ABSTRACT

This editorial introduction marks the 20-year anniversary of Journal of Visual Art Practice. It sets out the vision of the newly established editorial team, who took up the editorship of the journal at the start of 2021, which happened to be the journal's 20th year. The article sets out the editors’ commitment to an international and diverse approach, which also recognises the rich history and archive of the journal. At its core, the journal remains steadfastly focused on visual art practice. Thus while cognisant of shifting trends and modalities of academic publishing and research, the editors renew the journal's ethos and practical undertaking in presenting the best in new visual art practice research.

It is a great pleasure to have taken on the editorship of Journal of Visual Art Practice in what is its 20th year. This issue has been put together with the anniversary in mind, both to look back, to offer reflection, but also to look ahead and to put into practice some timely changes.

First, we would like to recognise the excellent work of the Journal's previous editors, who, in chronological order over the journal's first two decades, include: Iain Biggs, Richard Woodfield, Chris Smith, and more recently the joint editorship of Mary Anne Francis and Craig Richardson. Importantly, as we take the journal into yet another phase of its development, we are equally mindful of joining a collective stewardship. One that maintains but also always looks to build and develop on what has already been structured and achieved, in accordance, inevitably, with the situations of knowledge production and sharing we find ourselves in.

We are delighted to say that this issue opens with a frank and thoughtful reflection by the journal's founding editor, Iain Biggs, who situates the journal's creation story within the complex pragmatics and accounts of his ‘chance’ editorship which becomes shaped through his personal convictions. He notes how the journal emerged under the particular conditions of educational reforms, a growth in a research culture ‘underwritten by doctoral study’, the establishment of institutional research auditing coupled to the lure of new funding and the associated debates that impacted arts education as the journal formed. These converging situations and resultant demands led to a journal of visual art practice as both a symbolic and pragmatic response by Biggs to create an alternative space for the ensuing research debates.

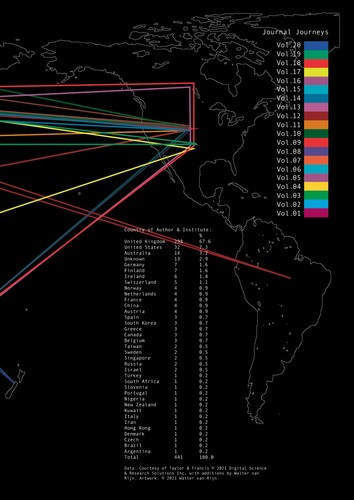

This issue also includes a visualization of the journal's history (more of which below), as well as a reflective and forward-looking piece by Howard Riley, whose various contributions to the journal, particularly on the subject of drawing, date back not just to the very beginnings of journal, but indeed to the protean debates and gatherings that were influential in its inauguration; a narrative that weaves and connects with Biggs’ reflections of the development of the journal. Editor Sunil Manghani's ‘Practice PhD Toolkit’ also acts as a timely account of a trajectory attendant to both historic and current debates, in this case specific to the practice PhD. It includes a catalogue of the many articles over the journal's first 20 years, reflecting and commenting in their heterogeneity upon the emerging and evolving state of the practice PhD. The article connects the dots with Biggs and Riley's accounts, while ultimately arguing in defence of and offering vital support to the growing global engagements in practice research.

This issue also, then, looks forward. The cover of the issue and article by artist Nahem Shoa, for example, offers insight into his exhibition, ‘Face of Britain’, which, due to the Covid pandemic, ended up running for the duration of a whole year at Southampton City Art Gallery. Shoa comments on his development as an artist of mixed race in the early 1990s, along with providing a detailed account of his painterly technique in producing his signature large-scale portraits of Black subjects. Crucially, in also acting as curator, he brought these powerful works together with key portraits held in the Gallery's ‘canonical’ collection, so offering a juxtaposition of contemporary paintings with historical works dating back to the seventeenth century. As Shoa puts it, the exhibition asks us ‘head-to-head’ how diverse we are, so contributing importantly to live debates of decolonisation and the growing acknowledgement of social inequities (not least further exposed by the Covid pandemic). The issue also concludes with a Lousia Lee's thoughtful review of Lauren Fournier's recent book Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism. The book, Lee explains, is the first to offer a broad and expansive overview of autotheory in terms of feminist art practice. As a critical term, which both challenges and conjoins the autobiographical and the theoretical, autotheory powerfully draws together an author or maker's bodily experience through memoir, poetry, philosophy and criticism. As Lee clearly sets out, the approach provides an important opportunity ‘to open discourses’ around the subject, so providing the potential for alternative and serious ideas regarding how we understand the production of theory.

Journal practice

So, what does it mean to take on the editorship of a journal, of this journal? An analogy might be drawn with Jacques Derrida’s (Citation1993) case of the images he curated for the Musée du Louvre, under the title of Mémories d’aveugle. These were not simply representations of the blind, he noted, but self-reflexive accounts of drawing itself as blind (image-making being of the very conditions of blindness). The editing of a journal, wherein you can never be sure what will come forward next for publication, and where the very temporality and serialisation of publication means that one ‘bead’ will soon knock onto the next (making associations, sometimes, not always in accord, or even taking us in quite different directions), means we are always looking ahead, yet not necessarily seeing what is coming. We invite our contributors to do the looking. The editing of a journal is, on the one hand a technical undertaking (a time-consuming activity), but it is also a collective endeavour, an accumulation, a series of traces. Blindness, Derrida writes, enables the ‘seer’, the ‘vocation of a visionary’ (2), a thought he then combines with the act of drawing as ‘an eye graft, the grafting of one point of view onto the other’ (2). A journal is blind in this way, a grafting of one point of view to another.

What happens when one writes without seeing? A hand of the blind ventures forth alone or disconnected, in a poorly delimited space; it feels its way, it gropes, it caresses as much as it inscribes, trusting in the memory of signs and supplementing sight. It is as if a lidless eye had opened at the tip of the fingers, as if one eye too many had just grown right next to the nail … (Derrida Citation1993, 3)

What happens when a journal publishes without seeing? We are not suggesting – not for one moment – the publishing of the first scratches of memory, the barely formed. After all, there is the whole editorial process to contend with. Yet, equally, we hold out for the ‘archive’ of meaning before it is overly codified, before saturated with ‘knowledge’ (the kind that is merely old news, derivative). A journal seeks the new, the unsaid, unseen, unthought. Roland Barthes (Citation1985) similarly referred to drawing in terms of blindness (specifically in relation to the artist Cy Twombly) and went further to suggest the history of painting has been subject to the ‘repressive rationality’ of vision. The eye, he writes, is related to reason and evidence, ‘everything which serves to control, to coordinate, to imitate; as an exclusive art of seeing’ (163). Blindness, however, offers a different way of relating to the act of drawing – as a way of bringing together reflection and the body (or more specifically the hand), and of ‘seeing’ again, or for the first time. There are layers upon layers, and in amongst these layers arise new points of departure.

When nascent discussions about taking on the editorship occurred at the end of last year this prompted some soul searching. At stake is a practical as much as philosophical question. To consider, for example, whether or not we want to take on what we knew to be a significant undertaking, balancing this amongst academic and research responsibilities, knowing that to make any meaningful impact or change would take time and therefore requires long-term commitment. Our discussions ranged over how we might want to work with a journal, and what we believed this undertaking might entail, leading us to think about the possibilities this moment might afford in developing our collective ‘practice’, working as a team. Taking stock, revising and relooking at the aims and scope, redesigning for the possibility of renewed engagement with research in art practice, recognising what was needed was not a departure from but a recalibrating of the existing journal, reaching out to our networks and building on and reawakening existing connections, aligning all of this into an expanded ‘journal practice’.

The Journal of Visual Art Practice, as we set out in the Aims and Scope, is to be:

… a forum for advances in visual art practices and their critical contexts, engaging with diverse, global and interdisciplinary perspectives. It addresses the multiplicity of debates in art histories, theory and critique, and the inquiries of art practices, methods, and approaches. It is concerned with the specificities of art making as well as cross-cutting, inter- and trans-disciplinary explorations, and with the exchange and contestation of ideas and knowledge this forms.

The Journal recognises the value of research into visual art practices through different modes of enquiry and documentation. It welcomes submissions in a variety of formats […] We encourage contributions covering a wide range of interests in art and visual art as they pertain to critical, philosophical and cultural contexts, the exploration of methods and methodologies, and interdisciplinary exchange. Overall, we seek to represent the inherent breadth and expansion of visual art practices, their critical reception and social and philosophical impact. (adapted from ‘Aims and Scope’, Journal of Visual Art Practice webpage)

Our impetus has been the potential to build on twenty years of the journal, using the space as new editors and our expertise, commitment and experience to critically reflect on what had gone before, thinking through our roles and responsibilities and team dynamics and how together this might give potential in strengthening and evolving the operations and scope of the journal. Reviewing the existing materials published over a significant period offered up the opportunity to consider how this as a resource might be leveraged in terms of an existing journal history and presence in the publishing field. Over the years, for example, the journal has given space to a wealth of special (and very diverse) issues (see Appendix). With this archive comes an existing network of interests and engagement, acting as a springboard to develop the wider dissemination which we see is needed; expanding the journal's networks to encourage and grow more authors, new voices and find ways to activate and cultivate audiences from the geographic and intellectual periphery, to stimulate new exchanges and to take the contents of the journal beyond the current confines of its published lifespan into new territories and spaces. As a ‘journal practice’ the question is how to pragmatically make this happen rather than merely signal aims and ambitions that, while laudable, need also be achievable and believable to the outside world and to us as a team.

How, then, to develop new spaces for encounter, response, dialogues and for different modes of engagement with the many practices within the journal and the potential audiences who might not engage or read the journal? How might we utilise nascent engagement with digital opportunities such as short video formats, a format underused by contributors, editors and those engaged via the journal's website? How too will existing criteria still apply as research and publishing needs shift? How might we refocus attention on the journal and equalise the footing for the diversity of practices and ways that we might allow for this to work with the structure of the journal? The revised aims (noted above) have been a first step towards articulating a wider purview, paying particular care in terms of inclusivity and as a platform for newer and more diverse forms of practice. In some respects, this puts into question the mechanics of the journal and the existing formats, prompting us to interrogate how we bring more focus to visual art practice and therefore how we bring practitioners into the journal by increasing the variety of formats, affording new opportunities for artistic research and practice to be documented, shared and considered.

It is also important to reach out internationally as there are many excellent things going on elsewhere and often with strong institutional support. Building a keen, engaged international advisory board is vital. The questions we have asked ourselves about how we do this, the spheres that we might operate within, and the communities that we might more actively engage with, has prompted us to take action and we are pleased in this issue to announce our five new Associate Editors: Nikhil Chopra (India), Amanda Watson (New Zealand), Feng Jie (China), Eria Solomon Nsubuga (Uganda), and Margaret MacNamidhe (USA). The global spread, activity and engagement, in their respective regions and beyond, is one of the actions we have taken to engage in other paradigms of knowledge, practices, histories and developments which support our vision to provide new networks and opportunities. These additions acknowledge the need for a wider team representing, advising and advocating on behalf of the journal across diverse cultures, geographies and languages, bringing new understandings, networks and a more global, critical sounding-board for the editorial team. We are also bringing some new faces into our editorial board, but importantly we look to engage with and work more actively with the existing board who have contributed to the journal over the years as authors, peer reviewers and more besides. We recognise the importance to engage regularly with the board, as this is often the best means to open up new ideas and to help solicit high-quality contributions and themed issues. The need for a strong, diverse and internationally-minded editorial board is urgent, then, and while the current board is almost entirely ‘western’ this can be greatly enhanced by reaching out further afield, which we have now started to action.

Over this first year, then, as editors, we have revisited and interrogated the intellectual claims of the journal with respect to its terrain and field of study and practice. By looking at the journal's archive we can further address what has been signalled in terms of diversity against the actuality, such as global reach or the pan-national character of the journal where local and international voices might discuss practice beyond country of origin, historical specificity and also as a by-product of contemporary mobilities. We are committed as an editorial team for renewed global engagements, to further explore artistic enquiry through others’ global lens and are giving focus to where renewed energies must be placed in reaching out to build our networks and create opportunities to publish and therefore better understand other localities and these mobilities of practice. The possibility of the journal becomes evident to us as we develop each issue, both as a space that might acknowledge the complexities, nuances and opposing ideas that make the field so vital, but also to give proximity to new, established or marginal voices. The symposium format can be very effective in bringing new people and therefore new ideas to the table, and furthermore as a direct mechanism to encourage potential contributors to begin to work on submissions that can then be honed and edited by guest editors.

What ways might we judge the journal's qualities beyond journal metrics in scholarly publishing and the dominance of impact factors in the assessment of research? There is a need to pay attention to the changing nature of academic publishing, which increasingly is becoming digital, multi-modal and open access. Crucially, in order to respond to new developments, Journal of Visual Art Practice must attend to its digital footprint, which at the moment is very limited (beyond the publisher's journal homepage). It is also pertinent to explore funding and other means for encouraging open access agreements (e.g. for individual articles and/or special issues). It is also important to look at citations, which when maintained and strengthened help a traditional publication such as Journal of Visual Art Practice to stand its ground within a wider, innovating field. We are cognisant of the issues of visibility for the journal within a wider constellation of related publishing and ‘journal practices’, with a number of new developments, typically related to online forums and platforms. Consider for instance, Journal of Artistic Research (established in 2010), which is ‘an international, online, Open Access and peer-reviewed journal that disseminates artistic research from all disciplines’. Crucially, it describes itself as a ‘digital platform where multiple methods, media and articulations may function together to generate insights in artistic research endeavours. It seeks to promote expositions of practice as research.’ Similarly, the online venues of MAI and Photomediations are other pertinent examples. Nonetheless, all of the usual conferences and events have been ongoing, and arguably without a great deal of innovation. Perhaps one consideration is the explosion in biennales around the world, of which the Kochi Biennale in India has been an interesting example – something editors Ed D'Souza and Sunil Manghani examine in their book India's Biennale Effect (Citation2016). There is a great deal of energy around the global art scene, but generally it lacks criticality – and often knowingly so, prompting a useful space for partnership with platforms such as online and traditional journals.

Situations of research

In considering the journal's history, so tracing back to its inception in 2001, its publication was indicative of a significant wave of business expansion by publishers launching new academic journals. This expansion saw the potential of accommodating the needs of universities to evidence research activity through outputs required by the UK Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) in 1991. This in turn conversely gave new venues for academics to meet the demands to produce peer-reviewed published research outputs for the RAE. Currently at a national level, there is a maturing of art research across the sector, evident with the results of REF2014 (the new incarnation of the previous RAE), and the subsequent critical reflection of that census (synthesized further in the recent REF2021, which will almost definitely lead again to a further enhanced and confident field). Setting aside the deeper questioning and debates surrounding REF, it can nonetheless be said, in itself, to create greater demand for high-quality ‘outputs’ of research. Equally, as a sympathetic reading of the framework, it has meant that, institutionally, publications such as Journal of Visual Art Practice have become greatly valued, supporting researchers in their endeavours, not least in enabling special, themed issues. In this respect, it is important to look within the sector for new ideas and energies and champion these as a community of practitioners (rather than simply try to draw up ‘by committee’ ideas for issues driven by audit).

The art school and university play an important part in the wider ecosystem of this journal, in terms of academic contributors, guest editors and PhD students looking to publish new work; in supplying the varied expert peer reviewers who are integral to independent validation, giving rigour in a productive process of journal feedback to authors; and through the networks of libraries, providing the presence, readership and referencing of work for students and researchers alike. The longstanding and more global issues and dialogues around pedagogy, the art school, practice research, institutionalism, and therefore political critique, become a mainstay of subject and issue-based contributions to the journal over its lifespan that bear testament to the significance and contestations of the educational structures, networks and cultures. The journal both connects with, but also reflects on, informs and challenges the various domains of practice.

Most importantly, this journal is a site for research in, or rather through artistic practices, and now is evermore a crucial time to renew engagement with key critical dialogues emerging in the field. We can look closer to home to the many UK educational groups, associations and societies such as GLAD (Group for Learning in Art and Design), CHEAD (Council for Higher Education in Art and Design), NSEAD (National Society for Education in Art and Design), NAFAE (The National Association for Fine Art Education) that the journal has connected with in the past, both in terms of the issues and dialogues, and through individuals associated with these bodies bringing to the journal important educational and policy impacts, critiques and pedagogic enquiries.

The articles presented in this issue are a case in point, in which we find reference to a particular reading of a recent history, establishing a certain teleology through the journal's archive while at the same time giving space and voice to diversity and specialist understanding of visual art practice that must be protected from instrumental, organisational and institutional forces. Ian Biggs, the first editor of the journal, and Howard Riley, as an academic and contributor, who have both written for this issue, have engaged in important ways with a number of the aforementioned bodies and national debates over the last twenty years. We recognise the need to continue these engagements, while also looking further afield too. The recent programme of workshops, presentations, propositions and screenings that took place as part of EARN/Smart Culture Conference (European Artistic Research Network), for example, are highly pertinent to the subject of the journal. The network's publication, The Postresearch Condition (Schlager Citation2021) includes contributions, for example, from Amanda Beech and Henk Schlager (both members of Journal of Visual Art Practice's editorial board). We remain committed to reflect on the urgent debates, discussions and reflections around research carried out by artists, and the widening debates, beyond the schism of Brexit, reaching out to international territories through conferences, symposia and exhibitions that might fruitfully find the journal as a worthy destination and interlocutor.

The visual practice of the journal

We are committed to delivering a renewed focus on the visual, which includes a new strategy for the journal's cover design that affords the direct showcasing of artists’ visual practice. Fruitful discussions with the publisher have also resulted in new formats and styles for visually orientated submissions being agreed and positively supported. As such, we can give more breathing space to images and to include ‘full bleed’ and ‘double-spread’ formats. Text is also considered as a visual element, and there is room for negotiation around text and image relationships, and layout more broadly.

The appointment of Visual Essays Editor, Jane Birkin, has been central to this work, ensuring we can meet head-on the question of how we are to publish visual practice. Opportunities for artists to present their practice in the setting of an international peer-reviewed journal are indeed rare. The evolution of the practice PhD, for example, has led to the emergence of a specific group whose practice is often theoretically and literally bound to a written thesis. But this evolved relationship between theory and practice can end abruptly post-PhD, and/or leads to numerous complications and misunderstanding when entering the scramble to ‘get published’. Publishing often demands a diminution or even an elimination of practice, leaving the theory somewhat adrift. PhDs are just one group of practitioners who need space such as that provided by our journal. And, while some artists may be experienced writers and extremely adept at formatting their practice for publication, others with strong and critically-measured practices may not be, and we encourage them to come forward with their ideas for visual essays and practice research papers. We support active discussions with practitioners to help present existing work as research, and, of course, to encourage the production of significant new work for the journal.

The design and consideration of content can actively support the publication of good practice and case study materials. It is important to add, as with any academic journal, the aim is also to uphold and open-up a sustained discourse and critical space for working with, contemplating about, and influencing future practice. With these aims in mind our consideration of a future initiative, Talking Papers, allowing authors to discuss their writings and practice in relation to work published with the journal, importantly moves beyond passively providing access to one's own practice, and rather actively sharing in and building on practice research. As a process of connections, feedback and responses, the aim is that the production of new writing or works might be part of longer dialogue and can be more interrogative and accessible.

In order to better exploit the ‘visual’ in ‘Visual Art Practice’ more generally, steps are underway to refresh and/or put in place a stronger digital offering. And plans are underway to rethink the dissemination and reception of the journal outside of the traditional publishing space it currently operates within. In addition to how most will currently engage with the journal through its online interface, the hope is to offer supplementary spaces for greater visual impact (as means to jump into the main journal page and importantly the published articles). These are ambitious aims, and ones which, alongside meaningful engagement with social media, will need some care and attention, and no doubt some trial and error. One hope is to achieve these outcomes through a team of up-and-coming scholars, who can work in a distributed way to not only share in the work, but offer developmental opportunities and help re-imagine how an expanded editorial team can operate.

An Invitation to Read …

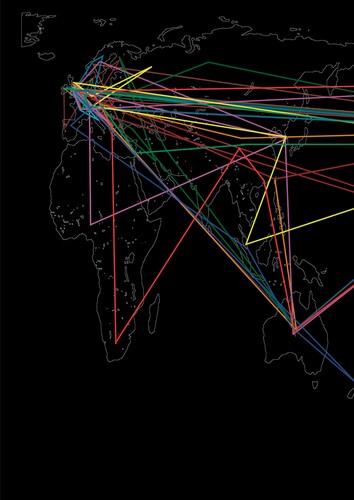

Walter van Rijn's artwork at the end of this introduction shows a mapping of the journal's production over its first 20 years, reminding us of the ensuing issues of visibility both for the journal going forward and in terms of mapping against the journal archive. The map provides us with a sense of a data flow, hinting at the temporal shifts and global nature of the journal. A critical reading of the map acknowledges it is easy to generalise or take patterns of global exchange for granted. This artwork therefore can be taken as if a composite ‘photograph’ of the Journal's data; a visualisation of the actuality of the Journal's global activity in terms of the diversity of authors and geographic spread. It gives us a starting point to strategically imagine how a more active global network might function and how we might further build a wider community that supports increased access to the journal, while also disseminating ideas back across broader communities and enriching the future archive with a more diverse scholarly record of global art practice. How might we imagine this map, then, in another 20 years? Importantly, the map, as it is currently, highlights that artists make valuable contributions about debates on globalisation, on global art practices and art production as forged through a network of global exchange, through the circuit of exhibitions, art fairs, biennales and events that are now globally ubiquitous.

Inevitably, as with any journal, a key concern is getting good content and maintaining a steady flow of high-quality material. Journal of Visual Art Practice is no different, of course. But, actually, in taking on the editorship we felt an equally important consideration (and perhaps one more pressing for a journal of practice) is also its readership. At the Woodstock Art Conference in 1952, Barnett Newman made the well-known remark that aesthetics is for artists what ornithology is for the birds. He did so to make numerous points, chief among them was a complaint that aestheticians (those writing art theory, etc.) did not advocate the value of American Art, and instead left this work in the hands of museum directors and curators. We might focus on James Elkins’ two pertinent readings of Newman's analogy:

First, it could mean birds don't understand ornithology. In that case, in a perfect world, if they could learn ornithology, they might come to understand themselves better. In the comparative analogy, that means artists could benefit from aesthetics even if they think it has nothing to do with them. It would describe the situation in which contemporary artists, critics, and historians might find that the aesthetic and anti-aesthetic actually do structure some of their practice.

Second, it could mean birds aren't well described by ornithology, that it is an insufficient explanation of birds, a deficient science. In the comparative analogy, that would imply that contemporary artistic practice and theory are essentially, perhaps deeply, independent of the terms of the aesthetic and anti-aesthetic. Even that minority of contemporary artists who feel they need to become clear about the historical precedents and conceptual foundations of their practice would not need to study the ideas discussed in this [journal]. (Elkins, Citation2013, 3)

In the context of editing a journal, we might say it is still the art world operators, not those writing for a journal such as this, that frame the value(s) of art. But, we also take Newman's remark (and Elkins’ interpretations) seriously, to remind us of the value of not just writing for, but also reading a journal such as this. This is our fourth issue as editors and we are still practising! But, equally, as outlined, we take our role in the form of a practice, one that seeks to continue to develop a collective journal practice. This introduction acts as an invitation to a wide range of authors, guest editors, board members, and reviewers to engage with the journal as it moves into its next decade. But first and foremost, we want this to be an invitation, even an enticement, to be a ‘reader’ of practice, to be a reader of the Journal of Visual Art Practice … .

Notes on full page images, in order of appearance

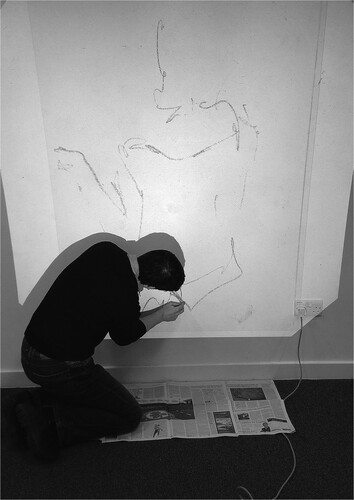

(1) Manghani (2013) You are so good as to have a theory about me which I don't at all fill out [preparation], pencil on wall.

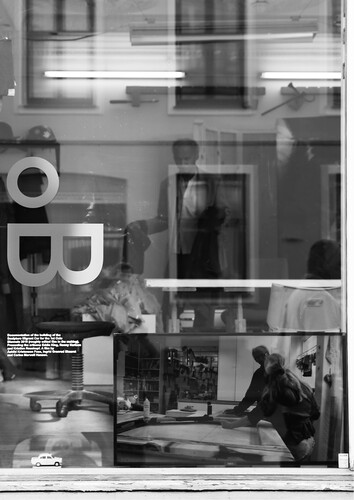

(2) D’Souza (2019) Migrant Car, installation view of temporal exhibition/production space and documentary video installation in Grünerløkka, Oslo as part of osloBIENNALEN.

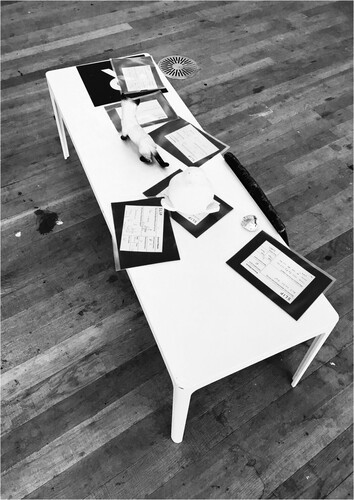

(3) Birkin (2019) SLIP, paper slips in situ at Tate Exchange.

(4) Walter van Rijn (2021) Journal Journeys.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jane Birkin

Jane Birkin is Research Fellow attached to the Data Image Lab at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton. Her research functions at the intersection of text and image, combining media culture, photo theory and techniques of the archive, with her art practice often emerging as film or performance. Her first book Archive, Photography and the Language of Administration was published by Amsterdam University Press (2021). She has performed and exhibited widely, including at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern (2019).

Ed D’Souza

Ed D’Souza is Professor of Critical Practice at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK). He is Editor of Journal of Visual Art Practice. His books include India’s Biennale Effect (2016), Barcelona Masala: Narratives and Interactions in Cultural Space (2013) and Outside India: Dialogues and Documents of Art and Social Change (2012). His work has been exhibited widely including Bergen Kunstall 3,14 (2019), osloBIENNALEN (2019), India Habitat Centre (2019), Tate Exchange, Tate Modern (2018) and Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2014).

Sunil Manghani

Sunil Manghani is Professor of Theory, Practice & Critique at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK). He is Editor of Journal of Visual Art Practice, and Managing Editor of Theory, Culture & Society. His books include Image Studies (2013), Zero Degree Seeing (2019); India’s Biennale Effect (2016) and Farewell to Visual Studies (2015). He curated Barthes/Burgin at the John Hansard Gallery (2016), along with Building an Art Biennale (2018) and Itinerant Objects (2019) at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern.

References

- Barthes, Roland. 1985. The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation, trans. by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1993. Memories of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins, trans. by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- D'Souza, Robert E., and S. Manghani 2016. India's Biennale Effect: A Politics of Contemporary Art. Delhi: Routledge.

- Elkins, James. 2013. “Introduction.” In Beyond the Aesthetic and the Anti-Aesthetic, edited by James Elkins and Harper Montgomery, 1–16. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Schlager, Henk. 2021. The Postresearch Condition. Utrecht: Metropolis M Books.

Appendix

Journal of Visual Art Practice

A catalogue of special issues, 2001–present

Twenty Years on

Editors: Jane Birkin, Ed D'Souza and Sunil Manghani – Volume 20, Issue 4, 2021

Demands of the Diagram

Editor: Claire Scanlon – Volume 20, Issue 3, 2021

Art Markets and Museums

Editor: Kathryn Brown – Volume 19, Issue 3, 2020

Transformative Education with/in Fine Art Education

Editors: Basia Sliwinska and Paul Haywood – Volume 19, Issue 1, 2020

Erosion and Illegibility of Images

Editor: Christian Mieves – Volume 17, Issue 2–3, 2018

Intimacy Unguarded

Editors: Joanne Morra and Emma Talbot – Volume 16, Issue 3, 2017

Headstone to Hard Drive

Editor: Martin Westwood – Volume 15, Issue 2–3, 2016

Hybrid Practices

Editor: Paul Coldwell – Volume 14, Issue 3, 2015

The Line

Editor: Andrew Hewish – Volume 14, Issue 1, 2015

Responses to This Is Not Art: Activism and Other Not Art

Editor: Alana Jelinek – Volume 13, Issue 3, 2014

The Art School; questioning the studio

Editor: Jill Journeaux – Volume 13, Issue 1, 2014

Contemporary Chinese art and criticality

Editors: Paul Gladstone and Katie Hill – Volume 11, Issue 2–3, 2012

Is This All There Is?

Editor: Gülsen Bal – Volume 10, Issue 2, 2012

New research practices for a new media

Editor: Lily Díaz – Volume 10, Issue 1, 2011

The Site of the Beach

Editors: Philippe Cygan and Christian Mieves – Volume 9, Issue 3, 2010

Anti-Humanist curating

Editor: Matthew Poole – Volume 9, Issue 2, 2010

The Animal Gaze

Editor: Rosemarie McGoldrick – Volume 9, Issue 1, 2010

Writing on Practice

Editors: Mick Finch and Chris Smith – Volume 8, Issue 1–2, 2009

Critique

Editor: Mary Anne Francis – Volume 7, Issue 3, 2008

Practice-Based Research

Editor: Chris Smith – Volume 7, Issue 2, 2008

Aesthetics and its objects

Editors: Francis Halsall, Julia Jansen and Tony O'Connor – Volume 5, Issue 3, 2006

Art ‘After Landscape’

Editor: Iain Biggs – Volume 5, Issue 1–2, 2006

Creative Practice Research

Editors: Katy Macleod and Lin Holdridge – Volume 2, Issue 1–2, 2002