ABSTRACT

Given the growing international pressure to mitigate climate change and increasing fears around climate impacts, current expectations of continued investment in fossil fuels in Southeast Asia’s power sector appear puzzling. This paper explores how power sector investors perceive climate-related risks and how they factor these risks into investment decision-making. In doing so, we seek to explain why countries in Southeast Asia are making plans for – and investors are continuing to invest in – predominantly fossil fuel-based power generation at the expense of renewable or clean generation options, and what it would take to substantially shift investment from fossil fuel-based generation into renewable options in the region. Analysis of 17 interviews with industry experts suggests that there is a significant gap between the need to integrate climate-related risks within investor decision-making, and the way these risks are currently being integrated and addressed in the Southeast Asia power sector. Climate-related risk appears to be either not a significant factor, ignored in light of other concerns, or only superficially integrated into decision-making. The results of this research point to an urgent need for action targeted at energy-sector investors in the region in order to shed light on climate-related risks, share information on the likelihood and magnitude of risks, lay out clearly the potential for stranded assets in a 10–15-year time frame, and encourage transparent, open and respectful dialogue and discussion on these critical issues.

Key policy insights

Power sector investors in Southeast Asia generally do not consider climate-related risks as a significant factor when making investment decisions.

Dominance of established routines and mindsets lead to omission of in-depth analysis of climate-related risks and skewed perceptions of risk in renewable energy investments.

Pressure to commit large sums through recognized investment channels creates path dependency towards continued financing of large-scale fossil fuel projects.

Financial governance mechanisms generally have very low compliance requirements regarding reporting on and mitigating climate-related risks.

Policy and regulatory action is needed to raise awareness of climate-related risks, lay out potential for stranded assets and create opportunities for investing in renewable energy.

1. Introduction

In April 2019, the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, warned the global financial sector that it could face severe losses if it did not start paying more attention to climate change risks when considering where to invest (Partington, Citation2019). Carney stated that pressure to rethink energy investments comes from two sides: the need to act on climate mitigation commitments, and growing awareness of energy infrastructure investments that may be increasingly vulnerable to climate impacts. This is especially a challenge in Southeast Asia, where many countries view fossil fuels as a low-cost means of meeting rising energy demand and powering their fast-growing economies.

Over the last two decades, economic growth in the 10 member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam – has been accompanied by large increases in energy demand. Between 2000 and 2016, primary energy demand grew by approximately 70%, driven by a range of factors, including rising incomes, continued urbanization, increased energy access and population growth (IEA, Citation2017).

As part of its global commitments to reduce carbon emissions during the coming decades, ASEAN has set a target across its member countries of reducing energy intensity 20% by 2020 and 30% by 2025 compared to a business-as-usual scenario, and reaching a 23% share of renewable energy in total primary energy supply by 2025 (ASEAN Centre for Energy, Citation2015). However, despite large potential for renewables (REN21, Citation2019), fossil fuels currently dominate the energy mix, accounting for 70% of total energy demand, and this dominance is expected to continue (IEA, Citation2017).

This is a major concern for global climate change mitigation efforts: current global fossil fuel infrastructure already puts us past a 1.5°C target (Tong et al., Citation2019) and without a significant shift in Southeast Asia’s energy portfolio it will be impossible to reach ‘well below’ 2°C (Zhou et al., Citation2020). Moreover, it raises significant concerns about energy infrastructure assets that may be climate-vulnerable and could potentially become stranded assets (Caldecott, Citation2017; Riedl, Citation2020; Scott Cato & Fletcher, Citation2019) – defined by Bos and Gupta (Citation2019, p. 1) as ‘assets that lose economic value well ahead of their anticipated useful life’. Whilst an estimated US$ 2.5 trillion of global financial assets are directly at risk from physical effects of climate change (Dietz et al., Citation2016), the potential for a global wealth loss from stranded assets is estimated to be between US$1–4 trillion (Mercure et al., Citation2018).

In some regions of the world, concerns about stranded assets – accompanied by pressure from social movements (Piggot, Citation2018) – has translated into action through decisions on energy infrastructure investments (for example, see Buckley, Citation2019). Recently, many large multinationals have started to make pledges to reduce the carbon intensity of their energy investments. For example, in 2016 global power producer Engie pledged to divest US$ 15.1 billion of its fossil fuel-based assets during 2016–2018, and to reinvest in lower-carbon, distributed, and renewable energy assets (Baker, Citation2016). In 2018, AES, another global power producer, announced a goal to reduce its carbon intensity by 70% by 2030 and to shift its energy asset holdings from fossil fuel-based energy production into renewable energy. Indeed, AES is the first publicly-traded owner of utilities and power companies based in the US to disclose the resilience of its portfolio, consistent with the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) (AES, Citation2018; TCFD, Citation2017). Meanwhile, Sembcorp, a Singapore-based regional power producer, has pledged to reduce its CO2 emissions by investing in energy efficiency improvements, expanding its gas and renewables portfolio, and developing new business models for green products and services (Sembcorp, Citation2018).

Despite hopes that climate-related risk would become a standard element in the fiduciary duties of officers of all multinational corporations (TCFD, Citation2017), company disclosure of information on potential financial impacts of climate change remains insufficient for investors to consider climate-related risks in their investment decisions (TCFD, Citation2019). However, investors and fund managers in many countries are beginning to become aware of the importance of identifying and managing climate-related risks. Recent evidence suggests banks in Japan, South Korea and Singapore are increasingly unwilling to lend for fossil fuel projects (Murtaugh, Citation2020). In a 2018 survey, more than 60% of 562 respondents from six ASEAN countries agreed that, in the coming decade, there would be increased pressure on investors and fund managers to assign higher risk ratings and reduce investment exposure to fossil fuel assets (Eco-Business Research, Citation2018). However, the extent to which this increased awareness is translating into widespread changes in investment behaviour within Southeast Asia remains unclear.

Against this background, we explore how investors in the power sector in Southeast Asia make decisions about their investments. In particular, we analyze the factors that might be driving investors toward cleaner investments (or not). In doing so, we seek to explain why countries in Southeast Asia are making plans for – and investors are continuing to invest in – predominantly fossil fuel-based power generation at the expense of renewable power generation options. We also ask what it would take to substantially shift investment from fossil fuel-based generation into renewable options in the region. To answer these questions, we analyze how investors in fossil fuel-based power supply perceive climate-related risks and how they factor these risks into investment decision-making in the region’s power sector.

2. Climate-related risks in power sector investment

2.1. Assessing investment risk

When deciding on how to invest their assets – or the assets of their financial institutions – investors generally seek to identify ‘how best to allocate the assets between asset classes to minimize the risk of not meeting [their] liabilities at the lowest cost’ (Silver, Citation2017, p. 99); in other words, investors look for ways to generate profits while minimizing risks (Mayo, Citation2019). In order to do this, an investor will decide upon a range of asset classes to invest in, each of which will have different degrees of potential risk and return.

Decisions on which types of asset to invest in depend on a variety of factors. One factor is the character and background of individual investors – their education, experience, mindset, attitude to risk, financial knowledge, sector knowledge, and discretion over the portfolio (Baker et al., Citation2017; Hirshleifer, Citation2015). Another factor is the type of institution on behalf of which an investor is acting. Its governing constitution may play a role (including the board of the institution, its fiduciary duties and the level of risk it is willing to take), so might its size, practical considerations (for example, the cost of investing in an asset class), professional practice, ethics and other codes of conduct and regulations (Silver, Citation2017).

Decisions around power sector investments will also be affected by the nature of the investment and the extent to which it is considered ‘bankable’ – the project and project partners are considered creditworthy and reputable, there is a solvent and reliable ‘offtaker’ to buy the power, the legal framework of the country in which the project is based is deemed manageable and there are adequate guarantees in place to mitigate risks (Koh, Citation2018). Investors will rely on both formal risk accounting and informal networks to identify issues and risks associated with an investment. More recently, many investors have also begun to consider how the risks – and opportunities – posed by climate change will affect their investment decisions.

2.2. Incorporating climate-related risk into investment decisions

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), broadly defines risk as ‘the potential for consequences where something of value is at stake and where the outcome is uncertain’ (IPCC, Citation2014, p. 127). From this, climate-related risk is typically understood as a function of the probability of a certain hazardous climatic event multiplied by the severity of impacts and the vulnerability to those impacts. This definition allows for direct risks associated with exposure to certain hazardous climatic events (e.g. flooding of a power station or destruction of transmission infrastructure due to a storm) and indirect risks associated with exposure to actions related to reducing or reacting to direct risks (e.g. regulations on carbon emissions or on how power stations must plan for hazardous events).

As the risk-return profile of assets exposed to climate-related risks becomes more uncertain and as pressure grows to divest from companies that work in fossil fuels, investors are starting to rethink where to put their money. But incorporating climate-related risk into investment decisions remains a significant challenge. Major obstacles include finding ways to quantify climate-related risks (Bender et al., Citation2019) and stranded asset potential (Buhr, Citation2017), limitations of established financial risk models (Thomä & Chenet, Citation2017) and lack of information (TCFD, Citation2017; Thomä et al., Citation2019). Some power sector investors may choose to put faith in technological development to mitigate risk, such as carbon capture and storage from coal plants (Byrd & Cooperman, Citation2018). Others may seek to move out of certain asset classes: for example, the Fourth Swedish National Pension Fund (APA) recently decided to divest from 22 coal companies (Environmental Finance, Citation2018). But for many, these options are not available or simply too difficult to assess. Additionally, climate-related risks are increasingly affecting the insurance industry, which is on high alert about direct risks, as insurers have been paying back an increasing amount of weather-related claims (University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership and PwC, Citation2016).

2.3. A framework for analyzing climate-related risks

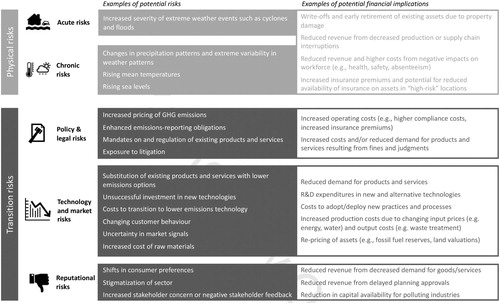

In order to understand how climate-related risks are factored into decisions to invest in power plants in Southeast Asia, we applied a climate-related risk framework based upon the work of TCFD (Citation2017) and Clapp et al. (Citation2017). The framework, shown in , follows the literature in categorizing direct and indirect climate-risks as ‘physical’ and ‘transition’ risks, respectively (Bender et al., Citation2019; Clapp et al., Citation2017; TCFD, Citation2017; see Thomä & Chenet, Citation2017).

Figure 1. Categories of climate-related risks. Source: Adapted from TCFD (Citation2017) and Clapp et al. (Citation2017).

Physical risks comprise risks related to potential changes in the physical environment. These changes may be acute, such as extreme weather events linked to climate change, which may disrupt assets and operations, and the economic value chains and communities in which power plants operate. They may also be chronic, such as long-term changes in weather patterns, average temperatures and sea levels, affecting availability of resources, such as water and land, and reliability of existing wind patterns and solar irradiance levels.

Transition risks comprise risks related to potential responses to mitigate and adapt to climate change by governments, regulators, private sector competitors, consumers and concerned citizens, which may lead fossil fuel assets to become devalued and even stranded. We separate theses transition risks into three categories:

Policy and legal risks: These risks include the range of legal, regulatory, policy and liability issues related to climate change that affect energy investments. For example, governments may set a price for carbon emissions or restrictions on the use of certain energy sources (SASB, Citation2018); central banks may incorporate enhanced risk measures into financial regulations (Campiglio et al., Citation2018); and legal systems might increasingly consider liability claims for climate harms, or for damages associated with stranded assets (Burger & Wentz, Citation2018; Ganguly et al., Citation2018).

Technology and market risks: Falling costs and improved performance of new and emerging technologies such as photovoltaic, energy storage, smart grids and downstream technologies (including electric vehicles and decentralized generation) are bringing about significant changes in the energy landscape. To keep up with the changing needs of power markets, shifting consumer behaviour and scarcity of raw materials, investment is needed to develop new and low-carbon technologies, which may fail to come to market.

Reputational risks: Pension funds, asset managers, and shareholders are increasingly focused on the impact of climate change and how energy companies respond to climate-related risks and opportunities. There is significant pressure from many of these stakeholders to divest from investments in coal power plants and other fossil-fuel energy assets.

3. Research methods

Our framework for analyzing climate-related risks focuses on developing a practical understanding of how institutional investors in Southeast Asia consider different climate-related risks when making investment decisions. Our analysis had three components. First, we sought to explore how different physical and transition climate-related risks were perceived by investors. Second, we sought to understand how those climate-related risks were factored into investment decisions, including whether they raised concerns over potential for stranded assets. Third, we explored the main factors driving these perceptions of climate-related risk.

Data was gathered from interviews with 17 industry experts working in Southeast Asia’s power sector, undertaken over the period June 2018 to February 2019. A shown in , interview respondents included representatives of 6 commercial investors, 1 charitable foundation, 2 development finance institutions, 1 insurance company, 2 international organizations, 3 private consultancy firms and 1 research institute. Respondents were selected non-randomly by drawing on existing networks to identify key actors, and using the ‘snowball’ technique with these key actors to identify further relevant respondents. We asked respondents questions about how they understood, assessed and made decisions around physical and transition risks, including whether they consider stranded assets to be a significant risk in the Southeast Asia power sector. We asked investors to reflect on how they factored different risks into their own investment decision-making. We also asked those who were not investors to reflect on their experience of how investors factored the different risks into investment decision-making.

Table 1. List of interview respondents.

Data analysis involved compiling and coding interview notes and transcripts with reference to how different physical and transition risks were perceived to play a role in investment decision-making. Our analysis combined insights from investor respondents and non-investor respondents to present common themes and alternative perspectives from experts on each category of climate-related risk, and potential for stranded assets. Where appropriate and useful, we illustrate some insights with direct quotes from interview respondents, giving them a direct voice in our analysis.

4. Results

In this section, we analyze how climate-related risks are perceived by power sector investors in Southeast Asia, based on insights from our interviews with key stakeholders in the sector. We use the climate-related risk framework to structure our analysis, covering physical risks and three types of transition risks (see ). We also reflect on how these risks relate to perceptions of potential stranded assets.

4.1. Acute and chronic physical risks

In terms of investment in the energy sector, the physical risks of climate change refer to the increased likelihood of extreme weather conditions and events as well as longer-term changes in weather patterns, average temperatures and sea levels, and how these would impact on power generation, transmission and distribution assets. Generally, these physical risks were considered a well-understood and expected component of investment due diligence (Interviews CI5, CI6, DFI1, IO1, RI1). Moreover, according to one investor (Interview CI1), growing concern over potential physical risks in an increasingly uncertain climate meant environmental and social impact assessment had become even more important as a due diligence tool: investors expected them to be more detailed and exhaustive than before in order to better support investment decisions and to also ensure that projects would be considered ‘bankable’.

When a risk such as a climate-related risk is identified, it is typically integrated by adding an extra cost to the project. As a result, projects had become more costly, and one interviewee suggested that mitigating physical risks may account for up to 10%–15% of project costs (Interview CI3). But this might still undervalue the risk, since many investors only come in when the project is close to construction; moreover, they have a short-term focus so often do not consider overall sustainability of the project over its whole lifetime (Interview PFI2).

Concern over the increased likelihood of extreme weather events has also led many project developers and investors to look at options for insurance. One respondent explained the preference of investors to spread insurance exposure among a number of reinsurers across the region (Interview IC1). Although insurance could be used for new technologies, in geographical areas subject to extreme events, such as typhoons, it is now difficult to get insurance at an affordable rate (Booth, Citation2018; Neslen, Citation2019).

For both investment and insurance decisions, respondents highlighted the growing importance of using climate data to better understand climate-related risks. One respondent described how the development of a national data platformFootnote1 on meteorology and climatology in the Philippines was being used by project developers to assess, understand, and mitigate climate-related risks that could affect project viability (Interview RI2). They explained that enhanced mitigation measures were adopted by a project developer after reviewing data on weather and storm surges in the national data platform: data from the platform showed that potential storm surges at the proposed plant location were historically between 2.2 and 3.2 metres, but could potentially rise to as high as 5 metres.

4.2. Policy and legal risks

Policy and legal risks refer to the potential establishment of regional and national policies and regulations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which might then adversely affect the value of existing or planned assets. At the national level within ASEAN member states, commitments to reduce emissions from their energy sectors have been outlined in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

A majority of respondents considered policy and regulatory risk to be potentially significant for fossil fuel investments in the power sector, but as of yet this did not seem to be a worry for most investors, for three main reasons. First, no mandatory climate regulations, such as carbon pricing or restrictions on fossil fuel power plants, exist in Southeast Asia. Indeed, there seems to be fairly active government support and funding – through state subsidies and export credit guarantees – which continues to push fossil fuel-based technologies (Interview RI2). Coal is viewed by governments as the only option that can provide cheap, reliable power around the clock (Interview PCF3). Furthermore, export credit agencies from countries such as Japan and South Korea were considered to bear a major responsibility for continued plans for large investments in coal power plants across Southeast Asia, especially in Vietnam and Indonesia, and to a lesser extent in Myanmar (Interview CI2, see also Bengali (Citation2019)).

Second, in nearly all of the Southeast Asian countries, there is an incumbent state-owned utility that controls access to the grid and is pushing back against deregulation of generation and transmission and against open market access (Sen et al., Citation2018). These incumbents, who may be also working to stop or stall regulations to open the market to renewable energy, are usually the same company that will be the offtaker of the electricity from new power plants (Interview DFI2). One respondent (Interview CI4) noted that, without long-term plans to phase out fossil fuels and mechanisms to help avoid stranded assets, incumbents were ‘very likely to entrench themselves in their position and take a very defensive and not constructive role in the transformation’.

Third, a number of respondents noted that most investors tended to use power purchase agreements (PPAs) to shield themselves from policy and regulatory risk. A PPA forms the contract between the generator and the buyer of the electricity (in many cases the state-owned electric utility) and is the foundational document for nearly any power sector investment. It outlines the terms and conditions under which the power plant will get paid and lenders will get repaid. What makes a project bankable is the certainty of repayment, and the PPA is often long-term – e.g. 15 or 20 years – offering certainty of revenue. Lenders typically look at how soon the capital investment into a power plant can be repaid, and whether this matches with the term of the PPA (Interview CI2). Rather than integrating policy and legal risks holistically within the decision-making process, the strategy to deal with these risks was often to secure a PPA that shifted liability for any future changes to the state-owned utility (Interview CI4). Meanwhile, PPAs for renewable energy projects often get much less protection. For example, the recently issued PPA associated with the solar PV feed-in tariff in Vietnam is not considered investor-friendly because it has none of the standard protections that would be required by international banks and investors in order to finance a project (Interview DFI2).

At the same time, there do appear to be some instances of investors and project developers diversifying away from fossil fuels as part of a long-term strategy for firms to balance their portfolios to minimize risk from climate regulation in the distant future (Interviews CI5, DFI2). For example, Banpu Public Company, an incumbent independent power producer (IPP) in Thailand with a regional coal business, has begun to diversify its energy portfolio as part of its corporate strategy to align with global trends towards greater investment in renewables, albeit whilst retaining significant fossil fuel assets (Interview RI1; Praiwan, Citation2019; Setboonsarng, Citation2017).

4.3. Technology and market risks

Technology and market risks associated with climate change include the falling costs of new low-carbon technologies, changing consumer preferences and increasing costs of raw materials, all of which are bringing about major changes in the technology and market landscape. These changes will make fossil fuel investments less competitive and more expensive in the long-run (Bond, Citation2018), with incumbent companies having to rethink their business models and invest in new low-carbon technology.

Despite the disruptive power of renewables, which have already gained significant investment in Southeast Asia, respondents generally agreed that the power market structure in the region limits the speed at which technology and market changes will occur in the future (Interview CI4). For example, Indonesia’s vertically integrated and fully state-owned utility, PLN, has a relatively young fossil fuel asset base and a national grid designed to cater to dispatch large baseload power plants through high voltage lines to demand centres often located far away from generation sites. Transforming such a physically and institutionally embedded power system will be a slow and awkward process. The technology already exists, but it will not be until regulation and incentives are put in place that the power market becomes more decentralized (Interview RI1).

In addition, energy investors ‘have a habit of investing into certain types of power assets, and it’s what they know how to do’ (Interview CI3). Renewable energy projects carry the stigma for many investors of being small-scale and riskier compared to large coal power plants. And since most renewable energy project costs are upfront, investors have to lock-in capital expenditures in the earlier years and only receive returns a few years into the investment cycle (Interview PCF2). Hence investors with experience in fossil fuels tend to feel more comfortable continuing to invest in that space.

Investors and project developers in Southeast Asia’s power sector also seek to mitigate against technology and market risks through conditions set out in PPAs, which lock in the price paid to the generator over a long period (Interview CI2). This is similar to how PPAs are used to mitigate against policy and regulatory risks. In nearly all PPAs in ASEAN countries, the offtaker – usually state-owned utilities – takes 100% of the risk of changes in fuel costs, and the investor or operator of the power plant is compensated for any changes in fuel costs via a pass-through payment. By contrast, in Europe and many locations in the US, the investor or operator of a power plant takes the risk of changing fuel costs.

It would have a significant impact on investment in coal power plants in ASEAN if governments and utilities in ASEAN were to make such a change in their PPA agreements. The status quo in ASEAN markets is that the owners of fossil fuel assets are very well protected, and all risks are shifted to the offtaker and their customers, who may need to pay higher prices.

4.4. Reputational risks

Reputational risks refer to the likelihood of increasing investor commitment and public pressure to take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, leading to reduced interest in owning existing, or financing new, fossil fuel power generation assets. According to our respondents, reputational risk was not a major driver of investment trends in Southeast Asian energy markets. Compared to Western countries, public awareness campaigns were not so prevalent and energy firms were owned by family conglomerates less concerned with reputation than publicly listed companies might be (Interview CI4).

However, pressure to divest does appear to be working indirectly in Southeast Asian energy markets through global corporate procurement requirements for green energy. According to two respondents, while there is limited awareness of climate-related risks to equities among local or regional equity investors, there is much greater awareness in international asset management firms (Interviews CI4, IO2). Corporate buyers in these firms are becoming part of a green investment lobby for renewable energy regulations in several Southeast Asian countries. For example, in 2016 the Norwegian Central Bank divested between nine and ten billion US dollars of global pension fund investments from 52 companies that included coal as a significant part of their business activities, including investments in Aboitiz Power, a major IPP in the Philippines (Power Philippines, Citation2016; Zillman, Citation2016).Footnote2 According to one respondent, that decision has influenced other IPPs in the country to take steps to diversify their investments into renewable energy projects, some of which were located overseas because suitable investments in the Philippines could not be identified (Interview RI2).

4.5. Stranded assets

Transition risks raise serious concerns over stranding of fossil fuel assets in Southeast Asia. Nearly all of the respondents (14 out of 17) indicated that stranded assets were a serious risk, and that they could have a significant impact on the balance sheet of companies, as well as on government budgets, in the next 20 years. With the price of coal generation stable or increasing, and the price of renewable energy and storage decreasing, and with natural gas available in many countries, there could be a significant economic price to be paid for commitments to coal power plants over the next 10–20 years (Interview CI2).

Already, the Philippines has an estimated 10GW of planned coal assets worth US$ 21 billion at risk of being stranded in the future (Ahmed & Logarta, Citation2017). As retail competition has enabled manufacturers and other large customers to seek the cheapest power options, utilities have started to see reductions in the utilization rates of their current coal power plants to below the break-even rate required to be able to service debt, let alone repay their loans. Either the cost will be passed onto consumers, or new PPAs will be issued, and the risk will be transferred back to the investors. Meanwhile, stranded coal assets in India provide a stark lesson for neighbouring Southeast Asia. By 2018, around US$ 40 billion of coal investments in India were considered non-performing assets,Footnote3 causing severe financial stress within the Indian banking sector (Buckley et al., Citation2019). These non-performing assets in the Indian power sector, arising due to a combination of factors including cancelled coal mining concessions, aggressive bidding, lack of PPAs, delays in land acquisition and poor infrastructure, amounted to 40.1GW of coal power capacity, of which 15.7GW were not even commissioned (Buckley & Shah, Citation2018; Sharma et al., Citation2018).

Both the Philippines and India have a liberalized power market with competition in both generation and distribution. For other Southeast Asian countries with more vertically integrated and state-dominated power markets, stranded assets might be considered as less of an immediate threat; there appears to be little serious discussion among Southeast Asian policymakers about the extent of the stranded asset risk, or how to manage it (Interview RI1). Indeed, many respondents appeared confident that, in such countries, incumbent utilities and their government allies would be able to manage the potential threat from stranded assets, at least over the next few years.

5. Discussion

While the physical risks of climate change are becoming increasingly apparent and inform investment decision-making to some extent, transition risks seem to receive limited attention in investment decisions among local and regional investors in Southeast Asia. Even when these risks do receive attention, there are a range of institutional factors that make it challenging or unwise to act upon them. In this section, we reflect on three factors that help to explain the limited awareness and impact of climate-related risks on investment decision-making in the Southeast Asia power sector: established routines and mindsets, pressure to commit large sums through recognized investment channels, and limited consideration of climate-related risk in financial governance mechanisms.

5.1. The force of established routines and mindsets

One major factor that explains the limited incorporation of climate-related risks in investor decision-making in Southeast Asia’s power sector is dominance of established routines used for assessing investment risk, echoing findings of Silver (Citation2017) and Riedl (Citation2020). The financial models that Southeast Asian investors rely upon to determine risk profiles typically take a very static view of risks and are unable to account for dynamic conditions related to a changing climate, or changing policy and regulatory space due to climate change. In addition, investors tend to adopt an approach toward risk that does not focus on analyzing the fundamentals of a company, but rather go by the ratings of expected returns based on historical trends. They then rely on ‘repayment’ mechanisms and sovereign guarantees to mitigate risk. As a result of these established routines, local and regional investors are typically unaware of, or place very low importance on, climate-related risks, despite potentially having significant exposure to them.

As such, when then comparing traditional fossil fuel investment options against ‘new’ renewable energy investments, the latter are viewed as considerably riskier and more work to understand. Many power sector investors in Southeast Asia typically believe that the ‘green’ energy sector provides lower returns than traditional investments, and therefore they tend to ignore the risks increasingly inherent in traditional fossil fuel investments in order to achieve perceived higher investment returns. This mindset that ‘green’ investments are risky and historically offer low returns was forged in an era when grid-scale renewable energy was in the early stages of its development in the region. This skewed risk comparison between fossil fuel and renewable energy investments is further skewed by experience with PPAs for large-scale fossil fuel projects, which have allowed risks to be passed on to the offtaker and consumers.

5.2. Pressure to spend large sums through recognized channels

Another factor driving investment into large-scale fossil fuel projects rather than smaller-scale renewable power is the need to deploy large amounts of capital relatively quickly. Many investors holding large portfolios face considerable pressure to find projects that are large enough to absorb the funds they have to invest and with which they have plenty of experience. This means they look for familiar investment vehicles that do not take them out of their comfort zone or require additional due diligence.

Similarly, entrenched utility monopolies do not appear to see climate-related risks as something they need to pay attention to right now in their investment decision-making. Their assets and expertise often lie in fossil-fuel-related technologies and systems, and this makes it difficult to shift organizational focus. This has a knock-on effect for investors who are looking for a capable and reliable offtaker for their power over a 10–20-year period. While awareness of climate-related risks in utility investments is gradually increasing, it is not yet causing enough concern to stimulate widespread shifts.

Respondents also pointed out that it is important to distinguish between investors looking for short-term returns and those holding longer-term investments. Short-term investors have an investment cycle of five to ten years, thus they pay little attention to longer-term climate-related risks, even if the overall performing life of the asset they invest in might be 20 or 30 years. This is also noted by Setterberg et al. (Citation2019) in their research on long-term perspectives in investment analysis in Sweden.

5.3. Limited consideration of climate-related risk in financial governance mechanisms

A third factor was the limited consideration of climate-related risk in financial governance mechanisms within most countries in the region. In the investment market today, there exist a wide range of international and company-specific standards that aim to integrate ethical imperatives such as sustainability into investment allocation. Typically, these were seen by respondents as having created a general negative bias towards certain sectors that carry climate-related risks such as the coal power-sector. Yet respondents noted several shortcomings within this area. For example, such standards may focus on specific metrics such as carbon intensity, rather than on integrating sustainability in a holistic manner. Notably, respondents explained that such frameworks are not designed to meet the needs of smaller-scale projects.

Moreover, respondents pointed out that investors exercise a problematically wide margin of decision-making around these standards – notably in choosing to apply an ‘environmental and social governance-lite’ version of a standard. The lack of commitment on the part of investors to little more than surface compliance with investment standards appears to be one of the reasons behind the lack of integration of climate-related risks.

Respondents stated that, despite progress being made by many financial institutions in integrating climate-related risk into their investment decision-making, it is still common for strategic investments to be made in the power sector without any such consideration. Although many banks may have stopped lending for fossil fuel power plants, these still get built because of strategic equity investors who choose to ignore climate-related risks. Hence the overwhelming impression from interviews was that the integration of climate-related risks into investment decisions does in fact require deeper changes in the governance of investment decision-making.

It appears clear that there is a need to improve the standards used to integrate climate-related risk in investment decision-making, but the question remains over the extent to which these standards should be mandated through some regulatory mechanism. Recent studies on incorporating climate-related risk in investments in Europe warn against placing the burden squarely on central banks to regulate standards: they might play a coordinating role, but action must come from multiple actors within the financial system (see Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Citation2020; Bolton et al., Citation2020).

6. Conclusions

This paper has analyzed awareness and understanding of climate-related risk related to the power sector in Southeast Asia, and the impacts of such risks on investment decision-making in the sector. Overall, the results from our analysis suggest that there is currently a significant gap between the need to integrate climate-related risks within investor decision-making and the way these risks are currently being integrated and addressed in the Southeast Asia power sector.

The interviews reveal that climate-related risk is either not a significant factor, ignored in light of other concerns, or is only superficially integrated into decision-making. Our research highlights how routines and mindsets, pressure to invest large sums and limited focus of financial governance mechanisms all contribute to inadequate consideration of climate-related risks. Whilst this echoes much of what has been found in the broader literature on limited inclusion of climate-related risk in investment, we also find some regional aspects highlighting why the shift remains so slow in the region. These aspects include the structure of Southeast Asia’s power sector, where a state-owned single buyer monopoly dominates, and a propensity for PPAs designed in such a way that asset stranding is considered to be a minimal threat.

Our findings are based on interviews with 17 respondents, only 6 of which were investors. As such, we do not consider our findings to be fully representative of power sector investors in the region. However, we believe they still offer important insights for research and policy. Our research highlights the urgent need for action from governments, financial regulators and energy sector associations targeted at power sector investors in order to shed light on climate-related risks, share information on the likelihood and magnitude of risks, lay out clearly the potential for stranded assets in a 10–15-year time frame. We also highlight a need to encourage transparent, open and respectful dialogue and discussion on these critical issues.

To start with, we recommend gathering better data and developing more refined analytical tools to quantify climate-related risks and their impacts, building on the work of TCFD. Meanwhile, important policy and regulatory action is needed to address the influence of major incumbent players in decision making in order to open opportunities to shift investment patterns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The platform is PAGASA – the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (bagong.pagasa.dost.gov.ph).

2 The list included 22 firms from the US, seven each from China and India, three from Japan, two each from Australia, Canada, Chile, and Hong Kong, and one each from Greece, Poland, South Africa and the Philippines.

3 A non-performing asset (NPA) is a loan or an advance where interest on and/or repayments of the principal remain overdue for a period of more than 90 days in respect of the term of the loan. An asset, including a leased asset, becomes non-performing when it ceases to generate income for the bank. See: http://164.100.47.193/lsscommittee/Energy/16_Energy_37.pdf.

References

- AES. (2018). AES announces carbon intensity reduction of 70 percent by 2030. Publishes Climate Scenario Report [WWW Document]. Retrieved June 1, 20, from http://www.aes.com/investors/press-releases/press-release-details/2018/AES-Announces-Carbon-Intensity-Reduction-of-70-Percent-by-2030-Publishes-Climate-Scenario-Report/default.aspx

- Ahmed, S. J., & Logarta, J. (2017). Carving out coal in the Philippines: Stranded coal plant assets and the energy transition. IEEFA and Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities, Manila, Philippines.

- ASEAN Centre for Energy. (2015). ASEAN plan of action for energy cooperation (APAEC) 2016–2025.

- Baker, A. (2016). Engie to accelerate divestment from coal, merchant plants [WWW Document]. BNamericas.com. Retrieved June 1, 20. https://www.bnamericas.com/en/news/engie-to-accelerate-divestment-from-coal-merchant-plants

- Baker, H. K., Filbeck, G., & Ricciardi, V. (2017). How behavioural biases affect finance professionals. The European Financial Review. Retieved June 1, 20, from https://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/how-behavioural-biases-affect-finance-professionals/, https://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/how-behavioural-biases-affect-finance-professionals/

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2020). Climate-related financial risks: A survey on current initiatives. Bank for International Settlements.

- Bender, J., Bridges, T. A., & Shah, K. (2019). Reinventing climate investing: Building equity portfolios for climate risk mitigation and adaptation. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 9(3), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2019.1579512

- Bengali, S. (2019). China, Japan and South Korea, while vowing to go green at home, promote coal abroad. Los Angel. Times.

- Bolton, P., Despres, M., Pereira da Silva, L. A., Svartzman, R., Samama, F., & Bank for International Settlements. (2020). The green swan: central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change.

- Bond, K. (2018). Why you should see peak fossil fuels coming. Carbon Tracker.

- Booth, K. (2018). Profiteering from disaster: Why planners need to be paying more attention to insurance. Planning Practice & Research, 33(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2018.1430458

- Bos, K., & Gupta, J. (2019). Stranded assets and stranded resources: Implications for climate change mitigation and global sustainable development. Energy Research & Social Science, 56, 101215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.025

- Buckley, T. (2019). Over 100 global financial institutions are exiting coal, with more to come. Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

- Buckley, T., & Shah, K. (2018). IEEFA update: India coal plant cancellations are coming faster than expected. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://ieefa.org/india-coal-plant-cancellations-are-coming-faster-than-expected/

- Buckley, T., Shah, K., Garg, V., & Nicholas, S. (2019). IEEFA report: India’s stranded asset risk in thermal power sector underestimated. Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis, Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://ieefa.org/ieefa-report-indias-stranded-asset-risk-in-thermal-power-sector-underestimated/

- Buhr, B. (2017). Assessing the sources of stranded asset risk: A proposed framework. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 7(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2016.1194686

- Burger, M., & Wentz, J. (2018). Holding fossil fuel companies accountable for their contribution to climate change: Where does the law stand? Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 74(6), 397–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2018.1533217

- Byrd, J., & Cooperman, E. S. (2018). Investors and stranded asset risk: Evidence from shareholder responses to carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) events. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 8(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2017.1418063

- Caldecott, B. (2017). Introduction to special issue: Stranded assets and the environment. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2016.1266748

- Campiglio, E., Dafermos, Y., Monnin, P., Ryan-Collins, J., Schotten, G., & Tanaka, M. (2018). Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0175-0

- Clapp, C., Lund, H. F., Aamaas, B., & Lannoo, E. (2017). Shades of Climate risk: Categorizing climate risk for investors (Report 2017-01). CICERO.

- Dietz, S., Bowen, A., Dixon, C., & Gradwell, P. (2016). ‘Climate value at risk’ of global financial assets. Nature Climate Change, 6(7), 676–679. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2972

- Eco-Business Research. (2018). Power trip: Southeast Asia’s journey to a low carbon economy. Eco-Business.

- Environmental Finance. (2018). AP4 pension fund divests from 22 coal companies. https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/news/ap4-pension-fund-divests-from-22-coal-companies.html

- Ganguly, G., Setzer, J., & Heyvaert, V. (2018). If at first you don’t succeed: Suing corporations for climate change. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 38(4), 841–868. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqy029

- Hirshleifer, D. (2015). Behavioral finance. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 7(1), 133–159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-092214-043752

- IEA. (2017). Southeast Asia energy outlook 2017. OECD/IEA.

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014 – Synthesis report: Annex II. UNFCCC.

- Koh, J. M. (2018). Green infrastructure financing. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71770-8

- Mayo, H. B. (2019). Investments: An introduction. Cengage Learning.

- Mercure, J.-F., Pollitt, H., Viñuales, J. E., Edwards, N. R., Holden, P. B., Chewpreecha, U., Salas, P., Sognnaes, I., Lam, A., & Knobloch, F. (2018). Macroeconomic impact of stranded fossil fuel assets. Nature Climate Change, 8(7), 588–593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0182-1

- Murtaugh, D. (2020). Banks shunning coal financing bodes badly for new plants in Asia. Bloomberg.com.

- Neslen, A. (2019). Climate change could make insurance too expensive for most people – report. The Guardian.

- Partington, R. (2019). Mark Carney tells global banks they cannot ignore climate change dangers. The Guardian.

- Piggot, G. (2018). The influence of social movements on policies that constrain fossil fuel supply. Climate Policy, 18(7), 942–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1394255

- Power Philippines. (2016). Aboitiz Power among 52 firms excluded from Norway bank fund [WWW Document]. Power Philipp. News, https://powerphilippines.com/2016/07/11/aboitizpower-among-52-firms-excluded-norway-bank-fund/

- Praiwan, Y. (2019). Banpu allots $835 m in shift. Bangk. Post.

- REN21. (2019). Renewables 2019 global status report.

- Riedl, D. (2020). Why market actors fuel the carbon bubble. The agency, governance, and incentive problems that distort corporate climate risk management. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2020.1769986

- SASB. (2018). Climate risk: From principles to practice. (Phase 1: SASB, CDSB, and TCFD Converge on a global approach to a global Challenge). Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB).

- Scott Cato, M., & Fletcher, C. (2019). Introducing sell-by dates for stranded assets: Ensuring an orderly transition to a sustainable economy. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2019.1687206

- Sembcorp. (2018). Sembcorp launches new Climate Change Strategy. https://www.sembcorp.com/en/media/media-releases/corporate/2018/march/sembcorp-launches-new-climate-change-strategy/

- Sen, A., Nepal, R., & Jamasb, T. (2018). Have model, will Reform? Assessing the outcome of Electricity Reforms in Non-OECD Asia. The Energy Journal, 39. https://doi.org/10.5547/01956574.39.4.asen

- Setboonsarng, C. (2017). Thai Banpu power looks to diversify beyond coal. Reuters.

- Setterberg, H., Sjöström, E., & Vulturius, G. (2019). Long-term perspectives in investment analysis. Stockholm Sustainable Finance Centre.

- Sharma, S. N., Layak, S., & Kalesh, B. (2018). How India’s power story derailed, blowing a Rs 1.74 lakh crore NPA hole Read more at. //economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/65822950.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst. Econ. Times

- Silver, N. (2017). Blindness to risk: Why institutional investors ignore the risk of stranded assets. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 7(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2016.1207996

- TCFD. (2017). Final report: Recommendations of the task force on climate-related financial disclosures. Task force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

- TCFD. (2019). Task force on climate-related financial disclosures: Status report (2019 status report). Task force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

- Thomä, J., & Chenet, H. (2017). Transition risks and market failure: A theoretical discourse on why financial models and economic agents may misprice risk related to the transition to a low-carbon economy. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 7(1), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2016.1204847

- Thomä, J., Murray, C., Jerosch-Herold, V., & Magdanz, J. (2019). Do you manage what you measure? Investor views on the question of climate actions with empirical results from the Swiss pension fund and insurance sector. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2019.1673142

- Tong, D., Zhang, Q., Zheng, Y., Caldeira, K., Shearer, C., Hong, C., Qin, Y., & Davis, S. J. (2019). Committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure jeopardize 1.5°C climate target. Nature, 572(7769), 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1364-3

- University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership and PwC. (2016). Closing the Protection Gap: ClimateWise Principles Independent review 2016. ClimateWise.

- Zhou, W., McCollum, D. L., Fricko, O., Fujimori, S., Gidden, M., Guo, F., Hasegawa, T., Huang, H., Huppmann, D., Krey, V., Liu, C., Parkinson, S., Riahi, K., Rafaj, P., Schoepp, W., Yang, F., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Decarbonization pathways and energy investment needs for developing Asia in line with ‘well below’ 2°C. Climate Policy, 20(2), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1722606

- Zillman, C. (2016). These companies just got banned from the world’s biggest wealth fund. Retrieved June 1, 20, from https://fortune.com/2016/04/18/coal-divestment-norway-wealth-fund/