ABSTRACT

Departing from the intention to explore Frank Gehry’s drawings serving to their own designer to grasp ideas during the process of their genesis, the article examines Frank Gehry’s concern about the revelation of the first gestural drawings and all the sketches and working models concerning the evolution of his projects, and his intention to capture the successive transformation and progressive concretisation of architectural concepts. The article also compares Gehry’s design process with that of Enric Miralles, Alvar Aalto, Bernard Tschumi, and Le Corbusier. It sheds light on Miralles, Aalto, Le Corbusier and Gehry’s interest in a holistic understanding of all the parts of an architectural project, which is expressed through their tendency to draw the different sketches concerning the same project on the same sheet of paper. At the core of Gehry’s design approach is the osmosis of function and morphology. This aspect of his design vision could be compared to Alvar Aalto’s design process. At the core of the article are the distinction between communication drawings and conceptual drawings, and Gehry’s concern about achieving an osmosis between function and morphology. The article also investigates Gehry’s use of uninterrupted self-twisting line in his sketches, exploring his intention to enhance a straightforward relationship between the gesture and the decision-making regarding the form of the building.

Introduction

This article explores Frank Gehry’s strategies of creating sketches, and the role of his preliminary sketches in the genesis of design ideas. Particular emphasis is placed on his use of the uninterrupted self-twisting line. It departs from the conviction that the concept of ‘linea serpentinata’, which was originally encountered Leon Battista Alberti’s thought and Albrecht Dürer’s Unterweysung der Messung (Dürer Citation1525), and Paul Klee’s understanding of the serpentine self-twisting line as ‘active’ (Klee Citation1953, 16) can help us comprehend Gehry’s practice of line-making. Alberti argued that architecture consists of ‘lineamenta’ – lines – and ‘materiale’ – construction materials. For him ‘lineamenta’ referred to the ‘the precise and correct outline, conceived in the mind, made up of lines and angles, perfected in the learned intellect and imagination’ (Alberti Citation1988, 7). Perceiving ‘lineamenta’ as ‘the product of human ingenuity (“ingegno”), and generative process (‘natura’) portrayed in the materiality of construction’ (Frascari Citation2011, 98), can help us understand why architectural drawings constitute essential architectural factures and not merely as visualizations.

Two key references for the question of representation in architecture are Stan Allen’s Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation (Citation2009) and Robin Evans’s The Projective Cast: Architecture and Its Three Geometries (Citation1995). What my research methodology shares with the former is the intention to understand the drawing as notation and the conviction that drawings even if they try to simulate the effects of the real experience they ‘always fall short, freezing, diminishing, and trivializing [its] […] complexity’ (Allen Citation2009, 45), while its meeting point with the Robin Evans’s research methodology is the interest in the potentialities and limits of architectural representation and in the ambiguity of the relationship between the fabrication and the interpretation of architectural drawings (Evans Citation1995, Citation1989, 34).

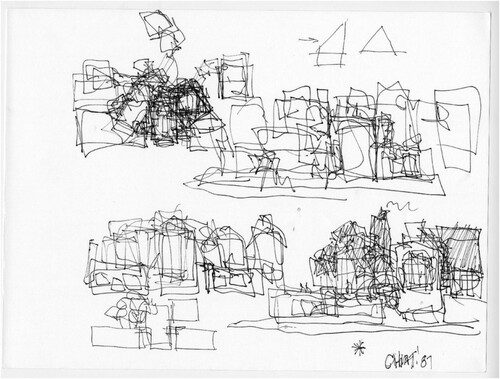

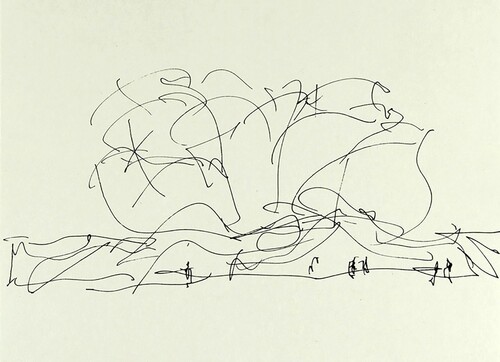

Marco Frascari’s distinction between the drawings whose function is to transmit ideas and those aiding their designer to grasp ideas during their generation process we could claim that Gehry’s line-making refers to the first category. Frascari uses the term ‘trivial’ to refer to the former and the term ‘non-trivial’ to describe the latter. At the core of this article is the analysis of the ‘non-trivial’ sketches of Frank Gehry (). Gehry has remarked regarding his ‘non-trivial’ sketches: ‘[a]s soon as [he] […] understands the scale of the building and the relationship to the site […], as it becomes more and more clear […] [he] start[s] doing sketches’ (Gehry cited in Szalapaj Citation2014, 211). According to Frascari, the ‘non-trivial’ drawings function as loci for thought. They concern ‘the very condition of architectural experimentation’ and belong ‘to a specific category of representation that makes architectural thinking possible’ (Frascari Citation2011, 98, 69, 9). Another distinction that are pivotal for this article and is at the centre of Frascari’s work is that between slow and fast drawing.

The gesture of drawing as freedom: the single uninterrupted as a thinking hand

The very force of the single uninterrupted line of Frank Gehry’s sketches lies in its capacity to evoke ‘the objective self-representation of architecture as the dream shape of the thinking hand’ (Bredekamp Citation2004, 20; Migayrou Citation2014; Lemonier and Migayrou Citation2015). A thought-provoking distinction that would be useful for better understanding Gehry’s practice of line-making is that between the hand-eye and the hand-mind. Juhani Pallasmaa reflects upon this distinction, in The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture, where he also examines the intentional and skillful value of the hand (Pallasmaa Citation2009). More specifically, Pallasmaa’s work can help us explain how Gehry progressively visualizes and reveals the decisions made during the drawing process. Gehry, through his insistence on the practice of sketching, intends to liberate his imagination. In parallel, changing the rhythm of his hand movement, he produces sketches characterized by various qualities of ‘lineamenta’ (Frascari Citation2011, 97). Moving his pen in circles and spirals, Gehry’s thinking hand, to borrow Pallasmaa’s expression in the aforementioned book (Pallasmaa Citation2009), functions as an instrument that makes possible to revolutionize the relationship between spatial perception and architectural conception. This experimentation that concerns both spatial perception and architectural conception is related to the symbolic dimension of the ‘first line to a blank surface’ and the myth of the ‘crucial first stroke’ (Bredekamp Citation2004, 11).

Georg Vrachliotis, comments about drawing as gesture, in ‘Gropius’ Question or On Revealing and Concealing Code in Architecture and Art’, drawing upon Vilém Flusser’s approach (Vrachliotis Citation2010, 77). More specifically, he refers to Flusser’s understanding of gesture as ‘a movement of the body or of the tool connected to it, for which there is no satisfactory casual explanation’ (Flusser Citation1997, 8; Flusser Citation1991, Citation1999, Citation2014). According to Flusser, ‘[t]he concept of the tool can be defined to include everything that moves in gestures and thus expresses a freedom’ (Flusser Citation1991, 122; Flusser Citation1997, Citation1999, Citation2014). Useful for understanding Gehry’s conception of drawing as gesture is Flusser’s following remark:

[t]here is no thinking that would not be articulated by a gesture. Thinking before articulation is only virtual, in other words nothing. It realises itself through the gesture. Strictly speaking one cannot think before making gestures. (Flusser Citation1991, 38; see also Flusser Citation1997, Citation1999, Citation2014; Gänshirt Citation2021, 140)

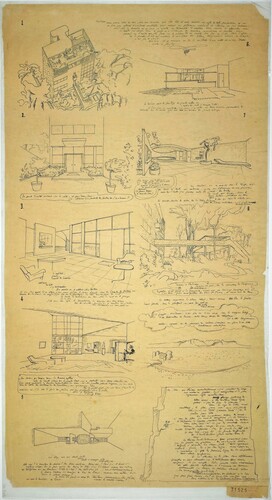

Le Corbusier, in the text ‘Où en est l’architecture?’, published in 1927 in L’architecture vivante, maintained ‘that any gesture that is not affected to varying degrees of an art potential’ (Le Corbusier Citation1927, 10). A distinction that is useful for comprehending Gehry’s conception of drawing as gesture is that between the determined gesture and the spontaneous gesture that Le Corbusier drew. Le Corbusier. As Frank Gehry, placed particular emphasis on to process of transformation of mental images into their visualisations through hand drawing. For this reason, he used sketches as dynamic and active parts of his design process and not simply as a medium for recording complete mental images. The way in which he used sketches and visual representation at every stage of the design process shows that he conceived mental images as an architectural design tool. He paid much attention to the role of mental images during the process of crystallisation of his ideas. This becomes evident when he refers to the ‘spontaneous birth (after incubation) of the whole work, all at once, at a stroke’ (Le Corbusier Citation1965; Le Corbusier Citation1960; Pauly Citation2008, 59). In the sixteenth century, Vasari echoing a Vitruvian view of drawing as a vehicle for speculative thought wrote: ‘We may conclude that design is not other than the design of a visible expression and declaration of an inner conception’ (Vasari Citation1907). The activity of translation of a spatial idea into reality was also at the heart of August Schmarsow’s approach in ‘The essence of architectural creation’. He remarked there that the ‘attempts to translate a spatial idea into reality further demonstrate the organisation of the human intellect’ (Schmarsow Citation1894, Citation1994).

Gehry’s strategies processes of producing sketches bring to mind not only the dynamic freedom revealed by Lucio Fontana’s strategies of tearing of the surface of canvases, in the sense that both aim to re-invent the very notion of gesture. ‘Fontana’s method of treating the canvas with various tools and instruments in order to emphasize the material quality of its surface’ (Sandford Citation2003, 268; Candela Citation2019). Gehry’s immediacy and spontaneity while producing sketches has also certain affinities with the gestures of liberation in Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. The use of the uninterrupted self-twistng line was also pivotal in Alberto Giacometti’s work.

Gehry's line is ‘an active participant in the act of drawing and asserts its own creative independence’ (Rosand Citation2013, 210). The gestural dimension of his line brings to mind Vilém Flusser's conception of creation as a mechanism of ‘devising ideas during the gesture of making’ (Flusser cited in Gänshirt Citation2021, 105; Flusser Citation1999, Citation2014). The ‘self-indulgence' (Foster Citation2002, 40) that characterizes Gehry's gesture of line-making challenges the conventions of illustration, promoting evocation in the sense that his sketches, instead of describing, ‘seek and evoke’ (Emmons Citation2019, 204; Costa Meyer Citation2008, 20, 26). Moreover, his ‘drawdlings’, due to the insistence on the use of the uninterrupted line, promote animateness and aliveness of the architectural form. Their animateness has to do with the fact that they invite their viewer to conceive the architectural assemblages sum of possibilities. Gehry ‘start[s] drawing […] not knowing where it is going … It’s like feeling your way along in the dark, anticipating that something will come out usually’. He is ‘a voyeur of […] [his] own thoughts as they develop’ (Gehry cited in Bettley et al. Citation2005, 65). His drawing strategies could be understood as a hand-to-eye coordination and as a mind-to-hand coordination.

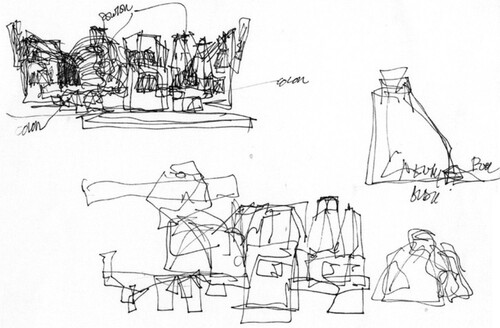

Towards a holistic view of the parts: juxtaposing the different drawings on the same sheet of paper

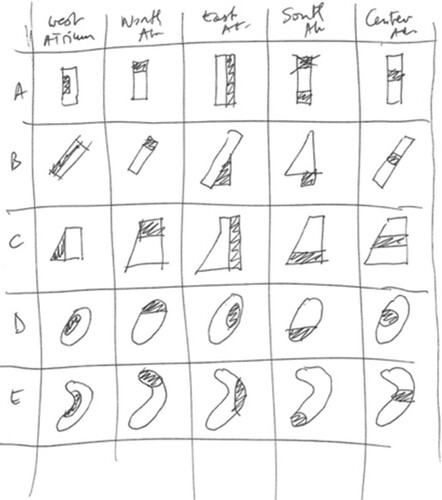

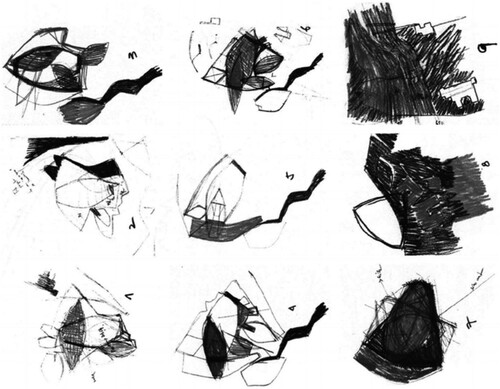

To better comprehend the tendency of Frank Gehry to challenge the hierarchies regarding the architectural composition process, it would be useful to relate his design strategies to those of other architects who also share his intention to reinvent the design process, such as Bernard Tschumi and Enric Miralles. Bernard Tschumi’s preference for the term ‘notation’ over that of ‘croquis’ is founded on his understanding of the production of sketches as rapid abstractions. The affinities between Tschumi and Gehry’s modes of linemaking are due to their common conception of ‘non-trivial’ drawings as rapid abstractions, while their dissimilarities lie in the fact that the former aims to use the smallest possible number of lines to express what he thinks, while the latter, through the production of linea serpentinata and self-twisting uninterrupted lines seeks to activate the power of his imagination. Tschumi prioritises clarity, while Gehry’s prime concern is the non-interruption of the line, which activates his imagination so as to grasp the form in its genesis. Gehry’s sketches, produced through a series of spiralling movements, capture a sum of possibilities within the same sketch. The different variations coexist within the same graphesis () (Frascari Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2017).

Figure 2. Sketch of Disney Hall exterior, The Walt Disney Concert Hall Portfolio, 2003, Frank Gehry (Canadian-born American, b. 1929). The Getty Research Institute, 2009.PR.3.

For Frascari, a brouillon is a counter drawing, which encapsulates the significance of a project, and from which other drawings may originate. Tschumi introduced the notion of ‘concept-form’, in Event-Cities 4: Concept-Form, to describe a concept generating a form or a form generating a concept, in such a way that the one reinforces the other, dissolving the distinction between the phase of construction of the mental idea and that of its transmission via its representation (Tschumi Citation2010). Simultaneously, the intensity of the first move and the status of the line as reiterated through the subsequent variations of sketches make Gehry’s ‘non-trivial’ drawings an emblematic case for penetrating the very potential of brouillons (Frascari Citation2009, Citation2017).

Tschumi’s notion of ‘concept-form’, which implies the dissolution of the distinction between the phase of construction of the mental idea and the phase of its transmission via its representation, offers the possibility to think together percept, concept and affect. For Tschumi, ‘concept-forms are diagrams without history’, are ‘autonomous from history’ only and ‘never symbolical’. They lose their ‘autonomy as soon as it is populated by reality’ (Tschumi Citation2010, 15). Tschumi’s following remark is useful for understanding how ‘concept-forms’ function as devices of genesis: ‘a concept-form begins as an abstraction, but immediately assumes a social, political or, alternatively, sensuous experiential character as soon as it is built’. In the projects presented in Event Cities 4: Concept-Form, Tschumi aimed to transform abstract devices into generators of architectural schemes, turning programmatic strategies into concepts. Through the elaboration of the notion of concept-form, he treated both concepts and forms as ‘a function of one or several program characteristics’ (Tschumi Citation2010, 15; Charitonidou Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

A parameter of Tschumi’s design approach that is note-worthy given that it is closely related to an understanding of drawings as brouillons in Frascari’s sense (Frascari Citation2009, Citation2017) and to the notion of ‘concept-form’ is Tschumi’s tendency to explore many different formal variations that can be produced if certain parameters, which are central for the design strategy for the project under consideration, are fixed, but all the other parameters are altered. In order to explore these variations, Tschumi needs to visualise them through the creation of diagrams that function comparative studies of all the possible configurations (). This visualisation technique addresses neither to the observer of the architectural drawings nor to the user of architecture, but to the architect-conceiver who uses them in order to choose and concretise his own design strategies.

Figure 3. Preliminary sketches of Bernard Tschumi that show how he tries to capture the design strategy through the ‘concept-form’. Credits: Bernard Tschumi Architects.

Figure 4. Bernard Tschumi, Richard E. Lindner Athletics Center, University of Cincinnati OH (2001–06). Comparative studies of alternative configurations of the envelope regarding the atrium ‘s permutation. Credits: Bernard Tschumi Architects.

Figure 5. Bernard Tschumi, Italian Space Agency, Rome, Italy, Competition 2000, alternative variations. Credits: Bernard Tschumi Architects.

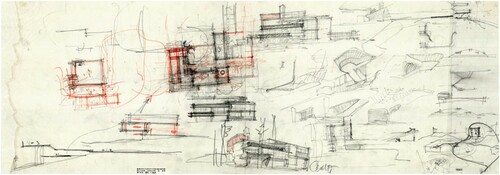

Both Enric Miralles and Frank Gehry share their interest in a holistic understanding of all the parts of an architectural project. In parallel, for both the process of sketching and representing is of pivotal importance. As Javier Fernández Contreras remarks, in the recently published book entitled The Miralles Projection: Thinking and Representation in the Architecture of Enric Miralles, at the core of Miralles’s design process is the conviction that it is impossible to dissociate the evolution of one’s architectural ideas from the development of his own system of representation () (Contreras Citation2020). Another point of convergence between Gehry’s and Miralles’s design process is their recognition of the importance of repetition and the reiterative processes. Since the early years of his career, Miralles had realised how significant is repetition for grasping and concretising architectural ideas through representation, as it becomes from his following words, which come from his PhD dissertation entitled Cosas vistas a izquierda y derecha – sin gafas (Things Seen to the Right and Left, Without Glasses):

annotation, on this sliding surface, only happens if the idea that triggers it is able to stop in its tracks, move forward in fits and starts, and be produced through repetition. (Miralles Citation1987; Contreras Citation2021, 7)

Figure 6. Enric Miralles. Sketches done for the project of the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh. 1998. Archives project folder EMBT Miralles-Tagliablue loan from © Fundació Enric Miralles.

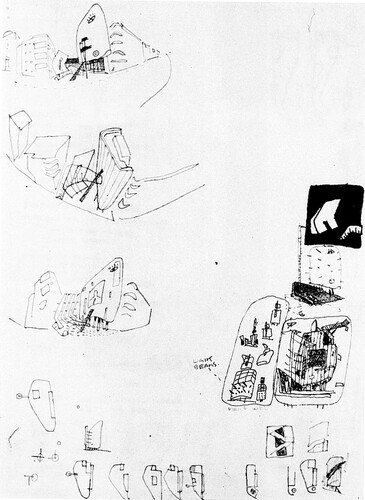

Figure 7. Sketch by Peter Wilson included in Pamela Johnston et al. (Citation1989).

Figure 8. Front cover of Pamela Johnston et al. (Citation1989).

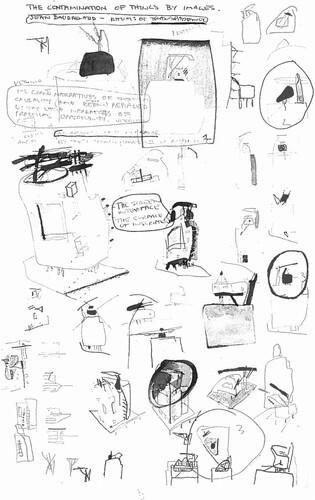

Figure 9. Sketch by Peter Wilson including the following remark: ‘the contamination of things by images’. This sketch was displayed in Pamela Johnston et al. (Citation1989).

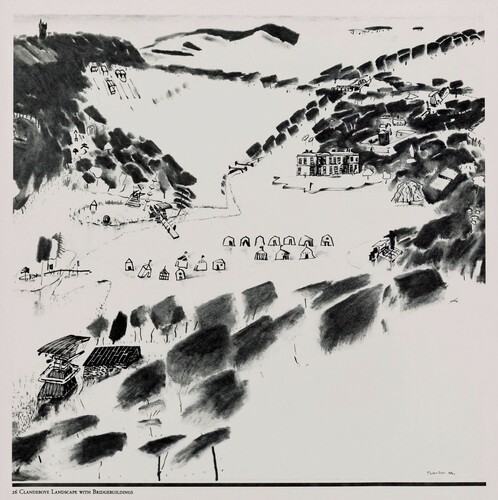

Figure 10. Drawing by Peter Wilson for Clandeboye Landscape with Bridgebuildings included in Peter Wilson (Citation1984), DM 2902.6.1 courtesy Drawing Matter Collections.

Another thought-provoking comparison would be that between Gehry's hand drawings and those of Peter Wilson, especially a sketch included in Mega XII: Peter Wilson Western Objects Eastern Fields published in 1989 in conjunction with an exhibition of original drawings, models and photographs of the work of Peter Wilson and the Architektubüro Bolles Wilson coordinated by Katherine Jacobs and held at the Architectural Association in London between 4 and 28 October 1989 (Johnston et al. Citation1989) ( and ), but also a sheet of paper with several quick sketches on it and the remark ‘the contamination of things by images’, which was also included in the aforementioned exhibition catalogue (). An insightful analysis of Wilson's drawings for Clandeboye Landscape with Bridgebuildings can be read in Mark Dorrian's recently published article in which the author relates Peter Wilson's drawing strategies to Roland Barthes's theory in Empire of Signs, interpreting Wilson's approach as ‘ideogrammic’ () (Wilson Citation1984; Barthes Citation1970, Citation1982; Dorrian Citation2021, 688).

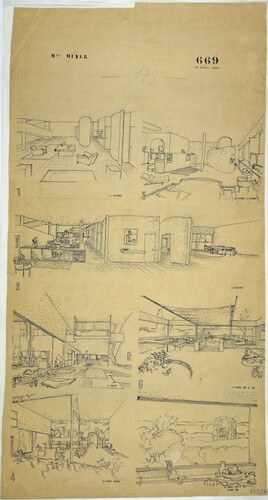

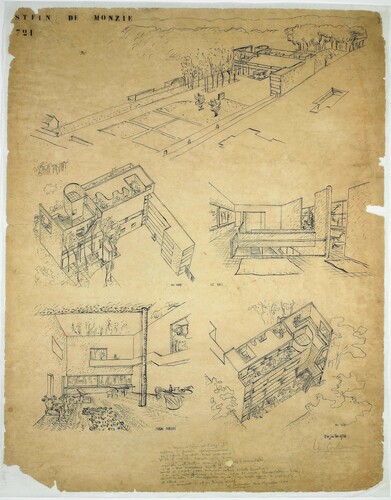

Gehry’s holistic view of the parts of the architectural assemblages and his tendency to juxtapose the different drawings on the same sheet of paper brings to mind Le Corbusier’s approach and Alvar Aalto’s approach (). Both Le Corbusier and Aalto often drew the different sketches concerning the same project on the same sheet of paper as Gehry does. A distinctive characteristic of Le Corbusier’s architectural drawings is his habit to produce drawings that are based on different modes of representation – interior and exterior perspectives, axonometric representations, plans, etc., – on the same sheet of paper. This choice is related to his definition of architecture as succession of events. For instance, this becomes evident in Le Corbusier’s choice to draw an exterior perspective, two axonometric views and two interior perspective views for Villa Stein-De Monzie an exterior perspective, two axonometric views and two interior perspective views on the same sheet of paper in July 1926 (). In 1925, Le Corbusier defined architecture as the establishment, creation of relationship between objects, or different building components. His concern about how building components are assembled should be interpreted in relation to his belief that good relationships can cause intense feelings. In Précisions, in 1930, he defined architecture as succession of events (Le Corbusier Citation1930).

Figure 12. Le Corbusier, an exterior perspective, two axonometric views and two interior perspective views on the same sheet, Villa Stein de Monzie Vaucresson, July 1926. Credits: FLC 31480, Foundation Le Corbusier, Paris.

Another case where Le Corbusier combined different modes of representation on the same sheet of paper is the Villa Meyer (1925). Le Corbusier designed seven different interior perspective views on the same sheet of paper and enumerated them (). For the same project, Le Corbusier, in order to convince Madame Meyer, drew on a second sheet of paper an axonometric view accompanied by seven perspective views – interior and exterior (). This sheet of paper was a letter he sent to Madame Meyer in 1925 and is presented in Œuvre complete 1910–1929 (Boesiger and Stonorov Citation1946, 89; Charitonidou Citation2020a) and should be interpreted in relation to his conception of the architectural promenade (Samuel Citation2010). The simultaneous use of different modes of representation in the Letter to Madame Meyer functions as a mechanism that permits a holistic view of the project. Bruno Reichlin comments on the drawings of Le Corbusier’s Letter to Madame Meyer, in his text entitled ‘Jeanneret/Le Corbusier, Painter-Architect’:

perspectives extended to the point of taking in an entire itinerary. They presuppose movable points of view, cavalier perspectives, and rapid zoom shots, from panoramic view to close-up of plan. Explanatory cartoonlike ‘bubbles’ are inserted to avoid breaking the optical continuity that the drawings suggest, and to prevent the reader from mistaking these drawings — these graphic annotations — for illusionistic renderings of the building to be built. (Reichlin Citation1997)

Frank Gehry’s drawings as reiteration: successive repetitions as a never-ending start over

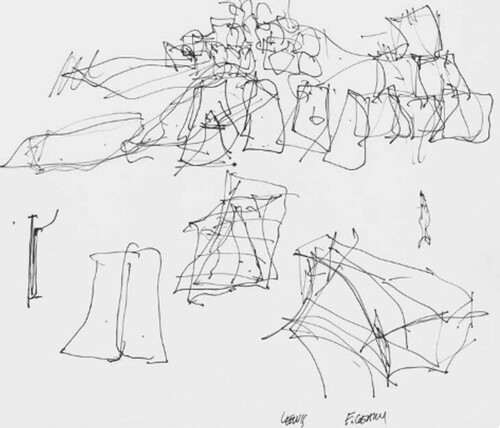

In the case of Gehry’s drawings ‘[t]here is a resonance in the ability of the viewer to trace back the line to the gesture, and to understand the transformation of this line into the architectural form’ (Lucas Citation2006, 200). The correlation of Gehry’s drawings with his ‘hand movements that seem to think as they execute lines, that circle back upon themselves, that twist and turn in a sequence of S-curves, that paraphrase central perspective’ explains their specificity and originality, as well as their capacity to ‘convey [their] […] autonomous objectivity to the observer’s imagination’ (Bredekamp Citation2017, 169). Gehry compares both his hand-to-eye coordination and his intuitive attempts to concretize his ideas through continually sketching with Michelangelo’s effort to find answers when carving his sixteenth-century sculptural series Slaves. Each of his several sketches of uninterrupted lines is like a snapshot of a continuous transformation which functions as a means to capture his imagination and mental process. Gehry’s series of sketches are based on the conviction that each of the successive drawings corresponds to a phase of a progressive concretization of his design idea. The sum of the drawings enhances ‘the training of the language that you’ve evolved’ (Isenberg Citation2009, 88). When he draws, he jumps ‘from one phase of the process to another in a way that is suggestive and open-ended’ (Lindsey Citation2001, 54).

Gehry’s endeavour to unearth the ‘perfect’ form through the incessant reiteration of his line can be observed in his note – referring to the fish, which is at the centre of his thought – that he ‘kept drawing it and sketching it and it started to become for me like a symbol for a certain kind of perfection that I couldn’t achieve with my buildings’. The fish symbolizes his desire to capture perfection and his reiterative never-ending process. As he remarks, ‘whenever [he would] […] draw something and [he] […] couldn’t finish the design, [he would] […] draw the fish as a notation’ (Gehry cited in Hartoonian Citation2012).

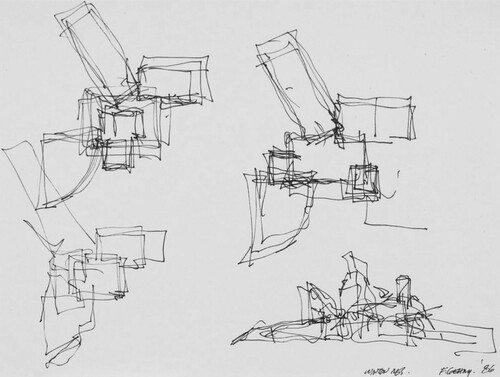

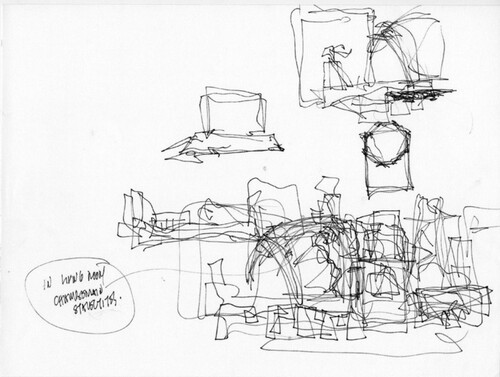

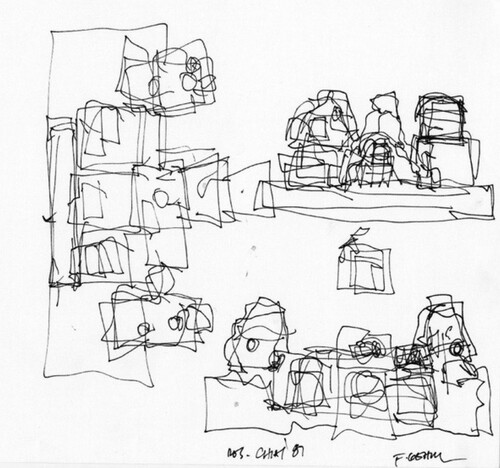

Michael Graves drew a distinction between three types of architectural drawings: the referential sketch, the preparatory study, and the definitive drawing (Graves Citation1977, Citation1978). The neologism ‘drawdling’ (Maclagan Citation2014, 55, 60, 74) is useful for better grasping the aforementioned distinction drawn by Graves. David Maclagan used the term ‘drawdling’ to describe Thom Mayne’s drawing strategy could also be used for Gehry’s line-making whose doodles are reiterated and transformed progressively through their successive repetitions as a never-ending start over. The main argument of this text is that the distinctive force of Gehry’s practice of drawing, or ‘drawdling’, lies in the way his sketches function as snapshots or instantaneous concretization of a continuous process of transformation. This becomes evident in his sketches for the Jay Chiat Residence in Sagaponeck, New York (1986) (), but also in those for the Winton Residence Guest House (1983–1987) ().

Figure 15. Frank Gehry, project sketch for Chiat Residence, Sagaponeck, New York, 1986 © Frank O. Gehry. Frank Gehry papers, Series I: Architectural Projects, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA. Digital image courtesy of the Getty Research Institute Digital Collections.

Figure 16. Frank Gehry, The Winton Residence Guest House, 1986, Felt-tip pen on white wove paper 9 × 12 inch. © Frank O. Gehry, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Frank Gehry Papers.

Figure 17. Frank Gehry, project sketch for Chiat Residence, Sagaponeck, New York, 1986 © Frank O. Gehry, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Frank Gehry Papers.

Figure 18. Frank Gehry, project sketch for Chiat Residence, Sagaponeck, New York, 1986 © Frank O. Gehry, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Frank Gehry Papers.

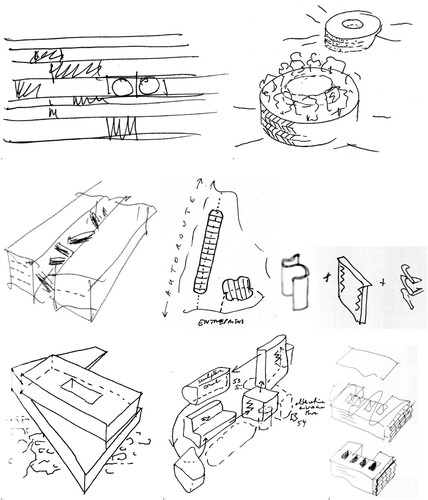

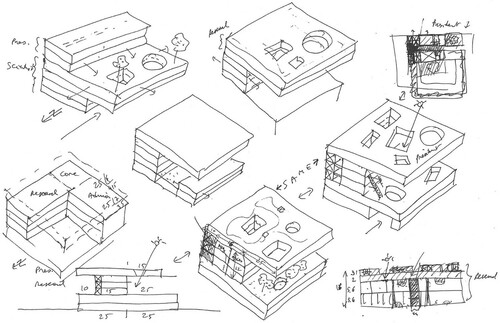

A common characteristic of Gehry’s sketches for these projects is the choice of Gehry to draw on one single sheet diverse variants of the same project both in plan and in elevation. This tendency to explore visually simultaneously the various views of a project should be interpreted in conjunction with his intention to address in a non-hierarchical way both the functional and morphological features of the building. Another trait of Gehry’s design strategies that is worth-mentioning is his tendency to assemble individual programmatic elements into a programmatic whole without restraining his design approaches through the use of conventional programmatic units. This becomes apparent in the case of the Winton Residence Guest House, where ‘the programmatic elements of the project are embodied as individual pieces and then collected together as a whole’ (Rappolt and Violette Citation2004, 46). We can understand how much importance Gehry gave to this process of assembling in an inventive way the programmatic elements in a synthetic whole in his sketches, which constitute numerous alternatives of assembling these elements.

The combination of several versions of the same project on one sheet of paper is a characteristic of many of his sketches for various projects, and invites the viewers to interpret his drawings as nodes of a complex system. This system consists of reiterated captures through single-gesture sketches, and helps us grasp their strength not only as an application of brainstorming tools to the design process, but also as dynamic semiotic mechanisms. Seeing these drawings, one understands that, in Gehry’s case, it is not the single drawing that matters, but the act or the practice of drawing that enables him to proceed from spontaneity towards concretisation. The choice of Gehry to represent on the same sheet of paper the different drawings of the same building goes hand in hand with his intention to grasp in a holistic way what would be the impact of a specific decision concerning the form-making of a building for all the views of the building and its plans.

The juxtaposition of the different drawings on the same sheet of paper makes the process of brainstorming into a tool allowing the architect to reach beyond the limits of conventional, static modes of representation. In parallel, it reveals Gehry’s wish to develop a holistic view of all the aspects of the project, and his care about the relationships of the components. The way he represented the project goes hand in hand with his intention to promote the dynamic relationships of the components of the building. Although the program of the Winton Residence Guest House concerned the grouping of one-room buildings differentiated by cracks, Gehry’s experimentation shows that even with a relatively simple program it is possible to produce complex spatial qualities. In his drawings, one can easily understand that the main challenge for him was the creation of effectual relationships between the different components. His continuous line-making, the overlapping of the outlines of different volumes and his choice to represent the assemblage of different components of the buildings from different viewpoints are all strategies that serve to convert Gehry’s ‘drawdlings’, into a mechanism capable of applying brainstorming. This does not only concern the sculptural qualities of the building, but, more importantly, contributes to the fusion of the different programmatic entities into a complex system of movements throughout the building.

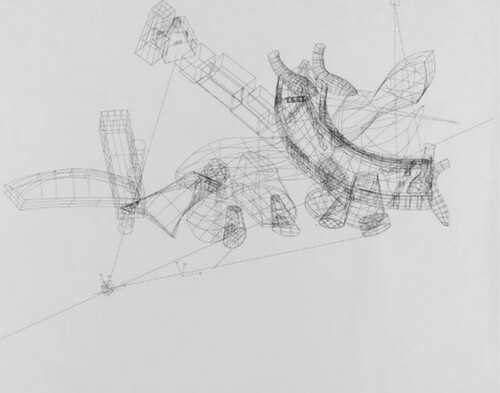

As Jean-Louis Cohen reminds us, Gehry’s ‘design process changed significantly during 1991 with the introduction of digital tools, coupled with the systematic use of models’. Two projects in the design process of which this reorientation becomes apparent are the Peter Lewis Residence (1985–1995) in Lyndhurst, Ohio and the Bilbao Guggenheim. However, ‘Gehry has continued to rely on sketches, but models – often schematic and rapidly made – have come to play the exploratory role they played for him during his early years of practice’ (Cohen Citation2020, 16). Despite the fact that the unbuilt Lewis Residence is more known for its use of computer software to render and fabricate the model’s sculptural elements, the sketches that Gehry produced for it are also characterised by the intention to conceive the sculptural form as an assemblage. This project is related to the shift of Gehry’s design processes towards a new phase based on the extensive use of digital tools and computer-aided three-dimensional interactive application software such as CATIA 3D model, which was used in order to produce perspective views ( and ) (Charitonidou Citation2021b).

Figure 19. Frank O. Gehry, Peter Lewis Residence in Lyndhurst, Ohio, 1985–1995 © Frank O. Gehry, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Frank Gehry Papers.

Figure 20. Frank O. Gehry & Associattes, Peter Lewis Residence in Lyndhurst, Ohio, 1985–1995. Perspective view produced using a CATIA 3D model, 1994. Electrosttatic print on paper, 127 × 91.4 cm © Frank O. Gehry, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Frank Gehry Papers.

Gehry also places particular emphasis on the combination of drawings and physical models during the design process. In most of the cases the design process evolves according to the following sequence: firstly. Gehry produces some preliminary sketches, then his assistants fabricate a physical model based on his sketches and Gehry creates more drawings based on this spiral process. Since the late 1980s and especially since the design of Lewis Residence to the physical working models that are used as an important step during the preliminary design process has been added the extensive use of digital 3D models, which are produced taking as their point of departure Gehry’s initial sketches. What is at the centre of Gehry’s design process is ‘[t]he incessant feedback loops between sketches, three-dimensional computer simulations, built models and engineering drawings’ (Lynn Citation2017, 295).

The osmosis of functional and morphological aspects of architecture: addressing simultaneously function and form through sketching

Several interpretations of Frank Gehry’s approach place particular emphasis on the morphological aspects of Gehry’s design thinking, underestimating the significance of his interest in the functional issues concerning architectural design. However, his use of the single uninterrupted line function not only as a device serving to explore the buildings’s morphology, but most importantly as a tool serving to investigate simultaneously the functional and the morphological aspects of architecture. In this sense, Gehry’s sketches constitute a mechanism helping him to achieve an osmosis between function and form. Moreover, through the juxtaposition of the different sketches concerning the same building on a single sheet of paper, as Le Corbusier, Gehry often produces different sketches concerning the same building on the same sheet of paper. Viewing his sketches, we can understand that he conceives the plans, the views and the sections concerning his projects in a holistic way. As Jean-Louis Cohen remarks, Gehry's design strategies are based not only on an ‘extensive research for exterior form begin, using models of different scale', but more importantly on a 'quasi-functionalist phase', which has a central place in the process, and is related to the act of 'dissecting programmatic elements into singular components, and then reassembling them to adjust for hierarchies and adjacencies' (Cohen Citation2020, 18).

At the core of Gehry’s design approach is the osmosis of function and morphology. This aspect of his design vision could be compared to Alvar Aalto’s design process. Aalto shed light on the ‘innumerable apparently uniform protocells’ of blossoms, highlighting that this variety should be the model for what he called ‘flexible’ or ‘elastic’ standardization. Aalto also undescored that thanks to their quantity ‘the cells […] [permit] the most extraordinary variety in the linkage of cells’ (Aalto 1941 in Schildt Citation1997, 154) Aalto’s humanistic understanding of functionalism and his intention to tackle simultaneously the morphological and functional issues concerning architectural and industrial design through the concept of ‘flexible standardisation’ (Charitonidou Citation2020c) brings to mind Gehry’s concern about addressing function and morphology at the same time, challenging the conventional hierarchies of the design process. More specifically, Aalto’s admiration for nature and the variety that one can encounter in nature, such as in flowers and trees, and his use of uninterrupted curvilinear lines in the framework of his endeavour to bring to the design process the variety encountered in nature has certain affinities with Gehry’s use of self-twisting line when addressing through his sketches both functional and morphological issues. Gehry’s visit to Aalto’s office in 1972 should be taken into account when we try to understand the impact of Aalto on Gehry’s design thinking (Abel Citation2007, 258; Goldberger Citation2015, 181). Gehry has also remarked: ‘I went to a lecture at the University of Toronto by the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, and I’ve never forgotten it’ (Isenberg Citation2009, 14).

Gehry’s drawings are the outcome of several energetic gestural shorthands, and it is exactly their lack of precision that makes them capable of generating ideas and of triggering the conceptual process to further evolutions. They are ‘characterized by a sense of off-hand improvisation, of intuitive spontaneity’, which is reinforced by their capacity to ‘convey no architectural mass or weight, only loose directions and shifting spatial relationships’ (Szalapaj Citation2014, 212). At the core of Gehry’s conceptual strategies is the intention to go beyond the tendency of architects to design first the contour of a building and then divide the space into its units, which correspond to the different functions. In his sketches for the Winton Residence Guest House drawn around 1983, he tried to address the design of the building in way that shows his holistic conception of architecture. The main design gesture of Gehry’s proposal for this project, which was the extension of a housing unit house designed by Philip Johnson in the early 1950s, was the grouping of a series of forms around a tall central living space. Departing from his desire to challenge the conventional way of designing a plan, Gehry started sketching from the centre of a building towards its contour, conceiving the plan as an assemblage of the functional units of the building. His quick sketches helped Gehry bring these different units into an assemblage. Useful for understanding the significance of functional aspects for Gehry’s design process are his following remark regarding this project:

Solving all the functional problems is an intellectual exercise […] And I make a value out of solving all those problems. Dealing with the context and he client and finding my moment of truth after I understand the problem. If you look at our process […] you see models that show the pragmatic solution to the building without architecture. Then you see the study models that go through leading to the final scheme. We start with shapes, sculptural forma. Then we work into the technical stuff. (Rappolt and Violette Citation2004, 52)

The art scene in Los Angeles in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s had an important impact on Gehry's design process (Fallon Citation2014). The artists that influenced Gehry include Wallace Berman, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, Kenneth Price, Larry Bell and Ed Ruscha, and Jasper Johns among others (Cohen Citation2020). Gehry visited numerous exhibitions at the Ferus Gallery, which was established by Ed Ruscha and Edward Kienholz in 1957, and the Dwan Gallery. Gehry's interest in the prosaic features of Los Angeles as cityscape (Cohen Citation2020, 30) should be interpreted in relation to his admiration for the work of Ed Ruscha and Edward Kienholz, and to the fact that Gehry designed Ed Ruscha's house. To better grasp Gehry's fascination with the art scene, we can read his following words:

I came at architecture through fine art, and painting is still a fascination to me. Paintings are a way of training the eye. You see how people compose a canvas. The way Brueghel composes a canvas, or Jasper Johns. I learned about composition from their canvases. I picked up all those visual connections and ideas. (Gehry in Rappolt and Violette Citation2004, 7)

Despite the fact that he started intensively using the black-and-white fast and loose doodles as the mechanism par excellence of brainstorming in the 1980s, he was already using methods based on abstractness from as early as the 1960s, as can be seen in his initial sketches for Danziger studio/residence (1964–1965), whose abstractness and disposition of different drawings on the same sheet of paper reminds us of one of his initial sketches for his own residence in Santa Monica (1978). Gehry himself relates ‘the shift from orthogonal to perspectival’ in his work to his encounter with the American Abstract Geometric painter Ron Davis, for whom Gehry designed a studio/residence in Malibu (1968–72) and who at the time of their first exchanges ‘was doing paintings that were about perspectival constructions’. What intrigued Gehry was the fact that Davis ‘could draw but he could not make them; he could not turn them into three-dimensional objects’ (Gehry cited in Zaera Polo, Cecilia and Levene Citation2006, 19).

Gehry’s avoidance of pictorial drawings brings to mind Walter Benjamin’s critique of the pictorial construction of architecture (Benjamin Citation1999, 669–670). Benjamin employed the distinction between optical and tactical, drawing upon Alois Riegl’s approach and art historian Carl Linfert’s interpretation of the latter, and shed light on how drawings can promote a multi-perspectival perception of space and to render explicit the limits of central perspective. Gehry’s attempts to grasp the form as an organic continuum through fast hand-drawing could be seen as a case that elucidates Benjamin’s arguments. They overcome the restraints of perception when space is represented using a single viewpoint, as is the case in central perspective.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari's understanding of assemblage, in A Thousand Plateaus (Guattari and Deleuze Citation2007, Citation1980; Deleuze Citation1983, Citation1985, Citation1986, Citation1989), and Robert Rauschenberg's work, and particularly Combines, are useful for comprehending Gehry's line-making. Deleuze and Guattari mention, that an 'assemblage has neither base nor superstructure, neither deep structure nor superficial structure; it flattens all of its dimensions onto a single plane of consistency upon which reciprocal presuppositions and mutual insertions play themselves out' (Guattari and Deleuze Citation2007, 90; Citation1980; Deleuze Citation1983, Citation1985, Citation1986, Citation1989). Gehry's sketches could be understood as assemblages in the sense that they are characterized by a non-hierarchical order. As Martino Stierli remarks, in Montage and the Metropolis: Architecture and the Representation of Space, the “assemblage […] stands for a non-hierarchical order where objects/thoughts are placed next to each other rather than vertically aligned” (Stierli Citation2018, 272). Gehry had the opportunity to see Rauschenberg's Combines at the Ferus Gallery in 1962 (Cohen Citation2020). The fact that Rauschenberg's Combines 'painting(s) playing the game of sculpture' (Tomkins Citation2005) brings to mind Gehry's kinaesthetic perception of architecture and the sculptural qualities of his projects.

Conclusion or towards a kinaesthetic perception of architecture: speed, freshness, abstractness and spontaneity

As key issues of Frank Gehry’s use of uninterrupted line, the article identified the following: firstly, the enhancement of a straightforward relationship between the gesture and the decision-making regarding the form of the building; secondly, its capacity to render possible the perception of the evolution of the process of form-making; thirdly, the way the use of uninterrupted line is related to the function of Gehry’s sketches as indexes referring to Charles Sanders Peirce’s conception of the notion of ‘index’; and, finally, how Gehry’s sketches enhance a kinaesthetic relationship between action and thought. Gehry’s conviction that he thinks moving the pen leads to the idea that his drawings ‘keep up with the mental aberrations of a brainstorm’ (Lindsey Citation2001, 54, 211, 52–53; Charitonidou Citation2021a) thanks to the fact that they are done quickly and semi-automatically. The speed and looseness of their production in almost a single gesture corresponds to the architect’s desire to grasp a ‘meaningful randomness’, and to translate ‘the functional demands of a design brief into a graphic form of nonlinear logic’ (Edwards Citation2008, 29). Gehry’s method as ‘in the series of sketches [for the Guggenheim] […] ranges from wielding the pen with total control to nearly letting the lines flow by themselves, fluid, mobile, punctuated by little jolts, starts, and stops’ (van Bruggen Citation1998, 71).

Gehry’s sketches are known for their ‘spontaneity of impulse’, and their ‘essence of ineffable’, and the way they reinvent the tension ‘between a system of familiar Platonic solids and a set of spontaneous forms that riff but do not ape this set of familiars’ (Sorkin Citation1999, 28–29). Thanks to this unresolved suspension, they convey a fluidity and a tactile sense, offering a terrain helping him to capture the form of the building, struggling to ‘“find the building” within his drawings’ (Emmons Citation2019, 204). Gehry’s freehand sketches function as a device permitting him to stimulate not only visual memory, but also the kinaesthetic relationship between action and thought. An important role for shaping a perception of architecture play the speed, freshness, abstractness and spontaneity of his sketches. In other words, through his non-trivial sketches, Gehry manages to build a kinaesthetic approach towards architecture, breaking the conventional dichotomy between thought and representation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianna Charitonidou

Dr. ir. Marianna Charitonidou is an architect, spatial planner, curator, educator and theorist and historian of architecture and urban planning. She is Postdoctoral Researcher at the Faculty of Art History and Theory of Athens School of Fine Arts, where she is conducting a postdoctoral research project entitled ‘Constantinos A. Doxiadis and Adriano Olivetti's Post-war Reconstruction Agendas in Greece and in Italy: Centralising and Decentralising Political Apparatus’. She also conducted a postdoctoral project entitled ‘The Travelling Architect's Eye: Photography and the Automobile Vision’, which will be shortly published as a book, at the Department of Architecture of ETH Zurich, and a postdoctoral project entitled ‘Architecture between Nature and Archaeology: A Transnational and Altermodern Investigation of the Image of Greece’ at the School of Architecture of the National Technical University of Athens. Dr. ir. Charitonidou was the curator of an exhibition entitled ‘The View from the Car: Autopia as a New Perceptual Regime’ at the Department of Architecture of ETH Zurich (https://viewfromcarexhibition.gta.arch.ethz.ch). In September 2018, she was awarded a Doctoral Degree all’unanimità from the National Technical University of Athens. In her PhD dissertation ‘The Relationship between Interpretation and Elaboration of Architectural Form: Investigating the Mutations of Architecture’s Scope’ (jury: J.-L. Cohen, B. Tschumi, G. Parmenidis, P. Ciorra, C. Moraitis, K. Tsiambaos, P. Tournikiotis), which she is currently editing into two books. She also holds a MPhil in History and Theory of Architecture from the School of Architecture of the National Technical University of Athens (2013), a Master in Science in Sustainable Environmental Design from the Architectural Association in London (2011), and a Master in Architectural Engineering at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (2010). She was a Visiting Research Scholar at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (invited by Prof. Bernard Tschumi) and the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University (invited by Prof. Jean-Louis Cohen), the École française de Rome (2016–2017 & 2017–2018), and resident at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) for her project ‘The modes of representation of Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, Aldo Rossi and Bernard Tschumi: the ‘observer’ vis-à-vis the strategies of de-codification’ (Doctoral Students Grant Program 2018). She has presented her research at many international conferences (more than 70) and has published numerous articles and chapters in scientific peer-reviewed journals and edited volumes focused on history and theory of architecture and urban planning and aesthetics and social sciences. Website: https://charitonidou.com.

References

- Abel, Chris. 2007. Architecture, Technology and Process. London; New York: Routledge.

- Alberti, Leon Battista. 1988. On the Art of Building in Ten Books. Translated by Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, and Robert William Tavernor. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Allen, Stan. 2009. Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation. London: Routledge.

- Barthes, Roland. 1970. L'Empire Des Signes. Geneva: Skira.

- Barthes, Roland. 1982. Empire of Signs. Translated by Richard Howard. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1999. Rigorous Study of Art. In Selected Writings, 1927–34. Translated by Thomas Y. Levin and edited by Michael W. Jennings et al., 669–670. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

- Bettley, Alison, et al., ed. 2005. Operations Management: A Strategic Approach. London: Sage Publications.

- Boesiger, Willy, and Oscar Stonorov, eds. 1946. Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret: Œuvre complète, 1910–1929, Vol. 1. Zurich: Éditions d’architecture Erlenbach.

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2004. “Frank Gehry and the Art of Drawing.” In Gehry Draws, edited by Mark Rappolt and Robert Violette, 11–28. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2017. Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency. Boston; Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Charitonidou, Marianna. 2020a. “Architecture's Addressees: Drawing as Investigating Device.” villardjournal 2: 91–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv160btcm.10.

- Charitonidou, Marianna. 2020b. “Simultaneously Space and Event: Bernard Tschumi's Conception of Architecture.” ARENA Journal of Architectural Research 5 (1): 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/ajar.250.

- Charitonidou. Marianna. 2020c. “László Moholy-Nagy and Alvar Aalto's Connections: Between Biotechnik and Umwelt.” Enquiry The ARCC Journal for Architectural Research 17 (1): 28–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.17831/enq:arcc.v17i1.1080.

- Charitonidou, Marianna. 2021a. “Frank Gehry's Self-Twisting Uninterrupted Line: Gesture-Drawings as Indexes.” Arts 10 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010016.

- Charitonidou, Marianna. 2021b. “Vers une écosophie des pratiques architecturales et urbaines.” Ligeia 2: 5–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/lige.189.0005.

- Candela, Iria, ed. 2019. Lucio Fontana. On the Threshold. New York: Metropolian Museum of Art.

- Cohen, Jean-Louis. 2020. Frank Gehry Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings Volume One, 1954–1978. Paris: Cahiers d’art.

- Contreras, Javier Fernández. 2020. The Miralles Projection: Thinking and Representation in the Architecture of Enric Miralles. San Francisco, CA: Oro Editions.

- Contreras, Javier Fernández. 2021. “Annotation as Review: Graphic Thinking in Enric Miralles.” PhD Thesis. Architecture and Culture. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/20507828.2021.1946746.

- da Costa Meyer Esther. 2008. Frank Gehry: On Line. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1983. Cinéma 1, L’image-mouvement. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1985. Cinéma 2, L’image-temps. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1986. Cinema I: The Movement-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. London; New York: Bloomsburry Academic

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1989. Cinema II: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. London; New York: Bloomsburry Academic.

- Dorrian, Mark. 2021. “Peter Wilson in the Empire of Signs.” The Journal of Architecture 26 (5): 688–709. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2021.1942135.

- Dürer, Albrech. 1525. Underweysung Der Messung. Nuremberg: Hieronymus Andreae.

- Edwards, Brian. 2008. Understanding Architecture Through Drawing. New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Emmons, Paul. 2019. Drawing Imagining Building: Embodiment in Architectural Design Practices. London; New York: Routledge.

- Evans, Robin. 1989. “Architectural Projection.” In Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation. Works from the Collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, edited by Eve Blau and Edward Kaufman, 19–35. Montreal; Cambridge, Mass.; London: Canadian Centre for Architecture/The MIT Press.

- Evans, Robin. 1995. The Projective Cast. Architecture and Its Three Geometries. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Fallon, Michael. 2014. Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s. Berkeley: Counterpoint Press.

- Flusser, Vilém. 1991. Gesten: Versuch einer Phiinomenologie. Dusseldorf: Bollmann.

- Flusser, Vilém. 1997. Gesten. Versuch einer Phänomenologie. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

- Flusser, Vilém. 1999. The Shape of Things: A Philosophy of Design. London: Reaktion.

- Flusser, Vilém. 2014. Gestures. Minneapolis: University of Minnessota Press.

- Foster, Hal. 2002. Design and Crime: (and Other Diatribes). London; New York: Verso.

- Frascari, Marco. 2009. “Lines as Architectural Thinking.” Architectural Theory Review 14: 200–212.

- Frascari, Marco. 2011. Eleven Exercises in the Art of Architectural Drawing: Slow Food for the Architect’s Imagination. London; New York: Routledge.

- Frascari, Marco. 2017. Marco Frascari’s Dream House: A Theory of Imagination. Edited by Federica Goffi. London: Routledge.

- Gänshirt, Christian. 2021. Tools for Ideas: Introduction to Architectural Design. Expanded and updated edition. Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhäuser.

- Goldberger, Paul. 2015. Building Art; the Life and Work of Frank Gehry. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Graves, Michael. 1977. “The Necessity for Drawing: Tangible Speculation.” Architectural Design 47: 384–393.

- Graves, Michael. 1978. “Referential Drawings.” Journal of Architectural Education 32 (1): 24–27.

- Guattari, Felix, and Gilles Deleuze. 1980. Capitalisme et Schizophrénie II: Mille Plateaux. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit.

- Guattari, Felix, and Gilles Deleuze. 2007. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translation and forward by Brian Massumi. London; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hartoonian, Gevork. 2012. Architecture and Spectacle: A Critique. London: Ashgate.

- Johnston, Pamela, Dennis Crompton, Mark Vernon-Jones, Susan Morris, Annie Bridges, Stuart Smith, Marilyn Sparrow, Dominique Murray, and Natasha Edwards. 1989. Mega XII: Peter Wilson Western Objects Eastern Fields. London: AA Publications.

- Isenberg, Barbara, ed. 2009. Conversations with Frank Gehry. New York: Knopf.

- Klee, Paul. 1953. Pedagogical Sketchbook. Translated by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

- Le Corbusier. 1927. “Où en est l’architecture?” In L’architecture vivante, edited by Jean Badovici, 7–11. Paris: Editions Albert Morancé.

- Le Corbusier. 1930. Précisions sur un état présent de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme. Paris: Éditions Crès.

- Le Corbusier. 1960. Creation is a Patient Search. New York: Praeger.

- Le Corbusier. 1965. Textes et dessins pour Ronchamp, Forces Vives. Translated by Le Corbusier. 1989. Texts and Sketches for Ronchamp, Ronchamp.

- Lemonier, Aurélien, and Frédéric Migayrou, eds. 2015. Frank Gehry. Los Angeles: LACMA.

- Lindsey, Bruce. 2001. Digital Gehry: Material Resistance Digital Construction. Basel; Boston; Berlin: Birkhäuser.

- Lucas, Raymond, et al. 2006. “The Sketchbook as Collection: A Phenomenology of Sketching.” In Recto Verso: Redefining the Sketchbook, edited by Angela Bartram, Nader El-Bizri, and Douglas Gittens, 191–206. London; New York: Routledge.

- Lynn, Greg. 2017. “Going Native: Notes on Selected Artifacts from Digital Architecture at the End of the Twentieth Century.” In When is the Digital in Architecture, edited by Andrew Goodhouse, 279–334. Berlin; Montreal: Sternberg Press/Canadian Centre for Architecture.

- Maclagan, David. 2014. Line Let Loose: Scribbling, Doodling and Automatic Drawing. London: Reaktion.

- Migayrou, Frédéric, ed. 2014. Frank Gehry. The Fondation Louis Vuitton. Orléans: Hyx.

- Miralles, Enric. 1987. “Cosas vistas a izguierda y derech (sin gafas).” PhD thesis, First Version. COAC library D-27317.

- Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2009. The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Pauly, Danièle. 2008. The Chapel at Ronchamp. Basel: Fondation Le Corbusier.

- Rappolt, Mark, and Robert Violette, eds. 2004. Gehry Draws. Cambridge: Mass.: MIT Press.

- Reichlin, Bruno. 1997. “Jeanneret/Le Corbusier, Painter-Architect.” In Architecture and Cubism, edited by Eve Blau and Nancy J. Troy, 195–218. Montreal; Cambridge, Mass: Centre for Architecture; The MIT Press.

- Rosand, David. 2013. “Time Lines.” In Moving Imagination: Explorations of Gesture and Inner Movement, edited by Helena de Preester, 205–220. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Samuel, Flora. 2010. Le Corbusier and the Architectural Promenade. Birkhäuser.

- Sandford, Mariellen, ed. 2003. Happenings and Other Acts. New York; London: Routledge.

- Schildt, Göran, ed. 1997. Alvar Aalto in his Own Words. Translated by Timothy Binham. New York: Rizzoli.

- Schmarsow, August. 1894. Das Wesen der architektonischen Schoepfung. Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann.

- Schmarsow, August. 1994. “The Essence of Architectural Creation.” In Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873–1893, edited by Robert Vischer, Harry Francis Mallgrave, and Eleftherios Ikonomou, 281–297. Santa Monica, CA: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities.

- Sorkin, Michael. 1999. “Frozen Light.” In Gehry Talks: Architecture + Process, edited by Mildred Friedman, 29–39. New York: Rizzoli.

- Stierli, Martino. 2018. Montage and the Metropolis: Architecture and the Representation of Space. London; New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Szalapaj, Peter. 2014. Contemporary Architecture and the Digital Design Process. London; New York: Routledge.

- Tomkins, Calvin. 2005. “Everything in Sight: Robert Rauschenberg's New Life.” The New Yorker, May 23, 68–77.

- Tschumi, Bernard. 2010. Event-Cities 4: Concept-Form. Cambrige, Mass: The MIT press.

- van Bruggen, Coosje. 1998. Frank O. Gehry: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications.

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1907. Vasari on Technique. New York; London: E. P. Dutton & co/J. M. Dent & Company.

- Vrachliotis, Georg. 2010. “Gropius’ Question or On Revealing and Concealing Code in Architecture and Art.” In Code Between Operation and Narration, edited by Andrea Gleiniger and Georg Vrachliotis, 75–89. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Wilson, Peter. 1984. Bridgebuildings + The Shipshape. London: Architectural Association.

- Zaera Polo, Alejandro, Fernando Márquez Cecilia, and Richard C. Levene. 2006. “Frank. O. Gehry: Still Life.” In Frank Gehry, 1987–2003, 12–42. Madrid: El Croquis.