Mervyn King may well have written the most important book to come out of the financial crisis. … Agree or disagree, King's arguments deserve the attention of everyone from economics students to heads of state. (Lawrence H. Summers, Harvard University & former US Secretary of the Treasury)

In the long preface to the 2017 paperback edition of his best-selling 2016 book, Lord King summarizes the arguments of the book in light of four key concepts upon which his analysis of international capital markets and the global economy is based: radical uncertainty, disequilibrium, the prisoner's dilemma and trust. The unknowable future inevitably leads to realized policy mistakes occasionally resulting in serious international economic ‘disequilibrium’ requiring cooperation and trust to overcome the prisoner's dilemma faced by individual nations who can suffer by acting alone instead of benefiting from acting in concert. He goes on to describe the international disillusionment caused by the 2007–2008 crisis and the inadequacy of the widespread printing of money (so-called ‘quantitative easing’ to which he was party as Governor of the BoE), of negative interest rates and even of fiscal policy in rectifying the situation and stabilizing the global banking system. With hindsight, he puts this down to the failure of current economics to understand that the growth rates of the two plus decades of the ‘Great Moderation’ previous to the crisis were unsustainable. He also notes that Brexit and President Trump are symptoms of the disillusionment of advanced economy voters with the unequal benefits of globalization, a situation yet to be resolved. He proposes that reforming the ‘alchemy’ of money and banking intermediation can brought about by requiring that ‘banks should be required to bring collateral to their central bank well in advance of a crisis so that they can obtain a cash credit line that can be called upon in times of crisis’. This would make the central bank a ‘pawn broker of last resort’ rather than Bagehot's nineteenth century ‘lender of last resort’ (Bagehot Citation1873).

At the time of writing of the paperback edition, 18 months ago in December 2016, its author notes that economic recovery in much of the industrialized world is not yet in sight and that current post-crisis banking regulation, while complex and costly, cannot guarantee financial stability going forward. Further, King notes that as well as reflecting the growing divergence between the values of the European elite and the British population, the Brexit referendum demonstrates disillusionment with the economics profession. He views all of this as reinforcing the book's main arguments. Currently however the global economy is seen to be growing, with downside risks rising and once again new financial products such as CoCos (contingent collateralized debt obligations) and ESBies (European ‘safe’ bonds) guaranteeing the virtually instant global contagion of any future financial market collapse, while much economic debate and policy advice continues to appear irrelevant and the power of the EU elite continues to increase, at the expense of true democratic values and the EU citizenry.

These developments, which are contrary to the views expressed in the book, are representative of the shorter term views which I see as permeating it and which from my perspective are inappropriate to address its most important topic: central bank policy and regulation to promote financial stability. On this topic, I find myself in agreement with the current Chief Economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haldane, and the Global Chief Economist of Citigroup, Willem Buiter, that simpler is better and the traditional approach involving the close monitoring of credit and the financial markets is a necessity. Krugman (Citation2016) goes even further in his review of the 2016 hardback edition of King's book, asserting that the book's final policy suggestions are ‘the same as the recommendations of every IMF program for the past sixty years: structural reform and free trade’ and comments ‘Really? That's it?’Footnote† But more of this in the sequel, as I now attempt to summarize the contents of a book consisting of the new introduction and nine chapters unchanged from 2016.

To my reading, King's arguments are distributed randomly and repetitively throughout the book—a situation not helped by the ambiguity of ‘catchy’ chapter titles such as ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ (Chapt. 1) and ‘Marriage and Divorce: Money and Nations’ (Chapt. 6). However, in a logical order which I therefore struggled to devine, the book's chapters treat: recent financial history, money, fractional reserve banking, financial markets, central banks, currency areas, money and banking reform, the present world economy and a coming crisis, hopefully preventable by international cooperation.

The author states in his Introduction that ‘This book is about economic ideas’ and claims that ‘Economists brought intellectual rigour to economic policy and especially to central banking’, which sits uneasily with the statement at the end of Chapter 1 that economists failed to understand that ‘money and banking [are] the Achilles heel of capitalism’. As positive examples of economists’ policy influence he cites the central role of inflation targeting by central banks, which began in the UK in 1992, just before the accession of Eddie George to the governorship of the Bank of England in 1993, and independence of the BoE from the Treasury subsequently granted in 1997 by the newly elected Labour Chancellor, Gordon Brown. In the hands of King, promoted from Chief Economist to Governor of the Bank in 2003, inflation targeting became virtually the only policy role of the Governor and the Monetary Policy Committee. To be fair, this was a partial consequence of the shifting of market oversight to the Financial Conduct Authority, also created by New Labour in 1997, but that shift did not stop Eddie George (who played a decisive role in allowing the collapse of Barings Bank in 1995) from continuing up to 2003 to closely monitor the interaction of banking and financial market activity as ‘lender of last resort’.

At a bank sponsored meeting in Germany in January 2006, at which a prominent US econometrician predicted the forthcoming US housing market crash and demonstrated the severe effects on US GDP of similar previous crashes, I became aware that his pessimistic view was widely shared by the global financial services cognoscenti. Indeed, some derivative desks were already setting up deals to profit from it. By summer 2006, I consequently worried publically about the relatively recent appointment of academic economists without significant market experience as Governors of, respectively, the BoE and the US Federal Reserve (Dempster Citation2006). In the first case this worry was subsequently justified, in the other it arguably was not, although the label academic also applies to Bernanke's successor, Janet Yellen, on whose long-term effectiveness the jury is still out, while her recent replacement, Jay Powell, is a career central banker. The book's Introduction ends with a call to end the ‘alchemy’ of fractional reserve banking (although this term is used sparingly in the book) which involves borrowing short term with demand deposits and in the money markets and lending long term to individuals, companies and institutions with potentially insufficient capital reserves to withstand a market crisis. The important question of the actual nature and quality of bank reserves is never addressed in detail in the book, only their paucity pre-crisis and a proposal to increase them substantially and collateralize them to fully cover lending.

Chapter 1, entitled ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’, is an account setting out the recent financial history of the UK in a global context. The ‘Good’ refers to the 1990–2007 ‘Great Stability’ period of 3.5% p.a. output growth of advanced economies together with only about the 2% p.a. target inflation. The ‘Bad’ identifies the resulting rise in credit and debt levels of government, industry and consumers over the same period, while the ‘Ugly’ describes the growth of a fragile aggressive highly levered global banking system. This followed Mrs. Thatcher's ‘Big Bang’ in the City of London in 1986, and the 1999 repeal of the 1933 Glass–Steagal Act separating commercial and investment banking in the US, along with a misplaced emphasis on short-term shareholder value. This situation, with the consequent financialization of the global economy, has been succinctly described by the Chief Economist of the Bank of International Settlements (and my former junior colleague at Oxford), Hyun Song Shin, as a ‘banking glut’.

Although the author asserts in the Acknowledgements and Introduction of the book that it is not a memoir, the reader will encounter throughout a curious juxtaposition of interesting, but perhaps self-aggrandizing, personal anecdotes and a cool detachment worthy of an outside academic economist describing the evolution of events over which Lord King himself actually had, or should have had, knowledge and responsibility as Governor of the BoE. This contrast is most glaring in the account of the history of the crisis in Chapter 1. Its description of the evolution of the crisis in the US and the UK dates from BNP Paribas’ suspension of redemptions for three funds invested in US mortgage backed securities on 9 August 2007 and is relatively standard. It should be contrasted with that of Turner (Citation2014) on the political economy of banking over the same period. In September 2007, Northern Rock sought support from the BoE after the first major bank run in the UK in 130 years (Turner Citation2014) and, although some support was given, the bank failed virtually immediately thereafter. At the time the Governor was widely criticized for being slow to recognize the seriousness of the Northern Rock situation (FT 2.9.17), in spite of his misleading claim in Chapter 5 that it was possible to predict exactly when it would fail. In fact, although the US Federal Reserve under the market savvy Alan Greenspan began lowering the federal funds rate again in January 2007, Mervyn King was still raising the UK bank rate in December 2007, backed by a moral hazard argument, in a mistaken attempt to discourage further bank lending and totally disregarding Northern Rock's recent failure. The actual result in late 2007 and early 2008 was the widespread sale by investment banks of structured loans and derivatives to UK small and medium enterprises (SMEs) which were designed to profit the vendor when the inevitable drop in bank rate occurred. A decade later litigation over the resulting SME bankruptcies and collateral seizures is still ongoing.

Also a High Court action has recently been brought by Lloyds shareholders against five former Lloyds directors, including the CEO Eric Daniels, regarding the purchase by Lloyds of Halifax Bank of Scotland three days after the Lehman Brothers failure on 15 September 2008, and the subsequent alleged concealment by Lloyds later in the year of support from the BoE and a £10 billion loan facility. Court testimony has revealed the role of King in this transaction in asserting to Daniels the day before the disastrous purchase of HBOS on 18 September 2008 that the alternative was nationalization with all its repercussions (FT 7.11.17). Within a few weeks, both HBOS and Royal Bank of Scotland ‘found themselves unable to get to the end of the day’ and within 32 days of Lehman's failure were recapitalized by the Bank of England to the tune of a maximum total of £61.5 billion of intraday lending. The key role of the UK Chancellor, Alistair Darling, in these decisions is not mentioned in the book, although the ‘disbelief in the voice of Fred Goodwin’, CEO of RBS, ‘as he explained [to King] what was happening to his bank’ is. In fact, after its overreaching purchase of ABN Amro, the inevitable failure of RBS was widely expected (not least by this reviewer, whose firm had a contract about to be signed with an RBS subsidiary cancelled, along with all other RBS outside contracts, in March 2008). King's claim that from the beginning of 2008 the BoE began arguing that UK banks needed a lot of new capital, up to £100 billion, is hard to recollect and seems doubtful in light of the Bank's base rate policy described above only a month previously. He goes on to describe his role at the October G7 crisis meeting in Washington as suggesting to the US Treasury Secretary, Hank Paulson, that the communiqué ultimately adopted should be a short statement of the intention of the parties to cooperate in recapitalizing the global banking system at taxpayers’ expense: the UK first, quickly followed by the US, and finally (considerably later) by Europe. The end of the actual banking crisis is seen here to be the publication on 7 May 2009 of the first ever stress tests on major US banks by the New York Federal Reserve, which showed that a total amount of new capital from public and private sources of $75 billion would be needed to put US banking back on its feet. But the wider post-crisis ‘Great Recession’ of the global economy has taken a decade to reverse.

Near the end of the first chapter, three questions are posed which the in-depth analyses of the remaining chapters attempt to answer. Namely: (1) Why was so little done to change the ‘unsustainable’ economic growth path leading up to the crisis? (2) Why has nothing been done post crisis to change the concentrated structure of the global banking industry in spite of extensive regulation? (3) Why is global demand still weak? (This last is no longer true.) A hint is given that a fundamental global ‘disequilibrium’ is their cause, but they could equally be symptoms of the financialization of the global economy. In any event, ‘disequilibrium’ as used here is a concept at odds with the notion of ‘radical uncertainty’ discussed in Chapter 4 since it presumes the existence of some ideal static state. More appropriate is the concept of dynamic evolution of short-term trading equilibrium against an unknowable future.

In Chapter 2, entitled ‘Good and Evil: In Money We Trust’, the relationship between money and banking is discussed anecdotally and historically in the context of the standard definition of money as a unit of account, a medium of exchange and a store of value. The exposition proceeds from primitive money, through coinage, banknotes, the gold standard and fiat money to current digital money, for which gold reserves are proposed. A more general proposal than the last regarding financial markets has recently been made by Grasselli and Lipton (Citation2018) for macroeconomic stabilization using central bank digital currencies and negative interest rates to enhance consumption and investment as necessary.

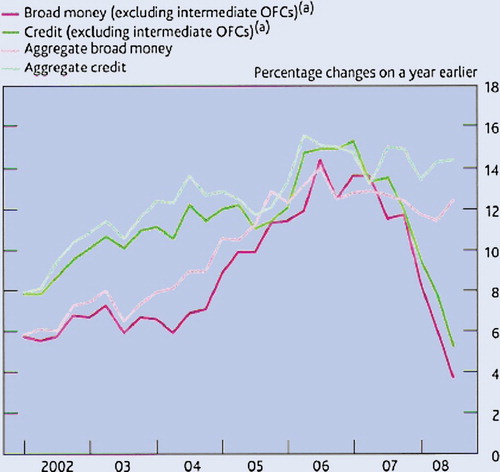

Noting that monarchs and governments over the ages have debased currencies many times, hyperinflation in the interwar Weimar republic (in which the central bank itself under Hjalmar Schacht played a not insignificant role), and in Zimbabwe more recently, is contrasted with the recent control of inflation (but not necessarily credit growth, see ) by advanced economies due to the market savvy of the best central bankers. The Arrow-Debreu world underlying much current economic analysis of market economies (but perhaps more appropriate to Saturday afternoon in the eighteenth century corn market) may be compared to the modern ‘money economy’ in which money is created as a by-product of bank credit creation. As a result, money has become a private good in the hands of the banking system. Since the breakdown of the arguably self-regulating Gold Standard in the 1930s, and that of its postwar Breton Woods successor in 1972, this situation now requires incisive but straight forward regulation in the form of credit control (see Buiter Citation2018).

Figure 1. UK credit expanded at over 3 times GDP growth rate from 2003 to the crisis. Source: Bank of England.

Chapter 3, entitled ‘Innocence Lost: Alchemy and Banking’ describes in detail the current state of the fractional reserve banking system that Lord King feels cries out for change. It begins on a personal note with his statement that ‘No doubt there were bankers who were indeed wicked and central bankers who were incompetent, though the vast majority of both whom I met during the crisis were neither’. Subsequently, however, the narrative is again decidedly that of an uninvolved academic third party. It is argued that bankers prior to the crisis, and policy makers in the crisis, all faced the prisoner's dilemma of whether or not to cooperate as they were responding to existing incentives exacerbated by complex derivative securitizations from which leading banks were profiting enormously.

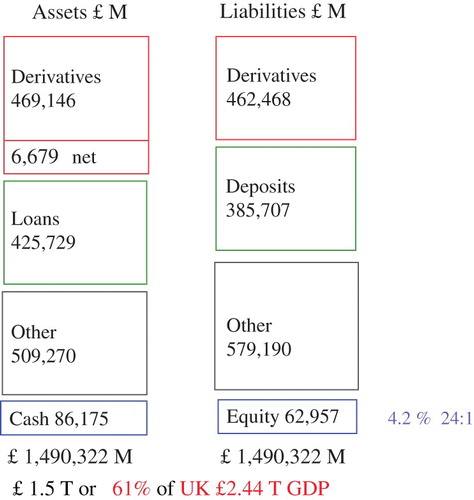

As a result, King states that Bagehot’s Citation1873 concept of lender of last resort arising from the UK banking crisis of 1866 needs updating to cope with the growth of the banking industry relative to the economy. But the task is enormous. In the US, total assets of the top ten banks in 2016 were 60% of GDP, while in the UK they were a staggering 450% of GDP, down from over 500% in 2008. In the US, the assets of Bank of America Merrill Lynch alone were $2.1 trillion or about 10% of US GDP in 2016, while shows that even after the Eurozone crisis in 2011–2012, six years after the crisis, the assets of Barclays Bank were an unbelievably high £1.5 trillion or 61% of UK GDP. The figure also shows that in 2014 the mark-to-market value of derivative assets and liabilities exceeded the value of loans and deposits, at about 30% of total assets and liabilities and 4.5% net. Overall, the gross market value of derivatives peaked in 2012 (until recently) at over $20 trillion, about one third of global GDP and half the assets of the world's top 20 banks.

The combination of classical commercial bank maturity transformationFootnote† together with derivative trading on own account with only a small proportion of dubious regulatory capital, including an even smaller proportion of shareholder equity, is seen to be the incredible insolvency risk it actually was to depositors and shareholders (albeit with limited liability). The global concentration of the banking industry reached by the time of the crisis created the concept of banking institutions ‘too big to fail’. The resulting ‘taxpayer liability’ for government bailouts represented an implicit central bank put option on an individual institution's value and an incentive to banks to increase risk. This has not always been the case; bank shareholders in the UK had full liability up to 1852, when following the 1848 banking crisis limited liability was introduced (although it was partially constrained until the early 1970s), while US bank shareholders had liability for double the value of initial purchases up to 1934, when full limited liability was introduced, together with audited public accounts and government deposit insurance. At the current level of industry concentration it is hard for central banks to distinguish illiquidity from insolvency and King argues that more capital should be required of financial institutions and that all should be tightly regulated, including money market funds and ‘shadow banks’. Somewhat puzzlingly he applauds Canada's banking industry's concentration into four big banks as allowing them to escape the crisis. Perhaps this was stated without the knowledge that in return for fees the Royal Bank of Canada was one of the largest designers—but not vendors—of the collateralized subprime mortgage obligations sold wholesale to banks marketing these toxic securities in North America (as was Nord Landesbank similarly in Germany for other toxic derivatives). Such investment banking operations and the excess profits resulting from their private returns grossly exceeded public returns and grew the value of individual institutions rapidly in the twenty-first century in the period leading up to the crisis, since high profits attract investors.

Chapter 4, entitled ‘Radical Uncertainty: The Purpose of Financial Markets’, discusses the nature and consequences for financial markets of the unknowable and ever changing future. After discussing the 1997 failure of Long Term Capital as an example of such a consequence, this chapter treats the widespread ‘illusion of certainty’ in the face of often unquantifiable uncertainty. The author describes being asked by the UK parliamentary Treasury Select Committee essentially to ‘predict the future’ as a representative instance of the commonplace problem of understanding uncertainty by ignoring its existence. The lending policy of Northern Rock with a capital ratio of 1 to 60 or 80 is seen (with more personal hindsight) to be another. The Knightian distinction between risk (quantifiable) and uncertainty (unquantifiable) is made and it is asserted that employing rules of thumb embodying ‘coping strategies’ is rational behaviour in uncertain situations. The account goes on to discuss evil derivative structures (on which see, for example, Dempster et al. Citation2012), Libor rigging and the need for all financial players, including central banks, to develop coping strategies in the face of uncertainty. In this, Lord King appears ignorant of the pioneering work at Carnegie Mellon in the 1950s of my teacher and Nobel Laureate, Herb Simon, and his colleagues on ‘bounded rationality’ and ‘satisficing’ with heuristics (Simon Citation1957). These concepts were developed in contrast to Milton Friedman's ‘as if’ approach in Chicago (from where most of the Carnegie Mellon faculty came) which is closely related to the illusion of certainty. The chapter concludes with the observation that ‘a capitalist economy is inherently a monetary economy’ with which it is hard to argue.

Chapter 5, entitled ‘Heroes and Villains: The Role of Central Banks’, and appropriately the longest chapter in the book, describes the history and changing practices of central banks from their origin in the seventeenth century up to the present day. Special emphasis is given to the role of central banking in the UK at the outbreak of the First World War post the 1907 50% market crash, in the US before the Second World War post the 1929 market crash (in which all excessive gains over the year were wiped out) and the subsequent 1931 40% market crash and, more widely, into the future post the 2008 crisis (pre the Third—and final—World War?). It is first noted that from being previously shrouded in equivocal mystique, central banks have become much more open and more lucrative due to enormously expanded balance sheets, but have striven with only limited success ‘to make monetary policy as boring as possible’. The first central bank was the Swedish Riksbank, founded in 1668, followed by the Bank of England in 1694, those of the European powers in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and, after two short lived attempts at establishing a First Bank after the birth of the US republic, the US Federal Reserve in 1914. The relative historical achievements of the Bank of England in monetary policy are put down to the “wisdom of the men who controlled its operations’. In general, central banks have learned from financial crises and, although legally challenged, their success in achieving a ‘Great Stability’ instead of a second ‘Great Depression’ post the 2008 crisis is given as an example.

The chapter goes on to discuss a central bank's traditional role in a capitalist economy of managing the money supply directly or indirectly to ensure the stability of value in good times and the supply of liquidity in bad times through its lender of last resort function. Price stability by means of inflation targeting is seen as a recent central bank coping strategy. It is embodied in the heuristics that central banks set rate policy so that expected inflation is equal to the target (2% for much of nearly three decades) and that industry decision making is predicated on inflation at the target rate. Indeed, ‘inflation targeting is about making and communicating [the] decisions’ of central banks and is contrasted with earlier attempts to control money supply based on the Fisher-Friedman quantity theory of money. Since in the 40 years from 1967 to 2007 prices rose by 750%, or 5% per annum versus a real growth rate of 3.5% p.a., these earlier attempts are rightly seen as largely unsuccessful. The shorter term rate correction strategy embodied in the 1993 Taylor rule alternative, which raises rates when the inflation rate is above target and output is above trend and lowers them when the reverse holds, is seen as influencing output and employment only in the short term, but not as influencing the actual inflation rate in the longer term addressed by inflation targeting. These ideas recur in Chapters 8 and 9 of the book regarding suggestions for future policy. Here, King asserts that attempts at credit restriction in major economies now require international cooperation to counter global capital flows. He attempts to justify the failure to control excessive UK credit rate expansion (cf. ) during his Governorship as interfering with capitalist decisions properly left to politicians in a democracy. He also notes that central banks, including the Federal Reserve and the BoE, employed bad models for policy pre-crisis which were based on representative agents with rational expectations and had no financial sector whatsoever—a broader failure in common with most of the economics profession (but see Dempster and Davis Citation1990 for an exception).

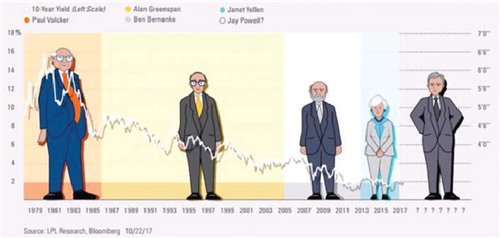

Post-crisis, the demand for money and credit was initially weak and uncertain. In order to offset severe commercial deposit balance sheet reduction, major central banks attempted to raise the growth rates of money and credit with ‘quantitative easing’ (QE), i.e. purchasing credit worthy instruments from the private sector paid for by creating (electronic) money and thereby expanding central banks’ balance sheet assets and injecting funds into the economy which hopefully would be used to spur lending, investment and portfolio rebalancing. King quotes Bernanke's quip ‘QE works in practice but not in theory’ as a call for realistic policy models to help overcome the money supply rising very slowly with near zero or negative (briefly in Switzerland and Germany) rates and near zero inflation. It has taken nearly a decade for this QE policy to begin to work, first in the US, then in the UK and finally in the Eurozone, with currently rising rates only in the Anglo Saxon economies. Confidence in central bank policy is the key to success in a crisis. King notes the steady decline in height of US Fed chairpersons depicted in until the appointment of its new Chairman, Jay Powell, who raised rates at his first open market committee meeting as Chair. The figure reveals a spurious correlation of their heights with the average rates they set during their tenures and he observes a similar decline in the heights of BoE governors over the same period to conclude that these central banks ‘have come to rely less on height and hauteur and more on transparency and the ability to look the average person straight in the eye’. The chapter ends with a history of central bank attempts to resolve crises and somewhat incongruously is mainly a detailed assessment of the Bank of England's attempts to quell market panic at the outbreak of the First World War.

Figure 3. The striking similarity between the evolution of the US federal funds rate and the Fed Chair's height. Source: Bloomberg kindly through Stefano Pasquali.

Chapter 6, entitled ‘Marriage and Divorce: Money and Nations’, investigates the intimate link between a nation state and the money in circulation within it. It is the last of the six chapters which form the preamble to the reform proposals in Chapter 7 of the book. Mundell’s (Citation1961) definition of an optimum currency area as consisting of regions which are subject to similar shocks, have a single labour market and possess a common attitude to price inflation is introduced and it is noted that having a common currency means pooling monetary sovereignty. While the last condition is of necessity true for the Eurozone, unfortunately, the first two are not—to the benefit of Germany, the Netherlands and Scandinavia, whose goods and services are undervalued by the euro, and the detriment of the remaining nations, whose goods and services are overvalued by it (see e.g. Dempster et al. Citation2012 for some suggestions for improving the situation, short of serious progress towards an EU federal union, as is currently being advocated by France and likely opposed by the exchange rate winners like Germany and the Netherlands). Contrary to a common policy towards inflation, average annual inflation rates of Eurozone nations differed widely over the life of the euro from its introduction in 1999.

The chapter gives a detailed historical account of the establishment and development of a number of currency areas in the modern era, including those of the United States, the Latin Monetary Union, Ireland before the euro, European Monetary Union, Iraq between the Gulf wars, the Eurozone and possible currency arrangements for an independent Scotland. Of these, I found events following the introduction of the US dollar in August 1786 the most interesting. However, the most extensive description is appropriately devoted to the Eurozone and, exacerbated by immigration from the war torn Middle East and Africa, its familiar crises—which are likely to continue. By and large Europeans like the euro, but not its consequences, which arise from an attempt to behave like a federal union while maintaining traditional national sovereignty (Dempster et al. Citation2012). In particular, King observes that in the 14 years from the introduction of the euro in 1999–2013 the single interest rate of the European Central Bank led to very divergent total inflation rates in Eurozone nations, with Germany the lowest at 25% (about 2% per annum average) and Spain the highest at 40% (about 3% p.a. average) with subsequently Greece even higher- a clear violation of Mundell's condition for an optimum currency area.

Chapter 7, entitled ‘Innocence Regained: Reforming Money and Banking’, and meant to be the heart of the book, gives Lord King's proposals for reforming capitalist banking structures to enhance financial stability by removing their historical ‘alchemy’. Recall that alchemy refers to governments pretending that paper money could be turned to gold with reserves only a small proportion of the money in circulation and banks pretending that short-term risky demand deposits can be used to finance long-term risky investments, as discussed in Chapter 3. In the age of electronic money, the former is no longer strictly relevant, and of more present importance than the latter is the ability of banks to create money through credit, i.e. creating deposits to support lending, and derivative securities, both of which threaten financial stability (cf. Figures and ). King states that ‘The key to ending the alchemy [of risk into safety] is to ensure that the risks involved in money and banking are correctly identified and born by those who enjoy the benefits of our financial system’, a statement with which it is hard to argue, but which is unfortunately much harder to ensure.

The author notes that any solution to ensuring financial stability must address both liquidity and solvency. His solution is that banks should be required to deposit with the central bank liquid capital, in the form of cash and securities with discounted mark-to-market values, which are sufficient to fully cover deposits. (International money market borrowing and short-term derivative liabilities are ignored here.) This proposal essentially eliminates shareholder limited liability and fractional reserve banking and makes the central bank a ‘pawnbroker for all seasons’ rather than a ‘lender of last resort’. Michael Lewis, author of The Big Short, thinks that this proposal ‘might just save the world’. I do not. Let us delve a little deeper into the chapter itself to see why.

The chapter begins with a review of currently implemented and planned sector reforms which attempt to ensure global financial stability. First, it is noted that ‘Runs reflect the underlying alchemy and make the system unstable’. But it is not clear that the ‘alchemy’ as defined by King must be ended. The last run on a major commercial bank in the UK before the 2007 run on Northern Rock was 130 years ago on the failing City of Glasgow Bank in 1878 (Turner Citation2014) which makes Bagehot’s Citation1873 ‘run’ terminology out-of-date and inappropriate today. Moreover, according to Turner the last major crisis in the UK approaching the severity for banking of the crisis in 2007–2009 was in 1878–1879.

The idea of 100% central bank liquid reserves to back demand deposits favoured by King was, he notes, first mooted in the US in 1834 by William Leggett and seriously proposed by Irving Fisher, Frank Knight, Henry Simons and Paul Douglas in the 1933 Chicago Plan as a remedy for the excesses behind the 1929 crash. The Plan was subsequently backed postwar by Milton Friedman, James Tobin and Hyman Minsky, among many others up to the present day on both sides of the Atlantic. Although arguably it is applicable to so-called ‘narrow’ commercial and retail banks,Footnote† we can see that it has seriously inadequate relevance to globally systemic ‘wide’ banks which also undertake major investment banking, market trading, private banking and asset management activities. Alone it would, therefore, fail to ‘eliminate the implicit subsidy to banking that results from the “too important to fail” nature of most banks’ as asserted by King. Moreover, it could be difficult to implement in practice, even for ‘narrow banks’—as contentious market dependent liquid collateral ‘haircuts’ would need to be continuously negotiated between banks and the central bank (cf. Krugman Citation2016). More appropriate to wide banks is the intelligent central bank discretionary guidance (possibly legally augmented) for credit control and money creation which has evolved over centuries—but which from time to time has been forgotten with very serious market and economic consequences.

Financial historians point out that over their about three and a half centuries of existence central banks’ approaches to attempting to control money supply and bank credit while ensuring stable financial markets has changed many times in reaction to circumstances (see, e.g. Turner Citation2014). In the 1950s undergraduates were taught (e.g. Spero Citation1953) that commercial banks in the US Federal Reserve system were required to maintain liquid reserves (cash, discountable paper and gold) with the central bank amounting to 13% of demand deposits, with adherence to this reserve ratio constantly re-assessed by the appropriate district reserve bank. By 1969–1970 the US reserve requirement ratio had risen to around 16% (Evans Citation1969, Ritter and Silber Citation1970) and today is at 10% of so-called net transaction account demand deposits held electronically at the Fed in the form of bank overnight reserves. However, credit control (money supply in the form of demand deposits) was, and still is, mainly achieved by the reserve bank's open market operations, i.e. buying and selling mainly US government securities with the bank. Buying securities results in expanding money available for the bank to buy other assets or make loans in the form of on demand facilities (the idea behind recent ‘quantitative easing’) and selling in reducing such current activities. Similar processes apply to other central banks, including the Bank of England, although the public emphasis has shifted to interest rate setting through inflation targeting at the cost of de-emphasizing or ignoring the rate of credit expansion, such as was done by Lord King in the UK pre-crisis. In this context the control theory maxim that multiple target variables require an equal number of control variables should be recalled—a principle germane to the US Federal Reserve Bank's mandate to control unemployment as well as money supply. In a recent note on the failed Swiss Vollgeld referendum to make the central bank the sole issuer of “money’, Buiter (Citation2018) points out that ‘demand deposit growth can be capped in a fractional reserve system (or indeed in a zero reserve system) as easily as in a 100% reserve banking system or a central-bank-only checkable deposit system [such as the crypto-currency-based Vollgeld system]’. He notes that

moving away from fractional reserve banking … will not prevent financial instability arising from maturity, currency or liquidity mismatches. [Statutory] bank deposit and lending restrictions can manage the level of bank credit creation even with fractional reserve banking, while excessive credit growth [such as seen in the UK prior to the crisis] is possible even under a Vollgeld system.

Much more importantly, the decade prior to the crisis saw a steady decline in the amount and quality of capital in banks’ balance sheets, with the equity share declining ever further. This aspect of financial instability is not discussed in any detail in the present book, but it is the focus of another important book entitled ‘The Bankers’ New Clothes, What's Wrong with Banking and What to Do about It’, published in Citation2013 by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig, which advocates a significant increase in the equity share of regulatory capital up to 20% of a bank's balance sheet as another simple approach to ensuring financial stability (see Dempster Citation2015 for a review). In the UK, restrictions on this equity balance sheet leverage have been taken up by the Bank of England and implemented by the Financial Conduct Authority in addition to other measures. The situation of inadequate capital has at best been only partially reversed since the crisis, and apparent progress in increasing regulatory capital ratios has been obtained by the introduction and widespread use by systemically important banks in the UK and EU of high yielding contingent collateralized debt obligations (CoCos) which often pay global investors nothing after a low bank stock price threshold has been crossed (see de Spiegeleer et al. Citation2017). The contagion implications for the next crisis are frightening.

Chapter 8, entitled ‘Healing and Hubris: The World Economy Today’, and Chapter 9, entitled ‘The Audacity of Pessimism: The Prisoners Dilemma and the Coming Crisis’ summarize and conclude the book. They deal respectively with a description and background of the current world economy and factors relevant to the next financial crisis without predicting its likely cause, although lack of national debt forgiveness is mentioned as one possibility. I found these two chapters to be the most interesting in the book. In more detail, the first gives an account of the evolution and inadequacies of modern macroeconomic thought, stressing the debate between Keynesians and neo-classicists and the ideas of Hyman Minsky, radical to both schools, but highly relevant to an understanding of the 2008 crisis and the role in it of radical uncertainty. The chapter goes on to give what has now become a fairly standard macroeconomic account of the causes and consequences of the crisis coloured by its author's views that pre-crisis growth rates are unsustainable going forward. The resulting interest rate rises needed to restrain excessive consumption pre-crisis are seen to have not been forthcoming because of a global prisoner's dilemma involving the central banks of the major economies. For a more market oriented account of the crisis and its causes in the classical crisis framework of Kindleberger (Citation2000) see Dempster (Citation2011). The final chapter of the book addresses aspects of the pessimism about ‘disequilibria’ of the global economy which was widespread two years ago and is currently deepened by the prospect of a major global trade war which has already begun. King rightly sees that international cooperation is an absolute necessity to overcome the global prisoner's dilemmas involving these issues, but he is not optimistic that this will be forthcoming. Nor am I.

Although I disagree with much that is said in this book, I cannot disagree with those who say that it should be read by everyone interested in—or worried about—the future of the global economy.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Mark Davis, Lisa Goldberg and Alex Lipton for comments on an earlier version which materially improved this review.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Dempster

Michael Dempster is Professor Emeritus, Centre for Financial Research, Statistical Laboratory, Department of Pure Mathematics and Statistics, University of Cambridge. He has held appointments at leading universities and consulted globally and is a founding Editor-in-Chief of Quantitative Finance. His numerous research articles and books have won several awards and he is a Fellow of the Institute of Mathematics and Its Applications, an Honorary Fellow of the UK Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, a Member of the Academia dei Lincei (Italian Academy) and Managing Director of Cambridge Systems Associates, a financial analytics consultancy and software company.

Notes

† I am indebted to Lisa Goldberg for bringing this review to my attention.

† Borrow short term with demand deposits and in the international money markets and lend long term to retail and commercial entities (in excess the downfall of Northern Rock).

† In an interesting proposal for fiat money backed digital coins involving central banks (Lipton et al. Citation2018) a more stringent definition of “narrow” bank is used which obviates bank lending and requires bank assets to be only electronic central bank fiat cash and short term government bonds.

References

- Admati, A. and Hellwig, M., The Bankers’ New Clothes: What‘s Wrong with Banking and What to Do About It, 2013 (Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ).

- Bagehot, W., Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, 1873 (Henry S King & Co.: London).

- Buiter, W., The Vollgeld Referendum. Citi Research Global Economics View, Citigroup Global Markets Inc., 8 June 2018.

- Dempster, M.A.H., The global economic and financial system. Presentation to the All-Russia Camp for Education and Innovation, Lake Seliger, Russia, 24 July, 2006. Available online at: ResearchGate.

- Dempster, M.A.H., Money, banking and the global economy: Back to the future. Cambridge Executive Education Presentation to the Central Economic Mathematics Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 25 October 2011. Available online at: ResearchGate.

- Dempster, M.A.H., 2015. The bankers’ new clothes, what’s wrong with banking and what to do about it. Quant. Finance, 2015, 15(4), 579–582. doi: 10.1080/14697688.2015.1016095

- Dempster, M.A.H., Chadha, J.S. and Pickford, D.E., The Euro in Danger: Reform and Reset, 2012 (Searching Finance: Cambridge).

- Dempster, M.A.H. and Davis, O.A., On macroeconomics: Comparative statics. In Mathematical Models in Economics, edited by M.O.L. Bacharach, M.A.H. Dempster and J.L. Enos, 1990 (Oxford University Press: Oxford). Available online at: ResearchGate.

- Dempster, M.A.H., Medova, E.A. and Roberts, J.F., Regulating complex derivatives: Can the opaque be made transparent? J. Bank. Regul., 2011, 12(4), 308–330. doi: 10.1057/jbr.2011.9

- Evans, M.K., Macroeconomic Activity: Theory, Forecasting and Control, 1969 (Harper & Row: New York).

- Grasselli, M.R., and Lipton, A., On the normality of negative interest rates. Rev. Keynes Econ., 2018, 6, to appear.

- Kindleberger, C.P., Manias, Panics and Crashes, 4th ed., 2000 (Wiley: New York).

- Krugman, P., Money: The brave new uncertainty of Mervyn King. The New York Review of Books, 14 July 2016.

- Lipton, A., Pentland, A.P. and Hardjono, T., Narrow banks and fiat-backed digital coins. J. Financ. Trans., 2018, 47, 101–116.

- Mundell, R.A., A theory of optimum currency areas. Am. Econ. Rev., 1961, 51(4), 657–665.

- Ritter, L.S. and Silber, W.L., Money, 1970 (Basic Books: New York).

- Simon, H.A., Models of Man: Social and Rational, 1957 (Wiley: New York).

- Spero, H., Money and Banking, 1953 (College Outline Series, Barnes & Noble: New York).

- de Spiegeleer, J., Höcht, S., Marquet, I. and Schoutens, W., CoCo bonds and implied CET1 volatility. Quant. Finance, 2017, 17(6), 813–824. doi: 10.1080/14697688.2016.1249019

- Turner, J.D., Banking in Crisis: The Rise and Fall of British Banking Stability, 1800 to the Present, 2014 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).