ABSTRACT

This paper empirically evaluates how policy to mobilize climate finance works in practice. It examines the performance of nine types of climate finance policies, namely target lending, green bond policy, loan guarantee programmes, weather indexed insurance, feed-in-tariffs, tax credits, national development banks, disclosure policies and national climate funds, through a literature review and case studies. Both successful and unsuccessful country cases are examined. Criteria are established to evaluate climate finance policy, factors which lead to effective climate finance policy in practice are identified, current knowledge gaps are clarified, and policy implications provided.

Key Policy insights

The effectiveness of climate finance policies depends on the criteria being used.

Strengths and weaknesses exist for each of the climate finance policies.

Feed-in tariffs, tax credits, loan guarantees, and national development banks are all effective at mobilizing private finance, but evidence to date is weak or thin on the effectiveness of national climate funds, targeted lending, disclosure, and green bonds.

Significant data and research gaps exist regarding the empirical impacts of climate finance policies, especially their environmental and equity impacts.

In selecting climate finance policies, a balance should be struck between mobilization effectiveness, economic efficiency, environmental integrity, and equity.

1. Introduction

Finance has a critical role to play in enabling a transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient economy. The Paris Agreement itself commits to aligning financial flows ‘with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development’ (Article 2.1(c)). Numerous studies have established that a substantial financial gap exists to meet these goals (Buchner et al., Citation2019; IPCC, Citation2018; UNCTAD, Citation2014). A recent estimate of adaptation needs, for example, identified $1.8 trillion in potential investments that would result in $7.1 trillion in benefits (Global Commission on Adaptation, Citation2019), yet the latest estimates only identify $30 billion in adaptation investments (Buchner et al., Citation2019). To fix these financial gaps, more effectively mobilizing and steering public and private finance to climate-related purposes is of critical importance.

Multiple barriers have impeded the mobilization of private finance to address climate change, including the lack of quantifiable incentives, the unwillingness of most for-profit firms to internalize environmental externalities, low or intangible returns to corporate social responsibility practices, perceptions of high risks of low-carbon technologies on the part of commercial banks and other mainstream financiers, a mismatch between long-term payback periods and the short-term horizons of most private investors, lack of information to evaluate projects and their climate-related consequences, and a shortage of bankable low carbon, adaptation, and resilience projects (Chawla & Ghosh, Citation2019; Jaffe et al., Citation2005; Leete et al., Citation2013; Pillay et al., Citation2017; Polzin, Citation2017; Wilson et al., Citation2012). There are also political, institutional, and legal barriers to private investments, which may be even more profound. These barriers may be further magnified when policy coordination is lacking.

Some governments have begun to implement new policies to mobilize climate finance, accelerate decarbonization, and improve adaptation and resilience to climate change impacts. Although there are numerous conceptual models for how climate finance could work and what kinds of climate finance can be useful, no empirical assessment has yet been conducted about how climate finance policies work in practice (Bowen, Citation2011; Haites, Citation2016; Romani & Stern, Citation2016). To address this gap, this paper reviews the evidence regarding climate finance policies that have already been implemented around the world, with the objective of harvesting early lessons about how these policies have actually worked in practice. Specifically, the paper explores which climate finance policies work, which do not, and under what conditions certain policies appear to work better.

This paper contributes to the extant scholarly literature in two ways. First, it investigates the empirical efficacy of climate finance policies based on a comprehensive set of assessment criteria. Second, the paper analyzes climate finance policies at the national level and draws on policy experiences from both successful and unsuccessful country cases. Much of the climate finance literature has focused on estimating financing needs (Buchner et al., Citation2019; Flåm & Skjaerseth, Citation2009; IPCC, Citation2018; McKinsey & Company, Citation2009; Olbrisch et al., Citation2011; UNCTAD, Citation2014) or tracking progress on addressing this issue in international climate negotiations (Persson et al., Citation2009; Roberts et al., Citation2010; Roberts & Weikmans, Citation2017). There is substantial existing scholarly work on climate finance at the firm level or international organization level (Haites, Citation2011). The academic literature on climate finance policies is limited, however, and, where it exists, the focus is on policies to address the North–South climate finance gap or policy analysis based on economic modelling (Bowen, Citation2011; Bowen et al., Citation2017; Grubb, Citation2011; Brahmbhatt & Steer, Citation2016; Grubb, Citation2011; Matsuo & Schmidt, Citation2017; Stewart et al., Citation2009).

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology and data. Section 3 provides the major results, including a taxonomy of climate finance policies and evaluation of the nine climate finance policies by using a set of criteria. Section 4 presents a discussion and highlights knowledge gaps. Conclusions and policy implications are in Section 5.

2. Methodology and data collection

2.1. Policy case selections

To analyze what works, what doesn't, and why in climate finance policy, we first develop a taxonomy of climate finance policies as shown in Section 3.1. We select nine types of climate finance policies to evaluate in more detail as shown in . These are included to illustrate the roles the policies play in stimulating the demand and supply for finance. Different policies also serve different functions, as depicted in . In addition, we chose both economy-wide policies and as well as policies related to specific sectors, such as clean energy, energy efficiency, and adaptation. While there are multiple policies that could meet all the above criteria, we ultimately selected the policies with a substantial historical record, those with available data, and those policies implemented in multiple jurisdictions to enable us to conduct comparative analysis for our policy evaluation.

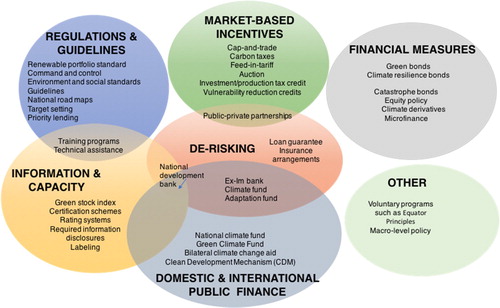

Figure 1. Classification of climate finance policies based on function. Source: Adapted from Gallagher and Xuan (Citation2018).

Table 1. Selected policies and country experience.

Two caveats are necessary. First, the evidence base varies for the policies, in part because some policies have longer track records of implementation while others were recently implemented. For example, tax credits have much longer histories than do green bonds. While our literature review was based on existing scholarship, certain gaps in the literature were addressed through supplemental field research in a few countries. The countries selected had implemented multiple climate finance policies and so were efficient cases for field work. Still, it was not practically possible to conduct field work in every country where these policies have been implemented. Furthermore, we found that a number of policies already implemented have never been independently studied. For example, the scholarship on loan guarantee programmes is surprisingly thin despite being employed for decades and, more recently in the United States (US) at very large scale. While we acknowledge an ‘availability bias’ in the selection of policies under study, we also note a different type of potential bias, namely that some policies have received much more scholarly attention than others perhaps because they are perceived as successful.

Methodologically, we reviewed all existing peer-reviewed publications that examine the impact of different climate finance policies in practice (a list of key scholarly articles about each policy is in Appendix A). Most of the articles reviewed were published between 2010 and 2020, reflecting the fact that many climate finance policies are relatively new. We typed the names of the policy instruments in as key words to search for relevant research through Google Scholar. For policy names, we used the full names of the instruments and their acronyms (such as FiT and NDBs). We also allowed for some variations in the exact terms used. For instance, we used both loan guarantee programmes and loan guarantee policy/policies. We also used both weather indexed insurance and weather index-based insurance. We focused on papers that were explicitly focused on investment or finance. The literature review prioritizes peer reviewed scholarship, but also includes think tank reports and government documents. Our review of the available literature is complemented by primary research in some countries (as well as multilateral institutions) on certain policy instruments included in this paper (a brief description of country experiences under each policy is in Appendix B). The extent of available evidence is also influenced by which countries could be included in this analysis. Field research was conducted in the US, China, India, Germany, Ethiopia, Brazil, Indonesia, and Bangladesh in 2018–19 (information about the 180 interviews conducted is in Appendix C). The interviewees were key stakeholders involved in climate finance projects in these countries, including policy makers, bankers, investors, consultants, NGO officials, and experts. For example, while there is some scholarship on the Amazon Fund or KfW, the German development bank, interviews allowed us to draw more detailed insights. Based on these primary and secondary sources, we evaluate the efficacy of the nine climate finance policies using an explicit set of criteria for assessment.

2.2. Qualitative evaluation framework

Climate finance has been evaluated in the literature in terms of its contribution to policy goals, to what extent the policy alters the behavior of financiers, or how much finance is mobilized (van Rooijen & van Wees, Citation2006). Earlier scholarship mainly focused on individual criteria to evaluate a specific policy instrument, including mobilization effectiveness (van Rooijen & van Wees, Citation2006), economic efficiencies (Butler & Neuhoff, Citation2008; Clò et al., Citation2015), attractiveness to investors (Polzin et al., Citation2015), distributional impacts on consumers (Grösche & Schröder, Citation2014; Pirnia et al., Citation2011), or other co-benefits (e.g. employment or innovation) (Zhu et al., Citation2019). When focusing on one criterion, however, other important dimensions of climate finance implementation are often intentionally or unintentionally neglected. We address this gap in the literature by bringing together multiple dimensions of policy implementation within a single framework.

We propose a more comprehensive set of criteria to evaluate the selected policy instruments based on the literature cited above (see ), including: (1) mobilization effectiveness in terms of the volume of finance mobilized and to what extent long-term or cheaper finance has been leveraged, (2) economic efficiency, which refers to the cost-effectiveness of the specific policy to shape financial mobilization, (3) environmental integrity (whether the policy leads to real and verifiable emission reductions or improved adaptation capacity); and (4) equity, which refers to whether the policy enables equal access to finance among different stakeholders. The paper does not include other co-benefits, such as innovation and employment into the set of evaluation criteria as these impacts are the outcomes of finance mobilized by climate finance policies rather than the direct goals of climate finance policies.

Table 2. Criteria for evaluating climate finance policy.

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomies of climate finance policies and the empirical applications

We define climate finance policies as those policies that aim to mobilize finance for climate-related objectives including mitigation of greenhouse gases, adaptation to climate change impacts, and creation of longer-term resiliency to climate disruption. Climate finance policies can be broadly grouped into three types based on market intervention points, namely demand-side policies, supply-side policies, and linkage policies as shown in Appendix D.

We further categorize climate finance policies based on the functions of climate finance policies and the incentive mechanisms embedded in these policies as depicted in . The main types of climate finance policies are de-risking, regulations and guidelines, market-based incentives, financial measures, information & capacity, domestic and international public finance, and other. Some policies fit into more than one of these categories, and these are depicted in the overlapping circles in the Venn diagram in .

Based on the taxonomies, we select nine types of climate finance policies to analyze in this paper as shown in in Section 2.1. The objectives, barriers, and risks mitigated by the policies are available in Appendix E.

3.2. Effectiveness of climate finance policies in practice

This section evaluates the climate finance policy instruments against the four criteria proposed above. Each criterion is examined in turn, and then all of the policies are rated against the criteria in .

Table 3. Comprehensive assessment and rating of climate finance policy in practice.

3.2.1. Mobilization effectiveness

Among the nine policy types, there is more consensus on the effectiveness of FiT and NDBs in mobilizing climate mitigation finance relative to the other policies. This is not to say that FiT are necessarily the best policy tool for achieving the highest rates of installed renewable electricity capacity. FiT for renewable energy in electric power, even though they are concentrated in a single sector, have been studied the most (Couture & Gagnon, Citation2010). Surveys show that FiT are the favoured policy for most investors, including institutional investors (Polzin et al., Citation2015) and venture capitalists. FiT are also preferred by investors when it comes to immature technologies.

NDBs have tools at their disposal that can alter the behavior of other financial institutions or investors. NDBs not only have directly provided concessional finance to firms, but can also leverage more private finance through de-risking and learning spillovers by helping new entrants build track records, or even creating markets that didn't exist before (Geddes et al., Citation2018; Mazzucato & Penna, Citation2016). National climate funds have primarily provided grants to sectoral ministries as well as NGOs. Such grants have also been used in larger blended finance packages to make clean energy technologies more affordable to local communities.

Green bond policies and guidelines have contributed to the emergence of a vibrant green bond market in a number of countries and a correspondingly rapid growth in the volume of climate finance. But whether the green bond market has actually reduced the cost of capital for climate change projects remains disputed. Some emerging studies argue that green bonds can be equally or more competitive than traditional bonds (Partridge & Medda, Citation2018) while others observe a negative premium for green bonds (Shishlov et al., Citation2016; Zerbib, Citation2016).

The impact of climate disclosure policies appears to be mixed. Some studies find that disclosure helps by lowering the cost of capital or equity (Li et al., Citation2017; Maaloul, Citation2018), while others find that emissions intensity is positively correlated with a higher cost of debt (Kumar & Firoz, Citation2018). In China, private companies have faced a higher cost of debt than state owned enterprises for the same level of climate risk (Zhou et al., Citation2018). Carbon disclosure could negatively impact shareholder value as investors believe such information is bad news about the company (Lee et al., Citation2015) but in the longer term, disclosure may motivate firms to actively invest in cleaner projects. Others have found that regular or irregular reporting does not affect share prices, but when companies in environmentally intensive industries report frequently, it can affect share price volatility (Bimha & Nhamo, Citation2017). In contrast, Lee et al. (Citation2015) find that firms can mitigate share price volatility through frequent reporting.

Much less scholarly literature exists on the mobilization effectiveness of loan guarantee and priority lending programmes. In the US Department of Energy (DOE)'s loan guarantee programme, $35.7 billion in loans and loan guarantees were issued, with $2.69 billion in interest paid and only $810 million in losses as of June 2019 (Department of Energy, Citation2019a)). According to the DOE's loan programme office, the programme ‘continues to attract private investment’, and between 2017 and 2018, nine projects were acquired either on the open market or via private placement, which in turn ‘incentivizes developers to allocate capital to new projects’ (Department of Energy, Citation2019b). Loan guarantees were also found to be useful in increasing the uptake of off-grid rural energy (Shi et al., Citation2016). One concern raised early in the history of the US loan guarantee programme was that loan repayment obligations could actually increase the risks of default for certain projects as loan repayment demands cash flow from early-stage companies at a time when they may already have high cash flow requirements (Brown, Citation2012). However, there is no evidence this actually occurred. The loan guarantee programme may not have encouraged firms to take sufficient risk from an innovation point of view, and therefore may also not have leveraged new and additional finance, but without a rigorous, independent, assessment it is not possible to determine either way.

The relationship between the efficacy of targeted lending and financial mobilization is not well established. Some even dispute whether or not targeted lending policies should be used, but analysts are highly constrained by lack of data. Furthermore, there is the risk of how priority lending policies that require exposure to sectors like agriculture may in fact lead to higher risks for the financial system as a whole. Some banks in India prefer to save their money in public funds rather than risk losing money by lending to renewable energy producers.Footnote1 Bai (Citation2011) argues that bank lending to energy-intensive and high-pollution projects within China was effectively restricted due to China's green credit policy as many banks have established their own internal policies and measures for incorporating environmental aspects into current practices. Data does suggest the total green credit lending increased while carbon-intensive and pollution-intensive loan volumes as a percentage of corporate lending declined after the issuance of China's Green Credit Guidelines in 2012 (Ho, Citation2018). Others have argued, however, that the impact of green credit policies is limited by weakness in enforcement capacity, uneven implementation, vague policy guidance, unclear implementing standards, and lack of project-specific data (Zhang et al., Citation2011).

3.2.2. Economic efficiency

The use of public finance to mobilize private investments (often measured by the leverage ratio), and the government's cost of administering the climate finance policy are two ways to measure economic efficiency. In general, it was difficult to find publicly-available data on administrative costs and benefits. There are often three types of costs accompanying a specific policy: the cost of setting up the policy, the cost of funding the subsidy needed to energize and sustain the policy, and the transaction costs, which refer to the additional costs incurred by financiers or investors to take advantage of the policy.

Of the nine polices, FiT and loan guarantee programmes have been most questioned regarding their economic efficiency. A typical critique of FiT is that they lead to higher costs for renewables due to the lack of price competition (Menanteau et al., Citation2003). Butler and Neuhoff (Citation2008), however, argue that the German FiT may have led to cheaper prices paid for wind energy delivered due to greater competition among project developers for good sites (not for prices). Undoubtedly, FiT can cause public costs to accumulate rapidly if the scale of deployment becomes larger than anticipated (Frondel et al., Citation2008). In both Spain and Germany, the increasing cost burden gradually contributed to political resistance to the FiT. Studies have found that increases in generation capacity due to the FiT can lead to a decrease in wholesale electricity prices, although these may not be felt by consumers (Clò et al., Citation2015; Gelabert et al., Citation2011). Similarly, policymakers face the trade-off between a high tariff that guarantees installation targets will be met but at a high production cost, and a low tariff that comes with the uncertainty of how project developers will respond (Drechsler et al., Citation2012). Policy adaptability, therefore, is key.

The empirical evidence about the net cost or benefit of loan guarantee programmes for clean energy is thin. The administrative costs incurred by creating and maintaining new institutions and the transaction costs that may be imposed on the lending and borrowing parties could be a disadvantage, but it is not clear how high these costs actually are (Vogel & Adams, Citation1997). Although the DOE's loan guarantee programme for advanced manufacturing and cleaner energy was controversial in the US due to at least one symbolic and public failure, the overall losses for the portfolio were very low at only 2.91% of disbursements (Department of Energy, Citation2019a). The net benefits have not been calculated, although data do exist about the number of new jobs created and CO2 emissions avoided (available on DOE's loan programme office website). The IFC's experience shows that when loan guarantee programmes are effectively structured, one dollar in Global Environment Facility (GEF) funds can directly leverage $12−15 of commercial investment into energy efficiency projects and indirectly catalyze long term growth of financial commitments to the sector (Maclean et al., Citation2008).

Tax incentives are often easier to administer than other programmes to bolster renewable energy development because the knowledge, systems and government organizations needed already exist (Clement et al., Citation2005). Tax credits can be an expensive policy to maintain for governments. In the US, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that foregone revenues (or ‘tax expenditures’) for the production tax credit (PTC) for renewable energy were $4.8 billion in 2018 (Sherlock, Citation2018). Studies of tax incentive schemes that support retrofit measures for building energy efficiency in the Netherlands and in the US also suggest potentially high free rider rates, indicating that many retrofits would have been pursued in the absence of the support schemes (Neuhoff et al., Citation2012).

There is almost no research on the economic costs or benefits of the other types of climate finance polices, including green bonds, priority lending, NDBs, national climate funds, and information disclosure.

3.2.3. Environmental integrity

The environment integrity of FiT, NDBs, and loan guarantee policies is relatively straightforward, as the sectoral impact of each can be easily measured. Indeed, DOE's loan guarantee programme office reports that nearly 50 million metric tons of CO2 have cumulatively been avoided since 2010 as a result of the programme (DOE, Citation2019b). Policy interactions, however, are an important consideration and may impact overall environmental effectiveness. For example, the ability of FiT programmes in European countries to contribute towards greenhouse gas mitigation was constrained by the regional emissions trading programme (EU ETS) whose targets were not updated frequently enough to reflect the increase in power generation capacity through renewables (Frondel et al., Citation2010).

The environmental integrity of green bonds has been questioned because of the lack of international standardization in green bond instruments (Agarwal & Singh, Citation2017). Which types of projects are allowed to be financed, and whether they are really green or not, makes a big difference to the final environmental outcomes of the use of green bonds (Agarwal & Singh, Citation2017; Chiang, Citation2017; Wood & Grace, Citation2011). A standardized monitoring and evaluation process would reduce controversy and allegations of ‘greenwashing’. As the largest issuer of green bonds, China could do much more to validate the environmental benefit of its green bonds. Current guidelines allow technologies which are not recognized internationally (such as ‘clean coal’ plants) to be eligible for green bonds.Footnote2 In 2017, 38% of China's total issuance of green bonds did not meet international norms for being green (Climate Bonds Initiative, Citation2018). Meanwhile, China allows green bond issuers to use up to 50% (versus only 5% for green bonds according to the Climate Bonds Taxonomy) of bond proceeds to repay bank loans and invest in general working capital, which is not necessarily green (ibid).

National climate funds can help foster greater transparency of policy impact through their support for measurement and reporting. National climate funds, such as the Amazon Fund, have made allocations to projects that improve data gathering and monitoring capabilities. Such investments create a virtuous cycle as the impact of the fund will also be easier to assess. The lack of available data, however, also limits the environmental effectiveness of these funds. In Bangladesh, the lack of data on climate vulnerability raised questions about the judiciousness of the Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund's programmes (Bhandary, Citation2020).

There are doubts about the environmental impacts of the green credit policy in China due to lack of data, especially environment information, and concerns regarding data quality too (Zhang et al., Citation2011). In summary, significant data and research gaps still exist regarding the environmental integrity of disclosure policy instruments.

3.2.4. Equity

There is increasing concern about the equity impacts of climate finance policies, but the existing literature is far from adequate. Of the nine types of policies, there is relatively more evidence about the distributional impact of FiT (Yamamoto, Citation2017). FiT mitigate risks and therefore enable all renewable energy producers to take advantage of them. But in Germany, trade-sensitive and energy-intensive industries were exempted from paying the surcharge that financed the FiT in an effort to avoid harming their international competitiveness. This exemption created some inequity among firms. Pirnia et al. (Citation2011) argue that the Ontario FiT had a very large negative impact on consumer welfare, together with a large transfer of wealth to FiT-eligible producers. Similarly, Grösche and Schröder (Citation2014) found that a levy on consumers, proportional to electricity consumption (and not income), led to the FiT having a regressive effect. Nelson et al. (Citation2011) reached a similar conclusion that wealthier households are beneficiaries under the current FiT for residential photovoltaic solar technologies in Australia and the FiT are generally a regressive form of taxation in most Australian jurisdictions. In addition, FiT may also lead to perverse effects such as undermining the level of competition between energy producers (Frondel et al., Citation2010).

There is far too little evidence about the equity impacts of other climate finance policies. The case studies revealed that big firms were favoured more than small and medium firms in China's green bond market. Under the loan guarantee programme in the US, large and established companies such as Ford were favoured with direct loans rather than only loan guarantees. While risk-based pricing methods would be a sensible suggestion for weather indexed insurance, the equity dimension of charging high insurance premiums to highly vulnerable populations also needs to be considered (Picard, Citation2008).

Tax credits are equally available to all, but one must have a big enough tax burden to take advantage of them. Lower income households or small firms may not have a sufficiently large tax liability to be able to benefit from tax credit policy instruments, so they can be somewhat regressive by primarily conferring benefits to wealthier households and firms. The additionality of tax credits can be questioned for wealthier firms and households as well. In other words, would they have made the purchase or investment anyway?

Distributional concerns have also arisen in the allocations made by national climate funds. Allocations have mirrored existing capabilities. For example, the Bangladesh Water Board alone accounts for 40% of the funds programmed by the Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund. While the use of a national climate fund's resources by well-equipped ministries has helped to increase disbursement rates, it does raise questions about the longer-term capacity building impact of these funds.

3.3. Design features of climate finance policies

Specific aspects of policy design and implementation strongly shape how effective an individual climate finance policy is in practice. Building on earlier work (van Rooijen & van Wees, Citation2006), we identify stability, simplicity, transparency, consistency and coordination, and adaptability as the key features that are crucial for the effectiveness of policies to stimulate financial flows. This section also compares the key features of the nine selected climate finance policies (as shown in ).

Table 4. Comparisons of key features of climate finance policy in practice.

Regarding stability and predictability, the FiT is the leading climate-finance policy instrument because it may secure financial revenue for the duration of the policy (because it is always clarified up front). Despite the long-term clarity of FiT in their policy design, it is clear that, in practice, they cannot always be counted upon by investors. For example, Spain had to unexpectedly reduce or cancel its FiT due to very high costs to the treasury. The tax credit policies for renewables in the US have been notoriously unstable due to the need for Congressional reauthorization. The renewable industry experienced many boom and bust cycles as a result. Tax credit policies in the Netherlands and Japan, however, are much more stable. Target lending, green bonds, and weather indexed insurance policy can be stable once the market is established. NDBs can be stable, but their priorities are subject to changing government preferences and objectives. National climate funds have both cases of success and failure, indicating a mixed record of stability.

Simplicity and transparency are also important design features of effective climate finance policies. Another success of the FiT in Germany was that it was framed in such an understandable and transparent way that investors could be easily mobilized at scale (Zhang, Citation2020). Due to the poor transparency of the US loan guarantee programme, however, many firms were unsure of their eligibility or were discouraged by the time-consuming process and high transaction costs involved. The high transaction costs were due to the need for project developers to find new financial partners and prepare new financial proposals. As a result, ‘It budgeted 6 billion dollars but it only distributed 2 billion’.Footnote3 One persistent criticism of the US loan guarantee programme was that the government was picking winners rather than establishing a market-based mechanism as some of the loans guarantee recipients were large firms rather than small ones.Footnote4 Lack of transparency also makes such programmes vulnerable to political interference or even pure corruption (Brown, Citation2012). Index-based insurance products are often difficult for consumers to understand so their uptake by buyers is weak (Linnerooth-bayer & Hochrainer-stigler, Citation2015). The effectiveness of targeted lending can be undermined when allocations are subject to political gaming and moral hazard problems (Calomiris & Himmelberg, Citation1994; Vittas & Wang, Citation1991). Lessons from earlier programmes include the need for targeted lending programmes to be bounded in scope, channelled through institutions that are sound, and subject to clear and transparent review criteria (Narayanan, Citation2016; Vittas & Cho, Citation1995).

Consistency and coordination among different climate finance policies, and coordination between financial and environmental policies, are also key to the achievement of policy goals. For instance, NDBs are highly sensitive to the enabling policy framework of their government. A combination of market-based and fiscal incentives used together with regulatory measures such as codes and standards could further strengthen the effectiveness of clean energy investments, especially when all are placed in the context of a longer-term strategic plan (Polzin et al., Citation2015).

The policy lesson is to anticipate that there may be reductions in technology costs (which means that a lower subsidy is needed) or that the production of low carbon energy may be higher than was anticipated (economies of scale effect). In either case, a well-designed policy could anticipate such events and schedule reviews based on triggers so that if the technology cost goes down, for example, the subsidy would likewise go down. These lessons indicate that financial sustainability and adaptability of policies are key features of effective climate finance policies.

Policy design features need to be considered in a broader national policy context, including investment and development (Corfee-Morlot et al., Citation2012). National macro-economic policy and financial system health can also shape the empirical performance of certain climate finance policies. For instance, the growth of a big green bond market requires both a mature bond market and supportive policies aimed at reducing the capital market bias for conventional power generation technologies (Meng et al., Citation2018; Ng & Tao, Citation2016; Wang & Zhang, Citation2017). Lack of environment and climate data, as well as lack of ratings, indices, and listings discourage green bond and weather indexed insurance. Furthermore, success or failure of one individual policy will depend on the effectiveness of other complementary policies. Therefore, policymakers need to tailor climate finance policies to address country-specific contexts.

4. Discussion and knowledge gaps

4.1. What works and what doesn't work in climate finance policy?

Success in climate finance policy not only includes the mobilization of additional finance, but also the achievement of climate goals (environmental integrity), minimization of public cost (economic efficiency), and careful incorporation of equity (fairness) considerations. In fact, establishing criteria to assess the success or failure of climate finance policy should be something that all governments routinely do when designing new or reforming existing climate finance policies.

It is clear that some climate finance policies are more effective than others depending on the criteria being used to evaluate them. FiT, tax credits, green bonds, loan guarantees, and NDBs are all effective at mobilizing private finance. National climate funds, targeted lending, disclosure, and green bonds could all theoretically be effective policy instruments, but evidence to date is either weak or thin due to specific policy design decisions or lack of available data to properly evaluate them. FiT and tax credits are often costlier to government budgets. Overall, less confidence exists about the environmental integrity of green bonds, information and disclosure policies, and targeted lending. Of course, the effectiveness of all of these policies is conditioned on good policy design. There is a general lack of transparency and data around the fairness of climate finance policies. For example, there are equity concerns about green bonds and loan guarantees as they tilt towards large corporations rather than small and medium firms. National experience with different climate finance policies has been mixed, in part because of policy design detail and in part because some of the policy instruments (e.g. weather indexed insurance, climate bonds) are relatively new and remain understudied.

Advantages and drawbacks exist for each policy type as elucidated in , so there is no perfect policy instrument. FiT and tax credits can work well to mobilize private climate finance due to their superior clarity, but they can be very costly to implement. Loan guarantees and NDBs have both proven very effective at mobilizing climate finance, but both are vulnerable to the political priorities of the prevailing government. Targeted lending and disclosure policies could prove to be successful climate policy tools in the future, but insufficient evidence currently exists about their efficacy. Green bonds appear to be growing very rapidly but their lack of standardization internationally hinders their environmental integrity.

Table 5. Strengths and weaknesses of climate finance policy instruments.

There is insufficient evidence to conclude whether certain climate policies work better in developing countries versus developed ones. Among the nine climate finance policies covered, only targeted lending and national climate funds are more prevalent in developing economies. These two types of climate finance policies, however, have a mixed record. Most of the climate finance policies (such as FiT, green bonds, and weather indexed insurance) originated in developed countries and then diffused to developing countries. In many cases, the adoption and design of climate finance policies in developing countries emulate the policies in developed ones, especially those that provided aid to them (Baldwin et al., Citation2019). Emulation, however, does not guarantee success. The effectiveness of climate finance policies often varies from country by country and also depends on the criteria used. It should be noted that climate finance policies tend to emphasize finance mobilization effectiveness over other metrics given capital scarcity, whereas environmental and social impacts are relatively neglected. China's experience with targeted lending and green bond policies is illustrative of the government's focus on finance mobilization.

4.2. Optimizing climate finance policies: balancing among goals

There is no policy ‘silver bullet’ because climate finance policies work best when they are nested in a coherent and aligned set of policies aimed at the achievement of climate-related goals. The impact of climate finance policies depends on the details of policy design, characteristics of the local market, country conditions (including macroeconomic conditions, institutional structures, and the maturity of the country's financial system), and the cost of and familiarity with the technologies that are being deployed in that country. As the economic competitiveness of new technologies increase, finance policy that is used to initially subsidize and buy down cost of new technology should then intentionally shift to a competition-based approach (Ball, Citation2012). For instance, a limited production tax credit (PTC)/investment tax credit (ITC) that is used in the early stage could evolve to a long term, progressive clean energy standard once incremental costs are initially addressed. Because all of the above conditions can change over time, climate finance policymaking should be a dynamic process and regular reviews of the efficacy of climate finance policies should be conducted and revisions made, as appropriate.

Climate finance policies are generally not used in isolation. They frequent accompany other climate policies due to the existence of multiple financial and non-financial barriers impeding the mobilization of private finance to address climate change (Chawla & Ghosh, Citation2019; Jaffe et al., Citation2005; Leete et al., Citation2013; Pillay et al., Citation2017; Polzin, Citation2017; Wilson et al., Citation2012). A wider set of policies can be superior to single policies if no conflicts exist among these policies to maximize finance mobilization (Howlett, Citation2014; Schmidt & Sewerin, Citation2019). Most countries examined in this study have indeed adopted both supply-side and demand-side policies to incentivize private investments. For instance, the US uses PTCs, ITCs, loan guarantees, accelerated depreciation, Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) in some states, and emissions trading in others to support renewable energy financing. These policies complement or sometimes partially overlap with each other, making it more complicated to distinguish the value added of each policy. From the point of view of economic efficiency, however, such policy density can be sub-optimal. How much policy redundancy exists among these co-existing policies? Is there any waste in that redundancy? The tension between financial mobilization effectiveness and economic efficiency necessitates a cautious balance between the two.

4.3. Knowledge gaps

The biggest gap is the lack of data availability from the private sector (Bayer & Urpelainen, Citation2016; Chawla & Ghosh, Citation2019). Public sector expenditures are easier to track because they are usually reported in the context of national budgeting processes, but even then, sometimes the public investments are not transparently reported. A consequence of the lack of data availability is the inability to ensure that there is no double counting.

A second knowledge gap that exists, in part due to data deficiencies, is whether there is a ‘crowding-out’ or a ‘crowding-in’ effect for specific climate finance policies. Most of the evidence reviewed in this paper suggests that public policies are somewhat successful in crowding in private investments by reducing commercial risk. Far less research (almost none) explores the failures of public policies in directing finance or crowding out private sector finance. Careful research is needed to examine whether inefficiencies might result from policies.

It is also essential to clarify in which areas concessional climate finance is still needed. With the rapid declines in the costs of wind and solar power, for example, the incremental costs of these technologies have nearly evaporated in many (but not all) countries. Yet, because these renewable energy technologies are intermittent, their complementary technologies (e.g. energy storage) are often required yet still out of reach. Where there is no need for subsidies and concessional finance, climate finance could be freed up for other purposes. How and when to remove public support for certain technologies or interventions is a key question deserving of more research.

Fourth, as governments often use multiple policies, how the interaction of policies shapes climate finance mobilization needs further consideration. Relatedly, literature on climate finance policy for adaptation and resilience measures is almost non-existent so there are few known examples of how private finance was mobilized through policies other than the emerging evidence on weather indexed insurance.

Fifth, the role of political systems in shaping policy adoption is an area ripe for further study. While this paper focuses on analyzing the effectiveness of policies that already adopted, there is scope for further work in understanding how the differences in political systems shape the adoption and design of climate finance policies. For example, liberal market, coordinated and state-led economies may display varying levels of appetite for similar policies.

Sixth, it is important to systematically examine whether and how the effectiveness of climate policies differs across developing and developed economies. Key limitations in this article were the short historical records of climate finance policies in many countries as well as the difficulty of accessing data in certain developing countries.

Finally, will climate change itself undermine the effectiveness of climate finance policies? Are investments in infrastructure resilient to future climate change? A new commercial development in a low-lying coastal area, for example, will be vulnerable to sea-level rise. Even if that commercial development was built to very high standards in terms of energy efficiency and green building principles using climate finance, if the whole development is vulnerable to climate change itself, it may turn out to be a poor investment.

Specific knowledge gaps related to individual climate finance policies are provided in Appendix F.

5. Conclusions and policy implications

This paper examines the empirical performance of nine types of climate finance policies through a literature review and case studies. Multi-dimensional criteria, including mobilization effectiveness, economic efficiency, environment integrity, and equity, are established to evaluate these nine climate finance policies. It is clear that some climate finance policies are more effective than others depending on the criteria being used to evaluate them and their design details. Strengths and weaknesses exist for all of these policy instruments.

A few specific policy implications emerge from the findings of this paper. The lack of government policy can inhibit effective mobilization of climate finance. The lack of commonly agreed, enforceable international standards for green bonds, for example, has called into question whether or not these bonds are truly green. When policies do exist, they need to be enforced to be effective. To make government funds go further, governments should be wary of those policies that have proved to be economically costly. Government attention should be paid to the environment integrity and fairness impacts of climate finance policies. Technological change is inherently dynamic and often disruptive to markets. Climate finance policies must thus anticipate change and be able to respond to it. Climate finance policies should be nested in a comprehensive set of regulatory, fiscal, industrial, market-based, and other climate change policies that disincentivize investment in polluting technologies and incentivize investment in low or zero-carbon technologies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (94.8 KB)Acknowledgements

All three authors equally contributed to this article and are listed alphabetically. The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the following funders of the Climate Policy Lab: BP International, Ltd., the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and ClimateWorks Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview conducted in India, Nov. 19th, 2018.

2 In May 2020, the Chinese government released a draft version of amendments to the green bond policy for consultations. The proposed changes would unify the existing green bond standards and would lead to an exclusion of clean coal from the list of eligible projects.

3 Interview conducted in the US, Mar. 28th, 2018.

4 Interview conducted in the US, Mar. 29th, 2018.

References

- Agarwal, S., & Singh, T. (2017). Unlocking the green bond potential in India. TERI. https://www.teriin.org/projects/nfa/files/Green-Bond-Working-Paper.pdf

- Bai, Y. (2011). Financing a green future: An examination of China’s banking sector for green finance. IIIEE Master Thesis. http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/2203222

- Baldwin, E., Carley, S., & Nicholson-Crotty, S. (2019). Why do countries emulate each others’ policies? A global study of renewable energy policy diffusion. World Development, 120(C), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.012

- Ball, J. (2012). Tough love for renewable energy: Making wind and solar power affordable. Foreign Affairs, 91(3), 122–133.

- Bayer, P., & Urpelainen, J. (2016). It is all about political incentives: Democracy and the renewable feed-in tariff. The Journal of Politics, 78(April), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1086/684791

- Bhandary, R. R. (2020). The political economy of national climate funds. Tufts University.

- Bimha, A., & Nhamo, G. (2017). Sustainable development, share price and carbon disclosure interactions: Evidence from South Africa’s JSE 100 companies. Sustainable Development, 25(5), 400–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1670

- Bowen, A. (2011). Raising climate finance to support developing country action: Some economic considerations. Climate Policy, 11(3), 1020–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2011.582388

- Bowen, A., Campiglio, E., & Herreras Martinez, S. (2017). An ‘equal effort’ approach to assessing the north–south climate finance gap. Climate Policy, 17(2), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1094728

- Brahmbhatt, M. & Steer, A. (2016). Mobilizing climate finance (Eds.), International climate finance. Routledge. 153–168.

- Brown, P. (2012). Loan guarantees for clean energy technologies: Goals, concerns, and policy options. R42152. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42152.pdf

- Buchner, B., Clark, A., Falconer, A., Macquarie, R., Meattle, C., Tolentino, R., & Cooper, W. (2019). Global landscape of climate finance 2019. Climate Policy Initiative. https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-Global-Landscape-of-Climate-Finance.pdf

- Butler, L., & Neuhoff, K. (2008). Comparison of feed-in tariff, quota and auction mechanisms to support wind power development. Renewable Energy, 33(8), 1854–1867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2007.10.008

- Calomiris, C. W., & Himmelberg, C. P. (1994). Directed credit programs for agriculture and industry: Arguments from theory and fact. Working Paper 14336. World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/968051468739802512/pdf/multi-page.pdf

- Chawla, K., & Ghosh, A. (2019). Greening new pastures for green investments. Issue Brief. Council on Energy, Environment and Water. https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/CEEW-Greener-Pastures-for-Green-Investments-20Sep19.pdf

- Chiang, J. (2017). Growing the U.S. green bond market: Volume 1: The barriers and challenges. https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/greenbonds/publications/reports/green_bond_market_01.pdf

- Clement, D., Lehman, M., Hamrin, J., & Wiser, R. (2005). International tax incentives for renewable energy: Lessons for public policy. Center for Resource Solutions. https://resource-solutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/IntPolicy-Renewable_Tax_Incentives.pdf

- Climate Bonds Initiative. (2018). China green bond market 2018. Climate Bonds Initiative. https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/china-sotm_cbi_ccdc_final_en260219.pdf

- Clò, S., Cataldi, A., & Zoppoli, P. (2015). The merit-order effect in the Italian power market: The impact of solar and wind generation on national wholesale electricity prices. Energy Policy, 77(February), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.11.038

- Corfee-Morlot, J., Marchal, V., Kauffmann, C., Kennedy, C., Stewart, F., Kaminker, C., & Ang, G. (2012). Towards a green investment policy framework: The case of low-carbon, climate-resilient infrastructure. OECD Environment Working Papers 48. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k8zth7s6s6d-en

- Couture, T., & Gagnon, Y. (2010). An analysis of feed-in tariff remuneration models: Implications for renewable energy investment. Energy Policy, 38(2), 955–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.10.047

- Department of Energy. (2019a). A year of continued impact: Annual portfolio status report. FY2018. Loan program office. Loan Programs Office, Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/09/f67/DOE-LPO_FY2018_APSR_FINAL.pdf

- Department of Energy. (2019b). Investing in American Energy. Loan Programs Office, Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2015/09/f26/loans-program-office.pdf.

- Drechsler, M., Meyerhoff, J., & Ohl, C. (2012). The effect of feed-in tariffs on the production cost and the landscape externalities of wind power generation in West Saxony, Germany. Energy Policy, 48(September), 730–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.06.008

- Flåm, K. H., & Skjaerseth, J. B. (2009). Does adequate financing exist for adaptation in developing countries? Climate Policy, 9(1), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.3763/cpol.2008.0568

- Frondel, M., Ritter, N., & Schmidt, C. M. (2008). Germany’s solar cell promotion: Dark clouds on the horizon. Energy Policy, 36(11), 4198–4204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.07.026

- Frondel, M., Ritter, N., Schmidt, C. M., & Vance, C. (2010). Economic impacts from the promotion of renewable energy technologies: The German experience. Energy Policy, 38(8), 4048–4056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.03.029

- Gallagher, K. S., & Xuan, X. (2018). Titans of the climate: Explaining policy process in the United States and China. American and Comparative Environmental Policy. The MIT Press.

- Geddes, A., Schmidt, T. S., & Steffen, B. (2018). The multiple roles of state investment banks in low-carbon energy finance: An analysis of Australia, the UK and Germany. Energy Policy, 115(April), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.01.009

- Gelabert, L., Labandeira, X., & Linares, P. (2011). An ex-post analysis of the effect of renewables and cogeneration on Spanish electricity prices. Energy Economics, 33(December), S59–S65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2011.07.027

- Global Commission on Adaptation. (2019). Adapt now: A global call for leadership on climate resilience. Global Center on Adaptation and World Resources Institute. https://cdn.gca.org/assets/2019-09/GlobalCommission_Report_FINAL.pdf

- Grösche, P., & Schröder, C. (2014). On the redistributive effects of Germany’s feed-in tariff. Empirical Economics, 46(4), 1339–1383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0728-z

- Grubb, M. (2011). International climate finance from border carbon cost levelling. Climate Policy, 11(3), 1050–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2011.582285

- Haites, E. (2011). Climate change finance. Climate Policy, 11(3), 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2011.582292

- Ho, H. V. E. (2018). Sustainable finance & China’s green credit reforms: A test case for bank monitoring of environmental risk. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3124304. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3124304

- Howlett, M. (2014). From the ‘old’ to the ‘new’ policy design: Design thinking beyond markets and collaborative governance. Policy Sciences, 47(3), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-014-9199-0

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Edited by V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_Citation.pdf

- Jaffe, A., Newell, R., & Stavins, R. (2005). A tale of two market failures: Technology and environmental policy. Ecological Economics, 54(2–3), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.12.027

- Kumar, P., & Firoz, M. (2018). Impact of carbon emissions on cost of debt-evidence from India. Managerial Finance, 44(12), 1401–1417. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-03-2018-0108

- Lee, S.-Y., Park, Y.-S., & Klassen, R. D. (2015). Market responses to firms’ voluntary climate change information disclosure and carbon communication. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1321

- Leete, S., Xu, J., & Wheeler, D. (2013). Investment barriers and incentives for marine renewable energy in the UK: An analysis of investor preferences. Energy Policy, 60(C), 866–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.011

- Lerner, J., & Schoar, A. (Eds.). (2010). International differences in entrepreneurship. National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report. University of Chicago Press.

- Li, L., Liu, Q., Tang, D., & Xiong, J. (2017). Media reporting, carbon information disclosure, and the cost of equity financing: Evidence from China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24(10), 9447–9459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-8614-4

- Linnerooth-bayer, J., & Hochrainer-stigler, S. (2015). Financial instruments for disaster risk management and climate change adaptation. Climatic Change, 133(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-1035-6

- Maaloul, A. (2018). The effect of greenhouse gas emissions on cost of debt: Evidence from Canadian firms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(6), 1407–1415. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1662

- Maclean, J., Tan, J., Tirpak, D., & Sonntag-O’Brien, V. (2008). Public finance mechanisms to mobilize investment in climate change mitigation. UNEP DTIE. http://www.climate-finance.org/sites/default/files/media/uneppublicfinancereport.pdf

- Matisoff, D. C., & Johnson, E. P. (2017). The comparative effectiveness of residential solar incentives. Energy Policy, 108(September), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.032

- Matsuo, T., & Schmidt, T. S. (2017). Hybridizing low-carbon technology deployment policy and fossil fuel subsidy reform: A climate finance perspective. Environmental Research Letters, 12(1), 014002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa5384

- Mazzucato, M., & Penna, C. C. R. (2016). Beyond market failures: The market creating and shaping roles of state investment banks. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 19(4), 305–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2016.1216416

- McKinsey & Company. (2009). Pathways to a low-carbon economy version 2 of the global greenhouse gas abatement cost curve. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/sustainability/cost%20curve%20pdfs/pathways_lowcarbon_economy_version2.ashx

- Menanteau, P., Finon, D., & Lamy, M.-L. (2003). Prices versus quantities: Choosing policies for promoting the development of renewable energy. Energy Policy, 31(8), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(02)00133-7

- Meng, A. X., Lau, I., & Boulle, B. (2018). China green bond market 2017. Cliamte Bonds Initiative and China Central Depository and Clearing Company. https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/china_annual_report_2017_en_final_14_02_2018.pdf

- Narayanan, S. (2016). The productivity of agricultural credit in India. Agricultural Economics, 47(4), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12239

- Nelson, T., Simshauser, P., & Kelley, S. (2011). Australian residential solar feed-in tariffs: Industry stimulus or regressive form of taxation? Economic Analysis and Policy, 41(2), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0313-5926(11)50015-3

- Neuhoff, K., Stelmakh, K., Amecke, H., Novikova, A., Deason, J., & Hobbs, A. (2012). Financial incentives for energy efficiency retrofits in buildings. ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings. https://www.aceee.org/files/proceedings/2012/data/papers/0193-000422.pdf

- Ng, T. H., & Tao, J. Y. (2016). Bond financing for renewable energy in Asia. Energy Policy, 95(August), 509–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.015

- Olbrisch, S., Haites, E., Savage, M., Dadhich, P., & Shrivastava, M. K. (2011). Estimates of incremental investment for and cost of mitigation measures in developing countries. Climate Policy, 11(3), 970–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2011.582281

- Partridge, C., & Medda, F. (2018). The creation and benchmarking of a green municipal bond index. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3248423. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3248423

- Persson, Å., Klein, R. J. T., Siebert, C. K., & Atteridge, A. (2009). Adaptation finance under a Copenhagen agreed outcome. Stockholm Environment Institute.

- Picard, P. (2008). Natural disaster insurance and the equity-efficiency trade-off. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 75(1), 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2007.00246.x

- Pillay, K., Aakre, S., & Torvanger, A. (2017, March). Mobilizing adaptation finance in developing countries. 42. https://pub.cicero.oslo.no/cicero-xmlui/handle/11250/2435614

- Pirnia, M., Nathwani, J., & Fuller, D. (2011). Ontario feed-in-tariffs: System planning implications and impacts on social welfare. The Electricity Journal, 24(October), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2011.09.009

- Polzin, F. (2017). Mobilizing private finance for low-carbon innovation – A systematic review of barriers and solutions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 77(September), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.04.007

- Polzin, F., Migendt, M., Täube, F. A., & von Flotow, P. (2015). Public policy influence on renewable energy investments—A panel data study across OECD countries. Energy Policy, 80(May), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.01.026

- Roberts, J. T., Stadelmann, M., & Huq, S. (2010). Copenhagen’s climate finance promise: Six key questions. International Institute for Environment and Development. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/7272.pdf

- Roberts, J. T., & Weikmans, R. (2017). Postface: Fragmentation, failing trust and enduring tensions over what counts as climate finance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9347-4

- Romani, M., & Stern, N. (2016). Sources of finance for climate action: Principles and options for implementation mechanisms in this decade. In E. F. Haites (Ed.), International climate finance. Routledge. 135-152.

- Schmidt, T. S., & Sewerin, S. (2019). Measuring the temporal dynamics of policy mixes – An empirical analysis of renewable energy policy mixes’ balance and design features in nine countries. Research Policy, 48(10), 103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.012

- Sherlock, M. (2018). The renewable electricity production tax credit: In brief. CRS Report R43453. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43453.pdf

- Shi, X., Liu, X., & Yao, L. (2016). Assessment of instruments in facilitating investment in off-grid renewable energy projects. Energy Policy, 95(August), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.02.001

- Shishlov, I., Morel, R., & Cochran, I. (2016). Beyond transparency: Unlocking the full potential of green bonds. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.11081.85606

- Stewart, R. B., Kingsbury, B., & Rudyk, B. (Eds.). (2009). Climate finance: Regulatory and funding strategies for climate change and global development. New York University Press; New York University Abu Dhabi Institute.

- UNCTAD (Ed.). (2014). Investing in the SDGs: An action plan. World Investment Report 2014. United Nations.

- van Rooijen, S. N. M., & van Wees, M. T. (2006). Green electricity policies in the Netherlands: An analysis of policy decisions. Energy Policy, 34(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2004.06.002

- Vittas, D., & Cho, Y. J. (1995). Credit policies: Lessons from East Asia. WPS 1458. World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/395781468752730652/pdf/multi-page.pdf

- Vittas, D., & Wang, B. (1991). Credit policies in Japan and Korea: A review of the literature. 747. Policy Research Working Paper Series. The World Bank. https://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/wbrwps/747.html

- Vogel, R. C., & Adams, D. W. (1997). The benefits and costs of loan guarantee programs. The Financier, 4(1-2), 22–29. https://www.microfinancegateway.org/sites/default/files/mfg-en-paper-the-benefits-and-costs-of-loan-guarantee-programs-1996.pdf

- Wang, Y., & Zhang, R. (2017). China’s green bond market. 44. Internaitonal Capital Market Features. ICMA Group.

- Wilson, C., Grubler, A., Gallagher, K. S., & Nemet, G. F. (2012). Marginalization of end-use technologies in energy innovation for climate protection. Nature Climate Change, 2(11), 780–788. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1576

- Wood, D., & Grace, K. (2011). A brief note on the global green bond market. Initiative for Responsible Investment and the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations. http://iri.hks.harvard.edu/files/iri/files/iri_note_on_the_global_green_bonds_market.pdf

- Yamamoto, Y. (2017). Feed-in tariffs combined with capital subsidies for promoting the adoption of residential photovoltaic systems. Energy Policy, 111(December), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.09.041

- Zerbib, O. D. (2016). Is there a green bond premium? The yield differential between green and conventional bonds. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2889690. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2889690

- Zhang, F. (2020). Leaders and followers in finance mobilization for renewable energy in Germany and China. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 37(December), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.08.005

- Zhang, B., Yang, Y., & Bi, J. (2011). Tracking the implementation of green credit policy in China: Top-down perspective and bottom-up reform. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(4), 1321–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.12.019

- Zhou, Z., Zhang, T., Wen, K., Zeng, H., & Chen, X. (2018). Carbon risk, cost of debt financing and the moderation effect of media attention: Evidence from Chinese companies operating in high-carbon industries. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1131–1144. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2056

- Zhu, J., Fan, Y., Deng, X., & Xue, L. (2019). Low-carbon innovation induced by emissions trading in China. Nature Communications, 10(1), 4088. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12213-6