ABSTRACT

Public sector effectiveness necessitates planned change; however, many initiatives fail. For planned change to be successful, employees’ mental models need to be amended to support new behaviours. One mechanism to achieve this is employee performance conversations, which can elicit behavioural change through introducing new ideas to an individual’s reality. However, many conversations fail to create shared understandings of the need for change. Ford and Ford's [The role of conversations in producing intentional change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 541–570] typology identifies different conversational forms to create the shared understandings required to enact change. This paper reflects on the learnings from a management development intervention based upon Ford and Ford’s typology where managers applied the conversational forms to initiate mental model amendment, thereby enabling planned change. Analysis of qualitative data collected during the intervention suggests that using different types of conversations in a structured manner enabled shared understandings regarding why change was required and what success looked like. Managers recognized that slowing down the conversational process led to more effective mental model amendment, facilitating behavioural change. The paper demonstrates how different conversational forms enable leaders to discuss a planned change from an individual and organizational perspective and elicit mental model amendment to realize change.

MAD statement

This paper explores a new approach to undertaking employee performance management to enable organizational change. The paper applies Ford and Ford’s (Citation1995) conversational typology as a practice model for developing the conversational competencies of managers and leaders. The paper highlights the importance of taking account of employees’ and managers’ different mental models in order to enable planned change. It argues that it is not more conversations that is needed, but instead the capacity to recognize and utilize different conversational forms to realize mental model amendment to elicit behavioural change and thus achieve change. The paper outlines an intervention that applies this new approach to employee performance management training.

Introduction

Public sector organizations are continually changing in response to both external and internal pressures. External pressures include changes of government, shifting policy agendas, governmental austerity measures or politically driven reforms, while internal pressures include the adoption of new practices in order to improve output and outcome effectiveness (Buick et al., Citation2016; Kiefer et al., Citation2014; MacCarthaigh & Roness, Citation2012; Noblet et al., Citation2006; Shannon, Citation2017; Smollan, Citation2015; Wynen et al., Citation2017). However, it is widely known that many organizational changes are unsuccessful, with failure rates as high as 65-70% (Burnes & Jackson, Citation2011; Cândido & Santos, Citation2015; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005; Kunert & von der Weth, Citation2018). Such change failures are often attributed to employee resistance (Coram & Burnes, Citation2001; Ford et al., Citation2008; Piderit, Citation2000) or employee cynicism (Buick et al., Citation2016; Thundiyil et al., Citation2015). Such resistance and cynicism can stem from a lack of communication about the rationale for the change (its legitimization) or its potential benefits, and/or a lack of employee and middle management participation in decision-making (Ford et al., Citation2008; Gill, Citation2002; Shannon, Citation2017; Smollan, Citation2015). As such, some have framed change as essentially a communication challenge, with effective messaging essential for reducing change resistance and enabling employee readiness for change (Karp & Helg, Citation2008; McClellan, Citation2014).

Middle managers can play a key role in overcoming employee resistance or cynicism (Balogun, Citation2003; Currie & Proctor, Citation2005; Huy, Citation2002), consequently playing a pivotal role in change implementation (van der Voet, Citation2016). Predominantly, the literature suggests that middle managers can make a difference through acting as a conduit for change-related communication; for example, undertaking an intermediary role (Balogun, Citation2003; Buick et al., Citation2016) and mediating communication between senior managers and employees (Cao et al., Citation2016). A key mechanism for communicating change-related information can be conversations that focus on improving employee performance and, as a result, the organization as a whole. In this paper, we define employee performance management broadly as any ongoing informal conversations between managers and employees that involve clarifying expectations and the provision of feedback (Blackman et al., Citation2017; O’Donnell, Citation2021), rather than narrowly as formal appraisal or review processes. These conversations enable increased understanding of desired outcomes by discussing change-related information with employees, thus minimizing uncertainty and anxiety through reduction of changed-related stressors (Isett et al., Citation2013; Pick & Teo, Citation2017; Schmidt et al., Citation2017). These new understandings can shift employees’ mental models (Blackman & Henderson, Citation2004; Moon et al., Citation2019) such that they will interpret stimuli in different ways leading to new behaviours that support organizational change (e.g. Buick et al., Citation2016; Liedtka & Rosenblum, Citation1996). Such new stimuli could lead to the development and application of new skills, undertaking new tasks or performing current ones more effectively, or creating motivation to undertake new tasks in the future. We suggest, therefore, that if employee performance conversations are to support organizational change, then they need to shape employees’ mental models (Blackman & Henderson, Citation2004; Moon et al., Citation2019), particularly in a way that supports the planned change. However, we posit that the ability to shape mental models in this way will require managers to recognize and accept the potential impact of their ongoing conversations and to use that knowledge to purposefully plan for, and engage in, different forms of conversation, rather than simply holding more of the same type of conversation (Buckingham & Goddall, Citation2015; Cappeli & Tavis, Citation2016).

In this article, we propose that managing different forms of conversations can help enact successful organizational change through actively shaping the amendment of new mental models. We explore the literature on change management to make the case for why conversations are important for supporting change efforts. We then present Ford and Ford’s (Citation1995) model for conversational change as a framework for holding effective conversations that will support changes in employee performance. We then draw on experiences adopting this model to design and implement an intervention for planned conversations to support change in a policy agency within the Australian Public Service. This paper makes a contribution in two ways: it provides a research-informed practice model linking performance conversations with intentional change, and it offers a new focus on conversational forms as an important, yet under-focused, area of management development.

How Conversations Construct Change

The omnipresence of change and challenges with its implementation, highlight the importance of change management (By, Citation2005), defined by Moran and Brightman (Citation2001) as ‘the process of continually renewing an organization’s direction, structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers’ (p.111). Much research into change management focuses on designing the perfect change implementation template or process (e.g. By, Citation2005; Kotter, Citation1996) or improving the implementation of an extant change process (e.g. Dent & Goldberg, Citation1999; Fernandez & Rainey, Citation2006). Such literature often adopts a linear, structural-functionalist view (Graetz & Smith, Citation2010; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005) where ‘the job of change agents is to align, fit or adapt organizations, through interventions, to an objective reality that exists “out there”’ (Ford, Citation1999, p. 480). The objective is to find a ‘best way’ to manage change that will lead to individuals adopting required behaviours to enact the desired organizational state. However, research suggests that this model of change is limited because ‘it treats change as a single, momentary disturbance that must be stabilized and controlled’ (Graetz & Smith, Citation2010, p. 136) that is, at its core, top-down in nature and about leaders maintaining control (Graetz & Smith, Citation2010). Ultimately, this limited model of change leads to unsuccessful change implementation (Graetz & Smith, Citation2010; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005).

Limited change success rates have triggered proposals for constructed, contingent and emergent approaches to change management, which recognize situational adaptation (Buick et al., Citation2016; Burnes & Jackson, Citation2011; Graetz & Smith, Citation2010; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005; Lawrence, Citation2015). A constructivist approach recognizes that knowledge derives from the interaction between information and the context in which it is presented, particularly with individuals’ pre-existing knowledge (Ortony, Citation1993). Proponents reject the notion of an objective reality (Kenny, Citation1989; Maturana, Citation1988, Citation1999), arguing that observers bring forth their own reality through identifying what they perceive as distinctive and assigning meaning to it (Barrett et al., Citation1995). Thus, individuals’ interpretations of change-related information and how they make sense of it is an important factor in change success. This is particularly the case for middle managers who need to interpret and make sense of the espoused change intent, translating what this means for both themselves and their employees (Balogun, Citation2003; Baraldi et al., Citation2010). This highlights the importance of middle managers’ mental models in two ways. First, is how they perceive change itself which will determine how they approach it. Second, how they interpret the change being undertaken (Santos & Garcia, Citation2006). The combination of these will impact how they perceive and undertake the possibility of shaping employees’ mental models.

Mental models emerge ‘based on a person's knowledge, experience, values, beliefs, and aspirations’ (Moon et al., Citation2019, p. 2). They represent how individuals structure and organize concepts cognitively, providing explanations as to how an individual selectively filters and interprets information, makes sense of this information, makes decisions and, ultimately, behaves. The mental model becomes the frame of reference through which an individual views the world (Barrett et al., Citation1995; Blackman & Henderson, Citation2004; Hemmelgarn, Citation2018; Martignoni et al., Citation2016), providing guidance for action and determining how to react and behave (Easterby-Smith, Citation1980; Moon et al., Citation2019; Retna, Citation2016).

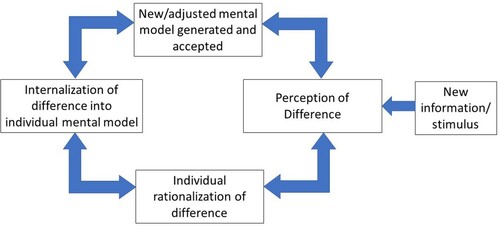

Bounded rationality theory argues that an individual’s ability to act is constrained by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time and resources they have to make a decision (Simon, Citation1991). Thus, it can be argued that mental models become the bounded rationality of an individual shaping how they acquire and process incoming information. Therefore, as indicated in , it becomes apparent that for a person to change their behaviour, their mental model has to be perturbed in a way that offers new possibilities.

Figure 1. Mental model Adjustment (Blackman et al., Citation2013b, n.p).

For any amendment in a mental model there must be some form of new information, or other stimuli (Blackman & Henderson, Citation2004), that leads us to ‘experience uncertainty, discrepancies, or inconsistencies that trigger conscious examination of our implicit beliefs and the mental models we hold’ (Hemmelgarn, Citation2018, p. 102). As seen in , there also needs to be a perception of difference that the individual chooses to at least consider; this is why the issue of how managers provide information and filter the messaging becomes essential. The second part to a potential change is that the individual reflects on the perturbation, actively deliberating on the difference based upon what they already know, creating what Archer (Citation2010, p. 2) describes as an ‘internal conversation’. If an individual makes no connection within their mental model to the new ideas, they are unlikely to be adopted in any form. Assuming that new ideas can be connected to ideas already within the mental model in some way, an internalization of new information will occur, and an adjustment made. This new model becomes the accepted worldview and the frame for all future decisions and behaviours. The question then becomes how can amendments to mental models be triggered; our argument is that planned conversations could provide managers with opportunities to encourage the incorporation of new ideas into an individual’s reality and, therefore, form the basis of future decisions, actions and change.

Conversations take place against a backdrop of previous experiences and knowledge which create the sum of an individual’s bounded reality (Simon, Citation1991). As such, they can help an individual make sense of a proposed change, establish shared understandings of what is required and elicit desired behaviour change (Collm & Schedler, Citation2014; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005). They do this in two possible ways. First, they can provide individuals with new contextual information and learning, which provides the stimulus to open up the potential for the amendment of extant mental models (Ford, Citation2008; Jones et al., Citation2014). Secondly, the conversations can help an individual connect the new information or stimulus with the ideas already within their current mental model, thereby enabling the adjustments needed to make sense of the desired future (Ford et al., Citation2002, Citation2008). Thus, this conceptualization of managing change requires managers to understand the importance of undertaking themed conversations that support the development of new mental models that facilitate the changes in employee behaviours required to deliver desired outcomes.

Dialogue is a reflective conversational mode that is particularly effective for aiding mental model amendment (Jacobs & Heracleous, Citation2005). Dialogue ‘is aimed at the understanding of consciousness per se, as well as exploring the problematic nature of day-to-day relationship and communication’ (Nichols, Citation2003, xi). It can occur within one person (inner dialogue) or between two or more people that involves a ‘stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us’, which may lead to a new understanding (Bohm, Citation2003, p. 6). It does this through enabling individuals to bring forth their current worldviews, discussing and restructuring what they know to construct new meanings and realities (Camargo-Borges & Rasera, Citation2013; Higgs & Rowland, Citation2005; McClellan, Citation2014; Oswick et al., Citation2000). It enables inquiry and critical reflection into one’s deeply held assumptions, thus facilitating the surfacing of mental models (Jacobs & Heracleous, Citation2005; Schein, Citation1993). In doing so, it helps employees make sense of the change (Lawrence, Citation2015) and learn what a change intervention means for them (Endrejat et al., Citation2020). If undertaken effectively and openly, such dialogue involves mutual sense-making and allows conflicts in the meaning-making process to be surfaced (McClellan, Citation2011). This can enable co-creation of change, eliciting a shared understanding of the desired outcomes and behaviours required (Collm & Schedler, Citation2014) and the development of shared mental models (Schein, Citation1993). It can also enable an understanding of the value and salience of the change for them personally (Caldwell, Citation2013), which is particularly important where an effective change requires a common reality, or ‘buy-in’ be established.

If it is accepted that multiple realities can be held by individuals or organizations, and that a series of conversations around themes can create mental model perturbations which can potentially shift such realities (Ford, Citation1999), then the question emerges as to how to use organizational conversations to effect change.

Conversational Types and Forms

There are many types of conversations that take place in organizations, though those between employees and their managers are critical for change success. Such conversations occur continuously and informally, ideally clarifying expectations regarding results (what an employee achieves), as well as desired behaviours (what an employee does) in line with the strategic goals of an organization (Aguinis, Citation2013; Blackman et al., Citation2017). These continuous conversations create the potential for improvement and change, with the communication between managers and employees being critical for change success (Wissema, Citation2000). However, research suggests that these conversations are often poorly undertaken and do not clarify expected behaviours or performance in line with change intent (Buick et al., Citation2016).

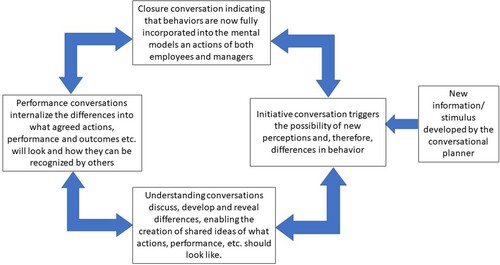

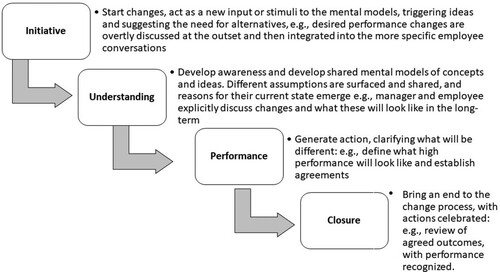

We propose that adopting Ford and Ford’s (Citation1995) conversational typology could be a useful tool for managers to enable change through a series of conversations that provides an opportunity for shared understandings of organizational needs and expectations. Ford and Ford (Citation1995) presented a typology which they argued helped to overcome many of the common reasons why change breaks down, in particular a lack of a shared understanding of both the need for, and the form of, the desired change. Recognizing the different conversational types is important because it acknowledges the role that each might play in enabling employee change readiness (Endrejat et al., Citation2020) and, ultimately, change success. Assuming managed conversations have the capacity to support intentional change, we suggest that adopting this typology as a way to frame performance conversations could provide a way to actively link performance management processes and organizational change (see ).

Figure 2. Different forms of conversations and their role in organizational change during performance management.

In this typology each conversational type plays a pivotal, yet different role in the change process, and change will be dependent upon all the conversational types being used effectively. Although implies a linear sequence, in reality each conversational form may need to be undertaken on multiple occasions to create any shared understanding (see Ford & Ford, Citation1995). This repetition may create a less linear flow, but we do suggest that this overall pattern will need to occur to support intentional change. Because the outcome of any conversation will inevitably shape the context of the next, to be effective each ongoing conversation will need to be planned contingent upon the change in question, the new constructions needing development and the emerging context. When planning conversations for change, a common mistake is to treat all conversations the same, usually moving straight to conversations focused on setting or evaluating goals. Instead, we propose using Ford and Ford’s (Citation1995) typology to design a series of conversations that will act as perturbations to the mental model, thereby eliciting behavioural change. includes examples of different possible conversations for each type.

Table 1. Examples of different forms of manager/employee conversations.

Reconceptualizing conversations undertaken with both managers and employees in this way strengthens the claims by Blackman et al. (Citation2016) that employee performance management could enable change by creating shared purpose, but challenges the ongoing mantra that what is needed is more conversations. Instead, we suggest the need is for different types of conversations that are linked to intentional change. Research undertaken by Blackman et al. (Citation2013a) demonstrated that a lack of clarity and shared understanding of high performance is common, suggesting that conversational breakdowns are occurring (Ford & Ford, Citation1995), and that there is an opportunity for performance management to become an enabler of change. This led to the development of an intervention based upon Ford and Ford’s conversational typology which we now present. We reflect on learnings gained during its implementation to determine the potential application of the conversational typology to support effective intentional change through managed performance conservations.

Methodology

Intervention Development and Design

The objective of this research was to explore the usefulness of an intervention designed to enable intentional change through planned conversations. The intervention was designed over five phases (see ) and was unique in combining Ford and Ford’s (Citation1995) typology with theories of managing expectations and high performance; these interacting concepts provided an alternative strategy to develop managerial competence in planning and undertaking conversations for intentional change.

Table 2. Phases of the intervention development.

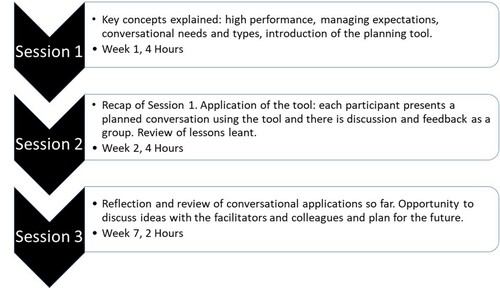

The final intervention incorporated three sessions, run in small interactive groups limited to 12 people with no reporting relationships to each other (see ).

Session 1 was predominantly theoretical, introducing: constructivism as a form of organizational change, the concepts of bounded rationality and mental models, and the conversational types. The conversational tool designed to support preparation using the frameworks was also presented (see ) and participants were asked to identify a situation where there needed to be some form of change in the behaviours of their team. In preparation for Session 2 participants were asked to map possible conversations and, where possible, undertake a trial of the typology in their workplace. Session 2 involved discussing conversations undertaken since Session 1 and then planning further conversations in-depth with the aid of the researchers and participants. The focus of this session was encouraging reflexivity, where managers: (a) became more aware of their assumptions and beliefs regarding how to manage change and influence others (in other words their managerial mental model); (b) started questioning the impact of these assumptions and beliefs, as well as their actions and interactions, on others (see Cunliffe, Citation2016b, Citation2020; Ripamonti et al., Citation2016); and (c) started to realize the agency they had with creating new possibilities (Ripamonti et al., Citation2016). By the end of Session 2, participants had refined their thinking and felt more confident in their ability to use the conversational tool in their workplace to support intentional change.

Table 3. Crafting a conversation planning table.

Session 3 involved participants building on the reflexive deliberations they made since Session 2, reflecting upon their conversational interventions and what they had (or had not) been able to do. Participants who rarely have reflection time in the workplace found this beneficial and it allowed researchers to identify what was working and why. During this session participants were asked what their key learning and/or surprise was and why.

Studying the Intervention

To study the usefulness of the intervention we adopted an action research approach to embed learning processes that could trigger change (Burns, Citation2007; Somekh, Citation1995). Action research starts with a practical problem to be addressed (Reason, Citation2006), and bridges research practice with the dual goals of improving the host organization and generating new knowledge (Burns, Citation2007; Somekh, Citation1995). In this case the host organization’s employee performance management processes had been changed to prioritize conversations (rather than filling out forms) to support change. The new focus had led to a review of the way managers were developed to undertake conversations designed to improve performance, with a realization that the focus was exclusively on having difficult conversations, rather than focusing on how conversations could enable intentional change. This shift in approach required new development opportunities such that managers and employees felt confident holding conversations with the purpose of generating change. In this case researchers reviewed the intervention they designed and delivered, assessing its potential to: achieve changes desired by the host organization; achieve change through conversations more broadly; be integrated into change management theory.

Sample

Recognizing the pivotal role that supervisors and middle managers play in change implementation success (see Bryant & Stensaker, Citation2011; Buick et al., Citation2016; Gibson & Groom, Citation2020; Hope, Citation2010; Teulier & Rouleau, Citation2013; Wissema, Citation2000), the intervention comprised two cohorts: (a) those experienced in managing teams; and (b) those starting or about to start supervising others. The intervention was capped to 16 experienced and 16 novice managers, given its resource intensive nature.

Data Collection and Analysis

Action research encompasses a range of different methodologies and methods (Burns, Citation2007). However, qualitative approaches are typically used to provide detailed understandings of actions taken by recording attitudes, feelings and behaviours (Meyer, Citation2000). Moreover, because they require interactions between the researchers and participants, qualitative techniques can create a greater sense of openness with greater opportunities to surface topics not initially considered and develop more nuanced interpretations (Hart & Bond, Citation1995). This case used three sources of qualitative data: host organization and participant feedback, and researcher reflections.

Host Organization Feedback

After the pilot, organization representatives provided feedback from the pilot participants to the researchers, leading to intervention amendments (see ). Importantly, the intervention was well received with the actual concept and overall content considered valuable and practical, thus remaining unchanged. Participants praised the applied nature of the intervention and commented on its ease of application across a range of conversational needs.

Participant Feedback

Participant feedback was obtained in two ways. First, participants provided qualitative feedback on feedback sheets at the end of the intervention. Participants identified what they had found useful, what needed development and potential uses of the intervention tools, with comments collated and analyzed for common themes. Second, researcher reflections post-intervention captured participants’ key takeaways during the third session.

Researcher Reflections

There were two forms of researcher reflections. First, researchers’ notes and reflections taken during sessions. Second, post each intervention researchers shared their own experiences, observations and learning, and made sense of what had occurred. In each case the research team reflected on participants’ feedback in terms of what mattered and what was different as they planned the conversations; written notes were taken and discussed with all three researchers present.

The research team identified the three recurring themes that were key learnings for participants and led to them being ‘struck’ through having aha! moments (see Cunliffe, Citation2016a). These were: the criticality of creating shared understandings to develop mutuality; the criticality of defining what success looks like; and the importance of slowing down and planning the conversation process. The managers explained how these revelations would guide their approach to future change management as they now recognized the importance of their role in creating the perturbations that could trigger employee mental model amendment.

Findings

Creating Shared Understandings

Participants identified that their key learning from the intervention was the need to plan for and establish shared understandings of what success would look like with their team before planned change was undertaken. Through discussion regarding mental models, participants realized that establishing shared understandings, where the manager and the employee understood each other, and an employee’s mental model could start to shift, was central to enabling intentional change. For all participants this was an important, yet unexpected, element of planned change; they realized that often others did not perceive something in the same way and were not necessarily ready for a conversation. This led to the realization that multiple subjective realities exist (a central part of reflexivity; see Cunliffe, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). For some participants, this was a revelation, as they had assumed others saw things the same way they did. Stepping through the conversational process enabled participants to appreciate and respect differences, which Cunliffe (Citation2016b) argues is a requirement of reflexivity. This led them to questioning their assumptions and actions, and they started seeing the benefits of adopting a more collaborative approach, including the importance of engaging in two-way dialogue and creating space to take on board multiple perspectives (recognizing the uniqueness of others; see Cunliffe, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). This new perspective triggered an appreciation that this was the reason for the initiative and understanding conversation types and why these needed to be successful prior to determining actions to be undertaken. Moreover, participants recognized that seeking change too soon was ineffective and likely to lead to conflict. This became the driver for all examples developed in Session 2.

Several examples focused on establishing a clear purpose for change that mattered for both parties. Other examples included assumptions surfacing during the process that created unexpected barriers such as: incorrectly assuming knowledge about plans; realizing someone had not been listening effectively; and the need for someone to unlearn before they could relearn. Participants also revealed their realization that new knowledge emerged from the conversations and that they could apply the typology to manage up, as well as down. One example was where a participant realized they were covering too many issues in one conversation with their manager to save time and that this led the manager to lose concentration with no resulting change. The participant trialled a new approach prioritizing what they wanted to achieve. They reframed leadership interactions as iterative, not summative, meaning they needed to create space for more, shorter conversations to ensure an ongoing shared understanding. This highlights how participants placed value on the ability to apply the ‘four conversations and … model to many, many conversations … wider than the employee performance (agreement) conversation’ (P6).

Defining Success

Many participants had previously not considered the need to explain and model success to individuals and teams. When using the conversational planning tool and considering the purpose of the conversation, they would usually identify what they wanted to be different in general terms and then concentrate on what they did not want. However, when asked by the researchers to explain what they did want, and how to explain that instead, they realized they were unprepared for that particular conversation. Recognition emerged as to why the same conversation occurred with a direct report on several occasions without change. Examples were given where employees were repeatedly requested to stop doing something, but it was revealed that nothing was done to equip them with the skill or vision to change. Consequently, despite employees’ willingness to change, no alteration of behaviour was forthcoming.

Participants agreed that by developing a clear articulation of the change required, other aspects of the conversational planning were easier to complete. They realized they needed to focus on the desired future state, rather than the current state. Encouraging participants to reframe their focus enabled them to ‘consider how to promote high performance’ (Middle manager, P8) and the action they could take to enable this as part of ongoing change. Participants accepted the need for defining a purpose, which enabled them to succeed, but how to do this was less understood. This became clearer during the pre-planning stage of the conversation when participants placed themselves in the shoes of the other individual. They considered the other party’s expectations and realized how rarely they were ready to discuss the planned change immediately. Moreover, participants realized how rarely they asked the other person for their thoughts on what was needed or granted them time to prepare for meetings about change in a useful way. In one example, a participant started an initiative conversation with her team to establish whether they saw a problem the way she did and, if not, why not; it transpired some did, and some did not. In developing a shared understanding of the different perceptions, the team dynamics, work practices and change readiness developed far faster than they had over many previous interactions.

Slowing Down the Conversation Process

The previous findings indicated a need to slow down and plan conversations. Prior to the intervention, participants tended to go straight to a performance conversation (as defined in the typology). This was culturally encouraged through a focus on time management, getting tasks done and efficiency. In initial discussions regarding the need for different forms of conversations spaced out over time, participants were concerned that this approach would slow down achievement of work and change. However, they admitted to often having to repeat conversations with individual employees, with no emergent change.

The researchers and participants then discussed how behavioural change can be achieved, with the suggestion that change was not occurring because there was no mental model adjustment. Participants found ‘unpicking the ‘why’ for a behavior’ (MM, P11), where the reasons for a change were the focus of the understanding conversations, was valuable for eliciting behavioral change. It was proposed that changing the conversational process would achieve better outcomes, as it enabled an ‘approach to breaking down problems’ (Middle manager, P3) and stepping employees through the process of addressing them. Participants subsequently appreciated value in the approach and realized that what appeared to be slow might enable greater traction and speed. If each conversation is effective, then the next one has a greater chance of leading to change.

In Sessions 2 and 3, after participants attempted to use the conversational forms, it was clear that the process of slowing down, planning different conversational types and often undertaking multiple understanding conversations, enabled behavioural change. Examples were given of how, by using the initiative conversation to convey purpose and enabling readiness to undertake the conversation, the utility and success of the second conversation improved. Participants recognized they typically required multiple understanding conversations before a clear, shared interpretation of the way forward was established. Consequently, participants realized the value of multiple conversations as there had been no real mutuality in previous conversations; while two people were in the room, only one was really ready to talk. One middle manager emphasized the value in adopting an approach ‘focused on building relationships (and consensus) rather than only ‘punishment and reward’’ (P1) as this made real change more likely. Where there appeared to be an ongoing loop in conversations, the structured approach to conversations helped act as a circuit breaker and provided a new way of approaching an issue.

Discussion and Conclusion

Despite the nomenclature of organizational change, most changes emerge through individuals enacting new ways of working. We have presented an intervention designed to increase the efficacy of change through developing managers’ competencies to undertake planned conversations to achieve intentional change. In this paper we demonstrate how working through the different types of conversations supported the establishment of a shared understanding regarding the required change, facilitated the articulation of the desired change and what success looks like, and enabled managers to slow down the conversational process to encourage mental model perturbation, amendment and resultant behavioural change.

Prior to undertaking the intervention, it was apparent that participants had primarily focused on conversations as a means to enact a task or amend behaviour, assuming that the other party would automatically understand their requirements and be able to enact the associated changes. They had not considered that different perceptions existed and that this was the key reason change was not being realized. Participants had not considered the underpinning construct shaping these factors: the existence of different mental models. Undertaking the intervention led to participants’ realization that different mental models do exist, and that through undertaking different types of conversations, they could create perturbations that would influence and/or shape mental models. The novelty participants stressed was the realization that, for there to be change, an individual must acquire and internalize new knowledge and ideas if they are to amend their mental model. Therefore, it became apparent to the researchers that the strength of the programme was that the managers were now aware that they could influence the amendment of mental models and that doing so created new ways of seeing the world.

Different Conversational Forms and Mental Model Amendment

As indicated earlier, a widely recognized barrier to change is where there is a need for mental model adjustment if desired outcomes are to be achieved. How mental models can be actively managed and developed to support desired change is less well documented. shows how the intervention applies the different conversational forms to encourage mental model amendment.

The key is to see conversations as needing to provide a perceived difference. If there is no perception of difference, then there can be no expectation of mental model adjustment. We suggest that when using the conversational tool, managers introduce new information necessary to initiate mental model adjustment. By using this new information to move through the different conversational forms, an understanding is revealed of an individual’s constructed reality and different perceptions. Developing this understanding helps managers understand what is needed to enable change for the individual. Following this, employees and managers can discuss the planned differences in behaviour and create shared ideas of what the desired state looks like, in terms of attitudes, performance and behaviours. We suggest that applying the conversational forms to possible mental model change in this way offers two potential advantages. First, it enables those leading change to discuss the change itself from the perspective of the individual as well as the organization. Second, it helps change leaders consider how they can work with managers undertaking conversations to make sure there is: (1) a perception of difference; (2) a shared understanding of success; (3) ongoing checking mutuality in terms of capacity to be a part of the conversations; and (4) that there is clarity of purpose at all levels. Importantly, the intervention provides a practical model for developing the conversational competencies of managers and leaders. This creates a contribution in two areas. First, it provides a research-informed development process for linking performance conversations with intentional change, supporting earlier work by Blackman et al. (Citation2016). Second, the intervention offers a new focus on communication skills training as an important, yet under-focused, area of management development (Endrejat et al., Citation2020).

We have presented an intervention where change is considered to emerge through the development of new realities and mental models as a function of a web of conversations. We have suggested that different types of conversations can be actively used to influence and manage change through amending mental models. This article makes a qualitative link between employee performance conversations and organizational change which contributes to the literature on change management. However, we report one small action research intervention in a specific context, which is a clear limitation. Consequently, we call for future research to be undertaken into the role of performance conversations as a tool for strategic change, with specific emphasis on how different forms of conversations can be combined to support new mental model development, thereby enabling change success. Any new research would benefit from clearer indicators of mental model changes through the process. This research could include similar qualitative studies in different contexts, as well as quantitative research that tests the relationships we have proposed.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Deborah Ann Blackman

Deborah Blackman is a Professor of Public Sector Management Strategy at the University of New South Wales, Canberra. Her research interests include Public Sector Policy Implementation, Employee Performance Management, Organisational Learning, Organisational Effectiveness and Governance. Current research projects include: understanding the impact of system complexity on effective long-term crisis recovery, mapping wellbeing and mobility systems, and investigating the impact of middle manager capability on the Australian public service.

Professor Blackman has published extensively in a range of international journals, has recently co-edited a book on ‘Handbook on Performance Management in the Public Sector’ (see https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/handbook-on-performance-management-in-the-public-sector-9781789901191.html) and is a member of the Editorial board for Management Learning.

Fiona Buick

Fiona Buick is a Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales, Canberra (Australia). Fiona’s research focus is on the role of organizational culture, strategic human resource management and human resource management in enabling group and organizational effectiveness within the public sector. Previous projects have explored structural change in the Australian Public Sector, middle management capability in the Australian public sector, the role of performance management in enabling high performance in the Australian Public Service (APS), and the role of organizational culture on joined-up working in the APS.

Dr Buick has published in a range of international journals and has recently co-edited a book on ‘Handbook on Performance Management in the Public Sector’ (see https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/handbook-on-performance-management-in-the-public-sector-9781789901191.html).

Michael Edward O’Donnell

Michael O’Donnell is a Professor of Human Resource Management in the School of Business at UNSW Canberra. Michael’s research interests include performance management practices and employment relations in the Australian public sector. Michael has co-authored several monographs including Unions and Globalisation: Governments, Management, and the State at Work (2012) and The Chaebol and Labour in Korea: The Development of Management Strategy in Hyundai (2001). He has published articles in journals that include the Journal of Management Studies, Human Resource Management Journal, Public Administration Review and the Journal of Industrial Relations.

Nabil Ilahee

Nabil Ilahee is an adjunct lecturer at the University of New South Wales, Canberra (Australia). He has several years of experience as a senior manager within IP Australia, the federal agency that administers intellectual property rights and legislation. During this time, Nabil has been involved in Competency Based Training of Patent Examiners from intellectual property offices around the world, in addition to strategic project experience in the areas of organizational culture and frameworks, performance, automation of business processes, quality practices, and leadership capability development.

References

- Aguinis, H. (2013). Performance management (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall/Pearson Education.

- Archer, M. S. (2010). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511618932.

- Balogun, J. (2003). From blaming the middle to harnessing its potential: Creating change intermediaries. British Journal of Management, 14(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00266

- Baraldi, S., Kalyal, H. J., Berntson, E., Näswall, K., & Sverke, M. (2010). The importance of commitment to change in public reform: An example from Pakistan. Journal of Change Management, 10(4), 347–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2010.516482

- Barrett, F. J., Thomas, G. F., & Hocevar, S. P. (1995). The central role of discourse in large-scale change: A social construction perspective. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 31(3), 352–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886395313007

- Blackman, D., Buick, F., & O'Donnell, M. (2017). Why performance management should not be like dieting. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 76(4), 524–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12238

- Blackman, D., Buick, F., O'Donnell, M., O'Flynn, J., & West, D. (2013). Strengthening the performance framework: Towards a high performing Australian Public service. Australian Public Service Commission. https://www.apsc.gov.au/strengthening-performance-framework-towards-high-performance-aps

- Blackman, D., Buick, F., O’Donnell, M., O’Flynn, J., & West, D. (2016). Performance management as a strategic tool for change. In D. Blackman, M. O’Donnell, & S. Teo (Eds.), Human capital Management research: Influencing practice and process (pp. 149–162). Information Age Publishing, Inc.

- Blackman, D.A., Buick, F., O'Flynn, J., O'Donnell, M., & West, D. (2019). Managing expectations to create high performance government. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 39(2), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X17701544

- Blackman, D., Corcoran, A., & Sarre, S. (2013b). Are there really foxes: Where does the doubt emerge? Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 14(1). www.tlainc.com/articl325.htm

- Blackman, D., & Henderson, S. (2004). How foresight creates unforeseen futures: The role of doubting. Futures, 36(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(03)00144-7

- Bohm, D. (2003). On dialogue. Routledge. http://desertcreekhouse.com.au/texts/ondialogue.pdf

- Bryant, M., & Stensaker, I. (2011). The competing roles of middle management: Negotiated order in the context of change. Journal of Change Management, 11(3), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.586951

- Buckingham, M., & Goddall, A. (2015). Reinventing performance management. Harvard Business Review, April, 40–50. https://hbr.org/2015/04/reinventing-performance-management

- Buick, F., Blackman, D., O'Donnell, M., O'Flynn, J., & West, D. (2016). Can enhanced performance management support public sector change? Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-12-2013-0249

- Burnes, B., & Jackson, P. (2011). Success and failure in organizational change: An exploration of the role of values. Journal of Change Management, 11(2), 133–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2010.524655

- Burns, D. (2007). Systemic action research. Policy Press.

- By, R. T. (2005). Organisational change management: A critical review. Journal of Change Management, 5(4), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010500359250

- Caldwell, S. D. (2013). Are change readiness strategies overrated? A commentary on boundary conditions. Journal of Change Management, 13(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.768428

- Camargo-Borges, C., & Rasera, E. F. (2013). Social constructionism in the context of organization development: Dialogue, imagination, and co-creation as resources of change. Sage Open, 3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013487540

- Cao, Y., Bunger, A. C., Hoffman, J., & Robertson, H. A. (2016). Change communication strategies in public child welfare organizations: Engaging the front line. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1093570

- Cappeli, P., & Tavis, A. (2016). The performance management revolution. Harvard Business Review, 94(10), 58–67. https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-performance-management-revolution

- Cândido, C., & Santos, S. (2015). Strategy implementation: What is the failure rate? Journal of Management & Organization, 21(2), 237–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2014.77

- Collm, A., & Schedler, K. (2014). Strategies for introducing organizational innovation to public service organizations. Public Management Review, 16(1), 140–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.822528

- Coram, R., & Burnes, B. (2001). Managing organisational change in the public sector: Lessons from the privatisation of the property service agency. The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 14(2), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550110387381

- Cunliffe, A. L. (2016a). Republication of “on becoming a critically reflexive practitioner”. Journal of Management Education, 40(6), 747–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916674465

- Cunliffe, A. L. (2016b). On becoming a critically reflexive practitioner” redux: What does it mean to be reflexive? Journal of Management Education, 40(6), 740–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916668919

- Cunliffe, A.L. (2020). Reflexivity in teaching and researching organizational studies. Journal of Business Management, 60(1), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020200108

- Currie, G., & Proctor, S. J. (2005). The antecedents of middle managers’ strategic contribution. Journal of Management Studies, 42(7), 1325–1356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00546.x

- Dent, E. B., & Goldberg, S. G. (1999). Challenging resistance to change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 35(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886399351003

- Easterby-Smith, M. (1980). The design, analysis and interpretation of repertory grids. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 13(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7373(80)80032-0

- Endrejat, P. C., Meinecke, A. L., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Get the crowd going: Eliciting and maintaining change readiness through solution-focused communication. Journal of Change Management, 20(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2019.1620826

- Fernandez, S., & Rainey, H. G. (2006). Managing successful organizational change in the public sector. Public Administration Review, 66(2), 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00570.x

- Ford, J. D. (1999). Organizational change as shifting conversations. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(6), 480–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910300855

- Ford, J. D., & Ford, L. W. (1995). The role of conversations in producing intentional change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 541–570. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080330

- Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W., & D’Amelio, A. (2008). Resistance to change: The rest of the story. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159402

- Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W., & McNamara, R. T. (2002). Resistance and the background conversations of change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 15(2), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810210422991

- Ford, R. (2008). Complex adaptive systems and improvisation theory: Toward framing a model to enable continuous change. Journal of Change Management, 8(3-4), 173–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010802567543

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2020). Understanding ‘vulnerability’ and ‘political skill’ in academy middle management during organisational change in professional youth football. Journal of Change Management, https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2020.1819860

- Gill, R. (2002). Change management - or change leadership? Journal of Change Management, 3(4), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/714023845

- Graetz, F., & Smith, A. C. T. (2010). Managing organizational change: A philosophies of change approach. Journal of Change Management, 10(2), 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697011003795602

- Hart, E., & Bond, M. (1995). Action research for health and social care. A guide to practice. Open University Press.

- Hemmelgarn, A. L. (2018). The role of mental models in organizational change. In A. L. Hemmelgarn, & C. Glisson (Eds.), Building cultures and climates for effective Human services: Understanding and improving organizational social contexts with the ARC mode (chapter 8). Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190455286.003.0008

- Higgs, M., & Rowland, D. (2005). All changes great and small: Exploring approaches to change and its leadership. Journal of Change Management, 5(2), 121–151. XXX2

- Hope, O. (2010). The politics of middle management sensemaking and sensegiving. Journal of Change Management, 10(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697011003795669

- Huy, Q. (2002). Emotional balancing of organizational continuity and radical change: The contribution of middle managers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(1), 31–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094890

- Isett, K. R., Glied, S. A. M., Sparer, M. S., & Brown, L. D. (2013). When change becomes transformation. Public Management Review, 15(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.686230

- Jacobs, C. D., & Heracleous, L. T. (2005). Answers for questions to come: Reflective dialogue as an enabler of strategic innovation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 18(4), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810510607047

- Jones, N. A., Ross, H., Lynam, T., Perez, P., & Leitch, A. (2014). Mental models: An interdisciplinary synthesis of theory and methods. Ecology and Society, 16(1), 46. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268859

- Karp, T., & Helg, T. I. T. (2008). From change management to change leadership: Embracing chaotic change in public service organizations. Journal of Change Management, 8(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010801937648

- Kenny, V. (1989). Anticipating autopoiesis: Personal construct psychology and self-organising systems. In A. L. Goudsmit (Ed.), Self-organisation in psychotherapy: Recent research in psychology (pp. 100–133). Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-48704-0_5

- Kiefer, T., Hartley, J., Conway, N., & Briner, R. B. (2014). Feeling the squeeze: Public employees’ experiences of cutback- and innovation-related organizational changes following a national announcement of budget reductions. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(4), 1279–1305. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu042

- Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Harvard Business School Press.

- Kunert, S., & von der Weth, R. (2018). Failure in projects. In S. Kunert (Ed.), Failure management: Scientific insights, case studies and tools (pp. 199–166). Springer International Publishing.

- Lawrence, P. (2015). Leading change – Insights into how leaders actually approach the challenge of complexity. Journal of Change Management, 15(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2015.1021271

- Liedtka, J. M., & Rosenblum, J. W. (1996). Shaping conversations: Making strategy, managing change. California Management Review, 39(1), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165880

- MacCarthaigh, M., & Roness, P. G. (2012). Analyzing longitudinal continuity and change in public sector organizations. International Journal of Public Administration, 35(12), 773–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.715567

- Martignoni, D., Menon, A., & Siggelkow, N. (2016). Consequences of misspecified mental models: Contrasting effects and the role of cognitive fit. Strategic Management Journal, 37(13), 2545–2568. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2479

- Maturana, H. R. (1988). Reality: The search for objectivity or the quest for a compelling argument. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 9(1), 25–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.1988.10557705

- Maturana, H. R. (1999). The organization of the living: A theory of the living organization. International Journal of Human-Computer Systems, 51(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijhc.1974.0304

- McClellan, J. G. (2011). Reconsidering communication and the discursive politics of organizational change. Journal of Change Management, 11(4), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.630508

- McClellan, J. G. (2014). Announcing change: Discourse, uncertainty, and organizational control. Journal of Change Management, 14(2), 192–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.844195

- Meyer, J. (2000). Using qualitative methods in health related action research. British Medical Journal, 320, 178–181. XXX3

- Moon, K., Guerrero, A. M., Adams, V. M., Biggs, D., Blackman, D. A., Craven, L., Dickinson, H., & Ross, H. (2019). Mental models for conservation research and practice. Conservation Letters, 12, 3. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12642

- Moran, J. W., & Brightman, B. K. (2001). Leading organizational change. Career Development International, 6(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430110383438

- Nichols, L. (Ed.). (2003). On dialogue. Routledge. http://desertcreekhouse.com.au/texts/ondialogue.pdf

- Noblet, A., Rodwell, J., & McWilliams, J. (2006). Organizational change in the public sector: Augmenting the demand control model to predict employee outcomes under New Public Management. Work and Stress, 20(4), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370601050648

- O’Donnell, M. (2021). Prospects for continuous performance conversations in the Australian Public service. In D. Blackman (Ed.), Handbook on performance Management in the Public sector (pp. 140–151). Edward Elgar.

- Ortony, A. (1993). Metaphor and thought (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Oswick, C., Anthony, P., Keenoy, T., Mangham, I. L., & Grant, D. (2000). A dialogic analysis of organizational learning. Journal of Management Studies, 37(6), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00209

- Pick, D., & Teo, S. T. T. (2017). Job satisfaction of public sector middle managers in the process of NPM change. Public Management Review, 19(5), 705–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1203012

- Piderit, S. K. (2000). Rethinking resistance and recognizing ambivalence. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 783–794. https://doi.org/10.2307/259206

- Reason, P. (2006). Choice and quality in action research practice. Journal of Management Inquiry, 15(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492606288074

- Retna, K. S. (2016). Consultants and their views on changing the mental models of clients. Journal of Change Management, 16(3), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2015.1121161

- Ripamonti, S., Galuppo, L., Gorli, M., Scaratti, G., & Cunliffe, A. L. (2016). Pushing action research toward reflexive practice. Journal of Management Inquiry, 25(1), 55–68. DOI: 10.1177/1056492615584972

- Santos, M. V., & Garcia, M. T. (2006). Organizational change: The role of managers’ mental models. Journal of Change Management, 6(3), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010600963084

- Schein, E. H. (1993). On dialogue, culture, and organizational learning. Organizational Dynamics, 22(2), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(93)90052-3

- Schmidt, E., Groeneveld, S., & Van de Walle, S. (2017). A change management perspective on public sector cutback management: Towards a framework for analysis. Public Management Review, 19(10), 1538–1555. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1296488

- Shannon, E. A. (2017). Beyond public sector reform – The persistence of change. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 76(4), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12235

- Simon, H. A. (1991). Bounded rationality and organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 125–134. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2634943

- Smollan, R. K. (2015). Causes of stress before, during and after organizational change: A qualitative study. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(2), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-03-2014-0055

- Somekh, B. (1995). The contribution of action research to development in social endeavours: A position paper on action research methodology. British Educational Research Journal, 21(3), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192950210307

- Teulier, R., & Rouleau, L. (2013). Middle managers’ sensemaking and interorganizational change initiation: Translation spaces and editing practices. Journal of Change Management, 13(3), 308–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.822674

- Thundiyil, T. G., Chiaburu, D. S., Oh, I. S., Banks, G. C., & Peng, A. C. (2015). Cynical about change? A preliminary meta-analysis and future research agenda. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 51(4), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886315603122

- van der Voet, J. (2016). Change leadership and public sector organizational change: Examining the interactions of transformational leadership style and red tape. American Review of Public Administration, 46(6), 660–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074015574769

- Wissema, J. (2000). Fear of change? A myth!. Journal of Change Management, 1(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/714042454

- Wynen, J., Verhoest, K., & Kleizen, B. (2017). More reforms, less innovation? The impact of structural reform histories on innovation-oriented cultures in public organizations. Public Management Review, 19(8), 1142–1164. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1266021