ABSTRACT

Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, international financial assistance is expected to support African and other developing countries as they prepare for and adapt to the impacts of climate change. The impact of this finance depends on how much finance is mobilized and where it is targeted. However, there has been no comprehensive quantitative mapping of adaptation-related finance flows to African countries to date. Here we track development finance principally targeting adaptation from bilateral and multilateral funders to Africa between 2014 and 2018. We find that the amounts of finance are well below the scale of investment needed for adaptation in Africa, which is a region with high vulnerability to climate change and low adaptation capacity. Finance targeting mitigation (US$30.6 billion) was almost double that for adaptation (US$16.5 billion). The relative share of each varies greatly among African countries. More adaptation-related finance was provided as loans (57%) than grants (42%) and half the adaptation finance has targeted just two sectors: agriculture; and water supply and sanitation. Disbursement ratios for adaptation in this period are 46%, much lower than for total development finance in Africa (at 96%). These are all problematic patterns for Africa, highlighting that more adaptation finance and targeted efforts are needed to ensure that financial commitments translate into meaningful change on the ground for African communities.

Key policy insights

Between 2014 and 2018, adaptation-related finance committed by bilateral and multilateral funders to African countries remained well below US$5.5 billion per year, or roughly US$5 per person per year; these amounts are well below the estimates of adaptation costs in Africa.

Funders have not strategically targeted support for adaptation activities towards the most vulnerable to climate change African countries.

Lessons from countries that have been more successful in accessing finance point to the value of more sophisticated domestic adaptation policies and plans; of alignment with priorities of the NDC; of meeting funding requirements of specific funders; and of the strategic use of climate funds by national planners.

A low adaptation finance disbursement ratio in this period in Africa (at 46%) relates to barriers impeding the full implementation of adaptation projects: low grant to loan ratio; requirements for co-financing; rigid rules of climate funds; and inadequate programming capacity within many countries.

Introduction

Developed-country Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) have committed to mobilizing US$100 billion annually by 2020 to support climate action in developing countries (UNFCCC, Citation2010, Citation2009). Some estimates of finance with climate objectives committed to developing countries globally suggest it increased from US$58.6 billion in 2016 to reach US$71.2 billion in 2017, but that this growth slowed to total US$78.9 billion in 2018 (OECD, Citation2020). These funding flows, especially as they relate to adaptation, are recognized as a key dimension of climate justice (Khan et al., Citation2020). This is because many developing countries, including African countries, have contributed among the least to historical greenhouse gas emissions responsible for anthropogenic climate change yet face many of the most severe risks (Niang et al., Citation2014; Ritchie & Roser, Citation2017; Shukla et al., Citation2019).

African nations – 33 of which are classified as Least Developed Countries (LDCs)(UNCTAD, Citationn.d.) – have been recognized as ‘particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change’ in the UNFCCC context since 2007 (UNFCCC, Citation2007). Globally, many African countries are among the most sensitive to the impacts of climate change on food security, health, economies and ecosystems (Burke et al., Citation2018; Costello et al., Citation2009; Niang et al., Citation2014). For example, yield loss projections for staple crops are larger for tropical regions of Africa and poorer populations in sub-Saharan Africa are at highest risk of malnutrition (Challinor et al., Citation2014; Field et al., Citation2014; Knox et al., Citation2012; Rosenzweig et al., Citation2014; Thornton et al., Citation2011). Without inclusive development and targeted adaptation measures, climate change is projected to push tens of millions more Africans into extreme poverty by 2030 (Hallegatte et al., Citation2016). Compounding this vulnerability is that many African countries have limited financial capacity to instigate adaptation (United Nations, Citation1992). While African countries (including farmers, businesses and households) are already investing in adaptation, the magnitude of the projected climate impacts far outweighs existing capacity to adapt (Schaeffer et al., Citation2015). Failure to adapt will, in turn, propel a negative feedback cycle that undermines development and magnifies climate risks (Niang et al., Citation2014). The World Bank estimates that, globally, sub-Saharan Africa will bear the highest adaptation costs per unit of gross domestic product (0.6-0.7% of GDP), owing to lower GDPs but also to higher costs of adaptation for water resources, due to changes in precipitation patterns (World Bank, Citation2010). This inequity in the vulnerability of African countries to climate impacts, despite their relatively low contribution to the root causes of climate change, highlights a systemic injustice that finance for climate change adaptation aims to address.

Indeed, ‘The provision of scaled-up financial resources should aim to achieve a balance between adaptation and mitigation’, as stated in Article 9.4 of the Paris Agreement, and priority is to be given to particularly vulnerable countries (UNFCCC, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation1992). The share of climate finance going to adaptation activities globally was estimated at 21% in 2018, compared to 70% for mitigation (OECD, Citation2020). However, understanding of adaptation finance flows is constrained by data availability and consistency, with multiple methodological barriers in making such an analysis challenging.

Firstly, reporting relies largely on self-reporting by donors with uncertainty or disagreement over definitions of adaptation. All Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are required to report data on international public financial support (also known as development assistance) to developing countries. Some non-OECD countries also report to the OECD on a voluntary basis, as do some multilateral institutions and climate funds. However, while the need to support developing countries in adapting to climate change is recognized and agreed under the UNFCCC (UNFCCC, Citation2009), there is a certain ambiguity surrounding the scientific and institutional definitions of adaptation (Hall, Citation2017; Hall & Persson, Citation2018; MDBs, Citation2019; Roggero et al., Citation2018). For example, there are still contrasting views on whether adaptation is a local and private good or a global public good, with various developing countries, including vulnerable African states, endorsing the view of adaptation as the latter and asking for strong binding commitments on adaptation (Hall & Persson, Citation2018). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines adaptation as ‘the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects’ and distinguishes between human systems in which ‘adaptation seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities’, and natural systems in which ‘human intervention may facilitate adjustment to expected climate and its effects’ (Field et al., Citation2014). According to the OECD Rio Marker for adaptation, which is used to guide funders reporting financial assistance targeting climate change, an activity should be classified as adaptation-related if ‘it intends to reduce the vulnerability of human or natural systems to the current and expected impacts of climate change, including climate variability, by maintaining or increasing resilience, through increased ability to adapt to, or absorb, climate change stresses, shocks and variability and/or by helping reduce exposure to them. This encompasses a range of activities from information and knowledge generation, to capacity development, planning and the implementation of climate change adaptation actions’ (OECD, Citation2011).

Second, equity issues in climate finance relating to amounts of finance provided relative to estimates of need, delayed disbursement of funding, the balance of funding between mitigation and adaptation, and the distribution of funding between sectors remain largely unquantified at sector and regional levels. In numerous submissions under the UNFCCC, including nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, African governments identify billions of dollars in climate finance needs, with adaptation costs of at least US$7.4 billion per year by 2020 for the subset of adaptation needs listed in the NDCs (AfDB, Citation2019; Zhang & Pan, Citation2016). Furthermore, adaptation costs in Africa are expected to rise rapidly as global warming increases, reaching tens of billions of dollars per year by 2050 (Schaeffer et al., Citation2015, Citation2013). However, until now there has been no comprehensive quantitative mapping of adaptation-related finance flows to individual African countries and sectors. Global reports typically provide only highly aggregated figures for Africa or Sub-Saharan Africa (Buchner et al., Citation2019; MDBs, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2020, Citation2018). A key publication that provides climate finance trends is made available by the OECD every year (OECD, Citation2020). While the OECD report provides aggregated global trends, it does not provide a breakdown for Africa by region, country, sector or per capita for finance targeting adaptation, mitigation or both simultaneously. It also does not identify the main providers of adaptation finance, nor the disbursement ratio, which is an important indicator of whether commitments are translating into on-ground activities. Studies that do provide more details for Africa, pre-date the Paris Agreement (Nakhooda et al., Citation2011; Thornton, Citation2011), provide only partial coverage (that is, look only at specific donors (Watson & Schalatek, Citation2019) or specific recipients (Nakhooda et al., Citation2011)), or focus only on specific questions, such as factors influencing the allocation of adaptation-related finance between countries (Weiler & Sanubi, Citation2019) or stakeholders’ experiences accessing and using climate-related finance (Thornton, Citation2011).

Here we fill this important knowledge gap through a novel analysis of international finance commitments and disbursements to African countries from 2014 to 2018, which principally targeted adaptation. We integrate data from two databases managed by the OECD, tracking support from bilateral and multilateral funders, including multilateral development banks (MDBs), to individual African countries or as regional support. Most of this funding is channelled through development finance institutions and is reported as development finance to the OECD. We note that the issue of ‘new and additional’ resources, which is politically important to African countries, has never been clarified in the UNFCCC context (African Group, Citation2018; Khan et al., Citation2020; Weikmans et al., Citation2017; Weikmans & Roberts, Citation2019; Weiler et al., Citation2018). A central concern of developing countries in this discussion is whether finance to tackle climate change represents new resources or is simply re-labelled and diverted from traditional development finance. The latter could compromise their ability to tackle other critical development challenges. Given the obstacles stemming from the lack of an agreed definition, in our analysis, we present the total funding reported by funders to the OECD as supporting adaptation (which we refer to as ‘adaptation-related finance’), but we do not (and are unable to) assess whether these amounts are additional to what would otherwise have been development finance committed to other objectives.

We show how finance commitments changed over the 2014–2018 period, and we compare the amounts provided for adaptation relative to mitigation. We analyse the distribution of finance among different countries (in total and per capita terms), the financial instruments used, the role of different funders, the sectors targeted, and how commitments compare with actual disbursements of finance. The results are useful not only to decision-makers in the African context, but also in UNFCCC negotiations on climate finance, in the global stocktake of implementation of the Paris Agreement, and in discussions of how to scale-up climate-related finance in 2025 and beyond.

Methods

Scope

This study focuses on quantifying the support provided as international public finance that targets climate adaptation in African countries as reported to OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) (for a description of data sources see Supplementary Annex A). We cover the period 2014–2018 inclusive, which is the last five years for which data are publicly available as of October 2020. By international public finance we mean funding provided either bilaterally from OECD countries and some non-OECD countries (where data are available) or multilaterally by MDBs, climate funds or other international institutions (for a full list of recipients and funders see Supplementary Annex B).

Methodologies for reporting climate-related finance

Across the spectrum of bilateral and multilateral funders, two main methodologies are presently used for tracking and reporting climate-related finance: the Rio Marker and the Climate Components methodologies, established by the OECD and the multilateral development banks (MDBs), respectively. Although accounting methods differ

(Multilateral Development Bank group, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2018), both use definitions of climate change mitigation and adaptation that are compatible (OECD, Citation2018). However, the definition of adaptation (provided in the introduction) used by both methodologies is quite broad, and both methods rely on reporting by funders.

All the funders in our analysis, except the MDBs, use the Rio Marker approach (OECD, Citation2011). In this approach, for each transaction, funders indicate whether adaptation and/or mitigation was targeted as a ‘principal’ or ‘significant’ objective or was ‘not targeted’. ‘Principal’ indicates that the objective (mitigation or adaptation) is explicitly stated as fundamental in the design of, or the motivation for, the activity. ‘Significant’ is used to indicate that the objective is explicitly stated but is not the fundamental driver or motivation for undertaking the activity. ‘Not targeted’ means that the activity was screened when reporting to the OECD but found not to target the objective in any significant way. The two climate change markers are not mutually exclusive, therefore both adaptation and mitigation can be denoted by funders as targeted by the same financial transaction. Our analysis concentrates on financial support that was reported as principally targeting climate change adaptation and/or mitigation (see Supplementary Annex A). The main reason for excluding activities that were tagged as significantly targeting adaptation or mitigation is that the data quality in this category is much less reliable and its inclusion therefore has a substantial distorting effect (Michaelowa & Michaelowa, Citation2011; Weikmans et al., Citation2017). There seems to be a tendency to overstate the relevance of adaptation in development projects and this over-reporting is more prevalent under the significant category (Donner et al., Citation2016; Henders et al., Citation2019; Michaelowa & Michaelowa, Citation2011; Weiler et al., Citation2018), which increases the risk of overestimating finance amounts. To avoid this risk, several recent studies chose to exclude financial transactions tagged as significantly targeting adaptation-related finance (Henders et al., Citation2019; McKee et al., Citation2020; Weiler et al., Citation2018; Weiler & Sanubi, Citation2019). The only exception to this is for data related to the Green Climate Fund (GCF). When reporting to the OECD, the GCF has tagged all funding commitments as ‘significantly’ rather than ‘principally’ targeting climate change, but the Fund’s raison d’etre is specifically to tackle climate change. Following a conversation about this with staff from the GCF Secretariat (pers. comm, October 2020), we confirmed that this is a coding error when reporting. To fix for this error, our analysis re-codes all GCF commitments to Africa as principally targeting adaptation.

The MDBs report data on their support for climate change based on their own Climate Components methodology (MDBs, Citation2019). Using this approach, the MDBs identify the specific components of a project or transaction that directly contribute to or promote mitigation or adaptation, or both simultaneously. By contrast, when other funders report using the Rio Marker approach, the amount reported as climate-related is the full value of each project transaction rather than only the portion of the transaction that specifically targets climate change (OECD, Citation2011). This is a noteworthy difference between the Climate Components methodology used by MDBs and the Rio Marker approach used by other funders, which makes direct comparison between different kinds of funders difficult. However, from the recipient perspective – in our analysis, Africa – combining the data obtained from both reporting approaches still provides the most comprehensive picture of how and where financial support for adaptation is targeted.

In our analysis we take the figures reported using the two different methodologies at face-value, since it is not possible to make unifying adjustments.

Data limitations

The OECD DAC data on development finance provide, to the best of our knowledge, the most comprehensive and comparable data on international development finance for climate change (Doshi & Garschagen, Citation2020; Weiler et al., Citation2018; Weiler & Sanubi, Citation2019). However, there are some important limitations to acknowledge in relation to our primary data sources. First, the attribution of financial support to climate adaptation objectives is subjective. This judgement is made by the bilateral and multilateral funders and is not independently verified. For example, a number of studies argue that the self-reporting of donors and the lack of independent quality control results in low data reliability and sometimes significant overestimations of finance flows identified with the use of Rio Markers (AdaptationWatch, Citation2015; Junghans & Harmeling, Citation2012; Michaelowa & Michaelowa, Citation2011; Weikmans et al., Citation2017). Second, the rigour and level of disaggregation used by funders when reporting data to the OECD DAC or the MDBs varies, and can introduce errors. Third, loan amounts presented in our analysis under both the Rio Marker and the Climate Components methodologies are at face-value instead of the grant-equivalentFootnote1 amounts because these data do not exist for the period of our analysis. Fourth, not all development finance transactions are screened against the Rio Marker for adaptation, which means there may be adaptation-related finance flows that are not captured in our datasets. In our analysis, 34% of the total number of project transactions (144286 transactions out of total 424457) were not screened for adaptation. Fifth, the consistency with which funders use the Rio Markers when reporting disbursements might influence the observed disbursement ratios.

Results and discussion

Financial commitments for adaptation

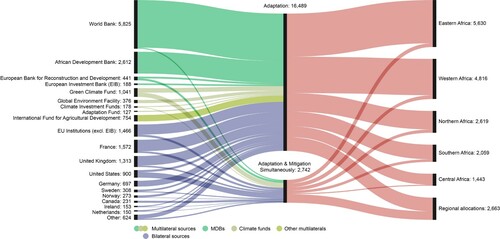

Climate-related finance commitments from bilateral and multilateral funders to African countries, including regional allocations, which are not country-specific, amounted to US$49.9 billion from 2014 to 2018. Of this total, US$19.2 billion was earmarked for adaptation activities, including US$2.7 billion for initiatives that combined adaptation and mitigation () – equivalent to 31% of the global public development finance to climate adaptation.

Figure 1. Total adaptation-related finance (commitments) to African countries and regions, by source and recipient regions, 2014–2018 (US$ millions, constant prices). Source: OECD DAC 2020.

Notes: Regional allocations include financial commitments that were reported separately from allocations to individual countries. For commitments reported under the Rio Marker methodology, the ‘Principal’ marker for adaptation is used.

Based on our analysis, about 42% of the adaptation-related finance was provided as grants (38% as ODA grants and 4% as MDB grants) and 57% as debt instruments (14% as ODA loans and 43% via MDB debt instruments). The remaining 1% includes minor amounts of mezzanine finance instruments and equity and shares in collective investment vehicles.

Bilateral and multilateral sources contributed 39% and 61%, respectively, of the total adaptation-related commitments. The multilateral component comprises 47% from the MDBs, 9% from multilateral climate funds and 5% from other international organizations (). The highest commitments from multilateral climate funds were provided by the GCF, which committed roughly US$1 billion.

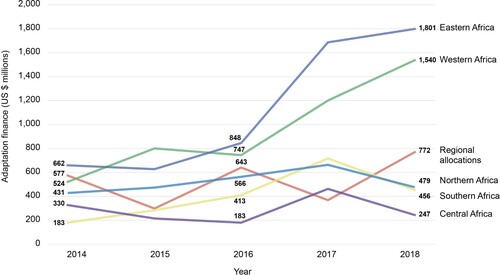

Total adaptation related finance remained below US$3.5 billion between 2014 and 2016 (US$2.7, 2.7 and 3.4 billion for 2014, 2015 and 2016, respectively), while it increased in 2017 (US$5.1 billion) and 2018 (US$5.3 billion). Substantially more finance was committed to projects in Eastern Africa and Western Africa than to those in other sub-regions, and both have seen an increase in funding from 2016 onwards (). Aggregated commitments in each of northern, central and southern Africa, meanwhile, were below US$0.8 billion per year throughout the period analysed, and all experienced a decline in 2018 relative to 2017 ().

Figure 2. Trend of adaptation-related finance commitments to African regions over time (US$ millions, constant prices). Source: OECD DAC 2020.

Notes: For commitments reported under the Rio Marker methodology, the ‘Principal’ marker for adaptation is used.

Overall, total financial commitments for adaptation over the studied period are far below the various estimates of adaptation costs in Africa, which range between US$7-15 billion per year for 2020 (AfDB, Citation2019; Schaeffer et al., Citation2013). Based on a meta-analysis of adaptation cost estimates and assuming future socio-economic trends do not shift markedly from historical trends, adaptation costs for Africa by 2050 range from US$11.5-36 billion per year for global warming around 1.5°C and US$18-59 billion per year for global warming around 2°C (Chapagain et al., Citation2020). Other estimates reach US$50-100 billion in scenarios for 2050 (Schaeffer et al., Citation2013) and 2100 (Schaeffer et al., Citation2015), respectively. Furthermore, analysis suggests these cost projections are likely to be substantial underestimates (UNEP, Citation2016).

More funding for mitigation than for adaptation

Not only is climate-related finance meant to be balanced between adaptation and mitigation (Burke et al., Citation2018; Niang et al., Citation2014), but many developing countries – particularly LDCs – express a stronger demand for finance supporting adaptation rather than mitigation (Mensah, Citation2020; Zhang & Pan, Citation2016).

However, the data show that, overall, allocations of climate-related finance do not meet the stronger demand for adaptation expressed by many African countries. Substantially more climate-related finance commitments to Africa targeted mitigation (US$30.6 billion, or 61%) compared to adaptation (US$16.5 billion, or 33%); as noted above, an additional US$2.7 billion (6%) supported both mitigation and adaptation. While all regions received more finance for mitigation than for adaptation, the imbalance was greatest in Northern Africa, where 83% of the finance was for mitigation. Allocations tagged as regional support were 62% for mitigation and southern Africa received 60% for mitigation whereas the allocation was closer to parity between mitigation and adaptation for western (54%,), central (52%) and eastern Africa (52%).

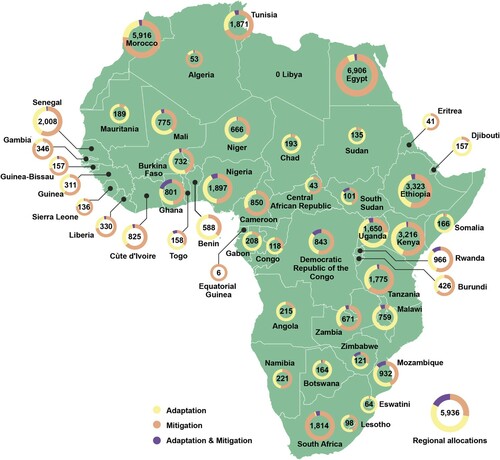

At the country level, this balance varies more widely (). Ten African countries received more than 75% of their climate-related finance for adaptation (Angola, Botswana, Chad, Djibouti, Eswatini, Gabon, Malawi, Mauritania, Somalia and Sudan), and another nine received between than 50% and 75% for adaptation. Yet we note that these countries received among the lowest commitments of climate-related finance, reaching together less that 5% of the total finance targeting climate change. In contrast, six countries received more than 75% of their finance targeting climate change for mitigation (Algeria, Egypt, Gambia, Morocco, Sierra Leone and South Africa). Of these, Egypt, Morocco and South Africa together received about 30% of total climate finance commitments with US$6.9, US$5.9 and US$1.8 billion, respectively. A further twenty countries received more than half for mitigation. The data show no adaptation-related finance commitments to Libya and Equatorial Guinea within the studied period. Total commitments for adaptation were highest in Ethiopia (US$1.4 billion), Kenya (US$1.4 billion), Morocco (US$1.2 billion) and Uganda (US$1.1 billion). The total amounts for finance targeting adaptation, mitigation and both simultaneously per country are provided in Supplementary Annex C.

Figure 3. Total African adaptation- and mitigation-related finance (commitments) by country, 2014–2018 (US$ millions, constant prices). Source: OECD DAC 2020.

Notes: For commitments reported under the Rio Marker methodology, the ‘Principal’ marker for adaptation and for mitigation is used.

It is not obvious from the data why the balance between mitigation and adaptation varies so significantly across the continent, but this is an important angle for future inquiry for countries to develop future funding strategies. An interesting observation about Northern Africa, where 83% of the finance commitments were directed to mitigation, is that around 65% of these mitigation commitments originated from European donors, mainly European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Germany, European Investment Bank and France. One mega-project in Morocco financed primarily by Germany accounts for 26% of the region’s total mitigation finance: The Noor Midelt Solar Power Project is one of the world’s largest solar projects to combine hybrid concentrated solar power and photovoltaic solar. Morocco’s proximity to Europe means it could potentially export significant amounts of renewable power northwards, and in doing so help Europe to achieve its climate neutrality targets. Germany and Morocco also recently signed an agreement to cooperate on green hydrogen, to be produced mostly from solar power. This observation may give weight to findings in other literature that the distribution of development finance is influenced by donor interests (Berthelemy, Citation2006; Clist, Citation2011; Weiler & Sanubi, Citation2019).

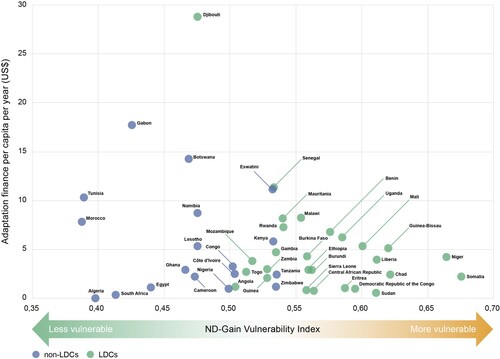

Finance for adaptation is not targeted towards the most vulnerable countries

Per capita, only Djibouti and Gabon received commitments targeting adaptation of more than US$15 per person per year on average, while most countries received less than US$5 per person per year ().

Figure 4. Adaptation-related commitments for each African country, per capita per year, 2014–2018 (US$/person, constant prices), ND-GAIN Vulnerability Index and LDC status (as of September 2020). Source: OECD DAC 2020.

Notes: For the calculation, average population figures over this period for each country were used. South Sudan received roughly US$1 per person but is not included in the figure because the ND-GAIN Index does not include data on its vulnerability. For commitments reported under the Rio Marker methodology, the ‘Principal’ marker for adaptation is used.

Moreover, the data in suggest that funders have not strategically targeted adaptation support towards those African countries with the greatest vulnerability and needs. There is no obvious difference in per capita funding levels between those countries classified as LDCs – which also correspond closely with countries having a higher vulnerability according to the ND-GAIN Index (see Supplementary Annex A for index description) – and those which are not (). Our finding aligns with a growing body of evidence indicating vulnerability is not a strong factor influencing the allocation of adaptation-related finance between countries within Africa (Weiler & Sanubi, Citation2019) or globally (Ciplet et al., Citation2013; Donner et al., Citation2016; Doshi & Garschagen, Citation2020; Saunders, Citation2019).

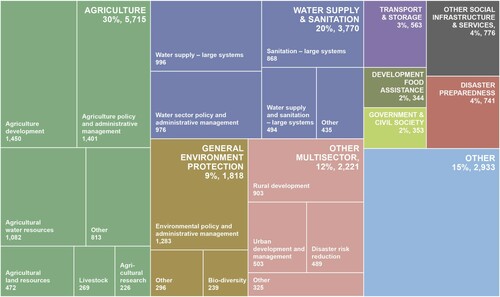

Adaptation-related finance is concentrated in few sectors

Half of all adaptation commitments for Africa were targeted at just two sectors: agriculture; and water supply and sanitation (). We find that support targeting basic development sectors like education or health as a deliberate component of adaptation spending has been negligible in Africa. Similarly, only a small fraction of adaptation-related funding has targeted biodiversity ().

Figure 5. Total international public finance to all of Africa that targets adaptation, by sector (US$ millions, commitments, constant prices), 2014-2018. Source: OECD DAC 2020.

Notes: For commitments reported under the Rio Marker methodology, the ‘Principal’ marker for adaptation is used.

To some extent, finance being targeted largely to two sectors (agriculture and water supply and sanitation) aligns with the climate sensitivity of these sectors in Africa (Niang et al., Citation2014) and their prioritization in adaptation actions outlined in African NDCs (Nyiwul, Citation2019). Yet we know adaptation investments need to target a wide range of sectors to reduce direct and indirect climate risks, boost social and economic resilience, and protect natural ecosystems (Chausson et al., Citation2020; Hallegatte et al., Citation2016). The low support to basic development sectors is observed despite their importance in building long-term resilience and adaptive capacity. This is also despite substantial climate-related health risks and thirty of the countries included in our analysis specifically identifying health as a vulnerable sector in their NDCs (Pauw et al., Citation2017). Similarly, twenty-six African countries identified ecosystems as vulnerable (Pauw et al., Citation2017), yet the amounts of adaptation-related funding for biodiversity are negligible. This is in strong contrast to the growing interest in ecosystem-based adaptation and nature-based solutions to reduce climate risks (United Nations Environment Programme, Citation2021).

In contrast to the more diverse demands of African countries, the relatively concentrated sectoral focus we observe in committed finance may reflect the specific thematic expertize and/or normative perceptions of climate adaptation among the national and international institutions that are most involved in programming adaptation-related finance.

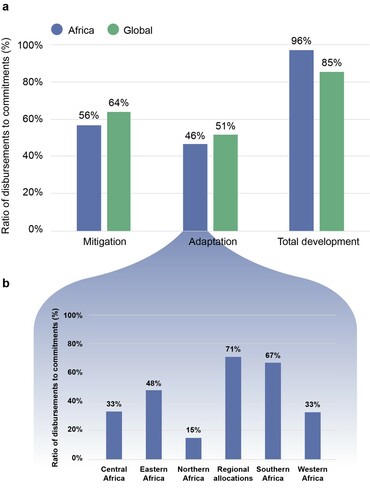

Low disbursement ratios

The analysis presented above is based on commitments, or approved funding amounts. However, international public finance can only make an impact once it is actually disbursed. The ratio of disbursements to commitments over a period of years is one way of assessing whether approved projects are generally being implemented as planned, or whether they are encountering difficulties on the ground.

For all funders, excluding the MDBs (for which disbursement data are unavailable – see Supplementary Annex A), actual disbursements of adaptation-related finance for the period 2014–2018 amounted a total of US$4.7 billion, or only 46% of the corresponding commitments over that period (US$10.1 billion) ((a)). This ratio is below the average of 51% for global adaptation spending, and for several African regions the disbursement ratio is even lower ((b)).

Figure 6. Disbursement ratios for international public finance principally targeting (i) mitigation, (ii) adaptation and (iii) total development. (a) disbursement ratios for Africa (blue) compared to global average (green) (for all funders except MDBs). (b) disbursement ratios for adaptation finance in each African region, 2014–2018 (for all funders except MDBs). Source: OECD DAC 2020.

Note: All disbursement ratio calculations are based on constant prices. Total development covers all development finance support to developing countries reported in Creditor Reporting System (CRS) database, including but not limited to adaptation- and mitigation-related finance. For commitments reported under the Rio Marker methodology, the ‘Principal’ marker for adaptation and for mitigation is used.

The disbursement ratio for adaptation is also lower than the ratio for finance targeting mitigation in Africa (56%). Tellingly, the disbursement ratio for adaptation-related finance in Africa is much lower than the disbursement ratio for all development finance to Africa over the same period (96%). The latter suggests governance system weaknesses and institutional capacity challenges may be impeding the implementation of adaptation projects in particular, compared to development projects in Africa generally.

A limited number of studies examine factors behind low disbursement ratios of development finance in Africa, and several useful insights from these help to explain observed disbursement problems. Grant-based funding appears to have significantly higher disbursement rates than loans (Gaoussou, Citation2011; Gohou & Soumaré, Citation2009; Nkamleu et al., Citation2011), which is notable in this case because we find just over half of adaptation finance in Africa in recent years has been delivered as loans. Countries with lower GDP, projects with lower budgets, and projects that are planned for a long duration seem to experience greater disbursement gap (Gohou & Soumaré, Citation2009; Nkamleu et al., Citation2011). Other factors cited as influencing the degree of disbursement delay include both funders’ and recipients’ politico-economic characteristics, and the absorptive capacity of recipient countries (Gaoussou, Citation2011). In Uganda, low disbursement ratios were found to be associated with deficiencies in procurement planning, failure to follow the conditionality and funding guidelines on procurement, failure by the government to fulfil the counter-part funding requirement in a timely manner, bureaucratic and technical delays from both recipient and funder, and strict donor conditions for aid effectiveness (Ayoki, Citation2008). Finally, a study focusing specifically on adaptation-related finance in Africa highlighted various factors constraining the ability of African countries to implement adaptation – including requirements for co-financing, rigid rules of multilateral climate funds, and inadequate programming capacity within many countries (Omari-Motsumi et al., Citation2019). Our findings indicate such problems are likely having a widespread and tangible negative effect on the ground.

To further understand why disbursement ratios might be so low, we explored the dataset to see whether this may be a general characteristic of the particular sectors where adaptation-related finance is concentrated, and/or an influence of specific funders. In each of the main sectors where adaptation finance is targeted – agriculture, water supply and sanitation, other multi-sector activities and general environment protection – there is a clear pattern of disbursement ratios for adaptation activities being much lower than for activities that do not target adaptation. The observed low disbursement ratios thus seem unrelated to the sectors themselves. Looking at different types of funders, bilateral sources have a higher disbursement ratio for adaptation in Africa (57%) than multilateral sources (14%), which in this case reflects mainly the activities of the climate funds, as the MDBs are excluded. A closer review shows that the GCF has a disbursement ratio of 0% for adaptation-related finance to Africa from 2014–2018, meaning it reports no disbursements at all through the end of 2018. This was confirmed as accurate during a conversation with the GCF Secretariat (pers. comm, October 2020). The Adaptation Fund reports disbursements of around 68% of commitments, the Climate Investment Funds around 75%, and the Global Environment Facility roughly 16%. The low disbursement ratios for some climate funds are especially concerning because they are expected to play a particularly prominent role in supporting climate action and adaptation in particular. Hence, the data reported by the climate funds seem to explain at least part of the observed low disbursement ratio for adaptation-related finance overall in Africa. However, they are not the only or even the main explanation because at present the climate funds only provide a fraction (9%) of overall adaptation-related finance to African countries, suggesting more widespread barriers in adaptation finance systems.

Conclusions

Our findings can help inform a number of key policy decisions in different arenas. Increased finance for climate change adaptation is a central issue for climate justice (that is, sharing the benefits and burdens of climate change based on the principal of common but differentiated responsibilities and from a human rights perspective) (Heffron & McCauley, Citation2018). Our findings confirm concerns expressed by African negotiators in the UNFCCC (African Group, Citation2018) and summaries by African parties to the UNFCCC (Karmorh, Citation2020; Mensah, Citation2020) that inadequate funding is being mobilized to support climate change adaptation in African countries. The annual totals of between US$2.7 and 5.3 billion committed for adaptation in Africa () are well below estimated adaptation costs of US$7-15 billion per year by 2020 (AfDB, Citation2019; Schaeffer et al., Citation2013). We note this estimated range of adaptation costs may well be too low (UNEP, Citation2016), further widening the gap between committed finance and needs. When converted to per capita amounts, committed finance corresponds to an average across the continent of roughly US$5 per person per year, an extremely small amount given the scale of social and economic transformation required for adaptation in a continent such as Africa with such high vulnerability. Adaptation costs for developing countries are estimated to range between USD$17-26 per person per year by 2050 on a low- and high-risk scenario, respectively (Chapagain et al., Citation2020).

The problem of insufficient finance flows for adaptation is further magnified by the observed low disbursement ratios where, excluding MDBs for which data were not available, only 46% of finance has been disbursed for adaptation (). Analysis of disbursement delays of development aid more generally indicates more grant-based finance might help to overcome some of the disbursement problems (Ayoki, Citation2008; Gaoussou, Citation2011; Gohou & Soumaré, Citation2009; Nkamleu et al., Citation2011; Omari-Motsumi et al., Citation2019). From a climate justice perspective, grant-based finance is also more appropriate for highly indebted and vulnerable countries with little responsibility for climate change. There is also the need for multilateral funders to remove or simplify barriers to adaptation finance flows, such as simplifying accreditation processes for direct access to grants by national entities from developing countries and enabling subnational actors in delivery of adaptation action (Omari-Motsumi et al., Citation2019).

Our findings highlight substantial underfunding of adaptation in key risk areas identified by African governments, particularly health and ecosystems (). Increased adaptation funding is needed for these sectors. In addition, cross-sectoral approaches to adaptation planning are needed by funders and governments that give greater weight, and financing, to reducing risk across interconnected sectors affected by climate change, such as the water-energy-food nexus and the biodiversity-health nexus (Liu et al., Citation2018). Establishment of inter-ministerial climate working groups, including ministries of finance, that engage directly with funders is one approach to strengthening cross-sectoral adaptation work and institutional capacity for effective implementation (van Rooij, Citation2014). This cross-sectoral capacity will be critical for successful design and implementation of nature-based solutions (Nesshöver et al., Citation2017).

Our study shows the importance of understanding climate finance at a fine-grained level. The diversity across Africa, in terms of funding amounts and the balance between mitigation and adaptation, provides more nuanced insights into how climate finance is working for individual countries (). At the country-level, we find no clear difference in finance committed to more versus less vulnerable African countries (), highlighting the need for intensifying efforts to provide finance to the most vulnerable countries. Further work is needed to determine the factors driving the patterns our analysis reveals. Donor interests are a potential key factor driving funding to countries and sectors, such as donor priorities influencing financial allocations in projects developing climate information and services in Africa (Vincent et al., Citation2020) or German financing of a large solar power project in Morocco and signing an agreement to cooperate on hydrogen fuel production using solar power. The influence of donor priorities may be stronger for bilateral than multilateral finance for adaptation, highlighting the potential importance of increased contributions by developed countries to multilateral funders and of direct access modalities, such as the Adaptation Fund, for increasing adaptation finance to most vulnerable countries under the Paris Agreement (Omari-Motsumi et al., Citation2019). Our study identifies countries that have been relatively more successful in attracting finance for adaptation compared to the overall climate-related finance, such as Uganda, Mali, Malawi and Gabon, to explore further whether this is the result of more sophisticated domestic adaptation policies and plans, alignment with priorities of the NDC, the funding requirements of specific funders, or strategic use of climate funds by national planners to implement key development projects (infrastructure investment in key sectors like energy and transport might correspond more closely with mitigation outcomes, for example). The data compiled in our study provide information on project titles and can therefore be used to track projects and complement the quantitative analysis with qualitative data from project reports, evaluation reports of funded projects or specific funders, and interviews with relevant stakeholders that can shed light on successful practices as well as barriers to financial disbursements. Given the high number of projects financed across Africa over the five-year period studied in our analysis, we suggest that such analyses are suitable for country and sector specific investigations. Finally, our methodology could be replicated to map finance flows to inform policy discussions in other contexts where adaptation is an urgent priority and where international financial support is critical, such as LDCs globally and small island developing states.

Any estimate of climate-related finance, such as ours, has to recognize that the delineation of climate finance remains contested, particularly with respect to other types of development finance. The picture provided by our analysis does not make a distinction between ‘climate’ and ‘development’ finance, not intending to downplay the significance of this issue (especially for many developing countries) but because there remains no agreed way internationally of doing so, and because in practice funders are presently reporting their climate-related support as a component of their development finance. A narrower definition of ‘climate finance’ for Africa in addition to existing development finance commitments, had it been possible, would have led the analysis to a different estimate. Further, we did not look at private finance, which is now routinely cited as part of the UNFCCC’s finance mobilization targets (UNFCCC, Citation2015); studies that include private finance (Buchner et al., Citation2019; OECD, Citation2020) will naturally arrive at higher total finance estimates – although we note that the portion of this broader finance pool allocated for Africa may be small (c. 3% (Buchner et al., Citation2019)), especially for adaptation where there remains scant data or analysis of private finance. Methodologically, we use a dataset based on reporting by the funders. While this dataset is the most comprehensive and comparable available, we acknowledge openly that it is only one perspective on the mobilization of financial support to help deal with climate risks. There remains, however, no recipient country perspective or dataset with which we might compare the funding reported by donors. Nonetheless, we argue there is still a high value in looking at the OECD data over time, to understand whether financial flows are broadly increasing and to see the breakdown of finance by regions, countries, and sectors. The establishment of standardized reporting mechanisms (UNFCCC, Citation2018) would further enhance the data quality. We also note that although access to finance is a critical enabler of adaptation, the provision and reporting of finance does not guarantee an effective outcome on the ground. Indeed, some projects reported as targeting adaptation may potentially result in increased vulnerability via maladaptation (Eriksen et al., Citation2021). Mapping financial flows as we do, however, is an important contribution – essentially, a precursor – to examine effectiveness at a broader scale.

Five years after the Paris Agreement, and on the road to the global stocktake process, quantitative, country- and sector-level information on where climate finance is flowing (or not) is necessary to inform the policy-relevant assessment work of IPCC, as well as UNFCCC discussions, on the urgent need for scaling-up financial support in a warmer world. These informed discussions are crucial for enabling easier access to finance for African countries as part of a just transition to build resilience and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (37.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OECD DAC’s External Development Finance Statistics on Climate Change at http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/climate-change.htm and in Creditor Reporting System (CRS) at https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CRS1

These databases provide transaction-level data of global development finance. The subsets of these databases extracted and prepared for the analysis of this study are included in the supplementary material.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Grant-equivalent is an estimate, at today’s value of money, of how much is being given away over the life of a financial transaction, compared with a transaction at market terms (OECD, Citationn.d.).

References

- AdaptationWatch. (2015). Toward mutual accountability: The 2015 adaptation finance transparency gap report (No. Policy briefing).

- AfDB. (2019). Analysis of adaptation components of Africa’s nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

- African Group. (2018). Statement by the Republic of Gabon on behalf of the African Group at the Opening Plenary of the 24th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 24), Fourteen session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP14), Third-part of the first session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA 1-3), Subsidiary Body for Implementation Forty-ninth session (SBI 49), Subsidiary Body for Implementation Forty-ninth session (SBSTA 49), and Seventh part of the first session of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement (APA 1.7).

- Ayoki, M. (2008). Causes of slow and low disbursement in donor funded projects in Sub–Saharan Africa: Evidence from Uganda (No. 87106). Institute of Policy Research and Analysis.

- Berthelemy, J.-C. (2006). Bilateral donors’ interest vs. recipients’ development motives in aid allocation: Do ALL donors behave the same? Review of Development Economics, 10(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00311.x

- Buchner, B., Clark, A., Falconer, A., Macquarie, R., Meattle, C., Tolentino, R., & Wetherbee, C. (2019). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019. Climate Policy Initiative.

- Burke, M., Davis, W. M., & Diffenbaugh, N. S. (2018). Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets. Nature, 557(7706), 549–553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0071-9

- Challinor, A. J., Watson, J., Lobell, D. B., Howden, S. M., Smith, D. R., & Chhetri, N. (2014). A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 4(4), 287–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2153

- Chapagain, D., Baarsch, F., Schaeffer, M., & D’haen, S. (2020). Climate change adaptation costs in developing countries: Insights from existing estimates. Climate and Development, 12(10), 934–942. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1711698

- Chausson, A., Turner, B., Seddon, D., Chabaneix, N., Girardin, C. A. J., Kapos, V., Key, I., Roe, D., Smith, A., Woroniecki, S., & Seddon, N. (2020). Mapping the effectiveness of nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation. Global Change Biology, 26(11), 6134–6155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15310

- Ciplet, D., Roberts, J. T., & Khan, M. (2013). The politics of international climate adaptation funding: Justice and divisions in the greenhouse. Global Environmental Politics, 13(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00153

- Clist, P. (2011). 25Years of Aid allocation practice: Whither selectivity? World Development, 39(10), 1724–1734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.04.031

- Costello, A., Abbas, M., Allen, A., Ball, S., Bell, S., Bellamy, R., Friel, S., Groce, N., Johnson, A., Kett, M., Lee, M., Levy, C., Maslin, M., McCoy, D., McGuire, B., Montgomery, H., Napier, D., Pagel, C., Patel, J., … Patterson, C. (2009). Managing the health effects of climate change. The Lancet, 373(9676), 1693–1733. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1

- Donner, S. D., Kandlikar, M., & Webber, S. (2016). Measuring and tracking the flow of climate change adaptation aid to the developing world. Environmental Research Letters, 11(5), 054006. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/5/054006

- Doshi, D., & Garschagen, M. (2020). Understanding adaptation finance allocation: Which factors enable or constrain vulnerable countries to access funding? Sustainability, 12(10), 4308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104308

- Eriksen, S., Schipper, E. L. F., Scoville-Simonds, M., Vincent, K., Adam, H. N., Brooks, N., Harding, B., Khatri, D., Lenaerts, L., Liverman, D., Mills-Novoa, M., Mosberg, M., Movik, S., Muok, B., Nightingale, A., Ojha, H., Sygna, L., Taylor, M., Vogel, C., & West, J. J. (2021). Adaptation interventions and their effect on vulnerability in developing countries: Help, hindrance or irrelevance? World Development, 141, 105383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105383

- Field, C. B., Barros, V. R., & Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Eds.), (2014). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: Working Group II contribution to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.

- Gaoussou, D. (2011). Aid unpredictability and absorptive capacity: Analyzing disbursement delays in Africa. Economics Bulletin, 31(1), 1004–1017.

- Gohou, G., & Soumaré, I. (2009). The impact of project cost on aid disbursement delay: The case of the African Development Bank [Online].

- Hall, N. (2017). What is adaptation to climate change? Epistemic ambiguity in the climate finance system International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9345-6

- Hall, N., & Persson, Å. (2018). Global climate adaptation governance: Why is it not legally binding? European Journal of International Relations, 24(3), 540–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117725157

- Hallegatte, S., Bangalore, M., Bonzanigo, L., Fay, M., Kane, T., Narloch, U., Rozenberg, J., Treguer, D., & Vogt-Schilb, A. (2016). Shock waves: Managing the impacts of climate change on poverty. Climate Change and Development; Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22787 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.World Bank, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0673-5.

- Heffron, R. J., & McCauley, D. (2018). What is the ‘just transition’? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 88, 74–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.016

- Henders, S., Tippmann, R., & Agoumi, A. (2019). International public climate finance flows to the southern and Eastern Mediterranean countries in 2017: Final report. Secretariat of the Union for the Mediterranean.

- Junghans, L., & Harmeling, S. (2012). Different tales from different countries: a first assessment of the OECD “adaptation marker.”.

- Karmorh, B. S. (2020). Liberia’s Climate Finance Experience.

- Khan, M., Robinson, S., Weikmans, R., Ciplet, D., & Roberts, J. T. (2020). Correction to: Twenty-five years of adaptation finance through a climate justice lens. Climatic Change, 161(2), 271–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02614-3

- Knox, J., Hess, T., Daccache, A., & Wheeler, T. (2012). Climate change impacts on crop productivity in Africa and South Asia. Environmental Research Letters, 7(3), 034032. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034032

- Liu, J., Hull, V., Godfray, H. C. J., Tilman, D., Gleick, P., Hoff, H., Pahl-Wostl, C., Xu, Z., Chung, M. G., Sun, J., & Li, S. (2018). Nexus approaches to global sustainable development. Nature Sustainability, 1(9), 466–476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0135-8

- McKee, C., Blampied, C., Mitchell, I., & Rogerson, A. (2020). Revisiting Aid Effectiveness: A New Framework and Set of Measures for Assessing Aid “Quality” (CGDEV Working paper No. 524).

- MDBs. (2019). Joint report on multilateral development banks’ climate finance (Text/HTML). African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank Group, Islamic Development Bank, and World Bank Group, London.

- Mensah, R. (2020). Need-based climate finance for West Africa.

- Michaelowa, A., & Michaelowa, K. (2011). Coding error or statistical embellishment? The political economy of reporting climate Aid. World Development, 39(11), 2010–2020. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.020

- Multilateral Development Bank group. (2020). 2019 Joint report on multilateral development banks’ climate finance. African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank Group, Islamic Development Bank, World Bank Group.

- Nakhooda, S., Caravani, A., Bird, N., & Schalatek, L. (2011). Climate Finance in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Nesshöver, C., Assmuth, T., Irvine, K. N., Rusch, G. M., Waylen, K. A., Delbaere, B., Haase, D., Jones-Walters, L., Keune, H., Kovacs, E., Krauze, K., Külvik, M., Rey, F., van Dijk, J., Vistad, O. I., Wilkinson, M. E., & Wittmer, H. (2017). The science, policy and practice of nature-based solutions: An interdisciplinary perspective. Science of The Total Environment, 579, 1215–1227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.106

- Niang, I., Ruppel, O. C., Abdrabo, M. A., Essel, A., Lennard, C., Padgham, J., & Urquhart, P. (2014). Africa. In V. R. Barros, C. B. Field, D. J. Dokken, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, & L. L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: Regional aspects. Contribution of working group II to the Fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel of climate change (pp. 1199–1265). Cambridge University Press.

- Nkamleu, G. B., Tourino, I., & Edwin, J. (2011). Always late: Measures and determinants of disbursement delays at the African Development Bank. (African Development Bank Working Paper No. 141).

- Nyiwul, L. M. (2019). Climate change mitigation and adaptation in Africa: Strategies, synergies, and constraints. In T. Sequeira, & L. Reis (Eds.), Climate change and global development, contributions to economics (pp. 219–241). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02662-2_11

- OECD. (2011). OECD DAC Rio markers for climate handbook. OECD.

- OECD. (2018). Climate-related development finance data.

- OECD. (2020). Climate finance provided and mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-18, climate finance and the USD 100 billion goal. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/f0773d55-en.

- OECD. n.d. Modernisation of the DAC statistical system. Retrieved August 31, 2021, from https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/modernisation-dac-statistical-system.htm

- Omari-Motsumi, K., Barnett, M., & Schalatek, L. (2019). Broken Connections and Systemic Barriers: Overcoming the Challenge of the ‘Missing Middle’ in Adaptation Finance.

- Pauw, P., Cassanmagnano, D., Mbeva, K., Hein, J., Guarín, A., Brandi, C., Dzebo, A., Adams, K., Atteridge, A., Canales, N., Bock, T., Helms, J., Zalewski, A., Frommé, E., Lindener, A., & Muhammad, D. (2017). NDC Explorer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23661/NDC_EXPLORER_2017_2.0.

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2017). “CO₂ and greenhouse gas emissions”. Our world in data [Online Resource].

- Roggero, M., Bisaro, A., & Villamayor-Tomas, S. (2018). Institutions in the climate adaptation literature: A systematic literature review through the lens of the institutional analysis and development framework. Journal of Institutional Economics, 14(3), 423–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137417000376

- Rosenzweig, C., Elliott, J., Deryng, D., Ruane, A. C., Müller, C., Arneth, A., Boote, K. J., Folberth, C., Glotter, M., Khabarov, N., Neumann, K., Piontek, F., Pugh, T. A. M., Schmid, E., Stehfest, E., Yang, H., & Jones, J. W. (2014). Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(9), 3268–3273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222463110

- Saunders, N. (2019). Climate change adaptation finance: are the most vulnerable nations prioritised? (SEI Working Paper). Stockholm Environment Insitute.

- Schaeffer, M., Baarsch, F., Adams, S., de Bruin, K., De Marez, L., Freitas, S., Hof, A., & Hare, B. (2013). Africa Adaptation Gap Technical Report :Climate-change impacts, adaptation challenges and costs for Africa.

- Schaeffer, M., Baarsch, F., Balo, G., de Bruin, K., Calland, R., Fallasch, F., Melkie, M. E., Verwey, L., Freitas, S., De Marez, L., van Rooij, J., & Hare, B. (2015). Africa’s Adaptation Gap 2 : Bridging the gap – mobilising sources.

- Shukla, P. R., Skea, J., Slade, R., van Diemen, R., Haughey, E., Malley, J., Pathak, M., & Portugal Pereira, J., (Eds.). (2019). Technical Summary, 2019. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)]. In press.

- Thornton, N. (2011). Realising the potential: Making the most of climate change finance in Africa - A synthesis report from six country studies: Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, South Africa and Tanzania. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Thornton, P. K., Jones, P. G., Ericksen, P. J., & Challinor, A. J. (2011). Agriculture and food systems in sub-Saharan Africa in a 4 ° C+ world. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 369(1934), 117–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0246

- UNCTAD. n.d. UN List of Least Developed Countries. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://unctad.org/en/Pages/ALDC/Least%20Developed%20Countries/UN-list-of-Least-Developed-Countries.aspx

- UNEP. (2016). The adaptation finance Gap report 2016. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

- UNFCCC. (2007). Decision 1/CP.13 Bali Action Plan. FCCC/CP/2007/6/Add.1.

- UNFCCC. (2009). Decision 2/CP.15 Copenhagen Accord. FCCC/CP/2009/11/Add. 1.

- UNFCCC. (2010). Decision 1/CP.16 Cancun Agreement. TFCCC/CP/2010/7/Add.1.

- UNFCCC. (2015). Paris Agreement. FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1.

- UNFCCC. (2018). Summary and recommendations by the Standing Committee on Finance on the 2018 Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows. UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance.

- United Nations. (1992). United Nations Framework Convention on climate change.

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2021). Adaptation Gap Report 2020. Nairobi.

- van Rooij, J. (2014). The coordination of climate finance in Zambia. African Climate Finance Hub.

- Vincent, K., Carter, S., Steynor, A., Visman, E., & Wågsæther, K. L. (2020). Addressing power imbalances in co-production. Nature Climate Change, 10(10), 877–878. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00910-w

- Watson, C., & Schalatek, L. (2019). Climate Finance Regional Briefing: Sub-Saharan Africa 4.

- Weikmans, R., & Roberts, J. T. (2019). The international climate finance accounting muddle: Is there hope on the horizon? Climate and Development, 11(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1410087

- Weikmans, R., Timmons Roberts, J., Baum, J., Bustos, M. C., & Durand, A. (2017). Assessing the credibility of how climate adaptation aid projects are categorised. Development in Practice, 27(4), 458–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2017.1307325

- Weiler, F., Klöck, C., & Dornan, M. (2018). Vulnerability, good governance, or donor interests? The allocation of aid for climate change adaptation. World Development, 104, 65–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.11.001

- Weiler, F., & Sanubi, F. A. (2019). Development and climate aid to Africa: Comparing aid allocation models for different aid flows: Entwicklungszusammenarbeit und Klimahilfe für Afrika: Ein Vergleich von Allokationsmodellen für verschiedene Hilfsströme. Africa Spectrum, 54(3), 244–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002039720905598

- World Bank. (2010). The economics of adaptation to climate change: A Synthesis Report. World Bank.

- Zhang, W., & Pan, X. (2016). Study on the demand of climate finance for developing countries based on submitted INDC. Advances in Climate Change Research, 7(1-2), 99–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2016.05.002