ABSTRACT

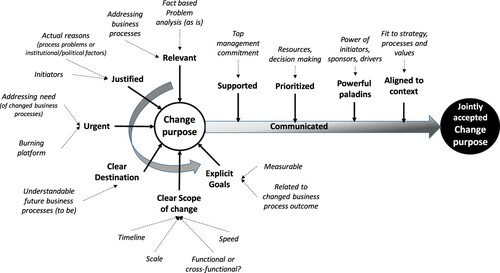

This paper develops a conceptual framework for understanding how organizations create an accepted purpose for organizational change initiatives related to business processes. The framework is based on a longitudinal study related to an Action Research project and the ‘higher level learning’ from using a performance measurement system for change initiatives. Over more than four years, we followed and measured the developments and progress in two separate, major change initiatives related to different business processes in one case organization. The framework has a specific focus on the need for a clear and accepted change purpose. It tries to explicate the nature of change purpose and proposes different interrelated attributes related to the clear content of a change purpose (relevant, justified, urgent, clear destination, clear scope and explicit goals) but also attributes of how the change purpose then should be communicated to be jointly accepted. This operationalization of the nature of change purpose could also inform the current general discussion on purpose related to leadership.

MAD statement

The intention of this article is to Make A Difference (MAD) by addressing problems with change readiness by focusing specifically on change purpose. We explicate the nature of change purpose and operationalize it, proposing a conceptual framework grounded in a longitudinal study of two major change initiatives. The framework could help organizations create an accepted purpose for organizational change initiatives related to business processes. We discuss attributes related to the clear content of a change purpose (relevant, justified, urgent, clear destination, clear scope and explicit goals) and how the change purpose should be communicated to be jointly accepted.

Introduction

The pandemic has inspired several authors to write articles focused on leadership and change (Clegg et al., Citation2021; Crevani et al., Citation2021; Ford et al., Citation2021; Kempster & Jackson, Citation2021; Maak et al., Citation2021; Todnem By, Citation2021). In particular, many articles have emphasized the importance of purpose and the need for more research on purpose. Kempster and Jackson (Citation2021, p. 53) state that ‘ … the premise for the importance of purpose in leadership might be a relatively straightforward proposition, it is an exceptionally complex phenomenon to enact in everyday leadership practice’. Similarly, Clegg et al. (Citation2021, p. 7) find it

… actually quite surprising that the issue of purpose has not received more attention in leadership studies and, after a year such as 2020 in which we have asked repeatedly “what is the purpose of what we are doing?”, or “what should we do, why and for whom?”, it seems even more necessary to explore this concept more deeply.

The aspect of purpose in leadership and management academic research was largely ignored or taken for granted before Kempster et al. (Citation2011). Current research on leadership as purpose (Case, Citation2013; Case et al., Citation2015; Cavazotte et al., Citation2020; Grint et al., Citation2016; Hollensbe et al., Citation2014; Kempster & Jackson, Citation2021; Todnem By, Citation2021) incorporates the purpose or why of leadership to the previous four dimensions person, position, result and process suggested by Grint (Citation2005). Kempster et al. (Citation2011) relate leadership as purpose to societal goals: the pursuit of a ‘greater good’ beyond ‘self’ and beyond ‘the organization’, which separates it from leadership as result normally focused on profit and efficiency. This school of thought is related to redefining organizations as purposeful and defining the scope of business (Hollensbe et al., Citation2014) based on e.g. ethics and sustainability. The focus is on broader corporate purpose and how this can be linked to employees’ personal purpose (van Tuin et al., Citation2020) as part of leadership. Cavazotte et al. (Citation2020) define purpose-oriented leadership as the leader’s ability to articulate higher-level goals that provide employees with a sense of meaning and fulfilment. Beyond the formal wording of a purpose, it should also be actively propagated: a purpose is only strong if employees and other stakeholders believe in it (Bekke, Citation2006).

Still, there is a call for more empirical research to develop our understanding of the nature of purpose, initiated by Kempster et al. (Citation2011) and accentuated by e.g. Stouten et al. (Citation2018), Todnem by (Citation2019, Citation2020), van Tuin et al. (Citation2020) and Kempster and Jackson (Citation2021). This call is further reinforced by the pandemic (by e.g. Clegg et al., Citation2021; Crevani et al., Citation2021; Todnem By, Citation2021) to better understand purpose in general but also challenges faced now and in the future, including purpose related to change management (Lauzier et al., Citation2020; Naslund, Citation2013). Ironically, while change management research has undergone unprecedented growth in the past few decades (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, Citation2015; Barends et al., Citation2014; Lauzier et al., Citation2020; Oreg et al., Citation2013; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018), the success rate for organizational change initiatives is lacklustre at best – also before the pandemic (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, Citation2015; Barends et al., Citation2014; Lauzier et al., Citation2020; Todnem By, Citation2020). Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2018) argue that some reasons for failures can be traced back to different actors’ lack of change readiness, and both Weiner et al. (Citation2008) and Lauzier et al. (Citation2020) highlight the general lack of empirical research regarding change readiness purpose for change efforts.

Relatedly, the pandemic has also highlighted the need for evidence-based leadership for organizational change efforts (Maak et al., Citation2021). Leaders set the tone for change (e.g. knowledge, skills and attitude), and evidence should influence leadership decisions regarding purpose, processes and rewards as well as capacity decisions such as resource allocation (Aarons et al., Citation2014; Maak et al., Citation2021). Ford et al. (Citation2021) discuss how the pandemic highlighted how numerous change effort factors (e.g. type, scale, scope and phase of change as well as potential resistance to change) could contribute to situation variety, which in turn can make the change more complex and complicated to implement. Part of the problem is that issues not known in advance can cause delays or revisions and thus have a negative impact on the change initiative’s implementation pace and progress (Amis et al., Citation2004; Jansen & Hofmann, Citation2011). Thus, situation variety further reinforces the importance of both clear and justified purpose for the change initiative and evidence-based management, which in turn requires a measurement system to manage the change initiative. A measurement system can provide evidence and warning signals (red flags), which give management the opportunity to take corrective actions (Naslund & Norrman, Citation2019).

However, while there are frameworks for organizational change, few longitudinal, empirical research studies exist, which follow a change effort over time while monitoring and measuring change progress. (Barends et al., Citation2014; Buchanan et al., Citation2005; Doyle et al., Citation2000; Stouten et al., Citation2018; Todnem By, Citation2005; van Tuin et al., Citation2020; Weick & Quinn, Citation1999). Most research is survey-based to explain the variance in dependent variables. Although some insights may be gained from such studies (Pearce & Sims, Citation2002), they are insufficient to test the progress of change efforts (Ford et al., Citation2021). Even Holt et al. (Citation2007, p. 253), who developed an initial instrument to ‘evaluate an implemented organizational change’ (based on Armenakis et al., Citation1993 as well as a review of other instruments), emphasize the need to test their instrument in longitudinal studies. Over a decade ago, Holt et al. (Citation2007, p. 233) stated, ‘ … there was a considerable opportunity for improvement because the available instruments lack evidence of validity and reliability’. Thus, the need for longitudinal research is not new, yet as the calls have largely been ignored, evidence-based management is lacking when it comes to change management (Ford et al., Citation2021).

Purpose

The aim of this article is to develop a conceptual framework for understanding the purpose of organizational change initiatives – based on a longitudinal abductive, empirical study over more than four years. This research is the continuation of an Action Research (AR) project to develop a performance measurement system (PMS) for organizational change initiatives. In this article, we present the ‘higher level learning’ from that research project, wherein we have followed and measured the progress of two change initiatives. We check the veracity of criteria for change management success in existing frameworks of change, especially the need for organizations to improve how they work with the change purpose aspects. Change purpose seems, similar to (corporate) purpose related to general leadership (Clegg et al., Citation2021; Kempster et al., Citation2011; Todnem By, Citation2021), to be something often taken-for-granted and implied. In this article, we therefore take a step down from the level of overall leadership of the organization and focus on the management of change initiatives related to business processes. We problematize the notion of ‘purpose’ related to change management (change purpose), which should provide employees with convincing reasons and a sense of meaning for the specific change initiative so that the purpose can be jointly accepted and serve as an engine for change. Thus, we operationalize and develop ‘change purpose’ to be easier to understand and work with change initiatives.

In the next section, we discuss the relevant theory for organizational change efforts related to business processes. After presenting the methodology, we share collected data and abductive reflections before developing our framework. Finally, the paper concludes with contributions and future research suggestions.

Theoretical Framework

Many academic authors have presented change models with slight variation in terms of numbers of steps and specific suggestions (Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Fernandez & Rainey, Citation2006; Kanter et al., Citation1992; Kotter, Citation1995; Luecke, Citation2003; Sabri & Verma, Citation2015). In the original, planned approach, Lewin (Citation1947) divided a change project into three main steps: change readiness (unfreezing the present conditions), implementation (moving to the new condition) and institutionalization (refreezing the new condition). Thus, an organization moves from an ‘as is’ condition (e.g. structures, processes, behaviour and culture) to a ‘to be’ condition in a planned manner (Bamford & Forrester, Citation2003; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). In contrast, the emergent approach assumes that change is less linear, more unpredictable in nature and thus difficult to conduct in a planned manner. Instead, organizations change by continuously aligning and re-aligning to their changing environment (Burnes, Citation2009; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018).

One common characteristic of the change models is the importance of establishing change readiness (Self et al., Citation2007). Change readiness is often divided into two or three aspects related to individual, group and organizational change readiness (Holt & Vardaman, Citation2013; Rafferty et al., Citation2013; Weiner, Citation2009) or environment, structure, and organizational members’ attitudes (Holt et al., Citation2007). A lack of change readiness due to e.g. poor understanding of its impact by change agents, limited focus on employee engagement in the planning and inadequate planning processes, including a lack of appropriate organizational diagnosis, can partially explain some of the failures of change efforts (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). Similarly, Anand and Barsoux (Citation2017) mean that organizations often pursue the wrong changes as the decisions about what to transform tend to be hasty or misguided, resulting in poor performance. To improve change readiness, organizations need to work carefully with the purpose category of a change effort to define the goal of the change effort, identify the reason behind the change, establish the need for change and develop a sense of urgency (Armenakis et al., Citation1993; Kotter, Citation1995; Lauzier et al., Citation2020), sometimes referred to as a burning platform (Anthony, Citation2012).

Reviewing different models for change readiness (Appendix 1), at minimum, the following six steps are recommended. The six steps are all interrelated, and organizations should not work with one step in isolation but rather approach them from a systems perspective:

Establish clear vision and goals for the change effort,

based on a thorough problem analysis,

leading to an accepted need for the change,

including top management commitment and support,

as well as change recipients’ (future users’) support and

for best use of organizational resources.

Establish Clear Vision and Goals for the Change Effort

The importance of scoping the project, to express the difference between the actual state of affairs (as is) and the expected destination (to be) and to set good goals, is emphasized in both the two main approaches to change (Armenakis et al., Citation2009; Byrne, Citation2003; Lauzier et al., Citation2020; McFillen et al., Citation2013). Martin and Mankin (Citation2017) discuss the importance of specific and ‘high’ goals, Neubert and Dyck (Citation2016) mention clear and challenging goals, while Naslund and Norrman (Citation2019) suggest a process-oriented approach with a combination of goals and measures focused on both efficiency (steps of the change process) and effectiveness (outcome of the underlying business process). Various attributes for goals such as SMART also exist (Arumugam et al., Citation2016; Debusk & Debusk, Citation2010).

Goals requiring measuring and Sirkin et al. (Citation2005) mean that frequently reviewed change initiatives are more likely to succeed. Holt et al. (Citation2007, p. 253) stated, ‘Periodic assessment … may provide the necessary information to take whatever actions may be needed to make the change successful’. On the other hand, evidence-based management is lacking when it comes to research, and several authors discuss the need to follow and measure change progress over time (Barends et al., Citation2014; Buchanan et al., Citation2005; Doyle et al., Citation2000; Ford et al., Citation2021; Stouten et al., Citation2018; Todnem By, Citation2005; van Tuin et al., Citation2020; Weick & Quinn, Citation1999).

To state explicit goals for the change (and its purpose) requires a definition of what success looks like (results) and the scope of the project (Grint, Citation2005; Grint et al., Citation2016). Not properly scoping a project (Wasage, Citation2016) or pursuing the wrong change (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017) may increase the risk of wasted resources and not achieving substantial results. Anand and Barsoux (Citation2017, p. 80) write, ‘Before worrying about how to change, executive teams need to figure out what to change’. Scope creep is a common problem as the scope often widens over time, resulting in a diversion of the employees’ attention and loss of focus (Darragh & Campbell, Citation2001). Furthermore, the scope is influenced by aspects such as the scale of change, the silo phenomenon and the speed of the change.

Regarding the scale of change, three main types of change exist: incremental, transitional and transformational/radical (Ackerman, Citation1997; Burnes, Citation2004; Luecke, Citation2003). Incremental change is the most common approach, constituting nearly 95% of organizational changes (Burke, Citation2002). Examples include ‘traditional’ change methods such as Total Quality Management, six sigma and lean (Imai, Citation1997; Shirouzu & Moffett, Citation2004). Transformational change, such as reengineering, is more drastic, radical or revolutionary and can result in an organization that differs significantly in terms of structure, processes, culture and strategy (Kanter et al., Citation1992; Weick & Quinn, Citation1999). As Burns (Citation2003, p. 24) wrote, ‘transformation means basic alterations in entire systems. It does mean alterations so comprehensive and pervasive, and perhaps accelerated, that new cultures and value systems take the places of the old’. Thus, transformational change is often more strategic in nature (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, Citation2015). Transitional change is an in-between version of change.

Another aspect of the scope is whether the change should be functional or cross-functional, process-oriented. Incremental change is often operational and departmental in nature (Burnes, Citation2004; Nadler & Tushman, Citation1989), yet efforts to improve performance do not seem to be successful when they are compartmentalized (Imai, Citation1997; Langstrand & Drotz, Citation2016; Schaubroeck et al., Citation2016). Problems tend to exist between functions in the core cross-functional processes – in the white space (Rummler & Brache, Citation1991) and a functional approach may increase the silo problem as it can lead to sub-optimization, which, in turn, can actually decrease performance for the organization overall (Christopher Citation2000). A functional approach can also lead to fragmentation of projects and too many projects, making prioritization and top management support even more difficult (Spector, Citation2006). The speed and duration of the change will influence the scope and the goals as the longer the duration of the change effort, the more problematic it is for organizations to succeed (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, Citation2015; Chrusciel & Field, Citation2006; Lauzier et al., Citation2020).

Based on a Thorough Problem Analysis

Change initiatives can be started for a variety of reasons as organizations adapt to the demands of both the external and internal environment (Burnes, Citation2004; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). Ideally, a change initiative should be started after a thorough problem analysis and be based on substantial reasons such as experienced problems, a potential opportunity or a genuine desire to improve performance (Wood & Caldas, Citation2001). Providing a substantial reason is an important driver in facilitating change implementation as it justifies the relevance of the change in terms of the organization’s needs, and it can reduce uncertainty among employees (Invernizzi et al., Citation2012; Luo et al., Citation2016), leading to improved change readiness as well as, ideally, increased probability of successful change (Lauzier et al., Citation2020). However, other reasons often exist, such as institutional or political factors or copying the currently popular change method – the fad phenomenon (Miller & Hartwick, Citation2002; Wood & Caldas, Citation2001). In addition, Lauzier et al. (Citation2020) found that less than 30% of published change-related articles provide a reason for the change.

Following a business process perspective, the problem analysis should include problematic processes, problems and root causes. A less than thorough problem analysis can lead to a change initiative started for the wrong reasons, based on assumed causes and assumed solutions or vague goals, which in turn often lead to confusion about the change initiative and unnecessary resource commitments (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017; McFillen et al., Citation2013; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018).

An Accepted Need for Change

The problem analysis sets the tone for the rest of the change, and it will influence several aspects. A change initiative that is not based on a substantial reason, and/or if the perception is that the problem analysis was not conducted properly and not based on appropriate facts, may decrease the potential for change success. Employee resistance is more likely if the employees do not understand the change purpose and believe in the importance of the change initiative (justification) (Armenakis et al., Citation1993; Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Holt et al., Citation2007; Armenakis et al., Citation2009; Invernizzi et al., Citation2012; Holt & Vardaman, Citation2013; Luo et al., Citation2016; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018; Lauzier et al., Citation2020). Weak problem analysis and vaguely defined reasons also make it harder to develop a burning platform to explain and motivate the purpose for change (Anthony, Citation2012). Preparing and getting ready for change thus plays a crucial role in mitigating resistance to change and reducing failure rates.

Top Management Commitment and Support

Top management commitment and support is one of the most important critical success factors for any change effort (Cotte et al., Citation2008; Naslund, Citation2013; Netland, Citation2016; Rafferty et al., Citation2013; Todnem By, Citation2005, Citation2007). Kotter (Citation1995) means that unless 75% of the organizations’ managers buy into the change initiative, it will fail. Reid and Dold (Citation2018, p. 100) write, ‘The engine for change is the leader’ as top managers are the catalyst for transformation, and thus they must focus on leadership capabilities needed to see the change through (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017). Leadership is about delivering on purpose together, and thus, purpose is central to leadership and should be the core of change leadership philosophy (Kempster et al., Citation2011; Todnem By, Citation2019). Both main change models equally emphasize the importance of top management, although they have different approaches for where change is initiated and driven. The planned model is a top-down approach, while the emergent model suggests more of a bottom-up approach (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018; Smith & Graetz, Citation2011). Thus, clarity is lacking regarding how organizations should initiate, structure and drive change (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017). Still, regardless of where and how the initiative was initiated and how it is driven, its success is less likely without strong top management support and commitment.

Change Recipients’ Support

Future users’ (change recipients’) support can be improved by providing solid reasons and a rationale for the change to clarify the discrepancy between the organization’s current situation and the desired outcome and to minimize uncertainty (Holt et al., Citation2007; Invernizzi et al., Citation2012; Lauzier et al., Citation2020; Luo et al., Citation2016) thus building internal support and empower employees for action (Kotter, Citation1995; Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Fernandez & Rainey, Citation2006). In addition, for many change initiatives (e.g. lean projects), both the initiator and the driver of the project are in middle management. While top management approval is needed to start, and top management commitment is needed for success, the project is neither initiated nor driven by top management (Langstrand & Drotz, Citation2016; Naslund, Citation2013). Thus, paladins (champions like initiators, sponsors, drivers, change agents) are important for moving a well-defined and relevant purpose to a jointly accepted purpose in the organization (Drzensky et al., Citation2012; Gondo et al., Citation2013; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018).

Organization and Resources

To improve potential change success and avoid wasting resources, organizations should prioritize and select projects carefully (Arumugam et al., Citation2016; Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017). Selected initiatives should ideally be aligned with the organizational strategy and evaluated according to business benefit, feasibility and organizational impact (Kotnour, Citation2011; Lagrosen et al., Citation2011; Smith, Citation2002). However, inadequate prioritization often causes too many overlapping projects (Pluta & Rudawska, Citation2016). As Johnson (Citation2016, p. 447) writes, ‘Multiple, frequent, excessive, or simultaneous changes are regarded as a major challenge in change management because of their negative impacts on organizational performance’. Too many change initiatives, especially combined with a silo mentality, can lead to project fatigue, a fight for attention, resources and prioritization where the relevant projects may actually suffer while irrelevant ones may benefit as demand exceeds the organizational resources (Cooper et al., Citation2000; Johnson, Citation2016; Pluta & Rudawska, Citation2016; Schaubroeck et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, project prioritization is difficult when the strategic goals are vague and not ranked (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017) or when the project-scoring models do not differentiate well and rate initiatives against absolute criteria rather than against each other (Cooper et al., Citation2000).

Method

This paper is the result of a longitudinal, abductive, empirical case study. We use a mixed-method approach for data collection to explore and better understand the focused phenomena of the purpose of organizational change initiatives in a real-world setting. We justify this approach by our ambition to elaborate theory related to the gap in existing theory on purpose that many authors point out and to more adequately explain this complex phenomenon in depth by providing contextually rich data from multiple sources of evidence. Case studies search for patterns to help understand what is happening and how and why it is done (Naslund, Citation2002; Stuart et al., Citation2002; Yin, Citation2003). In this perspective, the lack of longitudinal studies when it comes to following and measuring change projects makes our study relevant as we base our case study on an underlying AR project to develop a performance measurement system (PMS). The observations from the AR project serve as the foundation for our longitudinal study and analysis.

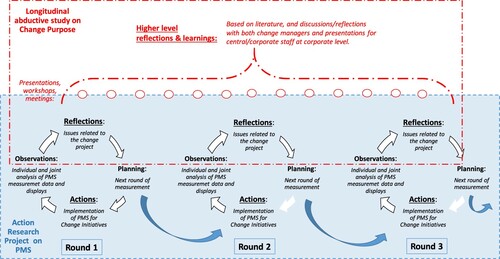

Following the tradition of triangulation as a means of rigour in case studies, we used a variety of data collection methods. First, the PMS was the underlying vehicle for data collection. AR projects are typically focused on change and characterized as cyclical in nature (see ), including cycles of planning, action (implementing), observing (evaluating) and overall analysis and reflection as a basis for new planning and action (Argyris, Citation1993; Coughlan & Coghlan, Citation2002; Naslund, Citation2002; Naslund et al., Citation2010). In our project, each cycle corresponds to a round of measuring the change effort progress. Before each round of measuring, we had planning meetings with the project management teams. After each round of measuring, the data and results from the PMS were used for cycles of analysis and action in collaboration with the case organization. We summarized the survey data into data displays that we sent to the project management teams. We then had meetings with the project teams for analysis (reflections) as a basis for action before the next round of measuring. These meetings had a common semi-structured agenda with discussions and questions (Appendix 2) that normally led to reflective discussions related to current issues. Third, we participated in several workshops, seminars and internal conferences with senior managers from different corporate functions where we discussed how the organization approaches change initiatives (meetings with the change projects, as well as with senior managers from corporate functions at the headquarter, are summarized in Appendix 3). Finally, the researchers also had access to internal data and documents.

Given the longitudinal nature of the study, each cycle of measurement followed by analysis and discussion seemed to indicate a pattern for the problems with the change initiatives and purpose aspects. As researchers, we ‘stepped away’ from the actual research regarding the measurement system for reflection and evaluation if a ‘higher level’ learning exists for the case organization in how they approach and implement change initiatives. As a result of this ‘higher level learning’ analysis, combined with literature reviews as well as feedback from and discussions with the case organization at different organizational levels, our longitudinal, abductive, empirical study allowed us to develop a more nuanced conceptual framework for understanding the purpose of organizational change initiatives. The framework, given its focus on change purpose, can potentially mitigate identified problems as well as help organizations approach change efforts in an improved way. Thus, research was used to inform practice, but practice was also used to inform research (Naslund et al., Citation2010).

The case organization is the Swedish Transport Administration, which is the authority responsible for the overall long-term infrastructure planning of road, rail, sea and air transport. The authority has about 9,000 employees and was established in 2010 by a merger of previous authorities responsible for the different transportation modes. Over more than four years, we followed and actively contributed to the developments in two separate change initiatives in the case organization. The first (α) considers implementation of a new information system to support long-term planning of infrastructure investments, while the second (β) is similar in nature but larger in scale and affects more people. Besides the implementation of a new IT system, β should also change work routines for maintenance – both planning and operations for roads and railways. From a general perspective, these are two common change initiatives: implementation of a cross-functional information system to improve corporate business processes. In our case study, the unit of analysis is the change initiative with a focus on the purpose aspects.

In the next section, we present the longitudinal development of measuring from one change initiative (β), including also ‘higher level learning’ from our cyclical reflections from the case organization, to illustrate the problems of the change initiatives. In appendix 4, we describe details of data collection and the survey instrument related to the developed PMS for change initiatives. In the PMS, we collected data via surveys from respondents who were divided into different stakeholders groups (e.g. top management, project management, different steering groups and future users (change recipients). The questions asked about the respondents’ perceptions whether they agreed on a statement for the status of different aspects. Answers were given on a Likert scale from 1 (No, to a very low degree) to 7 (Yes, to a very high degree). The PMS thus provides a picture of different stakeholder groups’ relative perceptions of the status of the change initiative – the ‘change temperature’.

Change PMS Measurements, Higher Level Reflections and Framework Development

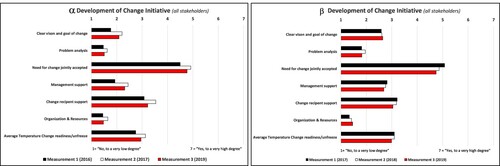

The longitudinal nature of the study allowed us to follow and measure change progress over time. However, for change readiness, the progress was limited, as it had not improved to the expected level after years of work. In fact, it was at an equally low level in all rounds of measuring. shows the overall score for all six steps from all three rounds of measuring for both α and β. As indicates, the overall results were similar for the two change initiatives.

In discussions with both project management teams, we all realized that the measurements indicated several ‘red flags’ for the projects. The severity of the problems and the lack of progress were deeply troubling the project teams. Although we had discussed this issue after all rounds of measuring, and although some actions had been taken, we intensified our reflections on this problem after round three, especially around how well the purpose aspects of the change initiative were established and communicated.

Given the similarity of problems for both the studied change initiatives, these problems may be of general nature for the case organization and could be a result of how the organization approaches change initiatives, especially how they define, communicate and support the purpose of the change initiative. We discussed the results and our reflections with the project management teams and the discussions confirmed our reflections. During seminars and very open discussions, including managers at the headquarter, and during a presentation to the top management group, they all agreed with our analysis. Their organizational approach was lacking when it comes to how they select, prioritize, start and manage change projects. Although we found a positive culture for change, and an agreed need for change, many of the change purpose-related aspects of the initiative did not seem clear or strong in the organization. In the following sections, we first provide a more detailed description of the results for β measurements for each category. We also evaluate and continue to develop our framework (summarized in Appendix 5) based on the analysis of each category, the discussions we had with the case organization (including supporting quotes) and related to existing literature.

Vision, Goals and Scope

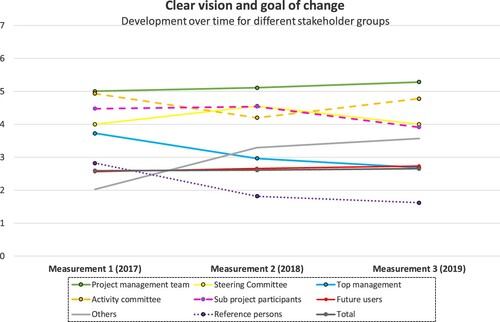

presents the longitudinal development of the average measurement results for the questions related to the ‘Visions and Goals’ category. It shows all eight stakeholder groups defined (by the β team) as well as the total score (combined for all stakeholder groups. The measurements related to the goals of the change initiative were discouraging and the results were frustrating for the project team.

The score for most stakeholder groups was low (below 4) and have for most stakeholders declined over time. Although the project management team has slightly improved, it did not rank the goal category very high in round three (5.29). Top management has declined much and expressed low awareness (2.68) of the projects vision and goal. They provided low scores for all sub-questions, including if a ‘to be’ state was clearly defined (2.36) and communication of goals and changes (2.88). The steering committee versus the activity committee have over time moved in different directions, which the project management team found fit well with how they overtime had prioritized them differently in with whom they communicated and worked intense with.

The project teams realized that they had not worked sufficiently on these issues related to change purpose. Even though goals were expressed, they were somewhat vaguely defined, not business process-oriented and not truly measurable. It was difficult to know what ‘success would look like’ and how to measure improvements. The project managers reflected on these issues in discussions with comments like ‘goals are often fairly vaguely defined on a higher level, not really process oriented’ and ‘we need better goals and we need to communicate these goals to all stakeholders’ and ‘we have to talk more about “improved benefits and value”, we have talked too much about the IT-system’.

Organizations have to define the scope in some combination of aspects related to scale (incremental or transformational, strategic or operational), whether it is functional or cross-functional, process oriented change as well as the speed of change (slow, fast, one time or continuous). It is imperative that organizations give serious thought to the kind, depth and complexity of the necessary changes before implementing them (Dervitsiotis, Citation2003). At the end of the day, the scope of change will influence the nature of the change as well as the goals, which all seems important to understand and establishing a joint change purpose.

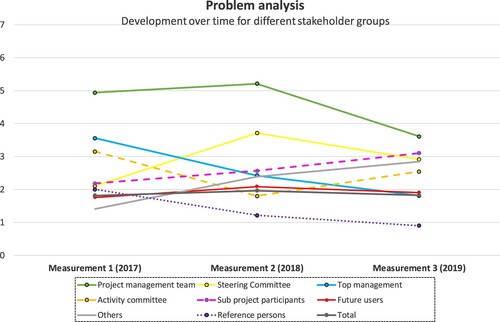

Problem Analysis (and Reasons to Start)

The longitudinal results from the PMS indicate that the problem analysis was insufficient and that it is an ongoing major concern for the respondents (). For some important stakeholder groups (especially project management teams and top management), the situation is getting worse over time. One surprising result is that not even the project team believes in the problem analysis (3.61). Another major concern is top management’s low results on all aspects of problem analysis (below 2 on all questions). Their total score (1.81) was the lowest score among all important stakeholder groups. As the problem analysis should normally come from top management and be understood and communicated by the project management team, the negative trend and these low indicators raised concerns in the case organization. Furthermore, the overall perception among all stakeholder groups (except maybe the project team) is that facts were not used to identify/define the problem.

One explanation for the weak perception of the problem analysis is that even though problems were defined, they were neither properly presented nor communicated. One rationale for this approach was political, as presenting all problems would indicate that some managers ‘looked bad’ and that was not a politically correct action. The project team commented that certain facts could not be used for justification: ‘there were 2 internal reports pointing at the problems, but we could not use the reports in our communication as they were not “politically correct”’. Another project manager expressed the overall frustration as ‘there is an incredible amount of politics involved’. Hence, they found that analysis and actual reasons for change initiatives got overruled by other driving forces. Consequently, the gap between ‘as is’ and ‘to be’ is not properly defined, resulting in an indistinct change purpose.

Another aspect that came up in discussions was the actual reason for starting projects, and where project ideas originate (who initiates a project and why). This aspect is important in order to justify the project (purpose) to future users as well as to top management. However, in the case organization, there is a perception that strong leaders and influential informal leaders can initiate and get projects approved more easily. There is also somewhat of a silo mentality as projects are often initiated within departments (or ‘drain spouts’ as the term is within the organization). Thus, the reason for starting projects is not always based on substantial issues but more based on internal politics. Comments made in discussions reflect this problem: ‘Projects are started for the “wrong reasons” – The most powerful voice will win – they will get the project’ and ‘projects lack connection to strategy, decisions are based more on “the voice of the strong” than a substantial problem analysis’. The perception is also that departmental leaders have their own favourite themes, expressed as follows: ‘They all have their flagships’.

In the case organization, the actual reason for starting change initiative β was hard to identify at first. While there are substantial problems in the organization, these problems were not necessarily observed by top management but rather by operational middle managers. Thus, projects are often initiated by a middle manager and then ‘sold’ to top management for approval via a formal review and approval process. On the other hand, the formal approval process to justify the change initiative is more of a financial process, and thus, the project management groups are still somewhat sceptical if top management has fully ‘bought’ the necessity of the actual operational improvement aspects of the project. As a result, the change initiative was initiated by a middle manager, run by middle managers and, at least to some extent, also owned by the middle managers in the project management group. In reality, top management is not involved in this change initiative. This relates to the discussions on leadership as person and position (Grint, Citation2005).

As the literature highlights, the purpose must be clear and accepted by the organization. In short, one cannot solve a problem one does not understand. Thus, a solid problem analysis would define the current process state (as is) and it would present what the future process state (to be) could be (Appendix 5), which all seems important to understand and establish a joint change purpose. However, as indicated in the case, the actual reason behind the change initiative and its initiator (person and positions) will also influence its development and potential success.

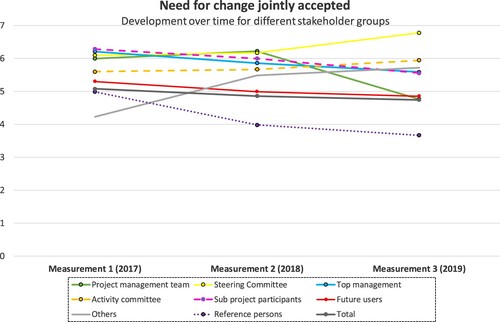

Need for Change – Jointly Accepted and Urgent: Burning Platform

The expressed ‘Need for Change’ is positive () with high scores, over time, for almost all stakeholder groups. The steering committee is especially strong when it comes to expressing a need for change (6.78). In general, is the response to the question whether this particular change is important for the organization (indicating strategic alignment) strong? The negative development of the project management team in the last measurement is worrying and might have influenced the weak conviction that this particular initiative will actually lead to change. Top management ranked this specific question as 4.4 and even the project group seemed sceptical (4.57). Thus, while the overall expressed need for and the importance of change is high, the belief in this particular project is not as high.

Overall the measurements indicate a need to change and a strong willingness to change. One top manager expressed how the organizations had worked with culture to ‘make sure the ceiling is high’ and that ‘all days at work should be good days’. Thus, they want to establish a culture where ‘all issues can be discussed’ and where employees can express concerns and problems. However, the actual willingness to change is questioned. It seems more talk than action as people have bought into the idea that ‘change’ is important on a conceptual level, but actual change is harder to achieve. One could argue that the urgency to change, the ‘burning platform’, is not as significant as the more general acceptance that change is important. Somehow the perception is that although the organization has worked on a culture that officially supports change, the actual change leadership culture is not as strong according to one project leader: ‘the Authority has no change management culture, people in general will not step down and lead. The few doing it became very influential’.

Creating readiness is more than preparing the organization for change by establishing a positive culture (Appendix 5). As seen in the case, other aspects seem important to establish a joint and accepted change purpose. Employees need to understand why the specific change is needed (the purpose), how the business processes will be different and how the change can be achieved. Thus, we argue that a change purpose should be related to a burning platform. The burning platform explains the change purpose by providing the drivers for leaving the current state (as is) and the motivation for a future destination (to be).

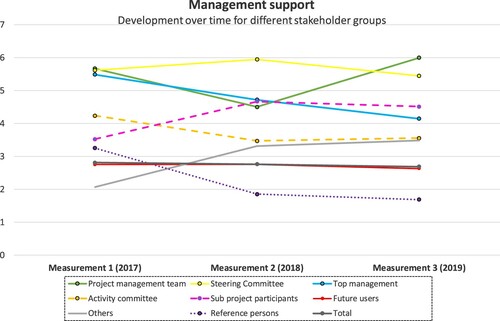

Top Management Commitment and Support

Top management support was perhaps the most troubling issue (). While top managers were somewhat supportive in general questions, their actual support in more specific questions was weaker. Interestingly, while the perception of top management support is relatively high (over or close to 6), and have increased after a dip, among the project management team and the project steering group (where it has been more stable), the support is expressed much lower from the actual top management group itself (total score is 4.15). Furthermore, their scores are especially low related to whether top management (actively) supports project progress (3.2). In addition, other stakeholder groups, such as future users and the activity committee, experienced management support as low and declining.

In addition, top management themselves provides very low scores on different sub-questions in other categories, which indirectly indicates low active top management support. Questions include perception of the project team’s ability to handle problems (2.4 in 2019), a well-communicated change process (2.88), a clear change organization (2.24), resource allocation (1.6) and competing projects (1.84). Given the importance of active top management for project success in theory, this result is a major concern.

In discussions regarding the problem with top management support, the project management group used a phrase that translates into ‘they sit on the bleachers and applaud, but they do not come down to the court to play’. In other words, top management ‘talk the talk’, but they do not ‘walk the walk’. Although they have the position to lead, they are not actually leading (compare Grint, Citation2005). Even though we observed this problem in the first two rounds of measuring, the urgency of this aspect is more concrete after this third round of measuring.

One project manager with experience from other organizations phrased this issue as, ‘you notice a difference compared to other organizations, it is hard to drive and lead projects here’. The project team reflected on the kind of support they get: ‘top management does not understand, they do not have enough knowledge. Thus they have problems being ambassadors although they want to be’. The project team feels that instead of strong management support, ‘the project owns the project’. Another manager expressed it as, ‘you are very solo on the pitch’. However, the project team also found issues in their work to get management better informed: ‘we must communicate more to level-1 managers’.

This is a significant problem as top management commitment and support is one of the most important critical success factors for any change effort (Cotte et al., Citation2008; Naslund, Citation2013; Netland, Citation2016) and it seems similar for getting change purpose jointly accepted. Top management support is also complicated. Aspects such as whether the top manager is initiating, approving and/or driving the change initiative may influence the level of support and commitment for both the change purpose as well as the change itself. The degree of involvement can affect project success and vary from mere lip service to concrete actions with critical decisions at critical times to being the one driving the project. It includes aspects related to allocation/reallocation of resources. At last, top management is responsible for the project outcome, and their level of commitment and support is critical for success.

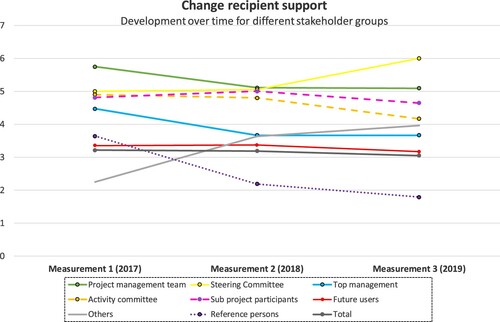

Change Recipients’ (Future Users’) Support

The ‘Change recipients’ support’ (future users) is not strong either, and unfortunately not increasing over time () with the exception of the steering committee (6.00) and the project management team (5.10 but slightly declining). However, engagement and support from these two stakeholder groups is expected. The results in round 3 for the future users are slightly higher compared to other aspects (3.17) but still low on a scale from 1 to 7, especially considering the long-term success of the change initiative. For the sub-question related to ‘I do what I can to make to project progress’, most projects involving stakeholder groups are positive with scores close to or above 6. However, once again, top management is neither engaged nor very convinced, with a score of 2.96 for the question related to the ability of the organization to succeed with the change.

The low support from future users could to some extent be explained by two related facts. First, as the projects are still in the pre-implementation phase, future users are not actually working with the new systems and in the new processes. Second, information about the projects, communication, could have been handled better. Both these aspects are something the project teams are aware of: ‘as any progress have not really been visible, we have kept under the radar with our communication’. The project team also reflects on the need of communicating purpose aspects: ‘the target should have been communicated better – and earlier’ and being more focused: ‘we need to talk more about the “value of the change” – “what’s in it for you”’.

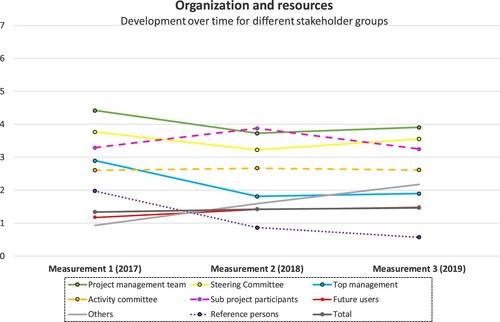

Organization and Resources

In terms of organization and resources, the perception is that the situation is getting worse over time, especially among two key stakeholder groups: the project management group and top managers. The measurements were discouraging, particularly the answers from top management (), where perceptions have declined (below 2) from a low starting point. However, all stakeholders find organization and resources problematic (below 4). The measurement system also highlighted several additional issues. There is a perception that too many projects are started, which also leads to problems with resources, commitment and attention in competing projects. Starting projects, which probably should not have been started, increase the risk of a failed project as projects compete for resources and managerial attention. All stakeholder groups are worried about these competing projects and if there are enough resources for the project with generally low scores for both questions. However, top management is the most concerned stakeholder group. Given that top management are responsible for these two aspects, the results are both confusing and troubling.

These results are very concerning for the project management group. They should be very concerning for top management (and for the entire organization how they conduct change initiatives). One influencing factors seems to be the large number of projects going on in the organization. As previously commented, within the organization, strong leaders know how to ‘work the system’ to get their favourite projects approved: ‘they all have their flagships’.

Given these answers, it is not surprising that more projects are started than finished in the case organization. The case organization also lacks in how they monitor project progress and how they allocate and reallocate resources depending on project progress. We also discussed how a silo mentality in how projects are developed, prioritized and managed added to these problems. For example, as the project leader stated ‘there is limited prioritization of project portfolios’ and thus change initiative β was for a long time hindered by another, similar project (which eventually was cancelled). We also noticed that the project management team is showing signs of ‘project fatigue’. While this problem cannot be entirely blamed on the lack of top management support, the project management team did indicate that it could be one of the reasons. A concrete action is that more resources will be devoted to the initiative β. The project management team is expanded, and this will not only help with change initiative work in general but also help with communication, e.g. of change purpose.

Strategic Alignment

Another change purpose-related aspect that came up in reflections was strategic alignment. Strategic alignment is a frequently mentioned CSF for change in existing literature (Arumugam et al., Citation2016; Cotte et al., Citation2008), and it requires that the change initiative is linked to, fit with, as well as support the organizational strategy. In addition, personal purpose (related to change) should be aligned to the corporate purpose (Kempster et al., Citation2011; van Tuin et al., Citation2020). However, strategic alignment requires that the organizational strategy is defined, which is not always the case (The Economist Intelligence, Citation2013). In addition, implementing a strategy in practice is difficult. According to Mankins and Steele (Citation2005), 66% of corporate strategy is never implemented. If strategic goals are not ranked internally, it also complicates the project prioritization as there are no guidelines for which strategic goal to prioritize. Furthermore, if institutional or political factors are the driving the change effort, the purpose may not be linked to strategy, and thus, the probability of success may diminish (Naslund, Citation2013).

In addition, all change methods are not equally appropriate for all organizations in all industries (Hayes & Wheelwright, Citation1979). Change methods more focused on efficiency (e.g. lean and six sigma) are more appropriate for organizations with high production volumes and a low degree of customization and with low varieties in demand, while for firms at the opposite end of the spectrum, other methods, such as agile, with more focus on effectiveness may be more appropriate (Naslund, Citation2013). Thus, organizations can evaluate alignment in terms of the impact change will have on the cross-functional business process(es). Finally, alignment also means that the values of change method should match the values of the organization (Burnes & Jackson, Citation2011; Detert et al., Citation2000).

In the case organization, the organizational strategy was not exactly clear when the change initiative started. As expressed by one project manager, ‘neither the corporate part of the Authority or the Maintenance division have the overriding target ready’. Obviously, developing and communicating change purpose becomes complicated when it is unclear if a project is aligned with, and support implementation of, the organizational strategy. Furthermore, lack of alignment impacts change progress. Another project manager said, ‘one reason projects are delayed is because they are not really connected to strategy’. These issues are somewhat explained by the fact that the current organization is a merger of two separate organizations with different strategies and cultures.

Since the various alignment aspects will influence the change initiative success, they should be properly evaluated before any change initiative is started. If a change initiative does not align with, fit and support the strategy and/or values of the organization, then it should most probably not be started either. Thus, a proper alignment evaluation may result in fewer projects, which may also increase the probability of success of other projects. In many ways, alignment is thus a key aspect to justify the change purpose.

A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Change Purpose

In our reflective analysis, combining practice and theory, we have seen the importance of having a clear and accepted change purpose (Armenakis et al., Citation1993; Holt & Vardaman, Citation2013; Lauzier et al., Citation2020; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018), and we identified several different attributes related to the change purpose (Appendix 5). In addition, one main point of our framework is that these aspects and attributes related to change cannot be studied in isolation. The aspects are all important by themselves, yet they are also interrelated in a system ().

For example, the literature as well as our study highlights the importance of a purpose that is perceived as relevant. A relevant purpose developed from a fact-based problem analysis (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018), and addressing important business processes (Wood & Caldas, Citation2001), can explain the reasons (Lauzier et al., Citation2020; Luo et al., Citation2016; Miller & Hartwick, Citation2002) behind the change initiative, and who is initiating the change. These aspects may influence if members in the organization find the purpose justified and thus influence the change initiatives outcome (Armenakis et al., Citation2009; Holt & Vardaman, Citation2013). Similarly, while the problem analysis is important in itself, it may not mean much if the urgency for change, the burning platform, does not exist (Anthony, Citation2012), or if it does not address a need for changed business processes (Burnes, Citation2004; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). A clear destination of the change journey (Holt et al., Citation2007; Lauzier et al., Citation2020; Luo et al., Citation2016), the ‘to be’ of future business processes (Byrne, Citation2003; Lauzier et al., Citation2020), is another important aspect when defining the purpose. Finally, explicit goals also mean goals that are both measurable (Arumugam et al., Citation2016; Martin & Mankin, Citation2017) and related to the desired future business processes outcome (Naslund & Norrman, Citation2019). However, if the scope of the change initiative is not clear (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017; Wasage, Citation2016), e.g. its timeline (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, Citation2015; Lauzier et al., Citation2020), scale (Ackerman, Citation1997; Burke, Citation2002), cross-functional ambitions (e.g. Langstrand & Drotz, Citation2016; Rummler & Brache, Citation1991; Schaubroeck et al., Citation2016) or speed (Imai, Citation1997), it will be difficult to define explicit goals. As previously stated, these attributes of the purpose (relevant, justified, urgent, clear destination, clear scope, and explicit goals) are inter-related. While each attribute is important on its own, they also build on or are antecedents to each other. Thus, it is important to understand system interactions between attributes when defining the purpose of the change initiative.

However, even a clear purpose is not enough for organizational change if it is mainly focused on individual change readiness, and thus, organizational change readiness must be given more attention (Weiner et al., Citation2008). To make the change purpose jointly accepted, another aspect of our study, supported in the literature, is the importance of communication of the purpose and why the change initiative is needed. Communication is important not only to make sure the different stakeholders receive and understand the purpose and the need for change but also for them to accept the change project (Kotter, Citation1995). Related to these aspects, we observed many problems in the case organization, resulting in the following suggestions. First and foremost, it is important that the change leaders take communication seriously from the beginning. Second, for acceptance, it is important that the purpose is supported (Netland, Citation2016; Reid & Dold, Citation2018; Spector, Citation2006; Todnem By, Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2019) and prioritized (Anand & Barsoux, Citation2017; Arumugam et al., Citation2016; Johnson, Citation2016; Pluta & Rudawska, Citation2016; Spector, Citation2006) by top management (both in terms of resources and other decisions). The role and reputation of the paladins, in spreading and establishing the purpose, is another important aspect to consider (Drzensky et al., Citation2012; Gondo et al., Citation2013; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). Their role may be even more critical if the support from top management is weak. Finally, our framework highlights the importance of alignment between the change initiative’s purpose and organizational strategy (Kotnour, Citation2011; Lagrosen et al., Citation2011; Smith, Citation2002), which in turn requires that the organizational strategy is clearly formulated and communicated.

Contributions

This study has several contributions. First, the pandemic has reinforced Kempster et al.’s (Citation2011) call for more studies related to purpose aspects – both for organizations in general and when it comes to organizational change (Clegg et al., Citation2021; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018; Stouten et al., Citation2018; Todnem By, Citation2021; van Tuin et al., Citation2020). The pandemic, as well as other global challenges (e.g. climate change), reinforces the need for more research between individual, corporate and a broader societal purpose. This study answers the call for more studies focused on purpose as the developed framework contributes with its specific focus on change readiness and purpose. While there seems to be a consensus among existing change models that the change readiness and purpose aspects are critical for potential success, the results of our research allowed us to develop a nuanced framework on change purpose with detailed attributes in what this work can entail. It contributes theoretically by explicating the nature of change purpose and proposes different interrelated attributes related to the clear content of a change purpose (relevant, justified, urgent, clear destination, clear scope and explicit goals) and also proposes attributes of how the change purpose should be communicated to be jointly accepted. The proposed framework can be used by organizations to improve how they work with the change purpose aspects, potentially mitigate identified problems and, ideally, help organizations approach change efforts in an improved manner.

Second, while the body of research regarding change management is rich, there is also criticism in terms of fragmentation, relevance and rigour (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, Citation2015; Barends et al., Citation2014; Lauzier et al., Citation2020). Surprisingly few longitudinal, empirical research studies exist for change management in general (Buchanan et al., Citation2005; Doyle et al., Citation2000; Ford et al., Citation2021; Rafferty et al., Citation2013; Todnem By, Citation2005; Weick & Quinn, Citation1999) as well as for studies related to organizational change readiness (Weiner et al., Citation2008). Given the predominant focus on surveys to explain the variance in dependent variables (Pearce & Sims, Citation2002), few studies exist to test the progress of change efforts and to evaluate what the actual learning from working on the purpose aspects and measuring change progress could be. Several authors discuss the need for more research when it comes to following and measuring change progress over time (Barends et al., Citation2014; Buchanan et al., Citation2005; Doyle et al., Citation2000; Ford et al., Citation2021; Stouten et al., Citation2018;; Todnem By, Citation2005 van Tuin et al., Citation2020; Weick & Quinn, Citation1999) to test instruments/frameworks over time and to thus increase the validity and reliability. This study empirically contributes by answering that call, providing a longitudinal, abductive, empirical study over more than four years with the original goal to develop a performance measurement system for organizational change. Here, we present its ‘higher level learning’ from periodically testing the veracity of criteria research (i.e. longitudinal measurement against pre-existing criteria) for change management success, especially the need for organizations to improve how they work with the change purpose aspect. Thus, we also empirically also contribute to the call for more empirical studies on organizational change readiness (Weiner et al., Citation2008) as well as evidence-based management (Ford et al., Citation2021; Maak et al., Citation2021).

Third, the operationalization of change purpose could also contribute theoretically to the current general discussion on purpose related to leadership, where one often finds quite vague operationalization and researchers ask for better explanation of the nature of purpose (Kempster et al., Citation2011; Todnem By, Citation2019, p. 2020; van Tuin et al., Citation2020; Clegg et al., Citation2021; Kempster & Jackson, Citation2021; Todnem By, Citation2021). In this literature (compare Kempster et al., Citation2011; Cavazotte et al., Citation2020), the purpose is explained as being a broader corporate meaning (often a greater good linked to higher societal goals) that could be woven into a person’s behaviour as a moral compass, pointing the individual to something meaningful related to both the self and beyond the self. However, how to link the broader corporate compass to the personal one is less discussed, and our framework could contribute with potential parallels to be drawn, in this sense, between the more narrow change purpose and the broader corporate purpose. In our study, we focus on the management of change initiatives related to business processes so that the purpose can be jointly accepted and serve as an engine for change.

Further, we also specify that organizations need to consider alignment and process aspects to justify the purpose. Alignment means that the change project is aligned with and supports the organizational strategy and that the values of the change project are aligned with the organizational values. Working with change purpose aspects include defining the goal of the change effort. As cross-functional processes can serve as a bridge between strategy and operations, the notion of ‘purpose’ related to change management (change purpose) is here concentrated to change of the cross-functional business processes, and thus, goals should be expressed as measurable process goals. As could be seen in the case study, this goal development was lacking and could be one explanation for the lack of progress. Another change purpose aspect includes identifying the reasons (why and by whom) behind the change. The actual reason behind the change initiative is ideally a substantial reason, yet other reasons (institutional, political or copy) could often be the real reason, and it may negatively impact a change initiative’s success. The importance of top management being fully behind supportive of the purpose is further highlighted in our study. Top management support is also important in order to establish the need for change, and to develop a sense of urgency, a burning platform, the organization has to be ready for change. Our study also verifies the significance of relevant, clear and justified goals and that the logic behind the change is communicated to all relevant stakeholders. Finally, the process aspect relates to systems theory/thinking as the purpose aspects are interrelated. By evaluating a change initiative from a systems perspective in terms of the impact it will have on the cross-functional business process(es), organizations can both take a holistic and detailed-oriented approach in evaluating the change initiative. In conclusion, organizations need to justify the purpose for potential success and work on all the purpose aspects – before the change is started. A fourth contribution is thus to the literature about failures and critical success factors of change efforts – from a systems’ perspective (Naslund, Citation2013; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018).

The study contributes practically to the case organization. One practical outcome included is a review of their change initiatives. One specific issue that we observed, implicitly and explicitly discussed, was the problem of getting a jointly accepted change purpose. The study resulted in raising many ‘red flags’ and the impact these identified problems may have on the change initiative (in delays, for example). Several aspects have to be addressed, including goal development, problem analysis, competing projects and resource allocation. Similarly, the issue of a burning platform – or rather the lack of one – was highlighted and the project management group will revisit the problem analysis and goals to develop the burning platform and communicate it better. Another concrete action is that more resources will be devoted to initiative β. The project management team is expanded, and this will not only help with change initiative work in general but also help with communication, e.g. of change purpose. The main issue, however, is the lack of engagement, involvement and support from top management. In discussions with the project management teams, they highlighted that our research has made an impact and that top management is now increasingly aware of the consequences of their lack of involvement and is more willing to be more active in the change projects.

Future Research

Empirically, the framework is based on data from one case organization, and thus, more research is needed in other organizations to further refine and validate the framework. The framework has to be tested more widely to investigate future utility. The explanation of the nature of change purpose might also be transferable to broader corporate purposes, but more research is needed to further explore this potential.

In the case, we also observed an issue with aspects related to who initiates, who drives and who owns change initiatives, relating to leadership as position as well as a person. One of the initiators was a middle manager who navigated the project idea through the internal gateway process for project establishment. However, even with project approval, the middle manager experienced difficulties finding powerful paladins as sponsors and full top management support was lacking, even years into the change initiative. Thus, while the change initiative addresses a need most agree, and the project is approved and running, it is still somewhat unclear who actually owns the project. These challenges may explain the lack of top management to support to help drive the change. Interesting future research can explore the aspects of who is initiating, driving and owning change initiatives and the impact these decisions may have on their outcome. For example, what is the role of middle managers, the role of top management and the relationship between the two? Future research could investigate success factors of large change initiatives that have been initiated and driven by middle management, and it could investigate the role of top management here – what top management support actually means and when/how top managers should act.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dag Naslund

Dag Näslund is the Richard de Raismes Kip Professor of process and operations management at Coggin College of Business, University of North Florida’. He also holds a position at Lund University, Sweden. He received Ph.D. degree in process and supply chain management from Lund University, Sweden. His research interests include organizational change efforts, performance measurements, information sharing and integration in supply chains and research methodology. He has won several prestigious journal and conference awards. He is also active in the business world, leading workshops and presenting at industry seminars/conferences both in the United States and internationally.

Andreas Norrman

Andreas Norrman is a Professor of supply chain structure and organization at Lund University, Sweden. He has worked as a Management Consultant at A.T. Kearney, and he has been an Adjunct or Visiting Professor at universities in Thailand, Belgium and Finland. His research interests include supply chain risk management, omni-channel logistics, supply chain incentive alignment and change management. His work is published in leading SCM journals, and he has received multiple Emerald Highly Commended Awards for his work with IJPDLM, both as an author and a reviewer. He is a Fellow of the Royal Physiographic Society (the Academy for the Natural Sciences, Medicine and Technology) and serves as Senior Editor for Journal of Business Logistics. At Lund University, he has been awarded Excellent Teaching Practice.

References

- Aarons, G., Ehrhart, M., Farahnak, L., & Sklar, M. (2014). The role of leadership in creating a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation and sustainment in systems and organizations. Frontiers in Public Health Services and Systems Research, 3(4), 1–7.

- Ackerman, L. (1997). Development, transition or transformation: The question of change in organisations. In D. Van Eynde, J. Hoy, & D. Van Eynde (Eds.), Organisation development classics. Jossey Bass.

- Al-Haddad, S., & Kotnour, T. (2015). Integrating the organizational change literature: A model for successful change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(2), 234–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2013-0215

- Amis, J., Slack, T., & Hinings, C. (2004). The pace, sequence, and linearity of radical change. Academy of Management Journal, 47(1), 15–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159558

- Anand, N., & Barsoux, J.-L. (2017). What everyone gets wrong about change management. Harvard Business Review, 78–85.

- Anthony, S. D. (2012). How to anticipate a burning platform. Harvard Business Review, 11.

- Argyris, C. (1993). Social theory for action: How individuals and organizations learn to change. Industrial and Labour Relations Review, 46(2), 426–427.

- Armenakis, A. A., & Bedeian, A. G. (1999). Organizational change: A review of theory and research in the 1990s. Journal of Management, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500303

- Armenakis, A. A., Harris, S. G., & Mossholder, K. W. (1993). Creating readiness for organizational change. Human Relations, 46(6), 681–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600601

- Armenakis, A. A., Stanley,, G., & Harris, S. G. (2009). Reflections: Our journey in organizational change research and practice. Journal of Change Management, 9(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010902879079

- Arumugam, V., Antony, J., & Linderman, K. (2016). The influence of challenging goals and structured method on Six Sigma project performance: A mediated moderation analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 254(1), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2016.03.022

- Bamford, D. R., & Forrester, P. L. (2003). Managing planned and emergent change within an operations management environment. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 23(5), 546–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570310471857

- Barends, E., Janssen, B., Ten Have, W., & Ten Have, S. (2014). Effects of change interventions: What kind of evidence do we really have? The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886312473152

- Bekke, D. W. (2006). Joy at work: A revolutionary approach to fun on the job. Pear Press.

- Buchanan, D., Fitzgerald, L., Ketley, D., Gollop, R., Louise Jones, J., Saint Lamont, S., Neath, A., & Whitby, E. (2005). Not going back: A review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x

- Burke, W. W. (2002). Organizational change: Theory and practice. Sage.

- Burnes, B. (2004). Managing change: A strategic approach to organisational dynamics (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Burnes, B. (2009). Reflections: Ethics and organizational change – time for a return to Lewinian values. Journal of Change Management, 9(4), 359–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010903360558

- Burnes, B., & Jackson, P. (2011). Success and failure in organisational change: An exploration of the role of values. Journal of Change Management, 11(2), 133–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2010.524655

- Burns, J. M. (2003). Transforming leadership: A new pursuit of happiness. Grove Press.

- Byrne, G. (2003). Ensuring optimal success with Six Sigma implementations. The TQM Magazine, 9, 183–189.

- Case, P. (2013). Book review: Keith Grint, The Arts of Leadership (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK 2001) 454 pp. and Keith Grint, Leadership: Limits and Possibilities (Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK and New York, NY, USA 2005) 192 pp. Leadership and the Humanities, 1(1), 59–62.

- Case, P., Evans, L. S., Fabinyi, M., Cohen, P. J., Hicks, C. C., Prideaux, M., & Mills, D. J. (2015). Rethinking environmental leadership: The social construction of leaders and leadership in discourses of ecological crisis, development, and conservation. Leadership, 11(4), 396–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715015577887

- Cavazotte, F., Mello, S. F., & Oliveira, L. B. (2020). Expatriate’s engagement and burnout: The role of purpose-oriented leadership and cultural intelligence. Journal of Global Mobility, 9(1), 90–106. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-05-2020-0031

- Christopher, M. (2000). The agile supply chain: Competing in volatile markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(1), 37–44.

- Chrusciel, D., & Field, D. W. (2006). Success factors in dealing with significant change in an organization. Business Process Management Journal, 12(4), 503–516. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637150610678096

- Clegg, S., Crevani, L., Uhl-Bien, M., & Todnem By, R. (2021). Changing leadership in changing times. Journal of Change Management, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1880092

- Cooper, R. G., Edgett, S. J., & Kleinschmidt, E. J. (2000). New problems, new solutions: Making portfolio management more effective. Research-Technology Management, 43(2), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2000.11671338

- Cotte, P., Farber, A., Merchant, A., Paranikas, P., & Sirkin, H. L. (2008). Getting more from lean. BCG Publication.

- Coughlan, P., & Coghlan, D. (2002). Action research for operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(2), 220–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570210417515

- Crevani, L., Uhl-Bien, M., Clegg, S., & Todnem By, R. (2021). Changing leadership in changing times II. Journal of Change Management, 21(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1917489

- Darragh, J., & Campbell, A. (2001). Why corporate initiatives get stuck? Long Range Planning, 34(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(00)00095-9

- Debusk, G. K., & Debusk, C. (2010). Characteristics of successful Lean Six Sigma organizations. Cost Management, 24, 5–10.

- Dervitsiotis, K. (2003). The pursuit of sustainable excellence: Guiding transformation for effective organizational change. Total Quality Management, 14(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478336032000046599

- Detert, J., Schroeder, R., & Mauriel, J. (2000). A framework for linking culture and improvement initiatives in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 850–863. https://doi.org/10.2307/259210

- Doyle, M., Claydon, T., & Buchanon, D. A. (2000). Mixed results, lousy process: Contrasts and contradictions in the management experience of change. British Journal of Management, 11(s1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.11.s1.6

- Drzensky, F., Egold, N., & van Dick, R. (2012). Ready for a change? A longitudinal study of antecedents, consequences and contingencies of readiness for change. Journal of Change Management, 12(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.652377

- Fernandez, R., & Rainey, H. G. (2006). Managing successful organisational change in the public sector: An agenda for research practice. Public Administration Review, March/April, 168–176.

- Ford, J., Ford, L., & Polin, B. (2021). Leadership in the implementation of change: Functions, sources, and requisite variety. Journal of Change Management, 21(1), 87–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1861697

- Gondo, M., Patterson, K. D., & Palacios, S. T. (2013). Mindfulness and the development of a readiness for change. Journal of Change Management, 13(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.768431

- Grint, K. (2005). Leadership: Limits and possibilities. Palgrave Macmillan.