ABSTRACT

Climate action threatens to exacerbate existing social inequities, so it is important for justice to be at the heart of national responses to climate change. Based on an understanding of climate change as a manifestation of severed relationships and exploitative dynamics that are produced and reproduced through colonial, capitalist, patriarchal systems, we argue that the ways in which we conceptualize and enact climate justice must be decolonial, ecocentric, relational and integrative. Consistent with this positioning, we sought to develop an Indigenous climate justice policy analysis tool to assess and inform policy development. We drew on elements of existing frameworks and tools to develop a tool, which was progressively refined following external advisory group review and piloting. The tool addresses five dimensions of justice (relational, procedural, distributive, recognition and restorative), each of which comprises individual criteria assessed according to three levels of achievement. This rating system acknowledges progress within existing social, political and economic systems, but also identifies system transformation as a prerequisite for achieving genuine justice. Application of the tool focuses attention on issues well beyond typical climate policy considerations, such as the capacity of all human and non-human entities to express political agency. The tool has been developed for use in analysing national climate policy in Aotearoa New Zealand, but we have endeavoured to make it adaptable for use in other settings.

Key policy insights

Climate injustice is rooted in colonialism; Indigenous decolonial conceptions of climate justice provide a critical grounding for policy responses to climate change.

Climate justice is not attainable within existing colonial political systems. It can only be achieved through reform of governance and constitutional arrangements to re-establish Indigenous natural law.

Analysis of climate policy must consider not only how to optimize justice within existing social, political and economic systems, but also how policy can disrupt those systems to create transformative change.

Our policy analysis tool, grounded in relational epistemologies, extends beyond the scope of conventional analyses to examine critical issues across five dimensions of justice.

Introduction

Responding to the threat of climate change requires urgent and substantial reduction of greenhouse gas emissions globally (IPCC, Citation2018), with wealthy, industrialized countries bearing greatest responsibility (Hickel, Citation2020). This will necessitate wide-ranging, fundamental societal change, including in energy, urban design and transport, land use, agriculture and food systems. In order to achieve this unprecedented transition, governments will need to put in place a broad range of policies including financial mechanisms, regulatory measures and provision of public services (IPCC, Citation2015). The adverse impacts of such far-reaching policies are likely to be disproportionately borne by disadvantaged and marginalized communities (Markkanen & Anger-Kraavi, Citation2019; Sovacool, Citation2021), including Indigenous peoples (Jones, Citation2019). For example, there is evidence of significant adverse impacts on Indigenous communities as a result of climate change mitigation measures (Tauli-Corpuz & Aqqaluk, Citation2008). Indeed, the structural inequity built into settler-colonial political systems, occurring against a backdrop of intergenerational oppression and dispossession, ensures that Indigenous peoples are regularly and systematically disadvantaged in all aspects of climate change mitigation and adaptation (Whyte, Citation2019).

The existing body of knowledge is limited in its ability to guide climate policy, with the balance of co-benefits and co-harms for Indigenous health strongly dependent on specific policy features and contextual factors (Jones et al., Citation2020). A justice-oriented analysis of policy responses to climate change is therefore critical to avoid exacerbating existing harms and to support pro-equity action. In this article, we consider justice in national responses to climate change, with a specific focus on Indigenous conceptions of climate justice. Dominant environmental justice frameworks fail to recognize the unique experiences of Indigenous communities including the central role of colonialism (Parsons et al., Citation2021; Whyte, Citation2018), prompting calls to indigenize environmental justice (Gilio-Whitaker, Citation2020; McGregor, Citation2018). A distinct Indigenous formulation is required to address the particular manifestations of ecological crisis and associated forms of injustice experienced by Indigenous peoples (McGregor et al., Citation2020).

We sought to develop a tool for assessing climate policy against Indigenous climate justice criteria. In a preliminary review of the literature, we were unable to identify a tool that met our needs for a comprehensive policy analysis in the Aotearoa New Zealand context; we therefore sought to develop a tool based on our conceptualization of Indigenous climate justice. The tool is intended for use by policymakers, researchers and advocates, with a view to being used either prospectively (with respect to proposed policies) or retrospectively (for existing or historical policies). The intended scope of the analytical tool includes not just the policy under consideration, but also importantly the process of policy development and the underpinning governance and organizational structures and relationships. While the tool has been developed primarily for analyzing national climate policy in Aotearoa New Zealand, we have designed it to be adaptable for use in other settler colonial contexts.

In this article we first articulate our research positioning, outlining the worldviews, values and assumptions on which the research is based. We then review existing understandings of environmental, climate and planetary justice to articulate a conceptualization of Indigenous climate justice. The methods for developing and piloting the climate justice policy analysis tool are described. We then outline the structure and core components of the tool, with an explanation of the five domains (dimensions of justice) and how each is operationalized within the tool. The tool itself is presented, accompanied by examples of evidence sources for each of the criteria. In the discussion, we examine the strengths and weaknesses of the tool and suggest possible applications.

Unless otherwise stated, the term ‘Indigenous’ is used in this article in a universal way, referring to issues or qualities that are broadly shared by Indigenous Peoples everywhere. While every Indigenous group has its own unique historical, geographical, social, cultural and political context, there are aspects of Indigenous cultures and lived experiences that are common to all Indigenous Peoples (particularly in settler colonial nations). When a statement relates to a particular Indigenous population, for example Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand, this is specified.

Research positioning

We approach this work as public health academics from Aotearoa New Zealand, with backgrounds in research and advocacy on climate change, Indigenous rights, health and equity. RJ and PR are Māori (Indigenous Peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand) and AM is Pākehā (Aotearoa New Zealand settler of Celtic descent). This research was underpinned by Kaupapa Māori methodology, which centralizes Māori conceptions of wellbeing, priorities and aspirations, social and cultural contexts, and Indigenous rights (Curtis, Citation2016; Moewaka Barnes, Citation2000; Walker et al., Citation2006). It also critiques dominant Western theoretical and policy approaches and offers decolonizing approaches to this area of research (Mahuika, Citation2008; Pihama, Citation2010; Smith, Citation2012). In particular, the research has been informed by a set of values and principles drawn from our conception of a decolonial, relational vision of planetary health (Jones et al., Citation2022). They include recognition of the centrality of whakapapa (or kin-based) relationships to all our human and more-than-human relatives, which is a central feature of Indigenous worldviews and cosmological traditions. In Māori creation stories, for example, all beings in the natural world emerged from within the realms of Ranginui, the Sky, and Papatūānuku, the Earth – our common ancestors. An important implication of these cosmogonic explanations is that each of us is connected by whakapapa to all other humans and everything else within the natural world (Mikaere, Citation2011). Positioning ourselves as sharing a common ancestry with all of nature is associated with an implicit appreciation of the connectedness and interdependence of all things and a recognition of our mutual responsibilities. It follows that human flourishing, and indeed survival, depends upon the restoration and maintenance of relationships with all other beings.

Indigenous climate justice

Climate justice is a contested concept, with divergent understandings of its meaning, scope and implications (Newell et al., Citation2021). It has emerged from the environmental justice movement and has been influenced by its ideas, demands and principles (Schlosberg & Collins, Citation2014). The origins of the modern environmental justice movement are often traced back to the late 1960s when US civil rights leaders integrated notions of environmental racism into their agenda (McGurty, Citation1997). However, Aboriginal peoples have long-held and well-developed conceptions of justice that are applicable in this area (McGregor, Citation2009). These Indigenous systems of justice are grounded in relationships and responsibilities; the set of guiding principles for maintaining balanced relationships with all our relatives is often referred to as ‘natural law’ (McGregor, Citation2018; Redvers et al., Citation2020). McGregor (Citation2009) explains that, according to Anishnaabe tradition, the spirit world and ‘all beings of creation’ have relationships and responsibilities and all these beings, including ancestors and generations to come, are entitled to environmental justice.

Taxonomies of environmental justice commonly refer to its conceptual dimensions. The seminal framework developed by Schlosberg (Citation2007) comprises recognitional, procedural and distributive dimensions. Other formulations include the concept of corrective justice (Whyte, Citation2011), which is also understood as restorative justice (Abram et al., Citation2022; McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018). Whyte (Citation2021a) highlights the central tradition of kinship, which refers to the qualities of relationships, and notes that environmental injustice can be understood as an assault on kin-based relationships. Practising kinship ethics, for example through activities that realize and strengthen reciprocal bonds with the environment and our other relatives, is therefore an unequivocal expression of environmental justice. This relational dimension is often not explicitly articulated in environmental justice frameworks.

Given the centrality of kinship relationships, it follows that Indigenous conceptions of environmental justice are inherently anti-colonial – because settler colonialism is a form of violence that disrupts relationships between humans and our more-than-human relations (Whyte, Citation2018). This anti-colonial orientation encompasses multiple systems of oppression and the intersections between them, for example acknowledging the deep connections between settler colonialism, heteropatriarchy and gender-based violence (Arvin et al., Citation2013; Weaver, Citation2009). Climate change can be understood as a manifestation of colonialism, so climate justice requires critical engagement with processes on a time scale that extends well beyond the conventional ‘Anthropocene’ era (Davis & Todd, Citation2017; Whyte, Citation2017). Justice requires system transformation, not simply optimizing the status quo, aligning with decolonial and emancipatory theoretical traditions that emphasize dismantling systems of oppression rather than just trying to make them less harmful (Smith, Citation2012; Tuck & Yang, Citation2012).

A further implication is that Indigenous sovereignty is a necessary foundation for environmental justice. Upholding the mutual responsibilities that underpin relational justice requires certain rights and freedoms. In countries like Aotearoa New Zealand, settler colonial systems currently limit those rights and freedoms and prevent Indigenous peoples from fulfilling the associated responsibilities; kinship ethics cannot be fully enacted in a context where relationships with our more-than-human relatives are subject to external constraints (Hutchings et al., Citation2020). Achieving environmental justice therefore requires that Indigenous natural law has primacy, at least to the extent that essential kin-based relationships remain under Indigenous peoples’ control.

We conceptualize the scope of Indigenous climate justice in broad terms, encompassing ethical, equity and rights issues in relation to climate change, including its causes and effects as well as the full range of actions taken in response. The time scale spans the past, present and future, consistent with an understanding of climate change as a manifestation of underlying processes that extend across centuries or even millennia. It is not just humans who have agency, entitlements and responsibilities within this framework, but also all our other relations, as well as the ancestors of all current beings and those still to come. Its overarching goal is the restoration and maintenance of harmonious relationships between all these beings, and it has an explicitly anti-colonial orientation. The validity and legitimacy of Indigenous worldviews, values and knowledge systems is taken for granted, as is the need for restoration of Indigenous sovereignty. Its conceptual dimensions include relational, procedural, distributive, recognition(al) and restorative justice.

Development of the tool

Our approach involved the development of a provisional tool, piloting of the tool by applying it to a climate policy issue and subsequent refinement. We first reviewed relevant tools, frameworks and other resources with a view to identifying elements that aligned with the above values and principles. This review included a diverse range of conceptual and policy-related frameworks from around the world but with an emphasis on Aotearoa New Zealand, as summarized in . The range of sources reflects a public health and planetary health orientation, while drawing on broader policy, justice and rights-based frameworks.

Table 1. Sources used to inform tool development.

We undertook an informal thematic analysis of these sources, drawing out relevant concepts which formed the basis of a draft tool. We first identified broad concepts that aligned with our conceptualization of Indigenous climate justice, for example recognition of Indigenous self-determination, the capacity for all beings to express political agency and the need for redress of historical injustices. Some concepts appeared frequently, and eventually no new themes were identifiable as we reviewed additional sources. This was an iterative process that involved repeated review of key sources to check that we had not missed any important concepts.

From each of these broad concepts, we developed one or more questions by translating the concept into a more specific enquiry that could be applied in the analysis of climate policy. In doing this we particularly drew on frameworks and tools that included specific questions or details of how justice principles can be operationalized in practice. Two sources were particularly informative in this regard: the framework developed by Williams and Doyon (Citation2019) for incorporating justice in transitions research and Maria Bargh’s (Citation2019) ‘Tika transition toolbox’, which identifies key considerations and specific questions to ask with respect to policy for a just transition.

This set of questions, organized under the five justice dimensions outlined above, constituted the draft tool. This was reviewed by an advisory group, comprising four members with expertise in Indigenous health, relationships between human and ecosystem health, biophysical and cultural indicators, the integration of Māori knowledge and values into environmental planning and sustainable resource management, climate change, justice, policy evaluation and Māori research methodologies. The review process included two workshops in August 2021 and March 2022, followed by feedback on subsequent drafts of the tool. Informed by this feedback, we iteratively revised the tool. Revisions included modifying some questions, removing or amalgamating others, as well as shifting some questions to a different justice dimension. An important improvement made as a result of this process was the addition of descriptors for each question that specify different levels of achievement. Accordingly, each of these items was reframed as a criterion, comprising a question and corresponding indicators. From this process, we produced a provisional version of the tool.

Piloting the tool

The pilot involved using the tool to analyze the New Zealand Climate Change Commission’s 2021 advice to government. Analysis of the policy advice was undertaken by two authors (RJ and AM) using publicly available information sources, including the final report (He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission, Citation2021) and associated documents. It is outside the scope of this article to report on the findings of this analysis. The purpose of the pilot was to determine the feasibility of using the tool in climate policy analysis and to identify any problems, gaps, areas of redundancy or duplication, and potential improvements. Throughout the process of analysis we reviewed the performance of each criterion, and on completion reviewed the tool as a whole, using the questions in . As a result of this process, the tool was refined and finalized.

Table 2. Questions used to pilot the tool.

The tool

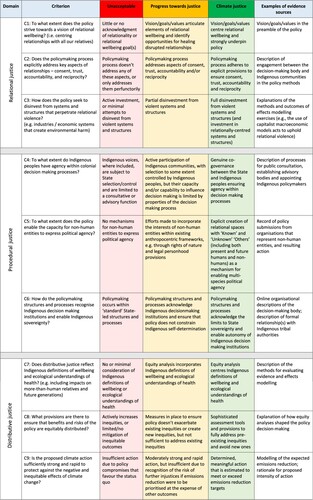

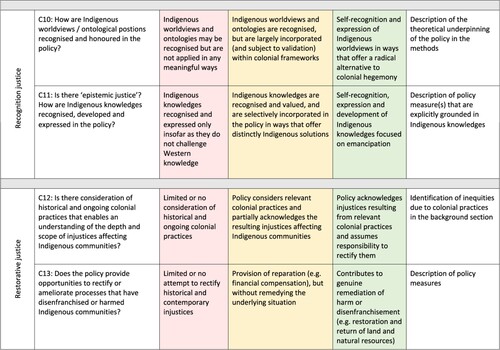

The tool comprises 13 criteria organised under five domains (). These domains represent the key justice dimensions identified above: relational justice, procedural justice, distributive justice, recognition justice and restorative justice. For each criterion, descriptors are provided for three levels of achievement (“Unacceptable”, “Progress towards justice”, “Climate justice”). A further column presents examples of evidence sources, drawing on the policy analysis conducted for the pilot. A description of each of the domains and their expression in the tool is provided in the section ‘Key dimensions of climate justice’.

Figure 1. Indigenous climate justice policy analyis tool.

With respect to assessment of each criterion, we endeavoured to reflect the necessary end goal of system transformation, consistent with our assertion that climate justice is not possible within existing colonial governance arrangements and prevailing capitalist economic systems (Jones et al., Citation2022). Achieving climate justice is therefore dependent on extractive, colonial, capitalist systems having been dismantled and replaced by systems based on relational values and Indigenous natural law. Nonetheless, we recognize the long-term nature of any such systemic change process and the need to incorporate shorter-term measures that demonstrate progress towards climate justice within the constraints of prevailing systems, laws and governance structures. The tool therefore specifies three levels of achievement for each criterion: (1) Unacceptable, reflecting either harmful impacts or no improvement on the status quo; (2) Progress towards justice, reflecting some improvement, but generally within existing frameworks, systems and institutional norms, and; (3) Climate justice, which represents full expression of justice for all human and non-human entities, unconstrained by existing frameworks or systems of governance.

The tool is designed to provide a qualitative assessment of a policy or policymaking process, identifying positive and/or negative aspects with respect to Indigenous climate justice. We do not recommend using it to derive an overall score or to determine whether or not the policy as a whole meets an arbitrary threshold of ‘justness’. Rather, it is intended to be used to elucidate the ways in which the policy does or does not uphold Indigenous climate justice and indicate actions required to make progress towards justice. An important point here is that justice must be achieved across all dimensions; any other outcome is, by definition, unjust.

Key dimensions of climate justice

Relational justice

Relational justice acknowledges the centrality of relationships in determining rights and responsibilities and informing ways of being in the world. It extends the notion of cosmopolitan justice, which maintains that all human beings have equal moral worth and that principles of justice apply universally (McCauley et al., Citation2019), to acknowledge our place in a global community with relationships and associated responsibilities encompassing all other beings. Indigenous conceptions of climate justice emphasize relational considerations, recognizing that the disruption of essential relationships lies at the root of the climate crisis. Whyte (Citation2020) identifies the crossing of ‘relational tipping points’, which reflects societies’ failure to establish or maintain relational qualities between societal institutions, as critical injustices in the context of climate action. Relational justice encompasses the interrelatedness, reciprocity, complementarity and interdependence among the Earth, Sky and everything within these realms.

Important elements of relational justice addressed in the tool include the extent to which policies strive towards a vision of relational wellbeing and how the policy explicitly addresses key aspects of relationships such as consent, trust, accountability, and reciprocity (Whyte, Citation2020). The tool also seeks evidence of disinvesting from systems and structures that perpetrate relational violence. This incorporates efforts to address the commercial determinants of planetary health (Sula-Raxhimi et al., Citation2019), for example divesting from harmful industries, but takes a broader view that acknowledges the inevitability of relational injustices while colonial systems and the global economic model prevail.

Procedural justice

Procedural justice relates to fairness in processes of policy and decision making. It is widely acknowledged as an essential aspect of environmental and climate justice, and a key consideration when planning for a just transition (Abram et al., Citation2022; McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018; Parsons et al., Citation2021; White & Leining, Citation2021). Important aspects of procedural justice include properties of the decision-making process, agency and qualities of interpersonal interactions (Ruano-Chamorro et al., Citation2022). There are particular implications for Indigenous peoples’ participation, as expressed in Article 18 of UNDRIP: ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision-making institutions’ (United Nations, Citation2007, pp. 15–16). A critical aspect is self-determination, requiring provision for a degree of Indigenous autonomy including effective authority over Indigenous resources (Bargh & Tapsell, Citation2021; Jones, Citation2010).

Our conception of procedural justice also requires consideration of how non-human entities are included as active participants in decision-making processes and are imbued with the capacity to express political agency (Ulloa, Citation2017). Non-human entities, also referred to in this article as our ‘more-than-human relatives’, comprise all living things as well as other natural entities such as land, water and air. Mechanisms for including these entities as active participants in existing political processes generally involve representative institutions giving voice to non-human interests (Donoso, Citation2017). For example, in Aotearoa New Zealand, three significant geographical regions have been recognized as legal persons, with their respective kaitiaki (local Indigenous peoples with guardianship obligations) representing their interests. This illustrates how ‘the environment’ can become a co-participant in democracy (Winter, Citation2019). Moving beyond representational mechanisms, Celermajer et al. (Citation2021) imagine new forms of deliberation that recast the role of humans and enable a range of non-human communications to be incorporated in political decision-making. Similarly, Tschakert (Citation2022) identifies the possibility of a post-anthropocentric politics that brings together humans and (Known, Distant and Unknown) Others in relational spaces with a view to achieving an inclusive, multispecies justice.

In the policy analysis tool, we are interested in the extent to which Indigenous peoples have agency within policymaking processes, which relates to the capacity of individuals or groups to influence decision making. This criterion recognizes the differential ability of communities to participate in decision-making processes, arising from a complex array of factors driven by systems of structural oppression and privilege (Parsons et al., Citation2021). A key implication is that it is not sufficient to simply provide ‘equal’ opportunities for Indigenous communities to participate; specific, affirmative mechanisms are required to remove barriers and actively facilitate participation. Redistribution of power from the powerful to structurally oppressed groups in society is critical to enable forms of participation that convey influence in decision making (Arnstein, Citation1969). The tool extends this notion to examine how all entities, human and non-human, are imbued with the capacity to express political agency. It also considers the policymaking structures and processes in terms of how they recognize Indigenous decision-making institutions and give effect to Indigenous sovereignty.

Distributive justice

Distributive justice refers to ‘the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of social cooperation among diverse persons with competing needs and claims’ (Kaufman, Citation2012, p. 842). In relation to climate change mitigation and adaptation, it is concerned with how the costs of (or savings from) action are distributed and how any negative or positive co-impacts are distributed among different social groups. Distributive justice is generally positioned as one of the central dimensions of a just transition and an integral component of environmental and climate justice frameworks (Abram et al., Citation2022; McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018; White & Leining, Citation2021).

This component of the tool first examines the extent to which provisions for distributive justice in the policy reflect Indigenous definitions of wellbeing and ecological understandings of health, including relational, environmental and spiritual elements (Milroy et al., Citation2023; Wilson et al., Citation2021). It also considers the way in which the determinants of health inequities are conceptualized, for example the extent to which equity analyses draw on socio-ecological frameworks that incorporate a critical examination of factors such as colonization and structural racism (Curtis et al., Citation2023; Krieger, Citation2011). A further criterion asks what provisions there are to ensure that benefits and risks of the policy are equitably distributed, concerning not just actions to avoid worsening inequities but also the policy’s capacity to address pre-existing inequities. The tool also enquires as to the adequacy of the proposed climate action, recognizing the imperative to protect against the negative and inequitable effects of climate change. This aspect is complex due to tensions between bold and urgent policy action on the one hand and inclusive decision-making processes on the other (Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2020).

Recognition justice

Recognition (or recognitional) justice is concerned with recognition of the distinct cultures, identities, worldviews, knowledges, needs and lived realities of different groups, and respect for each group’s rights including enacting their own governance arrangements (Bennett et al., Citation2019). It acknowledges the way systems of power assign differential value to groups in society (for example, along gender, class or racial/ethnic lines), and seeks to identify and remove unjust hierarchies that prevent equitable recognition (Abram et al., Citation2022; Hurlbert & Rayner, Citation2018). This dimension of justice is commonly incorporated within environmental and climate justice frameworks, sometimes expressed as more specific forms of recognition such as epistemic or cognitive justice (McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018; McGregor et al., Citation2020; Newell et al., Citation2021; Parsons et al., Citation2021). The concept of cognitive justice acknowledges the plurality of knowledges and ways of knowing, offering a critique of the presumed absolute dominance of Western science, with an emphasis on recognizing other philosophical and epistemological traditions including those that emerge from Indigenous societies (Visvanathan, Citation1997).

Recognition of Indigenous values, knowledges and ways of being is increasingly acknowledged as a critical aspect of planetary health and climate mitigation action (Jones et al., Citation2022; Ratima et al., Citation2019; Redvers, Citation2018). However, the concept of recognition justice is not without critique. Most notably, Coulthard (Citation2014) problematizes the ‘politics of recognition’ in settler-colonial contexts, in which Indigenous peoples’ identities and rights are acknowledged only insofar as they do not challenge existing power structures and the enduring project of colonialism. He argues that this serves to maintain the disposession and subjugation of Indigenous peoples, and instead recommends an approach based on Indigenous self-empowerment through reclaiming and revitalizing pre-colonial relationships and cultural traditions.

In the tool we ask how different worldviews and ontological positions are recognized and honored in the policy, as well as whether there is ‘epistemic justice’, with an emphasis on how Indigenous knowledges are recognized, expressed and developed in the policy. With respect to Indigenous worldviews and knowledges, these criteria distinguish between incorporation within Western frameworks and full, autonomous expression in ways that do not require external recognition or validation. This acknowledges that recognition by the colonial state does not constitute justice; it is only through individual and collective self-recognition and desubjectification that Indigenous peoples can achieve genuine emancipation (Coulthard, Citation2007).

Restorative justice

Restorative justice is concerned with repairing harm that has been done in the past (Abram et al., Citation2022). In the environmental justice field, this has tended to focus on addressing environmental damage as a result of corporate activities. However, we conceptualize this dimension of justice in broader terms, including the remediation of harms perpetrated against people, other living things and the natural world. As noted by McCauley and Heffron (Citation2018), ‘environmental restoration is intimately connected with social processes of remediation’ (p. 5). This conceptualization also reflects the understanding of climate change as a manifestation of centuries-long processes of colonialism, capitalism and industrialization that have disrupted Indigenous relationships (Whyte, Citation2019). Restorative justice must therefore have the capacity to address harms experienced as a result of these processes, not just those that have occurred in direct relation to climate change.

This domain examines the extent to which policies consider historical and ongoing colonial practices, to understand the depth and scope of injustices affecting Indigenous communities. It is also concerned with the extent to which the policy recommends or requires actions to rectify situations associated with harm to Indigenous communities and relationships. In this context, we differentiate between reparation (e.g. financial compensation) and correcting the underlying injustice (e.g. restoration and return of land, natural resources and/or political control).

Discussion

Research examining the impacts of sustainability transitions such as national climate mitigation strategies must engage critically with justice (Williams & Doyon, Citation2019). In this article, we describe the development of a policy analysis tool that centres Indigenous climate justice. The tool is structured around five dimensions of justice, with each comprising specific items that enable the assessment of policy against three levels of achievement. This approach responds to Indigenous critiques of climate justice that, even if a policy is ‘just’ in the context of existing political, social and economic systems, that is insufficient. Genuine justice cannot be achieved in the context of a dominant colonial, capitalist patriarchy whose associated hierarchical structures, oppressive dynamics and exterminatory imperatives are antithetical to Indigenous ways of being and preclude the fulfilment of inalienable relational obligations. The tool’s rating system acknowledges progress and improvement within these constraints, but importantly also upholds a longer-term vision and identifies system transformation as a prerequisite for achieving justice.

Our approach sought to move beyond narrow conceptions of equity, which in public health generally privilege distributive equity, to examine broader notions of climate justice. The conceptualization of Indigenous climate justice underpinning the tool extends previous environmental justice frameworks, adding two important dimensions to the commonly used triad of distributive, recognition(al), and procedural justice. The restorative dimension makes explicit the need to understand and address historical processes that have created and maintained injustices. The addition of relational justice reinforces the centrality of kin-based relationships and associated mutual responsibilities between all things in Indigenous expressions of justice. Such an orientation foregrounds our obligations and then identifies what rights are necessary for us to uphold those obligations, in contrast to many justice-based instruments in which human rights are given primacy.

This mirrors recent work in critical environmental justice, which examines multiple forms of inequity and their intersections, extends the scope to consider complex spatial and temporal dynamics, and includes more-than-human entities (Pellow, Citation2021; Schlosberg, Citation2013). It also aligns with inclusive, multispecies conceptions of justice that challenge anthropocentrism and human exceptionalism (Celermajer et al., Citation2021). However, our conceptualization comes from a distinctly Indigenous worldview and has an emphasis on examining and addressing the specific justice issues affecting Indigenous peoples, lands and relational networks, in particular harms inflicted due to colonization. This demonstrates how ‘mainstream’ environmental justice frameworks, even if pluralistic, may be inadequate without attention to the specific communities, environments and experiences being addressed.

Explicit attention to the capacity of all our relatives to express political agency is one of the distinguishing features of our policy analysis tool. This resonates with Kyle Whyte’s (Citation2021b) concept of ‘epistemologies of coordination’ that is about understanding our place in the greater scheme of things through kin relationships. These relationships represent moral bonds that can manifest as mutual responsibilities. Epistemologies of coordination lie at the heart of Indigenous cosmological and philosophical traditions; for example, Royal (Citation2005) notes that the deliberate and conscious expression of natural environments into human society and culture is one of the defining features of formal Indigenous cultures. To some extent, then, Indigenous customary values and practices intrinsically include all our relatives as active participants in decision-making processes. So, by enabling Indigenous Peoples to fulfil our mutual responsibilities, all entities that are part of those kin-based relationships can be imbued with political agency. In a non-Indigenous space, however, it is imperative that policies create explicit mechanisms for this inclusion within existing political systems.

Our approach to developing the tool did not involve a systematic search or a formal literature review process, and cannot claim to be comprehensive. There was an emphasis on elements that aligned with our conception of Indigenous climate justice, informed by critical, decolonial environmental justice and policy analysis tools and frameworks. The purpose of reviewing these tools was to gain a broad understanding of the philosophical approaches and relevant conceptual domains, so it was not intended to be comprehensive or exhaustive. As a result, the tool privileges certain subjects, principles and mechanisms of justice and may therefore be critiqued as being unduly narrow in its scope. This has been identified as a common issue with planetary justice research, which often fails to acknowledge the many dimensions of inequity and to account for the intersections between them, and tends to minimize the tensions between different justice-related outcomes (Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2020; Heyen, Citation2023).

The multidimensional, far-reaching nature of the tool means that analysis is extended to include issues that would usually be well beyond the scope of policy considerations in settler-colonial political systems. For example, the importance of imbuing all (human and non-human) entities with the capacity to express political agency is currently only addressed in a limited way and in a very narrow set of circumstances (Winter, Citation2021). In a sense, then, the tool is assessing policy against criteria that are impossible to meet within the context in which policy development currently occurs. Indeed, in our pilot analysis examining comprehensive climate policy advice in Aotearoa New Zealand, the highest possible (‘green’) rating was not achieved for any of the criteria. However, the tool includes intermediate goals that we believe are achievable within existing arrangements. For example, anthropocentric ‘workarounds’ may help to advance relational justice, drawing on approaches such as the legal personhood of nature (Winter, Citation2021). However, it is important that any such solutions are conceived as a step towards transformation – in this case, prompting a critique of the dominant paradigm of personhood – rather than reinforcing Western worldviews and hierarchies relating to humans and the environment (Reeves & Peters, Citation2021). Further, by highlighting the barriers to climate justice inherent within status quo political structures, the tool can identify and provide impetus for the required systemic changes.

There are, inevitably, tensions between different aspects of justice within the tool. One example is in the way adequacy of climate action is evaluated. Criterion 9 recognizes that climate change itself will have significant adverse and inequitable effects on Indigenous wellbeing, and that rapid, intense emissions reduction is required to mitigate these impacts. However, achieving this far-reaching societal transformation with the necessary urgency threatens to compromise other dimensions of justice, including relational and procedural justice. Whyte (Citation2020) argues that urgent climate action will inevitably result in further injustice against Indigenous peoples, as the required conditions for a just response (relational qualities such as consent, trust, accountability and reciprocity) are not met. Conversely, taking the time to build the necessary relationships and establish the foundations for relational justice could delay important emissions reduction activities. Application of the tool can help to reconcile these tensions by identifying synergies across different dimensions of justice. For example, the tool may highlight the limitations of conventional climate change mitigation measures due to inadequate attention to relationality. By rebuilding relationships between governments and Indigenous peoples, space can be opened up for the expression of Indigenous values and knowledges that offer genuinely transformative solutions.

Possible applications

Although the tool has been developed primarily for use in a specific geographical, social and political context (national climate policy in Aotearoa New Zealand), we have endeavoured to make it adaptable for use in other settings. The broad domains are relevant in many other contexts, particularly in other settler colonial nations as they represent generalized areas in which injustice currently exists within political ecosystems and policy making processes. Many of these dynamics also operate at the level of international decision-making processes and institutions (Nilsson, Citation2008), so the tool may also be useful for analyzing global climate policies and agreements. The tool can be used by a range of stakeholders; it is intended to support Indigenous people and communities in assessing climate policy as a way of holding governments and policy agencies to account, but it also provides a means for non-Indigenous policymakers to critically review their own practice. We welcome others using and adapting the tool and invite critique and suggested improvements.

Conclusion

It is critical that climate action centres justice, with responses at local, national and global levels designed to recognize the potential for injustice and systematically address the contributing factors. In this article we have developed a policy analysis tool based on Indigenous conceptions of climate justice, which are situated within worldviews and ontologies that recognize kin-based relationships with all our (human and more-than-human) relatives and span the past, present and future. The tool brings together important elements to guide the analysis and development of climate policy. It not only articulates the key dimensions and principles of justice that must be considered in a policy analysis, it also operationalizes these elements. That is, it translates the relevant concepts into a set of specific questions that enables the application of those concepts in an analysis of proposed or existing climate policy. In the short to medium term, it can be used to assess and guide policy development within existing constitutional and governance arrangements, but it also goes beyond that to articulate a longer-term vision for climate justice unconstrained by incumbent political and economic systems.

Applying the tool to contemporary policy proposals exposes the limitations of existing political arrangements and colonial governance systems, grounded as they are in anthropocentric, patriarchal, exploitative and extractive values and practices. The implications are clear and point to the need for fundamental, decolonial constitutional change. Nonetheless, the application of the tool also provides guidance on interim steps that can be taken to disrupt business-as-usual processes and initiate virtuous cycles that can potentially drive systemic change. For example, the tool differentiates between compensatory justice, such as providing financial recompense for historical injustices perpetrated against Indigenous peoples, and true restorative justice. Interrogating climate policy through this lens can reveal solutions that approximate true remediation, even within existing political systems, rather than simply reparation. For example, it can highlight governments’ responsibilities to restore and return illegally acquired land to Indigenous peoples rather than providing arbitrary compensation that fails to genuinely address the initial injustice.

Our tool creates space for rethinking political systems and decision-making processes based on epistemologies of coordination that enable all our relations to express agency as part of an inclusive, multispecies justice. There are significant challenges in realizing this vision and powerful interests invested in upholding the status quo, underscoring the need for not just theoretical and analytical contributions but also co-ordinated action to remove barriers to Indigenous climate justice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the advisory group: Dr Shaun Awatere (Ngāti Porou), a research impact leader at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research and Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, New Zealand’s Māori Centre of Research Excellence, whose work involves the integration of Māori knowledge and values into economic decision-making and environmental planning; Dr Fiona Cram (Ngāti Pahauwera), a researcher and evaluator with expertise in Kaupapa Māori research whose work spans a wide range of areas including Māori health, justice, education and family wellbeing; Garth Harmsworth (Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Raukawa), a senior environmental scientist at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research with research expertise in the areas of ecosystem health, bio-physical and cultural indicators, climate change, and sustainable resource management based on Indigenous knowledge and values, and; Professor Helen Moewaka Barnes (Te Kapotai, Ngāpuhi-nui-tonu), Director of Whāriki Research Centre, who has a strong track record in developing research within Māori paradigms, particularly focusing on relationships between the health of people and the health of environments. We would like to thank the reviewers for the very constructive reviews that have helped to strengthen this manuscript. We acknowledge Indigenous Peoples everywhere, whose ways of knowing, doing, and being, grounded in relationality with the Earth, Sky and all their inhabitants, hold the key for climate justice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abram, S., Atkins, E., Dietzel, A., Jenkins, K., Kiamba, L., Kirshner, J., Kreienkamp, J., Parkhill, K., Pegram, T., & Santos Ayllón, L. M. (2022). Just transition: A whole-systems approach to decarbonisation. Climate Policy, 22(8), 1033–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2108365

- Akchurin, M. (2015). Constructing the rights of nature: Constitutional reform, mobilization, and environmental protection in Ecuador. Law & Social Inquiry, 40(4), 937–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsi.12141

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Arvin, M., Tuck, E., & Morrill, A. (2013). Decolonizing feminism: Challenging connections between settler colonialism and heteropatriarchy. Feminist Formations, 25(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/ff.2013.0006

- Bargh, M. (2019). A tika transition. In D. Hall (Ed.), A careful revolution towards a low-emissions future (pp. 36–51). Bridget Williams Books.

- Bargh, M., & Tapsell, E. (2021). For a Tika Transition: Strengthen rangatiratanga. Policy Quarterly, 17(3), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v17i3.7126

- Bennett, N. J., Blythe, J., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Singh, G. G., & Sumaila, U. R. (2019). Just transformations to sustainability. Sustainability, 11(14), 3881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143881

- Came, H., O’Sullivan, D., Kidd, J., & McCreanor, T. (2023). Critical Tiriti Analysis: A prospective policy making tool from Aotearoa New Zealand. Ethnicities, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968231171651

- Celermajer, D., Schlosberg, D., Rickards, L., Stewart-Harawira, M., Thaler, M., Tschakert, P., Verlie, B., & Winter, C. (2021). Multispecies justice: Theories, challenges, and a research agenda for environmental politics. Environmental Politics, 30(1-2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1827608

- Ciplet, D., & Harrison, J. L. (2020). Transition tensions: Mapping conflicts in movements for a just and sustainable transition. Environmental Politics, 29(3), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1595883

- Coulthard, G. S. (2007). Subjects of empire: Indigenous peoples and the ‘politics of recognition’ in Canada. Contemporary Political Theory, 6(4), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cpt.9300307

- Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749j.ctt9qh3cv

- Cullinan, C. (2021). Earth jurisprudence. In L. Rajamani & J. Peel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of international environmental Law (pp. 233–C14.S24). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/law/9780198849155.003.0014

- Curtis, E. (2016). Indigenous positioning in health research: The importance of Kaupapa Māori theory informed practice. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 12(4), 396–410. https://doi.org/10.20507/AlterNative.2016.12.4.5

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Willing, E., Anderson, A., Paine, S.-J., Herbert, S., Loring, B., Dalgic, G., & Reid, P. (2023). Indigenous adaptation of a model for understanding the determinants of ethnic health inequities. Discover Social Science and Health, 3(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-023-00040-6

- Davis, H., & Todd, Z. (2017). On the importance of a date, or, decolonizing the anthropocene. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 16(4), 761–780.

- Donoso, A. (2017). Representing non-human interests. Environmental Values, 26(5), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327117X15002190708137

- Fleras, A., & Maaka, R. (2010). Indigeneity-grounded analysis (IGA) as policy (making) lens: New Zealand models, Canadian realities. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 1(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2010.1.1.4

- Gilio-Whitaker, D. (2020). As long as grass grows: The indigenous fight for environmental justice, from colonization to Standing Rock. Beacon Press.

- He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission. (2021). Ināia tonu nei: A low emissions future for Aotearoa. Advice to the New Zealand Government on its first three emissions budgets and direction for its emissions reduction plan 2022–2025. https://www.climatecommission.govt.nz/our-work/advice-to-government-topic/inaia-tonu-nei-a-low-emissions-future-for-aotearoa/

- Heyen, D. A. (2023). Social justice in the context of climate policy: Systematizing the variety of inequality dimensions, social impacts, and justice principles. Climate Policy, 23(5), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2142499

- Hickel, J. (2020). Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: An equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(9), e399–e404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30196-0

- Humphreys, D. (2017). Rights of Pachamama: The emergence of an earth jurisprudence in the Americas. Journal of International Relations and Development, 20(3), 459–484. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-016-0001-0

- Hunt, P., & Backman, G. (2008). Health systems and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Health and Human Rights, 10(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/20460089

- Hurlbert, M., & Rayner, J. (2018). Reconciling power, relations, and processes: The role of recognition in the achievement of energy justice for Aboriginal people. Applied Energy, 228, 1320–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.06.054

- Hutchings, J., Smith, J., Taura, Y., Harmsworth, G., & Awatere, S. (2020). Storying kaitiakitanga: Exploring kaupapa Māori land and water food stories. MAI Journal: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship, 9(3), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.20507/MAIJournal.2020.9.3.1

- IPCC. (2015). Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change: Working group III contribution to the IPCC fifth assessment report. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

- Jones, C. (2010). Tino Rangatiratanga and Sustainable Development: Principles for Developing a Just and Effective System of Environmental Law in Aotearoa [Victoria University of Wellington Legal Research Paper No. 7/2016]. Journal of Māori Legal Writing (Te Tai Haruru), 3, 59–74.

- Jones, R. (2019). Climate change and Indigenous Health Promotion. Global Health Promotion, 26(3_suppl), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975919829713

- Jones, R., Macmillan, A., & Reid, P. (2020). Climate change mitigation policies and co-impacts on Indigenous health: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 9063. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239063

- Jones, R., Reid, P., & Macmillan, A. (2022). Navigating fundamental tensions towards a decolonial relational vision of planetary health. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(10), e834–e841. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00197-8

- Juhola, S., Heikkinen, M., Pietilä, T., Groundstroem, F., & Käyhkö, J. (2022). Connecting climate justice and adaptation planning: An adaptation justice index. Environmental Science & Policy, 136, 609–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.07.024

- Kaufman, A. (2012). Distributive justice, theories of. In R. Chadwick (Ed.), Encyclopedia of applied ethics (2nd ed., pp. 842–850). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373932-2.00227-1

- Krieger, N. (2011). Ecosocial theory of disease distribution: Embodying societal & ecologic context. In Epidemiology and the people’s health: Theory and context (pp. 202–235). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195383874.003.0007

- Lawson-Te Aho, K. (1995). A Māori policy analysis framework for the Ministry of Health.

- Mahuika, M. (2008). Kaupapa Māori Theory is critical and anti-colonial. MAI Review, 3(Article 4), 1–16.

- Markkanen, S., & Anger-Kraavi, A. (2019). Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality. Climate Policy, 19(7), 827–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1596873

- Matike Mai Aotearoa. (2016). He Whakaaro Here Whakaumu Mō Aotearoa: The Report of Matike Mai Aotearoa - the Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation. https://nwo.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/MatikeMaiAotearoa25Jan16.pdf

- McCauley, D., & Heffron, R. (2018). Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy, 119, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

- McCauley, D., Ramasar, V., Heffron, R. J., Sovacool, B. K., Mebratu, D., & Mundaca, L. (2019). Energy justice in the transition to low carbon energy systems: Exploring key themes in interdisciplinary research. Applied Energy, 233-234, 916–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.005

- McGregor, D. (2009). Honouring our relations: An Anishnaabe perspective on environmental justice. In J. Agyeman, P. Cole, R. Haluza-DeLay, & P. O’Riley (Eds.), Speaking for ourselves: Environmental justice in Canada (pp. 27–41). UBC Press.

- McGregor, D. (2018). Indigenous environmental justice, knowledge and law. Kalfou Journal of Comparative and Relational Ethnic Studies, 5(2), 279–296.

- McGregor, D., Whitaker, S., & Sritharan, M. (2020). Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 43, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.007

- McGurty, E. M. (1997). From NIMBY to civil rights: The origins of the environmental justice movement. Environmental History, 2(3), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.2307/3985352

- Mikaere, A. (2011). Colonising myths–Māori realities: He rukuruku whakaaro. Huia Publishers.

- Milroy, H., Derry, K., Kashyap, S., Platell, M., Alexi, J., Chang, E., & Dudgeon, P. (2023). Indigenous Australian understandings of holistic health and social and emotional wellbeing. In E. Rieger, R. Costanza, I. Kubiszewski, & P. Dugdale (Eds.), Toward an integrated science of wellbeing (pp. 158–177). Oxford University Press.

- Ministry of Health. (2007). Whānau ora health impact assessment.

- Moewaka Barnes, H. (2000). Kaupapa maori: Explaining the ordinary. Pacific Health Dialog, 7(1), 13–16.

- Moewaka Barnes, H. (2013). Better indigenous policies: An Aotearoa New Zealand perspective on the role of evaluation. In Better Indigenous Policies: The Role of Evaluation, Roundtable Proceedings (pp. 155–182). Productivity Commission. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/better-indigenous-policies/12-better-indigenous-policies-chapter10.pdf

- Newell, P., Srivastava, S., Naess, L. O., Torres Contreras, G. A., & Price, R. (2021). Toward transformative climate justice: An emerging research agenda. WIRES Climate Change, 12(6), e733. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.733

- Nilsson, C. (2008). Climate change from an indigenous perspective: Key issues and challenges. In Indigenous affairs, climate change and indigenous peoples (Vol. 1-2/08, pp. 8–15). IWGIA. https://www.iwgia.org/images/publications//IA%201-2_08_Climate_Change_from_ind_perspective.pdf

- Parsons, M., Fisher, K., & Crease, R. P. (2021). Environmental justice and Indigenous environmental justice. In Decolonising blue spaces in the Anthropocene: Freshwater management in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 39–73). Palgrave Macmillan Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61071-5_2

- Pellow, D. N. (2021). Global environmental and climate justice movements. In E. Laurent & K. Zwicki (Eds.), The routledge handbook of the political economy of the environment (pp. 75–89). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367814533

- Pihama, L. (2010). Kaupapa Māori theory: Transforming theory in Aotearoa. He Pukenga Kōrero, 9(2), 5–14.

- Povall, S. L., Haigh, F. A., Abrahams, D., & Scott-Samuel, A. (2014). Health equity impact assessment. Health Promotion International, 29(4), 621–633. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat012

- Ratima, M., Martin, D., Castleden, H., & Delormier, T. (2019). Indigenous voices and knowledge systems – promoting planetary health, health equity, and sustainable development now and for future generations. Global Health Promotion, 26(3_suppl), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975919838487

- Redvers, N. (2018). The value of global Indigenous knowledge in planetary health. Challenges, 9(2), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe9020030

- Redvers, N., Celidwen, Y., Schultz, C., Horn, O., Githaiga, C., Vera, M., Perdrisat, M., Mad Plume, L., Kobei, D., Kain, M. C., Poelina, A., Rojas, J. N., & Blondin, B. s. (2022). The determinants of planetary health: an Indigenous consensus perspective. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(2), e156–e163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00354-5

- Redvers, N., Poelina, A., Schultz, C., Kobei, D. M., Githaiga, C., Perdrisat, M., Prince, D., & Blondin, B. (2020). Indigenous natural and first Law in planetary health. Challenges, 11(2), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe11020029

- Reeves, J.-A., & Peters, T. D. (2021). Responding to anthropocentrism with anthropocentrism: The biopolitics of environmental personhood. Griffith Law Review, 30(3), 474–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2022.2037882

- Royal, T. A. C. (2005, June 25). Exploring indigenous knowledge [paper presentation]. The Indigenous Knowledges Conference - Reconciling Academic Priorities with Indigenous Realities, Wellington, New Zealand. http://www.charles-royal.nz/s/Exploring-Indigenous-Knowledge

- Ruano-Chamorro, C., Gurney, G. G., & Cinner, J. E. (2022). Advancing procedural justice in conservation. Conservation Letters, 15(3), e12861. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12861

- Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199286294.001.0001

- Schlosberg, D. (2013). Theorising environmental justice: The expanding sphere of a discourse. Environmental Politics, 22(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755387

- Schlosberg, D., & Collins, L. B. (2014). From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. WIRES Climate Change, 5(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.275

- Signal, L., Martin, J., Cram, F., & Robson, B. (2008). The health equity assessment tool: A user's guide. Ministry of Health.

- Simpson, S., Mahoney, M., Harris, E., Aldrich, R., & Stewart-Williams, J. (2005). Equity-focused health impact assessment: A tool to assist policy makers in addressing health inequalities. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 25(7), 772–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2005.07.010

- Smith, L. (2012). Decolonising methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books Ltd.

- Sovacool, B. K. (2021). Who are the victims of low-carbon transitions? Towards a political ecology of climate change mitigation. Energy Research & Social Science, 73, 101916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.101916

- Sula-Raxhimi, E., Butzbach, C., & Brousselle, A. (2019). Planetary health: Countering commercial and corporate power. The Lancet Planetary Health, 3(1), e12–e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(18)30241-9

- Tauli-Corpuz, V., & Aqqaluk, L. (2008). Impact of climate change mitigation measures on indigenous peoples and on their territories and lands [Report to the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Seventh session, New York, 21 April-2 May 2008]. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/E_C19_2008_10.pdf

- Tschakert, P. (2022). More-than-human solidarity and multispecies justice in the climate crisis. Environmental Politics, 31(2), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1853448

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

- Ulloa, A. (2017). Perspectives of environmental justice from indigenous peoples of Latin America: A relational indigenous environmental justice. Environmental Justice, 10(6), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2017.0017

- United Nations. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. United Nations.

- Visvanathan, S. (1997). A carnival for science: Essays on science, technology, and development. Oxford University Press.

- Waitangi Tribunal. (2011). Ko Aotearoa Tēnei: A Report into Claims Concerning New Zealand Law and Policy Affecting Māori Culture and Identity. https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68356054/KoAotearoaTeneiTT1W.pdf

- Waitangi Tribunal. (2019). Hauora: Report on stage one of the health services and outcomes Kaupapa inquiry (Report no. WAI 2575). https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_152801817/Hauora%20W.pdf

- Walker, S., Eketone, A., & Gibbs, A. (2006). An exploration of kaupapa Māori research, its principles, processes and applications. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 9(4), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570600916049

- Weaver, H. N. (2009). The colonial context of violence: Reflections on violence in the lives of Native American women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(9), 1552–1563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508323665

- White, D., & Leining, C. (2021). Developing a policy framework with indicators for a ‘just transition’ in Aotearoa New Zealand. Policy Quarterly, 17(3), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v17i3.7125

- Whyte, K. (2011). The recognition dimensions of environmental justice in Indian country. SSRN Electronic Journal, 4(4), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1855591

- Whyte, K. P. (2017). Indigenous climate change studies: Indigenizing futures, decolonizing the anthropocene. English Language Notes, 55(1-2), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1215/00138282-55.1-2.153

- Whyte, K. (2018). Settler colonialism, ecology, and environmental injustice. Environment and Society, 9(1), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2018.090109

- Whyte, K. P. (2019). Way beyond the lifeboat: An Indigenous allegory of climate justice. In K.-K. Bhavnani, J. Foran, P. A. Kurian, & D. Munshi (Eds.), Climate futures: Reimagining global climate justice (pp. 11–20). Bloomsbury Academic & Professional.

- Whyte, K. (2020). Too late for indigenous climate justice: Ecological and relational tipping points. WIRES Climate Change, 11(1), e603. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.603

- Whyte, K. (2021a). Indigenous environmental justice: Anti-colonial action through kinship. In B. Coolsaet (Ed.), Environmental justice: key issues (pp. 266–278). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Whyte, K. (2021b). Against crisis epistemology. In B. Hokowhitu, A. Moreton-Robinson, L. Tuhiwai-Smith, C. Andersen, & S. Larkin (Eds.), Handbook of critical indigenous studies (pp. 52–64). Routledge.

- Williams, S., & Doyon, A. (2019). Justice in energy transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2018.12.001

- Williams, D., & Mohammed, S. (2013). Racism and health 1: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1152–1173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487340

- Wilson, D., Moloney, E., Parr, J. M., Aspinall, C., & Slark, J. (2021). Creating an Indigenous Māori-centred model of relational health: A literature review of Māori models of health. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(23-24), 3539–3555. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15859

- Winter, C. J. (2019). Decolonising dignity for inclusive democracy. Environmental Values, 28(1), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327119X15445433913550

- Winter, C. J. (2021). A seat at the table. Borderlands Journal, 20(1), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.21307/borderlands-2021-005

- World Health Organization. (2013). Health in all policies. Seizing opportunities, implementing policies. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/188809/Health-in-All-Policies-final.pdf