ABSTRACT

Populism and its rhetoric are on the rise. Political actors across different ideological camps and parties are employing dispositional blame attribution, emphasizing the non-responsiveness of ‘corrupt elites’ to the needs of ‘good and honest’ people. In this paper, we focus on one specific and common area of blame attribution; climate change. In particular, in the United States, a central player in global climate governance, climate change is a very contested issue. The successes of populist candidates in both major US parties suggest that populism could affect citizen support for climate mitigation policies. The often abstract, elite-driven, and technical nature of climate change makes this issue an ideal target for populist critique. Our paper offers an empirical assessment of this claim. First, we test whether populism truly has an independent effect on people’s climate attitudes. Second, we assess to what extent frames about elite responsiveness are important heuristics for individuals in their formation of preferences concerning climate policies. To accomplish this goal, we fielded representative US surveys (N = 3000) and collected both observational and experimental data. Results suggest that populist attitudes enhance the effects of partisanship, rather than creating an independent, orthogonal dimension. Populist Democrats support climate policies more than non-populist Democrats do, whereas populist Republicans oppose such policies more than non-populist Republicans do. Additionally, while our experimental results indicate that populist treatments blaming elites for being non-responsive to citizens’ preferences do not affect policy support, we also find that reassuring individuals that political elites care about citizens’ needs and preferences in relation to climate policy increases support for the latter.

Key policy insights

Citizens’ support is central for implementing ambitious climate policies.

Populist attitudes amplify partisanship effects on public opinion about climate policy.

Populist discourse per se is not an obstacle to adopting ambitious climate policy in the US.

Political entrepreneurs can foster support for climate policies by emphasizing elite responsiveness to citizens’ needs and preferences.

Populist attacks on established elites are unlikely to derail support for climate policy.

Populism and its rhetoric are on the rise globally (de la Torre, Citation2015). Political actors across different ideological camps and parties are employing dispositional blame attribution, emphasizing the non-responsiveness of ‘corrupt elites’ to the needs of ‘good and honest’ people (Busby et al., Citation2019). However, a specific context is typically needed for populist beliefs to become applicable and change citizens’ policy-related attitudes. In this paper, we focus on a specific context that has recently gained considerable momentum on political agendas and attracted attention from populist parties around the world, in particular the United States: climate change. Recent success of Republican and Democratic populist candidates (Green & White, Citation2019; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016) suggest that populism could affect citizen support for climate mitigation policies, particularly since climate change is a contested issue in the US. Specifically, we seek to add to the literature by investigating the effects of citizens’ populist beliefs and experimentally induced populist rhetoric on their attitudes towards climate mitigation policies.

Climate change and associated environmental degradation pose substantial threats to societies worldwide and are challenging for policy-makers and citizens alike. Coping with these problems requires far-reaching and thus potentially costly adaptation and mitigation policies. Especially in Western (liberal) democracies, public opinion and support for such policies are important determinants of policy action or inaction (Anderson et al., Citation2017; Page & Shapiro, Citation1983; Wlezien, Citation1995). Substantial research has shown that partisanship and political ideology are important explanations of citizens’ attitudes towards climate change – particularly in the US (Dunlap et al., Citation2016; Dunlap & McCright, Citation2008; McCright & Dunlap, Citation2011; Neumayer, Citation2004).

While we observe substantially more polarization and party sorting in the US than other countries (Fiorina et al., Citation2008; Fiorina & Abrams, Citation2008) especially around the climate change issue (Layman et al., Citation2006), there are alternative explanations as to why persistent climate scepticism and a lack of support for related policies may be observed in the US. In times of rising populism, the issue of climate change has been subject to considerable politicization by populist actors in both the Democratic and Republican Parties (Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016). Nevertheless, the question whether populism and dispositional blame attribution truly have an independent effect on people’s climate attitudes that is additional to partisanship remains unanswered.

Political entrepreneurs who engage in populist discourse usually evoke a moral divide between two homogeneous and antagonistic groups: ‘good people’ and an ‘evil elite’ (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018). With such discourse, populists accuse the political elite of a lack of responsiveness to citizens’ demands and claim to be the only true representatives of the people (Caramani, Citation2017). This type of rhetoric is a clear example of dispositional blame attribution (Busby et al., Citation2019). For instance, during and after the latest US presidential election, Donald Trump advocated strong scepticism about human-induced climate change. Trump regularly pointed to a lack of government responsiveness to citizens’ concerns about the consequences of government interventions associated with Barack Obama's climate policy.Footnote1 At the same time, the Democratic Senator Bernie Sanders attacked economic and political elites on their influence on climate policy, tapping into text-book populist rhetoric.Footnote2 Therefore, while the consequences of such populist discourse remain unclear, our interests lie in identifying whether populism and associated claims of inadequate responsiveness, beyond other political factors such as party identification, affect citizen support for climate change policy. This is an especially important question in the US media ecosystem in which many citizens are increasingly confronted with one-sided political messages. Eventually, populism might amplify the already existing polarization of climate attitudes (Dunlap et al., Citation2016; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2018), particularly in times of filter bubbles and all their implications for news consumption and ideological polarization, along with consequences for political discourse (Flaxman et al., Citation2016).

Given their largely technical, abstract, and elite-driven nature, climate politics are an ideal and vulnerable target for populists (Huber, Citation2020). Populist individuals are more likely to oppose the central actors involved in top-down climate policy (namely, the political elites that adopt climate policies) and are likely to reject climate-change-related mitigation policies proposed by the same actors. Moreover, policy frames that highlight a perceived lack of responsiveness in climate communication and prompt citizens to consider the climate problem in dispositional terms might affect individuals’ willingness to support climate policies. Information about responsiveness is an important heuristic in terms of citizens’ willingness to delegate decisions in this issue area. In other words, if citizens receive information that the elite is unresponsive to their needs and preferences, they are less likely to support policies that are technical and abstract; that is, policies related to issue areas in which citizens often delegate responsibilities to elites due to a substantive lack of issue expertise. In an attempt to foster public support for climate policies, political elites could also assure citizens of their responsiveness to, and awareness of, peoples’ needs and preferences. In this sense, political elites may use the very same mechanisms as are used in populist rhetoric to reduce blame attribution.

Aside from in the US, populism and elite responsiveness could potentially be factors that shape citizens’ climate attitudes across different countries. For example, the case of the ‘yellow vests’ movement (Mouvement des gilets jaunes) in France suggests that responsiveness by political parties is being demanded by certain segments of society. Rather than opposing taxes on fossil fuels to limit climate change per se, members of the movement claim that policymakers do not understand their living conditions and political needs and no longer represent ‘the people’. This antagonism between a good public and an evil elite represents a deeply populist claim (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018).

It is particularly hard to test whether populism and dispositional blame attribution in the US have an independent effect on policy attitudes in the context of climate change given that partisanship is a particularly important moderator of climate attitudes in that country. If we are able to find a truly independent effect of populism and dispositional blame attribution on climate attitudes in such a context, it becomes more likely that populism is also shaping citizens’ attitudes in other countries with less partisanship influence.

For our analysis, we used original data from a representative survey with 3,000 respondents from the US, and a survey-embedded framing experiment. We measured populist attitudes and a wide range of different climate-related attitudes with state-of-the-art instruments, and randomly assigned respondents to one of five groups: either to a control group or to a 2 × 2 design that varied both the perception of responsiveness and blame attribution (high vs. low) and the specificity of the political context (climate politics vs. general politics).

The paper is structured as follows. First, we put forward a theoretical argument on how populism and climate attitudes related. We proceed by outlining the research design before presenting our empirical evidence.

Populism, public opinion, and climate change

Given the relevance of public opinion for climate politics (Anderson et al., Citation2017), a large body of scientific work has examined climate-change-related attitudes, and policy preferences (for a comprehensive review, see Drews & van den Bergh, Citation2016). Especially in the US context – the focus of our paper – political identification and ideology appear to be important drivers of public support (opposition) to climate-change mitigation efforts. Dubious about state intervention and regulation, conservatives and Republicans are commonly found to be more climate sceptic and reluctant to support far-reaching climate policies. Their counterparts, liberals and Democrats, are by and large more willing to accept state action and generally support climate change mitigation policies (Dunlap et al., Citation2016; Dunlap & McCright, Citation2008). This conclusion agrees with the findings of the broader literature about party sorting in the US (Baldassarri & Gelman, Citation2008; Fiorina et al., Citation2008; for the case of climate change, see Corner et al., Citation2012). In fact, in statistical analyses of survey data, measures of political ideology (such as party identification or the extent to which an individual’s self-identification as liberal or conservative) tend to outperform other potential determinants of support for climate policies such as age, gender, income, and education (Beiser-McGrath & Huber, Citation2018; Hornsey et al., Citation2016).

Beliefs and values have also been related to how individuals perceive climate change and associated policies. The former include post-material values (Inglehart, Citation1995) as well as broader values associated with life experience and socialization (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002). Beliefs about the urgency and necessity of climate change action also explain policy support (Weber, Citation2016). Furthermore, individuals who have less knowledge about climate change are less concerned and are substantially less likely to support climate policy (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002). Finally, and not surprisingly, climate scepticism is related to policy support. For instance, Bain et al. (Citation2012) have shown that citizens who doubt that the climate is changing, and that human action has caused such changes, are less likely to support policies aimed at mitigating climate change (Bernauer, Citation2013).

As noted by Huber (Citation2020), current forms of top-down climate change communication are bound to fail with individuals who do not feel represented by those who communicate the messages. For British citizens, Huber (Citation2020) finds that populist individuals are substantially more likely to be climate sceptics than non-populist individuals. The question of how to convince these individuals is of substantial relevance to policy-makers, especially in the US context, where a considerable share of the electorate is climate sceptic.Footnote3 Other research has already examined how political actors, by applying populist discourse, might affect political behaviour and political trust (Bos et al., Citation2013; Busby et al., Citation2019; Hameleers et al., Citation2017; Rooduijn et al., Citation2016). With this in mind, our interest lies in better understanding how populism affects how individuals form their policy preferences in psychologically distant issue areas, such as that of climate change (Weber, Citation2016).

Populism and attitudes towards climate change

We move on to a definition of populism and a discussion of how the perception of responsiveness is a central concept in populist resentment. Following the literature, we define populism as a set of ideas that is independent of specific host ideologies such as liberalism or conservatism (Mudde, Citation2004) and which combines three distinct aspects (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018; Mudde, Citation2004). The first aspect is anti-elitism (that is, the idea that the empty vessel of ‘the corrupt elite’ is filled with specific actors that function as the antagonists in populist political discourse). The second aspect provides the counterpart to ‘the corrupt elite’; people-centrism. The positively evaluated empty vessel for populists is ‘pure people.’ These two groups are homogeneous and antagonistic. Because they function largely as empty vessels, populists can put labels on all kinds of actors. For instance, populist climate sceptics find it easy to portray policymakers, scientists, and climate activists as a detached elite that is failing to meet the needs of the average American.

The tension between the two groups is captured in the third aspect: the Manichean discourse that populists apply.Footnote4 That is, populist discourse actively proclaims a moral struggle between good people and the elite. On the one hand, we see those whose will – the volonté générale – is being ignored, and on the other, the corrupt elite that mainly focuses on its own personal gain. These three aspects – elite scepticism, people-centrism, and the Manichean discourse – constitute the populism. To be populist, individuals or organizations have to score high in all aspects. If, for example, an individual is anti-elitist but not people-centred, they do not qualify as populists under this definition (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018).

Populist attitudes are attitudinal manifestations of this set of political ideas at the individual level (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Castanho Silva et al., Citation2018; Van Hauwaert et al., Citation2019; Wuttke et al., Citation2020). These attitudes constitute the demand side that is served by the supply from populist candidates, policy-makers, and parties or political movements.

Climate change (as opposed to changes in weather) lends itself quite well to populist (re)framing (Huber, Citation2020). It is an issue that is rather distant from individual citizens due to its elite-driven and technical character. Given the complexity of climate change and its global nature, policy responses (e.g. the 2015 Paris Agreement) are negotiated in international fora. (e.g. the United Nations), and rely heavily on scientific reports (e.g. by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). This social and political detachment from citizens’ everyday lives increases the psychological distance of citizens from climate change beyond the factual spatial and temporal distance (Weber, Citation2016).

In the realm of such elite-driven and technical issues, it seems plausible that citizen support for given policies depends on individual attitudes towards the central actors in the policy area. In other words, even if an individual has no substantive opinion about how to deal with a given policy challenge, they may support or oppose a given policy dependent on who proposes it. This claim is in line with research on dispositional blame attribution in populist discourse (Busby et al., Citation2019) showing how dispositional frames that highlight the intentional (mis-)behaviour of political actors (Heider, Citation1958) affect political attitudes. In the case of climate change politics, the proponents of new policy measures belong to the political elite of the respective country. However, for individuals with strong populist attitudes, the political elite is the main antagonist. From the viewpoint of the former, rather than the political elite, the general will of homogeneous and good people should inform policy directly and in an unmediated way. Thus, individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more likely to oppose an issue that is promoted by political elites, such as climate change mitigation (Huber, Citation2020), and hold more negative attitudes towards mitigation policy.

However, political ideology might be an important moderator in explaining the relationship between populism and climate attitudes. For instance, individuals evaluate evidence about climate change in line with their political ideology (Zhou, Citation2016). Likewise, the relationship between education, knowledge, and climate concern is highly conditioned on party identification in the US (Hamilton, Citation2011). Within this research, higher education and more knowledge are not associated with more climate concern for Republicans, although better educated and more knowledgeable Democrats are more concerned about climate change. Leiserowitz et al. (Citation2013) have shown that Republicans are much more likely to negatively react to climate scandals (e.g. ‘climate-gate’), while Democrats are largely unaffected by such news.

Additionally, recent literature on populism has developed arguments about the commonalities and differences between left-wing and right-wing populists. While the core features of populism remain the same, regardless of its host ideology (Mudde, Citation2004), the effects of these traits could potentially vary by political ideology. Right-wing populists use cultural terms to distinguish ‘the people,’ whereas left-wing populists refer to economic inequality. This, in turn, affects how right- and left-wing populists relate to ethnic minorities (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2013), their parliamentary behaviour (Otjes & Louwerse, Citation2015), and how they relate to liberal democracy and its functions (Huber & Ruth, Citation2017; Huber & Schimpf, Citation2017).

Last, since individuals receive cues from their parties, assessing the relationship between populism and climate attitudes through the lens of different partisanships is imperative. Such cues might trigger dispositional blame attribution as disliked parties are more likely to be perceived as ‘evil elites’ compared to the preferred party. Given that populist individuals tend to employ a worldview that divides the political sphere into simplistic ‘good vs. evil’ dimensions (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018), one may anticipate that the former individuals will react more strongly to party cue heuristics than non-populist individuals. In other words, populism and dispositional blame attribution might function as an amplifier for pre-existing attitudes and foster the rejection of dissonant information (Druckman & McGrath, Citation2019; Festinger, Citation1962). This motivates an assessment of whether populism and dispositional blame attribution have an independent effect on individuals’ climate attitudes or if party identification moderates the relationship between populist attitudes and climate attitudes.

Responsiveness and attitudes towards climate change

Responsiveness is a key element of the principal-agent relationship (chain of delegation) between voters and political elites in Western representative democracies (Strøm, Citation2000). Citizens delegate to elected officials, hoping they will represent their preferences and respond to changes of opinion. If they fail to do so, citizens ultimately hold them accountable; for example, by voting for other officials.

This chain of delegation has been at the core of populist criticism. Populists tend to claim that elites are not responsive to citizens’ needs and preferences and rather follow their own interests. Thus, the central actors in policy making, ‘the people,’ are mostly left out of the process. In what follows, we argue that claims about responsiveness affect individual climate policy support.

The argument in this section follows the literature on social threat and the activation of authoritarianism (Stenner, Citation2005). We argue that populist attitudes might be latent and, particularly with respect to climate change, can be activated by political entrepreneurs through a process of attributing intentional behaviour to political elites and motivating voters to view the issue in dispositional terms (Busby et al., Citation2019). While societal threats can activate latent authoritarian attitudes (Stenner, Citation2005), a lack of government responsiveness is at the heart of the activation of populist attitudes. To exploit populist attitudes, populist candidates use frames that highlight the lack of elite responsiveness in order to gain electoral success (Andreadis et al., Citation2018). Busby et al. (Citation2019) show that politicians can activate and shape populist attitudes. Thereby, driven by individual perceptions of deficiencies in responsiveness, populism can influence public opinion and political behaviour. Given the aforementioned nature of climate change, elite responsiveness, or the lack thereof, can thus be an additional heuristic for individuals when forming policy preferences.

Feeling represented and considered generally has a positive effect on willingness to support a particular policy. While this holds for all kinds of policies, the abstract and technical nature of climate mitigation policies presents a particularly interesting target for populists and their dispositional blame attribution. Thus, we argue that citizens who learn that political elites are taking their interests into account are more likely to support climate change mitigation measures. If the political elite is portrayed as corrupt and self-interested, citizens are less likely to support policies proposed by these elites. In our experimental study design, this equates to individuals receiving information that political elites are mainly acting for their personal gain and are non-responsive to citizens’ needs and preferences, thus citizens should, on average, be less supportive of climate policy.

Study design

In this section we provide an outline of the survey, the experimental design, and the data analysis methods. To test the aforementioned arguments, we designed a survey that included both an observational and survey-embedded experiment and fielded it via IPSOS between 6 and 14 February 2018, with a sample size of 3,000. Study participants were selected from a non-probability sample with interlocked quotas for age and gender, as well as parallel quotas for urban/rural living conditions, region (four major regions in the US), income, and education.Footnote5 In other words, the sample is representative for the US population along these parameters.

Survey and experimental design

The survey begins with items designed to capture basic demographic data. We used this information to assign respondents to the corresponding quota and screen out individuals who matched quota that were already filled. All respondents then received survey items about populist attitudes (see next section), and were randomly assigned to one of five emphasis-framing treatment groups. Busby et al. (Citation2019) differentiate situational and dispositional (blame) frames. The former make respondents reflect on the circumstances that might have led to policy failure, whereas the latter emphasize the role of specific actors. Our treatments more explicitly focus on the latter type and thus depict elites either as self-serving or caring.

Additionally, Busby et al. (Citation2019) specifically argue that populist rhetoric needs a specific context to be applicable. In other words, ambiguous blame attribution is not able to affect citizens to the same extent as blame attribution that is issue specific; in our case, climate policy. Thus, building on this study, we varied the context and presented the information either in general terms or in a climate-policy-specific issue context. We generally anticipated that the latter would more substantially influence respondents than general information.

This approach resulted in four treatment conditions and a control group, as summarized in .Footnote6 It is important to note that we provided more stylized treatments in order to avoid any conflation of the populist message with politically left or right terminology, or words associated with the Republican or Democratic Party. Thus, these frames lack any thick ideology and present ‘pure’ populist critique, which is necessary for disentangling partisanship from populism. We provide these statements both in a climate-specific and general context in order to test the robustness of the responsiveness argument. While we anticipated that the generalized responsiveness statements would affect individual policy support, we expected the effect to be more pronounced if the frame was explicitly phrased in the climate context. Thus, as argued above, elite responsiveness frames should more effectively alter attitudes in the context of abstract, elite-driven, and technical issue domains such as climate change.

Table 1. Treatment conditions.

After the treatment, we asked respondents about their climate concern, policy support, and willingness to pay for climate mitigation policies. The survey concluded with climate-related and political attitude items. The median duration of survey completion was 10 minutes.

Items for dependent, control variables and methods

For the dependent variable, support for climate policy, we used three different measures. First, we captured climate change concern using three items. The first two items measured agreement with the statements that climate change: (a) is already a serious problem, and (b) will harm the respondent personally (7-point scale). Additionally, respondents were asked to indicate using a 7-point scale when they think climate change will harm people around the globe. We used principal component analysis to extract one single factor about climate concern. Second, we asked respondents to state whether they prefer climate action over jobs and economic growth or vice-versa using a 7-point scale.

Finally, we used five different willingness-to-pay measures. These captured whether individuals are willing to reduce carbon dioxide emissions even if this: (a) means increasing taxes, (b) places an additional burden on households, or (c) reduces government spending in other areas. Respondents were also asked whether they prefer (d) stricter policies to reduce fuel consumption in transportation, and (e) preserve forests. These five questions capture willingness to pay on a 7-point scale. A principal component analysis was used to extract a single factor (Bakaki & Bernauer, Citation2017).Footnote7

These three dependent variables allow us to zoom-in different aspects and dimensions of pro-environmental attitudes, namely concern, policy support and willingness to pay for specific costly climate policies. In essence, these three different outcome variables allow us to test the robustness of our results. Moreover, concern is often portrayed as a key predictor of policy support and willingness to pay (Drews & van den Bergh, Citation2016). Given that populist rhetoric uses strategies of dispositional blame attribution, focusing on elites’ responsiveness towards the needs of everyday citizens rather than the underlying problem itself, populist frames might affect the different outcome dimensions to a different degree. Finally, this selection of dependent variables and their explicit design is intended to reduce potential biases, i.e. by making trade-offs and policy induced costs explicit to respondent.

To measure populist attitudes and their three constitutional facets, we relied on a well-established scale by Castanho Silva et al. (Citation2018; also see Citation2019). provides the question wordings for each dimension. Besides already having been extensively tested in several settings, including the US, this measure disentangles populist attitudes into three dimensions to capture the theoretical sub-components of populism: people centrism, elite-scepticism, and Manichean discourse. Other well-established scales, such as the scale by Akkerman et al. (Citation2014), do not allow us to differentiate the different sub-components. Other scales (e.g. Schulz et al., Citation2017), while providing important insights into populist attitudes, put less emphasis on the interaction between the different sub-components, as outlined in Hawkins and Kaltwasser (Citation2018). To extract the single dimensions, we followed Castanho Silva et al.’s (Citation2018) suggestion to use principal component analyses on each of the sub-dimensions (anti-elitism, people-centrism, and Manichean outlook). This resulted in three scales with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. We added the minimum to each scale and multiplied the extracted scores. This procedure is as close as possible to the theoretical concept of populism which requires an entity to hold high levels of anti-elitism, people-centrism and a Manichean outlook simultaneously (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018; Wuttke et al., Citation2020). It is important to note that the level of populist attitudes does not substantially vary by partisanship (see Figure A8 in the Appendix, refer supplementary material).

Table 2. Populist attitudes.

The empirical models were estimated using ordinary least squares regression with robust standard errors and multinomial regression analysis, depending on the scale of the dependent variable. To test to what extent populism has an independent effect on climate policy attitudes, we regressed our dependent variables on populist attitudes, party identification, and their interaction. Thereby, we explicitly control for levels of partisanship and populism and all their non-linear interactions. Populism implicitly also controls for prior perceptions of responsiveness. For our experimental design, we used the treatment assignment as an independent variable. In all models, we controlled for age, climate knowledge, education, employment, gender, income, living conditions (urban vs. rural), and region. We additionally included interactions of the treatments with party identification and populist attitudes. Descriptive statistics for all variables in the analysis can be found in the Appendix (see supplementary material).Footnote8

Empirical findings

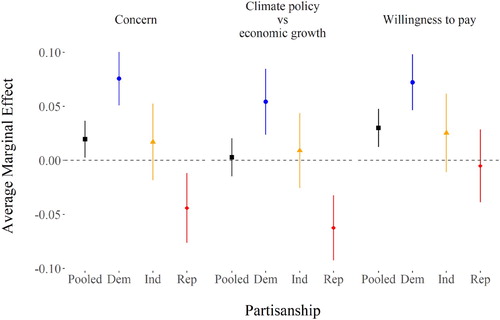

Altogether, we examined if the relationship between populism and climate attitudes is independent or moderated by partisanship. In fact, shows that individuals’ level of populism only modestly affects their concern about climate change and their willingness to pay. However, also shows that the effect of citizens’ level of populism on climate concern and policy attitudes is heavily conditioned by party identification (see also regression table A4 in the Appendix (see supplementary material)).Footnote9

Figure 1. Populism, political ideology, and climate attitudes.

Note: Estimates stem from an OLS regression with robust standard errors. The coefficients all show the pooled and thus unconditional correlation of populist attitudes (dark lines). D, R, and I stand for Democrat, Republican and Independent, respectively (bright, coloured lines). Conditional coefficients also control for treatment assignment. We included age, climate knowledge, education, employment, gender, income, living conditions, and region as control variables. All dependent variables are standardized (mean = 0, sd = 1). Full regression tables including goodness-of-fit indicators and control variables can be found in the Appendix (Table A4, refer supplementary material).

This indicates that populism is positively associated with climate concern, policy support, and willingness to pay amongst those considering themselves to be Democrats. Amongst Republicans, however, populism is negatively associated with climate change concern and policy support. Independents are not substantially affected by their level of populism. While the results suggest that populism matters for citizens’ climate change attitudes, it also clearly amplifies the effect of partisanship. This finding is in line with previous research, which has shown that populism might strengthen polarization and subsequently might amplify existing differences in policy attitudes between groups. While the specific dynamics of partisan polarization on the climate issue are specific to the US case, such amplifying effects are likely to affect individuals in other countries and contexts as well (see, for example, Hameleers & Schmuck, Citation2017). In essence, the very definition of populism highlights its feature as a thin-centred ideology and amplifies the effects of its host ideology, e.g. through negative identifications with partisanship (see Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2018).

Responsiveness and attitudes towards climate change

The above-mentioned observational findings provide an important starting point for better understanding the effects of populist discourse and dispositional blame attribution on public opinion about climate change and climate policies. To move beyond observational findings and examine the causal relationship between responsiveness and climate attitudes, we randomly assigned study participants to either a control group or one of the four frames (see ).

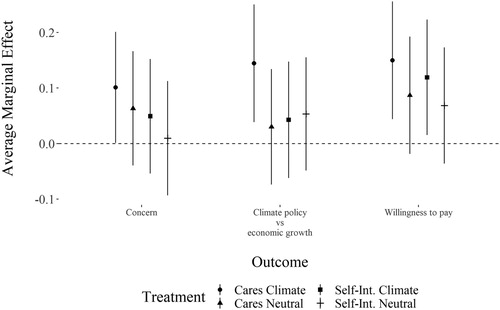

shows the experimental evidence for all standardized dependent variables. The only treatment that substantially increases concern, policy support, and willingness to pay is the climate-specific-high-responsiveness frame, by around 0.1–0.15 standard deviations. As to the first dependent variable, individual climate concern is higher in the climate-specific-high-responsiveness frame. Similarly, as to the second dependent variable, support for climate policy vs. economic growth, the treatment that indicates well-functioning political representation increases the policy support of individuals.

Figure 2. Populism, political ideology, and climate attitudes.

Note: Estimates stem from an OLS regression with robust standard errors. The coefficients are marginal effects of the treatments. We interacted the treatments with populism and party identification. We included age, climate knowledge, education, employment, gender, income, living conditions, and region as control variables. All dependent variables are standardized (mean = 0, sd = 1). For full regression tables including goodness-of-fit indicators and control variables, see Table A4 in the Appendix (see supplementary material).

Finally, the last dependent variable measures willingness to pay for climate policy. shows that the climate-specific-high-responsiveness treatment has a positive effect on willingness to pay. Both the general high-responsiveness- and the climate-specific-low-responsiveness frames substantially increase willingness to pay for climate action, although the effect sizes are smaller than for the climate-specific-high-responsiveness frame. The result indicates that context-specific statements about the responsiveness of elites can modestly increase individuals’ willingness to pay and contribute to public goods like climate protection. The effect of the climate-specific-low-responsiveness frame could reflect a reaction to a perceived government failure to deal with climate change, which in turn could trigger individual contributions and action for coping with this issue. These findings also highlight that while both elite self-interested frames were anticipated to have a negative effect, we did not find any evidence to support this expectation.

In sum, the treatment emphasizing that the political elite is responsive to citizens’ needs and preferences in a climate-specific context significantly increased climate concern, support for climate policy, and willingness to pay. We did not find these effects for the context-independent, general elite responsiveness statements. Other treatments that blame elites for being non-responsive have no consistent effects on these outcomes, and do not significantly decrease climate concern nor support for climate policy and willingness to pay.

Conclusion

Overall, this paper examines the relationship between populist attitudes, responsiveness, and individual attitudes to climate change. Due to the technical and elite-driven nature of climate policy, both a populist worldview and dispositional cues about elite responsiveness potentially provide important heuristics for individuals in terms of their support for these policies. Our observational and experimental results, based on original and representative survey data for the US, suggest that populist attitudes are associated with climate attitudes. The evidence also shows that populism amplifies the effect of partisanship. The experimental results confirm that individuals who receive the information that political elites care about citizens’ needs and preferences are more likely to be concerned about climate change, to support climate policies, and to be willing to pay for these policies. However, in contrast to our expectations, cues that commonly appear in populist discourse that involve blaming politicians for their indifference towards citizens’ preferences have no negative effect on policy support. By and large, the findings show that populism and dispositional blame attribution have a role in explaining citizens’ attitudes in the specific context of climate change, but that the independent effects of the former are smaller than suggested by the heated debate about populist discourse.

Ultimately, these findings have implications for research on climate policy. While some scholars have expressed concern that partisanship has been used as the only measure of political ideology, we find that populist attitudes on their own add little to understanding climate attitudes in the US. Our experimental evidence substantializes this finding and suggests that, if anything, political entrepreneurs could foster support for climate policies, at least to some extent, by emphasizing elite responsiveness to citizens’ needs and preferences in this specific issue area, rather than blaming elites for their lack of responsiveness. This is ‘good news’ for climate policy, given that populist discourse and dispositional blame attribution does not seem to be undermining climate policy support directly. However, further research should focus on how party sorting and polarization along party lines moderates the effects of dispositional frames on citizens’ climate attitudes rather than just the attitudes of the latter towards the elite writ large. More comparative and field experimental research is also warranted to validate the effects obtained here. One limitation of the present study is that survey experimental interventions are too weak and have too little external validity compared to real-world forms of political framing (Kahan & Carpenter, Citation2017).

A recent systematic review of the framing literature in the field of environmental policy has shown that existing survey-embedded framing experiments tend to over report significant treatment effects (Fesenfeld et al., Citation2019). In this sense, the null findings in the present study are not surprising, yet future research needs to validate to what extent they are an artefact of the chosen method or truly evidence for limited effects of populist rhetoric on citizens’ climate policy attitudes. By definition, distilling populism from its ideological host and studying its independent effect on policy attitudes is essential for our study. However, in the real-world debate, populist messages are usually combined with ideological content, e.g. right-wing populist messages against climate mitigation made by US president Donald Trump. At the same time, citizens may or may not be confronted with several, competing sources of information and ideologically loaded messages (e.g. depending on the media ecosystem they are embedded in). These messages are likely to be more accessible than ‘pure’ populist messages. Future research could assess these interactions between populism and ideological content in experiments in more detail. Depending on individuals’ prior attitudes and beliefs, ideologically loaded populist frames might affect citizens’ climate attitudes differently. Another fruitful endeavour for future research is to study competing frames (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007) or framing effects over time (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010) using a set of different populist and non-populist messages.

Understanding these dynamics in the US is of utmost importance. Global climate change is unlikely to be successfully mitigated without the US adopting effective climate policies. Given the polarized public debate in the US, it is hence key to understand how public support for such effective mitigation measures can be increased. Our findings imply important policy recommendations. By showing that less technical, top-down, and more empathetic communication of climate-related policy goals might help to increase acceptance and support for these policies, we provide policymakers with guidance on how to approach populism-prone communities. While Bernauer and McGrath (Citation2016) argue that merely (re)framing why climate policies are important is unlikely to substantially change the public's appetite for stronger climate policy, we find that the credible communication of elite responsiveness, rather than merely focusing on the provision of information and facts, could potentially help increase public support (Nisbet & Scheufele, Citation2009). This conclusion is in line with dual-process theory (Kahneman, Citation2003) and source cue literature (Goren et al., Citation2009) which highlight that both intuition and reasoning guide information processing. Our findings, while tested on a US sample, should apply more generally to citizens who feel left behind and disenfranchized. Future research could test this in different contexts, to empirically examine the generalisability (see, for example, Harring et al., Citation2019).

Beyond the implications for climate politics, our findings also speak to the populism and representation literature in more general terms. Populism and representation are strongly connected, both in the way populist discourse treats and potentially affects liberal democracy and its elites (Caramani, Citation2017), but also in how representation and the lack thereof explains why populist discourse mobilizes individuals, at least to some extent (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, Citation2018; Rooduijn et al., Citation2016). Our research ultimately contributes to this particular discussion of how populism and representation are related.

For the research on populism, our paper provides a new perspective about the consequences of populism and dispositional blame attribution. While research on the consequences of populism has started only recently, it focuses mainly on the implications for liberal democracy (Huber & Schimpf, Citation2016), immigration policy (Akkerman, Citation2012), and political polarization (Rooduijn et al., Citation2016). Research on the relationship between populism and climate policy is still rare (Huber, Citation2020; Lockwood, Citation2018). Given the technical and elite-driven nature of climate change communication and policy-making, the average citizen's psychological distance from this issue remains sizeable (Weber, Citation2016), as with other issue areas, such as international trade. Thus, climate change and other elite-driven, abstract, and distant policy fields constitute ideal grounds for populist attacks against the governing political elite. Perceived elite responsiveness and dispositional blame attribution are of central importance in such debates. While merely providing a starting point, our paper will hopefully encourage further research that assesses the consequences of populism, dispositional blame attribution, and elite responsiveness in a variety of policy contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (339 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Brilé Anderson, Liam F. Beiser-McGrath, Andreas Dür, Reinhard Heinisch, Fabian G. Neuner, Quynh Nguyen, Christian H. Schimpf, Linda Steg, Steven M. Van Hauwaert, and Michael L. Wicki for commenting on previous versions of this paper. We also thank the audiences at the ECPR General Conference in Hamburg (August 2018) and the ECPR Joint Sessions (April 2019) for valuable comments. All errors remain ours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

ORCID

Robert A. Huber http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6536-9392

Lukas Fesenfeld http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4504-036X

Thomas Bernauer http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3775-6245

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For example, Donald Trump tweeted (on 14 October 2014) that ‘as ISIS and Ebola spread like wildfire, the Obama administration just submitted a paper on how to stop climate change (aka global warming).’

2 See, for example, https://www.iowapublicradio.org/post/sanders-would-target-fossil-fuel-companies-corruption-role-climate-change#stream/0. Last accessed 12. December 2019.

4 Hawkins (Citation2009, p. 1043) argues ‘populism is a Manichaean discourse because it assigns a moral dimension to everything, no matter how technical, and interprets it as part of a cosmic struggle between good and evil’ (also see de la Torre, Citation2000).

5 Quota sampling is obviously inferior to a real random sample, however, in reality it is often hard to acquire a random sample of a nationwide population. Empirical assessment of differences between probability based (random) samples and quota-based samples point towards small differences, if any (Coppock & McClellan, Citation2019; Simmons & Bobo, Citation2015). Additionally, Ansolabehere and Schaffner (Citation2014) demonstrate that opt-in online samples provide similar estimates as random samples in the US.

6 Tables A1, A2, and A3 in the Appendix (see supplementary material) illustrate the balance tests for central demographic data and populist attitudes. These results show that our randomization worked properly.

7 All survey items are available in the Appendix (see supplementary material) and the corresponding ‘survey’ section.

8 Replication materials, including the datasets and RScripts, are publicly available on the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HXHL97.

9 We plotted the interaction effects to better assess the significance of each term, in line with Brambor et al. (Citation2006).

References

- Akkerman, T. (2012). Comparing radical right parties in government: Immigration and integration policies in nine countries (1996–2010). West European Politics, 35(3), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665738

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Anderson, B., Böhmelt, T., & Ward, H. (2017). Public opinion and environmental policy output: A cross-national analysis of energy policies in Europe. Environmental Research Letters, 12(11), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8f80

- Andreadis, I., Hawkins, K. A., LLamazares, I., & Singer, M. (2018). The conditional effects of populist attitudes on voter choices in four democracies. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and method (pp. 238–279). Routledge.

- Ansolabehere, S., & Schaffner, B. F. (2014). Does survey mode still matter? Findings from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Political Analysis, 22(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt025

- Bain, P. G., Hornsey, M. J., Bongiorno, R., & Jeffries, C. (2012). Promoting pro-environmental action in climate change deniers. Nature Climate Change, 2(8), 600–603. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1532

- Bakaki, Z., & Bernauer, T. (2017). Citizens show strong support for climate policy, but are they also willing to pay? Climatic Change, 145(1–2), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2078-x

- Baldassarri, D., & Gelman, A. (2008). Partisans without constraint: Political polarization and trends in American public opinion. American Journal of Sociology, 114(2), 408–446. https://doi.org/10.1086/590649

- Beiser-McGrath, L. F., & Huber, R. A. (2018). Assessing the relative importance of psychological and demographic factors for predicting climate and environmental attitudes. Climatic Change, 149(3–4), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2260-9

- Bernauer, T. (2013). Climate change politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 421–448. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-062011-154926

- Bernauer, T., & McGrath, L. F. (2016). Simple reframing unlikely to boost public support for climate policy. Nature Climate Change, 6(7), 680–683. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2948

- Bos, L., van der Brug, W., & de Vreese, C. H. (2013). An experimental test of the impact of style and rhetoric on the perception of right-wing populist and mainstream party leaders. Acta Politica, 48(2), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2012.27

- Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpi014

- Busby, E. C., Gubler, J. R., & Hawkins, K. A. (2019). Framing and blame attribution in populist rhetoric. The Journal of Politics, 81(2), 616–630. https://doi.org/10.1086/701832

- Caramani, D. (2017). Will vs. reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. American Political Science Review, 111(01), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000538

- Castanho Silva, B., Andreadis, I., Anduiza, E., Blanuša, N., Corti, Y. M., Delfino, G., Rico, G., Ruth-Lovell, S. P., Spruyt, B., Steenbergen, M., Littvay, L. (2018). Public opinion surveys: A new scale. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and method (pp. 150–179). Routledge.

- Castanho Silva, B., Jungkunz, S., Helbling, M., & Littvay, L. (2019, March). An empirical comparison of seven populist attitudes scales. Political Research Quarterly . Article 106591291983317. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919833176

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing public opinion in competitive democracies. American Political Science Review, 101(4), 637–655. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055407070554

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2010). Dynamic public opinion: Communication effects over time. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 663–680. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000493

- Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics, 6(1), 205316801882217. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822174

- Corner, A., Whitmarsh, L., & Xenias, D. (2012). Uncertainty, scepticism and attitudes towards climate change: Biased assimilation and attitude polarisation. Climatic Change, 114(3–4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0424-6

- Drews, S., & van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. (2016). What explains public support for climate policies? A review of empirical and experimental studies. Climate Policy, 16(7), 855–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1058240

- Druckman, J. N., & McGrath, M. C. (2019). The evidence for motivated reasoning in climate change preference formation. Nature Climate Change, 9(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0360-1

- Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2008). A widening gap: Republican and democratic views on climate change. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 50(5), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.50.5.26-35

- Dunlap, R. E., McCright, A. M., & Yarosh, J. H. (2016). The political divide on climate change: Partisan polarization widens in the U.S. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 58(5), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2016.1208995

- Fesenfeld, L., Sun, Y., Wicki, M. L., & Bernauer, T. (2019, September 4–6). How to effectively motivate costly environmental policies and actions? – A comparative assessment of framing experiments. International Conference on environmental Psychology, Plymouth, United Kingdom.

- Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Reissued by Stanford Univ. Press in 1962, Renewed 1985 by author, [Nachdr.]. Stanford Univ. Press.

- Fiorina, M. P., & Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.153836

- Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. A., & Pope, J. C. (2008). Polarization in the American public: Misconceptions and misreadings. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 556–560. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238160808050X

- Flaxman, S., Goel, S., & Rao, J. M. (2016). Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 298–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw006

- Goren, P., Federico, C. M., & Kittilson, M. C. (2009). Source cues, partisan Identities, and political value expression. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 805–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00402.x

- Green, M., & White, J. K. (2019). Populism in the United States. In D. Stockemer (Ed.), Populism around the world (pp. 109–122). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96758-5_7

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). “They did it”: The effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Communication Research, 44(6), 870–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216644026

- Hameleers, M., & Schmuck, D. (2017). It’s us against them: A comparative experiment on the effects of populist messages communicated via social media. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1425–1444. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328523

- Hamilton, L. C. (2011). Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change, 104(2), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9957-8

- Harring, N., Jagers, S. C., & Matti, S. (2019). The significance of political culture, economic context and instrument type for climate policy support: A cross-national study. Climate Policy, 19(5), 636–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1547181

- Hawkins, K. A. (2009). Is Chavez populist?: Measuring populist discourse in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 42(8), 1040–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009331721

- Hawkins, K. A., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2018). Introduction: The ideational approach. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and method (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley.

- Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2943

- Huber, R. A. (2020). The role of populist attitudes in explaining climate change skepticism and support for environmental protection. Environmental Politics, 1–,24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1708186

- Huber, R. A., & Ruth, S. P. (2017). Mind the gap! populism, participation and representation in Europe. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 462–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12280

- Huber, R. A., & Schimpf, C. H. (2016). Friend or foe? Testing the influence of populism on democratic quality in Latin America. Political Studies, 64(4), 872–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12219

- Huber, R. A., & Schimpf, C. H. (2017). On the distinct effects of left-wing and right-wing populism on democratic quality. Politics and Governance, 5(4), 146–165. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v5i4.919

- Inglehart, R. (1995). Public support for environmental protection: Objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. PS: Political Science and Politics, 28(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/420583

- Kahan, D. M., & Carpenter, K. (2017). Out of the lab and into the field. Nature Climate Change, 7(5), 309–311. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3283

- Kahneman, D. (2003). Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics. American Economic Review, 93(5), 1449–1475. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803322655392

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Layman, G. C., Carsey, T. M., & Horowitz, J. M. (2006). Party polarization in American politics: Characteristics, causes, and consequences. Annual Review of Political Science, 9(1), 83–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105138

- Leiserowitz, A. A., Maibach, E. W., Roser-Renouf, C., Smith, N., & Dawson, E. (2013). Climategate, public opinion, and the loss of trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(6), 818–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764212458272

- Lockwood, M. (2018). Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: Exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics, 27(4), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411

- McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change, 21(4), 1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2013). Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.11

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018, July). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies. Article 001041401878949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018789490

- Neumayer, E. (2004). The environment, left-wing political orientation and ecological economics. Ecological Economics, 51(3–4), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.06.006

- Nisbet, M. C., & Scheufele, D. A. (2009). What's next for science communication? Promising directions and lingering distractions. American Journal of Botany, 96(10), 1767–1778. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.0900041

- Oliver, J. E., & Rahn, W. M. (2016). Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 election. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216662639

- Otjes, S., & Louwerse, T. (2015). Populists in parliament: Comparing left-wing and right-wing populism in the Netherlands: Populists in parliament. Political Studies, 63(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12089

- Page, B. I., & Shapiro, R. Y. (1983). Effects of public opinion on policy. American Political Science Review, 77(01), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1956018

- Rooduijn, M., van der Brug, W., & de Lange, S. L. (2016). Expressing or fuelling discontent? The relationship between populist voting and political discontent. Electoral Studies, 43(September), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006

- Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., & Wirth, W. (2017, February). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw037

- Simmons, A. D., & Bobo, L. D. (2015). Can non-full-probability internet surveys yield useful data? A comparison with full-probability face-to-Face surveys in the domain of race and social inequality attitudes. Sociological Methodology, 45(1), 357–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081175015570096

- Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. Cambridge studies in public opinion and political psychology. Cambridge University Press.

- Strøm, K. (2000). Delegation and accountability in parliamentary democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 37(3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00513

- Torre, C. d. l. (2000). Populist seduction in Latin America the Ecuadorian experience. Ohio University Center for International Studies. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&AN=67461

- Torre, C. d. l. (2015). The promise and perils of populism: Global perspectives. University Press of Kentucky.

- Van Hauwaert, S. M., Schimpf, C. H., & Azevedo, F. (2019, July). The measurement of populist attitudes: Testing cross-National scales using item response theory. Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395719859306

- Weber, E. U. (2016). What shapes perceptions of climate change? New research since 2010: What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(1), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.377

- Wlezien, C. (1995). The public as thermostat: Dynamics of preferences for spending. American Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111666

- Wuttke, A., Schimpf, C., & Schoen, H. (2020). When the whole is greater than the sum of its parts: On the conceptualization and measurement of populist attitudes and other multidimensional constructs. American Political Science Review, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000807

- Zhou, J. (2016). Boomerangs versus javelins: How polarization constrains communication on climate change. Environmental Politics, 25(5), 788–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2016.1166602