ABSTRACT

Without deliberate and proactive attempts to redirect and regulate flows of public and private finance, achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement will remain elusive. Yet, despite extensive engagement with different dimensions of climate finance by academics and policy practitioners alike, the financial system continues to be fundamentally misaligned with climate goals by locking in high-carbon development pathways while inadequately resourcing climate adaptation. Moving beyond dominant discourses about mobilising and de-risking private finance, this paper seeks to identify potential alternative interventions and leverage points to align the mobilization and redirection of finance with a more transformative approach to climate finance that targets the sources of climate change in a globally unequal fossil-fuel economy. This implies making greater use of the many policy tools that governments have at their disposal with regards to taxation and regulation, often deployed to fund the welfare state or for macroeconomic management, but which constitute powerful levers for mobilising and redirecting climate finance that have been excluded thus far from conventional definitions of climate finance used by the international community. Consciously moving beyond a narrower focus on financing decarbonization, this implies greater attention to redirecting, hypothecating and regulating the whole ecosystem of global finance so that the goals and organization of the global financial system and global climate action are better aligned.

Key policy insights

Alongside mobilising new finance, there is a need to consider deliberate and proactive attempts to redirect, redistribute and regulate flows of public and private finance to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The article identifies a finance gap, a production gap and a governance gap in dominant approaches to financing climate action.

This article draws attention to the need to address the neglected issues of debt, taxation and regulation in order to lay the basis a more transformative approach to climate finance.

It proposes governance reforms at the national and international level to address these gaps including reform of multilateral development banks and of national financial institutions such as central banks.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Without deliberate and proactive attempts to redirect and regulate flows of public and private finance, achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement will remain elusive. Yet, despite extensive engagement with different dimensions of climate finance by academics and policy practitioners alike, the financial system continues to be fundamentally misaligned with climate goals by locking in high-carbon development pathways while inadequately resourcing climate adaptation. Moving beyond dominant discourses about mobilising and de-risking private finance, this paper seeks to identify potential alternative interventions and leverage points to align the mobilization and redirection of finance with a more transformative approach to climate finance that targets the sources of climate change in a globally unequal fossil-fuel economy. This implies making greater use of the many policy tools that governments have at their disposal with regards to taxation and regulation, often deployed to fund the welfare state or for macroeconomic management, but which constitute powerful levers for mobilising and redirecting climate finance that have been excluded thus far from conventional definitions of climate finance used by the international community. Consciously moving beyond a narrower focus on financing decarbonization, this implies greater attention to redirecting, hypothecating and regulating the whole ecosystem of global finance so that the goals and organization of the global financial system and global climate action are better aligned.

Though often framed as primarily a question of mobilising new public and private finance, this article centres questions of regulation (of the primary financial driver of climate change in the form of fossil-fuel finance) and redistribution (of such finance) towards those in need of access to renewable energy which displaces fossil fuels and in the frontline of the impacts of climate change. I argue that such a move helps to address a fundamental and pressing need to agree on a new global compact between richer and poorer countries which explicitly links responses to the existential threat of climate change with efforts to confront the poverty experienced by the majority of the world's citizens. Without attention to the latter, efforts to strengthen ambition and accelerate transitions away from the fossil-fuel economy will inevitably be resisted. In particular, it draws attention to the need to address neglected leverage points such as debt, taxation and regulation as a means to both redirect and redistribute finance as part of a more transformative approach to climate finance. An approach which focuses only on using public funds to lever and de-risk private ones is only addressing half the problem: the question of mobilising finance rather than regulating and redistributing it which is equally pressing to divert finance away from fossil fuels and address the justice issues central to responses to climate change.

At present, the global financial system is deeply implicated in the production and financing of the climate crisis which exacerbates existing inequalities and deepens the poverty of the poorest (UNEP, Citation2023). But substantially reformed and better regulated, it could also provide a series of leverage points for addressing that crisis.

To contribute to discussions about how best to address this problem, after briefly introducing the methodology and approach, the paper first identifies three key gaps in the current financial architecture which means it is no longer fit for purpose in responding to the threat of climate change. Secondly, it proposes an alternative set of leverage points for realigning the global financial system as part of a more transformative approach to climate finance.

1.1. Methodology and approach

First, while there is no multilaterally agreed definition (SCF, Citation2022), climate finance can and does refer to a very broad range of types of finance (Bryant & Webber, Citation2024). The UN, for example, define it as ‘any local, national, or transnational financing – drawn from public, private and alternative sources of financing – that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change’ (Berman & Fong, Citation2023). This finance comes from many different sources and is provided on different terms (market-based versus concessional, for example) which I clarify in relation to each of the gaps and leverage points explored below. This understanding of climate finance goes beyond a narrower focus on North–South flows of finance in support of the goals of the UNFCCC.

The gaps explored in section 2 are identified as follows. Regarding the first gap, whereas the ‘finance gap’ is conventionally discussed as a question of mobilising private finance, here drawing on a broader range of academic, policy and ‘grey’ literature, I show that this gap has been understood too narrowly and neglects questions of distribution in particular. The second (production) gap is identified based on the Production Gap Report (SEI et al, Citation2023) which underscores that the goals of the Paris Agreement cannot be achieved amid the continued financing of fossil fuels which make up 75% of greenhouse gas emissions and 90% of carbon dioxide emissions. The third (governance) gap is identified by mapping a gap in the landscape of climate finance institutions and initiatives where there is an imbalance between voluntary standards and guidelines and limited state regulation of the climate impacts of finance on the one hand, and more stringent, legally binding and enforceable regulation of finance for climate objectives.

Meanwhile, the leverage points to address these gaps are the following: Redirect and redistribute flows from all three gaps since public and private finance needs to be actively withdrawn from fossil fuels (as the production gap shows) and the governance gap highlights the need for the improved governance of both public and private governance. Hypothecation is critical to deterring investment in carbon-intensive sectors and assets and directing finance to sectors and regions where it is most needed. This is a critical means for building support of distributive measures. Progressive taxation speaks to the need to tap into untaxed revenues to mobilize the scale of finance required to tackle the climate crisis. Re-regulation meanwhile is a cross-cutting leverage point and flows from the need for deeper and more comprehensive governance of the diverse ecosystem of climate finance.

I discuss existing literature and its limitations in relation to each of the gaps and leverage points discussed below drawing on the many useful reports and analyses by key bodies such as the UNEP, IEA, Climate Policy Initiative and UNCTAD, grey literature from civil society organizations such as Reclaim Finance and Oil Change International as well as analysis by scholars critical of the notion of de-risking (such as Gabor, Citation2021) and how climate finance institutions currently operate (Bracking & Leffel, Citation2021; Bryant & Webber, Citation2024). The emphasis on ‘leverage points’ draws on the scholarship of Meadows (Citation1999) which includes changes to the ‘rules of the system’ among their ‘deep leverage points’ and the emphasis Abson et al. (Citation2017, p. 30) place on ‘less obvious but potentially far more powerful areas of intervention’ in contrast to dominant approaches which ‘target highly tangible, but essentially weak, leverage points’.

These leverage points were identified on the basis of their ability to (a) scale shifts in finance by widening and deepening the forms of finance targeted and the ways in which they are mobilized, (b) address the justice issues which many existing approaches fail to address (and which limits their support in many parts of the global South in particular) and (c) plug governance gaps to steer the finance to the sectors, regions and people where it is most needed. This is critical to achieving the more ‘transformative systemic change’ now required to address the climate crisis (IPCC, Citation2018). This contributes, I argue, to a better appreciation of how the financial system is implicated in reproducing the climate crisis, but by using other – and often neglected leverage points – can be repurposed as part of a more transformative approach to climate finance.

2. Mind the gaps

This section explores three crucial gaps in the relationship between the financial system and climate action drawing on existing academic and grey literature. The first is a widely acknowledged finance gap, but I suggest the debate needs to go beyond mobilising new sources of finance to address questions of distribution more effectively. The second and third are neglected gaps when it comes to discussions of climate finance, yet critical to its effectiveness in divesting and redistributing funds.

2.1. The finance gap

2.1.1. Scale

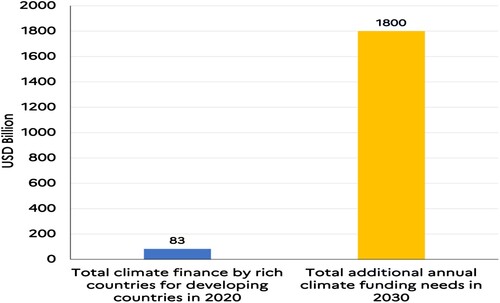

Firstly, it is widely accepted that there is a ‘finance gap’ between the level of finance that is necessary to meet the scale of the climate crisis and what governments and global institutions around the world have currently committed to thus far. Central to this is the failure of richer countries to deliver the sums of climate finance ($100 bn a year by 2020) agreed to at the Copenhagen summit to be channelled through the Green Climate Fund (GCF). Thus far, the GCF has a total pipeline of less than half this sum (51.8 bn) (GCF, Citation2023) (). The Climate Policy Initiative finds that global climate finance needs will amount to $6300 billion worldwide in 2030 (CPI, Citation2023), and should have reached about $4200bn in 2021. Yet in 2021, total climate finance actually amounted to $850bn: a significant sum, but nowhere near what is required. CPI calculate in an average scenario that annual climate finance needed through 2030 will increase to $9 trillion and thereafter rise to over $10 trillion each year from 2031 to 2050. This implies that climate finance must increase by at least five-fold annually to avoid the worst impacts of climate change (2023, 3). Though these figures represent vast sums, they have to be viewed alongside the anticipated costs of climate impacts in the absence of increased efforts to reduce emissions and redirect the finance which enables them (UNEP, Citation2023). Without such interventions, warming will exceed 3°C, leading to macroeconomic losses of at least 18% of GDP by 2050 and 20% by 2100 (NGFS, Citation2022).

Figure 1. The finance gap (between funds committed and funds needed). Source: Chancel et al. (Citation2023).

2.1.2. Distributional gaps

Alongside this gap between what is required and what has been delivered, there is also an imbalance between finance for mitigation and adaptation. Finance for climate mitigation ($586 billion in 2020) dominates when compared with that for adaptation ($49 billion in 2020) (CPI, Citation2023), notwithstanding the fact the latter is much harder to calculate. UNEP estimates that US$140 300 billion will be required for adaptation in developing countries alone (UNEP, Citation2022) or USD 212 billion per year by 2030 (CPI, Citation2023). Worse still, this does not take into account the estimated costs of loss and damage, which by 2030 in developing countries could add another US$290 billion – 580 billion to the bill (Markandya & González-Eguino, Citation2019; UNEP, Citation2023).

This imbalance is compounded by a further gap: an uneven distribution of finance for mitigation between regions where increased investments in clean energy finance have largely been secured by China, the US, Europe, Brazil, Japan, and India who together attracted 90% of this investment (CPI, Citation2023). Despite ongoing commitments to use carbon markets to raise finance for mitigation in lower and middle-income countries (LMICs), reflected in the creation of a new Sustainable Development Mechanism (SDM) under the Paris Agreement, carbon market finance is not reaching the poorest regions and groups nor, thus far at least, of a scale to be transformative. Between 2000 and 2020, the ten countries most affected by climate change received less than 2% of total climate finance (CPI, Citation2023).

Given Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) amounted to about 1% of the value of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows in 2021 according to the OECD, leaving a significant ‘public finance gap’, it is easy to understand why there is so much attention to mobilising and redirecting private finance. One of the key roles envisaged by donors for governments is to create enabling environments that incentivize and ‘crowd-in’ private investments (Carter, Citation2020), while often neglecting the simultaneous need to ‘crowd out’ finance for fossil fuels. The IEA estimates that 85 per cent of the required investments in non-fossil-fuel-based energy will need to come from private sources (IEA 2019). Public finance contributed about 50% to total climate finance in 2021, the rest being private sector finance. But a challenge for the de-risking narrative is that public sector finance rose faster than the private sector and contributed a greater share to closing the climate finance gap over the past decade. The UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance (SCF) reports while there is a ‘gradual rising trend’ in public finance, private finance mobilized by public finance and attributed to developed countries dropped by 2 per cent in 2019 compared to 2018 and by a further 9 per cent in 2020 relative to 2019 (SCF, Citation2022). Hence, despite high expectations of its potential role, private finance has performed poorly to date in delivering climate finance. This is part of a longer history of exaggerated expectations about the ‘leverage ratios’ of private capital (UNCTAD, Citation2022).

2.2. The production gap

The second major gap is a ‘production gap’ between planned fossil-fuel production funded by public and private finance and the levels of fossil-fuel extraction compatible with the Paris Agreement. 80–90 per cent of coal reserves worldwide will need to remain in the ground, if climate targets are to be reached, approximately 35 per cent of oil reserves and 50 per cent of gas reserves (Welsby et al., Citation2021). Yet, according to the Production Gap report (SEI et al, Citation2023), governments are planning to produce 110 per cent more fossil fuels by 2030 than would be consistent with limiting warming to 2 C let alone 1.5C. Even assuming all countries fulfil their pledges, it would account for only about a third of the needed emission reductions to get to 2°C, let alone the Paris Agreement's aspiration of keeping warming below 1.5 degrees compared with pre-industrial levels (UNEP, Citation2023). Both the production and emissions gaps highlight the clear need to leave the majority of remaining fossil fuels in the ground and restrict financial support to them.

Currently, therefore, financial flows are directly exacerbating the problem of climate change through financing fossil fuels which only adds to the costs of adaptation. For example, the total fossil-fuel subsidies in 51 major countries alone were 40% higher than the total global investment in climate finance between 2011 and 2020 (CPI, Citation2023). This is partly a failure to mainstream climate objectives in financial institutions and the non-climate financial decision-making of export finance bodies such as Export Credit Agencies and the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Moreover, despite the negotiation of the Paris Agreement in 2015, multilateral development bank finance for fossil fuels remains high with one estimate that the World Bank supplied about $3.7bn in trade finance in 2022 for oil and gas development (Harvey, Citation2023). The World Bank Group provided the most direct finance for fossil fuels of any MDB at $1.2 billion a year on average (OCI & FoE, Citation2024). Since the Paris Agreement, about $4.6 trillion of bonds and loans have been committed to businesses focused on fossil fuels, roughly double the $2.3 trillion arranged for renewable projects and other low-carbon solutions (Quinson, Citation2023).

2.3. The governance gap

Thirdly, there is a ‘governance gap’ – an imbalance between regulation for rather than regulation of the financial sector. This refers to the imbalance between law and regulation which seeks to protect financial actors, access to markets and the rights of investors through bilateral trade and investment agreements such as the Energy Charter Treaty (Tienhaara et al., Citation2022) on the one hand, and measures which articulate investor responsibilities and duties to protect the environment on the other (such as OECD guidelines on MNEs and the Equator Principles or the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ, Citation2022)) which remain weak and under-enforced and do not address climate impacts (Newell, Citation2011).

This implies a strong role for governance: to leverage the $48.75 trillion over the next 15 years that the IPCC estimates will be necessary to limit global warming to 1.5 ◦C. A 1.5° C-consistent pathway requires a transformation in both the volume of climate investments and the direction of finance that will not be possible from voluntary action alone.

3. Leverage points for global finance for climate-compatible development

In order to help address some of the gaps identified in Section 2, in the following section, an alternative set of leverage points is identified to reframe the challenge of climate finance as not only one of generating new finance as much as redirecting, hypothecating and better regulating existing flows of finance in the global economy, while also addressing neglected issues such as debt and taxation as a means of not only generating additional revenue but also providing a fairer global settlement within and between countries that will be a prerequisite for climate finance to play a more transformative role.

3.1. Divestment and redirection

As well as mobilising new sources of funds, the first critical leverage point is divestment and redirection of existing finance to address both the production and finance gaps described above to restrict the financing of fossil fuels as the principal cause of climate change and to redirect this finance to efforts to address it. This is true of the whole spectrum of both public and private finance. Debates about financing climate action often start (and frequently end) with a discussion about the staggering volumes of capital that need to be mobilized to decarbonize the global economy and effectively address the climate crisis. This ‘deficit model’ and the promise of new infrastructures, financial products, services and technologies that will serve as key outlets for finance, often obscure the equally important need to divest, redirect and withdraw capital from climate change-inducing fossil-fuel infrastructures. This challenges dominant narratives about the nature and source of the gap by showing how it is not just finance that has to fill it, but better governance aimed at limiting financial support to activities driving the climate crisis and redirecting funds towards those lacking access to low-carbon alternatives and in need of support for adaptation to the effects of climate change. At root, whether or not the world transitions away from fossil fuels in time to avert catastrophic climate change will likely not be a function of whether we have enough money available. It will have more to do with how much capital continues to be directed to investments that drive us past any chance of achieving a 1.5°C trajectory.

Un-funding key projects and infrastructures driving climate change presents a critical first step, guided by the principle of ‘do no more harm’. Allowing finance to continue to flow into projects and infrastructures that are incompatible with climate action is to push their accomplishment further into the future while increasing the costs of adaptation. To take just one example, the world currently spends US$11 million a minute according to the IMF on fossil-fuel subsidies that are driving climate chaos (IMF, Citation2021). As well as financing the generation of more greenhouse gases, they also reduce the effectiveness of other policy measures since, for example, carbon pricing cannot establish clear market signals as long as fossil-fuel subsidies create a countervailing negative price (Green, Citation2021). While recognising there is a complex political economy of withdrawing them, where priority would need to be given to phasing out producer subsidies in wealthier countries first, these could be redirected into a global transition fund to finance renewable energy pathways in poorer parts of the world as part of a multilateral phase down of fossil-fuel production (Newell & Simms, Citation2020). A large percentage of the US$1.4 trillion that G20 countries allocated to support fossil-fuel use in 2022 could be redirected towards such a fund (IISD, Citation2023). There have already been a number of successes in withdrawing finance from fossil, including commitments from the European Investment Bank (EIB) to discontinue financial support to fossil fuels and there are current proposals with the OECD to coordinate restrictions on the use of export credit for fossil fuels. There has also been a raft of initiatives that seek to redirect both public and private finance away from fossil fuels and into low-carbon energy sources. These include the Export Finance for the Future (E3F) to align public finance with climate goalsFootnote1 and the Glasgow Statement (or Clean Energy Transition Partnership) agreed at COP26 which commits signatories to shift government-backed international finance away from fossil fuels, signed by 39 governments and institutions which, if they deliver, will mean 55% of this fossil-fuel support will end by the end of 2024 (OCI & FoE, Citation2024).

With regard to the private sector, fossil-fuel divestment movements have played a critical role in pushing institutional investors: universities, pension funds and others to divest from fossil fuels (Bergman, Citation2018). By October 2021, a total of 1,485 institutions representing $39.2 trillion in assets worldwide had begun or committed to divestment from fossil fuels.Footnote2 Divestment could be an important lever here since current high-carbon investment portfolios would finance warming of 3.7–3.8°C,Footnote3 a catastrophically high level of global heating. Such activism will be vital to supporting wider moves towards to divestment given the reluctance of many financial institutions part of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) to countenance stricter requirements to divest (Reclaim finance, Citation2023). What is proposed here is more ambitious, however, than voluntary or social movement-led divestment campaigns. In the public arena, it would be directed by policy from states, regional and multilateral institutions building on the examples above, but privately by enhanced CSR and ESG standards and pressure from concerned investors about stranded assets and reputational damage, reinforced by forms of civic pressure from shareholder activism and other forms of ‘civil regulation’ (Newell, Citation2021).

3.2. Hypothecation

A second leverage point is the hypothecation of finance for specific climate and development goals. Hypothecation in this context refers to the deliberate linking of redistributive measures to redirect or tax polluting activities on a polluter pays basis towards those most in need of support to adopt mitigation measures or protect themselves from the effects of climate change. In so doing, it helps to build political support for such measures by building a base of beneficiaries likely to support such an intervention. Measures guided by this principle could take a number of forms including taxes on the 1% of wealthiest citizens for climate adaptation; carbon taxes on aviation, shipping and other high emitting sectors for adaptation; debt relief linked to climate action (discussed below) and the redirection of fossil-fuel subsidies to a global transition fund as noted above. Indeed, there are precedents for proposals for taxation on polluting activities such as aviation and shipping or the generation of revenues from carbon border adjustment measures. For example, in 2008, the Maldives, on behalf of LDCs, submitted a proposal to establish an International Air Passenger Adaptation Levy. The UN Economic Commission for Africa then took up the idea of an air travel adaptation levy in 2011 proposing that levies be collected via the UNFCCC Secretariat and transferred to the Adaptation Fund which would allocate the funds to developing country regions identified as most vulnerable and at risk from the impacts of climate change (ACPC, Citation2013).

Experience of fossil-fuel subsidy reform to date also suggests it is critical to hypothecate funds: to make it clear how they will be used to benefit poorer groups (McCulloch, Citation2023; Skovgaard & van Asselt, Citation2018), in this case either through access to affordable renewable energy or climate adaptation measures. Coordinated regional and multilateral efforts at subsidy reform could scale up such efforts. Launched in 2019 at the initiative of New Zealand, the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS) aims at using trade rules to phase out fossil-fuel subsidies among the parties to the agreement. It complements an earlier initiative launched by New Zealand to establish an informal ‘Friends’ group of non-G20 countries to encourage G20 and APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) leaders to act on their commitments to phase out inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies as soon as possible (Chancel et al., Citation2023).

Through creative issue-linkage, debt relief could also be linked to efforts to finance climate action while reducing poverty. To be effective, this would need to be combined with broader debt relief interventions and Special Environmental Drawing Rights (UNCTAD, Citation2019). But large numbers of debt distressed countries have fossil-fuel reserves which they will want to exploit without economic support. Of 76 lower-income countries, about half have proven fossil-fuel reserves and are planning to, or already are, expanding fossil-fuel extraction (New Climate Institute, Citation2021). Indeed, there is a strong relationship between higher sovereign debt burdens and a reliance on fossil-fuel exports to generate government incomes.Footnote4 Moreover, when debt levels are high, countries are no longer able to borrow from international markets to finance alternatives to fossil fuels (Woolfenden, Citation2023). Volz et al. (Citation2020) propose the ‘Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery Initiative’ on a global scale to boost the resilience of economies and support a just transition to a low-carbon economy. ‘Debt for climate’ swaps would provide debt relief to nations that choose to forgo extraction and keep reserves in the ground, learning from the experience the Yasuni initiative in Ecuador by developing a more multilateral funding mechanism that might induce producing states to leave large swathes of fossil-fuel reserves in the ground (Muttitt & Kartha, Citation2020).

Any such moves in this direction must necessarily form just one element of broader economic support to poorer countries. But tying debt relief to keeping reserves in the ground could represent a climate and development win and so-called ‘climate bailouts’ are gaining support from activists and advocates around the world as a potentially powerful lever for change.Footnote5

3.3. Progressive taxation

A third leverage point is the closing of tax loopholes and tax havens. Taxation in this regard is not just about taxing highly polluting behaviour, but also indirectly the assets that the richest segment of society holds in fossil fuels. The world's top 1% of carbon emitters are responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire bottom half of the population (Chancel et al., Citation2023) and so interventions to mobilize finance need to recognize these stark inequalities and uneven responsibility. Tax reform would not only repatriate billions of dollars in missing capital from tax havens and loopholes, but also help to create the political conditions for meaningful action on decarbonization (Green, Citation2021). Tax havens are estimated to shelter $12 or $13 trillion in private deposits, collectively costing governments between $500 billion and $600 billion a year in lost corporate tax revenue, depending on the estimate (Cobham & Janský, Citation2018), of which low-income economies account for some $200 billion (IMF, Citation2019). Moreover, they are being used by the ‘carbon majors’ to boost their profits and reinvest in fossil fuels by shifting their profits to tax havens to avoid hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes using affiliate insurance and financial organizations in tax havens where tax rates are low to non-existent (Bergin & Bousso, Citation2020).

Proposals to address these funding gaps include common global measures for country-by-country reporting and collecting tax and global asset registries to restrict scope for evasion and avoidance (ICRICT, Citation2019) and could lever significant revenue when combined with ‘Robin Hood’ taxes on speculative finance and taxation on pollution.

A range of progressive tax measures could be used to increase funds for action on climate mitigation and adaptation. Chancel et al. (Citation2023) propose a ‘1.5 percent-for-1.5 degree’ wealth tax: a global wealth tax on individuals owning more than 100 million dollars net of debt. This tax would apply to the 65,000 richest adult individuals, a group representing just a little more than 0.001% of the global adult population that could raise about US$300 billion every year. As Green suggests, 'correcting tax evasion is a necessary but not sufficient condition for ambitious climate policy’ (2021: 375).

The challenge in using such measures to address some of the gaps in the climate finance regime is that many countries still lack progressive capital income taxes, top inheritance taxes or progressive wealth taxes. Current discussions on the apportionment of multinationals profits under the auspices of the OECD could lead to additional government revenues of the order of US$110-160 billion for both high income and low-income countries under a 15% global minimum corporate tax rate whereby multinational enterprises pay a fair share of tax wherever they operate.Footnote6 Some developing countries and tax justice activists have called for a UN treaty instead. A call to develop a UN Tax Convention was first put forward by the Africa Group at the United Nations in 2019, a call that has been supported by the South Centre and many others since.Footnote7 Recognising the importance of tapping into this vast private wealth through tax to help finance climate and development objectives, UNCTAD noted in its 2019 report on Financing a Global Green New Deal:

Global corporations are sitting on an estimated $2 trillion cash pile, while high net worth individuals have access to more than $60 trillion in assets. The OECD estimates that institutional investors in member countries hold global assets of US$92.6 trillion and … estimates for the assets held by Brazilian pension funds exceed $220 billion and some $350 billion for combined African pension funds. Redirecting a relatively small portion of these resources to meet the SDGs should … be able to solve the financing challenge facing the 2030 Agenda. (UNCTAD, Citation2019: IV)

3.4. Re-regulation

Many of these leverage points rest, in turn, on a fourth: the strengthened governance of global finance at the global and national level. Globally, this includes rules on MDB lending and aid to the fossil-fuel sector and regulations and revisions in multilateral, regional and bilateral investment treaties to ensure they are supportive of (rather than undermine) global climate policy, helping to close the production and governance gaps identified in Section 2. The regulation of finance needs to address the un-governance of finance: closing the governance blind spots noted above where global financial flows in key sectors such as energy are often not subject to social and environmental criteria or safeguards (Newell, Citation2011). This includes public and private finance distributed by the Multilateral Development Banks which, as we saw above, continue to disperse large amounts of finance to fossil-fuel production driving the climate crisis. Given the growing financial power of state development banks, whose loans often dwarf those of MDBs, there is also a clear need to coordinate climate safeguards in lending practices between banks. For example, the stock of outstanding loans made by the China Development Bank was $1,635 billion in 2017, much larger than the total loans made by the World Bank (UNCTAD, Citation2019). There is significant scope for improved cooperation and coordination between the many financial institutions active in this space as well as new pooled funding arrangements (what some have labelled a Marshall Plan for Climate (Kharas, Citation2022)) to improve the scale and impact of financing as well as its accessibility to the poorest countries.

Nationally, moves towards strengthened financial governance would cover the public and private regulation of finance: from standards and rules on disclosure, evaluation of climate change impacts and the screening of finance from export credit agencies to minimize negative climate impacts, for example. A positive precedent in this regard is the French Energy Transition Law of 2015 which mandates listed companies to disclose how climate risks are managed, providing a legislative environment that has accelerated the transition of French banks away from fossil fuels. Climate risks need to be addressed by both central banks and the Financial Stability Board. For example, the Bank of England's Financial Policy Committee monitors climate risks and in 2015, the G20 finance ministers requested the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to examine the issue of financial stability in the face of climate change.

The role of central banks warrants further attention in this regard (Campiglio et al., Citation2018; Langley & Morris, Citation2022). For them to realize a positive role in financing climate action; however, they need to move beyond a position of alleged ‘market neutrality’ which means asset purchases follow the investment preferences of the capital markets, reinforcing the power of industry incumbents including fossil-fuel majors. Treasury bonds could support public investment in low-carbon energy, whereas at the moment the additional fiscal space they create has often been used to lock-in high-carbon pathways (Bailey, Citation2020). Hence, more ambitious interventions would centre on dealing with medium and longer-term risks rather than short-term crisis abatement. These would focus on monetary policies and regulatory frameworks that would help realign finance with decarbonization targets including the incorporation of liability and financial risks into the lending practices of commercial banks to regulate more effectively those organizations commercial banks can and cannot lend to and a reduction of central bank holdings of risky assets (Boneva et al., Citation2022; Schoenmaker, Citation2021).

Core incentive structures also need to be changed through shifts in company law to fill some of the governance and production gaps identified in Section 2 around (limited) liability, shareholder rewards for risky investments and disclosure requirements. For example, 90% of companies directly reward executives for production or reserve increases in some shape or form (Carbon Tracker, Citation2020). Tougher requirements around disclosure would help to assess the carbon emissions associated with assets at the point of listing in initial public offerings prospectuses and their associated risks. Carbon Tracker (Citation2022) reveal that 98% of 134 companies, collectively responsible for up to 80% of emissions, did not provide sufficient evidence that they had considered the impact of climate matters when preparing their 2021 financial statements. This lack of disclosure leaves investors in the dark about overstated assets and understated liabilities, and means markets are unable to allocate capital appropriately, undermining efforts to decarbonize the global economy. Positive precedents include moves by the UK government to make it mandatory for Britain's largest businesses to disclose their climate-related risks and opportunities, following the recommendations of its Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).Footnote8

Targeting these key neglected sites of finance could yield big wins in terms of climate action. Recent analysis found nearly half of the potential emissions from the world's largest energy firms are controlled by just ten shareholders, including BlackRock, Vanguard, and Fidelity Investments. Such a high concentration of ownership over future production – and, by extension, future emissions – means that targeted interventions at just a handful of private financial actors could have a substantial impact (Dordi et al., Citation2022). Governance here then refers not just to national-level regulation or global mechanisms of coordination and steering of finance to where it is most needed, but also to private and informal ‘civil regulation’ by civil society actors of the private sector (Newell, Citation2001).

4. Conclusion

The conversation about climate finance takes place against a background of growing calls for a ‘new Bretton woods’ and moves to position the World Bank as a global climate bank, ‘the perfect climate change lender’ (The Economist, Citation2023, p. 78) that will somehow ‘turn billions into trillions’ by ‘unlocking private finance’: a goal that, as we have seen, has evaded the most endeavours to date. Based on the preceding analysis, however, absent a fundamental shift in how funding priorities are set and the ways in which finance is governed, such a move would be unlikely to address many of the issues raised here regarding over-optimism about the role of private finance, its lack of regulation and continued financing of many of the drivers of the climate crisis. The global financial system is a complex ecosystem of actors and institutions with often competing mandates, risk thresholds and modes of financing; all of which need to be targeted, but in different ways using some of the leverage and entry points described here. Hence the leverage points proposed here offer extra, and in some cases alternative, ways to raise and redirect finance, but they clearly do not do away with the need for other complementary approaches given the complexity and scale of the challenge.

Some of the leverage points proposed here may seem utopian. Yet the SDGs provide potential levers to redirect finance towards the imperative of sustainability and climate action. For example, goals 17.1 on improving domestic revenue collection and taxation and 17.3 on mobilising financial resources underscore the need to raise, redirect and govern finance more effectively. But there also needs to be a power shift in which controls finance and the purposes for which it is deployed for the goals to realize this potential, combined with a clearer vision of the appropriate relationship between finance and the goals of climate action. Indeed the pandemic has shown that activist and interventionist states and institutions are capable of mobilising vast amounts of capital and deploying it to meet the needs of vulnerable groups for which there was strong public support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., Von Wehren, H., Abernethy, P., Ives, C. D., Jager, N. W., & Lang, D. J. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio, 46, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

- ACPC (African Climate Policy Centre). (2013). “Financing Adaptation through a Levy on International Transport Services.” Policy Brief 13 Clim-Dev Africa.

- Bailey, D. (2020). Re-thinking the fiscal and monetary political economy of the green state. New Political Economy, 25(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1526267

- Bergin, T., & Bousso, R. (2020). Special Report: How Oil Majors Shift Billions in Profits to Island Tax Havens. https://www.reuters.com/article/global-oil-tax-havens-idUSKBN28J1IK

- Bergman, N. (2018). Impacts of the fossil fuel divestment movement: Effects on finance, policy and public discourse. Sustainability, 10(7), 2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072529

- Berman, N., & Fong, C. (2023). Climate Finance Gains Momentum Ahead of COP28. October 26th Council of Foreign Relations. Retrieved November 17, 2023, from https://www.cfr.org/article/climate-finance-gains-momentum-ahead-cop28.

- Boneva, L., Ferrucci, G., & Mongelli, F. P. (2022). ‘Climate change and central banks: What role for monetary policy?’. Climate Policy, 22(6), 770–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2070119

- Bracking, S., & Leffel, B. (2021). Climate finance governance: Fit for purpose? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 12(4), e709. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.709

- Bryant, G., & Webber, S. (2024). Climate finance: Taking a position on climate futures. Agenda Publishing.

- Campiglio, E., Dafermos, Y., Monnin, P., Ryan-Collins, J., Schotten, G., & Tanaka, M. (2018). Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nature Climate Change, 8, 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0175-0

- Carbon Tracker. (2020, December 14). Groundhog pay: How executive incentives trap companies in a loop of fossil growth.

- Carbon Tracker. (2022). Still flying blind: The absence of climate risk in financial reporting.

- Carter, L. (2020). The ecosystem of private investment in climate action. Invest4Climate knowledge series. . United Nations Development Programme.

- Chancel, L., Bothe, P., & Voituriez, T. (2023). Climate Inequality Report 2023 World Inequality Lab Study 2023/1.

- Cobham, A., & Janský, P. (2018). Global distribution of revenue loss from corporate Tax avoidance: Re-estimation and country results. Journal of International Development, 30(2), 206–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3348

- CPI. (2023). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2023. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2023/

- Dordi, T., Gehricke, S. A., Naef, A., & Weber, O. (2022). Ten financial actors can accelerate a transition away from fossil fuels. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 44, 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2022.05.006

- The Economist. (2023). A new Bretton Woods. February 25th, 78.

- Gabor, D. (2021). The Wall Street consensus. Development and Change, 52, 429–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645

- GCF. (2023). Green climate fund projects. Retrieved from November 20, 2023. https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects/dashboard

- GFANZ. (2022). Investment Requirements of a Low-Carbon World: Energy Supply Investment Ratios.

- Green, J. (2021). Beyond carbon pricing: Tax reform is climate policy. Global Policy, 12(3), 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12920

- Harvey, F. (2023). World Bank spent billions of dollars backing fossil fuels in 2022, study finds. The Guardian, September 12. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/sep/12/world-bank-spent-billions-of-dollars-backing-fossil-fuels-in-2022-study-finds?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

- ICRICT. (2019). A roadmap for a global asset registry. https://bit.ly/2JpEEgd

- IISD. (2023). How fossil fuel subsidies are hurting the energy transition. August 30. https://www.iisd.org/articles/iisd-news/how-fossil-fuel-subsidies-are-hurting-energy-transition#:~:text=Analysis%20from%20the%20International%20Institute%20for%20Sustainable%20Development,trillion%20to%20subsidize%20climate-heating%20fossil%20fuels%20in%202022

- IMF. (2019). Tackling global tax havens. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2019/09/tackling-global-tax-havens-shaxon

- IMF. (2021). Still not getting energy prices right: A global and country update of fossil fuel subsidies, IMF Working Paper, Washington: IMF.

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

- Kharas, H. (2022). A Global Sustainability Program: Lessons from the Marshall Plan for addressing climate change. Policy Brief Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings.

- Langley, P., & Morris, J. H. (2022). Central banks: Climate governors of last resort? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(8), 1471–1479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20951809

- Markandya, A., & Gonzalez-Eguino, M. (2019). Integrated assessment for identifying climate finance needs for loss and damage: A critical review. In Mechler, P. et al (eds.), Loss and damage from climate change: Climate risk management, policy and governance. Springer.

- McCulloch, N. (2023). Ending fossil fuel subsidies: The politics of saving the planet. Practical Action Publishing.

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. The Sustainability Institute.

- Muttitt, G., & Kartha, S. (2020). Equity, climate justice and fossil fuel extraction: Principles for a managed phase Out. Climate Policy, 20, 1024–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1763900

- New Climate Institute. (2021). Debt for Climate Swaps’ https://newclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NewClimate_Debt-for-Climate-Swaps_PolicyMemo_March2021.pdf

- Newell, P. (2001). Managing multinationals: The governance of investment for the environment. Journal of International Development, 13, 907–919.

- Newell, P. (2011). The governance of energy finance: The public, the private and the hybrid. Global Policy, 2(1), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-5899.2011.00104.x

- Newell, P. (2021). The business of climate transformation. Current History, 120(829), 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2021.120.829.307

- Newell, P., & Simms, A. (2020). Towards a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty. Climate Policy, 20(8), 1043–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1636759

- NGFS (Network for Greening the Financial System). (2022). NGFS Climate Scenarios for Central Banks and Supervisors 2022. https://www.ngfs.net/en/ngfs-climatescenarios-central-banks-and-supervisors-september-2022

- Oil Change International & Friends of the Earth. (2024). Public enemies: Assessing MDB and G20 international finance institutions' energy finance. Washington: OCI.

- Quinson, T. (2023). Banks Need Even Bigger Low-Carbon Pivot to Avert Climate Crisis. Bloomberg, February 28. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-28/banks-need-even-bigger-low-carbon-pivot-to-avert-climate-crisis?leadSource=uverify%20wall

- Reclaim finance. (2023). Throwing Fuel on the Fire: GFANZ financing of fossil fuel expansion. https://350.org/press-release/throwing-fuel-on-the-fire-gfanz-members-provide-billions-in-finance-for-fossil-fuel-expansion/#:~:text=Paris%2C%20January%2017th%202023%20%E2%80%93%20After%20committing%20to,group%20of%20NGOs%2C%20including%20Reclaim%20Finance%20and%20350.org%281%29

- SCF. (2022). UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance Report on progress towards achieving the goal of mobilizing jointly USD 100 billion per year to address the needs of developing countries in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation.

- Schoenmaker, D. (2021). Greening monetary policy. Climate Policy, 21(4), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1868392

- SEI, IISD, ODI, Climate Analytics, CICERO, and UNEP. (2023). The Production Gap: The discrepancy between countries’ planned fossil fuel production and global production levels consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C. http://productiongap.org/

- Skovgaard, J., & Van Asselt, H. (2018). The politics of fossil fuel subsidies and their reform. Cambridge University Press.

- Tienhaara, K., Thrasherb, R., Simmons, A., & Gallagher, K. (2022). Investor-State disputes threaten the global green energy transition. Science, 376(6594), 701–703. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo4637

- UNCTAD. (2019). Financing a global green new deal trade and development report.

- UNCTAD. (2022). Financing for development: Mobilizing sustainable development finance beyond COVID-19 Trade and Development Board Intergovernmental Group of Experts on Financing for Development Fifth session Geneva, 21–23 March 2022.

- UNEP. (2022). The emissions gap report.

- UNEP. (2023). The adaptation gap report.

- Volz, U., Akhtar, S., Gallagher, K. P., Griffith-Jones, S., Haas, J., & Kraemer, M. (2020). Debt relief for a green and inclusive recovery: A proposal. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, SOAS, University of London, Boston University.

- Welsby, D., Price, J., Pye, S., & Ekins, P. (2021). Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world. Nature, 597, 230–234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03821-8

- Woolfenden, T. (2023). The debt-fossil fuel trap: Why debt is a barrier to fossil fuel phase-out and what we can do about it. Debt Justice.