Abstract

From my studio on an island situated between an oil refinery and a port for export of crude oil, I see the terminals light up their flames in the dark. Myriads of lights make them look like a big city. The hugeness of these installations makes any art project seem small and insignificant. How can I express my concern with ecological issues? How are the changes the ‘oil-age’ has brought about, socially, mentally, environmentally, reflected in society? This paper explores some relations between people, place and print, and wood cut as political art.

Since the mid-nineties I have collaborated on exhibitions with my sister and colleague Caroline. Our shared project is to explore and develop the woodcut as a mode of expression, and to investigate different issues with woodcut as a medium. Our collaboration has a certain pattern. For each exhibition or other project, we agree on a conceptual framework, a shared issue, a certain format or a set of colours. The framework also provides scope for intuitive processes and images that are more visually than conceptually motivated. Then each of us works with her own pictures, in her own studio, before we meet after a while to view the results. This way we keep an element of chance and surprise.

Here I want to look at connections between prints and places in my work. There is a link between the choice of medium and the choice of domicile and lifestyle, but how is this linkage expressed?

I have two homes between which I have shuttled for many years. One is in the old Hansa city of Bergen, surrounded by seven mountains. The second is on a farm on the island of Radøy, where I have lived since graduating from the academy of art in Bergen, and where I have my studio. The island lies about a two-hour bus journey north of Bergen, with a flat, open landscape out towards the North Sea.

One of the differences between Bergen and Radøy is the weather, especially the strength of the wind.

On 10 January 2015, a severe storm hit the west coast and thousands of people were left without power. That weekend I was on Radøy. In storms, it often happens that the power fails for an hour or two, but this winter there have been more storms and longer power failures. The first thing I do when it happens is to look out the windows to check whether the power has also gone among the neighbours. Then I look across the fjord to an island in the southwest where there is an export harbour for crude oil. This is the ‘Sture Terminal’, where oil tankers are loaded with 300,000 tons almost daily. The terminal has five mountain caves for storage of oil with room for 6.3 million barrels. In the darkness, the area lights up like a medium-large Norwegian city, and the chimney where they burn off the residual gas – ‘the torch’ – towers high above the flat island. On that day the torch too was in darkness, a sign of serious problems. I lit candles, stoked up the wood-burning stoves, got out electric torches and the reading lamp from Ikea with a charged solar cell battery. Then it was just a matter of waiting, and hoping the power came back on, before the laptop and mobile phone batteries of the house ran out.

What is the attraction of the periphery?

With my starting point in Bergen, a consciousness of being in the periphery, geographically, linguistically and perhaps also mentally, is always present. The closest big cities such as Berlin become important reference points. The art field is urban and international, and the horror of becoming provincial and anachronistic if you don't keep up is an integral part of the small-town psyche. At the same time, there is a challenge in overcoming that horror.

When mobility is required it is tempting to stay where you are. The commercial fantasy of the free flow of manpower, goods and services has its parallel in contemporary art's burgeoning system of biennials and fairs with its related nomadic elite. Commuting between the cities and the countryside, and the differences and contrasts between these places, are something I use as material.

The peripheral and marginal are also present in the city. In the film Untitled (The City at Night), 2013, Ane Hjort GuttuFootnote1 explores the subversive potential of an anonymous artist's nocturnal wanderings in the city. We hear Guttu interviewing the artist, who after taking her art degree and working in a gallery has lost her faith in the art world. She withdraws from all professional art contexts and has devoted the last 20 years to drawing abstract renderings of events she has seen in the city at night. The city streets at night make up a world of their own, with different inhabitants and patterns of action from the daytime. The drawings are gathered in a large archive, but the artist has no intention of showing the works in public.

An artist who tells a quite different story of withdrawal is the Swede Andreas Eriksson.Footnote2 After some hectic years, he became hypersensitive to electricity and had to escape out to the countryside to reduce his exposure to power. He describes the experience of sitting inside his powerless dark house in the evening while the light from a passing car creates shadows that move from wall to wall. This became a series of paintings where the shadows are painted with an airbrush, as far as they are visible, black on black.

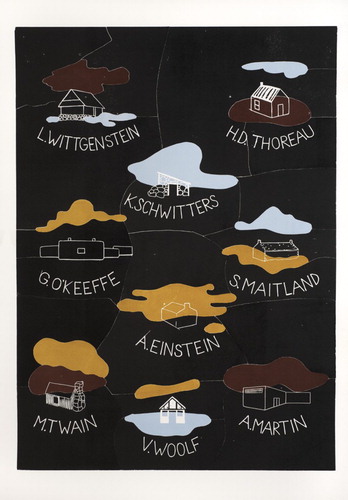

My woodcut The Hut is like a school wall chart of the houses of people who have deliberately chosen a life of withdrawal for long or short periods. It depicts a close association between the home and the personal creative activity going on there, in voluntary solitude or relative isolation. It shows, among other houses, Henry David Thoreau's hut from the experiment described in his book Walden, Ludwig Wittgenstein's hut that he built in Sogn and Fjordane in Norway, and Agnes Martin's house and studio in New Mexico.

Someone who is not in the picture, but who might well have been, is Hannah Ryggen.Footnote3 Her works inspired me during my training when I was looking for ‘foremothers’ in art. She moved from Sweden to a small farm on the Ørland coast outside Trondheim, where she lived with her husband and daughter. There she wove large-scale epic tapestries in home-dyed yarn with subjects related to political events and issues of the time. Her husband constructed her loom, and she used his urine to make her blue dyes. Utilising the natural limitations of the loom, which by necessity make angular shapes, Hanna Ryggen juxtaposed abstract, flat areas with figuration and text. In my woodcuts I explore something similar, the limitations of the technique, the relationship between flatness and space, simplification, text and storytelling.

When I began working with woodcuts during my training at the academy in the late eighties, this was not a popular technique – on the contrary the printmaking department was quite deserted. But this anachronistic and abandoned art exerted an attraction on me: painting was fun, but the brush seemed to slide far too easily across the canvas, with the possibility of changing and painting over endlessly. The wooden panel, on the other hand, offered plenty of resistance; I could hack, saw, carve, cut and no traces could be changed, no mistakes could be corrected.

The tools I use are fretsaw and woodcarving iron. Some shapes that are to have the same colour must be separated because of their size. The sizes of the pieces are determined by where I reach with the fretsaw. I try to saw where there are white spaces or lines, but I don't think it matters if the traces of the saw are visible. It was Edvard Munch who first began using this ‘jigsaw’ technique, where shapes that are to have different colours are sawn apart from one another, and the panel is pieced together before it is printed.

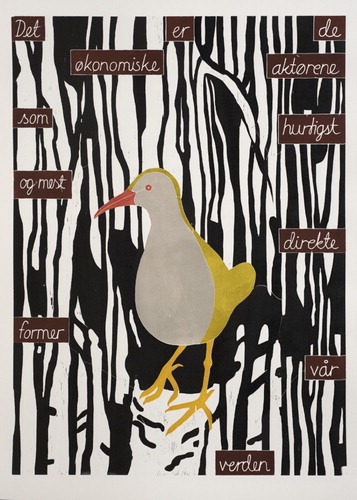

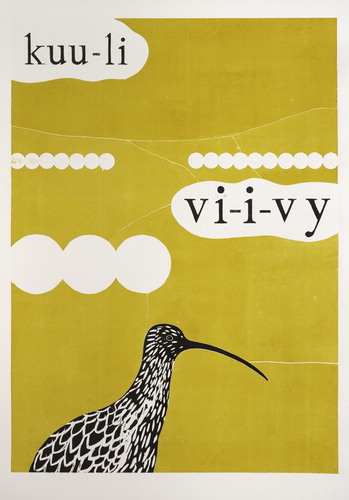

The woodcut Biotope is 90 × 125 cm – an impractically large format to transport from home to the large press in the city, but when I saw it up into pieces it works fine. This panel became 36 bits. The text in the picture is taken from a newspaper article during the financial crisis and says, ‘It is the economic actors who most quickly and directly shape our world’. There is a water rail at the centre. These birds come from the east in the autumn to rest or winter on the island. It is active in the twilight and at night, when you hear eerie pig-like grunts and screeches coming from the reeds. Another bird species whose habitat is affected by human activity is the curlew. Since it nests on the ground it is threatened by agriculture, as new harvesting methods mean that the mowing starts before the young have hatched. It migrates to the island from Britain and France for a short nesting season in summer. It returns to the same nesting place year after year, and it can have a long life, 30 years or more. Where I live on Radøy there has long been a nesting couple. I see them from my studio and listen to the melancholy screeches. In the picture From the Marsh, I have drawn the bird and the screeching as the bird book describes it. It shows the environment I share with the bird, specific, abstract and simplified, with the white round shapes of the silage bales ().

My first great love when it comes to art was the draughtsman Theodor Kittelsen.Footnote4 This was when I was five years old. His subjects, both recognisable and sinister, had a huge attraction for me. When I turned six and had learned to read I could read the titles of the pictures. That gave them a new power, and I read the titles again and again: The Black Death comes, The Black Death goes. The Black Death was always the same figure, an old woman with a black skirt, shawl and headscarf, carrying a rake. She came walking along by a row of shacks, or sat in the bows of a small rowing boat and leafed through a book, while the man who was rowing himself sat praying. In the picture entitled Mother, an old woman is coming, the person shouting is barely visible, but you see the log house where the child lives up on the hillside to which the black-clad old woman with the rake is on her way. In this case, the title did more than just describe the subject, it dramatised the situation further.

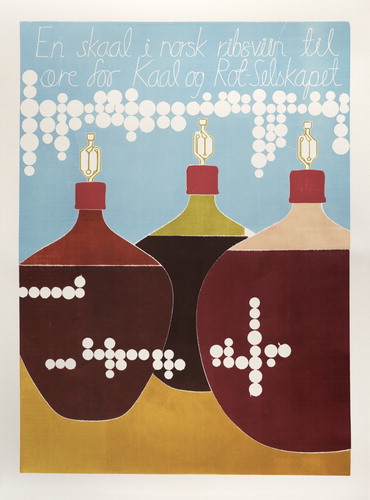

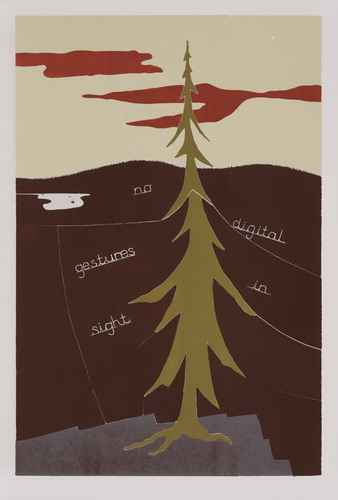

A recurring feature of the pictures is the tension between the visual and the textual language. The relative strengths should preferably be equal; so the written language won't take the upper hand and force the visual to become mere illustration. I use different languages – English, Norwegian and New Norwegian – and different ways of drawing the text from picture to picture. In From Wergeland's Notes the text is cut as old-fashioned looped cursive handwriting. The text says ‘A toast in red currant wine to the Cabbage and Tuber Society’ and is a quote from the poet Wergeland.Footnote5 One of his last projects before he died was to start the Cabbage and Tuber Society for the ‘spread of the cultivation of the most useful garden plants among the smallholder class’. In the minutes he wrote from the ‘meetings’ of the society, in a neat looped cursive hand, we can see that he was always the only person present, and that this was a dying man drinking his own health ().

As in the work with the curlew, I have tried to include sound, visualising the bubbling sound of making wine ().

Handwriting is like drawing; each individual has a distinctive expression. Hand-drawn printing fonts also assume a more individual and ‘drawn’ expression than stencilled types. You could say we are combining text and image, but that is only partially true. Text can be regarded as images, and shapes and figures can be regarded as text. Writing is a kind of drawing that involves an element of notation, says the anthropologist Ingold (Citation2007). He also writes ‘both drawing and writing are ways of telling by hand. There can be no picture, it could be argued, that cannot also be read, and no written text that cannot be looked at’ (Ingold Citation2013).

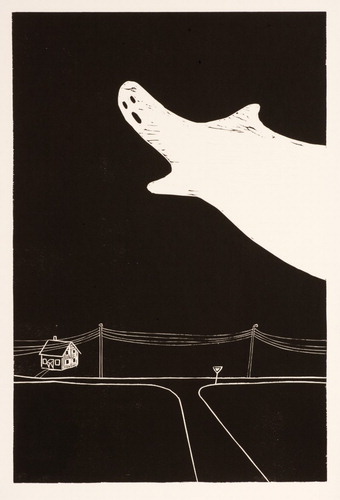

Printmaking is often called black magic, at least in Norwegian. Black magic, or necromancy, describes the custom of sitting on a burial mound to ask the dead, the demons, about the future, or about hidden aspects of existence. The Scottish writer Jamie (Citation2005) asks why darkness has become a metaphor for death, and she blames Christianity. We have become so preoccupied with avoiding the metaphorical darkness that we also remove as much as possible of the natural darkness ().

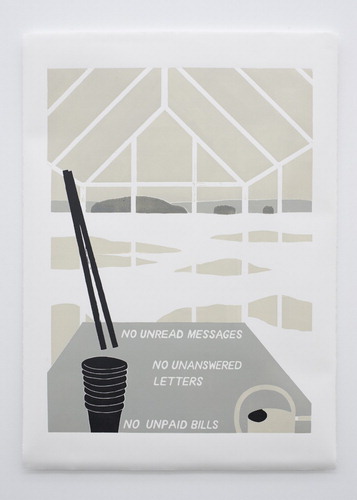

In the picture Torpor the greenhouse is shown in the winter along with the text ‘No unread messages, No unread letters, No unpaid bills’. The response I have had to this picture is that it may be about the dream of getting through the work pile, of gaining an overview, of control, and of at last relieving the stress, but that it may also be about the end times and death. Death is more present on the island than in the city. In Bergen I am blissfully padded and protected in a colourful, noisy environment. Something is happening all the time. On the island, on the other hand, it is silent; the changes are related to the seasons and natural processes, and the total indifference of nature become clear. Kittelsen tells a story where living in the wilderness is taken to extremes, where a solitary elderly couple are the only survivors in their area after the Black Death. The biggest problem, they think, is that they have lost their overview of the days and the calendar; they do not know when to celebrate Christmas. In the end, the old woman wanders off in deep snow to look for people. She comes to the next valley, but all the houses are empty. When she sits down to rest, she hears a voice – ‘Go home and bake bread, in ten days it will be Christmas’. The old woman goes home happy, for now she knows the season; she has heard it from the mountain itself ().

When the power fails it reminds me of my childhood, when we holidayed for weeks each summer in a hut on the mountain, without power and running water. We went for walks, gathered rock crystals, read and played cards by the light of smoky paraffin lamps. When it rained, the little living room was full of wet clothes hanging to dry; it was damp and cramped. The darkness was clearly present and the worst thing was having to go out to the outside privy in the evening.

It is said that between day and night there are three types of semi-darkness: civil twilight, nautical twilight and astronomical twilight. Twilight was the time when one could see the goblins. Now twilight has become the time when electric lighting goes on everywhere, but in old Norwegian tradition å holde skyming (to keep twilight) meant to sit and rest indoors without lights, until it became so dark that you needed light to see well enough to walk around.

In 1998 we got access to the Internet on the island, and the isolation in the periphery decreased as the World Wide Web unfolded. Now I can hardly imagine life without it, and how much I use it becomes clear when it fails.

On Radøy I walk between the house and the studio in the yard and look at the things I pass, and see whether I can find something I can use in a picture: a tractor, a lorry, old horse-carts, gas flasks for welding, an oil tank on a rack, a boat up for repairs, a blue plastic barrel, a home-made crab-boiler, a harrow, a silage fork, a broom. In the kitchen garden, the large stalks of last year's Brussels sprouts remain. In the greenhouse hang brown, dry and dusty tomato plants. In the ditch lie coils of cable.

Working with objects in space is another important part of our practice. In the exhibition Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,Footnote6 we staged a landscape where a variety of interests and life modes existed in parallel, and where the direction of the gaze or the way you look at things determines what you see. We took our point of departure in the American modernist poet Wallace Stevens’ poem with the same title as the exhibition, and the idea of the objective correlative.

In The Sacred Wood T.S. Eliot wrote; The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an ‘objective correlative’; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked. Eliot was discussing Shakespeare's Hamlet, and the theory in itself is not as interesting for us as the claim that this is the only way of expressing emotions in art.

Landscape as a genre stands strong in Norwegian art, associated with 19th-century National Romanticism and identity. Landscape can be considered aesthetically, but can also be read on the basis of the political and economic narratives we know. The farmers grow food in it, the environmentalists want to preserve it, the developers want to shape it, the real estate agents put a value on the view as a commodity that raises the price. The exhibition related to many of these themes in a stylised form.

My focus on the landscape of Radøy is not about returning to virgin nature, but is an artistic method for exploring the landscape as a cultural process. Pictures and installations are part of this transformation; printmaking becomes placemaking ().

Daylight time on the 10th January was six hours, and because of the storm it seemed even shorter. At four o'clock it was dark. After 24 hours without power and the Internet, our patience was over and we drove to the city. The car cast long beams of light out over the landscape. The lights had come on again at the Sture Terminal and the flame was lit. I thought of all the black oil in the mountain caves and the connections between weather, the collective oil gobbling of our society, and the great darkness. The picture Night on the Island comments on this. In the black surface, carving brings forth light ().

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Note on contributor

Annette Kierulf is Professor in Art with focus on Printmaking at Bergen Academy of Art and Design (KHiB). Her work ranges across a wide variety of media – from woodcuts, artist books to installation. Since graduating from Khib in 1992 she has worked as an artist, curator and writer, and lives in Bøvågen.

Notes

1. Ane Hjort Guttu, (b. 1971) artist, writer and curator living in Oslo. The film Untitled (The City at Night), 2013, was shown at the Bergen Assembly in 2013.

2. Andreas Eriksson, (b. 1975), artist living in Medelplana, Sweden.

3. Hannah Ryggen, (1894–1970) artist, some of her major works were shown at documenta13, 2012.

4. Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914) artist.

5. Henrik Wergeland, (1808–1845) poet, polemicist and linguist, and a pioneer in the development of modern Norwegian culture.

6. Shown at Hordaland Art Centre, Bergen, 2013.

References

- Ingold, Tim. 2007. Lines. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jamie, Kathleen. 2005. Findings. London: Sort of Books.