioning to a low-carbon economy should be shared among countries in an ideal GST. What are the priorities/visions of the country towards a low-carbon economy? What are the perceived key challenges/barriers for progress and what strategies are in place to address them? And how could the transformative progress be assessed (see ICAT, Citation2017)?

In summary, information on the state of current emissions, level of progress achieved, and future directions are crucial in order to fulfil several functions of the GST. Such information is necessary to assess progress made at the country level and thus to compare overall progress to the necessary mitigation benchmarks in order to achieve the targets of the PA. Furthermore, it is necessary to ensure accountability of countries, build trust among Parties and shed light on areas where ambition needs to be enhanced.

3.2.3. Political relevance

Lastly, an ideal GST requires information that is able to inform national policy-making and to trigger national enhancement of ambition. The GST needs to provide guidance and orientation to countries. This can best be achieved by showcasing solution-oriented outcomes, opportunities and best practices, instead of focusing on gaps in mitigation action alone. The following conditions can help to strengthen the political relevance of the GST and its outcome at the national level:

Information used stems from a source with credibility/legitimacy;

Sector-specific information regarding challenges and mitigation opportunities is provided on a country-level as well as in global/aggregate reports;

Good practice examples can be identified (e.g. in a format similar to the TEPs – see section 3.1.1 above);

Co-benefits between mitigation and adaptation actions, as well as with respect to other dimensions of sustainable development, are identified;

All of the above information is reflective of the specific national context and circumstances for which recommendations are being developed. That is, the GST should not promote a ‘one size fits all’ solution but a portfolio of options that are suitable for different circumstances and are provided from multiple sources (and voices).

4. Conclusions

What makes an ideal GST? An ideal GST is one that facilitates transformational change. In this article we have outlined four distinct functions of the GST addressing different mechanisms of driving change. We believe that all four of these functions need to be exploited to maximize the catalytic effect of the GST.

For each of the four functions, we have identified a number of key conditions for the GST to fully exploit its potential as a motor of transformation. , below, summarizes the findings.

Table 1. Synthesis of preconditions for an ideal Global Stocktake.

In a nutshell, an effective GST is a process, not an isolated event, and this process needs to meet certain conditions:

It needs to be scheduled in a timely manner, so that the informational input is ready when needed and the political output comes in time to be most effective;

It needs to publicly appraise the inputs, particularly the national reports from the Transparency Framework in order to maximize a disciplining effect on Parties;

Complementarily, it requires a facilitative format in which good practice can be shared, highlighted and processed into relevant country-specific recommendations;

And it needs to feature a high-level political event in order to amplify the messages towards influencing national policy agendas and as a renewed political commitment that Parties still honour the PA and its goals.

To meet these conditions, specific information requirements need to be complied with in order to successfully implement the GST process. The information needs to enable benchmark setting, it needs to be transparent and reliable, and it needs to be politically relevant to resonate with national (and subnational) political discourses.

The modalities as adopted in Katowice provide a solid foundation for a successful GST, but by no means is this success guaranteed. In the worst case, the GST will die away as yet another unheard call for urgency. A lot will depend on the Chairs of the subsidiary bodies, the facilitators of the joint contact group to support the GST and the UNFCCC Secretariat who will play a key role in shaping the actual stocktake. The theoretical foundations as well as the above summarized recommendations may serve as source of inspiration.

However, we acknowledge the limitations of the official UNFCCC process. Some of the elements outlined above may not be possible to achieve within the multilateral negotiations. This is particularly true for the accountability function. The mandate of the GST is too narrow to allow for effective naming and shaming. What is more, the recent increase of nationalist populist propaganda and the apparent inability of large parts of the global public to deal with lies and falsehoods (‘fake news’) further seem to limit this. Shameless policy makers seem to be immune to naming and shaming (Appiah, Citation2010).

Moreover, it is hard to see how the official GST will provide country specific recommendations. In fact, para 14 of the modalities specifies that ‘the outputs of the global stocktake should […], have no individual Party focus, and include non-policy prescriptive consideration of collective progress’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018a, para. 14).

And finally, the UNFCCC has hardly any track record of assessing progress or making any specific recommendations along sectoral lines. This, however, would be useful to identify the decarbonization challenges that must be resolved to accelerate the transformation (see Rayner et al., Citation2018).

To make up for these deficiencies, a concerted effort from academia and civil society – an independent GST – would be in order (Anderson, Citation2018). This effort could piggy-back on the public attention attracted by the official GST. It could translate its aggregate findings into country specific messages and recommendations and fill in some of the information gaps left by the official process due to the narrow mandate provided in the PA as well as the limitations of the political realities of UNFCCC negotiations.

Building on the four functions outlined in this article, we believe that the GST can become an engine of transformation despite certain limitations in the official UNFCCC process. It can help foster a constructive debate on ambitious climate action and (re)align national political agendas for the subsequent NDCs with the goals of the PA. And this is necessary so that the PA can realize its full potential.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Lukas Hermwille http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9811-2769

Louise Jeffery http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3584-8111

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Unless otherwise specified, mentions of numbered Articles (e.g. ‘Art. 4.2’) always refer to the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, Citation2016b).

2. In the past, for example the Multilateral Assessment Process under the Assessment and Review procedure for Annex I countries under the SBI (review process for Biennial Reports submitted by Annex I countries) has received rather little public engagement or attention and no higher-level event or measures to enhance publicity have been undertaken.

3. Since achieving NDC targets is not legally binding, Parties do not need to formally withdraw if they no longer wish to implement those targets. Instead, they may simply disregard the Paris Agreement, at least until the next NDC cycle.

References

- Andersen, S. O., & Sarma, K. M. (2002). Protecting the ozone layer. The United Nations history. London: Earthscan.

- Anderson, J. (2018, December 3). The independent Global Stocktake will improve Paris Agreement implementation. Retrieved from ClimateWorks Foundation website: https://www.climateworks.org/blog/the-independent-global-stocktake-will-improve-paris-agreement-implementation/

- Appiah, K. A. (2010). The honor code: How moral revolutions happen. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Bodansky, D. (2016a). The legal character of the Paris Agreement. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law, 25(2), 142–150. doi: 10.1111/reel.12154

- Bodansky, D. (2016b). The Paris climate change agreement: A new hope? The American Journal of International Law, 110(2), 288–319. doi: 10.5305/amerjintelaw.110.2.0288

- Briner, G., & Moarif, S. (2016). Enhancing transparency of climate change mitigation under the Paris Agreement: Lessons from experience (Paper No. No. 2016(4)). Retrieved from OECD CCXG website: https://www.oecd.org/environment/cc/Enhancing-transparency-climate-change-mitigation-V2.pdf

- Chan, S., Boran, I., van Asselt, H., Iacobuta, G., Niles, N., Rietig, K., … Wambugu, G. (2019). Promises and risks of nonstate action in climate and sustainability governance. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 10(e572), 1–8. doi: 10.1002/wcc.572

- Climate Action Tracker. (2019). Country assessments. Retrieved from Climate Analytics, Ecofys and NewClimate Institute website: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/

- Depledge, J. (2016). The Paris Agreement: A significant landmark on the road to a climatically safe world. Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies, 04(01), 1650011. doi: 10.1142/S2345748116500111

- Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. International Affairs, 92(5), 1107–1125. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.12708

- Friedrich, J. (2017). Global Stocktake (Article 14). In D. Klein, M. P. Carazo, M. Doelle, J. Bulmer, & A. Higham (Eds.), The Paris Agreement on climate change: Analysis and commentary (pp. 319–337). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2010). The dynamics of transitions: A socio-technical perspective. In J. Grin, J. Rotmans, & J. Schot (Eds.), Transitions to sustainable development – New directions in the study of long term transformative change (pp. 11–104). New York: Routledge.

- Gonzalez, M., Taddonio, K., & Sherman, N. J. (2015). The Montreal Protocol: How today’s successes offer a pathway to the future. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 5(2), 122–129. doi:10.1007/s13412-014-0208-6

- Göpel, M. (2016). The great mindshift. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Hale, T. (2018). Catalytic cooperation (BSG Working Paper No. 2018/026). Retrieved from Blavatnik School of Government, Univeristy of Oxford website: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/BSG-WP-2018-026.pdf

- Hale, T., & Roger, C. (2014). Orchestration and transnational climate governance. The Review of International Organizations, 9(1), 59–82. doi: 10.1007/s11558-013-9174-0

- Hermwille, L. (2016). Climate change as a transformation challenge – A new climate policy paradigm? GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 25(1), 19–22. doi: 10.14512/gaia.25.1.6

- Hermwille, L. (2018). Making initiatives resonate: How can non-state initiatives advance national contributions under the UNFCCC? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18(3), 447–466. doi: 10.1007/s10784-018-9398-9

- Hermwille, L., Obergassel, W., Ott, H. E., & Beuermann, C. (2017). UNFCCC before and after Paris – What’s necessary for an effective climate regime? Climate Policy, 17(2), 150–170. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2015.1115231

- Herold, A., Siemons, A., & Herrmann, L. (2018). Is it possible to track progress of the submitted nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement? Retrieved from Öko-Institut website: https://www.oeko.de/publikationen/p-details/is-it-possible-to-track-progress-of-the-submitted-nationally-determined-contributions-under-the-pari/

- Holz, C., Kartha, S., & Athanasiou, T. (2018). Fairly sharing 1.5: National fair shares of a 1.5 °C-compliant global mitigation effort. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18(1), 117–134. doi: 10.1007/s10784-017-9371-z

- Holz, C., & Ngwadla, X. (2016). The Global Stocktake under the Paris Agreement – Opportunities and challenges. Retrieved from European Capacity Building Initiative (ecbi) website: http://www.eurocapacity.org/downloads/GST_2016[1].pdf

- Huang, J. (2018). What can the Paris Agreement’s Global Stocktake learn from the sustainable development goals? Carbon & Climate Law Review, 12(3), 218–228. doi: 10.21552/cclr/2018/3/8

- ICAT. (2017). Transformational change guidance, first draft. Retrieved from Initiative for Climate Action Transparency (ICAT) website: http://www.climateactiontransparency.org/icat-guidance/transformational-change/

- IPCC. (2006). 2006 IPCC guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Retrieved from Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change website: http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/index.html

- IPCC. (2014). Summary for policy makers. In Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working group III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C – An IPCC special report. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

- Jacoby, H. D., Chen, Y.-H. H., & Flannery, B. P. (2017). Informing transparency in the Paris Agreement: The role of economic models. Climate Policy, 17(7), 873–890. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2017.1357528

- Jann, W., Wegrich, K., Fischer, F., Miller, G., & Mara, S. (2007). Theories of the policy cycle. In Public policy and public administration: Vol. 125. Handbook of public policy analysis: Theory, politics, and methods (pp. 43–62). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press | Taylor & Francis.

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I., Groff, M., Tamás, P. A., Dahl, A. L., Harder, M., & Hassall, G. (2018). Entry into force and then? The Paris agreement and state accountability. Climate Policy, 18(5), 593–599. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2017.1331904

- Kuramochi, T., Höhne, N., Schaeffer, M., Cantzler, J., Hare, B., Deng, Y., … Blok, K. (2018). Ten key short-term sectoral benchmarks to limit warming to 1.5°C. Climate Policy, 18(3), 287–305. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2017.1397495

- Luderer, G., Vrontisi, Z., Bertram, C., Edelenbosch, O. Y., Pietzcker, R. C., Rogelj, J., … Kriegler, E. (2018). Residual fossil CO 2 emissions in 1.5–2 °C pathways. Nature Climate Change, 8(7), 626–633. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0198-6

- Milkoreit, M. (2017). Imaginary politics: Climate change and making the future. Elem Sci Anth, 5(0), 62. doi: 10.1525/elementa.249

- Milkoreit, M., & Haapala, K. (2017). Designing the Global Stocktake: A global governance innovation [Working Paper]. Retrieved from C2ES – Center for Climat and Energy Solutions website: https://www.c2es.org/site/assets/uploads/2017/11/designing-the-global-stocktake-a-global-governance-innovation.pdf

- Milkoreit, M., & Haapala, K. (2018). The Global Stocktake: Design lessons for a new review and ambition mechanism in the international climate regime. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics. doi: 10.1007/s10784-018-9425-x

- Morseletto, P., Biermann, F., & Pattberg, P. (2017). Governing by targets: Reductio ad unum and evolution of the two-degree climate target. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(5), 655–676. doi: 10.1007/s10784-016-9336-7

- Müller, B., & Ngwadla, X. (2016). The Paris ambition mechanism – Review and communication cycles. Retrieved from Oxford Climate Policy, European Capacity Building Initiative website: http://www.eurocapacity.org/downloads/Ambition_Mechanism_Options_Final.pdf

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Northrop, E., Dagnet, Y., Höhne, N., Thwaites, J., & Mogelgaard, K. (2018). Achieving the ambition of Paris: Designing the Global Stocktake. Retrieved from World Resources Institute (WRI) website: http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/achieving-ambition-paris-designing-global-stockade.pdf

- Obergassel, W., Arens, C., Hermwille, L., Kreibich, N., Mersmann, F., Ott, H. E., & Wang-Helmreich, H. (2015). Phoenix from the ashes: An analysis of the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – Part I. Environmental Law and Management, 27, 243–262.

- Obergassel, W., Arens, C., Hermwille, L., Kreibich, N., Mersmann, F., Ott, H. E., & Wang-Helmreich, H. (2016). Phoenix from the ashes: An analysis of the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – Part II. Environmental Law and Management, 28, 3–12.

- Obergassel, W., Arens, C., Hermwille, L., Ott, H. E., Kreibich, N., & Wang-Helmreich, H. (2019). Paris Agreement: Ship moves out of the Drydock. Retrieved from Wuppertal Inst. for Climate, Environment and Energy website: https://wupperinst.org/en/a/wi/a/s/ad/4643/

- Obergassel, W., Mersmann, F., & Wang-Helmreich, H. (2017). Two for one: Integrating the sustainable development agenda with international climate policy. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 26(3), 249–253. doi: 10.14512/gaia.26.3.8

- Oberthür, S., & Bodle, R. (2016). Legal form and nature of the Paris outcome. Climate Law, 6(1–2), 40–57. doi: 10.1163/18786561-00601003

- Oberthür, S., Hermwille, L., Khandekar, G., Obergassel, W., Rayner, T., Wyns, T., … Melkie, M. (2017). Key concepts, core challenges and governance functions of international climate governance (Deliverable No. 4.1). Retrieved from COP21 RIPPLES Project (Horizon2020) website: https://www.cop21ripples.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Deliverable-4.1-Ripples-Final2.pdf

- Pan, X., den Elzen, M., Höhne, N., Teng, F., & Wang, L. (2017). Exploring fair and ambitious mitigation contributions under the Paris Agreement goals. Environmental Science & Policy, 74, 49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2017.04.020

- Rajamani, L. (2016). The 2015 Paris Agreement: Interplay between hard, soft and non-obligations. Journal of Environmental Law, 28(2), 337–358. doi: 10.1093/jel/eqw015

- Rayner, T., Oberthür, S., Hermwille, L., Khandekar, G., Obergassel, W., Kretschmer, B., … Zamarioli, L. (2018). Evaluating the adequacy of the outcome of COP21 in the context of the development of the broader international climate regime complex (Deliverable No. 4.2). Retrieved from COP21 RIPPLES Project (Horizon2020) website: https://www.cop21ripples.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/RIPPLES_D4.2-Final.pdf

- Robiou du Pont, Y., Jeffery, M. L., Gütschow, J., Rogelj, J., Christoff, P., & Meinshausen, M. (2016). Equitable mitigation to achieve the Paris Agreement goals. Nature Climate Change. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3186

- Rogelj, J., den Elzen, M., Höhne, N., Fransen, T., Fekete, H., Winkler, H., … Meinshausen, M. (2016). Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature, 534(7609), 631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature18307

- Schneider, L., Füssler, J., La Hoz-Theuer, S., Kohli, A., Graichen, J., Healy, S., & Broekhoff, D. (2017). Environmental integrity under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement [Discussion paper]. Retrieved from DEHSt website: https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/project-mechanisms/Discussion-Paper_Environmental_integrity.pdf

- Simmons, B. A. (1998). Compliance with international agreements. Annual Review of Political Science, 1(1), 75–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.75

- Tompkins, E. L., Vincent, K., Nicholls, R. J., & Suckall, N. (2018). Documenting the state of adaptation for the Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(5), e545. doi: 10.1002/wcc.545

- UNFCCC. (2016a). Aggregate effect of the intended nationally determined contributions: An update [Document FCCC/CP/2016/2]. Retrieved from United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change website: http://unfccc.int/focus/indc_portal/items/9240.php

- UNFCCC. (2016b). Paris Agreement. Retrieved from United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) website: http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/paris_nov_2015/application/pdf/paris_agreement_english_pdf

- UNFCCC. (2016c). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015 (No. FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1). Retrieved from United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) website: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2018a). Decision -/CMA.1, matters relating to Article 14 of the Paris Agreement and paragraphs 99–101 of decision 1/CP.21 – Advance unedited version. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/documents/187714

- UNFCCC. (2018b). Talanoa call for action. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/news/join-the-talanoa-call-for-action

- UNFCCC. (2018c). Talanoa dialogue for climate action – Synthesis of the preparatory phase. Retrieved from https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/9fc76f74-a749-4eec-9a06-5907e013dbc9/downloads/1cu4u95lo_238771.pdf

- van Asselt, H. (2016). International climate change law in a bottom-up world. Questions of International Law, 26, 5–15.

- van Asselt, H., Pauw, P., & Sælen, H. (2015). Assessment and review under a 2015 Climate Change Agreement. Retrieved from Nordic Council of Ministers website: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-3855

- Vandyck, T., Keramidas, K., Saveyn, B., Kitous, A., & Vrontisi, Z. (2016). A Global Stocktake of the Paris pledges: Implications for energy systems and economy. Global Environmental Change, 41, 46–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.08.006

- von Stechow, C., Minx, J. C., Riahi, K., Jewell, J., McCollum, D. L., Callaghan, M. W., … Baiocchi, G. (2016). 2 °C and SDGs: United they stand, divided they fall? Environmental Research Letters, 11(3), 034022. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/3/034022

- Winkler, H., Mantlana, B., & Letete, T. (2017). Transparency of action and support in the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 17(7), 853–872. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2017.1302918