ABSTRACT

While climate change has been a public policy issue for decades, central banks have only recently considered it relevant to their objectives. Beginning in 2015, the Bank of England (BoE) was among the first movers to do so. This article illustrates how two institutional features were key in enabling this response. First, the macroprudential framework that developed in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has provided the key ideas that central bankers have used to understand climate change in relation to their objectives. Additionally, government support for BoE action on climate change was also essential in empowering the BoE by setting a transition pathway and providing political legitimacy. The result has been BoE policies that not only seek to limit climate-related risks but also actively shift credit toward greener enterprises. However, this article argues that this has not amounted to a green paradigm shift in the BoE's institutional role, but is better understood as a thermostatic mode of policy innovation. While the BoE's hierarchy of goals have not changed, the types of policy problems relevant to those goals has shifted substantially. Finally, this article offers reflections on the scope and durability of the BoE's approach to climate change in this context. This article contributes to the literature on central banking and climate change beyond the BoE by providing a framework for understanding the possibilities and limitations of current central bank approaches to climate change.

Key policy insights

Financial policymakers face uncertainty about which policies lie within the bounds of their institutional roles and norms as the causes of climate change become increasingly relevant for them to address.

Central banks can function as ‘thermostats’, with relevant policy problems and instrument types changing substantially in order to maintain enduring goals like price and financial stability.

While the scope of this type of response is potentially broad, the durability of policy action will be limited in the presence of other events in the economic environment.

Governments should be explicit in setting low-carbon transition pathways for central banks to align with.

1. Introduction

In 2015, the Bank of England (BoE) emerged as one of the first movers on climate change among high-income economy central banks, beginning with a speech from then-BoE Governor Mark Carney. While some central banks, for example in Brazil and China, had already begun to address environmental concerns with policy (Dikau & Volz, Citation2021), Carney's speech remains notable for raising the profile of climate change as a financial risk. ‘Climate change will threaten financial resilience and longer-term prosperity,’ Carney concluded, ‘While there is still time to act, the window of opportunity is finite and shrinking’ (Carney, Citation2015, p. 16). In addition to its participation in international initiatives, the BoE has pursued climate-oriented supervisory expectations, stress testing, and greening its corporate bond purchases, ahead of many counterparts (see Table A1 in the Supplementary Material for a list of initiatives).

Central banks previously had a narrower view of what policy problems and tools lay within their remits. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and then Covid-19 saw extraordinary involvement by many central banks in their economies, as they moved from a narrow focus on managing interest rates and inflation to wide-ranging intervention in bond and loan markets to support economic growth (Eichengreen et al., Citation2011; Goodhart et al., Citation2014; Tooze, Citation2021). More recently, a literature has developed examining how central banks can use their policy tools to address climate change, from risk-based supervisory instruments to green monetary policy (e.g. Boneva et al., Citation2022; Hidalgo-Oñate et al., Citation2023; Svartzman et al., Citation2021). How, in the midst of these changes, did the BoE come to see climate change as policy problem it should address? In what ways has this novel attention departed or remained consistent with the way that the BoE has approached its work in the years following the GFC? And what can this tell us about the scope and durability of the BoE's climate-related policy going forward?

This paper presents two key factors underpinning the BoE's approach to climate change. First, the macroprudential ideational frame that emerged following the GFC allowed climate change to be specified as relevant to the BoE's mandate as a non-financial source of systemic risk, requiring both prudential action to contain that risk but also permitting promotional policies that prevent the sources of climate risk from escalating. Second, in the presence of support from the UK government, BoE policies have in recent years expanded beyond the prudential to the monetary as well. There are two mechanisms by which this support translated to the BoE: (1) government legislation providing a transition pathway, and (2) the BoE's secondary mandate providing political legitimacy. Importantly, these factors enabled the BoE to pursue policies with both prudential and promotional aims on climate change, terms that will be used throughout this paper, as defined in below.

Table 1. Types of climate-related policy aims, based on work by Baer et al. (Citation2021) and Dafermos (Citation2021).

This amounts to a thermostatic mode of policy innovation (Cashore & Howlett, Citation2007), whereby the BoE's hierarchy of goals has not changed, but the types of policies and policy problems relevant to the pursuit of those goals have substantially changed. Acting as a thermostat, if metrics related to the BoE's institutional purpose are ‘tripped’ because of an exogenous shock like climate change, then significant innovation in policy instruments and their settings follows to maintain the institution's existing goals. The scope for policy innovation in the face of climate change is potentially broad within this existing set of goals compared to normal modes of policymaking, from a programme of greening corporate asset purchases beginning in 2021 to contemporary proposals for greening collateral frameworks. However, the durability of such innovation is subjected to other events in the economic environment, in contrast to a transformation of institutional priorities in line with a vision of a green paradigm shift that advocates have pressed for (Kedward et al., Citation2022) and critics have cautioned against (Binham & Crow, Citation2018; The Economist, Citation2019). This article expands upon the literature on central banking and climate change more broadly by providing a framework for understanding the possibilities and limitations of current central bank approaches to climate change. In addition, the BoE has received little focused attention in the literature for its response to climate change, making its case study particularly salient.

This article proceeds as follows. Sections 2 and 3 introduce the historical institutionalist framework and empirical methods that underpin this analysis, respectively. This article then examines the key mechanisms underpinning the BoE's approach to climate change in section 4, and in section 5 offers analysis on this thermostatic mode of policy innovation and its implications for the scope and durability of policy going forward.

2. Existing literature and analytical framework

2.1. Policy institutions in their domestic contexts

How and why did the BoE turn its attention to climate change? A small body of research has begun to address this question, primarily in the context of other central banks. Siderius (Citation2023) highlights the importance of a small group of central bankers to the emergence of climate change on the agenda of the Dutch central bank. Deyris (Citation2023), in studying the European Central Bank, additionally examines external pressures from politicians, academics, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs); Quorning (Citation2023) illustrates the importance of these actors outside of the central bank to bringing climate change to central banks’ agendas. This study extends this existing literature by focusing on the BoE and drawing inspiration from historical institutionalism to answer these ‘how and why’ questions. Institutions like central banks naturally come with a set of formal rules and informal policy norms that bound the range of action that central bankers can take in response to an issue. For central banks, this is most commonly examined in the context of institutional mandates or policy toolkits. However, in thinking about existing and potential policy responses, this understanding on its own is overly simplistic. A core insight from the historical institutionalist literature is that institutions must be understood within the broader social, political, and economic contexts within which they operate, and the ways these contexts shift over time (Steinmo, Citation1993). These contexts influence both opportunities and constraints that central bankers, as agents operating within institutions, face in responding to a new policy issue (Bell & Feng, Citation2013; Campbell, Citation2004). This impact may be ideational, influencing the interpretive process essential in central bankers’ translation of their mandates to specific policy actions (Blyth, Citation2002; Hay, Citation2002; Schmidt, Citation2008). It can also be material. For example, given that governments are responsible for legislating and overseeing central banks, a certain political context can result in more or less flexibility for central banks in responding to policy issues. This study thus examines the BoE's response to climate change through a holistic and historical lens.

2.2. Modes of institutional change

With this understanding of the BoE's policy context on climate change, section 5 discusses whether the BoE's approach to this new issue has resulted in a shift in these institutional bounds. The answer to this question matters because it has implications for the scope for policy and the durability of the BoE's approach to climate change going forward. This paper takes frameworks on institutional change from Hall (Citation1993) and Cashore and Howlett (Citation2007) as a starting point. Several authors have insightfully compared pre- and post-GFC changes in central bank roles more broadly using this framework (see Baker, Citation2013; Kay, Citation2011; van ‘t Klooster, Citation2022). Hall identifies two primary modes of policy change: cases of ‘normal policymaking’, where policy tools or their settings undergo incremental, technical adjustments; and paradigm shifts, where the hierarchy of goals that drives both policy instruments and their settings changes, accompanied by ‘radical changes in the overarching terms of policy discourse’ (p. 279). Cashore and Howlett introduce a third mode of policymaking, governed by a ‘thermostatic’ function, where significant policy innovation can occur in response to shocks in the external environment, while upholding the existing institutional paradigm, or hierarchy of goals. This framework is summarised in below.

Table 2. Modes of policymaking and change, adapted from Hall (Citation1993) and Cashore and Howlett (Citation2007).

3. Materials and methods

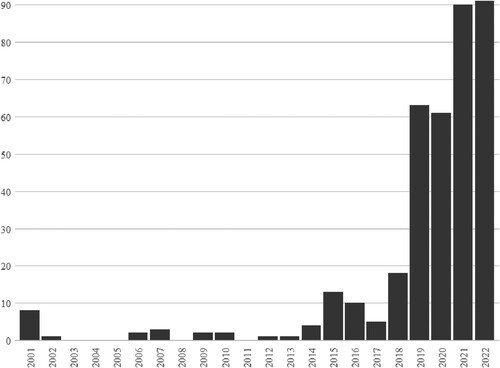

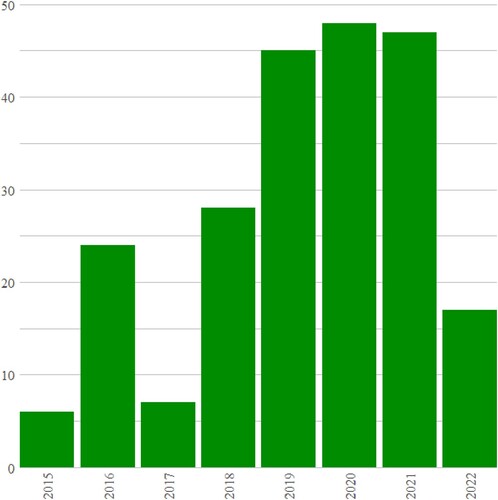

This paper is empirically underpinned by a systematic corpus of all publicly available documents and speeches by BoE officials including the search term ‘climate change’,Footnote1 which begin in 2001 and span until the end of 2022, when a final document extraction was completed. This has resulted in a corpus (n = 375) of BoE policies, reports, speeches, meeting minutes, and more that comprise an exhaustive database spanning the universe of BoE thought, policy, and operations on climate change. While many studies of central banking fruitfully utilise public communications as research material (see Dietsch et al., Citation2022; Fontan et al., Citation2016; Thiemann et al., Citation2022), these studies often focus only on central bank speeches or committee meeting minutes or may include only key policy documents about climate change. While such communications are important indicators of central banker discourse and views, the corpus included in this study is unusually extensive in its variety of documents, allowing an examination also of how climate change permeated the minutia of institutional operations and norms. shows the number of documents included in the corpus for each year.

These documents were inductively and thematically coded guided by the qualitative grounded theory methodology outlined by Corbin and Strauss (Citation2008).Footnote2 Documents were coded with the goal of understanding how the BoE related climate change to its institutional mission and bounds: codes included both how the BoE's response to climate change was framed (e.g. as a financial stability issue), and also other topics that were raised in connection with climate change (e.g. a certain government policy). These codes were then categorised, with the most prominent intermediate categories of codes displayed in Table A2 in the Supplementary Material, and the resulting themes explored in depth in section 4. Throughout the process, hypotheses related to the research questions were inductively generated, and tested and revised against remaining data using the ‘constant comparative’ method essential to grounded theory. This granular coding process was essential in uncovering the institutional logics, rules, and relationships that define the BoE's approach to climate change. While the focus of the analysis was qualitative coding, basic quantitative analysis is used in places (see ) to further illustrate findings.Footnote3

In addition to this corpus, anonymous, semi-structured interviews were conducted with five individuals including current and former BoE officials as well as experts from civil society groups who had experience with the BoE's climate policy response. These interviews lasted between 30 min and one hour and were designed to probe hypotheses generated by the document analysis and provide additional context to findings.

4. Results

4.1. Macroprudential ideas

For central bankers at the BoE to begin to examine climate change, they needed an interpretive framework that would connect it to their institutional objectives. To this end, the GFC was a key contextual precursor to the BoE addressing climate change because it broadened the Bank's mandate to include financial stability, elevating the importance of financial regulation attentive to a broader variety of system-level risks. This both provided the relevant interpretive framework under the BoE's new post-GFC macroprudential regime, and also bolstered the BoE's institutional capacity to respond to systemic risks. In this way, the GFC was a critical juncture, an event in the BoE's broader economic context that led to lasting institutional changes enabling the BoE to address climate change. Critical junctures are a key mechanism in historical institutionalist theory, defined by Capoccia and Kelemen (Citation2007, p. 343) as ‘situation(s) in which the structural (that is, economic, cultural, ideological, organizational) influences on political action are significantly relaxed for a relatively short period’; as a result, ‘the range of plausible choices open to powerful political actors expands substantially’, as does the probability these choices will have lasting change. This was key in laying the foundations to align climate change with the BoE's understanding of its objectives.

Post-GFC, central banks around the world transformed from institutions with a singular focus, attaining the optimal policy rate for managing inflation, to institutions with an added goal of financial stability and an eye for systemic risk, plus an expanded toolkit to back this up. The BoE was no exception (Eichengreen et al., Citation2011; Goodhart, Citation2010). Prior to the GFC, systemic financial and economic risks received little attention, neither at the BoE nor at the prudential regulator of that time, the Financial Services Authority (FSA). Prior to 2008, systemic issues were ‘barely’ mentioned in the FSA's annual reports (Ferran, Citation2011). With the 2009 Banking Act, the BoE was empowered to pursue financial stability as well as price stability (Hodson & Mabbett, Citation2009). Soon after, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) was created as an arm of the BoE, replacing the FSA and consolidating oversight of the financial system under the BoE (Bank of England, Citation2018a). Additionally, the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) was created within the BoE to manage sources of systemic risk (Hungin & James, Citation2019). These changes were accompanied by increased institutional capacity: the BoE went from 1900 staff in 2009 to 3600 in 2014 (Bell & Hindmoor, Citation2017).

In addition to these institutional changes, the ideational purview of central banking at the BoE had fundamentally changed, with the idea of macroprudential regulation emerging as a core interpretive frame in the pursuit of financial stability (Bank of England, Citation2009b; Haldane, Citation2009, Citation2013, Citation2017; Tucker, Citation2009). This frame undermined the prior-held efficient market hypothesis, elevated the importance of systemic risks and distortions, increased the power of public bodies to intervene in financial markets and to do so pre-emptively, and in some contexts permitted a consideration of the impacts of damaging financial activities on social outcomes (Baker, Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2018; Baker & Widmaier, Citation2014; Haldane, Citation2012). Importantly, the PRA's supervisory approach shifted from ‘tick-box compliance’ to one that is ‘judgement-based, forward-looking, and risk-based’ (HM Treasury, Citation2010). This new approach endeavoured to empower regulators to ‘make judgements about the risks that firms’ activities pose to themselves and to the wider financial system as a whole’ and allow for ‘business models can be challenged, risks identified and action taken to preserve stability’ (HM Treasury, Citation2010, pp. 4–5).

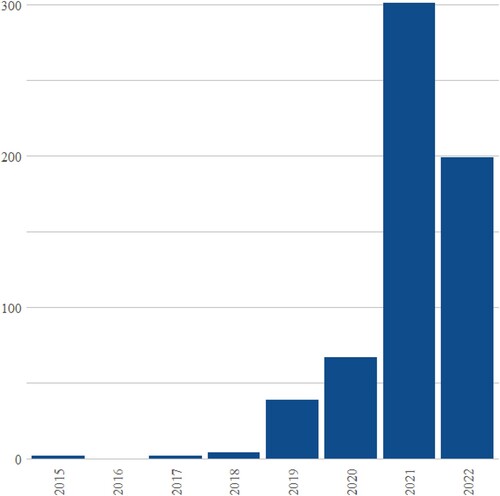

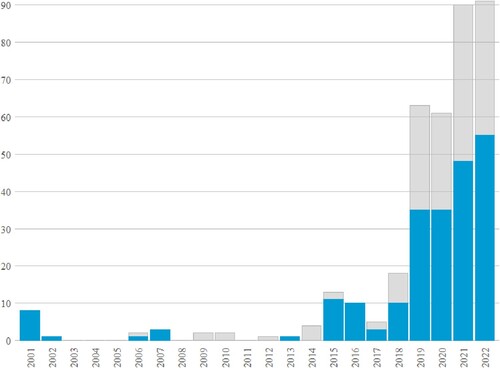

This newfound mandate for systemic risk and financial stability provided the primary basis upon which the BoE made sense of the intersection of climate change and its objectives. This was clear from Carney's initial 2015 speech, when he introduced a framework created by BoE staff for understanding how climate change transmits risks to the financial system via physical and transition channels, which continues to be used widely. This framework is anchored in the idea that climate change is a risk to financial stability: physical risks are the result of the impacts of climate change, for example losses as a result of weather-related events, while transition risks are the result of the shift to a lower-carbon economy, for example a large-scale revaluation of assets. In this speech and BoE publications that followed, the danger of a ‘climate Minsky moment’Footnote4 whereby a sudden repricing of carbon-intensive assets could have systemic effects, was touted as a reason for the importance of an orderly transition (Bank of England, Citation2018c; Breeden, Citation2021; Carney, Citation2015, Citation2019). While a bottom-up microprudential logic would look for climate risks only on the balance sheets of individual financial institutions, a top-down macroprudential logic instead opened the basis for observing climate change as a systemic risk to the financial system warranting precautionary attention. The importance of this framework, especially in the BoE's initial approach in the several years following 2015, was demonstrated in the corpus, as in and .

Figure 3. Number of documents in corpus containing ‘financial stability’. Grey area is total corpus; blue area is ‘financial stability’ documents.

Importantly, this post-GFC framework opened the space ideationally for the BoE to pursue policies with either prudential or promotional goals as early as 2017, both justified within the realm of maintaining financial stability and the need to support an orderly transition, another widely used term in the corpus. In 2017, the BoE introduced a two-pronged strategy for responding to climate change. The first prong specified ‘promoting safety and soundness by enhancing the PRA's approach to supervising the financial risks from climate change’. This is targeted specifically at managing both micro- and macroprudential risks via tools like stress testing. The second specified ‘enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system by supporting an orderly market transition to a low-carbon economy’ (Bank of England, Citation2017, Citation2018c, p. 13). This is driven by the conclusion that ‘risks to financial stability will be minimised if the transition begins early and follows a predictable path, thereby helping the market anticipate the transition to a 2°C world’ (Bank of England, Citation2017, p. 104).

Figure 4. Total number of mentions of ‘Paris’ in the corpus from 2015. Note that there were negligible references to this term in the corpus prior to 2015.

These same ideas are present in the BoE's initial policy actions related to climate change. The Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, which Carney helped to launch, was modelled on the Financial Stability Board's (FSB) Enhanced Disclosure Task Force, a post-GFC institution established to make recommendations on financial risk disclosures (Financial Stability Board, Citation2015). Similarly, in 2019 the BoE both included a climate ‘exploratory scenario’ in its general and life insurance tests and announced that the 2021 Biennial Exploratory Scenario (BES) would be on the financial risks posed by climate change, a first for a central bank (Bank of England, Citation2019b, Citation2019c, Citation2019d). The BES is a legacy of the BoE's post-GFC stress testing regime, exploring less understood risks against the resilience of the UK financial system (Bank of England, Citation2019d). Both the Climate BES as well as a supervisory statement released in 2019, another first, focused not only on risk management but also firm strategy and board-level consideration of how firm business models may need to respond to climate change, another legacy of the post-GFC approach to financial risks as outlined above (Bank of England, Citation2019a). Again, this ‘forward-looking’ approach has both prudential and promotional policy implications: BoE officials expressed hope that firms will be incentivised to ‘pull forward the transition so that they are ahead of and in control of it – directing their capital to those that are resilient and avoiding those that are not’ (Breeden, Citation2019, p. 7).

Crucially, this new post-GFC ideational framework provided a necessary but not sufficient condition for the BoE to pursue promotional policies on climate change. A framework connecting climate change to the BoE's objectives is an essential precursor for action on climate change. Yet the macroprudential ideas that have been discussed thus far generally describe the ‘global regulatory discourse’ that emerged post-GFC (Thiemann et al., Citation2018). Central bank responses to climate change, on the other hand, have been uneven in extent and nature. The section that follows reveals how policy actions by the UK government enabled the BoE to respond to climate change within this existing ideational framework.

4.2. The UK Government and the BoE's promotional turn

With an ideational and operational framework provided by the institutional changes following the GFC, a supportive political environment has been a second key context in explaining the BoE's approach to climate change. As delegated authorities, a central bank's continued legitimacy and thus independence largely rests in its perceived competence and appropriateness in the eyes of its public and government (Braun, Citation2015; van ‘t Klooster, Citation2020). There are two mechanisms by which this support translated to the BoE: (1) government legislation providing a transition pathway, and (2) the BoE's secondary mandate providing political legitimacy. This was key in enabling the BoE's initial approach to climate change and, later, the particular policies it selected.

First, government legislation was important in both catalysing the BoE's initial approach to climate change and providing the certainty of a transition pathway. The BoE's initial report on climate change was prompted by a request from the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) for the PRA to complete a Climate Change Adaptation Report (Adams, Citation2014), resulting in a 2015 paper focused on the UK insurance sector (Bank of England, Citation2015). This reporting was established as a part of the 2008 Climate Change Act, landmark legislation that set up legally binding carbon targets, for the purpose of informing the government's climate strategy (Rutter et al., Citation2012). It was this initial PRA report that established the physical and transition risk framework that Carney presented in his 2015 speech and has since been fundamental in structuring other central banks’ understanding of how climate change impacts their objectives. Throughout this period, a handful of key individuals in advocacy groups were also working to introduce the relevance of climate change to BoE officials (Quorning, Citation2023).

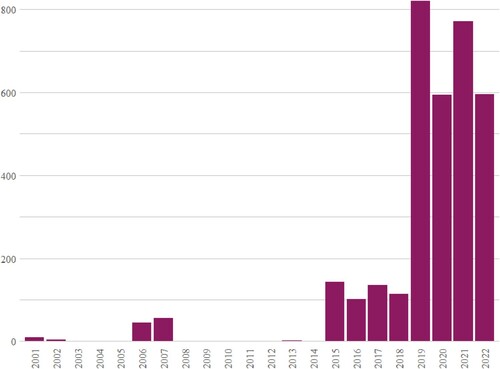

Government legislation was furthermore important in providing the certainty of a transition and thus transition risks as a channel for climate-related risk, and in releasing the BoE from choosing this transition pathway itself. The importance of these mechanisms is demonstrated in the frequent mentions to these particular government policies throughout the corpus, illustrated in and . Both the UK's ratification of the Paris Agreement in 2016 along with its 2019 law committing to a net zero transition by 2050 have been instrumental in setting a democratically endorsed transition pathway for the UK. The BoE has been able to employ the Agreement's goal of keeping warming well below 2°C as a policy marker indicating that financial flows should mobilise in line with the terms of the Agreement, or else risk a disorderly transition (Bank of England, Citation2017, Citation2018c, Citation2020; Carney, Citation2015). The entry into force of the Paris Agreement enables the UK government to advocate that it is in the financial system's best interest to act sooner to realise this transition by allocating credit away from carbon intensive industries to preclude the accumulation of systemic financial risks. Beyond the Paris Agreement, further policy certainty was solidified in 2019 with the passage of a net zero target for 2050 (UK Government, Citation2019a). Accompanying this was a Green Finance Strategy establishing the government's expectations for the roles of the UK's financial regulators in supporting the UK as a centre for green finance (UK Government, Citation2019b).

Second, the UK government has utilised the BoE's annual remit letters from the Chancellor of the Exchequer (in effect, the finance minister) to provide political legitimacy for the BoE to support this transition in the face of criticisms of ‘mission creep’ (The Economist, Citation2020). While the BoE is operationally independent from the UK government, the two are institutionally connected via the BoE's mandate. The BoE's primary mandate includes both a price stability and a financial stability objective, whilst the secondary mandate requires the BoE ‘subject to (maintaining price stability), to support the economic policy of Her Majesty's Government, including its objectives for growth and employment’ (Bank of England, Citation2018b, p. 57). These economic priorities are set out each year in the Treasury's remit letters to the Bank. In March 2020, the FPC's annual remit letter from then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak specified that the FPC should both consider the financial risks from climate change as a part of the BoE's primary objective, and that it should have regard to the government's Green Finance Strategy as a part of its secondary objective by ‘facilitating finance to support the delivery of the UK's carbon targets and clean growth’ (Sunak, Citation2020a, p. 4). This was followed in March 2021 by similar statements in the remits for the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) and the Prudential Regulation Committee. These statements are significant, because they gave the BoE the government's backing not only to consider the financial risks stemming from climate change, but also because they specifically ask the BoE to support the government in creating a greener economy. BoE officials themselves pushed for this remit change as a way to bolster the political legitimacy of this type of promotional action (Bailey, Citation2021; Carney, Citation2020).

This remit has since been employed as such, with references in the corpus from 2020 onwards. In May 2021, the BoE announced that it would be ‘greening’ its Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (CBPS) in its first policy with a primarily promotional aim, with implementation beginning in November 2021 (Bank of England, Citation2021a, Citation2021c). The CBPS is a monetary stimulus tool established in 2016 to smooth the transition out of the EU.Footnote5 Further purchases were made in March 2020 with the onset of Covid-19, with holdings reaching 20 billion GBP, 6.5% of total sterling corporate bonds. The BoE endeavoured to ‘green’ the CBPS by tilting purchases to stronger climate performers within its current sectoral composition, adapting the longstanding concept of market neutrality.Footnote6 The goal of this greening is outlined as ‘support(ing) an orderly economy-wide transition to net zero’ by ‘incentivis(ing) companies to take decisive action to achieve net zero’, consistent with the government's 2050 target (Bank of England, Citation2021c, p. 2). Notably, this was the first venture by the BoE that cited a promotional goal as the primary aim of a climate-related policy. This promotional turn was justified both by the BoE's primary and secondary mandates. First, achieving the UK's emissions reduction targets, while necessarily driven by government policy, is ‘vital if (the Bank is) to maintain monetary and financial stability – central banks’ core mission’ (Bank of England, Citation2021c, p. 1). This is ideationally consistent with earlier documents outlining the case for an ‘orderly transition’. Second, the BoE also cited an addition to its remit by the government to support the net zero transition as part of its secondary objective to support the government's economic priorities, which ‘require(d) (the BoE) to adjust to composition of CBPS (Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme) investments to support the transition to net zero’ (Bank of England, Citation2021a, p. 2).

5. Institutional change?

The BoE's market-shaping attention to climate change is a significant development, especially because high-income country central banks like the BoE have in recent history preferred to avoid issues related to the distribution of credit and concerns of political entanglement. But this begs the question of the nature of this development. Has the BoE's attention to climate change signalled a more fundamental shift in the institutional boundaries of the BoE? And what can the answers to these questions tell us about the scope and durability of BoE policy responses to climate change? This section turns to the framework introduced in to assess these questions, putting forth that the BoE's climate approach is best characterised as a ‘thermostatic’ institutional response to a significantly changed policymaking environment.

The BoE has made clear its openness to pursuing policies with promotional aims. Does this mean that we can see evidence of a green paradigm shift? According to Hall (Citation1993), a paradigm shift is defined by changes in the ‘hierarchy of goals’ that drive policymaking. Given a fundamental shift in the BoE's role we might expect to see either new goals introduced to the BoE's institutional objectives, or a realignment of the relative importance or interpretation of objectives currently present. Yet, as illustrated, the BoE's approach to climate change has largely been specified within its post-GFC approach to its objectives. As illustrated, the BoE has connected each of its policy actions on climate change to supporting its existing primary mandate for price and financial stability. While promotional policy on climate change, for example the greening of the CBPS, is enabled via the BoE's secondary mandate, green goals are still subject to the primacy of the CBPS’ monetary policy mission. Contrary to what we would expect in a green paradigm shift, in February 2022 the MPC voted to unwind the CBPS by the end of 2023 as the BoE's orientation shifts to monetary tightening, in doing so ending its green-tilted asset purchases (Bank of England, Citation2022a). In the case of a green paradigm shift, we would expect to see promotional policies aiming to direct credit to greener actors in the economy stand on their own, even when the central bank is pursuing a broader strategy of tighter financial conditions.

Similarly, the BoE's utilisation of its secondary mandate is consistent with the existing hierarchy of BoE policy goals. The attention paid to specifying the government's economic strategy in the annual remit letter to the MPC has generally increased in the years following the GFC. Prior to the GFC, this included a succinct statement on ‘achiev(ing) high and stable levels of growth and employment’. From 2013, the Chancellor has included an economic strategy that has included items such as ‘an ambitious programme of investment in skills, infrastructure and innovation in order to sustain high employment, raise productivity and improve living standards’; FPC remit statements similarly reference the importance of examining non-financial sources of systemic risk, for example Brexit, cybersecurity, and supporting the government's Covid-related economic policy (Bailey, Citation2020; Hammond, Citation2017; Osborne, Citation2015, Citation2016; Sunak, Citation2020b, p. 4). The increasing utilisation of this remit also mirrors changes in policy norms in central banks including the BoE since the GFC. While prior to the crisis central bankers shied away from anything that may have resembled credit guidance, in the years following central banks have taken a more active role in shaping markets (van ‘t Klooster, Citation2022; van ‘t Klooster & Fontan, Citation2020). The BoE has over the past decade pursued several policies that more actively influence credit allocation in the real economy, most obvious in its response to the Covid pandemic, including, for example, the 2020 Covid Corporate Financing Facility, which directly purchased commercial paper (a short-term debt instrument) from large companies (Bank of England, Citation2021b). This type of intervention is another legacy of the critical juncture that the GFC initiated at central banks.

One of Hall's insights is that ideational change is closely linked to institutional change: paradigm change is defined by ‘radical changes in the overarching terms of policy discourse’ (Hall, Citation1993, p. 279). Were there to be evidence of a more fundamental institutional shift with climate change alone, it would be expected that we would see new terms of discourse governing this approach. Yet as has been presented in this paper, the ideational framework within which the BoE specified their attention to climate change was derived from a post-GFC macroprudential frame, where both prudential and promotional approaches to climate change were primarily understood in relation to financial stability objectives rather than as a variety of green industrial policy. In this case, the BoE was able to extend its existing ideational framework to cover new topical ground. Thus evidence of a more foundational green paradigm shift, where climate-related goals may come to hold a novel position in the hierarchy of BoE institutional goals, is lacking.

Yet the scenario of ‘normal’ policymaking does not sufficiently capture the substantial innovation that has defined the BoE's approach to climate change. Under this mode of policymaking, we would expect to see climate change understood as equivalent in character to the other risks the BoE's frameworks already capture, and thus only addressed to the extent that it was accounted for in existing tools. This would likely amount to an entirely prudential approach. While this mode of policymaking involves incremental adjustments to existing policy tools based primarily on dissatisfaction with prior outcomes (Hall, Citation1993), the BoE has instead emphasised the ‘distinctive’ nature of climate change as an existential risk that requires a novel and potentially far-reaching approach, with banks not only managing risks to their balance sheets in the typical three-to-five year horizon, but more expansively planning to finance a transition to net-zero (Bank of England, Citation2018c; Carney, Citation2019). In a ‘thermostatic’ scenario, the institution's policy paradigm is not transformed by shocks like climate change, but is maintained by significant policy innovations in response (Cashore & Howlett, Citation2007; Kay, Citation2011).Footnote7 If certain metrics related to the BoE's institutional purpose are ‘tripped’ because of an exogenous shock (e.g. the risk of future disruption to market functioning due to climate change), then like a thermostat, significant innovation in policy instruments and their settings follows in order to maintain the institution's existing purpose. In this case, the BoE's ability to achieve its existing primary objectives of price and financial stability is likely to be substantially impacted by climate change. Preventing this scenario, however, requires pre-emptive action to incentivise a transition. Thus, the paradigm itself endures because of significant policy experimentation. This is exemplified in the blurring of boundaries between prudential and promotional policy aims. While the BoE has largely sought to maintain prudential policy aims to serve its mandate for price and financial stability, it has repeatedly recognised that continuing to meet these higher-level goals will require promotional interventions in the economy to ensure an ‘orderly transition’.

Delineating these varieties of institutional change matters because they have different implications for the possible scope and durability of central bank approaches to climate change, as outlined in the third and fourth rows of . While a ‘normal policymaking’ path to incorporating climate change into policy would be very durable, as a narrow, prudential-only approach focused only on incremental adjustment, the scope for policy would be limited. On the other end of this spectrum, a green paradigm shift would offer expansive scope for policy, because promotional policy objectives would not be subordinated to the BoE's primary mandate; this echoes the vision that Kedward et al. (Citation2022) present for an allocative green credit policy. While such an approach would eventually become durable, any fundamental reordering of the BoE's primary and secondary mandates would require substantial democratic deliberation and institutional transformation, and as indicated in this paper, this does not at present reflect the approach and situation currently faced by the BoE.

This is why it is important to distinguish this third, thermostatic mode of operation. In this form, the scope for policy innovation is broad, as it is understood that climate change impacts both the BoE's primary and secondary mandates in their existing forms, but in the long run presents an existential threat to more fundamental elements of the BoE's work. These policies could potentially span climate-linked capital charges (Bank of England, Citation2023; Woods, Citation2022) to targeted lending operations (see Krebel & van Lerven, Citation2022) and beyond. The key condition is that policies with promotional aims are not at the detriment of the primary mandate, and the BoE itself has made clear that an orderly transition itself is relevant to this mandate. However, given that this work has been largely specified within the BoE's post-GFC ideational framework, the character of these innovations is likely to reflect these policy norms. With the CBPS, the enduring commitment to market neutrality meant that the greening mirrored the existing sectoral composition of the market, thwarting the programme's potential climate efficacy. While the green tilting aimed to reduce the Weighted Average Carbon Intensity (WACI) of the CBPS portfolio by 25% by 2025, Dafermos et al. (Citation2022) find that this likely only achieved a 7% reduction. Furthermore, while the BoE aims to incentivize private financial actors with this programme, key decisions around the pace and direction of the transition are still left with the private sector (Kedward et al., Citation2022). In parallel, many scholars have pointed out that the reforms undertaken following the GFC did not actually constrain private financial activity in a meaningful way (Casey, Citation2015; Helleiner, Citation2014; Levingston, Citation2021), making the lessons learned around post-GFC financial regulation and its shortcomings particularly salient in the context of climate change.

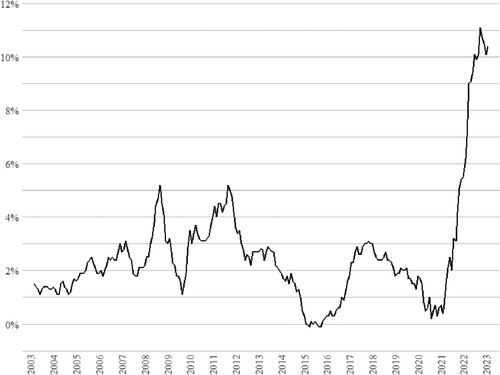

Figure 6. UK annualised inflation (CPI), data from ONS (Citation2023).

However, the durability of this type of policy response is more mixed: while prudential policies face little threats to continuity, any promotional approach to addressing climate change is subjected to other events in the policy environment. These events can either amplify or dampen the BoE's approach to climate change. As shown in the table in the supplementary material, the BoE continued to be active on climate change throughout the Covid pandemic-related crisis: its mode of expansionary monetary policy was compatible with initiatives like the greening of the CBPS. However, as inflation has surged (see ) and the BoE has changed its stance to monetary tightening, winding down the CBPS, it no longer has an active promotional policy on climate change geared explicitly toward credit allocation. Within this paradigm, any targeted climate policy with promotional aims will be difficult in the presence of balance sheet tightening. Furthermore, as the pressure mounts to get inflation under control, support for central banks to focus on issues traditionally seen as outside the bounds of their mandates is also likely to wane, constraining their space for policy innovation (see Burden, Citation2022; Sternberg, Citation2022). Opportunities for policy action on climate change will also depend on other events that the BoE responds to within its secondary mandate. In 2022, the BoE alongside the Treasury established a credit guarantee facility, the Energy Markets Financing Scheme (EMFS), to support the liquidity of energy firms amidst a period of volatility. As a condition of accessing the scheme, firms were required to disclose whether they have net zero transition plans, and provide them to the Treasury (Bank of England, Citation2022b). Given that this scheme is temporary, this lever of influence for the BoE will also cease with the expiry of the programme.

6. Conclusion

This article has illustrated how the macroprudential framework that developed in the wake of the GFC was key in providing an ideational basis for the BoE to engage with climate change with both prudential and promotional policy aims. It has illustrated how a supportive domestic political environment was a key contextual factor in empowering the BoE's leadership on climate change, with (1) government legislation providing a transition pathway, and (2) the BoE's secondary mandate providing political legitimacy. These two factors can serve as an example to other central banks' governments looking to proactively address climate change, where setting low-carbon transition pathways for central banks to align with is an important precursor to more ambitious climate-related policy.

The result of these drivers has been a ‘thermostatic’ mode of policy innovation on climate change at the BoE. This brings with it substantial potential scope for innovation within the BoE's existing institutional hierarchy, as policies with both prudential and promotional aims are justified within the BoE's existing mandates. However, the durability of this intervention will likely continue to be subject to other events in the economic environment within the existing hierarchy of goals. As demonstrated, the winding down of the CBPS as the BoE's agenda switched to monetary tightening has stymied the BoE's new promotional agenda. Furthermore, ongoing levels of inflation above central bank targets may impact the level of support for central banks to pursue other objectives, a subject deserving of more focused research in the future.

While this paper has focused on the BoE, this framework is broadly applicable to central banks that face both similar and different constraints in addressing climate change. For central banks in some developing countries that do not face the constraints of central bank independence, the concept of a green paradigm shift introduced in this paper may be more useful. However, for central banks like the BoE with more narrow mandates and strong norms around independence, the case of the BoE is instructive in the possibilities and limits of green central banking.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the four anonymous reviewers and Climate Policy editors for their helpful feedback, as well as Stephen Bell, Jérôme Deyris, Shahar Hameiri, Ryan Walter, and Wesley Widmaier.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This paper was particularly interested in how the BoE has responded to climate change, however searches for documents were conducted with alternative terms including ‘green finance’ and ‘sustainable finance’ as a robustness check, which each produced a smaller body of documents not unique to the corpus examined here.

2 Also Charmaz (Citation2014), Birks and Mills (Citation2015), Charmaz and Thornberg (Citation2021), Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998).

3 This analysis was conducted using the quanteda package in R, see Benoit et al. (Citation2018). Texts were pre-processed by converting all characters to lowercase and removing numbers, punctuation, and symbols.

4 Minsky's seminal contribution was his financial instability hypothesis, which set out how risk-taking in the financial system can endogenously lead to destabilisation, as in Minsky (Citation1986). As described by Breeden and Hauser (Citation2019) in the climate context, climate-related financial risks may lead to financial instability and a collapse in asset prices, with negative feedback loops to growth.

5 Corporate bond purchases were also used beginning in 2009 as a part of monetary stimulus during the GFC, see Bank of England (Citation2009a).

6 Market neutrality is the goal of not influencing the relative cost of borrowing across sectors.

7 It should be noted that in Cashore and Howlett’s (Citation2007) original version, this thermostatic governing mechanism occurs at the level of policy objectives, rather than institutional paradigms. Given a significant shift in the policy environment, these durable objectives lead to major changes in policy settings in order to maintain the institution itself. In Kay’s (Citation2011) version, consistent with this article, the institutional paradigm instead plays this governing role, leading to major innovation in policy instruments and their settings.

References

- Adams, J. (2014). PRA response to DEFRA on climate change adaption reporting. Bank of England Prudential Regulation Authority. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/letter/2014/pra-adaptation-reporting-letter-june-2014.pdf

- Baer, M., Campiglio, E., & Deyris, J. (2021). It takes two to dance: Institutional dynamics and climate-related financial policies. Ecological Economics, 190, article no. 107210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107210

- Bailey, A. (2020, June 25). Response to the remit for the Financial Policy Committee. Bank of England. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/letter/2020/governor-letter-250620-fpc.pdf

- Bailey, A. (2021). Letter to Philip Dunne MP, 8 February 2021. Bank of England. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/4673/documents/47073/default/

- Baker, A. (2013). The new political economy of the macroprudential ideational shift. New Political Economy, 18(1), 112–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2012.662952

- Baker, A. (2015). Varieties of economic crisis, varieties of ideational change: How and why financial regulation and macroeconomic policy differ. New Political Economy, 20(3), 342–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2014.951431

- Baker, A. (2018). Macroprudential regimes and the politics of social purpose. Review of International Political Economy, 25(3), 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1459780

- Baker, A., & Widmaier, W. (2014). The institutionalist roots of macroprudential ideas: Veblen and Galbraith on regulation, policy success and overconfidence. New Political Economy, 19(4), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2013.796447

- Bank of England. (2009a, March 19). Asset purchase facility - Corporate bond secondary market purchase scheme. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/news/2009/march/asset-purchase-facility-corporate-bond-secondary-market-purchase-scheme.pdf

- Bank of England. (2009b, November). The role of macroprudential policy. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/paper/2009/the-role-of-macroprudential-policy.pdf

- Bank of England. (2015). The impact of climate change on the UK insurance sector. Bank of England Prudential Regulatory Authority. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/publication/impact-of-climate-change-on-the-uk-insurance-sector.pdf

- Bank of England. (2017). Quarterly Bulletin: The Bank of England‘s response to climate change. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2017/the-banks-response-to-climate-change.pdf

- Bank of England. (2018a). The financial crisis – 10 years on. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/news/2018/september/the-financial-crisis-ten-years-on

- Bank of England. (2018b, June). The Bank of England Act 1998, the Charters of the Bank and related documents. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/about/legislation/boe-charter.pdf

- Bank of England. (2018c, September). Transition in thinking: The impact of climate change on the UK banking sector. Bank of England Prudential Regulatory Authority. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/report/transition-in-thinking-the-impact-of-climate-change-on-the-uk-banking-sector.pdf

- Bank of England. (2019a). Enhancing banks’ and insurers’ approaches to managing the financial risks from climate change (Supervisory Statement SS3/19). Bank of England Prudential Regulatory Authority. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudentialregulation/publication/2019/enhancing-banks-and-insurers-approaches-tomanaging-the-financial-risks-from-climate-change-ss

- Bank of England. (2019b). General Insurance Stress Test 2019: Scenario specification, guidelines and instructions. Bank of England Prudential Regulatory Authority. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/letter/2019/general-insurance-stress-test-2019-scenario-specification-guidelines-and-instructions.pdf

- Bank of England. (2019c). Life Insurance Stress Test 2019: Scenario specification, guidelines and instructions. Bank of England Prudential Regulatory Authority. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/letter/2019/life-insurance-stress-test-2019-scenario-specification-guidelines-and-instructions.pdf

- Bank of England. (2019d, December). Discussion paper: The 2021 biennial exploratory scenario on the financial risks from climate change. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/paper/2019/biennial-exploratory-scenario-climate-change-discussion-paper

- Bank of England. (2020, June). The Bank of England‘s climate-related financial disclosure 2020. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/annual-report/2020/climate-related-financial-disclosure-report-2019-20.pdf

- Bank of England. (2021a). Greening our Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (CBPS). https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/greening-the-corporate-bond-purchase-scheme

- Bank of England. (2021b). Our response to coronavirus (Covid). https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/coronavirus

- Bank of England. (2021c, May). Options for greening the Bank of England’s Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/paper/2021/options-for-greening-the-bank-of-englands-corporate-bond-purchase-scheme

- Bank of England. (2022a). Asset purchase facility: Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme sales programme – Market notice 5 May 2022. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/market-notices/2022/may/asset-purchase-facility-market-notice-5-may-2022

- Bank of England. (2022b). Joint HM Treasury and Bank of England energy markets financing scheme (EMFS) – market notice 17 October 2022. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/market-notices/2022/october/joint-hmt-boe-emfs-market-notice-17-october-2022

- Bank of England. (2023). Bank of England report on climate-related risks and the regulatory capital frameworks. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2023/report-on-climate-related-risks-and-the-regulatory-capital-frameworks

- Bell, S., & Feng, H. (2013). The rise of the People’s Bank of China. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674073593

- Bell, S., & Hindmoor, A. (2017). Structural power and the politics of bank capital regulation in the United Kingdom. Political Studies, 65(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716629479

- Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). Quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

- Binham, C., & Crow, D. (2018, December 17). Carney plans to test UK banks’ resilience to climate change. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/0ba2390a-ffd4-11e8-ac00-57a2a826423e

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Blyth, M. (2002). Great transformations: Economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Boneva, L., Ferrucci, G., & Mongelli, F. P. (2022). Climate change and central banks: What role for monetary policy? Climate Policy, 22(6), 770–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2070119

- Braun, B. (2015). Preparedness, crisis management and policy change: The Euro area at the critical juncture of 2008–2013. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 17(3), 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12026

- Breeden, S. (2019). Avoiding the storm: Climate change and the financial system. Official Monetary & Financial Institutions Forum. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2019/sarah-breeden-omfif

- Breeden, S. (2021, May 18). Climate change – Plotting our course to net zero. University of Edinburgh and Environmental Association for Universities and Colleges Webinar. https://www.bis.org/review/r210519b.pdf

- Breeden, S., & Hauser, A. (2019). A climate Minsky moment. In D. Kyriakopoulou (Ed.), Global public investor 2019 (pp. 141). Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum.

- Burden, L. (2022, May 16). Political attacks on BOE risk making inflation worse, citi warns. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-16/political-attacks-on-boe-risk-making-inflation-worse-citi-warns

- Campbell, J. L. (2004). Institutional change and globalization. Princeton University Press.

- Capoccia, G., & Kelemen, R. D. (2007). The study of critical junctures: Theory, narrative, and counterfactuals in historical institutionalism. World Politics, 59(3), 341–369. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100020852

- Carney, M. (2015). Breaking the tragedy of the horizon - Climate change and financial stability (Lloyd's of London). Bank of England. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2015/breaking-the-tragedy-of-the-horizon-climate-change-and-financial-stability

- Carney, M. (2019, March 21). A new horizon. Bank of England. European Commission Conference: A global approach to sustainable finance. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2019/mark-carney-speech-at-european-commission-high-level-conference-brussels

- Carney, M. (2020, February 27). Letter from Governor Mark Carney to Mel Stride MP. Bank of England. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmtreasy/correspondence/Mark-Carney-BoE-to-Chair-270220.pdf

- Casey, T. (2015). How macroprudential financial regulation can save neoliberalism. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 17(2), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12042

- Cashore, B., & Howlett, M. (2007). Punctuating which equilibrium? Understanding thermostatic policy dynamics in pacific northwest forestry. American Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 532–551. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00266.x

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Charmaz, K., & Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Dafermos, Y. (2021, September). Climate change, central banking and financial supervision: Beyond the risk exposure approach (SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper No. 243). SOAS University of London. https://www.soas.ac.uk/economics/research/workingpapers/file155297.pdf

- Dafermos, Y., Gabor, D., Nikolaidi, M., & van Lerven, F. (2022, January). An environmental mandate, now what? SOAS University of London; University of Greenwich; University of the West of England. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/36190/1/Dafermos%20et%20al%20%282022%29%20An%20environmental%20mandate.pdf

- Deyris, J. (2023). Too green to be true? Forging a climate consensus at the European Central Bank. New Political Economy, 1–18. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2022.2162869

- Dietsch, P., Fontan, C., Dion, J., & Claveau, F. (2022). Green central banking. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/ymre2

- Dikau, S., & Volz, U. (2021). Central bank mandates, sustainability objectives and the promotion of green finance. Ecological Economics, 184, 107022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107022

- Eichengreen, B., El-Erian, M., Fraga, A., Ito, T., Pisani-Ferry, J., Prasad, E., Rajan, R., Ramos, M., Reinhart, C., Rey, H., Rodrik, D., Rogoff, K., Shin, H. S., Velasco, A., Di Weder Mauro, B., & Yu, Y. (2011). Rethinking central banking. Committee on International Economic Policy and Reform. https://www.brookings.edu/research/rethinking-central-banking/

- Ferran, E. (2011). The break-up of the financial services authority. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 31(3), 455–480. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqr006

- Financial Stability Board. (2015, December 4). FSB to establish Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures [Press release]. https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2015/12/12-4-2015-Climate-change-task-force-press-release.pdf

- Fontan, C., Claveau, F., & Dietsch, P. (2016). Central banking and inequalities. Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 15(4), 319–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X16651056

- Goodhart, C. (2010). The changing role of central banks (BIS Working Papers No. 326). Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/work326.pdf

- Goodhart, C., Gabor, D., Vestergaard, J., & Ertürk, I. (Eds.). (2014). Central banking at a crossroads: Europe and beyond. Anthem Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1gxpd6m

- Haldane, A. G. (2009, May 8). Small lessons from a big crisis. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Reforming Financial Regulation, Chicago. https://www.bis.org/review/r090710e.pdf

- Haldane, A. G. (2012, October 29). A leaf being turned. Occupy Economics. Socially useful banking, London. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2012/a-leaf-being-turned

- Haldane, A. G. (2013, April 16). Macroprudential policies - When and how to use them. International Monetary Fund. Rethinking Macro Policy II: First Steps and Early Lessons. https://www.imf.org/external/np/seminars/eng/2013/macro2/pdf/ah.pdf

- Haldane, A. G. (2017, October 12). Rethinking financial stability. Peterson Institute for International Economics. Rethinking Macro Policy IV. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2017/rethinking-financial-stability

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

- Hammond, P. (2017, March 8). Remit and recommendations for the Financial Policy Committee. HM Treasury. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/remit-and-recommendations-for-the-financial-policy-committee-spring-budget-2017

- Hay, C. (2002). Political analysis. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Helleiner, E. (2014). The status quo crisis: Global financial governance after the 2008 financial meltdown. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199973637.001.0001

- Hidalgo-Oñate, D., Fuertes-Fuertes, I., & Cabedo, J. D. (2023). Climate-related prudential regulation tools in the context of sustainable and responsible investment: A systematic review. Climate Policy, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2179587

- HM Treasury. (2010, July). A new approach to financial regulation: Judgement, focus and stability. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/81389/consult_financial_regulation_condoc.pdf

- Hodson, D., & Mabbett, D. (2009). UK economic policy and the global financial crisis: Paradigm lost? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47(5), 1041–1061. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2009.02034.x

- Hungin, H., & James, S. (2019). Central bank reform and the politics of blame avoidance in the UK. New Political Economy, 24(3), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1446924

- Kay, A. (2011). UK monetary policy change during the financial crisis: Paradigms, spillovers, and goal co-ordination. Journal of Public Policy, 31(2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41302613.pdf

- Kedward, K., Gabor, D., & Ryan-Collins, J. (2022). Aligning finance with the green transition: From a risk-based to an allocative green credit policy regime (Working Paper No. 11). UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4198146

- Krebel, L., & van Lerven, F. (2022). Green credit guidance: A green term funding scheme for a cooler future. New Economics Foundation. https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/NEF_GCG.pdf

- Levingston, O. (2021). Minsky’s moment? The rise of depoliticised Keynesianism and ideational change at the Federal Reserve after the financial crisis of 2007/08. Review of International Political Economy, 28(6), 1459–1486. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1772848

- Minsky, H. (1986). Stabilizing an unstable economy. Yale University Press.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2023). GDP - Data tables. Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/datasets/uksecondestimateofgdpdatatables

- Osborne, G. (2015, March 18). Remit and recommendations for the Financial Policy Committee. HM Treasury. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/remit-and-recommendations-for-the-financial-policy-committee-budget-2015

- Osborne, G. (2016, March 16). Remit and recommendations for the Financial Policy Committee. HM Treasury. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/remit-and-recommendations-for-the-financial-policy-committee-budget-2016

- Quorning, S. (2023). The ‘climate shift’ in central banks: How field arbitrageurs paved the way for climate stress testing. Review of International Political Economy, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2171470

- Rutter, J., Marshall, E., & Sims, S. (2012). The “S” factors: Lessons from IFG’s policy success reunions. Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/The%20S%20Factors.pdf

- Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 303–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

- Siderius, K. (2023). An unexpected climate activist: Central banks and the politics of the climate-neutral economy. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(8), 1588–1608. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2093948

- Steinmo, S. (1993). Taxation and democracy: Swedish, British, and American approaches to financing the modern state. Yale University Press.

- Sternberg, J. C. (2022, September 8). The coming global crisis of climate policy. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-coming-global-crisis-of-climate-policy-europe-germany-energy-prices-bankruptcy-winter-subsidies-borrowing-green-nuclear-11662651070

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Sunak, R. (2020a, March 11). Remit and recommendations for the Financial Policy Committee. HM Treasury. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/letter/2020/chancellor-letter-11032020-fpc.pdf?la=en&hash=29B4977F925DDF52FF9F4DB627F94B475C01F0C1

- Sunak, R. (2020b, March 11). Remit for the Monetary Policy Committee. HM Treasury. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/letter/2020/chancellor-letter-11032020-mpc.pdf

- Svartzman, R., Bolton, P., Despres, M., Da Pereira Silva, L. A., & Samama, F. (2021). Central banks, financial stability and policy coordination in the age of climate uncertainty: A three-layered analytical and operational framework. Climate Policy, 21(4), 563–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1862743

- The Economist. (2019, December 14). The rights and wrongs of central-bank greenery. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/12/14/the-rights-and-wrongs-of-central-bank-greenery

- The Economist. (2020, November 28). Culture shock - Christine Lagarde is taking the ECB out of its comfort zone. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/11/28/christine-lagarde-is-taking-the-ecb-out-of-its-comfort-zone

- Thiemann, M., Birk, M., & Friedrich, J. (2018). Much ado about nothing? Macro-prudential ideas and the post-crisis regulation of shadow banking. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 70(S1), 259–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-018-0546-6

- Thiemann, M., Büttner, T., & Kessler, O. (2022). Beyond market neutrality? Central banks and the problem of climate change. Finance and Society, 1–21. http://financeandsociety.ed.ac.uk/ojs-images/financeandsociety/FS_Thiemann_et_al_EarlyView.pdf

- Tooze, A. (2021). Shutdown: How Covid shook the world’s economy. Penguin.

- Tucker, P. (2009, October 22). The debate on financial system resilience -macroprudential instruments. Barclays Annual Lecture. https://www.bis.org/review/r091029e.pdf

- UK Government. (2019a, June 27). UK becomes first major economy to pass net zero emissions law. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-becomes-first-major-economy-to-pass-net-zero-emissions-law

- UK Government. (2019b, July). Green finance strategy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/820284/190716_BEIS_Green_Finance_Strategy_Accessible_Final.pdf

- van ‘t Klooster, J. (2020). The ethics of delegating monetary policy. The Journal of Politics, 82(2), 587–599. https://doi.org/10.1086/706765

- van ‘t Klooster, J. (2022). Technocratic Keynesianism: A paradigm shift without legislative change. New Political Economy, 27(5), 771–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.2013791

- van ‘t Klooster, J., & Fontan, C. (2020). The myth of market neutrality: A comparative study of the European Central Bank’s and the Swiss national bank’s corporate security purchases. New Political Economy, 25(6), 865–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1657077

- Woods, S. (2022). Climate capital. Bank of England. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2022/may/sam-woods-speech-on-the-results-of-the-climate-bes-exercise-on-financial-risks-from-climate-change