ABSTRACT

Responding effectively to climate change requires an understanding of what shapes people’s individual and collective sense of agency and responsibility towards the future. It also requires transforming this understanding into political engagement to support systems change. Based on a national representative survey in Sweden (N = 1,237), this research uses the novel SenseMaker methodology to look into these matters. More specifically, in order to understand the social and institutional prerequisites that must be in place to develop inclusive climate responses, we investigate how citizens perceive their everyday life and future, and the implications for their sense of responsibility, agency, and political engagement. Our research findings show how citizens perceive and act on climate change (individually, cooperatively, and by supporting others), their underlying values, beliefs, emotions and paradigms, inter-group variations, and obstacles and enablers for change. The findings reveal that, in general, individual and public climate action is perceived as leading to improved (rather than reduced) wellbeing and welfare. At the same time, climate anxiety and frustration about structural and governance constraints limit agency, whilst positive emotions and inner qualities, such as human–nature connections, support both political engagement and wellbeing. Our results shed light on individual, collective, and structural capacities that must be supported to address climate change. They draw attention to the need to develop new forms of citizen involvement and of policy that can explicitly address these human interactions, inner dimensions of thinking about and acting on climate change, and the underlying social paradigms. We conclude with further research needs and policy recommendations.

Key policy insights

In general, citizens perceive increased individual and public climate action as leading to improved (rather than reduced) wellbeing and welfare.

Effective responses to climate change require addressing underlying social paradigms (to complement predominant external, technological, and information-based approaches).

Such responses include increasing policy support for:

o learning environments and practices that can help individuals to discover internalized social patterns and increase their sense of agency and interconnection (to self, others, nature);

o institutional and political mechanisms that support citizen engagement and the systematic consideration of human inner dimensions (values, beliefs, emotions and associated inner qualities/capacities) across all sectors of work, by systematically revising organizations’ vision statements, communication and project management tools, working structures, policies, regulations, human and financial resource allocation, and collaboration; and

o nature-based solutions and other approaches to support the human–nature connection.

1. Introduction

Despite decades of negotiations and wide-ranging policies and measures at international, national, and local levels, efforts to address climate change have not generated the results needed to avoid potentially catastrophic futures (IPCC, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; UNFCCC, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Sweden is no exception. The country is considered a forerunner in climate mitigation and adaptation, with high levels of governmental and public awareness (Blennow & Persson, Citation2009; SEPA, Citation2021). However, if the world's population adopted the Swedish lifestyle, the equivalent of 4.2 Earths would be needed to sustain everyone (SEPA, Citation2022; WWF, Citation2016, Citation2020).

Part of the policy challenge relates to the fact that climate change tends to be framed and addressed as an external, technical challenge (Leichenko & O’Brien, Citation2020). While important, the current focus on external factors, such as wider socio-economic structures and technology, has proven to be insufficient (IPCC, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). In particular, it has narrowed the possibilities for deeper change that also tackles the root causes of climate change: the inner (individual and collective) mental states that underlie social norms and paradigms and continually produce and reproduce the climate crisis (EEA, Citation2021; Filho & McCrea, Citation2018; Geels & Schot, Citation2007; Hunecke, Citation2018; Köhler et al., Citation2019; Upham et al., Citation2019; Wamsler & Bristow, Citation2022; Wamsler et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, scholars and practitioners are increasingly emphasizing the need to complement the dominant external approaches of policy with an inner orientation to support transformation towards sustainability (Adger et al., Citation2013; Grušovnik, Citation2012; Hulme, Citation2009; Ives et al., Citation2020; O’Brien, Citation2018; Rimanoczy, Citation2014; Waddock, Citation2015; Wamsler et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Woiwode et al., Citation2021). This claim is supported by systems theory, which views inner dimensions (i.e. individual and collective mindsets, values, beliefs, paradigms, and associated inner qualities/capacities) as a deep leverage point for sustainable transformation, as they tackle the abovementioned root causes (Abson et al., Citation2017; Fischer & Riechers, Citation2019; Meadows, Citation1999; Wamsler, Citation2020).Footnote1

Whilst calls for considering inner dimensions in climate policy and practice are increasing, a comprehensive understanding of integrative transformation processes that integrate both inner and outer dimensions is lacking (Wamsler et al., Citation2021). Addressing this gap requires a better understanding of what shapes people’s sense of agency and responsibility towards the future and how it can transform into practical and political engagement across individual, collective, and system levels (Dobson, Citation2003; O’Brien, Citation2018; Wamsler et al., Citation2021). This study addresses the identified gap in current policy and practice and investigates these aspects by focusing on the voices of Swedish citizens.

More specifically, the study aims to investigate how people in Sweden perceive their everyday life, welfare, and future in a changing climate, and the implications for their sense of agency, responsibility, and political engagement, in order to understand the social and institutional prerequisites that must be in place to develop comprehensive climate policy responses. We, therefore, explore the mindsets, values, beliefs, and paradigms of different societal groups in Sweden, together with the contextual and cognitive-emotional conditions and factors that shape citizens’ sense of responsibility, and their influence and political engagement (both actual and potential). On this basis, we discuss the role of citizens in promoting transformational cultural and systems change, as well as the potential consequences of marginalizing or excluding citizens’ voices. The exploration of citizens’ roles is, in this context, aligned with the concept of ecological citizenship, which is, in turn, grounded in the principles of sustainability, responsibility, justice, and democratic participation (Dobson, Citation2003; Karatekin & Uysal, Citation2018). This exploration also considers individual choices made to generate relationships with others (close by and elsewhere), relationships with nature, and relationships with future generations (Wolf, Citation2007; Wolf et al., Citation2009). Such choices and relationships are key to integrative transformation processes (Wamsler et al., Citation2021).

Ecological citizenship is a normative theory that envisages citizenship as related to both political agency and climate action (Dobson, Citation2003). Citizens’ political agency has, so far, been limited to areas such as behavioural change, consumption choices, and voting in general elections (O’Brien, Citation2015). In this study, we seek ways to look beyond this thin repertoire of citizenship actions and aim to explore how people can become agents of change and active participants in the transformation to a post-carbon society. The outcomes of the study draw attention to the need to develop new forms of policy and citizen involvement in a changing climate, and allow us to conclude with further research needs and policy recommendations.

2. Methodology

To explore our research aim, we conducted a national survey (N = 1,237). To conduct this survey, the research team hired a market research firm (Norstat) to collect data from a web panel of people living in Sweden. The sample was representative regarding gender, age, education, and income, but not regarding urban–rural differences. The following three, interrelated themes guided the survey design, data collection, and analysis:

Values, beliefs, and paradigms: How do citizens perceive and experience climate change and its impacts? How do they perceive their own agency and responsibility, and what values, beliefs, and paradigms underlie their actions?

Agency and political engagement: What do citizens think and feel about current and proposed actions for transitioning to a fossil-free society? How do they perceive their ability to influence these actions? How and through what channels/arenas are they making their voices heard, and what are the perceived outcomes?

Transition visions and pathways: What vision for the future do people have? What aspects do they think should be given priority in future climate work? What are their attitudes towards the future, and what contextual and cognitive-emotional factors could encourage more active engagement and empower citizens to support transformation across scales?

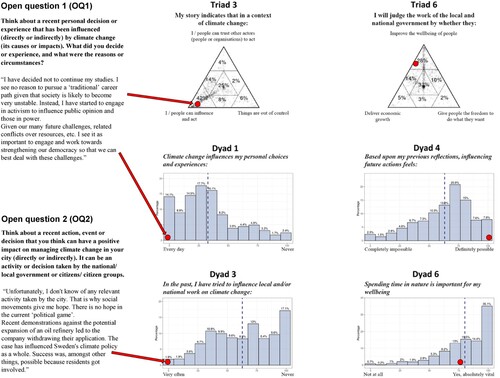

People’s perceptions regarding the three themes were collected and analysed using SenseMaker, a narrative-based methodology that includes quantitative and qualitative data collection and analyses that are facilitated by software (Camlin et al., Citation2020; Campbell-Scherer et al., Citation2021). It captures and assesses micro-narratives (i.e. personal stories) to ‘make sense’ of complex situations by identifying underlying patterns (Bruner, Citation2020; Carr, Citation1986; Snowden et al., Citation2021; Steffen, Citation1997). Sense-making can be understood as the cognitive process people use to structure the unknown, understand the world, and instruct action (Van der Merwe et al., Citation2019). This interpretative process is influenced by culture, knowledge systems, and experiences, where meaning is assigned to a phenomenon in order to inform individual and collective behaviour (Van der Merwe et al., Citation2019). How people act, in turn, shapes their social realities and future sense-making in an ongoing process (Van der Merwe et al., Citation2019). Accordingly, SenseMaker gives access to everyday forms of social knowledge (thoughts and experiences) and helps reveal elements of a grounded discourse that informs the decisions and actions that shape our realities, collectively painting a bigger picture of public opinion on a given issue (Snowden et al., Citation2021). It enriches and nuances captured thoughts and experiences (called stories), as respondents are invited to self-analyse and interpret them via triads, dyads, and multiple-choice questions (see and ).

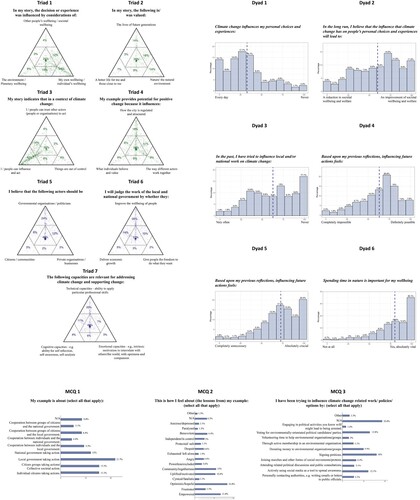

Figure 1. Overview of the questions and results of the triads (T1-7), dyads (D1-6), and multiple-choice questions (MCQ1-3).

Figure 2. Illustration of the SenseMaker methodology, which helps to capture, enrich, and nuance people's thoughts and experiences (stories), as respondents are invited to self-analyse and interpret their answers to open questions (OQ) via triads (T), dyads (D), and multiple-choice questions (MCQ).

In SenseMaker, stories are elicited via an introductory open question (OQ) or prompt that captures a micro-narrative. Triads (T) explore the higher-level meaning of the story that is told. The respondent is presented with a statement and asked to consider how it corresponds to their story’s content with respect to three dimensions. They are invited to click on the ball in the triangle and move it to the position that best reflects their perspectives. Dyads (D) test certain hypotheses or assumptions, such as what makes things better or worse, or the relative strength of a single concept, quality, belief, or outcome. The respondent is presented with a statement related to their story and asked to indicate where they sit on a sliding ‘virtue’ scale. Multiple-choice questions (MCQ) also test hypotheses or assumptions, but now the respondent is offered more options that can help to explore a range of different aspects or nuances. Altogether, the SenseMaker methodology provides the researcher with emergent patterns from qualitative and quantitative data that elucidate collectively held experiences, perceptions, beliefs, values, and paradigms.

In accordance with our research themes, our survey was divided into three parts and designed to explore three interlinked levels: the individual-behavioural, systemic (here, changes at city level), and inner dimensions (see Supplementary Material 1 for the full survey). In Part 1 of the survey, respondents were asked to share a story about a recent decision or experience that was influenced by climate change (OQ1). This was followed by three triads (T1–3) to expand their interpretation of influencing factors, notably their values, beliefs, and paradigms. The next two dyads (D1-2) aimed to contextualize and generalize patterns and relate to the general influence of climate change on choices and experiences, and their broader implications for society, social wellbeing, and welfare. Results from the second and third parts of the survey helped elucidate other underlying factors, emotions, and motivations (OQ3; D3-5-4; T5-7). Segueing to the larger systems context, in Part 2 of the survey respondents were asked to describe an important initiative that addresses climate change in their city (OQ2) and were then invited to reflect on its relevance and potential for positive change (T4), the actors involved (MCQ1), and their feelings about their example (the lessons drawn from it) (MCQ2). To contextualize identified patterns, the subsequent questions concerned the channels and general level of engagement in influencing climate-related work and policies (MCQ3; D3). In addition, results from the first and third parts of the survey helped elucidate underlying motivations, including perceived responsibilities (T5), capacities, values, and certain conditions or measures (T7; OQ3). In Part 3 of the survey, respondents were asked about their vision for the future, including their possibilities to engage and need to influence future actions (D4, D5); the personal capacities that can support change (OQ3, T7); the issues that should be prioritized in future climate policy and action (OQ4); and the basis for judging related work of local and national governments (T6). Results from the other parts of the survey also elucidated underlying patterns (D1-2, T4-5).

After quality control, including checks for technical errors, such as duplicate data, the data underwent a combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses. This involved visualizing and identifying emergent patterns, then filtering based on demographics and questions of interest. Quantitative data from triads, dyads, and multiple-choice questions were visualized and statistically analysed (comparative, correlation, and goodness-of-fit analyses). The non-parametric goodness-of-fit analyses used Pearson’s chi-square test (Agresti, Citation2013; Upton, Citation2016). Residuals were examined to test how filtered data compared to the population. Statistical analyses were conducted to ascertain correlations between respondents’ level of engagement, values, and feelings. Data from open questions were qualitatively analysed and used to identify patterns through systematic comparison and coding where, for example, stories from different corners of the triads were isolated and analysed to identify emerging themes and relate them to each other (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990; Hodder, Citation1994; Strauss, Citation1987). Qualitative and quantitative results were then compared, and linkages were explored to identify and make sense of individual and collective values, beliefs, emotions, paradigms, agency, political engagement, and future visions. See the Supplementary Material for an overview of all data visualization and analyses, and some illustrative stories and citations.

3. Results

The results are grouped under the study’s three research themes (see Section 2.1). Abbreviations indicate whether a described finding relates to a certain open question (OQ), a triad (T), a dyad (D), or a multiple-choice question (MCQ) (see ).

3.1. Values, beliefs, and paradigms

Our results reveal ways that climate change, its implications, and incentives (societal/structural) for change are perceived, internalized and, ultimately, acted upon. They illustrate people’s everyday-life experience and practices, and what values, beliefs, and paradigms influence them. Four key patterns emerged and are explained in this subsection:

Most citizens describe how climate change issues are to some extent embedded into their everyday decisions, activities, and routines.

Their actions often reflect dominant social paradigms and associated structures (thus reproducing rather than transforming them).

Actions are guided by people’s values, emotions, and what they perceive that they, as individuals, can do and control.

There is overwhelming consensus that more measures to address climate change improve, rather than reduce, wellbeing and societal welfare.

Environmental issues, and climate change in particular, influence most people’s day-to-day experience and decisions to some extent (OQ1, D1). Analysing the 1,237 collected stories revealed that nearly all respondents consciously engage in activities that contribute to mitigating or adapting to climate change, with varying levels of impact, motivation, and commitment (OQ1). The qualitative analysis shows that even though participants were asked about decisions or experiences and not specifically about actions, the latter featured in almost all responses. Most activities relate to mitigation, particularly issues of mobility, waste management, and food (OQ1).

The described behaviours and changes are embedded in daily routines, such as sorting garbage, consuming more sustainably (e.g. switching to a more plant-based diet or choosing renewable energy), or commuting via bike or public transport instead of driving (OQ1). Many of these activities reproduce dominant social paradigms. In other words, they do not necessarily challenge broader systems and structures and associated paradigms (such as consumption, materialism, economic growth). Instead, they maintain them, by greening commonplace choices. Examples are continuing to generate the same amount of trash (but now sorting it) or maintaining the consumption and growth paradigm (whilst buying organic food and/or not using plastic bags).

Some people, however, make more drastic shifts. They actively prepare for a world altered by climate change, or consciously break with dominant social paradigms and associated systems (). Examples range from moving to places and contexts that support more sustainable lifestyles, becoming self-sufficient, or changing careers (e.g. leaving higher education or a job to work in the domain of climate action or pursue climate activism) (OQ1). The results also show that political and collective engagement and events at global, national, and local levels can cause respondents to question paradigms. Several reflections related to current events (such as Joe Biden winning the United States’ election, and developments in the COVID-19 pandemic), and associated changes regarding people’s sense of interconnectedness, agency, and action-taking.

The results show that although day-to-day experience and decisions are often based on the simultaneous consideration of individual, societal, and environmental aspects, most weight is given to the environment (T1, T2); 82% of respondents stated that they are to some extent affected by considerations of environmental wellbeing (T1), either alone or in combination with other aspects (individual and societal). This tallies with answers about what respondents value (T2). Nature and intergenerational equity are valued most highly (either as individual factors or in combination), whereas more individualistic short-term perspectives accounted for only 7% of answers (T2). The coherence between responses is particularly striking in the case of more individualistic perspectives; respondents who value individual wellbeing highly (T2) also consider wellbeing more in their decision-making (T1, accounting for 62% of answers, compared to 9% in the overall sample; see Supplementary Material 9.1).Footnote2

Respondents whose stories reflect a more individualistic orientation (T2) also show lesser propensity to attempt to influence public (e.g. municipal) climate-change initiatives (D3) and to express a view that influence is less possible (D4) and less important (D5). Conversely, those that value intergenerational equity (T2) also display increased political engagement (D3). In addition, the results show that the values the respondents ascribe to their stories (OQ1, T2) are associated with the importance they give to influencing future actions (D5). Respondents expressing the belief that influencing future action feels absolutely crucial (D5) also highly value the natural environment and the lives of future generations (T2) (see Supplementary Material 9.5).Footnote3

Our results also demonstrate that in the context of climate change, many citizens feel they, and others like them, can personally exert influence and take action (T3; 42%), which seems to relate to a wish to control what is possible and to some extent counteract a lack of engagement with or trust in others (people and organizations (T3-4, OQ1)). This was confirmed in the other two parts of the survey (MCQ2, OQ2-4), where, for instance, only 3.1% of respondents felt ‘protected/safe’ in relation to climate change measures at city level (MCQ2).

Stories reflecting the belief that ‘things are out of control’ (T3) either refer to the scale of environmental impacts, or express anger about the greed and pursuit of profit that trumps any serious attempt to mitigate climate change, and hence results in people not believing in individual and collective agency. In contrast, respondents who indicated that they (or individuals in general) do have influence (T3), provide more descriptions of tangible actions that are often linked to the bigger picture regarding people’s mindsets. Examples include resisting dominant social paradigms by acquiring new knowledge (e.g. of organic farming) or nourishing inner qualities/capacities that support change, such as resisting compulsive thoughts about consumption, and increasing connectedness to nature. The importance of these individual stories and interpretations becomes even more apparent given that the great majority (79.5%) of respondents state that climate change influences their lives regularly, whereas only 2.4% state that it has no influence (D1).

Further important findings are that most respondents (64.8%) believe that the general influence of climate change on personal choices and experiences will improve (rather than reduce) societal wellbeing and welfare (D2). Whilst the specific interpretation of what improvement consists of might be very individual, the finding suggests an overall positive and even optimistic orientation, to which different meanings might be ascribed. Finally, the results also highlight significant correlations between this belief and the understanding that influencing future climate action is both important (D5) and possible (D4).Footnote4 Interestingly, this correlation is especially strong for those who expressed positive feelings in MCQ2 about the climate initiative at city level that they shared. Moreover, these respondents’ level of engagement (D3) correlates strongly with the understanding that personal influence is important (D5) (see Supplementary Material 8.1).

3.2. Agency and political engagement

The results reveal how citizens see and engage in climate actions beyond the level of individuals, and how they are making their voices heard. In addition, they highlight the issues that can encourage or hinder agency and political engagement. Again, four key patterns emerged and are elaborated on in this subsection:

Public climate actions are not very visible to the ordinary citizen and are not perceived to provide much room for their involvement and collaboration.

Citizens generally consider that most potential for positive change relates to technical capacities and how the city is regulated and structured, reflecting dominant social paradigms and associated approaches to climate change.

Consequently, there is little political engagement. This is also linked to reliance on and frustration with current democratic governance structures and mechanisms that are perceived as discouraging greater or more meaningful involvement.

Aspects that can accelerate political engagement relate to certain inner qualities/capacities (linked to aspects listed under 3.3, fourth bullet point), along with social norms in the form of shared social beliefs.

Whilst most respondents could provide examples of how climate change has impacted their day-to-day life, many had difficulty identifying relevant initiatives in their city (OQ2); around 20% could not mention any. Examples given mainly concern issues such as mobility, waste management, and food, and are in line with their previous answers about individual engagement (OQ1). Mobility dominates, where physical and technological measures are cited most frequently, such as the construction of bike lanes, the expansion of bus lines, or facilities for electric cars (OQ2). Public actors are represented most often (MCQ1; 58%). Only 27% of answers to OQ2 relate to efforts of citizens/citizen groups and local or national governments (MCQ1) to collaborate, which suggests that such efforts are somewhat rare and that actors tend to work in isolation. In addition, the descriptions of citizen group initiatives show that these efforts tend to be isolated responses to government and private sector inaction, rather than coordinated and collaborative.

There is a slight tendency for most potential for transformation to be seen in structural or regulatory solutions (T4; 18%), rather than in how actors work together (9%) or their personal norms, values, and beliefs (8%). Interestingly, the dominant emotions (MCQ2) relate to where people see potential for transformation. In stories where respondents express anger, patterns shift towards personal and relational potential (the bottom of T4); a similar trend can be seen for despair. Apparently, initiatives focusing on individual and collective change are partly an expression of frustration with governmental inaction. Conversely, stories where respondents felt protected or safe relate mainly to changes in how the city is structured and regulated (i.e. governmental interventions), and personal potential for transformation is here seen as almost non-existent (T4; see Supplementary Material 10.2).

Consistent with the emphasis on structural or regulatory solutions (T4), technical capacities (T7) were given priority in addressing climate change. While the results indicate citizens’ expectation of the need to combine technical, cognitive, and emotional capacities (49%), technical capacities are assigned greater importance (20%) than cognitive and emotional capacities (4% and 3%, respectively), especially for certain demographic groups, namely the elderly and men; the percentage increases to 44% for elderly men (see Supplementary Material 8.2.7 and 8.2.4). These results reflect current social paradigms, where climate change is seen as an external, technical challenge (see Section 1) while, concomitantly, the results indicate a generational shift in understanding. In line with the importance given to regulatory solutions and capacities, respondents tend to believe that the government should be mainly responsible for addressing climate change (T5; 24%), rather than citizens (3%) or private businesses (3%). Yet many (48%) recognize that it is a responsibility shared between public, private, and civil society actors (T5). The emphasis on governmental responsibility is linked to decision-making based on environmental considerations (T1), indicating that what underlies the assignation of responsibility to government is the understanding of democracy (see Supplementary Material 9.6).

The results also show that, in contrast to high engagement at the individual level (see Section 3.1), there were few examples of people getting engaged at the city level (OQ2, D3). Around a fifth of respondents indicate that they generally do not engage at all, and most others only selected a few of the options provided in the survey (MCQ3), with the most frequently cited being voting for environmentally oriented parties and signing petitions. On one hand, this level of passivity indicates a certain reliance on democratic structures and is related to dominant social paradigms (see above). On the other hand, it is related to a frustration with democratic structures, which are perceived as limiting further or more meaningful involvement, as can, for instance, be seen in the visions of the future (OQ3; see also Section 3.3) and emotional reactions to initiatives at the city level (MCQ2). Many respondents feel anger, despair, and frustration instead of feeling protected (MCQ2).

Aspects perceived to increase engagement relate to individual inner qualities/capacities (see Section 3.3) and collective conditions, such as social norms and paradigms. Some seem to feel they are expected to engage with current systems and structures, and they describe their own related actions (OQ1) even though they perceive personal engagement as irrelevant (D5) and/or that things are uncontrollable (T3). At the same time, climate anxiety and frustration about structural and governance constraints limit people’s agency to make more meaningful change (OQ3, OQ4). This is confirmed by the correlation analysis, which shows that respondents with positive emotions have a greater level of engagement and human–nature connectedness (see Supplementary Material 8).

3.3. Transition visions and pathways

The results provide insights for opening new pathways toward sustainability. They identify internal and external factors and conditions that can empower citizens, increasing agency and political engagement. Respondents’ perspectives and visions indicate that:

Sustainable future pathways require more space for people’s individual and collective engagement. Hence, mechanisms and structures that currently hamper personal agency and collaboration must be addressed.

Greater consideration should be given to nature, in a multi-faceted approach.

National and local authorities should give more importance to wellbeing, rather than to current (mechanistic, growth, and consumption-based) paradigms and approaches.

Personal engagement and system change can be supported by nourishing certain inner qualities/ capacities: i) self-awareness and reflexivity; ii) compassion; iii) a sense of togetherness; iv) connectedness with nature; v) hope; and vi) awareness of individual agency.

The vast majority of respondents (87%) see their agency and contribution in acting against climate change as vitally important. They believe that influencing future climate action is crucial, many seeing it as ‘absolutely crucial’ (D5), even though most only use a few of the available democratic actions (MCQ3). The results indicate that this value–action gap is related to uncertainty about individual agency and opportunities for engagement. In this context, answers to D5 show that respondents perceive that making a personal contribution is important; scores for this question are slightly higher than for D4, which investigated respondents’ perceptions of their ability to influence. This indicates that there are obstacles to engagement and supports the results presented in Section 3.2. Responses from 25% of respondents are closer to the statement that influencing future climate policy and action is ‘completely impossible’ rather than ‘definitely possible’ (D4). Related stories (OQ3-4) tend to express discontent (a belief that current initiatives, decisions, and structures are inadequate, given the global dimension of the issue); fatalism (a belief that it is impossible, or too late, to do something about the situation); and a lack of information and awareness (respondents who could not think of any relevant public decisions or initiatives, especially collaborative ones).

These results are in line with the correlation analyses, which show a clear link between the feeling that influencing future climate action is crucial (D5) and people’s actual engagement at the policy level (D3), but only for respondents who express positive emotions (MCQ2).Footnote5 This is an important insight for better communicating climate change-related issues and bridging the value–action gap to support political engagement.

Our results also show that nature is considered vital in supporting more sustainable pathways. Many respondents note that nature conservation and nature-based approaches (e.g. environmental protection and resource use) should be prioritized in the future (OQ4). Experiencing and relating to nature was one of five key factors thought to boost personal engagement (OQ3). Importantly, 91.5% of respondents also perceive that spending time in nature is vital for their wellbeing (D6). Of these, 35% place their answer at the top end of the spectrum, indicating that they consider it a key factor. The importance of nature for wellbeing is also confirmed by the statistical analysis, which shows that it correlates with the influence of climate change on people’s everyday life choices and experience (D1).

For those who expressed positive emotions (MCQ2), the importance of nature for wellbeing also correlated with the importance given to individual engagement (D5), feelings of agency (D4), and actual engagement (D3) (see Supplementary Material 8). In accordance with the importance they give to nature to enhance their wellbeing, people judge future local and national governments’ efforts to address climate change in terms of how much these improve wellbeing (28%), rather than in terms of their impact on economic growth (5%) and giving people freedom to do what they want (2%). Whilst 37% consider all three aspects as important, there was clear emphasis on wellbeing and welfare (T6). Moreover, responses emphasizing wellbeing are associated with environmentally informed decision-making (T1) and highlight a potential link between planetary and individual wellbeing.

Other aspects that respondents would like to see given more priority are: i) social and individual consumption (improved access to more environmentally-friendly options and a reduction in overall consumption); ii) more government action, even if this reduces personal comfort (lifestyle change); together with iii) greater responsibility given to non-governmental (private) actors; and iv) cooperation across scales and links between local and international democratic systems to support equitable climate policy and action (OQ4).

Importantly, whilst many people express both climate anxiety and frustration over structural constraints that limit the agency required to make more meaningful change, others appear capable of translating the urgency of climate change into positive, concrete action (OQ1, OQ2). Finding ways that support personal and political engagement is, thus, a crucial element for improving climate policy and action.

Regarding factors perceived to boost personal engagement (OQ3), the analysis shows that they include the following positive emotions: i) nature-connectedness; ii) compassion; iii) a sense of togetherness; iv) hope; and v) awareness of one’s individual agency (OQ3). This is in line with the results reported above and with the factors, values, and beliefs that were shown to influence everyday choices to take environmentally-friendly actions within current mechanisms and systems, or to make more drastic changes (OQ1, T1–3; see also Section 3.1).

Moreover, the analysis of stories that link engagement at individual and systems/policy level (OQ1) shows a high degree of self-awareness and reflexivity regarding oneself and one’s role in the world (i.e. one’s circle of identity); the link to others and nature (i.e. one’s circle of care); personal responsibility for addressing climate change (i.e. one’s circle of responsibility); and underlying emotions. Examples include reflections on personal turning points; consciously seeking engagement in different types of measures or initiatives; and a more balanced perspective on the need for change. The latter places less emphasis on technical solutions (T7). The importance of positive emotions is also supported by analyses of people’s reflections on relevant climate initiatives (OQ2; see also Section 3.1). Those who could provide examples reported positive emotions, such as hope, togetherness, empowerment, and benevolence (MCQ2). Here, positive emotions (66.4%) outweigh negative ones (26%).

Respondents who are aware of relevant collaborative initiatives (OQ2) also seem to be slightly more engaged on a personal level and vice versa (D1, D2), and are more positive about their influence at the city level (D4), which also translates into actual engagement (D3). Fewer respondents in this group say they have ‘never’ tried to influence climate change work (10% vs. 17% of the full sample). Engagement itself may thus be an important step in increasing individual agency and political engagement (actual and perceived). This observation is supported by the statistical analyses presented in the Supplementary Material (Table 8.1); the influence of climate change on personal decisions and actions (D1) correlates positively with engagement at the city level and is highly significant, with p < 0.001 (D3).

Finally, to inspire and attract the widest possible group of society, future transition pathways might need to consider certain socio-demographic differences. Younger people (and women more than men) seem to be more dispersed and less polarized in their answers, for example, with regard to how to address climate change (T7, T4). Younger people also seem to see climate change as more important in their daily activities and choices (D1) and are more convinced that their influence is absolutely crucial (D5). They also tend to be more engaged (OQ1; D3). The latter finding might be related to the fact that younger people also express slightly more optimistic feelings regarding current initiatives and the future impact of climate policies and actions on societal wellbeing and welfare (D2, MCQ2) but believe they have less possibility to influence (D4), which supports the need for improved mechanisms and structures for meaningful involvement (D4).

4. Discussion

Practitioners and researchers increasingly recognize that the approaches that are needed to address climate change and develop sustainable pathways go beyond external factors such as behavioural nudges and technological fixes (Adger et al., Citation2013; Clayton et al., Citation2015; Ives et al., Citation2020; Leichenko & O’Brien, Citation2020; O’Brien, Citation2018; Wamsler et al., Citation2021; Woiwode et al., Citation2021). Such approaches must also transform the social, cultural, economic, and political structures that maintain the systems associated with increasing climate change, risk, and vulnerability. Our findings show that these structures are, in turn, engrained in the dominant social beliefs and paradigms of all kinds of actors: individual and collective, governmental, and non-governmental.

Current climate policy approaches, however, often focus on the proximate (technical) causes of undesirable outcomes, rather than the underlying root causes that are embedded in values, beliefs, and paradigms (O’Brien & Sygna, Citation2013; Pelling, Citation2010). From within the system, these causes appear naturalized, or ‘part of the way the world is’ (Pelling, Citation2010, p. 86). When climate change, risk, and vulnerability are seen as localized issues (e.g. inadequate buildings or land use), climate policy and action will be seen as a technical challenge that can be addressed, for instance by improved housing standards, by land use change, and by other managerial strategies (O’Brien & Sygna, Citation2013; Pelling, Citation2010). However, if climate change is understood as an outcome of wider social processes that shape issues such as how people see themselves and others, their relationship with others and the environment, and their role in political processes, then related policy and action become a different challenge. With this understanding, policy and related actions instead require the active consideration of citizens and a recognition of their individual and collective beliefs, values, and paradigms. It is here that transformation can take place. Our research provides important insights to support policy decision-making and actions that takes these issues into account.

The over 1,200 stories we collected show not only how citizens perceive and act on climate change (individually, cooperatively, and by supporting others), but also the underlying internal obstacles and enablers for change. These insights, in turn, are crucial in guiding the social and institutional prerequisites and structures for developing effective, integrative responses and for moving away from the binary framing of individual action versus systems change (cf. Lucas, Citation2018; Mann, Citation2021).

Four cross-cutting patterns emerged from our analyses:

First, nearly all citizens consciously engage in daily practices that contribute to mitigating or adapting to climate change and are guided and constrained by prevailing social norms and paradigms. The practices tend to reproduce rather than transform current systems, i.e. instead of challenging unsustainable paradigms of consumption, materialism, and economic growth, they ‘green’ the choices already made (cf. Hart, Citation1997; Spaargaren & Mol, Citation2008). Nonetheless, some citizens do engage in more radical measures. As described in Section 3, multiple motives drive the decision to take routine action or to move towards more transformative change.

The second pattern shows that a range of human inner dimensions can support or hamper meaningful engagement. Negative emotions such as climate anxiety and frustration about structural and governance constraints limit people’s agency to support transformation, whereas belief in one’s own agency and positive emotions – such as hope and feelings of interconnection (e.g. compassion, community, and human–nature connection) – foster wellbeing and engagement. Moreover, engagement and transformation across individual, societal, and policy levels are supported by a high degree of awareness and reflexivity about oneself and one’s role (circle of identity); the link to others and nature (circle of care); and individual responsibility for addressing climate change (circle of responsibility). These outcomes support recent research on inner transformation, nature-based solutions, emotions, and relationality in sustainability (Hendersson & Wamsler, Citation2020; Ives et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Ojala, Citation2012; Walsh et al., Citation2021; Wamsler et al., Citation2020, Citation2021), along with expanded views of political agency that recognize each individual’s potential and capacity to contribute to transformative change (O’Brien, Citation2015, Citation2021).

The third pattern is that actual engagement can, in turn, help reduce climate anxiety and increase agency and political engagement, thus creating a virtuous cycle of transformational change and wellbeing. This is supported by a recent study which concludes that one way to overcome a feeling of being overwhelmed by the scale of the problem is the agency we feel when we actually start acting (Mann, Citation2021). It creates a snowball effect that increases engagement, which needs to be supported and channelled towards systemic change. These findings underline the importance of addressing inner human dimensions and creating better enabling environments and structures for engagement. In this context, sacrificing the comforts and predictability of more conventional lifestyles, practices, and approaches tends to be seen as temporary.

This links to the fourth key pattern or finding, that increased individual and public climate action is mostly perceived as leading to improved (rather than reduced) wellbeing and welfare. However, political engagement is lacking, as revealed by a general lack of trust in democratic governance and structures, plus the associated constraints arising from the fact that public measures offer little scope for engagement and fail to prioritize initiatives that might support people in developing the capacity necessary to address root causes and support transformation. This is both a symptom and consequence of a widespread paradigm and tendency for climate measures to marginalize citizens and exclude their voices (O’Brien, Citation2021).

5. Conclusions

Our study shows how individual and collective values, beliefs, and paradigms are expressed through narratives and everyday social practices that, in turn, inform individual and collective agency and action to support transformation. They shape the realm of perceived possibilities and alternatives, and thus have material consequences. They influence our understanding of climate change and its impacts, which, in turn, shapes our priorities and responses (see also Bentz et al., Citation2022; Clayton et al., Citation2015; Lorenzoni & Hulme, Citation2009; Schuman et al., Citation2018; Scoville-Simonds, Citation2018; Veland et al., Citation2018).

Hence, our results shed light on the individual, collective, and structural capacities that must be supported to sustainably address climate change, thus highlighting the need for new forms of policy and citizen involvement in climate action. Based on our results, we have identified six policy recommendations and associated further research needs.

1. Supporting more integrative approaches through targeted governmental support. More explicit consideration must be given to human inner dimensions of climate change and underlying social paradigms, rather than to the predominant external, technological, and information-based approaches. Extending and expanding current policy approaches and structures is not enough. Targeted policy support, investment, and measures are required.

2. Public and private policies and structures. Targeted support and investment are required in order to systematically mainstream/integrate the consideration of inner human dimensions across all sector work. Such policy integration entails revising organizations’ vision statements, communicationsFootnote6 and project management tools, working structures, regulations, human and financial resource allocation, and collaboration. The latter includes creating communities of practice and platforms that can strengthen links between individual, collective, and public climate efforts. In this context, future research should explore the role of trust between different actors in climate policy integration and governance (see also Marion Suiseeya et al., Citation2021; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Vogler, Citation2010; Whyte & Crease, Citation2010).

3. Education and training. Increased policy attention and measures are also needed to support learning environments and methods that nourish inner qualities/capacities to help people discover internalized cultural patterns and increase their sense of interconnection and the power of their agency. Related climate leadership training, public and higher education, and school curricula must ensure that citizens of all ages can cope with the emotional toll of climate change and engage adequately.

4. International policy frameworks. In light of point 3, investment and research are needed for monitoring and evaluation, to assess how the identified human inner qualities/capacities and leverage points described in Section 3 relate to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and how to best direct limited international, national, and local resources to consider these in organizations, professional groups, and society at large.

5. Nature-based solutions and planning. In addition, support for nature-based solutions and the human–nature connection need to be given greater weight by policymakers and planners. Nature-based solutions address both climate change mitigation and adaptation and have the potential to increase human–nature connection, subjective wellbeing, and personal and political engagement. Further research is needed to analyse these relationships and link the issue of human inner dimensions to the growing literature, discourse, and policies related to nature-based solutions (BMU, Citation2021; EEA, Citation2021; Woroniecki et al., Citation2020).

6. Polarization and climate anxiety. Given our findings and the limitations of our study, further investment is needed to explore the identified key aspects of agency and engagement in different contexts and the factors that might influence them. This also includes issues of political orientation and polarization, urban–rural differences, and the complex interlinkages of emotions, particularly climate anxiety, worry, and grief, along with their associated social impacts (see also Driscoll, Citation2019; Mayer & Smith, Citation2019; Ojala et al., Citation2021; Poortinga et al., Citation2019). Regarding the latter, our findings indicate that it is crucial to improve policy and communication to support human potential, positive engagement (individual and collective), and universal values rather than polarization, climate anxiety, or denial.

We conclude by calling for more attention to be given to individual and collective values, beliefs, and associated inner qualities/capacities as expressed through narratives, everyday routines, and their social and material consequences. Such issues must be taken seriously in climate policy, research, and practice if we are to support transformation and connect climate action to a broader conversation about fundamental issues such as justice, consumption, materialism, and economic growth.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (9 MB)Acknowledgements

This research was supported by two projects funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas: i) Mind4Change (grant number 2019-00390; full title: Agents of Change: Mind, Cognitive Bias and Decision-Making in a Context of Social and Climate Change), and ii) TransVision (grant number 2019-01969; full title: Transition Visions: Coupling Society, Well-being and Energy Systems for Transitioning to a Fossil-free Society). We thank the projects’ advisory board members and colleagues who provided insights and expertise that supported our administrative, managerial and scientific work with the SenseMaker research methodology and online tool. We are particularly grateful to Anne Caspari (EZC Partners) and Prof. Karen O’Brien (University of Oslo).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The classification into inner and outer, which marks the boundary between what is ‘inside’ (a subject) and what is ‘outside’ (a subject), is artificial and applied for simplicity. Inner dimensions are actually inter-subjective (e.g. socially defined) and qualities/capacities are enacted (e.g. cultivated and expressed in relationship to other subjects and the world at large).

2 The squared residual of the Pearson's Chi-Squared test for this association is 274.35 (p = 0.0000), with a count above 4 indicating a value significantly different from random chance.

3 The squared residual of the Pearson's Chi-Squared test for this association is 17.37 (p = 0.0000), with a count above 4 indicating a value significantly different from random chance.

4 The correlation between D4 and D5 is positive. It is especially prominent for stories associated with positive feelings (r2 = 25.9%) and highly significant: p value <0.001; see Supplementary Material Table 8.1.

5 The correlation between D3 and D5 is positive and highly significant: p value <0.001; see Suppl. Material Table 8.1.

6 This involves better communication to nurture human potential and inform about i) the political agency individuals have for supporting transformation across scales, ii) their legal responsibility, and iii) what governmental and non-governmental agencies do to support transformation.

References

- Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., von Wehrden, H., Abernethy, P., Ives, C. D., Jager, N. W., & Lang, D. J. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio, 46(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

- Adger, W. N., Barnett, J., Brown, K., Marshall, N., & O’Brien, K. (2013). Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 3(2), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1666

- Agresti, A. (2013). Categorical data analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bentz, J., O’Brien, K., & Scoville-Simonds, M. (2022). Beyond “blah blah blah”: exploring the “how” of transformation. Sustainability Science, 17(2), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01123-0

- Blennow, K., & Persson, J. (2009). Climate change: Motivation for taking measure to adapt. Global Environmental Change, 19(1), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.003

- BMU (Bundesumweltministerium). (2021). Jugend-Naturbewusstsein 2020: Bevölkerungsumfrage zu Natur und biologischer Vielfalt. bmu.de. https://www.bmu.de/publikation/jugend-naturbewusstsein-2020/.

- Bruner, J. (2020). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674029019.

- Camlin, D. A., Daffern, H., & Zeserson, K. (2020). Group singing as a resource for the development of a healthy public: A study of adult group singing. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00549-0

- Campbell-Scherer, D., Chiu, Y., Ofosu, N. N., Luig, T., Hunter, K. H., Jabbour, B., Farooq, S., Mahdi, A., Gayawira, A., Awasis, F., Olokude, F., Goa, H., Syed, H., Sillito, J., Yip, L., Belle, L., Akot, M., Nutter, M., Farhat, N., … Hama, Z. (2021). Illuminating and mitigating the evolving impacts of COVID-19 on ethnocultural communities: A participatory action mixed-methods study. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 193(31), E1203–E1212. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.210131

- Carr, D. (1986). Narrative and the real world: An argument for continuity. History and Theory, 25(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505301

- Clayton, S., Devine-Wright, P., Stern, P. C., Whitmarsh, L., Carrico, A., Steg, L., Swim, J., & Bonnes, M. (2015). Psychological research and global climate change. Nature Climate Change, 5(7), 640–646. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2622

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Dobson, A. (2003). Citizenship and the environment. OUP Oxford.

- Driscoll, D. (2019). Assessing sociodemographic predictors of climate change concern, 1994–2016. Social Science Quarterly, 100(5), 1699–1708. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12683

- EEA (European Environment Agency). (2021). Nature-based solutions should play increased role in tackling climate change. https://www.eea.europa.eu/highlights/nature-based-solutions-should-play.

- Filho, W. L., & McCrea, A. C. (eds.). (2018). Sustainability and the humanities. Springer.

- Fischer, J., & Riechers, M. (2019). A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People and Nature, 1(1), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.13

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2007). Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36(3), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Grušovnik, T. (2012). Environmental denial: Why we fail to change our environmentally damaging practices. Synthesis Philosophica, 27(1), 91–106.

- Hart, S. L. (1997). Beyond greening: Strategies for a sustainable world. Harvard Business Review, 75(1), 66–77.

- Hendersson, H., & Wamsler, C. (2020). New stories for a more conscious, sustainable society: Claiming authorship of the climate story. Climatic Change, 158(3), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02599-z

- Hodder, I. (1994). The interpretation of documents and material culture. In J. Goodwin (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 393–402). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Hulme, M. (2009). Why we disagree about climate change: Understanding controversy, inaction and opportunity. Cambridge University Press.

- Hunecke, M. (2018). Psychology of sustainability: Psychological resources for sustainable lifestyles. In Personal sustainability. Routledge.

- IPCC. (2022a). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.). Cambridge University Press. In Press. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg2/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FinalDraft_FullReport.pdf.

- IPCC. (2022b). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [J. Skea, P. Shukla, A. Reisinger, R. Slade, M. Pathak, A. Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, A. Abdulla, K. Akimoto, M. Babiker, Q. Bai, I. Bashmakov, C. Bataille, G. Berndes, G. Blanco, K. Blok, M. Bustamante, E. Byers, L. Cabeza, K. Calvin, C. Carraro, L. Clarke, A. Cowie, F. Creutzig, D. Korecha Dadi, D. Dasgupta, H. de Coninck, F. Denton, S. Dhakal, N. Dubash, O. Geden, M. Grubb, C. Guivarch, S. Gupta, A. Hahmann, K. Halsnaes, P. Jaramillo, K. Jiang, F. Jotzo, T. Yong Jung, S. Ribeiro, S. Khennas, Ş. Kılkış, S. Kreibiehl, V. Krey, E. Kriegler, W. Lamb, F. Lecocq, S. Lwasa, N. Mahmoud, C. Mbow, D. McCollum, J. Minx, C. Mitchell, R. Mrabet, Y. Mulugetta, G. Nabuurs, G. Nemet, P. Newman, L. Niamir, L. Nilsson, S. Nugroho, C. Okereke, S. Pachauri, A. Patt, R. Pichs-Madruga, J. Pereira, L. Rajamani, K. Riahi, J. Roy, Y. Saheb, R. Schaeffer, K. Seto, S. Some, L. Steg, F. Toth, D. Ürge-Vorsatz, D. van Vuuren, E. Verdolini, P. Vyas, Y. Wei, M. Williams, H. Winkler (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FinalDraft_FullReport.pdf.

- Ives, C. D., Abson, D. J., von Wehrden, H., Dorninger, C., Klaniecki, K., & Fischer, J. (2018). Reconnecting with nature for sustainability. Sustainability Science, 13(5), 1389–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0542-9

- Ives, C. D., Freeth, R., & Fischer, J. (2020). Inside-out sustainability: The neglect of inner worlds. Ambio, 49(1), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01187-w

- Ives, C. D., Giusti, M., Fischer, J., Abson, D. J., Klaniecki, K., Dorninger, C., Laudan, J., Barthel, S., Abernethy, P., Martín-López, B., Raymond, C. M., Kendal, D., & von Wehrden, H. (2017). Human–nature connection: A multidisciplinary review. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26-27, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.05.005

- Karatekin, K., & Uysal, C. (2018). Ecological citizenship scale development study. International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education, 8(2), 82–104. ISSN: 2146-0329.

- Köhler, J., Geels, F. W., Kern, K., Jochen, M., Onsongo, E., Wieczorek, A., Alkemade, F., Avelino, F., Bergek, A., Boons, F., Fünfschillingh, L., Hess, D., Holtz, G., Hyysalo, S., Jenkins, K., Kivimaa, P., Martiskainen, M., McMeekin, A., Mühlemeier, … Wells, P. (2019). An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004

- Leichenko, R., & O’Brien, K. (2020). Climate and society: Transforming the future. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lorenzoni, I., & Hulme, M. (2009). Believing is seeing: Laypeople’s views of future socio-economic and climate change in England and in Italy. Public Understanding of Science, 18(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662508089540

- Lucas, C. H. (2018). Concerning values: What underlies public polarisation about climate change? Geographical Research, 56(3), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12284

- Mann, M. E. (2021). The new climate war: The fight to take back our planet. Hachette.

- Marion Suiseeya, K. R., Elhard, D. K., & Paul, C. J. (2021). Toward a relational approach in global climate governance: Exploring the role of trust. WIRES Climate Change, 12(4), e712. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.712

- Mayer, A., & Smith, E. K. (2019). Unstoppable climate change? The influence of fatalistic beliefs about climate change on behavioural change and willingness to pay cross-nationally. Climate Policy, 19(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1532872

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model Of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. doi:10.2307/258792

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. The Sustainability Institute.

- O’Brien, K. (2015). Political agency: The key to tackling climate change. Science, 350(6265), 1170–1171. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad0267

- O’Brien, K. (2018). Is the 1.5°C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 31, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.04.010

- O’Brien, K. (2021). You matter more than you think: Quantum social change for a thriving world. Change Press.

- O’Brien, K., & Sygna, L. (2013). Responding to climate change: The three spheres of transformation. Proceedings of the Conference Transformation in a Changing Climate, 16–23.

- Ojala, M. (2012). Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environmental Education Research, 18(5), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.637157

- Ojala, M., Cunsolo, A., Ogunbode, C. A., & Middleton, J. (2021). Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: A narrative review. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716

- Pelling, M. (2010). Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Adaptation-to-Climate-Change-From-Resilience-to-Transformation/Pelling/p/book/9780415477512.

- Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., Steg, L., Böhm, G., & Fisher, S. (2019). Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Global Environmental Change, 55, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.01.007

- Rimanoczy, I. (2014). A matter of being: Developing sustainability-minded leaders. Journal of Management for Global Sustainability, 2(1), 95–122. doi:10.13185/JM2014.02105

- Schuman, S., Dokken, J.-V., Van, N. D., & Loubser, R. A. (2018). Religious beliefs and climate change adaptation: A study of three rural South African communities. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v10i1.509

- Scoville-Simonds, M. (2018). Climate, the earth, and God – entangled narratives of cultural and climatic change in the Peruvian Andes. World Development, 110, 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.012

- SEPA (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency). (2021). Allmänheten om klimatet 2021: En kvantitativ undersökning om den svenska allmänhetens syn på lösningar för klimatet. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

- SEPA (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency). (2022). Konsumtionsbaserade växthusgasutsläpp per person och år. https://www.naturvardsverket.se/data-och-statistik/konsumtion/vaxthusgaser-konsumtionsbaserade-utslapp-per-person.

- Snowden, D., Greenberg, R., & Bertsch, B. (2021). Cynefin: Weaving sense-making into the fabric of our world.

- Spaargaren, G., & Mol, A. P. J. (2008). Greening global consumption: Redefining politics and authority. Global Environmental Change, 18(3), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.04.010

- Steffen, V. (1997). Life stories and shared experience. Social Science & Medicine, 45(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00319-X

- Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

- UNFCCC. (2020a). Conference of the Parties (COP) (2020). https://unfccc.int/process/bodies/supreme-bodies/conference-of-the-parties-cop.

- UNFCCC. (2020b). Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): The Paris Agreement and NDCs. https://unfccc.int/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs.

- Upham, P., Bögel, P., & Johansen, K. (2019). Energy transitions and social psychology: A sociotechnical perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429458651.

- Upton, G. (2016). Categorical data analysis by example. John Wiley & Sons.

- Van der Merwe, S. E., Biggs, R., Preiser, R., Cunningham, C., Snowden, D. J., O’Brien, K., Jenal, M., Vosloo, M., Blignaut, S., & Goh, Z. (2019). Making sense of complexity: Using SenseMaker as a research tool. Systems, 7(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7020025

- Veland, S., Scoville-Simonds, M., Gram-Hanssen, I., Schorre, A., El Khoury, A., Nordbø, M., Lynch, A., Hochachka, G., & Bjørkan, M. (2018). Narrative matters for sustainability: The transformative role of storytelling in realizing 1.5°C futures. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 31, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.005

- Vogler, J. (2010). The institutionalisation of trust in the international climate regime. Energy Policy, 38(6), 2681–2687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.05.043

- Waddock, S. (2015). Reflections: Intellectual shamans, sensemaking, and memes in large system change. Journal of Change Management, 15(4), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2015.1031954

- Walsh, Z., Böhme, J., & Wamsler, C. (2021). Towards a relational paradigm in sustainability research, practice, andeducation. Ambio, 50(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01322-y

- Wamsler, C. (2020). Education for sustainability: Fostering a more conscious society and transformation towards sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(1), 112–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-04-2019-0152

- Wamsler, C., & Bristow, J. (2022). At the intersection of mind and climate change: Integrating inner dimensions of climate change into policymaking and practice. Climatic Change, 173(7). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03398-9

- Wamsler, C., Osberg, G., Osika, W., Hendersson, H., & Mundaca, L. (2021). Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Global Environmental Change, 71, 102373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102373

- Wamsler, C., Schäpke, N., Fraude, C., Stasiak, D., Bruhn, T., Lawrence, M., Schroeder, H., & Mundaca, L. (2020). Enabling new mindsets and transformative skills for negotiating and activating climate action: Lessons from UNFCCC conferences of the parties. Environmental Science & Policy, 112, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.005

- Whyte, K. P., & Crease, R. P. (2010). Trust, expertise, and the philosophy of science. Synthese, 177(3), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-010-9786-3

- Woiwode, C., Schäpke, N., Bina, O., Veciana, S., Kunze, I., Parodi, O., Schweizer-Ries, P., & Wamsler, C. (2021). Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: Fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection. Sustainability Science, 16(3), 841–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00882-y

- Wolf, J. (2007). The ecological citizen and climate change. Democracy on the Day after Tomorrow. ECPR (European Consortium for Political Research) Joint Sessions, Helsinki.

- Wolf, J., Brown, K., & Conway, D. (2009). Ecological citizenship and climate change: Perceptions and practice. Environmental Politics, 18(4), 503–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010903007377

- Woroniecki, S., Wendo, H., Brink, E., Islar, M., Krause, T., Vargas, A.-M., & Mahmoud, Y. (2020). Nature unsettled: How knowledge and power shape ‘nature-based’ approaches to societal challenges. Global Environmental Change, 65, 102132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102132

- WWF. (2016). Living planet report 2016—risk and resilience in a new era. WWF International. https://c402277.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/publications/964/files/original/lpr_living_planet_report_2016.pdf?1477582118&_ga=1.148678772.2122160181.1464121326.

- WWF. (2020). Living planet report 2020—bending the curve of biodiversity loss. WWF International. https://f.hubspotusercontent20.net/hubfs/4783129/LPR/PDFs/ENGLISH-FULL.pdf.