ABSTRACT

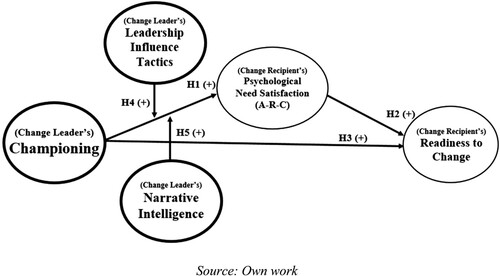

Change agents influence employee attitudes in order for organizations to change. In an effort to unravel this influence mechanism, we examined the change leader-recipient relationship. More specifically, how change leaders’ championing (independent variable) relates to recipients’ readiness to change (dependent variable). Our conceptual model of change leaders’ prosocial sensegiving is based on adult attachment theory operationalized through storytelling. To test our model, we surveyed 164 change recipients undergoing organizational change in various industries. Results confirm the first part of our model: psychological need satisfaction partially mediates the relation between change leaders’ championing and recipients’ readiness to change. In other words, prosocial change leaders act as attachment figures alleviating anxiety caused by ambiguity addressing change recipients’ proximity-seeking behaviour. Despite what has been described in scholarly works, change leaders’ methods of persuasion seem to be a more accurate indicator of recipients’ readiness for change. Part two of our hypothesized model could not be confirmed: moderation effects of leader influence and narrative intelligence could not be confirmed. We conclude that prosocial change leaders’ who demonstrate narrative intelligence use stories to elicit an emotional response from change recipients, effectively increasing their perceived psychological need satisfaction, ultimately affecting their readiness to change.

MAD statement

Our research aims to deconstruct the underlying mechanics of prosocial organizational change leadership. We study how change leaders utilize championing, narrative intelligence and leadership influence tactics in an effort to influence change recipients’ change-related attitudes and affect their individual readiness to change. We confirm that change recipients’ psychological need satisfaction partially mediates this relationship and that the direct application of leadership influence tactics is a better predictor, contrary to what literature suggests. We recommend practitioners create compelling narratives in an effort to enhance message reception, and utilize specific leadership influence tactics to ensure the message is received.

Humans are prone to homeostasis and fallible by nature. Most organizational change efforts fail despite organizations addressing common challenges and utilizing different influential methodologies through change agents (e.g. Battilana & Casciaro, Citation2012). A rising stream of literature studying organizational change failure emphasizes its inevitability (e.g. three perspectives from Schwarz et al., Citation2021 and an identity-forming perspective from Hay et al., Citation2021). Similarly, Heracleous and Bartunek (Citation2021) observed organizational change failure through a multilevel lens and concluded that certain short-term failures were necessary for major organizational change to be successful. These perspectives emphasizing organizational learning suggest that organizational change should be observed as discourse in which arguments are accepted or refuted among the targeted population during the construction of meaning in social contexts (the sensemaking process; Bandura, Citation1989). Change leaders play a crucial role here, as their influential efforts alter the perception of proposed arguments. Thus, we observe the change leader–change recipient dyadic relationship through the lens of social-cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1989). More precisely, we perceive it as an endless loop of reciprocal and sequential processes of influencing the way others interpret a certain context (sensegiving) and sensemaking (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991). We operationalize the change leader as a position with the highest knowledge of proposed change, sharing knowledge by managing change as a process, akin to innovation diffusion. Literature on innovation management suggests that change leaders should lead by example and demonstrate Champion Behaviour (abbreviated CB, Baer, Citation2012; Howell & Higgins, Citation1990). Other literature perspectives suggest relying on power and Leadership Influence Tactics to drive change (Battilana & Casciaro, Citation2021; Furst & Cable, Citation2008). Unlike Champion Behaviour, Leadership Influence Tactics (abbreviated LITs) focus on perception and utilize different communication and power perspectives in an effort to influence how certain organizational incidents and consequent behaviours are perceived by change recipients (Yukl et al., Citation1993; Yukl & Falbe, Citation1990). Change recipient role is observed as having less familiarity with the proposed change, susceptible to subjective and affective interpretation of organizational narratives in perceiving threats and benefits from proposed change.

Organizational change equals human endeavour. A change leader’s narratives effectively influence how organizational realities could be interpreted during the sensemaking process, driven by their efforts aimed to influence and mobilize networks of change recipients (e.g. Battilana et al., Citation2010). By building a coalition of affectively engaged supporters, change leaders are able to utilize political behaviour as a catalyst (Battilana & Casciaro, Citation2013), instead of relying solely on utilizing proposed change management methodologies which focus on communication (e.g. Appelbaum et al., Citation2012). Through the proposed hypothesized moderated mediation model, we observe how change leaders’ sensegiving efforts are perceived during change recipients’ sensemaking. Natural response to change is resistance, because ideologies change as well as workplace realities. Humans simply prefer homeostasis. Change leaders address change recipients’ previously made sense of ongoing change (Oreg, Citation2003, Citation2006), where stronger ties and affective cooptation increase their resistance to change (Battilana & Casciaro, Citation2013). On the other hand, change causes ambiguity and uncertainty causes strong emotional reactions such as stress, fear and anxiety, triggering the human tendency to discover answers and thus relieve stress and anxiety (Maitlis & Sonenshein, Citation2010). In situations where answers are not readily available or non-existent, individuals often construct their own version of reality, which may be entirely contradictory to the actual reality (Weick, Citation1988). Seeking meaning and understanding one’s own identity through group membership (Tajfel, Citation1982) heavily relies on others’ friendly faces. This proximity-seeking mechanism offers comfort and security (Mawson, Citation2005), unlike turning to facts and rationale intensive communication. Seeking social proximity in times of distress is a natural reaction (Mawson, Citation2005) because the calming effect closeness to attachment figures stimulates dopamine, thus reducing negative emotions associated with intensive ambiguity (Coan, Citation2008) and effectively enhancing sensemaking. In other words, rational communication of information fails short in addressing emotional needs of change recipients.

We hypothesize that storytelling shapes organizational change perception. In general, leading change can be characterized as an extensive communication effort to give sense to change through anticipating and addressing conflicts arising from recipients’ diverging needs and perceptions (Appelbaum et al., Citation2012; Mento et al., Citation2002). This sensegiving process is essentially defined as the act of telling stories, more precisely as influencing the way others interpret a certain context and understand desirable behavioural patterns (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991). Through a meta-analysis of organizational change storytelling literature, five main themes were identified, sensemaking, power and identity among others (Rhodes & Brown, Citation2005). These common themes highlight core problems during organizational change, but also the direction of change leaders’ communication. This is where change leaders’ Narrative Intelligence (abbreviated as NI) plays an essential role. In general, a story is a means by which people comprehend the world (Bruner, Citation1991), and Narrative Intelligence is the ability to tell the story of an individual’s life and the surrounding environment (Randall, Citation1999). Narrative Intelligence, among other types of intelligence, includes the ability to employ, characterize and narrate (Pishghadam et al., Citation2011), suggesting that effective storytellers create emotionally engaging stories by being more narratively intelligent. Emotionally engaging stories trigger dual-hemisphere information processing in the brain (Aldama, Citation2015; Taggart & Robey, Citation1981), effectively enhancing sensemaking. Social-cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1989) represents the overarching perspective of hypothesized relationships, which connects the sensegiving and sensemaking mechanisms between change leaders and change recipients during organizational change. Change leaders demonstrate and instruct desired social cues and help with socialization in new ideological settings of the organization through sensegiving, while change recipients interpret these cues and construct their own understanding of organizational ideology. Change recipients can accept these instructions or resist them, adjusting their personal identities through ideological social identification. Tajfel’s (Citation1982) social identity theory addresses these dynamics and open up space for a meaningful discussion in terms of understanding how underlying mechanisms of change leaders’ influencing efforts unfold.

Drawing parallels from similar relationships where knowledge of the future is shared between actors, more knowledgeable actors comfort actors experiencing anxiety. This behaviour can be perceived in teacher-student relationships but also in mentor-mentee; coach-athlete; and parent–child relationships. It is also present in more mainstream discourse such as social media platforms, where influencers perceived as human brands (Thomson, Citation2006) increase their influence by encouraging stronger attachment formation through enhancement of psychological need satisfaction (La Guardia et al., Citation2000). Furthermore, adult attachment formation (Grady & Grady, Citation2013) outlines more broadly how influential mechanisms may unfold, as different early childhood experiences define an individual’s attachment style. Outside romantic relationships, different adult attachment styles determine how actors exchange information and collaborate thus creating different fitting or misfitting combinations of styles. Furthermore exploring this dynamic, we turn to self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan (Citation1995), where an individual’s perception of Psychological Need Satisfaction in a relationship, determines the satisfaction with the relationships. In other words, Psychological Need Satisfaction (abbreviated PNS) represents the strength of attachment to the attachment figure and the willingness to contribute to that relationship between actors. Additionally, we argue that a change leader’s prosocial approach to change leadership relies on adult attachment formation and the strength of this attachment. In this contextual setting, a change leader is an attachment figure, investing effort in alleviating change recipients’ emotional distress caused by organizational change. Because attachment formation relies on interactions between actors, we argue that change leaders have the power to influence these interactions with a prosocial approach and therefore contribute towards the humanization of organizational change. More specifically, change leaders can utilize championing (CB), different leadership influence tactics (LITs) and narrative intelligence (NI) to alter existing narratives and address change recipients’ concerns more adequately. By doing so, they are enhancing change recipients’ perception of autonomy, relatedness and competence. In this hypothesized relationship, the greater the attachment between individuals, the greater the level of preparedness for change among those who receive the change.

The Mediating Effect of Building of Building Attachment with Change Recipients

Organizational change sensemaking is a personal experience. Change recipients tend to perceive change initiatives as threats (Balogun & Johnson, Citation2005; Ford et al., Citation2008) rather than as benefits, further emphasizing how change leaders’ efforts are crucial for successful change implementation. Champions of innovation (i.e. change leaders), are people who are expected to inspire and mobilize change adoption across different organizational levels by utilizing available resources and intensively advocating for change in a meaningful way (Škerlavaj et al., Citation2016). Unlike LITs which affect the perception of certain behaviours, CB exemplifies the desired behaviour, displaying persistence during hard times, engaging the right people, and promoting the positive aspects of change (Howell & Higgins, Citation1990). These behavioural cues of leading by example from change leaders can be perceived as a form of sensegiving (e.g. Sparr, Citation2018), signalling desired behavioural patterns to change recipients during the sensemaking processes. Change recipients seek comfort and security from authority figures (Richards & Schat, Citation2011) in hopes of alleviating negative emotions (Maitlis & Sonenshein, Citation2010) and accessing guidance regarding behavioural uncertainties. This in turn reduces ambiguity (Wood & Bandura, Citation1989) and builds trust (Vakola et al., Citation2013). Moreover, close interactions inevitably affect the strength of a relationship between change recipients and change leaders (Davidovitz et al., Citation2007) and during organizational change, leaders often serve as attachment figures (Davidovitz et al., Citation2007). Change leaders therefore simultaneously offer cognitive and emotional support to change recipients.

PNS reflects the fundamental motivation of individuals behind pursuing certain actions, such as change adoption (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Utilizing a prosocial approach to change leadership may enable change leaders to build stronger attachment in the context of organizational change adoption, when applying this psychological indicator of adult attachment. Demonstration of CB and addressing change recipients’ emotional distress and satisfying their need for autonomy, relatedness and competence, determines how strong of an attachment will be formed between change leaders and change recipients, based on their perception of relationship quality. Members of high-quality relationships are willing to adjust their attitudes based on attitudes of their attachment figure (Houran et al., Citation2005) because of highly perceived PNS (La Guardia et al., Citation2000).

Change recipients seek relatedness in their interpersonal relationships; therefore, depending on the combination of attachment styles, leaders perceived as attachment figures can even become idealized (Davidovitz et al., Citation2007). Relationships in which PNS is positively perceived are considered to be stronger than those where PNS is negatively perceived (Ryan, Citation1993), suggesting that change leaders will be able to exert more influence in relationships where change leader and change recipients demonstrate stronger attachment. More specifically, change leaders who lead by example and demonstrate CB are more likely than those who do not to positively affect change recipients’ PNS, as stated in Hypothesis 1:

Hypothesis 1. Change leaders’ demonstration of CB has a positive relationship with change recipients’ PNS during organizational change.

Sensegiving reception depends on attachment strength. As organizational change unfolds, change recipients need for affection can, depending on context, closely resemble a parent–child relationship (Grady & Grady, Citation2013), where change leaders act the role of parents alleviating ambiguity-driven anxiety. Different attachment styles result in different levels of leader–member exchange (LMX) quality (Schyns, Citation2015); however, in line with Gottfredson et al. (Citation2020), we move away from this perspective. Despite recent conversation on the validity of LMX as a measure, we conclude that securely attached individuals tend to be engaged in more functions and have higher affiliation and support needs than others (Richards & Schat, Citation2011). Relatively strong attachments can occur when a change leader is responsive to change recipients’ needs for autonomy, relatedness and competence (e.g. Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) during the emotional experience of organizational change. In other words, change recipients self-determine how satisfied their psychological needs are, resulting in different attachment strength, depending on attachment style fitness between actors.

Change leaders’ efforts to meet these psychological needs would imply that a change recipient (a) has enough space to autonomously decide what actions to take when dealing with change, (b) feels related to the change leader and the implementation team (i.e. has a sense of belonging) and (c) feels sufficiently competent to deal with change-related tasks. Weick (Citation1988) mentioned the importance of self-efficacy regarding seeing oneself as capable of addressing change and minimizing change resistance. Change recipients’ perception of PNS, determines the extent to which the change leaders as attachment figures can influence the change recipients’ individual Readiness to Change. In other words, change recipients’ susceptibility to attachment figures encourages identity modifications (Fransen et al., Citation2015; Harms, Citation2011).

Individual Readiness to Change (abbreviated RTC) designates the degree of mental, psychological, and physical preparedness of a change recipient to embrace the new organizational circumstances (Vakola et al., Citation2013). Change recipients subjectively perceive these dimensions, resulting in varied interpretations of the benefits and threats of change in organizational settings. Therefore, change leaders should identify the gap between change recipients’ expectations and proposed changes to decrease negative emotions resulting from perceived threats of said changes (Holt et al., Citation2007). We thus hypothesize that change recipients who perceive relatively high PNS are more likely than those who perceive relatively low PNS to feel more ready to change, as stated in Hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 2. During organizational change, change recipients’ PNS has a positive relationship with their RTC.

Strong attachment reduces resistance. Previous research on change recipients’ RTC suggests that it can be affected by various factors, and we introduce PNS as another factor to consider. A multilevel perspective of predictors of RTC includes both organizational and individual factors, such as job demands, employer and employee relationships, employee relations, organizational climate, employee skills, self, family, health and demographic specifics (Oreg et al., Citation2011). Recent research on the individual factors that influence change recipients’ RTC suggest that psychological capital is the most crucial psychological resource during organizational change reflected through self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience and affecting individual performance (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, Citation2017). Psychological capital can also mediate the organizational climate and employee performance relationships, both fairly well-known antecedents of change recipients’ RTC (Luthans et al., Citation2008). While we acknowledge these findings, we focus our attention to general self-efficacy when it comes to organizational change (Vakola et al., Citation2013), building upon the previously established argument concerned with adult attachment formation and different attachment styles forming different adult attachment fits.

General self-efficacy (abbreviated GSE) represents the belief in one's ability to utilize mental resources, drive and necessary actions to tackle new requirements within a particular context (Wood & Bandura, Citation1989). Change recipients with lower perceived levels of self-efficacy are more likely to experience stress and anxiety when encountering new experiences, and vice-versa (Bandura, Citation1989). This suggests that change recipients with lower self-efficacy are going to inevitably endure more stress during change, and therefore require more attention from the change leader in terms of comfort. Depending on individual actors’ attachment style fit, this relationship results in stronger or weaker attachment formation due to perceived psychological need satisfaction, forming different attachment style fits. Rather than centering on psychological capital, our ambition is to add to the current knowledge base by presenting innovative concepts regarding the dyadic interplay of change leaders and recipients. Therefore, our focus is on the sensegiving process delivered by change leaders, conditionally received by change recipients depending on their perception of threats and benefits from the change, which is affected by the strength of attachment between the actors. While we acknowledge the importance of general self-efficacy, we perceive at an interesting covariate in our conceptual model and observe PNS as an alternative antecedent of change recipients’ RTC.

To reinforce our case for prosocial change leadership regarding PNS as a mediating mechanism in the association between CB and RTC, we turn to practitioner insights on effective influencers. Emerging research on social media influencers emphasizes the importance of attachment formation when asserting influence (Thomson, Citation2006), as these human brands increase their influence by encouraging stronger attachment formation through enhancement of psychological need satisfaction (La Guardia et al., Citation2000). Social media influencers who support novel ideas and are perceived as human brands, effectively embodying proposed novelty (Thomson, Citation2006), and foster attachment formation by addressing followers’ comfort- and approval-seeking mechanism. Social media influencers actively affect purchasing decisions and more importantly, their audiences’ social identity formation (Reicher, Citation2004). These human brands influence audiences by leveraging relationship idealization (Thomson, Citation2006), which relies on strong attachment between the influencer and the target audience. This emerging research focusing on social media influencers’ mechanism of influence, can be operationalized through perception of adult attachment and strongly suggests introducing PNS as the model’s mediator. It enables approximation of the level of idealization between actors, but also develops the archetype of knowledge transfer in ambiguous contextual settings. More precisely, it connects the relationship between change leaders as attachment figures and change recipients, similar to the relationship between teachers and students, mentors and mentees, coaches and athletes and parents and children.

We thus hypothesize that change leaders’ CB will contribute to supporting change recipients’ behavioural autonomy. Change leaders’ CB would also help the change leader ensure change recipients have the chance to display their competence while remaining responsive and supportive in alleviating negative emotions related to organizational change. These benefits would, in turn, result in change recipients’ stronger attachment to change leaders as attachment figures, thus enhancing change recipients’ susceptibleness to change leaders’ influence. This dynamic would result in change recipients’ RTC as we stated in Hypothesis 3:

Hypothesis 3. The relationship between change leaders’ demonstration of CB and change recipients’ RTC during organizational change is partially mediated by change recipients’ PNS.

The Moderating Effects of Change Leader’s Utilization of Leadership Influence Tactics (LITs) and Narrative Intelligence (NI)

Innovation creates change on a dyadic level. Change processes inevitably bring interdependency into organizations, and numerous interpretations of newly formed circumstances further drive ambiguity and equivocality (Luscher et al., Citation2006). Put differently, the ever-changing business landscape exerts constant pressure on organizations to adjust, resulting in added intricacy, reduced transparency, and heightened likelihood of unsuccessful organizational change. The adoption of novelty thus relies on faces that contribute to making novelty more familiar and tangible (Mawson, Citation2005), consequently both the change leader and change recipients are impacted. We recognize that such a viewpoint may include certain elements of Schumpeterian theory (e.g. Gilbert, Citation2006) and potentially some hegemonic ambiguity of big concepts as mentioned by Alvesson and Blom (Citation2022). Considering their suggestions to alleviate this effect underlying our sensegiving perspective of change leadership, we turn to self-criticality and turn our attention to potentially negative utilization of NI and LITs. More specifically, we address disadvantages of unpacked concepts, how they are generally applied and how they are used in this study. Leading change is sensegiving (Sparr, Citation2018), a process of influencing contextual interpretations of change recipients during the sensemaking process (Luscher et al., Citation2006). The previously mentioned theoretical connection highlights the significance of attachment intensity in the bond between the leaders and recipients of change. We enrich it with additional theoretical perspectives suggesting change leader’s utilization of NI and LITs as moderators in the conceptual model affecting change recipients’ RTC.

As individuals perceive threats and benefits from organizational change differently, they socially identify with either the pro-change group or the change-resistant group (Battilana & Casciaro, Citation2012; Devine, Citation2015). This political aspect of organizational change is particularly interesting when observing persuasive communication, especially change leaders’ perceived political affiliation and power of influence may be influenced by their ideological identification (Scammell, Citation2015). Typically, LITs are employed to try to persuade targets to follow undetermined appeals, perform assignments, offer aid or assistance, or execute suggested modifications (Yukl & Tracey, Citation1992). Unlike CB, a change leader may utilize LITs to alter the perceived narrative and enhance the impression of demonstrating strong CB, without actually investing effort in it. We argue that change leader oriented towards pro-social behaviour refrains from utilizing negative or destructive influence tactics, including coercion, lying and blackmail, among others. Instead, we suggest that a change leader can enhance how CB is perceived by applying LITs like rational persuasion, inspirational plea, apprising, ingratiation, and consultation (Yukl et al., Citation2008). As a result of this enhancement, change recipients will perceive a relatively high level of PNS, which results in a high level of change recipients’ RTC as stated in Hypothesis 4:

Hypothesis 4. The relationship between change leaders’ demonstration of CB and change recipients’ PNS during organizational change is enhanced by change leaders’ utilization of LITs.

Stories are emotionally engaging. Communication drive connections, and connections drive results (Van Vuuren & Elving, Citation2008); however, underutilization of connections may cause emotional fatigue. Emotions are crucial in initiating, shaping, and accomplishing the process of making sense of change (Maitlis et al., Citation2013), and the use of language in creating compelling narratives allows the creation of organizational realities that will be subjected to interpretation (Chreim, Citation2002). Change leaders’ NI reflects the utilization of employment, characterization, narration, generation and thematization in communication of key messages (Pishghadam et al., Citation2011), suggesting key elements of compelling narratives. Interestingly, a change leader’s compelling narratives can engage change recipients through the mechanism of narrative transportation. Individuals experiencing narrative transportation are completely immersed in the narrative and vividly visualize what characters in the story are experiencing (Green & Brock, Citation2000). This emotionally engaging mechanism makes the story more persuasive through dual-hemisphere information processing (e.g. Taggart & Robey, Citation1981) and may help alleviate anxiety and negative emotions, as demonstrated by the use of bibliotherapy (Betzalel & Shechtman, Citation2010).

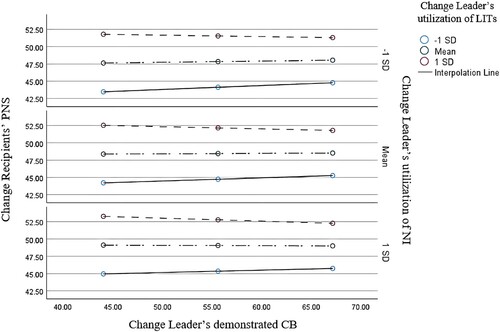

Change leaders with higher narrative intelligence (NI) scores are more likely to create a persuasive narrative about the changing environment and the change recipients during organizational change. Change leaders’ emotionally engaging stories combined with the optimally utilized LITs, should therefore enhance the sensegiving process by enhancing the effect of PNS on change recipients’ RTC. In this context, change leaders’ influencing efforts could be perceived as the act of clarifying change dynamics and emphasizing the benefits arising from such activities. Perceiving benefits from change instead of its threats encourages change recipients to socially identify with the pro-change group, thus alleviating behavioural uncertainties that arise from intensive ambiguity of organizational change. Such dynamics influence how a certain change is perceived, and ongoing organizational polarity towards such a change process heavily influences this perception (De Keyser et al., Citation2021). Metaphorically speaking, LIT could therefore represent an infrastructure for the key message being delivered, and, in this metaphor, a narrative represents the emotionally engaging vehicle. We therefore hypothesize that change leaders enhance how change recipients perceive CB and PNS by utilizing NI, as stated in Hypothesis 5 ().

Hypothesis 5. The relationship between change leaders’ demonstration of CB and change recipients’ PNS during organizational change is enhanced by change leaders’ utilization of NI.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

This study was conducted with change implementation teams that were actively working on implementing change projects that influenced their working environments. The majority of these projects were technically intensive (e.g. implementation of a new software that changed a certain process), whereas others were not (e.g. new HR processes). Our focus was on the dyadic relationship between change leaders and change recipients exposed to change leadership behaviour. An average of five change recipients assessed each change leader during an observed organizational change project. We have reached out to over 100 change leaders with a proven track record of successfully implementing transformation projects in large corporations as well as progressive tech SMEs. Despite their initial interest, the final international research sample of the study included a total of 37 change leaders from 17 organizations across 12 industries. Each change leader was leading an individual change project during our data collection. Nine change projects were nondigital (e.g. new HR processes, cultural integration after a merger), and we received a total of 164 responses from change recipients. The COVID-19 pandemic partially restricted our data collection process, which began in 2020 during its peak period, and continued until November 2021, affecting our reach and response rates.

The group of individuals who underwent organizational change consisted of team managers and implementation key team members, who worked closely with executive directors and senior middle managers serving as change leaders. Their work principally involved technical competence and interpersonal abilities. During this study, they were working from home due to mandatory lockdowns across the world, and we assume that individual and cultural differences were mitigated through their seniority and multinational organizational culture influences. A relative simplification of such unprecedented complexities, opened up some space for generalization and drove us to conclusions. The surveyed change recipients were predominantly females (55%), with an average tenure of 7 years within the company. Their average age was 37 years, and they were predominantly operational level managers.

Selected change recipients completed online surveys using Qualtrics, and we split the cross-sectional data collection into three waves. First, respondents assessed their change leaders’ CB and their own self-efficacy when the change leaders behaved in certain ways. Second, about a week later, respondents assessed their change leaders’ influence tactics and their own PNS when the change leaders behaved in certain ways. Finally, about 2 weeks later, respondents assessed their change leaders’ NI and their personal RTC when the change leaders behaved in certain ways. We also acknowledge the hierarchical nature of this dataset, as change recipients’ perceptions are nested within change leaders in different organizations. Unfortunately, following methodological guidelines suggested by Kozlowski and Klein (Citation2000) this sample size was not sufficient for multilevel analysis due to aforementioned restrictions.

Measures

The measures in this study consisted of survey questionnaires, filled out by change recipients, assessing change leaders’ actions and the recipients’ personal responses distributed via online data collection platform Qualtrics. Considering the common method variance risk, we applied suggested prevention methods (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) such as the following: clarifying the study’s purpose, splitting data collection waves into three different time points, linking personal affect with subject-matter behaviour, ensuring respondent anonymity and using different endpoint scales. We turned to Harman's factor analysis in order to test for common method variance and assess its impact on our dataset.

Independent Variable: Change Leaders’ Demonstrated Champion Behaviour (CB)

Change recipients completed the CB measure created by Howell et al. (Citation2005; α = .84), which asked respondents to rate their perception of change leaders’ behaviour on the observed change project. This measure contained 15 items covering three distinct dimensions of CB in advocating innovation. The participants were requested to evaluate their perception using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example item: ‘My change leader shows optimism about the success of the proposed change.’

Change Leaders’ Utilization of Leadership Influence Tactics (LITs)

The second measure of change leaders’ behaviour covered respondents’ perceptions of utilized leadership tactics and was developed by Yukl et al. (Citation2008; α = .80). This measure contained 20 items covering pro-social influence tactics. LITs such as coercion, exchange, coalition, legitimating and pressure were excluded. Respondents were asked to rate their perceptions from 1 (I can’t remember him/her ever using this tactic with me) to 5 (He/she uses this tactic very often with me). Following is an example item: ‘My change leader talks about ideals and values when proposing a new activity or change.’

Change Leaders’ Utilization of Narrative Intelligence (NI)

The final measure of change leaders’ behaviour was focused on respondents’ perceptions of change leaders’ applied NI and was developed by Pishghadam et al. (Citation2011; α = .75). It contained 20 items covering different dimensions of compelling narratives, such as characterization and generation. Participants were requested to assess their perceptions of change leaders using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The following is an exemplar item from the questionnaire: ‘My change leader is good at using rhetoric moves to sustain the interest of stakeholders (e.g. mentions a detail and elaborates on it gradually by revealing pieces of information bit-by-bit).’

Change Recipients’ Psychological Need Satisfaction (PNS)

Change recipients were also asked to assess their personal perceptions of their satisfaction with team interaction regarding autonomy, competence and relatedness. La Guardia et al. (Citation2000; α = .77) developed this questionnaire, which contained nine items that covered respective PNS through the lens of self-determination to participate in a relationship as initially suggested by Deci and Ryan (Citation2000). Respondents were instructed to evaluate their individual perceptions varying from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), on items such as the following: ‘I have a say in what happens and can voice my opinion.’

Dependent Variable: Change Recipient’s Individual Readiness to Organizational Change (RTC)

The change recipients assessed their individual readiness to embrace change using a measure developed by Vakola et al. (Citation2013; α = .74). This six-item measure allowed individuals to express how ready they felt to embrace change, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The following is an exemplar item from the questionnaire: ‘When changes occur in my company, I believe that I am ready to cope with them.’

Control Variables

As suggested by Bernerth and Aguinis (Citation2016), our conceptual model was controlled using a theoretical variable. Acknowledging previous research covering antecedents of organizational change acceptance (Soumyaja et al., Citation2015) and stated overarching theoretical approach, we asked respondents to assess their general self-efficacy with a questionnaire developed by Chen et al. (Citation2001; α = .86). Their questionnaire covered different dimensions closely relating to self-esteem, locus of control and neuroticism. Respondents reported their impressions varying from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), on items such as the following: ‘When facing difficult tasks, I am certain that I will accomplish them.’

Demographic Variables

Moreover, we opted to examine whether demographic factors, such as sex, age, length of service, and hierarchical level within the enterprise, had a substantial impact on our response variable. None of these variables showed statistical significance, confirming that demographic variables do not affect change recipients’ readiness to adopt change in organizations (Kunze et al., Citation2013).

Analysis

Although this research design has initially been designed as a multilevel study, relatively low response rates and external deadlines have imposed several limitations to conduct such analyses. Collected sample size is relatively small compared to suggestions from Kozlowski and Klein (Citation2000), limiting space to test for basic assumption of independence of the data points in nested samples. However, in an effort to provide some estimates of how much the recipients of each change leader agree in their evaluations, we ran an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis on the dataset using SPSS Version 26. To enhance the methodological rigour and verify factor structure through multilevel analyses, we applied a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for applied multidimensional constructs. Furthermore, to account for any potential methodological limitations during data collection, we utilized the common latent factor (CLF) test to test for common method variance (CMV) in our dataset. Aforementioned analyses were carried out by using AMOS version 28.

Acknowledging stated limitations of the optimal multilevel analysis, we opted for an alternative analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro in SPSS Version 26, specifically testing the moderated mediation Model 9 (Hayes, Citation2017). To test our hypothesized model, we decided to utilize hierarchical multiple regression to identify direct and indirect effects. Prior to more advanced statistical analysis, we focused on ensuring that collected quantitative data meets standard requirements, including distribution normality, multicollinearity and overall statistically significant relationships between measured constructs. Hayes’ PROCESS model testing separately established the relationship between change leaders’ CB as the predictor in the model and change recipients’ RTC as the dependent variable. Next, we added change recipients’ PNS into the model as the mediator that should reduce the effect of the primary relationship as evidence of partial moderation. Next, we established the relationship of change leaders’ utilization of LITs to change leaders’ demonstrated CB and change recipients’ PNS. Finally, the first phase of the testing was to establish the effect of the second moderator NI, on the relationship between CB and PNS.

The second phase of moderated mediation testing in PROCESS included testing how the presence of change leaders’ utilization of LITs and NI as moderators enhanced or antagonized the previously established moderation effect of change recipients’ PNS. A confidence interval of 95% was ensured by utilizing the bootstrap method with a random sample of 5,000 observations taken from the original sample, using three values of observed moderators (−1 standard deviation [SD], mean and +1 SD). Finally, we visualized and interpreted the conditional indirect effect and concluded our hypotheses testing.

Results

Although our sample of 164 respondents accounted for only around 66% of the initially contacted convenient sample, data screening tests confirmed that collected quantitative data met the necessary assumptions for statistical analysis. We coded missing data using the series mean method, and administered three methods of outlier identification: Mahalanobis distance, Cook’s distance and Leverage observations. These methods resulted in the removal of a total of five cases from the dataset. With preliminary descriptive statistics and variable distribution results confirming that the dataset is suitable for further analysis, we moved towards calculating intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). Merlo et al. (Citation2006) propose that ICC values less than 0.5 signify inadequate reliability and the viability of conducting a multilevel analysis is uncertain. Correspondingly, values between 0.5 and 0.75 suggest cautious reliability, while values within the range of 0.75 and 0.9 signify good reliability, and values exceeding 0.90 signify outstanding reliability (Merlo et al., Citation2006). Interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) overview for all utilized scales and measured constructs is displayed in .

Table 1. Interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) overview.

The values of ICC displayed in suggest mediocre goodness of fit according to Merlo et al. (Citation2006). Most ICC values in the study are well over 0.75, suggesting relatively good data suitability for multilevel analysis. The dependent variable RTC indicates moderate data suitability, because the ICC (.685) is above 0.5 and under 0.75, while the mediator variable PNS indicates relatively good data suitability with ICC (.795) just over the threshold of 0.75. The only exception is CB as the predictor variable, which does not indicate data suitability for multilevel analysis, because the ICC (.122) is near 0 and under 0.5. We performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to ascertain the most suitable methodological approach for further data analysis. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), sample size (n = 164) was suitable, as case numbers ranging from 100 to 400 are considered as appropriate for factor analysis. All the scales were exposed to principal component analysis while using SPSS 26. The inclusion criteria for items was above .30 (Hair et al., Citation2010).

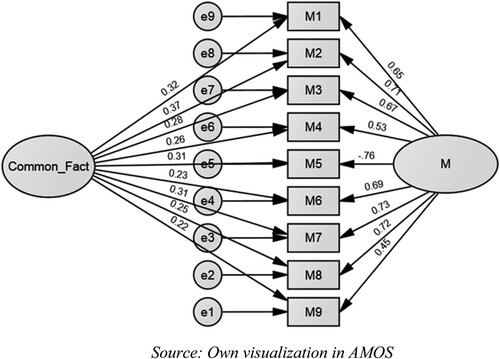

Simultaneously, we tested for common method variance to see if it had an effect on the dataset. The common latent variable approach adds an unobserved factor that connects all observed variables, with their correlations fixed to be equal and the factor's variance normalized to 1. This approach is akin to the Harman's single-factor method, linking applied observable variables to a single factor, but in this analysis, the latent variables and their associations remain retained. The common factor's variance is estimated as the sum of each path's squared common factor prior to standardization, and the threshold is typically set to 50% as a common heuristic (Eichhorn, Citation2014). We adopted the guidelines presented by Lowry and Gaskin (Citation2014) in evaluating the effect of CLF on our research model. This involved computing the divergence between the standardized regression weights of the constrained and unconstrained models, and retaining the CLF construct if the difference exceeded 0.2. Additionally, we estimated the effect of CLF by subtracting the estimate without CLF from the estimate with CLF.

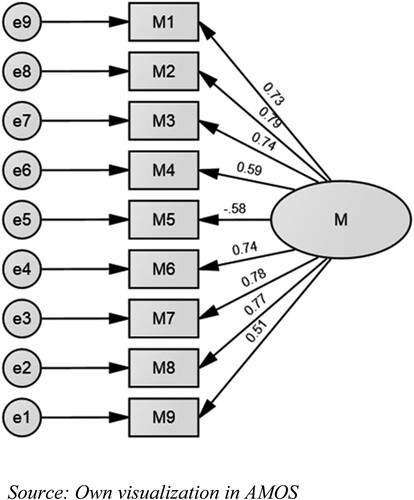

Example procedure for CFA and CMV analyses for the mediator PNS is displayed below. We also performed the confirmatory factor analysis in order to verify the factor architecture of the PNS measure, a three-dimensional construct. Items were loaded on its particular compound factor in the model. The item loading ranged from .50 to .77. As displayed in , applied questionnaire items significantly loaded respective factors.

Chi-square goodness of fit test, which is known as the central measure of model fit in SEM analysis (Lowry & Gaskin, Citation2014), was found to be statistically significant (χ2 = 75.63; df = 27). The absolute fit measures including CMIN/Df and RMSEA index values were as follows: CMIN/Df = 2.80 (recommended < 5) and RMSEA = .11 (recommended < .10). Furthermore, as portrayed in , incremental fit measures including IFI, CFI and TLI were as follows: IFI = .92 (Recommended > .90); CFI = .92 (Recommended > .90) and TLI = .86 (Recommended > .90).

Table 2. CFA Model for psychological need satisfaction (M).

Nine-item compound variable showed almost good fit indices and acceptable construct validity as indicated in the results displayed in , progressing our analysis towards common method variance. After juxtaposing the standardized regression weights from the constrained and unconstrained models using the common latent factor method, the difference on all items of the scale was not greater than 0.2 ().

The data presented in indicate the absence of common method bias in the scale. Surprisingly, Harman's single factor technique indicated the existence of common method bias in our dataset, as the total variance expunged by one factor exceeds the suggested 50% threshold and is at 54%. We have therefore decided to continue our analysis with common latent factor method, as the less disputed and methodologically more robust approach.

Table 3. Standardized regression weights for Psychological Need Satisfaction (PNS) Scale.

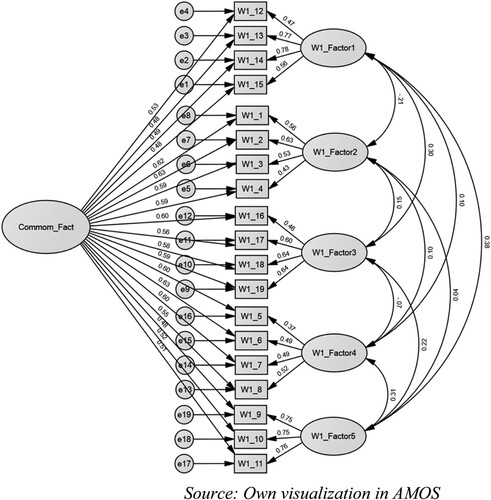

The same procedure was repeated for remaining variables in the model: CB, LITs, NI, RTC and GSE. Findings indicated that the majority of the indices showed good fit for the scales including LITs, NI and RTC. However, the CB and GSE scales did not demonstrate satisfactory goodness of fit indices and acceptable construct validity. Findings indicated no evidence of common method bias in the PNS, GSE, and CB scales. However, some items in the LIT, NI, and RTC scales demonstrated the presence of common method bias. Hypothesized moderator analysis for the variable LITs is presented below.

Although Harman's single factor test did not suggest a common method bias present in the data (i.e. 44.95% is less than the recommended threshold of 50%), the common latent factor method yielded different results. Specifically, when comparing the standardized regression weight from the constraint and unconstraint models, there was a significant difference observed in one item of factor 1 (W1_12), and all items of factor 2, factor 3 and factor 4 were larger than 0.2, as displayed in .

This implies that the scale is affected by common method bias, which hinders the effects of interconstruct relationships. Additionally, results indicated that the correlation between latent factors decreased, as presented in .

Table 4. Standardized regression weights for Leadership Influence Tactics (LITs) Scale.

Altogether, presented evidence indicate potential problems in further interconstruct data analysis, therefore we have opted out of multilevel analyses and decided to continue with an alternative single-level moderated mediation analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro in SPSS. displays variable correlations, confirming that there were no highly correlated variables that would jeopardize the multicollinearity assumption. Change leaders’ demonstration of CB appears to be the only variable with a fairly weak and negative correlation with individual RTC.

Table 5. Observed variable correlation factors.

Our PROCESS macro analysis, conducted in SPSS, unveiled several interesting conclusions. The mediator PNS was specified as the outcome variable in Model 1. The Fisher statistics (F = 14.80) and associated probability value (p < .01) of Model 1 demonstrated that overall model was statistically significant, and the variables in Model 1 together explain 31% of variance (R2 = .31). Only change leaders’ utilization of LITs significantly predicted change recipients’ PNS (B = .23; p < .001), whereas NI and GSE were insignificant.

In the second model, the outcome variable was change recipient’s RTC. The Fisher statistics (F = 3.90) and associated probability value (p < .05) in Model 2 demonstrated that overall model was significant, and the variables in the second model together explain 4% of variance (R2 = .04). In the second model, change recipients’ RTC was significantly predicted by PNS (B = .12; p < .01), which reduced the variance compared to the first model. These findings support Hypotheses 1-3, indicating that PNS of change recipients partially mediates the relation among CB demonstrated by change leaders and RTC of change recipients during organizational change. Based on the results displayed in , hypotheses 4 and 5 are refuted, suggesting that neither LITs nor NI moderate the mediation process of PNS.

Hypothesized moderating effect is non-existent because all three ranges (i.e. +1 SD, mean and −1 SD) have zero value within their respective bootstrap confidence intervals. Additionally, the introduction of demographic control variables and our covariate variable of GSE was statistically insignificant and decreased overall effects. Interestingly, compared with change leaders’ demonstrated CB, utilization of LITs and NI reported a relatively stronger relationship with change recipients’ PNS. This led us to introduce a complementary model with NI as the moderator and LITs and CB as predictors. We also tested Hayes’ PROCESS Model 7 with the established variable configuration, which returned similar results. The juxtaposition of the given variables conceptualized as predictors provided complementary evidence of change leaders’ demonstration of CB being a fairly ineffective predictor of change recipients’ RTC (R2 = −0.0017) compared to LITs (R2 = 0.0962).

Discussion

Conducted analyses suggest several important findings. First, sample size is relatively unsufficient for multilevel analysis and collected data shows partial reliability for multilevel analysis of interconstruct relationships, ranging from complete unreability to excellent reliability. The fit indices and construct validity of the predictor variable CB and the covariate GSE did not meet the required criteria for acceptability. Finally, some of the items in the scales including LITs, NI and RTC indicated the presence of common method bias. Altogether, these results indicate potential problems in further interconstruct data analysis, therefore we have opted out of multilevel analyses and decided to continue with an alternative single-level moderated mediation analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro in SPSS.

Conducted exploratory analysis of change leaders’ sensegiving efforts resulted in interesting findings, some of which were less expected than others. Hypotheses 1–3 were confirmed, suggesting that change leaders’ demonstration of CB positively affects change recipients’ perception of PNS, and that change recipients who perceive relatively higher PNS feel more RTC. The relation among change leaders and change recipients is partially mediated by PNS, indicating that when change recipients feel a higher level of satisfaction in their autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs, they tend to develop stronger attachment to their change leaders, resulting in an increased level of RTC.

This primary relationship within our mediated moderation model does not surprise, since the naturally present desire for autonomy implies the necessity to demonstrate competence and justify approved autonomy from the change leader, which in turn encourages a sense of relatedness in a high-quality relationship. When change leaders lead by example by demonstration of CB, they exert energy into demonstration of enthusiasm, persistence under uncertainty and overall inclusion of key people necessary for the success of the project. Change recipients respond to this sensation of ‘being in the same boat’ and respond with higher RTC. On the other hand, hypotheses 4 and 5 were not confirmed, respectively indicating that a change leader’s utilization of LITs and NI does not moderate the primary relationship. In other words, change leaders’ utilization of LITs and NI did not significantly affect the primary relationship between a change leader’s demonstrated CB and change recipients’ perception of PNS. Additionally, theoretical and demographic controls previously highlighted were also found to be insignificant and did not affect the primary or secondary relationship. We ran additional analyses in an effort to mitigate sample restrictions, and these results were continuously confirmed despite being the opposite of our theorizing. However, additional results yielded unexpected results worth noting.

More specifically, change leaders’ utilization of LITs proved to be a stronger predictor of change recipients’ RTC with change recipients’ PNS partially mediating the relationship. In other words, change leaders’ utilization of LITs altered change recipients’ perception of autonomy, competence and relatedness need during organizational change and resulted in stronger RTC, than in the case where change leaders demonstrated CB. Most utilized LITs in observed sample were rational persuasion (average score of 3.987 out of 5) and consulting (average score of 3.972 out of 5), which is particularly interesting since our sample change leaders were formally educated and experienced in change leadership, and highlighted the importance of understanding the emotional aspect of organizational change.

This finding challenges the dominant theoretical perspective of the role of CB when it comes to implementing innovation. Another interesting finding of these additional analyses was related to the utilization of NI. Change leaders’ utilization of NI was most affecting change recipients’ perception of PNS and RTC when utilized without additional utilization of LITs, with an average score of 3.991 out of 5. In other words, change leaders who were creating narratives were most effective when stories were being told without the utilization of predominantly rational LITs. This is partially in line with our initially theorized relationship, suggesting that stories should be told in an emotionally engaging manner instead of simultaneously being tactical. Concluding this discussion and acknowledging the self-critical remedy for hegemony, ambiguity and scope limitations suggested by Alvesson and Blom (Citation2022), we consider the case of the ideally persuasive change leader who utilizes previously presented mechanism of influence outside the acceptable zone of change recipients’ discomfort and hinders their wellbeing. Change leaders with high scores in subclinical psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism personality traits, known as the dark triad (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2014), may exhibit a strong drive to win at all costs, even if it comes at the expense of others (Paleczek et al., Citation2018). Outside of obvious charismatic traits that enhance the persuasiveness of their communication, narcissistic personalities are particularly interesting in terms of adult attachment, as covert and overt narcissistic personalities tend to be idealized and progress their careers relatively faster than compared to individuals with lower scores (Rovelli & Curnis, Citation2021).

Additionally, leaders with relatively high scores on overt narcissism scales demonstrate relatively stable elements of secure attachment (Smolewska & Dion, Citation2005). They tend to exert stronger influence on followers through various self-enhancing mechanisms and become more desirable in positions of power and influence (Mayseless, Citation2010), partially addressed through change leaders’ LITs utilization in this study of organizational change. One example of organizational change where over utilized desirable behaviours lead to undesired outcomes, is the case of Enron (Tourish & Vatcha, Citation2005), widely recognized as a capital case of corporate cultism and destructive behaviour to employees, camouflaged as a high-performing organizational culture.

Theoretical Implications

Our aim was to expand the body of knowledge on change leaders’ sensegiving during organizational change, which has primarily focused on the change recipients’ sensemaking process. This paper contributes to existing literature in several ways. Firstly, we build on Battilana and Casciaro's (Citation2013) perspectives on change leaders’ influential efforts, by incorporating adult attachment theory. Our study confirms that change recipients’ PNS fractionally mediates the relation among change leaders’ CB and change recipients’ RTC, highlighting how important it is to satisfy the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness during the sensegiving process to strengthen attachment. Here we highlight change recipients’ PNS as an important predictor of how susceptible change recipients will be to change leader’s influence. We also highlight the importance of change leaders’ NI perceived by change recipients in terms of conveying influential ideological messages, but without combining it with previously studied LITs. Second, we extend the sensegiving conceptual model suggested by Sparr (Citation2018) with affective perspectives, highlighting the importance of change leaders’ utilization of LITs and NI when addressing change recipients’ perception of threats and benefits stemming from proposed change. Change leaders as attachment figures invest effort in meeting change recipients’ psychological needs (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000), thus building attachment and creating a functional change leader–change recipient dyadic relationship. Ultimately, our findings contest conventional beliefs in the realm of innovation management by demonstrating that the employment of LITs by change leaders has a more substantial impact on change recipients’ PNS and RTC than the display of CB, as previously suggested in literature such as Rosenbusch et al. (Citation2011).

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Our study offers interesting findings, suggesting future research directions and thus contributing to the field’s broad body of knowledge. However, there are certain limitations to consider, as is the case with other empirical studies. First, our sample size was not sufficient for multilevel data analysis which could offer more relevant findings from the hierarchical nature of our data. This study essentially explored how change recipients who are participating in ongoing organizational change project perceive their change leaders’ behaviour, limiting our conclusions to a single-level perspective. Such an approach was a practical compromise during stressful COVID-19 pandemic times, which limited our access to respondents and participation rates. Future research could potentially investigate a multilevel perspective, also accounting for change leaders’ perspectives. Additionally, adult attachment styles could be further investigated to increase our understanding of how change leaders’ and change recipients’ varying attachment styles affect organizational change adoption.

Second, we acknowledge that our hypothesized moderated mediation model was unconfirmed and that interconstruct relationships were weaker than expected. Although our theoretical foundation suggested that a specific moderated mediation model was the best explanation of persuasion’s underlying mechanism, there are numerous other Hayes’ PROCESS models to explore in the future. A separate examination of specific LITs and specific dimensions of NI could unveil novel insights in understanding how change recipients embrace change adoption.

Finally, we focused on a specific literature direction in terms of understanding the underlying mechanism of persuasive communication. Although we have opted for a bit of interdisciplinary literature approaches, there are numerous possible venues for building the theoretical foundation observing the sensegiving process and investigating alternative mechanisms of change leaders’ influence exertion to change recipients. One of many examples could be exploring power dynamics or overall perceptions of organizational politics and how such destructive behaviour affects the organizational climate, thus influencing change recipients’ psychological capital. Similarly, aforementioned dark triad personality traits in change leaders and change recipients could shed some additional light on how organizational change unfolds in highly competitive organizations thriving on achieving results at a high standard.

Practical Implications and Conclusion

In more practical terms, change leaders working on organizational change projects should utilize NI when setting the stage for their key messages. Change recipients self-reported and rated their perception of change leaders’ behaviour during organizational change. Research findings partially confirm my hypotheses, confirming that perceived PNS partially moderates the relationship between CB and RTC. Hypothesized moderated mediation model was not confirmed, as change leaders’ utilization of LITs and NI did not moderate the aforementioned primary relationship. The additional analysis highlighted some unexpected results, suggesting that change leader’s utilization LITs predicts the primary relationship stronger than change leader’s demonstration of CB. Similarly, the additional analysis suggested that change leaders’ utilization of NI affects the primary relationship with a stronger effect when utilized without LITs. Quantitative analysis suggested that change leaders should utilize NI separately to create an emotional foundation with change recipients, and influence the emotional aspect of dual-hemisphere information processing. Similarly, change leaders would utilize LITs to ensure that the rational aspect of dual-hemisphere information processing is accounted for, effectively adjusting the message to meet the needs of respective change recipients. Achieving dual-hemisphere information processing ensures that their message is internalized and enhances the sensemaking process in change recipients, thus enhancing individual readiness to change.

Considering the emotionally intensive nature of organizational change, findings suggest that change leaders who are mindful of change recipients’ PNS exert more influence over their readiness to change. Stories seem to be particularly persuasive in relaying emotionally intensive content and change leaders with relatively higher scores in NI implied the need for autonomy and competence in their anecdotes. Unlike CB which is more energy demanding, utilization of LIT and NI does a better job at energy preservation while maintaining the positive effect between change recipients’ PNS and RTC. This suggests that change leaders should revert to these behaviours instead of depleting their energy through leadership by example, while being mindful of emotional dynamics that change recipients experience during transformation processes in organizations.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgments

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId = do:10.7910/DVN/GRQA3S.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antonio Sadarić

Antonio Sadarić is a research fellow at the School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana in Slovenia. He received his Ph.D. from University of Ljubljana. His current research interests cover change leadership, narrative intelligence, creativity and innovation management, corporate culture and corporate cultism.

Miha Škerlavaj

Miha Škerlavaj is a professor of management and vice-dean for research and doctoral studies at the School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana in Slovenia. He is also an adjunct professor of organizational behaviour at BI Norwegian Business School in Oslo, Norway. He received his Ph.D. from University of Ljubljana. His current research is focused on organizational culture, change, creativity, innovation and knowledge hiding.

References

- Aldama, F. L. (2015). The science of storytelling: Perspectives from cognitive science, neuroscience, and the humanities. Berghahn Journals.

- Alvesson, M., & Blom, M. (2022). The hegemonic ambiguity of big concepts in organization studies. Human Relations, 75(1), 58–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726720986847

- Appelbaum, S. H., Habashy, S., Malo, J. L., & Shafiq, H. (2012). Back to the future: Revisiting Kotter's 1996 change model. Journal of Management Development, 31(8), 764–782. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711211253231

- Baer, M. (2012). Putting creativity to work: The implementation of creative ideas in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1102–1119. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0470

- Balogun, J., & Johnson, G. (2005). From intended strategies to unintended outcomes: The impact of change recipient sensemaking. Organization Studies, 26(11), 1573–1601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605054624

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

- Battilana, J., & Casciaro, T. (2012). Change agents, networks, and institutions: A contingency theory of organizational change. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0891

- Battilana, J., & Casciaro, T. (2013). Overcoming resistance to organizational change: Strong ties and affective cooptation. Management Science, 59(4), 819–836. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1583

- Battilana, J., & Casciaro, T. (2021). Power, for all: How it really works and why it's everyone's business. Simon and Schuster.

- Battilana, J., Gilmartin, M., Sengul, M., Pache, A.-C., & Alexander, J. A. (2010). Leadership competencies for implementing planned organizational change. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(3), 422–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.007

- Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2016). A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103

- Betzalel, N., & Shechtman, Z. (2010). Bibliotherapy treatment for children with adjustment difficulties: A comparison of affective and cognitive bibliotherapy. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 5(4), 426–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2010.527816

- Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/448619

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

- Chreim, S. (2002). Influencing organizational identification during major change: A communication-based perspective. Human Relations, 55(9), 1117–1137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726702055009022

- Coan, J. A. (2008). Toward a neuroscience of attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. (pp. 241–265). The Guilford Press.

- Davidovitz, R., Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., Izsak, R., & Popper, M. (2007). Leaders as attachment figures: Leaders’ attachment orientations predict leadership-related mental representations and followers’ performance and mental health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(4), 632–650. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.632

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1995). Human autonomy. In M. H. Kernis (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem (pp. 31–49). Springer.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- De Keyser, B., Guiette, A., & Vandenbempt, K. (2021). On the dynamics of failure in organizational change: A dialectical perspective. Human Relations, 74(2), 234–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719884115

- Devine, C. J. (2015). Ideological social identity: Psychological attachment to ideological in-groups as a political phenomenon and a behavioral influence. Political Behavior, 37(3), 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9280-6

- Eichhorn, B. R. (2014). Common method variance techniques (pp. 1–11). Cleveland State University, Department of Operations & Supply Chain Management, SAS Institute Inc.

- Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W., & D'Amelio, A. (2008). Resistance to change: The rest of the story. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.31193235

- Fransen, K., Haslam, S. A., Steffens, N. K., Vanbeselaere, N., De Cuyper, B., & Boen, F. (2015). Believing in “us”: Exploring leaders’ capacity to enhance team confidence and performance by building a sense of shared social identity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 21(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000033

- Furst, S. A., & Cable, D. M. (2008). Employee resistance to organizational change: Managerial influence tactics and leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.453

- Gilbert, R. (2006). Looking for Mr. Schumpeter: Where are we in the competition–innovation debate? Innovation Policy and the Economy, 6(2), 159–215. https://doi.org/10.1086/ipe.6.25056183

- Gioia, D. A., & Chittipeddi, K. (1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal, 12(6), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120604

- Gottfredson, R. K., Wright, S. L., & Heaphy, E. D. (2020). A critique of the leader-member exchange construct: Back to square one. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(6), Article 101385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101385

- Grady, V. M., & Grady IIIJ. D. (2013). The relationship of Bowlby's attachment theory to the persistent failure of organizational change initiatives. Journal of Change Management, 13(2), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2012.728534

- Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (Vol. 7). Pearson.

- Harms, P. D. (2011). Adult attachment styles in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review, 21(4), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.10.006

- Hay, G. J., Parker, S. K., & Luksyte, A. (2021). Making sense of organisational change failure: An identity lens. Human Relations, 74(2), 180–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726720906211

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Heracleous, L., & Bartunek, J. (2021). Organization change failure, deep structures and temporality: Appreciating Wonderland. Human Relations, 74(2), 208–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726720905361

- Holt, D. T., Armenakis, A. A., Feild, H. S., & Harris, S. G. (2007). Readiness for organizational change: The systematic development of a scale. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(2), 232–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886306295295

- Houran, J., Navik, S., & Zerrusen, K. (2005). Boundary functioning in celebrity worshippers. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(1), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.04.014

- Howell, J. M., & Higgins, C. A. (1990). Champions of change: Identifying, understanding, and supporting champions of technological innovations. Organizational Dynamics, 19(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(90)90047-S

- Howell, J. M., Shea, C. M., & Higgins, C. A. (2005). Champions of product innovations: Defining, developing, and validating a measure of champion behavior. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(5), 641–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.06.001

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the short dark triad (SD3) a brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191113514105

- Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Klein, K. J. (2000). A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 3–90). Jossey-Bass.

- Kunze, F., Boehm, S., & Bruch, H. (2013). Age, resistance to change, and job performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(7-8), 741–760. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2013-0194

- La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367

- Lowry, P. B., & Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2014.2312452

- Luscher, L. S., Lewis, M., & Ingram, A. (2006). The social construction of organizational change paradoxes. Management, 19(4), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810610676680

- Luthans, F., Norman, S. M., Avolio, B. J., & Avey, J. B. (2008). The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate—employee performance relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.507

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 339–366. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113324

- Maitlis, S., & Sonenshein, S. (2010). Sensemaking in crisis and change: Inspiration and insights from Weick (1988). Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 551–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00908.x

- Maitlis, S., Vogus, T. J., & Lawrence, T. B. (2013). Sensemaking and emotion in organizations. Organizational Psychology Review, 3(3), 222–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386613489062

- Mawson, A. R. (2005). Understanding mass panic and other collective responses to threat and disaster. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 68(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2005.68.2.95

- Mayseless, O. (2010). Attachment and the leader—follower relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360904

- Mento, A., Jones, R., & Dirndorfer, W. (2002). A change management process: Grounded in both theory and practice. Journal of Change Management, 3(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/714042520

- Merlo, J., Chaix, B., Ohlsson, H., Beckman, A., Johnell, K., Hjerpe, P., & Larsen, K. (2006). A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: Using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(4), 290–297. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.029454

- Oreg, S. (2003). Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 680–693. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.680

- Oreg, S. (2006). Personality, context, and resistance to organizational change. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(1), 73–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500451247

- Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(4), 461–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886310396550

- Paleczek, D., Bergner, S., & Rybnicek, R. (2018). Predicting career success: Is the dark side of personality worth considering? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(6), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2017-0402

- Pishghadam, R., Baghaei, P., Shams, M. A., & Shamsaee, S. (2011). Construction and validation of a narrative intelligence scale with the Rasch rating scale model. The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment, 8(1), 75–90.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Randall, W. L. (1999). Narrative intelligence and the novelty of our lives. Journal of Aging Studies, 13(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(99)80003-6

- Reicher, S. (2004). The context of social identity: Domination, resistance, and change. Political Psychology, 25(6), 921–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00403.x

- Rhodes, C., & Brown, A. D. (2005). Narrative, organizations and research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(3), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00112.x