ABSTRACT

This article provides an account of the practice PhD in art and the nature of the debates surrounding its development and status. Primarily, the article is aimed at prospective and current PhD candidates (as well as supervisors), offering a critical approach to shaping and championing practice research. In helping to define the practice PhD, the article distinguishes between projects and practice and provides a reference to key debates. A catalogue of articles from Journal of Visual Art Practice is included in an appendix as part of wider encouragement for candidates to be critically informed about practice research and to help develop a literature review. The article ends with 8 practical steps for pursuing the practice PhD.

What is a PhD? It is not the Nobel Prize. It is not a professorship. It is the last stage of studentship, no more and no less. […] This kind of advanced degree is designed to set people off on a professional path. It is a beginning rather than an end; a set of driving lessons before you can take the car out by yourself. (Morgan Citation2001, 6)

A doctor’s degree historically was a licence to teach – meaning to teach in a university as a member of faculty. Nowadays this does not mean that becoming a lecturer is the only reason for taking a doctorate […] The concept stems, though, from the need for a faculty member to be an authority, in full command of the subject right up to the boundaries of current knowledge, and able to extend them. (Phillips and Pugh Citation2006, 20)

The materials provided here are situated within the context and archive of the Journal of Visual Art Practice, but also, as appropriate, provide wider reference points (without claims, however, to being fully comprehensive, which would surely be a Sisyphean task). The field of the practice PhD has had many twists and turns (Miles Citation2004; Schwarzenbach and Hackett Citation2016). As Elkins’ (Citation2014) global survey shows, formats, histories, ethos and expectations vary enormously around the world, and indeed we might suggest even within departments (with colleagues often approaching supervision and examination is quite different ways). In short, there remains a lot of debate and difference around the practice PhD. Nonetheless, what holds is that the Art PhD is a firm fixture within the educational setting and students undertaking this qualification would do well to reflect upon its parameters – not merely to fulfil a remit, but rather to take confidence when articulating their work in what is in fact a relatively ‘open system’ of knowledge and examination. Or, put another way, as the Journal of Visual Art Practice celebrates its twentieth year, two decades on from Sally Morgan’s cogent and pragmatic account of the ‘new’ terminal degree in art, it is pertinent to set out an ‘approach’ to the practice PhD that is not dogmatic, nor defensive, but rather informed; that allows for a discursive, deliberative space. It is pertinent the artist as a ‘doctor of philosophy’ can take up a position and stand up for methodologies that are specific to the field and that contribute to the wider production, circulations and contestations of knowledge.

First things first

To return to the question of just what a PhD is, we can add that it is a major undertaking. In the UK, for example, the candidature for a full-time PhD student is three years, and very often students request an additional fourth year for ‘writing up’. For part-time students, the PhD is likely to take between five and six years. Inevitably, then, it is important to genuinely want to commit to this level and duration of study, rather than simply feel it is necessary for one reason or another. It is crucial to be sufficiently motivated to explore a specific research topic, and that the topic is one that will sustain one’s interest.

Eco (Citation2015, 7–8) sets out four ‘obvious rules’ for choosing a research topic:

The topic should reflect your previous studies and experience.

The necessary sources should be materially accessible.

The necessary sources should be manageable.

You should have some experience with the methodological framework that you will use in the thesis.

The fourth rule can often prove a stumbling block for the artist applying for PhD. Not because they are lacking a framework (quite the contrary), but the ‘myth’ of the PhD as something that is purely about empirical data gathering and writing can often lead prospective students to make all sorts of accommodations and compromises. As Morgan (Citation2001, 6) notes, in the humanities, ‘publishability’ has often been seen as the ‘paramount objective’ of the PhD. Later, this criteria was nuanced as the need for the PhD to demonstrate an original contribution to knowledge. Of course, as Morgan adds, ‘[o]ne might argue that this is an inevitable outcome of the goal of publishing, since it would be unlikely that anyone would want to put anything into print that simply went over old ground’.

As an affordance of the ‘publishability’ criteria, and more generally the need to make an original contribution, it is not uncommon for a highly competent sculptor or print-maker, for example, to submit a research proposal that includes interviewing artists and gallery visitors, presented as if somehow a means of justifying any art making that might take place during the PhD. Yet, in accordance with Eco’s obvious rules, such approaches do not represent methods and methodologies previously studied – these are not part of the methodological framework of the artist. These are more likely the purview of a sociology of art, museology and/or education. So, what, then, as Morgan (Citation2001, 7) asks, should be the equivalent in the world of the visual arts? ‘It might be argued’, she suggests, ‘that the equivalent of publishability is, in fine arts’ case, exhibitability. This isn’t too revolutionary a thought; in the terms of the Government’s Research Assessment Exercise, exhibiting is already the recognised equivalent to publishing’.

To reiterate, Morgan, is setting out her thoughts on the practice PhD over two decades ago. She is right that the UK Government’s national research auditing formally recognized art practices as part of the research landscape, but it is worth noting that related debates and indeed a persistent view that somehow art is not fully understood or afforded equivalent status as research is far from uncommon.Footnote1 It is instructive to read further from Morgan’s account:

The terminal degree of a subject should reflect the professional aims of that subject, and as yet fine art does not seem to have resolved that issue. Most fine art PhDs are strange, dislocated things being done by artists, but being judged by scholars from other disciplines. One consequence of this is that the tasks set are not clear nor, perhaps, are they appropriate. Many students are being asked to do two equally enormous tasks, i.e. make exhibitable artwork and write a publishable dissertation. In one extreme case a student was cited in the Guardian newspaper (12 September 1998) as having spent nine years on her PhD, producing frescoes, an exhibition, and a 100,000-word dissertation. I believe that such research overkill is a symptom of a lack of confidence in the face of a scholarly establishment that assumes (out of habit) an empirical model of knowledge for all subjects. It is also a symptom of a lack of clarity about the status of the artwork, which is, I will argue, not a piece of preliminary fieldwork nor an experiment done in controlled conditions, but an intelligently constructed text that embodies meaning and knowledge. (Morgan Citation2001, 7)

Nonetheless, the symptom of a ‘lack of clarity’ about the art practice of the practice PhD remains and can prove debilitating for an Art PhD student. There are two important responses to this problem. Firstly, it is useful to remind of the actual criteria of the PhD. Doctoral programmes, regardless of subject, often sit someway between the regulations around taught programmes at a given institution, and the broader ‘research environment’, which is more staff facing. Sometimes PhD students are squarely defined as students, other times as colleagues. The different positionality can occur within a single department, shifting according to different needs or processes of the School. As a result, it can often happen that a student enters into their PhD viva without ever really having examined and interrogated the ‘learning outcomes’ or criteria of the PhD. As quasi-members of staff they might simply have been working on their research, and working according to all sorts of unspoken assumption about what a final thesis ‘looks like’ and comprises. This problem, however, can be easily solved by simply reflecting on the criteria. (The second response, followed up in the next section, is to consider more deeply how art practice can be understood as a methodological framework.)

The following is typical of the wording used in procedural documents across the higher education sector, internationally. For the award of PhD, research students must demonstrate:

the creation and interpretation of new knowledge through original research or other advanced scholarship, or of a quality to satisfy peer review, extend the forefront of the discipline and merit publication;

a systematic acquisition and understanding of a substantial body of knowledge which is at the forefront of an academic discipline or an area of professional practice;

the general ability to conceptualize, design and implement a project for the generation of new knowledge, applications or understanding at the forefront of the discipline, and to adjust the project design in the light of unforeseen problems;

a detailed understanding of applicable techniques for research and advanced academic enquiry.

The last two points relate to generic skills to effectively undertake research. Usually, a university will provide centralized training and support to help develop the relevant understanding and methods. Of course, PhD Supervision attends (or should attend) to these matters as an ongoing consideration. However, it is really the first two points that need to be clearly demonstrated and signed off by external examiners (through the thesis submission and accompanying viva process). It makes sense to view these two criteria as intimately interrelated, and as defining of a chosen topic as research.

Following again Eco’s ‘obvious rules’ there are genuine practical considerations regarding whether or not research materials and processes are materially accessible and manageable. It is crucial to establish achievable research objectives, but also it is important that a research project is coherent and ‘situated’ within a field of knowledge. It is common, of course, for research to be interdisciplinary (and this in turn can often be a means to identifying originality), but it is still important to establish reasonable and manageable boundaries. Even cross-cutting research needs to pertain to methodological frameworks, and for the researcher to be sufficiently competent in the relevant methods (or at least to be able to acquire sufficient competency through the process of developing the research). What is vital is an appropriate balance, and this can be understood through the requirement to create (or interpret) new knowledge and to demonstrate a systematic understanding of a body of knowledge or field of enquiry.

In its broadest sense, the ‘field’ of study for the artist is simply ‘art’ – and this will include aspects of art history and theory, as well as an understanding of the practice and process of art (Elkins Citation2001). Of course, the artist, not least the contemporary artist, will likely be engaged in all number of ‘other’ concerns, relating perhaps to the sciences, the environment, culture, identity, and technology. But for the purposes of the PhD it is necessary to be clear in which body of knowledge the researcher is demonstrating systematic acquisition and understanding. In which field are you seeking your licence to teach/research? This may indeed involve some cross-cutting areas, but overall it must be realistic (what can be reasonably covered in three years?). The primary or ‘home’ field of knowledge should reflect previous studies and experience. Again, for the artist this will generally be art itself – and indeed, not just art, which itself is a broad area of knowledge, but a specific aspect or ‘field’ within art. In turn, by being clear about the field of research it becomes possible (reasonable) to identify what sorts of new contributions can be made.

The interrelatedness of the new contribution to knowledge and its demonstration within a systematic acquisition and understanding of a substantial body of knowledge underpins all PhDs – furthermore, it is the examination of these two main considerations that makes for a doctorate. To avoid any ‘thesis neurosis’ and/or delusions of grandeur, it is always worth reminding of the fact that the PhD is a very specific genre – it is not a book, it is not an exhibition, it is not a ‘life’s work’ (… ‘[i]t is not the Nobel Prize. It is not a professorship. It is the last stage of studentship, no more and no less’): the PhD is an examination, a report on knowledge, no more and no less. It is also worth remembering that it is a genre that allows for tremendous flexibility. It is an ‘open system’ that works ably across all subject areas, and not least because it is, in the end, examined by peers; albeit senior experts, but experts within one’s own field. Again, this is why it is important to be clear about what that field is; this is how the researcher is examined, and also this is the place they then uphold.

Practice before projects

One way of helping to define and refine your situating within a field of knowledge is to be able to understand and communicate your work in terms of a practice. We can begin with a form of dictionary definition:

Practice [‘praktɪs] trans. To test experimentally, to put to the test; n. the actual application or use of an idea, belief, or method, as opposed to theories relating to it; v. to perform an activity or exercise a skill repeatedly or regularly in order to acquire, improve or maintain proficiency. ORIGIN late Middle English to mean ‘a way of doing something, method; practice, custom, usage’; also ‘an applied science’ (late 14th Century); similarly from the Old French of practique to mean ‘practice, usage’ (13th Century) and directly from the Medieval Latin practica, meaning ‘practice, practical knowledge’; with the underlying root from the Greek praktike to mean ‘practical’ as opposed to ‘theoretical’. Yet, equally, practice encompasses understanding, relating, for example, to the knowledge of the practical aspect of something, or practical experience, which arguably underpins all forms of enquiry, research and the creation of new knowledge.

As a set of interacting centrifugal and centripetal forces, research practices take us simultaneously and paradoxically toward and away from disciplined ways of understanding and fashioning the world we inhabit. We look, ponder, write and make; always prompting practical forms, engagements, and processes. As noted, a practice is also a (customary) ‘way of doing’ – in one sense, for the PhD, it is a way of defining your methodology. However, for the artist, it is more than that too. For the social scientist, the PhD thesis will usually include a section that recounts methodology and methods. The former is a broader, philosophical account of the principles of approaching and framing research; while the latter is a more specific account of how the research is carried out. The convention for the scientist and social scientist is to declare an explicit method, with the view that research can be replicated and tested by others for verification and future development. In the arts and humanities, the reproducibility of research is often not so explicitly framed. Nonetheless, the accretions of knowledge in the arts and humanities are crucial and share frameworks and paradigms (e.g. hermeneutics; structuralism; phenomenology; materialism) – these are acknowledged in various ways, albeit at times tacitly (for more on the arts-based paradigm, see Rolling Citation2013). However, the notion of art practice, while including ideas about the method, also suggests a certain level of ‘commitment’ to the working process. It suggests a sustained (even perhaps obsessional!) way of making. We might think of well-known figures such as Pablo Picasso (one of the founders of Cubism), Rei Kawakubo (the Japanese fashion designer, founder of Comme des Garçons), or Philippe Starck (the French designer known for his postmodern interior and architectural work of the 1980s onward). Each of these practitioners can be said to offer signature works, i.e. highly identifiable works. We might conflate this simply with ideas about individual identity and flair – yet, equally we can discern a sustained and enquiring ‘philosophy’ in their works and in their methods. These figures represent well-known, accelerated forms of practice. We might equally consider practices in broader terms, away from individuals as such. If we think of Pop Art, for example, we can refer collectively to a form of ‘investigation’ of popular visual imagery, and particularly ways of re-producing imagery that develop as forms of practice. If we ask ourselves, what is the practice of the pop artist?, we might reply: It is not merely the reproduction of the image, but more fundamentally a consideration of reproducibility itself. Pop Art is about reproduction not just made of reproductions.

With these thoughts in mind, when first embarking upon (and indeed when applying for) a practice PhD it is really important to consider how you define your practice; and also how you might wish to see your practice develop. One way of understanding this is to consider it an opportunity to challenge, deepen and accelerate practice. In order to do so, it is necessary to arrive at the PhD with a sense of a practice, i.e. that you consider yourself a practitioner looking to pursue a particular interest, situated within a wider field or community of practice. One of the common mistakes of the PhD application is the outlining of a pre-formed ‘project’. Sometimes, projects simply are projects, which can be pursued equally well (and often more satisfactorily) outside of a PhD. Sometimes projects are useful vehicles or containers within which to pursue the practice of your PhD, but in this case they need to be starting points, not endpoints. In short, the difference is between a ‘project’ (which practically speaking can be executed) and a ‘research project’ (which will have specific parameters, but its final shape is not known). We might summarize the difference between projects and practice as follows:

Your practice will involve and enfold numerous projects, but just as the novelist exists beyond the individual novels they write, the practitioner exists beyond the projects they pursue. The critical question is: what is it that you do? Encapsulated in this question is not just a question of method (the nuts and bolts of what you do), but an ethic, a philosophy: why do you do what you do? What is this leading to? Who are you in the pursuit of what you do? … and ‘how’ are you in the work? In brief, as Macleod and Holdridge put it:

… the crucial difference between the work of a professional practitioner and the work produced for a Ph.D. is that the latter must justify, qualify and reveal the nature of the body of work for examination. This process can be loosely termed as presenting the methodology that underpins the submission. (Macleod and Holdridge Citation2005, 197)

It is also important to emphasize the need for practice research to be investigatory – to be a form of ‘search’ and enquiry. And, crucially, for the PhD to be an investigation that is not merely a personal pursuit. Here it is worth situating the PhD within the broader analysis of university research. The previously mentioned Research Excellence Framework is a research impact evaluation system for all British higher education institutions, designed to provide accountability for public investment in research. Putting aside a wealth of debates (and detractors), it is useful simply to cite the framework’s central definition of research as: ‘a process of investigation, leading to new insights, that are effectively shared’. The neatness of this definition is that it allows for all kinds of research, across the full spectrum of any given university. Despite lots of misgivings from the arts disciplines themselves about such a framework, even in regarding art as research, art practitioners can relate well to this definition. Whether studio-based or not, artists are generally always involved in some form of ‘investigation’, and equally are often very capable of sharing their work. This leads to the third component: new insights. This brings us back to the requirement of the PhD for the creation and interpretation of new knowledge. Again, it is important to be cognizant of a pertinent context and field, so as not to overreach, but art practice, as much as any other form of investigation, can lead to ways of thinking anew, to combining with other considerations, to make us reflect. A PhD candidate would not be expected to found a whole movement (such as Cubism!), but, nonetheless, it is the same sense of ‘practice’ (a pursuit, enquiry, commitment, questioning) that can be sought. The practice PhD can, and should, contribute to a long-standing field of seeing, thinking and making – it is on this plane that new insights can be borne.

Creativity / research

One of the difficulties in defining an art practice is the artist’s predilection for exploring all manner of things ‘outside’ of art. The pop artists drew upon imagery that was (at the time) not considered part of the artworld; conceptual art has strayed into all sorts of philosophical quandaries; the opening up of new media and mixed media has led art into domains as varied as fashion, film, acoustics, and forensics; while the political contexts of art (not least since the 1970s) has dramatically expanded the contexts and status of art and artists. Art proves to be highly malleable and shape shifting. It accrues an ever-expanding ‘social’ archive of meaning and output (Foster Citation1996), which has the benefit of allowing us to define and redefine art ‘practice’ in a multitude of ways, but, inevitably the risk is that we lose a sense of common discourse and ‘definition’ – which again, for the PhD, can give rise to a lack of confidence, both for the individual practitioner and the field as a whole (in terms of its legitimacy as a doctoral subject).

Part of the problem is historical. Indeed, we might date the problem back to Plato. In the Republic, as we know, Plato considers art to be about the imitation of life. Since he considers life to be only a copy of transcendental Forms, the work of art is a copy of a copy of a Form. It is an illusion, which at best can be used as entertainment, at worst is delusion; dangerous. This position relates also to the Greek mythology of the creative muses. The number of Muses, their origin and their roles, vary in different accounts and at different times, but they were consistently linked with the nature of artistic inspiration. This raises a question for philosophers past and present: is a creative person an empty vessel into which the Muses pour their gifts, at their will, or can the person do something to make inspiration flow? The pre-Socratics took the position that we can be inspired by the muses, but still with a sense of an individual’s own positive, active creative input. In this sense, the poet or artist is active, i.e. a creative in their own right. With Plato, however, as found in the Ion, poets are portrayed as passive and irrational instruments of the muses. Poets do not create through techne, through skill or craft. They create through a state of frenzied ecstasy. In this account, the Muse enters into them, takes possession. There is a chain of influence: Muse to poet to rhapsody to audience – all placed in a ‘wild’ state. The underlying argument is that poets do not understand what they are talking about. Hence, we are led towards a hierarchy of knowledge that arguably still persists.

As noted, in the Hellenistic period, the Muses were allocated to different disciplines, and interestingly prove to be easily visualized. So, for example, Calliope (epic poetry) is associated with the writing tablet; Clio (history) with the scroll; Euterpe (lyric poetry) with the flute; Melpomene (tragedy) with the tragic mask; and Urania (astronomy) with a globe and compass. The iconography of the muses is epitomized by Nicolas Poussin’s painting ‘Parnassus’, or ‘Apollo and the Muses’ (1631–1633). Yet, paradoxically there is no muse of visual art (except dance) – again we detect a hierarchy, which undermines the visual arts. Vermeer considered Clio (the muse of history) to be the painter’s muse. This is perhaps one reason why history painting was long regarded the highest form. Poussin’s work, for example, is characterized by clarity, logic, and order, and favours line over colour. Until the twentieth century, he remained a major inspiration for classically oriented artists such as Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Paul Cézanne.

Of course, today, art and artists have assumed a stronger footing and a sense of identity, not least associated with social critique (at least since the political practices of the 1970s onwards). Yet, the idea of the artist as ‘researcher’ has proven more resistant. The artist and writer Victor Burgin characterize the circumstance as follows:

… the word ‘research’ may conjure images of white-coated scientists, electron microscopes and particle accelerators. This same commonsense would probably allow that the term also apply to the image of a tweed-clad historian, among piles of documents in a dusty archive. In both cases, the outcome of research is assumed to be knowledge – of the cause of the common cold, of the behaviour of electrons, of the causes of the First World War, and so on. Neither dictionaries nor commonsense associate the term ‘research’ with the image of the artist. Picasso declared: ‘I do not seek, I find’. The assertion succinctly confirms commonsense understanding: scientists and scholars ‘research’, the artist ‘creates’. (Burgin Citation2006, 106)

The modern art school owes its very existence to scholarship. In the Middle Ages, the arts were divided into ‘liberal arts’ and ‘mechanical arts’. The former were intellectual disciplines taught in universities, the latter were manual skills taught in artisanal guilds. In the Renaissance, painting began to be considered a liberal art by virtue of the superior learning then required of the painter – primarily in geometry, anatomy and literature mainly classical mythology and biblical texts). […] The 1648 Académie inaugurated the modern art school by bringing theoretical and practical knowledge together in a coherent teaching. This newly intellectual status of art was confirmed and consolidated in the other discursive-institutional inventions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – aesthetics, art history, art criticism and so on – to form the foundations of the modern art institution. In effect, the teaching of the first academy was a response to the question: ‘What does an artist need to know to establish the basis of a literate and informed practice?’ (Burgin Citation2006, 102–103)

The course that was subsequently approved and taught was based on three components: history (knowledge of the evolution of changing forms of film and photography); sociology (knowledge of the socio-institutional context, and political economy, of film and photography); semiotics and psychoanalysis (knowledge of the construction and derivation of meaning and affect in photographs and films). These three types of knowledge formed the basis of a history and theory curriculum that occupied fifty per cent of the three-year undergraduate course. Inevitably, ideas and terminology from this curriculum entered the studio ‘crit session’, but scholarly research in history and theory was never confused with the practices of critical debate in which it might be deployed – each area was recognized as possessing its own discursive specificity, and criteria of legitimacy. Some students who completed the BA ‘theory-practice’ course at PCL went on to write PhD dissertations in university humanities departments. Today, they would have the option of studying for a PhD degree in a visual arts department. (103)

I was once introduced to a student who, after reading Bachelard (and my own book) on ‘space’, made an installation of stuffed toys that he turned inside out – so that all their electronics, and other hidden details, became their exterior surface. There is nothing in either Bachelard or in my own work to recommend this treatment of stuffed toys, but if this person had not read the theory he might not have thought of doing this. […] He was unable to tell me the title of the book he had read by Bachelard, nor was he able (greater cruelty) to remember the title of my own book. It had clearly not occurred to him to wonder whether there was agreement or contradiction between my own arguments and those of Bachelard, or what (if anything) Bachelard’s use of the word ‘psychoanalysis’ has to do with the Freudianism of my own work. But these are precisely the kinds of issues he would have had to deal with – given his declared point of departure in the two texts – if he had been writing a PhD. (104)

… visual arts departments confidently assessed such students before the coming of the PhD. Throughout the history of art the finished ‘work of art’ has represented the culmination of a process of research; a large part of the routine work of artists is a work of research. Although the shift from a language of ‘creativity’ to a language of ‘research’ may confuse that part of commonsense inherited from nineteenth-century Romanticism it is otherwise easily justified historically. The question of whether visual art production constitutes research is not a significant issue. The substantive issue for visual arts departments now is the widespread inability or disinclination to clearly distinguish between an art work and a written thesis, a tendency to obfuscate or ignore the differing specificities of two distinct forms of practice. (104–105)

her mise-en-scène of the Socratic dialogue in a space of domestic labour constitutes a feminist critique of Plato’s text. […] The instructor replies that to expose this fact is not to argue it; although the film provocatively and successfully suggests the basis of an argument, it does not make the argument. (105)

It has to be encouraged, but provided that it does not come at too high a price, provided that rigour, differentiation, refinement do not suffer too much as a result … That is what I said to them … when I explained: ‘If your film had been accompanied – or articulated with – a discourse refined according to the norms that matter to me, then I would have been more receptive, but this was not the case, what you are proposing to me is coming in the place of discourse but does not adequately replace it’. (Cited in Burgin Citation2006, 106)

historic divisions between liberal education and vocational training remain. These divisions colour the current debate about the character of visual arts education as they do the relationship between theory and practice within this and the role of research and intellectualisation within arts practice. (Citation2008, 173)

However, we need to remember that (western) art schools now rarely teach skills and are largely ideas based. They also often ‘punch above their weight’ in terms of research output. In this sense, Bell is more relaxed about who can pursue research, and how, but he acknowledges assessment remains a critical issue:

The research programme and assessment commitments of such candidates have to be negotiated on a case-by-case basis with the proviso that every candidate accepted onto a PhD by practice mode should expect to produce both a body of critical writing contextualising their work and a body of documented practice. They should also be able to demonstrate clearly to their examiners that the body of work presented is motivated by a research design within which a studio practice methodology (in the widest sense) is a major investigative context and strategy in advancing their research. The issue I believe is not one of defending an outmoded notion of academic rigour by demanding that PhD candidates produce a dissertation of a stipulated word length, nor is it one of romantic resistance that demands that practice candidates be free to present only creative work without an obligation to contextualise this in a body of writing. Rather our aim as doctoral supervisors and mentors should be to encourage a circle of reading, making, documenting, reflecting, writing up, public communication and criticism – a ‘virtuous hermeneutical circle’ of critically informed practice.

… most sets of doctoral regulations within UK universities can accommodate the above requirement. No special category of professional doctorate or doctor of fine arts degree is necessary. The plurality of forms of practice-based research can be facilitated within the existing PhD award. Perhaps rather than fretting about the stipulated word length for written components of practice-based PhDs or defending the primacy of the art object as a stand alone codification of new knowledge about the arts, the pressing task is one of identifying exemplars of good practice which might lead doctoral candidates to make informed choices about their research design. (Bell Citation2008, 177)

The requirement to produce critical writing is notable in Bell’s position. It is a matter of much debate and, for some, consternation. However, one way of looking at this is again to remind ourselves that the PhD is not simply the pursuit of one’s practice, it is an examination; it is an education. Education should not be ‘comfortable’, in the sense that there should be definite progress and growth – it should ensure you go somewhere that you would have not gone without the opportunity to reflect critically and so to develop your understanding. We also need to add in the fact that the PhD as a form is not just about the development in the understanding of knowledge, but also a new contribution to knowledge itself. The idea of merely producing an artwork (or collection of artworks), i.e. to simply submit your ‘practice’ alone seems spurious. No other subject area can be thought to do anything equivalent. For a history PhD, for example, it would not be sufficient to submit a ‘book’ on an area of history. It is necessary to submit a ‘thesis’ (which will account for meta-aspects of methodology, methods, theoretical position, and set out insights, etc.). As Elkins (Citation2013, 50) notes: ‘Any number of practice-based PhD programs produce art that is considered as propositional: it embodies, or suggests propositional knowledge. But almost all such programs also require dissertations’. He goes onto note a ‘fascinating and understudied example of the claim that images alone can argue comes from Roland Barthes, who in 1979 approved a PhD that consisted only of images’ (50; see Rowe Citation1995). A more recent reference point might usefully be John Berger’s (Citation2011) Bento’s Sketchbook – although, of course, this does not purport to be a thesis, let alone a PhD submission (for more on the relationship between text and image and the visual as argument, see Manghani Citation2013; Elkins Citation2013).

In keeping with Bell’s remarks, it need not be taken that there is only one format for producing the necessary critical and contextualizing aspects of a PhD, rather a student (with the support and guidance of their supervisors) can negotiate the formulation of a thesis on a ‘case-by-case basis’ – indeed this is necessary as it will be work that has not been ‘contributed’ before. Yet, it is work that still needs to establish itself for examination (by peers). To return to the analogy of the driving test: this is not a test as to whether you can drive somewhere (perhaps to pick up the groceries for the week). Of course, this will likely be an ‘instance’ of driving for which, in the end, you want to pass your test. But, for the test itself, you are being asked to demonstrate your ability to drive in a ‘general’ sense and to know what that means (i.e. what good driving constitutes). And of course, the driving test does include an explicit theoretical component, but this is just a small element of a broader demonstration of your awareness and skill in driving (to someone else who can drive, i.e. a peer). The driving test is calibrated to demonstrate your ability to practice the theory of driving.

From the archive: enactment of thinking

The reader is encouraged to consult a full list of practice-PhD articles from Journal of Visual Art Practice (see Appendix). However, one article is worth exploring in detail here as it usefully frames up a number of critical considerations. The article in question is ‘The Enactment of Thinking: The Creative Practice Ph.D’ (Citation2005), by Katy Macleod and Lin Holdridge (who also, a year later, published Thinking Through Art: Reflections on Art as Research, Citation2006). The authors are clear in their understanding of the creative practice PhD as a ‘dual submission of writing and artwork, and that the two are interrelated objects of thinking’. Of particular note, they provide excerpts from Elizbeth Price’s PhD, which she had submitted to the University of Leeds in 2001 (Price went on to win the Turner Prize in 2012). Interestingly this work offers what they describe as ‘live and intense scrutiny of the processes of creative practice research and an ironic reflection on the higher research degree culture’. In this sense the work relates well to the conceptual thinking of Marcel Duchamp, but also, they suggest, the painter Pierre Bonnard. The following excerpts provide a sense of their overall account:

It is our contention that the creative practice Ph.D. content is revealed through the dual submission of writing and artwork, that the two are inter-related objects of thinking. However, the thinking manifested in the written text is in the order of a strategic contextualization to the realized artwork, which has a provenance unique to the field of higher degrees. Here, the intellectuality of the work can only be characterized as revelatory in the sense that this thinking is not verbalized; however, it can be perceived and understood. For our purposes it will be understood at the moment of the Ph.D. viva, as a visual enactment of thinking. The in question is dependent on the inventive and intuitive powers of the artist/researcher; its logic seeks ambiguity and a playful exchange of a sustained and unsustained new knowledge, an intellectual game of now-you-see-me-now-you-don’t or, in Freudian psychoanalytic terms, a fort-da game of playing out loss and retrieval as the artist comes to terms with meanings which are transient. What art offers, above all, is a speculation. (197–198)

In the case of the Ph.D. submission, the artwork presented comprised an off-spherical form of roughly two metres in diameter. The form was constructed by packing tape being wound off a manufactured roll and on to itself. This process of winding tape from its manufactured state to a state of the artist’s devising was started eighteen months before the Ph.D. viva and is still ongoing. The piece itself, is characterized as Boulder. The accompanying written text (roughly 100,000 words) The accompanying written text (roughly 100,000 words), is typed in what the researcher identifies as an administrative format, that is, it covers just two-thirds of the page and is light in tone, almost as if it could have emerged from a fax machine. (198)

The solidity and weight of the boulder are important because they testify to the production of the thing. And this, the question of how the boulder was made is the prevailing ambiguity which ultimately necessitates these kinds of physical verifications. If the boulder is too light, then it was not produced entirely by winding tape. It might therefore be hollow, or include some other material. Weight is a means to gainsay, or corroborate the apparent visual evidence of the sphere. The testing and corroboration of evidence is time consuming and unending; here it is unpicked and pitched into a philosophical/theoretical arena by the conjunction, in an endlessly repeated ploy, of: So is the boulder a compact mass of wound tape? Did I make it in the way that I claim? Was it made in the way it appears to have been made? Certainly only one material and method is disclosed, but this does not preclude the possibility of others. And clearly the tape lends itself generously to these doubts in as much as it functions as a kind of skin, which conceals and encapsulates other materials. There is certainly nothing evident that would disprove the possibility of deception. Even if the weight were consistent with a solid mass of tape, it would not prove that this was the nature of the mass; it might simply suggest a more sophisticated hoax. In such a light the seemingly matter-of-fact descriptive qualities of the boulder, and the seemingly ingenuous descriptions of this text maybe begin to appear tactical rather than candid. (Cited in Macleod and Holdridge Citation2005, 199)

Boulder is thus both a demonstration and a questioning of this demonstration of the artist’s research labour, a labour which pitches the ‘boulder’ ‘into a philosophical/theoretical arena’ by hinting that this labour might, in fact, be bogus: ‘Is the boulder a compact mass of wound tape? Did I make it the way I claim? Was it made in the way it appears to have been made?’ This questioning reflects sustained misgivings about the research requirement of the demonstration of the proof of research, a proof dependant on a methodology, which is here described as tactical rather than candid. However, it is precisely through this questioning of methodology that the formulation of the theoretical premise of the submission becomes possible: the validity and provenance of Boulder as research. (199)

Boulder is emphatically identified as art because the ‘boulder’ is form. The ‘boulder’ is also a misshapen form and represents a philosophical speculation on the provenance of form. […] This being the case, there will always be a very particular relationship between artist and object and viewer. (199).

… the ‘ready-made’ is not artistic, it is a critical or philosophical gesture. […] The ‘ready-made’ is neutral; lacking context, it lacks significance, although once perceived as a ‘work of art’ by external sources, it will be invested and reinvested with meaning. To counteract this, Duchamp invests his ‘ready-mades’ with irony to sustain the anonymity and neutrality of objectification. […]

The connotations of the ‘ready-made’ provoke endlessly circular arguments – if it becomes a work of art, the gesture is destroyed; if it remains neutral, the gesture becomes a work. […] The contradictions have resonated through the decades, but the purity of Duchamp’s own intelligent rationale survives as an art of interior liberation. In this sense, it is a timely reminder, particularly for the purposes of higher degree research into creative practice of the need for intellectual integrity and adherence to principle in order to build and strengthen the culture. Duchamp’s resistance to the politics of his host discipline is also a timely reminder. (201)

Macleod and Holdridge make a strong case, but of course a dilemma emerges: Does the practice PhD have to be centred upon conceptual (and ironic) art? There is an argument to say that the art PhD does seem to privilege conceptualism (or at least makes the practice and the written components more natural bedfellows). Usefully, however, Macleod and Holdridge provide a further example with the work of the painter Pierre Bonnard, who in common with Price and Duchamp considers the relations of viewer and object (and text and context), yet whose work is of the retinal and material image:

One of the themes which preoccupied Bonnard throughout his career was the way in which the consciousness of vision is composed of random perceptions, and the fact that vagueness, incompleteness and uncertainty are a vital part of this consciousness. This concept closely follows the literature of the time, in particular the writings of Mallarmé and Proust. William James, the philosopher brother of the writer Henry, aptly sums up this precept as: ‘The reinstatement of the vague to its proper place in our mental life’.

The way in which Bonnard translated these ideas into his paintings can be exemplified in The Pears or Lunch at Le Grand Lemps (1899?). Sarah Whitfield, in a recent Bonnard catalogue,explains how the white-covered table recedes into the back of the painting creating a suggestion of emptiness occupied by a floating succession of impressions and memories. The objects on the table are noticed, but in a casual manner. (204)

And while Bonnard’s motifs might appear at first mundane, Macleod and Holdridge note:

the presentation is both complex and radically innovatory; the spatial distortion and a determined and sustained autonomy within the work speak louder and with more depth than any manifesto and assert Bonnard’s uncompromising form of vision. We would contend that not only do the philosophies and methodologies entwined within Bonnard’s work contribute to its radicality, but that his own highly focused, sustained and intelligent artistic enquiry mirrors the intellectual rigour required to undertake a creative practice Ph.D. The process of undertaking such a degree removes it (at least for the duration) from the arena of professional practice into a new and as yet publicly undetermined area of art practice. In this respect, Bonnard’s own practice of remaining outside the mainstream whilst following his own intellectual enactment of thinking could be seen as comparable and as such, a most useful precedent for artist/researchers. (203)

Bonnard’s paintings, painted from memory and over time, require meditation and a silent dialogue between the work and the viewer; the details filter slowly into the field of perception and articulate the original moment of epiphany in its performative representation by the viewer. Above all, we believe that the paintings reveal the rigorous intellectuality of Bonnard’s visual conceptualization.

We contend that the new culture of creative practice Ph.D. research which has evolved from the subsumption of art schools and colleges into the traditional frame of academia, needs a definitive and autonomous provenance rooted in the realm of the intellectual rigour of a practice, in the revelation of a highly conceptualized mode of visuality – the enactment of thinking. This is thinking which is philosophical in nature, but philosophical according to the logics of a practice which founds itself in invention and intuition, in ambiguity and the subjective drives of the artist whose intellectuality is employed remove the certainties of the visual to conceive of what might lie behind what is apprehended in order to make sense of her/his world. (205–206)

There are some potential problems to the final part of this argumentation. There is an insistence on the ‘philosophical nature’ of thinking, which is reasonable in one sense, as indeed the PhD is technically a doctorate in philosophy. Yet, there needs to be room to negotiate the form of philosophy, to ensure it is not, in the end, rooted only in verbal reasoning (Mitchell Citation2008; Simons Citation2008). In the spirit of what is outlined here, this is not what is being suggested, but it raises questions for how we can confidently uphold the ‘philosophy’ of visual arts. Secondly, the final line betrays a conceptualist approach again, with the reference to ‘what might lie behind’, which is suggestive of a hermeneutics of visual art, an attempt to uncover what lies behind the artwork, rather than to accept the artwork as is. This, again, needs some careful negotiation. It is worth keeping these caveats in mind when reading Macleod and Holdridge’s concluding entry:

What we have sought to demonstrate here is that whilst the interpretation of art objects and the objects of art remain open to interpretation, the tracking of an artist/researcher’s methodology is achievable, even though this methodology may be highly speculative. The methodology determines the quality of the artist’s theoretical premise, and this is a premise that is embodied in the artwork. The artwork then bears the burden of research proof; it does this through what we have termed the enactment of thinking. This approximates to the gesture of the artist as theorized by Marcel Duchamp, a gesture that is intellectual in nature. It may, of course, be visual/intellectual as our analysis of the work of Pierre Bonnard makes clear. The issue here is not the status or provenance of the visual but the intellectual range and depth of the artist/researcher’s thinking. This is thinking which is dependant on the artist’s speculations about being in the world according to her/his determining vision of it; this is thinking which is deter-mined by understanding the visual and by the power of that understanding. It is also thinking which is acted through, the enactment of thinking. (206)

The spectre of theory

One of the problems of McLeod and Holdridge’s (Citation2005) ‘enactment of thinking’ is with the word ‘of’ – this operator can lead us back to a dichotomy of making and thinking. They write that the artist’s ‘theoretical premise’ is ‘embodied’ in the artwork, it ‘bears the burden of research proof’. It sounds promising as a position, but it can be seen to still demarcate ‘thinking’ as somehow prior or other to the making (which somehow captures, stores the thinking). On this point, Tim Ingold (Citation2000; Citation2013) is worthwhile reading. He makes a strong case for making as a form of thinking in itself. He notes how we tend to differentiate between natural and culturally produced structures by the ‘intent’ to make them. So, typically, it is thought when bees produce a hive they are not working to a pre-arranged plan or blueprint. They do not have Ikea-like instructions to follow, but instead, the structure forms through the making. By contrast, we tend to say that cultural artefacts are made to a plan, to a prior ‘idea’. Karl Marx once remarked that the worst of architects is better than the best of bees, because the architect has already built the structure in his or her mind before the first stone is laid (Ingold Citation2000, 340). However, Ingold challenges this view. His point is that in order to build, we first have to learn to how to ‘dwell’ – to have a sense of being in a space and architecture before we can even begin to consider the possibility of building. In very simple terms there is a difference between a space that can be lived in and a space that can become a home. A building is not a home. A home is more than simply a building. It is our ability to imagine a sense of place, beyond its space.

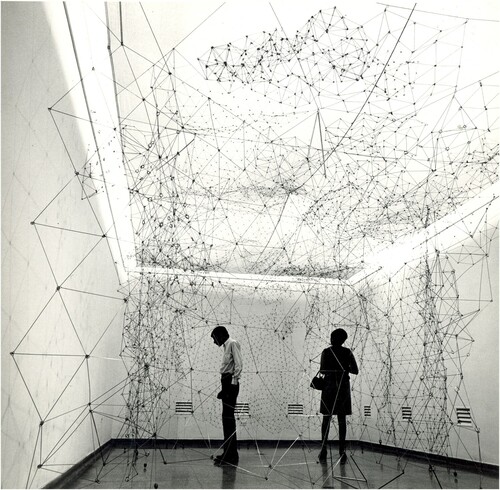

Figure 1. Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Reticulárea, 1969. Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas. Variable dimensions. Photo: Paolo Gasparini © Fundación Gego.

The common error, Ingold (Citation2000, 339–348) suggests, is to consider making as simply representation in reverse, i.e. that a fully formed image in the mind is reproduced in material form. He uses the example of weaving baskets to elucidate. The ‘surface’ of the basket does not exist before the weaving begins. It is built up. It emerges. It is the practice of making. It does not have an inside or an outside. The individual reeds or canes that make up the basket each have their own exterior, which lace into and out of the woven structure. As such, the basket weaver does not have a mental template, but a series of skills or a body of know-how which inform the engagement with the material. There is both entity and environment. A making and ‘thinking’ through space and time. We can imagine accord here between Ingold and McLeod and Holdridge’s account of the enactment of thinking, but Ingold gives more explicit credence to material practices and craft. We might think of the status of installations and site-specific work – which form according to spaces and architecture and our engagement with those spaces. A good example would be the work of artist Gego (Le Feuvre Citation2013). In the 1970s, her most comprehensive groups of works, which occupied her for 12 years, might be said to have possessed her, rather than she made them: they are literally a ‘body of work’. Her three-dimensional constructions of wire, metal elements and diverse materials look as if they are drawn in space. They cast shadows that further intensify their intangibility and transparency. It is worth noting, Gego was reluctant to refer to her works as sculptures. Her practice was an enquiry into or beyond what we mean by sculpture. For Gego, sculptures were heavy, immovable, static. She referred to her works as ‘bichos’, as bugs! Her works were alive to her as she made them. She was inside the works as she made them available ‘outside’ to others (who equally could enter into them).

In addition to making as thinking (rather than of thinking), it is useful to note how McLeod and Holdridge’s reference to speculation provides the basis for more common ground. Indeed, an interest in and willingness for speculation helps us further to break with a purported divide between theory and practice. This division is all too often raised, typically with theory framed somehow as the spectre that haunts over practice. Yet, speculation is as much at the heart of ‘theory’ as it is in practice, at least when we consider theory in the sense of ‘critical theory’, and which, in itself, can be very productive as a part of art practice (Phillips Citation2013). A useful point of reference is Jonathan Culler’s (Citation1997) short introduction on Literary Theory, which opens with a cogent and accessible account of ‘theory’. Obviously, his terms of reference come from the field of literary studies, but his opening remark – that ‘literary theory’ is not about literature as such, but something broader, i.e. not a theory of literature, but just plain ‘theory’ – is equally instructive for the purposes here concerning the role of theory for the art PhD. Culler puts it as follows (for ‘literary theory’ we can read ‘art theory’):

‘Theory’, we are told, has radically changed the nature of literary studies, but people who say this do not mean literary theory, the systematic account of the nature of literature and of the methods for analysing it. When people complain that there is too much theory in literary studies these days, they don’t mean too much systematic reflection on the nature of literature or debate about the distinctive qualities of literary language, for example. Far from it. They have something else in view.

What they have in mind may be precisely that there is too much discussion of non-literary matters, too much debate about general questions whose relation to literature is scarcely evident, too much reading of difficult psychoanalytical, political, and philosophical texts. Theory is a bunch of (mostly foreign) names; it means Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Luce Irigaray, Jacques Lacan, Judith Butler, Louis Althusser, Gayatri Spivak, for instance. (Citation1997, 1–2)

So what is theory he asks:

Part of the problem lies in the term theory itself, which gestures in two directions. On the one hand, we speak of ‘the theory of relativity’, for example, an established set of propositions. On the other hand, there is the most ordinary use of the word theory.

‘Why did Laura and Michael split up?’

‘Well, my theory is that … ’

What does theory mean here? First, theory signals ‘speculation’. But a theory is not the same as a guess. ‘My guess is that … ’ would suggest that there is a right answer, which I don’t happen to know: ‘My guess is that Laura just got tired of Michael’s carping, but we’ll find out for sure when their friend Mary gets here.’ A theory, by contrast, is speculation that might not be affected by what Mary says, an explanation whose truth or falsity might be hard to demonstrate.

‘My theory is that … ’ also claims to offer an explanation that is not obvious. We don’t expect the speaker to continue, ‘My theory is that it’s because Michael was having an affair with Samantha.’ That wouldn’t count as a theory. It hardly requires theoretical acumen to conclude that if Michael and Samantha were having an affair, that might have had some bearing on Laura’s attitude toward Michael. Interestingly, if the speaker were to say, ‘My theory is that Michael was having an affair with Samantha,’ suddenly the existence of this affair becomes a matter of conjecture, no longer certain, and thus a possible theory. But generally, to count as a theory, not only must an explanation not be obvious; it should involve a certain complexity: ‘My theory is that Laura was always secretly in love with her father and that Michael could never succeed in becoming the right person.’ A theory must be more than a hypothesis: it can’t be obvious; it involves complex relations of a systematic kind among a number of factors; and it is not easily confirmed or disproved. If we bear these factors in mind, it becomes easier to understand what goes by the name of ‘theory’. (2–3)

theory involves a questioning of the most basic premises or assumptions … the unsettling of anything that might have been taken for granted: What is meaning? What is an author? What is it to read? What is the ‘I’ or subject who writes, reads, or acts? How do texts relate to the circumstances in which they are produced? (4–5)

Culler gives two examples of theory in his opening chapter: (1) Foucault on sex; and (2) Derrida on writing. In the first case, for Foucault, ‘sex’ is shown to be constructed by the discourses that link us with various social practices and institutions. His enquiry shows how something we take to be ‘natural’ is in fact a construct (even that sexual ‘liberation’ is part of a discourse that then re-incorporates us as subjects). In the case of Derrida, the emphasis is upon re-reading and ‘inhabiting’ texts. This formulates what is referred to as a deconstructive reading, through which Derrida demonstrates (with/through writing) how

writings may claim that reality is prior to signification, but in fact they show that, in a famous phrase of Derrida’s, ‘Il n’y a pas de hors-texte’ – ‘There is no outside-of- text’ when you think you are getting outside signs and text, to ‘reality itself’, what you find is more text, more signs, chains of supplements. (12)

they incite you to rethink the categories with which you may be reflecting on literature [or art]. These examples display the main thrust of recent theory, which has been the critique of whatever is taken as natural, the demonstration that what has been thought or declared natural is in fact a historical, cultural product. What happens can be grasped through a different example: when Aretha Franklin sings ‘You make me feel like a natural woman’, she seems happy to be confirmed in a ‘natural’ sexual identity, prior to culture, by a man’s treatment of her. But her formulation, ‘you make me feel like a natural woman’, suggests that the supposedly natural or given identity is a cultural role, an effect that has been produced within culture: she isn’t a ‘natural woman’ but has to be made to feel like one. The natural woman is a cultural product.

8 things you can do …

To conclude, it is important we ask what makes up a PhD – and to accept it places certain responsibilities upon those undertaking the PhD to respond in appropriate ways (according to the criteria, etc.) But it is also pertinent to ask: What is so wrong for artists to do a PhD? The formulation of the question might seem negative at first, or appear to be on the back foot. Yet, it should be read as an assertive response to a certain defensiveness and resistance to the art PhD, that sadly still persists (and most often within the domain of art education itself!). The dilemmas, as have been suggested, take us all the way back to Plato, but the main concerns put forward are largely misplaced. A more confident and assertive approach can be taken, but nonetheless it should be an informed one. Here, then, are some final, practical suggestions for things you can do when engaging with art practice research:

Accept the PhD is an examination and understand the criteria.

You are doing a PhD. It is a report on knowledge. It is a form of education. It is not supposed to be easy. It will be assessed. Think about the criteria. (Other outcomes can follow from the PhD, but first thing first, it is a qualification and a genre of study and research.)

| (2) | Appoint a good team. | ||||

It is important to look for sympathetic, yet challenging supervisors (look carefully at the kind of work undertaken in different departments and try to locate pertinent supervisors). Equally, don’t feel you must work with specific supervisors just because they are well-known or completed work in your direct area of interest. There are a range of qualities to look for – in brief, you need to find supervisors who will be encouraging and supportive with what you are doing (not what they want you to do!). Similarly, towards the end of your research, you need to select appropriate examiners. It is important to discuss examiners with your supervisors. Don’t be afraid to make suggestions. And you need to consider, realistically, how your work will be viewed and framed by examiners.

| (3) | Take an interest in the debates about practice research. | ||||

As encouraged here, read the literatures on the practice PhD. You don’t need to agree with it all (you can’t!), but you can use the materials to craft (to back-up/argue against) your own statement and position on practice research. Make a virtue out of the fact that there is no consensus (hence your position and positionality is key). The debates and misunderstandings have rumbled on long enough, and will always do so, indeed knowledge by definition is a contested field. The PhD is the opportunity not simply to demonstrate your understanding of this fact, but to have a direct stake in its very contestation.

| (4) | Keep making! (and don’t compare with sciences and social sciences). | ||||

A lot of the arguments about practice research seems to create a false dichotomy with the sciences and social sciences. Why compare at all? Or, why not compare with areas closer to home, such as English Literature, Film Studies, or indeed Creative Writing? Broadly, however, each thesis needs to be handled on a case-by-case basis, not least because each purports to represent new knowledge. Importantly, for the art practice PhD, you need to keep working as an artist, keep making, re-making. The engaged, iterative process of art is a deeply held part of your method. This is not to say it is unique to art, but it is distinctive, and crucially, the PhD will be ‘peer’ assessed – i.e. it will be assessed by examiners within your chosen field (who will most likely be artists themselves!).

| (5) | Be hungry: Place your work within a wider frame of analysis. | ||||

Your ideas will never be entirely ‘new’; there will be precedent. This is not a threat, but a source of security and even pleasure. Connections may take you to far flung places; seek them out. Be hungry for knowledge, ideas and inspiration. In locating points of connections, make note of them (you will need to come back to some areas at different times). Situate your ideas historically, philosophically, politically, methodologically. This is hard work, even endless, and there is no map. Quit asking your supervisor for ‘instructions’ (instead get their guidance, or better enter into dialogue). Thus: Seek first, then discuss with your supervisor.

| (6) | Think about how and when you think (in the studio, in writing …). | ||||

Remember that ‘thinking’ time in the studio is not so different from so-called scholarly thinking (it is just a matter of different methods and fields of enquiry). However, some of the more instinctive things we do when researching and making can get forgotten. It is important – in the context of education – to demonstrate critical reflection. As such, try to slow your process down, to be doubly cognizant of what you are doing and to foreground your processes as a means to contextualize the knowledge of art practice.

| (7) | Be clear about the nature and status of the thesis/practice. | ||||

The written component of your thesis is most likely the first thing the examiner will see. It’ll be posted to them. Your practice won’t (unless it happens to be postal art!). Use the written document to set the record straight, to properly represent your work as a whole.

| (8) | Own it! (… and take pleasure in your research). | ||||

Own it intellectually: You need to consider the ‘frame’ of art: history, discourse, philosophy, methods, movements, alternative histories, visual culture. Own it for yourself. In Roland Barthes’ inaugural lecture as professor at the College de France, in 1977, he spoke of research being outside of power structures:

A professor’s sole activity here is research: to speak – I shall even say to dream his [sic] research aloud – not to judge, to give preference, to promote, to submit to controlled scholarship. This is an enormous, almost an unjust, privilege at a time when [we are] strained to the point of exhaustion between the pressures of technocracy’s demands and of revolutionary desire. (Barthes Citation2000, 458–459)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sunil Manghani

Sunil Manghani is Professor of Theory, Practice & Critique at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK). He is the editor of the Journal of Visual Art Practice, and managing editor of Theory, Culture & Society. His books include Image Studies (2013), Zero Degree Seeing (2019), India’s Biennale Effect (2016) and Farewell to Visual Studies (2015). He curated Barthes/Burgin at the John Hansard Gallery (2016), along with Building an Art Biennale (2018) and Itinerant Objects (2019) at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern.

Notes

1 See, for example, the UK’s Practice Research Advisory Group: https://praguk.wordpress.com

3 For examples of practice research in journals beyond Journal of Visual Art Practice, see: Journal of Artistic Research (https://www.jar-online.net/en); Photomediations (https://disruptivemedia.org.uk/photomediations-machine/); Journal of Embodied Research (https://jer.openlibhums.org); [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies (http://mediacommons.org/intransition/); and Cultural Politics (https://read.dukeupress.edu/cultural-politics).

References

- Barthes, Roland. 2000. A Barthes Reader. Edited by Susan Sontag. London: Vintage.

- Bell, Desmond. 2008. “Is There a Doctor in the House? A Riposte to Victor Burgin on Practice-Based Arts and Audiovisual Research.” Journal of Media Practice 9 (2): 171–177.

- Berger, John. 2011. Bento’s Sketchbook. London: Verso.

- Burgin, Victor. 2006. “Thoughts on ‘Research’ Degrees in Visual Arts Departments.” Journal of Media Practice 7 (2): 101–108.

- Culler, Jonathan. 1997. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davey, Nicholas. 2006. “Art and Theoria.” In Thinking Through Art: Reflections on Art as Research, edited by Katy Macleod and Lin Holdridge, 20–39. London: Routledge.

- Derrida, Jacques, and Bernard Stiegler. 2002. Echographies of Television. Translated by Jennifer Bajorek. Cambridge: Polity.

- Eco, Umberto. 2015. How to Write a Thesis. Translated by Caterina Mongiat and Geoff Farina. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Elkins, James. 2001. Why Art Cannot Be Taught. Chicago: University of Illinois.

- Elkins, James. 2013. “An Introduction to the Visual as Argument.” In Theorizing Visual Studies: Writing Through the Discipline, edited by James Elkins and Kristi McGuire, 25–60. New York: Routledge.

- Elkins, James, ed. 2014. Artists with PhDs: On the New Doctoral Degree in Studio Art. 2nd ed. Washington: New Academia Publishing.

- Foster, Hal. 1996. The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gauntlett, David. 2007. Creative Explorations: New Approaches to Identities and Audiences. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

- Le Feuvre, Lisa. 2013. Gego: Line as Object. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

- Macleod, Katy, and Lin Holdridge. 2005. “The Enactment of Thinking: The Creative Practice Ph.D.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 4 (2-3): 197–207.

- Macleod, Katy, and Lin Holdridge, eds. 2006. Thinking Through Art: Reflections on Art as Research. London: Routledge.

- Manghani, Sunil. 2013. Image Studies: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Miles, Malcolm, ed. 2004. New Practices/New Pedagogies: Emerging Contexts, Practices and Pedagogies in Art in Europe and North America. New York: Routledge.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 2008. “Visual Literacy to Literary Visualcy?” In Visual Literacy, edited by James Elkins, 11–29. New York: Routledge.

- Morgan, Sally J. 2001. “A Terminal Degree: Fine Art and the PhD.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 1 (1): 6–15.

- Phillips, Leon. 2013. “Lyotard’s Dance of Paint.” Cultural Politics 9 (2): 219–226.

- Phillips, Estelle, and Derek S Pugh. 2006. How to Get a PhD. 4th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Rolling, James Hawyood. 2013. Arts-Based Research. New York: Peter Lang.

- Rowe, Wayne. 1995. “The Wordless Dissertation: Photography as Scholarship.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies (8): 21–30. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/publications/wm117r004?show=full

- Schwarzenbach, Jessica B., and Paul M. W. Hackett. 2016. Transatlantic Reflections on the Practice-Based PhD in Fine Art. New York: Routledge.

- Simons, Jon. 2008. “From Visual Literacy to Image Competence.” In Visual Literacy, edited by James Elkins, 77–90. New York: Routledge.

Appendix: Precedents of Practice

From its inception, Journal of Visual Art Practice has played a significant role in the growing debates of the art PhD. Below is a list of pertinent contributions, all of which are worth reviewing as part of contextualizing and positioning a practice PhD. It does not follow that the individual authors are all facing in the same direction, but, taken as a collection, they provide pertinent material for a ‘literature review’ (at least with a view to providing precedents and establishing knowledgeable grounds for research by practice). Journal of Visual Art Practice is one of the very few to publish articles that examine and debate the nature and scope of practice research in art, although there are other journals that provide platforms for examples of practice research.Footnote3 Nonetheless, the wider literatures on practice research exceed those available in journals alone. The reader is encouraged to cast an eye over the list of references used for this article as one starting point to locate other pertinent material.

Each and every practice PhD – on a case-by-case basis – will need to draw together its own key literatures (likely traversing a wide range of areas and issues), but there is also scope to comment on the status of the thesis as ‘practice research’. This can offer confidence to an examiner that the approach taken as been given due care and attention, and furthermore it is an opportunity to make an additional, supplementary ‘contribution to knowledge’ – i.e. to contribute to the wider community of practice research and help position the work as supporting forward-going research.