ABSTRACT

This article examines organizational identification construction in mergers and acquisitions (M&As). The majority of existing studies have focused on antecedents and outcomes of post-merger identification (PMI) in Western contexts. While more and more Chinese cross-border M&As are taking place, how Chinese employees construct PMI remains underexplored. We adopted a qualitative case study approach to investigate how Chinese managers construct PMI after acquiring a European company. As the main contribution, we introduce the concept of agile organizational identity (AOI), wherein agility is a central, enduring and distinctive characteristic of an organization, i.e. ‘who we are and who we want to be’. Our findings reveal that AOI is leveraged by Chinese managers to deal with their perceived inferior status, help them cope with the change and contribute to the construction of a strong PMI. We believe that our study provides a new perspective on how employees can effectively cope with organizational change while maintaining a sense of identity continuity.

MAD statement

This article examines organizational identification construction in mergers and acquisitions (M&As). We provide novel insights by introducing the agile organizational identity (AOI) concept, wherein the agility is a central, enduring and distinctive characteristic of an organization, i.e. ‘who we are and who we want to be’. To maintain such a pre-merger identity after M&As, people strive to continue changing as change is the continuity. Thus, psychological bonds between an employee and the employing organization do not become weaker. As agility is incorporated in the organizational identity, AOI helps employees to cope with the low status of their organization, accept organizational changes, and identify with the post-merger organization. Organizational leaders might want to foster AOI in order to successfully conduct strategic change initiatives.

Introduction

Organizational identity and identification have become key concepts in organizational studies, and particularly in change management literature. These concepts have been linked to employees’ reactions to organizational change in general (Kira et al., Citation2012; van Dijk & van Dick, Citation2009), to organizational bias due to status asymmetries (Lipponen et al., Citation2017), and to resistance to different strategic organizational interventions (Vaara & Tienari, Citation2011). Organizational identity is defined as what is considered by the members to be the central, distinctive and enduring characteristic of an organization (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985). Organizational identification refers to ‘the perception of oneness with or belongingness to the organization’ (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989, p. 34).

M&As often involve dramatic organizational changes which might disrupt and threaten employees’ sense of organizational identity and identification (Gleibs et al., Citation2008). Thus, after M&As, the members often need to reconstruct their organizational identification to develop a sense of belonging to the new, post-merger organization (Terry & O’Brien, Citation2001). Moreover, one of the pre-merger organizations will typically be superior to the other one in terms of financial power, competence, or technological competitiveness. The perceived status asymmetry is an important determinant of the post-merger identification (PMI). There is research evidence indicating that the post-merger identification is largely influenced by the high-status organization (Lupina-Wegener et al., Citation2014). Employees who perceive themselves as the ones from the lower status organization tend to have a weaker PMI (Amiot et al., Citation2012). Weaker PMI, in turn, is detrimental to the success of M&As, leading to low job satisfaction and high turnover intentions (van Dick et al., Citation2006).

In this paper, we aim to investigate Chinese cross-border M&As which seek to gain a competitive position in global markets by acquiring Western companies (Deng, Citation2013) and, consequently, improving their technology and brand (Zou & Ghauri, Citation2008). However, Chinese companies often face challenges when they acquire Western companies, and they therefore grant the foreign target a high level of autonomy (Liu & Woywode, Citation2013). We argue that the asymmetry of technological know-how and branding might trigger a perception among Chinese members that they have an inferior status. The latter might impede the construction of a high PMI.

We define PMI construction as a process of building up an organizational identification after M&As (Ashforth et al., Citation2008). Given that PMI is under investigated in the context of Chinese M&As, in this paper we will focus on the following research question: How do Chinese managers construct their PMI after acquiring a European company? We conducted a qualitative in-depth case study in a Chinese acquisition of a European, innovation-driven, manufacturing firm. The data collection began with three pilot interviews and was followed by 35 interviews in the Global Headquarters (HQs) in China. We used a grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008) to develop a conceptual framework of the process of PMI construction. Our findings contribute to the organizational change literature and the social identity theory (SIT) by elaborating on the concept of agile organizational identity (AOI) which is distinct from organizational agility. The latter provides a material reality that facilitates the experience of AOI as shared by members of a group or organization.

Theoretical Background

Post-Merger Identification in M&As

The construction of PMI is grounded in the social identity approach (SIA). SIA comprises social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986) and self-categorization theory (SCT) (Turner et al., Citation1987). SIT proposes that people define themselves or derive large parts of their self-esteem from their membership in social groups. SCT explains how and when people will define themselves as group members in order to better understand individual and group behaviour. Organizational identity is defined as what is considered by organizational members to be the central, distinctive and enduring characteristic of an organization (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985), i.e. ‘who we are as an organization’. Organizational identification refers to ‘the perception of oneness with or belongingness to the organization’ (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989, p. 34) and to ‘the extent to which people define themselves as members of a particular group or organization’ (Haslam et al., Citation2003, p. 360). Accordingly, organizational identification emphasizes the strength of the link between the organizational identity and the members of the organization such that their behaviours are oriented towards or are structured by the identity of their organization.

Organizational identification is important when dramatic changes occur, such as in M&As. A longitudinal qualitative case study on a public sector merger conducted by Kira et al. (Citation2012) reveals that changes lead to employees’ perceptions of misalignment between the nature of their work and organizational identity. In the same vein, van Dijk and van Dick (Citation2009) in their mixed methods investigation of a merger between law firms show that a threat to work-based, pre-merger identity leads to a weak PMI. PMI reflects employees’ organizational identification after M&As and it helps explain employees’ job satisfaction, post-merger cooperative behaviours and post-acquisition performance (Ullrich & van Dick, Citation2007). Correspondingly, low levels of PMI may lead to organizational conflicts and turnover intensions (van Dick et al., Citation2006).

What are the determinants of employees’ PMI? van Knippenberg et al. (Citation2002) found that for employees from a dominant organization, pre-merger identification is positively related to PMI because of the sense of continuity between past and present. In their qualitative case study, Ullrich et al. (Citation2005) reveal that the sense of continuity comprises both an observable continuity, i.e. between pre and post-merger identification, and a projected continuity, i.e. employees’ understanding of where their organization is going and how they can contribute. Employees of the dominant organization often perceive the post-merger organization as a continuation of their pre-merger organization, whereas members of an acquired organization tend to experience a lower observable continuity (Lupina-Wegener et al., Citation2014).

These insights into PMI construction have mostly been obtained in Western M&As, but extant theoretical evidence might not apply to other cultural contexts. A meta-analysis by Lee et al. (Citation2015) reveals that organizational identification has stronger effects on work behaviour in a collectivistic culture than in an individualistic one because an individual’s self-concept is constructed in a collective manner. Moreover, a quantitative investigation by Chung et al. (Citation2014) found that change after an acquisition can be supported by Chinese employees if they are clear about the benefits for the collective, rather than focusing on ‘me issues’. The question that arises is whether pre-merger identification, status and continuity play the same role in influencing employees’ PMI in another context such as in Chinese cross-border M&As.

Post-merger Identification Construction in Chinese Cross-Border M&As

Chinese acquisitions have dramatically increased in recent years and reached 57 billion US dollars in 2019 (J.P.Morgan, Citation2019). Since China has a history of gaining cost advantages by sacrificing the quality of their products, the Chinese acquirers target well-known Western companies as a springboard to acquire strategic resources, i.e. sophisticated technology and recognized brands (Luo & Tung, Citation2007). These acquisitions can help Chinese firms ‘catch up’ in global markets. Due to less advanced management practices and lower levels of technology, changing from a local to a global firm might require an in-depth identification change (Mathews, Citation2006).

In the Chinese context, scholars mainly have focused on the post-merger integration strategy as a critical antecedent of a successful acquisition (Muralidharan et al., Citation2017; Zheng et al., Citation2016). Unlike traditional integration, transformation or assimilation merger patterns adopted in Western acquisitions (Mottola et al., Citation1997), Chinese companies grant autonomy (Lupina-Wegener et al., Citation2020). In a qualitative study, Liu and Woywode (Citation2013) found that despite a high potential for synergy, Chinese acquirers choose a ‘light-touch’ integration pattern wherein managerial autonomy is granted to the acquired firms and the acquirers are willing to change their own organizations.

In this paper, we will investigate how Chinese members of the acquiring organization, with a perceived inferior status, construct their PMI. We will focus on the following research question: How do Chinese managers construct their PMI after acquiring a European company?

Method

We employed an inductive case study, as it is most appropriate for grounded theory building and answering ‘how’ questions related to complex processes (Gehman et al., Citation2018). In our study, the process of PMI construction was highly complex due to cultural differences and dramatic changes in terms of organizational structure, processes and identification. We adopted a single case study to explore Chinese employees’ PMI construction. The case was unique and revelatory for two reasons (Yin, Citation2009). First, Alpha, the Chinese acquirer in our case study, was described by Western media as a typical Chinese ‘copycat’ company. To our knowledge, scholars have not yet investigated how Chinese employees perceive their organization under the ‘copycat’ label, nor their identification construction after the acquisition of a European, technology-based, highly recognized firm. Second, Alpha acquired a premium B2C brand, which caught much attention in the industry and media. The extreme contradictions between negative comments and positive results of the acquisition made this case unique for us. We were interested in how a low-end firm became an international player, and how Chinese employees constructed their PMI.

Research Setting

Alpha-Holding is a Chinese listed, privately-owned Multinational Enterprise (MNC) which consists of domestic and international divisions. It operates in an industry where technological advantages are of a core competitive advantage. Alpha-China is Alpha-Holding’s domestic division, which had been manufacturing low-end products characterized by low quality, low price and inferior technology. As competition in the Chinese manufacturing industry increased, Alpha-China started to lose its market share. To improve the quality and brand of Alpha-China’s products, Alpha-Holding acquired a European company called Beta (month 1). Despite Beta’s history of innovation in technologically advanced products and being a recognized premium brand, it found itself on the brink of bankruptcy. In remainder of this manuscript, we will refer to Alpha-China and Alpha-Holding as Alpha.

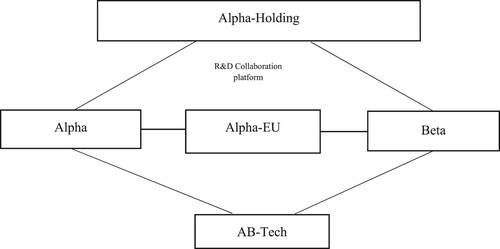

To defend Beta’s brand value, Alpha gave Beta autonomy to operate. In Month 43, as a European subsidiary of Alpha, Alpha-EU was created next to Beta to encourage knowledge transfer from Beta. describes the key phases in the integration, together with the key events. Alpha-EU functioned as a bridge between Alpha and Beta. The direct collaboration between Alpha and Beta might have triggered threats for Beta managers, which could have obstructed knowledge transfer. Conversely, the creation of Alpha-EU allowed Alpha to launch a new brand, and it provided them a chance to collaborate with Beta without threatening the European workforce. Financed by Alpha, managers from Alpha and Beta conducted joint projects based in Alpha-EU. While cooperating with Beta, Alpha-EU learned about technology from Beta and then transferred it back to Alpha. Thus, Alpha-EU was seen as an ‘invisible tube’ for knowledge transfer. In addition, cultural differences were less of an issue in the Beta and Alpha-EU collaboration, because Alpha-EU recruited many European engineers, and many from Beta. Beta also was highly successful, and with Chinese financial and strategic planning support, the company became a leading global player in the industry.

Table 1. Chronological description of the key events.

In Month 80, Alpha successfully launched Alpha-EU’s innovative products under the new brand. To further formalize the synergies between Alpha and Beta, i.e. cost efficiency and technology collaboration within two organizations, a second, new organization, AlphaBeta-Tech (AB-Tech), was created to Alpha in China. AB-Tech was owned jointly by Alpha and Beta, and both companies had equal shares. In AB-Tech, Alpha and Beta managers began to collaborate directly for the first time, rather than via an intermediary organization – Alpha-EU. As is evident from , it took Alpha eight years to integrate Beta ().

Round 1: Procedure and Data Analysis

Month 88, we gained access to the company to conduct interviews. The qualitative data were conducted by the first author who is Chinese, and therefore a grasp of the context was not lost due to faulty translation or insufficient understanding of the Chinese culture. The initial goal of the interviews was to understand how Chinese managers experienced change resulting from the acquisition. Our interview guide consisted of self-introduction, collaborative challenges, dominance (decision making), know-how transfer, identification change. We began by conducting three pilot interviews, which revealed that a new joint organization (AlphaBeta-Tech; AB-Tech) would be created in Month 95 in China and which would imply further changes. As changes significantly influence identity and identification, we started the data collection soon after the creation of AB-Tech. We conducted 19 interviews with Chinese managers from Alpha, all of whom had experience of working with or in Alpha-EU. The interviews lasted approximately 60 min each. provides an overview of the interviewees.

Table 2. Overview of the interviewees.

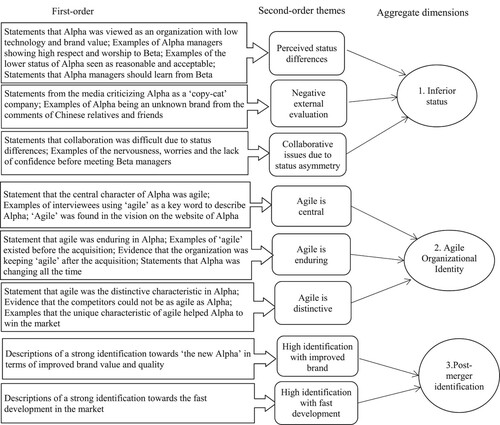

We adopted an inductive grounded theory approach to analyse our data (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017). We began the first-order, open coding by reviewing and assigning initial texts including words, phrases, sentences or paragraphs to different categories. We used in-vivo codes (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008) which were used directly by the interviewees, such as ‘we are agile’, ‘we are changing’. If the in-vivo codes were not available, we used summary phrases to name the categories. Based on the categories generated from first-order coding, pattern-matching coding was adopted to compare our data with existing theories (Miles & Huberman, Citation2019). Common themes were used to link together data fragments from differing but related categories developed in open coding (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Emerging relationships among codes and theoretical linking were recorded in memos. Sequential and interactive relationships were traced, and the original static coding dimensions were thereby transformed into the process of PMI construction. For example, we used the theme of ‘perceived status differences’ as a second-order code. Due to major technological asymmetries, Chinese managers saw themselves as ‘students’ of Beta managers. They frequently evoked early acquisition experiences, such as their inferior status in this acquisition. Subsequently, collaborative conflicts emerged from our data, and we were intrigued by Alpha’s positive reactions towards the conflicts in spite of experiencing an inferior status. Interviewees described their organization as ‘agile’, with changes being normal for them. This was a critical point in our theorizing: Chinese managers seemed to leverage their organizational agility in adapting to organizational changes. We found that the agility they described could be included into the ‘central’, ‘enduring’ and ‘distinctive’ characteristics of Alpha, which was aligned with the definition of organizational identity. This type of AOI was leveraged when interviewees were faced with changes during post-merger managerial interventions (i.e. the creation of Alpha-EU and AB-Tech). They claimed that these dramatic organizational changes provided them opportunities to learn from Beta, to improve, and to build a strong PMI.

We developed the emergent framework by placing similar themes into more abstract dimensions and then building relationships among the different dimensions (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017). In our framework, we depict the relationship within these three dimensions of inferior status, agile organizational identity and post-merger identification.

Round 2: Procedure and Data Analysis

In the second round of data collection, we aimed to further explore the concept of AOI and how it was leveraged to construct PMI. We adopted multiple sources of evidence to test the construct validity (Yin, Citation2009) of AOI and we conducted 13 semi-structured interviews with Chinese senior managers in month 101. Interviews lasted approximately 60 min each. In addition to the interviews, we gained access to public and private archival data. The data included the websites of three organizational entities (Alpha, Alpha-EU and Beta), observations, peer-reviewed papers about the Alpha-Beta acquisition, and media articles related to Alpha’s strategic, operational and cultural aspects. Furthermore, one of the authors conducted an intensive observation during the second round of data collection. For one week, she stayed full time at Alpha upon an invitation from one of our key informants. Specifically, she took notes and photos of the slogans hanging in Alpha HQs in China. She attended Alpha managers’ meetings with their Beta counterparts so she could observe the interactions and discussions. She also conducted informal talks with Alpha managers after the meetings, during lunch or dinners. Being bilingual – Chinese and English, she was able to gather unique insights.

In addressing the conceptual framework concerning AOI and PMI, which emerged in the first round of the data analysis, we asked several questions concerning how Chinese managers perceived collaboration and relevant managerial interventions after the acquisition, and how they perceived their post-merger organization. These questions provided us with an opportunity to investigate what Chinese managers thought about who they were as an organization, and whether they perceived and mentioned agile as a central, enduring and distinctive characteristics of their organization. The questions helped us to further explore the place of ‘agility’ in Alpha managers’ organizational identity and how AOI was leveraged during the changes. We asked questions, for example, about managerial interventions after the acquisition, experience of the changes, and the PMI.

Next, we analysed the data based on the structure which emerged in the first round of data analysis. We specifically looked at the framework including first-order, second-order and third-order codes which emerged from round one data. We also reviewed the texts from round two data to see whether they could be included in the existing codes, and if not, we generated new codes for the data. We went back and forth between first-order codes and second-order themes until no new themes or codes emerged. We refined our coding categories and the conceptualization of relationships among the variables.

Multiple data sources (interviews, observations, intranet, press articles, off the record discussions) made it possible to triangulate the results and ensure construct validity. It was particularly important for us to understand the events in the acquisition, and secondary data sources served as a significant source of triangulation to understand events and to mitigate possible retrospective biases in interviews (Miles & Huberman, Citation2019). Moreover, in order to mitigate bias during the data collection, we contacted highly knowledgeable informants (Kumar et al., Citation1993) who came from different departments and who had had intensive interactions with Beta. We conducted off the record discussions and verified emerging findings with our key informants. We ensured internal consistency by working jointly on data analysis and agreeing on the emerging patterns and concepts in light of SIT.

Results

displays a coding scheme of our data structure of the findings. It demonstrates three main dimensions which emerged from our data analyses, as well as their constituent second-order themes and the first-order concepts. It describes the dimensions relating to the process of how Chinese managers construct their PMI.

Inferior Status

Perceived Status Differences

Despite Alpha products having dramatically improved after the acquisition, our interviewees still remembered the low brand value and technology of ‘Old-Alpha’ products, i.e. Alpha before acquiring Beta. Our interviewees often recalled their experience during the early stage of the acquisition. For example, Beta was worshipped as their ‘Goddess’ for its long history, advanced technology, high brand value and strong global presence in the market. Conversely, the interviewees perceived Alpha as a young, domestic company with a low level of technology and an inferior brand. There was a considerable knowledge asymmetry between the two organizations. The Chinese managers emphasized that at the early stage of integration, they had had difficulty understanding their European counterparts, not only in terms of the language, but also knowledge of technology, processes and managerial practices. Until then, there were convinced that they were ‘inferior’ in comparison to Beta. A high respect for Beta was evident from the testimonies provided, for example:

We (Alpha) admire Beta a lot, we are even envious of them in terms of technological know-how. We tell our employees, if you work hard, you will have a chance to work at Beta in the future. We take the opportunity to work at Beta as a reward.

Negative External Evaluation

The low status of ‘Old-Alpha’ was also reflected by ‘significant others’ outside of Alpha and Beta. First, in Chinese and international media, Alpha was portraited as a copycat company and representative of Chinese inferior know-how, low quality and lack of respect for international property rights. For instance, in the headlines of an international newspaper, a journalist commented on Alpha’s product as follows:

‘Alpha-machine’ (cannot reveal the product name) is a copycat of X (cannot reveal the name of the famous Western manufacturer); it must be made in China! (…) Chinese companies have a reputation for copying foreign classics – sometimes leading to legal action.

At that time, my classmate asked me why I studied manufacturing but worked for a wine company (the name of a popular wine brand is pronounced similarly to the Alpha brand)?.

Collaborative Issues

Alpha managers lamented that Beta managers had an ‘issue’ with being acquired by a Chinese company from a low-end market and of inferior technological know-how. European counterparts looked down at Alpha, they were not eager to collaborate with Alpha and were concerned about protecting their intellectual property. Our interviewees strongly admired Beta’s expertise and they were ashamed of their inferiority. To earn Beta colleagues’ respect, Chinese managers sought to be well-prepared in terms of language and questions before communicating with the Europeans who despite these efforts, remained ‘closeminded’ and ‘difficult to collaborate with’. For instance, one interviewee recalled:

I was sent to Beta to talk about a problem with our product. Before I set off, I had to prepare the questions very well, but my heart was still beating fast and I was very nervous!

Agile Organizational Identity

In light of the inferior status described above, post-merger integration between Alpha and Beta took place over time in three subsequent phases: separation, indirect integration (i.e. Alpha-EU), integration (the creation of AB-Tech); c.f. which describes the integration phases. Chinese managers experienced increasing organizational changes during the acquisition. In the early phase, the two organizations kept running their businesses independently with their own management teams. A new organization, Alpha-EU, was created only three years later as a bridge to connect Beta and Alpha. Alpha-EU brought about dramatic changes in the Chinese employees’ daily work. One interviewee recalled:

After the creation of Alpha-EU, we were faced with lots of changes, we were allocated to two positions with respective responsibilities both in Alpha and Alpha-EU … that brought us lots of work.

Agile is Central

In contrast, Alpha managers – in the low-status group – frequently claimed that their organization was able to thrive with these changes, as Alpha was an ‘agile’ organization. Furthermore, they stated that Alpha’s central characteristic was ‘agility’. For instance, some interviewees described Alpha with the word ‘agile’:

If I could choose one word, I would choose ‘agile’ to describe our organization.

On Alpha’s website its vision statement included:

We are evolving in fast-changing global conditions; Alpha has to be agile and embrace the changes that are happening all around us.

Alpha was an organization which developed very fast, we could react to different situations very fast (agile), and we could launch products very fast.

The success of Alpha’s acquisition of Beta is not mysterious, it relies on the support of the Chinese market … and Alpha’s agility.

Only by responding to changes, actively and quickly, can we keep pace with the fast-changing environment and strive for greater space for survival and development.

Agile is Enduring

In addition, ‘agile’ was perceived as an enduring characteristic of Alpha. For instance, Chinese managers claimed that this ‘agile’ DNA existed in Alpha before the acquisition. One of our interviewees mentioned:

I would say that agile is the characteristic of the company (Alpha) itself. It’s not because of the acquisition or Beta that we became agile.

It changed a lot after the acquisition. In fact, it kept changing … Alpha was more like an Internet company. So, we are changing all the time … For instance, Alpha-EU was initially created as a platform for a small collaborative project; then it became an informal joint organization based in China; finally, it became Alpha-EU, a European subsidiary of Alpha. There were lots of frequent changes like this … we would like to adapt to different situations.

We didn’t know how to do X – but they (Beta) knew. Alpha, we didn’t know. We tried to learn from them, built the new organization, new process, new standard and new templates, and new governance structure, meeting structure, everything.

From the perspective of the domestic market … we keep changing … It was just like what I had said to you. In our collaboration, Alpha undoubtedly learned the standardized development process from Beta, these areas such as the quality awareness, etc. are enhanced. That is a big leap.

Agile is Distinctive

Notably, ‘agile’ was claimed to be the soul of Alpha, which distinguished it from competitors. In comparison with well-established companies in the industry, Alpha had little advantage in terms of technology and brand, so they tried capturing the fast-changing market through unique organizational agility. For instance, one of our interviewees claimed that:

In fact, as a private company, we are gradually seizing and occupying the market. To occupy the market and win the competition against other companies in the industry, we have to be agile and react to the market in a fast way.

When an industry or a market is involved in fast competition, the first thing for a company like us to do is to seek to survive. In order to capture the market quickly, the first step to survive is to be agile. Yes, we must develop rapidly to occupy the market.

If customers say I need something like this, then my manager will ask the engineer to change it right now, and it can be changed within a very fast time. At the end of the day, the user is very happy. Users realize that Alpha can do the things they want very quickly. If you go to any company, you go to another company, you go to Beta, it's impossible …

In the manufacturing industry, there tends to be a number of hierarchical levels within an organization, which can lead to bureaucracy. This means that many companies might lose their organizational agility … However, in Alpha, we were very agile. For instance, we didn’t have many hierarchical levels, thus, our organization could react to the market rapidly … But foreign companies tended to set up their organizational structures from the perspective of professionalism, thus, they were lacking of this organizational agility.

Yes, it was okay (for the frequent changes). I think that was okay, because Alpha could deal with these everyday changes. Changing was the main topic of our organizational lives.

In fact, we have the ability to change. We were agile enough. From my point of view, I can make a conclusion: if we can’t have this kind of ability, we cannot survive anymore, basically the company will be over.

Post-Merger Identification

High Identification with Improved Brand

Ten years after the acquisition, Alpha had made significant progress and had become one of the key players in the industry in line with the Chairman’s vision and strategy to get there. Learning advanced technology from Beta via Alpha-EU helped Alpha get rid of its poor image and poor quality. Our interviewees strongly identified with the vision of becoming a recognized brand in the global market and identified with their high-quality products and sophisticated technology. Alpha launched new products in Alpha-EU to differentiate itself from the local brand. Most Alpha managers were proud that Alpha had captured a larger part of both the domestic and international markets. Moreover, their technologically advanced products received numerous awards and enhanced Alpha’s reputation, which made Beta’s acquisition a success, echoed in the European press.

After the acquisition, Alpha interviewees referred to their organization as ‘New-Alpha’ with a stronger vision. They went from being an inferior brand to being a benchmark on the Chinese market and a rising global star. Alpha was becoming a highly promising entity for employees and Chinese managers who identified with the ‘New-Alpha’:

We are proud of the development of Alpha, from ‘Old-Alpha’, which was laughed at and unrecognized, to a benchmark in the market, we are so proud of Alpha; you would feel so proud when you told people that you worked for Alpha and Alpha-EU, I am proud that I experienced this period and that I am one of those who contributed to this.

High Identification with Fast Development

Chinese managers identified with the post-merger organization in terms of fast development due to Alpha’s speed and organizational agility. Indeed, the organization was described as a highly competitive company which was more agile and efficient than their competitors. One of our informants said:

What I am most proud of … in fact, is that every one of us who is in the industry hopes to see a local brand that can firstly occupy the Chinese market, then go into the world or different markets. I think this is a dream of many people. In fact, we are still chasing this dream, but I believe that one day we will realize it. Because it is indeed that we find Alpha … its culture, and the speed, the flexibility, there are not many companies that can keep up. Even some mature companies, they can't keep up.

To work hard and expand efforts for the team to create value, this is a thing that I am very happy to do. Since my appointment in 2010, I have really witnessed the development of Alpha. Correct, this is a type of rapid development. Yes, up to date, just like the topping of the chart for last year’s sales, I felt very proud.

It shows that Alpha has indeed produced its own business card made in China with a high reputation. In my opinion … when you mention Japan in the industry, it is known as A company and B company (good Japanese brands in the industry). When you mention Korea, it is C company (good Korean brand in the industry). I hope that, in the future, when you mention China, people will mention us, Alpha.

Discussion

PMI has been shown in extant literature to be a relevant antecedent of successful M&As (Ullrich & van Dick, Citation2007). However, how Chinese organizational members construct their PMI after acquiring a European company remains under investigated. Our qualitative data analysis confirms that Chinese employees experience a sense of inferior status related to the asymmetry of technology and brand image. In addition, they experience resistance coming from the European members of the acquired organization. Our interviewees consider this resistance to come in the way of the post-merger integration. Thus, Alpha granted the acquired firm, Beta, autonomy and influence in the post-merger organization, allowing for an influx of technology, know-how and processes from the higher status firm, Beta. This sheds further insights into the ‘light-touch’ integration pattern (Liu & Woywode, Citation2013; Lupina-Wegener et al., Citation2020) wherein integration follows a ‘step by step’ or ‘Yībù bù’ strategy which can be seen as embedded in the Chinese proverb ‘the journey of a thousand miles begins with the first step’. Our case shows that while autonomy is granted to a European acquired organization, strategic interdependence only increases gradually; it took Alpha eight years to integrate Beta. This sheds light into identification processes in the ‘reverse takeover’, i.e. those experienced by members from the acquired organization with a perceived inferior status. Our interviewees viewed the acquisition as an opportunity for enhancing their inferior pre-merger identity and thus, they welcomed the changes influenced by the acquired European company. These findings extend existing literature, which shows that if members of an acquired organization perceive their low-status position as legitimate, they are more likely to accept the status asymmetry (Ellemers et al., Citation1993; Hogg & Terry, Citation2000). To our knowledge, we are the first to show that this might also apply to members of an acquiring organization who perceive themselves as having an inferior status, which is common in reverse takeovers; c.f. Lupina-Wegener et al. (Citation2015).

We provide novel insights into literature on M&As and change by introducing the agile organizational identity (AOI) concept, wherein agility is the central, enduring and distinctive characteristic of an organization, i.e. ‘who we are as an organization’. Alpha employees described Alpha as ‘agile and changing’ (central), changing all the time (enduring) and that the agility is what makes their organization distinctive from competitors. The ‘agility’ is one of social categories of the organization or the teams and with which employees can identify. To maintain the agile organizational identity after M&As, employees strive to keep ‘changing’ as ‘change’ is their continuity. The psychological bonds between an employee and the employing organization thus do not become weaker when faced with changes. This sheds additional light into the view of identity as ‘the threads of sameness and continuity that stabilizes the organization in the midst of ongoing change’ (Schultz, Citation2016, p. 101), or as a collective mindset wherein organizational members do not experience social threat despite their low status (Rattan et al., Citation2018).

AOI guides employees’ collective actions towards change and their belief that their organization is able to move swiftly in a changing environment. In the case studied, AOI kept Chinese employees away from the threats and helped them construct PMI despite the frequent changes that took place; identity continuity here is equal to change. Our findings lead to a new way of looking at the relationship between organizational change and identity continuity, and not only in the case of M&As. AOI gives a more nuanced view of the impact of organizational identity on an organization’s ability to change (Price & van Dick, Citation2012).

Despite its importance, agility has received limited attention from social identity scholars. One of the studies addressing agility and looking at identities was conducted by Ragin-Skorecka (Citation2016). Her qualitative investigation reveals that individuals who identify with agility take agile actions and create agile organizations. Organizational agility received attention in various organizational contexts, including in M&As (Brueller et al., Citation2018; Junni et al., Citation2015). The concept of AOI is, however, distinct from organizational agility. The latter is defined as an organization’s ability to continuously adjust and adapt strategic direction in a core business (Holbeche, Citation2015). Organizational members sharing an AOI have agility embedded in their self-concept, they are proud of the agility, and it provides their organization with distinctiveness (‘agility makes us distinctive from competitors’) and continuity (‘without agility we cannot survive’). Organizational agility and AOI are interrelated as the former provides a material reality that facilitates the experience of AOI as shared by members of a group or organization. Organizational agility is evident at Alpha, which prior to the acquisition was a ‘copy-cat’ company. with the data structure shows that dramatic organizational changes in terms of culture, processes, systems, structures implied low observable continuity for the Chinese employees, but still they embraced and appreciated them. It was not the case for the members of the European organization acquired by Alpha, who in contrast experienced ambivalence when faced with a lower degree of change than their Chinese counterparts (Lupina-Wegener et al., Citation2020). Indeed, the subjective experiences reported in the present paper for the Chinese organization are quite different from the ones reported in our previous paper featuring the acquired, European firm, suggesting that organizational agility and AOI are clearly distinct.

In the studied case, the Chairman fostered the agility among Alpha employees. He created the long-term vision based on the agility (c.f. identity entrepreneurship). He also promoted the core interests of Alpha members (c.f. identity advancement) which was the status increase by adopting an ‘Yībù bù’ integration approach. Thus, identity leadership (Steffens et al., Citation2014) plays an important role in building and fostering AOI, and might particularly be relevant in China due to a respect for leaders and strong collectivism (van Dick & Kerschreiter, Citation2016).

Moreover, the AOI concept contributes to the social identity theory by shedding light on underexplored identity construction processes in the context of Chinese organizations. AOI might have a particularly more salient effect on Chinese organizational members’ willingness to change, where an individual’s self-concept is constructed in a strongly collective manner (Lee et al., Citation2015), focused on the benefits for the collective rather than on ‘me issues’ present in Western M&As (Chung et al., Citation2014).

Finally, although the AOI concept was developed in the Chinese context, we believe that AOI can overall help low-status group members effectively cope and thrive with organizational changes in Western contexts as well. Similarly, although we derived the concept from a case study of a low-status organization, AOI might also prove relevant for high-status organizations undergoing transformation or conducting an acquisition such as for example Google, Amazon or Virgin (De Smet et al., Citation2018). Murphy and Dweck (Citation2010) suggest that so called successful organizations with high-performance driven cultures (e.g. Enron; entity theory of intelligence), risk to encourage competition or cheating rather than learning. Instead, they argue that incremental organizations support growth culture and learning goals (e.g. Xerox; incremental theory of intelligence). The concept of the AOI sheds further light into the ‘Organization’s Lay Theory’ with its focus on identity, underpinning organizational culture.

Conclusion

Our findings have implications for leadership and management practice. Acquiring and acquired organizations need to approach the post-merger integration with a growth mindset (Murphy & Dweck, Citation2010), learn from the outgroup members by integrating feedback as legitimate and constructive (Liang et al., Citation2021). The AOI is an important factor to such a constructive ingroup and outgroup collaboration and it helps avoid resistance resulting from pre-merger group membership. Thus, AOI needs to be cultivated by the top management team and spread throughout the organization by identity leaders, as done by the Chairman of Alpha.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our interviewees who gave their time so generously, and whose insights were so valuable to our study. This work was supported by the Swiss National Research Foundation (SNSF) under Grant number 163106.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shuang Liang

Shuang Liang holds a doctorate degree in psychology from Zürich University (2020). Her research interests lie in the field of organizational behaviour and culture, behavioural economics, Social Identity Theory, and agile organizations. She is engaged in cross-cultural behavioural research and Sino-Western collaborations.

Anna Lupina-Wegener

Anna Lupina-Wegener is Professor of Management at the School of Management and Engineering Vaud, HES-SO (University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland). She investigates socio- cultural integration processes in cross- border mergers and acquisitions (M&As), change- and internationalization processes. In cross-cultural settings, she is interested in how managers, engineers and entrepreneurs develop collaborations with multiple stakeholders and how they overcome interpersonal, intergroup or interorganizational conflicts.

Johannes Ullrich

Johannes Ullrich is Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. His research interests are mainly in Social Cognition, Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. He has a PhD in Psychology from Philipps-University, Marburg, Germany. His Venia Legendi was awarded to him in 2009 by Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany, based on his Habilitation on the topic ‘Identification with Organizations’.

Rolf van Dick

Rolf van Dick is Professor of Social Psychology at Goethe University Frankfurt (Germany) and serves as Vice President for International Affairs and Early Career Researchers. Prior to his current position he was Professor at Aston Business School, Birmingham (UK). Rolf van Dick is scientific director of the interdisciplinary Center for Leadership and Behavior in Organizations (CLBO). He has published/edited around 20 books and special issues, and over 250 book chapters and papers in academic journals such as the Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Organizational Behaviour, Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Marketing, Journal of Business Ethics, or the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Rolf was visiting professor in Tuscaloosa (USA), on Rhodes (Greece), in Shanghai and Bejing (China), Rovereto (Italy), in Oslo (Norway), and in Kathmandu (Nepal) and he was editor/associate editor of the British Journal of Management, the European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, the Journal of Personnel Psychology, and The Leadership Quarterly. His research is in the area of social identity processes and he applies social identity theory to topics such as leadership, mergers & acquisitions, health and stress, or diversity. He is a Fellow of the International Association of Applied Psychology.

References

- Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 263–295.

- Amiot, C. E., Terry, D. J., & McKimmie, B. M. (2012). Social identity change during an intergroup merger: The role of status, similarity, and identity threat. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34(5), 443–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.712016

- Ashforth, B., Harrison, S., & Corley, K. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/258189

- Brueller, N. N., Carmeli, A., & Markman, G. D. (2018). Linking merger and acquisition strategies to postmerger integration: A configurational perspective of human resource management. Journal of Management, 44(5), 1793–1818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.56.3.39

- Chung, G. H., Du, J., & Choi, J. N. (2014). How do employees adapt to organizational change driven by cross-border M&As? A case in China. Journal of World Business, 49(1), 78–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.01.001

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Deng, P. (2013). Chinese outward direct investment research: Theoretical integration and recommendations [通过研究中国对外投资发展理论: 现实与建议]. Management and Organization Review, 9(3), 513–539. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/more.12030

- De Smet, A., Lurie, M., & St George, A. (2018). Leading agile transformation: The new capabilities leaders need to build 21st-century organizations. McKinsey, 15. Retrieved 17 June 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/the-five-trademarks-of-agile-organizations

- Ellemers, N., Wilke, H., & Van Knippenberg, A. (1993). Effects of the legitimacy of low group or individual status on individual and collective status-enhancement strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 766–778. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.766

- Gehman, J., Glaser, V. L., Eisenhardt, K. M., Gioia, D., Langley, A., & Corley, K. G. (2018). Finding theory–method fit: A comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27(3), 284–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617706029

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Gleibs, I. H., Mummendey, A., & Noack, P. (2008). Predictors of change in postmerger identification during a merger process: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1095

- Haslam, S. A., Postmes, T., & Ellemers, N. (2003). More than a metaphor: Organizational identity makes organizational life possible. British Journal of Management, 14(4), 357–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2003.00384.x

- Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. J. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/259266

- Holbeche, L. (2015). The Agile Organization: How to build an innovative, sustainable and resilient business. Kogan Page Publishers.

- J.P.Morgan. (2019). Global M&A Outlook: unlocking value in a dynamic market. Retrieved April 12, 2021, from https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/research/2019-ma-global-year-outlook#close

- Junni, P., Sarala, R. M., Tarba, S. Y., & Weber, Y. (2015). The role of strategic agility in acquisitions. British Journal of Management, 26(4), 596–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12115

- Kira, M., Balkin, D. B., & San, E. (2012). Authentic work and organizational change: Longitudinal evidence from a merger. Journal of Change Management, 12(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.652374

- Kumar, N., Stern, L. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1993). Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1633–1651. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/256824

- Lee, E.-S., Park, T.-Y., & Koo, B. (2015). Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 1049–1080. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000012

- Liang, S., Ullrich, J., van Dick, R., & Lupina-Wegener, A. (2021). The intergroup sensitivity effect in mergers and acquisitions: Testing the role of merger motives. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12785

- Lipponen, J., Wisse, B., & Jetten, J. (2017). The different paths to post-merger identification for employees from high and low status pre-merger organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(5), 692–711. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2159

- Liu, Y., & Woywode, M. (2013). Light-touch integration of Chinese cross-border M&A: The influences of culture and absorptive capacity. Thunderbird International Business Review, 55(4), 469–483. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21557

- Luo, Y., & Tung, R. L. (2007). International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 481–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400275

- Lupina-Wegener, A., Drzensky, F., Ullrich, J., & van Dick, R. (2014). Focusing on the bright tomorrow? A longitudinal study of organizational identification and projected continuity in a corporate merger. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(4), 752–772. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12056

- Lupina-Wegener, A., Liang, S., Ullrich, J., & van Dick, R. (2020). Multiple organizational identities and change in ambivalence: The case of a Chinese acquisition in Europe. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 33(7), 1253–1275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-08-2019-0260

- Lupina-Wegener, A., Schneider, S. C., & van Dick, R. (2015). The role of outgroups in constructing a shared identity: A longitudinal study of a subsidiary merger in Mexico. Management International Review, 55(5), 677–705. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-015-0247-6

- Mathews, J. A. (2006). Dragon multinationals: New players in 21st century globalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-6113-0

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Mottola, G. R., Bachman, B. A., Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (1997). How groups merge: The effects of merger integration patterns on anticipated commitment to the merged organization. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(15), 1335–1358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01809.x

- Muralidharan, E., Wei, W., & Liu, X. (2017). Integration by emerging economy multinationals: Perspectives from Chinese mergers and acquisitions. Thunderbird International Business Review, 59(4), 503–518. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21850

- Murphy, M. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2010). A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209347380

- Price, D., & van Dick, R. (2012). Identity and change: Recent developments and future directions. Journal of Change Management, 12(1), 7–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.652372

- Ragin-Skorecka, K. (2016). Agile enterprise: A human factors perspective. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 26(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20610

- Rattan, A., Savani, K., Komarraju, M., Morrison, M. M., Boggs, C., & Ambady, N. (2018). Meta-lay theories of scientific potential drive underrepresented students’ sense of belonging to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000130

- Schultz, M. (2016). Organizational identity change and temporality. In M. Pratt, M. Schultz, B. Ashforth, & D. Ravasi (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational identity (pp. 93–105). Oxford University Press.

- Steffens, N. K., Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., Platow, M. J., Fransen, K., Yang, J., Ryan, M. K., Jetten, J., Peters, K., & Boen, F. (2014). Leadership as social identity management: Introducing the identity leadership inventory (ILI) to assess and validate a four-dimensional model. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(5), 1001–1024. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.05.002

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

- Terry, D. J., & O’Brien, A. T. (2001). Status, legitimacy, and ingroup bias in the context of an organizational merger. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 4(3), 271–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430201004003007

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell.

- Ullrich, J., & van Dick, R. (2007). The group psychology of mergers & acquisitions: Lessons from the social identity approach. In C. L. Cooper, & S. Finkelstein (Eds.), Advances in mergers and acquisitions (Vol. 6, pp. 1–15). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-361X(07)06001-2

- Ullrich, J., Wieseke, J., & Dick, R. V. (2005). Continuity and change in mergers and acquisitions: A social identity case study of a German industrial merger. Journal of Management Studies, 42(8), 1549–1569. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00556.x

- Vaara, E., & Tienari, J. (2011). On the narrative construction of multinational corporations: An antenarrative analysis of legitimation and resistance in a cross-border merger. Organization Science, 22(2), 370–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0593

- van Dick, R., & Kerschreiter, R. (2016). The social identity approach to effective leadership: An overview and some ideas on cross-cultural generalizability. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 10(3), 363–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3868/s070-005-016-0013-3

- van Dick, R., Ullrich, J., & Tissington, P. (2006). Working under a black cloud: How to sustain organizational identification after a merger. British Journal of Management, 17(S1), 69–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00479.x

- van Dijk, R., & van Dick, R. (2009). Navigating organizational change: Change leaders, employee resistance and work-based identities. Journal of Change Management, 9(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010902879087

- van Knippenberg, D., van Knippenberg, B., Monden, L., & de Lima, F. (2002). Organizational identification after a merger: A social identity perspective. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41(2), 233–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/014466602760060228

- Yin, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Zheng, N., Wei, Y., Zhang, Y., & Yang, J. (2016). In search of strategic assets through cross-border merger and acquisitions: Evidence from Chinese multinational enterprises in developed economies. International Business Review, 25(1), 177–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.11.009

- Zou, H., & Ghauri, P. N. (2008). Learning through international acquisitions: The process of knowledge acquisition in China. Management International Review, 48(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-008-0012-1