ABSTRACT

In this paper, we draw on systems leadership, complexity and paradox theory to elucidate the tensions that organizational actors experience when practising multi-level leadership. We explore these issues through a study of the perceptions and experiences of stakeholders within an Integrated Care System (ICS) in England. Employing a collaborative inquiry approach, data were collected via 19 narrative interviews with participants in key leadership roles across ICS partners and nine co-creation workshops with a total of 86 participants from different parts of the ICS. Findings highlight that in developing multi-level leadership practice, leaders experience contradictory expectations and outcomes, including paradoxes of identity, place, purpose and change. We conclude by suggesting that leadership in multi-level contexts requires oscillating between competing polarities in a dynamic equilibrium with attention to localized interactions.

MAD statement

Integrated Care Systems were enacted across England in July 2022 to enhance the capacity for statutory, voluntary and community organizations to work in partnership to improve health outcomes across diverse populations. Multi-level systems leadership, however, poses significant challenges around navigating the inevitable tensions that arise when working with complexity. Through qualitative research in a vanguard ICS, this paper highlights a range of paradoxes faced by leaders and organizations and proposes implications for policy and practice in enabling dynamic equilibrium and working in contexts of uncertainty and change.

Introduction

Across public services, there is increasing recognition of the need to facilitate collaboration, partnership working and system(s) change. Responding to complex, ‘wicked’ challenges requires mobilizing diverse knowledge, expertise and resources that span multiple organizations, stakeholders, communities and other interest groups. As Bryson et al. (Citation2017, p. 641) suggest:

[The] new world [of public services is a] polycentric, multi-nodal, multi-sector, multi-level, multi-actor, multi-logic, multi-media, multi-practice place characterised by complexity, dynamism, uncertainty and ambiguity in which a wide range of actors are engaged in public value creation and do so in shifting configurations.

Despite the emphasis on leading across professional and organizational boundaries, research has failed to draw out the development of multi-level practices in these contexts. In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic – and the social, economic and environmental crises that now shape our lives – this is an increasingly urgent issue to address for leadership theory, practice and development (Uhl-Bien, Citation2021).

In this paper, we draw on systems leadership, complexity and paradox theory to elucidate the tensions that organizational actors experience when practicing multi-level leadership. We explore this through qualitative research within an Integrated Care System (ICS). ICSs were piloted from 2017 and formally mandated from July 2022 by the National Health Service (NHS) in England to encourage more effective partnership working between health and social care providers, local authorities, and community and voluntary organizations. Their purpose is to coordinate the work of general practices, statutory and voluntary community-based services and hospitals within a specific locality around the needs of the citizen in order to reduce health inequalities and improve population health. This makes ICSs an ideal context to explore multi-level systems leadership in action. Findings highlighted that in developing multi-level leadership practice, leaders experience contradictory expectations and outcomes, characterized by a tension between two or more polarities that (at face value) appear to be in opposition. These included paradoxes of identity, place, purpose and change.

We note that public policy can foreground paradoxical tensions and make them more salient to organizations. However, we find that leaders’ response to these tensions can enable (or constrain) their management teams and the achievement of purposeful and sustainable change. For complexity scholars paradoxes are a ubiquitous, though under-recognized and under-valued aspect of organizational life where rationality, planning and control tend to be emphasized and rewarded. We conclude by suggesting that multi-level leadership requires navigating competing polarities, reframing them from either/or (dualisms) to both/and (dualities) (Murphy et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2016), in dynamic equilibrium.

Theoretical Background

Recent years have seen a shift from leader-centric towards more relational perspectives that view leadership as a ‘social influence process through which emergent coordination (e.g. evolving social order) and change (e.g. new approaches, values, attitudes, practices, ideologies) are constructed and produced’ (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006, p. 668). Both theory and practice now widely recognize leadership as ‘collective’ (Ospina et al., Citation2020), ‘plural’ (Denis et al., Citation2012), ‘distributed’ (Bolden, Citation2011) or ‘shared’ (Doos & Wilhelmson, Citation2021; Sweeney et al., Citation2019). As Bryson and colleagues (Citation2017) highlight, however, whilst such work is significant in broadening our perspective beyond a small number of formal ‘leaders’ it often remains limited in terms of its capacity to illustrate or explain leadership in dynamic, cross-boundary environments.

One concept that has begun to gain traction – particularly within public service policy and practice in the UK – is ‘systems leadership’.Footnote1 Building on the notion of ‘systems thinking’ (Senge, Citation1990), this approach highlights the interconnected, relational and boundary-spanning nature of leadership practice and the need for a shift in mindset from hierarchy to system. An influential review published by the Virtual Staff College (Ghate et al., Citation2013) highlights the public service context as one characterized by increasing demand, decreasing resources, ‘wicked’Footnote2 issues, regulation and inspection, opportunity, paradox, interdependency and interconnectedness, risk and VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity). In such contexts, it is suggested that leaders need to develop their ways of feeling, perceiving, thinking, relating, doing and being to embrace, rather than succumb to, these pressures.

Senge et al. (Citation2015) highlight the role of ‘system leaders’ in fostering collective leadership to address complex challenges. Core capabilities include (1) being able ‘to see the larger system’, (2) ‘fostering reflection and more generative conversations’, and (3) ‘shifting the collective focus from reactive problem solving to co-creating the future’ (ibid, pp. 28–29). They note, however, that ‘we are at the beginning of the beginning in learning how to catalyze and guide systemic change at a scale commensurate with the scale of problems we face, and all of us see but dimly’ (p. 28).

Whilst system(s) leadership remains a relatively new and evolving concept, it has been enthusiastically adopted within public services and advocated as a means for building partnerships that will underpin the transition to integrated health and care systems in England (Smith et al., Citation2021). In policy and practice, however, whilst the need for collaboration and cooperation across groups is recognized, how this can be achieved in the face of differing and/or potentially competing priorities and agendas remains unclear (Bolden, Citation2020).

Stacey (Citation2006, p. 30) notes that ‘a particularly naive form of systems thinking has become the fundamental notion underlying public sector governance today’, whereby ‘the system’ is conceived of as distinct entity and ‘system thinkers’ are able to step outside it to take a ‘whole system’ perspective. This, he argues, is problematic as it greatly exaggerates the potential for ‘system leaders’ to exert system-wide influence and underestimates the capacity for human agency of others elsewhere within the system. Instead, he proposes a perspective that regards processes of leadership and organizing as arising through localized interactions rather than the aspirations or intentions of some higher authority.

Uhl-Bien et al. (Citation2007) propose the notion of ‘complexity leadership’ as a way to bridge the processes of operational (also referred to as administrative) leadership within formal organizational structures and localized, emergent entrepreneurial (also referred to as adaptive) leadership that transcends organizational boundaries. For this to occur, they suggest, it is necessary to use enabling leadership to open up ‘adaptive spaces’ whereby generative solutions can be developed. This requires an ability to navigate the ‘tension dynamic’ between sources of conflict and connection, in order to facilitate the emergence of new forms of ‘adaptive order’ (Uhl-Bien, Citation2021, p. 149).

A compelling example of how such insights can be applied to study leadership within complex public sector contexts is presented by Murphy et al. (Citation2017), who highlight the role of ‘enabling leadership’ in managing the dynamic tensions between adaptive and administrative processes. They identify four key tensions in systems that 'enabling leadership' may address through a dynamic balance between adaptive and administrative practices: reducing and injecting tension; sensemaking and sensebreaking; formalizing networks and enabling informal networks; and actively removing excluding or alienating dissident actors and protecting dissident voices. In doing so, they suggest that ‘a core function of leadership is to embrace leadership tensions and help shift actors beyond “either/or” toward paradoxical thinking that entails a both/and mindset that is holistic and dynamic’ (p. 701).

Paradox is defined as the experience of ‘contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time’ (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011, p. 382). Whilst latent paradoxical tensions exist in most organizations, when these become salient a natural reaction may be to seek to resolve the paradox (and with it the tension) by favouring one ‘polarity’ over the other. Individual and organizational strains, inertia, interpretive schemes, unconscious reactions and action preferences may reinforce the focus on either/or choices and fuel vicious cycles in paradox management (Knight & Paroutis, Citation2017; Nielsen et al., Citation2023; Smith & Lewis, Citation2011). Whilst placing such cognitive boundaries and brackets may help in constructing simple, logical, internally consistent bipolar concepts and making sense of complex realities (Ford & Ford, Citation1994), it hinders the potential to tap into the insights gained by accepting, confronting, and transcending paradox (Lewis, Citation2000).

According to paradox research, contradictions are both mighty and malleable. They are fixed within systems, structures and language, and as such are ‘too pervasive to be integrated or willed away’ (Clegg et al., Citation2002 p. 491). Yet they are also socially constructed and open to reframing by organizational actors (Putnam et al., Citation2016). When organizational actors encounter paradoxes, they begin to shape their interpretation and response to them, often in discussion and negotiation with others. In turn, their interpretations and responses co-construct the experience of paradoxes, setting off a dynamic interplay of paradoxes, the actions that people take and the organizational procedures that permeate structures within which these actions take place (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013).

The interdependence of polarities means that attempts to prioritize one over the other will be ineffective (Lewis, Citation2000; Poole & Van de Ven, Citation1989). This marks a key difference between management problems that call for a solution and paradoxes that cannot be resolved but need to be continuously handled by embracing multiple opposing poles simultaneously (Lewis & Smith, Citation2014). Seen in this light, the notion of ‘paradox management’ is about recognising and working with tensions rather than solving them. The literature includes examples in which researchers have designed ‘collaborative sensemaking processes’ (Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008) and ‘reflexive practice approaches’ (Huxham & Beech, Citation2003) to help practitioners move from either/or interpretations toward a paradox perspective that enables action. ‘Detecting and naming paradoxes through research has the potential to aid understanding and sensemaking’ (Vangen, Citation2017, p. 267), which points to the importance of achieving clarity in expressing paradoxes and their related tensions for practice.

Organizational paradoxes are well documented (Lewis, Citation2000; Smith & Lewis, Citation2011), as is their relevance to leadership and collaboration (e.g. Huxham & Beech, Citation2003; Ospina & Saz-Carranza, Citation2010; Vangen & Huxham, Citation2012). These, however, are key conceptual and practical challenges for multi-level leadership, and further empirical work is needed to provide ‘conceptual handles for reflection’ (Vangen, Citation2017, p. 268). Paradoxes most commonly arise in contexts of scarcity, change and plurality (Smith et al., Citation2016), making them prevalent in resource-constrained complex systems such as the health and care sector, as outlined below.

Policy Context: Integrated Care Systems

The health and care sector in England is facing a multitude of challenges, such as rising demand from an ageing population with increasingly complex health needs and long-term conditions that often require community and home-based care alongside acute provision, coupled with workforce shortages and shrinking budgets (The Lancet, Citation2021) – issues exacerbated by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on both staff (Pollitt et al., Citation2021) and services (Reed et al., Citation2022).

It is in this context that the government White Paper on Health and Social Care (DoHS, Citation2021) set out plans for the most significant changes to the organization of health and care in England in a decade. Officially enacted from 1 July 2022, the 2022 Health and Care Act formalized 42 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) across England as statutory bodies. These reforms intend to promote closer integration and collaboration between the NHS, social care, public health and the voluntary/community sector in addressing health inequalities and improving population health. The 2022 Health and Care Act involves two forms of integration: (1) integration within the NHS to make collaboration between its different constituent parts an organizing principle (including removing some regulations around procurement and competition); and (2) greater collaboration across health and care system partner organizations to improve health and wellbeing for their local populations.

Of particular note is the greater emphasis on place-based partnership and delegated budgets, with collaborative rather than competitive tendering. This greater attention to place operates at three levels and involves multi-level systems leadership across organizational and place-based boundaries: Primary Care Networks (PCNs), where General Practice (GP) and other primary care services are offered to neighborhoods (typically to populations of around 30–50k); Place-Based Partnerships (PBPs) where NHS, local government and other organizations provide services within local authority boundaries (typically to populations of 250–500k); and Integrated Care Systems (ICS), that coordinate services across a larger region (typically covering populations of 1–3 million). The underpinning principle is that decisions are taken as close as possible to local communities unless there are benefits of scale (see Charles, Citation2022 for further details).

The governance structure for the statutory ICSs includes an Integrated Care Board (ICB), an NHS body with NHS budgetary and planning responsibilities for the provision of health services in the ICS area, and ICP (Integrated Care Partnership) Boards, which bring together NHS, local government, community/voluntary organizations and other partners to support integration. Whilst they have a duty to collaborate, the local arrangements governing how these bodies are brought into practice require thoughtful multi-level systems leadership if they are to work effectively. As well as tensions in the level of place at which decisions are taken, there are potential tensions for leadership between, for example: organizational and place-based priorities and allocation of resources; differing financial and governance structures across NHS organizations and local authorities; and differences between medical models of care that focus on conditions and community-based approaches that are based around ‘cohorts’.

Bülow and Simpson (Citation2022) differentiate between purpose as a set of goals or measurable outcomes and purpose as a sense and note that an organization’s purpose ‘is typically understood as the rationale for an organizational vision and the active expression of organisational values’ (p. 69), privileging the former. Thus, whilst on paper ICS partner organizations have a clear shared purpose in addressing health inequalities and promoting the health and wellbeing of their populations, there are often tensions in how this purpose is understood and brought into practice so that ‘the leadership challenge is to hold in balance these definable with undefinable elements of purpose’ (Bülow & Simpson, Citation2022, p. xii). If overlooked, there is a risk that these tensions will reinforce pre-existing assumptions and undermine effective collaboration, for example perceiving the NHS as the dominant partner and the reform as just another NHS reorganization that will not address underlying issues. Indeed, at the time of writing, detailed proposals for social care and public health are still being developed, and the 2022 Health and Care Act touches only lightly on their role in the new ICSs.

Together, these changes are intended to address the most urgent and important issues facing the health and wellbeing of the UK population and are directly linked to the long-term sustainability of accessible and affordable health and care for all. While several factors contribute to the complexity of the challenges, public management research has pointed to inherent paradoxes and associated leadership tensions (see previous section). Effective leadership in this context requires practitioners to recognize the complex webs of overlapping, dynamic systems and to work with the competing demands that emerge. However, to our knowledge, research to date has not explicitly recognized the challenges this context poses in terms of multi-level leadership and therefore has not explored whether a paradox lens can aid the development of practice-oriented leadership theory. In this paper, we recognize the ICS context as inherently paradoxical and use principles of paradox to highlight the challenges of multi-level leadership.

Method

Research Context

The data were derived from a broader research and evaluation project undertaken in an ICS in England. ABC ICS (a pseudonym) was established as a vanguard ICS in 2017 to give people the health and care support they need, joined up across local councils, the NHS, and other partners. With a combined workforce of over 60,000 employed in partner organizations, ABC ICS removes traditional divisions between hospitals and family doctors, physical and mental health, and NHS and council services. In the past, these divisions have meant that too many people experienced disjointed care.

ABC ICS operates at three levels: the ICS itself operates at the system level, covering the entire population of circa 1 million people; at the time, three PBPs (now four) operated at the level of place, organizing health and care for populations of 250,000–500,000; and 20 PCNs formed from groups of General Practice surgeries working with other local providers including community services, social care and the voluntary sector, to coordinate health and care for their local neighborhoods with populations of 30,000–50,000. As such, it is a multi-level, multi-professional and multi-place initiative.

Research Design

Since we wanted to learn from participants’ direct experience of multi-level leadership, we employed a multi-modal design, informed by principles of collaborative inquiry, that emphasized interpersonal dialogue and the development of ‘communities of inquiry’ (Reason & Bradbury, Citation2006, p. xxv). The aim was to design a research process that would allow us to learn from leadership practice with practitioners (Ospina et al., Citation2008) driven by ‘an abiding respect for people’s knowledge and for their ability to understand and address the issues confronting them and their communities’ (Brydon-Miller et al., Citation2003, p. 14). We decided that collecting data through two parallel methods, narrative inquiry and co-creative inquiry, would allow us to develop local knowledge through participation (Reason & Bradbury, Citation2006).

The narrative inquiry involved extended interviews with 19 people in system-leadership roles that brought them into contact with all or part of ABC ICS. They came from different aspects of the ‘system’. In their roles, they experienced, witnessed, modelled and influenced multi-level leadership practice. We had interviewees from all three levels of the system – ICS, PBP and PCN – allowing for enough representation of system parts ranging from primary care to social care, from public health to family and children services, from statutory organizations to community and voluntary sector. In addition to system leaders in clinical roles, we also interviewed those with an administrative/management background, such as programme directors for people and culture, improvement, and place and communities. This variety allowed us to gain insight into how multi-level leadership is experienced and perceived in and across different parts of the system.

The focus of the interviews was their everyday leadership work within the ICS and their perceptions and experiences of the aspects of leadership that the ICS exemplified. Interviews were conducted by three members of the research team, with questions adapted from a semi-structured interview guide to ensure comparability. As each interview progressed, expectedly, the conversation moved away from the interview guide and required reflexive, dialogic work of meaning-making by the participants and us. All interviews were conducted via MS Teams and lasted between 40 and 70 min. They were recorded and transcribed in full.

The co-creative inquiry involved 12 workshops conducted following an open invite circulated to people across ABC ICS partner organizations, including the NHS, local authority, and community/voluntary organizations. The open invite stated that anyone who ‘can contribute to an understanding of current system working’ and ‘have experiences to share’ was welcomed. In total 86 people (plus facilitators) participated. Given the highly politicized context, to protect the anonymity of participants and to offer a safe space for them to voice their opinions and experiences freely, we did not collect participant information that would reveal the sector (i.e. health, local authority, voluntary, community), the organization they were employed by, or information about their job role or occupation. We recognize that this choice constrains our ability to gain insights into potential differences of experience, however we felt this was necessary to ensure open and honest discussions. Two members of the research team facilitated each workshop. This allowed one member to focus on facilitation while the other could observe the dynamics and record data. The workshop space was gently structured around the themes of appreciative inquiry (Watkins et al., Citation2011) to capture the reflections, observations, representations, and stories around participants’ experiences of leadership and to look at its challenges.

The workshops utilized a range of creative methods, such as drawing, story writing and metaphorical thinking, to (a) discover the current state, (b) collectively envision a future, dream state for the ICS, and (c) to elicit practical steps to bridge the gap between the current and dream states. With this three-tiered workshop design, we were able ‘to weave the web of meaning that endures – continuity, novelty, and transition’ (Watkins et al., Citation2011, p. 214). Generative questions and expansive orientation were built into facilitation to ensure that participants did not confuse our appreciative approach with whitewashing the messiness and the problematics of their lived experience (Bushe, Citation2007). The visual and written material provided by participants, which were completed anonymously, were recorded and stored for further analysis. These were complemented by rich field notes taken by the research team. The discussions in the workshops were not audio or video recorded.

Data Analysis

The interview transcripts and workshop summaries enabled the researcher who had conducted them to refresh his/her memory of the discussions. The data analysis process then began by collating the data allocated amongst the members of the research team to enable an initial synthesis by method – interviews and workshops. While two members of the research team immersed themselves in reading through the interview transcripts, the other two focused on workshop materials. Participant accounts abounded with situations where they needed to handle interdependent and contradictory elements. Examining transcripts, we identified patterns and variance in descriptions of leadership tensions using language indicators such as: ‘yet’, ‘but’, ‘on the one hand … on the other hand’, ‘fine line’, balance’, ‘how can you … and still … ’ We also identified contradictory statements within the same transcripts, where, for example, one participant called for shared systems and a common approach but also expressed a desire for local autonomy and flexibility to develop and test new approaches. Even more interesting, however, was that participants did not depict these tensions as either/or trade-offs. Instead, they saw them as synergistic and interwoven; both polarities were perceived as vital to their practice of multi-level leadership.

The conflicting demands the participants faced in their leadership and the contradictions they experienced and responded to inspired us to adopt a paradox lens. Guided by the method developed by Huxham and Beech (Citation2003), further analysis focused on conceptualizing the key tensions within each theme.

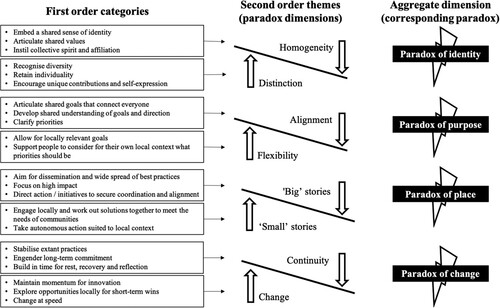

Following the principles of thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), initial codes were generated inductively from the data that offered general insights into leadership tensions as described by participants. We then searched for links between and amongst initial codes, and only the most robust codes were taken to the next stage of analysis and were reduced to eight second-order themes. During this process, regular reference back to the data was made to ensure our interpretations of participant perceptions and experiences were appropriate to achieve credibility/validity within our research findings (Tracy, Citation2010). We labelled these second-order themes either by capturing the content at a higher level of abstraction or by referring to existing literature that described similar notions.

Using paradox theory to further refine data, emergent second-order themes were aggregated as four paradoxes, as outlined in below.

Findings

Data analysis highlighted that in developing multi-level leadership practice, leaders experienced contradictory expectations and demands, characterized by a tension between two polarities. The tensions experienced in implementing and leading within ICSs demonstrate the multi-level, multi-domain and multi-faceted nature of such work (Bryson et al., Citation2017). Key thematic areas are presented below in a non-prescriptive manner, acknowledging the practical tensions of the paradoxes and the positive and negative sides to ways of leading (Vangen, Citation2017; Vangen & Huxham, Citation2012).

Paradoxes of Identity

Paradoxes of identity reside in the tensions and interdependencies between homogeneity and distinction. They are further fueled by the perceived and historic power imbalances between professions and partner organizations and sectors.

ICSs are based on the principle of cross-sector collaboration and partnership working between stakeholders with a wide range of occupational, professional and organizational backgrounds. The need to embrace this diversity is widely recognized but can be difficult in practice, where there is a need to articulate and embed a strong sense of shared identity at the system level. The tension arises when individuals and organizations constituting the ICS seek both homogeneity and distinction. The paradox experienced entails the question of how to become integral members of the ICS and commit to its purpose while retaining the individual distinctiveness and richness that stems from their diverse occupational and professional backgrounds and organizational and group affiliation.

Participants perceived that a strong sense of occupational and organizational identity can lead to professional territoriality and tribalism, posing a barrier to affiliation with the wider ICS collective. In relation to organizational affiliation, participants suggested this was experienced most strongly by those in more senior leadership roles, who were seen to be rewarded for acting in the best interests of their employing organization, which were not always aligned with those of the ICS. The notion of becoming ‘organizationally agnostic’ was used regularly in interviews and workshops to describe the shift in mindset participants felt was needed in response. The Covid-19 pandemic brought this even more clearly into view, as one participant put it:

We all want to save lives, in our population, through whatever contribution that we’re all making. And we all sort of pitched in really, together and we thought of our resources as, as a collective – in a different way and not in an organisational way. It was a total change of mindset.

It’s just screaming out to start to address … it really needs a massive PR exercise of a roadshow … this is what the ICS is, this is what is coming for you … How can you drive it forwards?

This is so health dominated … We’re not actually going to achieve what we said we’re going to achieve, because we know that health is a really small portion of the ICS … If this is really a partnership, you can’t have some partners that are more equal than others.

How do we deliver the system, through a partnership, that’s built on trust, safety, and a can-do attitude … and I still don’t think we’ve established both trust and safety. I think there’s still quite a lot of power struggles in our system.

So I think they don’t realize the impact that they have within their own organizations or across the system when they say one thing and then go out of the room and do something completely different.

Paradoxes of Purpose

Paradoxes of purpose manifest in the tensions and interdependencies between alignment and flexibility around the interpretation and enactment of ‘shared purpose’. They may be deepened, in the absence of strong relationships, by limited shared understanding of this purpose and its translation into practice.

An interrelated set of paradoxes link to notions of creating and sustaining a compelling sense of shared purpose within a diverse network of partners whilst continuing to recognize the plurality of voices that reflect and articulate local concerns. Participants highlighted the need to create and make a case for a simple, shared and meaningful purpose that might be best solved at the system level rather than by individual organizations. The example quoted most often by participants was that of reducing inequalities in access to health and care, which requires simultaneous attention to system-wide collective effort and local-level attention to pockets of deprivation and isolation. The ideal environment is described as one where everyone has the same goal and works together to reach that goal. ‘Working collaboratively and not competitively’ as a ‘united front’ were phrases repeated by several participants. This reflected a desire to avoid seeking different and sometimes incompatible outcomes that would cause confusion and conflict between partner organizations.

The quotes above suggest purpose was interpreted as a set of goals or outcomes, suggesting the challenge is less around creating a sense of shared purpose (interview and workshop participants were almost unanimous in their claim of reducing health inequalities as the ICS’ purpose) but rather around how this is interpreted, understood and brought into practice. For example, participants noted that local authority partners often referred to ‘residents’ and ‘populations’, while NHS partners often used words such as ‘patients’ and ‘conditions’. One participant in a co-creation workshop posted an image of lots of small islands separated by different amounts of water, whilst another likened the ICS to a large wedding:

We think we all know why we are here, but some are in the kitchen, some in the marquee, some dancing, some playing with the dog. And most people are talking to friends and family they know. But are we really all connected and focused on the same thing?

There are so many priorities, that almost says no priority.

Participants recognized and celebrated the combined capability inherent in the ICS. However, they also noted that without a shared purpose underpinned by shared understanding and direction, it is difficult to capitalize on this diversity in the everyday. The ICS was likened to an ant colony: individual parts all working very hard but not always together. For example, participants working in the NHS recounted instances when ‘improvement tools’ – a set of techniques that NHS staff may be trained in – broke down as soon as they crossed organizational boundaries because of the absence of a shared understanding of their purpose.

Several participants remarked that the practice of multi-level leadership involves bringing together ICS members from different organizations to have respectful conversations, determine meaningful and shared goals to bring direction, and advance collective work. This suggests a view of leadership as a relational process by which actors engage in shared meaning-making to achieve the collective purpose. Indeed, in one interview, a senior leader used the metaphor of not getting hung up on the ‘pipework’ when the ‘quality of the water’ is important. Their view was that there is a tendency to over-focus on forming new structures and regulatory frameworks when what most contributes to health and care services is the quality of relationships. These relational aspects, emphasizing engagement and equity, might have the enduring potential to facilitate sustainability and transcend paradox.

Paradoxes of Place

Paradoxes of place are found in the tensions and interdependencies between the ‘big stories’ of strategic direction and intent and the ‘small stories’ local conditions and community-based action. They may be further fueled by disparities of voice and the composition of those with ‘seats at the table’.

The complex structure of the ICS, covering multiple sub-regions, each with their own specific characteristics and issues, highlights the tensions inherent in conceptualizing and working with a ‘place-based’ approach to leadership where the boundaries between places are unclear and/or overlapping. Participants noted the importance of having a sense of place that is ‘small enough’ for local engagement and simultaneously ‘big enough’ for efficiencies of scale. Having shared systems and protocols was deemed valuable by participants to avoid repetition and ensure effectiveness and consistency. Participants recounted stories of when this was lacking and improvements that had already been made were undermined. In this sense, ‘the big place’ was perceived as an enabler of more integrative, cross-organizational work. On the other hand, great importance was attached to engaging locally to work out solutions to meet the needs of local communities and households to ensure that the ICS does not airbrush out heterogeneity and nuances across the region. For this, leaders recognized a need to make use of local authority contacts and ways of engaging local people and simultaneously combine them with NHS resources and broad talents.

Ask the people on the ground doing the work for their input and ideas.

… the right people in the room … with the subject matter, expertise, clinical leadership, and just give them the mandate and authority to work out what the solutions are together and thrash it out between themselves in a constructive way. Because that generates energy and different ideas.

A central model should not control. It should connect.

Good things are happening, but many people don’t know about them, which means the chances of ‘spread’ are limited, and people get tired and disillusioned.

Organizations (and individuals if I’m being honest) like to hold onto their own best practice a lot of the time because it makes us stand out as doing something well/differently. I was advised to trademark this work and sell to other places, and I think that sums up some of the challenge because financially that would have been brilliant for my organization, but it doesn’t feel in the ethos of working collaboratively. Also, now I’ve left that organization the work has stopped which is a lesson for me in sustainability! By the end what I’ve learnt is that it’s better to start something ICS to begin with so that the organizational walls can’t be built around it. Our go-to should be ‘can we do this at a system level to begin with and if not, why not’.

The difficulty is … a clinical director on one day a week, just hasn’t got the capacity to be keeping all the GPs briefed … And often they don’t know who to even speak to, and they’ve been catapulted into a new world. So it just doesn’t feel like it’s relevant to them … So there’s a lot of scapegoating and externalizing … They just don’t see that this is relevant to them in their day job. They’re front line, they’re putting out fires. What’s all this that’s happening somewhere behind them?

Paradoxes of Change

Paradoxes of change emerge in the tensions and interdependencies between continuity and change. They may be deepened by (change) fatigue and the squeezing out of time for recovery and reflection.

Leadership work in the ICS poses challenges around mobilizing disruptive change whilst maintaining a coherent narrative and staff wellbeing. Whilst the formal establishment of ICSs across England took place in 2022, initiatives concerned with collaborating across professional, organizational and sectoral boundaries to support ‘patient-centered care’ have a much longer history that many of our participants carried with them into their expectations of ‘making change happen’ in the ICS.

Thus, in the ICS context, the dominant image they portrayed was that of a hierarchical, moribund bureaucracy, where leadership is closely related to the idea that change has to be made to happen. Against a background of inertia, our participants felt the pressure to ‘do something’.

When we took away some of that nonsense, and we allowed our teams on the ground to get on with it, invariably, they knew what the hell needed to be done. We just needed to enable them to do it.

I think there’s a bit of learning there about, we’re going to need to build that into our way of working more explicitly and not implicitly. And more deliberately to give people some, you know, recovery time.

Perhaps just thinking a little bit more limitless. So rather than thinking in the boundaries of your own organization, it’s how colleagues could come together and just think a little bit about the potential of what working together could achieve.

There is now an overwhelming emphasis on action at the expense of reflection … There has been a flourishing of creativity and innovation, but we haven’t had time to think about doing things differently.

We’ve got the principles – [but] not quite got the metrics right. How we’re going to measure and hold ourselves to account to get there?

I think my concern is, we’re about to go into another reorganization to move into the ICS. So, on a personal level, for me, it will be my third restructure in five years. And this is the difficulty, I think, where you start to shed staff and you lose that organizational memory … Five years ago, we knew what we needed to do in many ways. But now we’re still talking about it, five years on. So I think, on an overlay of the pandemic, there’s an element of some people thinking, ‘I genuinely can’t keep doing this, because we’re not getting anywhere’.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that multi-level leadership, despite being deemed necessary to enhance the capacity for partnership working to pool expertise and resources for improved health care, poses significant challenges around navigating the salient tensions of identity, purpose, place and change. Leaders develop practices to respond to the paradoxical demands of engendering a homogenous system-identity whilst recognizing distinctiveness of organizational/professional identity; articulating a shared purpose whilst allowing for locally relevant goals; focusing on system-wide impact whilst engaging locally; and maintaining the momentum for change whilst stabilizing extant practices. Furthermore, tensions operate between, as well as within, the four paradoxes we observed. Paradoxes of identity and purpose spur tensions when identification and goals clash, apparent in participants’ efforts to negotiate the delicate balance between the individual and the aggregate. Paradoxes of place and change reflect conflicts between system-level change that is necessary for its sustainability in the long run and the desire to take timely and thoughtful action that is responsive to the needs of staff and local communities.

Paradoxes can cause confusion – leaving people paralyzed by conflicting demands. As a result, leaders and managers can feel forced to choose sides with the hope of reducing complexity and achieving clarity and direction by returning to familiar patterns of behavior between sensemaking and sensebreaking (Murphy et al., Citation2017). Despite the intention of reducing uncertainty, however, Lüscher and Lewis (Citation2008) found that the more leaders and managers stress one polarity, the more this accentuates the other. Supporting this finding, we saw that, for example, the more participants discussed the value of diversity of perspectives, experiences and identities, the more this highlighted the need for a shared identity to ensure a common understanding and mutually-agreed priorities.

Where participants did feel they had at least made progress toward a shared understanding and priorities, we observed that they had found a sense of purpose that balanced its indefinable and definable elements (Bülow & Simpson, Citation2022). For example, many of our participants shared stories of where the urgency of the sensebreaking of the Covid-19 pandemic had shown how leaders at all levels could collaborate across organizational and professional boundaries by embracing both homogeneity of purpose – protecting as far as possible the health of their population – and heterogeneity in the distinctive contribution their professional and organizational capabilities could make to achieving it. In doing so, they drew on both administrative/operational and adaptive leadership practices (Murphy et al., Citation2017; Uhl-Bien, Citation2021).

As one of our participant quotes above proposes, this took ‘a total change of mindset’, suggesting that leaders respond to paradoxical tensions by intentionally cycling back and forth amongst competing polarities – attending to and pursuing them to ensure simultaneous attention over time, in a dynamic equilibrium model that embraces paradox rather than seeking to resolve it (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011). This required leaders to reframe relationships emphasizing engagement and equity rather than just efficiency and effectiveness (Bolden, Citation2020). Enabling, multi-level leadership conceived of ‘place’ not only as a geographic location of decision-making but also as having ‘the right people in the room’, recognizing the significance of localized interactions in generating wider patterns of emergence (Stacey, Citation2006).

Here we can also highlight another paradoxical tension; at the point we are under the most time pressure, slowing down and making time for generative conversations is particularly valuable. A process of weaving antithetical elements into an integrated whole is facilitated when leaders can facilitate productive, reflexive conversation regarding the lived tensions. Within our study, many participants remarked that they found the experience of contributing to the research cathartic and generative. This suggests that a facilitated dialogue on these issues can inspire organizational actors to embrace or reframe tensions in ways that ease or release, rather than eliminate or ignore, seeming contradictions.

The simple act of articulating complex, sometimes contradictory, thoughts and feelings can unravel a previously tangled set of concerns. The challenge is no less, but when the true complexity is recognized, an ‘adaptive space’ (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2017) can be created where people can negotiate new meanings and new ways of working. In being reflexive to how tensions are managed, leaders can learn to identify zones for experimentation where approaches can be tested, learning takes place, and stakeholders are not affected by the tests. Indeed, some of our research participants found innovative, potentially transformative localized actions and micro-practices in forming feasible responses to the tensions.

In our research, we found that our participants tried to carefully oscillate between communicative actions aimed at affirming a logic of homogeneity (emphasizing direction and alignment) and actions aimed at diversity (acknowledging unique local contributions and innovations); or between actions aimed at widening impact and best-practice transfer, actions aimed at local engagement and place-based innovation. We are not alone in proposing this. Some paradox studies are also illustrative of such purposeful iteration between alternatives. Denis et al. (Citation2001), in their study of healthcare organizations, for example, proposed that to allow a substantive strategic change in a pluralistic setting, leaders need to shift between tensions of forceful action and approval seeking. Likewise, Klein et al. (Citation2006) found that emergency room trauma teams dynamically shift leadership between formal and informal leaders, thereby enabling both structure and flexibility.

We found this careful oscillation was crucial for recognizing the duality, the ‘both/and’ of paradox and pursuing a state of dynamic equilibrium rather than seeking to resolve it. The strategy of oscillation required leaders to develop their capacity for Janusian thinking and to cultivate ‘the capacity to conceive and utilise two or more opposite or contradictory ideas, concepts, or images simultaneously’ (Rothenberg, Citation1971, p. 197, emphasis in original). In multi-level leadership practice, working with paradox (rather than seeking to resolve or eliminate it) meant recognizing and unravelling its power to generate creative insight and change.

Conclusion

This paper has sought to highlight the tensions within the practice of multi-level leadership in complex systems, and to demonstrate to policymakers and practitioners the inherent challenges within often-competing concerns. In doing so, we adopted a paradox lens and suggested that leadership in multi-level contexts requires navigating paradoxical tensions. Our starting premise is that leaders need to direct their attention away from fixing or resolving paradoxes towards accepting and embracing them. Drawing on empirical research in an ICS in England, we explored what paradoxes exist, how they manifest themselves, and how leaders engage with paradox to stimulate change.

These paradoxes were experienced, by our participants, in daily leadership practice as fueling ambivalence, frustration, doubt or anxiety. In this respect, multi-level leadership is challenging as it recognizes that there will always be competing priorities and agendas and that even effective leadership will not resolve them. However, we argue that these paradoxical tensions are potentially productive and may even facilitate momentum and change in an increasingly turbulent world (see, for example, Murphy et al., Citation2017). To create value, paradoxes need to be reframed from either/or to both/and (Smith et al., Citation2016) since failure to attend to one or another polarity will lead to significant difficulties in the long term. This is particularly true of complex, multi-level environments, such as the ICS example outlined in this paper, yet the relatively detached way in which policy is formulated and implemented may confound such efforts.

Given the idiosyncratic nature of organizing, the paradoxes identified in this paper are not definitive and unchanging. Therefore, enhancing practitioners’ ability to work with them in ways that are appropriate to their particular situation requires an in-depth exploration of conditions within each paradoxical tension (Vangen, Citation2017). More needs to be understood about how leaders learn to cope with ambiguity and uncertainty and can apply this to navigate paradoxes. In this paper, we have shied away from providing normative guidance as that would reflect neither the idiosyncratic nature of paradoxical tensions nor the importance of leadership reflexivity in addressing them. Instead, we have aimed to support reflective consideration of paradoxicagool tensions specific to the context and have identified factors that enable/constrain this capacity to be developed and enacted within public services.

As the ICS model is rolled out across the health and care system in England and elsewhere, paradoxes and tensions will be experienced at all levels. Despite this, empirical studies of paradox are rare, and we know little about why some people thrive whilst others struggle. The capacity for leaders in the NHS and beyond to work effectively with paradoxes is an area that needs further research and development and is likely to prove pivotal in the success, or not, of such initiatives.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The terms ‘system’ and ‘systems’ leadership are used interchangeably in the literature. Within this paper we use the plural form to highlight that the work of health and care does not fall within a single, bounded system but rather across multiple, interconnected systems – the boundaries, content and purpose of which may be redrawn depending on who is involved and what they are trying to achieve.

2 A wicked problem is one that is challenging to find a solution to because of complex, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize and/or achieve agreement about (Grint, Citation2010).

References

- Best, A., Greenhalgh, T., Lewis, S., Saul, J. E., Carroll, S., & Bitz, J. (2012). Large-system transformation in health care: A realist review. The Milbank Quarterly, 90(3), 421–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00670.x

- Bevan, H., & Fairman, S. (2014). The new era of thinking and practice in change and transformation: A call to action for leaders of health and care. NHS Improving Quality (Department of Health).

- Bolden, R. (2011). Distributed leadership in organizations: A review of theory and research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(3), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x

- Bolden, R. (2020). Systems leadership: Pitfalls and possibilities. National Leadership Centre.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brydon-Miller, M., Greenwood, D., & Maguire, P. (2003). Why action research? Action Research, 1(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/14767503030011002

- Bryson, J., Sancino, A., Benington, J., & Sørensen, E. (2017). Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Management Review, 17(5), 640–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1192164

- Bülow, C. V., & Simpson, P. (2022). Negative capability in leadership practice: Implications for working in uncertainty. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bushe, G. (2007). Appreciative inquiry is not about the positive. OD Practitioner, 39(4), 33–38.

- Charles, A. (2022). Integrated care systems explained: Making sense of systems, places and neighbourhoods. The Kings Fund. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/integrated-care-systems-explained.

- Clegg, Stewart R, da Cunha, João Vieira, & e Cunha, Miguel Pina. (2002). Management Paradoxes: A Relational View. Human Relations, 55(5), 483–503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726702555001

- Crosby, B. C., & Bryson, J. M. (2005). Leadership for the Common Good: Tackling public problems in a shared-power world. Jossey-Bass.

- Denis, J. L., Lamothe, L., & Langley, A. (2001). The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 809–837. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069417

- Denis, J.-L., Langley, A., & Sergi, V. (2012). Leadership in the plural. Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 211–283. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2012.667612

- DoHS. (2021). Integration and innovation: Working together to improve health and social care for all. The Department of Health and Social Care.

- Doos, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2021). Fifty-five years of managerial shared leadership research: A review of an empirical field. Leadership, 17(6), 715–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/17427150211037809

- Ford, J. D., & Ford, L. W. (1994). Logics of identity, contradiction, and attraction in change. The Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 756–785. https://doi.org/10.2307/258744

- Ghate, D., Lewis, J., & Welbourn, D. (2013). Systems leadership: Exceptional leadership for exceptional times. Virtual Staff College.

- Grint, Keith. (2010). Wicked Problems and Clumsy Solutions: The Role of Leadership. In Stephen Brookes & Keith Grint (Eds.), The New Public Leadership Challenge (pp. 169–186). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huxham, C., & Beech, N. (2003). Contrary prescriptions: Recognizing good practice tensions in management. Organization Studies, 24(1), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024001678

- Jarzabkowski, Paula, Lê, Jane K, & Van de Ven, Andrew H. (2013). Responding to competing strategic demands: How organizing, belonging, and performing paradoxes coevolve. Strategic Organization, 11(3), 245–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1476127013481016

- Klein, K. J., Ziegert, J. C., Knight, A. P., & Xiao, Y. (2006). Dynamic delegation: Shared, hierarchical, and deindividualized leadership in extreme action teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(4), 590–621. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.51.4.590

- Knight, E., & Paroutis, S. (2017). Becoming salient: The TMT leader’s role in shaping the interpretive context of paradoxical tensions. Organization Studies, 38(3–4), 403–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616640844

- Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. The Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 760–776. https://doi.org/10.2307/259204

- Lewis, M. W., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Paradox and a metatheoretical perspective: Sharpening the focus and widening the scope. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886314522322

- Lüscher, L. S., & Lewis, M. W. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: Working through paradox. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.31767217

- Murphy, J., Rhodes, M. L., Meek, J. W., & Denyer, D. (2017). Managing the entanglement: Complexity leadership in public sector systems. Public Administration Review, 77(5), 692–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12698

- Nielsen, R. K., Bevort, F., Henriksen, T. D., Hjalager, A.-M., & Lyndgaard, D. (2023). Navigating leadership paradox: Engaging paradoxical thinking in practice. DeGruyter.

- Ospina, S. M., Foldy, E. G., Fairhurst, G. T., & Jackson, B. (2020). Collective dimensions of leadership: Connecting theory and method. Human Relations, 73(4), 442–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719899714

- Ospina, S. M., & Saz-Carranza, A. (2010). Paradox and collaboration in network management. Administration & Society, 42(4), 404–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399710362723

- Ospina, Sonia, Dodge, Jennifer, Foldy, Erica Gabrielle, & Hoffman-Pinilla, Amporo. (2008). Taking the action turn: Lessons from bringing participation to qualitative research. In Peter Reason & Hilary Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice (pp. 420–434). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934.n36

- Pollitt, A., Strang, L., & Pow, R. (2021). Effective use of early findings from NHS CHECK to support NHS staff. The Policy Lab. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/effective-use-of-early-findings-from-nhs-check-to-support-nhs-staff.pdf.

- Poole, M. S., & Van de Ven, A. H. (1989). Using paradox to build management and organization theories. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 562–578. https://doi.org/10.2307/258559

- Putnam, L. L., Fairhurst, G. T., & Banghart, S. (2016). Contradictions, dialectics, and paradoxes in organizations: A constitutive approach. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 65–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1162421

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.) (2006). Handbook of action research (Concise Paperback Edition).

- Reed, S., Schlepper, L., & Edwards, N. (2022). Health system recovery from COVID-19: International lessons for the NHS. Nuffield Trust. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2022-03/health-system-recovery-final-pdf-1-.pdf.

- Rothenberg, A. (1971). The process of Janusian thinking in creativity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 24(3), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750090001001

- Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The Art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday.

- Senge, P., Hamilton, H., & Kania, J. (2015). The dawn of system leadership. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 13(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.48558/yte7-xt62

- Senge, P., Smith, B., Kruschwitz, N., & Laur, J. (2010). New thinking, new choices. The Systems Thinker, 20. https://thesystemsthinker.com/new-thinking-new-choices/.

- Smith, C., Neve, G., Manley, O., Jackson, G., & Taylor, A. (2021). Future systems leadership scoping project. NHS Confederation.

- Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0223

- Smith, W. K., Lewis, M. W., & Tushman, M. L. (2016). Both/and leadership. Harvard Business Review, 94(5), 66–70.

- Stacey, R. (2006). Ways of thinking about public sector governance. In R. Stacey & D. Griffin (Eds.), Complexity and the experience of managing in public sector organizations (pp. 15–39). Routledge.

- Sweeney, A., Clarke, N., & Higgs, M. (2019). Shared leadership in commercial organizations: A systematic review of definitions, theoretical frameworks and organizational outcomes. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(1), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12181

- The Lancet. (2021). The NHS: The many challenges for leadership. The Lancet, 398(10300), 559. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01850-X

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–885. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Uhl-Bien, M. (2006). Relational leadership theory: Exploring the social processes of leadership and organizing. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 654–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.007

- Uhl-Bien, M. (2021). Complexity leadership and followership: Changed leadership in a changed world. Journal of Change Management, 21(2), 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1917490

- Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., & McKelvey, B. (2007). Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(4), 298–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.04.002

- Uhl-Bien, Mary, & Arena, Michael. (2017). Complexity leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 46(1), 9–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2016.12.001

- Vangen, S. (2017). Developing practice-oriented theory on collaboration: A paradox lens. Public Administration Review, 77(2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12683

- Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2012). The tangled web: Unraveling the principle of common goals in collaborations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(4), 731–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur065

- Watkins, J. M., Mohr, B. J., & Kelly, R. (2011). Appreciative inquiry: Change at the speed of imagination (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Whelehan, D. F., Alego, N., & Brown, D. A. (2021). Leadership through crisis: fighting the fatigue pandemic in healthcare during COVID-19. BMJ Leader, 5(2), 108–112. doi:10.1136/leader-2020-000419