ABSTRACT

This article takes a positive organizational scholarship lens to change management and explores what is the relationship between emotions and communication in managing positive change. Through an abductive study, it suggests a framework of positive post-acquisition change, which centres on interaction in the generation of positive emotions. The framework is built based on a Finnish – German merger completed in late 2013 and substantiated through a German – Finnish acquisition completed in early 2017. Based on the findings, positive emotions can enhance employee identification with the post-acquisition organization as well as increase motivation and engagement in change. Conversely, negative emotions are likely to cause protectionist, change-resistant behaviour. Whereas top-down communication is essential in ensuring day-to-day functions, interaction enables the creation of positive emotions and thereby engages employees in change-congruent behaviour.

MAD statement

Generating positive emotions rather than merely alleviating negative emotions can significantly enhance change outcomes. Practitioners have the ability to encourage the emergence of positive emotions through different communication means. Traditional communication, i.e. ‘information sharing’, ensures day-to-day functionality and can help alleviate worries, but does not engage employees in change. Instead, participation and interaction create a sense of ownership, generating positive emotions and motivating employees to work toward change.

Introduction

Despite decades of research, change management literature to date lacks a detailed understanding of the emergence and influence of emotions (Zietsma et al., Citation2019). In order to explore the link between change management and emotions, this article asks; what is the relationship between emotions and communication in managing positive change. In this article, positiveFootnote1 change is defined as affirmative as opposed to harmful in terms of employee responses and organizational outcomes (Avey et al., Citation2008). With regard to emotions and communication, particular attention is given to the emergence of positive emotions and the communication practices likely to trigger them. This focus is driven by three interrelated shortcomings detected in previous literature.

First, this paper follows Diener et al. (Citation2020) in defining emotions as componential experiences, which consist of a triggering event, cognitive appraisal, action readiness, psychological signals, subjective sensations and behavioural outcomes. Previous research clearly indicates that positive emotions surrounding change are beneficial (e.g. Canning & Found, Citation2015; Dixon et al., Citation2016). Still, particularly the facilitation of positive emotions at work necessitates further research (Allen & McCarthy, Citation2016). This indicates the need to explore how positive emotions emerge at work, particularly during change periods.

Second, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, communication refers to conveying or exchanging information. Previous research reveals that communication enables creating the abovementioned positive climate around change (Ashkanasy & Daus, Citation2002). Yet, the efficiency of communication as a means to overcome potential conflict necessitates further research (Angwin et al., Citation2016; Weber & Drori, Citation2011). Moreover, managerial involvement in the relationship between communication and emotion remains underexplored (Zagelmeyer et al., Citation2016). This highlights the importance of identifying the communication means, which increase positivity and harmony during change periods.

Third, this article adopts the notion that managing positive change occurs through managerial tactics for generating positive subordinate reactions (cf. Ouakouak et al., Citation2020). Yet whereas the benefits of a positive change climate are widely acknowledged, how to manage change in a positive way requires further exploration (Canning & Found, Citation2015; Dixon et al., Citation2016). Despite the knowledge that positive emotions and communication are linked to positive change, managing collective emotions (Huy, Citation2012) continues to puzzle academics and practitioners alike. This advocates exploring active emotion management during organizational change periods (Steigenberger, Citation2015).

To explore this phenomenon in practice, this article examines the post-acquisition change context, i.e. integration. While previous acquisition research most often focuses on negative employee reactions (Graebner et al., Citation2017), empirical evidence proves that change can also trigger positive experiences (e.g. Kusstatscher, Citation2006; Raitis et al., Citation2017). Similarly, previous research confirms communication as a key means for creating positive emotions (e.g. Harikkala-Laihinen et al., Citation2018), yet a gap exists in determining how specific communication practices influence post-acquisition change (Graebner et al., Citation2017). Thus, this context is fitting for the purpose of this article.

This article contributes to three aspects of change management: positive emotion elicitation, communication, and emotion management. The findings reveal that both traditional, top-down communication (i.e. conveying information) and engaging interaction (i.e. exchanging information) are necessary for optimal change results. Traditional communication can alleviate worries, but interaction is the key to positive emotion elicitation. Consequently, these two communication means also function as collective emotion management tools.

The Post-Acquisition Change Context and Key Concepts

Research Context

For approximately three decades now, the mergers and acquisitionsFootnote1, Footnote2 literature has paid increasing attention to the human side of acquisitions (e.g. Sarala et al., Citation2019). This has encouraged researchers and practitioners alike to consider acquisitions as softer, human processes (Cartwright & Cooper, Citation1995). A typology of post-acquisition integration as the combination of task and human aspects (Birkinshaw et al., Citation2000) has become increasingly influential, and acquisition scholars have identified problems in sociocultural integration as a key cause for acquisition failures (e.g. Datta, Citation1991; Marks & Mirvis, Citation2011; Raitis et al., Citation2018). Within this body of literature, acquisition scholars have looked into how emotions play a role, for example, with regard to managers’ emotional reactions, collective emotion regulation, employee behaviour, organizational culture and attitudes toward change (Clarke & Salleh, Citation2011; Durand, Citation2016; Fink & Yolles, Citation2015; Gunkel et al., Citation2015; Reus, Citation2012).

Despite the growing body of literature, acquisition results remain unsatisfactory, indicating the need to understand post-acquisition integration dynamics (e.g. Graebner et al., Citation2017). In particular, the discussion on emotions remains relatively inconsistent and undertheorized (Reus, Citation2012; Zagelmeyer et al., Citation2016). Unfortunately, previous acquisition research largely considers emotions to be problematic, causing poor organizational outcomes. Accordingly, most existing studies focus on negative emotions (Graebner et al., Citation2017). In contrast, a focus on positivity could greatly enrich understanding (Stahl et al., Citation2013), because acquisition-related emotions can also be positive and can have positive outcomes (e.g. Harikkala-Laihinen et al., Citation2018). For example, positivity can help strengthen employee identification with the post-acquisition organization (Raitis et al., Citation2017; Zagelmeyer et al., Citation2016).

The Power of Positivity

To highlight the importance of positive emotions in overcoming potential conflict during post-acquisition integration, this article adopts a positive organizational scholarship (POS) lens, emphasizing positive communication as a driver for organizational success (Cameron, Citation2012). A key concern in POS literature is the generation of positive emotions (Cameron et al., Citation2003), as they can lead to increased thought spectrums, enhanced creativity and improved information-processing ability (Fredrickson, Citation2001; Citation2013). In addition, positivity can ease organizational change by increasing employee engagement (Avey et al., Citation2008) and positive behaviour (Luthans & Youssef, Citation2007).

Change management is often geared towards fighting expected negative reactions, i.e. change resistance (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018; cf. Piderit, Citation2000). Indeed, in order to learn from mistakes, change management literature often examines change failure (Burnes & Jackson, Citation2011; Fuchs & Prouska, Citation2014; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). Thus, POS is a fruitful addition to change management literature, as it enables identifying mechanisms that bring about positive deviance, in order to enhance the quality of organizational life (Roberts, Citation2006). Indeed, POS can be particularly beneficial in committing employees to organizational change (Allen & McCarthy, Citation2016; Caza & Caza, Citation2008). While identifying and dissolving threats to the organization remains at the core of research, a POS lens can push theory and practice beyond neutralizing threats to increased flourishing (Roberts, Citation2006). Moreover, positive change experiences are likely to increase change success (Fuchs & Prouska, Citation2014). Thus, this article adopts a POS lens in highlighting the means for and benefits of positive change management above and beyond the neutralizing stance.

Emotions

Emotions are distinctive affective phenomena, stemming from the higher level concept, affect (Guerrero et al., Citation1996). Core affect refers to a dynamic, continuous, subjective experience of whether we feel pleasure or displeasure on the one hand, and activation or deactivation on the other hand (Russell, Citation2003). Prolonged core affect can turn into moods, which reflect our attitude towards our surroundings. Moods do not have an identifiable root; we can sometimes feel bad or good without knowing exactly why (Guerrero et al., Citation1996). What sets emotions apart is the necessity of an object; emotion is always about something. This is why emotions are also interpretations, making emotions highly personal and subjective: they only arise about topics or situations, which carry some personal value for us (Nussbaum, Citation2004).

Due to their subjective nature, emotions are dynamic experiential processes, where a trigger, response, and representation can be identified (Scherer & Moors, Citation2019). The trigger is often an event or situation in our immediate surroundings, the response refers to our evaluation of the benefit or detriment of that event in terms of our own wellbeing based on our past experience, and the representation reflects a labelled outcome of the evaluation (e.g. Fredrickson, Citation2013; Lazarus, Citation1991). In effect, emotions are most often considered through the category labels, which reflect a set of discrete states (Scherer & Moors, Citation2019). Therefore, in our everyday lives, labels such as love, happiness, sadness or anger refer to emotions.

While much research has been directed at discovering and exploring labelled emotions, studies focusing on the dynamics of emotion elicitation in organizations are scarce (Scherer & Moors, Citation2019). Although previous research highlights the benefit of positivity in terms of driving organizational change (e.g. Canning & Found, Citation2015; Dixon et al., Citation2016), how to encourage the emergence of such positivity at work is yet unclear (Allen & McCarthy, Citation2016). Similarly, while the importance of management actions in creating positivity is acknowledged, just how to manage collective emotions (Huy, Citation2012) in order to create positive change (Canning & Found, Citation2015; Dixon et al., Citation2016) remains unclear. Thus, this paper focuses on how positive emotions emerge and can be managed in organizations during post-acquisition integration.

Communication

Communication is a key means through which organizations can influence employees (Roundy, Citation2010), including their emotions (Harikkala-Laihinen et al., Citation2018). Communication is particularly important during change periods (Barrett, Citation2002), as it can help employees cope with uncertainty, thereby increasing productivity. To this end, communication should be clear, reliable and considerate, and delivered through a variety of channels (Angwin et al., Citation2016; Appelbaum et al., Citation2000). Effective communication is informative, educational and motivating (Barrett, Citation2002), and helps manage employee reactions, guiding perceptions about change towards assurance instead of uncertainty (Lotz & Donald, Citation2006). In contrast, ineffective communication can lead to higher ambiguity and lower commitment (Angwin et al., Citation2016).

While communication is a key tool during integration (Sarala et al., Citation2019), previous acquisition literature tends to focus on the rationality of communication, generally disregarding the emotional element (Zagelmeyer et al., Citation2016). Similarly, when communication-related emotions are considered, the focus tends to be on negative experiences such as uncertainty, anxiety and anger (Graebner et al., Citation2017; Zagelmeyer et al., Citation2016). Despite some recent developments, evidence regarding the relationship between communication and emotion during post-acquisition integration is scarce, and the role of managerial involvement remains underexplored (Zagelmeyer et al., Citation2016). Yet, previous research indicates that communication is essential in creating a positive change climate (Ashkanasy & Daus, Citation2002; Harikkala-Laihinen, Citation2020). Thus, this article explores if and how communication could be a useful tool in managing positive change.

Abductive Research Process

This study follows an abductive, moderate constructionist research process (Järvensivu & Törnroos, Citation2010; cf. Annosi et al., Citation2016; Dubois & Gibbert, Citation2010). Abductive research is particularly suitable for exploring change management, as it enables the examination of interrelatedness between different factors, highlighting theory development rather than generation (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002). Abduction is thus particularly adept when the objective is to explain practical occurrences (Folger & Stein, Citation2017). Moreover, reporting an abductive research process as it unfolds in practice increases the openness and improves the trustworthiness of the study (Schwab & Starbuck, Citation2017).

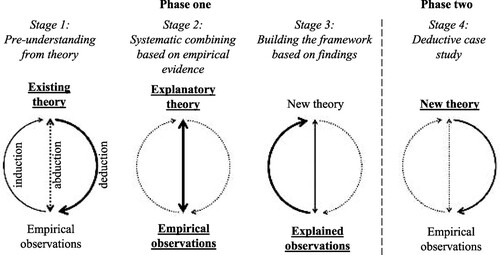

outlines the research process for this study. In phase one, systematic combining is used as a means to move between theory and empirical evidence (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002) in order to find the best possible explanation for surprising findings in the data (Folger & Stein, Citation2017). First, existing literature shaped a pre-understanding reflected in the above sections, which guided data collection. In the second stage, additional literature provided explanatory theory for surprising findings in the data. In stage three, the found literature and explained observations inspired a new framework. The section ‘Study one for phase one’ discusses stages two and three.

Figure 1. Abductive research process. Modified from Järvensivu and Törnroos (Citation2010, p. 103).

In phase two, deduction allows substantiation, acting in the context of justification (Nenonen et al., Citation2017). In abductive research, deduction enables testing emerging ideas (Åsvoll, Citation2014) and determining the explanatory power of an emergent theory (Reichertz, Citation2004). Thus, the fourth stage of the research process confirmed the explanatory power of the new framework. The section ‘Study two for phase two’ discusses stage four.

Both phases primarily follow a qualitative approach, which allows the emergence of interrelated patterns, enabling the formation of suggestive theory (cf. Edmondson & McManus, Citation2007). However, this study utilizes both quantitative and qualitative means of data collection and analysis, yet integrates them in the discussion in order to gain deeper understanding from a limited number of cases (cf. Hurmerinta & Nummela, Citation2011). This mixing of methods brings out the voices of the study subjects more comprehensively (cf. Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011; O’Cathain et al., Citation2007). Recognizing that different sets of data are essential for generating and testing an emerging theory (Hyde, Citation2000), each phase uses a different case, ensuring the richness of description (cf. Dyer & Wilkins, Citation1991) and extensive data collection (cf. Yin, Citation2012), enabling interpretive sensemaking (cf. Welch et al., Citation2011). Each phase of the study discusses case descriptions and detailed information on data collection and analysis separately.

Study One for Phase One

Method

Case Description

The case for phase one explores Finnish Alpha’s acquisition of German Beta, completed in late 2013. Prior to the deal, Alpha was a family-owned, Nordic supplier of technologically advanced user-friendly products, employing approximately 800 workers. Beta, employing 600 workers, was Alpha’s competitor, yet stronger in Central European markets, providing an expansion opportunity for Alpha. Because both companies were similar in size and their product lines were complementary, Alpha chose a best of both worlds approach to integration (cf. Cartwright & Cooper, Citation1993; Haspeslagh & Jemison, Citation1991), resembling a merger of equals. Thus, Alpha Group was born. Although the deal closed already in late 2013, the most intensive integration efforts began in late 2014, coinciding with the research agreement for this study.

The greatest integration effort at Alpha Group centred on creating new organizational values, with specific value workshops to introduce them to all employees in early 2015 overlapping with data collection. All major Alpha Group locations organized the value workshops in-house. Each workshop hosted a maximum of 20 participants with a local facilitator, who guided the participants to reflect on the new Alpha Group values through a series of tasks designed to breathe life into the values. The key purpose of the workshops was to allow employees to share their ideas of how these values could become a part of everyday work at Alpha Group.

The Alpha Group case represents a single, significant case (cf. Patton, Citation2015) that is particularly informative (cf. Fletcher & Plakoyiannaki, Citation2011), making it suitable for abductive research. The merger approach makes this case unique. As such, it is also uniquely suitable for POS, which allows an affirmative bias. Nevertheless, POS does not encourage ignoring negative emotions or challenging contexts, but rather acknowledges that it may be precisely at such times that examples of vitality and organizational flourishing are most vivid (Cameron & Caza, Citation2004). This is also visible in the findings.

Data Collection and Analysis

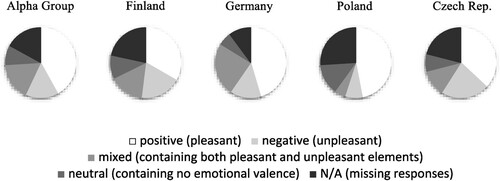

In 2015, Alpha Group employees contemplated what emotions the value workshops, the deal itself, and the subsequent integration evoked in them through an open-ended, qualitative questionnaire. The response rate was approximately 50% (n = 681), with wide participation across Alpha Group’s largest locations in Finland, Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic. In 2016, the employees again reflected on what emotions the deal evoked in them through open-ended, qualitative questions. The response rate was approximately 80% (n = 1,082), again with wide participation across Alpha Group’s largest locations. illustrates the key demographics of the respondents.

Table 1. Respondents.

For both qualitative surveys, the responses were first coded quantitatively into neutral (0 – no emotional valence or arousal), negative (1 – displeasing valence or arousal), mixed (2 – both pleasing and displeasing elements), and positive (3 – pleasing valence or arousal) emotional content. The numeric data offered a quick overview of the aggregate contents, mainly in the form of percentages.

QSR NVivo 11 software aided further analysis of the data containing emotional information (i.e. coded 1, 2, or 3), focusing on specific emotions and their triggers. Lazarus’s (Citation1993) categorization of emotions, which divides emotions into four positive (happiness, pride, relief, love), nine negative (anger, anxiety, fright, guilt, shame, sadness, envy, jealousy, disgust) and two mixed states (hope, compassion) guided categorization. For example, the employee response ‘The takeover made it possible to combine our strengths, which strengthens the company for the future’ reflected happiness, as it portrays ‘Making reasonable progress toward the realization of a goal’ (Lazarus, Citation1993, p. 13). In turn, the response ‘Management must live up to these values as an example, otherwise they are senseless’ portrayed anger, as it entails ‘A demeaning offense against me and mine’ (Lazarus, Citation1993, p. 13) in that the employees were asked to behave in one way, whereas management was not seen to follow the same rules.

In addition to the surveys, semi-structured interviews with Alpha Group management (11) and employee representatives (2) between late 2015 and mid-2016, six in Finland in Finnish, and seven in Germany in English, provided more personal, in-depth data regarding the context and emotional experiences. The interviews were audio-recorded (altogether approximately 830 min) and transcribed to ease analysis. Organizing the data in QSR NVivo 11 software reflected both theoretical and inductive themes. The analysis focused on detailing the emotion elicitation process during post-acquisition change. During the analysis process, it became clear that the emergent emotions were not merely those of anxiety and stress expected in previous acquisition literature (e.g. Graebner et al., Citation2017). Moreover, the stance towards change was not resistant, as predicted in much of the change management literature (e.g. Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). Instead, two questions, which existing literature could not explain, arose: Why are they so happy? And What is special about interaction? These questions form the key point of problematization in this article (Alvesson & Sandberg, Citation2011). Thus, pertaining to the abductive paradigm, the findings from study one are explored through answering these surprising empirical questions (cf. Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002; Folger & Stein, Citation2017).

Why Are They So Happy?

Although previous acquisition literature expects the employees to be miserable, at Alpha Group positive emotions were clearly dominant at the time of integration as revealed by the 2015 employee satisfaction survey ().

This raised the question, why are they so happy? Exploring this question through systematic combining, two key concepts seemed to offer the best explanatory power: cognitive appraisal theory and affective events theory.

Cognitive Appraisal Theory

In human evolution, emotions were fundamental for survival by prompting humans to seek nurturance and avoid harm (Izard, Citation1984). However, research settings often operationalize emotions as componential experiences, which include a combination of appraisal, action readiness, physiological responses, behavioural outcomes, and subjective feelings (Scherer & Moors, Citation2019). This is a cognitive approach to emotion. Cognitive appraisal theory stems from the work of Magda Arnold (Cornelius, Citation2006), who claimed that emotion requires perception and appraisal (Arnold, Citation1960). Here, appraisal refers to a degree of personal relevance and is an evaluation of the importance of a certain situation or event to the wellbeing of the self (Lazarus, Citation1991). Thus, emotions are judgments (Solomon, Citation2003) and include a trigger, an evaluation, and a reaction (Fredrickson, Citation2001).

The emotion labels that arise from the cognitive process are varied, and because emotions are essentially subjective experiences, categorizing them is difficult (Mandler, Citation1999). Despite the difficulties, categorizations build on the hedonic quality of the emotion, meaning whether it feels good or bad (Gordon, Citation1987). In addition to being positive (pleasing, good, or goal-congruent) and negative (displeasing, bad, or goal-incongruent), different emotions have different appraisal patterns, distinguishing them from other emotional states. Lazarus (Citation1991; Citation1993) has suggested that what separates the emotions from each other are the specific relationships they describe between the experiencing individual and the surrounding context. For example, happiness refers to making reasonable progress toward an objective, whereas anger reflects a demeaning offense against oneself or a group with which one identifies.

Affective Events Theory

Affective events theory suggests that work-related events can act as triggers for emotions. It counterbalances traditional judgment-based theories of work-related behaviour, drawing a line between the work context itself and events in the environment that can cause emotional reactions. It proposes that work-related emotions have a direct link to behaviours and attitudes (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996). Here, the term event refers to a discrete episode at work (Morgeson et al., Citation2015) that provokes an appraisal (Basch & Fisher, Citation1998) related to one’s job tasks or relationships at work (Casper et al., Citation2019).

Change, such as post-acquisition integration, is a common emotion trigger at work (e.g. Dhingra & Punia, Citation2016; Kiefer, Citation2002). When considering change acceptance, it is noteworthy that, apart from valence, emotions can have activating power. For example, the two negative emotions of anger and fear have rather opposite activation patterns. Whereas anger can aggravate and increase impulsiveness, fear often leads to withdrawal (Ashkanasy & Dorris, Citation2017). To generate proactive attitudes towards change, activating positive states such as excitement seem most beneficial. Change acceptance signifies positive states without activation, such as calmness. Conversely, disengagement from change efforts occurs when emotional experiences are negative and deactivating, such as with helplessness or sadness. In turn, active negative emotions such as anger create change resistance (Oreg et al., Citation2018).

Revisiting the Emotions at Alpha Group

At Alpha Group, employees expressed myriad emotions identifiable in the categorization outlined by Lazarus (Citation1993) ().

Table 2. Emotions at Alpha Group (see also Harikkala-Lahinen, Citation2019, pp. 228–232).

On the positive side, happiness emerged through the belief in continuity triggered by the extensive change efforts, most notably the value workshops. Similarly, relief signalled an increased sense of security. The employees felt pride in the ability to carry out the acquisition and in working for a company that had expressed values to guide everyday work. On the negative side, anxiety arose from the uncertainties of integration and the perceived lack of progress, whereas anger emerged when employees saw actions as unjust. A sense of loss created sadness, and jealousy emerged from difficulties in understanding the new decision-making structures. Nevertheless, hope arose from employees’ seeing the synergy potential of uniting the two companies.

Notably, employees gave a wide range of labels to these experiences. Happiness, for example, is synonymous with joy, enthusiasm, or optimism (cf. Laros & Steenkamp, Citation2005), whereas anxiety matches nervousness (cf. Watson & Clark, Citation1999). In addition, employees experienced several emotions simultaneously, including contradictory emotions, signalling that the emotions are not mutually exclusive (cf. Carrera & Oceja, Citation2009; Watson & Clark, Citation1999). Furthermore, emotions are dynamic, as they are bound in time and space (cf. Lazarus, Citation1991; Scherer, Citation2009). Regardless, events at work undoubtedly triggered emotions (cf. Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996). Most positive were the employee emotions regarding the interactive and engaging value workshops. This highlights an interesting point. Whereas communication appeared lacking, the value workshops – arguably a communication effort – clearly triggered mainly positive emotions. This led to the question, what is special about interaction.

What Is Special About Interaction?

A key positivity trigger at Alpha Group were the designated value workshops where every employee was able to make sense of the new company values.

The observation that we all, sometimes even unwittingly, have similar principles and values, was very constructive. In such a community, it is easier to head in one direction – toward our common goal. (Survey respondent)

These workshops were a massive communication effort on the part of Alpha Group. In addition, the values were a recurring topic in the in-house employee magazine, where they appeared in short comic strips showing how the values translated to everyday work. The values also appeared in all company meetings and presentations, and even became a part of the recruitment. Yet overall, employees continued to experience communication as somewhat sub-optimal, claiming that cooperation between units was lacking. This encouraged looking deeper into the concepts of communication and interaction.

Communication and Interaction

Organizational communication is a means for employees to interpret work-related events, which in turn enables organizations to use communication in order to influence employee perceptions (Roundy, Citation2010). However, following acquisitions, the increased stress of the change period can make communication more difficult (Lotz & Donald, Citation2006). Nevertheless, open (Angwin et al., Citation2016) and frequent (Weber et al., Citation2011) communication is vital during integration (Schweiger & Denisi, Citation1991). Clear, consistent, considered information from several interconnected channels helps employees handle uncertainty and thus increases productivity following acquisitions (Appelbaum et al., Citation2000). In fact, effective communication is essential for any type of organizational change. Communication is effective if it is simultaneously informative, educational, and motivational (Barrett, Citation2002).

Following an acquisition, most successful communication efforts form a dynamic, ongoing process. A stream of well-planned, coherent messages facilitate employee commitment to the acquisition and help avoid information shortage or overload (Angwin et al., Citation2016). However, interaction – the ability to participate – seems most effective in terms of achieving social cohesion (Cooper-Thomas & Anderson, Citation2006; Morrison, Citation2002). Involvement can greatly increase employee willingness to commit to acquisition-related changes (Appelbaum et al., Citation2007). To achieve the benefit, employees must have the ability to get directly involved in the change effort (Simonsen Abildgaard et al., Citation2020). Participation allows employees to form an understanding of the reasoning behind changes and creates a sense of ownership and control, motivating employees to work toward the change. Participation also increases awareness of the positive aspects of change, thus generating more positive emotions (Rafferty & Jimmieson, Citation2018). A key means of building unity through interactive communication is dialogue.

Dialogue

Dialogue means ‘a sustained collective inquiry into the processes, assumptions, and certainties that compose everyday experience’ (Isaacs, Citation1993, p. 25). In essence, it signals a flow of meaning (Bohm, Citation2003; Senge, Citation1990) that embraces different viewpoints (Oliver & Jacobs, Citation2007). The goal of dialogue is to achieve understanding rather than agreement (Isaacs, Citation1999), enabling group members to move toward converging beliefs and values (Oliver & Jacobs, Citation2007), ultimately building a joint culture (Bohm, Citation2003; Schein, Citation1993).

In dialogue, each participant has the chance to voice thoughts and emotions. At the same time, each participant must actively listen and empathize with each speaker, respecting everyone’s entitlement to their own position and suspending all judgment (Isaacs, Citation1999). Authentic dialogue occurs when three different information-processing motivations converge (Choi, Citation2014). Epistemic information processing refers to the desire to make an effort towards achieving understanding (De Dreu et al., Citation2008). This is the sphere where group-based decision-making is rational (Choi, Citation2014). Social information processing motivation centres on the contents of information (Steinel et al., Citation2010), determining which group outcomes are most desirable (Choi, Citation2014). Pro-self motivation seeks to increase individual benefits, whereas pro-social motivation encourages the pursuit of group goals (Steinel et al., Citation2010). Compassionate information processing motivation depicts empathic responses (Choi, Citation2014) that reflect compassion – being moved by perceived suffering (Lazarus, Citation1993).

Revisiting Communication at Alpha Group

The most important thing is to understand the people and speak with them, and to be open. It is communication – I cannot think of anything that would be more important. (Integration manager)

Moreover, Alpha Group employees did respond particularly well to participative communication in the form of interaction (cf. Clayton, Citation2010; Cooper-Thomas & Anderson, Citation2006; Morrison, Citation2002). The value workshops gave employees the chance to explore each other’s viewpoints and come to a joint understanding – i.e. it gave them the chance to engage in dialogue (Isaacs, Citation1999; cf. Oliver & Jacobs, Citation2007).

People appreciate that they are now much more involved than before. (Vice president, sales)

During the value workshops, employees were invited to breathe life into the new organizational values. They had the chance to look for ways to use the values in everyday work throughout the company, reflecting an epistemic motivation (cf. De Dreu et al., Citation2008). They also had the chance to link the values in action to pro-social group goals, reflecting social information processing (cf. Steinel et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, the employees were encouraged to consider their colleagues, suppliers, and customers, reflecting a compassionate motivation (cf. Choi, Citation2014). Thus, interaction – for example, dialogue – seems to be beneficial in positive post-acquisition change.

A Framework for Positive Post-Acquisition Change

Positive organizational change refers to affirmative rather than harmful change experiences (Avey et al., Citation2008). A key way to encourage positive change is by offering employees positive emotion triggers (Cameron, Citation2008), which increase positive emotional experiences and lead to positive, change-congruent behaviour (Fredrickson, Citation2013). Positive triggers can include managers’ positive emotion displays (Newcombe & Ashkanasy, Citation2002) or engaging, interactive change initiatives (Cameron & Green, Citation2012). Here, the emphasis is on the interconnections between communication – particularly interaction – and emotions.

Based on the Alpha Group case, emotions following acquisitions occur on many organizational levels (cf. Ashkanasy, Citation2003), are dynamic during the integration process, and cause behavioural outcomes. Positive change does not mean the exclusion and ignorance of negative emotions, but an emphasis on overcoming challenges (cf. Avey et al., Citation2008; Bar-tal et al., Citation2007). Thus, also negative emotions need space at all levels to maintain the positive balance of the changing environment. At the same time, it is important to stay on top of possible negative emotions in order to discourage their spread.

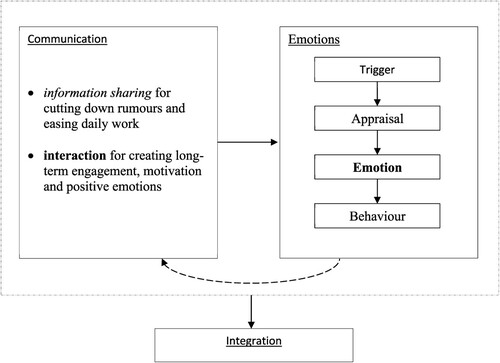

To increase overall positivity, interactive communication that enables the generation of positive emotions seems to be a key concern. Nevertheless, traditional top-down communication, i.e. information sharing, is important for creating a level playing field where interaction can occur (). Company presentations, bulletin boards, email newsletters etc. have a critical role in keeping employees informed. This information can decrease rumouring and ensure employees can carry on their daily work during hectic change periods. Absorbing such information requires limited individual involvement from employees, even though employees may find the messages unpleasant at times.

Table 3. Information sharing and interaction.

Conversely, interaction allows employees to take a more active role and become engaged in the process. Interaction can occur in team meetings, social gatherings, or specifically designed workshops. It is often initiated top-down, but to become truly interactive, openness and participation are crucial. The purpose of such interaction is to engage employees, create a sense of ownership of the change process, and thus motivate them to carry out the change. As these communication means are very different, they also triggered different emotions at Alpha Group. Whereas information sharing was often connected to negative emotions (i.e. uncertainty and anxiety due to perceived lack of information) or to neutralizing negative emotions (i.e. overcoming information shortages), interaction was able to create positive emotions and employee engagement. Thus, both seem equally necessary, but have different roles during post-acquisition integration.

Based on Alpha Group, positive post-acquisition integration necessitates an understanding of communication practices as well as employee emotions (). The framework, based on existing literature (e.g. Angwin et al., Citation2016; Balle, Citation2008; Roundy, Citation2010) as well as the Alpha Group case, suggests reliable, repeated, rich communication is necessary for successful integration, evidenced in triggering positive emotions. The framework emphasizes the benefits of interaction in increasing employee engagement and motivation, thus encouraging positive emotions and behaviour (cf. Appelbaum et al., Citation2007; Clayton, Citation2010; Cornett-DeVito & Friedman, Citation1995).

Following an acquisition, positive organizational change requires positivity towards the post-acquisition organization. If employees’ positive emotions reflect the pre-acquisition organization, they are likely to cause protectionist behaviours, as any change poses a threat to the social group (cf. Menges & Kilduff, Citation2015). This is often problematic, as acquisitions tend to bring forth employees’ old, pre-acquisitions identification. Thus, a sense of continuity is essential in redirecting identification towards the new, post-acquisition organization (Van Vuuren et al., Citation2010). For example, positive attitudes toward the new values encouraged employees to change their behaviour. Conversely, negative emotions related to the values, such as seeing someone violate them, caused employees to disregard them. Thus, positive emotions, which reflect the change process or goals, are likely to boost change efforts, whereas negative emotions regarding the change or positive emotions regarding the pre-change organization can hinder them. To explore the explanatory power of the suggested framework in a different context, study two focuses on a more traditional acquisition setting.

Study Two for Phase Two

Method

Case Description

German Gamma bought Finnish Delta in January 2017. Prior to the deal, Delta was a small manufacturing company employing 77 workers, and had struggled with profitability for years. However, Delta’s product range was competitive and of high quality, making it an interesting target for Gamma, a large group in the same business area that had formerly been a customer of Delta. Whereas Delta had sales across Europe, the Middle East, and India, Gamma’s brand was global. Thus, the deal offered Gamma a wider product range and Delta broader networks and longevity. Gamma chose a rather slow and detached integration approach (cf. Cartwright & Cooper, Citation1993; Haspeslagh & Jemison, Citation1991), deciding to maintain the separate company and brand names. Nevertheless, unification occurred in, for example, company structures and reporting processes.

Data Collection and Analysis

Phase two takes the acquired company’s point of view. This reflects the majority of acquisition literature, which assumes emotions – particularly negative emotions – occur mostly in the acquired organization (cf. Graebner et al., Citation2017). Thus, a slightly different setting, where negative emotions may be expected, best challenges the emerging framework.

At Delta, data collection began with 17 semi-structured interviews with representatives of all organizational levels and functions in the spring and summer of 2017, with nine separate follow-up interviews in the spring of 2018. The interview questions reflected the key themes found in phase one: (1) background of the deal, (2) completion of the acquisition, (3) emotions and the working atmosphere, and (4) communication. Under these main sections, the focus was on how the informants experienced integration. Most interviews took place face-to-face in the Finnish language, but due to overseas locations, two were conducted via Skype, and due to differences in mother tongues, two were conducted in English. The interviews were audio-recorded (altogether approximately 1,360 min) and transcribed for analysis, which occurred through themed categorization in QSR NVivo 11 software.

In 2017, the interviewees were encouraged to write a memo-like diary detailing their everyday experiences regarding the integration. Ten respondents made 44 entries. In 2018, the diary was open for all employees, and 6 respondents made 21 entries. The diary frame consisted of one A4 sheet asking the employees to (1) rate their day on a scale from 1 to 10, (2) share any emotions they felt or detected, and (3) consider how the emotional climate at work could be improved. The main body of the diary was open-ended, engaging the informants in producing qualitative, textual data, whereas question one produced quantitative data. All diaries were written in Finnish, and the analysis occurred through categorization based on issues that employees experienced as creating positivity or negativity within Delta, giving more heft to the interview findings through illustrative quotes. As the diarists were too few to represent the entire organization, quantitative analysis on the daily ratings was not feasible. Instead, the ratings informed the analysis of the qualitative sections. Diarists that rated their days consistently low experienced mainly negative emotions, whereas diarists whose daily ratings varied also reported varied experiences.

All Delta employees had the chance to contemplate their opinions about the deal, communication during the deal, the working atmosphere, and management during the acquisition through four open-ended, qualitative questions in an employee satisfaction survey in the fall of 2018. These topics reflect the key issues from phase one and from the interviews conducted at Delta. The response rate was approximately 59% (n = 56). Most responses were in Finnish, with some written in English. The survey data categorization used the themes of the questions as well as the themes from the interviews to inform the emerging findings. In effect, the survey data illustrated and strengthened the points already identified as significant in the interviews. Finally, all of the data collected from Delta informed the illustrative quotes representing the experienced emotions, as categorized by Lazarus (Citation1993).

Employee Emotions

At Delta, many emotions also emerged ().

Table 4. Emotions at delta (see also Harikkala-Lahinen, Citation2019, pp. 236–237).

The core of these emotions largely resembled the experiences at Alpha Group. Increased faith in the future triggered happiness and relief, whereas the accustomed best practices at Delta generated pride. This, however, turned to anger when it appeared that Gamma was offending the best practices. Employees experienced Delta’s future within Gamma as insecure and keenly felt a sense of loss over the old company. Overall, at Delta, negative emotions seemed more dominant.

People are tired and frustrated. I hear deep sighs and frustrated comments. (Diarist)

At Delta, individuals were concerned about their own jobs, groups were concerned over their immediate colleagues, and the pre-acquisition organization members over continuity. A strong us versus them attitude was visible, indicating that the post-acquisition we had not emerged.

Communication and Interaction

Delta employees appreciated company meetings that invited all the employees together once each quarter to hear the latest news. However, at Delta, employees did not experience that they had the ability to participate in the change, indicating that information sharing rather than interaction was the used communication strategy. The messages centred on day-to-day functional matters, and employees had a relatively passive role as recipients. Although the aim was keeping everyone informed, many employees experienced communication as sub-optimal. At the same time, employees were not purposefully engaged in acquisition-related interaction.

We can express our opinion, but so far it has had no influence. It is their [Gamma’s] rules, and we have to … [follow]. (Managing director)

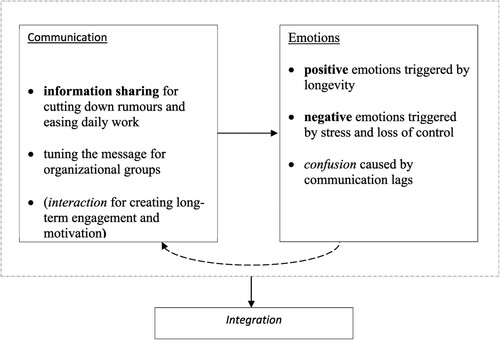

Delta employees also experienced the company strategy as foggy, discouraging them from extra effort toward change. The findings likely reflect the expected negativity in the acquired company facing change (e.g. Graebner et al., Citation2017). This may be a key reason why the integration at Delta triggered significantly fewer positive emotion experiences than was found at Alpha Group. Nevertheless, the suggested framework functions as an analytical tool also at Delta ().

Although at Delta information sharing was the main communication means, the organization was able to tune the message to employee needs, increasing communication when employees reported feelings of uncertainty. Perceived longevity thanks to the acquisition did trigger positive emotions, but negative emotions were – at least in the short term – more powerful due to a perceived loss of control and increased stress.

People are rather irritable and tired, and you can see that the positivity I always thought was our strength has decreased considerably. (Country manager)

This occurred even though management made great effort to improve the acquisition partners’ perceptions of each other and to hear employees’ worries. Nevertheless, the perceived distance of Gamma management downplayed the post-acquisition organization, maintaining Delta as the core of employees’ identification.

If they always say ‘them’, then it’s more challenging to grow together. I always pay very much attention to that. (Integration manager)

Thus, although Delta was able to achieve consistent, frequent communication (e.g. Angwin et al., Citation2016), the benefits of interaction were not reaped (cf. Clayton, Citation2010).

Discussion

Looking at the integration processes discussed above from a POS viewpoint, to create positive post-acquisition change, the management task centres on promoting change receptiveness and building commitment to the post-acquisition organization (cf. Caldwell, Citation2003). Portraying what is exciting and beneficial about the change for the employees (cf. Karp, Citation2004) and emphasizing these positive emotion triggers (cf. Cameron, Citation2008) enables managers to build positivity. This paves the way towards affirmative, positive change (cf. Avey et al., Citation2008; Whetten & Cameron, Citation2011).

Employees are likely to experience myriad integration-related emotions, which can at times be contradictory. Positive emotions such as happiness, relief and pride, as well as negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, sadness and jealousy are likely to emerge. At the same time, employees are likely to experience hope. Overall, based on the cognitive appraisal theory (e.g. Fredrickson, Citation2013; Lazarus, Citation1991), it seems that negative experiences following acquisitions reflect the uncertainty of the period, perceptions of offense against the employees or the pre-acquisition organization, or experiences of resentment due to perceived favouritism or inequality. Positivity, in turn, reflects perceptions of continuity and opportunity, a relieving of stress, or perceived credit in advancement. These findings increase understanding of emotions during acquisitions through offering a more balanced viewpoint, considering both positive and negative experiences (cf. Graebner et al., Citation2017).

The relationship between communication and emotion seems somewhat complex. As predicted (e.g. Sinkovics et al., Citation2011), communication arose as a central trigger for emotions both at Alpha Group and Delta. Open (cf. Angwin et al., Citation2016), frequent (cf. Weber et al., Citation2011) communication was valued and helped employees cope with uncertainty (cf. Appelbaum et al., Citation2000). Conversely, a lack of communication can also act as an emotion trigger, particularly increasing uncertainty and anxiety, possibly giving rise to rumour mongering. Thus, organizations can use communication strategically to influence emotions, for example through addressing issues, which are causing rumours.

Previous literature (e.g. Balle, Citation2008; Barrett, Citation2002; Lee, Citation1994; Lotz & Donald, Citation2006; Schweiger & Denisi, Citation1991) seems to best predict the effects and highlight the importance of traditional, top-down communication. This is essential for change efforts, because information can effectively decrease anxiety and enable smooth day-to-day functioning during stressful change periods. However, in terms of increasing positivity, it seems that interaction is more effective and important. Notably, the example of dialogue (cf. Bohm, Citation2003; Isaacs, Citation1999; Senge, Citation1990) found at Alpha Group highlights the motivating effect of engagement. Establishing dialogue in the interactive sense, for example through workshops like at Alpha Group, is a great effort. Thus, it is noteworthy that likely any other interaction mode would have similar results in triggering positivity.

Interaction is a means towards building unity: creating a sense of closeness and collaboration, which can help overcome the us versus them setting common following acquisitions. The key in using interaction to ease change is in utilizing humans’ innate preference for positive triggers (Cameron, Citation2008) and responsiveness to social contexts (Fiske & Taylor, Citation2013). This enables organizations to manipulate the change context to seem more positive (cf. Andersen & Guerrero, Citation1996), allowing the appearance of positive emotions (cf. Bar-tal et al., Citation2007; Hatfield et al., Citation1994).

Moreover, interaction increases employee engagement with the change process, thus triggering a sense of shared ownership of the process and its success. This further increases the motivating effect of interaction, as any subsequent success in the change process then becomes a source of pride, and a boost for one’s ego-identity. Nevertheless, interaction is likely to offer a fruitful arena for emotion contagion (cf. Barsade, Citation2002; Hatfield et al., Citation1994). Therefore, although organization-led change initiatives may well trigger positivity, informal coffee table discussions may equally well spread negative emotions. This again highlights the necessity of both information sharing and interaction following acquisitions.

Conclusion

Theoretical Contribution

This article has increased understanding of the emergence and influence of emotions in the change management literature (cf. Zietsma et al., Citation2019) through highlighting the link between different communication practices and resultant employee reactions. Moreover, this article builds understanding on how communication can be used to create a positive change climate (cf. Ashkanasy & Daus, Citation2002) and to overcome potential conflict (cf. Angwin et al., Citation2016; Weber & Drori, Citation2011). This article suggests that in order to create change-congruent behaviour, organizations can simultaneously decrease worries through traditional, top-down communication and increase positivity through interaction. Both are necessary for optimal change results. Information sharing can help organizations overcome potential conflict, but interaction will likely further the change agenda beyond the neutralizing effect. This shows the value of positivity over and above the negative.

More particularly, this study has shed light on collective emotion management during change periods (cf. Huy, Citation2012; Steigenberger, Citation2015) through different communication efforts. Although interaction is the key to positive emotion elicitation, information sharing is essential in alleviating worries, cutting down rumours and ensuring day-to-day functions. Thus, interaction will likely not be successful in creating positivity if information sharing is not in place. Through uncovering this novel insight into the dynamics of emotion elicitation in organizations (cf. Scherer & Moors, Citation2019), this article revealed that managing change in a positive way (cf. Canning & Found, Citation2015; Dixon et al., Citation2016) can occur through engaging both in information-sharing and interactive change communication. Consequently, this article reveals that facilitating positive emotions at work (cf. Allen & McCarthy, Citation2016) can occur, for example, through engaging employees in interactive, motivating communication endeavours.

Based on these insights, the relationship between emotions and communication in managing positive change is threefold. First, communication can alleviate negative emotions (information-sharing) and generate positive emotions (interaction). Second, emotions can guide communication efforts. For example, anxiety can be tackled through increased information-sharing. Third, management can use different communication tools purposefully to generate certain emotions. For example, interaction can be used to motivate and engage employees.

This article contributes to three aspects of change management: positive emotion elicitation, communication, and emotion management. First, this article lays the theoretical and practical groundwork for signalling the importance of interactive communication in generating positive change-related emotions. The sense of ownership and engagement created through interaction increases employee involvement, thus making every success more personal, encouraging change-congruent behaviour and the emergence of positive emotions. Second, this article introduces the different purposes of a more traditional, top-down communication style and a more interactive, engaging style. Whereas the first is necessary to maintain day-to-day functionality and cut down rumour mongering, the latter is a key means towards increasing employee motivation and commitment. Finally, this article shows how communication practices enable collective emotion management during change. Traditional communication can alleviate concerns and cut down rumours, thus decreasing negative emotions. To generate positive emotions, interaction can offer employees experiences of motivation, engagement and ownership.

Managerial Implications

Increased knowledge of how employees react to organizational changes allows practitioners to prepare for emotional experiences. The suggested framework can help practitioners plan and analyse their change efforts better, and to pay closer attention to the creation of a positive atmosphere likely to ease change processes. An increased understanding of emotions and their triggers allows practitioners to have an increased depth of perspective into their own change processes, encouraging them to help employees deal with change-related anxiety. This is important because employees are likely to have emotional reactions even to relatively minor changes. If practitioners can build a positive view of the future of the joint company, they can greatly enhance employee commitment and motivation for making the change a success. In doing so, understanding the necessity of different communication styles, including interaction, can be a great help.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The key limitation of this article stems from the chosen methodology. Although every effort to establish rigour advocated by other scholars (e.g. Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002; Järvensivu & Törnroos, Citation2010) has been made and detailed accordingly (e.g. Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Shenton, Citation2004), the abductive structure is somewhat unique and the weight of the arguments is based on only two cases. The article is potentially similarly limited by the affirmative bias inherent in POS as well as the friendly nature of the acquisitions studied. Thus, future research with more data from varied change contexts can help corroborate the findings. For example, it would be particularly interesting to explore positivity in hostile acquisitions or otherwise highly negative change experiences, such as following major layoffs.

In addition, deeper insight into the different communication means, both information sharing and interaction, may reveal important insights for change management in terms of boosting positivity. Similarly, differences in core affect (e.g. Russell, Citation2003) may influence the effectiveness of interventions, providing another avenue for future research. Finally, other scholars are encouraged to adopt a POS lens to exploring change management, as refocusing efforts from looking at potential problems to looking at success and vitality may reveal why current literature is inconclusive.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Professor Niina Nummela and Postdoctoral Researcher Johanna Raitis from Turku School of Economics at the University of Turku and Lecturer Melanie Hassett from University of Sheffield School of Management for their invaluable support.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Riikka Harikkala-Laihinen

Dr Riikka Harikkala-Laihinen is a Postdoctoral Researcher in International Business at the Turku School of Economics at the University of Turku, Finland. She defended her doctoral thesis ‘The power of positivity: How employee emotions and interaction can benefit cross-border acquisitions’ in September 2019. In her thesis, she explored how cognitive appraisal theory could be used to explain employee reactions during post-acquisition integration. It received the 2020 AIB-UKI Adam Smith Best Doctoral Dissertation Award. Her areas of expertise include emotions in organizations, cross-border acquisitions and cross-cultural management. Her current work centres on exploring the influence of employee emotions at work. She has published in Cross Cultural and Strategic Management and the Research on Emotions in Organizations book series. She has also coedited a volume on socio-cultural integration in the Nordic countries for Palgrave-Macmillan and published a Palgrave Pivot book on Managing Emotions in Organizations.

Notes

1 By positive, this study refers to an experienced quality: pleasure (e.g. positive emotions) as opposed to displeasure (e.g. negative emotions) (cf. Lazarus, Citation1991).

2 Despite their difference, the words ‘merger’ and ‘acquisition’ are often used interchangeably. However, as acquisitions are more common in practice (e.g. Raitis et al., Citation2017), this article mainly refers to ‘acquisitions’.

References

- Allen, M., & McCarthy, P. (2016). Be happy in your work: The role of positive psychology in working with change and performance. Journal of Change Management, 16(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2015.1128471

- Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2011). Generating research questions through problematization. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 247–271. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.59330882

- Andersen, P., & Guerrero, L. (1996). Principles of communication and emotion in social interaction. In P. Andersen & L. Guerrero (Eds.), Handbook of communication and emotion: Research, theory, applications, and contexts (pp. 49–96). Academic Press.

- Angwin, D. N., Mellahi, K., Gomes, E., & Peter, E. (2016). How communication approaches impact mergers and acquisitions outcomes. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(20), 2370–2397. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.985330

- Annosi, M. C., Magnusson, M., Martini, A., & Appio, F. P. (2016). Social conduct, learning and innovation: An abductive study of the dark side of agile software development. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(4), 515–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12172

- Appelbaum, S. H., Gandell, J., Yortis, H., Proper, S., & Jobin, F. (2000). Anatomy of a merger: Behavior of organizational factors and processes throughout the pre- during- post-stages (part 1). Management Decision, 38(9), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740010357267

- Appelbaum, S. H., Lefrancois, F., Tonna, R., & Shapiro, B. T. (2007). Mergers 101 (part one): Training managers for communications and leadership challenges. Industrial and Commercial Training, 39(3), 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197850710742225

- Arnold, M. (1960). Emotion and personality volume II: Neurological and physiological aspects. Columbia University Press.

- Ashkanasy, N. M. (2003). Emotions in organizations: A multi-level perspective. Research in Multi-Level Issues, 2, 9–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1475-9144(03)02002-2

- Ashkanasy, N. M., & Daus, C. S. (2002). Emotion in the workplace: The new challenge for managers. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2002.6640191

- Ashkanasy, N. M., & Dorris, A. D. (2017). Emotions in the workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113231

- Åsvoll, H. (2014). Abduction, deduction and induction: Can these concepts be used for an understanding of methodological processes in interpretative case studies? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(3), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2012.759296

- Avey, J. B., Wernsing, T. S., & Luthans, F. (2008). Can positive employees help positive organizational change? Impact of psychological capital and emotions on relevant attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(1), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886307311470

- Balle, N. (2008). Hearts at stake: A theoretical and practical look at communication in connection with mergers and acquisitions. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 13(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280810848193

- Barrett, D. (2002). Change communication: Using strategic employee communication to facilitate major change. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 7(4), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280210449804

- Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(4), 644–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094912

- Bar-tal, D., Halperin, E., & DeRivera, J. (2007). Collective emotions in conflict situations: Societal implications. Journal of Societal Issues, 63(2), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00518.x

- Basch, J., & Fisher, C. (1998). Affective events – emotions matrix: A classification of work events and associated emotions (Bond University School of Business Discussion Papers No. 65).

- Birkinshaw, J., Bresman, H., & Håkanson, L. (2000). Managing the post-acquisition integration process: How the human integration and task integration processes interact to foster value creation. Journal of Management Studies, 37(3), 395–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00186

- Bohm, D. (2003). On dialogue. Routledge.

- Burnes, B., & Jackson, P. (2011). Success and failure in organizational change: An exploration of the role of values. Journal of Change Management, 11(2), 133–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2010.524655

- Caldwell, R. (2003). Change leaders and change managers: Different or complementary? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24(5/6), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730310485806

- Cameron, E., & Green, M. (2012). Making sense of change management: A complete guide to the models, tools and techniques of organizational change. Kogan Page.

- Cameron, K. (2008). Paradox in positive organizational change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886308314703

- Cameron, K. (2012). Positive leadership: Strategies for extraordinary performance (2nd ed.). Berrett-Koehler.

- Cameron, K., & Caza, A. (2004). Contributions to the discipline of positive organizational scholarship. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764203260207

- Cameron, K., Dutton, J., & Quinn, R. (2003). Foundations of positive organizational scholarship. In K. Cameron, J. Dutton, & R. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 3–13). Berrett-Koehler.

- Canning, J., & Found, P. A. (2015). The effect of resistance in organizational change programmes: A study of a lean transformation. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 7(2/3), 274–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-02-2015-0018

- Carrera, P., & Oceja, L. (2009). Drawing mixed emotions: Sequential or simultaneous experiences? Cognition & Emotion, 21(2), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600557904

- Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C. L. (1993). The role of culture compatibility in successful organizational marriage. Academy of Management Perspectives, 7(2), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1993.9411302324

- Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C. L. (1995). Organizational marriage: “Hard” versus “soft” issues? Personnel Review, 24(3), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483489510089632

- Casper, A., Tremmel, S., & Sonnentag, S. (2019). The power of affect: A three-wave panel study on reciprocal relationships between work events and affect at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(2), 436–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12255

- Caza, B. B., & Caza, A. (2008). Positive organizational scholarship: A critical theory perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry, 17(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492607305907

- Choi, T. (2014). Rational and compassionate information processing: A conceptual framework for authentic dialogue. Public Administration Review, 74(6), 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12277

- Clarke, N., & Salleh, N. M. (2011). Emotions and their management during a merger in Brunei. Human Resource Development International, 14(3), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2011.585064

- Clayton, B. C. (2010). Understanding the unpredictable: Beyond traditional research on mergers and acquisitions. Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 12(3), 1–19.

- Cooper-Thomas, H. D., & Anderson, N. (2006). Organizational socialization: A new theoretical model and recommendations for future research and HRM practices in organizations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(5), 492–516. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610673997

- Cornelius, R. R. (2006). Magda Arnold’s thomistic theory of emotion, the self-ideal, and the moral dimension of appraisal. Cognition & Emotion, 20(7), 976–1000. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600616411

- Cornett-DeVito, M., & Friedman, P. (1995). Communication processes and merger success: An exploratory study of four financial institution mergers. Management Communication Quarterly, 9(1), 46–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318995009001003

- Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Datta, D. K. (1991). Organizational fit and acquisition performance: Effects of post-acquisition integration. Strategic Management Journal, 12(4), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120404

- De Dreu, C., Nijstad, B., & van Knippenberg, D. (2008). Motivated information processing in group judgment and decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(1), 22–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307304092

- Dhingra, R., & Punia, B. K. (2016). Relational analysis of emotional intelligence and change management: A suggestive model for enriching change management skills. Vision, 20(4), 312–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972262916668726

- Diener, E., Thapa, S., & Tay, L. (2020). Positive emotions at work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7(1), 451–477. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044908

- Dixon, M., Lee, S., & Ghaye, T. (2016). Strengths-based reflective practices for the management of change: Applications from sport and positive psychology. Journal of Change Management, 16(2), 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2015.1125384

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8

- Dubois, A., & Gibbert, M. (2010). From complexity to transparency: Managing the interplay between theory, method and empirical phenomena in IMM case studies. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2009.08.003

- Durand, M. (2016). Employing critical incident technique as one way to display the hidden aspects of post-merger integration. International Business Review, 25(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.05.003

- Dyer, W. G., & Wilkins, A. (1991). Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt. Academy of Management Review, 16(3), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.2307/258920

- Edmondson, A., & McManus, S. (2007). Methodological fit in management field research. Academy of Management Journal, 32(4), 1155–1179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586086

- Fink, G., & Yolles, M. (2015). Collective emotion regulation in an organisation – a plural agency with cognition and affect. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(5), 832–871. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-09-2014-0179

- Fiske, S., & Taylor, S. (2013). Social cognition: From brains to culture (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Fletcher, M., & Plakoyiannaki, E. (2011). Case selection in international business: Key issues and common misconceptions. In R. Piekkari & C. Welch (Eds.), Rethinking the case study in international business and management research (pp. 171–191). Edward Elgar.

- Folger, R., & Stein, C. (2017). Abduction 101: Reasoning processes to aid discovery. Human Resource Management Review, 27(2), 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.08.007

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 1–53). Academic Press.

- Fuchs, S., & Prouska, R. (2014). Creating positive employee change evaluation: The role of different levels of organizational support and change participation. Journal of Change Management, 14(3), 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2014.885460

- Gordon, R. (1987). Pivotal distinctions. In R. Gordon (Ed.), The structure of emotions (pp. 21–44). Cambridge University Press.

- Graebner, M. E., Heimeriks, K. H., Huy, Q. N., & Vaara, E. (2017). The process of postmerger integration: A review and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2014.0078

- Guerrero, L. K., Andersen, P. A., & Trost, M. R. (1996). Communication and emotion: Basic concepts and approaches. In P. Andersen & L. Guerrero (Eds.), Handbook of communication and emotion: Research, theory, applications, and contexts (pp. 3–27). Academic Press.

- Gunkel, M., Schlaegel, C., Rossteutscher, T., & Wolff, B. (2015). The human aspect of cross-border acquisition outcomes: The role of management practices, employee emotions, and national culture. International Business Review, 24(3), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.09.001

- Harikkala-Lahinen, R. (2019). The power of positivity: How employee emotions and interaction can benefit cross-border acquisitions. University of Turku.

- Harikkala-Laihinen, R. (2020). Rough winds? Emotional climate following acquisitions. In C. E. J. Härtel, W. J. Zerbe, & N. M. Ashkanasy (Eds.), Emotions and service in the digital age (research on emotion in organizations (Vol. 16, pp. 153–171). Bingley.

- Harikkala-Laihinen, R., Hassett, M., Raitis, J., & Nummela, N. (2018). Dialogue as a source of positive emotions during cross-border post-acquisition socio-cultural integration. Cross Cultural and Strategic Management, 25(1), 183–208. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-09-2016-0163

- Haspeslagh, P., & Jemison, D. (1991). Managing acquisitions: Creating value through corporate renewal. The Free Press.

- Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J., & Rapson, R. (1994). Primitive emotional contagion. In M. Clark (Ed.), Emotion and social behavior: The review of personality and social psychology (14th ed., pp. 151–177). Sage.

- Hurmerinta, L., & Nummela, N. (2011). Mixed-method case studies. In R. Piekkari & C. Welch (Eds.), Rethinking the case study in international business and management research (pp. 210–228). Edward Elgar.

- Huy, Q. N. (2012). Emotions in strategic organization: Opportunities for impactful research. Strategic Organization, 10(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127012453107

- Hyde, K. F. (2000). Recognising deductive processes in qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 3(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750010322089

- Isaacs, W. (1993). Taking flight: Dialogue, collective thinking, and organizational learning. Organizational Dynamics, 22(2), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(93)90051-2

- Isaacs, W. (1999). Dialogue and the art of thinking together. Currency.

- Izard, C. (1984). Emotion-cognition relationships and human development. In C. Izard, J. Kagan, & R. Zajonc (Eds.), Emotions, cognition, and behavior (pp. 17–37). Cambridge University Press.

- Järvensivu, T., & Törnroos, J. Å. (2010). Case study research with moderate constructionism: Conceptualization and practical illustration. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.05.005

- Karp, T. (2004). Learning the steps of the dance of change: Improving change capabilities by integrating futures studies and positive organisational scholarship. Foresight, 6(6), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636680410569920

- Kiefer, T. (2002). Understanding the emotional experience of organizational change: Evidence from a merger. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 4(1), 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422302004001004

- Kusstatscher, V. (2006). Cultivating positive emotions in mergers and acquisitions. Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, 5, 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-361X(06)05005-8

- Laros, F. J. M., & Steenkamp, J. E. M. (2005). Emotions in consumer behavior: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Business Research, 58(10), 1437–1445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.09.013

- Lazarus, R. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

- Lazarus, R. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245

- Lee, A. (1994). Hermeneutic interpretation electronic mail as a medium for rich communication: An empirical investigation using Hermeneutic Interpretation. MIS Quarterly, 18(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/249762

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

- Lotz, T., & Donald, F. (2006). Stress and communication across job levels after an acquisition. South African Journal of Business Management, 37(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v37i1.593

- Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. (2007). Emerging positive organizational behavior. Journal of Management, 33(3), 321–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300814

- Mandler, G. (1999). Emotion. In B. Bly & D. Rumelhart (Eds.), Cognitive science: Handbook of perception and cognition (2nd ed., pp. 367–384). Academic Press.

- Marks, M. L., & Mirvis, P. H. (2011). A framework for the human resources role in managing culture in mergers and acquisitions. Human Resource Management, 50(6), 859–877. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20445

- Menges, J. I., & Kilduff, M. (2015). Group emotions: Cutting the Gordian knots concerning terms, levels of analysis, and processes. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 845–928. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2015.1033148

- Morgeson, F., Mitchell, T., & Liu, D. (2015). Event system theory: An event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences. Academy of Management Review, 40(4), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0099

- Morrison, E. I. W. (2002). Newcomers’ relationships: The role of social network ties during socialization. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069430

- Nenonen, S., Brodie, R. J., Storbacka, K., & Peters, L. D. (2017). Theorizing with managers: How to achieve both academic rigor and practical relevance? European Journal of Marketing, 5(7/8), 1130–1152. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2017-0171