ABSTRACT

Transparency in carbon markets is considered critical to ensure market effectiveness and public accountability. Low levels of transparency and lack of participation of non-governmental actors are persistent criticisms of Chinese (pilot) emission trading systems. Building on debates around authoritarian environmentalism and China's role therein, this article analyses transparency, manifested as information disclosure, in China's national carbon emission trading scheme (C-ETS) – the largest carbon emission market worldwide. Using expert interviews and content analysis, the article outlines practices of C-ETS information disclosure and discusses its characteristics in the context of China’s environmental governance. Key findings include discrepancies both between central and provincial governments related to information disclosure, and between different provincial governments. And while most industry actors lack interest and capacity to engage in C-ETS disclosure, environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), by contrast, are significantly more involved in the policy process and information disclosure, often as ‘eco-elites’. Overall, this reveals that international and domestic ENGOs retain high-level channels to influence policy design and implementation. Yet, ENGO input is not pursued as a public good valuable for its own sake, but sought strategically as a means to the larger goal of efficient market functioning. This type of ‘strategic transparency,’ as we call it, suggests that China’s environmental governance model – regularly considered to be a key example of authoritarian environmentalism – instead represents an evolving mixture of liberal and illiberal tactics.

Key policy insights

The case of C-ETS reveals that China’s model of authoritarian environmentalism is opening up to include information disclosure and selective participation by ENGOs.

Information disclosure, however, still remains limited, with significant differences between provinces and difficulties accessing records via official websites and social media.

Industry actors regulated under C-ETS do not have sufficient capacity to engage in information disclosure and often prefer to leave this to third-parties with varying track records.

C-ETS information disclosure and ENGO participation represents a type of ‘strategic transparency’, i.e. transparency as a way to enhance market efficiency.

Instead of seeing transparency as a universal objective, policymakers should anticipate strategic transparency when engaging with carbon markets in authoritarian regimes.

1. Introduction

Environmental performance under democratic versus non-democratic regimes is a growing topic of debate. Some scholars maintain that democracies can better facilitate environmental governance (Acheampong et al., Citation2022; Buitenzorgy & Mol, Citation2011; Escher & Walter-Rogg, Citation2020; Lv, Citation2017), whereas others note the benefits of non-democratic governance in light of power centralization (Eckersley, Citation2019; Fredriksson et al., Citation2005; Hall, Citation2015; Pickering et al., Citation2020). Non-democratic governance to address environmental issues has been referred to as ‘authoritarian environmentalism,’ wherein low civic participation and strong central authority contribute to rapid policy outputs intended to ameliorate environmental problems.

Transparency is an important subject among these environmental governance debates (Chen, Citation2019; Gupta & Mason, Citation2016). Transparency helps stakeholders to see gaps in environmental governance and thus be motivated to enact reforms (Weikmans et al., Citation2020). Moreover, information disclosure – one form of transparency – can improve market functioning and also result in a ‘naming and shaming’ effect, thus exerting external pressure (Ciplet et al., Citation2018; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen et al., Citation2018; Weikmans et al., Citation2020). When it comes to market governance, transparency is particularly important for efficiency, liquidity, valuation, and sustained competition (Ali et al., Citation2022; Bhimavarapu et al., Citation2022; Mehrpouya & Salles-Djelic, Citation2019). Therefore, transparency is seen as an essential precondition for effective carbon mitigation actions, including emission trading schemes (ETS). Yet, when it comes to authoritarian environmentalism, transparency is notoriously low (Kostka & Mol, Citation2013; Ran, Citation2015).

China is considered a key example of authoritarian environmentalism (Böhmelt, Citation2014; Li & Shapiro, Citation2020; Shen et al., Citation2019) and, relatedly, low transparency (Hsu et al., Citation2012; Zhang et al., Citation2010). Nonetheless, in the last decade, China has embraced market governance to address environmental problems. As the largest ETS globally, China’s national ETS (C-ETS) provides an important example of market governance in the service of promoting the country’s dual carbon targets of peak emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 (Information Office of the State Council, Citation2021). Officially commencing in 2021, after extensive pilots at the provincial level, the C-ETS combines market governance with a strong central state. Covering more than 4 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide despite now only including the electricity sector, the C-ETS is the largest carbon market globally, amounting to 40% of China’s national emissions (ICAP, Citation2023). With plans for expansion, authorities have indicated that cement or steel will be the next of the eight sectors to ultimately be included, amounting to 60% of China's total carbon emissions upon completion (Centre for Energy and Environmental Policy Studies, Citation2022).

One of the key preconditions for ETS to function in all jurisdictions is transparency (Milanés Montero et al., Citation2020; Suk et al., Citation2018). Transparency is especially important when it comes to optimal pricing by reducing market information asymmetry (Han et al., Citation2022; Kaya & Liu, Citation2015). Yet, China’s ETS – both the national and the pilot provincial ETSs before it – face criticism of low transparency (Zhao et al., Citation2016; Zhou et al., Citation2019). Low levels of information disclosure in the pilots were a prime reason for inefficiency (Zhao et al., Citation2016; Zhou et al., Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2022), and may impede the functioning of the national market too. However, given that the C-ETS is one of the world’s carbon markets to operate under authoritarian environmentalism, cultivating higher transparency and information disclosure can prove difficult.

Given its recent implementation, research on the C-ETS remains limited, in particular when it comes to information disclosure. Filling this gap, this article analyzes C-ETS information disclosure under the influence of authoritarian environmentalism and Chinese environmental governance. In particular, we focus on the unique mix of authoritarian and liberal governance that characterizes the C-ETS. As quintessentially neoliberal tools, carbon markets require features that may challenge authoritarian governance, such as non-governmental participation and transparency. Yet, illiberal regimes are nonetheless deploying this neoliberal tool in unprecedented ways, with China at the forefront. We investigate how Chinese central and provincial governments implement transparency policy in the C-ETS, paying particular attention to the role of non-governmental actors: carbon emitters participating in the markets, and national and international environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) that monitor and assist with market establishment and functioning. In doing so, our research explores the following research questions:

How does the interplay between authoritarian environmentalism and the imperative for market transparency manifest within the C-ETS?

What role do non-governmental actors play in shaping information disclosure policy and practices within the C-ETS?

Investigating these key questions, our goal is to further nuance the literature on authoritarian environmentalism by demonstrating the interplay between liberal and illiberal governance in the world’s largest carbon market. In doing so, we draw out insights for policymakers engaging with the introduction and refinement of ETSs in non-democratic contexts. As carbon market initiatives grow globally, there is a need to better understand how key features, such as transparency and civil society participation, are modified and adapted when deployed by illiberal regimes and the overall impact on policy outcomes.

This article proceeds as follows: Section 2 elaborates on the theoretical basis of authoritarian environmentalism, followed by Section 3 on methodology. Section 4 then presents the results, detailing the regulations for C-ETS information disclosure, the disclosure performance among different provinces, and the operations from the perspective of entities and ENGOs. The final two sections discuss the results and policy implications, reflecting on the role of market mechanisms in the future of climate governance in authoritarian regimes.

2. Can authoritarian environmentalism be transparent?

Authoritarian environmentalism provides a model for addressing environmental problems under dire circumstances. Heilbroner (Citation1974) introduced the concept, suggesting that to avoid environmental catastrophe, an authoritarian centralised government would be needed to control limited resources through compulsory means. Many authors have since elaborated on this concept (also using the terms eco-authoritarianism or eco-dictatorships) and its prospects for addressing urgent environmental issues in the twenty-first century (Beeson, Citation2010; Gilley, Citation2012; Shen et al., Citation2019). Countries such as China, Singapore, and Iran are all considered cases (Chen, Citation2019; Wang & Jiang, Citation2020). China in particular has revived debates surrounding authoritarian environmentalism, given the country’s recent progress in several environmental domains (improving air and water quality, combating desertification, and reforestation), alongside rising questions over whether or not developed democracies can adequately address the most pressing global environmental challenges (Kwon & Hanlon Citation2016).

According to Beeson (Citation2010), authoritarian environmentalism has two prominent features: governmental domination of the policy process with no channels for broad-based civic input (despite selective channels for expert and technocratic input) and restrictions on individual liberties to achieve environmental outcomes. Other important characteristics, such as power centralisation, low transparency, limits on public participation, and preference for command and control over market instruments, are consequences of these core features (Beeson, Citation2018; Gilley, Citation2012; Lo, Citation2015). Chinese environmental governance retains many of these features (Li et al., Citation2019; Lo, Citation2015; Shen et al., Citation2019). Overall, authoritarian environmentalism can be seen as relying not on ‘input-oriented legitimacy’ (i.e. legitimacy derived from a clear and transparent process, agreed upon though broad-based democratic consultation), but rather ‘output-oriented legitimacy’ (legitimacy derived from governmental delivery of stated goals) ( Scharpf, Citation2003). The result, some scholars suggest, may be better environmental governance outcomes (Eckersley, Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2019; Povitkina, Citation2018; Shearman & Smith, Citation2007).

Authoritarian environmentalism is often directly contrasted with neoliberal or market-oriented environmental governance (Biebricher, Citation2020). Yet, in the case of China, the government mixes authoritarian and neoliberal features. This combination has been most clear with China’s economic governance, wherein the central government has experimented with market-oriented economic growth through special economic zones. Unlike in thoroughly neoliberal regimes such as the United States and United Kingdom, China’s market governance is permitted as an exception rather than followed as the rule (what Ong (Citation2006) refers to as ‘neoliberalism as exception’). The resulting governance structure reveals a type of ‘graduated sovereignty’ wherein market techniques are deployed selectively in certain areas in the pursuit of economic growth and guided by a powerful state (Ong, Citation2006, Citation2007).

China’s environmental governance shares similar features with its economic governance, with carbon markets offering a prime example. Carbon markets are deployed to more efficiently meet China’s dual carbon targets. For efficient functioning, they require features that are not characteristic of authoritarian environmentalism, such as non-governmental participation and transparency. They provide a robust case for examining how neoliberal governance techniques emerge and develop within illiberal governance contexts.

This study focuses specifically on the interplay between authoritarian environmentalism and transparency within China’s carbon markets. As with authoritarian environmentalism, there is no singular definition of transparency, but the term is most often associated with accountability, government efficiency, and especially information disclosure (Ball, Citation2009; Gupta & Mason, Citation2016; Yu & Robinson, Citation2012). The degree of information disclosure is directly linked to the degree of government openness because it provides the public and non-governmental actors with the opportunity to monitor government performance (Fuks & Kabanov, Citation2020; Harrison et al., Citation2012; Lourenço et al., Citation2015).

Achieving information disclosure in China’s environmental governance has been challenging, given its authoritarian features (Hsu et al., Citation2012). Meanwhile, policy implementation poses another challenge under authoritarian environmentalism (Gilley, Citation2012; Li et al., Citation2019). The central government has set the ‘open government’ goal, but it is up to local governments to achieve (State of Council, Citation2019) . A survey of environmental information disclosure systems in over 100 Chinese cities illustrates that local governments have varying degrees of influence on the level of information disclosure (Tian et al., Citation2016). Ran (Citation2015), for instance, identifies the lack of transparency in implementation and regulation as one reason for poor environmental governance implementation in China. Under authoritarian governance, restrictions on non-governmental actors and the government’s dominance of policy formulation allow governments to respond to environmental crises quickly (Shearman & Smith, Citation2007), but non-governmental actors must rely only on the information that officials are willing to disclose when scrutinizing government performance and ensuring accountability.

For the efficient functioning of markets in particular, transparency is crucial. Pricing signals, for example, must be readily available to market players. Other features in the setup of markets – liquidity, enforcement cost and efficiency, for example – also benefit from higher levels of transparency. The efficiency of policy formulation and implementation therefore relies on the capacity of officials along with support from technical experts, referred to as ‘eco-elites’ (Gilley, Citation2012; Lo, Citation2021). Thus, under authoritarian environmentalism, officials are crucial to policy outcomes. With this in mind, our study examines how eco-elite input is integrated under environmental authoritarianism in order to achieve not broad-based public participation, but rather ‘strategic transparency’ – that is, transparency aimed at ensuring the efficient functioning of markets, but not pursued as a goal in and of itself.

3. Methodology

This article draws from semi-structured interviews, content analysis, and information collected from workshops and conferences. Interviews were conducted with individuals working for research institutions, ENGOs, consultancies, and verification agencies. Potential interviewees were selected based on expertise and knowledge of the C-ETS from well-known agencies to entities disclosed by the government. Through online information or networking, more than 100 potential interviewees were approached, with 14 agreeing to be interviewed. Among these interviewees, there were four from academia, four from carbon consulting firms and think tanks, two from environmental non-governmental organizations, and four from verification agencies. Notably, interviewees had diverse backgrounds and experience across multiple sectors.

All interviews, including follow-ups, were conducted via digital meetings or in-person discussions from October to December 2021, June to July 2022, and November 2023. The interviews, ranging from 40 minutes to 2 hours, were recorded with interviewee consent. Participants were coded by their role (e.g. V2 for the second interviewee from third-party verification). Codes and brief backgrounds of all interviewees are detailed in Appendix 1. All but two of the interviews were conducted in Chinese and then transcribed and translated to English (A1 and A4 were conducted in English).

To protect the privacy of informants and encourage them to provide more information, this study ensured the anonymity of all interviewees. We acknowledge, however, that anonymity does not guarantee trustworthy responses. There are a number of reasons why interviewees might not provide sincere responses, ranging from wanting their work to appear effective to fearing reprisal for criticism even in the face of anonymity. This is true across political contexts but is likely further complicated by the political milieu in China. Respondents may feel constrained from speaking openly or may feel obliged to only make positive observations due to the politically sensitive nature of China’s carbon market. Indeed, interviews conducted in illiberal settings pose many challenges, given all the elements of lack of transparency and information disclosure discussed above. Yet, as noted, the challenge is not entirely unique to illiberal contexts, as many interviewees in liberal democracies also have incentives to reveal only that information which reflects well on themselves or their organization.

The small interview size presents another limitation of this study. Challenges related to China’s illiberal governance model also likely had an impact on the interviewee size. Despite contacting a range of stakeholders, informants in key roles were likely less willing to respond to our interview request because of wariness to disseminate information, thus undermining the representativeness of our sample and the generalizability of our findings. The interviews were thus conducted with these limitations in mind and complemented with content analysis.

Content analysis was conducted utilizing various publicly available materials. Regulations and standards from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) and National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), all originally in Chinese, pertaining to carbon emission and allowance trading were collected, covering all aspects of the C-ETS process (See Appendix 2). Databases from official websites or research institutions, such as the European Environment Agency and Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, were also employed to compare the C-ETS with other environmental issues and with ETS in other countries. Key insights from industry reports were derived, predominantly from renowned ENGOs and institutions specializing in the carbon market. News reports from official or credible press (e.g. State Council Information Office, Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange and China Dialogue) were also included as sources. Research papers or book chapters on C-ETS, authoritarian environmentalism, transparency and information disclosure were used for framing and discussion.

In addition, workshops or seminars held by ENGOs, grey literature from interviewees, and private conferences contributed useful information. Unpublished information shared by the interviewees, including unreleased regulation drafts, administrative changes at the ministry level, and common practices within the industry were also consulted in conducting our analysis.

4. Results

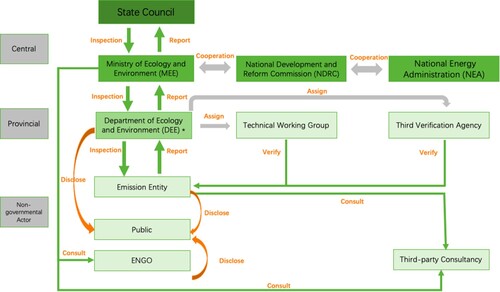

At its core, C-ETS information disclosure involves the central and provincial governmental bodies, polluting entities, and national and international non-governmental actors. In practice other actors are also included, such as consulting firms or verification agencies, given that some polluting entities seek advice from carbon consulting firms for market transactions or to find suitable trading partners, while some verification agencies are involved in carbon emissions verification. depicts the relations between these actors. The sub-sections below explore C-ETS information disclosure from the perspective of these three main actors – government, polluting entities, and non-governmental (primarily ENGOs), respectively. Section 4.1 presents information disclosure from the governmental perspective, outlining the disclosure bodies and regulations (section 4.1.1), provincial level disclosure performance (section 4.1.2) and access to information (section 4.1.3); Section 4.2 presents information disclosure from the perspective of entities; and Section 4.3 presents the role of ENGOs within C-ETS information disclosure.

4.1. Disclosure from government

As the main body developing and implementing C-ETS regulations, the Chinese government (both central and provincial) plays a dominant role in information disclosure. At the central level, NRDC and MEE are the two main governmental agencies responsible for the C-ETS. They both issue regulations that must then be followed by provincial departments, as outlined in .

4.1.1. Disclosure bodies and regulations

At the central level, NDRC was assigned as the C-ETS competent authority in 2015. In 2018, however, the State Council reformed the department’s functions, transferring C-ETS administrative rights to the newly founded MEE (Li, Citation2018). Yet, in 2021, NDRC was again given some responsibilities in C-ETS management, together with auxiliary departments, such as the National Energy Administration and the National Bureau of Statistics. Despite these institutional changes, MEE remains the primary national-level department responsible for C-ETS and its information disclosure.

Most C-ETS regulations to date have been issued by MEE (See Appendix 2). These regulations cover general rules and specific sector guidance for system design, registry, allocation, trading, reporting and verification. The topics that these regulations cover are similar to those covered by other ETS regulations, such as the EU ETS, the oldest and most mature ETS. Notably, however, and in contrast to EU ETS regulations, C-ETS regulations do not include regulations for auctions and linkages (See Appendix 3). This may be related to the fact that C-ETS was in an early stage at the time of this research, and auctions and linkages are keystones of more advanced carbon markets. Additionally, because the C-ETS was in its early stages during this study, the related regulations imposed low penalties for violations, resulting in weak constraints on entities.

While MEE issues most C-ETS regulations, interviewees indicated that the agency must nonetheless work with other departments to develop these regulations (C1, E1 and A4). Indeed, a recent C-ETS regulation was published jointly by NDRC, MEE and the National Bureau of Statistics, indicating that agencies collaborate to collectively promote the implementation of the C-ETS (MEE, Citation2022b; NDRC, Citation2022). A former employee at a national think tank considered this type of cooperation to be the result of challenges with interdepartmental staff transfers and overlapping functions among agencies (C1). Given that NDRC was first in charge of C-ETS development, NDRC officials served as the primary coordinator of the ETS and maintain a comprehensive understanding of its design and implementation. Following the transfer of C-ETS administrative rights to MEE, and due to staffing requirements, some officials remained in NDRC while assisting MEE with C-ETS management. Some interviewees (A2) voiced concerns about the differing objectives of MEE and NDRC (put simply, environment versus development, respectively), but others (C1) maintained that consistent data management would prevent disruption despite these differences.

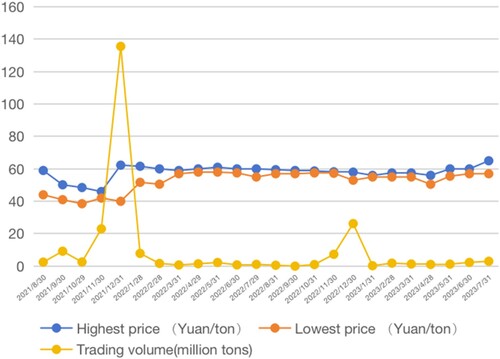

Appendix 4 details C-ETS information disclosure regulations, legislation, and procedures. Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange (SEEE) is the trading agency responsible for disclosing daily trading information (MEE, Citation2021b). SEEE discloses this data proactively (), and has also promulgated additional regulations to facilitate trading and disclosure (SEEE, Citation2021). The price of carbon as traded on the market is an important signal for emissions reduction, ultimately reflecting the abatement costs faced by the industry in light of their pollution reduction requirements as set by the government. A higher price typically indicates more stringent pollution reduction requirements. Compared to other ETSs worldwide, the price of carbon emissions in China is relatively low, suggesting the limited effectiveness of the C-ETS system in driving significant emissions reductions (C3). Yet, it is also typical for prices to start low and gradually increase over time, as pollution requirements are ratcheted up.

Moreover, the overall trading information disclosure in the C-ETS is rather simplistic. One interviewee with experience in different countries (C2), mentioned that the C-ETS trading information merely includes the number of trades, the opening and closing price, the highest and lowest price, the range, and the average price. In contrast, the EU ETS provides detailed trading information down to each installation unit and its allowance and emissions (European Environment Agency, Citation2022). While trading entities have the right to request information from SEEE, there are no news reports or information from the entity side to support this proactively.

4.1.2. Provincial level disclosure performance

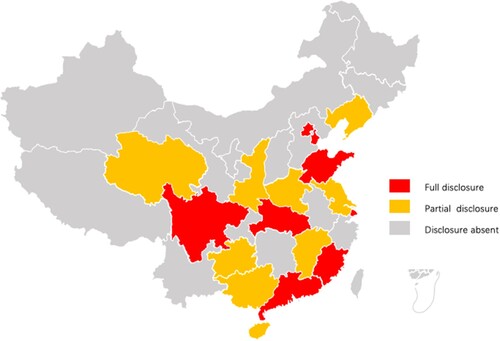

While regulations are set at the central government level and SEEE is responsible for carbon price disclosure, information disclosure also occurs at the provincial level. The provincial level Departments or Bureaux of Ecology and Environment (DEE or BEE) are responsible for disclosing the measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV)Footnote1 data, arguably the most important part of the C-ETS. However, the disclosure performance among different provinces varies significantly.

This discrepancy in information disclosure among provinces can be seen in the disclosure of the key entity lists – i.e. the list of all the major polluting entities mandated to participate in the C-ETS. Before officially establishing the C-ETS, the central government disclosed a list of all the polluting entities that would be included in the ETS. The provincial governments were then supposed to issue a verified list of all these entities within their province that would serve as the definitive reference for the MRV process. Yet, as of January 2022 – the completion of the first compliance year of C-ETS – thirteen of China’s thirty-two provinces had not made their entities list public (), despite some of these provinces having already completed their allowance approvals and clearances (Qinyue Environment, Citation2022). These provinces had thus omitted a key element of C-ETS information disclosure.

Figure 3. Key Emission Entity List Disclosure in Different Provinces (as of January 2022). Source: authors.

Another indication of provincial level information disclosure disparities is the large discrepancy in the entity lists released by the central level MEE and some provincial level DEEs. In the initial key entity list published by MEE, for example, 84 entities in Guangdong province were included in the C-ETS, but only eight entities were confirmed in the list published by the Guangdong DEE (Guangdong DEE, Citation2022).

A wide disparity in MRV practice and capacity also exists due to variations in the third-party agency qualifications, as pointed out by interviewees with ample experience in MRV (V1, V2, and C1). The central government published two guidelines to help MRV operations: Guidelines for Enterprises GHG Verification (Trial) and Guidelines for Verification Methodology and Reporting of Entity GHG Emissions (Power Generation Facilities) (MEE, Citation2021c, Citation2022a). However, according to interviewees (V1 and C1), these guidelines are not sufficient in explicating the MRV process and require additional clarifications. Beyond this, one practitioner interviewee stated that they hoped to engage more in the formulation of regulation, meaning gaining more access and feedback channels to the officials (C3). However, an interviewee working with government institutions (E1) disagreed with this proposal, suggesting participation of third-party verification agencies could be counter-productive:

“They [the third-party verifiers] know the upstream and downstream loopholes; instead of reporting to the government, they tell companies how to use the loopholes. In my opinion, they cannot advise from a completely neutral position, but for their own benefit.”

Compliance status is another essential indicator for an ETS. The first compliance year for C-ETS ended in December 2021. In the following months, provinces verified their compliance and disclosed before May 2022. A few provinces (Hainan, Shanghai, and Gansu) released the compliance data in January 2022, whereas the majority published the information from March to May. Some provinces also disclosed non-compliance and penalty data (See Appendix 5). One possible motivation for provincial governments to disclose proactively and in advance could be their high compliance rates. Such an indication of good performance may help to establish a good image for these provinces. However, not all provinces disclosed their compliance status. The compliance data of Beijing, Tianjin, and Xinjiang (Bingtuan) only became available in an MEE official research report in December 2022.

Compared to the uneven disclosure performance of provincial environmental departments, the central government aims to reach a more transparent C-ETS process. Verification data quality is a key aspect of the MRV stage. After one official measurement agency whistleblew on a possible data falsification case in March 2021, MEE investigated and confirmed the situation publicly in May 2021, imposing penalties on the offenders (Xu, Citation2021). MEE investigated further the MRV data quality issue and proactively disclosed the names and punitive measures of involved emission entities and third-party agencies in March 2022 (MEE, Citation2022c). Despite such data quality issues potentially undermining their credibility, the central government is apparently willing to acknowledge and disclose such information.

4.1.3. Access to the disclosed information

Information dissemination is a part of information disclosure, as it impacts the target audience and the way the public can access information. In the C-ETS, official government websites and other online media are two ways to access disclosed information.

MEE archives C-ETS regulations on their website for public access, but in practice the information is not easily accessible. Unlike the EU ETS and some provincial Chinese ETS websites, there is no separate section for C-ETS on the official government website. The search engine further complicates access. Entering simple C-ETS keywords leads to results that often present relevant news, not regulations or trading information. Moreover, the regulations do not appear in the ‘Policy Documents’ section but in ‘Open Information’ section.

Access via other online media is easier and more comprehensive information can be found. One example here is a website gathering comprehensive, carbon-related information, from green infrastructure to carbon asset management, although the volume of information makes it hard to see the forest for the trees. Another source of information is WeChat Public Platform, where institutions and practitioners publish C-ETS information soon after it is decided upon. Through WeChat, C-ETS information is disseminated rapidly, making it a first-hand information source for many C-ETS practitioners. As one practitioner (C3) stated:

“Policy information about China's carbon market is often first available in WeChat articles … but you need to know who has this information. Staff from research institutions, exchanges and other institutions related to the carbon market may be the first to post these policy developments on their WeChat.”

4.2. Disclosure from entities

In the C-ETS, the polluting entity has the obligation to disclose trading information and to provide emission data and other relevant information to officials and the public (MEE, Citation2021b). In practice, only a few state-owned enterprise entities disclose some C-ETS information. Interviews reveal that many private entities have limited interest in and capacity for C-ETS engagement at all, and even less in disclosure specifically (C3, V1 and V2). Despite government-provided training, entities view C-ETS participation as an additional burden to daily operations.

To support ETS operation, MEE developed a platform which is open to all entities and third-party agencies. MEE also published a technical document addressing common ETS questions (MEE, Citation2022d). Despite these efforts, some entities still lack the resources or ability to comply. To help with compliance, entities often prefer to hire third-party consultancy companies. These often have similar qualification problems as the verification agencies mentioned in section 4.1.2.

One result of the above situation could be the threat of data falsification during the C-ETS first MRV process. In the early preparation stage of C-ETS, a few entities missed the chance to measure their actual carbon contents – that is, the precise amount of carbon emissions they produce, a crucial measurement for accurate monitoring and verification within an ETS. To ensure compliance, one consultancy agency allegedly suggested them to falsify the test date.

Given the challenges in daily operations, entities find it hard to spare resources to cope with C-ETS requirements. One interviewee (V1) explained that, when the whole power industry is facing operation difficulties,

“Someone who wasn't paying much attention to the regulation before would suddenly face a cost of tens or even hundreds of millions [Yuan, i.e. 1.4-14 million USD] in order to comply and they wouldn't feel it was fair.”

4.3. ENGO participation

Although ENGOs are not directly engaged with C-ETS operations and are not mentioned in regulations, they play an unexpected role in the C-ETS and its information disclosure. Contrary to the idea that the Chinese government leaves little room for non-governmental participation (Wu et al., Citation2017), ENGOs have deep involvement in the C-ETS via regulation formulation and information dissemination.

Some international and domestic ENGOs with interest in Chinese environmental governance and ETS state that they have cooperated with government institutions and officials closely by making policy recommendations (E1 and E2). ENGOs do so by inviting practitioners and organizations, including third-party verification agencies and polluting entities, to their private forums to receive feedback and inputs for their policy recommendations. Officials from MEE and other departments also participate in these private dialogues. One expert explained that compared to other traditional environmental issues, such as water pollution and air quality, the Chinese government had left a relatively large scope for ENGOs in C-ETS development (A3). ‘Discussions are ongoing,’ the expert explained, ‘including the formulation of plans for the participation of NGOs in environmental governance … Not only the government, but also NGOs are more involved in the ETS supervision process.’

The reason for ENGO involvement could be that these organizations are able to complement government activities with their expertise, in particular the international ENGOs with a background in ETS capacity building. Almost all ENGOs focused on the C-ETS field are government-oriented and active in research. To some extent, similar to official experts and research institutions, these ENGOs take part in C-ETS regulation formulation as ‘eco-elites’ (Gilley, Citation2012). The 2014 environmental protection law provides the legal basis for such ENGO participation (Froissart, Citation2019), given that it includes a new chapter on information disclosure and participation stipulating that civil society has the right to participate and monitor environmental protection work. This law indicates recognition of the need for and willingness to allow some degree of political space for non-governmental participation.

Besides contributing to policy development, ENGOs also participate in stakeholder communication and capacity building. C-ETS knowledge is disseminated largely through WeChat. When ENGOs learn about new C-ETS regulations, they publish interpretive articles about the latest C-ETS developments on this platform to inform their subscribers – primarily practitioners. Although ENGOs engage in public communication, the content and language they use are rather professional, targeting practitioners rather than the general public. In that sense, the dissemination role that ENGOs play is expert-oriented.

Finally, some ENGOs have deep cooperation with key emission entities and third-party verification agencies. Using their expertise in C-ETS regulation, ENGOs have developed a guidance handbook and organized forums and courses which focus on C-ETS capacity building for key entities, third-party agencies, and officials (E1 and C2). A few ENGOs have also disclosed emission information using their connections with industry to gain this information.

5. Discussion

Building on the previous sections describing information disclosure in the C-ETS, this section discusses how Chinese environmental governance is evolving to incorporate market mechanisms and associated features (transparency and civil participation) alongside authoritarian governance. The discussion addresses three important aspects of this merger of liberal and illiberal governance: central versus provincial power, the rising role of ENGOs, and transparency under authoritarian governance.

5.1. Central versus provincial power

Under authoritarian environmentalism, power is concentrated in the central government, thus allowing for quicker and potentially more efficient action. Provincial governments, by contrast, maintain less decision-making authority (Li et al., Citation2019; Schreifels et al., Citation2012). In the case of C-ETS information disclosure, the central government outlines disclosure regulations which provincial governments must follow, demonstrating decentralized implementation of a centrally directed policy. While the central government emphasizes the necessity of C-ETS for its dual carbon objectives, provincial performance in compliance varies, revealing limitations in implementing centralized policies at local levels.

In line with authoritarian environmentalism, major power differences between the central and provincial governments were found in the C-ETS. The central government has absolute control over policy formulation and provincial governments strive to implement (or not) centralized mandates (Shen et al., Citation2019). The efficiency of central policy formulation is highlighted by the coverage and quality of MRV data disclosure. However, the central government encourages provincial governments to draw up stricter emission mitigation policies, indicating some policymaking autonomy at the provincial level, which is inconsistent with the notion of environmental authoritarianism as outlined by Beeson (Citation2010) and Gilley (Citation2012).

Additionally, disclosure performance between different provincial governments and the regulated entities therein varies greatly. This confirms that there is some degree of autonomy when it comes to implementation of central mandates, while also confirming critiques of Chinese environmental governance in policy implementation (Gilley, Citation2012; Li et al., Citation2019). Ran (Citation2015) identifies the short-lived focus on environmental issues and symbolic implementation as reasons for poor policy implementation. Nonetheless, in the C-ETS case, most provincial environmental authorities do fulfil the disclosure requirements, some even exceeding them. This might indicate improvements in implementation with provincial governments putting more attention on mitigation, along with the central government.

Climate policy performance is closely related to the capacity of the state and its institutions (Lindvall & Karlsson, Citation2024). This capacity encompasses not only the technical and professional expertise required for policy formulation and implementation but also the governance structures, resource allocation, and the ability to coordinate with other stakeholders (Wu et al., Citation2015). In centralized regimes like China, the central government may possess stronger decision-making and implementation capabilities, enabling it to swiftly enact policies and achieve targets. However, the role of local governments and non-governmental organizations might be restricted, leading to a gap between policy execution and expectations. Conversely, in democratic countries, although the decision-making process may be slower and more complex, increased transparency and public participation often enhance the legitimacy and effectiveness of policies. Ultimately, the capacity of the state and its institutions is crucial to the performance of climate and environmental policies, with this impact varying across different political and governance frameworks.

5.2. The rising role of ENGOs

Another key characteristic of authoritarian environmentalism is the restriction on non-governmental actors’ participation (Beeson, Citation2010). Rather than broad civic participation, authoritarian environmentalism tends to solicit input from highly selective expert channels, which is widely recognized in China’s environmental governance (Böhmelt, Citation2014; Li & Shapiro, Citation2020; Shen et al., Citation2019).

In C-ETS implementation and information disclosure, ENGO participation reveals blurring of the lines between civil society and elite input. Both international and domestic ENGOs play a clear role in the C-ETS, though this role is largely concentrated in the policy formulation stage. ENGOs collaborated with government officials and research institutions proactively to develop C-ETS regulations and share ETS capacity-building experiences. Leading ENGOs also engaged with stakeholders to develop better policy advice and promote C-ETS information dissemination. This cooperation happened primarily at the level of the central government, which actively solicited ENGO participation in policy formulation, including information dissemination policies.

This is not to imply that any ENGOs can participate in policy formulation, nor that their advice is unconditionally adopted. Rather, ENGOs were selected to engage based on their ability to fill gaps in governmental expertise. Selected ENGOs must be competent in practical experience, legal expertise, and a network of social relationships, and produce professional input with policy advocacy capabilities (Lin, Citation2018). In fact, to gain the status of ENGO in the first place, organizations must be registered with the Chinese government, which requires a well-defined scope of operations and an established positive relationship with the government agency in their field (Sheih, Citation2017). Thus, ENGO participation cannot be considered broad public participation. Moreover, ENGOs do not monitor government performance in most cases, but rather disclose information or help make policies more legible to other non-governmental actors (Zhang et al., Citation2016).

Yet, international and domestic ENGO participation in the C-ETS goes beyond what is typically categorized as purely expert input under the selective channels of environmental authoritarianism. ENGO participation seems to blur the boundaries between liberal and illiberal governance, incorporating some degree of public participation through the selective channels of authorized ENGOs, while preventing broad-based, unsolicited public input. This confirms a type of ‘eco-elite’ that goes beyond purely cherry-picked governmental experts while also eschewing broad-based public input. ENGOs are given the opportunity to legitimately participate in the policy process when they can complement officials. Overall, ENGO participation demonstrates that officials are willing to open up some participation space when ENGOs can supplement existing environmental governance expertise.

Eco-elite participation of ENGOs is consistent with recent literature suggesting that the authoritarian environmental model in China is changing. Some scholars have therefore suggested alternative labels, such as ‘responsive authoritarianism’ or ‘deliberative authoritarianism’ (Gao, Citation2019; He & Warren, Citation2011; Weller, Citation2008). Froissart (Citation2019, p. 8) observes a change ‘from factional politics to the formation of an advocacy coalition’ in relation to the acceptance of non-governmental actor consultation in Chinese environmental governance. More recently, Wang et al. (Citation2023, p. 15) demonstrate participation of eco-elites in China’s campaign-style governance with an ‘extremely fast’ response speed. In all cases, these scholars propose a more nuanced understanding of authoritarian governance in China. This does not imply a radical departure from China’s conventional governance model (Rooij et al., Citation2016). The Chinese government still dominates, and the acceptance of non-governmental actor participation is limited and gradual. Similarly, in the C-ETS, ENGOs remain assistive, supplementing Chinese officials’ expertise when called upon, while formulation and implementation remain controlled by government officials.

Thus, our findings do not contradict the overall trend of suppression of Chinese civil society in the environmental field (Gao & Teets, Citation2021; Li & Shapiro, Citation2020). Rather, we suggest that modes of expert input into environmental policymaking are becoming more refined: they are expanding to incorporate more non-governmental actors, while ensuring that expansion remains highly selective. Further research should focus on this process of refining non-governmental input under authoritarian regimes. The background of those ENGOs that are highly involved with C-ETS also requires further investigation. Participation of ENGOs, in terms of modes, media engagement, independence, and the impact on policy effectiveness, is a ripe avenue for future debates concerning environmental governance in China.

5.3. Strategic transparency under authoritarian governance

Transparency – in the form of information disclosure – is a clear feature of the C-ETS. Since 2021, MEE has published several announcements and regulations standardizing the form and responsibility of emission information disclosure from corporations and provincial governments alike (MEE, Citation2021b, Citation2021c, Citation2021d, Citation2022a) and ENGOs have assisted – with varying success – in realizing this information disclosure in practice. Although there is still significant progress to be made, our interviews suggest that as the Chinese government puts more emphasis on emissions reduction and as the C-ETS matures, Chinese officials will have higher requirements for C-ETS disclosure and efficiency. Current disclosure levels, however, are relatively low compared to more mature carbon markets, likely due to both the early stage of the C-ETS and the influence of China’s authoritarian governance features.

Our findings also reveal the strategic nature of information disclosure in the C-ETS. Transparency in the C-ETS – as required in central government policies, even if not uniformly practiced at the provincial level – is not a desired feature in and of itself, as might be the case for other ETSs instituted in liberal democratic settings. Rather, transparency is deployed strategically, in the service of improving efficiency and more swiftly meeting China’s carbon emission reductions goals. As with other authoritarian regimes, this indicates that output legitimacy (i.e. legitimacy derived from meeting stated goals) takes precedence over input legitimacy (i.e. legitimacy derived from how stated goals are met). The goal of reducing emissions is more important than any procedural justice concerns regarding transparency and public participation. Thus, our findings indicate that while authoritarian environmentalism can indeed be transparent, it operates with different priorities as compared to governance in liberal settings. Which approach is best for the effective functioning of carbon markets remains to be seen.

6. Conclusion

Market governance is no longer strictly associated with liberal democratic regimes. The world’s largest carbon market is now the C-ETS, a market established by a regime that many consider to be a prime example of authoritarian environmentalism. As more illiberal regimes embrace market governance to meet their carbon objectives, attention must be paid to how market and authoritarian features intermingle under the broader agenda of environmental reform. How do liberal ideals such as transparency and information disclosure coexist with authoritarian governance features and with what impact for meeting environmental targets? This study reveals the intermixing of market and authoritarian governance features through the example of ‘eco-elite’ participation and strategic transparency in China’s carbon markets.

We identify five key findings. First, we found that the central government, which is responsible for policy formulation and general guidance, is more open and proactive in disclosing C-ETS information than would be expected under the strict definition of environmental authoritarianism. Second, we also found marked discrepancy in the performance of different provincial environmental departments tasked with implementing the centrally determined C-ETS disclosure policies. Some provincial governments complete information disclosure proactively in advance, whereas some remain undisclosed despite the mandate. Third, we observed that public access to the disclosed information (via either official websites or social media) is in theory possible but remains limited due to practical difficulties of accessing and finding the information. Fourth, we found that the carbon emitting entities under regulation lack interest and sometimes the ability to execute information disclosure. These entities prefer the consultancy of third-party agencies, which vary in quality. Lastly, we found that ENGOs have a substantial presence in the C-ETS and its information disclosure, participating in policy research and advising, as well as assisting with information disclosing and communication.

These key findings indicate that transparency via information disclosure, although a notable feature of the C-ETS, is implemented through approaches and techniques that may differ from the norms associated with liberal governance. Chinese officials have sought strategic input from key environmental actors associated with international and domestic civil society. Yet, their input is not pursued as a public good valuable for its own sake. Instead, non-governmental consultation is sought strategically as a means to the larger goal of efficient market functioning. The same is true for government policies stipulating transparency via information disclosure. Transparency is not pursued for its own sake but is seen (at least in a limited sense) as a necessary component of developing efficient markets. Overall, China’s experiments with market-based governance via the C-ETS suggests that the country’s environmental governance model, not simply authoritarian, represents an evolving mixture of liberal and illiberal tactics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, Measurement, Reporting and Verification as the whole name of the MRV system is used, to align with the UNFCCC definition, instead of Monitoring, Reporting and Verification used by some literature or the direct translation of the MRV system in Chinese.

References

- Acheampong, A., Opoku, E. E. O., & Janet Dzator, J. (2022). Does democracy really improve environmental quality? Empirical contribution to the environmental politics debate. Energy Economics, 109, 105942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105942

- Ali, S., Wu, Z., Ali, Z., Muhammad, U., & Yu, Z. (2022). Does financial transparency substitute corporate governance to improve stock liquidity? Evidence from emerging market of Pakistan. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1003081

- Ball, C. (2009). What Is transparency? Public Integrity, 11(4), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922110400

- Beeson, M. (2010). The coming of environmental authoritarianism. Environmental Politics, 19(2), 276–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010903576918

- Beeson, M. (2018). Coming to terms with the authoritarian alternative: The implications and motivations of China’s environmental policies. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 5(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.217

- Bhimavarapu, V. M., Rastogi, S., & Abraham, R. (2022). The influence of transparency and disclosure on the valuation of banks in India: The moderating effect of environmental, social, and governance variables. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15, 612–629. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15120612

- Biebricher, T. (2020). Neoliberalism and authoritarianism. Global Perspectives, 1(1), 11872. https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.11872

- Böhmelt, T. (2014). Political opportunity structures in dictatorships? Explaining ENGO existence in autocratic regimes. The Journal of Environment & Development, 23(4), 446–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496514536396

- Buitenzorgy, M., & Mol, P. J. A. (2011). Does democracy lead to a better environment? Deforestation and the democratic transition peak. Environmental and Resource Economics, 48(1), 446–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-010-9397-y

- Centre for Energy and Environmental Policy Studies, Beijing Institute of Technology. (2022). Forecasting and prospects on Chinese carbon market (CEEP-BIT-2022-006). https://ceep.bit.edu.cn/docs/2022-01/eb3a1bf65b6e499281122c9d55ef2f7d.pdf

- Chen, K.-W. (2019). Variety of authoritarian environmentalism: The case of water management in Singapore, China, and Vietnam. American Association for Chinese Studies, 24. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Varietyof-Authoritarian-Environmentalism%3A-The-Case-Chen/69721a9cf3e211e35190c8ec1afd49147f619287.

- Ciplet, D., Adams, K. M., Weikmans, R., & Roberts, J. T. (2018). The transformative capability of transparency in global environmental governance. Global Environmental Politics, 18(3), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00472

- Eckersley, R. (2019). Ecological democracy and the rise and decline of liberal democracy: Looking back, looking forward. Environmental Politics. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108009644016.2019.1594536

- Escher, R., & Walter-Rogg, M. (2020). Disentangling the effect of the regime type on environmental performance. In: Environmental performance in democracies and autocracies. Palgrave Pivot. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38054-0_2

- European Environment Agency. (2022, August 23). EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) data viewer—European Environment Agency [Dashboard (Tableau)]. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/dashboards/emissions-trading-viewer-1

- Fredriksson, P., Neumayer, E., Damania, R., & Gates, S. (2005). Environmentalism, democracy, and pollution control. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 49(2), 343–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2004.04.004

- Froissart, C. (2019). From outsiders to insiders: The rise of China ENGOs as new experts in the law-making process and the building of a technocratic representation. Journal of Chinese Governance, 4(3), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2019.1638686

- Fujian Provincial Development and Reform Commission. (2016, May). Notice of Fujian Provincial People’s Government on the Issuance of the Implementation Plan for the Construction of Carbon Emission Trading Market in Fujian Province. https://fgw.fujian.gov.cn/zfxxgkzl/zfxxgkml/bwgfxwj/201612/t20161207_820333.htm. (in Chinese)

- Fuks, N., & Kabanov, Y. (2020). The impact of open government on the quality of governance: Empirical analysis. In A. Chugunov, I. Khodachek, Y. Misnikov, & D. Trutnev (Eds.), Electronic governance and open society: Challenges in eurasia (pp. 116–124). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39296-3_9

- Gao, Q. (2019). From Environmental Authoritarianism to Particpatory Governance—The Change of Climate Policy in China [Nanjin University]. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201902&filename=1019116011.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=4Mcy6GRIoDLshld86cLEHe0DP_t3Rbe2_6LwwmrnXIjp3uAW4Tb1jPlU68vs846N

- Gao, X., & Teets, J. (2021). Civil society organizations in China: Navigating the local government for more inclusive environmental governance. China Information, 35(4), 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X20908118

- Gilley, B. (2012). Authoritarian environmentalism and China’s response to climate change. Environmental Politics, 21(2), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.651904

- Guangdong Ecological and Environmental Department. (2022). Announcement on the completion and disposal of carbon emission allowances for key emission units included in the first compliance cycle of the national carbon market in Guangdong Province. https://gdee.gd.gov.cn/bhcyc/content/post_3883111.html. (in Chinese)

- Gupta, A., & Mason, M. (2016). Disclosing or obscuring? The politics of transparency in global climate governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 18, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.11.004

- Hall, E. (2015). Bernard williams and the basic legitimation demand: A defence. Political Studies, 63(2), 466–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12070

- Han, A., Lee, K., & Park, J. (2022). The impact of price transparency and competition on hospital costs: A research on all-payer claims databases. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1321. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08711-x

- Harrison, T. M., Guerrero, S., Burke, G. B., Cook, M., Cresswell, A., Helbig, N., Hrdinova, J., & Pardo, T. (2012). Open government and e-government: Democratic challenges from a public value perspective. Information Polity, 17(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-2012-0269

- He, B., & Warren, M. E. (2011). Authoritarian deliberation: The deliberative turn in Chinese political development. Perspectives on Politics, 9(2), 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711000892

- Heilbroner, R. L. (1974). An inquiry into the human prospect. Norton.

- Hsu, A., de Sherbinin, A., & Shi, H. (2012). Seeking truth from facts: The challenge of environmental indicator development in China. Environmental Development, 3, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2012.05.001

- ICAP. (2023). Emissions Trading Worldwide: 2023 ICAP Status Report. International Carbon Action Parnership. https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/publications/emissions-trading-worldwide-2023-icap-status-report

- Information Office of the State Council. (2021). White Paper on China’s Policies and Actions to Address Climate Change. China State Council. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/27/content_5646697.htm. (in Chinese)

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I., Groff, M., Tamás, P. A., Dahl, A. L., Harder, M., & Hassall, G. (2018). Entry into force and then? The Paris agreement and state accountability. Climate Policy, 18(5), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1331904

- Kaya, A., & Liu, Q. (2015). Transparency and price formation. Theoretical Economics, 10(2), 341–383. https://doi.org/10.3982/TE1566

- Kostka, G., & Mol, A. P. (2013). Implementation and participation in China’s local environmental politics: Challenges and innovations. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2013.763629

- Kwon, K. L., & Hanlon, R. J. (2016). A comparative review for understanding elite interest and climate change policy in China. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(4), 1177–1193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9696-0

- Li. (2018). Can climate change work continue to go strong after institutional restructuring? Dialogue Earth. https://dialogue.earth/en/climate/10599-china-s-new-environment-ministry-unveiled-with-huge-staff-boost/

- Li, Y., & Shapiro, J. (2020). China Goes Green: Coercive Environmentalism for a Troubled Planet. In China Goes Green: Coercive Environmentalism for a Troubled Planet. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348826548_Review_of_Li_and_Shapiro_2020_China_goes_Green_coercive_environmentalism_for_a_troubled_planet

- Li, X., Yang, X., Wei, Q., & Zhang, B. (2019). Authoritarian environmentalism and environmental policy implementation in China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 145, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.02.011

- Lin, H. (2018). Constructing legitimacy: How Do Chinese NGOs become legitimate participants in environmental governance? The case of environmental protection Law revision. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 5(6). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-018-0076-7

- Lindvall, D., & Karlsson, M. (2024). Exploring the democracy-climate nexus: A review of correlations between democracy and climate policy performance. Climate Policy, 24(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2256697

- Lo, K. (2015). How authoritarian is the environmental governance of China? Environmental Science & Policy, 54, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.06.001

- Lo, K. (2021). Authoritarian environmentalism, just transition, and the tension between environmental protection and social justice in China’s forestry reform. Forest Policy and Economics, 131, 102574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102574

- Lourenço, R. P., Piotrowski, S., & Ingrams, A. (2015). Public accountability ICT support: A detailed account of public accountability process and tasks. In E. Tambouris, M. Janssen, H. J. Scholl, M. A. Wimmer, K. Tarabanis, M. Gascó, B. Klievink, I. Lindgren, & P. Parycek (Eds.), Electronic government (pp. 105–117). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22479-4_8

- Lv, Z. (2017). The effect of democracy on CO2 emissions in emerging countries: Does the level of income matter?, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 72, 900–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.096

- Mehrpouya, A., & Salles-Djelic, M. (2019). Seeing like the market; exploring the mutual rise of transparency and accounting in transnational economic and market governance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 76, 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2019.01.003

- Milanés Montero, P., Pérez Calderón, E., & Lourenço Dias, A. I. (2020). Transparency of financial reporting on greenhouse Gas emission allowances: The influence of regulation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030893

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2021a). Guidelines for verification of enterprises GHG Emission Reports (Trial). https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk06/202103/W020210329546745446406.pdf. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2021b, February). Measures for the administration of carbon emission trading (Trial). http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-01/07/content_5577582.htm. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2021c, March). Guidelines for enterprises greenhouse gas verification (Trial). https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk06/202103/t20210329_826480.html. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2021d, May). Notice on the publication arrangement of the ministry of ecology and Environment in 2021. http://www.laixi.gov.cn/n1/n5798/n5801/n6905/n6906/n6915/210720161243457341.html. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2021e, March). Interim regulations on the administration of carbon emissions trading (Draft). https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk06/202103/W020210330371577301435.pdf. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2022a). Guidelines for verification methodology and reporting of entity GHG emissions (Power Generation Facilities). https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/201311/W020190905508183676844.pdf. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2022b, January 21). Implementation Plan for the second compliance period of national carbon emission trading allowance setting and allocation. http://www.tanpaifang.com/tanjiaoyi/2022/0121/81973.html. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2022c, March 14). The Ministry of Ecology and Environment discloses typical cases of carbon emission reporting data falsification and other typical problems by China Carbon Energy Investment and other institutions (First batch of outstanding environmental problems in 2022). https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/ydqhbh/wsqtkz/202203/t20220314_971398.shtml. (in Chinese)

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. (2022d, June). Notice on the efficient integration of epidemic prevention and control and economic and social development adjustment of key tasks related to the management of corporate greenhouse gas emissions reporting in 2022. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-06/12/content_5695325.htm. (in Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission. (2022, April 22). Notice on “Implementation Plan for Accelerating the Establishment of a Uniform and Standardized Carbon Emission Statistics and Accounting System.” https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/tzgg/202208/t20220819_1333233.html?code=&state=123. (in Chinese)

- Ong, A. (2006). Neoliberalism as exception: Mutations in citizenship and sovereignty. Duke University Press.

- Ong, A. (2007). Neoliberalism as a mobile technology. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 32(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00234.x

- Pickering, J., Bäckstrand, K., & Schlosberg, D. (2020). Between environmental and ecological democracy: Theory and practice at the democracy-environment nexus. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1703276

- Povitkina, M. (2018). The limits of democracy in tackling climate change. Environmental Politics, 27(3), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1444723

- Qinyue Environment. (2022, January 2). National carbon trading launched, only 1/4 of provinces fully disclose list of key GHG emitters. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_16093396. (in Chinese)

- Ran, R. (2015). Local environmental politics in China: The distance between policy and implementation. Central Com[ilation & Translation Press.

- Rooij, B. van Stern, R. E., & Fürst, K. (2016). The authoritarian logic of regulatory pluralism: Understanding China’s new environmental actors. Regulation & Governance, 10(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12074

- Scharpf, F. W. (2003). Problem-solving effectiveness and democratic accountability in the EU, MPIfG working paper, No. 03/1.

- Schreifels, J. J., Fu, Y., & Wilson, E. J. (2012). Sulfur dioxide control in China: Policy evolution during the 10th and 11th five-year plans and lessons for the future. Energy Policy, 48, 779–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.06.015

- Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange. (2021, June 22). Announcement on Matters Relating to National Carbon Emissions Trading. https://www.cneeex.com/c/2021-06-22/491198.shtml. (in Chinese)

- Shearman, D., & Smith, J. (2007). The Climate Change Challenge and the Failure of Democracy.

- Sheih, S. (2018). The Chinese state and overseas NGOs: From regulatory ambiguity to the overseas NGO Law. Nonprofit Policy Forum, 9(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2017-0034

- Shen, D., Xia, M., Zhang, Q., Elahi, E., Zhou, Y., & Zhang, H. (2019). The impact of public appeals on the performance of environmental governance in China: A perspective of provincial panel data. Journal of Cleaner Production, 231, 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.089

- State of Council. (2019). Regulations of the People's Republic of China on Government Information Disclosure. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-04/15/content_5382991.htm. (in Chinese)

- Suk, S., Lee, S., & Jeong, Y. S. (2018). The Korean emissions trading scheme: Business perspectives on the early years of operations. Climate Policy, 18(6), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1346499

- Tian, X.-L., Guo, Q.-G., Han, C., & Ahmad, N. (2016). Different extent of environmental information disclosure across Chinese cities: Contributing factors and correlation with local pollution. Global Environmental Change, 39, 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.014

- Wang, W., He, S., & Liu, J. (2023). Understanding environmental governance in China through the green shield action campaign. Journal of Contemporary China. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2023.2244893

- Wang, H., & Jiang, C. (2020). Local nuances of authoritarian environmentalism: A legislative study on household solid waste sorting in China. Sustainability, 12(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062522

- Weikmans, R., Van Asselt, H., & Roberts, J. T. (2020). Transparency requirements under the Paris agreement and their (un)likely impact on strengthening the ambition of nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Climate Policy, 20(4), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1695571

- Weller, R. (2008). Regime responses. Responsive authoritarianism. In Political change in China: Comparisons with Taiwan (pp. 117–138). Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder. https://cddrl.fsi.stanford.edu/publications/political_change_in_china_comparisons_with_taiwan

- Wu, J., Chang, I.-S., Yilihamu, Q., & Zhou, Y. (2017). Study on the practice of public participation in environmental impact assessment by environmental non-governmental organizations in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 74, 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.178

- Wu, X., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2015). Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy and Society, 34(3-4), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001

- Xu, P. (2021, September 23). A lesson in the first case of data falsification in the national carbon market. https://finance.sina.cn/china/gncj/2021-09-23/detail-iktzscyx5928216.d.html?from=wap

- Yu, H., & Robinson, D. G. (2012). The New ambiguity of 'Open government'. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2012489

- Zhang, L., Mol, A. P., & He, G. (2016). Transparency and information disclosure in China’s environmental governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 18, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.03.009

- Zhang, L., Mol, A. P. J., He, G., & Lu, Y. (2010). An implementation assessment of China’s environmental information disclosure decree. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 22(10), 1649–1656. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-0742(09)60302-8

- Zhao, X., Jiang, G., Nie, D., & Chen, H. (2016). How to improve the market efficiency of carbon trading: A perspective of China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 59, 1229–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.01.052

- Zhou, J., Huo, X., Jin, B., & Yu, X. (2019). The efficiency of carbon trading market in China: Evidence from variance ratio tests. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(14), 14362–14372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04778-y

- Zhu, J., Ge, Z., Wang, J., Li, X., & Wang, C. (2022). Evaluating regional carbon emissions trading in China: Effects, pathways, co-benefits, spillovers, and prospects. Climate Policy, 22(7), 918–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2054765

Appendices

Appendix 1 Interviewee List

Appendix 2 C-ETS policy documents analyzed

Appendix 3 Comparative Table regarding C-ETS and EU ETS

Appendix 4 C-ETS Disclosure Procedures

Three regulations define the procedure to conduct C-ETS information disclosure. Measures for the Administration of Carbon Emission Trading (Trial) stipulates that MEE and the Department of Ecology and Environment (DEE) need to routinely disclose compliance and violations information (Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Citation2021b). It also stipulates that registry and trading agencies publish information on the registration, trading and settlement of allowance in a timely fashion and entities and other trading bodies should also make C-ETS relevant information available for public supervision. Guidelines for Enterprises Greenhouse Gas Verification (Trial) addresses the requirement of information disclosure completed by the DEE, with details on the official materials list to be filled (Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Citation2021a). Lastly, Guidelines for Verification Methodology and Reporting of Entity Greenhouse Gas Emissions (Power Generation Facilities) reaffirms the disclosure requirement completed by the key emission entity, which lists the information an entity needs to complete and disclose (Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Citation2022a).

All the C-ETS relevant regulations are at a relatively low legislation level. There are several levels in the current Chinese legislative hierarchy, with Regulation, Measure, Rule and Guidelines in descending order. Most of the C-ETS regulations are Rules and two are Measures. Low legislation level means that C-ETS rules do not pass through the legislature and only apply as a department regulation. In C-ETS, low legislature also implies the low penalty and low cost of non-compliance, as well as being less mandatory. However, in practice, entities who fit the entrance threshold must join. The cost of non-compliance is relatively low, but the penalty for repeated non-compliance and data falsification can be huge. In addition, after the reveal of MRV data quality issues, which is that four entities were found to falsify the emission data, the central government aimed to publish more and higher legislature. MEE has issued a draft for higher legislation on C-ETS with higher punishment (MEE, Citation2021e), and several private workshops with experts from MEE have confirmed this as well.

Meanwhile, the central government encourages local governments to develop policies that are more stringent than the national requirements (A2 and A3). In practice, provinces with pilot ETS experience might formulate more detailed rules. For example, Fujian province published Measures for the Administration of Third-Party Verification Agencies for Carbon Emission Trading in Fujian (Trial) (Fujian Provincial Development and Reform Commission, Citation2016), which is similar to the legislation that the central government is trying to accelerate after the reveal of MRV data quality issues (C2, E1 and V2). However, most provincial governments still rely on central government regulations and guidance as the reference.

After the outbreak of data falsification, MEE acted quickly. Not only did they punished the involved companies by public reporting and fines, but they also adopted measures such as ‘state-provincial-city’ joint review mechanism to improve data quality. No similar case has emerged since, hence no other public reporting. Companies involved paid the fines (10,000 −30,000 Yuan) and some even stopped related carbon businesses. Moreover, MEE already indicated in a regulation draft that they will enhance the level of penalties to between 50,000 and 200,000 Yuan.