ABSTRACT

We study the mapping and reporting of climate-related risks among firms listed on the NasdaqOMX stock exchange in Stockholm in four goods-producing industries. Our study contains two parts: (i) a study of the firms’ external communication through their annual reports, sustainability reports and webpages, and (ii) a follow-up survey of the top management team. The survey contains quantitative questions and free text answers, which provide additional insights into the mapping and risk-handling of climate-related risks among the firms. We find that firms are likely to engage in some form of mapping and reporting of climate-related risks, but there are variations among the firms. Furthermore, the management of climate-related risks appears to be a residual issue for most firms with little active engagement from the management team or board of directors.

Key policy insights

Public policies and private initiatives, such as the EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive/Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (NFRD/CSRD), the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities, and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD), may redirect and accelerate investments promoting a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy.

Although most firms map and report climate-related risks, the understanding of the nature of these risks, of underlying problems, and of what a climate transition implies, varies across firms and industries.

The success of the EU’s NFRD/CSRD, the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities, and TCFD requires an improved understanding of climate-related risks among the firms and a more proactive engagement of the management team.

Policymakers must provide firms with additional guidance aimed at improving their understanding of climate-related risks and thus their capacity to manage these risks.

Firms need to, individually and jointly, revise their theoretical and empirical understandings of climate-risk management and especially the role climate-related risks play in the new policy setting.

The TCFD has an important role to play, but as a voluntary initiative, it is insufficient to generate change among all firms.

1. Introduction

Pressures on firms to map and report on climate-related risk are growing. Investors are increasingly concerned about financial losses caused by climate change (Bos & Gupta, Citation2019) resulting in higher borrowing costs for firms with relatively high climate-related vulnerabilities (Kling et al., Citation2021). Investors require more climate-related disclosures (Hinze & Sump, Citation2019), and those firms that do not openly provide such information face growing scepticism from financial market actors (Fink, Citation2020; Krasodomska & Cho, Citation2017). Pressures to map and report on climate-related risks are also coming from non-governmental organizations (Rodriquez-Melo & Mansouri, Citation2011; Steger et al., Citation2007) partially aided by social-media campaigns (Sogari et al., Citation2017). Mapping and reporting climate-related risks are now rapidly becoming part of corporate and public policy. For example, the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was set up by the Financial Stability Board, a collaboration between major central banks and financial regulators, following the global financial crisis in 2008/09. Its aim was to encourage firms and investors to map and disclose climate-related risks to reduce the risk of a future climate-induced financial crisis. In the European Union, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), launched in 2014, mandates firms with more than 500 employees to map and report climate risks. However, the Directive provides few guidelines on how to map and which specific climate-related risks to consider. The NFRD was replaced in 2021 by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which aims to provide more guidance to firms on how to map and report on climate-related risks (European Commission, Citation2021).

In theory, mapping and reporting of climate risks may appear simple. Mapping and reporting of these risks have been found to provide a partially useful tool in identifying critical risks, adaptation options and investment priorities, aligning and integrating action with existing firm risk management (Street & Jude, Citation2019). However, studies have shown that there is a lack of a common view among actors of what constitutes a climate-related risk, how to map them, and how to communicate the risks internally and externally with stakeholders (Kapitan et al., Citation2019; Reinecke et al., Citation2012; Valente, Citation2012). How risks are mapped and reported thus varies from firm to firm (Helfaya et al., Citation2019). This is problematic in view of the need to provide external stakeholders with value-relevant, credible, and comparable measures of firm climate performance (Arvidsson, Citation2019; Arvidsson & Dumay, Citation2021). Researchers have questioned to what degree firms and investors actually utilize the information obtained from the mapping and reporting (Johnson et al., Citation2021; Reverte, Citation2020; Rowbottom & Lymer, Citation2009). On the other hand, studies have found that the quality of the mapping and reporting has improved over time (Cho et al., Citation2015; Demaria & Rigot, Citation2020; Russo-Spena et al., Citation2018).

In this paper, we study the mapping and reporting of climate-related risks among listed goods-producing firms on the Swedish NasdaqOMX stock exchange in Stockholm. The Swedish firms are interesting to study as they have a reputation for being front-runners when it comes to sustainability practices and reporting (see Cahan et al., Citation2016; KPMG, Citation2015; Citation2019). Furthermore, Sweden’s climate policies are also considered to be among the most stringent in the world (Anderson et al., Citation2020; Karlsson, Citation2021). For example, the Swedish Environmental Code was launched in 1999, and was at that time considered one of the most advanced, clearly stating the purpose to promote sustainable development, ensuring a healthy and sound environment for present and future generations.Footnote1 This suggests that the mapping and reporting of climate-related risks among these Swedish firms might be of relatively high quality.

Our study contains two parts: First, we study the firms’ external reporting of climate-related risks through their annual reports, sustainability reports and web pages. Here we focus primarily on which climate-related risks they report, over which time horizon, and whether they disclose the method they used to map the risks. Second, we study the responses from a survey on the mapping of climate-related risks, which we distributed to the firms’ Head of Sustainability and copied to the other members of the top management team (e.g. CEO, CFO, Investor Manager) during the summer of 2020. The survey contains both qualitative and quantitative questions, which allows an in-depth analysis of their mapping processes.

The rest of the paper has the following disposition. In Section 2 we discuss the background of non-financial reporting and the risks related to climate change. Section 3 presents the research methodology and the data. Section 4 contains the empirical results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Background

2.1 Climate-related risks

Broadly speaking, firms face two types of climate-related risks: physical risks and transition risks (Demaria & Rigot, Citation2020; Stern, Citation2013). Physical risks are from climate- and weather-related events stemming from a rise in temperatures (de Bruin et al., Citation2020), including a reduction in worker productivity due to higher temperatures (Kjellström et al., Citation2018), rising sea levels, and an increased frequency of extreme weather events such as flooding or droughts (Barro, Citation2009, Citation2015). Transition risks relate to the social changes due to climate change, i.e. changes to the economic, social, technical, and political environment within which the firm operates (Carney, Citation2015; Semieniuk et al., Citation2020). The potential impact of these social changes on the firm is as complex as they are diverse. Firms may face new and different demands from consumer and investor to reduce their climate impacts (Fink, Citation2020; Rodriquez-Melo & Mansouri, Citation2011). Policymakers may substantially increase the stringency of climate policies (Battiston et al., Citation2021). Consumer demand may shift from fossil-intensive products to green products (Fabris, Citation2020). Firms may find that some of their energy and/or technological assets become stranded and worthless (Bos & Gupta, Citation2019). The consequences of the transition risks are exacerbated if the transition to a low-carbon economy becomes a rapid and chaotic process rather than a slow steady process (Campiglo et al., Citation2018; Carney, Citation2015).

An additional layer of complexity is the time horizon. Some climate-related risks are short-term risks, other long-term risks, and some both short- and long-term risks. To account for the complexity, the TCFD and the CSRD recommend that firms employ scenario analysis to actively engage in strategic thinking about possible risks based on different future potential pathways of decarbonization. The role of scenarios is not to forecast, or predict, the exact outcome (Haigh, Citation2019). Instead, scenarios are used to engage in strategic thinking to prepare for many different possible future outcomes (Peterson et al., Citation2003). While forecasting often relies on one main forecasted outcome, scenarios aim to explore multiple potential futures based on many different assumptions about the (TCFD, Citation2021b). Although scenario analysis is a useful tool to consider the potential impact of climate-related risks, the feasibility of individual firms employing scenario analysis has been questioned. Most firms use forecasting but are unfamiliar with scenario planning. To employ scenario analysis, firms must obtain new knowledge and new capabilities (O’Dwyer & Unerman, Citation2020; O’Dwyer & Unerman, Citation2020).

2.2 Non-financial reporting

While remaining a voluntary practice, there are different theoretical motivations for why firms chose to map and disclose climate-related risks (see e.g. Lombardi et al., Citation2022). Firms with a strong climate record are incentivized to provide verifiable information about the firms’ climate impact to encourage investors to invest in the company (Arvidsson & Dumay, Citation2021; Hummel & Schlick, Citation2016; Shehata, Citation2014). Other theories suggest that firms disclose information to gain social approval among the public and to maintain their social legitimacy (Lombardi et al., Citation2022), in which case firms with a relatively large climate impact may voluntarily map and report climate-related risk to demonstrate to stakeholders that they take the question seriously. Firms may also employ a cost–benefit analysis to decide whether the gains, i.e. improved reputation or lower cost of capital, exceeds the costs of performing the mapping and reporting of climate-related risks and how resources to invest in the practice (Lombardi et al., Citation2022).

Mapping and reporting of climate-related risks is slowly moving beyond being a voluntary practice as policymakers increasingly view mapping and reporting of climate-related risks as an important practice to speed up the climate transition of the economy. The TCFD was initiated to encourage firms to map and disclose climate-related information to reduce the risk of a future financial crisis due to climate change. But it has since grown into also providing information for private investors on investment opportunities that the climate transition creates. Another policy initiative is The EU Green Deal, which stresses the importance to provide financial markets with high-quality information about firms’ climate impact and policies to assist investors in shifting capital from carbon-intensive investment projects to green projects (Sikora, Citation2021). The NFRD, or formally referred to as the EU directive (2014/95/EU) on non-financial information and diversity, has been transposed into national law in European countries. All large firms, with 500 employees or more, are required to map and report on climate-related risks. In Sweden, the limit was set at a lower level of 250 employees.

3. Research design and methods

Empirical studies on non-financial reporting commonly rely on indicators to assess the reporting. The simplest approach is to simply count the number of times a report contains certain words, such as climate, climate-related risks, scenarios, etc. This simple approach does not measure the quality of the reporting (Melloni et al., Citation2017; Plumlee et al., Citation2015). To assess the quality, some studies employ content analysis (Lombardi et al., Citation2022), for example, employing text analysis tools (de Franco et al., Citation2015; Lang & Stice-Lawrence, Citation2015; Tóth et al., Citation2022).

In our analysis, we explore the mapping and reporting of climate-related risks through both simple indicators and a survey to gain a greater understanding of the firms’ mapping processes. The analysis is split into two parts. First, a report study of the firm’s external communication through annual reports, sustainability reports and their webpages, Second, a survey, including both qualitative and quantitative questions, addressed to the Head of Sustainability of each firm and copied to the other members of the top management team (e.g. CEO, CFO, Investor Manager).

3.1 Study of external communications (report study)

We begin the analysis by studying the respective firm’s external communication with stakeholders through their annual reports and sustainability reports for the financial year 2019, as well as the respective firm’s web pages accessed during May 2020. The English versions of the reports and web pages are used. To classify the communication, we created a checklist with items based on previous research. The checklist is designed to cover the areas of understanding, mapping and reporting of climate-related risks. In the analysis these items will be coded either 1 (the reports and/or web pages include information related to this item) or 0 (the reports and/or web pages do not include information related to this item). Coding procedures always raise subjectivity concerns. Therefore, the checklist was tested on five firms’ reports and web pages by the two senior researchers and six master studentsFootnote2 involved in the coding procedure – all within the field of sustainable finance. This test resulted in some minor adjustments to the checklist and the coding document, see Supplementary Material, Appendix 1. To add to the robustness of the results, detailed coding instructions were structured, and coding reviews were conducted during the analyzing procedure.

3.2 Survey

The report study was followed by an in-depth survey distributed to the Head of Sustainability of each of the 111 firms in the population (see Data section below), during the summer of 2020. The response rate was high, 65 percent (see ), with variations across the industries from 55 percent (consumer staples) to 73 percent (industrial goods). A potential concern is that the survey sample is biased towards certain types of firms. The firms, which responded to the survey, were on average larger compared to the full sample of firms: the average total assets of the firms that responded were 39 billion SEK (4 billion USD) compared to 16 billion SEK (1.6 billion USD) for firms that did not respond. Furthermore, the report study shows (see below) that firms that are more active in mapping and reporting of climate0related risk are overrepresented in the survey. However, the difference between the full sample from the report study and the survey sample is relatively small.

Table 1. Population and survey sample information.

The survey questions were designed to complement the report study and thus contained similar questions. All survey questions include three response options: ‘yes’; ‘we are working on it’ and ‘no’. When appropriate the questionnaire includes open-ended qualitative follow-up questions where the respondent is invited to elaborate on his/her answer. Most responding firms included a written (qualitative) response, which provides important background information that improved the interpretation of the quantitative results.

The survey was distributed directly to the Head of Sustainability, and copied to the other members of the top management team (e.g. CEO, CFO, Investor Manager). The survey was sent out electronically on June 17, 2020, the month after the report-study was concluded. Due to the summer holidays, a deadline was set to August 10, 2020. Three reminders were sent out during this period. Considering that English is the corporate language in most of the largest Swedish companies, the survey was in English. The final version of the survey is presented in Supplementary Material Appendix 2.

3.3 Data sample

Our data sample consists of firms listed on the NasdaqOMX stock exchange in Stockholm. These firms are large and have a significant environmental and economic impact on society. Because they are large, they are likely to engage in mapping and reporting of climate-related risks voluntarily (Stiller & Daub, Citation2007) although most of them are also required by regulation to report on climate-related risks. The sample is limited to firms from four goods-producing industries with a relatively large direct climate impactFootnote3: materials, industrial goods, consumer discretionary and consumer staples (see and Supplementary Material Appendix 3). There are 111 firms traded in these four industries. For the report study, our dataset covers the full population of 111 firms. However, as these firms are large, their average sale in 2020 was 24 billion SEK and their average total assets were 31 billion SEK, they are unrepresentative of the entire population of all firms in Sweden. Our results are thus not representative of the full population of firms. Furthermore, the number of firms in the consumer staples industry and the materials industry is relatively small, 8 and 18, respectively. Consequently, some of the differences in results among the industries are potentially caused by the small number of firms. Nevertheless, it is interesting to divide the firms into industries as the four industries are clearly different technologically and economically. They are also located at different places in the value chain. The material-producing industry is an upstream industry that primarily sells to downstream firms in the industrial goods and consumer discretionary/staples industries. Consumer discretionary/staples sell mostly to households. The material industry is among the most carbon- and energy-intensive industries in the economy, while industrial goods and consumer discretionary/staples are less carbon-intensive (Andersson, Citation2020). However, the supply chains of the industrial goods and consumer discretionary/staples industries are relatively carbon-intensive as they consume intermediate goods produced by the materials and agricultural industries. Their supply chains also tend to be more international than the material industries in Sweden.

4. Empirical results

4.1 Report study

and present the results of the report study. reports on whether firms map climate-related risks and which climate-related risks they map (physical and/or transition). reports on whether the firms use a specific method to map risks, and whether this method includes scenario analysis. For each question two statistics are presented: the first statistic presents the result for the full population of firms and the second statistic is the result for the firms that also responded to the survey.

Table 2. Firms’ mapping of climate-related risks according to their yearly/sustainability reports and web pages, in percent of all firms.

Table 3. Firms’ mapping of climate-related risks according to their yearly/sustainability reports and web pages: method, time horizon and scenarios, in percent of all firms.

The majority of firms, between 69 percent (consumer discretionary) and 100 percent (consumer staples) state that they are mapping sustainability risks in their reports. The percentage is higher among the firms that responded to the survey, which might indicate that the survey sample is potentially biased towards firms with active climate-risk management. Most firms present the method they used to map risks; however, between one-quarter and one-third of all firms do not disclose this information. Material goods firms are the least likely to report the mapping method. Again, the firms that responded to the survey are more likely to disclose information on how the mapping of climate-related risks was conducted.

Most firms map both physical risks and transition risks. Only a minority of firms discuss climate-related risks in general without any reference to physical or transition risks. The high degree of specificity indicates that firms are aware of the different types of climate-related risks. The mapping of physical risks is more common than the mapping of transition risks among the industrial goods industries and the consumer durables industries. For materials, transition risks are more commonly mapped than physical risks. This may be because the material industries are also likely to more directly be affected by a climate transition as their direct greenhouse gas emission levels are relatively high (Andersson, Citation2020). They also face few economic co-benefits from decarbonization, which makes decarbonization relatively costly (Åhman et al., Citation2017; Åhman & Nilsson, Citation2015). In other words, the material industries are likely to be more negatively affected by the climate transition. Our results suggest that the material-producing firms are aware of the potentially substantial climate-related risks they face. The industrial goods industry and the consumer discretionary industry, on the other hand, are less affected directly, but they are, to a greater extent, affected through their supply chains as they purchase most of the output from the material industry and turn it into products that are then sold to end consumers (Andersson, Citation2020). That only 21 percent of industrial goods firms and 45 percent of consumer discretionary firms consider transitional risks suggests they may be unprepared for major future risks to their firm.

Few firms report having adopted the TCFD recommendations. For example, none of the consumer staple firms use the TCFD although all firms in this industry map all types of climate-related risks. This result is in line with Bingler et al. (Citation2022) who found that the TCFD had no significant impact on the reporting of climate-related risks. The most likely industry to follow the TCFD recommendations is again the materials industry. This result may explain why the materials industries are more likely to consider transitional risks than the industrial goods and consumer discretionary industries.

Although most firms report the method they employ to map climate-related risks, they appear to use different methods. This lack of a common mapping and reporting framework has been raised in the literature as a major problem aggravating the credibility and comparability of this information, which is vital in credit and investment decision processes (see e.g. BIS, Citation2021).

Climate-related risks are rarely mapped and reported based on specific time horizons. Instead, firms report general risks without any specific time horizon applied to them. Fewer than 20 percent disclose risks that are either short-term or long-term in nature. The lack of a specific time horizon is also revealed by the small number of firms that present results from scenario analysis where future potential risks are explored. Overall, our analysis of the reports suggests that firms have a focus on the short-term and physical risks and less on the long-run and transition risks. This stands in contrast to a view from Finansinspektionen (Citation2016) that Swedish firms are more likely to face transition risks than physical risks. As the present temperature is deemed ‘sub-optimal’ for economic activity a rise in the temperature may bring economic benefits according to their assessment.

Although firms engage in climate risk mapping and reporting, it is important to consider to what extent the management team is actively involved in climate-risk management. The reaching of successful integration of sustainability perspectives is argued to rest on the attention given and legitimacy granted by the top management team (TCFD, Citation2017; Citation2021a). Unravelling the involvement of the management team in the report study, however, is difficult. Some insights can be gained by considering the following two factors: the share of a firm’s employees that are trained in the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) and the share of managers that are evaluated based on sustainability performance measures. The management of climate-related risks appears to be a residual issue for most firms with only 16 percent of all firms reporting that their managers are evaluated based on non-monetary sustainability goals. The written responses to the survey questions further suggest that sustainability performance has little impact on remuneration, if at all, compared to financial performance.

So far, the analysis has focused on the difference among the four industries. Next, we consider the size of the firm. Eleftheriadis and Anagnostopoulou (Citation2015) and Andrikopoulos and Kriklani (Citation2013) suggest that larger firms are more likely to report on climate-related risks than smaller firms. contains the bivariate correlation between the logarithm of the firm’s total assets and the respective questions from the report study. As a comparison, also contains the correlation between the responses and industry dummy variables to test if there is a statistically significant difference among the industrial industry. There is a clear size effect for all but one question (manager evaluation). The larger the firm, the more likely the firm is to map various climate-related risks, to employ scenario analysis and to have adopted the TCFD framework. These correlations are statistically significant at the 5 percent significance level. Although the size of the firm is a clear predictor of the results, some of the described industrial differences are also found to be statistically significant. Specifically, the materials industry and the consumer staples industry are more likely to map transition risks than the industrial goods industry. The materials industry is also statistically more likely to map climate-related risks using the TCFD framework. The result that the consumer staple industry is more likely to map risks over different time horizons and types of risks is also statistically significant.

Table 4. Bivariate correlation table between firm size, industry, and mapping and reporting of climate-related risks.

In summary, the report study reveals that larger firms are more likely to map and report on climate-related risks. There are also industry differences: the materials industry, with the highest carbon intensity, is most likely to actively consider climate-related risks than the other industries. Consumer staples are also likely to map and report risks, a result that is potentially explained by high levels of pressure from consumers. However, there are only 8 firms in this industry so the results should be interpreted with some care. The industrial goods and consumer discretionary industries are less likely to map climate-related risks. They are also less likely to follow a specific mapping and reporting method such as the TFCD.

4.2 Survey

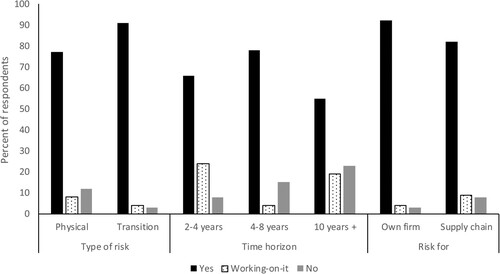

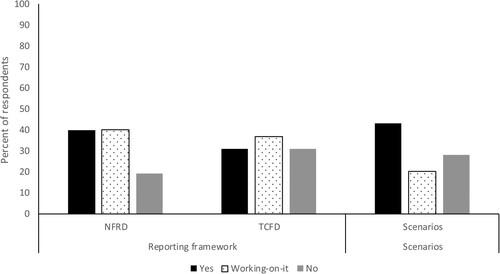

Next, we turn to a more detailed examination of the results from our survey. The survey questions are similar to the questions explored in the report study and provide additional insights, both qualitatively and quantitatively. The full results are shown in Supplementary Materials Appendix 4. The results for all firms are summarized in and .

Figure 1. Firms’ mapping of climate-related risks according to the survey results: type of risk and time horizon. In percent of all firms that responded to the survey.

Figure 2. Firms’ mapping of climate-related risks according to the survey results: employed frameworks and the use of scenario analysis. In percent of all firms that responded to the survey.

The results from the report study and the survey are similar but there are also important differences. For example, firms respond that they are as likely to map transition risks as they are mapping physical risks, while they are more likely to report on physical risks than transition risks (see and ). Firms are also more likely to respond that they map risks over many different time horizons, while their reporting rarely refers to a specific time horizon. Of all firms that responded to the survey, 80 percent map short-term risks or are working on mapping risks over this time horizon. As the time horizon increases, the likelihood of mapping climate-related risks is reduced. This result stands somewhat in contrast to the response from firms claiming that they are mapping transition risks. Few transition risks are likely to occur over the next two to four years and are more likely to occur over the long term as the global temperature increases and the climate transition gathers speed (Semieniuk et al., Citation2020; TCFD, Citation2017) although there is also the possibility of some short-term effects (Gambhir et al., Citation2021). The short-run focus suggests that some firms may miss important transition risks by focusing too much on the short term. Even the material industry and the consumer staples industry, which both tend to be the most active in mapping risks, have a lower probability of mapping long-term risks than short- and medium-term risks. Another difference compared to the report study is that there are more firms indicating in the survey responses that they have adopted the TCFD framework and that they employ scenario analysis compared to firms that actually do disclose this information in their external communication (see and ).

While most companies report mapping of climate-related risks, they are less likely to follow a specific mapping and reporting methodology. A minority of all companies’ reports are based on the recommendations in NFRD or TCFD. However, a large share of the firms reports that they are planning to start following them in the future (‘working-on-it’ response). The main outlier here is the consumer staples industry where 80 percent of companies respond that they already do follow the TCFD recommendations. However, there are only five firms in this industry. These results stand in contrast to the report study where we found a clear minority of firms disclosing that they used TCFD. This indicates that the firms are more likely to employ the framework than what they are disclosing in their sustainability reports.

Roughly half of all firms surveyed use some form of scenario analysis and 15–30 percent plan to use scenarios in the future. Again this is a higher share compared to the share of firms that report the results in their external communication. Only 5 percent of all firms report scenario analysis in their external reports. Although more firms employ scenario analysis than report it in their annual or sustainability reports, the written survey answers indicate large variations in how scenarios are conducted, the number of scenarios, and who is involved in the process of creating and exploring the scenarios. Fewer than ten companies overall involve the board or the management of their firms in the creation of the scenarios.

The written responses further reveal different perspectives among firms on what transition risk is. Some firms’ perceptions are closer in line with the theoretical perspective that a transition risk entails a major change in the economic, social, technological or political environment the firm faces (see Section 2). While other firms use the terminology transition risks when they study short-term fluctuations in market conditions, which they map using yearly or bi-annual risk assessments based on e.g. consumer surveys. For example, one firm in the industrial goods industry writes:

[a]t the global level, we carry out bi-annual customer surveys to understand customer preferences. Locally, we continuously do customer surveys and other business intelligence to map risks and opportunities in the markets we operate in. (Industrial goods firm)

[m]arketing tracks consumer preferences by doing regular surveys in key markets. (Consumer discretionary firm)

[w]e listen to our ‘users’ because the use of our products hopefully long-term. (Consumer discretionary firm)

[t]he climate-related risks and opportunities that we have identified have been classified according to the TCFD model, including physical risks as well as transition risks. … [the firm] has a risk in not being able to keep up with the demand for these products or fulfilling demands tenders, as environmental care and risk assessment ins mandatory in all public tenders and has the likelihood to impact our finances for the next 25 years. (Industrial goods firm)

[f]or example, impact of potential/future regulatory changes is assessed to make sure we are prepared to adopt if necessary. It may be regulation such as CO2 tax, emissions factors for transport etc. (Consumer discretionary firm)

[e]fforts are put to highlight the ongoing discussions on the political scene not only in the annual assessments but also in the recurring review meetings. (Industrial goods firm)

[the firm] participates in various national and international industry organizations, as well as in other types of partnerships. The aim is to gain knowledge, and also to contribute actively to the development of areas where we have expertise and that are significant to our operations. (Consumer staples firm)

Second, the number of firms with a relatively high level of understanding of climate-related financial risk is likely to grow over time as they continue to develop their mapping and reporting skills. Some firms have clearly come further in the learning process and are engaging in relatively advanced scenario analysis, often with external partners with mapping skills that the firms lack.

The written answers to the survey questions suggest that the TCFD recommendations play an important role in guiding firms on how to map and report climate-related risk. For example, according to the responses, the adoption of the TCFD recommendations is a key driver towards scenario analysis. There is clearly an overlap between firms conducting mapping of long-term transition risks and using scenario analysis. However, there are more firms that use scenario analysis than there are firms that map long-term transition risks.

The written answers also reveal that several firms are in the process of developing the skills necessary to conduct e.g. scenario analysis. In other words, firms are going through a learning process. For example, two firms, among several write,

[we] are working to understand our wider sustainability risk and opportunities for the business, through further developing our enterprise risk management process. We will use the TCFD guidelines as part of this process. (Industrial goods firm)

[w]e have an ambitious ESG agenda and are constantly working with how to improve our pro-climate (and ESG) related activities … In this work and process development we use both EU guidelines and TCFD as guidelines and inputs. (Industrial goods firm)

5. Conclusions

We study the mapping and reporting of climate-related risks among listed firms on the NasdaqOMX stock exchange in Stockholm in four goods-producing industries. We conducted both a review of the firms’ external communication with stakeholders through their annual reports, sustainability reports and webpages, and a survey of the firm’s top management teams with quantitative and qualitative questions related to each firm’s mapping of climate-related risks.

Our results show that mapping and reporting of climate-related financial risks are common, but external reporting is often general and lacks details. The survey suggests that firms’ actual mapping is more detailed than they disclose to their stakeholders. However, there are significant differences among the firms in relation to how they map climate-related risks and their understanding of what constitutes a climate-related risk. For example, the survey responses suggest that several firms interpret transition risks as short-term fluctuations in market conditions. Some transition risks may affect the firm in the short run; however, most transition risks are more likely to occur in the long run. The short-term perspective may cause firms to underestimate the level of transition risks. Furthermore, several firms underestimate future transition risks by claiming that they perform long-term scenario analysis when they instead are engaged in short-term forecasting.

The differences among firms in their levels of understanding of what a climate-related risk is and in their mapping practices suggest that while most firms report mapping of climate-related risks, the actual number of firms that are fully engaged in the process is actually smaller. This result is potentially explained by firms being unfamiliar with mapping climate-related risks and the methods necessary to sufficiently map them. There is some evidence of learning over time, in particular among firms that have adopted the TCFD recommendations. These firms are more likely to engage in scenario planning, consider the long run, and to collaborate with external partners to fully explore potential economic, social, and political risks caused by climate change.

From a policy perspective, our results indicate that the EU’s move towards using mapping and reporting of climate-related risks to redirect financial flows from carbon-intensive to green investments to speed up the climate transition may fail, unless: (i) firms are assisted in learning how to map and disclose climate-related risks, for example, through improved mapping and reporting guidelines; and (ii) the management team and the board of directors within firms are encouraged to get directly involved in mapping and risk-assessment and risk-handling processes. Most firms treat climate-related risks as a residual or marginal issue, with little active involvement of the management team or their board of directors; this may explain some of the poor quality of the mapping and reporting. Without improved guidance from policy-makers on how to integrate these issues into the decision-making processes of firms, it is unlikely that the EU’s new policies such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and EU’s Taxonomy on Sustainable Activities will meet their intended aims to significantly impact on firms’ behaviour and financial investment decisions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lund University Finance Society (LINC) and the six finance students who, together with Susanne Arvidsson, conducted the coding of data: Marcus Abbestam, Olivia Ceplitis, Nina Maria Lancelot, Alexandra Stertman, Tim Mölle and Frej Örnberg. We are also grateful to Jon God, data analyst, who has been helpful in ensuring the robustness of the data coding. Comments by Staffan Jerneck, Erik Lindén and Xiaoni Li are gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 The finance students are all members of Lund University Finance Society (LINC).

3 GICS (Global Industry Classification Standard) developed by Morgan and Stanley Capital International and Standard and Poor’s Dow Jones Index.

References

- Åhman, M., & Nilsson, L. J. (2015). Chapter 5: Decarbonising industry in the EU: Climate, trade and industrial policy strategies. In C. Dupont, & S. Oberthur (Eds.), Decarbonisation in the EU: Internal policies and external strategies. Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 634-649.

- Åhman, M., Nilsson, L. J., & Johansson, B. (2017). Global climate policy and deep decarbonisation of energy-intensive industries. Climate Policy, 17(5), 634–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1167009

- Anderson, K., Broderick, J. F., & Stoddard, I. (2020). A factor or two: How mitigation plans of climate progressive nations fall short of the Paris-compliant pathways. Climate Policy, 20(10), 1290–1304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1728209

- Andersson, F. N. G. (2020). Effects on the manufacturing, utilities and construction industries of a decarbonization of the energy-intensive and natural-resource based industries. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 21, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2019.10.003

- Andrikopoulos, A., & Kriklani, N. (2013). Environmental disclosure and financial characteristics of the firm: The case of Denmark. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1281

- Arvidsson, S. (Ed.). (2019). Challenges with managing sustainable business: Reporting, taxation, ethics and governance. Vol 10. 1007/978-3-319-93266-8, pp. 403.

- Arvidsson, S., & Dumay, J. (2021). Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(3), 1091–1110. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2937

- Barro, R. J. (2009). Rare disasters, asset prices, and welfare costs. American Economic Review, 99(1), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.1.243

- Barro, R. J. (2015). Environmental protection, rare disasters and discount rates. Economica, 82(325), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12117

- Battiston, S., Dafermos, U., & Monasterlo, I. (2021). Climate risks and financial stability. Journal of Financial Stability, 54, 100867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2021.100867

- Bingler, J. A., Kraus, M., Leippold, M., & Webersinke, N. (2022). Cheap talk and cherry-picking: What ClimateBert has to say on corporate climate risks disclosures. Financial Research Letters, 9, 102776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.102776

- BIS. (2021). Climate-related risks – measurements and methodologies. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Bank for International Settlements.

- Bos, K., & Gupta, J. (2019). Stranded assets and stranded resources: Implications for climate change mitigation and global sustainable development. Energy Research & Social Science, 56, 101215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.025

- Cahan, S. F., De Villiers, C., Jeter, D. C., Naiker, V., & Van Staden, C. J. (2016). Are CSR disclosures value relevant? Cross-country evidence. European Accounting Review, 25(3), 579–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2015.1064009

- Campiglo, E., Dafermos, Y., Monnin, P., Ryan-Collins, P., Schotten, G., & Tanka, M. (2018). Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0175-0

- Carney, M. (2015). Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – climate change and financial stability. Speech at Lloyd’s of London, 29 September 2015.

- Cho, C. H., Michelon, G., Patten, D. M., & Roberts, R. W. (2015). CSR disclosure: The more things change … ? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 28(1), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-12-2013-1549

- de Bruin, K., Hubert, R., Evain, J., Clapp, C., Dahl, M. D., Bolt, J., & Sillmann, J. (2020). Physical climate risks and the financial sector – synthesis of investors’ climate information needs. In W. Leal Filho, & D. Jacobs (Eds.), Handbook of climate services. Climate change management. Springer Climate Change Management, pp. 135–156.

- de Franco, G., Hope, O.-K., Vyas, D., & Zhou, Y. (2015). Analyst report readability. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(1), 76–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12062

- Demaria, S., & Rigot, S. (2020). Corporate environmental reporting: Are French firms compliant with the task force on climate financial disclosures’ recommendations? Business Strategy and Environment, 30(1), 721–738. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2651

- Eleftheriadis, I. M., & Anagnostopoulou, E. G. (2015). Relationships between corporate climate change disclosures and firm factors. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(8), 780–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1845

- European Commission. (2021). Directive of the European Parliament and the Council Amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as regards corporate sustainable reporting.

- Fabris, N. (2020). Financial stability and climate change. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 3(3), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.2478/jcbtp-2020-0034

- Finansinspektionen. (2016). Climate change and financial stability. Ref 15-13096.

- Fink, L. (2020). A fundamental reshaping of finance. Retrieved March 27, 2020, https://www.blackrock.com/au/individual/larry-fink-ceo-letter

- Gambhir, A., George, M., McJeon, H., Arnell, N. W., Bernie, D., Mittal, S., Köberle, A. C., Lowe, J., Rogelj, J., & Montieth, S. (2021). Near-term transition and longer-term physical climate risks of greenhouse Gas emissions pathways. Nature Climate Change, 12(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01236-x

- Haigh, N. (2019). Scenario planning for climate change. Routledge.

- Helfaya, A., Whittington, M., & Alawattage, C. (2019). Exploring the quality of corporate environmental reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(1), 163–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2015-2023

- Hinze, A.-K., & Sump, F. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and financial analysts: A review of the literature. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 10(1), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-05-2017-0043

- Hummel, K., & Schlick, C. (2016). The relationship between sustainable performance and sustainability disclosure – reconciling voluntary disclosure theory and legitimacy theory. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 35(5), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2016.06.001

- Johnson, O. W., du Pont, P., & Gueguen-Teil, C. (2021). Perceptions of climate-related risk in Southeast Asia’s power sector. Climate Policy, 21(2), 264–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1822771

- Kapitan, S., Kennedy, A.-M., & Berth, N. (2019). Sustainably superior versus greenwasher: A scale measure of B2B sustainable positioning. Industrial Marketing Management, 76, 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.08.003

- Karlsson, M. (2021). Sweden’s climate act – its origin and emergence. Climate Policy, 21(9), 1132–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.1922339

- Kjellström, T., Feyberg, C., Lemke, B., Otto, M., & Briggs, D. (2018). Estimating population heat exposure and impacts on working people in conjunciton with climate change. International Journal of Biometeorol, 62(3), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-017-1407-0

- Kling, G., Volz, U., Murinde, V., & Ayas, S. (2021). The impact of climate vulnerability on firm’s cost of capital and access to finance. World Development, 137, 105131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105131

- KPMG. (2015). KPMG international survey of corporate responsibility reporting. KPMG International.

- KPMG. (2019). KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2017: The road ahead. KPMG.

- Krasodomska, J., & Cho, C. H. (2017). Corporate social responsibility disclosure: Perspectives from sell-side and buy-side financial analysts. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 8(1), 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-02-2016-0006

- Lang, M., & Stice-Lawrence, L. (2015). Textual analysis and international financial reporting: Large sample evidence. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(2-3), 110–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2015.09.002

- Lombardi, R., Schimperna, F., Paoloni, P., & Galeotti, M. (2022). The climate-related information in the changing EU directive on non-financial reporting and disclosure: First evidence by large Italian companies. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 23(1), 250–273. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-04-2021-0117

- Melloni, G., Caglio, A., & Perego, P. (2017). Saying more with less? Disclosure conciseness, completeness and balance in integrated reports. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 36(3), 220–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2017.03.001

- O’Dwyer, B., & Unerman, J. (2020). Shifting the focus on sustainability accounting from impacts to risks and dependencies: Researching the transformative potential of TCFD reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(5), 1113–1141. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-02-2020-4445

- Peterson, G. D., Cumming, G. S., & Carpenter, S. R. (2003). Scenario planning: A tool for conservation in an uncertain world. Conservation Biology, 17(2), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01491.x

- Plumlee, M., Brown, D., Hayes, R. M., & Marshall, R. S. (2015). Voluntary environmental disclosure quality and firm value: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34(4), 336–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2015.04.004

- Reinecke, J., Manning, S., & von Hagen, O. (2012). The emergence of a standards market: Multiplicity of sustainability standards in the global coffee industry. Organization Studies, 33(5-6), 791–814. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612443629

- Reverte, C. (2020). Do investors value the voluntary assurance of sustainability information? Evidence from the Spanish Stockmarket. Sustainable Development, 29(5), 793–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2157

- Rodriquez-Melo, A., & Mansouri, S. A. (2011). Stakeholder engagement: Defining strategic advantage for sustainable construction. Business Strategy and the Environment, 20(8), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.715

- Rowbottom, N., & Lymer, A. (2009). Exploring the use of online corporate sustainability reporting. Accounting Forum, 33(2), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2009.01.003

- Russo-Spena, T., Tregua, M., & De Chiara, A. (2018). Trends and drivers in CSR disclosure: A focus on reporting practices in the automotive industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(2), 563–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3235-2

- Semieniuk, G., Campiglio, E., Mercurse, J.-F., Volz, U., & Edwards, N. R. (2020). Low-carbon transition risks for finance. Wire’s Climate Change, 12(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.678

- Shehata, N. F. (2014). Theories and determinants of voluntary disclosure. Accounting and Finance Research, 3(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5430/afr.v3n1p18

- Sikora, A. (2021). European green deal – legal and financial challenges of the climate change. ERA Forum, 21(4), 681–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-020-00637-3

- Sogari, G., Pucci, T., Aquilani, B., & Zanni, L. (2017). Millennial generation and environmental sustainability: The role of social media in consumer purchasing behavior of wine. Sustainability, 9(10), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101911

- Steger, U., Lonescu-Somers, A., & Salzmann, O. (2007). The economic foundations of corporate sustainability. Corporate Governance, 7(2), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700710739804

- Stern, N. (2013). The structure of economic modelling of the potential impacts of climate change: Grafting gross underestimation of risk onto already narrow science models. Journal of Economic Literature, 51(3), 838–859. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.51.3.838

- Stiller, Y., & Daub, C. H. (2007). Paving the way for sustainability communication: Evidence from a Swiss study. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(7), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.599

- Street, R. B., & Jude, S. (2019). Enhancing the value of adaptation reporting as a driver for action: Lessons from the UK. Climate Policy, 19(10), 1340–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1652141

- TCFD. (2017). Recommendations of the task force on climate-related financial disclosures. Final report. June 2017.

- TCFD. (2021a). 2021 status report. Task force on climate-related financial disclosures.

- TCFD. (2021b). Proposed guidance on climate-related metrics, targets, and transition plans. Task force on climate-related financial disclosures June 2021.

- Tóth, A., Suta, A., & Szauter, F. (2022). Interrelation between the climate-related sustainability and the financial reporting disclosures of the European automotive industry. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 24(1), 437–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-021-02108-w

- Valente, M. (2012). Theorizing firm adoption of sustaincentrism. Organization Studies, 33(4), 563–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612443455