ABSTRACT

Elaborate transparency systems are now at the core of the 2015 Paris Agreement, with the assumption that this will enhance accountability, trust, and greater climate policy ambition. Much attention is now being devoted to increasing the capacity of developing countries to comply with climate transparency requirements. Contrary to viewing capacity building merely as a neutral ‘means of implementation’, our point of departure here is that capacity building has the potential to shape the nature and direction of climate transparency to be generated by countries. Key unasked questions are: What kind of transparency is facilitated through capacity-building efforts, and to further what climate policy ends? The potential steering effects of capacity building for transparency remain, in our view, largely unexamined. In addressing this research gap, we undertake a synthesis review of diverse perspectives on the ‘what, how and who’ of capacity building for transparency, as identifiable in (i) academic and grey literature; (ii) policy perspectives advanced by developed and developing countries; and (iii) emerging practices in two prominent capacity building for transparency initiatives. We draw on this three-part review to shed light on the scope and extent of climate transparency (to be) generated by developing countries in practice, with implications for the transformative potential of transparency in global climate governance.

Key policy insights

Transparency about climate actions is central to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Efforts are underway to build capacities of developing countries to comply with transparency requirements.

Rather than merely a neutral ‘means of implementation’, capacity building has the potential to influence the scope and extent of transparency generated by countries.

To date, the focus has remained on building capacities to report on GHG emissions and mitigation, notwithstanding diverse additional priorities.

There is a need for empirical analysis of capacity building’s steering effects in domestic contexts.

1. Introduction

Elaborate transparency systems are at the core of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its 2015 Paris Agreement. These systems aim to ‘make visible’ what countries are doing to implement the Agreement, so as to facilitate accountability, mutual trust and enhanced climate ambition (Campbell-Duruflé, Citation2018; CEW, Citation2018; Ciplet et al., Citation2018; Gupta et al., Citation2021). With transparency becoming ever more central, much attention is being devoted to building the capacity of developing countries to participate in UNFCCC transparency arrangements. Yet, this raises at least two questions about the nature and consequences of the capacity-building efforts targeting transparency:

How does capacity building shape the scope and extent of transparency being generated, and how does this further climate policy ends, both within countries and multilaterally?

What are the political effects of the push to build the capacity of developing countries to generate more transparency around their actions?

To date, these questions have been seldom posed or analysed, in either scholarly literature or in emerging policy practice.

In this article, we take a first step towards addressing this research gap. We do so by undertaking a three-part synthesis review of diverse perspectives on the ‘what, how and who’ of capacity building for transparency: (a) in the academic and grey literature; (b) as articulated by developed and developing countries in submissions to the UNFCCC; and (c) in the design and emerging practices of two prominent capacity building for transparency initiatives.

Our point of departure is that capacity building has the potential to steer the scope and extent of climate transparency generated within countries. Contrary to a mainstream view of capacity building as a neutral ‘means of implementation’, we advance the proposition that it is an intervention with the potential to generate as yet unexamined political steering effects within countries and multilaterally, thus justifying further empirical analysis.

We proceed as follows: Section 2 sketches the historical evolution of climate transparency requirements and associated capacity building for transparency initiatives within the UNFCCC. This section also advances an analytical lens through which to assess potential steering effects of capacity building. Section 3 outlines methods and data sources for our three-part review. Section 4 summarizes the results of our review. Section 5 discusses the implications for the scope and extent of transparency to be generated by developing countries. In Section 6, we conclude by reflecting upon how a broad or narrow scope for transparency may impact its transformative potential in global climate governance.

2. Capacity building for transparency: historical evolution and steering potential

2.1. Evolution of transparency requirements and capacity building within the UNFCCC

Transparency is fundamental to the workings of the UNFCCC (referred to here as ‘Convention’). Indeed, Article 12 of the Convention obligates all Parties to communicate a national inventory of emissions and removals, as well as steps taken to implement the Convention (UN, Citation1992, p. 15). For these reporting obligations, longer time frames are permitted for developing and least developed countries (LDCs), compared to developed country Parties.Footnote1 In addition, developed country PartiesFootnote2 are also required to report on policies and measures that implement their commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, their estimated effects and ‘new and additional financial resources’ that they have provided to developing country Parties (UN, Citation1992, p. 8). Differentiation in reporting requirements between developed and developing country Parties is thus central to the 1992 Convention. Capacity-building support for developing country Parties has evolved in parallel with reporting requirements (UN, Citation1992), with the ‘Consultative Group of Experts on National Communications from Parties not in Annex I to the Convention (CGE)’ established in 1999 to support developing country Parties in the reporting process (UNFCCC, Citation1999).

Since then, transparency provisions have been gradually enhanced for all Parties, developed and developing. The 2007 Bali Action Plan introduced for the first time the principle of ‘measurable, reportable and verifiable’ (MRV) nationally appropriate mitigation actions by developing country Parties (UNFCCC, Citation2007, p. 3). The 2010 Cancun Agreements laid down additional biennial reporting requirements for all Parties, even as these remained differentiated. Notably, developed country Parties ‘should’ submit annual GHG inventories and biennial reports on mitigation actions to achieve quantified economy-wide emission targets and emission reductions, while developing country Parties ‘should’ submit biennial update reports, with updates of national GHG inventories, information on mitigation actions, needs, and support received (UNFCCC, Citation2010). The enhanced reporting requirements for developing countries are explicitly linked to ‘their capabilities and the level of support provided for reporting’ (UNFCCC, Citation2010, p. 11).

A greater convergence of reporting requirements for developed and developing country Parties has now been realized through the ‘Enhanced Transparency Framework of Action and Support’ of the 2015 Paris Agreement (henceforth ‘Enhanced Transparency Framework’ (ETF)). This was preceded by long-standing conflicts over continued differentiation of transparency obligations between developed versus developing countries (Winkler et al., Citation2017). India and Brazil, for example, insisted on continued differentiation, while the United States and other developed countries called for a common framework applicable to all (Gupta & van Asselt, Citation2019). The resulting ETF is a compromise of ‘neither a bifurcated system, nor a single common framework’ (Winkler et al., Citation2017, p. 858).

summarizes these compromises. Most importantly, it points to the mandatory (‘shall’) and recommended (‘should’) reporting requirements for each group, indicating some continued differentiation across developed and developing country Parties. It also includes implementation guidelines for the ETF, agreed in 2018, which specify the information to be reported by all Parties in Biennial Transparency Reports. These reports are due from 2024 onwards, with LDCs and small island developing states (SIDS) permitted to submit them at their discretion.

Table 1. Scope of transparency: reporting under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Furthermore, as a result of arduous negotiations between developed and developing countries, ‘flexibility’ is provided to developing countries – according to their capacities – on some of the ‘shall’ reporting requirements (Gupta & van Asselt, Citation2019; UNFCCC, Citation2015; Van Asselt et al., Citation2016). Going forward, an axis of conflict is how to interpret and institutionalize such flexibility, and with what implications for designing capacity-building initiatives. Some flexibility notwithstanding, the Paris Agreement’s ETF calls for more transparency from developing country Parties than was required in the past (Weikmans et al., Citation2020, p. 515).

2.2. An emerging ecosystem of capacity building for transparency initiatives

As noted, the transparency requirements listed in apply to all countries, while providing flexibility ‘to those developing country Parties that need it in light of their capacities’ (UNFCCC, Citation2015). Capacity building for transparency is thus of increasing importance, with broad agreement that ‘support shall be provided for the building of transparency-related capacity […] on a continuous basis’ (UNFCCC, Citation2015, p. 18, italics added). This signals a change from previous ad-hoc capacity-building support (Winkler et al., Citation2017). To this end, the ‘Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency’ (CBIT) was established in 2015 under the UNFCCC to build capacities of developing country Parties to comply with reporting requirements. Within one year, the CBIT was set-up by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) as a trust fund with donor support from, inter alia, Australia, Germany, and the Netherlands (GEF, Citation2016).

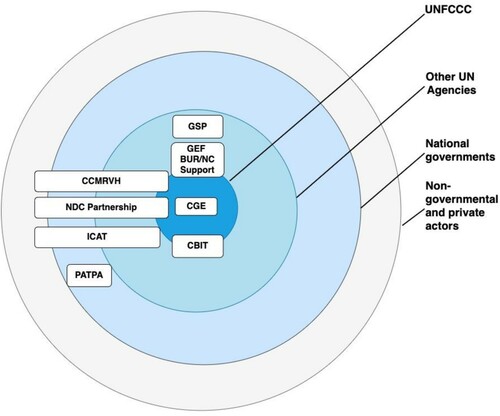

Beyond the CBIT, an entire ecosystem of transparency-related capacity-building initiatives is now emerging under the UNFCCC and at its margins. As one participant in the Durban Forum on Capacity-Building described it, ‘The capacity building landscape is complex and capacity building itself is complex’.Footnote3 We depict this complexity in , which maps major initiatives according to their sources of funding and implementing actors.

Figure 1. Capacity building for transparency initiatives: an emerging ecosystem.

Note: The positioning of the initiatives may vary, depending upon whether donors or implementers are taken as the focal point for placement; the Figure above takes the donors/steering committees as the focal point. Key: (1) CGE – Consultative Group of Experts (formerly Consultant Group of Experts on National Communications from Parties not included in Annex I to the Convention). (2) BUR/NC Support – GEF Enabling Activities for National Communications/Biennial Update Reports: The GEF is an operating entity of the UNFCCC’s financial mechanism and is accountable to the COP. (3) CBIT – Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency: funded by developed countries but implemented through the GEF and its agencies. (4) CCMRVH – Caribbean Cooperative MRV Hub. (5) GSP – Global Support Programme for National Communications/Biennal Update Reports. (6) ICAT – Initiative for Climate Action Transparency: funded by countries and foundations and implemented by different governmental and non-governmental organizations. (7) PATPA – Partnership on Transparency in the Paris Agreement. (8) NDC (Nationally Determined Contributions) Partnership: has governments, multilateral banks and UN agencies in its steering committee and a shared secretariat between the UNFCCC and World Resources Institute, hence ranges across the whole spectrum of actors.

A number of these initiatives existed before the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, such as the Partnership for Transparency in the Paris Agreement (PATPA), formerly called ‘International Partnership on Mitigation and MRV’, which was established in 2010. While some exclusively target transparency (e.g. PATPA), others include it as one of several focal areas (e.g. Partnership for Market Readiness – not shown in ). This latter initiative prepares countries to participate in carbon markets by helping them develop GHG baselines and domestic MRV systems. The Initiative for Climate Action Transparency (ICAT), launched in April 2016, helps countries to assess and report on their climate actions. Other initiatives with transparency elements include the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) Partnership and the Caribbean Cooperative MRV Hub (CCMRVH).

It is likely that more capacity-building initiatives will be established, or existing ones prolonged, in the near future. For example, the German-led International Climate Initiative (IKI) included capacity building for transparency as a funding priority in 2020 (IKI, Citation2019). Additionally, ICAT has now been extended from its original end date of 2021 to 2026. Beyond these multilateral initiatives, there are also numerous bilateral programmes.

2.3. Capacity building as a form of governance or steering: intervention and effects

Having briefly surveyed the evolution of transparency requirements and capacity-building initiatives within and around the UNFCCC, we now propose an analytical lens through which to assess how capacity building may shape the scope and extent of transparency to be generated by developing countries.

Given that generating climate transparency is not only a technical matter but also politically salient, there are likely to be divergent perspectives on the nature of climate transparency to be generated by countries. If so, capacity-building initiatives may push in one or the other direction, depending upon their design and mandate, but also their interpretation and operationalization in specific contexts. Instead of viewing capacity building as a neutral means of implementation for internationally negotiated obligations, we advance the proposition here that it is an intervention that has the potential to steer the scope and direction of climate transparency to be generated by countries in practice.

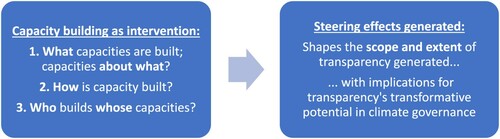

Capacity building can thus be conceptualized as a form of steering (i.e. governance) itself, one which can generate both expected and unexpected effects in how it shapes the scope and extent of climate transparency to be generated by countries. This steering potential can be explored, we further suggest, by examining capacity building as an intervention, specifically through identifying the ‘what, how and who’ of capacity building in both theory and practice.

captures this conceptualization of capacity building as a form of governance that exercises steering effects. Specifically, it delineates the intervention (the ‘what, how and who’ of capacity building) and the resultant effects (the scope and extent of climate transparency generated). By ‘scope’ of transparency, we mean the thematic focus (i.e. transparency relating to GHG emissions, mitigation, adaptation, support given and received, and/or loss and damage). All such scope elements were the subject of extensive political negotiations within the UNFCCC, with the Paris Agreement’s ETF eventually prioritizing some over others (as specified in ). By ‘extent’ of transparency, we mean how much transparency and how often (i.e. detail and frequency of reporting).

serves as the analytical lens through which we structure our three-part review.

3. Synthesis review: methods and data sources

Our three-part synthesis review is based on primary and secondary document analysis. We first undertook a qualitative, critical interpretative review of the academic and grey literature; second, we distilled country perspectives from UNFCCC submissions; and third, we identified emerging practices from documentation produced by two main capacity-building initiatives.

First, for our literature review, we searched Web of Science and Scopus databases with a keyword profile targeting scholarly literature at the intersection of capacity building, transparency and climate change.Footnote4 Search results were reviewed for relevance by the authors. Further scanning of references yielded some seminal, high-impact articles on capacity building from the fields of health and international development that we also included in our review. We also reviewed the growing body of grey literature on capacity building for transparency, which we identified via web searches and through our familiarity with relevant networks and organizations working in this field.

Second, for country perspectives, we reviewed transparency-related submissions from developed and developing country Parties available on the UNFCCC Submission Portal. We used the search word ‘transparency’ with no tags. Of the submissions identified, we selected those relating to guidelines and reporting templates for the Paris Agreement’s ETF. This covered submissions from 2016 to 2019 and yielded 35 developing and 33 developed country submissions, all of which we reviewed.Footnote5

Third, to assess emerging practices of capacity-building initiatives, we reviewed documentation on two main initiatives: CBIT and ICAT. CBIT was selected because it was formally established under the UNFCCC and is the largest initiative in terms of funding and numbers of countries supported. ICAT is a public-private initiative established by donor countries and philanthropies, with an expanding reach in developing countries. For both initiatives, we reviewed a cross-section of documents and material available on their websites. This included CBIT progress reports and project proposals,Footnote6 and ICAT strategy documents and country work programmes.

In addition, we drew on direct observations of the authors from participating in the 9th UNFCCC Durban Forum on Capacity-Building, held online on 5 June 2020,Footnote7 as well as the prior professional engagement of the lead author in the UNEP DTU Partnership,Footnote8 which included: overseeing the CBIT project proposal development of Lao PDR and Thailand; involvement with the ICAT project in Thailand; and support for the CBIT Global Coordination Platform from 2018 to 2020. Finally, our data also includes three written communications and one oral interview with UNEP DTU Partnership staff undertaken from June to July 2020.

4. Capacity building for transparency as intervention: what, how and who?

We present here the findings from our three-part review, organized according to scholarly and grey literature (Section 4.1), country perspectives (Section 4.2) and emerging practices (Section 4.3).

4.1. Perspectives from the scholarly and grey literature

The literature on capacity building for transparency has various strands, with different empirical foci and research approaches. First, there is a body of scholarly literature that discusses capacity building in the context of a broader analysis of UNFCCC transparency requirements (Klinsky & Gupta, Citation2019; Wang & Gao, Citation2018; Weikmans et al., Citation2020; Winkler et al., Citation2017). This literature sheds light on debates around whose capacities are to be built and to serve what ends.

Another, more dominant strand of the literature is more narrowly focused on methods to assess GHG inventory-related capacities in developing countries (Finnegan et al., Citation2014; Neeff et al., Citation2017; Romijn et al., Citation2012; Umemiya et al., Citation2017). Some analysts also create assessment matrices that include, inter alia, capacities to report on adaptation and finance (Prasad & Gupta, Citation2019). These assessments focus on ascertaining what capacities are needed in order for a country to be transparent on these diverse topics, with some also seeking to quantify capacity-building needs.

Yet another strand takes a more qualitative approach, which is also prominently concerned with how capacities are built. A key focus is on lessons learned from case studies (Dagnet et al., Citation2019; Damassa & Elsayed, Citation2013; Ito, Citation2016; Robinson, Citation2018; Umemiya et al., Citation2020). These analyses are often part of the grey literature and are written by practitioner organizations active in this field. Finally, there is critical literature in international development and health studies that goes beyond a focus on transparency, but is relevant because it sees capacity building as a complex process that cannot easily be evaluated or measured (Eade, Citation2007; Labonte & Laverack, Citation2001; VanDeveer & Dabelko, Citation2001).

We draw on these various strands of literature to distil diverse views on the ‘what, how and who’ of capacity building for transparency, as presented below.

4.1.1. What capacities?

With regard to what capacities are to be built, and how diverse capacity-building needs may be quantified, several studies focus on measuring capacities, i.e. they are concerned with capacity-building assessment methods (Finnegan et al., Citation2014; Neeff et al., Citation2017; Prasad & Gupta, Citation2019; Romijn et al., Citation2012; Umemiya et al., Citation2017). Such assessments are considered crucial to track progress and manage resource allocation for capacity-building initiatives. For example, Umemiya et al. (Citation2017) recommend the establishment of a common global monitoring system for GHG inventory capacities to guide capacity-building resources to where they are most needed. Similarly, Neeff et al. (Citation2017) propose the use of a scorecard approach to advise on the allocation of resources for capacity building.

This approach stands in contrast to the more critical literature on capacity building from international development and health studies, which questions the idea of capacity building as a neutral and objective tool to ‘fix’ a problem. As Labonte and Laverack (Citation2001, p. 112) warn, ‘capacity’ is often assumed to be ‘an unproblematic thing or property that can be monitored and measured’, even as detailed analysis suggests that capacity is instead about ‘dynamic qualities’ and ‘social and organizational relationships’. In a similar vein, Eade (Citation2007, p. 637) defines capacity building as ‘an approach to solidarity-based partnerships with an infinite variety of expressions’. From this perspective, it is questionable whether it is feasible to quantitatively assess what capacities are to be developed in a given context.

Along similar lines, there are persisting debates in the capacity-building assessment literature about ‘narrow’ and ‘broad’ capacities that are to be developed. This is what Neeff et al. (Citation2017) call ‘technical’ and ‘functional’ capacities, or Dagnet et al. (Citation2019) refer to as ‘specific’ and ‘governance’ capacities. Narrow capacities refer to a skillset to perform a specific task (e.g. ‘was soil and climate stratification applied?’ from Neeff et al., Citation2017, p. 207). Broad capacities refer to institutional arrangements or resource allocation plans (e.g. ‘is there a continuous improvement plan?’ from Umemiya et al., Citation2017, p. 67). Both broad and narrow perspectives, however, tend to prioritize a specific ‘what’ focus: capacity building for generating GHG inventories.

4.1.2. How to build capacities?

There are also different perspectives in the literature on how capacities should be built, including whether capacity building should be project-based or programmatic. Another is whether the focus should be on building organizational or individual capacities. Country-level preparation of UNFCCC transparency reports has often involved the hiring of international experts, yet this project-based, short-term, and consultant-driven approach has been criticized for, inter alia, undermining local capacities (Khan et al., Citation2020). Robinson (Citation2018, p. 218) argues for capacity building to be geared towards institution building and education. Similarly, Dagnet et al. (Citation2015, p. 29) call for capacity building of ‘organizations and institutional arrangements’ and a ‘move away from the ad hoc, short-term project focus’.

Linked to this, capacity building via universities is considered a promising approach (e.g. Aragon & Tshewang, Citation2019; Robinson, Citation2018; Umemiya et al., Citation2020), as universities are seen as stable institutions that can guarantee some retention of personnel and expertise over time. On this point, Wang and Gao (Citation2018, p. 261) adopt a somewhat different stance, arguing that ‘institutional capacity will mainly be addressed domestically’ and international capacity-building efforts should target ‘technical capacities’. This is echoed by Umemiya et al. (Citation2017, p. 72), who note that international capacity building may not help to improve domestic institutional capacity because it ‘largely requires internal decision-making and coordination’.

Finally, it should be noted that views on long-term, systemic approaches to capacity building in the literature are at odds with timelines for UNFCCC reporting obligations. Dagnet et al. (Citation2019, p. 8) point to this challenge in emphasizing that though capacity building should be long-term, there is a ‘short window of opportunity’ until 2024 for countries to comply with Paris Agreement transparency requirements. In contrast, Wang and Gao (Citation2018, p. 260) foresee a timeline of ‘decades’ before capacities of developing countries can be built.

4.1.3. Who should build whose capacities?

In terms of whose capacity is to be built, two general perspectives are discernible. The first is that capacity assessment methods should guide resources to where the need is greatest (Neeff et al., Citation2017; Umemiya et al., Citation2017). This said, empirical analysis in Asia has shown that developing countries with lower capacities are less likely to receive support (Umemiya et al., Citation2017; Umemiya et al., Citation2020).

A second, more critical view is found in the broader transparency literature. In analysing the link between transparency and accountability, Gupta and van Asselt (Citation2019) note that countries with the lowest capacities are also those least responsible for climate change, an aspect to keep in mind when requiring transparency. Klinsky and Gupta (Citation2019) highlight that an extensive focus on building GHG reporting capacity in developing countries risks deflecting attention away from necessary actions to be taken by the historically biggest emitters. Wang and Gao (Citation2018) also take equity as a vantage point in noting that developing countries might have other priorities, such as combating poverty or health protection, over generating transparency through better climate reporting. They also note that some countries may not aspire to build high levels of transparency-related capacities.

4.2. Country perspectives: developing and developed country views

Turning to our review of country perspectives, our analysis of developing country submissions reveals a clearly and widely expressed need for capacity building to enable participation in UNFCCC transparency arrangements. Some developing countries describe capacity-building support for transparency as ‘the deal-maker of the [Paris Agreement’s] enhanced transparency framework’ (South Africa, Citation2017, p. 2). Developed countries similarly emphasize the importance of capacity building for implementing transparency requirements, yet a focus on capacity building is less central within the transparency submissions of these countries, compared to those of developing countries.

Instead, a key theme in developed country submissions centres on the flexibility to be granted to developing countries in meeting transparency requirements, given ‘their different capacities and starting points’ (Switzerland for EIG, Citation2016, p. 2; see also Norway, Citation2016; Slovakia for EU, Citation2016). Many developed country statements thus offer their view on what ‘flexibility’ means in this context. Countries note, for example, that to generate GHG inventories, IPCC guidelines already permit different reporting tier levels, so there is no need for additional flexibilities here (e.g. Norway, Citation2017a; US, Citation2016). Developing countries making use of the flexibility provision are thus urged to explain how capacity constraints will be overcome (Estonia for EU, Citation2017). A shared view across developed country submissions is that the ‘degree of flexibility of the Parties must gradually diminish’ over time as capacities improve (Korea, Citation2017, p. 2; see also US, Citation2016), a position that developing countries do not necessarily share. As noted earlier, interpreting and operationalizing flexibility thus remains an axis of conflict within UNFCCC transparency arrangements (see also Gupta & van Asselt, Citation2019).

Beyond these broad themes, the submissions reviewed shed light on the ‘what, how and why’ of capacity building for transparency, including where country perspectives diverge.

4.2.1. What capacities?

With regard to what capacities are to be built, the need for capacity building to compile GHG inventories is emphasized by both developed and developing countries. Beyond this, developed countries place slightly more emphasis on mitigation action (including NDC) tracking. Developing countries also call for capacity building to report on adaptation and support, highlighting technical difficulties and lack of guidelines. While most developed countries do not discuss capacity building for adaptation or support much in submissions, there are exemptions. For example, Korea as a developed country notes the importance of reporting on adaptation, while Norway defends the importance of transparency on support.

LDCs and SIDS also emphasize the importance of capacity building for transparency as a way to help secure climate finance or access to carbon markets.

provides an overview and some illustrations of these perspectives.

Table 2. Developing and developed country positions on what capacities should be built.

4.2.2. How to build capacities?

With regard to how capacities should be built, developing countries overwhelmingly prefer a nationally-driven, continuous process. Developed countries see merit in capacity building organized through the CBIT’s project-based approach. Both developing and developed countries emphasize South-South knowledge sharing and learning-by-doing as key to capacity building for transparency (Indonesia, Citation2017; Iran for LMDC Group, Citation2017). In striking contrast to developing countries’ call for continuous capacity building, some developed countries note that ‘support needs should diminish over time’ (e.g. Switzerland, Citation2017, p. 3; see also US, Citation2016), but others, including Australia and the EU, suggest that it should continue.

Both developed and developing countries highlight the importance of support for identifying capacity-building needs, mostly through engagement in UNFCCC-processes such as technical expert reviews. In contrast, South Africa (Citation2019, p. 11) notes that ‘capacity-building needs are best identified by Parties themselves’.

provides an overview and some illustrations of these perspectives.

Table 3. Developing and developed country positions on how capacities should be built.

4.2.3. Who should build whose capacities?

With regard to whose capacities are to be built, all developing country submissions emphasize the need for capacity building for transparency. However, some call attention to countries’ different starting points (Bhutan for LDC Group, Citation2019; Maldives for AOSIS, Citation2016). In a similar vein, Switzerland (Citation2017, p. 3) specifies that capacity building should be ‘targeted to where needs are greatest and more robust information needed’. This notwithstanding, developed countries generally view capacity building as important for all developing countries, with a focus on mandatory reporting elements.

Regarding who should provide funding, most developing countries highlight the importance of multilateral funding, notably through CBIT (e.g. Maldives for AOSIS, Citation2016; Mali for AGN Group, Citation2016). Developed countries also acknowledge the importance of the CBIT but also include bilateral and domestic sources. For developing countries, easy access to funding is also of primary importance.

provides an overview and some illustrations of these perspectives.

Table 4. Developing and developed country positions on who should build whose capacities.

4.3. Capacity building for transparency: key initiatives and emerging practices

We turn here to the ‘what, how and who’ of capacity building for transparency as it is emerging in practice and being operationalized within CBIT and ICAT.

CBIT became functional by 2016, with voluntary donor contributions. It is managed by the GEF and embedded in the GEF’s structures and procedures. ICAT is a multi-stakeholder partnership of two foundationsFootnote9 and the Ministries of Environment of Germany and Italy. It was founded ‘to respond to the critical need of improved transparency and capacity building for evidence-based policymaking under the Paris Agreement’ (ICAT, Citation2019a, p. 1). ICAT develops its own capacity-building impact assessment methodologies, with 10 such methodologies available, and supports its partner countries in applying them. While a general guide for reporting on adaptation in BTRs was also prepared under ICAT (Dale et al., Citation2020), no funds are available for countries to apply this guide.

provides an overview of key insights from our review of CBIT and ICAT. As elaborated there, along with illustrative examples, with regard to the ‘what’ of capacity building, CBIT and ICAT permit a wide scope for transparency-related capacity building in theory, but in practice, GHG inventories and mitigation are prioritized. On the ‘how’, both ICAT and CBIT see the need for a holistic approach, but in practice, projects are still short-term. Regarding the ‘who’, while all countries are eligible for support by CBIT, in practice, the focus is on countries with the least capacities, even as it continually seeks to diversify. ICAT uses somewhat distinct criteria, including emission profiles and existing donor relationships.

Table 5. Capacity building for transparency: emerging practices in CBIT and ICAT.

This section has reviewed academic and grey literature and country perspectives on capacity building for transparency, as well as emerging practices in two main initiatives, with key findings and illustrations synthesized in .

provides an overarching summary and overview of the key findings relating to the ‘what, how, and who’ of capacity building across our three-part review.

Table 6. What, how and who of capacity building for transparency: an overview.

5. Capacity building’s steering effects: shaping scope and extent of transparency?

In our three-part review, we have synthesized diverse perspectives on the ‘what, how and who’ of capacity building for transparency by examining the scholarly and grey literature, country perspectives articulated during UNFCCC negotiations, and emerging practices within two main capacity-building initiatives.

Here we discuss the scope and extent of transparency that such capacity building steers countries towards, i.e. the steering effects, both expected and unexpected.

One important cross-cutting insight (and expected steering effect) is that the scope and mandate of the Paris Agreement’s ETF is driving a focus on GHG inventories and mitigation actions in capacity-building projects across the globe. This is clearly linked to the mandatory nature of these reporting obligations. While this may be unsurprising, it does establish that the politically negotiated scope of the UNFCCC’s mandatory transparency requirements is indeed being institutionalized and diffused to the country-level via capacity-building initiatives.

The mainstream literature on methods to assess capacity (including some grey literature) adheres closely to these UNFCCC mandatory requirements and views capacity-building needs and challenges through this lens, as do developed country perspectives. The emerging practices of capacity building for transparency, as discernible within CBIT and ICAT, also reinforce the prioritization of mandatory reporting obligations. While CBIT and ICAT are quite distinct initiatives, and their concrete impacts in-country remain to be empirically assessed, our assessment of proposals, progress reports and work programmes reveal that they are pushing in similar directions. They both delineate reporting priorities and thereby shape the scope and extent of the transparency (to be) generated by developing countries. CBIT’s approach prioritizes helping countries to fulfil mandatory reporting requirements, with a strong focus on generating and reporting on GHG inventories. Capacity building under ICAT is also focused on mitigation, as evident from this being a prominent focus of its methodologies, success criteria and implementing agencies.

Furthermore, both CBIT and ICAT rely on a project-based approach to capacity building, in contrast to expressed views of developing countries and the literature on the need to go beyond this. In contrast to CBIT, countries receiving support under ICAT are chosen by donors based on emission profile, among others, and funds can be disbursed faster than through CBIT. However, ICAT funds are only a fraction of those available under CBIT. It is also noteworthy that priority for capacity-building support under CBIT is given to LDCs and SIDS, notwithstanding that these countries can submit the biennial transparency reports at their discretion (rather than by 2024, as mandatory for all others) and that their GHG emissions are negligible. While targeting capacity-building support for these countries is vital, the question remains whether a focus on GHG inventories and mitigation reporting is the most fitting for LDCs.

Some strands of scholarly literature do critically interrogate whether the mitigation focus within the Paris Agreement’s ETF is, or should be, a priority for many developing countries, as compared to reporting on adaptation, loss and damage, and/or support needed and received. While the need for capacity building to report on adaptation or support is not entirely missing from the (mainstream) academic literature or from developing country perspectives, it is more marginal than expected, suggesting that the voluntary nature of reporting on these aspects may be influential. To some extent, this is inevitable, given scarce resources and the need to deploy them to comply, first and foremost, with mandatory UNFCCC reporting obligations. In practice, however, this privileges the generation of specific types of transparency, with potential consequences for the climate actions prioritized by these countries. It can result in generating detailed GHG inventories within countries with low emissions and even lower capacities to mitigate, at the expense of building up reporting and assessment capacities on climate vulnerability, adaptation or loss and damage.

An outstanding empirical question then is: What flexibility do countries have in practice to reconcile mandatory reporting requirements centred on mitigation, with other national and local-level needs and priorities? Empirical analysis within countries is needed to determine if adaptation and support assessment and reporting needs are being set aside by countries, in order to deliver on mandatory requirements relating to GHG inventories and mitigation actions, and what role existing capacity-building initiatives and emerging practices have in this. A related empirical question is whether some LDCs and other developing countries regard transparency (and capacity building for transparency) as a means by which to access scarce climate finance, and/or as a prerequisite to participating in carbon markets. This may also privilege a focus on reporting centred on GHG emissions and mitigation actions.

6. Conclusion

Our analysis has interrogated the potential steering effects of capacity building in shaping the scope and extent of transparency (to be) generated by developing countries. This is important because of the assumed centrality of transparency in enhancing global and domestic governance of climate change.

Our review highlights that instead of being merely a ‘neutral means of implementation’, capacity building has the potential to influence highly politically salient decisions about ‘who should make what visible, to whom, and why’ in the contested context of global climate politics. As critical scholarship highlights, transparency’s role in furthering trust, accountability and climate ambition is widely assumed but currently more asserted than empirically demonstrated (Ciplet et al., Citation2018; Gupta et al., Citation2021). In addition, such diverse governance ends – furthering trust, accountability, and climate ambition – have quite distinct implications for the scope of transparency to be generated and from whom, and thus also for associated capacity-building efforts. For example, for transparency to further accountability, a core question would need to be: Who should be accountable to whom, and for what (Gupta & van Asselt, Citation2019), and how should mandatory reporting (and associated capacity building) support this? Should the biggest (historic) emitters be held accountable, and thereby make visible through reporting what they are doing to deliver their fair share of mitigation, in a manner that permits comparability of effort? Such (potentially transformative) transparency is currently not forthcoming within this global context.

Or rather, should all countries merely be held collectively (rather than individually) accountable for making progress on self-selected voluntary commitments, with reporting and capacity building prioritizing this aspect? Should developed countries be held accountable for providing new and additional financial support, and thereby be required to report on this in detail? Or rather, should developing countries be held accountable for implementing commitments conditional on the support of developed countries? These illustrative questions show how the scope of transparency required may vary, depending on the end to be realized, with distinct implications for capacity building. Yet, many of these challenging and politically contested questions around broader climate governance are avoided within UNFCCC transparency arrangements and its prioritization of ever-more fine-grained reporting on emission levels and mitigation actions from all countries, a focus which is then further entrenched via capacity-building efforts.

A distinct aim of transparency may be to facilitate participation in global carbon markets. This again implicates a different scope and extent of desired transparency. Detailed, quantitative information relating to GHG emissions is essential to participating in such markets (Gupta & Mason, Citation2016). Yet, not all countries are enthusiastic about nor equipped to generate such transparency, and market mechanisms are a highly contested topic within UNFCCC negotiations. If so, it becomes important to assess if capacity-building initiatives also push in this direction, since this can further entrench market-based climate governance.

Another aim of transparency may be to promote mutual learning and improved domestic decision-making. To realize this, the scope and extent of transparency would need to be flexible and tailored to the needs of specific countries. Finally, debates not only over scope (the ‘what’) but also the extent of transparency (how much, how often) are politically salient. While a mainstream perspective on transparency sees ever more information from all as always better, a more critical perspective would caution against information overload or irrelevance (Gupta & Mason, Citation2014). Should ever-greater levels of transparency be demanded from all, or only from the top 20 GHG emitting countries? Is the priority to generate quantifiable information about emissions from all (and build capacities to do so), or are available resources better invested in generating information about adaptation (even if not quantifiable), or highly salient and challenging issues, such as loss and damage? A more flexible focus would make capacity-building support for generating transparency more pertinent for LDCs and SIDS, given their low emissions and greater vulnerability to climate impacts, and also given that climate funding from all sources should flow to these country groups as a priority.

That said, it is important to ask an overarching question: whether a predominant focus within global climate governance on the generation of transparency itself risks becoming a distraction, if countries prioritize the reporting on, rather than the taking of, climate actions. This is an important question in the continued assessment of the transformative potential of transparency. Our review of capacity building for transparency provides the context for further in-depth, in-country, empirical analyses of such aspects. It highlights the need to assess the steering effects of capacity-building initiatives that support ever-greater levels of mitigation-related reporting from developing countries, while other politically salient categories – such as reporting on adaptation, support needed and received, or loss and damage – may go under prioritized. As such, it also highlights the need to critically interrogate the still widespread assumption that ever greater transparency is vital to securing relevant and effective climate actions from all.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.9 KB)Acknowledgements

An earlier version was presented at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association. The authors thank Chris Höhne as discussant, Yamide Dagnet and Nathan Cogswell from the World Resources Institute, Heather Jacobs as an independent consultant, and Ina Möller from Wageningen University for useful feedback. We are also grateful to three anonymous reviewers and to editors and guest editors of Climate Policy for useful input that has helped to strengthen the article. Any errors remain our responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Developed countries shall submit the first communication within 6 months of the Convention coming into force for the Party, developing countries within three years, and LDCs at their discretion.

2 In the context of the UNFCCC, developed country Parties are referred to as Annex I Parties and developing country Parties as non-Annex I Parties (see Weikmans and Gupta (Citation2021) for a detailed explanation). For ease of readability, we use the simpler developing and developed country terminology in this article.

3 Participant in the Durban Forum, 5 June 2020, 14:00–17:00, link to recording: https://unfccc.int/durbanforum9.

4 Keyword profiles of literature searches are provided in Section 1 of the supplementary information.

5 The full list of countries reviewed is provided in Section 2 of the supplementary information.

6 Available at https://www.cbitplatform.org/projects.

7 The recording of the Forum is available at: https://unfccc.int/durbanforum9. The Durban Forum’s focus was ‘Capacity-building to support the implementation of Enhanced Transparency Framework under the Paris Agreement – ensuring coherence and coordination of actions and support’ and included participation from UNFCCC secretariat staff, developing countries, capacity-building initiatives and technical experts.

8 UNEP DTU Partnership is a research and advisory institution working on energy, climate and sustainable development for developing countries. One focus area is climate transparency.

9 The ClimateWorks and the Children’s Investment Fund Foundations.

References

- Algeria. (2017). Submission by Algeria on the ad-hoc working group of the Paris Agreement (APA) agenda item 5 “modalities procedures and guidelines on the transparency framework of action and support referred to in article 13 of Paris Agreement PA”. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/591_323_131320674568866228-ALGERIA%20-%20Submission%20on%20APA%20agenda%20item%205%20on%20transparency.pdf

- Aragon, I., & Tshewang, D. (2019). Meeting the enhanced transparency framework: Whats next for the LDCs? (IIED briefing). https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17730IIED.pdf

- Australia. (2016). Submission to the ad hoc working group on the Paris Agreement on the modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/261_281_131219394142343887-Australia%20UNFCCC%20Sub%20Transparency%20final.pdf

- Bhutan for LDC Group. (2019). Submission by Bhutan on behalf of the least developed countries (LDC) group on the work referred to in paragraph 12 of decision 18/CMA. 1 “Modalities, procedures and guidelines (MPGs) for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement”. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/201905061650—LDC%20Submission%20Transparency%20.pdf

- Brazil, Argentina & Uruguay. (2017). Views of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay on APA agenda item 5. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/525_323_131324648255521982-Bra%20Arg%20Uy%20-%20Submission-Art13%20Transparency%20Framework%20FINAL.pdf

- Campbell-Duruflé, C. (2018). Clouds or sunshine in Katowice? Transparency in the Paris Agreement rulebook. Carbon & Climate Law Review, 12(3), 209–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2018/3/7

- Canada. (2016). Canada’s submission on APA item 5 modalities, procedures and guidelines for transparency. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/175_281_131196440875282546-Canada's%20submission%20on%20transparency%2020160929.pdf

- CEW (Clean Energy Wire). (2018). Germany wants transparent global climate reporting to ensure trust. https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/germany-wants-transparent-global-climate-reporting-ensure-trust

- China. (2016). China’s submission on modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework under the Paris Agreement. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/199_281_131197034197619051-Submission%20on%20%20Transparency%20Framework%20China.pdf

- China. (2017). China’s submission on modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/199_323_131318124314697455-China’s Submission on APA Transparency.pdf

- Ciplet, D., Adams, K. M., Weikmans, R., & Roberts, J. T. (2018). The transformative capability of transparency in global environmental governance. Global Environmental Politics, 18(3), 130–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00472

- Costa Rica for AILAC. (2016). Submission by Costa Rica on behalf of the AILAC group of countries composed by Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala, Panama, Paraguay and Peru. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/233_281_131197485029118930-160930 AILAC Submission Transparency 2016.pdf

- Dagnet, Y., Cogswell, N., Bird, N., Bouyé, M., & Rocha, M. (2019). Building capacity for the Paris Agreement’s enhanced transparency framework: What can we learn from countries’ experiences and UNFCCC processes (Working paper). World Resources Institute. https://wriorg.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/building-capacity-paris-agreements-enhanced-transparency-framework.pdf

- Dagnet, Y., Northrop, E., & Tirpak, D. (2015). How to strengthen the institutional architecture for capacity building to support the post-2020 climate regime (Working paper). World Resources Institute. https://files.wri.org/s3fs-public/How_to_Strengthen_the_Institutional_Architecture_for_Capacity_Building_to_Support_the_Post-2020_Climate_Regime.pdf

- Dale, T., Christiansen, L., & Neufeldt, H. (2020). Reporting adaptation through the biennial transparency report: A practical explanation of the guidance. UNEP DTU Partnership, and Initiative for Climate Action Transparency (ICAT). https://climateactiontransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Reporting-adaptation-through-the-biennial-transparency-report_an-explanation-of-the-guidance_ICAT_UNEP-DTU-PARTNERSHIP-min.pdf

- Damassa, T., & Elsayed, S. (2013). From the GHG measurement frontline: A synthesis of non-annex I country national inventory system practices and experiences (Working paper). World Resources Institute. https://files.wri.org/s3fs-public/non_annex_one_country_national_inventory_system_practices_experiences.pdf

- Eade, D. (2007). Capacity building: Who builds whose capacity? Development in Practice, 17(4-5), 630–639. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469807

- Estonia for EU. (2017). Submission by the Republic of Estonia and the European Commission on behalf of the European Union and its Member States. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/783_358_131520095971246495-EE-09-10-APA5 EU Submission on MPGs for the transparency framework.pdf

- Ethiopia for LDC Group. (2017). Submission by Ethiopia on behalf of the least developed countries group on agenda item 5: Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/591_323_131324201825189944-Ethiopia%20on%20behalf%20of%20the%20LDC%20Group%20on%20MPGs%20for%20the%20Transparency%20under%20the%20PA%20-%20Final%20(amended).pdf

- Finnegan, J., Damassa, T., DeAngelis, K., & Levin, K. (2014). Capacity needs for greenhouse gas measurement and performance tracking. https://files.wri.org/s3fs-public/wri14_workingpaper_4c_mapt_synthesis.pdf

- GEF. (2016). Programming directions for the capacity-building initiative for transparency. https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/council-meeting-documents/EN_GEF.C.50.06_CBIT_Programming_Directions.pdf

- GEF. (2019). Progress report on the capacity building initiative for transparency. https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/council-meeting-documents/EN_GEF.C.57.Inf_.06_Progress%20Report%20on%20the%20CBIT.pdf#page=29

- Guatemala for AILAC Group. (2017). Submission by Guatemala on behalf of the AILAC group of countries composed by Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala, Panama, Paraguay and Peru. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/233_323_131328374406197076-170228%20AILAC%20Submission%20Transparency%202017%20vf_P17.pdf

- Gupta, A., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S., Kamil, N., Ching, A., & Bernaz, N. (2021). Performing accountability: Face-to-face account-giving in multilateral climate politics. Climate Policy, 21(5), 616–634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1855098

- Gupta, A., & Mason, M. (2014). A transparency turn in global environmental governance. In A. Gupta & M. Mason (Eds.), Transparency in global environmental governance: Critical perspectives (pp. 3–38). MIT Press.

- Gupta, A., & Mason, M. (2016). Disclosing or obscuring? The politics of transparency in global climate governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 18, 82–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.11.004

- Gupta, A., & van Asselt, H. (2019). Transparency in multilateral climate politics: Furthering (or distracting from) accountability? Regulation & Governance, 13(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12159

- ICAT. (2016). Overview – Initiative for climate action transparency. http://206.123.119.42/~climateaction/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ICAT-Initiative-Overview.pdf

- ICAT. (2019a). Accelerating climate action through enhanced transparency. https://climateactiontransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ICAT-brochure.pdf

- ICAT. (2019b). ICAT long-term work programme. https://climateactiontransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ICAT-Adopted-long-term-work-programme-3.pdf

- ICAT. (2019c). Call for expressions of interest. https://climateactiontransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Call-for-Expressions-of-Interest-to-join-Initiative-for-Climate-Action-Transparency-ICAT.pdf

- ICAT. (2019d). Description of ICAT’s strategic approach. https://climateactiontransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ICAT-Strategy.pdf

- ICAT. (2019e). Initiative for climate action transparency – Adaptation COP 25 – Capacity building day Madrid, 4 December 2019. https://climateactiontransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ICAT-Strategy.pdf

- ICAT. (2020). ICAT strengthens its operations with 2 new implementing partners. Retrieved June 16, 2020, from https://climateactiontransparency.org/icat-strengthens-its-operations-with-two-new-implementing-partners/

- ICAT. (n.d.). Country activities. Retrieved June 16, 2020, from https://climateactiontransparency.org/country-activities/

- IKI. (2019). Funding priorities. https://www.international-climate-initiative.com/fileadmin/Dokumente/skizzenverfahren_2019/Funding_Priorities_Thematic_Selection_Procedure_Nov2019.pdf

- Indonesia. (2017). APA1.2 agenda item 5 – Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/453_323_131385147154337575-Indonesia%20Submission%20on%20APA%20Transparency%20Framework%20-%20FINAL%206%20May%202017.pdf

- Indonesia. (2019). Submission by the Government of Indonesia. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/201906131623—2%20-%20Indonesia%20Submission%20on%20TF%20for%20SBs50%20FINAL.pdf

- Iran for LMDC Group. (2016). Submission of the like-minded developing countries (LMDC) on the work of the ad-hoc working group on the Paris Agreement (APA) under APA agenda item 5. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/214_281_131197742813192855-Mehr%20-%20LMDC%20APA%20item%205%20transparency%20Sep%202016.pdf

- Iran for LMDC Group. (2017). LMDC submission on modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support under the Paris Agreement. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/214_358_131520154933630495-LMDC%20Submission%20on%20Transparency%20-%20on%204%20Oct.pdf

- ISPRA. (n.d.). Initiative for climate action transparency (ICAT). Retrieved July 8, 2020, from https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/en/projects/climate-and-meteo/initiative-for-climate-action-transparency-icat

- Ito, H. (2016). Capacity development on GHG inventories in Asia. In S. Nishioka (Ed.), Enabling Asia to stabilise the climate (pp. 227–249). Springer.

- Japan. (2016). Submission on agenda item 5 of APA by Japan “Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement”. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/112_281_131178804556835124-SUBMISSION ON APA_TRANSPARENCY BY JAPAN_FINAL.pdf

- Japan. (2017). Japan’s submission on APA item 5 modalities, procedures and guidelines for enhanced transparency framework. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/112_323_131329625051304577-APA%20SUBMISSION_TRANSPARENCY_JAPAN(FINAL).pdf

- Khan, M., Mfitumukiza, D., & Huq, S. (2020). Capacity building for implementation of nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 20(4), 499–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1675577

- Klinsky, S., & Gupta, A. (2019). Taming equity in multilateral climate politics: A shift from responsibilities to capacities. In J. Meadowcroft, D. Banister, E. Holden, O. Langhelle, K. Linnerud, & G. Gilpin (Eds.), What next for sustainable development? Our common future at thirty (pp. 159–179). Edward Elgar.

- Korea. (2017). The Republic of Korea’s submission on the modalities, procedures, and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/649_323_131335138802033288-20170309%20ROK%20Submission%20on%20transparency_final_final.pdf

- Labonte, R., & Laverack, G. (2001). Capacity building in health promotion, Part 1: For whom? And for what purpose? Critical Public Health, 11(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590110039838

- Maldives for AOSIS. (2016). Submission by the Republic of Maldives on behalf of the alliance of small island states. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/167_281_131197582830051681-AOSIS%20APA%20Transparency%20Submission.pdf

- Maldives for AOSIS. (2017). Submission by the Republic of Maldives on behalf of the alliance of small island states. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/167_358_131536708118071657-Transparency%20Submission%20-%20FINAL%20-%2023%20Oct%2017.pdf

- Mali for AGN Group. (2016). Modalities, procedures and guidelines, as appropriate, for the transparency of action and support. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/586_281_131198159659539321-AGN%20Submission%20on%20APA%20Item%205.pdf

- Malta for EU. (2017). Submission by the Republic of Malta and the European Commission on behalf of the European Union and its Member States. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/783_323_131324010340848514-MT-02-23-EU Submission Transparancy APA 5 FINAL.pdf

- Neeff, T., Somogyi, Z., Schultheis, C., Mertens, E., Rock, J., Brötz, J., Dunger, K., Oehmichen, K., & Federici, S. (2017). Assessing progress in MRV capacity development: Experience with a scorecard approach. Climate Policy, 17(2), 203–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1075375

- New Zealand. (2017). Submission to the APA on transparency. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/55_323_131322949583094535-New_Zealand_submission_Transparency_23_02_2017_FINAL_PDF.pdf

- Norway. (2016). Norway’s submission on the transparency framework. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/114_281_131216945857736293-Norway_APA%205%20Transparency_rev2310.pdf

- Norway. (2017a). Norway’s submission on APA item 5, modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/114_323_131321426552807883-Submission2_Transparency_Norway.pdf

- Norway. (2017b). Norway’s submission on APA item 5, modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/114_358_131516963646192385-Transparency_Oct17Norway.pdf

- Prasad, S., & Gupta, V. (2019). A capacity building assessment matrix for enhanced transparency in climate reporting: A comprehensive evaluation of Indian efforts. Council on Energy, Environment and Water, New Delhi.

- Robinson, S. A. H. (2018). Capacity building and transparency under Paris. In M. R. Khan, J. T. Roberts, S. Huq, & V. Hoffmeister (Eds.), The Paris framework for climate change capacity building (Vol. 203, No. 222, pp. 203–222). Routledge.

- Romijn, E., Herold, E., Kooistra, L., Murdiyarso, D., & Verchot, L. (2012). Assessing capacities of non-annex I countries for national forest monitoring in the context of REDD+. Environmental Science & Policy, 19-20, 33–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.01.005

- Slovakia for EU. (2016). Submission by the Slovak Republic and the European Commission on behalf of the European Union and its Member States. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/75_281_131203153443541418-SK-10-07-EU%20submission%20on%20APA%205%20transparency.pdf

- South Africa. (2017). Submission by South Africa to the ad hoc working group on the Paris Agreement on transparency of action and support. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/591_323_131338773779079456-Submission%20by%20the%20Republic%20of%20South%20Africa%20on%20Transparency%20of%20Action%20and%20Support.pdf

- South Africa. (2019). Submission by South Africa to the subsidiary body for scientific and technological advice on common tabular and reporting formats, outlines and training programme, being views on the work referred to in paragraph 12 of decision 18/CMA.1 on the modalities, procedures and guidelines for the enhanced transparency framework. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/201905092156—Submission%20by%20South%20Africa%20on%20Transparency.pdf

- Switzerland. (2017). Switzerland’s views on common modalities, procedures and guidelines for the enhanced transparency framework for action and support. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/201_323_131338826077295888-17.03.13_Swiss_Submission_on_Transparency.pdf

- Switzerland for EIG. (2016). EIG’s views on modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/201_281_131212581955644713-EIG%20Transparency%20Submission.pdf

- Umemiya, C., Ikeda, M., & White, M. K. (2020). Lessons learned for future transparency capacity building under the Paris Agreement: A review of greenhouse gas inventory capacity building projects in Viet Nam and Cambodia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 245, 118881. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118881

- Umemiya, C., White, M., Amellina, A., & Shimizu, N. (2017). National greenhouse gas inventory capacity: An assessment of Asian developing countries. Environmental Science & Policy, 78, 66–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.09.008

- UN. (1992). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf

- UNFCCC. (1999). Report of the conference of the parties on its fifth session, held at Bonn from 25 October to 5 November 1999. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/cop5/06a01.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2007). Report of the conference of the parties on its thirteenth session, held in Bali from 3 to 15 December 2007. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2007/cop13/eng/06a01.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2010). Report of the conference of the parties on its sixteenth session, held in Cancun from 29 November to 10 December 2010. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2015). Report of the conference of the parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf#page=2

- US. (2016). United States’ submission on common modalities, procedures and guidelines for the enhanced transparency framework. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/54_281_131197386900680016-U.S.%20Transparency%20Submission.pdf

- Van Asselt, H., Weikmans, R., Roberts, T., & Abeysinghe, A. (2016). Transparency of action and support under the Paris Agreement. European Capacity Building Initiative, Oxford.

- VanDeveer, S. D., & Dabelko, G. D. (2001). It’s capacity, stupid: International assistance and national implementation. Global Environmental Politics, 1(2), 18–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/152638001750336569

- Venezuela for LMDC Group. (2017). LMDC submission on ‘Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in article 13 of the Paris Agreement’. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/591_323_131340502613901594-LMDC%20submission%20on%20Transparency%20MPGs%20Feb%202017%20final.pdf

- Wang, T., & Gao, X. (2018). Reflection and operationalization of the common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities principle in the transparency framework under the international climate change regime. Advances in Climate Change Research, 9(4), 253–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2018.12.004

- Weikmans, R., Asselt, H. V., & Roberts, J. T. (2020). Transparency requirements under the Paris Agreement and their (un)likely impact on strengthening the ambition of nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Climate Policy, 20(4), 511–526. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1695571

- Weikmans, R., & Gupta, A. (2021). Assessing state compliance with multilateral climate transparency requirements: ‘Transparency adherence indices’ and their research and policy implications. Climate Policy, 21(5), 635–651. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.1895705

- Winkler, H., Mantlana, B., & Letete, T. (2017). Transparency of action and support in the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 17(7), 853–872. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1302918