The essays in this issue investigate complex relationships between museums and the financial imperatives of the marketplace. Contributing to the journal’s aims of examining the social, economic, political, and cultural frames within which art practices function, authors debate shifting attitudes to the kinds of value that accrue to art in institutional environments that have become increasingly commercialized. As sponsorship deals and business interests shape the global footprint of museum ‘brands’ and determine the budget for exhibitions, new questions need to be posed about the social responsibilities of public art institutions, the extent of their independence, and the evolving narratives proposed by their collections. The increasingly powerful role of private collectors – many of whom now operate their own museums – is a factor that has precipitated further change to cultural landscapes around the world. As private individuals turn to the market to broaden their collections, the artists who are promoted by commercially motivated dealers and auction houses are inevitably those who find their way into the newest or most highly publicized exhibition spaces.

While the imbrication of artistic and economic interests can often lead to conflicts of interest in the museum world, cases discussed in the following essays also show how museums and commercial partners have turned to each other for mutual support in times of political upheaval and social change. In some circumstances, members of the art business sector have the flexibility to respond more swiftly and independently to changing cultural landscapes, and the owners of private museums enjoy the freedom to adopt adventurous collecting and exhibition strategies if they so choose (Bechtler and Imhof Citation2018a, 32, 38, 116, 178). In such cases, the balance between private taste and the responsibility for determining broader cultural narratives is finely poised. In this special issue, such entanglements are examined through the lens of cases drawn from Europe, North Africa, and the United States.

An important part of the following discussion concerns what museums are – or should be – and how they engage with audiences. As recent debate between members of the International Council of Museums shows, agreeing a museum definition is no simple matter (ICOM Citation2020). While the Council’s existing definition focuses primarily on the activities of acquiring, conserving, researching, communicating and exhibiting tangible and intangible heritage, the proposed new definition lays greater emphasis on museums’ commitments to practices of democracy, inclusivity, and critical dialogue. Efforts to foster ‘education, study and enjoyment’ give way to greater aspirations that entail museums’ contributions to ‘human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing’ (ICOM Citation2020). Although questions about the new definition remain open at the time of publication of the present volume, the terms of those discussions and the difficulty of achieving consensus among stakeholders are indicative of the challenges that museums face in identifying their distinctive social role, let alone in discharging it.

In the wake of cuts to state funding for the arts in many countries, public museums have become increasingly dependent on the financial support of dealers, private donors, and corporate patrons. While philanthropic giving is laudable (though often incentivized by tax breaks or determined by restrictions on the international movement of capital), it is fair to ask whether reliance on private money erodes the independence of public institutions and compromises their democratic accountability. Writing in January 2020 for The Art Newspaper, Anny Shaw examines some of the ways in which auction houses and gallerists become directly or indirectly involved in the decision-making of public institutions. In addition to informal connections to curators and museum directors that facilitate the exertion of co-optive or so-called ‘soft power’ (Nye Citation1990, 166; Zarobell Citation2017, 39), commercial partners influence public institutions through their presence in supporters’ circles; dealers propose and locate works they have sold to private collectors for temporary exhibitions; and gallerists both pitch ideas and lend works for exhibitions. Shaw concludes that for those in the private sector, ‘the benefits of sponsoring a show are manifold: institutional visibility, media coverage, an association with covetable artists and potential future business’ (Shaw Citation2020). In such cases, the exertion of private power may inhibit the ability of public institutions to experiment, innovate, and showcase the works of lesser known artists. As John Zarobell (Citation2017, 72–6) has argued, the situation is even starker in the case of so-called ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions held in cities outside Europe and the United States, many of which are organized by corporations (as opposed to the host art institution) that receive direct and indirect returns on their sponsorship.

When private collectors sit on museum councils and trustee boards, the potential for conflict of interest is even higher: individuals benefit from the museum exposure of artists whose works they collect, and board membership offers privileged access to the studios and latest work of contemporary artists. In a series of interviews that Bechtler and Imhof (Citation2018b) conducted with artists and museum professionals, a recurrent concern expressed by participants was the difficulty faced by museums in maintaining independence from private interests. Nicoletta Fiorucci, collector and founder of the Fiorucci Art Trust (London) summed up the problem:

For public museums it is really hard to be able to maintain a forward thinking, risk-taking profile, while also fulfilling the agendas inevitably set by their sponsors and funders. They have clear targets to meet, particularly in terms of audience numbers. On the contrary, private museums can afford to operate according to an individual’s own agenda. I think we will soon witness a dangerous imbalance between private and publicly run institutions and programs. (Bechtler and Imhof Citation2018b, 100)

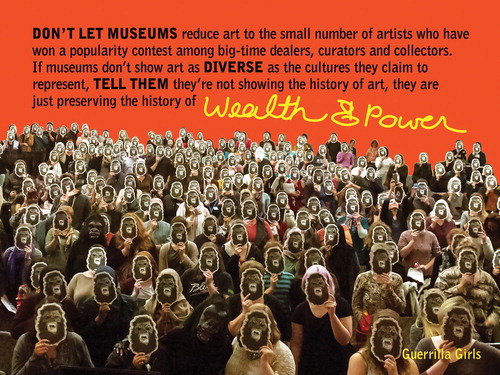

In 2016 The Guerrilla Girls undertook a project at the Whitechapel Gallery in London that explored a lack of diversity in European art organizations: ‘Guerilla Girls: Is it even worse in Europe’. A central visual element of the project was the collective’s History of Wealth & Power poster () that specifically questioned the extent to which museum collections have been – and continue to be – shaped by the tastes and interests of wealthy elites. Anticipating themes raised by the recently proposed ICOM museum definition and shining a light on histories of inequality in both museum collecting and the infrastructure of arts industries, the Guerrilla Girls stated:

With this project, we wanted to pose the question ‘Are museums today presenting a diverse history of contemporary art or the history of money and power?’ We focus on the understory, the subtext, the overlooked and the downright unfair. Art can’t be reduced to the small number of artists who have won a popularity contest among bigtime dealers, curators and collectors. Unless museums and Kunsthallen show art as diverse as the cultures they claim to represent, they’re not showing the history of art, they’re just preserving the history of wealth and power.Footnote1

It is important to keep in mind that intersections between museums and markets occur not just in acts of exhibiting and collecting, but also in sales. Deaccessioning has become an important topic of debate as museums increasingly turn to the market to finance their activities. This has important implications for ideas about the cultural and financial values that are ascribed to artworks as they move between different spheres. As Martin Gammon rightly points out, deaccessioning creates a situation where an object that has been ‘devalued in some fashion on the basis of some curatorial authority’ reemerges in the marketplace only to assert ‘a countervailing claim to aesthetic authority in a new context’ (Gammon Citation2018, 9). It is also a practice that reveals something about the kind of cultural narrative that the relevant institution wants to communicate to its audiences, specifically in cases where one or more works are sold for the purpose of developing strengths in another part of a collection.Footnote2

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, The Association of Art Museum Directors added a new aspect to this discussion when it passed a resolution enabling museums to ‘use the proceeds from deaccessioned art to pay for expenses associated with the direct care of collections’ regardless of when the art was deaccessioned (AAMD Citation2020). This moves away from the traditional – and more restrictive – approach to deaccessioning that approves the sale of works by a museum only in specific cases, including where the proceeds are used to ‘renew and improve its collections, in keeping with the collecting goals approved by the museum’s governing body’ (ICOM Citation2019). Departing from this idea, the AAMD’s new resolutions also allow museums to use the income (but not the principal) from funds generated by deaccessioning to cover the institution’s general operating expenses, once again regardless of when the relevant work or works were deaccessioned. The AAMD emphasizes that these measures are temporary, that museums need to be transparent in their approach to what constitutes ‘direct care’, and that it is not seeking to incentivize deaccessioning practices. At the time of writing, it remains to be seen how museums will interpret these rules. Important for the purposes of the present discussion is the increased access that museums now have to the market for the purpose of financing their operations. It will be interesting to see whether these policies will, in fact, revert to the pre-pandemic position or whether they mark a further shift in the conjoining of museums and markets.

It is not only the case that art markets have the power to impact on cultural conceptions of the museum or on the financial infrastructure of public art institutions. They also have repercussions on the shape of the urban environment. As more privately funded museums open in cities around the world, so too new landmarks in the urban landscape reflect the architectural preferences of individual, high net worth art collectors. As Karen van den Berg suggests ‘the twenty-first-century museum no longer poses as a guardian of cultural traditions, but rather as an iconic, hip and innovative destination – as though designed to be featured in the media’ (Citation2017, 187).

This is particularly the case for the relationship between private museums, tourism, and real estate businesses. At a 2016 press conference to announce plans for François Pinault’s refashioning of the historic Paris Bourse as a museum to house part of his private art collection, the city’s mayor Anne Hidalgo stated:

In the heart of Paris there is Les Halles with its cultural institutions, Beaubourg nearby, the Louvre, a collection of museums and places with cultural programmes, collectors. The heart of Paris is evolving and continues to attract with a brand that is the brand of art. (Beckrich et al. Citation2016)Footnote3

The contributors to this volume approach contemporary intersections between art markets and museums from a range of different perspectives. Alain Quemin writes from the field of the sociology of art and examines networks of influence and power that impact on relationships between public and private art institutions in France. Focusing first on an analysis of quantitative data derived from indices that show how the international art market projects an image of itself, Quemin examines ways in which high net worth collectors and commercial gallerists influence the decision-making of art professionals in the public sector. The increasing tendency of the latter to move between public and private sectors is identified as a further step in the erosion of differences between the two spheres.

Approaching the relationship between economic and aesthetic values from a different perspective, my own contribution to this issue asks whether a focus on the financial value of art encourages audiences to look ‘through’ art objects to their underlying economic worth. Bringing together art market data and concepts from analytic aesthetics, I debate whether art is becoming a form of fictitious capital that results in audiences’ loss of faith in the object’s intrinsic value (a form of ‘aesthetic atheism’). The increasing disappearance of artworks into financial products, freeports, and histories of capital has, I argue, implications for the way in which art is encountered in museums and, indeed, for conceptions of the role of the museum in society.

Christl Baur brings a curatorial perspective to bear on the relationship between art markets and museums and turns to the specific example of electronic artworks or ‘media art’. In her role as Head of the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, Austria, Baur has direct experience of the issues faced by media artists as they seek gallery representation and try to integrate their works into museum collections. Baur encourages readers to dispense with outmoded ideas about the difficulties of collecting and maintaining electronic art, but acknowledges that the challenges such works pose to traditional notions of ownership and conservation still persist. She explains how Ars Electronica has sought to position itself as a mediator between the market and museums by both exhibiting media art and encouraging debate among different stakeholders about ways in which to assess the financial and aesthetic value of works in this form.

The final three articles are devoted to case studies, each of which illuminates a different aspect of the intersection between museums and markets in specific geographies. Stephanie Dieckvoss offers a timely and insightful view of a new private museum in Marrakech, the Musée d’art contemporain africain Al Maaden. In addition to her discussion of the creation and collection of this new institution, Dieckvoss offers an important counter-narrative to typical discussions of private museums. Often understood as vanity projects, these institutions are strongly associated with the volatility of the art market on the grounds that their owners’ collections are constantly evolving. While Dieckvoss points out some of the social and political tensions that underpin the formation of the Musée d’art contemporain africain Al Maaden, she also shows how a museum like this can have an important impact on local audiences by showcasing African contemporary art and promoting regional narratives of creative production. From a broader perspective, the museum also has the potential to expand conceptions of African modernism and to bring the works of contemporary African artists to greater international attention.

Marina Maximova examines the rise of commercial galleries of contemporary art in Moscow during the 1990s. Like Dieckvoss, she offers a counter-narrative to any straightforward opposition between public and private spheres by highlighting ways in which commercial dealers filled an important gap in the Russian avant-garde art scene of the period. In the absence of state-funded museums for contemporary art, dealers created spaces and opportunities for artists to test ideas and to showcase works that departed from styles associated with Socialist Realism. Paradoxically, such dealers often set financial considerations aside when displaying and publicizing the artists whom they represented, thereby prompting a significant re-evaluation of the roles of private and public support for the arts.

Franziska Wilmsen’s contribution focuses on the intersection of art commissioning and institutional canon formation. By tracing the background and critical framing of Gerhard Richter’s work Eight Gray (2002), she shows how corporate and museum interests combine in ways that shaped the presentation and reception of the work. This commissioned piece was exhibited at the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin – a joint venture between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Deutsche Bank art collection. Of its nature, the work was positioned at the nexus of market and museum interests as it drew together public images of both Deutsche Bank and the Guggenheim Museum and communicated ideas about each institution to international audiences. Complementing this discussion, Wilmsen considers the extent to which Richter himself can be understood as a ‘brand’ – an artist with an instantly recognizable style and set of themes that, in this case, appealed to the public image of the commissioning institution.

In his book Art After Money, Money After Art, Max Haiven suggests that subscribing to the idea that there exists a difference between aesthetic and financial value is nothing other than the enjoyment of a comforting fiction, one designed to preserve the erroneous idea that art has ever been separated from money. As he puts it: ‘art cannot be corrupted by capitalism because it has always already been derivative of capitalism’ (Haiven Citation2018, 15). There are various presumptions in Haiven’s formulation, namely: that art is always produced for profit; that money is itself a corrupting force; and that financial and aesthetic values are inevitably in tension with each other. While the following essays show how cultural and economic goals can clash in ways that create specific problems for museums, artists, and audiences, the contributors to this issue also acknowledge the need to understand and analyze different approaches to funding and to the challenges that artists face when negotiating the marketplace. If museums are to exist and flourish within a market context, it is incumbent on us to devise strategies for their effective governance, financial stability, and democratic accountability to the diverse publics they serve.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Kathryn Brown is a lecturer in art history and visual culture at Loughborough University in the United Kingdom. Her books include Women Readers in French Painting 1870–1890 (Routledge, 2012), Matisse’s Poets: Critical Performance in the Artist’s Book (Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), Henri Matisse (forthcoming Reaktion) and as editor and contributor The Art Book Tradition in Twentieth-Century Europe (Routledge 2013), Interactive Contemporary Art: Participation in Practice (I.B.Tauris, 2014), Perspectives on Degas (Routledge, 2017) and Digital Humanities and Art History (Routledge, 2020). Brown has held visiting fellowships at Tulane University, the Australian National University, and the Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts in Washington DC. Her research has been supported by numerous awards, including most recently from the Terra Foundation for American Art. Brown is the series editor of Contextualizing Art Markets for Bloomsbury Academic.

Notes

1 Quoted in Whitechapel Gallery Press Release, Guerrilla Girls, Is it even worse in Europe? 1 October 2016 – 5 March 2017. https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/about/press/press-release-guerrilla-girls-is-it-even-worse-in-europe/ (Accessed 21 July 2020).

2 A recent example of this that sparked controversy was the decision taken by the Baltimore Museum of Art to undertake a deaccessioning program the purpose of acquiring works by artists who were underrepresented in its collection. For discussion see Halperin (Citation2018).

3 ‘Au coeur de Paris, il y a les Halles avec des établissements culturels, Beaubourg à proximité, le Louvre, un ensemble de musées et de lieux avec des programmations culturelles, des amateurs. Le coeur de Paris évolue et continue à attirer avec une marque qui est la marque de l’art’. English translations by the author. https://www.francetvinfo.fr/culture/arts-expos/francois-pinault-installe-sa-collection-a-paris-a-la-bourse-du-commerce_3279163.html. (Accessed 21 July 2020).

References

- AAMD (Association of Art Museum Directors). 2020. “AAMD Board of Trustees Approves Resolution to Provide Additional Financial Flexibility to Art Museums during Pandemic Crisis.” Press release. Accessed 17 July 2020. https://aamd.org/for-the-media/press-release/aamd-board-of-trustees-approves-resolution-to-provide-additional.

- Bechtler, Cristina, and Dora Imhof, eds. 2018a. The Private Museum of the Future. Zurich and Dijon: JRP Ringier and Les Presses du réel.

- Bechtler, Cristina, and Dora Imhof, eds. 2018b. Museum of the Future. Zurich and Dijon: JRP Ringier and Les Presses du réel.

- Beckrich, J., A. Jacquet, Y. Moine, and M. Laporte. 2016. “François Pinault installe sa collection à Paris, à la Bourse du commerce.” Franceinfo Culture, April 27. Accessed 14 July, 2020. https://www.francetvinfo.fr/culture/arts-expos/francois-pinault-installe-sa-collection-a-paris-a-la-bourse-du-commerce_3279163.html.

- De Oliveira, Nicholas. 2017. Privately Funded and Publically [sic] Minded: Art Institutions in Transition. London: Art Institutions of the 21st Century for Alaska Editions.

- Gammon, Martin. 2018. Deaccessioning and its Discontents: A Critical History. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Haiven, Max. 2018. Art After Money, Money after Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization. London and Toronto: Pluto Press and Between the Lines.

- Halperin, Julia. 2015. “Almost One Third of Solo Shows in US Museums go to Artists Represented by Five Galleries.” The Art Newspaper, April 2. Accessed 17 July 2020. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/almost-one-third-of-solo-shows-in-us-museums-go-to-artists-represented-by-five-galleries.

- Halperin, Julia. 2018. “Baltimore Museum is Selling Blue-chip Art to Buy Work by Underrepresented Artists.” Artnet.com, April 30. Accessed 20 July 2020. https://news.artnet.com/market/baltimore-museum-deaccession-1274996.

- ICOM (International Council of Museums). 2019. “ Guidelines on Deaccessioning of the International Council of Museums.” Accessed 21 July, 2020. https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/standards/.

- ICOM (International Council of Museums). 2020. “Museum Definition.” Accessed 17 July 2020. https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CA%20museum%20is%20a%20non,education%2C%20study%20and%20enjoyment.%E2%80%9D.

- McAndrew, Clare. 2020. The Art Market 2020. Basel: Art Basel and UBS.

- Michaud, Yves. 2020. Ceci n’est pas une tulipe: Art, luxe et enlaidissement des villes. Paris: Fayard.

- Montabonel, Sébastien, and Diana Vives. 2018. When Financial Products Shape Cultural Content. London: Art Institutions of the 21st Century for Alaska Press.

- Nye, Joseph S., Jr. 1990. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy 80 Autumn: 153–171. doi: 10.2307/1148580

- Shaw, Anny. 2020. “How Serious are the Dangers of Market Sponsorship of Museum Exhibitions.” The Art Newspaper, January 27. Accessed 13 August 2020. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/analysis/public-spaces-private-money.

- Van den Berg, Karen. 2017. “Museum Buildings in the 21st Century: Major Projects and Notes on the Redefinition of the Museum.” In New Museums: Intentions, Expectations, Challenges, edited by Katharina Beisiegel, exh. cat. Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 185–194. Munich: Hirmer.

- Zarobell, John. 2017. Art and the Global Economy. Oakland, CA: California University Press.