ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to investigate how political and technical factors influence climate finance coordination in different country contexts. Emerging scholarly and policy literature calls for the improved coordination of climate finance to enhance the effectiveness of multiple sources of funding for adaptation and mitigation purposes, with country ownership over coordination emerging as a potential approach. However, few studies have examined how climate finance coordination unfolds at the national level in developing countries. This paper presents findings from a comparative assessment of climate finance coordination practices in Kenya and Zambia, drawing on semi-structured interviews, policy documents, and relevant literature. Specifically, the paper investigates how political and technical forces shape climate finance coordination in contexts with varying country ownership over the coordination process. We find that political factors relating to power dynamics, framings of climate finance, and vested interests play a strong role in shaping how actors interact, hampering coordination efforts within the climate finance landscape in both countries. This adds a new dimension to calls for greater country ownership, which we suggest needs to be paired with a critical examination of political struggles and contestation.

Key policy insights

Underlying political factors relating to conflicting vested interests, different framings and discourses, political will, and power dynamics play a substantive and overarching role in shaping climate finance coordination in Kenya and Zambia.

These political factors limit the extent to which greater country ownership translates to better or more effective coordination of climate finance; as such, ownership needs to be examined in the context of political struggles and contestation.

Instead of just aiming to improve coordination through more formalized coordination structures, capacity building and reduced fragmentation, countries also need to be more transparent and acknowledge the deep-seated interests within the climate finance landscape, to make visible the winners and losers of various coordination mechanisms and structures.

1. Introduction

Climate finance has been an integral component of the international response to climate change, with an emphasis on assisting developing countries (classified as ‘non-Annex I countries’) with mitigation and adaptation efforts (Ha et al., Citation2016). At COP15 in Copenhagen, developed countries committed to mobilize US$100 billion a year in climate finance by 2020. This was reaffirmed at COP21 in Paris, where developed countries further committed to continued mobilization of finance at the same rate until and beyond 2025 (UNFCCC, Citation2015).

The climate finance architecture now consists of a large and growing number of climate funds, including, for example: the Climate Investment Funds (CIFs), the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Adaptation Fund (AF), and the Global Environment Facility (GEF), among others. The GCF, AF, and GEF all operate under the auspices of the UNFCCC. Each of these funds has their own separate requirements for national accreditation and project approval, and mechanisms for financial dissemination. In contrast, the CIFs operate as an entirely separate entity, implemented through the multilateral development banks (Amerasinghe et al., Citation2017). Beyond multilateral finance, countries also receive climate finance bilaterally and through the private sector, in addition to receiving development finance from multiple sources. This creates a highly fragmented and complex system for potential recipients of climate finance at the national level (Pickering et al., Citation2017).

Emerging literature therefore calls for national-level coordination of climate finance to increase efficiency in the use of funds, reduce duplication, and ensure that its mobilization contributes to achieving national climate and development objectives in low-income countries (see e.g. Pickering et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2011). For many low-income countries, limited coordination of climate finance contributes to the already significant difficulties of gaining access to funding (Amerasinghe et al., Citation2017), and leads to the inefficient use of funds, low transparency and accountability (Pickering et al., Citation2017), and potential barriers to achieving or reinforcing other sustainable development objectives (Halonen et al., Citation2017). In contrast, coordinated funding is assumed to produce greater benefits, such as when donors respect nationally-determined priorities, use country systems for implementation, and coordinate activities with other funders (Abdel-Malek, Citation2015).

Much of the work on climate finance coordination to date, however, has taken a theoretical and/or global perspective on these issues (Lundsgaarde et al., Citation2018a; Lundsgaarde et al., Citation2018b; Nakhooda & Jha, Citation2014; Pickering et al., Citation2017). Few studies have empirically explored the nature, practices, and challenges to climate finance coordination as it develops in national contexts. While there is a growing body of ‘grey’ policy literature on climate finance coordination, this tends to emphasize institutional factors, such as communication between actors (Amerasinghe et al., Citation2017; Nakhooda & Jha, Citation2014), and does not typically explore factors such as vested interests or power dynamics that may also be influencing coordination.

This paper aims to fill these gaps by exploring climate finance coordination in two country case studies: Kenya and Zambia. The countries share similar conditions and challenges in relation to climate finance: they both receive substantial amounts of finance from a combination of bilateral and multilateral sources, with the presence of a strong international development community, alongside private sector actors, civil society organizations (CSOs), research and policy think tanks and consultancies. This creates a complex climate finance architecture in both countries on top of a long-term history of receiving development aid, providing similar contexts in which to compare different coordination approaches.

Drawing on both the climate finance coordination and development aid literature, we develop a framework of technical and political factors that could influence coordination at the national level. Specifically, we ask: how do political and technical factors influence climate finance coordination in different country contexts?

We aim to explore contextual differences between Kenya and Zambia by bringing in the dimension of country ownership. Emerging from the aid effectiveness literature, and institutionalized in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2005 (OECD, Citation2005), country ownership is conventionally defined as a means to ensure that development projects are aligned with national policies, strategies, and needs, with national systems utilized to increase recipients’ accountability in how resources are used (Zamarioli et al., Citation2020). Country ownership thus involves a range of features in a development assistance context, including ownership over policymaking, implementation, or finance utilization. Here, we focus on one particular aspect of country ownership, namely the extent to which organizational coordination mechanisms and processes are embedded within national policy and institutional structures.

Exploring this aspect of country ownership enables us to go beyond general calls for more or better coordination to also explore what approaches to coordination may work better than others. This includes looking at whether well-established national coordination systems are necessary for coordination to take place or for better coordination outcomes. Given that both the GCF and the AF have taken recent decisions to emphasize country ownership (Adaptation Fund, Citation2021; GCF, Citation2017), we can expect that embeddedness of coordination mechanisms in national structures could be a potential outcome. This makes it particularly timely and relevant to assess what this means for coordination overall.

After describing our methodology, we develop an analytical framework of technical and political factors influencing coordination. This framework is then applied to our empirical data to pull out key findings and differences between the two countries. Finally, we reflect on our research question and conclude with some theoretical contributions and policy recommendations.

2. Methodology

This comparative case study was carried out as part of a larger, multi-year research project examining coordination within and between international climate funds. The conceptual and theoretical work carried out in the first phase of the project in 2018 (see Lundsgaarde et al., Citation2018a) was used to guide the development of the topics of inquiry and research methodology in the two countries.

After concluding this first phase, a team of researchers was established for each country to lead the field work for in-country data collection. Prior to fieldwork, each team used a common template to conduct an exhaustive review of academic literature and policy documents on flows of publicly-sourced climate finance to identify how climate finance is coordinated, and by whom. These documents were used to map the landscape of institutions and actors involved in coordination of international climate finance. Documents were sourced from the governments of the two countries, international institutions (including the World Bank and United Nations), bilateral aid agencies, national and international think tanks, and civil society organizations, and covered the time period of 2000–2019. We searched for literature primarily using a Google internet search as well as Web of Science, and continued until each team reached a point of saturation and had created as complete a climate finance coordination map as possible.

For the purposes of this paper, we then conducted seventeen in-person, semi-structured interviews in Kenya and seventeen in Zambia, including a combination of government actors, bilateral and multilateral donors, civil society actors and the private sector. Most of the institutions that provided interviewees were identified in our initial climate finance landscape mapping, and the specific individuals that we spoke with were selected by their respective institutions. The full list of institutions interviewed is available in the Supplementary Material. The interviews lasted between one and two hours each; we documented them through note-taking rather than recording.

The interview questions asked in each country were divided between descriptive and analytical questions. Descriptive questions included identifying who is involved in coordinating climate finance, how coordination occurs and what mechanisms and structures for coordination are in place. Analytical questions included identifying factors that were enabling or hindering coordination. The full interview protocol is available in the Supplementary Material.

We then coded the documents and interviews according to these two areas of inquiry (descriptive and analytical) and compared the data across the two countries to draw our conclusions about the factors influencing coordination of climate finance.

3. Climate finance coordination: an analytical framework

3.1. Framing of key concepts

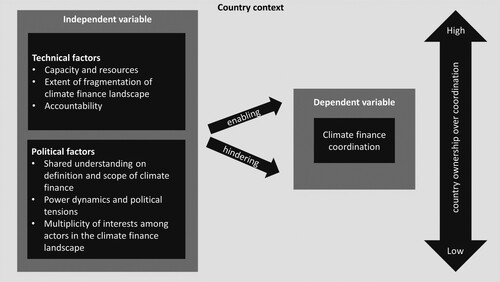

below lays out our analytical framework. Here, climate finance coordination is interpreted as the dependent variable. We define coordination as a practice or a process actors engage with to facilitate the achievement of goals shared with other actors (Lundsgaarde et al., Citation2018). Different approaches to coordination can exist at the national level, with differences between countries in the extent to which they have ownership of the climate finance coordination process. Here, we focus on one particular aspect of ownership, i.e. the extent to which the organizational mechanisms for coordination are embedded within domestic structures. This will vary along a spectrum from coordination mechanisms that are completely embedded within national structures, to mechanisms that are entirely externally driven by donors and other external actors.

Secondly, technical and political factors are the independent variables in our framework. We stipulate that these factors can play a role in enabling or hampering coordination within different national contexts (i.e. low or high ownership over coordination). We arrive at these factors through a joint review of the aid effectiveness and climate finance coordination literatures. Linking these two literatures together allows us to also investigate the role of these factors in contexts with different levels of country ownership.

While the framework is arguably broadly applicable, we apply and discuss it here in the context of climate finance specifically. The specific nature of different fields of financing will vary, and this must be captured in the empirical investigation. Hence while development finance and global climate finance are closely connected in some respects, they also have different histories and architectures that influence positions and dynamics of the field (Peterson & Skovgaard, Citation2019; Pickering et al., Citation2015).

The following subsections therefore review the aid effectiveness and climate finance coordination literatures to further flesh out the role that technical and political factors can play.

3.2. Technical factors

While the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness emphasizes the need for country ownership, the aid effectiveness literature finds that there are technical dimensions that can shape the way it plays out on the ground. Here, we identify these factors from the aid effectiveness literature, and then review the coordination literature to stipulate how these factors can also influence coordination.

For example, Goldberg and Bryant (Citation2012) argue that efforts to increase country ownership need to be paired with national capacity building to build up in-country technical knowledge and reduce reliance on external expertise, enabling countries to design and lead development programmes based on their own priorities. Capacity and resources of national governments could therefore influence coordination (Leiderer, Citation2015). Sufficient resources and personnel are required to develop and operationalize effective coordination mechanisms and sustain longer-term participation (Linn, Citation2009). For example, relevant finance and environment ministries would need time and resources to operationalize coordination structures and regularly engage with donors, CSOs, and other government bodies to coordinate, particularly as coordination mechanisms are considered process-intensive and particularly burdening for institutions with weak capacity.

The aid effectiveness literature also stipulates that fragmentation and competition amongst both donors and national government bodies can undermine country ownership (Hasselskog, Citation2020), unless paired with critical efforts to ensure that donor efforts are aligned with recipient governments’ development strategies and administrative systems (Whitfield, Citation2009). The extent of fragmentation of the climate finance landscape at the national level in terms of multiple funding sources with different governance frameworks, application procedures, and timelines can therefore also influence coordination (Lundsgaarde et al., Citation2018a). Institutions both governing and disseminating climate finance are characterized by different memberships, norms, principles, and decision-making procedures, creating further fragementation and coordination challenges (Biermann et al., Citation2009; Keohane & Victor, Citation2016; van Asselt & Zelli, Citation2014). For example, multilateral funds often have different accredited entities at the national level, as well as separate procedures for project approval, raising further coordination challenges. The proliferation of bilateral and multilateral climate funds, and related procedures for project design and implementation, can create overlaps in work areas and inconsistencies in procedures for accessing and managing funding, leading to inefficiencies and hindering coordination overall (Amerasinghe et al., Citation2017). Coordination of climate finance activities is therefore assumed to lead to better oversight and more efficient utilization of resources (UNFCCC, Citation2014), through ensuring harmonization and transparency and reducing duplication (Delputte & Orbie, Citation2014). Similarly, the extent of harmonized rules and standards between funding sources can give a strong underlying basis for more effective coordination (Amerasinghe et al., Citation2017). As such, coordination would entail knowledge and information sharing through joint analysis and planning for collective implementation across actors and governance levels (Delputte & Orbie, Citation2014). This exchange can be conducted through both formal and informal processes (Gkeredakis, Citation2014; Okhuysen & Bechky, Citation2009).

Finally, the aid effectiveness literature also highlights the critical need to pair country ownership efforts with accountability, with greater opportunity for local participation to enable civil society actors and marginalized groups to also influence both national strategies and how funding is utilized (Hasselskog, Citation2020). In the context of coordination, mutual accountability is key in influencing credibility, trust, and the relationship between donors and recipients, which can in turn affect the extent and willingness of coordination between, for example, donors and government actors (Pickering et al., Citation2017). Accountability can therefore shape coordination through assuring that responsibilities of different actors are visible in the coordination landscape and that there is transparency in how donor resources are utilized (Okhuysen & Bechky, Citation2009). High levels of accountability to civil society actors through their active involvement in how climate finance is utilized could also lead to greater coordination, such as through building informal relationships.

3.3. Political factors

The aid effectiveness literature also highlights the political dimensions of country ownership. For instance, Hayman (Citation2009) find that different perspectives and understandings between key actors and donors play a critical role in influencing the level of country ownership, which can translate to contestation between actors on the ground. As such, the extent of shared understandings on definition and scope of climate finance can itself shape coordination. At the Copenhagen climate negotiations in 2009, countries committed to providing US$100 billion of climate finance per year, but this lacked any precision regarding the proportions of finance from multilateral, bilateral, or private sources, and the top-down nature of the pledge also conflicted with the voluntary, bottom-up nature of the subsequent Paris Agreement, leading to considerable discretion to developed countries in the implementation of their climate finance commitments (Roberts & Weikmans, Citation2017). This fragmented approach can lead to a lack of clarity at the national level on what forms of aid can actually be considered ‘climate finance’ and accounted for as such, creating challenges around the scope and boundaries of coordination mechanisms.

Secondly, as country ownership implies a transfer of power from donors to recipients, power dynamics and tensions between donors and recipients also play a key role in influencing country ownership (Lancaster, Citation1999). McGee and Heredia (Citation2012) argue that the Paris Declaration ‘renders invisible’ or neglects the power and politics at the heart of aid relationships, instead defining effectiveness in a more technocratic manner. Power dynamics and political tensions within the national climate finance landscape therefore is another factor that shapes coordination, with the agendas and preferences of more powerful actors shaping the extent to which coordination is prioritized in the country and leads to greater country ownership (Benvenisti & Downs, Citation2007). The literature highlights how the preferences and objectives pursued by powerful actors constitute important explanations for coordination (Bigsten, Citation2006; Bourguignon & Platteau, Citation2015; Keohane & Victor, Citation2016), and can dictate not only whether formalized climate finance coordination mechanisms are established, but also the extent to which they are utilized and maintained. For example, ministries with larger budgets wield more power in bargaining processes and can influence coordination mechanisms to better reflect their preferences. Similarly, more powerful civil society actors with closer working relationships to key government bodies have greater scope to ensure that their agendas are reflected in government decisions.

Finally, the vested interests of donors is also identified as an influential factor on the level of country ownership, particularly as the new finance architecture can put competing demands on national finance architectures and lead to increased contestation on the ground (Sjöstedt, Citation2013). As such, coordination challenges can emerge due to a multiplicity of interests among actors in the climate finance landscape. For instance, national governments may have an interest in maintaining diversity among funders to maximize the financial flows to the country, and therefore may display a reluctance in advancing coordination efforts (Olivié & Pérez, Citation2016). On the finance provider side, conflicts of interest can also arise between different ministries responsible for climate finance and Official Development Assistance (ODA). For example, environment ministries are experienced with mitigation efforts and tend to strongly emphasize climate mitigation efforts. Meanwhile, development ministries tend to prioritize adaptation activities and sustainable development. Conflicting agendas can influence the balance of priorities in climate finance portfolios (Pickering et al., Citation2015). A key source of tension and conflict of interests relates to the line ministries, which stand to lose control of funding due to consolidated approaches, and the central aid coordinating entities, which may have greater leeway to influence funding priorities in a more strongly coordinated aid management context (Winckler & Therkildsen, Citation2007).

The next section of the paper expands on each of these factors, assessing how our data from Kenya and Zambia corresponds to the literature.

4. Analysis

Overall, our results indicate that coordination has evolved differently in Kenya and Zambia. Historically, both countries have had an approach to climate finance coordination that has been strongly influenced by the activities of multilateral and bilateral donors. More recently, however, Kenya’s approach to coordination has become more embedded and institutionalized within national structures, with the recently established Climate Change Act (Government of Kenya, Citation2016) putting in place a number of coordination mechanisms. In Zambia, on the other hand, current coordination arrangements continue to be influenced by past donor influence and are more contested and in flux.

As such, Kenya has shifted toward a coordination approach with greater country ownership, whereas Zambia exhibits stronger donor influence and more pragmatic arrangements. In the following subsections, we demonstrate these different levels of country ownership over coordination by looking at how climate finance is being coordinated and who is coordinating it. This enables us to investigate both facets of country ownership, i.e. alignment with national policies, strategies, and priorities (how), and leadership of recipient countries (who). Drawing on our analytical framework, we then explore how technical and political factors influence coordination outcomes in these two contexts of high and low country ownership for Kenya and Zambia, respectively.

4.1. How is climate finance coordinated?

4.1.1. Kenya

In Kenya, a strong national policy framework for climate finance coordination is observed, which at first glance is more aligned with our interpretation of high country ownership. For example, Kenya’s Climate Change Act (Government of Kenya, Citation2016) mandates the establishment of Climate Change Units in all counties and ministries to mainstream climate change activities within planning and budgeting. The Act also mandates establishing a Climate Fund at both the national and county level to coordinate climate finance flows, with a Climate Change Council chaired by the President, and sitting under the National Treasury, established to manage the fund. The Fund would involve government departments and ministries setting aside a proportion of their budget for climate change activities. Furthermore, the Climate Change Act identifies counties as an important mechanism for devolving funds from the national to local levels. Therefore, a number of counties (five as of 2019) have piloted County Climate Change Funds (CCCFs), where counties are expected to set aside a proportion of their budget for climate change activities, with donors also co-investing in the funds. Lastly, the Climate Finance Policy (Government of Kenya, Citation2017) in Kenya mandates the establishment of a tracking system by the Treasury to monitor, report, and verify all climate finance flows within the country.

Kenya has also established donor and sector coordination working groups to facilitate coordination between the government and donors, as well as NGOs. The working groups are often chaired by ministries and departments, such as the Climate Change Directorate (CCD). Donors are invited to a meeting where they state how they support the government’s areas of need, ensuring alignment with the country’s overall strategy and priority areas. Interviewed donors, such as the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), emphasized that such structures are needed for information sharing to avoid the duplication of efforts and for donors to ‘understand what the government prioritises’ and ensure harmonization and alignment with government priorities. In addition to these formal structures, interviewees also highlighted that informal interactions and personal relations are important to help non-state actors cut through bureaucratic processes and reach governmental actors more easily. For example, one Kenyan NGO highlighted that developing a personal relationship with government actors in the National Treasury enabled them to contact government officials easily via phone and follow up regularly to ensure that their agendas were being prioritized.

Despite the presence of these formal and established coordination structures in Kenya, challenges exist that hinder this higher country ownership approach to climate finance coordination. For example, the National Climate Fund mandated by the Climate Change Act has still not been established, mainly because the Climate Change Council chaired by the President has not yet met to sign off on and administer the fund. While one (technical) explanatory factor is the lack of capacity and resources, several interviewees noted a lack of interest in climate change at the highest levels of the Kenyan government. Consequently, climate finance coordination is given lower political priority in relation to other development issues.

Secondly, the climate finance tracking system managed by the government does not include coverage of funding coming through bilateral donors, CSOs, or the private sector, raising transparency challenges. Again, governmental actors such as the National Treasury provide primarily technical reasons for this, such as a lack of capacity and personnel to further develop the tracking system, as well as a high level of fragmentation in the climate finance landscape making tracking difficult. However, a more political lens points to the politically charged nature of such data. While aid allocations are reported to, e.g. OECD databases, donor reporting has a history of limited transparency, especially at more granular levels (Ameli et al., Citation2020; Easterly & Williamson, Citation2011; Weikmans & Roberts, Citation2019). In particular, separating out new and additional climate finance from existing development aid is a politically sensitive exercise for donors, who are often reluctant on this aspect (Roberts et al., Citation2021; Weikmans & Roberts, Citation2019). This in turn links to the broader global disagreements between donor countries and developing countries over climate financing, which have contributed to the lack of agreement on a clear definition for what climate finance actually constitutes, how it is different from development assistance, and whether they should be coordinated separately or together (Steckel et al., Citation2017). In Kenya, the government’s interpretation of climate finance largely excludes funding from bilateral donors and NGOs, thereby leading to duplication and reduced efficiency through limited coordination between bilateral and multilateral funding flows. As a result, much of the discourse around climate finance in Kenya overemphasizes multilateral over bilateral finance sources, despite the overwhelmingly larger proportion of bilateral funding (Dzebo et al., Citation2020).

Thirdly, Kenya has recently shifted to devolved governance, which gives greater autonomy to the county governments, with the Council of Governors playing an important role as the link between the counties and the national government. However, despite the establishment of the CCCFs, a representative of the Nairobi county government stated that the dissemination of information on climate finance from national to county governments is particularly lacking, with counties often hearing about new developments from newspapers rather than directly through the Council of Governors, the intermediary body responsible for this coordination. The Council of Governors has received limited financial support from the national government, limiting its effectiveness and making it overly reliant on donors and NGOs for capacity and resources.

Finally, despite the presence of donor and government coordination working groups, bilateral donors such as the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) and DANIDA highlighted that the climate finance working group has not met in several years. From a technical perspective, this could again be due to a lack of time, capacity, and resources. However, a political perspective reveals that the key barrier here is multiple interests within the climate finance landscape, particularly tensions between governmental actors, bilateral donors, and CSOs. For instance, the Climate Change Directorate (CCD) states that bilateral donors ‘already come in with a fixed mindset of what they are going to do’, having interests and agendas that do not meet government objectives or expected outcomes. This is leading to the limited utilization of existing coordination mechanisms in the country, such as donor and government coordination working groups.

Overall, it is evident that despite an approach to coordination in Kenya more inclined towards country ownership, with a strong policy framework and legislation for coordination and various coordination structures being established, a number of both technical and political factors are creating barriers for effective coordination outcomes. This is leading to a shift toward more donor influence over coordination, which is discussed in section 4.2.

4.1.2. Zambia

Donors have historically played substantial roles in determining Zambia’s government policies (Abrahamsen, Citation2000; Rakner, Citation2012), but have also seen efforts by national governments to strategically engage and ‘re-work’ these (Fraser & Whitfield, Citation2009), which could indicate a potential shift towards greater country ownership over coordination in the longer term. A similar dynamic is evident in current climate finance coordination arrangements, which reflect the outcome of ongoing political organizational struggles between donors and government agencies over more than a decade. In 2009, climate change came into its own as a separate and distinct policy issue with the creation of the Climate Change Facilitation Unit (CCFU), supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and housed in the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources. However, in 2012, the Interim Climate Change Secretariat (ICCS) was established, tasked with climate finance coordination at the national level. Although formally anchored in the Ministry of Planning and Finance, the ICCS was a separate entity under its own roof, and effectively worked as a parallel mechanism outside the Ministry, promoted and funded through the World Bank-administered CIFs. An underlying rationale for establishing a separate coordination unit was donor concerns that a coordination mechanism housed inside government structures would prove cumbersome, obscure transparency in the handling of funds, and reduce donor control over climate funding.

As a result, two competing national climate finance coordinating mechanisms were effectively in operation at the same time: the CCFU, supported by the UNDP, sought to develop a coordination mechanism that aligned with the GCF and other UN climate funds; and the semi-autonomous ICCCS supported by the World Bank and the CIFs. Initially, the latter dominated due to its strong CIF support and links to the powerful Ministry of Finance and Planning. However, over time it has been unable to assume full authority as government agencies and other donors have by-passed or actively undermined it in preference for the UNDP supported mechanism or uncoordinated bilateral agreements (Funder & Dupuy, Citation2022). Eventually, the government took the opportunity of a broader ministerial re-shuffle to disband the World Bank supported coordination facility as a separate semi-autonomous entity, and instead embedded its functions in the Ministry of National Developing Planning. As such, the CIF-funded mechanism continues to operate, still retaining features influenced by its origin as a donor-controlled mechanism, but now embedded in government structures.

Meanwhile, the government has established a broader cross-sectoral coordination arrangement for climate funding under the Council of Ministers, with a high-level government steering committee and technical subcommittees that in principle review and approve all incoming climate funding proposals. This includes a provision coordinating GCF proposals, which have been incorporated in the cross-sectoral mechanism. Alongside this, donors have coordinated knowledge and information among themselves through various donor-specific committees, including one in which technical experts meet within topic-specific development clusters, and the other in which heads of missions meet. Government agencies have formally participated in these, but have increasingly sought to remove the focus from these donor-dominated fora to the government’s own mechanisms. Indeed, in 2018, the government requested donors to disband their coordination fora and asked them to engage with government mechanisms. Donors have responded by meeting informally alongside the formal government mechanisms, both among themselves and with government agencies.

The mechanisms for climate finance coordination in Zambia have thus been characterized by a strong donor influence as opposed to country ownership, but also by government efforts to challenge this and internalize climate finance in government mechanisms to a greater extent. The result is a national climate finance coordination mechanism which remains fragmented, contested, and in flux.

Firstly, the existence of competing climate finance coordination mechanisms means that both government agencies and donors are able to either choose the most favourable one for their preferences by ‘forum shopping’, or to disregard coordination mechanisms altogether without major sanctions. For example, despite the establishment of a cross-sectoral government mechanism for coordinating climate finance, bilateral funding agreements continue to be developed between some bilateral donors and government agencies without passing through national coordination mechanisms.

Secondly, broader global struggles between CIF and GCF funds (Skovgaard et al., CitationForthcoming) continue to be reflected in the domestic climate finance coordination mechanisms in Zambia. The World Bank and UNDP thus continue to promote and argue for different coordination mechanisms and conduct their own planning and project development accordingly. One result of this is the development of concurrent CIF and GCF proposals for support to subnational climate change adaptation led by the two organizations, covering virtually identical subject matters in overlapping or neighbouring districts, yet with little or very limited coordination between them.

Thirdly, the legitimacy of the abovementioned coordination mechanisms among donors has been further undermined by deeper tensions between bilateral donors and government. Some bilateral development agencies have in recent years become increasingly wary of dealing directly with government ministries and agencies, fuelled by concerns over the accountability and transparency of the political leadership, as well as occasional outbursts of anti-foreign aid discourses among politicians. Instead, they provide direct support to, for example, the private sector or CSOs. This is a further political factor contributing to fragmentation in the government’s coordination and planning of climate finance.

Fourthly, the competing arrangements have dogged efforts to collaborate on fleshing out and solidifying coordination measures. For example, during our interviews, most parties lamented that there is no practically useful database providing overviews of current and previously funded climate finance projects at either the national or sub-national level. Such data is important for avoiding duplication and enhancing coordination among key actors and institutions. While the lack of such a database is perhaps not unusual, it is a particular problem in countries where a multitude of donors support a range of individual projects with separate management and financing structures, rather than direct budget support to government systems, according to our interviewees.

Similarly to Kenya, then, interest-driven political factors – and associated technical ones such as fragmentation – limit effective climate finance coordination in Zambia. Despite differences in levels of country ownership, the effectiveness of coordination mechanisms in both countries is limited through political factors relating to vested interests and power dynamics that further fragment the climate finance landscape. This relates closely to the key issue of who has the mandate to lead and coordinate climate finance, as discussed in the following section.

4.2. Who is coordinating climate finance?

4.2.1. Kenya

In line with Kenya’s strive for ownership of coordination, the National Treasury and Planning is the key body mandated with governing climate finance in Kenya, which is both the NDA for the GCF and includes a specialized Climate Finance Unit for the purpose of coordinating the multilateral climate funds (GCF and the CIFs). Other important bodies include the CCD, which coordinates all climate change activities, and the National Environmental Management Agency (NEMA), which is the NDA for the Adaptation Fund and is also an accredited entity to the GCF, which means that it can implement GCF projects. The Treasury and CCD are both member of the Climate Change Council, chaired by the President, and once it becomes operational, will be responsible for making all climate finance decisions.

Despite this strive towards more country ownership and an increased mandate of governmental bodies, donors and CSOs continue to play an important role in filling gaps due to the government bodies’ capacity constraints. For example, the CCD gets a majority of its financial support from donors, CSOs, and the private sector. A coalition of CSOs also lobbied for the creation of the Climate Change Act in Kenya, a critical piece of legislation mandating coordination mechanisms, and our interviews revealed that several CSOs have a close working relationship with government bodies and play a key role in influencing agendas. Here, it is evident that technical factors relating to capacity constraints lead to a shift in coordination responsibilities to donors and CSOs. However, our interviews also revealed that the key reasons for these shifts are primarily political. For example, a representative from the CCD highlighted that a key reason for the lack of budget allocation by the government is the lack of priority by the Executive Office of the President placed on tackling climate change.

Secondly, while Kenya has a long history of bilateral development assistance, with well-established systems in place for the dissemination of these funds, multilateral climate funds are a recent introduction into the financial system and have their own coordination systems and processes in place. The GCF has its own structured way of coordination, with the Treasury acting as the NDA through which funds can be accessed. When it comes to the GEF and the AF, the NDA is a different government body, which itself creates an institutional gap. A lack of harmonized rules and standards contributes to the fragmentation of the climate finance landscape (Lundsgaarde & Keijzer, Citation2019) – with different rules and procedures for applying to various multilateral funds – leading to discrepancies between who has the mandate to coordinate and who is actually coordinating.

This fragmentation is further accentuated and driven by the presence of multiple conflicting interests. The Kenyan national government over-emphasizes multilateral funding, perhaps due to these climate funds entering the landscape with promises of large amounts of climate finance (Lundsgaarde et al., Citation2018). However, this funding has not yet materialized and the majority of climate finance in the country still comes from bilateral donors (Dzebo et al., Citation2020). Despite this, coordination with bilateral donors and civil society organizations is often overlooked, highlighting a discrepancy between funding sources and national priorities. Therefore, bilateral donors often must bypass formal coordination mechanisms and coordinate amongst themselves using more informal means.

Finally, several CSO representatives highlighted that greater country-ownership requires stronger accountability at the government level by reducing corruption and increasing ownership by communities and groups as drivers of coordination. The devolution process was identified as a potential driver for increasing accountability at the grassroots level and promoting learning across counties. This was enabled by giving counties greater agency in how climate finance is utilized, particularly through incorporating climate activities in their budgets.

These factors once again demonstrate the limitations of simply establishing national coordination structures to ensure country ownership over coordination, and the ways in which CSOs and donors have had to step up to fill coordination gaps, slowly leading to a shift toward coordination approaches with greater donor influence, as seen in Zambia.

4.2.2. Zambia

In Zambia, the evolution of coordination has been strongly influenced by donor agendas, but has recently also been dominated by government agencies’ efforts to assert their own authority in coordination. The latter efforts have not only taken place vis-à-vis donors, but also internally among government agencies. A key bone of contention has been the question of which government entity should be mandated to lead climate finance coordination. In this respect there has been distinct competition between ministries of planning and finance on the one hand, and more technically oriented ministries of environment and natural resources on the other. Other government actors, such as the national disaster management agency, have also vied for positions in leading climate finance coordination.

Amidst these organizational struggles, opposing discursive claims have been made, each seeking to justify vis-à-vis each other and political leaders why one particular ministry was more suited to coordinate than others. Ministries of finance and planning have argued that climate funding should be coordinated by those who plan and conduct development on behalf of the nation (rather than technocrats), whereas ministries of environment and natural resources have argued that they, as technical specialists, should be leading coordination. Meanwhile, the disaster management agency has pointed out that acting swiftly on droughts and floods is a key capacity in coordination, while the ministry of agriculture has emphasized that it has the necessary ‘boots’ on the ground to support adaptation.

Behind these rationales lie more fundamental interests. This includes the opportunity to have a strong say in the allocation of funds, and the leverage that comes from this. Moreover, climate finance coordination constitutes a potential platform to challenge or consolidate sectoral boundaries. For example, for technical sector agencies the notion that ministries of planning and finance should coordinate climate finance constitutes a potential imposition on their own sectoral planning and associated donor financing. Likewise, as a developing arena, climate change constitutes an opportunity for government agencies to expand their respective mandates and reach. For example, climate change adaptation has been applied by some central state agencies as a legitimate means to establish state authority over land, water, and agricultural production in rural areas where such authority is otherwise weak (Funder et al., Citation2018).

In pursuing these interests, government agencies have engaged pragmatically with donor efforts that support their position and preferences. Ministries of finance and planning have thus aligned with the World Bank managed CIF funds, and ministries of environment and natural resources with the UNDP and UN climate funds, while others have engaged directly with bilateral donors without engaging coordination mechanisms. From this basis, they have sought to increasingly influence the coordination mechanisms, seeking to embed them in government structures as discussed in the previous section. In this respect, the evolution of a cross-sectoral government coordination mechanism for climate finance can be seen as a political compromise. In this arrangement, the current Ministry of National Development Planning chairs an overall steering committee, while the current Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources chairs a handful of Technical Committees, whose subcommittees are led by other key actors – thus giving a degree of influence to all. Even so, contestations continue, fuelled by agencies who feel they should have greater say, and donors seeking to push coordination mechanisms in their preferred direction.

The Zambian situation thus highlights how control as a motivator for coordination has a strong political component (see e.g. Lundsgaarde et al., Citation2018), and that differing interests among government agencies have contributed further to fragmentation of the climate finance coordination landscape. The unsettled nature of the landscape in Zambia is thus not only the result of donor influence, or of government influence, but rather of the combined effects of actors pursuing their interests in a contested process.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this paper is to explore how technical and political factors influence climate finance coordination in different country contexts. We did this by drawing findings from two countries, Kenya and Zambia, with varying degrees of country ownership and donor influence. This has allowed us to investigate how contextual differences create similarities and divergences in how climate finance is coordinated.

Despite both countries historically being characterized by a strong donor influence within the climate finance landscape, Kenya has recently institutionalized a lot of its coordination practices, embedding them within national government policies and mandated coordination structures. It could be argued that this institutionalization represents a shift toward greater country ownership over coordination in the country. In Zambia, however, coordination is less inclined toward a strong country-ownership arrangement, with donors not only having greater influence over how climate finance is coordinated, but donors and government actors interacting in a coordination landscape that remains more contested and in flux. This allows us, ultimately, to explore whether county ownership matters for coordination overall.

Firstly, we find that climate finance coordination takes place regardless of the level of country ownership. In Kenya, the presence of a more advanced policy and legal framework does translate to a more ‘formalised’ coordination. However, the comparatively weaker legal framework in Zambia does not automatically lead to less coordination in the country, as coordination practices driven by donors and other non-governmental actors emerge to fill these gaps. Furthermore, although coordination structures are established in Kenya, capacity restraints, poor utilization, and conflicting interests serve as barriers to how well these coordination mechanisms operate.

Secondly, despite differences in levels of country ownership, both countries demonstrate that the extent to which technical factors either enable or hinder coordination is ultimately shaped by political factors. For example, fragmentation of the climate finance landscape in both countries is augmented by the presence of multiple interests across different actors. Furthermore, the lack of capacity and resources for coordination is partially a result of a lack of political will and motivation at higher political levels to allocate resources for climate finance coordination. Power dynamics also play a role, with the extent to which coordination is prioritized being dependent on the interests of more powerful ministries or donors. This highlights the need to tackle the underlying political contestations that are creating technical coordination challenges to begin with, regardless of how country driven a coordination process is.

Finally, both countries also demonstrate the presence of diverging, deep-seated interests between and among governmental actors and donors, which appears to be the overarching political factor hampering coordination. In Zambia, this appears in the form of institutional struggles over who should lead coordination, with different donors having different views on which national authorities are best suited to do so, and, as a consequence, pulling in different directions. In Kenya, the agendas and interests of bilateral donors often do not align with government objectives or expected outcomes, meaning that the government is often less willing to engage with them, hampering coordination overall. Ultimately, efforts to enhance coordination through developing national structures, frameworks and coordination mechanisms will only go so far when there are power dynamics at play that hamper coordination.

This paper’s approach to country ownership focuses particularly on ownership of coordination of climate finance. It is, however, important to emphasize that broader definitions of country ownership also include aspects such as involvement of local and marginalized communities in agenda setting, alignment with national priorities, and direct access modalities (Omukuti, Citation2020b, Citation2020a; Zamarioli et al., Citation2020) Further research could unpack additional variables of country ownership and their role in influencing coordination outcomes, and could also explore the relationship between coordination and effectiveness, including whether coordination leads to more effective climate action.

6. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that underlying political factors, relating to conflicting interests, different framings and discourses around development and climate change, political will, and turf wars over power and control, play a substantive and overarching role in hampering country-led climate finance coordination in Kenya and Zambia. These findings challenge the normative assumption within the aid effectiveness literature in favour of country ownership, as coordination challenges arise in both countries regardless of whether there are high or low levels of country ownership over coordination.

As such, it could be argued that incremental changes, such as creating new coordination mechanisms and capacity building aiming to address technical barriers, are, whilst important, insufficient to enhance climate finance coordination unless the political barriers outlined above are also addressed. While technical and institutional capacity building can be a good enabler to facilitate increased coordination, it may ultimately be unable to overcome the political barriers that are hampering good outcomes in coordination. Based on this, three policy recommendations emerge for how political barriers can be tackled to enhance climate finance coordination.

Firstly, climate change and climate finance need to be prioritized at higher political levels to ensure that existing coordination structures are applied and enforced. In Kenya, this will enable progress to be made in establishing the National Climate Fund and its corresponding bodies, which will have the mandate for coordinating climate finance in the country. In Zambia, this could lead to greater clarity and dialogue over where the mandate for coordination should lie.

Secondly, multilateral and bilateral donors need to ensure that their actions are in line with the priorities of the government and reflect national needs. This could be done through donors engaging with governmental actors in the conception stages of project development as well as in implementation. In Kenya, this could lead to a greater willingness of governmental bodies to coordinate their activities with donors, reducing duplication and mutually enhancing benefits. In Zambia, this could help overcome challenges around institutional legitimacy, and turf and power dynamics, which are leading to further fragmentation.

Finally, as coordination barriers are inherently political, improving coordination will inevitably mean that most actors will have to compromise on some of their priorities, particularly as the presence of deep-seated interests appears to be a key factor hampering coordination in both countries. As such, there is a need to go beyond technical and institutional perspectives of climate finance coordination and make visible the winners and losers of various coordination mechanisms and structures. Increased dialogue and cooperation between relevant stakeholders, as well as transparency around interests and commitments could help in this regard.

Overall, this study provides valuable insights about how the highly complex finance landscape at the international level translates into climate finance coordination challenges at the national level, particularly within an African context. The study demonstrates that objectively favourable country characteristics, such as greater country ownership, with a well-established policy and legal framework, do not always translate into an enabling environment for more effective national coordination. Instead, underlying political factors often override these more technical advantages. This highlights the need to foster a politicized understanding of coordination more broadly, particularly the need for investigating deep-seated interests and power dynamics that may be shaping coordination.

This is an important contribution to the existing literature on climate finance coordination, supplementing the theory on the politics of coordination with tangible empirical evidence. Furthermore, this study reaffirms calls from the aid effectiveness literature to foster a less technocratic understanding of country ownership. It challenges dominant norms around greater national ownership automatically being a ‘solution’ for a more effective utilization of funds; country ownership needs to be paired with an examination of the role of different actors within the finance landscape and the discursive practices shaping their interaction.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank everyone who offered their valuable time during our interviews. This work was supported by The Swedish Research Council under grant number 2017–05591 and was part of a larger multi-year project titled ‘Share or Spare? Explaining the Determinants and Nature of Climate Finance Coordination’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdel-Malek, T. (2015). The global partnership for effective development cooperation: origins, actions and future prospects. Bonn: DIE. Available at: https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/Studies_88.pdf.

- Abrahamsen, R. (2000). Disciplining democracy: Development discourse and good governance in Africa. Zed Books.

- Adaptation Fund. (2021). Adaptation Fund Doubles the Amount of Funding Countries Can Access, Enhancing Access to Climate Finance Among Most Vulnerable. Available at: https://www.adaptation-fund.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Press-release-040821-Adaptation-Fund-Doubles-the-Amount-of-Funding-Countries-Can-Access-2.pdf.

- Ameli, N., Drummond, P., Bisaro, A., Grubb, M., & Chenet, H. (2020). Climate finance and disclosure for institutional investors: Why transparency is not enough. Climatic Change, 160(4), 565–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02542-2

- Amerasinghe, N. M., Thwaites, J., Larsen, G., & Ballesteros, A. (2017). Future of the Funds: Exploring the Architecture of Multilateral Climate Finance. World Resources Institute. Available at: https://www.wri.org/publication/future-of-the-funds (Accessed: 26 February 2020).

- Benvenisti, E., & Downs, G. W. (2007). The Empire’s New Clothes: Political Economy and the Fragmentation of International Law. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 976930. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=976930 (Accessed: 27 February 2020).

- Biermann, F., Davies, O., & van der Grijp, N. (2009). Environmental policy integration and the architecture of global environmental governance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 9(4), 351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-009-9111-0

- Bigsten, A. (2006). Donor coordination and the uses of aid. Report. Available at: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/2723 (Accessed: 17 July 2020).

- Bourguignon, F., & Platteau, J.-P. (2015). The hard challenge of Aid coordination. World Development, 69, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.12.011

- Delputte, S., & Orbie, J. (2014). The EU and donor coordination on the ground: Perspectives from Tanzania and Zambia. The European Journal of Development Research, 26(5), 676–691. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.11

- Dzebo, A., Shawoo, Z., & Kwamboka, E. (2020). Coordinating climate finance in Kenya: technical measures or political change? Available at: https://www.sei.org/publications/coordinating-climate-finance-in-kenya-technical-measures-or-political-change/ (Accessed: 24 August 2020).

- Easterly, W., & Williamson, C. R. (2011). Rhetoric versus reality: The best and worst of Aid agency practices. World Development, 39(11), 1930–1949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.027

- Fraser, A., & Whitfield, L. (2009). The Politics of Aid: African Strategies for Dealing with Donors.

- Funder, M., & Dupuy, K. (2022). Climate finance coordination from the global to the local: Norm localization and the politics of climate finance coordination in Zambia. The Journal of Development Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2022.2055467

- Funder, M., Mweemba, C., & Nyambe, I. (2018). The politics of Climate Change adaptation in development: Authority, resource control and state intervention in rural Zambia. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(1), 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1277021

- GCF. (2017). Guidelines for enhanced country ownership and country drivenness. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/guidelines-enhanced-country-ownership-country-drivenness.pdf.

- Gkeredakis, E. (2014). The constitutive role of conventions in accomplishing coordination: Insights from a complex contract award project. Organization Studies, 35(10), 1473–1505. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614539309

- Goldberg, J., & Bryant, M. (2012). Country ownership and capacity building: The next buzzwords in health systems strengthening or a truly new approach to development? BMC Public Health, 12(1), 531. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-531

- Government of Kenya. (2016). The Kenya Climate Change Act. Available at: http://www.environment.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/The_Kenya_Climate_Change_Act_2016.pdf.

- Government of Kenya. (2017). National Policy on Climate Finance. Available at: http://www.environment.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/The-National-Climate-Finance-Policy-Kenya-2017-1.pdf.

- Ha, S., Hale, T., & Ogden, P. (2016). Climate finance in and between developing countries: An emerging opportunity to build On. Global Policy, 7(1), 102–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12293

- Halonen, M., Illman, J., Klimscheffskij, M., & Sjöblom, H. (2017). Mobilising climate finance flows: Nordic approaches and opportunitie. Nordic Council of Ministers. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/financial/2017docs/nordic-climatefinance.pdf.

- Hasselskog, M. (2020). What happens to local participation when national ownership gets stronger? Initiating an exploration in Rwanda and Cambodia. Development Policy Review, 38(S1), O91–O111. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12488

- Hayman, R. (2009). From Rome to Accra Via Kigali: ‘Aid Effectiveness’ in Rwanda. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1484139. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00460.x.

- Keohane, R. O., & Victor, D. G. (2016). Cooperation and discord in global climate policy. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 570–575. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2937

- Lancaster, C. (1999). Aid to Africa: So much To Do, So little done. 1st edition. University of Chicago Press.

- Leiderer, S. (2015). Donor coordination for effective government policies? Journal of International Development, 27(8), 1422–1445. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3184

- Linn, J. F. (2009). Aid coordination on the ground: Are joint country assistance strategies the answer? SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1492212. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1492212.

- Lundsgaarde, E., Dupuy, K., & Persson, Å. (2018a). Coordination challenges in climate finance. Available at: https://www.sei.org/publications/coordination-challenges-climate-finance/ (Accessed: 27 February 2020).

- Lundsgaarde, E., Fejerskov, A. M., & Skovgaard, J. (2018b). Analysing climate finance coordination. Working Paper 2018:10. DIIS Working Paper. Available at: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/204626 (Accessed: 27 February 2020).

- Lundsgaarde, E., & Keijzer, N. (2019). Development cooperation in a multilevel and multistakeholder setting: From planning towards enabling coordinated action? The European Journal of Development Research, 31(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-018-0143-6

- McGee, R., & Heredia, I. G. (2012). Paris in Bogotá: The Aid Effectiveness Agenda and Aid Relations in Colombia. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2016689. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2012.00567.x.

- Nakhooda, S., & Jha, V. (2014). Getting it together: Institutional arrangements for coordination and stakeholder engagement in climate finance. GIZ. Available at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9200.pdf.

- OECD. (2005). The Paris Declaration on Aid effectiveness. Organisation for Economic Development (OECD).

- Okhuysen, G. A., & Bechky, B. A. (2009). 10 Coordination in organizations: An integrative perspective. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 463–502. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903047533

- Olivié, I., & Pérez, A. (2016). Why don’t donor countries coordinate their aid? A case study of European donors in Morocco’. Progress in Development Studies, 16(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464993415608082

- Omukuti, J. (2020a). Challenging the obsession with local level institutions in country ownership of climate change adaptation. Land Use Policy, 94, 104525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104525

- Omukuti, J. (2020b). Country ownership of adaptation: Stakeholder influence or government control? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 113, 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.04.019

- Peterson, L., & Skovgaard, J. (2019). Bureaucratic politics and the allocation of climate finance. World Development, 117, 72–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.12.011

- Pickering, J., Betzold, C., & Skovgaard, J. (2017). Special issue: Managing fragmentation and complexity in the emerging system of international climate finance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9349-2

- Pickering, J., Jotzo, F., & Wood, P. J. (2015a). Sharing the global climate finance effort fairly with limited coordination. Global Environmental Politics, 15(4), 39–62. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00325

- Pickering, J., Skovgaard, J., Kim, S., Roberts, J. T., Rossati, D., Stadelmann, M., & Reich, H. (2015b). Acting on climate finance pledges: Inter-agency dynamics and relationships with Aid in contributor states. World Development, 68, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.033

- Rakner, L. (2012). Foreign Aid and Democratic Consolidation in Zambia, 2012(016).

- Roberts, J. T., & Weikmans, R. (2017). Postface: Fragmentation, failing trust and enduring tensions over what counts as climate finance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9347-4

- Roberts, J. T., Weikmans, R., Robinson, S. A., Ciplet, D., Khan, M., & Falzon, D. (2021). Rebooting a failed promise of climate finance. Nature Climate Change, 11(3), 180–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-00990-2

- Sjöstedt, M. (2013). Aid effectiveness and the Paris Declaration: A mismatch between ownership and results-based management? Public Administration and Development, 33(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1645

- Skovgaard, J. (Forthcoming). Climate Finance Coordination Across Scales: Politics and Depoliticization in Practice.

- Smith, J. B., Dickinson, T., Donahue, J. D., Burton, I., Haites, E., Klein, R. J., & Patwardhan, A. (2011). Development and climate change adaptation funding: Coordination and integration. Climate Policy, 11(3), 987–1000. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2011.582385

- Steckel, J. C., Jakob, M., Flachsland, C., Kornek, U., Lessmann, K., & Edenhofer, O. (2017). From climate finance toward sustainable development finance. WIRES Climate Change, 8(1), e437. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.437

- UNFCCC (2014). What are the technology needs of developing countries? UNFCC handbook.

- UNFCCC (2015). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Available at: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf.

- van Asselt, H., & Zelli, F. (2014). Connect the dots: Managing the fragmentation of global climate governance. Environmental Economics and Policy Studies, 16(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-013-0060-z

- Weikmans, R., & Roberts, J. T. (2019). The international climate finance accounting muddle: Is there hope on the horizon? Climate and Development, 11(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1410087

- Whitfield, L. (2009). The Politics of Aid: African Strategies for Dealing with donors. 1st edition. Oxford . Oxford University Press.

- Winckler, O. A., & Therkildsen, O. (2007). Harmonisation and alignment: The double-edged swords of budget support and decentralized aid administration. Danish Institute for International Studies.

- Zamarioli, L. H., Pauw, P., & Grüning, C. (2020). Country ownership as the means for paradigm shift: The case of the green climate fund. Sustainability, 12(14), 5714–5718. doi:10.3390/su12145714