ABSTRACT

The Paris Agreement’s nationally driven structure puts the spotlight on financing strategies at the national level. The role of national funding vehicles in mobilizing climate finance, however, has not received extensive attention. This paper remedies this gap by introducing a novel dataset of national climate funds established in developing countries. The database creates an inventory of national financing vehicles and tracks their major attributes, including scope, legal form, and the host, among others. We show that 39 countries have established national climate funds. These funds seek to access and mobilize finance from various sources, domestic and international. Most of these funds have broad mandates to tackle climate change, while a smaller share has a more targeted, sectoral focus. Funding sources vary from taxes to international aid. The funds offer a limited range of financial instruments, primarily awarding grants. The funds also differ in how integrated they are with overarching climate plans and strategies. We also find that most developing countries use existing budget lines to target finance towards climate change objectives. Only five countries track public expenditure on the basis of dedicated budget codes. This paper contributes to the literature by providing an empirical basis to pursue questions regarding the role and effectiveness of national climate funds. For policymakers, the limited range of instruments at the disposal of many of these national climate funds also suggests a need to ensure that the national climate funds have the design features they need to support the implementation of national policy goals.

Key policy insights

Systematic data on public climate finance are scarce. Most governments do not use climate change codes to track their expenditures related to climate change. Policymakers should adopt practices that will help instil transparency in public expenditure on climate change.

Policymakers have to revisit the design features of national climate funds such as legal form and areas of operation as the wider operating context changes.

Funds accredited with multilateral climate funds are underutilized by fund contributors. The Green Climate Fund’s direct access modality offers one major avenue to foster synergies between national climate funds and multilateral climate funds.

Policymakers have the opportunity to harvest lessons from existing funds and calibrate climate policies accordingly, especially as countries contemplate setting revenue-generating carbon prices.

1. Introduction

Given the importance of avoiding runaway climate change, it has become imperative for developing countries to address climate change through domestic action. How exactly have developing countries gone about financing action on climate change? What are the types of institutional arrangements that they have put in place? An approach of growing popularity is to set up a dedicated fund for climate change. While the most straightforward way might be to use regular government budgets to finance activities on climate change, such an approach may not be the best way to attract climate finance. After all, even amidst international promises for a growing portion of development aid to take the form of budgetary support, even the largest provider of budget support, the European Union, delivered only around 24% of aid in the form of budget support in 2020 (Custer et al., Citation2021; European Commission, Citation2020). This trend is valid for climate finance as well. Most of the climate finance routed to developing countries has not been in the form of budgetary support but rather has been project or programme specific. The trends are similar for both mitigation and adaptation. A national climate fund also makes financing efforts more visible for both donors and recipients.

For the purpose of this study, a national climate fund is a national-level entity engaged in accessing, mobilizing, and coordinating climate finance. This study adopts a broad definition of a national climate fund to reflect the diversity, in nature and in scope, of these funds around the world. A broad definition allows us to include funds that focus on conservation, forestry, clean energy, and energy efficiency as long as climate change is stated as an objective.

For a developing country, the advantages of setting up a dedicated climate fund can be numerous. First, national climate funds can be important precursors to policy instruments. Many developing countries may not be in a situation to formulate and implement textbook style climate mitigation or adaptation policies. National climate funds can help to fill that gap in capacity and enable countries to eventually formulate specialized policy instruments.

A national climate fund can also positively impact distributional aspects of addressing climate change. A persistent concern has been whether climate finance is truly reaching people at the local level. A study estimated that just around 10% of international climate finance was flowing to local communities (Soanes et al., Citation2017). A dedicated climate fund may be better suited to make targeted interventions such as reaching marginalized communities in ways that the regular government machinery may not be able to do so.

Third, there has been a growing push for devolving decision-making from the boards of multilateral funds and agencies down to national and local levels (Caldwell & Larsen, Citation2021). The primary mechanism by which national climate funds better reflect local priorities and engage with a range of stakeholders is through a devolution in decision-making. In countries like Kenya, stakeholders are even included in management committees and boards thereby affording them far greater voice in the programming of climate actions than usually possible via normal budgetary means (Hesse, Citation2016). In another example, the People’s Survival Fund of the Philippines was also created so that frontline communities have better access to funding (Republic of the Philippines, Citation2009). Therefore, national climate funds can serve as ‘direct access entities’ to channel international climate finance while reflecting local priorities.

This paper contributes to our understanding of climate finance by documenting climate finance activity at the national level. It puts forward an original database based on a comprehensive survey of national climate funds in the developing world. It catalogues the characteristics of national climate funds and provides an empirical basis to study how national climate funds vary and whether those variations matter in terms of effectiveness. While there has been some work examining the role of national development banks in facilitating decarbonization (Zhang, Citation2020), a focus on national climate funds themselves has been missing.

By shifting the focus to national financing vehicles and their properties, this paper also complements the extant literature’s focus on global institutions, finance trends and estimates, and the mobilization of resources through carbon markets. For example, scholarly attention has been placed on identifying the sources of finance, estimating finance needs, evaluating international policy responses, and harvesting lessons from climate finance pilot projects (Bhandary et al., Citation2021; Buchner et al., Citation2019; Cui & Huang, Citation2018; Romani & Stern, Citation2013; Stewart et al., Citation2009). Similarly, scholars have highlighted the multiplicity of climate finance initiatives, with some scholars exploring the dynamics shaping how bilateral aid agencies supply climate finance (Keohane & Victor, Citation2011; Pickering et al., Citation2013; Pickering et al., Citation2017). There is extensive work focusing on carbon markets, particularly in regards to the Kyoto Protocol’s carbon offset generation and trading programme, the Clean Development Mechanism. This line of work has helped to highlight the opportunities and challenges in mobilizing finance in the form of offset-based revenue (Kallbekken, Citation2007; Mathy et al., Citation2001; Timilsina et al., Citation2010; Wood et al., Citation2016). Similarly, the design and implementation of results-based payments to incentivize halting deforestation and forest degradation has also gained attention (Agung et al., Citation2014; Angelsen, Citation2008; Brockhaus et al., Citation2017; Di Gregorio et al., Citation2015; Korhonen-Kurki et al., Citation2016). Further, revenue from carbon markets or results-based payments can be a means by which national climate funds raise finance.

This paper builds on scholarship in these areas, but complements the literature by squarely focusing on national level funding vehicles that are established to mobilize and steer finance to support national climate goals. The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines how the dataset on national funds in developing countries was assembled. In Section 3, we highlight major trends and findings. The paper concludes (Section 4) with a distillation of the major findings and identifies areas for further inquiry.

2. Methods and data

We compiled a database of national climate funds using a variety of data sources. Primary source material included documents submitted by countries to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change such as national communications and nationally determined contributions. Given data gaps in these documents, to ensure completeness, we also checked the websites of relevant ministries. Databases of national policies such as the Grantham Institute’s Globe Legislation Study database were also used to supplement information available. Online news sources were also used to help identify national climate funds. Similarly, the websites and annual reports of the funds were used to identify the fund’s various properties.

The database tracks the source of the fund’s finances, where they are housed, scope, enabling legislation, and linkages with the international funds (such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF) or the Adaptation Fund). These attributes help to provide a general overview of the funds. Furthermore, understanding these attributes also paves the way for deeper analyses. Questions surrounding the impact of these funds and their effectiveness are left for further research.

To set national climate funds in the context of wider climate finance approaches, we distinguish between countries that have national climate funds and those that use existing budget lines to finance climate change-related objectives. This additional step helps to place national climate funds in the wider context of domestic public finance.

3. Results and discussion

This section highlights important trends and observations based on the data compiled on national climate funds. The database identifies a total of 46 national climate funds. The database consciously restricted focus to non-OECD countries. The national climate funds are located across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific. Nine of these funds are funded from domestic resources, 30 from domestic and external sources, and 7 are funded from external resources alone. Nine of the 46 funds were designed as general-purpose national climate funds. Four of the 46 funds were established specifically to tackle deforestation and forest degradation. 14 out of 46 funds are independent legal entities. provides a snapshot of the governance structures.

Table 1. Illustrative examples of fund types.

A few key trends are observed. First, there is significant diffusion and learning. Second, what national climate funds focus on (their scope) varies significantly, with some funds bearing comprehensive mandates while others are more targeted. Third, the legal nature of the fund and where it is housed also varies. Finally, while most countries do not systematically track public expenditure on climate change, countries that do have national climate funds display a portfolio or mixed set of approaches to climate finance.

The first wave of climate funds consisted of ad hoc arrangements with their artisanal designs and re-purposed conservation trust funds (Irawan et al., Citation2010). For example, Guyana’s REDD+ Investment Fund (GRIF) was set up to manage funding from Norway in exchange for Guyana reducing emissions from deforestation and/or maintaining its carbon stock. Bangladesh set up two trust funds, one designed to receive international assistance and the second fund channelling domestic resources. The Peruvian Trust Fund for National Parks and Protected Areas (PROFONANPE) expanded its focus to include climate change and enlisted itself as an accredited entity of both the Adaptation Fund and the GCF. These experiments were closely observed by other developing countries considering the question of what financing approaches best suited their own national needs. For example, Rwanda’s national climate fund, FONERWA, explicitly mentions Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Ethiopia as countries that offer lessons on how to design national climate funds (FONERWA, Citation2012). Similarly, Brazil and Bangladesh were among the earliest visible demonstrations of how climate finance could be mobilized by establishing national climate funds.

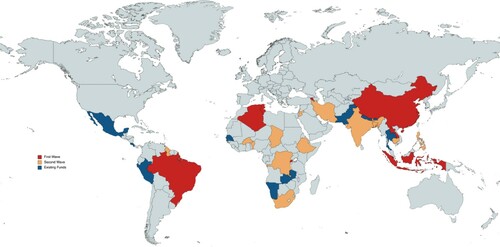

reveals that the first wave of climate funds is now being followed by a second wave. The first wave, coloured in red, captures national climate funds that were established between 2005 and 2009. The second wave, in teal, follows right after the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009 and goes up to the Paris climate summit in 2015 and beyond. The second wave of funds closely follows the commitment by developed countries to mobilize climate finance to support climate action in developing countries and the lead up to the Paris climate summit. The increased activity in the lead up to and immediately following a major international conference is not unique to climate change alone (for example, Gallagher Citation2014). The national climate funds in blue are existing funds that have expanded to include climate change into their mandates.

Figure 1. . The distribution of national climate funds. Note: Maldives, Micronesia, Trinidad and Tobago, and Tuvalu are not visible on the map.

Scope

Most of the national climate funds have their mandates defined in broad terms. Emerging economies are likely to have climate funds that have targeted purposes and bounded scopes. India’s climate funds roughly map along the distinct national missions that form its climate plan. Other funds address specific sectors such as reducing deforestation (Amazon Fund) or are explicitly focused on demonstrating new climate technologies (such as South Africa’s Green Fund). Similarly, the national climate funds that demonstrate new technologies, such as South Africa’s Green Fund, have greater appetite for risk and can venture into testing emerging clean energy technologies for knowledge building. These funds were designed with bounded mandates and were not designed to serve as the primary financial mechanisms to finance a country’s climate change policies.

We can also distinguish between funds that have clearly specified scopes from those that are anchored into national policies more generally. For example, Ethiopia launched the Climate Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) strategy in 2011. As a part of this strategy, the CRGE Facility was set up. This Facility was expected to receive an earmarked 2% share of Ethiopia’s development expenditure. The Facility’s designers also intended the CRGE Facility to serve as the primary vehicle via which international finance is accessed and channelled to climate action. Similarly, both of Bangladesh’s national climate funds, the Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund and the Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund, clearly identify the Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (BCCSAP) as the national policy they were designed to support. Project proponents need to demonstrate how their project applications support the objectives of the BCCSAP. Given that many of these national climate funds were established prior to the formulation of climate policies, the integration of a fund with national climate policies is not a given. In other words, it is challenging to draw a direct connection between an existing national climate fund and the country’s national climate policies.

Legal form

Approximately half of the national climate funds have independent legal personality. The extent of legal independence ranges from fully independent legal personality to an earmarked account in the national budget. An example of the latter is India’s National Clean Energy Fund which receives allocations from the central budget. An interministerial group, with the secretary of the Ministry of Finance as the chair, makes the project approval decisions. National climate funds can also be more autonomous than government-administered funds. For example, the Micronesia Conservation Trust (MCT) is a not-for-profit entity created under Micronesian law. This fund has a governing board that consists of Micronesian officials, civil society, as well as representatives of the donor community.

The data also shows that funds may be given greater legal standing over the course of their lifetimes. For example, the Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund was initially a capacity building programme supported by UNDP. During this interim phase, UNDP played a direct role in the fund’s management. Eventually, the Indonesian government introduced legislation to enable the Ministry of Planning to host this fund on its own.

As shows, national climate funds are governed collaboratively between a number of actors. The Amazon Fund’s structure was unique in involving Amazon states directly in the fund’s governance. Funds vary by the extent to which they incorporate civil society and donor representatives into the governance arrangements.

Table 2. Governance arrangements.

Capitalization

In terms of capitalization and the sources of finance for the national climate funds, two trends are clear from the data. First, approximately 20% of the countries have relied on taxing sources of pollution as the main method to generate the revenue for the funds. For example, countries like India impose a cess on coal, where the Ministry of Finance collects and forwards the revenue raised to the National Clean Energy Fund. Likewise, the Thai Energy Efficiency Revolving Fund is supported by a tax on petrol sales, while the China CDM Fund raises money through a tax on CDM transactions. Second, international donors have contributed to these funds. Donor engagement with these funds ranges from seven donors with the Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund to smaller single donor funds. Pakistan’s Enercon Fund was capitalized with the help of funds from the Global Environment Facility.

Linkages with the Green Climate Fund

Approximately, 20% of the funds have received funding from the GCF. Of the funds in the database, 14 national climate funds have been accredited with the GCF and 11 are already receiving funding. Armenia’s Renewable Resources and Energy Efficiency Fund has not been accredited but is executing a GCF-funded project. As data from the GCF indicates, the bulk of GCF financing is being channelled to countries using international agencies as opposed to national entities directly through the ‘direct access’ modality. The GCF has allocated US $1.7 billion via direct access, forming 38 out of 177 approved projects by GCF (Green Climate Fund, Citationn.d.). Between 2015 and 2020, the GCF approved US $23.4 million in support via its Project Preparation Facility. For example, the South African Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) received a readiness grant from the GCF to improve its financial management and project management systems. National climate funds are natural candidates to serve as direct access entities for the GCF.

Private sector

National climate funds engage with the private sector to varying degrees. A fund’s objectives, the risk tolerance level of its contributors, and the fund’s legal form shape the extent to which it engages with the private sector. Certain funds, such as India’s Partial Risk Guarantee for Energy Efficiency, have been explicitly designed to work with financial institutions to increase the uptake of energy efficiency technologies. The Partial Risk Guarantee Fund for Energy Efficiency provides a guarantee of up to 50% of the loan amount. Financial institutions can seek guarantees from this fund and forward loans to businesses, thereby encouraging the private sector’s engagement in energy efficiency. Similarly, the Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund provided resources that were used to write down the capital costs and allow farmers to install solar irrigation pumps. 23 funds in the database do not have independent legal personality. However, possessing independent legal personality does not automatically entail having the by-laws to incur gains (through revenue reflows) or make losses. As a result, most of these funds are overwhelmingly grant-making institutions which restricts the range of instruments at their disposal and the ability to engage with the private sector.

Portfolio approach

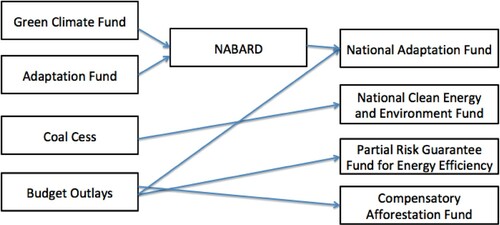

The data show that countries use a mix of national climate funds and other financing arrangements to support climate action. For example, India’s national climate plan consists of eight distinct missions. These eight missions are supported by the following five funds: National Compensatory Afforestation Fund, National Adaptation Fund, Venture Capital Fund for Energy Efficiency, Partial Risk Sharing Facility for Energy Efficiency, and the National Clean Energy Fund (). Apart from these funds, India also uses a range of other financial instruments; this includes use of reverse auctions to procure and support its target for solar power installation; a certificate trading programme to increase cost efficiency of energy efficiency programme (Perform-Achieve-Trade programme); tax credits for energy efficient technologies; and a range of regular budgetary instruments and sources. In addition, the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) in India is an accredited entity to the Adaptation Fund and the GCF, and it has been comparatively successful as a national implementing entity in terms of the number of projects it has been able to fund. NABARD has two GCF projects underway. The GCF’s contribution to these projects is US $34.4 million in grant to groundwater recharge and irrigation project and a US $100 million in loan to a solar rooftop project.

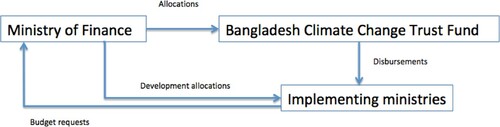

Countries may have a dual-track approach whereby they not only use a national climate fund to disburse funds, but also provide development expenditures to implementing ministries through use of a climate change code. Bangladesh’s domestically-financed trust fund exemplifies this approach as illustrated in . The Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund receives allocations from the treasury. The Trust Fund then allocates these funds to ministries through a competitive process. In parallel, the sectoral ministries request development expenditure from the Ministry of Finance to implement climate-relevant programmes. The integration of climate change into budget request templates, however, followed the creation of the Trust Fund (Bhandary, Citation2021). Because sectoral ministries had engaged with the Trust Fund to apply for grants, there already was some exposure to climate change programming. The alteration of the budget request template to include climate change, therefore, built on the experiences that sectoral ministries gained in implementing climate change projects.

Most countries do not have national climate funds nor do they track their climate related expenditures. Out of the 142 countries examined, 38 countries have national climate funds. Five countries explicitly track climate-related expenditure. These five countries also happen to host national climate funds. The remainder use existing budget codes to target climate change objectives.

4. Conclusion

According to the database introduced in this paper, 38 countries have national climate funds. These funds vary in their scope, their mandate, where they are housed, how they are financed, their legal basis, and the role they play in the overarching climate finance architecture domestically. While the national climate funds are mostly embedded in or derive their mandate from national climate plans and policies, their exact legal nature varies. The legal form of a national climate fund can vary from a fully-fledged independent domestic agency to simply a climate-specific budget code.

Furthermore, most of the countries are not tracking their climate expenditures in a systematic way. Only 5 countries have climate explicit budget codes that track climate change expenditures. Because of the lack of systematic data, estimating climate change expenditure requires one to ascertain the climate relevance of all development expenditures. While it is possible to estimate climate-relevant expenditures (such as through the UNDP and World Bank’s Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Reviews), the inability to specifically track climate finance in national budgets poses major challenges to contributors who aim to avoid the risk that their funds will be diverted to non-climate objectives. It is in this context that national climate funds offer an advantage in visibility and traceability of climate finance.

An overarching question is: why have some funds been more successful than others? Some of the contending explanations for effectiveness include the capacity of the fund manager, alignment of the fund with national climate policies and goals, track record in delivering value, and design features. National climate funds that are created as independent legal entities are more likely to survive. However, their survival does not necessarily translate into success in mobilizing finance. Similarly, the CRGE Facility acquired the interest of donors as the fund gained a stronger track record. Answering this question involves clarifying the objectives of the fund under study (Flynn & Bhandary, Citation2019). For example, a number of national climate funds were designed to help sectoral ministries design and implement climate change projects. As sectoral ministries play a greater role in climate change on their own, the role of the fund, together with our understanding of its effectiveness, will also have to shift.

Further research is needed to shed light on the ability of national climate funds to mobilize international climate finance. As one of the primary theoretical advantages of a national climate fund is to help reduce climate-related aid fragmentation by bringing multiple donors into the same financing platform, we need to investigate the conditions under which national climate funds are able to attract and sustain international interest. For example, Bangladesh’s Climate Change Resilience Fund has seven donors while most of the climate funds have less than three. Second, when funds are accredited with the GCF or the Adaptation Fund, they are likely to receive funding from the GCF but they remain underused by donors. Apart from fiduciary risk, the factors deterring donors from contributing financing to national climate funds needs further investigation. With the GCF incorporating direct access into its programming modality, it is also pertinent to study how national climate funds that are accredited with the GCF can have broader impact.

The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness calls for the use of national systems. As indicated earlier, developing countries can encourage the use of national systems by explicitly tracking climate change-related aid receipts. National climate funds can play this tracking function and help bring greater transparency in the use of climate finance. Similarly, donors must also build on the lessons learned in development finance that calls for using national systems, reducing fragmentation, and supporting country ownership of climate finance. Further research is needed to both identify where national climate funds may have the most impact as well as the trade-offs across budgetary and fund-driven approaches to financing actions on climate change.

The ability of national climate funds to mobilize private capital will also be critical to their effectiveness given the large scale of investments needed to decarbonize economies and promote climate resilience. Most of the national climate funds identified here have acquired legal personality over time. With legal independence, in principle, the funds will be able to work with the private sector in a manner that was not possible when they were embedded wholly within government ministries. The legal form of the national climate funds reflects government priorities at the time of their creation, which was to safeguard finance for climate change. As countries move ahead to strengthen ambition, national climate funds also need to be re-tooled to support national and global climate goals.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (40.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agung, P., Galudra, G., Van Noordwijk, M., & Maryani, R. (2014). Reform or reversal: The impact of REDD+ readiness on forest governance in Indonesia. Climate Policy, 14(6), 748–768. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2014.941317

- Amazon Fund. (2021). Amazon fund: Annual report 2020. http://www.amazonfund.gov.br/export/sites/default/en/.galleries/documentos/rafa/RAFA_2020_en.pdf

- Angelsen, A. (2008). REDD models and baselines. International Forestry Review, 10(3), 465–475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.10.3.465

- Asif, M. (n.d.). Climate change trust fund: Maldives. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/maldives_-_asif_-_nama_workshop_presentation_-_cctf.pdf

- Bhandary, R. R. (2021, May). Climate mainstreaming via national climate funds: The experiences of Bangladesh and Ethiopia. Climate and Development, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.1921686

- Bhandary, R. R., Gallagher, K. S., & Zhang, F. (2021). Climate finance policy in practice: A review of the evidence. Climate Policy, 21(4), 529–545. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1871313

- Brockhaus, M., Korhonen-Kurki, K., Sehring, J., Di Gregorio, M., Assembe-Mvondo, S., Babon, A., Bekele, M., Gebara, M. F., Khatri, D. B., Kambire, H., Kengoum, F., Kweka, D., Menton, M., Moeliono, M., Paudel, N. S., Pham, T. T., Resosudarmo, I. A. P., Sitoe, A., Wunder, S., & Zida, M. (2017). REDD+, transformational change and the promise of performance-based payments: A qualitative comparative analysis. Climate Policy, 17(6), 708–730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1169392

- Buchner, B., Clark, A., Falconer, A., Macquarie, R., Meattle, C., Tolentino, R., & Cooper, W. (2019). Global landscape of climate finance 2019. Climate Policy Initiative. https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-Global-Landscape-of-Climate-Finance.pdf

- Caldwell, M., & Larsen, G. (2021). Improving access to the Green Climate Fund: How the fund can better support developing country institutions. World Resources Institute. https://files.wri.org/d8/s3fs-public/improving-access-green-climate-fund_0.pdf

- Cui, L., & Huang, Y. (2018, January). Exploring the schemes for Green Climate Fund financing: International lessons. World Development, 101, 173–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.08.009

- Custer, S., Sethi, T., Knight, R., Hutchinson, A., Choo, V., & Cheng, M. (2021). Listening to leaders 2021: A report card for development partners in an era of contested cooperation. AidData at the College of William & Mary. https://docs.aiddata.org/ad4/pdfs/Listening_to_Leaders_2021.pdf

- Di Gregorio, M., Brockhaus, M., Cronin, T., Muharrom, E., Mardiah, S., & Santoso, L. (2015). Deadlock or transformational change? Exploring public discourse on REDD+ across seven countries. Global Environmental Politics, 15(4), 63–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00322

- European Commission. (2020). Budget support: Trends and results 2020. European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/budget-support-trends-and-results_en.pdf

- Flynn, C., & Bhandary, R. R. (2019). Designing fit-for-purpose national climate funds: A guidebook for decision-makers. Climate Policy Lab and UNDP. https://sites.tufts.edu/cierp/files/2019/12/NCF_Guidebook.pdf

- FONERWA.. (2012). Government of Rwanda Environment and Climate Change Fund Design Project: Final Report. http://www.fonerwa.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/FONERWA%20-%20Design%20document.pdf.

- FONERWA. (2021). FONERWA: About. FONERWA. http://www.fonerwa.org/about

- Gallagher, K. S. (2014). The globalization of clean energy technology: Lessons from China. Urban and Industrial Environments. The MIT Press.

- Green Climate Fund. (n.d.). GCF in brief: Direct access. Green Climate Fund. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/gcf-brief-direct-access_0.pdf

- Hesse, C. (2016). Decentralising climate finance to reach the most vulnerable. IIED. https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/G04103.pdf

- Irawan, S., Heikens, A., & Petrini, K. (2010). National climate funds: Learning from the experience of Asia-Pacific countries. Discussion Paper. UNDP.

- Kallbekken, S. (2007). Why the CDM will reduce carbon leakage. Climate Policy, 7(3), 197–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2007.9685649

- Keohane, R. O., & Victor, D. G. (2011). The regime complex for climate change. Perspectives on Politics, 9(01), 7–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592710004068

- Korhonen-Kurki, K., Brockhaus, M., Bushley, B. R., Babon, A., Gebara, M. F., Kengoum Djiegni, F., Pham, T. T., Rantala, S., Moeliono, M., Dwisatrio, B., & Maharani, C. (2016). Coordination and cross-sectoral integration in REDD+: Experiences from seven countries. Climate and Development, 8(5), 458–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1050979

- Mathy, S., Hourcade, J.-C., & de Gouvello, C. (2001). Clean development mechanism: Leverage for development? Climate Policy, 1(2), 251–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3763/cpol.2001.0125

- MOFED. (n.d.). Climate resilient Green economy facility. MOFED. https://www.mofed.gov.et/programmes-projects/crge-facility/

- Pickering, J., Betzold, C., & Skovgaard, J. (2017). Special issue: Managing fragmentation and complexity in the emerging system of international climate finance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9349-2

- Pickering, J., Jotzo, F., & Wood, P. J. (2013). Splitting the difference in global climate finance: Are fragmentation and legitimacy mutually exclusive? CCEP Working Paper. Centre for Climate Economics & Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University. http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/eenccepwp/1308.htm

- Republic of the Philippines. (2009). An act mainstreaming climate change into government policy formulations, establishing the framework strategy and the program on climate change, creating for this purpose the climate change commission, and for other purposes. https://climate.gov.ph/public/ckfinder/userfiles/files/Knowledge/RA%209729.pdf

- Romani, M., & Stern, N. (2013). Sources of finance for climate action: Principles and options for implementation mechanisms in this decade. In E. F. Haites (Ed.), International climate finance (pp. 117–134). Routledge.

- Soanes, M., Rai, N., Steele, P., Shakya, C., & Macgregor, J. (2017). Delivering real change: Getting international cliamte finance to the local level. IIED. https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10178IIED.pdf

- Stewart, R. B., Kingsbury, B., & Rudyk, B. (Eds.). (2009). Climate finance: Regulatory and funding strategies for climate change and global development. New York University Press; New York University Abu Dhabi Institute.

- Timilsina, G. R., de Gouvello, C., Thioye, M., & Dayo, F. B. (2010). Clean development mechanism potential and challenges in sub-Saharan Africa. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 15(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-009-9206-5

- Wood, B. T., Sallu, S. M., & Paavola, J. (2016). Can CDM finance energy access in least developed countries? Evidence from Tanzania. Climate Policy, 16(4), 456–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1027166

- Zhang, F. (2020, December). Leaders and followers in finance mobilization for renewable energy in Germany and China. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 37, 203–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.08.005