ABSTRACT

Corporate carbon neutrality pledges have been criticized for their lack of integrity, especially when they are primarily based on the simple purchase of carbon offsets without making any significant emission reductions. Neutrality pledges that are consistent with the goal of the ISO corporate net zero guidelines should be based on the reduction of all but the so-called unavoidable or residual emissions. The residual emissions should be neutralized not through reduction offsets but by actually removing the equivalent amount of emissions from the atmosphere. In this paper, I analyze whether climate pledges of 115 large companies, which cover all eleven Global Industry Classification Standards’ sectors, follow the aforementioned net zero definition. The assessed criteria are (i) the type of pledge made, (ii) the definition of residual emissions employed and (iii) whether the company commits to neutralize its emissions exclusively with removals. Secondly, the assessment involves evaluating the companies’ commitment to their net zero pledges by examining the residual emission level provided and determining if their climate goal extends to absolute scope 3 emissions. From the companies that had a net zero target (69) only 22% aimed to reduce emissions to a residual level and compensate with removals. The residual emission levels in the target year is specified by 29 companies and ranges between 0 and 80% (mean = 19.3%, median = 10%, n = 29). More than half of the residual emissions that exceed the mean of 10% are claimed by sectors that are not classified as hard-to-abate such as information technology or communication companies.

Key policy insights

Corporate net-zero goals appear more ambitious than the reduction and compensation commitments that companies are making

Residual emission levels that determine the reduction obligations under a net-zero pledge should not be determined by corporates or technical experts alone

Involvement of governments and civil society actors in participatory processes at national and international level is needed to determine residual emissions

‘Fair contributions’ and thus residual emissions should be informed by companies’ impact on fulfilling the needs of the most vulnerable

1. Introduction

The climate crisis threatens human and non-human life, and this will continue at an unprecedented rate if the emissions of anthropogenic greenhouse gases are not drastically reduced. Through the Paris Agreement, the international community has collectively decided to keep global temperature rise well below 2 degrees by the end of the century, with a target of 1.5 degrees (UNFCCC, Citation2015). The aim is to achieve a balance between sources and sinks of greenhouse gases by 2050, laying the foundation for today’s concept of net zero. Therefore, both significant emission reductions and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) are needed (IPCC, Citation2022; IPCC et al., Citation2023). The IPCC (Citation2022) states that ‘CDR to counterbalance hard-to-abate residual emissions (e.g. [..] from agriculture, aviation, shipping, and industrial processes)’ is unavoidable but without specifying the exact sources and volumes of these emissions.

One challenge regarding residual emissions lies in the terminology. To aid the understanding of this paper, a definition of terms is provided in Table S1 in the supplementary material. While the emissions are called ‘unavoidable residual emissions’ in the German context, the IPCC referred to them as ‘hard-to-abate- residual emissions’. ISO (Citation2022) defines a residual emission as an emission that ‘remains after taking all possible actions to implement emissions reductions’ and ‘all possible actions’ here refers to ‘what is technically and scientifically feasible’. The SBTi et al. (Citation2020) defines residual emissions as emissions from a source ‘that remains unfeasible to be eliminated’. Fankhauser et al. (Citation2022) redefine net zero accordingly, stating that emission reductions need to be ‘front-loaded’ and comprehensive and that residual emissions must be neutralized with carbon removals. Those emissions that remain after all possible reduction efforts are called ‘residual’, ‘remaining’, ‘unavoidable’ or ‘hard-to-abate’ emissions. ISO distinguishes other emissions that remain from residual emissions, if a company has not managed to obtain reduction to a residual level. It specifies that if

other emissions remain, the organization should communicate progress towards specific emissions reduction targets to provide a transparent indication for the prospects of achieving net zero. If the organization counterbalances other emissions and meets relevant criteria, it may be able to make a claim of carbon neutrality on the path to net zero.

Within the integrated assessment community, sectors that are hard to decarbonize for technical reasons are industry, aviation and shipping, construction and agriculture and it is assumed that residual emissions will stem from these sectors (Edelenbosch, Citation2022; Luderer et al., Citation2018). The composition of residual emissions varies in the different integrated assessment models (Lamb, Citation2024). Schenuit et al. (Citation2023) argue that, currently, many actors conceptualize their emissions as ‘hard-to-abate’ or ‘unavoidable’ not for technical but rather political or strategic reasons and that the inherently political argument about what should count as ‘unavoidable’ emissions should be separated from the definition of residual emissions. This is why they suggest a redefinition of residual emissions as any emissions that ‘actually enter the atmosphere in and after the net zero year.’

The concept of net zero does not only exists in international agreements, but is taken up by states and companies as well. Voluntary net zero pledges have been made by 149 countries and 929 publicly listed companies (Net Zero Tracker, Citation2023). The pledges from companies often rely on Renewable Energy Credits (Bjørn et al., Citation2023) and offsetting (Arnold & Toledano, Citation2021; Trencher et al., Citation2023). Both voluntary and compliance carbon offsets have been criticized for lack of environmental integrity, non-permanence, non-additionality, negative social consequences, overestimated emission reductions and misleading consumers (Arendt et al., Citation2021; Asiyanbi, Citation2016; Böhm & Siddhartha, Citation2009; Carton et al., Citation2021; Kaupa, Citation2022; Probst et al., Citation2023; West et al., Citation2023). Despite the criticism, carbon offsets have remained persistent, leading some critics to label them a ‘zombie-solution’ (Asiyanbi, Citation2022) or even a mere ‘fantasy’ (Watt, Citation2021). Voluntary environmental claims such as ‘carbon and environmentally neutral’ that are reached through offsets for products will soon be prohibited in the EU (European Parliament, Citation2023). It remains unclear how this will affect companies’ pledges.

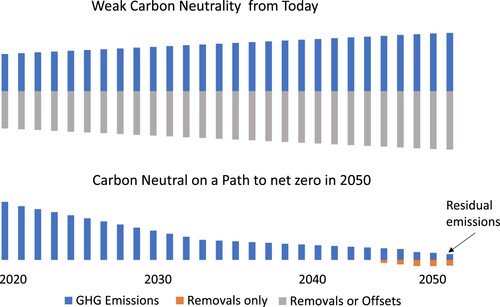

In response to criticism regarding offsetting and net zero, the mitigation hierarchy (avoid, reduce and only then compensate), which originates from conservation and waste management discourse, has now been transferred to carbon (Stevenson, Citation2020). The previously outlined redefinition of net zero by different actors (Fankhauser et al. (Citation2022), SBTi et al. (Citation2020) and ISO (Citation2022)) for the corporate context can be interpreted as a redefinition of carbon neutrality in line with the mitigation hierarchy. A carbon credit is no longer equivalent to reduction, but only a last resort for unavoidable, residual emissions. Furthermore, residual emissions must be balanced with carbon removal credits (for definition see Table S2 in the supplementary material). Offsets obtained by avoidance or reduction credits cannot be part of the net zero goal, as all sectors and countries have their own emission reduction pathway. All remaining sources must be balanced with sinks and not by reductions of others to claim net zero. shows the difference between carbon neutrality before and after its redefinition to net zero.

Figure 1. Illustration of the difference between weak carbon neutrality (upper graph) and a company on the path to net zero in 2050 (lower graph) in which emissions are reduced to a residual level and offset exclusively with carbon removal credits, adapted and modified from (SBTi, Citation2021).

Dena (Citation2022) differentiates between ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ carbon neutrality or net zero in line with a weak and strong definition of sustainability. Emission reductions and Paris compatibility are included in some corporate carbon neutral standards, but not all of them (Helppi et al., Citation2023). The lack of a standard definition of residual emission levels has led to inconsistent claims about residual emissions by countries and companies (Buck et al., Citation2023; Lund et al., Citation2023). The SBTi and ISO have given guidance on residual emission level at sectoral and cross-sectoral levels. The cross-sector level is 10% (SBTi et al., Citation2021), while the rest ranges from 0% (power sector) to 28% (forestry and agriculture) (International Organization for Standardization [ISO], Citation2022).

What counts as residual emissions is a matter of controversy. The German government calls only 5% of emissions unavoidable residual emissions (SPD et al., Citation2021), while the CEO of Man Energy solutions, a firm that invests in carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, claims that 30% of global emissions are unavoidable (et-Redaktion, Citation2022). Without a standard definition and thorough examination, there is a high risk that most countries and companies will claim that a considerable share of their emissions are residual emissions so as to postpone costly decarbonization. These residual emissions may not even be removed but instead tackled through reduction offsets. Furthermore, the ambitious commitment regarding removals in 2050 is a source of uncertainty, as the dimension and availability of removals in 2050 is not currently known and might possibly be too low to meet companies’ and countries’ pledges (Dooley et al., Citation2022; Lamb et al., Citation2024; Smith et al., Citation2023).

Several scientists have already assessed companies’ net zero pledges (Arnold & Toledano, Citation2021; Day et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b; Net Zero Tracker, Citation2023; Rogelj et al., Citation2021), but a systematic analysis with a focus on residual emissions and the underlying net zero definition has so far been lacking. To identify the extent of our reliance on future removals to meet corporate climate goals, it is essential to bring residual emissions to the centre of attention and specify how they should be defined and by whom. In what follows, I analyze corporate climate pledges with a focus on how they define residual emissions in comparison to the recently outlined standards and guidelines for net zero. I also include how companies quantify their residual emission level and whether they specify the origins of their emission.

The paper is structured as follows: after this introduction, the Method section outlines the criteria evaluation scheme and a strategy to sample companies. Then the Results are presented first in relation to the underlying Net Zero Definition and then with a focus on the Comprehensiveness of the pledge. Finally, the results are discussed in relation to this study's weaknesses, put into context with other research, and used to provide an outlook for future research and alternative possibilities for determining residual emissions. The paper then closes with a short conclusion.

2. Method

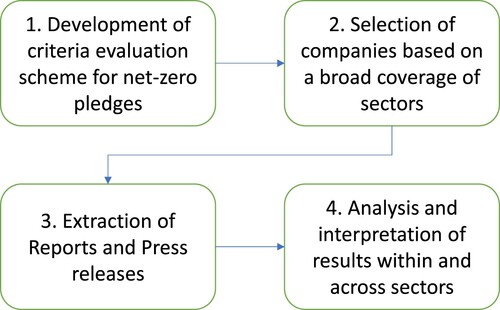

The method comprises four steps, which are shown in . First, a criteria evaluation scheme was developed based on existing criteria for climate pledges. Criteria that have already been assessed in previous evaluations include the type of pledge made, whether the company commits to using removals and whether it has a scope 3 target (Day et al., Citation2023a; Lang et al., Citation2023; Manier, Citation2023). I have complemented these with criteria that assess residual emissions. Moreover, I added the absolute scope 3 emission target to understand whether the residual emission level refers to the full scope of emissions.

The following outlines the criteria for evaluation and supporting questions:

Type of pledge: What type of climate related pledge does the company have?

o Possible answers: net zero, carbon neutral, other or none. If the pledge does not fit one category exactly, then it was assigned to the category closest to it. A full documentation of the pledges and original text can be found in the supplementary file 2.

Mentioning of residual emissions: Does the company mention hard-to-abate, residual, unavoidable or remaining emissions that cannot be reduced?

o Possible answers: Yes, no

Removals only: Does the company explicitly mention that it will only use removals to balance residual emissions?

o Possible answers: Yes, no. Expressing only a preference for removals over offsets is not enough to get a yes.

The following questions identify the comprehensiveness of the climate pledge:

Provision of residual emission level: Does the company provide a residual emission level in relation to its net zero target year? If yes, how high is the residual emission level?

o Possible answers: None provided, a residual emission level is provided in percent. This level can also be expressed as the remaining emission level that is still present in the target year without the term ‘residual emissions’ specifically being used.

Origin of residual emissions: Does the company specify from which processor product its residual emissions stem, or does it give another reason for its residual emissions?

o Possible answers: A qualitative description of the processes or products that causes residual emissions or some other justification is provided.

Absolute Scope 3: Does the company explicitly include absolute and full scope 3 emissions in its net zero target?

o Possible answers: Yes, no, partial, unclear.

In the second step, a strategy was developed to take a sample of companies covering a diverse range of industries. I decided to assess ten companies from each of the eleven sectors of the industry sector classification laid out in the Global Industry Classification Standard (MSCI, Citation2023). The eleven sectors are: energy, materials, industrials, consumer discretionary, consumer staples, health care, financials, information technology, communication services, utilities and real estate. The ten biggest companies by market capitalization in these eleven sectors were selected. The companies were extracted from the website Disfold (Citation2023) on the 2nd of August 2023, the values are based on the market capitalization from first of January 2023. They did not cover cement and only contained one fertilizer company. Since these industries are usually associated with hard-to-abate emissions, three cement and two fertilizer producers were supplemented, resulting in a sample of 115 companies.

In the third step, I collected information regarding the companies’ pledges from relevant reports. If the reports were not sufficient to answer all the questions, then the findings in the reports were complemented by press releases. All the information was obtained between the 2nd and 8th of August, 2023.

In the final step, the company information was interpreted using the criteria evaluation scheme. The analysis focused first on the criteria that examined the underlying net zero definitions being used and then shifted focus to the comprehensiveness of the pledges. The full list of companies, their geographical registration and documentation of the extraction date and assessed documents, along with the results of the criteria evaluation, is provided in supplementary material 2.

3. Results

The results section follows the same structure as the criteria and questions in the method section. In sub-section 3.1, the emphasis is on the net zero definition. This section elaborates on the companies’ pledges and their commitment to reduce emissions to a residual level and only use removals to compensate for them. The second section, 3.2, is dedicated to the comprehensiveness of the pledges regarding the provision of a residual emission level, the reason or process related to the residual emissions and the integration of scope 3 emissions into the climate pledge.

3.1. Net zero definition

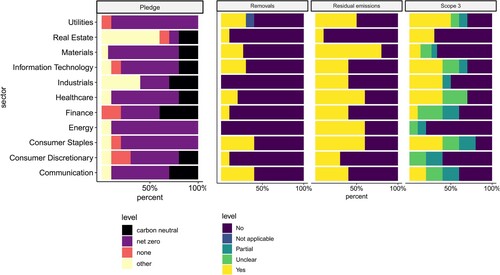

Most of the assessed companies have a net zero (69) or carbon neutrality (21) pledge, while 17 have a reduction target and 8 no target at all, which is shown in , for each sector. The sectors with the highest share of net zero pledges are the energy and utility sector (9/10), while the sector with lowest share is the real estate sector, where only one of the assessed companies (Prologis) has a net zero goal. In between these extremes are consumer staples (8/10), healthcare (7/10) and materials (11/15), information technology and communication (both 6/10), consumer discretionary (5/10), finance (4/10) and industrials (3/10).

Figure 3. The climate pledges of the different companies, if the companies committed to only using removals, mentioned residual emissions or not and if their climate pledge covered scope 3 emissions (from left to right).

Out of the 115 assessed companies, 55 mention residual emissions or an associated synonym, 46 of them made a net zero pledge, and the remaining nine have a carbon neutrality target. Referring to residual emissions is most common in the materials sector and least common in the real estate sector. As is evident in , companies from all eleven sectors mention residual emissions, not just those mentioned in the literature as hard-to-abate (heavy industry, buildings, agriculture, aviation, shipping and mining). The specific residual emission levels and the reasons provided for them are more thoroughly assessed in section 3.2.

The commitment to balance emissions exclusively with removals is less common compared with simply mentioning residual emissions. Of the 115 companies, 23 pledge to balance emissions exclusively with removals. Of these 23 companies, 18 have a net zero goal, while the remaining five commit to carbon neutrality. There is no clear pattern across the different sectors. One company (NextEra Energy Citation2022) aims to reduce emissions to zero without any removals. None of the sectors’ commitment to removals exceeds 50% of companies. In the industrials and energy sectors, no company aims to balance exclusively with removalse. The most ambiguous case in the energy sector was Equinor (Citation2022). It mentions the Oxford Offsetting Principles (Allen et al., Citation2020), and thus commits to phase out reduction offsets with removal offsets in the long run. However, since it does not state that it will balance remaining emissions with removals in its energy transition plan, it does not count as committing to removals only.

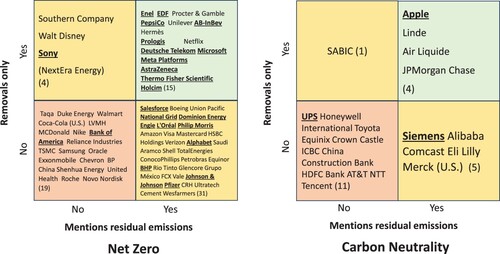

classifies the net zero and carbon neutrality pledges of the various companies according to their compliance to reduce to a residual level before they balance with removals.

Figure 4. Classifying companies with net zero and carbon neutrality pledges according to their mentioning of residual emissions and commitment to only using removals. Pledges that include absolute scope 3 emissions are underlined and bold.

Overall, 19 companies mention residual emissions and commit to removals. Of those, 4 have a carbon neutrality target and 15 have a net zero target. These companies are in the upper right corners of the two graphs in . Therefore, the removal target is more strongly connected to net zero with 27.5% of pledges than to carbon neutrality with only 23.8%.

The same is true for mentioning reduction to residual emissions: 42.9% of the companies that aim for carbon neutrality mention reduction to a residual level, while this is true for 66.7% of the companies that have a net zero target. This finding is in line with the fact that carbon neutrality is not clearly associated with emission reductions to a residual level. The ISO standard 14068 on carbon neutrality (International Organisation for Standardization, Citation2023) requires greenhouse gas reductions, but not to a residual level and therefore deviates from other net zero definitions (dena, Citation2022; Helppi et al., Citation2023; International Organization for Standardization [ISO], Citation2022).

The findings highlight that only 21.7% of the companies that have a net zero pledge followed the net zero definition as laid out in the corporate net zero guidelines. Most of these companies stem from consumer staples (4), followed by information technology, healthcare, communication and utilities (all 2). Real estate, materials and consumer discretionary have 1 company each. The companies can be identified on the left side of in the upper right corner. Only 8 of these companies provide a residual emission level (see section 3.2).

The quantitative and qualitative specification of residual emissions, as well as whether they also include scope 3 emissions, is analyzed in the following section.

3.2. Comprehensiveness

In the previous section, I showed that most companies have net zero or carbon neutrality pledges, but rarely commit to reducing their emissions as far as possible and then balancing the rest with removals. In what follows, I will focus on the comprehensiveness by presenting the proposed residual emission levels along with the reasons for them. The section closes with an assessment of whether companies include absolute scope 3 emissions into their pledge.

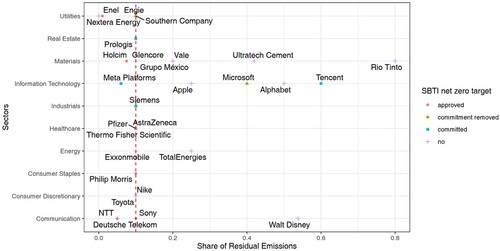

Of the 115 companies, 29 provide a residual emission level. Of those, 23 have a net zero target and 5 have a carbon neutrality target. The residual emission levels of the different companies are visualized in . The median of the levels is 10% and the mean is 19.3%. The median level of 10% is equal to the residual emission level provided by the SBTi in its cross-sector pathway (Citation2021).

Figure 5. Reported residual emissions of the different companies, the dashed line is equal to the mean and the recommended level by the SBTi for its cross-sector pathway.

Of the 15 companies with a net zero definition in line with net zero standards, 9 provide a residual emission level. All of these companies have a residual emission level that is under 10%, except from Microsoft. Rio Tinto, Ultratech Cement and TotalEnergies, which either produce cement or extract metals, mineral resources or fossil fuels, claim significant residual emission levels. However, IT corporations, including Microsoft, Tencent and Alphabet, also report having higher residual emissions than the average. The financial and industrial companies lack a quantitative specification of their residual emissions. Those companies that have a high residual emission level that exceeds 10% do not have an approved SBTi target. The companies with approved SBTi target, on the other hand, have residual emission levels equal to or below 10% of the emissions in their base year.

There are three main aspects that influence the ambition of the residual emission level: (i) whether the residual emission level refers to a product or to the whole company, (ii) whether the residual emission level refers to all scopes and (iii) what kind of activities are counted as an emission reduction.

Company or Product: Toyota’s and Holcim’s residual emission level refers only to their product and not the company as a whole. For Holcim, this applies only to scopes 1 and 2, because it has an absolute scope 3 target but a relative target for scopes 1 and 2. In absolute terms, the residual emissions of both companies may be higher or lower depending on the development of sales.

Scopes: Meta Platform’s residual emission level applies to scopes 1 and 2. Meta’s scope 3 target is to not increase in emissions in its target year. Its scope 3 emissions represent 99% of its total emissions (Meta Platforms, Citation2023). Therefore the residual emissions in the target year are 99%, as this is the emission level across all three scopes that they have committed to reach in their target year 2030 compared with today’s emissions. They have not published further emission reduction targets after 2030.

Emission removal, captured emission or reduction: The cement companies consider carbon capture and storage (CCS) as reduction. The residual emissions of Holcim are 5% for scopes 1 and 2 and 10% for scope 3. However, in the pathway they provided to achieve net zero for scopes 1 and 2, it is evident that the residual emissions reach 51% if CCS is not counted as an emissions reduction (Holcim, Citation2023). Neither a pathway nor a CCS rate is provided for Scope 3. The interpretation of CCS as a form of emission reduction is in line with the sector specific pathway for cement derived from the science-based targets, which specifies that

All decarbonization levers that lead to an emissions reduction in scope 1, 2 and/or 3 according to the SBTi Criteria and GHG Protocol accounting rules are valid. These may include “traditional” levers such as energy efficiency, fuel switching, reduction in clinker content, as well as breakthrough technologies such as carbon capture and permanent geological storage (CCS), bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), electrification or novel binders. (SBTi, Citation2022)

Having just focused on the quantitative specification of residual emissions, I now turn to the reasons provided for residual emission levels. The reasons given by the different companies, grouped by sectors, are listed in .

Table 1. Overview of companies that define residual emissions or link them to a certain process.

Only 26 companies provided a qualitative specification of their residual emissions. Of these, 13 refer to a general infeasibility and four of them claim additionally that they belong to hard-to-abate sectors. Just three companies invoked economic or affordability constraints for themselves or for consumers (Walt Disney, Philip Morris and Dominion Energy). Amazon and JPMorgan Chase relate their residual emissions to embedded emissions in buildings. TotalEnergies, Rio Tinto, Dominion Energy and the Southern Company consider the emissions from fossil energy carriers to be residual. Limited access to renewable energy is a reason for unavoidable emissions according to Alibaba and BHP. Only UltraTech Cement, Holcim, Vale and Rio Tinto mention process related obstacles for emission reductions. None of the companies that have agriculture in their supply chain (Walmart, McDonalds, all alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverage manufacturers, Nutrien and Wesfarmers) reported on process-related residual emission levels in agriculture. The feasibility of emission reductions in agriculture, especially in relation to livestock, is not elaborated on in the net zero reports, which leaves the residual emission level for agricultural products underexplored in this study. Only 9 companies linked their residual emissions to a specific process or product.

The sectors that frequently mention residual emissions but provide no detailed reasons for them aside from a general infeasibility are healthcare, finance and information technology. There is a discrepancy between the significant amount of residual emissions reported and the lack of any explanation for them, particularly in the IT sector. Although additional emission reductions may be achievable, there is a possibility that some companies in the healthcare sector use the 10% residual emissions figure as suggested by the SBTI, as they do not provide a source for the remaining emissions. The lowest residual emission level reported came from Enel at 1%, and the reason provided was upstream scope 3 emissions. This was also the only source provided by the National Grid that mentions air travel. Assigning residual emissions to specific sectors is complex due to interconnections within supply chains. Therefore, companies should specify where and in which process residual emissions occur, but most fail to do so. For example, none of the IT companies qualified the origin of their residual emissions in terms of a process or the origin, making it unclear if they stem from a hard-to-decarbonize sector in their supply chain.

In what follows, I discuss the coverage of absolute scope 3 emissions. Overall, 26 companies included absolute scope 3 targets that related to net zero or carbon neutrality pledges, which is shown by sector in . Most companies have a net zero target but only Alibaba, UPS and Apple cover scope 3 emissions and have a carbon neutrality goal. One of the 26 companies does not commit to absolute scope 3 reductions (Meta) but commits only to prevent its scope 3 emissions from growing further in its target year. There is a clear pattern across sectors: companies that are active in oil and gas did not account for absolute scope 3 emissions. The only company that claims to provide CCS for scope 3 emissions in oil and gas is TotalEnergies. However, based on the description in their report, it is unclear who should be held responsible for paying for the CCS, TotalEnergies or its clients. None of the corporations in the consumer discretionary sector specifically link their complete scope 3 emissions to their ultimate net zero goal. With the exceptions of Sony and Deutsche Telekom, the goals for communication technology companies are comparable in their omission of scope 3 emissions. While 4 consumer staples firms include scope 3 emissions in their net zero goals, only Philip Morris specifies its residual emission levels for this absolute aim, and the others might only attain their aim through a significant amount of removals. Holcim has an absolute scope 3 goal, but only a relative goal for scopes 1 and 2. Therefore, none of the cement companies account for absolute emissions across all three scopes. The only company in the assessed sample that ticks every box i.e. it uses the term net zero according to its definition in corporate net zero guidelines, has an absolute emission reduction target for all three scopes and specifies were its residual emissions come from is Enel. However, Enel’s climate goal has also been criticized, as Enel sells its coal power plants, rather than closing them down, meaning there might not be any actual emission reduction, but just a change in control over the carbon intensive infrastructure (Day et al., Citation2023b).

Resulting from a combined analysis of section 3.1 and 3.2 I identified that only five companies that use a net-zero definition that is in line with ISO, specify their emissions qualitatively (Enel, Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Meta Platform and Holcim). On the other hand, eight companies that use the ISO conforms net-zero definition specify their residual emissions quantitatively (Enel, Prologis, Deutsche Telekom, Microsoft, Meat Platforms, AstraZeneca, Thermo Fisher Scientific and Holcim). A specification of both the qualitative and quantitative information is provided by three companies (Enel, Meta Platforms and Holcim). All information regarding the pledges, analyzed documents and quotes that led to a decision in relation to a criterion are provided in Supplementary Material 2.

4. Discussion

This discussion first addresses this study’s weaknesses and its findings. It then moves on to compare these results in the context of other research and provides recommendation for future research regarding residual emissions. Finally, I address the constraints of corporate net-zero and climate neutrality initiatives in determining residual emissions and conclude with policy implications and recommendations.

A limitation of the study is related to the company and sector coverage. Some of the assessed sectors, such as the IT sector, are close to a monopoly or oligopoly. The assessed sample, therefore, represents these sectors quite well. Other sectors, such as cement production, construction and real estate, are less concentrated, so more of these companies would need to be assessed to have a representative sample. Some sectors are not yet covered in the sample, such as pulp and paper manufacturing and food production. To assess these sectors’ underlying residual emission definitions, additional studies are needed. For sectors such as constructions and housing, whose products are often owned by private households, the magnitude of residual emissions will be difficult to assess. A company sample would only represent corporate landlords, so another approach would be needed to assess all real estate. Furthermore, only reports in English were considered. Despite this limitation, the analyzed corporations are potentially the most influential ones due to their size. Therefore they might set a standard for smaller companies.

Another possible source of inaccuracy is the textual interpretation of the analyzed text resources. All the sources used are provided with the respective links in the supplementary file 2. The reports are often vague and avoid making strong commitments, which makes it challenging to extract precise information (Day et al., Citation2023b). For some of the companies (ExxonMobil, Tencent, Southern Company, NTT, Microsoft and Ultratech Cement), the residual emission level had to be interpreted from a graphical depiction of the reduction pathway. For the sake of transparency in the interpretation, I included a quotes section in my supplementary file, which contains the extracted text snippets that form the foundation for my classification of the companies according to the outlined criteria. A clear and standardized language and reporting scheme would ease the interpretation of climate pledges.

The analysis did not focus on all the necessary criteria for high ambition net zero targets, e.g. it did not assess the difference between carbon and climate neutrality (i.e. full coverage of GHGs), which is important because, companies could avoid the reduction of non-carbon greenhouse gas emissions (dena, Citation2022). This is covered by the net zero tracker (Lang et al., Citation2023). I also did not assess the near- and long–term goal alignment as suggested by Smith (Citation2021), which could be covered by a different assessment approach, one that assesses the residual emission budget.

Despite these sources of inaccuracy, the results of the analysis are largely in line with other literature that found the net zero pledges of companies to be of varying quality (Arnold & Toledano, Citation2021; Day et al., Citation2023b; Net Zero Tracker, Citation2023). Based on this examination, residual emissions across companies are not defined consistently, as has been previously outlined in relation to the use of residual emissions in the long–term strategies of countries (Buck et al., Citation2023). The level of residual emissions, with around 19.6% as the average level provided by companies, is also in the same range as the average residual emissions provided by Annexe I countries (18%). The median result of residual emissions was 10%, which is equal to the cross-sector pathway provided by the SBTi. All companies except power generation and forest, land and agriculture companies can use the cross-sector pathway with 10% residual emissions (SBTi et al., Citation2021). By providing this predefinition, the SBTi risks incentivising some companies that could reduce further to only reduce by 90%. The way it legitimizes residual emissions based on past emissions (grandfathering), which has been questioned as they are not based on science (Tilsted et al., Citation2023).

Regarding further research, an additional exploration of the coverage of different scopes of the emissions would be necessary. Absolute scope 3 targets to reduce emissions are not a strict requirement in any standard for all sectors. The SBTi holds that coverage of scope 3 emissions should be mandatory if a significant share of emissions is scope 3, but they can also be covered by intensity targets for some sectors. The ISO net zero guidelines only require companies to provide a reason for excluding scope 3 emissions (International Organization for Standardization [ISO], Citation2022). Fankhauser et al. (Citation2022) do not mention scope coverage in their article outlining the definition of net zero, while the Oxford Offsetting Principles demand a thorough documentation of scope coverage of the pledges (Allen et al., Citation2020). The problem of completeness in relation to the definition of climate neutrality has already been raised previously (dena, Citation2022). Only 29 companies had an absolute scope 3 target, even though scope 3 emissions represent a significant share of the emissions for many of the assessed companies. A broader coverage of scope 3 emissions would improve net zero targets (Rogelj et al., Citation2021).

Websites or initiatives that evaluate corporate net zero pledges should include an analysis of the companies’ residual emissions levels and their justification for them as additional criteria in their questionnaires. The additional criteria could be the ones proposed in this paper. Assessing these criteria and publishing the results in databases (Day et al., Citation2023b; Lang et al., Citation2023; Manier, Citation2023) or reports free of charge is the first precondition to enabling a public discourse about residual emissions, as called for by scientists (Buck et al., Citation2023; Wissenschaftsplattform Klimaschutz, Citation2022).

Now, I turn to the inherent limitations of voluntary corporate climate pledges. As has previously been outlined, in identifying the level of residual emissions, companies do not consider whether the production of a good is necessary for human wellbeing (Lund et al., Citation2023). In the language of the mitigation hierarchy, this could be interpreted as a missing consideration in the ‘Avoid’ step. Jaccard et al. (Citation2021) have shown that Europe’s chances of reaching its climate goals with an unequal distribution of wealth is close to impossible because the energy needed to provide for a decent life and its according carbon footprint leaves next to no room for energy expenditure on luxury consumption. The difficulty of identifying whether products are necessities and increase overall wellbeing while remaining within planetary boundaries has recently been discussed in relation to life cycle assessments of products (Ellsworth-Krebs et al., Citation2023), but it applies to companies’ climate strategies as well. It is clear that companies will not evaluate whether their products are necessary if it means bringing themselves out of business. But since their emissions affect society as a whole, a political debate should arise around what counts as necessary goods. The IPCC has explored demand-side response and social aspects of mitigation and concludes that the reduction of consumption and public participation in climate policy both increase the likelihood of reaching climate targets and promote greater human wellbeing (Creutzig et al., Citation2022).

This leads to the conclusion that stakeholder participation in the definition of residual emission levels should be as broad as possible so as to identify which of the emissions that are currently declared ‘unavoidable’ are not, in fact, related to basic human-needs satisfaction and are therefore eligible for demand-side response. When we speak of unavoidability, we must ask ourselves, unavoidable for whom and under what conditions? This question calls for an inclusive dialogue between stakeholder groups.

Currently, the SBTi, a privately funded NGO, sets residual emission levels, yet lacks clear guidance on which emissions can remain. The allocation of residual emissions to countries and sectors has similarities with ‘fair contributions’ (Dooley et al., Citation2021) in climate negotiations. To identify what ‘fair contributions’ are for corporations, public participation is necessary instead of leaving the decision to the SBTi. A core theme in the discussions should be how corporate emissions contribute to the fulfilment of the needs of the most vulnerable and how they negatively affect the ability of people to fulfil their needs. As a first step at national level, citizen assemblies, like those in France (Giraudet et al., Citation2022), could discuss the necessity of goods and services including what emission reductions they expect from corporate actors. Allocating residual emissions to international corporations is a matter that needs political debate at international levels, in which civil society involvement is more challenging due to the political and ethical complexity of these negotiations (Kortetmäki, Citation2016). A first step would be to bring residual emission of companies (especially multinationals) to the table at UNFCCC negotiations as suggested by Buck et al. (Citation2023) for countries’ residual emissions.

Another option forward is legislative adjustments. Carbon neutrality claims of products are banned from 2026 in the EU (European Parliament, Citation2023). CSR regulators could start a process to coherently define what criteria have to be met to be eligible for a net-zero or carbon neutrality pledge.

5. Conclusion

This article has shown that most companies with a net zero pledge do not follow the definition of net–zero as emission reduction to a residual level coupled with compensation with removals. The reported residual emission levels across companies vary widely between 0 and 80% (mean = 19.3%, median = 10%). Furthermore, most companies justify their residual emissions with reference to a vague infeasibility, without tying them to a specific process or product. Only twelve out of the 115 analyzed companies fulfil the conditions of an emission reduction goal to a residual level, balance with removals and inclusion of absolute scope 3 emissions in their climate pledge. Only two of these companies name specific processes as a source of their residual emissions. The analysis of the pledges point to a considerable gap in mitigation ambition levels in the corporate sector. The lack of a standard definition of residual emissions has led to an incoherent use of the term in corporate climate pledges. What especially needs more attention is how the mitigation hierarchy is to be included in the net zero goals and how a remaining unavoidable-emission stream is to be defined. Ideally, such a process would be organized by an inter-sectoral political dialogue because the remaining carbon budget and current removal capacities are limited. This means that higher residual emission levels in one sector would need to be evened out by lower levels in other sectors. Future work in this area should explore how to allocate residual emissions across different sectors and companies in an inclusive political dialogue.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (41.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (64.2 KB)Acknowledgements

I want to thank Markus Berger, Kirstine Lund Christiansen and Peter-Paul Pichler for comments on a previous version of this manuscript, as well as interesting discussions and exchange during the research process. I am grateful to Charles Cleminson and Felice Diekel for refining language and argument of a later version of this article. Moreover, I am grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 There could be a benefit of introducing a new category of captured emissions for CCS-based technologies because unlike other emission reductions and removals, the CCS-based technologies depend on long term storage of CO2 in the soil and there is currently limited experience with unintentional releases of captured CO2 to the atmosphere in the long run.

References

- Alibaba. (2021). Carbon Neutrality Action Report. https://sustainability.alibabanews.com/download/Alibaba%20Group%20Carbon%20Neutrality%20Action%20Report_20211217_ENG_Final.pdf

- Allen, M., Axelsson, K., Caldecott, B., Hale, T., Hepburn, C., Hickey, C., Mitchell-Larson, E., Malhi, Y., Otto, F., Seddon, N., & Smith, S. (2020). The Oxford principles for net zero aligned carbon offsetting. University of Oxford, September.

- Amazon. (2022). Sustainability report. https://sustainability.aboutamazon.com/2022-sustainability-report.pdf

- Arendt, R., Bach, V., & Finkbeiner, M. (2021). Carbon offsets: An LCA perspective. In S. Albrecht, M. Fischer, P. Leistner, & L. Schebek (Eds.), Progress in life cycle assessment 2019. Sustainable production, life cycle engineering and management (pp. 189–212). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50519-6_14

- Arnold, J., & Toledano, P. (2021). Corporate Net-Zero Pledges: The Bad and the Ugly. Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment.

- Asiyanbi, A. P. (2016). A political ecology of REDD+: Property rights, militarised protectionism, and carbonised exclusion in Cross River. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 77, 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.10.016

- Asiyanbi, A. P. (2022). Forest carbon offsetting or development as usual?: Three spaces of a zombie solution. In J. Connuck (Ed.), Cooking sections: Offsetted (pp. 1–175). Hatje Cantz.

- AT&T. (2023). Climate strategy & transition plan 2023 update. https://about.att.com/ecms/dam/csr/2023/Environment/ClimateStrategyTransitionPlan.pdf

- BHP. (2022). Appendix 4E. https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/media/reports-and-presentations/2022/220816_appendix4e.pdf

- Bjørn, A., Lloyd, S., Schenker, U., Margni, M., Levasseur, A., Agez, M., & Matthews, H. D. (2023). Differentiation of greenhouse gases in corporate science-based targets improves alignment with Paris temperature goal. Environmental Research Letters, 18(8), 084007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ace0cf

- Böhm, S., & Dabhi, S. (Eds.). (2009). Upsetting the offset of carbon: The political economy of carbon markets. In Gene (pp. 1–384). mayfly.

- Buck, H. J., Carton, W., Lund, J. F., & Markusson, N. (2023). Why residual emissions matter right now. Nature Climate Change, 13(4), 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01592-2

- IPCC, Calvin, K., Dasgupta, D., Krinner, G., Mukherji, A., Thorne, P. W., Trisos, C., Romero, J., Aldunce, P., Barrett, K., Blanco, G., Cheung, W. W. L., Connors, S., Denton, F., Diongue-Niang, A., Dodman, D., Garschagen, M., Geden, O., Hayward, B., … Ha, M. (2023). IPCC, 2023: Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [Core writing team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC. https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

- SBTi, Carrillo Pineda, A., Chang, A., & Faria, P. (2020). Foundations for science-based net-zero target setting in the corporate sector.

- Carton, W., Lund, J. F., & Dooley, K. (2021). Undoing equivalence: Rethinking carbon accounting for just carbon removal. Frontiers in Climate, 3, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.664130

- SBTi, Chang, A., Anderson, C., & Aden, N. (2021). Pathways to net-zero SBTi technical summary. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/Pathway-to-Net-Zero.pdf

- Comcast. (2022). Impact report. https://corporate.comcast.com/impact/report/2023

- Creutzig, F., Roy, J., Devine-Wright, P., Díaz-José, J., Geels, F. W., Grubler, A., Maïzi, N., Masanet, E., Mulugetta, Y., Onyige, C. D., Perkins, P. E., Sanches-Pereira, A., & Weber, E. U. (2022). Demand, services and social aspects of mitigation. In IPCC (Ed.), Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working group III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 1–16). Cambridge University Press.

- Day, T., Mooldijk, S., Hans, F., Smit, S., Posada, E., Skribbe, R., Woollands, S., Fearnehough, H., Kuramochi, T., Warnecke, C., Kachi, A., & Höhne, N. (2023a). Corporate climate responsibility: Guidance and assessment criteria for good practice corporate emission reduction and net-zero targets. https://newclimate.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/NewClimate_MD_CorporateTargetSettingNL_Methodology.pdf

- Day, T., Mooldijk, S., Hans, F., Smit, S., Posada, E., Skribbe, R., Woollands, S., Fearnehough, H., Kuramochi, T., Warnecke, C., Kachi, A., & Höhne, N. (2023b). Corporate climate responsibility monitor 2023. https://newclimate.org/resources/publications/corporate-climate-responsibility-monitor-2023

- dena. (2022). Klimaneutralität von Unternehmen Bestehende Standards, Initiativen und Label sowie Einordnung der Rolle von Treibhausgas-Kompensation. https://www.dena.de/fileadmin/dena/Publikationen/PDFs/2022/ANALYSE_Klimaneutralitaet_von_Unternehmen.pdf

- Disfold. (2023, August 16). Disfold. https://disfold.com/

- Dominion Energy. (2022). Dominion energy climate report. https://esg.dominionenergy.com/assets/pdf/2022-Climate-Report.pdf

- Dooley, K., Holz, C., Kartha, S., Klinsky, S., Roberts, J. T., Shue, H., Winkler, H., Athanasiou, T., Caney, S., Cripps, E., Dubash, N. K., Hall, G., Harris, P. G., Lahn, B., Moellendorf, D., Müller, B., Sagar, A., & Singer, P. (2021). Ethical choices behind quantifications of fair contributions under the Paris Agreement. Nature Climate Change, 11(4), 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01015-8

- Dooley, K., Keith, H., Catacora-Vargas, G., Carton, W., Christiansen, K. L., Enokenwa Baa, O., Frechette, A., Hugh, S., Ivetic, N., Lim, L. C., Lund, J. F., Luqman, M., Mackey, B., Monterroso, I., Ojha, H., Perfecto, I., Riamit, K., Robiou du Pont, Y., & Young, V. (2022). The land gap report. https://www.landgap.org/

- Edelenbosch, O. Y. (2022). Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions in hard-to-abate sectors. https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/pbl-2022-mitigating-greenhouse-gas-emissions-in-hard-to-abate-sectors-4901.pdf

- Eli Lilly. (n.d.). Climate. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.esg.lilly.com/environmental/climate

- Ellsworth-Krebs, K., Niero, M., & Jack, T. (2023). Feminist LCAs: Finding leverage points for wellbeing within planetary boundaries. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 39, 546–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.05.035

- Enel. (2023). Zero emission ambition. https://www.enel.com/content/dam/enel-com/documenti/investitori/sostenibilita/zero-emissions-ambition-report.pdf

- Engie. (2023). Integrated Report. https://www.engie.com/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2023-05/ENGIE_RI_2023_EN-1605.pdf

- Equinor. (2022). Energy transition plan. https://cdn.equinor.com/files/h61q9gi9/global/6a64fb766c58f70ef37807deca2ee036a3f4096b.pdf?energy-transition-plan-2022-equinor.pdf

- et-Redaktion. (2022). Unvermeidbare Restemissionen: Deutschland braucht eine CO2-Strategie. https://www.energie.de/et/news-detailansicht/nsctrl/detail/News/unvermeidbare-restemissionen-deutschland-braucht-eine-co2-strategie

- European Parliament. (2023, September 19). EU to ban greenwashing and improve consumer information on product durability. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20230918IPR05412/eu-to-ban-greenwashing-and-improve-consumer-information-on-product-durability

- Fankhauser, S., Smith, S. M., Allen, M., Axelsson, K., Hale, T., Hepburn, C., Kendall, J. M., Khosla, R., Lezaun, J., Mitchell-Larson, E., Obersteiner, M., Rajamani, L., Rickaby, R., Seddon, N., & Wetzer, T. (2022). The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nature Climate Change, 12(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01245-w

- Giraudet, L. G., Apouey, B., Arab, H., Baeckelandt, S., Bégout, P., Berghmans, N., Blanc, N., Boulin, J. Y., Buge, E., Courant, D., Dahan, A., Fabre, A., Fourniau, J. M., Gaborit, M., Granchamp, L., Guillemot, H., Jeanpierre, L., Landemore, H., Laslier, J. F., … Tournus, S. (2022). “Co-construction” in deliberative democracy: Lessons from the French citizens’ convention for climate. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01212-6

- Glencore. (2022). Climate report. https://www.glencore.com/.rest/api/v1/documents/529e3b5028692472bc9f97e143d73557/GLEN-2022-Climate-Report.pdf

- Grupo México. (2022). Sustainable development report. https://www.gmexico.com/GMDocs/InformeSustentable/Eng/SDR_2022.pdf

- Helppi, O., Salo, E., Vatanen, S., Pajula, T., & Grönman, K. (2023). Review of carbon emissions offsetting guidelines using instructional criteria. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 28(7), 924–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-023-02166-w

- Holcim. (2023). Climate report. https://www.holcim.com/sites/holcim/files/2023-03/31032023-holcim-climate-report-2023-7392605829.pdf

- HSBC Holdings. (n.d.). ESG review. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.hsbc.com/who-we-are/esg-and-responsible-business/esg-reporting-centre

- International Organisation for Standardization. (2023). ISO/FDIS 14068:2023 (Greenhouse gas management and climate change management and related activities — Carbon neutrality.

- International Organization for Standardization [ISO]. (2022). International workshop agreement (IWA 42): Net zero guidelines.

- IPCC. (2022). Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Summary for policymakers (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926.001

- Jaccard, I. S., Pichler, P. P., Többen, J., & Weisz, H. (2021). The energy and carbon inequality corridor for a 1.5 C compatible and just Europe. Environmental Research Letters, 16(6), 064082. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abfb2f

- JPMorgan Chase. (2022). Environmental social governance report. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/documents/jpmc-esg-report-2022.pdf

- Kaupa, C. (2022). Peddling false solutions to worried consumers: The promotion of greenhouse Gas ‘offsetting’ as a misleading commercial practice. Journal of European Consumer and Market Law. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4157810

- Kortetmäki, T. (2016). Reframing climate justice: A three-dimensional view on just climate negotiations. Ethics, Policy & Environment, 19(3), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2016.1226238

- Lamb, W. (2024). The size and composition of residual emissions in integrated assessment scenarios at net-zero CO2. Environmental Research Letters, 19(4), 044029. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad31db

- Lamb, W. F., Gasser, T., Roman-Cuesta, R. M., Grassi, G., Gidden, M. J., Powis, C. M., Geden, O., Nemet, G., Pratama, Y., Riahi, K., Smith, S. M., Steinhauser, J., Vaughan, N. E., Harry B. Smith, H. B., & Minx, J. C. (2024). The carbon dioxide removal gap. Nature Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-01984-6

- Lang, J., Hyslop, C., Lutz, N., Short, N., Black, R., Chalkley, P., Hale, T., Hans, F., Hay, N., Höhne, N., Hsu, A., Kuramochi, T., Mooldijk, S., & Smith, S. (2023). Net Zero Tracker. In Energy and climate intelligence unit, data-driven EnviroLab, NewClimate Institute, Oxford Net Zero.

- Luderer, G., Vrontisi, Z., Bertram, C., Edelenbosch, O. Y., Pietzcker, R. C., Rogelj, J., De Boer, H. S., Drouet, L., Emmerling, J., Fricko, O., Fujimori, S., Havlík, P., Iyer, G., Keramidas, K., Kitous, A., Pehl, M., Krey, V., Riahi, K., Saveyn, B., … Kriegler, E. (2018). Residual fossil CO2 emissions in 1.5-2 °C pathways. Nature Climate Change, 8(7), 626–633. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0198-6

- Lund, J. F., Markusson, N., Carton, W., & Buck, H. J. (2023). Net zero and the unexplored politics of residual emissions. Energy Research & Social Science, 98, 103035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103035

- Manier, V. (2023, August 16). Net 0 tracker. https://net0tracker.org/

- Meta Platforms. (2023). Our path to net zero. https://sustainability.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Meta-2023-Path-to-Net-Zero.pdf

- MSCI. (2023). The Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®). MSCI Inc. https://www.msci.com/oursolutions/indexes/gics

- National Grid. (2022). Climate transition plan. https://www.nationalgrid.com/document/146726/download

- Net Zero Tracker. (2023). Net Zero Stocktake 2023. https://zerotracker.net/analysis/net-zero-stocktake-2023

- NextEra Energy. (2022). Zero carbon blueprint. https://www.nexteraenergy.com/content/dam/nee/us/en/pdf/NextEraEnergyZeroCarbonBlueprint.pdf

- Philip Morris International. (2021). Low-carbon transition plan. https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/pmi-sustainability/pmi_lctp_211026.pdf?sfvrsn = 5c4c19b7_12

- Probst, B., Toetzke, M., Diaz Anadon, L., Kontoleon, A., & Hoffmann, V. (2023). Preprint: Systematic review of the actual emissions reductions of carbon offset projects across all major sectors. Research Square, 1–31.

- Procter & Gamble. (2021). Climate transition action plan. https://s1.q4cdn.com/695946674/files/doc_downloads/esg/PG_CTAP.pdf

- Rio Tinto. (2022). Climate change report. https://www.riotinto.com/en/invest/reports/climate-change-report#

- Rogelj, J., Geden, O., Cowie, A., & Reisinger, A. (2021). Net-zero emissions targets are vague: Three ways to fix. Nature, 591(7850), 365–368. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00662-3

- SBTi. (2021). Beyond value chain mitigation. In SBTi corporate Net-zero standard criteria (pp. 1–10). https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/Beyond-Value-Chain-Mitigation-FAQ.pdf

- SBTi. (2022). Cement Science Based Target Setting Guidance. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTi-Cement-Guidance.pdf

- Schenuit, F., Boettcher, M., & Geden, O. (2023). “Carbon Management”: Opportunities and risks for ambitious climate policy (9; Comment).

- Smith, S. M. (2021). A case for transparent net-zero carbon targets. Communications Earth & Environment, 2(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00095-w

- Smith, S. M., Geden, O., Nemet, G., Gidden, M., Lamb, W. F., Powis, C., Bellamy, R., Callaghan, M., Cowie, A., Cox, E., Fuss, S., Gasser, T., Grassi, G., Greene, J., Lück, S., Mohan, A., Müller-Hansen, F., Peters, G., Pratama, Y., … Minx, J. C. (2023). The state of carbon dioxide removal (1st ed.). (squarespace.com).

- Southern Company. (2020). Implementation and action towards net zero. https://www.southerncompany.com/content/dam/southerncompany/pdfs/about/governance/reports/Net-zero-report_PDF1.pdf

- SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, & FDP. (2021). Mehr Fortschritt wagen: Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit.

- Stevenson, M. (2020). Mitigation hierarchies first things first: Avoid, reduce … and only after that – Compensate. In WWF Discussion Paper (pp. 1–2). https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?362819/First-Things-First-Avoid-Reduce–and-only-after-thatCompensate

- Tilsted, J. P., Palm, E., Bjørn, A., & Lund, J. F. (2023). Corporate climate futures in the making: Why we need research on the politics of science-based targets. Energy Research & Social Science, 103, 103229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103229

- TotalEnergies. (2023). Sustainability & climate progress report. https://totalenergies.com/system/files/documents/2023-03/Sustainability_Climate_2023_Progress_Report_EN.pdf

- Trencher, G., Blondeel, M., & Asuka, J. (2023). Do all roads lead to Paris? Climatic Change, 176(7), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03564-7

- Ultratech Cement. (2022). Integrated and sustainability report. https://www.ultratechcement.com/content/dam/ultratechcementwebsite/pdf/sustainability-reports/integrated-and-sustainability-report-2023-single-page.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2015). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. U.N. Doc. FCCC.

- Unilever. (2021). Climate transition action plan. https://www.unilever.com/planet-and-society/climate-action/strategy-and-goals/

- Unitedhealth. (2022). Sustainability report. https://sustainability.uhg.com/content/dam/sustainability-report/2022/pdf/2022-sustainability-report.pdf

- Vale. (2021). Climate change report. https://vale.com/documents/d/guest/vale_cc_2021-en?_gl = 1*d61p7j*_ga*NTM0NjM1NzA4LjE2OTE0ODMyMTI.*_ga_BNK5C1QYMC*MTY5MTQ4MzIxMS4xLjAuMTY5MTQ4MzIxMS42MC4wLjA

- van Diemen, R., Matthews, J. B. R., Möller, V., Fuglestvedt, J. S., Masson-Delmotte, V., Méndez, C., Reisinger, A., & Semeno, S. (2022). Annex I: Glossary. In IPCC (Ed.), Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working group III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 1–30). Cambridge University Press.

- Verizon. (2022). Environmental social governance report. https://www.verizon.com/about/sites/default/files/Verizon-2022-ESG-Report.pdf

- Walt Disney. (2022). Environmental goals. https://impact.disney.com/app/uploads/2023/06/2030-Environmental-Goals-White-Paper.pdf

- Watt, R. (2021). The fantasy of carbon offsetting. Environmental Politics, 30(7), 1069–1088. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1877063

- West, T. A. P., Wunder, S., Sills, E. O., Börner, J., Rifai, S. W., Neidermeier, A. N., Frey, G. P., & Kontoleon, A. (2023). Action needed to make carbon offsets from forest conservation work for climate change mitigation. Science, 381(6660), 873–877. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ade3535

- Wissenschaftsplattform Klimaschutz. (2022). Negative Emissionen und CCS für die Klimaneutralität: Stand der Forschung und der Weg zu einer Carbon Management Strategie (Impulspapier Der Wissenschaftsplattform Klimaschutz).