ABSTRACT

Major banks are facing increased public pressure to reduce financing for fossil fuel projects. In this decade of action for the UN Sustainable Development Goals (with a focus on SDG 13 – climate action), all sectors, including the financial sector, are urged to recognize the ways in which they impact these goals and how they can best contribute to their realization. But how are the top 10 most active banks in financing the fossil fuel industry responding to this pressure? Using qualitative textual analysis of these banks’ annual reports and a proposed categorization of how banks are talking about climate change, we highlight how these banks see their role in reducing climate impacts through their financing and whether their response has evolved since the Paris Agreement. We find that while these banks are stating an increasing number of climate change actions since the introduction of the Paris Agreement, there are few clear commitments in relation to their financing of fossil fuels. This absence of commitments in the annual reports may reflect an absence of critical reflection on their responsibility for financing climate change.

Key policy insights

Climate-related financial disclosures should target banks’ climate impact regarding their client financing; most importantly this should be done in a clear, contextualized way so that regulators and the public can hold the banks accountable based on their disclosures.

Effective policies need to explicitly consider how banks should measure and reduce climate impacts in a way that is comparable, aligned with the Paris Agreement, and in relation to banks’ credit financing operations to clients (not only from the direct operations of a bank, as has been the focus of banks’ commitments against climate change to date).

Legislation mandating human rights and environmental due diligence with explicit considerations in relation to climate change is an example of a policy that would require banks to consider a broader scope of their impact assessment and disclosure reporting which could potentially establish clearer claims for remedies by impacted communities.

Introduction

Despite significant pressure on people to reduce their impact on climate change, from flying less to buying second-hand goods and generally reducing consumerism, the financial sector continues to finance fossil fuels and carbon-intensive industries. The 2020 Banking on Climate Change report identifies the top 10 banks most involved in fossil fuel financing, estimating they have provided USD 1.493 trillion to fossil fuel companies from 2016 to 2019 (Kirch et al., Citation2020).

The Paris Agreement sets a long-term temperature goal that was agreed internationally, covering all countries and greenhouse gas emissions. Since the agreement was adopted in 2015, arguably all public and private actors, including banks, knew that within the coming decades carbon emissions will need to be reduced drastically, and further, that net-zero targets had to be set and reached by midcentury, to achieve the more ambitious temperature goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C.

The public is also increasingly raising concerns about banks’ financing of fossil fuels. Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) are leading calls to action against banks and investment companies for their role in the climate crisis. For example, Fossil Banks No Thanks, led by Bank Track in association with a number of other environmental organizations, is a significant media and education campaign against banks’ financing of fossil fuels (Fossil Banks No Thanks, Citationn.d.). Another coalition calling on banks to divest from fossil fuels and deforestation is Stop the Money Pipeline, which uses protests and calls for people to take their money out of these institutions. They argue: ‘If we stop the flow of money, we can stop the flow of oil’ (Stop the Money Pipeline, Citationn.d.). This public pressure spotlights the financial sector as a key enabler of climate change that should be held accountable for its flow of money into fossil fuels.

Behind these arguments is a claim that businesses, including banks, are in some way responsible for mitigation actions in relation to the harms in which they are involved (beyond legal claims against the banks). Furthermore, this claim seems to appeal to two broad distinctions of moral responsibility for remediation that are widely accepted among ethical and political theorists: forward-looking and backward-looking responsibilities. These two types of responsibilities aim to establish principles for responsibility by answering the following two basic questions: who can do something about the problem and who caused it (Miller, Citation2001).

In terms of forward-looking responsibility, it can be argued that banks have the capacity to significantly help reduce the amount of fossil fuels produced in their capacity to provide or not provide finance to the fossil fuel industry. Furthermore, their role as a bank can be argued to lead to certain obligations to mitigate climate change. Following the global financial crisis in 2008, new literature emerged on both the moral and professional responsibility of banks in society. This literature highlights bankś public responsibility to: 1) ensure efficiency in the process of financial payments; 2) consider the financial well-being of their clients over the self-interest of the financial firm; and 3) assess and manage risks, including the risk of systemic harms to society (Graafland & van de Ven, Citation2011; Herzog, Citation2019). As climate change is considered a source of significant systemic risk to society as a whole as well as to the functioning of the financial system, mitigating climate change would be within a bank’s responsibility to society. Therefore, banks have a special role that leads to a strong claim of responsibility for mitigating climate change.

In terms of backward-looking or causal responsibility, because banks contribute to the continued production of fossil fuels, this implies they should stop this contribution by ending their finance to these industries. Similar arguments on banks’ contribution to harms can be seen in discussions on business and human rights (Discussion Paper: Working Group Enabling Remediation, Citation2019; Kinley, Citation2018; Ruggie, Citation2017; Toft, Citation2020; UN Human Rights Council, Citation2011). These sources of responsibility are also reflected in the public pressure exerted today on the finance sector to change its practices.

With these concepts of forward- and backward-looking responsibility in mind, we aim to see if these banks, who channel a significant amount of financing to the fossil fuel industry, acknowledge these claims and whether they are publicly discussing specific commitments to mitigate climate change, hence reflecting on these responsibilities.

To that end, we qualitatively review the annual reports of the top 10 banks most active in financing the fossil fuel industry to understand the ways in which they are discussing climate change. While it is beyond the scope of this study to evaluate the banks’ activities in relation to their effectiveness in mitigating climate change, we expect that the statements reviewed in these annual reports will provide significant insight into how these banks are reflecting on their role as an actor to mitigate climate change. We highlight trends and categories of statements found in the annual reports, and we consider whether these statements can be read as banks’ responding to any claims of their responsibility for remediating their impacts on climate change. More specifically, we aim to answer three questions: (1) How are banks that are the most active in financing the fossil fuel industry discussing climate change in their annual reports? (2) Has this narrative across these leading fossil fuel financing actors changed over time since the introduction of the Paris Agreement? (3) How are these banks responding to the publicly suggested claims of responsibility for taking action against climate change?

Our focus is on large commercial banks, not on private equity investors nor on large institutional investors such as pension funds. There is a broad literature looking at corporate social responsibility aspects of investments in the fossil fuel industry (or in environmentally or socially controversial industries more broadly) and subsequent focus on evaluating climate risks in investment portfolios, but less discussion has focused on commercial banks that finance the fossil fuel industry in various ways (Krueger et al., Citation2020; Sandberg, Citation2011; Sandbu, Citation2012; ‘Våra Fossila Pensionspengar,’ Citation2020). Understanding how these banks act and consider their role in relation to climate change is important from a policy perspective, especially when considering the use and design of sustainability disclosures, due diligence and relevant indicators as part of effective climate policy packages.

Methodological approach

Our analysis includes the annual reportsFootnote1 from 2015 to 2019 for the world’s 10 largest banks by their level of financing fossil fuels following from the 2020 Banking on Climate Change report (see Figure S.1 in Supplementary Material (SM)) (Kirch et al., Citation2020).

In the first step of the analysis, we conducted qualitative data analysis using the research software ATLAS.ti. Through an iterative process, we identified and highlighted climate change related quotations found in the annual reports, starting with an autocoded word search.Footnote2 The results from the word search were used as an indication of relevant sections in the annual reports. We then reviewed these sections in detail and manually identified quotations for further analysis. Quotations are defined as segments of text in which the bank describes the same issue or topic.Footnote3

As a part of this qualitative review, we mapped the quotations by topic and by year for each bank to analyze trends in the substantive content of these quotations and how they reflect the ways in which banks are considering their responsibility for mitigating climate change. Through this process, we identified similar quotations in terms of content from banks in their annual reports throughout the years. We could also see how often the same quotations were used or how updates of quotations evolved year after year (see SM Figure S.2 for an example of mapping for one bank).

In the second step of the analysis, we manually classified how banks describe their activities in relation to climate change, and whether these descriptions have changed over time based on the quotations and topics identified and extracted from ATLAS.ti. Through our review, we detected that the quotations and topics could be grouped into four main categories: general statements, opportunities, statements related to risk, or commitments. These categories help to disentangle the overall trends of how banks talk about climate change in their annual reports and, moreover, they can be used to enhance our understanding of how banks are reflecting on their responsibility for climate change. We define each category as follows:

General. The bank provides a general statement about climate change, a low-carbon transition, or its role in society, with little to no description (or a vague summary) of the activities that the bank will do.

Opportunity. The bank describes an activity related to climate change that creates further business opportunities and financial benefit for the bank. This activity could be considered or written as an action to mitigate climate change, such as the bank’s promotion of green bonds and financing green technologies, but the activity itself would not target direct emissions reductions in the bank’s operations or financing activities. Importantly, what we categorize as an opportunity has the potential for a direct opportunity for revenue in a way that a commitment does not.

Risk. The bank describes how climate change creates specific risks for its operations or its business activities.

Commitment. The bank describes an activity that it is taking or will take to address climate change with the potential to directly impact emissions, through (1) emissions reductions, (2) measurement or disclosure of climate impact of its own operations or its financial operations, or (3) collective initiatives to promote sustainability. While this activity may create an indirect financial benefit if more stringent policies and regulations are implemented in the long run or through improving a bank’s public reputation, the activity itself may not directly create financial benefit for the bank or may even hinder business opportunities in the short run.

Following from identifying these categories, we reviewed each quotation found in the annual reports to identify unique statements within the quotations, and we assigned each of these statements to one of the four categories by bank and by year (see SM Figure S.3 for an example breakdown of a quotation). We identified a total of 541 relevant statements in our review among the top 10 banks across the full five year period from 2015 through 2019.

In the third and final step of the analysis, we reviewed the categorized statements for their reflection of responsibility claims. We would, for example, expect a statement categorized as a commitment to more directly reflect the bank’s responsibility for climate change than a statement categorized as an opportunity, since a commitment would signal (either explicitly or implicitly through the noted action) that the bank acknowledges either a forward-looking or backward-looking consideration of their responsibility to mitigate climate change. This is further elaborated on in the discussion of banks’ statements and their indication of responsibility below.

In relation to our methodology, it can be useful to comment on the development of text analysis using artificial intelligence in the form of natural language processing (NLP). An interesting example of a recent study using the language representation model, BERTFootnote4, is Bingler et al., Citation2021. The authors use NLP to analyze the effectiveness of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) on risk management. An NLP approach is especially suitable if there are clearly pre-defined categories. In our study, we did not have any preconceived expectations of what banks would write in relation to climate change, and most importantly, we did not have predefined categories to systematize the statements and actions described in the banks’ annual reports. However, the resulting data set of manually annotated statements and actions can be used in future research to train language representation models to enhance accuracy in analyzing text produced by banks specifically. In addition, our categorization offers a useful framework for how banks talk about climate change.

Results and discussion

General observations

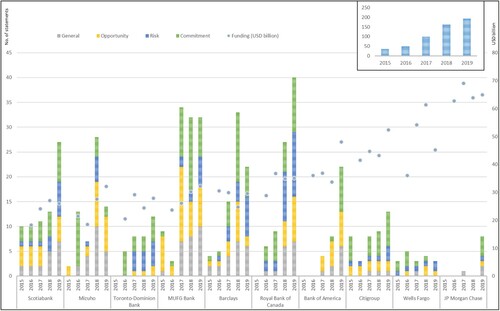

Based on the categories of statements from the annual reports, provides a snapshot of the differences among and within each bank over five years. When looking at the number of statements within annual reports, the top 10 most active banks in financing fossil fuels seem to have been affected by the global discourse about climate change. They clearly talk more about climate change in their annual reports in 2019 than in 2015, and there is an increasing trend for all four categories of statements over time (see smaller diagram in the upper right corner of ).

Figure 1. Top 10 banks listed in accordance to their average size of funding of the fossil fuel industry 2016-2019, smallest to largest. Left-side axis (referring to the bars): Category and number of statements in relation to climate change from the banks’ annual reports. Right-side axis (referring to the dots): Yearly funding of fossil fuel funding, USD billion.

According to , Scotia Bank has the smallest funding toward the fossil fuel industry and JP Morgan Chase the largest. We note that even if the number of total observations are low, there seems to be a negative correlation between number of statements related to climate change and funding of the fossil fuel industry.Footnote5 Looking at differences among the banks, MUFG had the most statements related to climate change in its annual reports over the five-year period from 2015 to 2019, and JP Morgan had by far the fewest.

The number of statements and the trends by category clearly differs among the different banks. This shows that even the top 10 most active banks in financing fossil fuels differ in how much they talk about climate change in their annual reports, with some doing so fairly regularly while others barely mention the issue. While we do not attempt to quantify the effects of these statements or argue that a bank with more statements is necessarily more effective in its work against climate change, we do think that these statements (and their frequency in annual reports) mean something in how banks are transparently responding to their role to take action on climate change.

Public pressure for banks to act on climate change and banks’ expectations about future regulation are likely to affect their priorities and strategies in relation to climate change. While this study does not aim to establish if the potential variation of financing by banks is due to jurisdictional legislation, some initial observations can be made. In Canada, Japan, the UK and the US, the only mandatory climate disclosure legislation in effect is the UK Companies Act, which has required reporting on greenhouse gas emissions from UK quoted companies since 2013 (Congressional Research Service, Citation2019; Erlichman & Langlois, Citation2021; Japan’s Corporate Governance Code: Seeking Sustainable Corporate Growth and Increased Corporate Value over the Mid- to Long-Term, Citation2021; Measuring and Reporting Environmental Impacts: Guidance for Businesses, Citation2019; Mosnier, Citation2021). Furthermore, the US banks on the top 10 list stand out in our analysis as having very few statements in relation to climate change in their annual reports. In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission does not require publicly traded companies to disclose climate change risks in their annual reports unless the potential costs for the company are ‘material’ (Congressional Research Service, Citation2019).

Yet, emerging notions of good practice are being developed around the world. For example, in 2018, the EU (and its member states) published the Commission Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth, which included establishing a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, to classify sustainable activities under an EU taxonomy, and to harmonize discussion of sustainability risk and disclosure standards (Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth, Citation2018; Sustainable Finance, Citationn.d.). Furthermore, we have observed policy discussions in 2020 and 2021 of a need for stronger climate-related disclosures in Japan, the US, the UK, and Canada (Climate-Related Reporting Requirements, Citation2021; Erlichman & Langlois, Citation2021; Herren Lee, Citation2021; Japan’s Corporate Governance Code: Seeking Sustainable Corporate Growth and Increased Corporate Value over the Mid- to Long-Term, Citation2021; Mosnier, Citation2021).

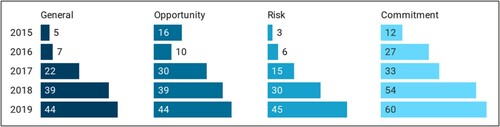

Turning to the type of statements, shows an increase in all four categories of statements over the five-year period across these 10 banks.

Figure 2. Numbers of climate change statements, by type, in the annual reports of the ‘top 10 banks’ by year.

We note that talking about risks increased substantially from 2017–2019. This finding may be connected to the 2017 introduction of recommendations from the TCFD, which has a specific focus on banks identifying climate risk and disclosing their climate-related financial risk management efforts (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, n.d.). Yet, despite the increase in the number of statements pertaining to risk across the five years and the assumption that pertinent risks should be disclosed in annual reports, our textual analysis shows there is little discussion of how climate change might affect the bank in relation to its societal impact. Instead, climate risks seem to be broadly identified as a perceived credit risk in relation to clients defaulting on loans or as a risk impacting the bank’s own operations, such as risks to properties and investments, for example, risks that extreme weather will interrupt their operations. There is also a recognition that potential climate change regulations and guidance may affect their operations. These observations align with recent surveys and analysis of climate disclosure reports on the lack of sufficient detail in corporate climate-related financial risk disclosures in general (Bingler et al., Citation2021; Hell et al., Citation2020; Nelson et al., Citation2021; Paisley & Nelson, Citation2020). For example, in the most recent EY Global Climate Risk Disclosure Barometer, which reviews TCFD disclosures of public companies, banks on average addressed 77% of TCFD recommendations in their disclosures in some way, but were marked with an average of only 46% in terms of quality of the disclosure (Nelson et al., Citation2021).

Discussion of banks’ statements and their indication of responsibility

While the descriptive overall analysis shows that banks clearly talk more about climate change in 2019 than in 2015, the textual analysis provides a more in-depth look into how banks seem to respond to the claim of responsibility for taking action against climate change. Here we will take each category of statement in turn and reflect on if and how the reviewed statements acknowledge a bank’s responsibility to mitigate climate change.

Continuing the discussion of risk, we noted above that the primary ways in which banks discuss climate risks are in relation to credit, regulatory and operational risks. The risk of climate change is also centred around the banks’ own operations, and despite a number of voluntary initiatives incentivizing banks to review and disclose risks related to climate change, there is little reflection of key performance indicators (KPIs) or standards to measure and track banks’ impact on climate change through their financing in terms of risk management. We did not observe any substantial discussion of responsibility in relation to risks. In addition, this focus on the banks’ own business partially contradicts the proposed role of banks in society, which should account for systemic harms to society due to or related to their service. Proposed regulations of climate risk disclosures, as discussed above, could lead to a stronger connection between responsibility and risk management if enforced.

Statements in the opportunity category could be seen to reflect how a bank responds to its responsibility to mitigate climate change, at least in the capacity that it has. Opportunities are primarily products or services that promote a low-carbon economy or sustainable financing. The statements note new products that will help in the low-carbon transition including green bonds, green investments, and consultancy services. In a number of instances, the general statements discussing the role of the bank in society and opportunity statements are very close together, which further affirms this assumption that the bank is fulfilling its responsibility in mitigating climate change by taking these types of actions. Certainly, these actions can help mitigate climate change, but they are ultimately opportunities that can benefit a bank’s bottom line, and if the banks do not complement such opportunities with clear commitments and strategies that aim to phase out financing the fossil fuel industry, then climate targets will not be met. This calls into question how an action that will directly benefit the bank should be considered and if it can be seen as a step the bank is taking to assume sufficient responsibility for remediation (Furrer et al., Citation2011). Banks seem to see opportunities as the primary way of engaging with clients in relation to climate change. While this may be a relevant step in promoting sustainability, it still does not address the causal, negative contribution they have had and continue to have on the climate via their main financing activities.

In an ideal discussion of responsibility and climate change, we anticipated a strong connection would exist between a reflection of responsibility and commitments made by the bank. From our analysis, however, we can observe that while there is an acknowledgment that banks should not causally contribute to climate change through their own direct operations, there is a lack of commitments in relation to their business activities. This indicates a lack of response to their causal responsibility based on their financing of activities causing climate change. Commitments are present in the annual reports but are generally not related to how the banks finance their clients.

Most commitments and their KPIs are related to reducing the banks’ operational emissions (i.e. through their building’s use of electricity) or point to collective initiatives in which they participate or support. Figure S.5. in the SM summarizes the top 10 banks’ membership in or support of a number of global voluntary initiatives that have a focus on businesses (or the finance sector in particular) and climate change. While the low number of observations hinders a thorough statistical analysis, we do find that banks that are not supporters of TCFD or the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative have less statements about climate change in their annual reports. A number of these initiatives are taking initial steps to develop a standard of measures for identifying a bank’s impact on climate change, but these measures do not seem to be operational as of yet. Some of these initiatives, such as the Carbon Disclosure Project and TCFD, also focus on promoting a standard of disclosure in relation to a bank’s strategy and risk management for climate change-related finance, but do not necessarily evaluate if the bank’s strategies for reducing its carbon footprint (through its own operations or its business activities) effectively aligns with Paris Agreement targets (Carbon Disclosure Project, Citationn.d.; Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, Citationn.d.). Finally, certain banks, such as Barclays, JP Morgan, and MUFG, talk in their annual reports of committing to enhanced due diligence and restrictions of lending to controversial sectors, including some key climate-related sectors such as fossil fuels (Creating opportunities to rise: Barclays PLC Annual Report, Citation2018; JP Morgan Chase & Co. Annual Report, Citation2019; MUFG Report 2019 - Integrated Report, Citation2019).Footnote6 Yet, it is unclear whether or how these banks are considering commitments to mitigate climate change, for example, by significantly divesting or reducing their financing to fossil fuel industries. We acknowledge that the various collective initiatives that banks participate in (see SM Figure S.3) reflect a consideration of the forward-looking responsibility of banks in society, but collective initiatives directly targeting the impact of banks’ financing of climate change-related activities still seem to be in early stages of developing harmonized standards (Sveriges Riksbank, Citation2021). Furthermore, the sheer number of initiatives, related both to the financial sector and to companies in general, has led to an ‘alphabet soup’ of disclosures, making it difficult to contextualize and compare these disclosures in a way that the public or financial regulators could hold banks accountable for their progress in mitigating climate change, which was discussed extensively at COP26, for example, at the seminar ‘The Pathway towards a Global Standard for Sustainability Reporting’ at the Swedish Pavilion. We also note that acknowledgment of causal responsibility seems to be primarily in relation to banks’ direct operations instead of their financing. The banks’ statements found in the annual reports about development of their own policies restricting financing of certain fossil fuels could be seen as the strongest actions reflecting a consideration of responsibility of their fossil fuel financing, but these statements were not prevalent in most reports. Even if these sorts of statements were present, they were normally within a bullet list of sustainable policies without much discussion attached to each policy.

Effective policies could help foster a sense of backward-looking responsibility through due diligence. For example, the EU is expected to introduce legislation mandating human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD), and the current draft directive discusses climate change as an aspect of this due diligence (EU Commissioner for Justice Commits to Legislation on Mandatory Due Diligence for Companies, Citation2020; Wolters et al., Citation2020). HREDD notably requires businesses (including banks) to conduct due diligence on potential impacts that they may have on human rights and the environment both directly and indirectly (i.e. via suppliers and other business relationships) (Macchi, Citation2020). This draft directive is an example of legislation that would require businesses to reflect on their responsibility to mitigate climate change not only in their direct operations but also throughout their business.

That being said, we note that there has been an emerging trend of a new commitment that we have seen outside of the annual reports we have reviewed. Many banks have recently committed to reducing the carbon emissions embedded in the activities they finance. For example, since 2020, (1) JP Morgan adopted a financing commitment aligned to the goals of the Paris Agreement, (2) MUFG pledged to be net-zero in their finance portfolio by 2050, and (3) Barclays set a net-zero carbon target for 2050 and planned to align all its financing activities to the timeline of the Paris Agreement (JPMorgan Chase Adopts Paris-Aligned Financing Commitment, Citation2020; Makortoff, Citation2020; Sheldrick, Citation2021). These pledges may reflect a new trend of bank commitments to broadly pledge to reduce the climate change impacts of their financing rather than focus on pledges that promote (their services for) a low-carbon economy. These pledges may also reflect a response to increasing shareholder and investor pressure on banks to show a stronger commitment to mitigating their contribution to climate change through their financing. It will be relevant to see if and how these pledges are elaborated on in upcoming publications of these banks’ annual reports.

Finally, the wording of general statements may reflect the strongest appeals to how banks are reflecting on their role in relation to climate change. Statements in the general category broadly discuss the role of banks in society in relation to their community and the public’s expectations of banks as an important part of society. These statements are also broad commitments to contribute to mitigating climate change or realizing the goals of the Paris Agreement. They can generally be seen in the introductory summaries of the annual report and letters from the Chair or from the Board.

As noted earlier, these general statements are too vague to be commitments on their own but are normally seen as an introduction to a summary of the opportunities or commitments that the bank is pursuing. A number of these general statements reflect a sense of responsibility to mitigate climate change based on the bank’s role in society and capacity to act. However, it is important to point out that the following statement in the Barclays 2019 Annual Report is the only one we reviewed (in any category) that refers explicitly to the causal, indirect impact a bank can have on the environment:

Banks have a direct environmental and social impact through their operational footprint, as well as indirectly in the way that they mobilise capital, advise clients and develop products [emphasis added]. Our aim is to help facilitate the transition to less carbon intensive sources of energy, while supporting economic development and growth in society by helping to ensure the world’s energy needs are met responsibly (Delivering for Our Stakeholders: Barclays PLC Annual Report, Citation2019).

Conclusions

If one should ‘follow the money’ to find the culprits of a crime, what does that say for the significant amounts of money that the financial industry puts into fossil fuels? Our assessment of 10 banks’ annual reports – focusing on banks that are the most active in financing fossil fuels – shows that they are increasingly talking about climate change, but that there is a lack of critical reflection in relation to their impact on climate change through their own financing or lending practices.

We see an increasing trend from 2015 onward in bank annual reports discussing climate change across all four categories of statements. Most of the banks we reviewed have at least general statements recognizing that the financial industry has some sort of role to play in mitigating climate change. In particular, the commitments outlined in these reports, to some limited extent, identify KPIs to aid in understanding how banks impact climate change (at least through their operations) and how banks perform against these KPIs over time.

Effective policies targeting the finance industry need to explicitly consider how to measure and reduce climate impacts not only from the direct operations of a bank (as has been the focus of banks’ commitments in relation to climate change), but also in relation to banks’ financing or client lending activities. Policies could consider a standardization of relevant KPIs and a requirement of environmental due diligence and/or mandatory disclosures. Furthermore, research is needed to help establish policies and guidelines to promote and assess banks’ actions in relation to climate change and how they actually align with the Paris Agreement (Financial Sector Science-Based Targets and Guidance – Pilot Version, Citation2020). Finally, beyond the current voluntary initiatives noted as commitments, regulated mandatory disclosures of banks’ financing of fossil fuels could be required to provide better data and contextualization (for example, relating their data to align with the Paris Agreement instead of comparing to previous years) for public review. Furthermore, these disclosures should establish KPIs specifically in relation to their financing activities.

Reviewing the annual reports of the top 10 banks financing fossil fuels is useful in understanding these banks’ priorities and perceived responsibility in relation to climate change. For further research opportunities, this approach – of creating categories to identify overall trends of statements within these reports – can be used to review annual reports, as well as other publications in relation to sustainability and ESG issues, produced by banks who may be further along in mitigating their impacts related to climate change. Our methodology could be used in combination with NLP to assess these publications and understand what banks are saying in relation to climate change in more detail, and also compare banks that are laggards versus leaders in terms of divesting from fossil fuels. This could lead to a database that can be used to hold banks publicly accountable for their statements in tandem with future research or policy to guide what actions banks need to take to align with the Paris Agreement.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (589.3 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge financial support from the University of Gothenburg via a grant to the UGOT Center for Collective Action Research (CeCAR) and the Mistra Carbon Exit research program (the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research). We thank Sverker C. Jagers and participants at the CeCAR summer conference for valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Supplementary Material for a thorough discussion on the use of annual reports as a basis for our analysis.

2 The word search included: Climate change, Carbon, Divestment (divest-), Fossil fuel(s), Global warming, Paris Agreement, Reduce, Scope 3, and SDG(s) (sustainable development goals).

3 All quotations are available from the authors upon request.

4 BERT stands for Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers; see Bingler et al. (Citation2021) and Devlin et al. (Citation2019) for further reading about the model.

5 See Figure S.4 in SM for Spearman’s pairwise rank correlation coefficients.

6 These restrictions are further reviewed in the Banking on Climate Change report, along with restrictions that other banks have taken (Kirch et al., Citation2020).

References

- Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth (COM/2018/097). (2018). European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0097.

- Bingler, J. A., Mathias, K., & Leippold, M. (2021). Cheap Talk and Cherry-Picking: What ClimateBERT has to say on Corporate Climate Risk Disclosures. SSRN. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3796152.

- Carbon Disclosure Project. (n.d.). Companies. CDP - Disclosure Insight Action. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.cdp.net/en/companies.

- Climate-related reporting requirements. (2021, June 24). Financial Conduct Authority. https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/climate-change-sustainable-finance/reporting-requirements.

- Congressional Research Service. (2019, September 10). Climate-Related Risk Disclosure Under U.S. Securities Laws. In Focus. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11307.pdf.

- Creating opportunities to rise: Barclays PLC Annual Report. (2018). Barclays PLC. https://home.barclays/investor-relations/reports-and-events/annual-reports/#archive

- Delivering for our stakeholders: Barclays PLC Annual Report. (2019). Barclays PLC. https://home.barclays/investor-relations/reports-and-events/annual-reports/#archive.

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1810.04805. https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805v2.

- Discussion Paper: Working Group enabling remediation. (2019). Duth Banking Sector Agreement.

- Erlichman, S., & Langlois, S. (2021, February 18). ESG Disclosure in Canada—Legal Requirements, Voluntary Disclosure and Potential Liability. Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP. https://www.fasken.com/en/knowledge/2021/02/esg-disclosure-in-canada-legal-requirements-voluntary-disclosure-and-potential-liability.

- EU Commissioner for Justice commits to legislation on mandatory due diligence for companies. (2020, April 30). Business and Human Rights Resource Centre. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/eu-commissioner-for-justice-commits-to-legislation-on-mandatory-due-diligence-for-companies/.

- Financial Sector Science-based Targets and Guidance—Pilot Version. (2020). Science Based Targets initiative. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/legacy/2020/10/Financial-Sector-Science-Based-Targets-Guidance-Pilot-Version.pdf.

- Fossil Banks No Thanks. (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.fossilbanks.org.

- Furrer, B., Hamprecht, J., & Hoffmann, V. H. (2011). Much Ado about nothing? How banks respond to climate change. Business & Society, 51(1), 62–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650311427428

- Graafland, J. J., & van de Ven, B. W. (2011). The credit crisis and the moral responsibility of professionals in finance. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(4), 605–619. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0883-0

- Hell, C., McKenzie, M., Auer, C., & Gute, A. (2020). Towards net zero: How the world’s largest companies report on climate risk and net zero transition. KPMG. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/11/towards-net-zero.pdf.

- Herren Lee, A. (2021, March 15). Public input welcomed on climate change disclosures. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. https://www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/lee-climate-change-disclosures.

- Herzog, L. (2019). Professional ethics in Banking and the logic of “integrated situations”: aligning responsibilities, recognition, and incentives. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(2), 531–543. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3562-y

- Japan’s Corporate Governance Code: Seeking Sustainable Corporate Growth and Increased Corporate Value over the Mid- to Long-Term. (2021). Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc. https://www.jpx.co.jp/english/rules-participants/public-comment/detail/d01/b5b4pj00000436i2-att/b5b4pj0000046lfk.pdf.

- JPMorgan Chase Adopts Paris-Aligned Financing Commitment. (2020, October 6). [JPMorgan Chase & Co.]. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/news-stories/jpmorgan-chase-adopts-paris-aligned-financing-commitment.

- JP Morgan Chase & Co. Annual Report. (2019). JP Morgan Chase & Company. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/ir/annual-report

- Kinley, D. (2018). Necessary evil: How to Fix finance by saving Human rights. Oxford University Press.

- Kirch, A., Opena Disterhoft, J., Marr, G., McCully, P., Gursoz, A., Aitken, G., Hamlett, C., Saldamando, A., Louvel, Y., Pinson, L., Cushing, B., Brown, G., & Stockman, L. (2020). Banking on Climate Change: Fossil Fuel Finance Report. Rainforest Action Network, Banktrack, Indigenous Environmental Network, Oilchange International, Reclaim Finance, and Sierra Club. https://www.ran.org/bankingonclimatechange2020/.

- Krueger, P., Sautner, Z., & Starks, L. T. (2020). The importance of climate risks for institutional investors. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(3), 1067–1111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz137

- Macchi, C. (2020). The climate change dimension of business and human rights: The gradual consolidation of a concept of ‘climate Due diligence’. Business and Human Rights Journal, 6, 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/bhj.2020.25

- Makortoff, K. (2020, March 30). Barclays sets net zero carbon target for 2050 after investor pressure. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/mar/30/barclays-sets-net-zero-carbon-target-for-2050-after-investor-pressure-climate.

- Measuring and reporting environmental impacts: Guidance for businesses. (2019, January 31). Gov.Uk. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/measuring-and-reporting-environmental-impacts-guidance-for-businesses.

- Miller, D. (2001). Distributing responsibilities. Journal of Political Philosophy, 9(4), 453–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00136

- Mosnier, F. (2021, April 8). Japanese Corporate Governance Code Revision: A Missed Opportunity for Biodiversity. Planet Tracker Blog. https://planet-tracker.org/japanese-corporate-governance-missed-opportunity-for-biodiversity/.

- MUFG Report 2019 - Integrated Report. (2019). Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group. https://www.mufg.jp/english/ir/report/annual_report/backnumber/index.html

- Nelson, M., Bell, M., Ivanova, V., & Schmeitzky, C. (2021). Global Climate Risk Disclosure barometer. Ernst & Young. https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/assurance/ey-if-the-climate-disclosures-are-improving-why-isnt-decarbonization-accerlerating.pdf.

- Paisley, J., & Nelson, M. (2020). Second Annual Global Survey of Climate Risk Management at Financial Firms: Mapping out the Continuing Journey. Global Association of Risk Professionals Risk Institute. https://climate.garp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GRI_ClimateSurvey_051320.pdf.

- Ruggie, J. (2017). Comments on Thun Group of Banks Discussion Paper on the Implications of UN Guiding Principles 13 & 17 In a Corporate and Investment Banking Context. Harvard Kennedy School.

- Sandberg, J. (2011). What are your investments doing Right Now? In W. Vandekerckhove, J. Leys, K. Alm, B. Scholtens, S. Signori & H. Schäfer (Eds.), Responsible investment in times of turmoil (pp. 165–177). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9319-6_10.

- Sandbu, M. E. (2012). Stakeholder duties: On the moral responsibility of corporate investors. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1382-7

- Sheldrick, A. (2021, May 17). Mitsubishi UFJ pledges net zero emissions in finance portfolio by 2050. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-mufg-idCAKCN2CY0OM.

- Stop the Money Pipeline. (n.d.). About the Movement. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://stopthemoneypipeline.com/about-2/.

- Sustainable finance. (n.d.). European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance_en.

- Sveriges Riksbank. (2021). Riksbankens klimatrapport -Klimatrisker i policyarbetet. https://www.riksbank.se/globalassets/media/rapporter/klimatrapport/2021/riksbankens-klimatrapport-december-2021.pdf.

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. (n.d.). Retrieved January 3, 2021, from https://www.fsb-tcfd.org.

- Toft, K. H. (2020). Climate change as a business and human rights issue: A proposal for a moral typology. Business and Human Rights Journal, 5(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/bhj.2019.22

- UN Human Rights Council. (2011). Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework (HR/PUB/11/04). United Nations Human Rights Council. https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf.

- Våra fossila pensionspengar. (2020, December 14). In Kaliber, Sveriges Radio. P1 Sverige Radio. https://sverigesradio.se/avsnitt/1616501.

- Wolters, L., Glucksmann, R., & Lange, B. (2020). Draft Report with recommendations to the Commission on corporate due diligence and corporate accountability (2020/2129(INL)). European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/JURI-PR-657191_EN.pdf.