ABSTRACT

Translation studies have shown that management ideas and practices change as they travel between contexts, and that there are regularities in how they are translated through editing. We, however, know less about what facilitates good translations, i.e. the translation of new ideas and practices into working practices or routines that contribute to the attainment of organizational goals. This study investigates how the concept of readiness for change can increase our understanding of translation processes and translation outcomes through following an intra-organizational translation of a new management idea and practice in a hospital. The aim is to identify how the use of editing rules in a strategic translation process impacts readiness for change. It is also to identify how readiness influences the use of editing rules and translation practices in an operative translation process and the resulting differences in the quality of translation outcomes. This study finds that strategic translations may foster readiness for change. Readiness furthermore enables inclusive operative translation processes in which editing practices and translation rules are used to thoroughly rework a new management idea and practice into a good translation.

MAD statement

Management ideas and practices change as they travel to new organizational settings – they are translated. Not all translation outcomes contribute to the attainment of organizational goals. This paper argues that readiness for change is a key concept in understanding translation processes and the quality of translation outcomes. Change initiators may foster readiness for change among operative level employees through strategic translations. When readiness is high, a further operative translation process including a wide range of participants as translators may thoroughly rework the new idea and practice into new, constructive work practices that enable the organization to attain important goals.

Introduction

This paper presents a case study of the process of translating a new management idea and practice in a hospital setting. The focus is on the facilitation of translation outcomes that contribute to the realization of organizational goals. Scandinavian institutionalism has contributed valuable knowledge on how management ideas and practices travel and are translated into new geographical locations, organizational fields and between organizations (Boxenbaum & Pedersen, Citation2009; Wedlin et al., Citation2017). This work describes how ideas and practices are dis-embedded from their source context so that they can travel and be re-embedded in a new one, the object inevitably changing through this travelling process (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996; Czarniawska-Joerges & Sevón, Citation2005). Empirical research has identified that translation takes place in accordance with translation or editing rules and practices (Kirkpatrick, Bullinger, Lega, & Dent, Citation2013; Morris & Lancaster, Citation2006; Røvik, Citation2016; Sahlin-Andersson, Citation1996; Teulier & Rouleau, Citation2013; Wæraas & Sataøen, Citation2014). In other words, we know that ideas and practices change as they travel, and we know something about how they are changed by translation. We, however, know less about what facilitates good translations, i.e. the translation of new ideas and practices into working practices or routines that can contribute to the attainment of organizational goals (Røvik, Citation2011, Citation2016; Wæraas & Nielsen, Citation2016).

This underexplored issue is relevant not just because it represents a gap in the translation literature. It is also of great relevance to managerial practice, particularly in publicly funded health care organizations. Organizational change, such as introducing new management ideas and practices, requires financial input, time and personnel. The failure to turn such efforts into organizational practices that contribute to organizational goals, therefore, represents a waste of resources. These resources could have been used in more productive ways. Failed change efforts may also be a source of discontent, increased distrust in the relationships between management and professionals, and a source of potential future resistance to new initiatives (Arnetz, Citation2001). Research that extends the knowledge and understanding of what facilitates good translations is therefore needed.

This study follows the introduction of an ICT-supported task planning system for hospital physicians. The study analyses this process as an intra-organizational translation of a management idea and practice. The source context is a regional HR department and the recipient contexts are three hospital departments. Four state-owned corporations, Regional Health Authorities (RHAs), in Norway supervise all public hospitals. This supervision is carried out in accordance with the aims and priorities set by the Ministry of Health. Implementing the new advanced task planning (ATP) system was part of a change programme initiated by an RHA HR department. The programme was initiated to reach the strategic goals of providing high quality and timely patient pathways within mandated maximum waiting time guarantees. Hospitals are complex organizations and their operation is guided by more than one institutional logic (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, Citation2011; Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, Citation2012). Despite decades of managerial logic initiatives hospitals, and particularly the work of physicians, are still heavily influenced by a professional logic (Andersson & Liff, Citation2018; Currie, Lockett, Finn, Martin, & Waring, Citation2012; Heldal, Citation2015; Reay & Hinings, Citation2009). Physicians are often able to resist change initiatives imposed by other actors. Translating managerial ideas into practices that become part of the daily work routines of professionals and that contribute to the achievement of organizational goals is, in such a context, challenging. The differing institutional logics represent a distance across which an idea has to travel (Lillrank, Citation1995). The often conflictual relationship between logics, however, means that the idea may be actively resisted. The ATP project and its translation within the hospital organization is therefore an interesting setting for uncovering factors that can contribute to good translations.

This study contributes to the underexplored issue of what facilitates good translations in two ways. First, translation is a continuous editing process that involves different actors, as ideas and practices move from setting to setting (Sahlin-Andersson, Citation1996). Radaelli and Sitton-Kent (Citation2016) identified a need for studies that focus on the translation practices of organizational actors other than the most commonly studied executive managers and R&D departments. Our case study follows the translation of ATP from the managerial logic setting of a regional HR department to the professional logic settings of three different hospital departments. We first investigate the translation effort of the RHA HR director who initiated the change project in the hospital departments. We conceptualize this as a strategic translation that is aimed at convincing organizational members of the merits of ATP. We further analyse the process of translating the ATP idea and practice into the departments’ work routines. We conceptualize this as an operative translation performed by managers and professional employees in each department. This segmenting of a translation process into two phases, a strategic and operative translation, each involving different organizational translation actors, is to the best of our knowledge a novel contribution to the literature.

Second, employee support for new management ideas and practices can be operationalized as readiness for change (Armenakis & Harris, Citation2002; Armenakis, Harris, & Mossholder, Citation1993; Holt, Armenakis, Harris, & Feild, Citation2007). Combining Scandinavian institutionalism's theoretical concepts of translation and editing rules and practices with the concept of readiness for change, gives a combination of perspectives that is new to the literature. Our aim is, through this new combination, to shed light on the role of readiness in facilitating good translations.

This paper provides a detailed empirical analysis of the impact of the editing practices used in the strategic translation upon department level readiness for ATP implementation, the impact of different levels of readiness on the use of editing rules and translation practices in the operative translation process, and differences in the planning practices that materialized in the three hospital departments.

Theoretical Background

Intra-organizational Translation Across Institutional Logics

Empirical implementation studies in health care settings have found that management ideas and practices travel to and are then translated into new versions in the health care organizational field, individual organizations and departments (Andersen & Røvik, Citation2015; Kirkpatrick et al., Citation2013; Nielsen, Mathiassen, & Newell, Citation2014; Spyridonidis & Currie, Citation2016; Wæraas & Sataøen, Citation2014; Waldorff, Citation2013). This is consistent with the foundational insights of translation theory (Czarniawska-Joerges & Sevón, Citation2005). Translation has been defined in this literature as being ‘the process in which ideas and models are adapted to local contexts as they travel across time and space’ (Lamb & Currie, Citation2012, p. 219). In other words, the way actors present, receive, negotiate, make arguments about and adapt a management idea or practice in local contexts is understood to be a translation process. The object of translation, that which is being adapted to a new context, can be more or less standardized management concepts in the form of recipes such as LEAN or TQM. The object may also be regulations, strategic ideas or new managerial practices (Radaelli & Sitton-Kent, Citation2016). ATP is not a pre-existing management recipe such as LEAN. It was, however, a new management idea and practice. It can therefore be studied as an object of translation.

Most empirical translation studies have focused on travel between geographical locations such as countries or regions, or across organizational fields or organizations. Andersen & Røvik's study of the translation of LEAN in a hospital (Citation2015) is an exception. They found different translations of a concept within an organization. This study zooms in on such an intra-organizational process. We analyse the translation of ATP, a specific idea and practice that was developed within the organization. Even so, it needed to travel from an RHA department to clinical frontline hospital departments and was transformed along the way. There has been little exploration within Scandinavian institutionalist translation studies of how actors within organizations carry and translate management knowledge across boundaries (Wæraas & Nielsen, Citation2016). In our study, we conceptualize boundaries between parts of the organization as being not just structural, but as also representing difference in the dominant institutional logic of the source and recipient contexts.

Institutional logics are central to our understanding of the context within which the translation of ATP takes place. The differing institutional logics of the source and recipient contexts mean that there is a distance across which idea and practice has to travel (Lillrank, Citation1995). This is despite source and recipient contexts being located within the same organizational structure. The institutional logic perspective analyses how organizations and individuals are affected by the institutional environment. This perspective, as developed by Thornton and colleagues (Citation2012), sees individuals as not being ‘mindless’ actors who simply go along with whatever the environment around them demands. This is in contrast to earlier neo-institutional theory and to the original conceptualization of institutional logics by Friedland and Alford (Citation1991), in which structure is more clearly emphasized over agency. Institutional logics, as defined by Thornton and colleagues, ‘shape rational, mindful behaviour’ (Citation2008, p. 100). This perspective also allows for an analysis of how multiple logics can co-exist within organizations, and of how different actors within an organization may be guided by different sets of assumptions, values, beliefs and taken-for-granted rules (Thornton et al., Citation2012).

Research on institutional logic in the health care field often focuses on the relationship between the medical professional logic and the managerial logic (Andersson & Liff, Citation2018). The professional logic highlights the autonomy and trust-based authority of professionals such as physicians in clinical and organizational issues (Andersson & Liff, Citation2018; Freidson, Citation2001; Martin, Currie, Weaver, Finn, & McDonald, Citation2017; Noordegraaf, Citation2015; Reay & Hinings, Citation2005). New Public Management inspired policies have, however, increasingly challenged the organizing principles of this logic in decisions relating to hospital organizational models and management systems (Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2002). The managerial logic, which is inspired by the private sector and emphasizes stronger, more efficient, business-like and hierarchical management and clear accountabilities, has gained influence in health care systems internationally (Ackroyd, Kirkpatrick, & Walker, Citation2007; Arman, Liff, & Wikström, Citation2014; Byrkjeflot & Kragh Jespersen, Citation2014). The relationship between co-existing logics in fields or organizations has, however, often been described as conflictual or competitive (Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006; Reay & Hinings, Citation2005). This co-existence of conflicting logics matters at the level of organizational actors. High-level management actors are often guided by a logic which is at odds with the logic guiding actors at the operative level. Actors at the operative level are also able to resist initiatives coming from higher-level management. This context is therefore particularly challenging when initiating and implementing new management ideas and practices.

Readiness for Change

We believe, based on this, that our context is particularly relevant to understanding the role played by readiness for change in facilitating good translations. Readiness is the cognitive precursor of either resisting an organizational change effort, or accepting, embracing and adopting it (Armenakis et al., Citation1993; Holt, Armenakis, Feild, & Harris, Citation2007). Failing to gain the support of those who are to use a new idea such as ATP, risks it never materializing into a practice that could contribute to the attainment of organizational goals – i.e. a good translation.

Readiness, in a broad sense, seems to be an important success factor in the implementation of change (Jones, Jimmieson, & Griffiths, Citation2005). It is most commonly studied as an individual factor. This study is concerned with readiness at the department level and assumes that the change beliefs of individuals may become shared in such groups as a result of social interaction processes (Rafferty, Jimmieson, & Armenakis, Citation2013). Readiness consists of five key change beliefs (Armenakis & Harris, Citation2002). Discrepancy refers to the belief that there is a gap between the current state and the state that should exist. Believing in the appropriateness of the suggested change means believing that a specific change that is designed to address a discrepancy, is correct for that particular situation. Believing in efficacy means that the change recipients believe they and the organization can successfully implement a change. Believing in principal support means trusting that both formal leaders (vertical change agents) and horizontal change agents (opinion leaders) are committed to the change. Believing in valence means believing that the change is beneficial to the change recipients themselves.

Editing and Translation Practices and Rules

We employ the concepts of editing rules and practices (Sahlin-Andersson, Citation1996; Teulier & Rouleau, Citation2013) and translation rules (Røvik, Citation2016) to study the details of both the strategic and operative translation processes. Sahlin-Andersson (Citation1996) studied the translation of abstract organizational concepts into practice in new settings and found that there are regularities in how actors perform translations. She coined the concepts of translating actors as editors and regularities as editing rules. She identified that there are rules that concern context, formulation and logic. Contextual rules describe that a concept must be dis-embedded from a source context before it can travel to and be re-embedded in a new one. Rules of formulation describe the way concepts are labelled and how their story is told, often in dramatized ways. Rules concerning logic describe how new ideas and practices are presented according to a certain plot that adheres to a rationalistic logic of causes (the new idea or practice) and effects (positive results).

Teulier and Rouleau (Citation2013) expanded on this framework of contextual, formulation and logic rules by identifying a set of editing practices that translators use. They found that middle managers performed translation in a number of translation spaces, using a number of editing practices. Middle managers de-contextualized the technology by reframing problems and staging their discussions, worked on formulation by readjusting the vision of and by rationalizing the change, worked out issues of logic by stabilizing their shared understanding of the new technology and took absent stakeholders into account. Teulier and Rouleau further argue for the existence of a fourth set of rules that are in addition to Sahlin's three categories. These rules specifically describe the re-embedding of a new idea and include the editing practices of speaking for the technology and selling the change.

We use these editing practices in our study as analytic tools for identifying how different actors (the regional HR director, department-level managers and employees) strategically and operatively translated ATP into new practices. We understand these editing practices to mainly concern how a change is discursively constructed and communicated. We also utilize the translation rules identified by Røvik (Citation2016) to uncover how the content of the ATP practice changes through operative translation. He argues that a translation process can reproduce management practices through elements being simply copied, or modify practices through elements being added or omitted.

Røvik (Citation2007) has also called for research that focuses on his distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ translations. New, translated versions of a management idea and practice can contribute more or less positively to organizational performance. However, little research has been carried out on translation quality and effectiveness within Scandinavian institutionalism (Wæraas & Nielsen, Citation2016). Our study contributes to this identified need for more research by analysing the relationship between the use of editing practices and translation rules by multiple organizational actors in strategic and operative translation processes, and translation outcomes that represent better or worse versions of an initially identical idea and practice. Our study also investigates the role of readiness for change in this process. We specify the research aim of increasing our knowledge of what facilitates good translations by asking:

– How are the editing practices employed in the strategic translation of ATP related to department level readiness for change?

– How are differences in department-level readiness for change related to the use of editing practices and translation rules in operative translations?

– How are the different constellations of editing practices and translation rules used in the departments related to the quality of the operative translation outcomes?

Method

Research Setting

The role of the new, advanced task planning system was to assign detailed tasks to specific individual physicians and to replace a system that to a great extent only planned for their presence or absence at work. The new system was to also allow the period of time of advance detailed planning to be extended. Plans were to be moved from a wide range of ICT or paper-based tools into GAT, which is an ICT application for HR management. The planning module within this ICT application was developed specifically for the ATP project by the RHA in collaboration with the ICT system provider. This ICT application was, finally and importantly, to be integrated with other relevant ICT tools so that a more holistic overview of tasks and plans could be achieved, both in the long-term view and after day-to-day changes to plans were made. Hospital task planning had previously been carried out using multiple and separate ICT applications. The existing planning system was not well suited to distributing information across professional and departmental boundaries. Nor was it well-suited to handling changes to long- and short-term plans. This created problems for the delivery of services and limited the possibility for an optimal match between available resources, competencies and tasks. Programme strategic goals and sub-project content are presented in .

Table 1. The Turn Up programme – goals and relevant sub-project.

Research Design and Data Collection

We compare the programme introduction and the translation process in three departments as three qualitative and longitudinal cases (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). Cases were theoretically sampled from a larger study of the programme at the regional level. One department was a pilot department in the earliest stages of the task planning sub-project and was followed by researchers at several points in time over two years. The two other departments were early adopters and were followed over a period of 6–12 months. The cases were chosen because the success of the change process, in terms of its transformation of the way physician's work was planned, differed between the departments.

We gained access due to being commissioned to carry out a study that trailed the programme in all the RHA hospitals. The research was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Data was collected between October 2013 and September 2016, using 31 semi-structured interviews with participants at regional, hospital, and department levels. Data was also collected through direct, non-participant observation of meetings (each lasting between 1 and 1.5 h) in two of the three case departments (see ). Interview guides were adjusted to elicit relevant data from each individual participant. All, however, centred on two main themes – details on what was being done, by who, in the practical process of implementing ATP, and questions related specifically to the five change beliefs. Participants were asked to elaborate on their own change beliefs, and to share their experience of how others in the departments were interpreting ATP. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Field notes were taken during the meetings and written out directly following observations. Both types of data were subjected to the analysis described below.

Table 2. Interviews and observations.

Interview participants signed consent forms, and meeting participants were informed about the observing researcher and the research intent. Participants at the regional and hospital levels identified participants in the departments. These participants furthermore advised us of who else we could interview. Observing meetings also led us to identify other participants who stood out as relevant. The participants had different occupations, in both clinical and administrative departments, and were employed at different organizational levels. We observed meetings and/or conducted interviews at the outset of the change process in each department. We followed this up with interviews after the change process had been progressing for a while (6 months to 2 years). A facilitation team was interviewed about project progress and challenges several times during the process. This ensured that we obtained data for the overall change programme and for department-level processes at several points in time.

The uneven number of data points across the cases is a limitation. This reflects a more active change process in one department, and the difficulty of gaining access due to project implementation activities not being predictably planned ahead. Attempts were made to adjust this imbalance by obtaining information on the two less active departments from other sources, such as from the facilitation team. Another limitation was the documentation of individually held or group level change beliefs. It was possible to gain information, in some instances, on these in real time and as the process unfolded. However, in other instances, it was only possible to assemble an understanding of specific beliefs retrospectively, through data sources other than interviews or observations of the participants. We believe that the triangulation of data sources, even so, ensures the credibility of the findings related to change beliefs.

Data Analysis and Research Quality

A chronological narrative of the change process in each department was constructed from the raw data, to create a thick description of the process and its main issues (Langley, Citation1999; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). This analysis was useful in creating a chronology for further analysis and as a step in establishing early analytical themes (Langley, Citation1999; Pettigrew, Citation1990). The first author then analysed the data employing template analysis (King, Citation2012). The main themes in the template (such as change beliefs, editing practices and translation rules, changes to and quality of resulting planning practices) were selected from theory and iteratively developed. More fine-grained categories were developed inductively by going back and forth between data and theory. Readiness for change is often measured using quantitative survey instruments (Holt, Armenakis, Field, et al., Citation2007). We used qualitative interviews and template analysis of the interview data to establish department level readiness. We, for each department, coded all statements relevant to the five underlying change beliefs into categories consistent with these five beliefs, and compared the content of these statements across all three departments.

All template codes were coupled with negative evidence codes, so ensuring that potential disconfirming evidence of the emerging explanations was noticed. Credibility (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) was also strengthened by triangulation (several sources of data), prolonged engagement, persistent observation, the use of member checking, peer debriefing and constant comparison. Employing thick description, comparing findings to theory and using a replication logic between cases strengthens the transferability of the study. Dependability and confirmability were strengthened by maintaining a case database, an audit trail, by employing a rigorous and transparent research process, and remaining to the best of our ability reflexive about emerging findings throughout the process.

Findings

We, in this section, first present findings on the strategic translation of ATP and the editing practices employed by the regional HR manager. We then present our analysis of the level of readiness for change in each department and then present findings on the editing practices and translation rules employed by translators in each department to mould ATP into working practices. We finally evaluate how ‘good’ each of these new practices were, as defined by whether or not they contributed to the promotion of organizational goals.

Strategic Translation of ATP

The strategic translation of ATP was performed by the regional HR manager in her communication with hospital departments. This largely took place in the translation space of the project kick-off meetings she held with each department. The aim of the meetings was to convince department managers and staff members to get on board with the new way of managing task planning. We found that she, in this strategic translation process, employed several editing practices in communicating the ATP idea and practice to hospital staff.

The kick-off meetings in each department were used to stage the translation process. The meetings included the HR manager, department managers and staff, and a project facilitation team from the hospital resource department. The facilitation team would be responsible for guiding the departments through the subsequent process of implementing ATP. The team was competent in the existing planning methods in each department and in the idea and technicalities of the new system. Arrangements were also put in place to ensure that departments could rely on additional ICT personnel if required.

The HR manager reframed the problems that ATP would solve in her presentation of ATP in these meetings. She insisted that the benefits of implementation not only would be the achievement of organizational goals and more timely services to patients (shorter waiting lists, fewer treatment guarantee breeches). She also insisted that professional needs would be better served through the working situation becoming more predictable. She specifically highlighted the burden on medical and nursing staff of working in a chaotic situation. A lack of predictability meant that plans for physician competence building, leave of absence and even regular breaks during a workday often had to be abandoned. She identified with the very hectic workdays, always being behind schedule, not knowing what tasks they would be carrying out in the following week or day, not knowing where other staff members they needed to speak to were, not being able to predictably plan absence required for competence building or holidays, and not being able to maintain a sustainable work-life balance. She also explicitly refused to put the blame for long waiting lists on department staff members. She stated that she was aware of how hard they were working and that she did not expect the problems to be resolved by them working harder. This concern was not part of the official programme goals. But it was made explicit as a main selling point in the HR manager's contact with the recipients, as she attempted to bring them on board.

A similar reframing took place through an adjustment of the vision of the Turn Up change programme. The overall vision was for long waiting times and guarantee breaches to be eliminated. The benefits to those working at the hospitals were, however, highlighted as being equally important in the meetings with departments. There was, conversely, very little focus on the potential loss of physician autonomy in the planning of their work, and on the increased control and more detailed monitoring of how tasks such as patient appointments were planned by the regional HR department. This increase in control and monitoring was inherent to the idea and practice. The new ICT solution allowed for such monitoring, and data was collected and monitored in a data bank constructed by the regional HR department, this being a part of the Turn Up programme. These data were, however, rarely presented to recipients. There was less focus on this in the presentation to recipients of the ATP vision than on professional needs that would be met due to less chaos.

The needs of patients and of the general public the hospitals serve were also covered in her presentations. She therefore also employed the editing practice of taking absent stakeholders into account by communicating how the implementation of ATP would affect patients and their impression of and relationship with the hospital.

The HR manager also rationalized the change by linking the ATP solution to the failure to attain organizational goals and the chaotic situation for staff. She argued that better planning was key to improving these issues. She spoke for the technology by highlighting the potential for software integration, real-time communication of changes to plans, and by comparing ATP favourably with previous ICT solutions.

Readiness for Change

Discrepancy

The discrepancy communicated by the regional HR director was that the current treatment waiting times for patients were too long and that there were too many guarantee breeches. She also highlighted the burden upon staff caused by working in a chaotic situation and the low levels of predictability. The desired situation was defined as being one in which the strategic goals of cutting waiting times and zero guarantee breeches were realized, and in which the work situation for physicians and other staff was more stable, less stressful, and allowed needs such as attending courses and maintaining a sustainable work-life balance to be met.

This discrepancy was largely deemed to be legitimate and accurate by the informants in all departments. No one was happy with the current situation, nor with not being able to provide timely treatment. Physicians in some cases did not believe patients waiting was necessarily a medical problem. They all, however, felt the repercussions of breeching guarantees, as these are one of the most important targets on which department performance is measured.

Appropriateness

There was less agreement on the appropriateness of the intended intervention. The intention was that the intervention would solve the identified problems by planning work in a more detailed way and over a longer time frame, and by re-organizing work. The department heads and physicians of all three departments initially attributed the problems to insufficient numbers of qualified physicians.

All physician positions in Department 1 (Dep1) were filled. However, the department head had been trying for a long time to convince the hospital leadership that they needed more physician positions to carry out their tasks. The head had been arguing that this was the only solution to their problems throughout the two-year period of change implementation.

When we met with Dep1, they were (…) quite aggressive, “so – you think you are going to come here and save our operation using … ”, it was a little bit as if “you are not going to cut waiting times or make guarantee breeches disappear through advanced task planning. Do you, is this what you think?” What could they do with the resources they have to get more (patients) in? But Dep1 has not gone along with that reflection. (Process facilitation team leader.)

And those who think that we are going to solve all waiting list problems and guarantee breeches with this system are really mistaken. They are basing this on the assumption that the reason (for the problems) is that we have had poor control. I strongly oppose this. (…) it's just that we have a much greater burden than we are staffed to cope with. (…) So I don't think this will bring about a revolution. But, of course: the fact that this application communicates with (other applications) so that if you do something in one then you will be notified in another (…) will perhaps visualize to those involved that those requesting a leave of absence in two weeks’ time will automatically see it in GAT. And that they should watch out, as they have a full schedule in the outpatient clinic then. This may, to a certain extent, make individuals more responsible. (Department head in Dep2.)

I thought, ok, we have tried so many things. And we … we’re actually not managing. It's because we don't have enough physicians. If we had enough physicians, we would be much better able to get into balance. But, with the challenges we have had and with even fewer physician resources and with people still in training (…), the goal is so far ahead, that it … our situation was really very difficult. (Head nurse of Dep3 outpatient clinic.)

The lack of a belief, in Dep1, in the appropriateness of the suggested intervention meant that the new planning system was regarded by those involved as an extra workload that would not yield any significant benefits. In Dep2, the department head thought a more reliable and unchanging picture of the matching of resources and tasks might yield some benefits. The physicians, however, saw this as one more ICT application that they had to learn and spend time on:

(sighs) … Yet another administrative task forced upon us. This is not how we should be spending our time. It's a never-ending discussion. I expect that this will take up a lot of time. (Dep2 physician.)

Principal Support

All informants believed that the regional HR director, the highest level manager responsible for the programme, supported the process she had initiated. Department head support, however, differed greatly between departments.

The head of Dep1 was never fully convinced of the benefits of the project and did not offer the process any meaningful support. The division director did not prioritize attending workgroup meetings, which would have signalled the director's support for the process. Signals of principal support were therefore few. The Dep2 head made it clear that he supported the programme, but only the more limited version he chose to implement in his department. The Dep3 head and his sub-ordinate, the section head, committed to the process and took part in the participative workgroup process. All informants in this department emphasized that they interpreted this as being a leadership signal of the expectation of and permission to put time and effort resources into making the process successful.

Efficacy

Belief in efficacy was initially low in all departments. Previous introductions of new ICT applications had, to a great extent, been seen as being situations in which users were not proficient enough in their use to reap the full benefit of implementation. The implementation team considered the competence of Dep1 department members to be particularly low. They did not want to use smartphones, which would have given them easy access to the latest versions of plans. Their general ICT tool proficiency was also low.

All section head physicians in Dep2 had been trained in carrying out their part of planning in GAT. They, during this training, expressed a low level of belief in their efficacy to handle the new planning. The department head, however, believed that he and his department members would, in a relatively short period of time, reach a level of proficiency that was sufficient. The belief in efficacy was also, at the outset, low in Dep3. The participative process, however, greatly strengthened the belief in their efficacy. Department members gained experience through this in using GAT and continuously considered new ways of organizing services.

Department Level Readiness for Change

summarizes our findings on change beliefs in each department. We conclude, based on these findings, that department readiness for change was low in Dep1, medium in Dep2 and high in Dep3.

Table 3. Department level change beliefs and readiness for change.

Operative Department Level Translation of ATP and Resulting Practices

Department 1

Dep1 was the first of the three departments to join the ATP project. The operative translation primarily took place in a space formed by a series of department meetings attended by the department head, the head secretary, a few department physicians and the facilitation team. This space did not, however, constitute an arena for any extensive re-construction of the ATP idea and practice as strategically translated by the HR director into a working, local version. The department head undertook the operative translation in Dep1, using only a limited selection of editing practices and translation rules.

We found that reframing of the problem did take place. It was, however, reframed in the sense that the department head maintained that the only planning problem in the department was a lack of physician positions. Staging of the discussion was carried out in a quite exclusive way. It did not involve a broad range of participants from the department or beyond, and hospital division management from the organizational level above the department head rarely took part in or provided support to the process. Few staff members were involved in discussing ATP. Adjustment of the vision did take place. Like reframing of the problem, this adjustment did not build further on the vision from the strategic translation.

We found the following use of translation rules in the process of changing the strategically translated ATP concept into department-level practice. Planning in the new software system was copied as a basic scheme. Several elements were, however, omitted. Existing planning systems in other software or paper-based solutions were not removed, so remaining as shadow systems. The aspect of drawing all plans into one system was therefore omitted. Requiring that all changes to task plans were made in the new system was also omitted, as alternative ways for physicians to change shifts or swap tasks were left available. There was no significant evaluation of the way tasks were currently allocated and planned. The time period of detailed task planning was not extended, which is also an omission from the ATP idea and practice presented to the department.

Relatively few editing practices were used in the operative translation, important elements of ATP were omitted, no department-specific elements were added, and there were few signs of combining managerial concerns with professional considerations in this department, in which readiness for change was low. Few changes were therefore made to how task planning was carried out in Dep1. The idea and practice presented to the department through the strategic translation was scaled back, diminished and reduced. The potential of ATP to attain the stated organizational goals was therefore not realized. We have, based on these findings, identified the resulting translation of ATP in Dep1 as a poor translation.

Department 2

Translation took place in a less well-defined space in Dep2. The department head met sporadically with the facilitation team. This team provided technical support on how to set up the new system. Department-specific solutions were primarily developed by the facilitation team based on input from the department lead secretary. The main translators were, therefore, the department head and the lead secretary. Little wider staging of the discussion took place. Other senior physicians responsible for planning in department sub-sections took part in software training. They did not, however, take part in the shaping of the way planning would be carried out.

The strategically translated version of the problem, and the version found in Dep1, were framed differently. The department head argued that the department's main planning problem was discipline among physicians. Changes made to physician shifts were not always communicated to the department head and colleagues, and requests for leave and other changes to plans were often submitted at the last minute. The vision was adjusted to focus more on the department need for a clearer overview of physician resources, and less on the organizational goals of cutting waiting times and guarantee breaches. ATP implementation was therefore not rationalized as being a change that could solve all the problems presented in the strategic translation. It was, however, presented as a change that could potentially lead to benefits at the department level. The department head stabilized the meaning of ATP implementation by maintaining that the ATP system was useful, but that it provided a solution to fewer problems. Absent stakeholders (secretaries and patients) were taken into account by the department head through the head highlighting secretaries’ need to access real-time updated plans to avoid the rescheduling of patient appointments. The department head and the facilitation team spoke for the technology during software training by showing attendees how the new system could provide real-time overviews of plans, and by explaining that different software applications would be integrated so that all were kept up to date and would, therefore, show the same information. There was less selling of the change and more clear communication that a decision had been made to implement ATP.

Several elements of the strategically translated version of ATP were copied. The department head and lead secretary developed a basic scheme for planning tasks in the new system. They, after a short initial trial period, terminated the former Excel-based planning system to ensure that there would be no shadow systems. Strict rules were put in place that required all shift changes to be made well in advance and in the new software as opposed to verbally or directly between physicians. The department's planning horizon was also extended to give longer term planning. No significant elements were added. The elements of evaluating task planning and distribution, and extending detailed planning to four months were, however, omitted.

Dep2 (where readiness for change was medium) used more editing practices and omitted fewer ATP elements than Dep1. No department-specific elements were, however, added. There was also no merging of managerial and professional needs. The operative translation in Dep2, therefore, resulted in the implementation of a version of ATP that was quite similar to the version presented in the strategic translation. There was, however, no thorough process of evaluation of all the tasks performed by physicians in the department. There was also no consideration of whether allocating these tasks differently could help the department achieve the organizational goals at the heart of the project. The operative translation did not, therefore, unleash the full potential of ATP. In the light of this, we have determined that the Dep2 operative translation of ATP was moderately good.

Department 3

The operative translation in Dep3 primarily took place in the space of a series of eight working group meetings. The working group included the department head, the head of the organizational level above the department, members of the facilitation team, the head nurses of the department's outpatient and bed wards, several junior and senior physicians, and secretaries. These actors all took on translator roles in the meetings and between meetings as they worked on implementing ATP at the department level.

The broadly assembled working group who participated in the shaping of department-level ATP practice, served as an inclusive staging of the discussion. The problem at hand was reframed throughout their discussions. Group participants brought up the issues of heavy workloads, unpredictable schedules and insufficient opportunities for competence building. They also acknowledged waiting times and guarantee breech underperformance as being problematic. The vision of the ATP project was adjusted to a vision that focussed on reaching organizational goals by improving how the department planned tasks while also focusing on better working conditions in the department. The change was rationalized as providing solutions to organizational, professional and department level problems. The goal of both organizational and professional benefits at the department level was upheld throughout the working group meetings. This served to stabilize the meaning attributed to ATP in Dep3. Working group participants brought up absent stakeholders such as patients, other hospital departments and other hospitals that relied on services from Dep3 physicians. The group discussed how better planning practices would benefit absent stakeholders. They also discussed how improved planning could lead to less reliance on private providers that had been contracted to handle tasks the department was unable to perform. Working group members who had been given the opportunity to test the ATP system spoke for the technology to other group members throughout the meetings. Those who were most convinced of the benefits of ATP, also argued for it to members who aired disbelief. This contributed to selling the change.

Dep3, like Dep2, also copied elements presented in the strategic translation. Dep3 task planning was transferred to the new system, there were no shadow systems for planning after the implementation, all requests for changes to work plans were required to be made in the new software solution, and the planning horizon was extended. The four-month horizon was, however, omitted. In contrast to Dep1 and Dep2, however, the Dep3 working group also discussed the totality of necessary tasks and available physician resources in detail during their meetings. New solutions that could solve the mismatches that became apparent were discussed, decided upon, and implemented. Dep3 maintained all the above elements of the strategic translation in their operative translation. Dep3, however, also added new elements. A smaller group continued to collaborate with the facilitation team after the working group meetings were over, to improve planning processes and ICT solutions in the months after ATP implementation. The department also combined the ATP project with a Turn Up sub-project that aimed to re-organize hospital outpatient clinics. The two projects were combined to achieve synergies from considering their activities in a more holistic way. Dep3, furthermore, struggled to fill vacant physician positions. The Turn Up projects were therefore used to solve problems relating to the lack of qualified staff. One physician was moved from daily planning and maintenance of plans to clinical work. This move was a result of the ATP system being able to handle more of this work. A more comprehensive change was the moving of junior physicians to tasks in which they could build competence faster, so enabling them to take on more tasks without senior support. The department also used the system to bring mismatches between tasks and resources to the attention of higher-level management, and to argue for a re-negotiation of task distribution between the department and private providers.

Dep3, in which readiness for change was high, employed editing rules more extensively than the other two departments. Dep3 also added a number of their own elements to ATP and combined the managerial content of the planning practice with professional needs. The department was highlighted as being the one in which the ATP project had produced the most noticeable changes in results. The department head reported that ATP had resulted in a much less chaotic way of working. Everyone now knew what to do at what time. This provided a more predictable picture for those planning patient appointments, meaning that waiting lists were handled better and fewer patients experienced breeches in their waiting time guarantee. We have identified the outcome of the operative translation of ATP in Dep3 as a good translation.

The operative translation process findings for each department are summarized in .

Table 4. Department level operative translation processes and translation outcomes.

Discussion

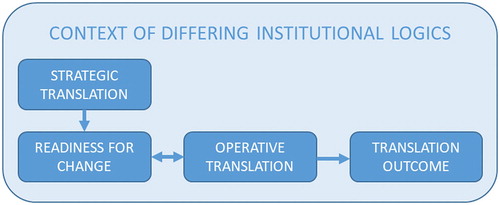

This paper examines the implementation of an ICT-supported task planning system for hospital physicians (ATP). We analysed the implementation process as an intra-organizational translation and focused on aspects that facilitate good translations. Data analysis identified that translation was carried out in accordance with the definition of translation as ‘the process in which ideas and models are adapted to local contexts as they travel across time and space’. The content of ATP did change through this process. The actors involved adapted the content through applying the editing practices and translation rules established in the literature that describe the practical details of translation. Our findings are consistent with Andersen and Røvik’s (Citation2015) identification that a concept is translated a number of times as it travels through the organization. Our findings are also in line with the basic translation theory assumption that spreading management concepts do not necessarily bring about identical organizational practices throughout an organization. presents a representation of our overall understanding of how the theoretical concepts used in this paper are related.

This paper provides a detailed empirical analysis of what facilitates good translations. This is an underexplored issue in translation research. We studied two consecutive translation processes and identified how ATP was first subjected to a strategic translation at the organizational level and was then subjected to an operative translation within each department. This analytical segmenting of the translation process, which to our knowledge is new to the literature, contributes to translation research by shedding light on how actors at different organizational levels contribute to idea variation (Radaelli & Sitton-Kent, Citation2016). Our study furthermore contributes to the understanding of translation by combining the concept of readiness for change with the frameworks of editing practices and translation rules. These were combined in an attempt to understand what facilitates good translations. We combined Teulier and Rouleau's editing practices, which are valuable tools in understanding how translators make sense of and change the meaning of a management idea, with Røvik's translation rules which focus on how proposed management practices change during translation. Our analysis reveals how department level readiness for change was fostered by the use of in the strategic translation. It also reveals how department level readiness then shaped the use of editing practices and translation rules in the operative translation, so facilitating translation outcomes of differing qualities. This paper, by linking the practices and rules used in translation with the quality of the outcome of translation, contributes to our understanding of successful and unsuccessful translation activities and editing practices (Teulier & Rouleau, Citation2013).

We first discuss our finding that different levels of readiness for change and specific change beliefs in the three departments relate to different uses of editing practices, translation rules and to the different translation outcomes. We then discuss how department level readiness for change was fostered by the strategic translation, and how this developed further during the operative translation. This identifies the potential for and limitation of readiness for change as a management tool for facilitating successful translations.

Readiness for Change, Editing Practices and Translation Rules in Operative Translation

Readiness for change is ‘a comprehensive attitude that (…) collectively reflects the extent to which an individual or a collection of individuals is cognitively and emotionally inclined to accept, embrace, and adopt a particular plan to purposefully alter the status quo’ (Holt, Armenakis, Field, et al., Citation2007, p. 235). We found that the department with the highest level of readiness for change (Dep3) staged a more inclusive and thorough operative translation process. This department not only employed more editing practices than the other two departments, but also employed them differently. This department also employed the translation rule of adding to the strategically translated version of ATP, and omitted very little. Dep3 operatively translated ATP in a way that was most closely aligned with the strategically translated version.

Our findings show the impact of change belief levels in the departments on whether and how editing practices were used to make sense of ATP. Belief in the discrepancy, i.e. the organization level strategic goals of reducing waiting times for patients and breeches of treatment guarantees, was high in all three departments. The other beliefs, however, varied. Belief in the appropriateness of ATP as a way of achieving the strategic goals was low in Dep1. The operative translation in Dep1 reframed the central problem of ATP not as a further development of the problem framed by the strategic translation. This was that long waits for treatment and guarantee breeches were a problem of insufficiently detailed, predictable and transparent planning. The problem was reframed by returning to and maintaining the problem definition that the department head believed was most salient at the start – a lack of physicians. The belief in appropriateness was medium in Dep2. The reframing of the problem constituted a shift in focus to a lack of planning discipline. The problem was reframed in Dep3, where belief in appropriateness was high, as one that combined the managerial concerns of stricter planning with professional concerns of competence building and working conditions.

Belief in appropriateness combined with a belief in the positive valence of ATP to staff had an impact on how the strategically translated idea and practice was rationalized and how meaning was stabilized during the operative translation. It also had an impact on whether translators engaged in selling the change. In Dep1, where belief in both was lacking, there were no signs of a rationalization of the change or a stabilization of new meaning beyond sticking to the pre-existing understanding of the problem. In Dep2, where belief in both were medium, the change was rationalized in relation to department-specific planning issues, which was a need for more control over physician resources. In Dep3, belief in both appropriateness and valence was high. Here the change was rationalized by linking the ATP solution to both organizational and department level problems. This maintained the dual focus of the reframed problem. The new meaning of ATP, as defined by the reframed problem and department level rationalization, was stabilized throughout the operative translation process in both Dep2 and Dep3. We however found in Dep3, where both beliefs were high, that the most convinced translators practiced selling of the change to less convinced working group participants. We also observed that translators spoke for the technology in the departments (Dep2 and Dep3) in which we found medium or high belief in appropriateness, valence and efficacy.

The belief in valence was also connected to the editing practices of adjusting the vision and taking absent stakeholders into account. In Dep1, where belief in valence was low, vision adjustment consisted of downscaling to a plan to move existing planning practices to the new software without making any changes to how planning was actually carried out. Level of detail or extension of the time horizon for task plans remained unchanged. In Dep2, where belief in valence was medium, vision adjustment shifted the focus from solving organizational problems to solving department-specific problems. In Dep3, belief in valence was high, and the operative translation process involved adjustment to a dual vision of solving both organizational and department level problems. This would be achieved by implementing a system that could enable the department to increase their contribution to the strategic goals and also strengthen the fulfilment of professional needs. The Dep2 and Dep3 translation processes also took into account a wider diversity of absent stakeholders. This extends the belief in the valence of ATP to also include patients and other hospital staff groups.

Finally, discussions were staged inclusively in Dep3, where there was strong principal support for the strategically translated version of ATP at several organizational levels. This is a factor of importance that we elaborate on below in the discussion of the quality of the translations.

The relationships between change beliefs and editing practices identifies a role for readiness for change in our understanding of how translation is performed. Comparing the three departments, we argue that readiness for change expanded the possibilities for operative translators to edit the practice in a way that combined the managerial elements of the strategically translated idea and practice with elements from department-specific practicalities and professional needs. The ways in which the translators used editing practices to make sense of ATP had a further impact on how they transformed the ATP practice by copying, omitting and/or adding elements. We found that readiness was associated with a more inclusive operative translation process characterized by an active involvement of multiple actors, and a more extensive use of editing rules and translation practices.

Good Translations

Our study contributes to the knowledge of translation quality through determining the three different department versions of ATP to be poor, moderately good and good translations. We base this categorization on Røvik’s (Citation2016) definition of good translations as being new versions of a managerial idea and practice that contribute to the achievement of organizational goals. Our analysis shows the degree to which the translated versions are coherent with a task planning system that enables hospital departments to improve their performance as measured by achieving stated, organizational goals. It also shows whether department members experienced the new practice as useful.

There were no task planning improvements in Dep1. Dep2 experienced an improvement in the control of the task planning process and an extension of the planning horizon. Dep3 thoroughly transformed and improved the way they allocated and planned tasks, and therefore was able to plan more predictably over longer periods of time. This department also saw a decrease in treatment guarantee breeches. It is difficult to measure the effect of improved task planning on this quality indicator due to the complexity of the factors that influence this. Department management and staff, however, believed that their less chaotic plans played a role in the development, and would continue to do so increasingly in the long run.

The most successful translation came out of a process in which all the editing practices identified by Teulier and Rouleau were extensively utilized. We argued above that this was facilitated by readiness for change. We further argue that this extensive use was an important factor that contributed to the outcome. An inclusive staging of the discussions in Dep3 first ensured participation from a broad group of actors. This contributed to a process in which many suggestions and viewpoints came to light, and a translation space in which problem reframing, vision adjustment, rationalization and meaning stabilization were highly participative practices. This ensured a strong grounding of the new idea and practice in the practical realities of department work. It also enabled the combination of the managerial aspects of the ATP idea with elements of professional needs and priorities. This was seen in the inclusion of the professionals’ need for competence building and more predictable working conditions in the reframed problem and the adjusted vision.

Inclusive staging also contributed to increased support for ATP throughout the process because a wide group of actors were present when practices of speaking for the technology and selling the change were employed. In other words, the initial readiness for change increased during the translation process. Dep3 furthermore employed the most thorough process of re-constructing ATP for department level use by adding department-specific concerns and practices to the strategically translated idea and practice (Røvik, Citation2016). The outcome was a practice that combined the initial intention of the regional HR department with that which the department itself defined as needs, leading ultimately to a more useful practice.

This result contrasts the outcomes of the two other departments. In these departments, translators used fewer editing practices and these practices were used in a less extensive way. The staging of discussions in these departments was exclusive, and reframing of the problem and adjustment of the vision was either a reversal and downscaling of the strategic translation, or a shift away from its focus. These two departments also neglected to use the translation rule of adding their own elements to ATP. In Dep1, change implementation can be characterized as being a process of de-coupling (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977), a reaction commonly found in studies of implementing new managerial practices in the professionalized hospital context (see for instance Kitchener, Citation2002; Mascia, Morandi, & Cicchetti, Citation2014). The department accepted the change as something that needed to be implemented in some form. However, few changes were made to planning practice. Dep2 implemented a practice of a stricter, managerial planning method to solve department-specific problems related to planning. It did not, however, engage in a process of exploring whether the new managerial practice could contribute to meeting professional needs.

In summary, these findings contribute to translation theory by empirically showing how a variation in the use of editing practices and translation rules in ‘real time’ translation work are linked to translation outcomes (Wæraas & Sataøen, Citation2014). The best ATP translation was the result of an operative translation process in which all editing practices were used. The practices that specifically relate to the content of the idea (reframing the problem and adjusting the vision) were used in a way that combined the content of the strategically translated managerial idea with department level professional needs and priorities. The translation rule of adding elements to the strategically translated ATP practice was also used to achieve the adjusted vision.

Good translations are, by definition, translation outcomes that help an organization achieve stated, organizational goals. In this study, we have evaluated how ‘good’ a translation is by the degree to which the resulting ATP practices in each department enabled the departments to improve their contributions towards the goals presented in . This criterion for translation outcome quality is probably one among many possible, alternative criteria. There may, particularly in complex organizations such as hospitals, be co-existing and more or less conflicting goals both at the organizational level, and especially among the priorities of different organizational actors (Denis, Langley, & Rouleau, Citation2010). We believe our categorization of the three versions of ATP that resulted from the department level operative translation processes as good, moderately good and poor translations is valid when held up against the stated, organizational goals of the ATP project. We, however, acknowledge the importance of being open to the fact that the categorization could have been different if measured against other goals.

Fostering Readiness for Change Through Strategic Translation

The readiness for change literature recommends persuasive communication and change agents communicating directly and verbally with the change recipients as an influence strategy for fostering readiness (Armenakis et al., Citation1993; Armenakis & Harris, Citation2002). The strategic translation performed by the regional HR manager can be construed as being such a persuasive communication attempt. We believe a successful strategic translation is necessary to ensure readiness for change. This in turn enables successful operative translations. It served as a way to sell the change to the recipient departments and was partially successful in persuading department level actors of the merits of ATP.

The HR manager, in particular, managed to present a discrepancy that was believable in the recipient context. This was aided by her explicating the professionals’ needs for less stressful working conditions and more predictability, and by her combining the strategic goals of cutting waiting times and guarantee breeches with the professional goals of securing competence building. She also avoided focusing on the increased managerial control and reduced autonomy in planning for individual professionals inherent in the ATP idea and practice. The HR manager strengthened the translation by achieving readiness for change through being aware of the potential differences in needs and priorities between her purely managerial department and the professionals at the level of hospital departments, and by using this awareness to edit the original idea. Other change beliefs were, however, less uniformly fostered by her translation across the departments.

The message of the strategic translation communicated well in Dep3 with recipients through relating to a ‘felt need’ of improving a chaotic working situation. This was communicated in a way that enabled agreement, particularly on what the discrepancy was, whether the suggested new practice was appropriate, and whether there was anything ‘in it for them’. The communicated message did not resonate as well in Dep1 and Dep 2, where there were powerful alternative explanations of what would be appropriate measures. The gain for recipients in putting their efforts into successfully implementing the new practice was therefore less certain. The belief persisted in these departments that adding more staff was the only way of resolving the problems that ATP was meant to alleviate. This illustrates that more practical, ‘felt need’ elements are also important in determining how a management idea and practice should be translated and foster the change beliefs necessary to achieve good translations. Fostering readiness through convincing strategic translations is a potentially valuable management tool. It may, however, be limited by practical realities that undercut otherwise persuasive communication.

It is important to note that readiness for change is not a static entity throughout change and translation processes. The readiness literature highlights that active participation by change recipients in the change effort, enabling enactive mastery, vicarious learning and participation in decision making, are all important in fostering readiness for change (Armenakis et al., Citation1993; Armenakis & Harris, Citation2002). The successful translation of ATP in Dep3 can be thought of as being the result of a virtuous circle of fostering change beliefs and readiness through translation. Initial readiness for change, fostered by strategic translation, enabled a process that included management and professionals. The HR manager's initial editing of elements of professional needs and priorities into ATP was continued as the idea and practice evolved. We observed how department-level change beliefs and readiness were strengthened through this process. An inclusive staging of discussions in particular meant that a wide group of the most convinced actors were present and practiced speaking for the technology and selling the change. In , the arrow therefore runs both from readiness to operative translation, and back from operative translation to readiness. This represents what we believe to be a self-reinforcing relationship.

We did, however, only find this continuous reinforcement of readiness for change in the department where readiness was already high after strategic translation. We, therefore, believe that this virtuous cycle requires a certain level of readiness to ignite it. Readiness for change after strategic translation in Dep3 facilitated a more inclusive and active participation from a wider group of actors and a more extensive use of editing practices and translation rules than in the other two departments. It also facilitated a continuous onwards development of readiness for change that reinforced active involvement in translating ATP, and a more successful translation outcome. The role of readiness for change in translation processes is therefore not merely as a potential outcome of strategic translation and a facilitator of good operative translations. Readiness for change is an element that is fostered by both strategic and participatory operative translation processes, it contributes to extensive and productive use of editing practices and translation rules in operative translation processes – and ultimately to good translations.

Conclusion, Limitations and Research Implications

This paper analyses how editing practices employed in the strategic translation of ATP are related to department level readiness for change, how differences in department-level readiness are related to the use of editing practices and translation rules in the operative translation processes, and how different constellations of editing practices and translation rules used in the operative translation processes are related to the quality of translation outcomes. Empirically, this analysis contributes through the finding that a strategic translation may foster readiness for change by using editing practices that are wisely tailored to the context in which they take place, i.e. by taking potentially differing needs and priorities between the source and recipient contexts into account. A high level of readiness after the strategic translation, facilitated an inclusive operative translation process in which editing practices and translation rules were extensively used. This process thoroughly reworked the new management idea and practice by developing problems and visions, and by stabilizing meanings which combined organizational, department and operative level needs. This new meaning opened up the opportunity to add practices that enhanced the quality of the resulting practice. The ultimate outcome of this operative translation process was a good translation.

The contribution of this paper to translation research, specifically to the issue of what facilitates good translations, can be summarized by three points. The first is that the detailed empirical analysis provides a theoretically informed example of how a good translation was achieved, pointing to the extensive use of editing practices and translation rules as being key. The second is our analysis of the translation process which indicates that it consists of two phases, strategic and operative translation. This is novel. The analysis of how different organizational actors took part in each phase also contributes to our understanding of how actors at different organizational levels contribute to idea variation. Finally, we have identified a role for the concept of readiness for change in understanding outcomes of translation processes. Strategic translations may be a suitable tool for fostering readiness for changes initiated by actors operating in a source context in which goals and priorities are often in conflict with the priorities of actors in the recipient context. This is challenging if the proposed change does not resonate with a felt need at the operative level. However, if initial readiness for change has in fact been established at the operative level after the strategic translation, then it may further develop through the operative translation. We envision this as a reinforcing cycle in which initial readiness facilitates an inclusive process characterized by extensive use of editing practices and translation rules. Readiness may continue to increase as more actors become more thoroughly convinced of the merits of the new management idea and practice. This can further enable operative level actors to adapt the content in ways that increase the quality of the translation outcome. We argue that readiness for change is indeed a key concept in the understanding of translation processes and the quality of translation outcomes.

This study is limited by the fact that we have not quantitatively measured and compared the attainment of organizational goals before and after the implementation of the three different versions of ATP. Our identification of poor, moderately good and good translations is based on whether or not we observed changes in planning practices that are consistent with the principles of the ATP project, and the experiences of improvements as reported by our informants. Further research could benefit from including organization-level data on goal achievement. We also believe that future research could build on, or challenge, the findings of this study by conducting longitudinal, mixed-method studies using existing quantitative instruments measuring readiness for change before and after strategic and operative translation processes. This could more clearly establish the effect of strategic translation on readiness.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for valuable discussions with Professor Arild Wæraas in the process of writing this paper, as well as for insightful comments from anonymous reviewers. We acknowledge the funding from and participation of the regional health authority, the hospital and the university in this project. The funders had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing or decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on Contributors

Olaug Øygarden completed a PhD in Management at the University of Stavanger. She is currently a Research Scientist at NORCE. Her research has centred on change management in professionalized organizations, focusing on challenges and opportunities in implementing change, as well as reform and management in the public sector.

Aslaug Mikkelsen is Professor of Management at the University of Stavanger Business School. She served as University President at the University of Stavanger from 2007 until 2011. In her doctoral research and several other large research projects, she has been particularly interested in leadership and organizational factors influencing health, working environment and productivity. She has published on subjects such as leadership, HRM, corporate social responsibility and occupational health in international journals as well as in books.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackroyd, S., Kirkpatrick, I., & Walker, R. M. (2007). Public management reform in the UK and its consequences for professional organization: A comparative analysis. Public Administration, 85(1), 9–26.

- Andersen, H., & Røvik, K. A. (2015). Lost in translation: A case-study of the travel of lean thinking in ahospital. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 401.

- Andersson, T., & Liff, R. (2018). Co-optation as a response to competing institutional logics: Professionals and managers in healthcare. Journal of Professions and Organization, 5(2), 71–87.