ABSTRACT

Engaging with Harun Farocki’s notion of the soft montage, our visual essay builds on our recent Seed, Image, Ground video project (2020). Commissioned by the Fotomuseum Winterthur, the moving image piece addresses the surfaces of vegetal growth in relation to the surfaces of media such as screens and images. While the video is a central reference point for this visual essay, our aim is not so much to theorise our own moving images and their juxtapositions and rhythms. Instead, in this article, we present a series of surfaces and scales that appear in and through the images. Images build upon images and this constitutes the practice-led approach in the temporal unfolding of the video. In other words, the video works as a temporal articulation of image surfaces across and upon living surfaces. Hence the central motif of the video essay and this accompanying text is to ask ‘what do images of growth look like?’ We also employ Celia Lury’s notion of ‘problem space’ to consider the methodological potential in the split-screen practice and its relation to Farocki’s soft montage.

1. Introduction

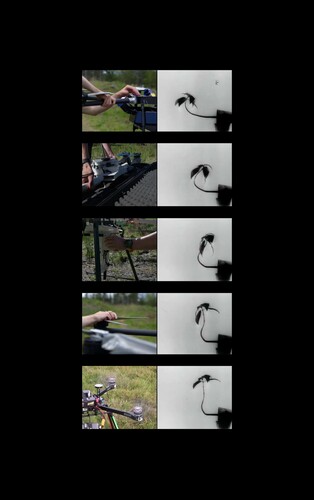

This essay builds on our recent Seed, Image, Ground video project (2020) and how it entangles with our larger research project on surfaces. Both address the surface of plants, agriculture and the biosphere in relation to the surfaces of media, such as screens and images. The video essay was commissioned by the Fotomuseum Winterthur in 2020 and it is openly available at the institution’s YouTube channel.Footnote1 While the video is a central reference point for this visual essay, our aim is not so much to theorise our own moving images and their juxtapositions and rhythms. Instead, in this article, we present a series of surfaces and scales that appear in and through the images. Images build upon images and this constitutes the practice-led approach to the temporal unfolding in the video. The video works as a temporal articulation of image surfaces across and upon living surfaces. In other words, we articulate the moving images as practices of surfaces, plants, and images: hence the central motif of the video essay and this accompanying text is to ask ‘what do images of growth look like?’ How do such images operate in two-channel video practice that builds on Harun Farocki’s work? Here, we do not refer only to operational images (Farocki Citation2004), but also to the idea of a ‘soft montage’ (Farocki Citation2009) which becomes a methodological reference point as one aspect of practice of images about and across images that can also be conceptualised as we do in this essay. The video and its relation to text are ecoaesthetic (Cubitt Citation2017) in the sense of dealing with the entanglement of media and environmental materials where the double articulation of images and green plant surfaces are the engine of our argument.

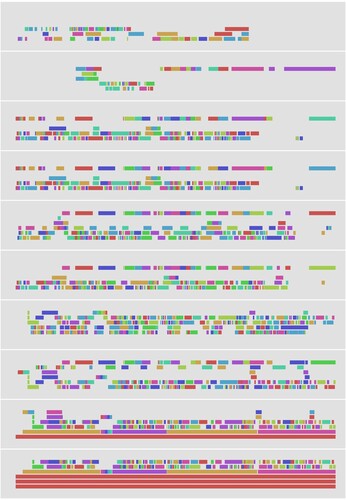

In this way, the video is a methodological exercise that helps to articulate a problem space (Lury Citation2021) – a space where problems, methods, and concepts are dynamically rearticulated, and where the space of their composition is not a stable container where a thing is addressed but part of their making: ‘a problem is not given but emerges with-in and out-with a myriad sequence of actions or methods that (trans)forms the problem space’ (Lury Citation2021, 6). This composition and this montage points to the ways methods are enacted only in the material practices that constitute the problem space as it unfolds as a living issue and tissue. Can this sequence Lury refers to be also a sequence of images? Could the actions be those of images? As the following visualisation () of the evolution of the timeline of our video essay show, the video’s timeline as a problem space presents its fabrication as a surface. The cuts, the movements of the sequences, and other editing operations manifested in the figure, call for a dynamic understanding of surface as surfacing, built on multiple genealogies of instrumentation, technology, and cultivation.

2. Operational

Seed, Image, Ground was commissioned for the Fotomuseum Winterthur’s Strike/Situations series of works. Harun Farocki’s cinematic installation works addressing ‘operational images’ were implied in the description of the commission programme, which focused on ‘the increasing entanglement of civil and military technology’, asking ‘What happens when photographic media are deployed operatively for the purposes of tracking (and tracing), identifying and monitoring individuals or controlling machines engaged in surveillance and military activities?’Footnote2

Our aim, though, was to divert from the strictest sense of ‘strike’ and move from the legacy of aerial images as dominantly military survey and targeting to their parallel uses: plant growth and planetary surfaces. As a visual art practice, we chose to rely only on existing images. From online archives and YouTube, from commercial seed bombing adverts to precision farming, historical footage of plant physiology and time-lapse images to data visualisation of growth, we assembled a range of surfaces that were tied together with the rhetoric of fabrication of images as fabrication of surfaces, and fabrication of movement as fabrication of growth. In other words, our problem space responded to Farocki’s (Citation2009, 71) note on the method of the double (projection) too, his own reflection upon seeing his Eye/Machine series on machine vision and operational images of war: ‘I was struck by the horizontal connection of meaning, the connection between productive force and destructive force’. This double-bind is also a core aesthetic and epistemic theme with Farocki, or as Pantenburg (Citation2016, 54) argues, ‘If we try to pinpoint one recurring interest that has preoccupied Farocki both in his filmmaking and his theoretical efforts, it is the question of comparing images’. As we will emphasise later on in this article, besides an articulation of techniques of weaponry and techniques of growth as a comparison in epistemic terms, we point to the emphasis on the horizontal too: to fabricate surfaces upon which those operations take place.

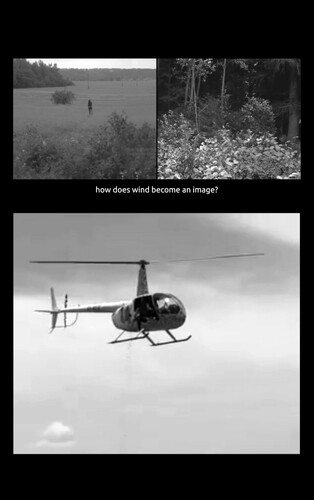

In Seed, Image, Ground, the sound design by María Andueza Olmedo takes over the scene even before images appear. While their movement across the screen split-screen space is the central rhythmic element, the sound has its own narrative and non-narrative qualities. The remediation of the mechanical airlift of the helicopter rotors sets the backdrop of the cinematic 1970s. The whirling trope familiar from Apocalypse Now (1979) is replaced into this other 1970 cinematic manoeuvre of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975) where the mystical wind that blows across the crop fields is created by the helicopter, carefully placed behind the camera. This sound speaks to a periodisation of media archaeological combination of cinema and war (Virilio Citation1989) which is in the pace of the opening moments, though, quickly replaced with the whirling rotation of a seedling. This, then, provides a disjunction between operations of war and growth. Hence, the opening question of the voice over ‘how do you fabricate wind’ is not about a poetic metaphysics, but one of the specific situations of cultural techniques (Siegert Citation2015) of environmental management, to put it into administrative language. More than a question it is an expression of a problem, or even more accurately with Lury: it composes a problem in the methodological arrangement of images across and on surfaces ().

The video picks up on seed bombing as a motif that relates to specific techniques of enhancement of plant growth and reforesting. Seed bombing ranges in scale; most often it is discussed as a DIY technique for seeding derelict or hard to reach land and ground. But it is also something that features in histories, plans, and some actual projects of reforestation. The military history of the idea emerges from former RAF pilot Jack Walters’ proposals and already 20 years ago it was developed as a commercial idea by Aerial Forestation Inc. premising its large-scale viability on ‘Equipment installed in the huge C-130 transport aircraft used by the military for laying carpets of landmines across combat zones has been adapted to deposit the trees in remote areas including parts of Scotland’ (Brown Citation1999). What’s interesting is the relation between aerial power – and military logistics – as it is related to environmental techniques; the superiority of the aerial view as it has been outlined and the complexity of techniques that go into enabling this view.

As Paul Saint Amour (Citation2013) argues in his take on aerial imaging during the First World War and the subsequent years, a complex set of arrangements and ways of seeing as ways of knowing – a bundle of interrelated operations – enabled the ‘planimetric view’s construction from a diachronic series of images and moments’. In short, one does not simply view from above, but it involved in those military operations a complex composition of scales, speeds, viewpoints and other forms of ‘applied modernism’ (Saint Amour Citation2013) that worked through the figure of the photomosaic surface. The multiple shots taken were temporally and dynamically out of sync because of the different speeds of aeroplanes doing the imaging; hence the different scales needed to be operationally synchronised. Such techniques of making surfaces had also an impact on post-war territorial management. Indeed, the beauty of their applicability was to offer the illusion of simultaneity of areas of a territory stitched together into one surface where military techniques fed into different forms of aerially driven bureaucracy and design, such as urban planning. Fabricating surfaces became thus one key format of truth established through aesthetic crafts, photography, and technologies of ascent ():

A photographic form that revealed camouflage had itself been camouflaged, its contingencies disguised or levelled so that it resembled an idealised schematic as seen by a disembodied observer. Canonised by intelligence personnel, surveyors, police, entrepreneurs and city planners as the utmost in photographic realism, the mosaic was considered ‘accurate’ only in proportion as it bent the rules of optics away from perception toward orthogeny. (Saint Amour Citation2013, 133)

Plant growth modelled as an image.

Growth/transformation expressed in moving images.

Territorial management as one of imaging: growth and management of territories as images and data come together.

We are currently writing a book on the question of surface as it emerges in the interplay between vegetal surfaces and screen surfaces. That work dips in more detail into some historical scenes of nineteenth-century plant physiology and the use of images and apparatuses in laboratory practices. Besides working with science studies inspired methods with historical material, we extend the question of the plant surface into different scales: the definition of what is growth, and how images are incorporated into an understanding of growth – photographic images and diagrams, and the also historical and more recent techniques of ‘time-lapse’ with cinematic techniques entering the scene around fin-de-siecle; and how in more recent terms this is taken further with techniques of large-scale datasets but also making territories into data manageable images such as in precision farming as just mentioned.

The operational image has come to refer to images that do not primarily represent but are part of an operation (Farocki Citation2004); industrial and scientific images, images that function in systems, images that are for navigation and guidance or measurement, for example. Machine vision and AI is where the term has recently mushroomed. We, however, extend the use of the term, in order to: firstly, to engage with the operationalisation of processes of light as they measure plants and become part of the epistemic operation (epistemic with very close goals related to industry and agriculture) and secondly, operationalising also large-scale areas like farming areas as part of data-driven operations, reminding of a crucial theme often ignored in media and other research: infrastructures of urbanism extend to rural areas too including AI, blockchain, and other techniques dealing with datasets consisting of biological organisms and ecological areas such as in plantations and farming (see Wang Citation2020).

In our visual essay, we also shift gradually from the operational sphere of the military to a constellation of images that speak of images: in Farocki’s terms a soft montage as a method of speculative surfacing. This surfacing is both a visual theme but it pertains to what we consider a central element of the articulating links that are being created, also then shifting the term soft montage to the question of temporal problem space(s).

3. A soft montage

Our images are found images; the video essay does not include any sequence filmed by ourselves. They are sourced from multiple uses: from commercial material, promotional, casual footage and less casual projects. But the project is not an archival project – that would stretch the term archive too far. It is a montage project, a project of problematics and composition. Removed from their original arrangement, yet not erasing all of their contexts, for us, the images are compiled and arranged into a split-screen space where, echoing Blümlinger on Farocki’s multiscreen projections, ‘the organisation of images appears much more important than the method used to record or generate them’ (Citation2008, 276).

As per our earlier note about the ecoaesthetic, the split screen is for the double articulation of image and landscape, image and territory. ‘Multiple images and visual contexts created independently of one another collide here’, in Blümlinger’s (Citation2008, 277) words again. She continues: ‘the recorded images intersect and reflect one another’ (Blümlinger’s Citation2008). Technical images in plant physiology and agricultural management (including soil maps and other specialist techniques of early data visualisation) constitute one reference point for the epistemological function of what images do in scientific practices. Such images are, we argue, not only ways to mark and measure and thus understand the enhanced ways of cultivation of growth, but they are also operational images as they prescribe a particular role still to images.

Split screen is however always more than two as it has its own force of synthesis as well as rhythm. History of cinema and video is one continuing experiment on this from Dziga Vertov’s fragmented visual space of superimposition to many later examples of multiscreen projection formats (Beck and Bishop Citation2020). One can even speak of videographic cinema (Rosenkrantz Citation2020). Farocki (Citation2009, 74) also refers to this lineage and such a practice of assembly through his notion of soft montage: ‘A montage must hold together with invisible forces the things that would otherwise become muddled’. For Farocki, this thought continues in relation to his works on technologies of war, implying that montage is a method of articulating media archaeological continuities and discontinuities:

Is war technology still the forerunner of civil technology, such as radar, ultra short-wave, computer, stereo sound, jet planes? And if so, must there be further wars so that advances in technology continue, or would the simulated wars produced in laboratories suffice? (Farocki Citation2009, 74)

Farocki (Citation2009, 70) continues on the double, clarifying also our approach to soft montage as a method about the synthesis of surfaces as surfacing:

There is succession as well as simultaneity in a double projection, the relationship of an image to the one that follows as well as the one beside it; a relationship to the preceding as well as to the concurrent one. Imagine three double bonds jumping back and forth between the six carbon atoms of a benzene ring; I envisage the same ambiguity in the relationship of an element in an image track to the one succeeding or accompanying it.

Farocki does not offer a clear definition of soft montage. Clarifying the stakes of the soft montage, Nora Alter (Citation2015, 151) proposes that it is more about a ‘general relatedness of images, rather than a strict equation of opposition produced by a linear montage of sharp cuts’. Alter emphasises that the soft montage differs from the more famous Eisenstein version and is defined by ‘a logic of difference’. Alter (Citation2015, 152) continues: ‘In this regard the cut of soft montage is synonymous with the conjunction ‘and’, as multiple images are folded onto one another within the same spatial field, creating new configurations’.Footnote3 Alter’s definition of soft montage points out that it can be read in proximity to an emphasis found in Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy: the conjunctive and of the assemblage concerns the multiplication of difference, which still creates a field of resonances and thus it also creates a field of problematics; we can identify shots and reverse-shots, but they also become speculative as they bypass narrative forms of historical time.

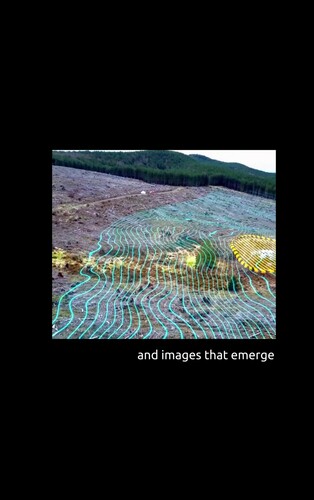

Our work is also an assembly in this particular sense that nods to the historical archives as well as contemporary images. There is no simple causality that the images would express in what force impacts which thing, what surface becomes operative and which surface becomes data. That would be too crude of an assumption. Instead, the scenes relate to a series of images that form and formulate surfaces. When we are interested in the question of the plant and territorial surface, we engage through the image surface. When we are dealing with image (media) surface, it leads us to ask how are they modelled, which material base and reference is apt when considering the contemporary ecoaesthetic situation. The images, thus, investigate surface inscriptions ().

4. Vegetal filmmaking

The aerial view is likely to be a central part in the repertoire of techniques of air, but it also includes the idea of a large-scale territorial planning, measurement, and survey. It is through making the territory into an image that a particular operationalisation also for growth becomes possible. As images that define or focus on space, we juxtapose different sets, contexts and archival sources: laboratory images of growth; a set of scientific procedures and images that are instrumental in such operations of measurement of plants since nineteenth-century plant physiology; seed bombing and regreening surfaces of growth; and precision agriculture that visualises the surface anew based on processed data relations, even AI techniques, representing what we coin ‘platform ruralism’: a mode of management of large-scale growth surfaces through an agglomeration and processing of data on corporate and other platforms that then feed back onto the surface as agricultural operations whether mechanical or chemical. Platform urbanism (Barns Citation2019) has come to refer to such data platforms of circulation of gathering, circulation, and analysis of data in smart cities, but this extends it to non-human living contexts of plants and growth: a variety of data-points that do not refer to the usual sphere of media in urban consumer use, but to its long back trail in rural lands and environmental conditions.

Writing about the use of multiple projections in the turn of the twenty-first-century video art, Liz Kotz argues that ‘images find their natural home in the emerging world of ‘information architecture’, in which every building functions as a kind of image and every built surface promises to contain some type of networked display’ (Citation2008, 383). While the argument typically assumes the surfaces of the architectural building or the urban space, as in Giuliana Bruno’s landmark work (Citation2014), in Seed, Image, Ground we extend this particular interweaving to other built environments such as those in aerial reforestation, landscape restoration, and agriculture. Building on Kotz (Citation2008), here every vegetal surface would function as a kind of image and every landscape would promise to behave as a networked screen.

‘The future of the movies,’ said Abel Gance, ‘is a sun in each image’ . (Bozak Citation2011, 34)

Hence, we articulate the series of surfaces as series of image problems:

Territorial surfaces, and plant surfaces.

Plant surfaces, and agricultural surfaces.

Surveys, landscapes, and data surfaces.

As problem spaces, these surface spaces compose each other. The sequences and actions of images form a topology of the problem at hand: what is a surface, how is seed bombing a surface operation, and how do images feature in this rethinking of the territory both from above and as data. Lury’s (Citation2021) methodological argument then becomes one reference point for our work while the composition of images and the composition of discursive concepts are part of this work of soft montage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jussi Parikka

Dr Jussi Parikka is a Professor of Technological Culture and Aesthetics at the University of Southampton and Visiting Professor at FAMU at the Academy of Performing Arts, Prague. At FAMU, he leads the Operational Images and Visual Culture project (2019–2023) funded by the Czech Science Foundation. He has published widely on media ecology and media archaeology including Digital Contagions (2nd edition in 2016), Insect Media (2010), and A Geology of Media (2015). Recent publications include the co-edited volume Photography Off the Scale (2021, with Tomáš Dvořák) and the forthcoming co-authored book The Lab Book: Situated Practices in Media Studies (2021, with Darren Wershler and Lori Emerson).

Abelardo Gil-Fournier

Dr Abelardo Gil-Fournier is an artist researching at FAMU Prague for the project Operational Images and Visual Culture. His practice has been shown and discussed internationally, including Transmediale, Fotomuseum Winterthur, MUSAC, LeBal Paris, Strelka Institute, Medialab Prado, Fotocolectania as well as Cultural Centers of Spain in Mexico, Nicaragua and El Salvador. He is a member of AMT Archaeologies of Media and Technology (Winchester School of Art) and a part-time instructor at the European University of Madrid. http://abelardogfournier.org

Notes

1 The url to access to it is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMgijwDyq88 (accessed March 24, 2021).

2 See the webpage ‘Strike’ at https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/cluster/24/ (last accessed April 6 2021).

3 This relates to Helga Lutz’s research project in Germany that identifies elements of the double and the comparative as a media technique. ‘Media Dispositifs of Comparison: Harun Farocki's comparative practices in the context of media history’ project description online at uni-bielefeld.de/(en)/sfb1288/projekte/c05.html. See also Pantenburg (Citation2016).

References

- Alter, Nora. 2015. “Two or Three Things I Know About Harun Farocki.” October 151. Winter 2015: 151–158.

- Barns, Sarah. 2019. Platform Urbanism: Negotiating Platform Ecosystems in Connected Cities. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Beck, John, and Ryan Bishop. 2020. Technocrats of the Imagination: Art, Technology, and the Military-Industrial Avant-Garde. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Blümlinger, Christa. 2008. “The Art of the Possible: Notes About Some Installations by Harun Farocki.” In Art and the Moving Image: A Critical Reader, edited by Tanya Leighton, 273–282. London, New York: Tate Publishing.

- Bozak, Nadia. 2011. The Cinematic Footprint: Lights, Camera, Natural Resources. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Brown, Paul. 1999. Aerial bombardment to reforest the earth. The Guardian, 2 September.

- Bruno, Giuliana. 2014. Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Cubitt, Sean. 2017. Finite Media. Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Elsaesser, Thomas. 2017. “Simulation and the Labour of Invisibility: Harun Farocki’s Life Manuals.” Animation 12 (3): 214–229.

- Farocki, Harun. 2004. “Phantom Images.” Public 29: 12–24.

- Farocki, Harun. 2009. “Cross Influence/Soft Montage.” In Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom?, edited by Antje Ehmann, and Kodwo Eshun, 69–74. London: Raven Row & Koenig Books.

- Kittler, Friedrich. 2013. “Rock Music: A Misuse of Military Equipment.” In The Truth of the Technological World. Essays on the Genealogy of Presence, translated by Erik Butler, 152–164. Redwood, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Kotz, Liz. 2008. “Video Projection: The Space Between Screens in Art and the Moving Image.” In Art and the Moving Image: A Critical Reader, edited by Tanya Leighton, 371–385. London, New York: Tate Publishing.

- Lury, Celia. 2021. Problem Spaces. How and Why Methodology Matters. Cambridge: Polity.

- Pantenburg, Volker. 2016. “Working Images: Harun Farocki and the Operational Image.” In Image Operations: Visual Media and Political Conflict, edited by Jens Eder and Charlotte Klonk, 49–62. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Parikka, Jussi. 2012. What is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity.

- Rosenkrantz, Jonathan. 2020. Videographic Cinema. London: Bloomsbury.

- Saint Amour, Paul. K. 2013. “Photomosaics. Mapping the Front, Mapping the City.” In From Above: War, Violence and Verticality, edited by Peter Adey, Mark Whitehead and Alison J. Williams, 119–142. London: Hurst.

- Siegert, Bernhard. 2015. Cultural Techniques. Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real. Translated and edited by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Uhlin, Graig. 2015. “Plant-Thinking with Film: Reed, Branch, Flower.” In The Green Thread: Dialogues with the Vegetal World, edited by Patrícia Vieira, Monica Gagliano and John Ryan, 201–217. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Virilio, Paul. 1989. War and Cinema. Translated and edited by Patrick Camiller. London: Verso.

- Wang, Xiaowei. 2020. Blockchain Chicken Farm. New York: FSG Originals/Logic.