ABSTRACT

This paper explores whether, to what extent and in what ways climate change is represented as ecocide in scholarly literature. Premised upon a historical materialist lens utilizing the world systems theory and the concept of the Capitalocene, and by means of conducting a scoping literature review, the paper finds there is an increasing trend of climate change representation as ecocide. It also identifies several key themes that emerge in scholarly representations, including the growth-driven global capitalistic and nation-state system that perpetuates carbon criminals, anthropocentric ethics, and environmental and social harm and injustice, and the feasibility and appropriateness of an international crime of ecocide. The analysis suggests that while not likely to catalyze fossil phase-out and expedite the global energy transition decisively, the criminalization of ecocide could fortify the climate policy toolbox via the prospect to report cases to the International Criminal Court, the issuance of warrant arrests by the ICC, and EU’s criminalization of substantial environmental damage and potential externalization of its criminal code. The significance and originality of this article lies in the generation of robust empirical evidence, the mapping of representations of climate change as ecocide, and a comprehensive analysis of the practical, ethical and legal complexities surrounding a law of ecocide and its implications for global climate policy.

Key policy insights

Representations of climate change as ecocide focus on the global capitalistic and nation-state system that perpetuates carbon criminals, anthropocentric ethics, and environmental and social harm and injustice.

An international law of ecocide will challenge both fossil-based and energy transition practices.

The power of the state-corporate nexus and the socio-economic benefits emanating from acts that contribute to climate change weaken the case for and undermine the potential effectiveness of an international crime of ecocide.

While not a panacea, the criminalization of ecocide can add to the climate policy toolbox via building the momentum for more states to adopt relevant domestic legislation, the prospect to report cases to the ICC, the issuance of warrant arrests by the ICC, and EU’s criminalization of substantial environmental damage and potential externalization of its criminal code.

1. Introduction

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, established in 1992, constitutes the main international law-making venue for climate change mitigation. Annual Conferences of Parties have produced an extensive body of law, ranging from the Kyoto Protocol to the nationally determined contributions of the Paris Agreement and the creation of a Loss and Damage Fund (Kuyper et al., Citation2018; Rajamani & Peel, Citation2021). Nevertheless, these legal agreements have not led to effective climate change mitigation as annual global emissions are still on the increase. Current projections show that humanity is set to miss the goal of limiting global temperature increase to 2, let alone 1.5, degrees Celsius as agreed in the Paris Agreement (IPCC Citation2021).

In this context, pleas for states to adopt a crime of ecocide in their domestic penal codes and for the establishment of an international crime of ecocide have gathered strength over the previous decade. The term ‘ecocide’ comes from the Greek word ‘oikos’, which stands for home, and from the Latin word ‘caecere’, which means kill. Ecocide, hence, refers to nothing less than the killing of our home, the earth. Higgins et al. (Citation2012, p. 4) defined ecocide as ‘the extensive damage to, destruction of or loss of ecosystem(s) of a given territory, whether by human agency or by other causes, to such an extent that peaceful enjoyment by the inhabitants of that territory has been severely diminished’. More recently, the Promise Institute for Human Rights of the UCLA School of Law (Citation2021) defined ecocide as ‘acts, committed with the knowledge that they are likely to cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment’. The Independent Expert Panel (IEP) convened by the Stop Ecocide Foundation defined ecocide as ‘unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts’ (Stop Ecocide International, Citation2021).

The rationale behind this plea is that the hardening of domestic and international environmental law is essential for effective climate change mitigation, since soft law and coalitions of the willing-type of arrangements have not delivered the expected results and time is running out (Higgins et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, a rich body of literature casts doubt both on the normative and philosophical underpinnings of the institutionalization of a crime of ecocide (Lindgren, Citation2023) as well as on its anticipated effectiveness in the fight against climate change (Ambos Citation2021; Heller Citation2021; Killean and Short Citation2023; Lindgren, Citation2023; Minkova Citation2023; Robinson, Citation2022). More specifically, Lindgren (Citation2023) argues that an anthropocentric, western-made, universalizing law of ecocide defies indigenous knowledge, law, tradition and treatments of nature, and will hence entrench and codify further the abstract divide between humans and nature, leading to solutions that fail to take into account ‘a mosaic of laws and woven legal relationships already existing in place’ (Lindgren, Citation2023, p. 318).

Such a stark philosophical objection, together with the renewed scholarly and political interest in the institutionalization of ecocide to fight climate change within very pressing timeframes, makes it worthwhile to unpack how ecocide and climate change are conceptually brought together, in what ways and under what premises. Although there are some conceptual studies on ecocide, there is a lack of empirical research on representations of climate change as ecocide in scholarly literature. We aim to cover some distance in filling this gap by investigating the evolution of the representations of climate change as ecocide through a scoping literature review. We opted methodologically for a scoping literature review, as this allows us to explore the extent, range and nature of the relevant cross-disciplinary literature with an eye to trace the main themes/concepts through which climate change is represented as ecocide. The themes generated will serve as keys to map representations of climate change as ecocide with recourse to specific values, intellectual traditions and disciplinary interests. Using a critical historical materialist lens, we aim to deepen cross-disciplinary research in the climate change-ecocide nexus, and contribute to an appraisal of both recent legal efforts to institutionalize ecocide as an international crime and implications for climate policy. To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first empirical study to map representations of climate change as an international crime in the scholarly literature.

By representations, we mean social constructions of ‘reality from a particular perspective comprising certain evaluative patterns and value judgements’ (Chiluwa & Chiluwa, Citation2022, p. 6). Representations thus have normative underpinnings and constitute mental maps and schemata of interpretation that produce concrete meaning and establish the boundaries of terms. In this context, in what ways climate change and ecocide are commonly perceived and interlinked, and via which other concepts they come together is useful as a means to further calibrate our understanding of climate change as ecocide, its foundations and (policy) implications. This is so because diverse representations shed light on different aspects/ properties of social phenomena, thus distilling their significance while muting/ downplaying this of other aspects. Subsequently, moreover, the way problems are conceived and represented has a direct bearing on the solutions selected. Representations hence are key to both understanding and organizing solutions to problems (Bacchi Citation2012).

We proceed as follows. In Section 2, we present the analytical framework of the world systems theory and the Capitalocene as a lens through which ecocide can be understood and the findings of the empirical research dissected. In Section 3, we set out the methodology. In Section 4, we present the findings in terms of scholarly trends, disciplinary interests, and gaps in the literature. We also generate ten key themes through which climate change and ecocide are conceptually linked together. In Section 5, we delve into the practical, ethical, and legal complexities of a law of ecocide and its climate policy implications. In Section 6 we conclude, summarizing the key findings and their significance for future research avenues.

2. Literature review

Climate change is a defining characteristic of the Anthropocene era, the latter connoting the epoch in which human intervention constitutes a geophysical force and hence a prime mover of biophysical developments (Crutzen, Citation2006). The concept of the Anthropocene, however, takes implicitly as its unit of analysis humanity as a unitary force that works in one specific direction. This yields injustice to the majority of people who are objects, rather than subjects, and victims rather than perpetrators. The concept of the Capitalocene, to the contrary, takes as its unit of analysis the global political and economic system and the spread of capitalism as the prime driver. In this understanding, it has been capital accumulation, the expansion of the profit rationale, and constant human ingenuity to push further biophysical limits with an eye to expand markets, that has defined the trajectory of the last centuries and led to anthropogenic climate change (Jansen & Jongerden, Citation2021; Moore, Citation2015).

The Capitalocene concept chimes with the world systems theory that also positions the expansion of capitalism centre-stage and explains the workings of global politics as a result of the global strive for capital accumulation. Immanuel Wallerstein (Citation2020) has demonstrated how capitalism has brought continents and countries together in transnational value chains and webs of (inter)dependence that cannot be understood outside the capitalistic logic. Security policies have also marshalled behind capitalistic prerogatives and actively supported extra-territorial capitalistic ventures that intertwined states in geopolitical strife and chains of dependency. Wallerstein’s (Citation1995) taxonomization of states into core, semi-periphery and periphery crystallizes how capitalistic forces allocate costs and benefits disproportionately and generate winners and losers thus yielding gross global inequalities and injustice.

The appropriation of nature via political artefacts such as property and sovereignty and the abuse of the global ecosystem by the human species has accelerated exponentially since the take-off of the Industrial Revolution and the proliferation of capitalistic practices across the globe, and climaxed with the triumph of neo-liberalism since the 1970s, defined as a market-based governance model premised upon the belief that markets optimize economic results for society (Ganti, Citation2014, p. 91). Evidenced in the crossing of critical planetary boundaries for most vital environmental indices and in runaway climate change, the abuse of the earth through human mastery showcases the interconnectedness of humans and nature. Latour’s (Citation2007) actor network theory demonstrates how human and non-human actors interrelate at a material and conceptual level to co-produce reality. The environmental destruction of ecosystems that were brought into the capitalistic sphere and enlisted into the capitalistic logic of enclosure and commodification contrasts sharply with those ecosystems untouched by capitalistic fervour, with indigenous populations able to retain a relationship of mutual respect and support with their lands. Contrary to mainstream western thought that has artificially divided the human from the non-human and allowed for the former ultimate powers to dominate over and abuse the latter, talk about the rights of the earth, critique of anthropocentrism and speciesism and deep ecological thinking have increasingly gained ground (Kammerer, Citation2011).

It is within this evolving conceptual environment of critique to global capitalism and the destructive forces it unleashes for the planet, global ecosystems, and other species, with mounting evidence of anthropogenic climate change, that criminological understandings of climate change as ecocide have emerged in the scholarly realm. Criminological representations of climate change as ecocide contrast sharply with mainstream representations of climate change as a market problem, which hence can be solved through market mechanisms (Dalby, Citation2015; Kuzemko et al., Citation2015; Proedrou, Citation2018; Van de Graaf & Sovacool, Citation2020); a (geo)political problem that passes through industrial policy, state intervention, and climate change negotiations (Blondeel et al., Citation2021; Falkner, Citation2016; Giddens Citation2011); and, a socio-technological issue that calls for innovation, entrepreneurship, technology take-up and public policy support (Geels, Citation2014; Geels et al., Citation2017). Carbon offsets and markets and the Clean Development Mechanism are examples of a neoliberal/market representation of climate change. The US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU Green Deal Industrial Plan and Net-Zero Industry Act are examples of a geopolitical representation of climate change, while public-private partnerships and industrial clusters are examples of socio-technological representations (Proedrou, Citation2022). What these mainstream representations of climate change have in common is their rootedness into the global capitalistic logic, with countries and companies endorsing capital accumulation, expansion to new resources frontiers and associated technological innovation to support the capitalistic engine. The spiralling increase of global emissions, however, and the dire predictions of climate science have enlarged the space for the development of contesting narratives and representations of climate change as a global problem. The next section presents the methodology for the review of the criminological representations of climate change as ecocide.

3. Methodology

To investigate representations of climate change as ecocide, we conducted a scoping literature review. A scoping review is used to summarize or map a range of evidence to convey the breadth and depth of a field (Snaphaan & Hardyns, Citation2021). It differs from a systematic review because the quality of the included studies is not typically assessed, and it differs from a narrative literature review because the scoping process ‘requires analytical reinterpretation of the literature’ (Levac et al., Citation2010, p. 1). To that end, this study aims to identify and report patterns within the scholarly representation of the issue under study, trace the main concepts/themes/lenses through which climate change is linked with ecocide, taxonomize and present data, and map them onto an interdisciplinary scholarly grid. This will help unpack the principal conceptual ways in which climate change is perceived as ecocide, the main intellectual premises and arguments bringing the two concepts together, the objections raised to such representations, as well as the solutions suggested emanating from a criminological understanding of climate change. It will also help clarify the potential of such a law, legal and ethical complexities, and the implications for climate policy. In so doing, the analysis offers an invaluable departure point for critical discussion around the underpinnings and shape of an international crime of ecocide and can thus be of benefit to NGOs lobbying for this cause to further calibrate their stand, as well as to policy-makers increasingly confronted with pleas to institutionalize a law of ecocide. It also advances the scholarly debate on climate change as ecocide and on the implications of an international crime of ecocide for climate policy.

We initially conducted a search of the first 200 results (out of more than 11,000 in total) that appeared in the Googlescholar database with the keywords ‘climate change ecocide’. This initial scan allowed us to identify some core published articles and get a general sense of which disciplines and academic realms have engaged with the topic from their own disciplinary angle. To be able to conduct a feasible scoping review we were faced with the need to cut down on the number of results. We hence decided to conduct a more focused search in two databases. As we are departing from the Humanities and Social Sciences, and more specifically from the fields of criminology, law, politics and energy, we created a complex search with the following characteristics:

Essential keywords Climate change ecocide

Plus crime OR politics OR energy OR justice OR policy

Excluding drama – theater – collapse – easter – island – archaeology – ethnography – biodiversity – music – education – ecology – health – urban

The exclusion criteria stemmed from the broader understanding we acquired through the initial scan and allowed us to exclude several papers that dealt with the issue but in ways not relevant with our research project, questions and aims (for example, a number of papers focused on the collapse of previous civilizations, with the majority focusing on Easter Island). The inclusion criteria, on the other hand, ensured that the articles identified would be relevant to our research aims. Subsequently, we run this search both in Googlescholar and Scopus databases. Overall, the search yielded 533 results. Out of those, we focused exclusively on journal articles as those are the main forum for original research. At the same time, we excluded papers in languages other than English, gray literature (this appears in Googlescholar searches), book reviews and review articles, books and book chapters, and any other documents outside peer-reviewed journal articles (such as theses, blogs etc.) and duplicates. We also excluded articles, where the term ecocide was only mentioned in references or were considered irrelevant to the study (e.g. articles that mention ecocide but outside the climate change context/ social sciences perspective, or whose focus has been totally different, e.g, wolves hunting in Norway). Excluding the above, at the end of the review process 75 articles were included in our final selection, on which our study focuses.

4. Findings

From the 75 papers we identified, the majority emanated from politics (27), (critical) criminology (17), and law (16). The stream of ecology yielded 4 results, with the other disciplines yielding a maximum of three entries. illustrates the articles identified per discipline.

Table 1. Articles exploring climate change as ecocide per discipline.

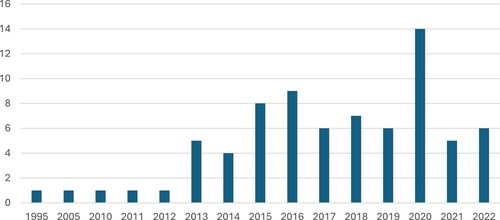

In terms of temporal representation, most of the articles were published since 2013. summarizes the data. What is easily discernible is a rise in publications in the early 2010s, when scholarly activism around the idea of ecocide started taking solid grounds. Scholarly interest in ecocide correlates with the submitted proposal for ecocide to be enshrined in international law as the fifth international crime, and in many cases relevant publications discuss ecocide under the lens of a legal proposal and its ramifications.

We also taxonomized the identified papers in two categories. In the first (A), we inserted the papers that conceptualized and operationalized the term, or at least used a given conceptualization/ operationalization provided in others’ work. Overall, 35 papers sit in this category. In the second category (B), we taxonomized articles that mention ecocide within the core text but only in passing, without operationalizing/ conceptualizing the term. 40 articles sit in this category.

Several important findings can be drawn from the scoping literature review we undertook. First, interest exists outside the English scholarly debate with scholarly work undertaken in the Spanish and German languages especially. Non-English work reached 105 results out of our 533 initial results, standing marginally below 20%.

Second, the bulk of the identified articles comes from three disciplines. Law, Politics and Critical Criminology together account for 60 out of the 75 articles included in our research. While this also reflects our search strategy, it does pay lip service to the increasing interest of these disciplines in this issue. Articles from within the law discipline have an overly normative underpinning making a clear case in favour of ecocide, on political and legal grounds. Critical criminology is the discipline with the second highest results, a result that is unsurprising if we think of the nature and object of the study, the representation of climate change as ecocide. As Higgins et al. (Citation2012, p. 4) wrote:

criminology has often played a crucial role in ensuring law is appropriate to its time and that entitlement to rights and justice is fair and comprehensive … questioning the ‘taken for granted’ nature of definitions and classifications of crime, deviance and harm, offering alternative proposals about where concern and regulation should be directed.

A surprising outcome was the relative absence of energy policy papers from our research. While some identified articles explore renewable energy projects and their impact, they do so from the lens of a different discipline (e.g. critical criminology, politics). This means that energy policy scholars do not (yet) problematize/operationalize ecocide as a departure point/conceptual underpinning of their work on energy transition.

Moving beyond disciplinary and to broader findings, we have identified several central themes. The dominant theme undercutting the representation of climate change as ecocide is harm, and loss and damage. Scholars who illustrate climate change as a crime define the parameters within which specific actions can come within this category. It is hence clarified that large-scale damage that is hard to reverse and makes life maintenance increasingly hard can qualify as ecocidal (Higgins et al., Citation2012). This way, ecocide is restricted to the most severe actions contributing to climate change, not to small acts creating limited damage. Moreover, the proposal targets ecocidal processes emanating from human activity, and especially those perpetrated by the most important players in the system. A criminological understanding of ecocide especially utilizes the concept of carbon criminals to distinguish the big state-corporate organizations as the actors that systematically engage in actions that colossally contribute to climate change (White, Citation2017). According to the proponents of a law of ecocide, these actors should be subject to strict liability so that further criminal action is effectively deterred. In this reading, it is irrelevant if perpetrators have the intention to provoke harm and/ or are aware of the repercussions of their actions (Higgins et al., Citation2013; White, Citation2018b). In the cases of states and state-owned corporations perpetrating such crimes, moreover, an international crime of ecocide is seen as the means to reinforce their legal duty of care for the environment and in doing so create and foster solid liability-accountability links.

This raises another theme prominent in the literature, the structure vs. agency debate. Since climate change is a systemic issue, but systems themselves cannot be prosecuted, and in current environmental law only individuals can be prosecuted, the campaign for an international crime of ecocide targets the prosecution of individuals in their professional capacity, as CEOs, Directors of Boards and government officials, as a means to target, penalize and disincentivize governments and corporations from persisting to perpetuate ecocidal acts (Gray, Citation1995; Greene, Citation2018; White, Citation2018a, for a contrary opinion see Gunderson & Fyock, Citation2022).

On the receiving end of ecocide lie both humans and the non-human species and environment. Starting with the latter, the literature illustrates the importance of ethics underpinning the debate on climate change as ecocide. It showcases how current international environmental law is essentially based on an anthropocentric approach, while climate change necessitates an ecocentric perspective that treats humans as one part of the world ecosystem. In the Anthropocene/Capitalocene era, where humans have become the main force of ecological change, an ecological integrity framework is essential to mitigate the destruction of ecological services upon which human well-being depends (Burke, Citation2016; Mwanza, Citation2018; White, Citation2018a).

In regards to the human victims of ecocide, the most vulnerable countries, and people across countries, are the ones who suffer most from ongoing change of vital ecosystem processes. This makes issues of equality and justice, including intergenerational justice, a central theme in the debate. The focus is on the most vulnerable states of the world, whose very existence over the next decades has been cast in doubt due to ongoing climate change, as well as future generations that are under- or unrepresented and will inherit a planet in a dismal state (Crook et al., Citation2018; Gray, Citation1995; White, Citation2017). Importantly, a substantial part of ecocidal literature zooms in on the plight of indigenous populations, who tend to suffer the most both from the direct consequences of climate change and the actions causing it (e.g. deforestation), as well as from energy transition practices that involve encroachment and enclosure of their territories for land use change (building of renewable parks etc.). The result is that these populations are on the receiving end of economic, social and cultural harm, in many cases to such an extent that they are essentially kicked off from their lands and lacking the necessary means of survival, what amounts to genocide of indigenous people for many scholars (Crook et al., Citation2018; Dunlap, Citation2018; Lynch et al., Citation2018).

Critical/green criminology scholarship in particular premises its study of ecocide upon the neo-liberal global capitalistic system, tracing its roots to medieval age imperialism and colonialism through to modernity and the Industrial Revolution (Crook et al., Citation2018; Gray, Citation1995; White, Citation2017). The twin pillar of the current exploitative global system is the nation-state system, with the central principle of sovereignty and entrenched priorities of national security and development being on the driving seat of ecocidal processes that cause climate change (Adelman, Citation2015; Walters, Citation2022). An important theme within this context is the obsession with growth, a central goal of all nation-states, entrenched over the twentieth century, which essentially commits states around the world to resource extractivism and rates of use of natural resources beyond the biophysical capacity (Adelman, Citation2015; Gray, Citation1995).

A last prominent issue raised in the debate is the feasibility of the proposal to render actions contributing to climate change liable to prosecutions and the appropriateness of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to serve as the institutional space for this, as well as the examination of alternatives (Greene, Citation2018; Robinson, Citation2022; Tavoa, Citation2021). Many scholars point to the end of slavery, apartheid and women’s emancipation as examples where radical shifts have been enshrined in law against the odds. For these scholars, the proposal to make ecocide the fifth international crime is feasible, and the ICC naturally constitutes the appropriate forum (Higgins et al., Citation2012; Mehta & Merz, Citation2015). Others, however, argue that the grounds of optimism are limited, as the power of the state-corporate nexus, and the overload and nature of the ICC (lacking specialized environmental judges) make reception of this crime a remote possibility (Greene, Citation2018; Robinson, Citation2022; Tavoa, Citation2021). Robinson (Citation2022) and Greene (Citation2018) hence ponder whether alternative strategies may be more effective, while holding the same grand symbolic significance. Advancing relevant domestic legislation is one such option. Greene (Citation2018) provides the examples of Guatemala and Kyrgyzstan, two pioneers in institutionalizing ecocide. Nevertheless, she admits that despite the legal standing of ecocide in these countries, the cases brought to the courts have been halted for lack of evidence and due to strong political pressure and corporate intimidation tactics, thus arguing that an international law of ecocide could have retained the momentum for prosecution. Alternative forums (such as a separate Environmental Criminal Court) and bottom-up approaches, such as a fossil fuels-free zone enacted upon by the most vulnerable states, the institutionalization of a convention of ecocide, and a coalition of states willing to treat ecocide as an international crime also constitute potential alternatives. This is all the more the case with the coming into force of relevant domestic legislation in Belgium, Chile and the EU, and with more states, such as Sweden, Brazil and Spain, deliberating the introduction of similar legislation.

5. Discussion

The motion to institutionalize ecocide as an international crime appears to be an escalation of previous political efforts to consolidate principles and policies warranting effective climate change mitigation in the climate negotiations arena for three decades. Global climate mitigation efforts have been anchored around common but differentiated responsibilities (for emissions) and financial capabilities to mitigate climate change, and a recurring interest in ensuring equality and justice in global climate pacts and the ensuing energy transition (Proedrou, Citation2018). Excessive harm, a central notion in the definition of ecocide, has been crystallized around the notion of loss and damage, understood as excessive harm that cannot be restored, and for adjustment to which the countries having faced this extensive loss and damage cannot pay for themselves. The criminological branch of zemiology positions harm center-stage as its name gives away (zemiology comes from the Greek word ‘zemia’ which means damage). Together with green criminology, it approaches crime not as law-breaking behaviour, but as sets of actions causing substantial harm. Such an approach is applied to state and corporate crimes, with environmental crimes falling neatly into this category. This is because in many cases, in both domestic and international environmental law, such actions remain legal in the absence of relevant regulation to render them a crime, despite the harm they cause. These legislative gaps, according to historical materialist and green criminology assumptions, are due to the state-corporate nexus and the state’s primary mission to create a conducive environment for the function of the capitalistic system. Zemiology uses the extent of violations of human rights as a yardstick to measure the extent of harm and to update, redefine and refine the criminological status of such actions (Canning & Tombs, Citation2021).

For Bettini et al. (Citation2020, p. 1), loss and damage ‘is mainly envisioned as an ‘international court of climate justice’ that identifies the culprits (emitters), quantifies harm, and compensates victims’. The idea that the Global North, in light of both its material wealth and capability to pay as well as its historical legacy, needs to pay reparations and develop a Climate Fund for the poorer and more vulnerable countries, has thus also been central to the climate debate, climaxed in the COP27 eventual agreement on a Loss and Damage Fund for vulnerable countries (Åberg, Citation2023). More recently, the idea that the poorer nations’ debt needs to be cancelled both as compensation to loss and damage as well as so that they can release more funds to adapt to, and mitigate, climate change has been developed, essentially ensuring a fiscal transfer from the Global North to the Global South (Boyd et al., Citation2021, p. 1368). How does ecocide fit into this broader climate policy picture?

On the one hand, ecocide shares with loss and damage and climate debt proposals the same ideological background premised upon notions of equality and justice. In all cases, the weakest win out, with the strongest and the ones having committed historical fallacies paying a price. On the other hand, there is substantial difference between ecocide and other climate proposals. Institutionalizing ecocide constitutes escalation since the penal code assumes central stage and perpetrators could find themselves against grave accusations. At the same time, the point is not only to punish perpetrators, but to create a tipping point beyond which it would be irrational for the state-corporate nexus to continue with business as usual, ecocidal processes. What is at stake hence is the transformation of the global capitalistic logic into alternative political and economic arrangements that strike a different equilibrium between humans and nature, and the rich and the poor, rather than simply ameliorative action to aid the poor and most vulnerable (White, Citation2018b).

Nevertheless, several important objections regarding the soundness, applicability and effectiveness of the international law of ecocide have been voiced. First, at a conceptual level, there are important trade-offs between the criminalization of ecocidal processes and the delivery of global social goods such as food, shelter and energy, especially in the context of sustainable development and the Sustainable Development Goals (Greene, Citation2018; Robinson, Citation2022). The recognition of these trade-offs and the balancing of environmental protection with the satisfaction of human needs are explicit in the definition of the IEP. This definition, proposed as the basis for an international crime of ecocide, thus eludes an ecocentric view as it calls for a cost–benefit analysis that will be the ultimate arbiter of whether the environmental damage provoked can be justified. This dilutes the rationale for an international crime of ecocide, and provides a very high bar for prosecution as defendants will be able to provide a solid line of defense simply by demonstrating the economic and social benefits emanating from the use of fossil fuels (Ambos, Citation2021; Killean and Short, Citation2023; Lindgren, Citation2023; Minkova, Citation2023).

Second, and related to the point above, in this definition knowledge borders recklessness (Killean and Short, Citation2023). This will make cases brought to the court difficult to support, as it will require proof that the alleged perpetrators were ‘aware the expected environmental damage would be clearly excessive in relation to the anticipated social and economic benefits’ (Heller, Citation2021). Contrary to other crimes, especially genocide, the notion of intent is irrelevant as perpetrators have no intent to provoke environmental harm, only to reap the benefits emanating from such activities, whose byproduct environmental harm is. Intent hence appears more in the form of disregarded risk which renders the level of threshold set for knowledge critical. On these grounds, current definitions of the crime of ecocide set the threshold of strict liability very high (Minkova, Citation2023). This chimes with the interests of governments and corporations involved in ecocidal activities, rather than provides a sharp tool in the hands of prosecutors, and hence casts doubt on the effectiveness of a future law of ecocide (Heller, Citation2021; Killean and Short, Citation2023; Minkova, Citation2023). This law, third, would be relevant only for states that have signed the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, and their corporations. Non-parties to the Statute will remain immune to prosecution even if a crime of ecocide is institutionalized. This significantly circumscribes the range of applicability of an international law of ecocide, as states such as the US, Russia, India and China and their corporations, although evidently targeted by an international law of ecocide, would not be subject to prosecution (Ambos, Citation2021; Heller, Citation2021; Lindgren, Citation2018; Robinson, Citation2022). Literature looks at the structural causes of ecocide through the state-corporate crimes lens (White, Citation2017, Citation2018a). More specifically, critical/ green criminology applies a historical materialism perspective and focuses on the neo-liberal, global political economy structures that allowthe most powerful state and corporate actors to entrench practices that contribute to ecocide. While most critical/ green criminologists focus on the synergies and co-optation between the state and corporate worlds, and on how corporate-state crimes are culprit for ecocidal climate change (White, Citation2015), scholars departing from broader political, geopolitics and nationalism studies explore more extensively state behaviour. While Falk (Citation2019) denounces great powers’ geopolitical crimes and their abuse of power for their own interest and at the cost of cosmopolitan values and weaker states, Conversi (Citation2020) advances the notion of survival cosmopolitanism as the way out for nationalism to conserve the nation-state as the organizing principle of the world and the specific nation-state entities of the world. This debate is grounded upon the notions of ecological citizenship and Earth stewardship (White, Citation2015), and links to Anthropocene geopolitics as advanced by critical geopolitics scholars (Dalby, Citation2015; Latour, Citation1999), the security-development conflict nexus scholarly debate as advanced by Homer-Dixon (Citation2010) and Le Billon (Citation2004) among others, the ecological economics stream (Daly, Citation1996) and the cosmopolitan democracy proposition (Held, Citation2009).

The legalistic discussion of harm embedded in the provision of goods directs to political conclusions; if harm is to be tolerated if it is balanced out by provision of food, shelter and energy at a basic level, but cannot be balanced out by overconsumption in affluent regions and by the ones in the upper class, then it is this redundant/luxurious and superfluous production/consumption space that will amount to ecocidal processes. Such indications again point to the neo-Marxist approaches of green criminologists, ecological and steady-state economists’ conclusions about limiting and regulating growth and redistribution and a distancing from neoliberal logics and towards alternative conceptualizations that prioritize ecological systems and services, and climate and social justice.

This approach links up to the energy transition and just transition debates, with a sustainable global energy transition being fostered to prevent the worse ills of runaway climate change, while providing for environmental safety and security as the indispensable basis for every nation and all citizens in the world, prioritizing the most exposed and vulnerable that also have contributed the least to the climate crisis and are least well equipped to respond and adjust to it (Kuzemko et al., Citation2022; Pogge, Citation2008). Again, this is not without its own set of problems. As Dunlap (Citation2018) shows, the production of renewable energy to cater for global energy needs within the entrenched neo-liberal global political economy contours in many cases also produces severe ecological harm to the extent it involves land grabbing, extensive commodification, critical loss of territorial and ecological capital, and deteriorating living conditions for indigenous populations and the most vulnerable. This defies both a broader ecological and sustainability perspective and a social justice agenda, and points to the inherent limitations of the global energy transition as currently perceived and envisaged. Related to this, the global energy transition also raises problems similar to these of a fossil fuels-based economy, as it is based on (yet another set of) natural resources that demand comprehensive extractivism, foster conducive ground for geopolitical games, pose threats to the environment and may again be premised upon extensive labour exploitation (Laird, Citation2013). This in its turn begs the question what climate policy is appropriate to combat climate change in a socially just way at global, regional, national and local levels, if the global energy transition also involves extraction, entrenches the genocide-ecocide nexus and structural violence/ scarcity against the most exposed and vulnerable populations, including indigenous ones (Lazard, Citation2021)?

This point is critical as it equips proponents of a law of ecocide with further arguments and sharpens the case for ecocide. Approaching genocide in a holistic way encompassing both a physical (‘acts of physical mass killing’) and a cultural aspect (through environmental destruction that compromises specific groups’ capacity to live) creates a critical link in the ecocide-genocide nexus (Lindgren, Citation2018, p. 526, Crook and Short Citation2014). Accordingly, evidence of harm to groups that undermines their livelihoods can be used to support cases against ecocide. The harm afflicted to First Nation people in Northern Alberta of Canada via the exploitation of tar sands and to Aboriginals in Australia through sustained land dispossession are cases in point (Lindgren, Citation2018, pp. 526–527) and resonate with the decision of the Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC in 2016 to examine environmental crimes side by side with other international crimes (Minkova Citation2023, p. 62). This brings us to the ethics debate. While inspired by ecocentrism, the current definitions and articulations of an international crime of ecocide reflect strong elements of anthropocentrism and speciesism. A cost–benefit analysis not only incorporates human needs and interests in the environmental protection calculus, but also makes people and human-centric mentalities the arbiter of what qualifies as ecocide. This understanding reflects deep-held beliefs of human superiority that allow the human species to dominate the ecosystem and other species. An international law of ecocide, however, is meaningful only if premised upon an ecocentric planetary ethics, which recognizes the right to a clean environment as a first order goal, extends it to climate refugees, all species and nature as totality (Benhabib, Citation2013, Citation2020; Donaldson & Kymlicka, Citation2011; Nussbaum, Citation2023), and respects group and indigenous rights and their established modes of co-existence with nature (Kymlicka, Citation1996; Lindgren, Citation2023). This rationale also should guide international and intersocietal relations, as treatment of nature is closely interconnected with treatment of the other. More specifically, humans dominate the earth and the most powerful dominate the weakest, rendering a world of injustices, economically, politically and environmentally (Pogge, Citation2008, pp. 155–157). The right to a clean environment, deeper empathy and regional and global integration through globally democratic mechanisms that caters for the health of nature and protect the most vulnerable are all essential to reduce environmental harm and avoid runaway climate change (Appiah, Citation2010; Cabrera, Citation2017; Nussbaum, Citation2020).

In climate policy terms, the criminalization of ecocide can augment the toolbox in the fight against climate change by providing the legal grounds for the prosecution of actors committing ecocidal acts that perpetuate climate change. Taking stock of the limitations of current definitions of ecocide, however, it is hard to anticipate the institutionalization of ecocide would mark a tipping point for the global energy transition and would trigger fast fossil phase-out. This having been said, it could indirectly help climate change policy in a handful of ways.

First, it updates the domestic penal codes of states having introduced relevant legislation, thus potentially deterring carbon criminals, reducing the environmental harm inflicted and enabling carbon criminals’ prosecution. Second, it could serve as deterrent due to the mere possibility of cases being referred to the ICC. Despite the high bar set for prosecution, an established crime of ecocide may propel perpetrators to reduce the extent of harm provoked to avoid prosecution and verdict. Third, the endorsement of a law of ecocide by the EU and its incorporation into its Environmental Directive is an interesting development, as it allows the prosecution of offenders responsible for environmental damage ‘comparable to ecocide’ (Stop Ecocide International, Citation2022). The externalization of EU rules beyond its territory, moreover, is an established instrument of EU external action, as seen in the efforts to externalize EU energy acquis and the institutionalization of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism as an extension of the EU Emissions Trading System (Lavenex, Citation2004; Szulecki et al., Citation2022). One could anticipate hence that the EU may endeavour to externalize such criminological understandings and regulations. This could follow the diplomatic pathway, by means of liaising with partners to update their criminal codes accordingly or have a harder edge through referring cases to the ICC. In both instances, repercussions for access to the lucrative EU market could serve as a critical bargaining lever. Fourth, while an international crime of ecocide may not apply to all states (and their corporations), in case an arrest warrant has been issued, the representatives of states and corporations committing ecocidal acts could be faced with prosecution when travelling to any of the 123 parties to the Rome Statute. Such risks and complexities may serve as stimuli at least for the moderation of environmental damage.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we explored whether, to what extent and in what ways climate change has been approached in scholarly literature as ecocide. By means of a scoping literature review, and the application of a historical materialist framework with specific recourse to the Capitalocene concept and world systems theory, we found that this criminological representation has gained wider currency the last decade. Literature emanates foremost from within the critical criminology, law and politics disciplines, and examines climate change as ecocide through the lens of a global capitalistic and nation-state-system that perpetuates carbon criminals, anthropocentric ethics, the growth imperative and environmental and social harm, especially at the cost of the most vulnerable populations and countries, thus reproducing inequality and injustice. Moreover, a part of the literature grapples with the ethical, procedural and substantive difficulties of the institutionalization of ecocide in international law. In disciplinary terms, this literature intersects with several approaches across the social sciences, such as Anthropocene geopolitics, ecological economics, cosmopolitan democracy and green nationalism.

The criminalization of practices that perpetuate climate change is seen progressively as the last resort solution to turn the tables in the battle against climate change. Nevertheless, our analysis shows that the advance of relevant domestic legislation and an international crime of ecocide should not be seen as a panacea, due to foreseen applicability and effectiveness hurdles. This having been said, the criminalization of ecocide would contribute to climate policy through building the momentum for more states to institutionalize a crime of ecocide domestically, the possibility to report cases to ICC and potential warrant arrests issued by the ICC against ecocide perpetrators that would constrain their freedom of movement, as well as through EU criminalization of environmental damage ‘comparable to ecocide’ and the potential externalization of EU criminal code in concert with its trade power. More broadly, there lies significant potential for increasing alignment between ecological imperatives and global social problems. Thomas Pogge’s (Citation2023, p. 2011) proposals for a Global Resources Dividend, effectively a tax on resource consumption to tackle both environmental degradation and poverty, and an Ecological Impact Fund that would enable ‘greenovators’ in the Global South to profit through the wide diffusion of their innovation and in so doing both expedite the energy transition and contribute to low-income countries’ development are significant cases in point.

The significance of this work lies in that it is, to the best of our knowledge, the first of its kind to produce robust empirical evidence as to the representation of ecocide through a criminological lens. It hence provides a springboard for further research. One such avenue could be the mapping of representations of climate change as ecocide in social media and activist groups to provide a rich evidence base regarding the dynamics of grassroots support for a crime of ecocide. Another could be the study of whether and how states instrumentalize criminological approaches to ecocide in their climate diplomacy or gear their diplomacy to fend off such pressures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Åberg, A. (2023). What enabled the agreement of a fund for loss and damage at COP27? The historic loss and damage fund. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/02/historic-loss-and-damage-fund.

- Adelman, S. (2015). Tropical forests and climate change: A critique of green governmentality. International Journal of Law in Context, 11(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552315000075

- Ambos, K. (2021, 29 June). Protecting the environment through international criminal law? EJIL:Talk! Blog of the European Journal of International Law. https://www.ejiltalk.org/protecting-the-environment-through-international-criminal-law/.

- Appiah, K. (2010). What will future generations condemn us for? Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/09/24/AR2010092404113.html?hpid=opinionsbox1.

- Bacchi, C. (2012). Introducing the ‘what’s the problem represented to be?’ approach. In A. Bletsas & C. Beasley (Eds.), Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic interventions and exchanges (pp. 21–24). University of Adelaide Press.

- Benhabib, S. (2013). Dignity in adversity: Human rights in troubled times. John Wiley & Sons.

- Benhabib, S. (2020). The end of the 1951 refugee convention? Dilemmas of sovereignty, territoriality, and human rights. Jus Cogens: A Critical Journal of Philosophy of Law and Politics, 2, 75–100.

- Bettini, G., Gioli, G., & Felli, R. (2020). Clouded skies: How digital technologies could reshape “Loss and Damage” from climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 11(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.650

- Blondeel, M., Bradshaw, M. J., Bridge, G., & Kuzemko, C. (2021). The geopolitics of energy system transformation: A review. Geography Compass, 15(7), e12580. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12580

- Boyd, E., Chaffin, B., Dorkenoo, K., Jackson, G., Harrington, L., N'Guetta, A., Johansson, E., Nordlander, L., Paolo De Rosa, S., Raju, E., Scown, M., Soo, J., & Stuart-Smith, R. (2021). Loss and damage from climate change: A new climate justice agenda. One Earth, 4(10), 1365–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.09.015

- Burke, A. (2016). Planet politics: A manifesto from the end of IR. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 44(3), 499–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829816636674

- Cabrera, L. (2017). Global government revisited: From utopian dream to political imperative. Great Transition Initiative. https://greattransition.org/publication/global-government-revisited.

- Canning, V., & Tombs, S. (2021). From social harm to zemiology: A critical introduction. Routledge.

- Chiluwa, I., & Chiluwa, I. M. (2022). Deadlier than Boko Haram: Representations of the Nigerian herder–farmer conflict in the local and foreign press. Media, War & Conflict, 15(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635220902490

- Conversi, D. (2020). The ultimate challenge: Nationalism and climate change. Nationalities Papers, 48(4), 625–636.

- Crook, M., Short, D., & South, N. (2018). Ecocide, genocide, capitalism and colonialism: Consequences for indigenous peoples and global ecosystems environments. Theoretical Criminology, 22(3), 298–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480618787176

- Crook, M., & Short, D. (2014). Marx, Lemkin and the genocide–ecocide nexus. The International Journal of Human Rights, 18(3), 298–319.

- Crutzen, P. J. (2006). The “anthropocene”. In E. Ehlers, & T. Krafft (Eds.), Earth system science (pp. 13–18). Springer.

- Dalby, S. (2015). Climate geopolitics: Securing the global economy. International Politics, 52(4), 426–444. https://doi.org/10.1057/ip.2015.3

- Daly, H. (1996). Beyond growth: The economics of sustainable development. Beacon Press.

- Donaldson, S., & Kymlicka, W. (2011). Zoopolis: A political theory of animal rights. Oxford University Press.

- Dunlap, A. (2018). The ‘solution’ is now the ‘problem’: Wind energy, colonisation and the ‘genocide-ecocide nexus’ in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. The International Journal of Human Rights, 22(4), 550–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2017.1397633

- Falk, R. (2019). Geopolitical crimes: A preliminary jurisprudential proposal. State Crime Journal, 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.13169/statecrime.8.1.0005

- Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. International Affairs, 92(5), 1107–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12708

- Ganti, T. (2014). Neoliberalism. Annual Review of Anthropology, 43(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155528

- Geels, F. (2014). Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: Introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(5), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414531627

- Geels, F. W., Sovacool, B. K., Schwanen, T., & Sorrell, S. (2017). Sociotechnical transitions for deep decarbonisation. Accelerating innovation is as important as climate policy. Science, 357(6357), 1242–1244. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao3760

- Giddens, A. (2011). The politics of climate change. Cambridge: Polity.

- Gray, M. (1995). The international crime of ecocide. California Western International Law Journal, 26(215), 215–271.

- Greene, A. (2018). The campaign to make ecocide an international crime: Quixotic quest or moral imperative. Fordham Environmental Law Review, 30(1), 1–48.

- Gunderson, R., & Fyock, C. (2022). Are fossil fuel CEOs responsible for climate change? Social structure and criminal law approaches to climate litigation. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 12(2), 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-021-00735-9

- Held, D. (2009). Restructuring global governance: Cosmopolitanism, democracy and the global order. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 37(3), 535–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829809103231

- Heller, K. (2021, 23 June). Skeptical thoughts on the proposed crime of ‘ecocide’ (that ssn’t). OpinioJuris. https://opiniojuris.org/2021/06/23/skeptical-thoughts-on-the-proposed-crime-of-ecocide-that-isnt/.

- Higgins, P., Short, D., & South, N. (2012). Protecting the planet after Rio – The need for a crime of ecocide. Criminal Justice Matters, 90(1), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09627251.2012.751212

- Higgins, P., Short, D., & South, N. (2013). Protecting the planet: A proposal for a law of ecocide. Crime, Law and Social Change, 59(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-013-9413-6

- Homer-Dixon, T. (2010). The upside of down: The end of the world as we know it, and why that may not be such a bad thing. Island Press.

- IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jansen, K., & Jongerden, J. (2021). The Capitalocene response to the Anthropocene. In H. Akram-Lodhi, K. H. Dietz, B. K. Engels, & B. McKay (Eds.), The Edward Elgar handbook of critical agrarian studies (pp. 637–647). Edward Elgar.

- Kammerer, L. (2011). Sister species: Women, animals, and social justice. University of Illinois Press.

- Killean, R., & Short, D. (2023, 18 October). A critical review of the law of ecocide. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4605681

- Kuyper, J., Schroeder, H., & Linnér, B. O. (2018). The evolution of the UNFCCC. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43(1), 343–368. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-030119

- Kuzemko, C., Goldthau, A., & Keating, M. (2015). The global energy challenge: Environment, development and security. Palgrave.

- Kuzemko, C., Blondeel, M., Dupont, C., & Brisbois, M. C. (2022). Russia’s war on Ukraine, European energy policy responses & implications for sustainable transformations. Energy Research & Social Science, 93, 102842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102842

- Kymlicka, W. (1996). Multicultural citizenship: A liberal theory of minority rights. Oxford University Press. 75-106

- Laird, F. (2013). Against transitions? Uncovering conflicts in changing energy systems. Science as Culture, 22(2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2013.786992

- Latour, B. (1999). Politics of nature. Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. (2007). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford University Press.

- Lavenex, S. (2004). EU external governance in ‘wider Europe’. Journal of European Public Policy, 11(4), 680–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176042000248098

- Lazard, O. (2021). The need for an EU ecological diplomacy. In O. Lazard, & R. Youngs (Eds.), The EU and climate security: Toward ecological diplomacy (pp. 13–24). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Le Billon, P. (2004). The geopolitical economy of ‘resource wars’. Geopolitics, 9(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040412331307812

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’ Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 20(5), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lindgren, T. (2018). Ecocide, genocide and the disregard of alternative life-systems. The International Journal of Human Rights, 22(4), 525–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2017.1397631

- Lindgren, T. (2023). Grounding ecocide, humanity, and international law. In V. Chapaux, F. Mégret, & U. Natarajan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of international Law and anthropocentrism (pp. 307–322). Routledge.

- Lynch, M. J., Stretesky, P. B., & Long, M. A. (2018). Green criminology and native peoples: The treadmill of production and the killing of indigenous environmental activists. Theoretical Criminology, 22(3), 318–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480618790982

- Mehta, S., & Merz, P. (2015). Ecocide – A new crime against peace? Environmental Law Review, 17(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461452914564730

- Minkova, L. (2023). The fifth international crime: Reflections on the definition of “Ecocide”. Journal of Genocide Research, 25(1), 62–83.

- Moore, J. (2015). Capitalism in the Web of life: Ecology and the accumulation of capital. Verso Books.

- Mwanza, R. (2018). Enhancing accountability for environmental damage under international law: Ecocide as a legal fulfilment of ecological integrity. Melbourne Journal of International Law, 19(2), 586–613.

- Nussbaum, M. (2020). The capabilities approach and the history of philosophy. In I. E. Chiappero-Martinetti, S. Osmani, & M. Qizilbash (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the capability approach (pp. 13–39). Cambridge University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2023). Justice for animals: Our collective responsibility. Simon and Schuster.

- Pogge, T. (2008). Aligned: Global justice and ecology. In L. Westra, K. Bosselmann, & R. Westra (Eds.), Reconciling human existence with ecological integrity: Science, ethics, economics and Law (pp. 147–158). Earthscan.

- Pogge, T. (2023). An ecological impact fund. Green and Low-Carbon Economy, 1(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewGLCE3202583

- Proedrou, F. (2018). Energy policy and security under climate change. Palgrave.

- Proedrou, F. (2022). How energy security and geopolitics can upscale the Greek energy transition: A strategic framing approach. The International Spectator, 57(2), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2021.2014102

- The Promise Institute for Human Rights, UCLA School of Law. (2021). Proposed definition of ecocide. 9 April 2021. https://ecocidelaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Proposed-Definition-of-Ecocide-Promise-Group-April-9-2021-final.pdf.

- Rajamani, L., & Peel, J. (2021). Reflections on a decade of change in international environmental law. Cambridge International Law Journal, 10(1), 6–31. https://doi.org/10.4337/cilj.2021.01.01

- Robinson, D. (2022). Ecocide-puzzles and possibilities. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 20(2), 313–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqac021

- Snaphaan, T., & Hardyns, W. (2021). Environmental criminology in the big data era. European Journal of Criminology, 18(5), 713–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370819877753

- Stop Ecocide International. (2021). Legal definition of ecocide. https://www.stopecocide.earth/legal-definition.

- Stop Ecocide International. (2022). Agreement reached! EU to criminalise severe environmental harms “comparable to ecocide”. 17 November. https://www.stopecocide.earth/breaking-news-2023/agreement-reached-eu-to-criminalise-severe-environmental-harms-comparable-to-ecocide.

- Szulecki, K., Overland, I., & Smith, I. D. (2022). The European Union’s CBAM as a de facto Climate Club: The governance challenges. Frontiers in Climate, 4, 942583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.942583

- Tavoa, C. (2021). Critical evaluation on ecocide as to whether or not it should be a serious crime under the Rome statute of the International Criminal Court. Journal of South Pacific Law, 22, 164–180.

- Van de Graaf, T., & Sovacool, B. (2020). Global energy politics. Polity Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (1995). After liberalism? The New Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (2020). World-systems analysis: An introduction. Duke University Press.

- Walters, R. (2022). Ecocide, climate criminals and the politics of bushfires. The British Journal of Criminology, 63(2), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azac018

- White, R. (2015). Climate change, ecocide and the crimes of the powerful. In G. Barak (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of the crimes of the powerful. (pp. 231–242). Routledge.

- White, R. (2017). Criminological perspectives on climate change, violence and ecocide. Current Climate Change Reports, 3(4), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-017-0075-9

- White, R. (2018a). Ecocide and the carbon crimes of the powerful. University of Tasmania Law Review, 37(2), 95–115.

- White, R. (2018b). Climate change criminology. Bristol University Press.