ABSTRACT

Despite leadership being considered essential to successful organizational change, reviews of empirical research on the subject reveal inconsistencies in the approaches to, and measurements of, both leadership and its impact on change outcomes. The study and development of leadership should reach beyond the simple focus on individual leaders and ultimately broaden our view of how the most meaningful impact can be made. Toward this end, a general framework of leadership in the implementation of change is provided. Starting from a functional perspective, it is proposed that leadership is provided by one or more leadership sources that independently or collaboratively enact a configuration of four leadership functions through specific behaviours from three behavioural meta-categories. It is additionally argued that leadership effectiveness – and the success of change – is a product of the degree to which the configuration of functions enacted sufficiently addresses the variety of situations leadership sources encounter. In this regard, the integrative framework offered here focuses primarily on what Rost [(1991). Leadership for the twenty-first century. Praeger] categorizes as the peripheral elements of leadership theory.

MAD statement

Our abruptly changing world has enhanced the complexity of workplace interaction, begging for a refined comprehension of, and approach to, leadership. This article takes its place in Making a Difference (MAD) by coordinating arguably disparate approaches to leadership into an integrated framework of leadership during change, answering the call for consistency in our understanding of the phenomenon. Specifically, this article ties different leadership sources, functions, and behaviours together in the context of situational dynamics to provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding leadership in the conduct of change.

Introduction

The view that leadership is essential to the successful implementation of change is central in the literature on organizational change (e.g. Burke, Citation2017; Kotter, Citation1996; Nadler & Tushman, Citation1990). Such a view seems warranted, given that leadership occurs in the context of change (Burke, Citation2017) in the extensive literature on the relationship of day-to-day leadership to individual, group and organization performance (Bass, Citation2008). Indeed, the centrality of this view is evidenced in Burke’s (Citation2008, p. 227) conclusion that even though there is ‘little evidence that scientifically demonstrates the leader’s impact … we will proceed … with the assumption that leaders have a significant influence on organizational change’.

As Burke correctly points out, there is little empirical evidence on the impact of change leadership (Ford & Ford, Citation2012). What evidence does exist varies considerably in the approaches to and measures of leadership used (e.g. Battilana et al., Citation2010; Gilley et al., Citation2009; Herold et al., Citation2008; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005), the complexity or phases of change examined (e.g. Battilana et al., Citation2010; Denis et al., Citation1996; Denis et al., Citation2001; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Oreg & Berson, Citation2011), and the change outcomes considered (Oreg & Berson, Citation2019). Although this research does collectively indicate that leadership has some impact on change implementation, these inconsistencies make it virtually impossible to compare and integrate findings in a meaningful way or come to any definitive conclusions regarding change leadership (Ford & Ford, Citation2012). In view of this type of difficulty, some authors have called for a reimagining of change leadership (Burnes et al., Citation2016). We concur it is time to expand our understanding of, and approach to, leadership in the implementation of change.

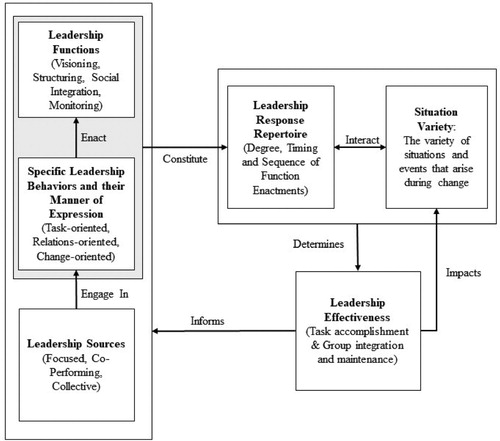

Starting from a functional perspective (e.g. Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Parsons et al., Citation1953), we propose that leadership in the implementation of change entails the fulfilment of leadership functions by one or more leadership sources (e.g. individuals and groups) enacting those functions independently or collaboratively at different times, to different degrees, and in different sequences, through specific leadership behaviours which are likely to vary with the nature and duration of the change. Further, we propose that effective leadership in the implementation of change is a product of requisite variety (Ashby, Citation1958), i.e. the degree to which the functions enacted by leadership sources effectively address the variety of situations encountered during change, resulting in favourable implementation outcomes. Our focus here, therefore, is on leadership, regardless of its source, rather than on people designated as leaders who are typically in formal positions of authority. In this regard, the framework developed here focuses primarily on what Rost (Citation1991, p. 3) categorizes as the peripheral elements of leadership, i.e. the ‘traits, personality characteristics, “born or made” issues, greatness, group facilitation, goal attainment, effectiveness, contingencies, situations, goodness, style, and above all, the management of organizations – public and private’.

Our intent is not to review the extensive leadership and change management literatures, but to begin a conversation for the development of a more general and integrative framework that can serve as a basis for future research and thinking about leadership in the implementation of change. By general, we mean a framework that it is applicable to any change regardless of the organizational level at which it occurs, or the type of change involved. By integrative, we mean a framework that integrates functional, behavioural, and contingency approaches to leadership from a behavioural context. As such, our view of leadership is limited to interactions among people where those interactions are behavioural in nature, i.e. involve ‘doing’ and ‘saying’ things. We begin by establishing the foundations of functional leadership, the behaviours that enact those functions, and the leadership sources that engage in those behaviours. We then propose that the successful implementation of change is a product of requisite variety in which the functions enacted through specific leadership behaviours by leadership sources is effective in dealing with the myriad of issues and situations that arise during the implementation of change. The elements of the framework we are proposing and the relationship among them are illustrated in .

Leadership: Functions and Their Enactment

There are a variety of approaches to the study of leadership (Avolio et al., Citation2009; Bass, Citation2008; Drath et al., Citation2008; House & Aditya, Citation1997). The functional approach (e.g. Bavelas, Citation1960; Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Hackman & Walton, Citation1986; Morgeson et al., Citation2010), proposes that leadership is itself a function, the main job of which ‘is to do, or get done, whatever is not being handled for group needs’ (McGrath, Citation1962, p. 5). According to this perspective, the job of leadership is to ensure that all functions necessary for task accomplishment and group integration and maintenance, including adaptation and innovation to internal and external conditions, are dealt with effectively (Burke et al., Citation2006; Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Mumford & Connelly, Citation1991; Parsons et al., Citation1953). If all functions are adequately taken care of, then leadership has done its job (Hackman & Wageman, Citation2005).

From a functional perspective, the job of leadership can be understood by focusing on the functions that those engaged in leadership must take care of or fulfil to ensure task accomplishment and group integration and maintenance (Fleishman et al., Citation1991; House & Aditya, Citation1997). Although there is no agreement in the literature as to the specific set of functions that constitute leadership, our review of functional approaches indicates four ‘generic’ functions they share in common. What makes these leadership functions generic is that ‘they are likely to be required of one or more [leadership sources] in the normal functioning of groups or organizations, although not necessarily required at all times, or of the same [leadership source(s)] at the same time’ (House & Aditya, Citation1997, p. 449). The four generic functions are:

Visioning, characterized by creating a vision, aim, purpose, or direction, a possible plan or strategy for achieving it, engaging people in its accomplishment, and initiating revisions as new situations arise and new information becomes available (Behrendt et al., Citation2017; Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Hackman & Wageman, Citation2005; Heller & Firestone, Citation1995; Morgeson, Citation2005; Morgeson et al., Citation2010; Smircich & Morgan, Citation1982; Yukl, Citation2012; Zaccaro et al., Citation2001).

Structuring, characterized by the differentiation and integration of work for accomplishing the vision; planning for, acquiring, providing, and utilizing material resources; removing obstacles to accomplishment; and generating new solutions to organization and coordination problems (Behrendt et al., Citation2017; Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Hackman & Wageman, Citation2005; Heller & Firestone, Citation1995; Morgeson et al., Citation2010; Yukl, Citation2012).

Social Integration pertains to maintaining and enhancing the collaboration of personnel resources by promoting cooperation and a positive climate, facilitating their development, and engaging with and supporting their participation and contribution (Behrendt et al., Citation2017; Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Heller & Firestone, Citation1995; Klein et al., Citation2006; Morgeson, Citation2005; Morgeson et al., Citation2010; Yukl, Citation2012).

Monitoring encompasses watching for, observing, and being mindful of situations and events and acquiring information to discern any threats to and opportunities for accomplishing a vision that would warrant modifications to the vision, structuring and social integration. (Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Heller & Firestone, Citation1995; Morgeson, Citation2005; Morgeson et al., Citation2010)

When applied to the implementation of change, a functional approach indicates that leadership involves creating a clear direction for the change (i.e. visioning), organizing and coordinating the work involved (i.e. structuring), engaging and developing people for its accomplishment (i.e. social integration), and attending to events and occurrences in and around the change so that appropriate actions can be taken and modifications made (i.e. monitoring). This does not mean, however, that all four functions are satisfied equally, completely, or even at the same time. Rather, functions can be fulfilled to different degrees at different times by different people during change (Bales, Citation1950; Morgeson et al., Citation2010). It does mean, however, that if leadership sources emphasize some functions, e.g. structuring, to the exclusion or detriment of others, e.g. social integration, they may accomplish the change but fail to maintain the social system, or preserve the social system and fail to accomplish the change (Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, Citation2006).

Proposition 1: Leadership in the implementation of change involves fulfilling the four generic functions of visioning, structuring, social integration, and monitoring. (See )

The Behavioural Enactment of Leadership Functions

Whereas the fulfilment of generic leadership functions can be understood as the ‘what to do’ of leadership in the implementation of change, ‘how’ those functions are enacted and fulfilled (Marks et al., Citation2001) is through specific leadership behaviours in interactions with others (Behrendt et al., Citation2017; House & Aditya, Citation1997; Yukl, Citation2012), which behaviours include specific communications and conversations (e.g. Ford & Ford, Citation1995; Ford & Ford, Citation2002; Winograd & Flores, Citation1987). Research on behavioural leadership theories indicates the specific leadership behaviours that enact the generic leadership functions come primarily from three general meta-categories of behaviours: task-oriented, relations-oriented, and change-oriented behaviours (Bass, Citation2008; Ekvall & Arvonen, Citation1991; Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Yukl et al., Citation2002). Behaviours from each of these meta-categories have been found to be significant in research on leadership effectiveness and appear in virtually every leadership behaviour classification system under such labels as ‘initiating structure’, ‘production oriented’, ‘consideration’, and ‘people oriented’ behaviours (Arvonen & Ekvall, Citation1999; Bass, Citation2008; Behrendt et al., Citation2017; Ekvall & Arvonen, Citation1991; Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Yukl, Citation1999b, Citation2012; Yukl et al., Citation2002).

Although specific leadership behaviours from one meta-category predominantly enact a single leadership function, those same behaviours may also contribute to the secondary or even tertiary enactment of one or more other leadership functions (Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Yukl et al., Citation2002). Conducting a team discussion on change implementation, for example, may serve the primary purpose of clarifying, dividing, assigning, and coordinating the work involved (e.g. enacting the structuring function), while also building group coherence and collaboration (e.g. contributing to enactment of the social integration function) and even provide some clarity of direction and purpose (e.g. contributing to enactment of the visioning function). Engaging in a single specific leadership behaviour, therefore, can result in the enactment of several functions, and the enactment of a single function can be the product of a combination of leadership behaviours from different meta-categories, some of which have a secondary or tertiary relationship to the function. As a result, leadership sources that engage in specific leadership behaviours from one meta-category, e.g. task-oriented, with the intent of enacting and fulfilling one function, e.g. the structuring function, may also end up enacting other functions e.g. the social integration function, as well as benefitting from behaviours from other meta-categories, e.g. relations-oriented, being used to enact other functions, e.g. social-integration.

A specific set or combination of behaviours, therefore, can enact different functions to different degrees. Yukl et al. (Citation2002) have shown that the set of leadership behaviours comprising transformational leadership are primarily change-oriented and secondarily relations-oriented, whereas, those comprising transactional leadership are primarily task-oriented and secondarily relations-oriented. This implies that these two types of leadership enact a different combination of leadership functions. Since both of these types of leadership engage in some relations-oriented behaviours, it also suggests that together they will enact those leadership functions dependent on relations-oriented behaviours to a greater degree than either alone, thus making them complementary (Bass, Citation2008).

The same generic function, therefore, can be enacted and fulfilled through a variety of different behaviours. For example, in one setting an issue of social integration, e.g. conflict, may be dealt with publicly in a group meeting, whereas, in another it is dealt with in a private one-on-one meeting. Furthermore, behaviours that are understandable and effective in one setting, such as those that are culturally or organizationally grounded, may not be effective in another setting and thus will not be used (House & Aditya, Citation1997). In this respect, the specific behaviours used in enacting leadership functions are bounded by organizational and interactional contexts, i.e. not any and all behaviours are available. This means that even though leadership sources engage in behaviours from the same meta-category, the specific behaviours in which they engage can vary widely.

But it is not just the behaviour per se that enacts a function, it is also the manner or style in which the behaviour is expressed (House & Aditya, Citation1997). The extensive research on trait theories of leadership indicate that people with different traits and characteristics, e.g. different personalities, engage in the same types of behaviour differently which has a different impact on individual and group task accomplishment and group maintenance (Bass, Citation2008). For example, the same leader behaviour, such as making an assignment, may be expressed considerately or abusively (Tepper, Citation2007), personally or impersonally, authoritatively or humorously. There is, therefore, considerable variation possible in the manner or style in which specific leadership behaviour(s) enact or fulfil a function.

Finally, the behavioural enactment of functions is not a ‘one-way’, one-and-done occurrence from leadership sources to others. Enactments occur within a context and structure of interaction (e.g. Giddens, Citation1984) and may be contested or negotiated (Barbalet, Citation1985; Brower & Abolafia, Citation1995; Caruth et al., Citation1985; Ford & Ford, Citation2009; Piderit, Citation2000). As a result, it may take a combination of specific leadership behaviours over a period of time to enact and fulfil any particular function.

Proposition 2: Leadership functions are enacted through specific combinations of task-oriented, relations-oriented, and change-oriented leadership behaviours and the manner or style in which they are expressed. (See )

Leadership Sources

Although leadership has been approached from a variety of theoretical perspectives (Bass, Citation2008), there appears to be some agreement that leadership involves interpersonal influence that arises in and from the dynamic interactions of individuals in the context of specific situations in which they are embedded (Mumford & Connelly, Citation1991). Yukl (Citation2012, p. 66), for example, defines the essence of leadership as ‘influencing and facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish shared objectives’. From a functional perspective, the focus or purpose of this influence is the enactment of one or more leadership functions, and the means of influence are specific leadership behaviours and the manner in which they are expressed. For most of the research on leadership, this influence has been viewed as coming from a single individual, typically someone in a formal or hierarchical position, i.e. ‘the leader’. As a result, research has focused primarily on these select individuals, defined not by interpersonal influence but by their location or position, in which leadership is considered a personal possession (Fleishman et al., Citation1991) and influence is ‘one-way’ from ‘the leader’ to ‘followers’ (Drath et al., Citation2008).

Leadership, however, is not necessarily limited to any one individual or position but is a product of interactions in which participants influence and are influenced by each other to varying degrees at different times and in different situations (e.g. Avolio et al., Citation2009; Cullen-Lester & Yammarino, Citation2016; Denis et al., Citation2001; Gronn, Citation2000). Yukl (Citation1999a, p. 298), for example, indicates that a vision is ‘usually the product of a collective effort, not the creation of a single, exceptional leader’. Our interest, therefore, is not with specific individuals or groups designated as ‘leaders’, but with leadership, i.e. the enactment of leadership functions through specific leadership behaviours by one or more leadership sources regardless of their positions (Gibb, Citation1968; Gronn, Citation2000; Pearce & Sims, Citation2002). Gibb (Citation1968) proposes two forms of leadership sources: focused and distributed.

Focused Leadership

Focused leadership is the predominant form of leadership studied in both the traditional (Bass, Citation2008) and change leadership literatures (Ford & Ford, Citation2012; Oreg & Berson, Citation2019), in which individual, group, and change outcomes are attributed to the traits and behaviours of a single individual who is typically in a formal or designated position of authority, i.e. ‘the leader’ (e.g. Battilana et al., Citation2010; Gilley et al., Citation2009; Herold et al., Citation2008; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2000; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005, Citation2009; Wren & Dulewicz, Citation2005). Focused leadership represents the most concentrated form of leadership in which the unit of analysis is a sole individual (Gronn, Citation2002b). The leadership functions enacted are a product of the specific leadership behaviours engaged in by this single individual.

Distributed Leadership

Distributed leadership occurs where leadership is provided by more than one individual, regardless of their position or the degree, frequency, or duration of their leadership (Gronn, Citation2002b). As Yukl (Citation1999a, pp. 292–293) points out, distributed leadership …

does not require an individual who can perform all of the essential leadership functions, only a set of people who can collectively perform them. Some leadership functions (e.g. making important decisions) may be shared by several members of a group, some leadership functions may be allocated to individual members, and a particular leadership function may be performed by different people at different times. The leadership actions of any individual leader are much less important than the collective leadership provided by members of the organization.

Co-performing Distributed Leadership

Co-performing leadership is a form of reciprocal interdependence (Thompson, Citation1967) characterized by two or more conjoint agents who collaborate to coordinate their leadership, i.e. to ‘synchronize their actions by having regard to their own plans, those of their peers, and their sense of unit membership’ (Gronn, Citation2002b, p. 431). Spontaneous collaborations are an emergent form of co-performing leadership that arise in the context of a specific situation, e.g. a crisis or breakdown, and are jointly constructed by participant’s interactions as they pool and coordinate their expertise and actions to deal with the situation. Spontaneous collaborations are ad hoc and temporary, and dissolve with the resolution of the situation for which they emerged.

Intuitive working relationships are non-formal structures that exist where two or more interdependent participants have developed a close working relationship over time within an implicit framework of mutual understanding and trust, and operate together as a unit (Gronn, Citation2000, Citation2002b). Such relationships are evident in the partnerships that develop among senior level managers (e.g. Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Gronn, Citation1999; Hodgson et al., Citation1965; Stewart, Citation1991), in situations where formally designated leaders develop high quality working relationships with subordinates who are ‘trusted assistants’ (e.g. Balkundi & Kilduff, Citation2005; Boies & Howell, Citation2006; Graen & Scandura, Citation1987; Graen & Uhl-Bien, Citation1995) or serve as ‘informal’ leaders in an ongoing supportive and collaborative working relationship (e.g. Bales, Citation1950; de Souza & Klein, Citation1995; Neubert, Citation1999; Pescosolido, Citation2001, Citation2002; Wheelan & Johnston, Citation1996). The partnership between a university president and an executive vice-president during a strategic change (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991) is illustrative of an intuitive working relationship.

Institutionalized structures and practices are formalized versions of co-performing leadership between two or more interdependent participants that can range in duration from relatively short-lived, single-purpose transition or change management teams (Duck, Citation1993; Joffe & Glynn, Citation2002) to longer term arrangements such as management teams (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, Citation2006), dominant coalitions (Kotter, Citation1996) or role constellations (Denis et al., Citation2001). Institutionalized structures involve more prescribed relations and arrangements that attempt to regularize leadership through the use of formally established roles and practices in which leadership responsibilities may be assigned according to conventions, codes, and routines (Brown & Eisenhardt, Citation1997; Gronn, Citation2000, Citation2002b). Within institutionalized structures, the membership and composition of the group and the dynamics among participants can change (Denis et al., Citation2001; Hodgson et al., Citation1965; Joffe & Glynn, Citation2002).

With each form of co-performing distributed leadership, the unit of analysis and the source of leadership is the co-performing unit. This means that the specific leadership behaviours in which individual members engage, and the functions they enact or contribute to enacting, are the product of interaction and negotiation among participants, not the product of a single individual. As one progresses from spontaneous collaborations to institutionalized structures, the degree to which individual behaviours are regularized increases, making member behaviours more a function of the behavioural integration within the unit than individual discretion (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, Citation2006). Finally, co-performing units can be composed of people from different positions within the organization, e.g. managers and their direct reports, employees, managers from different levels in the organization, etc.

Collective Distributed Leadership

Unlike the concerted conjoint action of co-performing leadership, collective distributed leadership occurs when two or more agents (e.g. multiple individuals or groups) engage in leadership independently of one another. Collective leadership is a form of pooled interdependence (Thompson, Citation1967) in which leadership functions are enacted by an aggregate of individual agents (Gronn, Citation2002b). This form of leadership is evidenced whenever an entire group or category of individuals, such as ‘organization supervisors’ or ‘senior management’ (e.g. Lyons et al., Citation2009), is considered the source of leadership, or in cases of shared or team leadership (e.g. Pearce & Sims, Citation2002) where there is no evidence of concertive conjoint activity among the individuals. With collective distributed leadership, the unit of analysis is the collection or aggregate of individuals.

Since there is no collaboration and coordination among participants in collective leadership, the leadership functions they enact can be complementary, redundant, or contradictory to each other, i.e. serve as substitutes (Hodgson et al., Citation1965; Howell et al., Citation1990; Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997; Kerr & Jermier, Citation1978). Substitutes are situational factors that can complement and enhance, as well as counteract, suppress or nullify the leadership functions provided by a leadership source. Positional (i.e. focused) and shared (i.e. collective distributed) leadership, for example, have been shown to be complementary in explaining team effectiveness (Pearce & Sims, Citation2002), whereas, supervisor-level leadership has been shown to be redundant to that of senior-level leadership sources in terms of its impact on change readiness (Lyons et al., Citation2009). Still other studies indicate that the leadership provided by one source may resist, constrain, counteract, or suppress the leadership provided by another (Kan & Parry, Citation2004; Young, Citation2000).

Leadership in the implementation of change is provided through the enactment of leadership functions by the specific leadership behaviours engaged in by a single individual (i.e. focused leadership), a group of people acting in concert to coordinate their enactments (i.e. co-performing distributed leadership), or an aggregate of separate individuals or small groups acting independently of each other (e.g. collective distributed leadership) whose enactments are complementary, redundant, or even contradictory to each other (Denis et al., Citation1996; Denis et al., Citation2001; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Hodgson et al., Citation1965). Furthermore, since the implementation of change is dynamic, the number and types of leadership sources involved can vary over the duration of a change, resulting in leadership being provided by a constellation of leadership sources (Denis et al., Citation2001; Hodgson et al., Citation1965). A focused leadership source, for example, can expand into a co-performing source (Gioia et al., Citation1994; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991) comprised of members who are internal and external to the system undergoing change (Denis et al., Citation2001; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Heller & Firestone, Citation1995; Morgeson et al., Citation2010; Pearce & Sims, Citation2002) and whose membership changes during the change (Denis et al., Citation2001; Joffe & Glynn, Citation2002). Similarly, a co-performing intuitive working relationship can operate independently of a co-performing institutionalized structure on different parts of the same strategic change at different times (Gioia et al., Citation1994; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991). Leadership sources, therefore, can range from a single leadership source, e.g. focused leadership, to various combinations of sources, i.e. a constellation of sources, at different times and for different durations over the course of implementation.

Proposition 3: The specific leadership behaviours and the manner in which they are expressed to enact leadership functions are engaged in by one or more leadership sources acting independently or collaboratively during the implementation of change. (See )

Requisite Variety in Leadership

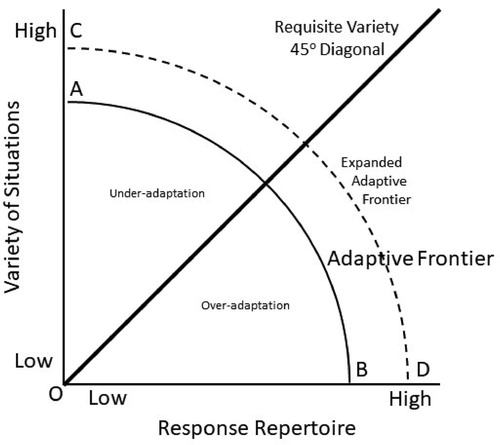

Contingency theories of leadership suggest that leadership in the implementation of change will be effective to the extent that the leadership functions enacted are appropriate to the situational context (Bass, Citation2008). These theories are consistent with Ashby’s (Citation1958) law of requisite variety which proposes that ‘the variety within a system must be at least as great as the environmental variety against which it is attempting to regulate itself’ (Buckley, Citation1968, p. 495). In order for a system, in this case leadership sources, to achieve a preferred, favourable, or ‘good’ outcome in the face of a variety of disturbances from its environment, it requires a repertoire of responses that can deal effectively with those disturbances (Ashby, Citation1958; Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011). An organism attacked by a variety of bacteria, for example, each of which requires a different anti-toxin, needs as many anti-toxins in its response repertoire as the variety of bacteria that attack it if it is to survive (i.e. have a ‘good’ outcome). Similarly, for a fencer to successfully parry the attacks of an opponent, the fencer must be able to provide a variety of defenses that will meet the variety of attacks used by the opponent (Ashby, Citation1958). Applying the law of requisite variety to leadership in the implementation of change implies that leadership sources must have a repertoire of responses that can successfully deal with the variety of situations they encounter during implementation. The relationship between situation variety, response repertoire and effectiveness is illustrated in .

Figure 2. Requisite Variety. Adapted from Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011. Complexity and organization-environment relations: Revisiting Ashby’s law of requisite variety. In P. Allen, S. Maguire, B. McKelvey, (Eds.), Sage Handbook of Complexity and Managrment, 279–298, Los angeles, CA: Sage.

Response Repertoire

Several leadership researchers and theorists have argued that leadership sources must be highly flexible, responsive, and adaptive. Zaccaro et al. (Citation1991, p. 317), for example, suggests that ‘socially intelligent’ sources have both the social perceptiveness and behavioural flexibility ‘to ascertain the demands, requirements, and affordances in organizational problem scenarios and tailor their responses accordingly’. Similarly, Denison et al. (Citation1995, p. 526) argue that ‘effective [leadership sources] are those who have the cognitive and behavioural complexity to respond appropriately to a wide range of situations that may in fact require contrary and opposing behaviors’. Yukl and Lepsinger (Citation2004, p. 203) underscore this perspective, arguing that leadership sources must display flexibility in order to ‘balance competing demands and reconcile tradeoffs among different performance determinants’. Together, these authors indicate that leadership sources will be successful to the degree they can appropriately adjust their responses to the situation variety they confront, i.e. they are varied and diverse in their response repertoire.

On the horizontal axis in is the leadership response repertoire, ranging from low to high, of responses leadership sources can marshal in the face of the variety of situations and events they confront, i.e. what they can do. A low response repertoire exists when leadership sources have both a limited ability to make sense of different situations (e.g. distinguish among them) and a limited set of responses available for dealing with those situations. A high response repertoire means leadership sources have both the ability to distinguish many different types of situations and have considerable latitude and flexibility in their ability to create and implement responses through exploration, experimentation, innovation, improvization, and the invention of new knowledge (Bechky & Okhuysen, Citation2011; Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011; Garud & Karnoe, Citation2003; Heifetz, Citation1994; Heifetz & Laurie, Citation1997). The breadth and depth of a response repertoire is reflected in the functions enacted, including the degree, timing, and sequence of their enactments (Amis et al., Citation2004; Huy, Citation2001) as well as the specific leadership behaviours used for enacting those functions and the manner or style in which those behaviours are expressed. This relationship is shown in by the ‘constitute’ arrow from the box containing both the leadership functions enacted and specific leadership behaviours to the box for leadership response repertoire.

Enactment degree refers to the extent, level, or magnitude, i.e. ‘how much’, each leadership function is enacted by leadership sources. Behavioural theories of leadership indicate that leadership sources will be most effective if they engage in ‘high’ levels of leadership behaviours, implying that leadership functions should also be enacted at high levels. Functional approaches to leadership, however, do not require that all functions be enacted, or enacted to the same degree, or even enacted consistently over time, only that enactments be sufficient for task accomplishment and group integration and maintenance. This is illustrated in McGrath’s (Citation1962, p. 10) statement that ‘each individual needs enough, but not too much inclusion, affection, and control’ (i.e. social integration). Since leadership behaviours can enact more than one function (Yukl et al., Citation2002), the degree to which functions are enacted depends on whether the leadership behaviours used are complementary, redundant, or contradictory. Providing too much role clarity, for example, may be viewed as evidence of mistrust (Zheng et al., Citation2016), suggesting that enacting ‘high’ levels of the structuring function can be contradictory to the social integration function. An increased emphasis on task oriented behaviours can be more acceptable where a sufficient level of emphasis on relations oriented behaviours is also provided (Ford et al., Citation2014; Rauch & Behling, Citation1984). It is not necessarily the case, therefore, that leadership sources should engage in ‘high’ levels of particular behaviours, or that ‘high’ levels are even required in order to effectively enact leadership functions. This means it is not simply the degree, magnitude, or frequency (e.g. ‘high’ or ‘low’) with which leadership sources engage in particular behaviours, but the combinations of those behaviours that determine which functions are enacted and their degree of enactment (Arvonen & Ekvall, Citation1999; Behrendt et al., Citation2017; Misumi & Peterson, Citation1985; Rauch, Citation1981; Rauch & Behling, Citation1984).

Enactment timing refers to when a function is enacted and for how long, including the duration of waiting before enacting more of the same or another function though the same or different leadership behaviour(s). Situations and events vary in the speed at which they move, affecting the timing of leadership responses (Amis et al., Citation2004; Weick, Citation1983). Doing things ‘before their time’ leads to time pressures (J. E. McGrath, Citation1991), errors in sensemaking, ineffective responses (Gersick, Citation1988, Citation1989), and system deterioration (Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, Citation2006). Taking too long can contribute to inertia and resistance (Romanelli & Tushman, Citation1994) and reduce the time available for future responses (Van Oorschot et al., Citation2013). Going too fast, on the other hand, reduces the opportunity to fully consider alternative responses (Weick, Citation1983) and build the relationships and trust (i.e. social integration) that can support change (Pettigrew, Citation1990). Response timing impacts the pace (Amis et al., Citation2004), rhythm (Klarner & Raisch, Citation2013) and momentum of change, and will vary depending on whether leadership function enactments are based on: ‘time pacing’, which is temporality-based by a clock or intuition; ‘event pacing’, which is based on the occurrence of specific events independent of the time of their occurrence, e.g. when a result is produced; or some combination of the two (Gersick, Citation1994). Additionally, both time and event pacing will vary depending on whether they are ‘fixed’, i.e. where leadership sources are obligated to follow a specific timeline or sequence of events as is likely in co-performing sources, or are ‘discretionary’, where leadership sources are free to respond as they see fit (Huy, Citation2001) as is likely in collective sources.

Enactment sequence refers to the order in which functions are enacted. Although all leadership sources must make choices regarding the functions they enact, the sequence in which they enact those choices will vary (Gersick, Citation1991). Leadership sources that believe changes should begin quickly are likely to enact task accomplishment functions first, e.g. structuring, followed by more group maintenance-oriented functions, e.g. social integration. Leadership sources that believe changes should move more slowly to develop relationships and trust will follow a different sequence (Gersick, Citation1988, Citation1989, Citation1994; Pettigrew, Citation1990). As the complexity of change and situation variety increase, the path of change becomes more indeterminate, making appropriate response sequences more ambiguous and uncertain (Amis et al., Citation2004; Brown & Eisenhardt, Citation1997; Cohen & Bacdayan, Citation1995; Pentland & Haerem, Citation2015) and suggesting a need for greater variety in response sequencing. Differences in interventions used (Huy, Citation2001) and change processes followed can also impact the sequence of functions enacted (e.g. Elrod & Tippett, Citation2002; Gersick, Citation1989, Citation1991; Kotter, Citation1996; Lewin, Citation1947; Prochaska et al., Citation2002).

The importance of enactment sequences is indicated by a review of different change process models from disciplines that address people’s responses to change, which found that all models share a common curvilinear pattern involving a ‘transition from normality through some form of disruption and then to a redefined normality’ (Elrod & Tippett, Citation2002, p. 285). During the period of disruption, there is a degradation in performance as participants deal with their affective responses to change. This curvilinear pattern – which parallels patterns observed in studies of change momentum (Jansen, Citation2004; Jansen & Hofmann, Citation2011) and team development (Gersick, Citation1988, Citation1989) – suggests that the sequence and timing of functions enacted and the degree of their enactment need to vary over the course of a change. Additional support is provided by research on group and team leadership which indicates that leadership sources cycle through the emphasis they place on different functions at different times (Bales, Citation1950; Morgeson et al., Citation2010), by research indicating that different leadership behaviours are more effective in different phases of change (Battilana et al., Citation2010), and by findings that change recipients who begin with little or no intention of resisting change (Oreg & Berson, Citation2011) may become resistant as enactments occur and they learn more about what the change entails (Ford et al., Citation2008; Oreg et al., Citation2018).

Proposition 4: Response repertoires are constituted by the leadership functions enacted, the degree, timing, and sequencing of their enactments, the specific leadership behaviours used, and the manner in which those behaviours are expressed. (See )

Situation Variety

Numerous factors can contribute to situation variety. Among these are the type of change undertaken (Bartunek & Moch, Citation1987; Gersick, Citation1991; Tushman & Romanelli, Citation1985; Weick & Quinn, Citation1999), the scale and scope of change (e.g. Ledford et al., Citation1989), the depth of change (Bartunek & Moch, Citation1987; Heifetz et al., Citation2009), the phase of change (Battilana et al., Citation2010; Lewin, Citation1947), the type of interventions used (Huy, Citation2001), the forms of resistance encountered (e.g. Kotter & Schlesinger, Citation1979), the emotional reactions of change participants (Huy, Citation2002), and shifts in momentum (Jansen, Citation2004; Jansen & Hofmann, Citation2011). As the number and degree of these factors increase, changes become more complex and complicated to implement. The result is an unfolding cascade of events that cannot be known in advance and that reveal or create new situations (Amis et al., Citation2004; Gersick, Citation1991), cause delays or revisions to what has already been done or needs to be done, and negatively impact the pace, sequence, and momentum of change (Amis et al., Citation2004; Jansen, Citation2004; Jansen & Hofmann, Citation2011), causing it to move in unexpected fits and starts (Denis et al., Citation2001). Increases in situation variety, therefore, require a more extensive response repertoire including the generation of innovative and creative responses (e.g. Heifetz, Citation1994).

Situation variety also includes other factors, such as the experience and capabilities of the people involved and the existence of institutionalized practices, routines, and capabilities for dealing with change that may serve as substitutes for leadership, thereby influencing which functions are enacted, their degree, timing, and sequencing, the behaviours used to enact them, and their manner of expression (Brown & Eisenhardt, Citation1997; Howell et al., Citation1990; Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997; Kerr & Jermier, Citation1978). For example, groups experienced with change that have developed specific change routines and capabilities can require less leadership than other groups confronting the same types of changes that have less experience or do not have established change routines and capabilities (Brown & Eisenhardt, Citation1997).

Leadership sources, however, do not respond to situations directly, but to their interpretations, understandings, and constructions of those situations (Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011; Ford, Citation1999; Weick, Citation1995). Whether situation variety is considered low or high, or which substitutes, if any, are present and to what degree, is fundamentally a conclusion drawn by the leadership sources involved (Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011; Ford, Citation1999) and is a function of the information they gather (Fleishman et al., Citation1991; Weick, Citation1995) and the distinctions they can draw based on their response repertoire (Ashby, Citation1958). A leadership source that can only distinguish letters, but not their case, for example, will characterize a situation constituted by the five-letter sequence c d C D c as ‘low’ in variety because it contains only two letters, c and d. The two capital letters will constitute information the leadership source doesn’t register as distinct and is unable to process or make sense of (Weick, Citation1979, Citation1983). A leadership source that can distinguish both letters and their case, however, will consider that same letter sequence ‘higher’ in variety because they can register, process, and make sense of the sequence. There is a difference, therefore, between a situation as it ‘is’ and the situation as it is understood or interpreted, i.e. made sense of, by leadership sources (Bohm, Citation1996; Senge et al., Citation1994; Watzlawick, Citation1990).

What constitutes situation variety, therefore, is a combination of two factors. One is the physically demonstratable, publicly discernible, and empirically verifiable characteristics, qualities, or attributes of the event or situation, what Bohm (Citation1996) refers to as a presentation and Watzlawick (Citation1990) as a first order reality. These are the facts, data, and attributes, that exist independent of one’s conclusions, opinions, interpretations, e.g. the specific number of people in a room. The second factor is what Bohm (Citation1996) terms a representation and Watzlawick (Citation1990) a second order reality, which is the meanings and conclusions, i.e. the sense made, attached to, or imposed on a presentation or a first order reality based on one’s assessments, beliefs, and interpretations, e.g. a conclusion that ‘the room is crowded’. What constitutes a given situation, therefore, is determined by the response repertoire(s) of leadership sources (see ‘sensemaking’ arrow in ).

Proposition 5: Situation variety is a product of response repertoires which shape leadership sources’ sensemaking of and responses to situations, i.e. which functions to enact to what degree, when, and in what order. (See )

Leadership Effectiveness and Implementation Outcomes

Leadership effectiveness is evidenced in a variety of implementation outcomes based primarily on the affective, cognitive, and behavioural reactions of change recipients to the content, consequences, and process of change (Ford & Ford, Citation2012; Oreg et al., Citation2011; Oreg & Berson, Citation2019). Among these outcomes are readiness for change, intention to resist (Oreg & Berson, Citation2011), commitment to change (Herold et al., Citation2008), and evaluations of the change process, its leadership, and its success (Gilley et al., Citation2009; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005; Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, Citation2006; Wren & Dulewicz, Citation2005). In most studies, leadership effectiveness is determined by the strength of the relationship between specific leadership behaviours and implementation outcomes (Ford & Ford, Citation2012).

The law of requisite variety and contingency theories of leadership (Bass, Citation2008), however, indicate that leadership sources will be effective in dealing with situation variety to the degree that their responses are ‘functionally adaptive’ (Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011). By functionally adaptive is meant that responses are sufficient in dealing with the variety of situations encountered, i.e. they work, not that they are perfect or isomorphic fits to those situations. The 45o diagonal in indicates the set of points where the response repertoire of leadership sources effectively matches the variety in situations resulting in ‘good’ (i.e. effective or successful) implementation outcomes, i.e. requisite variety (Ashby, Citation1958; Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011). This relationship is indicated in where leadership effectiveness is shown as a product of the interactions between leader response repertoire and situation variety.

Boisot and McKelvey (Citation2011, p. 284) propose that matching response repertoire and situation variety on the diagonal () is functionally adaptive (i.e. works) only if it occurs within an adaptive frontier: ‘the region in which the system reaches the limit of the response budget it can draw on for the purposes of adaptation’. The adaptive frontier, which is indicated in by the line AB, indicates the depth and breadth of the response repertoire of a system, e.g. leadership sources. Outside of the AOB region, situations exceed the response repertoire of leadership sources, leading to errors in sensemaking (e.g. missing, misunderstanding, or misinterpreting information) and inadequate or inappropriate responses resulting in ‘bad’ or unfavourable outcomes (e.g. implementation failures).

Within the AOB region and above the requisite variety diagonal, leadership sources under-adapt relative to the situation variety they confront, using responses that are insufficient for effectively dealing with the situation. This occurs when leadership sources lack appropriate responses for situations or when they confront complex or novel situations that exceed their sensemaking capabilities, in which case only a portion of the data and information in the situation is processed and understood, leaving the remaining portions a puzzle they are unable to effectively address (Weick, Citation1979, Citation1983). Leadership sources limited in detecting and understanding deteriorations in social integration, for example, will not realize when it occurs (a failure of the monitoring function) and either fail to address it or interpret it as a failure of structuring and respond by enacting more structure. Below the requisite variety diagonal, leadership sources over-adapt, using response(s) that exceed what is necessary for addressing the situation, e.g. enacting more structuring or social integration than needed.

The dynamic nature of change implies that leadership sources will encounter some level of situation variety during the implementation of change that will result in changes to the leadership functions enacted and the degree, timing, and sequencing of their enactment. This suggests that effective leadership will be characterized by a configuration of enacted leadership functions depending on the nature, timing, and sequence of the situation(s) encountered. A different pattern of situations will elicit different configurations of the functions enacted, in terms of their degree, timing, and sequence. If this is the case, then leadership effectiveness is not simply the product of the extent to which leadership sources engage in a particular class (e.g. relations-oriented) or set (e.g. transactional) of leadership behaviours, but rather the configuration of the functions enacted. Since a variety of different responses may be functionally adaptive for various situations, leadership effectiveness may be characterized by different combinations of responses rather than a ‘one best’ or ‘universal’ combination (Doty et al., Citation1993; Ketchen et al., Citation1993; Meyer et al., Citation1993).

Leadership effectiveness and change implementation outcomes impact situation variety (see ‘impact’ arrow in ). Responses in one time period have political, symbolic, and substantive consequences that alter the context in which subsequent enactments can and will be taken (Denis et al., Citation1996; Denis et al., Citation2001). This is particularly true in complex changes where responses in one time period can reveal and create problems that were not foreseen and that need to be addressed in subsequent time periods (Amis et al., Citation2004). This suggests that the sequence of enactments is path-dependent where responses contribute to the situation variety that leadership sources subsequently encounter, constraining some enactments while creating opportunities for others. The configuration of leadership functions enacted during the implementation of change, therefore, will depend in part on the effectiveness of prior enactments, such that enactments that are effective in one aspect or phase of a change may not be effective in another (e.g. Battilana et al., Citation2010; Oreg & Berson, Citation2011).

Proposition 6: Leadership effectiveness and implementation outcomes are a product of the law of requisite variety in which the configuration of leadership function enactments is functionally adaptive to the situations encountered. (See )

Expanding Adaptive Frontiers and Response Repertoires

Leadership effectiveness and improvements in implementation outcomes occur as a result of an expansion in the response repertoire of leadership sources (Ashby, Citation1958) which expands the adaptive frontier, shown as moving from line AB to line CD in , (Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011). An expanded response repertoire means an expansion in sensemaking and responses, i.e. functional enactments, allowing leadership sources to see and address a greater variety of change situations with a larger variety of responses (Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011). Leadership effectiveness and implementation outcomes contribute to expansions in response repertoires through their effect on leadership sources, the behaviours used to enact functions, and the functions they enact (see ‘Inform’ arrow in ).

Adaptive frontiers and response repertoires can be expanded by increasing the differentiation, specialization, and complementarity of leadership sources and the functions they enact (Denis et al., Citation2001; Hodgson et al., Citation1965). Such expansions can be accomplished by expanding from focused to distributed leadership (e.g. Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991), by expanding the number of leadership sources involved (e.g. Gioia et al., Citation1994) and/or by changing the composition of leadership sources (e.g. Denis et al., Citation2001). Since co-performing leadership allows for participants to specialize in the enactment of distinct functions in complementary ways (e.g. degree, timing, and sequence), it has an increased ability to respond effectively to a variety of situations through behavioural integration than either focused or collective leadership sources. Although collective leadership sources may have sufficient differentiation and specialization in the functions they can enact, the absence of collaboration and coordination makes matching situation variety with response variety questionable and unreliable (Hodgson et al., Citation1965).

Adaptive frontiers and response repertoires can also be expanded by leadership sources learning from the effectiveness of their responses, in which they acquire relevant declarative memory (e.g. knowledge and facts) as well as procedural memory (e.g. skills and abilities) (Moorman & Miner, Citation1998). Zollo and Singh’s (Citation2004) research on bank acquisitions found that repeated practice was positively associated with the accumulation of tacit and explicit knowledge of how to execute acquisitions and achieve superior acquisition performance. Declarative and procedural memories, and the routines that contain them, are a product of the sequence of changes that leadership sources have experienced, the circumstances in which the memories are developed, and the outcomes realized (Moorman & Miner, Citation1998). In other words, the adaptive frontier of leadership sources source is shaped by the depth and breadth of their experience and effectiveness in leading change. Effective leadership sources with extensive and varied change experience are likely to have more distinctions for recognizing variety in change situations, and more responses for meeting that variety, than sources with limited experience and effectiveness.

Of course, ineffective leadership sources may not change either the configuration of leadership functions they enact or the behaviour and manner in which they enact them. Research on the escalation of commitment (Staw, Citation1981) and organization crises (Hedberg et al., Citation1976), for example, indicates that leadership sources can persist in courses of action that are ineffective. Since enactments in co-performing sources are the product of negotiation and re-negotiation among participants (Denis et al., Citation2001; Hodgson et al., Citation1965; Levinthal, Citation1997), behavioural integration and group dynamics such as groupthink (Janis, Citation1972) and other pressures to conformity, can impose constraints and limitations on changes in functions enacted and the behaviours for enacting them. Additionally, leadership sources that are effective in one arena (e.g. structuring), but not another (e.g. social integration), may persist in enacting functions in which they are effective (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991). In each of these cases, response repertoires and adaptive frontiers are unlikely to expand without replacing leadership sources or changing their composition.

Proposition 7: Response repertoires are modified by changes in leadership sources, the functions they enact, the behaviours they use to enact them, and the manner or style in which those behaviours are expressed as a result of leadership effectiveness. (See )

Discussion

Our goal here has been to provide a general integrative understanding of leadership in the implementation of change by seeing it as a functional phenomenon that can be engaged in by a variety of leadership sources over the duration of a change (). Rather than looking at leadership from the standpoint of something provided by a particular individual, e.g. ‘a leader’, we look from the standpoint of the change itself by considering leadership as a set of functions to be behaviourally enacted for successful change regardless of which leadership source(s) fulfils them. Any individual or group that engages in fulfilling leadership functions engages in leadership (Morgeson et al., Citation2010). From a functional perspective, effective leadership becomes an issue of requisite variety () where the configuration of leadership functions behaviourally enacted by leadership sources, i.e. the response repertoire, is sufficient to meet the variety of situations that those sources experience during the change. The dynamic interrelatedness among response repertoire, situation variety and leadership effectiveness indicates that leadership itself is dynamic and that leadership sources are impacted by leading, which can result in changes to leadership sources, the behaviours in which they engage to enact functions, and the configuration of the functions they enact. Leadership in the implementation of change, therefore, is inherently complex, dynamic and messy.

Leadership is Complex

Complexity in the leadership of change arises in part from leadership being provided by one or more leadership sources that can vary over the duration of change, from the focused leadership of a single individual to combinations of co-performing and collective leadership with varying degrees of collaboration and coordination in the leadership they provide (Denis et al., Citation1996; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Joffe & Glynn, Citation2002). Leadership sources can have different interpretations and understandings of a situation, particularly in cases of collective leadership where there is no collaboration or coordination, resulting in different responses for dealing with that situation (Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, Citation2006; Morgeson, Citation2005). As a result, leadership effectiveness and implementation outcomes will be a product of the interplay among the various enactments by various leadership sources (e.g. Denis et al., Citation1996; Denis et al., Citation2001; Rauch & Behling, Citation1984). These enactments may be complementary, thereby facilitating and supporting each other; redundant, in which case they may add nothing to or overemphasize the function(s) being enacted; or contradictory, offsetting or negating others’ enactments. Leadership sources at higher levels in an organization, for example, may constrain, suppress, or neutralize enactments by leadership sources at lower levels with highly structured planned changes or interventions that limit the discretion of lower leadership sources (Lyons et al., Citation2009; Van der Voet et al., Citation2014). Alternatively, higher level leadership sources can support lower level leadership sources by initiating fewer structured, emergent or organic changes, giving lower level leadership sources greater discretion (Van der Voet et al., Citation2014) and independence in the functions they enact. Finally, lower level leadership sources may resist the enactments of higher level sources, effectively neutralizing them (Ford et al., Citation2008).

Even in cases of co-performing leadership where responses are collaboratively coordinated, responses are a product of negotiation and renegotiation among participants with different perspectives (Denis et al., Citation1996; Denis et al., Citation2001; Gioia et al., Citation1994) and response repertoires. The different leadership sources involved, the configurations of leadership functions they enact, and the resulting implementation outcomes they produce all contribute to situation variety, which makes attributions for implementation outcomes problematic and makes it difficult for leadership sources to judge the effectiveness of, and thus to modify, their response repertoires. These factors make leadership more complex and less straightforward than is implied in studies where leadership is limited to the behaviour of a single individual, i.e. ‘the leader’, where outcomes are assumed to be the product of that individual’s behaviour.

Leadership in the implementation of change is also made complex by the observation that during the implementation of change, organizations need to continue some existing practices while they phase others out and replace them with newer ones (Czarniawska, Citation1997). This implies that change leadership and day-to-day leadership can occur concurrently, making the separation of their respective effects difficult to determine. If there are differences between the configuration of leadership functions enacted on a day-to-day basis and those enacted during change, then the complexity of leadership increases as leadership sources must navigate between the different demands. This is particularly likely where the leadership sources engaged with implementing change, e.g. transition teams (Duck, Citation1993), are different from those engaged in day-to-day leadership. Although numerous studies of leadership in the implementation of change borrow measures of leadership behaviours from traditional behavioural measures of leadership (e.g. Herold et al., Citation2008; Oreg & Berson, Citation2011), thereby assuming leadership in the implementation of change relies on the same behaviours as day-to-day leadership, other studies have found that different leadership behaviours are involved (Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005; Wren & Dulewicz, Citation2005). This difference suggests that the behaviours used to enact functions on a day-to-day basis and during change are different. These differences could offer one explanation for emergent leadership in which additional leadership sources emerge (creating or adding to distributed leadership) to enact those functions that are not sufficiently enacted by day-to-day leadership behaviours (Pescosolido, Citation2002). Furthermore, since day-to-day leadership may impact change recipients’ readiness for and reactions to change (Ford et al., Citation2008; Oreg & Berson, Citation2011, Citation2019), day-to-day leadership can be a complement to or neutralizer of leadership enactments during change, increasing situation variety and making leadership in the implementation of change more difficult. This implies that if we want to fully understand the dynamics of leadership during change, both day-to-day and change leadership behaviours should be considered, particularly when evaluating leadership effectiveness.

As the complexity of change increases, situation variety and the variety of responses required to match it also increase, likely exceeding the response repertoire of focused leadership sources. Consequently, additional leadership sources will be needed in order to expand the response repertoire to effectively address these situations (Fernandez et al., Citation2010; Pearce et al., Citation2007; Pearce & Sims, Citation2002). Since complexity increases ambiguity and uncertainty, the need for collaboration and coordination as well as differentiation, specialization, and complementarity among leadership sources also increases (Denis et al., Citation1996; Denis et al., Citation2001; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Hodgson et al., Citation1965), suggesting an increased need for, and use of, co-performing leadership sources (Ford & Ford, Citation2012). However, where co-performing sources are not forthcoming, or where they are ineffective, collective leadership sources may emerge. But even in cases of simple changes, leadership is likely to involve occasions of distributed leadership, for, as Gronn (Citation2002a) indicates, even in the most extreme cases of focused leadership, e.g. dictators, distributed leadership still occurs. Although such occasions of distributed leadership may be infrequent, limited in scope, degree, and duration, e.g. interruptions (Okhuysen, Citation2001), they nevertheless provide for the enactment of complementary leadership functions in support of those provided by focused leadership sources (Gersick, Citation1988, Citation1989; Okhuysen, Citation2001). Assuming implementation outcomes are the sole product of focused leadership sources, therefore, runs the risk of overstating their impact while understating the totality of leadership provided. Pearce and Sims (Citation2002), for example, found in their study of change management teams that formal positional leadership (i.e. focused leadership) and team leadership (i.e. distributed leadership) each explained significant and unique amounts of variation in team performance, but that team leadership was a more useful predictor of team effectiveness than focused leadership. As a result, they conclude that the two types of leadership are complementary. Had they limited their study to only vertical leadership, they would have missed the contribution and significance of distributed leadership, resulting in an understatement of the leadership provided.

Different configurations of leadership functions enacted, and the degree, timing, and sequence of those enactments also increase the complexity of leadership. Rather than singular causal relationships, configurations of functions enacted imply complex and nonlinear relationships between leadership enactments and implementation outcomes. Factors that are causally related in one configuration may be unrelated or even inversely related in another (Fiss, Citation2007; Meyer et al., Citation1993). Configurations of functions enacted that are effective in one phase or stage of change may not be effective in subsequent phases or stages. Similarly, configurations that are effective in one organization with one type of change may not be effective in another organization dealing with the same type of change. Such differences in the effectiveness of the configurations of leadership functions enacted raise the possibility of leadership equifinality in which ‘a system can reach the same final state from differing initial conditions and by a variety of paths’ (Katz & Kahn, Citation1977, p. 30). Gersick (Citation1989), for example, observed that although all teams facing a performance deadline confront transition issues, how they resolve them depends on the different situations in which they started, indicating that different configurations will be effective. This does not mean, however, that any and all possible configurations are likely (Meyer et al., Citation1993), particularly if functional enactments must be complementary to be effective. Rather, it implies that there is a limited set of equally effective enactment configurations that can be attained through different leadership sources. In this regard, it may be that even though leadership sources encounter many of the same issues during change, e.g. transitions between phases or stages, the configuration of functions enacted in the resolution of those issues and the specific behaviours used to enact them in one setting may not successfully enact the same function(s) in other settings (House & Aditya, Citation1997). Accordingly, research is needed to determine what configurations of functions are enacted, their effectiveness, and whether they are related to or part of broader organizational configurations (Meyer et al., Citation1993).

Leadership is Dynamic

As shown in , leadership dynamics are reflected in the interrelatedness of situation variety, response repertoires and leadership effectiveness which can contribute to changes in leadership sources, the behaviours used to enact functions and the functions enacted as leadership sources learn what works and what doesn’t in their response repertoires (e.g. Denis et al., Citation2001; Gioia et al., Citation1994; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991; Joffe & Glynn, Citation2002; Lyons et al., Citation2009; Pearce & Sims, Citation2002). A constellation of leadership sources can evolve from focused leadership to more complex combinations of co-performing and even collective leadership where co-performing sources work collaboratively and collective sources, e.g. emergent leadership sources, work independently. The result is a dynamic interplay of enactments that impact and change the configuration of functions enacted, the implementation outcomes realized, and situation variety. Changes in response repertoires occur where leadership sources learn from the effectiveness of their enactments via implementation outcomes, and make modifications in the behaviours used to enact functions as well as the degree, timing, and sequencing of enactments (Schakel et al., Citation2016).

Research on action teams (Klein et al., Citation2006) indicates that the locus of leadership, i.e. the source(s) of leadership, changes with the situation. Even though there may be a formally designated ‘leader’ who is responsible for the performance of the team, the nature of events, e.g. their urgency and severity, influences the response(s) needed and who provides leadership. In these cases, the formally designated individual may only get involved when others are unable to provide an appropriate or sufficient response. Through delegation, formally designated leaders (focused leadership) can create distributed co-performing leadership.

The dynamics of leadership are also reflected in the interplay among leadership sources in terms of the functions they enact and whether those functions are complementary, redundant or contradictory. These dynamics, in terms of the degree, timing and sequence of enactments, indicate that using average ratings on ‘leader behavior’ scales, such as those obtained in cross-sectional studies, is insufficient for understanding them. If we are interested in effective leadership in the implementation of change, as compared to the behaviour of individual leaders, then we need to expand our understanding of leadership and our approach to its study. Although others have pointed to the need for longitudinal research (e.g. Ford & Ford, Citation2012; Pettigrew, Citation1990; Van de Ven & Huber, Citation1990), these calls have been largely ignored.

Learning is another factor that makes leadership dynamic. Leadership sources can learn from leading, expanding their response repertoires as they learn the distinctions that allow them to make sense of different change situations and acquire, modify, and reinforce the procedural and declarative memory that shapes and informs their response repertoire and the degree, timing, and sequencing of the functions they enact. As a result, we would expect leadership effectiveness to improve with experience in leading change. Leadership sources, however, can be subject to the Einstellung effect, which is the tendency to persist in the same approach to a problem or series of problems, whether or not that approach is effective. Such an effect may occur when leadership sources believe they ‘have seen it all’ (Boisot & McKelvey, Citation2011) and no longer feel it is necessary to modify their responses.

Leadership is Messy

There is a risk in assuming, based on the framework presented here (see ), that leadership in the implementation of change is a rational process in which leadership sources make sense of situations and then choose and enact the appropriate configuration of functions. Change, particularly complex change, is messy emotionally (Huy, Citation2002) and politically (Denis et al., Citation2001) and so is its leadership (Mintzberg, Citation1973). Sensemaking is not straightforward and can result in conflicting and competing understandings that, in the case of co-performing leadership, must be worked out through negotiation and renegotiation (Gioia et al., Citation1994). Sensegiving can also fail, resulting in misunderstandings and resistance by both leadership sources and change recipients, thus requiring additional sensemaking (Ford et al., Citation2008; Gioia et al., Citation1994). Further, emotional reactions to change (Huy, Citation2002) contribute to situation variety and make changes ‘messy’. Responses that are ineffective and events that call into question prior responses (Amis et al., Citation2004) can contribute to feelings of resentment or cynicism (Dean et al., Citation1998) as well as resistance.

Leading change can cost leadership sources their position and their credibility (Denis et al., Citation2001) and call into question their authenticity (Eriksen, Citation2008). Leadership in general evokes power stress (Boyatzis et al., Citation2006), which stems from the exercise of influence and a sense of responsibility, as well as stress that stems from the exercise of self-control. This stress can have an adverse psychophysiological impact on leaders, resulting in ego depletion (Kahneman, Citation2011), negative affect, loss of energy and motivation, reduced effectiveness, burnout, and an increased likelihood of succumbing to an urge to quit. Leadership, therefore, is less sustainable as leadership sources, particularly focused leadership sources, have difficulty remaining engaged and maintaining the mental, emotional and perceptual processes that enable them to be effective (Boyatzis et al., Citation2006; Kahneman, Citation2011). This implies that leadership sources involved in change, particularly long-term, large scale, and contentious change, will have difficulty sustaining their self-control (Boyatzis et al., Citation2006), resulting in inconsistent, inappropriate, and ineffective response repertoires and unfavourable implementation outcomes. In this respect, it is worth noting that Joffe and Glynn (Citation2002) found co-performing leaders needed more support from consultants than was anticipated due to the sensitive (emotional and stressful) nature of the situations they needed to address.

Leadership Effectiveness is Two Dimensional

Interest in leadership in the implementation of change is ultimately an interest in producing successful change. The satisfaction of this interest begins with an understanding of what we mean by ‘successful change’ and, by implication, effective leadership. The functional perspective taken here holds that effective leadership results when what is required for both task accomplishment and group integration and maintenance is fulfilled. Thus, there are two outcomes that constitute successful change: the accomplishment of the change itself and the maintenance of the social system undergoing change. Successful change and effective leadership constitute a both/and condition, rather than an either/or condition, i.e. leadership successfully implements the change and leaves change recipients well (e.g. Cameron, Citation2004). If one outcome is achieved, but not the other, then leadership did not get its job done (Hackman & Wageman, Citation2005). In their review of empirical research on change leadership, however, Ford and Ford (Citation2012) observed that no studies considered both task accomplishment and group integration and maintenance over the duration of a change. Although some studies did consider the relationship between different types of leadership behaviours and various outcome measures of change implementation and group maintenance, those measures were considered separately or were limited to only one phase of change. Furthermore, task accomplishment was not measured objectively in these studies (with the exception of Kavanagh & Ashkanasy’s, Citation2006 study) but was measured based on perceptual assessments (Ford & Ford, Citation2012), meaning that people could perceive a change to be successful without regard to the factual success or failure of the change.

The failure to consider both task accomplishment and group maintenance outcomes over the duration of an entire change has resulted in an incomplete and inconsistent view of leadership in the implementation of change (Ford & Ford, Citation2012). Rather than a comprehensive understanding, we end up with a series of findings patched together that focus on different outcomes during different phases of change from different leadership sources (Ford & Ford, Citation2012; Oreg & Berson, Citation2019). Although this allows researchers to make general claims, e.g. that leadership has an impact on change (W. Burke, Citation2008; Lyons et al., Citation2009), it does not provide an understanding of the complexity, dynamics, and messiness of leadership in the implementation of change.

Limitations and Implications