Abstract

MAD statement

This annual leading article is making a difference (MAD) through providing an overview of what is design and designerly thinking, and how these constructs may be of interest to organizational change management and leadership theory and practice. In doing so, we are setting out to support a transdisciplinary application of design thinking principles, methods and tools in the continuous development of organizational change and management capabilities, as well as leadership mindsets fit to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century.

Introduction

Design thinking:

where design practice and competence are used beyond the design context (including art and architecture), for and with people without a scholarly background in design, particularly in management. ‘Design thinking’ then becomes a simplified version of ‘designerly thinking’ [see below] or a way of describing a designer’s methods that is integrated into an academic or practical management discourse. (Johansson-Sköldberg et al., Citation2013, p. 123)

Designerly thinking:

the professional designer’s practice (practical skills and competence) and theoretical reflections around how to interpret and characterize this non-verbal competence of the designers. Designerly thinking links theory and practice from a design perspective, and is accordingly rooted in the academic field of design. (Johansson-Sköldberg et al., Citation2013, p. 123)

‘F*ck design thinking’. That was the title of renown design anthropologist Anna Kirah’s keynote at ‘From Business to Buttons’ – a user experience and service design conference held in the summer of 2022 in Stockholm, Sweden. For this, she received the best speaker award, and the talk was met with joy – but also anger and indignation from parts of the community. There are those who swear by ‘design thinking’ (DT), believers of its abundant impact on the world of business and wider society, and its ability of defining and solving the ‘right’ strategic problems (Cummings & Nickerson, Citation2021). Others believe it to be a reductionist commercialized practice far removed from the actual world of design.

Nonetheless, business and management communities alike have expressed an increasing interest in DT as a way of addressing the complexity of open-ended and ‘wicked’ challenges facing organizations in all sectors. Considering the uncertain and turbulent times in which we find ourselves – from pandemic to war, increasing energy costs and rising inflation – managers and leadership teams seek different ways of dealing with complexity in order to constantly adapt and improvise (Dorst, Citation2011; Lancione & Clegg, Citation2013; Tsoukas & Chia, Citation2002). Consequently, turning to DT may seem natural, as designers have a wide repertoire of ways of dealing with ill-structured problems and complex situations (Buchanan, Citation1992; Dorst, Citation2011). Yet, a question that emerges is: How might DT really enable decision making and innovation leadership in times of global headwinds and great uncertainty? And how may we apply more designerly ways of thinking, that leverages professional design (Björklund et al., Citation2020) in pursuit of purposeful and successful organizational change?

While DT and its potential have been on the radar since the early 1990’s, it only became widespread knowledge in the early 2000’s. However, despite ever-increasing evidence of its usefulness in innovation projects (Magistretti et al., Citation2022), especially in turbulent contexts (Nakata & Hwang, Citation2020), the organizational culture reform required to make it work to its full potential, and DTs role in radical innovation on direction is still unresolved (Buchanan, Citation2015; Magistretti et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, parts of the design community are sceptical to the use of ‘design’ in DT, believing that it moves design too far away from its core – and too close to management – and is as such changing the field of design itself (Kimbell, Citation2012; Verganti, Citation2017). To comprehend these ontological nuances, we trace some of the original definitions and foundations that shaped DT as a framework for innovation, before looking at the promising avenues of the potential role of DT in the continuous development of organizational change and management capabilities, and leadership mindsets embracing the uncertainty, risks and opportunities of our time. We propose that generalists of design thinking, design specialists and other disciplines join forces to navigate change and organizational challenges together. Furthermore, we propose design and designerly thinking as leadership mindsets in support of the tasks and challenges ahead.

What is Design Thinking?

Pluralism can be confusing at times, but the term ‘design thinking’ remains useful as long as the different meanings of design are understood (Buchanan, Citation2015, p. 13).

Traditionally, design was the realm of the genius, omnipotent, designer of tangible products and solutions. Early attention to DT focused on the cognitive style and abilities of individual designers, such as reflection-in-action (Schön, Citation1983) and abductive thinking (Dorst, Citation2006). The goal was to understand and make sense of professional design practice. However, the seminal work ‘Wicked problems in design thinking’ (Buchanan, Citation1992) propelled design into the world as a problem-solving approach that could tame wicked problems as a general theory; a way of ‘finding clarity in chaos’ if you like (Kolko, Citation2010, p. 15). Simultaneously, as the world was changing from a product-centred to an experience-centred, service-based economy (Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998), some designers moved their focus from ‘shaping plastics and metal, doorknobs and medical instruments’ to ‘shape interactions, systems and people’ (Wetter-Edman, Citation2014, p. 30) as digitalization became diffused into our lives (Verganti et al., Citation2021). Old ways of working became obsolete with the increasingly complexity of the world (Tsoukas & Chia, Citation2002).

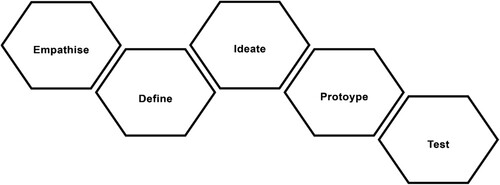

Many would relate DT to different stepwise frameworks postulated by world-leading innovation firm IDEO, published in Harvard Business Review, and taught at the Stanford d.school (e.g. ) (Bjögvinsson et al., Citation2012). Based on the core idea that ‘[t]hinking like a designer can transform the way you develop products, services, processes—and even strategy’ (Brown, Citation2008, p. 1), we have come to an understanding of DT as an organizational resource (Kimbell, Citation2012).

While this is a most recent development of the concept, it has roots back to the 1960’s and attempts to define a ‘design science’, where one analysed the environment (assumed to be stable) and devised courses of action to transform it into a more preferable state (Garud et al., Citation2009; Simon, Citation1969). However, it was now enriched by the previous notions of DT as a cognitive style and general theory – and as such avoided the most deterministic aspects of design science. As a result, DT is now often understood ‘as an approach to innovation and creative problem-solving based on designers’ processes and practices’ (Magistretti et al., Citation2022, p. 3; Martin, Citation2009), and widely recognized as ‘a specific way that non-designers evaluate and use design methods’ (Wrigley & Straker, Citation2017, p. 2),

Having said that, DT is still not fully understood ‘either by the public or those who claim to practice it’ (Kimbell, Citation2012, p. 288), and there are numerous frameworks presenting different steps, being one. However, there are ongoing disputes regarding DTs central attributes, applicability and outcomes by practitioners, advocates and critics (Liedtka, Citation2014; Micheli et al., Citation2019).

Most descriptions of DT centre around three main agreed-upon stages: (1) gathering data about user needs; (2) idea generation; and (3) testing (Liedtka, Citation2014). The first stage highlights DTs human-centred aspect, focusing on understanding and empathizing with human needs (Brown, Citation2009), often borrowing methods and approaches from anthropology (Beckman & Barry, Citation2009; Murphy & Marcus, Citation2013). Here, the practice involves need-finding tools (e.g. 1-3, ) that ‘require individuals to empathetically engage in learning about the user experience’ (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018, p. 2280). The second stage focuses on synthesis of data, and the principal DT attribute of creativity, as design problems ‘demand creative ideating’ (Brown, Citation2009; Magistretti et al., Citation2022; Micheli et al., Citation2019, p. 10). Here, idea-generation tools (e.g. 4–6, ) can lead to the development of new ideas. The third and final stage revolves around experimentation and testing. The stages are often characterized as being non-linear, reflecting the uncertainty of the process while maintaining flexibility and pragmatism.

Table 1. Attributes and tools of DT sorted by frequency in data set (Micheli et al., Citation2019, pp. 9–14).

Based on their meta study, and as captured in , Micheli et al. (Citation2019) summarized the attributes and tools associated with DT.

While the content of the steps alone does not bring anything new to the world of organizational change, management or leadership, in combination a distinctive practice emerges ‘bringing analytic and creative thinking modes together in a hypothesis-driven process that creates a unique journey for innovators at a personal level, which integrates emotion, cognition, and learning in action’ (Liedtka, Citation2020, p. 58). The world in which organizations operate is increasingly complex, chaotic and risky, and it’s safe to say that traditional ways of working – and we would suggest managing and leading – are no longer sufficient (Kimbell, Citation2012; Tsoukas & Chia, Citation2002). Herein lies perhaps the biggest promise of DT, as a new way to address and adapt to volatility, uncertainty and risk so naturally surrounding us: a way of dealing ‘intelligently with uncertainty, when existing data are inadequate and the ability to make predictions is suspect’ (Liedtka, Citation2020, p. 55).

Enabling Organizational Change, Management and Leadership

One may ask: does DT work? In early writings on DT, ‘enthusiastic efforts to understand design thinking were punctuated by anecdotal evidence and rushed forward with minimal attention to the theoretical background that underpinned the concepts’ (Verganti et al., Citation2021, p. 604). As such, early critique of DT was due to lack of evidence, as ‘attention to the specific mechanisms through which “design thinking” as a problem-solving approach improves business outcomes has been scant’ (Liedtka, Citation2014, p. 926).

Now, research provides a steady flow of evidence on the benefits of DT for organizations (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018). Nakata and Hwang (Citation2020, p. 117), defining DT as consisting of six inter-related mindsets and actions, found that it ‘strengthens new product and service performance, and has robust effects across levels of market turbulence’. In a study of DT in innovation projects at consulting firms, Magistretti et al. (Citation2022) found that basing solutions on the current needs of users (stage 1) aligns with the ability to innovate on product and services. Several reports have also found a positive relationship between design centricity and economic advantage (Buchanan, Citation2015). Drawing on 10 years of field research, Liedtka (Citation2020, p. 54) found that combinations of DT elements ‘created a set of strategically valuable dynamic capabilities critical for innovation and adaptation’, related to sensing, seizing and transforming (Liedtka, Citation2020, p. 54). For those involved in innovation, its methods, tools and mindsets also fostered learning, creativity and collaboration. Additionally, DT helped shape emotional and social experiences important for overcoming psychological barriers understood to impede the development of said dynamic capabilities.

As such, applying DT in practice is more than solving design and innovation problems. It presents a mindset, methods and tools with the potential to enable organizational change (Björklund et al., Citation2020). It fits well with By’s (Citation2021, p. 30) notion of leadership as cocreation, diversity and inclusion, being ‘a responsibility of the many, not a privilege of the few’ and as ‘the collective pursuit of delivering on purpose’. Also, the idea has been picked up by management scholars who point to the need to design organizations, and for managers to be designers (e.g. Senge, Citation2006). Buchanan (Citation2015, p. 20) argues that management is a logical extension of DT, and its true value ‘is its ability to focus the attention of organizations on all of the people served by the organization’ beyond profit. Furthermore, Elsbach and Stigliani (Citation2018) found a reciprocal relationship between the use of DT tools and organizational culture. Cultures with values, norms and assumptions open to DT practices fostered the use of DT tools, and vice versa. Cultures without hindered their use. They also found that physical artefacts and emotional experiences produced by such tools, and explicit reflections upon how and why these tools were used were important prerequisites for successful organizational adoption.

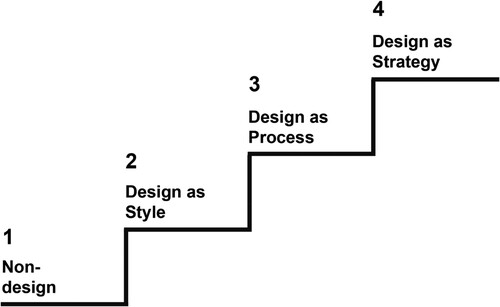

Tools such as the ‘Design ladder’ by the Danish Design Council (Kretzschmar, Citation2003) () describes the organizations’ design maturity ranging from (1) non-use of design, to (2) applying it for styling and/or ergonomics, as (3) a process with the services or products as outputs, to (4) being ‘integral to a company’s continuous renewal of their business concept as a means of encouraging innovation’ (Wrigley & Straker, Citation2017, p. 3). Design-led organizations (not necessarily by designers) embed design throughout the firm, and ‘share four qualities: a culture that values curiosity; cross-functional empathy; the designer as constant ethnographer; and the physical manifestation of the brand through design’ (Beverland & Farrelly, Citation2007, p. 10). There is indeed a close relationship between DT and culture. More than solving design and innovation problems, DT can influence the values, norms and assumptions about ways of working in the organization, significantly altering the organization culture (Buchanan, Citation2015; Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018; Kolko, Citation2015).

Figure 2. The Danish Design Ladder (Kretzschmar, Citation2003).

While Magistretti et al. (Citation2022) found that DT aligns with innovating on solutions, it did not necessarily align with innovating on direction. Indeed, ‘we still lack an understanding of how design thinking, as a set of practices, might become an essential cultural component of organizations’ (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018, p. 2277), and the actual introduction of DT into organizational management is in its infancy (Buchanan, Citation2015).

Making it Work: From Design to Designerly Thinking

DT is often muddled with the entire practice of design (Verganti et al., Citation2021).

In order to migrate into the world of business and be theorized, design through DT had to distance itself from the messiness of improvised creativity and intuition (Lindgaard & Wesselius, Citation2017). This meant it

had to undergo a lobotomy that rendered it guts-free, aesthetics-free. And this lobotomy succeeded in exciting managers. They loved it, so analytic, so procedural, and so controllable … Guess why? (Verganti, Citation2017, p. 101)

To make design thinking palatable to citizens of the business world, most advocates of what is labeled ‘design thinking’ have articulated design as a set of clearly articulated processes and methods, packing it into 5-step processes, double diamonds, brainstorming, quick ethnography, empathy maps, customer journeys, blueprints, and the like. This enables them to bring design closer to the language of business schools and the managerial palate. (Verganti, Citation2017, p. 101)

However, for organizations to move up the design ladder to higher level design maturity also requires deep design expertise (Björklund et al., Citation2020), and real innovation can only take place where organizations accept the ‘mess’ along with the process. This might require organizations to embrace not only design thinking, but designerly thinking, more concerned with professional design and designers. According to Johansson-Sköldberg et al. (Citation2013), DT and designerly thinking can be categorized into five sub-discourses: (1) DT and designerly thinking as the creation of artefacts (based on Simon, Citation1969); (2) DT and designerly thinking as a reflexive practice (based on Schön, Citation1983); (3) DT and designerly thinking as a problem-solving activity (based on Buchanan, Citation1992); (4) DT and designerly thinking as a way of reasoning/making sense of things (based on Cross, Citation2006, Citation2011; Lawson, Citation2006); and (5) DT and designerly thinking as creation of meaning (Krippendorff, Citation2006).

Indeed, professional designers could influence the wider organization through strategic design, which could be defined as:

designers’ ability to influence decisions and set direction over issues that affect the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of an organization, such as development and communication of a brand’s core values, positioning, and creation of new markets. (Micheli et al., Citation2018, p. 2)

In their study of designers, design managers and design business leaders within technology, Björklund et al. (Citation2020) found that there are two types of design capabilities which could mediate friction, which need to coevolve in the organization. The first is an investment in deep design expertise through having multiple design professionals in the organization who works human-centred and question-driven. This could be leveraged by for example recruiting a variety of design disciplines and having a healthy design budget, avoiding the stepwise superficial DT and rather obtain the benefits of the craft. Micheli et al. (Citation2019) also argue that it is important to articulate design’s unique contribution towards strategic goals of the organization, and that they should be able to join cross-functional teams.

Beverland and Farrelly (Citation2007) believe that in order to contribute to the action required to make organizations design-led, professional designers need to build bridges between functions, drop the ego (star-designer syndrome) and tie DT to actual business outcomes. However, there are downfalls here, for example only leveraging design as means of generating economic value, and employees going through mass-training and start appearing as ‘objectified bundles of capacities’ (Lee, Citation2021, p. 503). Indeed, it should not be leveraged as an innovation fad (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018), which its ontological confusion might make it a subject for (Lancione & Clegg, Citation2013). More in line with By’s (Citation2021) work on leadership as a collective responsibility, DT can be viewed and embraced as a mindset.

[o]rganizations also need a broader group of design thinkers and a widespread understanding of design to allow designers to effectively practice their trade and to benefit from the full range of expertise inside the company. (Björklund et al., Citation2020, p. 7)

Conclusion

In this annual leading article, we have taken a dive into some of the ontological confusions of DT. Leveraging DT for innovation might require employees – including managers – that think like designers, other functions to understand the unique qualities of design, organizational processes to balance formalization and flexibility, and cultures to afford non-linear and human-oriented ways of thinking and working (Buchanan, Citation2015; Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018; Micheli et al., Citation2019). However, DT in its current form might also hinder change: basing our interventions on what we already know and established frameworks, while finding ourselves in a dramatic transition where we must rather question ‘the inner nature of how we see problems’ (Verganti et al., Citation2021).

It might also require embracing designerly ways of thinking and working through deep design expertise (Björklund et al., Citation2020), avoiding the reductionist approach of ‘DT for business’. Consequently, DT and designerly thinking might best operate and coevolve together: ‘practices of designers play important roles in constituting the contemporary world, whether or not ‘design thinking’ is the right term for this’ (Kimbell, Citation2012, p. 301). Indeed, contemporary challenges will require reflection over iteration and systemic approaches over user-centredness, which might render the current version of DT obsolete unless enriched (Verganti et al., Citation2021).

The role of design and designerly thinking in organizational change, management and leadership requires further attention. An organization is not like a product to be altered, but has a social fabric, and ‘conventional design practice in organizations (and even more so for design consultants) typically does not provide guidance on how to recognize and navigate the warp and weft of the organization’s social fabric’ (Lee, Citation2021, p. 507). Current design tools and practices, even attributes, are not necessarily equipping us to deal with ‘multi-stakeholders and multi-framework contexts’, and a way forward could be to include reflective approaches (i. e. system thinking and critical thinking) that allow for multiple perspectives and appreciate the emergent nature of change (Verganti et al., Citation2021, p. 618; Lancione & Clegg, Citation2013). Thus, designerly thinking might enrich design thinking, as it can be concerned with reflection, both in action and in retrospect as part of professional design practice (Sarwar & Fraser, Citation2019; Schön, Citation1983).

Furthermore, those indignant by Anna Kirah’s 2022 keynote were those who only paid attention to the title. Her main argument was rather that, ‘design thinking is not really “design thinking’ but ‘transdisciplinary thinking and doing”. The ability to facilitate change requires working together with different mindsets’ (A. Kirah, personal communication, 20 January 2023). Indeed, when applying DT as a non-designer, one is already acting transdisciplinary. In that regard, we propose that both generalists of design thinking, design specialists and other disciplines join forces to navigate change and organizational challenges together. Referring back to Clegg et al.’s (Citation2021) article observing the need for changing leadership in changing times, design and designerly thinking as mindsets may very well support and reframe the way we see and do leadership.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Beckman, S., & Barry, M. (2009). Design and innovation through storytelling. International Journal of Innovation Science, 4(1), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1260/1757-2223.1.4.151

- Beverland, M., & Farrelly, F. J. (2007). What does it mean to be design-led? Design Management Review, 18(4), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2007.tb00089.x

- Bjögvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P.-A. (2012). Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges. Design Issues, 28(3), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00165

- Björklund, T., Maula, H., Soule, S. A., & Maula, J. (2020). Integrating design into organizations: The coevolution of design capabilities. California management review, 62(2), 100–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619898245

- Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 84–92.

- Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking can transform organizations and inspire innovation. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Brown, T. (2015). When everyone is doing design thinking, is it still a competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/08/when-everyone-is-doing-design-thinking-is-it-still-a-competitive-advantage

- Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked problems in design thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637

- Buchanan, R. (2015). Worlds in the making: Design, management, and the reform of organizational culture. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 1(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2015.09.003

- By, R. T. (2021). Leadership: In pursuit of purpose. Journal of Change Management: Reframing Leadership and Organizational Practice, 21(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1861698

- Clegg, S., Crevani, L., Uhl-Bien, M., & By, R. T. (2021). Changing leadership in changing times. Journal of Change Management: Reframing Leadership and Organizational Practice, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1880092

- Cross, N. (2006). Designerly ways of knowing. Springer Verlag.

- Cross, N. (2011). Design thinking. Berg.

- Cummings, T., & Nickerson, J. (2021). A protocol mechanism for solving the ‘right’ strategic problem. Strategic Management Review.

- Dorst, K. (2006). Design problems and design paradoxes. Design Issues, 22(3), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi.2006.22.3.4

- Dorst, K. (2011). The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Design studies, 32(6), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006

- Elsbach, K. D., & Stigliani, I. (2018). Design thinking and organizational culture: A review and framework for future research. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2274–2306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317744252

- Garud, R., Jain, S., & Tuertscher, P. (2009). Incomplete by design and designing for incompleteness. Organization Studies, 29(3), 137–156.

- Johansson-Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., & Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design thinking: Past, present and possible futures. Creativity and Innovation Management, 22(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12023

- Kimbell, L. (2012). Rethinking design thinking: Part I. Design and Culture, 4(2), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.2752/175470812X13281948975413

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press.

- Kolko, J. (2010). Abductive thinking and sensemaking: The drivers of design synthesis. Design Issues, 26(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi.2010.26.1.15

- Kolko, J. (2015). Design thinking comes of age. Harvard Business, 93(9), 66–71.

- Kretzschmar, A. (2003). The economic effects of design. Danish National Agency for Enterprise and Housing.

- Krippendorff, K. (2006). The semantic turn: A new foundation for design. Taylor and Francis.

- Lancione, M., & Clegg, S. (2013). The chronotopes of change: Actor-networks in a changing business school. Journal of Change Management, 13(2), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2012.753930

- Lawson, B. (2006). How designers think: The design process demystified (4th ed.). Architectural Press.

- Lee, K. (2021). Critique of design thinking in organizations: Strongholds and shortcomings of the making paradigm. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 7(4), 497–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2021.10.003

- Liedtka, J. (2014). Perspective: Linking design thinking with innovation outcomes through cognitive bias reduction. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(6), 925–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12163

- Liedtka, J. (2020). Putting technology in its place: Design thinking’s social technology at work. California management review, 62(2), 53–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619897391

- Lindgaard, K., & Wesselius, H. (2017). Once more, with feeling: Design thinking and embodied cognition. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 3(2).

- Magistretti, S., Bianchi, M., Calabretta, G., Candi, M., Dell’Era, C., Stigliani, I., & Verganti, R. (2022). Framing the multifaceted nature of design thinking in addressing different innovation purposes. Long Range Planning, 55(5), 102163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2021.102163

- Martin, R. L. (2009). The design of business: Why design thinking is the next competitive advantage. Harvard Business Press.

- Micheli, P., Perks, H., & Beverland, M. B. (2018). Elevating design in the organization. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(4), 629–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12434

- Micheli, P., Wilner, S. J. S., Bhatti, S. H., Mura, M., & Beverland, M. B. (2019). Doing design thinking: Conceptual review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(2), 124–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12466

- Murphy, K. M., & Marcus, G. E. (2013). Epilogue: Ethnography and design, ethnography in design … ethnography by design. In W. Gunn, T. Otto, & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Design anthropology: Theory and practice (pp. 251–268). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Nakata, C., & Hwang, J. (2020). Design thinking for innovation: Composition, consequence, and contingency. Journal of business research, 118, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.038

- Nussbaum, B. (2011, April 5th). Design thinking is a failed experiment. So what’s next? https://www.fastcompany.com/1663558/design-thinking-is-a-failed-experiment-so-whats-next

- Pine, J. I., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review.

- Sarwar, A., & Fraser, P. T. (2019). Explanations in design thinking: New directions for an obfuscated field. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 5(4), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.11.002

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. Basic Books.

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Broadway Business.

- Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. MIT Press.

- Tsoukas, H., & Chia, R. (2002). On organizational becoming: Rethinking organizational change. Organization Science, 13(5), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.5.567.7810

- Verganti, R. (2017). Design thinkers think like managers. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 3(2), 100–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2017.10.006

- Verganti, R., Dell’Era, C., & Swan, K. S. (2021). Design thinking: Critical analysis and future evolution. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(6), 603–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12610

- Wetter-Edman, K. (2014). Design for service: A framework for articulating designers’ contribution as interpreter of users’ experience [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/35362

- Wrigley, C., & Straker, K. (2017). Design thinking pedagogy: The educational design ladder. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2015.1108214