ABSTRACT

Climate change is a key socioeconomic and environmental concern in South Africa. The South African government introduced several climate change initiatives to address the impacts of climate change, resulting in the proliferation of climate adaptation policies across spheres of government. This paper studies different climate change adaptation policies and climate policy paradigms (CPP) to understand the adaptation landscape; it explains and compares the changes in CPP in South Africa over time. We mapped 40 policy documents from 2004 to 2022, which shows 12 national policies, 12 provincial (sub-national) policy documents and 14 metropolitan city policy documents. We then used 12 national policy documents to illustrate and understand the CPP. The research shows that different stakeholders have shaped climate change adaptation policy, both private and public firms advised on climate change policy and there are a number of different funding partners supporting the adaptation policy like GEF, C40 and GIZ. The changing policy environment has introduced new frameworks, objectives and processes. Therefore, more efforts will be needed going forward to guide adaptation policy across national, provincial and local governments. We find that several CPPs have emerged, that is different paradigms encompassing a range of policy goals, framings and instruments. The present National CC Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS) mandates adaptation across all levels of government and allows all important stakeholders to address climate change consequences. This NCCAS increases the number and ambition of adaptation policy, encourages integrated approaches, policy coherence and clear direction on how to handle climate risks and impacts in varied South Africa and its global commitment. Changes in policy paradigm enable the use of new policy instruments, including funding and budget mechanisms. Finally, climate adaptation policy has become more ambitious and stringent, requiring all levels of government to plan for climate change.

Key policy insights

The climate change policy landscape in South Africa has grown over the past 18 years, with policy development across different spheres of government (national, sectoral, provincial and metros),

New CPPs have emerged, supported by new policy frames, goals and instruments.

The NCCAS provides a clear policy goal, which also provides new policy instruments to implement climate actions and acts to enhance integrated approaches,

The lack of domestic budget allocation remains a challenge for national government, but external partnerships have begun to provide support for policy development.

Notably, a shift from a flexible to stringent approach to climate policy is needed to deliver effective climate action.

1. Introduction

In South Africa, climate change is a major socioeconomic and environmental concern. As a result, the South African government launched a number of climate change responses to address the effects of climate change on natural resources, health, infrastructure and biodiversity (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014). One of the policy priorities is adaptation. Climate change adaptation is the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects in order to moderate harm or take advantage of beneficial opportunities, and plays a key role in reducing exposure and vulnerability to climate change (DEA, Citation2011; IPCC, Citation2022). Climate change adaptation is multidimensional and dynamic (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014), and addresses numerous hazards across multiple sectors (Reckien & Petkova, Citation2019). The need to adapt to the unavoidable effects of climate change has resulted in the proliferation of adaptation strategies (IPCC, Citation2022). South Africa signed the Paris Agreement (PA), which is universally regarded as a seminal point in the development of the international climate change regime under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The PA aims to strengthen the global response to climate change by limiting global warming to 2°C this century. The PA sets a global adaptation target to improve adaptive capacity, resilience and reduce climate change vulnerability. The PA recognizes that adaptation affects everyone, and intends to strengthen national adaptation efforts through support and international cooperation. All Parties should develop and implement National Adaptation Plans and publish and update an adaptation communication indicating their objectives, needs, plans and activities (UNFCCC, Citation2016). Despite the need for climate change adaptation actions, Ziervogel et al. (Citation2014) and Reckien et al. (Citation2019) observed that the adaptation process is slow to begin because it is complex and usually responds to multiple risks and spans multiple sectors that limit or facilitate adaptation at various levels.

Given that climate change policy, is rapidly becoming a key priority for developing countries, it is increasingly important to understand how climate change adaptation is framed and has evolved in countries to make climate adaptation policy central (Biswas & Rahman, Citation2023; Faling, Citation2020; Fankhauser et al., Citation2015; Vij et al., Citation2018). This policy framing provides context about situations, attributes, choices, actions on various issues. Policy framing is a term used in public policy and social movement theory to explain how actors try to comprehend and act on complex situations, for example, where climate change affects rainfall, which is a water sector issue (Badie et al., Citation2011). The impact of climate change on rainfall is observed as a water issue, therefore policy framing is a concept used in public policy and social movement theory to explain the process by which actors seek to understand and act on such complex situations (Badie et al., Citation2011).

To understand the climate change adaptation policy landscape, we use the Cambridge definition of the policy landscape as ‘a set of ideas or a plan of what to do in particular situations that has been agreed to officially by a group of people, a business organization, a government, or a political party’. Climate policies are shaped by different climate policy paradigms (CPPs), a set of prevailing ideas and strategies, institutions and provisions (Vij et al., Citation2018). A policy paradigm is a dominant and often taken-for-granted worldview (or collection of beliefs) about: policy goals, the nature of a policy problem and the instruments to address it (Hall, Citation1993). Competing CPPs create diverse policy responses to climate change impacts in part due to unstable political situations. Several drivers have been shown to influence CPPs, including lack of financial support, influence of national and international non-governmental organizations, and global policy frameworks (Rahman & Giessen, Citation2017; Vij et al., Citation2018).

In Bangladesh and Nepal, Vij et al. (Citation2018) analyzed policy documents between 1997 and 2016, and reported that in both countries, several CPPs have emerged: disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation, mainstreaming and localized action for adaptation. Faling (Citation2020) developed a longitudinal perspective focused on framing agriculture and climate change policies in Kenya; the findings indicate that climate smart agriculture (CSA) in Kenya is an incremental shift away from existing policy frames rather than a radical transformation. These two studies illustrate the role of government in developing and framing climate change policies, and as a driver of policy frames, alongside the role of donors, regional and global fora, and personal networks.

Several studies, including those by DFFE (Citation2018), Buchner et al. (Citation2015) and Cassim et al. (Citation2021), highlighted the need for increased resources, such as financial support, human capacity, and access to information and research, as well as institutional capacities, to support climate change initiatives across all three levels of government and individual sectors, such as agriculture and water resources. The allocation of financial resources towards climate change initiatives in South Africa is primarily focused on public and private finance, as well as global funding mechanisms. Despite this prioritization, the task of securing adequate funding remains a persistent challenge, as noted by the DFFE (Citation2018) and Cassim et al. (Citation2021).

Our understanding of how this climate change adaptation landscape is organized, and how policy paradigms in South Africa and elsewhere have evolved over time, is still limited. National policy drivers influence CPPs as much as the CPPs influence the policy drivers of change. So far, we know little about the CPPs and the drivers of CPPs. What this means for South Africa is the subject of this research. The primary research objective is to understand South Africa's climate change adaptation policy landscape, what has changed over the last two decades, including how policy paradigms have changed and why.

This research aims to address two research questions: (i) What are the national climate change adaptation policies, strategies and plans that have emerged in the last two decades? (ii) What are the changes observed in the CPP in the national climate change adaptation policies and why? This research may contribute towards the understanding and comprehension of climate change policy landscape and CPP, which is crucial for the development of future climate policies.

2. Theoretical framework

The theoretical foundation of this research is based on the climate policy paradigm and policy landscape (Faling, Citation2020; Hall, Citation1993; Vij et al., Citation2018). Policy paradigm is a framework of concepts and norms that outlines policy goals, the kind of instruments that might be employed to achieve them, and the nature of the issues they are supposed to solve (Hall, Citation1993). CPPs are characterized by how policy actors frame policy challenges, design policy goals and allocate resources. They are vital to understanding how a country plans to confront climate change. Howlett (Citation2009) asserts policy paradigms affect policy formulation, instrument choice and actor implementation preferences, citing Hall's work. Policy perspectives influence how actors respond to certain challenges (Vij et al., Citation2018).

Firstly, policy framing refers to how policy actors understand climate change impacts and propose solutions (Dewulf, Citation2013). Climate change can be presented as a negative externality to the human system (human vulnerability-centred framing) or as a biophysical challenge to the ecosystem (climate-centred framing) (Nagoda, Citation2015).

Second, policy goals show how climate change is integrated into the governing structure. Problem framing affects policy goals and tool selection (Candel & Biesbroek, Citation2016). Climate policy can have multiple goals. Goals can be set to lessen the effects of short-term disasters, with a focus on flood-resistant infrastructure and disaster assistance, and to promote education, health and community adaptability.

Third, meso level (policy sectors and coordination structures) have distinct role in climate policy paradigm. For this study, we recognize that climate change adaptation is cross-sectoral, therefore, coordinating those structures is vital for policy creation and execution. While the study does not investigate individual policy actors who contributed to policy frames, more attention will be given to which institutional arrangements contributes to the climate policy. Averchenkova et al. (Citation2019) reported that horizontal and vertical mechanisms for climate change governance are comprehensive but their effectiveness has varied. This study draws on the policy coordination and policy integration literature (Bauer et al., Citation2012; Russel et al., Citation2020). Identifying horizontal and vertical coordination and integration mechanisms helps operationalize policy aims and select industry instruments (Howlett, Citation2009). How have climate policy coordinating structures changed over time? Coordination is vital and governance systems are essential enablers and impediments to climate change adaptation (Bauer et al., Citation2012), because they utilize various policy instruments to modify target behaviour or relieve problematic conditions (Henstra, Citation2016).

Fourth, policy instruments are tools of governance, and they represent the relatively limited number of means or methods by which governments effect their policies (Howlett & Ramesh, Citation1993). They are seen as ways for governments to intervene and take action to reach their stated goals, and some of the policy instruments that have come to light are knowledge, money, power and organization. Policy instruments are defined as tools at the disposal of government that are intentionally designed to deal with the projected, long-term impacts of climate change (Biesbroek & Delaney, Citation2020). Therefore, there is a need to understand which policy instruments exist to support climate policy. While financing instruments are the focus of Vij et al. (Citation2018) research, this study focuses on broad policy instruments presented and defined by Henstra (Citation2016) that can be used to achieve climate policy objectives. These instruments include Nodality (information and knowledge), Authority (power and responsibility), Treasury (funding – costs and incentives) and Organization (government resources).

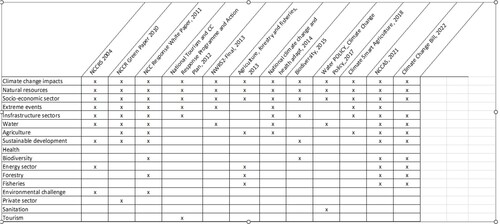

presents climate change policy characteristics, and presents the policy coding protocol informed by the CPP indicators (framing, goal, meso-level and policy instrument) showing how climate policy has changed over time (Vij et al., Citation2018), and codes for data analysis. provides an explanation of elements of climate policy paradigms.

Table 1. Climate change adaptation policy characteristics.

Table 2. Elements of climate policy paradigms, and policy coding indicators.

3. Methods

We used longitudinal analysis to identify and map of climate change adaptation policies developed between 2004 and 2022. From this database, we identify relevant adaptation policies using the policy characteristics analysis (). We then use the CPP framework to analyze the emergence and climate change adaptation policy paradigm focusing on relevant national climate adaptation policies in South Africa. We address two research questions. Question (I) is answered by mapping all the climate change policies in South Africa, that includes national, provincial and metropolitan levels, including climate change policy characteristics. The climate change adaptation policy characteristics include (i) Policy Title, (ii) Year of Publication, (iii) Sector focus, (iv) Policy focus level and (v) Funding. Question (II) focuses on national and sectoral policies, and is addressed by assessing climate change adaptation policy paradigm over time in South Africa.

3.1. Data collection

This research study uses a qualitative strategy and a case study methodology (Vij et al., Citation2017), to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of the climate change adaptation landscape and CPP. We used the Google Chrome search engine to find and identify pertinent policy documents (Berrang-Ford, Pearce, & Ford, Citation2015), at three distinct levels, national, provincial and local government (referred to as metros). The search query focused on the following key words which were connected using Boolean operators: (1) ‘climate change adaptation policy’ AND ‘climate change adaptation plan’ AND ‘climate change action adaptation’ OR ‘adaptation strategy’ OR ‘adaptation response plan’; (2) ‘South Africa’, (3) ‘water’ OR ‘biodiversity’ OR ‘agriculture’ OR ‘health’ OR ‘tourism’, (4) ‘provincial name’, (5) ‘metropolitan municipality name’. Documents were included when there was an explicit reference to the climate change policy, with possible synonyms such as climate change strategy, climate change plan, climate change action. The keywords and synonyms used for this study were checked against various key words. The main focus of this research focused mainly on climate change adaptation policy intervention, instead of mitigation.

The search query was iteratively refined by including more and alternative synonyms until the key publications showed up in the search results. The web search was terminated when the results began to repeat and reached a series of irrelevant results. The different policy documents were then analyzed using Atlas.ti (version 9) using CPP codes developed in . In cases where the policy document was not available online, direct contact with the sector actors was initiated to access the document.

3.2. Data analysis

We grouped and mapped climate change policy documents into different levels of government, between 2004 and 2022. Policy documents were grouped according to their title, year of publication, sector focus and policy levels (national, provincial or metropolitan cities). National policies included sectoral policies relevant to adaptation, that is, water, agriculture, health and biodiversity. We used this dataset to reconstruct the climate change policy timeline and focus over the past 18 years (, Results section). The CPP analysis focused on relevant national climate adaptation policies, as it is widely believed that this is the locus where significant levels of influence and change take place. Policy documents were coded and analyzed based on four CPP indicators for each time period (). To achieve the CPP analysis, we analyzed the content and language used in policy documents to capture policy framing, goals, coordination and instruments (Vij et al., Citation2017). Some policy documents, for example, describe how climate change increases vulnerability to natural resources, increases extreme events and their impacts on socio-economic sectors, ecosystems and infrastructure. We extracted and analyzed the goals of national climate policies and climate-related sectoral policies. We only included policy goals that explicitly reference climate change adaptation to allow comparison over a certain time period. For meso-level areas, we only analyzed coordination structures, both vertical and horizontal approaches as a key mechanism for decision-making on policy goals and instruments. For each policy document, we noted the number and name of coordination mechanisms that exist to support climate change adaptation policy. For policy instruments, we used the Nodality, Authority Treasury and Organization typology discussed in Section 2 (Henstra, Citation2016).

4. Results

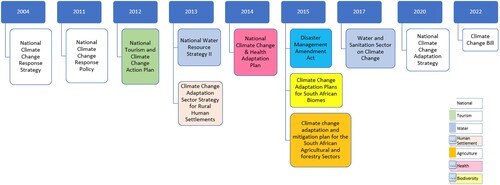

The results present the national climate change adaptation policies and relevant sectoral policies (in different colours) for adaptation from 2004 to 2022 (). The selected national climate change policies and national sectoral policies were analyzed to understand changes on policy frames over time. The CPP analysis presents the dominant climate policy frames and shift in paradigm () over time.

Figure 1. National climate change and sectoral policies (in different colours) of relevance to adaptation in South Africa from 2004 to 2022.

Figure 2. Key climate change policy frames found in policy documents in South Africa published from 2004 to 2022.

4.1. Climate change policy at national and subnational level

Mapping of the climate change policy landscape led to the identification of 40 climate change policies developed between 2004 and 2022. These policies include both adaptation and mitigation, however, this paper focused on policies relevant to adaptation interventions. The policy levels were differentiated as national, provincial and metropolitan municipalities. Our results indicate that out of the 40 climate policies that were identified, 14 are national level policies (including 9 sectoral policies), 14 are for metropolitan municipalities and 12 are for provincial governments. The first climate change policy document was developed in 2004, which was then followed by metropolitan cities in 2006, and provinces in 2008, and sector departments in 2011. We also observed that the majority of climate policies (70%) were developed by consulting firms, and funded by global and private partnership mechanisms, that is, through international organizations including Global Environmental Facility (GEF), C40 and German International Cooperation (GIZ).

4.2. Climate policy paradigm

The analysis focused on the climate policy paradigm and how this has evolved over time, focusing on the 12 national and sectoral climate policies (). These policies were identified through screening of relevant adaptation policies. From the 12 policies, CPP analysis was conducted to capture policy framing, goals, coordination and instruments. We found that the climate policy paradigm shows different frames, goals, coordination mechanisms and instruments were identified to support climate policy. illustrates similarities and differences between climate policy frames of various relevant adaptation sectoral policies derived from the policy analysis.

Climate policy framing

The first key document is the National Climate Change Response Strategy (NCCRS) (2004) policy framework which represents South Africa's initial response to the issue of climate change at the national level (DEA Citation2004). The NCCRS (2004) climate policy frame identifies climate change as a global threat with greatest environmental challenges, a threat to sustainable development, and the need for capacity to respond to it. According to the NCCRS (2004), ‘global climate change is possibly the greatest environmental challenge the world is facing this century, and is more about serious disruptions of the entire world's weather and climate patterns, including impacts on rainfall, extreme weather events, and sea level rise’ (p. 3, 2004). While, the NCCRS (p. 3, 2004) was less sector specific, it stressed the importance of preparedness to deal with climate change consequences.

In 2011, South Africa developed the National Climate Change Response Paper (NCCRP 2011), which builds on the NCCRS (2004), but increased the sectoral focus on biodiversity, forestry and health (DEA Citation2011). The NCCRP linked climate impacts such as temperature changes to shortage of water, human health, agriculture and extreme events such as fires, floods and drought (NCCRP p. 11, 2011). From 2012 onwards, sectoral policies were framed as a standalone initiative to reduce climate change's impacts on tourism, water, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, human health and biodiversity. For example, the National Climate Change and Health Adaptation Plan (p. 4, 2014) focused on how human health is directly exposed to the impacts of climate change through extreme weather events (drought and floods) and natural resources (food, water, air, ecosystems).

In 2020, the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS) policy frame builds on South African’s experience with climate change effects, that includes increased temperatures, prolonged droughts and devastating floods (DFFE Citation2020). ‘SA have not only felt the rise in average daytime temperatures, but also experienced the effects of either prolonged droughts or devastating flood’ – NCCAS (2020, p. 2). This provides not only changes in the policy frame, but include the realization of the temporal scale, where the current timeframe informs climate policy paradigm. This shifts the policy focus that dominated the early 2000s–2010s from global policy framing to national and subnational levels. NCCAS (2020) encourages collective climate policy development, strengthens the links from global to local level, but more focused on national to local adaptation action, with the inclusion of ‘the private sector, the research community and civil society’ – (p. 2, 2020). South Africa's commitment to the PA is through the NCCAS which underpins South Africa's NDC adaptation commitments. However, NDC preparation can increase political awareness, institutional innovation and coordination, and stakeholder engagement (Röser, Widerberg, Höhne, & Day, Citation2020). NDCs include direct mitigation targets, strategies, plans and activities for low-GHG emission development, or mitigation co-benefits through economic diversification plans and adaptation actions (UNFCCC Secretariat, Citation2021).

In addition, the framing of the NCCAS (2020) placed emphasis on expanding the key priority sectors identified in the NCCRP (2011). The NCCAS goes beyond NCCRP (2011) sectors to include transportation and infrastructure, energy, mining, oceans and coast. The NCCAS promotes the National Development Plan by encouraging environmental sustainability and an equitable transition to a low-carbon economy. The NDP objectives are strengthened in addressing climate change impacts. The NDP (p. 199, 2012) states that ‘adaptation strategies in conjunction with national development strategies are implemented, including disaster preparedness, investment in more sustainable technologies and programs to conserve and rehabilitate ecosystems and biodiversity assets’.

The development of the Climate Change Bill (CCB)(DFFE, 2022) set changes in the policy paradigm (DFFE, Citation2022). The CCB is a legislative framework that enforces climate change actions and compliance, while other policies are implemented on a voluntary basis; this makes CCB a strict policy instrument. The CCB (p. 10, 2022) clearly states that ‘Climate Change Response: Provinces and Municipalities must comply with any requirements as may be prescribed by the Minister inclusive of the relevant technical guidelines’. Clause 7 of the CCB (2022) requires every state organ to coordinate and harmonize its climate change policies, plans, programmes, decisions and decision-making processes to account for climate change risks and vulnerabilities and to implement the Act's principles and objectives.

Based on these findings, we see that the NCCAS (2020) and the CCB (2022) build upon the NCCRP's (2011) cross-sectoral approach and present yet another paradigm frame; they prioritize additional key sectors and the legislative framework that focuses on compliance and enforcement.

(ii) Policy goals

While the 2004 NCCRS provided the foundation of a national climate change response, its policy goals were not solely centred on climate change. It focused on integrated pollution and waste management and other national energy, water and agriculture policies. South Africa's first climate policy came in 2011, the NCCRP, addressed climate change impacts by strengthening social, economic, environmental and emergency response capability. The NCCRP (2011) highlighted increasingly frequent and strong weather systems and climate variability as signs of climate change. The NCCRP guided South African climate change policy. It prioritized climate change integration and mainstreaming within sector policies and across national, provincial and local governments. Sectoral and provincial climate change strategies proliferated afterward.

The policy also aimed to reduce climate change impacts by creating capacity, improving governance and coordinating institutions. The National Tourism and Climate Change Response Program and Action Plan (p. 5, 2012) ‘assisted the tourism industry to build its resilience and capacity to adapt to climate change impacts,’ the Health Plan (p. 10, 2014) ‘provided a broad framework for health sector action towards adaptation to climate change,’ and Biodiversity (p. 3, 2015) ‘presented potential adaptation responses measures that will guide current and future decisions.’ Several climate policies proposed mainstreaming or integration of adaptation responses into sectoral planning and implementation. The development of the NCCAS (2020) provides a policy paradigm, with the revised policy goals focusing on a climate resilient economy and society, development pathways, innovative solutions and nature based sectoral and subnational climate plans. In addition, the NCCAS (P21, 2020) places a greater emphasis on the international obligation to support the implementation of the Paris Agreement in accordance with the UNFCCC.

(iii) Meso level (policy sectors and institutional coordination)

In 2011, the NCCRP emphasized the need for cross-sectoral integration, providing a policy framing with interconnectedness between sectors. The NCCRP (2011) showed how climate variables such as temperature and rainfall changes affect water, human health, agriculture, leading to floods and drought. From 2012 onwards, policy sectors began to develop their standalone policies; this includes tourism, water, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, human health and biodiversity. In 2020, the NCCAS goes beyond these sectors to include transportation and infrastructure, energy, mining, oceans and coast. Based on these findings, the policy sectors have increased over time.

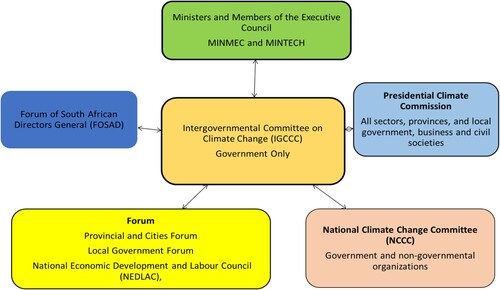

In terms of coordination, The NCCRS (2004) recognizes the importance of effective coordination amongst various departments, emphasizing that ‘the Government Committee for Climate Change (GCCC) was established to facilitate coordination between departments’ (p. 14, 2004). The national coordination mechanisms that were set up in 2004 as part of the NCCRS are still in place, that includes the National Committee for Climate Change (NCCC) which involves provincial and local government; Ministers and Members of the Executive Council (MINMEC); and the Technical Arm of MINMEC (MINTECH) to support climate policy (NCCRS, p. 29, 2022) (see ). In terms of the overall coordination, the National Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and Environment (DFFE) is in charge of ensuring that the national coordination mechanisms are stable and consistent. This means that while the number of policy sectors increased, the coordination mechanisms installed in 2004, remain relevant through-out to 2022, as emphasized in the CCB (2022). However, specific sector mechanisms were installed to address sector policy development.

Key climate sectors developed inter-sectoral and national coordination structures for coordination and integration, that includes Tourism and Climate Change Task Team, National Climate Change and Health Adaptation Steering Committee, Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) Provincial and District Coordination Units. Various climate policies have also highlighted the contributions of private businesses, organized labour and civil society in shaping and enforcing climate policy. The NCCRP, for instance, states (p. 38, 2011) that ‘government is committed to substantive engagement and, where appropriate, partnerships with stakeholders from industry, business, labour, and civil society in a manner that enhances coordination.’ The NCCRP identified the National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC) as the authority to promote growth, equity and participation through social dialogue (p. 39, 2011).

The South African Local Government Association support, represent and advise local government action in the inter-governmental system, ensure the integration of climate adaptation and mitigation actions into local government plans and programmes, and lobby for the necessary regulatory measures and resources to support local government in this regard (NCCAS, p. 38, 2020). This is a demonstration of another institution that is coordinating climate change at local government level.

Municipal, district and provincial climate forums and the Presidential Climate Commission were introduced in the CCB (2022). The Presidential Climate Commission oversees and facilitates a just and equitable transition to a low-emissions, climate-resilient economy. The introduction of this fora means all government levels can coordinate climate change response actions amongst (horizontal coordination) and relevant (vertical coordination) to their government level (CCB, p. 18, 2022) ().

(iv) Policy instruments

Different policy instruments were developed for different climate policies and at various timelines. The nodality instruments are the mostly common instruments across all climate policies. For example, in 2004, the NCCRS identified education, training, capacity building, research, development and demonstration as the main focus nodality instruments (pp. 5–7); in 2011, the NCCRP (p. 9, 2011) introduced systemic observation, knowledge generation and monitoring and evaluation system; in 2014, the Health Policy identified international information exchange and cooperation, and monitoring and surveillance system to detect climate change and health trends early; and in 2020, the NCCAS identified climate services systems (p. 9). All these instruments aim to inform and improve knowledge, awareness, and capacity which can only provide evidence that there is strong reliance on scientific results for decision-making and capacity building. Our findings show that capacity building and research and knowledge sharing remains key policy instruments. However, our findings also indicate a paradigm shift with the introduction of new types of nodality instruments such as the climate services systems, risk and vulnerability assessment framework, and mainstreaming of adaptation responses, to support climate policy.

Authority instruments provide policy actors with motivation for commitment to obey state-issued directives out of respect for government legitimacy or fear of penalties. While, all other policies were developed and implementation was not strictly enforced between 2004 and 2020, the development of CCB in 2022, means that responsibilities has been allocated to all policy actors. The CCB (2022) is the first climate change legal framework of its kind in South Africa, to provide motivation, allocate responsibilities and command adaptation actions. This is the new approach where changes are observed from a flexible to a stringent approach to climate policy. The CCB provides a new policy paradigm by presenting a legal framework for all policy actors to comply with, which is more authoritative and stringent in nature.

The treasury instruments such as financial resources finance were identified throughout the analysis period. Donor funding, private and public finance, and international finance were identified (NCCRS, 2004); climate finance (NCCRP, 2011); private sector funding (Water Policy, Citation2017); microfinance institutions and climate finance (DAFF, Citation2018) and national budget and development funding have all been proposed (NCCAS, 2020). The NCCAS (p. 53, 2020) aims to enable substantial flows of climate change adaptation finance from various sources. However, the CCB (2022) aims to create a financial liability for the government, to support climate policy (p. 27, 2022). Our findings indicate that both NCCAS and CCB supports a mixture of treasury instruments to support climate actions, that includes donor funding, private and public finance, international and national finance. This presents a new finance paradigm by providing a variety of financial instruments for future climate policies.

The organizations instruments show that different government departments provided resources to enable climate policies. This is demonstrated by various institutional arrangements and climate policies for programme development and enhanced focus on climate policy. Our findings indicate that government personnel and policies in the climate change field increased between 2004 and 2022, with the increase in sector policies and programme development. For example, the development of the Water Policy in 2017 provided an opportunity to set-up new institutional arrangements which require more government personnel to support sector policy development. The NCCRP (2011) encouraged reviewing and integrating climate change responses into existing or new policies, legislation or strategies. This intent sought to improve existing activities’ efficiency and competitiveness (p. 15).

The 2004 and 2011 prioritization of climate change legislation was realized in 2022, whereby the CCB (2022) provides a coordinated and integrated response by the economy and society to climate change and its impacts (p. 6). CCB (2022) assigns responsibilities, confers decision-making authority, defines liabilities and enables other instruments. However, this shows that organizational instruments have improved to ensure governance and effective coordination process, through institutional capacity and tasks teams, to ensure that climate change action is a mandatory issue across all government levels.

5. Discussion

The paper examined South Africa's climate adaptation policy landscape and how climate policy has changed over time. Our research shows that the climate adaptation policy landscape has evolved due to an increase in the number of climate adaptation policies adopted at the municipal, provincial and national levels of government, providing responsibilities to sectors, provinces and metros to address and respond to climate change impacts, encouraging coordination of responses and inclusion of climate change intervention into different plans. Since 2011, we have seen an increase in the number of provincial climate adaptation policies, which can be attributed to the policy mandate of the NCCRP (2011) and the provision of funding by external partners such as the GIZ. South Africa's climate change policy was strengthened by external funding. These results support Vij et al. (Citation2018) who found that financial assistance, technical and societal awareness, political willingness and global policy frameworks may influence CPPs. Hermwille (Citation2016), Bhore (Citation2016) and Seo (Citation2017) concur that an international policy instrument like the PA is a milestone for the international community and represents the global resolve to combat climate change. In response, DFFE (Citation2018) stated that South Africa has committed to fulfilling its international obligations, which affects climate change planning at the national and subnational levels and led to the NCCAS. This shows the coherence between the national and international climate change agenda. The NCCAS aims to reduce vulnerability and fulfils international commitments. This integrates global and national climate planning.

Climate policy framing

The first national climate change response strategy (NCCRS, 2004) framed climate change by combining the global perspective with the national perspective. In 2011, the NCCRP (2011) increased the focus on national weather and climate patterns, and the implications on key sectors. Subsequent policies at sectoral, provincial and metro levels, placed more emphasis on national and local climate change impacts, natural resources, socio-economic sectors, extreme events, infrastructure and sustainable development. This remained the core framing of climate change policy since 2011.

The NCCAS (2020) brought a new framing supported by national and sub-national climate change impacts and increased connectivity to other sectors. The NCCAS (2020) provides a more inclusive approach to adaptation policy, a common reference point for climate change adaptation efforts across South Africa, and a platform for national climate change adaptation objectives to guide all sectors of the economy. The NCCAS (2020) is developed from actual life experience, and presents climate change with a clear temporal scale. It locates climate change impacts as a current threat, and no longer a future threat. Subsequently, the CCB (2022) established a climate policy legislative framework that changed the policy paradigm from operational to authority-based. The CCB introduces institutional governance and coordination for regulatory and mandatory approach, while other national policies set out governance processes, administrative and functional structures.

(ii) Policy goals

Climate policy goals changed over time. In 2004, the NCCRS focused on climate change as a way to support integrated pollution and waste management frameworks. Climate change was only mentioned as a global issue. In 2011, the NCCRP defined climate policy and encouraged integration of climate policy with sectoral, provincial and local government goals. These findings support Candel and Biesbroek (Citation2016), who found that policy goals are often influenced by the framing of the problem and set the scope for further implementation through the choice of instruments, such as climate change impacts on economic, social and environmental sectors. The implementation of national climate policy has resulted in the establishment of new policies at national provincial and local government, with more policy goals and more policy actors. The policy goals centred around enhancing capacity, improving governance and fostering institutional coordination in order to address and respond to the challenges posed by climate change.

Our findings show that the NCCAS (2020) enhances focus on climate resilient economy and society, development pathways, innovative solutions, and nature based sectoral and subnational climate plans. It serves as a bridge between global commitments and national responses, thereby widening the normative framing around adaptation, while calling for stronger adaptation commitments from states. It is explicit about the multilevel nature of adaptation governance, and outlines stronger transparency mechanisms for assessing adaptation progress. It expands its goals to cover more sectors than previous national climate policy documents. Expanded coverage of sectors includes transportation and infrastructure, energy, mining, oceans and coast (NCCAS, p. 13, 2020). This finding shows that adaptation responses are emerging in various sectors with different policy goals (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014). In 2022, South Africa developed the CCB (2022), for policy compliance and enforcement. Thus, the CCB (2022) provides all policy actors a new legislative policy paradigm.

(iii) Policy coordination

Policy coordination and integration mechanisms established in 2004, with the initial NCCRS, remain a key critical and instrumental platform to guide South Africa’s climate policy paradigm. This is in line with Howlett (Citation2009) who argued that identifying coordination mechanisms is key to the definition of policy frames, to the operationalization of policy goals and to the selection of policy instruments to be used at the sector level. The evolution of South Africa’s climate policy landscape indicates that different policy actors managed and coordinated within various structures, to enable horizontal and vertical integration. For example, the South African Climate Change Working Group (IGCCC) coordinates vertically (from national to local levels) and horizontally (across national departments). In addition, the IGCCC stressed sector-wide and sector-specific coordination structures. This approach could help the country achieve sustainable development and a just, low-carbon society. The CCB (2022) proposes vertical and horizontal integration structures, including municipal, district, and provincial climate forums and the Presidential Climate Commission, to guide climate policy and align it with new policy instruments. The NCCAS (2020) and CCB (2022) present operational elements using new coordination structures. The legislative framework they provide is the foundation of adaptation governance.

(iv) Policy instruments

Our study identifies several different types of policy instruments, similar to those reported by Vij et al. (Citation2018) and Lesnikowski et al. (Citation2021). Nodality instruments, focused on information and knowledge generation, were found to be more common and consistent across the time periods studied (2004−2022); these in turn support decision-making process for climate policy. Our findings echo observations made by Henstra (Citation2016) and Vij et al. (Citation2018) that treasury instruments, particularly public and donor funding, were identified as key instruments for implementation of climate adaptation policy. Funding from outside sources, including GEF, C40 and GIZ, influenced the formulation of the policy. There is also a direct connection between national policy and global influence. However, Cassim et al. (Citation2021) and Keen and Winkler (Citation2020) reported that there is more public financing of climate change than what is actually reported. While climate finance is becoming more inclusive of adaption spending, the Climate Finance Landscape (2021) found that climate spending and investment in South Africa, for the most part, remains siloed between the public and private sector. Aside from the intentional efforts of a few development finance players, collaboration is limited. Although the majority of finance still flows towards initiatives focused on mitigation, an increasing amount of investment and spending is expected to be directed towards climate adaptation initiatives. Lastly, the lack of an agreed-upon definition for climate finance makes tracking and aggregating climate finance flows particularly challenging.

Our results also show that climate policies prioritize organization-based instruments. That is, the use of government resources and personnel to implement adaptation policy objectives. Government resources and personnel develop programmes that support climate policy. This observation support Henstra (Citation2016) who concluded that organizational instruments are arguably key element of groundwork. These observations further indicate that the initial governance coordination remains key in authority instruments, to increase policy effort, and to mainstream and mandate climate change adaptation into various key sectors. The NCCAS and CCB thus provide a new policy paradigm by presenting a research and legal framework for all policy actors to comply with. This framework is more authoritative in nature, through use of compliance and enforcement levers. It includes a mandate to the national Cabinet Minister responsible for environmental affairs, to work with all sectors and spheres of government, with specified timelines. In addition, the CCB makes provision for implementation of NCCAS across sectors, which then allows the integrated response to climate change impacts.

6. Conclusion

This study reports on the historical context and current state of climate change policy in South Africa, with a deepened focus on adaptation. We conclude that the climate change policy landscape has grown over the past 18 years, with policy development across different spheres of government (national, sectoral, provincial and metros), and new climate policy paradigms supported by new policy frames, goals and instruments. Climate policy planning is an essential part of the response to the effects of climate change at all governmental levels (national, provincial and local). This research shows that new policies were enacted to prepare for the consequences of climate change. Funding from outside sources, including GEF, C40 and GIZ, enabled the formulation of the policy. There is also a direct connection between national policy and global influence. Reported funding from private and global finance mechanisms may be related to the insufficient, or the limitations of, public budget allocations for climate change policy.

Regarding the climate policy paradigm (CPP), the introduction of the NCCAS in 2020 established clear and ambitious policy objectives, centred on climate-resilient economy and society, development pathways, and innovative solutions across all sectors and levels of government. By broadening the normative framework surrounding adaptation and enhancing policy instruments, the policy objectives of NCCAS created opportunities for all major role players and stakeholders. The NCCAS, compared to the prior policies (2004–2018), provides greater coherence and coordination between institutions, levels of government, and global commitments regarding climate change adaptation activities. It is clear, however, that substantial finance will be required to implement the NCCAS to achieve meaningful adaptation in South Africa.

The new CPP in the NCCAS and CCB provides new institutional structures, opportunities for research and knowledge generation for climate change adaptation. The NCCAS and CCB thus provide a new policy paradigm by presenting a research and legal framework for all policy actors to comply with. This framework is more authoritative in nature, through use of compliance and enforcement levers. It includes a mandate to the national Cabinet Minister responsible for environmental affairs, to work with all sectors and spheres of government, with specified timelines. In addition, the CCB makes provision for implementation of NCCAS across sectors, which then allows the integrated response to climate change impacts.

We conclude that this CPP has improved connectivity between all instruments, including nodality, treasury, authority and organizational instruments. This shows that policy goals and framing influence the types of instruments that can be proposed to support climate actions. However, the CCB comes short in finance instruments. Therefore, realizing the NCCAS and the full strength of the CCB will remain a challenge due to the lack of budget. We conclude that there is a shift from a flexible to a stringent approach to climate policy, one that takes into account both global and national issues, research knowledge and projections, and community experience. While the focus of this research was on South Africa’s climate change adaptation policy landscape and its policy paradigms, it remains critical for others to understand their CPP and drivers influencing their policy goals and policy instruments.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (504.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the NRF-Nuffic Doctoral Scholarship (Unique Grant No: 120198) for funding the research. Diana Reckien was partly funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant No. 869395.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Averchenkova, A., Gannon, K. E., & Curran, P. (2019). Governance of climate change policy: A case study of South Africa. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Badie, B., Berg-Schlosser, D., & Morlino, L. (Eds.). (2011). International encyclopedia of political science. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412994163.

- Bauer, A., Feichtinger, J., & Steurer, R. (2012). The governance of climate change adaptation in 10 OECD countries: Challenges and approaches. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 14(3), 279–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2012.707406

- Berrang-Ford, L., Pearce, T., & Ford, J. D. (2015, June 1). Systematic review approaches for climate change adaptation research. Regional Environmental Change, 15, 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0708-7

- Bhore, S. J. (2016). Paris agreement on climate change: A booster to enable sustainable global development and beyond. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(11), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111134

- Biesbroek, R., & Delaney, A. (2020). Mapping the evidence of climate change adaptation policy instruments in Europe. Environmental Research Letters, 15(8), 083005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab8fd1

- Biswas, R. R., & Rahman, A. (2023). Adaptation to climate change: A study on regional climate change adaptation policy and practice framework. Journal of Environmental Management, 336(2023), 117666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117666.

- Buchner, B. K., Trabacchi, C., Mazza, F., Abramskiehn, D., & Wang, D. (2015, November). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2015. Climate Policy Initiative. www.climatepolicyinitiative.org

- Candel, J. J. L., & Biesbroek, R. (2016). Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sciences, 49(3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9248-y

- Cassim, A., Radmore, J.-V., Dinham, N., & McCallum, S. (2021, January). South African climate finance landscape 2020. 60. https://www.green-cape.co.za/assets/South-African-Climate-Finance-Landscape-2020-January-2021.pdf

- DAFF. (2018). Climate smart agriculture strategic framework (Vol. 41811, pp. 40–113). Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Government of South Africa.

- DEA. (2004). A national climate change response strategy. Response (September), 48. Retrieved from http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/seminar/application/pdf/sem_sup3_south_africa.pdf.

- DEA. (2011). National Climate Change Response White Paper. Department of Environmental Affairs, Republic of South Africa. https://www.sanbi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/national-climate-change-response-white-paper.pdf

- Dewulf, A. (2013). Contrasting frames in policy debates on climate change adaptation. WIREs Climate Change, 4(4), 321–330. http://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.2013.4.issue-4

- DFFE. (2018). South Africa’s Third National Communication under the UNFCCC. Department of Environmental Affairs, Republic of South Africa.

- DFFE. (2020). National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy. Department of Forestry, Fisheries & Environment, Republic of South Africa.

- DFFE. (2022). Climate Change Bill (draft). Department of Environmental Affairs, Republic of South Africa., (45299), 1–28.

- DWS. (2017). Water and sanitation sector policy on climate change. Department of Water and Sanitation, Government of South Africa. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420004946.ch16.

- Faling, M. (2020). Framing agriculture and climate in Kenyan policies: A longitudinal perspective. Environmental Science and Policy, 106, 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.01.014

- Fankhauser, S., Gennaioli, C., & Collins, M. (2015). The political economy of passing climate change legislation: Evidence from a survey. Global Environmental Change, 35, 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.008

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state : The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246. http://www.jstor.org/stable/422246

- Henstra, D. (2016). The tools of climate adaptation policy: Analysing instruments and instrument selection. Climate Policy, 16(4), 496–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1015946

- Hermwille, L. (2016). Climate change as a transformation challenge: A new climate policy paradigm? GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 25(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.25.1.6

- Howlett, M. (2009). Governance modes, policy regimes and operational plans: A multi-level nested model of policy instrument choice and policy design. Policy Sciences, 42(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9079-1

- Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (1993). Patterns of policy instrument choice: Policy styles, policy learning and the privatization experience. Policy Studies Review, 12, 1–2.

- IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022 - Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability - Summary for Policymakers. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

- IPCC. (2023). Synthesis Report of The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

- Keen, S., & Winkler, H. (2020). Enhanced direct access finance: SANBI and the adaptation fund. University of Cape Town.

- Lesnikowski, A., Biesbroek, R., Ford, J. D., & Berrang-Ford, L. (2021). Policy implementation styles and local governments: The case of climate change adaptation. Environmental Politics, 30(5), 753–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1814045

- Nagoda, S. (2015). New discourses but same old development approaches? Climate change adaptation policies, chronic food insecurity and development interventions in northwestern Nepal. Global Environmental Change, 35, 570–579. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.014

- PCC. (2021). South Africa’s NDC Targets For 2025 And 2030. Technical analysis to support consideration of the emissions trajectory in South Africa’s NDC. Republic of South Africa.

- Rahman, M. S., & Giessen, L. (2017). Formal and informal interests of donors to allocate aid: Spending patterns of USAID, GIZ, and EU forest development policy in Bangladesh. World Development, 94, 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.012

- Reckien, D., & Petkova, E. P. (2019). Who is responsible for climate change adaptation?. Environmental Research Letters, 14(1), 014010. http://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaf07a

- Reckien, D., Salvia, M., Pietrapertosa, F., Simoes, S. G., Olazabal, M., De Gregorio Hurtado, S., Geneletti, D., Krkoška Lorencová, E., D'Alonzo, V., Krook-Riekkola, A., Fokaides, P. A., Ioannou, B. I., Foley, A., Orru, H., Orru, K., Wejs, A., Flacke, J., Church, J. M., Feliu, E., … Heidrich, O. (2019). Dedicated versus mainstreaming approaches in local climate plans in Europe. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 112, 948–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.05.014

- Röser, F., Widerberg, O., Höhne, N., & Day, T. (2020). Ambition in the making: analysing the preparation and implementation process of the Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 20(4), 415–429. http://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1708697

- Russel, D., Castellari, S., Capriolo, A., Dessai, S., Hildén, M., Jensen, A., & Tröltzsch, J. (2020). Policy coordination for national climate change adaptation in Europe: All process, but little power. Sustainability (2020), 12, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135393

- Seo, S. N. (2017). Beyond the Paris agreement: Climate change policy negotiations and future directions. Regional Science Policy and Practice, 9(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12090

- Turnpenny, J., Haxeltine, A., Lorenzoni, I., Riordan, T. O., & Jones, M. (2005, January). Mapping actors involved in climate change policy networks in the UK. Interactions. http://www.tyndall.ac.uk/content/mapping-actors-involved-climate-change-policy-networks-uk

- UNFCCC. (2016). Key aspects of the Paris Agreement. UNFCCC, 1–6. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement/key-aspects-of-the-paris-agreement

- UNFCCC. (2021). Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement: Nationally determined contributions under the Agreement. FCCC/PA/CMA/2021/8/Rev.1. FCCC/PA/CM(December 2020), 1–32. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2021_08r01_E.pdf

- Vij, S., Biesbroek, R., Groot, A., & Termeer, K. (2018). Changing climate policy paradigms in Bangladesh and Nepal. Environmental Science and Policy, 81, 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.12.010

- Vij, S., Moors, E., Ahmad, B., Uzzaman, A., Bhadwal, S., Biesbroek, R., Gioli, G., Groot, A., Mallick, D., Regmi, B., Saeed, B. A., Ishaq, S., Thapa, B., Werners, S. E., & Wester, P. (2017). Climate adaptation approaches and key policy characteristics: Cases from South Asia. Environmental Science and Policy, 78, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.09.007

- Ziervogel, G., New, M., Archer van Garderen, E., Midgley, G., Taylor, A., Hamann, R., Stuart-Hill, S., Myers, J., & Warburton, M. (2014). Climate change impacts and adaptation in South Africa. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(5), 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.295