ABSTRACT

Governments and international organizations are increasingly using public funds to mobilize and leverage private finance for climate projects in the Global South. An important international organization in the effort to mobilize the private sector for financing climate mitigation and adaptation in the Global South is the Green Climate Fund (GCF). The GCF was established under the UNFCCC in 2010 and is the world’s largest dedicated multilateral climate fund. The GCF differs from other intergovernmental institutions through its fund-wide inclusion of the private sector, ranging from project design and financing to project implementation. In this paper, we investigate private sector involvement in the GCF through a qualitative exploratory research approach. We ask two main questions: Do private sector projects deliver on their ambitious goals? What are the tensions, if any, between private sector engagement and other principles of the GCF (most importantly the principles of country ownership, mitigation/adaptation balance, transparency, and civil society participation)? This paper argues that private sector involvement does not provide an easy way out of the financial constraints of public climate financing. We show that the GCF fails to deliver on its ambitious goals in private sector engagement for a number of reasons. First, private sector interest in GCF projects is thus far underwhelming. Second, there are strong tradeoffs between private sector projects and the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC) principles of country ownership, transparency, and civil society participation. Third, private sector involvement is creating a mitigation bias within the GCF portfolio. Fourth, while the private sector portfolio is good at channeling funds to particularly vulnerable countries, it does so mostly through large multi-country projects with weak country ownership. Fifth, there is a danger that private climate financing based on loans and equity might add to the debt burden of developing countries, destabilize financial markets, and further increase dependency on the Global North.

Key policy insights

The main problem of GCF private sector engagement is lack of interest from the private sector. For now, the GCF will strongly rely on public funds for its mission; thus establishing a strong track record of high impact climate projects should take priority over the promises of mobilizing private financial resources.

Given the strong mitigation bias of private sector projects, public sector financing needs to be even more focused on climate adaptation.

The GCF needs to ensure that the private sector’s short-term interests in profitability do not undermine its own long-term goal of transformational change and development.

The GCF needs to make sure that private sector projects are compatible with Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC) principles and its own rules on country ownership, transparency, and civil society participation.

The GCF needs to pay more attention to building a sound institutional framework to ensure that climate finance does not add to the already existing debt burden, economic dependency, and financial instability of partner countries.

1. Introduction

The GCF is an international organization established in 2010 as a financial mechanism under the UNFCCC and its 198 parties (as of 2023) including all UN member states and the European Union. The GCF is based in Songdo, South Korea and started approving projects in 2015. The GCF is the world’s largest dedicated multilateral climate fund with a total project portfolio of 200 projects valued at USD 40 billion as of September 2022 (GCF, Citation2022e). Unlike similar intergovernmental organizations such as the World Bank or the IMF, the GCF features important ‘institutional innovations’ (Kalinowski, Citation2020), including donor-recipient parity on its board; civil society engagement; and, most importantly for this paper, private sector involvement.

Countries in the Global South need vast resources to finance climate mitigation and adaptation to combat global warming and its consequences. Governments in the Global North have promised (but so far have failed to deliver) to channel USD 100 billion a year into new and additional climate finance to the Global South from 2020 on (UNFCCC, Citation2010, p. 7). Substantial parts of this climate finance are supposed to come from mobilizing the vast resources of the private sector (GCF, Citation2022g; Pauw, Citation2017; Stoll et al., Citation2021). The private sector needs mobilization because, intrinsically, private investors make investment decisions not based on climate goals determined by public interest but based on the (expected) profitability of these investments. Consequently, governments and international organizations try to use their limited public resources to mobilize large private financial resources.

This paper is one of the first attempts to investigate the GCF’s private sector portfolio and lays the groundwork for future empirical studies. We explore how private sector projects work and investigate their problems and shortcomings. In particularly, this paper develops a broader development perspective on private climate projects that takes into account established principles of effective development cooperation. We ask two main questions: What is the contribution of private sector projects to the GCF mission of climate mitigation and adaptation in the Global South? What are the tensions and tradeoffs between private sector engagement and the goals of the GCF to ensure country ownership and achieve a mitigation/adaptation balance, transparency, and civil society participation?

Due to the GCF’s relatively young age, research on it remains limited. This is particularly true for research on its private sector portfolio. Indeed, this paper is one of the first that looks specifically at the GCF private sector portfolio including adaptation and mitigation projects and it is the first one to do so from a broader development perspective. Private sector engagement is not just seen in the narrow context of project or portfolio evaluations but in the context of established principles of effective development cooperation. Most previous studies on the GCF have focused on its creation process (Abbott & Gartner, Citation2011; Bracking, Citation2015; van Kerkhoff et al., Citation2011) or its institutional set up (Horstmann & Hein, Citation2017; Kalinowski, Citation2020; Lan, Citation2018; Pauw, Citation2015). A few articles have focused on GCF financing (Cui et al., Citation2020; Cui & Huang, Citation2018; Markandya et al., Citation2015) and the challenges arising from the withdrawal of US funding during the administration of US-President Trump (Bowman & Minas, Citation2019). Others focused on GCF principles such as country ownership (Zamarioli et al., Citation2020) or critically reflect on the discourses about ‘transformational change’ within the GCF (Bertilsson, Citation2021; Bertilsson & Thörn, Citation2021). As many GCF projects are still in the early stages of preparation or implementation, the available data is limited and thus very few papers have so far looked at the GCF project portfolio itself. Amighini et al. (Citation2022) offer a quantitative empirical analysis of the whole GCF portfolio, but they limit themselves to identifying funding patterns and fall short of investigating broader characteristics of GCF projects. Omukuti et al. (Citation2022) highlights the shortcomings of adaptation projects while Chaudhury (Citation2020) focuses on the role of accredited entities as intermediaries. Only Stoll et al. (Citation2021) offer an analysis of the private sector project portfolio, but limit themselves to the adaptation portfolio. Other studies on the broader mobilization of the private sector for climate finance lack a focus on the GCF (Pauw, Citation2015; Pauw et al., Citation2016; Pauw et al., Citation2022). Beyond the academic literature there is, however, a substantial amount of ‘grey literature’ on the interaction of the GCF with the private sector by civil society organizations (FS UNEP Centre, Citation2023; Okamoto & Zúñiga, Citation2022; Reyes & Schalatek, Citation2021, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Transparency International, Citation2022) as well as the GCF’s own Independent Evaluation Unit (GCF IEU, Citation2021). Grey literature has not gone through an academic peer review process but is often much more up to date and offers valuable perspectives from authors with an intimate knowledge of the topic stemming from their direct involvement in GCF activities, for example as civil society observers.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the methodology. Sections 3–5 present and discuss the results of the research. Section 3 lays the institutional groundwork by analysing goals and rules of GCF private sector engagement. Section 4 investigates the actual private sector portfolio and compares it with the goals. Section 5 puts the GCF private sector portfolio into a broader perspective by first comparing it with public sector projects and then by evaluating it with the benchmark of established principles of effective development cooperation.

2. Method

Given the limited amount of existing academic literature in this field, the paper follows a qualitative exploratory approach in which problems and pathways for future research are identified. For this exploratory approach a mixture of literature review, study of original documents and interviews has been used. The research develops this approach in four steps that combines an institutional approach with comparative elements.

First, we lay the foundation of our analysis by providing a review the institutions of GCF private sector engagement by reviewing the relevant statutes and publications of the GCF (Section 3 ‘the goals’). Most importantly, this section extracts the key elements of the GCF’s private sector strategy from official documents such as the UNFCCC’s decision on launching the GCF (UNFCCC, Citation2011) which includes the GCF’s Governing Instrument as an annex (GCF, Citation2011); the GCF’s Initial Investment Framework (GCF, Citation2014b), the Updated Strategy Plan (USP) (GCF, Citation2020) and the GCF board decisions on the Private Sector Strategy (GCF, Citation2022h) and its review (GCF, Citation2022i).

In the second step, we explore the GCF’s private sector portfolio, using project data from GCF (see below), and compare it to the goals (Section 4 ‘limits and problems’). A more thorough analysis and description of GCF projects is carried out in a third step, which includes a comparison of GCF private sector and public sector projects (see Section 5 ‘comparing public and private sector projects’). This allows us to gain a better understanding of the specific characteristics of private sector projects compared to the more traditional public sector projects. Finally, in this step of the analysis also covered in Section 5, 42 GCF private sector projects are evaluated according to the GCF’s own standards as well as the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) principles. The four main GPEDC principles are country ownership focus on results, inclusive partnerships, and transparency (GPEDC, Citation2023). These GPEDC principles are a suitable benchmark because they allow us to evaluate private sector engagement according to international principles of North–South cooperation. The GPEDC principles were agreed upon by 161 countries both from the Global North and the Global South. Thus, these principles are not just standards that donors set for the use of funding but have been agreed by donors and recipients alike. This makes them a suitable benchmark for our purpose to assess the broader implications of GCF projects. Thus Sections 4–5 cover the core of the data analysis for this paper.

The data for analysing GCF projects comes from the open data library database of the GCF (https://data.greenclimate.fund) as well as the GCF project reports (https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects). The analysis includes all 200 GCF projects that were decided upon by September 2022.

To complement the literature review and data analysis, and in order to provide context for the research, 18 semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were conducted with experts, GCF staff, private sector representatives, civil society groups, and nationally designated authorities (NDAs). These interviews were conducted in the period from December 2022 and February 2023. They include 1 interview with GCF staff, 2 interviews with private sector representatives, 3 interviews with NDAs and government officials, 4 interviews with experts and 8 interviews with civil society representatives.

Board meetings from November 2019–July 2022 were observed both in person at the GCF headquarters in South Korea as well as online.Footnote1 The purpose of the interviews and the attendance of board meetings were not primarily to generate new data, but to provide context for the document review and data analysis.

3. The GCF and the private sector: the goals

Mobilizing financial resources from the private sector engagement is an important priority for the GCF, particularly as developed countries fall short of their commitments to provide public climate finance to the Global South. Colenbrander et al. (Citation2021), for example, calculated that the US has just reached 4% of its fair share of USD 43 billion through public climate finance. Large parts of the promise at the Copenhagen summit in 2009 to mobilize USD 100 billion annually for climate projects in the Global South would have to come from the private sector. According to the GCF, the

climate crisis is too big, too serious and too urgent to rely on the resources of public institutions alone. Today, the private sector manages more than USD 210 trillion in assets but only a very minor part of it is dedicated to climate investments. (GCF, Citation2022g)

The systematic inclusion of the private sector as an institutional innovation in which the GCF has gone much further than any other comparable intergovernmental organization such as the IMF or the World Bank (Kalinowski, Citation2020). Compared to other international organizations, the GCF takes cooperation with the private sector to a new level, aiming to ‘maximize fund-wide engagement with the private sector’ (GCF, Citation2014a, p. 62). In the GCF, the private sector is not merely seen as an executor of publicly funded projects but is supposed to be included directly in the design, in the financing, and in the implementation of projects. The GCF Board includes four ‘active observers’ of which two come from the private sector and two from civil society groups. Following the principle of parity between donors and beneficiaries on the Board, one active observer comes from a developing country and one from a developed country. While there is a broad scope of private sector involvement in the GCF, there is a clear priority on mobilizing private financing. The ‘GCF’s private sector strategy focuses on mobilizing institutional finance and private capital at scale to invest in developing country financial institutions, local capital markets, projects and enterprises in climate adaptation and mitigation’ (GCF, Citation2022i). This priority is reflected in the GCF’s four-pronged approach of its private sector strategy, with the goal to (GCF, Citation2022h):

Promote a conducive investment environment for combined climate and economic growth activities.

Accelerate innovation for business models, financial instruments and climate technologies.

De-risk market-creating investments to crowd in private climate finance.Footnote2

Strengthen domestic and regional financial institutions to scale up private climate finance.

At the same time, the mission of the GCF private sector facility (PSF) goes far beyond mobilizing and scaling up private climate finance to the Global South. The PSF policy guidelines clearly state that maximizing co-financing should not be a ‘stand-alone target’ because ‘this may disincentivize GCF from financing projects/programmes with strong impact potential and high paradigm shift potential’ (GCF, Citation2019). Indeed the GCF mandate clearly states that the PSF should have a strong focus on country ownership and ‘promote the participation of private sector actors in developing countries, in particular local actors, including small- and medium-sized enterprises and local financial intermediaries’ (UNFCCC, Citation2011). In its Updated Strategy Plan (USP), the GCF acknowledges shortcomings in engaging private sector partners in developing countries and highlights the importance of ‘strengthening capacity’ among local partners ‘including supporting climate-oriented local financial systems, green banks, markets and institutions’ (GCF, Citation2020). Indeed, the tension between maximizing private climate financing to the Global South and enabling the paradigm shift to sustainable development in the Global South runs throughout the work of the GCF, as we will see throughout the following sections.

4. The GCF and private sector engagement: limits and problems

4.1. The definition problem

Mobilizing private financial resources is the key rationale behind the GCF’s private sector engagement. However, the GCF lacks a clear definition of what constitutes a private sector project and private sector engagement (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. 9). Within the GCF all projects managed by the PSF are characterized as private sector even if they include mostly public funding or are implemented by a public accredited entity (AE). An AE is a public or private sector institution that is accredited with the GCF and thus is qualified to apply for and manage projects.

provides a list of public and private sector AEs involved in GCF private sector projects. So far, all seven private sector AEs that are involved in GCF projects come from the financial sector, including five banks and two investment companies. Often the PSF matches project initiators with a private or public entity already accredited with the GCF (GCF, Citation2022g). This initiator does not necessarily have to provide financing directly or become the AE that oversees the project. In fact, as we will see below, many formally private sector projects include substantial public financing and are implemented by public AEs. At the same time, private sector engagement in the GCF can take many different forms and shapes (Stoll et al., Citation2021). Even exclusively public projects such as infrastructure improvements can involve the private sector, for example, as implementing partners. Moreover, public sector projects can create a paradigm shift and be transformative for the private sector. For example, by improving the electrical grid infrastructure, governments can provide access to renewable energy for private businesses.

Table 1. Categorization of all accredited entities currently involved in private sector projects (as of September 2022).

4.2. Lack of investment by the private sector

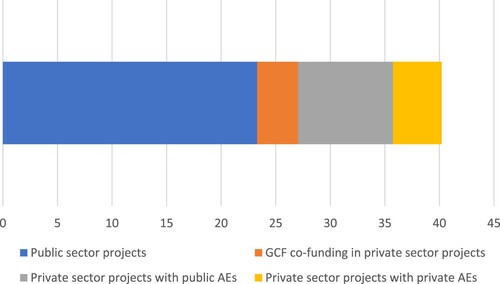

To date, despite the GCF’s effort to engage with the private sector, there is relatively little interest by the private sector in initiating and co-financing GCF projects. In September 2022, there were 47 approved private sector projects (out of 207). Five of these 47 projects have lapsed and are no longer under implementation, which is a much higher rate of failure compared to public sector projects where only two out of 160 public sector projects have faltered. This leaves 42 private sector projects (out of 200) with a volume of USD 16.9 billion (out of USD 40.2 billion in total GCF funding). This means 21% of all projects (by number) and 42% of all GCF project funding are in private sector projects (GCF, Citation2022g). While this looks substantial at first sight, 22% (USD 3.74 billion) of the total volume of USD 16.9 billion invested in private sector projects are funds provided by the GCF itself; the remainder comes from other largely public entities, such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and other regional or national development banks (see ). In other words, much of GCF’s private sector project financing is not coming from the private sector but from public sources. An important characteristic of these private sector projects is that many of them are focused on large mitigation projects while smaller projects tend to lack access to co-financing (Gruening et al., Citation2020).

Figure 1. Approved GCF portfolio by composition in billion USD, Source: Own calculations based on GCF (Citation2022d). ‘GCF Open Data Library’ from https://data.greenclimate.fund.

In a similar way to most private sector projects, public institutions and not private businesses act as the AEs that oversee the application and implementation process of GCF projects. Among the private sector portfolio, only 17 out of 42 projects, representing USD 4.46 billion of co-funding, are implemented by private AEs, while another USD 8.7 billion of co-financing for projects in this portfolio are implemented through public AEs (see ).Footnote3

In some projects that are categorized as private sector, the involvement of the private sector financing is rather vague and there is no, or little, private financing committed at the time the project is approved. For example, project FP25 ‘GCF – EBRD Sustainable Energy Financing Facilities’ implemented by the EBRD has the objective of ‘scaling up private sector climate finance.’ It does so not by mobilizing private finance directly, but rather indirectly by developing and demonstrating ‘efficient and effective financing mechanisms for energy efficiency and renewable projects’ and ‘new business models designed for industrial, corporate and residential clients’ (GCF, Citation2017, p. 14). In other private sector projects implemented by investment funds such as the ‘Global Fund for Coral Reefs Investment Window’ (FP 180) managed by Pegasus Capital Advisors or the ‘Arbaro Sustainable Forestry Fund’ (FP 128) the promise is to raise money on private capital markets. Thus, a private sector project approval does not mean that private investors are already committed to invest. Geary and Schalatek (Citation2022) criticize that leverage promises for private equity investments are ‘inflated and unverifiable.’ They are particularly concerned that the GCF approves projects without stipulating public accountability for meeting the leverage promises (Geary & Schalatek, Citation2022, p. 27). As equity investments carry a particularly high risk, raising capital is particularly difficult and often takes a long time. Consequently, in most projects like this, it is still too early to say how much financing will come from private sources, as the projects are still in early stages of preparation or implementation.

As mentioned above, while private financing takes up much of the attention in the GCF, private sector engagement can take different forms. Unfortunately, the promises of engagement in the funding of proposals often remain vague. Focusing on adaptation projects, Stoll et al. (Citation2021) distinguish four levels of private sector engagement in 74 adaptation projects ranging from: the private sector as an implementation partner (38 projects); the mobilization of private sector engagement (29); co-financing (9); and exclusive private co-financing (2). In other words in only 11 out of 74 (15%) of all adaptation projects does the private sector provide financing, while in 77% of these adaptation projects the private sector is an implementation partner or more vaguely engages ‘as an actor that is actively incentivized to support the project implementation through subsequent activities or opportunities’ (Stoll et al., Citation2021).Footnote4

4.3. GCF internal barriers to private sector accreditation and project approval

A major issue for the private sector in the GCF is the accreditation process for an entity to become an AE, which entitles the AE to directly apply for and implement projects. The accreditation process is mandated by the GCF Board; it is important to ensure that AEs are aligned with the goals of the GCF and have the capacity to successfully implement projects (GCF IEU, Citation2020). As the GCF spends the money of member countries, such scrutiny is necessary to prevent scandals that may undermine the legitimacy (and replenishment) of the GCF.

The problem is that small companies find it difficult to fulfil all requirements of the accreditation process, which is a problem not limited to the private sector but also for small civil society organizations (CSOs) and even public institutions. As the GCF's Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU) points out, the ‘GCF’s accreditation process is perceived as too lengthy and too cumbersome to secure the accreditation of private sector entities, especially for direct access entities (DAEs)’ (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. xix). DAEs are public and private entities based in the recipient countries in the Global South; DAEs are specifically prioritized for support in the GCF statutes. In practice, however, this prioritization of DAEs does not translate into a strong support for local actors to get accreditation nor in empowering already accredited DAEs to engage with local actors in their country (Omukuti et al., Citation2022). Based on a perception survey and interviews with stakeholders the GCF’s own Independent Evaluation Unit came to the conclusion that the accreditation process

has not yet resulted in a portfolio that is in line with the priorities and mandate of its private sector approach, taking into account dimensions of country ownership, local private sector involvement and supporting the needs of developing countries, particularly LDCs and SIDS. (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. xviii)

Larger businesses from the Global North have different reasons to hesitate in getting accredited, as they are reluctant to expose themselves to the scrutiny of an accreditation process. For example, the Korea EXIM Bank withdrew its application for accreditation, despite strong support from Board members from the Global South, after protests by civil society groups that criticized the bank’s involvement in exporting coal-fired power plants (Mathiesen, Citation2016).

The long time it takes for project approval in the GCF is another reason for lack of private sector interest. On average a private sector project needs 228 days from funding proposal submission to approval by the GCF board compared to 200 days for public sector projects (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. 44). Unlike for the public sector these long application periods are particularly problematic because they mean that it takes longer for projects to generate a financial return. In the view of the GCF’s own IEU, both the process and duration of the application process are ‘unattractive for the private sector and considered unpredictable, which presents significant barriers, even for large international accredited entities (IAEs)’ (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. xix).

4.4. Transparency, civil society, and private contracts

In addition to these internal barriers, there are more fundamental reasons for the hesitation of private businesses to get involved in GCF projects. As suggested above, for the case of the Korea EXIM Bank accreditation, rules on transparency and civil society in the GCF play a role in the reluctance of the private sector to get involved. Transparency and civil society participation are core principles of the GCF and are seen as important factors for successful projects; and these notions and their meaning are stipulated in the GPEDC principles. According to a comparative analysis of climate funds conducted by Transparency International (Citation2022), the GCF is doing comparatively well on most accounts of transparency, with the notable exception being the control of lobbying and a lack of transparency in its relations with implementing entities. For example, unlike the World Bank’s Global Environment Facility, the GCF does not require full disclosure of contracts with implementing agencies; and it does not require them to provide information on the effectiveness of their information disclosure and conflicts of interest (Transparency International, Citation2022). The GCF’s own IEU has found that the quality of reports provided by AEs varies substantially, to the degree that the GCF is left ‘with limited oversight over AEs’ compliance, especially for multi-country projects’ (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. xix).

To ensure transparency of project implementation, the GCF relies on a redress mechanism and continuous monitoring by local civil society groups. The GCF independent redress mechanism (IRM) allows stakeholders that are negatively affected by GCF projects or want to protest the rejection of a project by the GCF Board to file a complaint (GCF, Citation2022c). A continuous scrutiny by local civil society groups can help to keep track of projects outside the evaluation periods. Local groups can voice their concerns directly through the IRM and/or indirectly through the two active civil society observers on the GCF Board. In fact, the two active observers have been very active in GCF Board meetings and provided valuable information to Board members both directly through their own contributions or by requesting responses from the secretariat (Bruun, Citation2018).

However, transparency and civil society scrutiny almost by definition has its limits when it comes to private contracts with private sector entities (Kalinowski, Citation2020, p. 9). Private sector entities generally see information related to their business as proprietary, which creates a tension between the goal of transparency and the goal of attracting the private sector. The GCF has made a clear decision to prioritize private sector engagement and generously applied non-disclosure exemptions. In practice, this turns the ‘“presumption to disclose” into a de facto “presumption to not disclose” for private sector activities’ (Reyes & Schalatek, Citation2021, p. 15). Theoretically, active CSO observers could play an important role to ensure that confidential contracts do not include clauses that undermine GCF objectives and/or share risks between the GCF and private investors in an unfair way. However, CSO access to privileged information is limited. While their participation in public board meetings is guaranteed, their attendance in non-public meetings is much more limited. According to GCF rules (GCF, Citation2013b) active observers ‘may attend’ non-public committee and working meetings but only ‘in special circumstances and if expressly authorized by the Board.’ Even if civil society observers participate in non-public meetings they shall

not disclose, both during and after their term of office, information obtained from the Fund and/or project participants that is marked as proprietary and/or confidential, without the written consent of the Fund and/or the provider of the information, except as otherwise required by the law.

5. The GCF and private sector projects: biases and side effects

5.1. Comparing public and private sector GCF projects

To discern the specific characteristics of private sector projects it is useful to compare them with the more traditional, public-sector projects. As we have already seen above, the distinction can be ambiguous, as many private sector projects do include substantial public financing. Comparing the characteristics of private and public sector projects in the GCF, however, reveals important differences (see ). As we will see in more detail below, unlike public projects, private sector projects are heavily biased towards mitigation (64% of all projects) and largely neglect adaptation (12%).Footnote5 When it comes to projects in vulnerable countries on the other hand, private sector projects take a slight lead with 69% of them including particularly vulnerable African countries, least developed countries (LDC), and small island developing states (SIDS) compared to 65% of public projects (see discussion below). At the same time, private sector projects do not seem to reach vulnerable groups within recipient countries; for example, the GCF project data show that only 17% of the beneficiaries are women compared to 31% in public sector projects. Private sector projects focus on scale and scope and are less targeted and localized than public sector projects (see discussion on the consequences of large multi-country projects for country ownership below). With an average project size of USD 400 million, they are on average four times bigger than public sector projects. They also involve on average 6.3 countries while public sector projects are much more focused and operate in only 1.6 countries on average.

Table 2. Public and private GCF projects in comparison.

When it comes to GCF financing there are equally stark differences, as more than half of GCF financing in public sector projects consists of grants while in private sector projects loans and equity dominate (see ). The focus on the use of loans and equity is expected as the private sector is focused on revenue creation and commercial viability of projects.

Figure 2. Comparing GCF financing in public and private sector projects (billion USD). Source: GCF (2022). ‘GCF Open Data Library’ from https://data.greenclimate.fund.

In sum, private sector projects focus on large multi-country mitigation projects that generate revenues, while neglecting climate adaptation projects. In other words, private sector engagement creates a certain bias in the GCF portfolio, as we will see in more detail in the following sections.

5.2. Mitigation bias and lack of business model for adaptation projects

Many of the thus far described limitations and diverse biases of private sector projects can be explained by the tension between the fundamental goals of the GCF on the one hand, and the rationale of the private sector on the other. The GCF’s fundamental goal is to contribute to the final public good of successful climate mitigation and adaptation, while the primary purpose of any private sector engagement is to boost revenues and profits from selling private goods. Successful climate adaptation and mitigation are public goods because nobody can be excluded from their benefits. As nobody can be excluded from the benefits of mitigation and adaptation, businesses cannot charge the beneficiaries for the usage although they can charge for the creation of intermediate private goods such as renewable energy. Thus, private goods can indeed contribute to the creation of final public goods, but they only do so as an externality and not out of their own logic. Consequently, the challenge for the GCF in terms of private sector engagement is to help develop profit-oriented projects that produce climate mitigation and adaptation as a positive externality, or to find ways to make private investors benefit financially from these externalities (Pauw et al., Citation2022).

The reason why GCF private sector projects have a strong mitigation bias (see ) is that for many mitigation projects such business models already exist. And within GCF mitigation projects, it is those sectors with well-established businesses, such as renewable energy production and distribution, where private sector activity is concentrated (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. xix). In the future, external factors such as stricter regulations on CO2 emissions and the possibility of selling carbon credits generated through GCF climate mitigation projects, could be an additional incentive for private sector actors to invest in mitigation projects. This is particularly true if other institutions, such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) or similar market-based schemes, are strengthened in the future (Mikolajczyk et al., Citation2016).

The GCFs de-risking strategy does not work very well in adaptation projects as risk is not the main problem, but the general prospect of future returns is. Investments in solar or wind energy are associated with tried and tested business models, but such a perspective is far less obvious for adaptation projects. A company building levees against rising sea levels cannot charge those businesses or households protected by the levees, and an investor moving infrastructure such as a road to higher ground would find it difficult to, for example, charge a fee for a road that was previously used for free. So far, business models in the adaptation arena seem to be quite limited, with insurances being a rare example (Pauw et al., Citation2022), or protection of high value coastal real estate developments another (Bisaro & Hinkel, Citation2018). It is difficult to apply such business models widely in the Global South. While private sector involvement is seen as crucial for successful climate adaptation, its contribution to broadly financing climate adaptation in developing countries so far is limited (see also Pauw, Citation2015).

5.3. Private sector and vulnerable countries

The GCFs de-risking strategy seems to be more successful when channeling private funds to particularly vulnerable countries. As we have seen, 69% of all private sector projects include vulnerable countries which is slightly more than in the case of public sector projects (see ). This is surprising, as investments in LDCs are seen as riskier because these countries tend to have less favourable business environments compared to middle income countries and countries with ‘emerging market economies’. This is good news because GCF financing, at least for now, does not seem to have the problem of huge deadweight effects in which private investors take advantage of scarce public funds for projects that they would have carried out even without this support.

At the same time, it is important to note that the number of projects involving vulnerable countries might not be a good indicator for the actual engagement with these countries. This has to do with the character of private sector projects being designed and implemented as large multi-country projects. The more countries involved in a project the less they are adjusted to the specific situation of the recipients, the lower the share of transaction or overhead costs associated with the project. Of the 22 approved private sector projects in 74 vulnerable countries, only five are single country projects while the remaining are multi-country projects (GCF, Citation2022d). Private sector projects tend to follow a business logic of scale and scope. Given the profit-oriented logic of the private sector, it makes sense to have large multi-country projects if business models can be transferred across countries dealing with similar challenges, which in turn will lower relative overhead costs. This scalability and transferability also seems desirable from a climate perspective because it increases the impact of projects. At the same time large multi-country projects can be problematic from a development perspective.

5.4. Country ownership and private sector engagement

While a large scale and scope of projects is desirable from a business perspective, and from the perspective of the GCF goal of creating a large impact, such an approach can be problematic if it undermines the GCF goal of country ownership (Kalinowski, Citation2020). Country ownership is a core GPEDC principle aiming to ensure that any form of development cooperation is aligned with the development priorities of recipients, while using country systems for implementation (GPEDC, Citation2023). When GCF private sector projects prioritize scale and scope, as seen above, they will tend to be less aligned with the development priorities of individual beneficiary governments. In fact, the role of national government and the National Designated Authorities (NDAs) that serve as the interface between countries and the GCF are limited. While the NDAs have to sign a ‘no-objection letter’ (NOL) for each private sector project, this can be considered a very weak form of ownership. The half page long NOL merely states that the government does not object to the project and includes a very general statement that ‘the funding proposal is in conformity with the national priorities, strategies and plans’ (GCF, Citation2022f). According to the GPEDC, for example, country ownership not just means conformity but rather requires that partners aligned their support with national priorities (GPEDC, Citation2023). Even when projects are aligned with national priorities on paper, the capacity of NDAs to ensure alignment differs substantially among recipient states (Zamarioli et al., Citation2020) and is much weaker in the implementation phase than in the approval phase (GCF IEU, Citation2019).

However, from a development perspective, ownership ideally does not just mean alignment but that projects are initiated and driven by stakeholders in recipient countries and embedded in national development plans. If we have learned anything from successful developing countries of the past, such as South Korea and China, it is that they had strong national development plans in which foreign aid, but also foreign investment was embedded. Aid and investments were invited where they supported the national development plan but restricted where they were seen as potentially undermining development. The problem is that many developing countries, and in particular vulnerable countries such as LDCs, lack such a strong ‘developmental state’.Footnote6 They are struggling economically exactly because they do not have strong institutions to ensure that aid and private investments contribute to desired national development goals including the sustainable development that is needed now.

In the context of GCF climate financing, there is a certain trade-off between the (climate) goal of quickly raising large amounts of private finance for climate projects and the development goals to gradually create institutional frameworks for successful sustainable development. Development is not just about investments, but it is also institution building through a process that enables, guides, and regulates these investments. Without the institutions to ensure private investments are in line with development and climate plans, private investments can be more damaging than beneficial (see also Bertilsson & Thörn, Citation2021).

Country ownership is one of the core goals of the GCF but as the GCF IEU plainly states, the ‘GCF’s approach to private sector project development is not effectively country driven, and hence not in line with the priorities of the USP’ (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. xix). This is not just a problem because projects are not embedded in national development plans, but also for the engagement of the private sector within the Global South. The GCF has the goal to ‘promote the participation of private sector actors in developing countries, in particular local actors, including small and medium sized enterprises and local financial intermediaries’ (GCF, Citation2013a). However, most private sector projects are implemented by banks and funds based in the Global North thus not achieving this type of local engagement.

Only nine out of the 42 private sector projects are implemented by a national direct access entity (DAE) based in recipient countries. Of these nine projects, six are managed by private DAEs and three by public DAEs. Four out of the six private DAE projects are managed by a single bank in a single country, by the XacBank in Mongolia (GCF, Citation2022e). Furthermore, GCF project evaluations are not systematically linked to sustainable development goals and national monitoring systems, which in turn can further erode country ownership (GCF IEU, Citation2021, p. 56). In sum, despite the importance of country ownership, there is no systematic mechanism in the GCF to ensure that projects are country driven and evaluated according to their country ownership benchmarks, such as the contribution to national development and institution building.

5.5. Private sector financing and the danger of a climate finance curse

GCF private sector engagement can range from helping small farmers in LDCs to channeling massive investments into renewable energy projects. As we have seen, however, GCF private sector projects tend to focus on large scale projects in a few sectors. One of the potential dangers from this strong concentration is that private climate in a few sectors could hinder development in other areas leading to a ‘climate finance curse’ (Michael et al., Citation2015). Resource curse or ‘Dutch disease’ related effects, for example, can be observed when large investments in one sector of the economy undermines development in other sectors due to various effects ranging from exchange rate appreciations caused by capital inflow, labour force allocation and political lobbying. For foreign aid, this has been discussed in the context of ‘Dutch disease and foreign aid’ (Adam, Citation2013) but there is no reason to believe that climate finance would not have the same effect in particularly once scaling up of private finance is successful. There is at least the possibility that the blessing of private climate finance can turn into a curse similar to a ‘resource curse’ effect in natural resource extraction (Sachs & Warner, Citation2001). Investments in natural resource extraction tend to generate large profits but unlike investments in manufacturing or infrastructure they do not have many economic linkage effects to stimulate economy wide development. There is at least the danger that large renewable energy extraction projects might have similar effects, particularly if they do not improve domestic energy infrastructure but export the energy. Michael et al. (Citation2015) suggest various ways to limit negative effects of large inflows of finance to the Global South, but further potential problems arise from global financial market volatility and an increasing external debt burden.

The explicit goal of GCF private sector projects is to be scalable and develop business models that are viable for private investors without the support of the GCF. Despite the undeniable need for these large investments, we should not neglect the potential problems that such large financial flows could cause in the future. This is particularly true for large financial flows into LDCs that already have a high external debt burden and only small financial markets lacking proper regulation. Recent history is full of examples of financial crisis that followed the large inflow of financing into underdeveloped and underregulated markets – from the debt crisis of the 1980s to the Asian financial crisis of 1997/98 and Global financial crisis of 2008/09 that started in the subprime mortgage sector in the USA (Kalinowski, Citation2019). Susan Strange referred to international financial markets as the ‘manic depressive patient’ in which manic investment sprees are followed by a sudden panic and overly depressed assessment of certain markets (Strange, Citation1998). While private climate finance is currently still in a depressed state, it is important to prepare financial regulations for the potential manic phase in which vast amounts of private finance will be looking for investment opportunities.

When it comes to the long-term burden resulting from financial inflows, inflows of climate aid in the form of grants are the smallest problem for developing countries, as grants do not have to be repaid. This is different for loans and equity participations that dominate financing in private sector projects (see above). While initial Dutch disease related problems stem from the inflow of these investments, long-term problems arise from the repayment of loans and dividends. For example, private sector projects like Climate Investor One (FP99) or Desert to Power G5 Sahel Facility (FP178) are investing in renewable energy in countries in the Global South (GCF, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). The produced electricity will be sold locally in domestic currencies. The financing of this private sector project includes grants, loans, and equity participation. While grants will not have to be repaid, loans need to be paid back with interest in foreign currencies, which adds to the external debt burden of recipient countries and puts pressure on the local currencies.

One solution for limiting the debt burden is by concentrating climate finance not on loans but on equity participation. Equity investments are beneficial for countries in the Global South because they do not add to the debt burden of a country, and investors share the risks in the projects. If projects fail to generate revenues, investors do not receive dividend payments and if the project fails, they lose the capital (equity) they invested. Only if the project successfully generates revenues will equity investors receive dividend payments for the investments they have made. If the GCF succeeds in channeling large sums of private capital into successful projects in the Global South, that also means that these projects will lead to an outflow of dividend payments in foreign currencies; this in turn would put pressure on the local currency. In addition, equity participation means managerial control exercised by shareholders and/or the investment funds managing the equity participation. Ultimately, such operations increase the danger that substantial parts of sustainable industries in the Global South, and in particularly in small developing countries and LDCs, end up under the control of foreign investors. This would be particularly problematic in strategic sectors such as renewable energy. Although the problem right now is the lack of interest by the private sector in climate finance in the Global South, we should not ignore the potential downsides of large scale, foreign private sector climate finance once interest eventually materializes. Once the GCF goal of a paradigmatic shift is achieved and self-propelled private climate investments are flowing in the Global South, a market dynamic could emerge for which institutions in developing countries are not yet prepared. There is little reason to believe that the Global South’s problem of weak institutions, unstable financial markets, and economic domination by the North is going to vanish just because investments are now made in desirable climate projects such as renewable energy, rather than the undesirable exploitation of fossil fuels and other natural resources.

6. Conclusions

This paper has found many shortcomings and problems in the GCF’s strategy and practices to engage the private sector. First, there is a mobilization problem that concerns not just the GCF but is a general issue. It is extremely difficult to mobilize private capital for highly risky investments in climate projects in the Global South, even if governments or international organizations like the GCF try to mitigate these risks. Second, there are strong tradeoffs between private sector mobilization and the GCF goals as well as GPEDC principles of country ownership, transparency, and civil society participation. It is by nature of the private sector that contracts and business models should remain private and thus confidential in order to maximize the benefits gained from the investment. Consequently, there is the dilemma that strong transparency and reporting standards might reduce the mobilization of capital – at least in the short run. Third, private sector projects have a strong mitigation bias, upsetting the sought after balance of adaptation and mitigation projects within the fund. While the private sector has found ways to run profitable mitigation projects, this is so far not the case for adaptation. Fourth, while the GCF is successful in channeling funds to particularly vulnerable states, these projects tend to be large multi-country projects with weak country ownership. From a (sustainable) development logic, country ownership is crucial as it ensures that projects are embedded in national development strategies. Private sector projects, however, follow a profit logic of large, scalable, and transferable projects that are controlled by investors. Fifth, the desired massive expansion of private climate finance potentially risks adding to the already high external debt burden in the Global South, further destabilizing financial markets and exacerbating economic dependency.

All the above limitations and problems do not generally speak against private sector involvement in climate finance. Once clear rules and mechanisms to avoid and mitigate the above-described downsides are established within the GCF and other funds and financial markets more broadly, the described problems and tradeoffs can be reduced. Extreme caution, however, is needed to counter the view that private sector involvement would be an easy way out of the constraints of public finances when it comes to tackling the climate crisis in the Global South. Rather it is important to have a realistic view of private climate finance, one that sees not just the potential of vast financial resources from global financial markets, but that also identifies and finds solutions for the problems associated with private sector engagement. Further empirical research of GCF private sector projects and private climate finance in general is needed to get a better and more concrete understanding of their strengths and weaknesses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The board meeting on November 12–14, 2019 was attended in person as an accredited passive observer. The remaining board meetings were observed online. (https://www.greenclimate.fund/boardroom/meetings).

2 In the GCF de-risking refers to a strategy to mobilize private finance by reducing the risks investment, for example by using public finance (blended finance).

3 The GCF does not provide a detailed distinction between the private and public sector in project co-financing. We thus categorize co-financing as public if the AE is a public institution. Please find a list of our categorization of the accredited entities in .

4 The remaining six projects are either purely public projects or not categorized by Stoll et al. (Citation2021).

5 The remaining are cross cutting projects that combine mitigation and adaptation.

6 See for example literature on the East Asian developmental state, which is vast. For a first overview, see Johnson (Citation1995); Kalinowski (Citation2015); Thurbon (Citation2016); Woo-Cumings (Citation1999).

References

- Abbott, K. W., & Gartner, D. (2011). The Green Climate Fund and the future of environmental governance. Earth System Governance Working Paper (16).

- Adam, C. (2013). Dutch disease and foreign aid. In The new Palgrave dictionary of economics (Vol. 7). London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2864-1.

- Amighini, A., Giudici, P., & Ruet, J. (2022). Green finance: An empirical analysis of the Green Climate Fund portfolio structure. Journal of Cleaner Production, 350, 131383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131383

- Bertilsson, J. (2021). The Governance of Global Climate Finance–The Management of Contradictions, ambiguities and conflicts in the Green Climate Fund.

- Bertilsson, J., & Thörn, H. (2021). Discourses on transformational change and paradigm shift in the Green Climate Fund: The divide over financialization and country ownership. Environmental Politics, 30(3), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1775446

- Bisaro, A., & Hinkel, J. (2018). Mobilizing private finance for coastal adaptation: A literature review. WIREs Climate Change, 9(3), e514. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.514

- Bowman, M., & Minas, S. (2019). Resilience through interlinkage: The Green Climate Fund and climate finance governance. Climate Policy, 19(3), 342–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1513358

- Bracking, S. (2015). The anti-politics of climate finance: The creation and performativity of the Green Climate Fund. Antipode, 47(2), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12123

- Bruun, J. A. (2018). Climate changing civil society: The role of value and knowledge in designing the Green Climate Fund. In Sarah Bracking, Aurora Fredriksen, Sian Sullivan, & Philip Woodhouse (Eds.), Valuing development, environment and conservation (pp. 162–183). Routledge.

- Chaudhury, A. (2020). Role of intermediaries in shaping climate finance in developing countries—lessons from the Green Climate Fund. Sustainability, 12(14), 5507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145507

- Colenbrander, S., Cao, Y., Pettinotti, L., & Quevedo, A. (2021). A fair share of climate finance? Apportioning responsibility for the $100 billion climate finance goal. http://www.odi.org/en/publications/a-fair-share-of-climate-finance-apportioning-responsibility-for-the-100-billion-climate-finance-goal

- Cui, L., & Huang, Y. (2018). Exploring the schemes for Green Climate Fund financing: International lessons. World Development, 101, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.08.009

- Cui, L., Sun, Y., Song, M., & Zhu, L. (2020). Co-financing in the Green Climate Fund: Lessons from the global environment facility. Climate Policy, 20(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1690968

- FS UNEP Centre. (2023). GCF monitor. https://www.fs-unep-centre.org/gcf-monitor/

- GCF. (2011). Governing Instrument for the Green Climate Fund. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/governing-instrument

- GCF. (2013a). B.04/08: Business model framework: Private Sector Facility https://www.greenclimate.fund/decision/b04-08

- GCF. (2013b). Guidelines relating to the observer participation, accreditation of observer organizations and participation of active observers. Annex XII to decision B.01-13/03 https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/guidelines-observer-participation-accreditation.pdf

- GCF. (2013c). Terms of reference of the Private Sector Advisory Group https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/terms-reference-private-sector-advisory-group.pdf

- GCF. (2014a). Decisions of the Board – Seventh Meeting of the Board, 18-21 May 2014 (GCF/B.07/11). https://www.greenclimate.fund/documents/20182/24943/GCF_B.07_11_-_Decisions_of_the_Board_-_Seventh_Meeting_of_the_Board__18-21_May_2014.pdf/73c63432-2cb1-4210-9bdd-454b52b2846b

- GCF. (2014b). Initial Investment Framework. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/initial-investment-framework_0.pdf

- GCF. (2017). Funding Proposal FP25 “EBRD sustainable energy financing facilities”. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/ebrd-sustainable-energy-financing-facilities

- GCF. (2019). Policy on co-financing. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/policy-co-financing

- GCF. (2020). Updated Strategic Plan for the Green Climate Fund: 2020–2023. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/updated-strategic-plan-green-climate-fund-2020-2023.pdf

- GCF. (2022a). FP099 Climate Investor One. https://www.greenclimate.fund/project/fp099

- GCF. (2022b). FP178 Desert to Power G5 Sahel Facility. https://www.greenclimate.fund/project/fp178

- GCF. (2022c). GCF Independent Redress Mechanism (IRM). https://irm.greenclimate.fund/

- GCF. (2022d). GCF Open Data Library. https://data.greenclimate.fund

- GCF. (2022e). GCF Project Portfolio. Retrieved September 30, from https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects/dashboard

- GCF. (2022f). No objection letter template. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/no-objection-letter-template

- GCF. (2022g). Private Sector Financing. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sectors/private

- GCF. (2022h). Private Sector Strategy. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/private-sector-strategy.pdf

- GCF. (2022i). Review of the initial private sector facility modalities and the private sector strategy. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/gcf-b32-06.pdf

- GCF IEU. (2019). Independent evaluation of the Green Climate Fund’s Country Ownership Approach.

- GCF IEU. (2020). Independent synthesis of the GCF's Accreditation function. https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/evaluation/accred2020

- GCF IEU. (2021). Independent evaluation of the Green Climate Fund's approach to the private sector. Green Climate Fund.

- Geary, K., & Schalatek, L. (2022). Putting people and planet at the Heart of Green Equity. https://us.boell.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/Green%20Equity%20Updated.pdf

- GPEDC. (2023). The effectiveness principles. Retrieved April 13, from https://effectivecooperation.org/landing-page/effectiveness-principles

- Gruening, C., Pauw, P., & Zamarioli, L. H. (2020). Mobilising public and private co-finance.

- Horstmann, B., & Hein, J. (2017). Aligning Climate Change Mitigation and Sustainable Development under the UNFCCC: A Critical Assessment of the Clean Development Mechanism, the Green Climate Fund and REDD.

- Johnson, C. (1995). Japan, who governs?: The rise of the developmental state (1st ed.). New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Kalinowski, T. (2015). Crisis management and the diversity of capitalism: Fiscal stimulus packages and the East Asian (neo-)developmental state. Economy and Society, 44(2), 244–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2015.1013354

- Kalinowski, T. (2019). Why international cooperation is failing: How the clash of capitalisms undermines the regulation of finance (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198714729.001.0001.

- Kalinowski, T. (2020). Institutional innovations and their challenges in the Green Climate Fund: Country ownership, civil society participation and private sector engagement. Sustainability, 12(21), 8827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218827

- Lan, C. (2018). The challenges and opportunities for the Green Climate Fund. Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies, 06(01), 1875001. https://doi.org/10.1142/s2345748118750015

- Markandya, A., Antimiani, A., Costantini, V., Martini, C., Palma, A., & Tommasino, M. C. (2015). Analyzing trade-offs in international climate policy options: The case of the Green Climate Fund. World Development, 74, 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.013

- Mathiesen, K. (2016, October 14). Saudi Arabia blasts Korean bank for “playing” with UN climate fund. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2016/10/14/korean-export-bank-withdraws-climate-finance-bid/

- Michael, J., Jakob, M., Steckel, J. C., Flachsland, C., & Baumstark, L. (2015). Climate finance for developing country mitigation: Blessing or curse? (Vol. 7, p. 1).

- Mikolajczyk, S., Brescia, D., Galt, H., Le Saché, F., Hunzai, T., Greiner, S., & Hoch, S. (2016). Linking the clean development mechanism with the Green Climate Fund. Climate Focus, Perspective, Aera Group.

- Neufeldt, H., Christiansen, L., & Dale, T. W. (2021). Adaptation Gap Report 2020. UNEP.

- OECD-DAC. (2023). Official Development Assistance (ODA) flows for DAC and non-DAC members, recipients, and regions. https://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/aid-at-a-glance.htm

- Okamoto, T., & Zúñiga, M. (2022). The Green Climate Fund in Peru Indigenous organisations’ recommendations for improving safeguards. https://www.iwgia.org/es/documents-and-publications/documents/publications-pdfs/english-publications/650-iwgia-the-green-climate-fund-in-peru-eng-2022-1/file.html

- Omukuti, J., Barrett, S., White, P. C. L., Marchant, R., & Averchenkova, A. (2022). The Green Climate Fund and its shortcomings in local delivery of adaptation finance. Climate Policy, 1225–1240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2093152

- Pauw, W. P. (2015). Not a panacea: Private-sector engagement in adaptation and adaptation finance in developing countries. Climate Policy, 15(5), 583–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2014.953906

- Pauw, W. P. (2017). From public to private climate change adaptation finance: Adapting finance or financing adaptation? Utrecht University.

- Pauw, W. P., Kempa, L., Moslener, U., Grüning, C., & Çevik, C. (2022). A focus on market imperfections can help governments to mobilize private investments in adaptation. Climate and Development, 14(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.1885337

- Pauw, W. P., Klein, R. J., Vellinga, P., & Biermann, F. (2016). Private finance for adaptation: Do private realities meet public ambitions? Climatic Change, 134(4), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1539-3

- Reyes, O., & Schalatek, L. (2021). Green Climate Fund private sector finance in focus 1: A critical review of Key trends. Heinrich Boell Stiftung. https://us.boell.org/en/2021/10/05/green-climate-fund-private-sector-finance-focus-briefing-1-critical-review-key-trends

- Reyes, O., & Schalatek, L. (2022a). Green Climate Fund Private Sector Finance in Focus 3: Accreditation. Heinrich Boell Foundation. https://us.boell.org/en/2022/07/07/green-climate-fund-private-sector-finance-focus-briefing-3

- Reyes, O., & Schalatek, L. (2022b). Green Climate Fund, Private Sector Finance in Focus, Briefing 2: Micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). https://us.boell.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/hbs%20Washington_GCF-PrivateSector2_MSME%20briefing_final.pdf

- Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (2001). The curse of natural resources. European Economic Review, 45(4-6), 827–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00125-8

- Stoll, P., Pauw, W., Tohme, F., & Gruening, C. (2021). Mobilizing private adaptation finance: Lessons learned from the Green Climate Fund. Climatic Change, 167(3), 1–19.

- Strange, S. (1998). Mad money: When markets outgrow governments. University of Michigan Press. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/description/umich051/98034303.html

- Thurbon, E. (2016). Developmental mindset: The revival of financial activism in South Korea. Cornell University Press.

- Transparency International. (2022). Corruption-free climate finance: Strengthening multilateral funds. https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/corruption-free-climate-finance-strengthening-multilateral-funds

- UNFCCC. (2010). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its fifteenth session, held in Copenhagen from 7 to 19 December 2009, Addendum Part Two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its fifteenth session. https://unfccc.int/documents/6103.

- UNFCCC. (2011). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its seventeenth session, held in Durban from 28 November to 11 December 2011. Addendum Part Two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its seventeenth session. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2011/cop17/eng/09a01.pdf

- van Kerkhoff, L., Ahmad, I. H., Pittock, J., & Steffen, W. (2011). Designing the Green Climate Fund: How to spend $100 billion sensibly. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 53(3), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2011.570644

- Wang, B., & Rai, N. (2015). The Green Climate Fund accreditation process: Barrier or opportunity? International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Woo-Cumings, M. (Ed.). (1999). The developmental state. Cornell University Press.

- Zamarioli, L. H., Pauw, W. P., & Grüning, C. (2020). Country ownership as the means for paradigm shift: The case of the Green Climate Fund. Sustainability, 12(14), 5714. doi:10.3390/su12145714