ABSTRACT

This article arises from a collaboration between an art historian and a curator in forming an exhibition of work by artist Sally Madge, drawn from a long-accumulated collection of artworks and related materials existing in her basement studio, thereafter housed in a storage container on the outskirts of Newcastle upon Tyne in the North of England. The text is located within evolving discourses on both the curatorial and educational ‘turns’ in exhibition making and knowledge production, and perceptions of the gallery as a place of shared social and self-determined generative engagement. Emphasising relational interconnectedness, the curation underlines a border-crossing collapsing of categories and hierarchies. The nature of Madge’s own practice and the liminal sites she worked in throughout her life reflect a parallel artistic, political and ecological concern for creatively crossing and defying borders and boundaries. What emerges is a dialogue between artist, curator and art historian on questions of transformation and re-representation through the relations between site, studio, archive and gallery.

Introduction

The context for this article is a collaboration between an art historian, Ysanne Holt, and a curator, Matthew Hearn, in forming the exhibition Sally Madge: Acts of Reclamation (Citation2021), staged in the gallery of Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne in the north of England. Sally Madge trained initially in ceramics at The Central School of Art and Design in London in the late 1960s and later in Fine Art in Newcastle. She developed a consistently experimental and multidisciplinary practice. For much of her career she lectured in the School of Arts, Design and Media at the University of Sunderland, first in Art Education and later in Fine Art and Performance. From the late 1980s Madge regularly showed work in the form of site-specific installation, in group and individual exhibitions. She was highly active within regional arts networks and on boards of contemporary art galleries and was a much – valued friend and supporter of young and developing artists. In November 2020, Sally Madge passed away suddenly after a short battle with Covid19, leaving behind the accumulations of a diverse artistic career spanning four decades.

To develop the exhibition, we sifted through an extraordinary collection of documents, photographs, sketchbooks, and a catalogue of artworks and related artefacts, all evidence of a life’s work as stored in Madge’s basement studios and throughout the house in Newcastle in which she lived during those decades. Latterly this body of materials had been boxed-up, amalgamated and housed in a rented shipping container. In this shifting state of transition, it was (and is) in process of becoming an archive. The issue was how best to reflect core themes of a body of work that ranged across installation, video, performance, sculpture, ceramics and painting, and a practice that spanned and magpied various roles from the collector to the provocateur, the wanderer, the onlooker, the maker. As we explore, political imperatives underlined such an open, inclusive, ultimately transgressive practice.

Since the early 1990s discourse around the ‘curatorial’ function in exhibition making and knowledge production has continually brought into question the different agencies and authorities of the curator and the instrument of the gallery. We have seen a shift in understanding from the exhibition space as a monoculture – a site of fixed ideologies and instruction – to an emancipated position, following the ‘educational turn’ (Rogoff Citation2008), as a place of shared social and self-determined generative engagement.

Halfway between Sally Madge’s house in the centre of the city and Northumbria’s Gallery North is the Hatton Gallery, long connected with Newcastle University. Here, a section of Kurt Schwitters ‘Merz’ wall is installed. This celebrated work, in its present location since 1966, continues to promote discussion and debate around the contingent status of objects. In ways comparable to Madge’s own sense of material play, Schwitters’ presentations and combinations of ordinary objects demand the collapsing of hierarchies of materials and the recognition of the ability of ‘things’ to speak out both individually and collectively, to harmonise and produce disquiet. By allowing all forms of material to possess equal agency and to disavow themselves of associative meaning Schwitters pre-empts what has been defined as the ‘archival turn’ in art. In the gallery context, when objects, artefacts and documents are all afforded equal status we see a further disintegration of the categories: art and artefact; high and low; practice and documentation; author and interpreter. Madge’s own practice explored these and similar junctures, where binary logic collapsed and identities cross-contaminated: where encounters were unusual. And, indeed, Madge created work in 2011 at the Elterwater Merz Barn in Langdale – set up by Schwitters in 1946 after his escape from Nazi Germany to the Lake District – in which a photographic image of Schwitters’ face was printed on a large translucent fabric banner hanging from a tree’s branch to blow in the breeze near the barn.

Engaging processes; processes of engagement

Throughout the planning of the exhibition and the extended activities that informed its installation, we continually reflected on our own distinctive concerns as researchers as they related both to the work itself and to the curatorial process. As an art historian, Holt is focused on the possibilities of an eco-critical history of art practices and on a relational interconnectedness in our understanding of culture. In this regard and following the references above to the ‘archival turn’ and the collapsing of categories, there is context too in what have been termed ‘ecological turns’ (Ramos Citation2022) in contemporary art practice. To write or to practice ecologically also requires us to dismantle enduring, restrictive distinctions and hierarchies between aesthetic categories, genres, methods, materials and practices. Following eco-philosophy and new materialist writers such as Donna Haraway (Citation2003) Jane Bennett (Citation2010a) and Karen Barad (Citation2007) there is necessary emphasis on flat ontologies, on interconnections and entanglements (Patrizio Citation2019).

In the latter context Holt also has interests in visual-cultural responses to perceivably marginal or ‘at edge’ northern landscapes and environments, and in the implications of conceptual, as much as geographical borders and on acts of de-bordering (Citation2015). Here the notion of ‘border crossing’ prompts a rethinking of rooted notions of place and a focus instead on the permeable boundaries and entangled relations between nature and culture, the human and the more-than-human that together make, or produce, place. Something of this challenge to a rooted notion of place and fixed identities was manifest in Madge’s video installation, ‘Out of Place’, included in the exhibition, Borderlands (Citation2015) curated by the art historian and another curator, Mark Jackson.Footnote1 That installation included video footage of a figure in a bear suit filmed by the artist wandering forlornly around the now derelict RAF Winfield in the Scottish Borders. Winfield camp had served as a demobilisation base after the Second World War where Polish soldiers awaiting repatriation were housed along with their onetime army mascot, Wojtek, a cigarette-smoking Syrian brown bear. As noted, that installation was a reminder of the fluidity of borders, identities and the experience of mobility.

Madge’s entire practice and the ideas and concepts that informed it epitomise the generative possibilities of creatively crossing borders and defying boundaries and re-evaluating particular northern landscapes as neither marginal or remote, but as intrinsically interconnected and entangled with other sites, other geographies. The artist frequently worked at liminal places, often on shorelines where sea meets land bringing with it an endless tide of objects, litter, the residue of plants, animals, shells, rocks and so on. As Erika Balsom (Citation2020) puts it, and following Gloria Anzaldúa’s renowned study of borderlands, a shoreline is a border, a place of fluidity, ambiguity and instability. It is a site of arrivals and departures, an in-between realm of intermittent transformation and host to a high diversity of species that have found ways to survive together within the challenging flux of the ecosystem.

This sense of instability and transformation is also reflected in Hearn’s interest in archives and modes of archival re-presentation. His curatorial investigation of cultural repositories attends to the agency of archival materials and to how objects, images and ephemera are re-created, (re-)defined and performed through exhibition. Crucial to this position is an interest in the sense of return (Hao and Hearn Citation2010); a curiosity around how an artwork may be reconstituted or presents itself through a process of reverse-engineering elements of its documentary index. Julian Stallabrass (Citation2000) has argued that the archival researcher or curator’s role here is analogous to how the reader or viewer may themselves make sense of and receive a work’s meaning through the fountains of their own imagination. We might consider this potential gap in intent versus reception as a space of creativity in which the components of a work can be viewed or re-produced differently. Central to the curator’s archival and curatorial interests is an openness to this contingency, and with it the emergence of new forms of meaning.

Here the very stasis of Sally Madge’s archive offered the opportunity to engage not with a constituted institutional repository of ‘organised’ referents, but a collection of working-materials and miscellanea; an artist studio in flux, caught between activity and inactivity. Jenny Sjöholm (Citation2014) has proposed a likeness in form between the working artist studio and archive, both contexts shadowing, mirroring and waymarking ‘actants, remnants and traces of their working lives’. That proposition aptly relates to the circumstance of this particular artist’s studio in the basement of her house and her habit of collecting and storing apparently random objects and materials which would frequently be repurposed and ‘emerge’ in subsequent artworks or events, while still retaining traces or prompting memories of previous use, now of course manifest in the context of her archive.

Crucially, Sjöholm (Citation2014) reminds us of the dual status of the studio as a ‘space where things originate or are reinvented – it is a space where things begin’, or to where they return. Following this line of thinking, the meta project, interarchive has been a recurring source of interest. In this context von Bismark, Feldman, Obrist (Interarchive Citation2002) and others reflect on the intermedia state of the archive as raw material, considering dynamic memory and the archive’s broader associations with the specifics of recall, as well as its abilities to draw connections between the past and future conjunctions anew. Reflecting in-between states of order and disorder within the archive’s procedural make up, interarchive reminds us of the haptic function of objects, their capacity to produce multiple ‘truths’, and the archive’s continual state of reference to the present moment.

Without the artist present to navigate a way through the studio, we were initially guided by the first-hand knowledge of Tom Jennings, Sally’s long-term companion and, frequently, her in-the-wings collaborator. Tom had been there on site, had seen the work being made, had seen the work go out to exhibition and had seen it return to its studio-home, and Tom had packed the studio up in boxes and containers – the state in which we found it then. For our collaboration, however, we met the work on new terms and in new ways at this border of being, having been and of becoming. Mining the varying contents of the studio-archive, the objects amassed in the gallery both motion towards resolution and speak of their potential to be continually reconfigured. As art historian and curator we shared the artist’s border-crossing instincts in our particular concern to blur the boundaries between site, studio, archive and gallery.

Transitioning sites of meaning

In The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art, Martha Buskirk examines shifting signatures of authorship and fluctuating objecthood in a body of artworks from the late 70s onwards. Examining the conditions of production and mediation of art, she observes a set of circumstances in which the context of presentation increasingly informs the art subject: ‘Collecting, preservation, research, and display’ she notes have ceased to be processes enacted on works, and have been ‘transformed into processes that artists employ in their own production’ (Citation2005, 187). Those themes of collecting, preservation, research, and display underpinned our approaches to exhibition-making.

Whilst celebrating new artistic languages and forms of display, Buskirk also recognises the associative risk that objects, intentionally not determined as ‘art’ are regardless, accessioned, catalogued and labelled as artworks and viewed exclusively on those terms. If the curator or institution is susceptible to misreading and misappropriating content, Buchli and Lucas point out similar risks in the ‘double hermeneutic’ bind of research in which ‘we cannot study without changing the object of our study’ (Citation2001, 9–13). What they appear to allude to here is both the potential and the pitfalls of discursive practices and the relational dimensions of curating that transgress, border-cross and relocate objects, positions and sites of meaning.

Confronted by Madge’s studio-archive of artworks and ephemera we were addressing a mixture of quantities known and unknown. The abiding fascination for this artist was with indeterminate realms, with enlisting everyday, domestic, neglected, forgotten or otherwise abject materials as profoundly meaningful, and seeing arbitrary distinctions, disciplines and artificial limits as hugely detrimental to our imagination, to our inspiration. The art historian had a long-term connection with the artist and first-hand experience having visited particular past sites, installations and exhibitions (Holt Citation2013). The curator’s knowledge around the practice was more speculative and secondary source. As we collectively explored the remnants of a roster of past events, we were not excavating the archive for the unknown, but focused on the possibility that affiliate material can materialise anew, and as such, come to matter. This transitioning state of mattering, this sense of altered form and meaning we might describe as an assonance – much like the sense in which a couplet’s rhyme is inexact but nonetheless close in shape and structure, the archival shadow may itself return in ways resembling its past self, but with an apparent shift in meaning.

For both art historian and curator there was recognition of the importance of both being in the work and of imagining and speculating on what might be. In engaging in an ‘archaeology of now’, Buchli and Lucas argue that, relatively, we locate ourselves in the act of research ‘much more intimately than any historical approach’ (Citation2001, 9). For Holt, the act of revisiting work that was both intellectually familiar and physically tangible already inferred a degree of intimacy. For Hearn the intimacy of newly connecting with the work reflected Douglas Crimp’s (Citation1997, 204) interpretations of historical materialism, a position which amplifies the conditions of the moment, to find original engagement and encounters with events past, particular to the new, the present, the now. Sally Madge: Acts of Reclamation sought to explore material interconnectedness and the enduring possibilities of renewal. To this end we focussed in the exhibition on two strands we felt exemplified the nature of Madge’s practice and her longstanding preoccupations:

The first of these, Shelter (2001–14) a simple drystone hut (now destroyed) was constructed in two iterations on a relatively unvisited part of the tidal island of Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast, and represented in the exhibition through images, documents and related artefacts. It is a structure the art historian has written about in a different context elsewhere (2013). Shelter was built out of available rocks, debris and pieces of driftwood gathered from along the beach where it was located. Over time the structure drew the attention and much affection from passing walkers and returning visitors as well as several of those who live on the island. When the first structure was destroyed in 2010 by the nature reserve warden (supposedly for health and safety reasons) there was much support for the idea of rebuilding more securely, ultimately with the help of a renowned dry stone waller who offered his support. Footnote2In its last version Shelter lasted until 2015 when it was badly damaged by a troubled visitor, if unintentionally. () Its legacy survives in documentation on the artist’s websites (www.sallymadge.com and https://thesheltermuseum.net as mentioned later in this paper) in subsequent films and writings and in the recollections of so many who interacted with it over the years.

Figure 1. Sally Madge, Shelter on the north shore of Lindisfarne. Photo: Sally Madge, © Amy Madge and Lucy Madge.

A simple drystone hut (now destroyed) Shelter was constructed in two iterations on a relatively unvisited part of the tidal island of Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast, and represented in the exhibition through images, documents and related artefacts.

As we considered Shelter in the present we saw a work that was inclusive and truly participatory and collaborative, dissolving barriers between the artist (often defined in its accumulated ‘visitor books’ as ‘caretaker’) and the wayfarers who engaged with it as they passed by – leaving meaningful to them objects, sharing their own memories, or just engaging in playful creativity with materials related to that place – noting its characteristic sounds: the songs of seals, the cry of gulls, the smell of salt and seaweed, the endlessly shifting quality of the light, the joy, or otherwise, of the weather. To move in and around this site-specific work was to perpetually border-cross between nature and culture and between individual and collective experience. The evolving nature of the structure, as well as the kind of interactions it accrued over time correspond interestingly to the collaborative evolution of the exhibition itself and the discussions it generated in the process.

The second and connected body of work installed in the gallery was Scatter. This was a project Madge had been engaged with before she passed away and thus remained unfinished.Footnote3 In the form of wall and floor panels and eleven amorphously shaped cushions, these objects were covered with or constructed from fragments of fabric found washed up in the sand, rocks and rotting seaweed on beaches along shorelines in England, Wales, and Scotland. Over a period of years Madge had beachcombed slivers of fabric, orphaned garments and textile scraps, meticulously cleaning each of the elements before arranging and stitching them together into these new-form assemblages ().

Figure 2. Sally Madge, Scatter as displayed in Acts of Reclamation, © Amy Madge and Lucy Madge. Photo: Colin Davison.

Over a period of years Madge beachcombed slivers of fabric, orphaned garments and textile scraps meticulously cleaning each of the elements before arranging and stitching them together into new-form assemblages.

Scatter could be understood in relation to a number of artworks emanating from a recent UK cross-disciplinary research project, Tidal Cultures (https://tidalcultures.wordpress.com), exploring the cultural and natural elements of tidal landscapes – as, for example, in work by the artist Lydia Halcrow who considered the materiality and traces of the incoming and retreating tide of the Taw Estuary in Devon. Another connection lies in the work of artist Julia Barton. From the perspective of coastal pollution, Barton’s littoral: sci-art project engaged with the vast amount of litter washed up on the beaches of north-west Scotland and drew local communities into the consideration of its environmental impact. While important environmental issues underlie Scatter, its concerns appear to us both richer and more complex, again raising wider implications of the framing concept here of crossing borders and boundaries.

At a fundamental level we cannot know and can only imagine the contexts from which the everyday rags and remnants of material that constitute Scatter emerged; what entanglements with storms, waves and sea life did they endure on their journey that battered, shredded and faded them into the forms as found by the artist? Border-crossing as migration is an inevitable theme here. There is great resonance in the tragic and appalling circumstances of today – of fleeing conflict, with allusions to life threatening journeys in search of new possibilities but with those hopes so often dashed. Here associations might be drawn with images of humanity washed ashore, found floating in the water; or the experience of survivors facing hostile environments in hardened coastal borders with endless citizenship struggles and narratives of who, or what belongs where (Cowan Citation2021).

There is, therefore, a sense of movements, at all scales, of people and their traces, as well as wider historical questions of local and transnational diaspora. And, indeed, sustainability is another theme emerging from Scatter, resonant with the ‘global challenges’ of the present and the unequal extractive relations between the world’s north and south.

Sites of research

Of an artist’s studio and noting its characteristic sub-function as a place of storage, Jenny Sjöholm observes, ‘there is a limiting order imposed by the material collected that can potentially authorize and command the future development of artistic work’ (Citation2014, 507). Similarly, Hoffman proposes the dual agency of the studio as the material basis for new artworks, and ‘as an archive for ideas’ (Citation2012, 15). In regarding the studio as a site of preservation, and the archive as a context for production, and vice versa, we therefore open ourselves to the possibility that an object or artwork can simultaneously be both anchored to the context of its making and open to new and less obvious forms of re-presentation; inactive or in dormancy or re-active, indeed retroactive, and therefore in circulation or use.

Madge’s practice had strayed between desolate beaches and the inert cabinets of museums, in amongst the seagulls and the mechanism of the harbour port and quietly perched on the shelves of a museum. Our secondary encounter with Madge’s ‘studio-archive’ involved none of the theatre of meeting, no mise-en-scène setting or event. The collaboration began in that rented, padlocked 8 ft wide and 20 ft long storage container in an out of doors site on the outskirts of the city. Within, packed floor to ceiling in loosely designated zones were the known and largely unknown quantities of an artist’s working life.

Sketchpads had been counted and numbered; objects, artworks, ephemera had been boxed up anew or remained in the various containers in which they had been long-stored. There were portfolios, repurposed shoeboxes and plastic crates, bin bags and amorphous bubble wrapped forms – sarcophagi that offered no clue as to the object within. There was a box of knick-knacks, trinkets, an old thermos wrapped in newspaper that only after much puzzlement revealed itself as destined for the car boot sale rather than any creative purpose. All these packages were themselves contained atop, beneath, within, and on the shelves of various bits of furniture that had originally been the fixtures and fittings of the studio. There were tables, shelving units and other makeshift surfaces that had been elements of past exhibitions and were repurposed as structures to work on – often, as noted above, with the scars and traces of past use. Objects and associated places and sites of meaning were compressed, reduced and synthesised back into the storage capacities of the studio. In the absence of the artist herself to unpack this process of ‘self-archiving’ (von Bismarck Citation2002), to this mass of stuff a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet constituted an index, a skeleton table of contents, a map of loosely defined coordinates.

As another platform or key to the practice, Madge’s personal website remained an additional index to the work, bearing witness to past projects through different gazes and acts of recall. Within the genealogy of its overview, individual projects were recalled through an amalgamation of photographic documentation, drawings and other evidence of process, and through first-person narrative accounts combining intent and practicalities of iteration. While the website offered a catalogue or reference index for work, and a framework to think in, crucially our concern was not in re-enacting artworks or in re-creating past forms of display as ‘truthful’ representations of the work. Further to this Shelter had its own distinct website, The Shelter Museum (http://thesheltermuseum.net). This platform, self-decreed a ‘museum’, catalogued together documentary evidence of the ‘site’, ‘events’, ‘artworks’ (other artist’s projects produced in and around the shelter)’notebooks’ and ‘objects’. In respect of the research process the websites were a more productive tool for the curator than for the art historian, nonetheless as Richard Beardsworth reminds us, without such ‘memory support systems, there would be no experience of the past and nothing from which to “select” in order to invent the future’ (Citation1996, 151). This sense of selection, of working with the particulars of objects rather than merely the available provision is vital to the forms of contingent narrative we were looking to open up.

Objects for Madge were slippery; they passed back and forth between modes of operation – order in chaos – and the mystery and wonder with which she looked on the everyday was still present in the (dis)order. This being the case, the studio-archive as encountered in mid-summer 2021 was, out of necessity, packaged up in such a way as to suggest the presence of some semblance of order and logic. In looking at boxes of material and their seemingly systematic placement upon shelving units and cabinets, what was less clear was the system of organisation, and indeed who had registered the objects and other components into this state. In a purely practical sense, the capacities of the storage unit meant that whilst it was capable of housing the amassed material, neither the space nor the environmental conditions therein were ideal for unpacking or the necessary archaeology of the collected content. Having identified the projects to prioritise for exhibition, we found ourselves effectively impotent to conduct the necessary research – to bring the archive into use, to engage with its sense of functional memory and to partake ourselves of the necessary process of thinking in, with and through the material legacies. In the three weeks preceding the exhibition, we resolved therefore to turn the gallery into an expanded studio/workshop/laboratory – to bring the boxes, folios, sketchpads and various fixtures into the gallery and to work with them on-site.

Sites of presentation

In its current location, the university gallery operates as two distinct spaces, one museological which houses a collection of contemporary art and historical artifacts, the other Gallery North – for which the exhibition was planned. This space was formally a training salon for hairdressers and is foremost characterised by its blue, studded, rubber floor that runs throughout and drifts upwards to form a skirt around the entirety of the space, along with an ample supply of power points for hairdryers. Otherwise white-walled and glass fronted, the gallery is nonetheless coloured and codified by this workshop feel. In ways unspoken it is conditioned by its own sense of pedagogy – a space orientated for learning. The procedural approaches we adopted in making the exhibition, working through and workshopping ideas, appeared both practically and intellectually fitting in this context.

Initially as a purely practical means of unpacking and beginning to visualise the range of content, we set up trestle tables and other temporary tabletop structures (themselves remnants of Madge’s studio) as a platform to begin spreading out the contents of the archive. As we unwrapped objects and unearthed the collective contents of boxes, so aspects of the archive began to reveal interconnectivities and traces of the past; we began to find existing dependencies, and new and different orders began to reveal their potential. There was an opaque plastic box filled to its depths with heavy duty rubber gloves, fingers amputated and petrified from the ingress of salt water; a carrier bag of broken bounce less-balls, burst at the seam, bleached and brittle; a box of soleless, orphaned black leather shoes; a shoebox brimming with luminous plastic cuttlefish (lures), masses of knotted fishing tackle, painted stones and corroded metal tobacco tins, along with a miscellany of very many other items. Collectively these objects spoke to the act of beachcombing dispossessed relics from the wash, and each item carried with it the particular and unmistakable smell of the sea diffusing the gallery with a collective scent. Described as here, these collections of objects immediately reveal the sense in which they can simultaneously talk back to individual and collective forms of memory, how they can possess particular significance and at the same time matter universally.

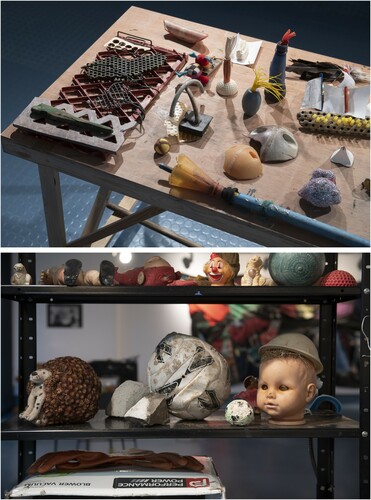

Even set or spread out in this initial state of pre-examination, the objects began to reveal traces of their past. () Consulting the Shelter Museum website for example, the boxed-up droves of specific items were visually catalogued through the ‘objects’ section of the ‘archive’. Here Madge delineated these ‘collections’ within taxonomies such as ‘balls’, ‘bones’, ‘shoes’, ‘tumbleweed’, and documented the grouped objects in gridded dispersions, as if recording the finds of her archaeological dig. The in-flux disorder of the objects in the gallery therefore echoed this active sense of fieldwork, like a hoard of unearthed objects being looked upon with new eyes and in the fresh light of the day. The speculative arrangement, laid out on horizontal plane also inferred the physical setup and thinking space environment of her studio.

Figure 3. Sally Madge: Acts of Reclamation (details), © Amy Madge and Lucy Madge, Photo: Colin Davison.

Madge delineated these ‘collections’ within taxonomies such as ‘balls’, ‘bones’, ‘shoes’, ‘tumbleweed’, and documented the grouped objects in gridded dispersions, as if recording the finds of her archaeological dig

At this juncture, a conversation with artist and educator Judy Thomas, also a close friend of Madge’s, led us to re-appraise, formalise and to recognise the unforeseen significance of these temporary structures. Thomas recalled a visit they made to Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 2019, and two interconnected displays linked to The National Arts Education Archives (NAEA) at YSPFootnote4:

here we had a long conversation about nature tables, imaginative play, and pedagogies of uncertainty; we reminisced about our respective primary school experiences and laughed at how we constantly recreate the nature table in our respective homes, gardens, and general practice.Footnote5

We continued and extended this process of excavation. We explored the array of objects laid out on tables or placed tentatively on structures, we talked through ideas and drafted thoughts, we unpicked our preconceptions, we looked for the not-knowns, we made decisions. Reconciling the conditions and cultures in which artwork is both displayed and received, Stephen Greenblatt explored this meeting and point of encounter under the term ‘resonance’. This he perceives as the dynamic (museum) object’s agency to convey meaning beyond ‘its formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex, dynamic, cultural forces from which it has emerged’. in essence to matter. For Greenblatt (Citation1991) resonance is the dialectical opposite to wonder – which is reserved for those exalted, nonpareil objects that alone possess the power to arrest. It holds therefore that resonance is more attuned to the precarity of objects, it is born of reference to objects that speak to destruction and absence as well as ‘unexpected survival’ (Greenblatt Citation1990). Extending this argument, it is the difference between those objects that most grab our attention, compared to objects that keep our focus and extend our interest – that offer up the greatest potential for redemption. These ideas are both referenced in the exhibition title, and in the processes of renewal of meaning explored within the re-curation of objects in the gallery.

Cabinets of curiosities and why there were no vitrines in the gallery

Wunderkammer in its direct translation from the German refers to a room or the place in which curiosities or objects of wonder assemble and are displayed. Its meaning then slowly drifted to reference the cabinet or other vehicle and the amassed display of authentic objects – in essence the personal and private museum. Across the twentieth century, and in contemporary art contexts this understanding has further diversified to signify the marriage of the mobile vessel and the juxtapositions of the array of contents stacked within. Implicit in this framing is the move away from ideas of possession to a position where the display, the encounter, the ‘resonance’ is paramount. What this shift also suggests is a move away from the riches of excess, of more is more, to a framework in which the cabinet is but a temporary custodian of both the objects and the contingencies of meaning their relative positioning might reveal; a container for disorder and unusual connections to manifest.

Libby Robin (Citation2018) recognises that wonder and things deemed curious are not shorthand for weird. In spite of the fact we live in strange and uncertain times she argues, curious relates to objects and entities ‘not yet fully understood’. This potential misreading of objects or othering of entities not understood speaks directly back to context and the imaginations of students in relation to the exhibition. To look at this another way, to not be fully understood is to challenge categories of association or systems of order, structures of organisation and intellectual recognition. Tokenistic, pluralistic, the world is filled with too much stuff – presently we either live in time when we are closest to or could not be more distanced from the circumstances which gave birth to Arte Povera. According to Robin it is precisely at these times – ‘when objects no longer come from strange place’ and are no longer able to surprise and surpass ‘because the world is well known’ – that we return to Wunderkammer. If this is true of our current epoch, when our value systems have collapsed, and everything but the rarest of minerals, data and cryptocurrencies is dispensable, then to concur with Robin, the function of the cabinet of curiosity is to ‘provoke thinking and re-thinking’ and to ‘play with curiosity itself’.

The sense in which we are aggressively confronted with stuff, how we make continuous active decisions about how we select, save or disregard things, how we process and ascribe value to one thing and show indifference to another is eloquently and sensitively scrutinised by William Davies King (Citation2008). His nuanced descriptions of the ‘keeper’ or ‘owner’ rather than the collector are in many ways befitting of Madge. Here, as is evoked in the ironic title, ‘Collections of Nothing’, King is leading us to think about the subjective value of objects beyond any rational economy; to consider the struggle for ‘individual identity and self-determination’ in social and political economies of the present. Drawing an analogy between collecting and art he reflects on the individual and collective ontologies of things; on wholeness and unity; containment and display, and on pleasure, beauty, power, truth.

When form, function, distinctiveness and value are all so precarious, the question becomes how does curiosity locate itself with the ecology of things? According to Jane Bennett, ‘thing-power’ recognises the insoluble essence that objects possess, the fact that objects are non-human players: they resonate they murmur; they emit and as such are actants. Bennett contends that the term ‘object’ attends to the identifiable, nameable paradigm, where status as a ‘thing’ is only conferred when we recognise the object looking and speaking back to us and we are therefore mindful of its being. Thing-power is thus the force of things: ‘It draws attention to an efficacy of objects in excess of human meanings, designs, or purposes they express or serve’ and in the pluralistic context of assemblage, as Bennett notes, the ‘agentic capacity’ is derived from ‘the vitality of the materials that constitute it’ (Citation2010a).

Greenblatt, Davies King, Robin and Bennett all affirm the self-determination, resonance and vibrancy of things, a pervasiveness of materialism that manifests both in singular presentation and together as ‘congressional agency’ (Bennett): a force to extract meaning from excess and to disrupt linear narratives. Whether the objects of attention are a dead rat, plastic glove, a bottle top, canned tuna fish labels, or the different patterns and signatures of envelope linings, these authors implicitly and explicitly underline values of pedagogy; what can be learnt by ‘not viewing but reading’ (Greenblatt). As Bennett (Citation2010b, 34) sets out in reference to Adorno, thing-power comes through learning to disrupt. Concepts, she argues, obfuscate our ability to view clearly, thus we need be more cognizant of a things’ vitality, to be more wilfully imaginative, to recognise and regenerate denied possibilities and, finally, she asserts we need to be playful thinkers – to be both unruly and unrealistic.

Tabling ideas

To show and to tell, as educational devices nature tables operate and function between positions of environment and ornament. They both attend to the essential phenomena of being of the world and assume certain decorative functions as modes of classroom display. They also disrupt or sidestep established systems of classification. The miscellanea that they corral can operate both without identifiable purpose and become operatives from which to learn and unlearn through handling. It was in these capacities that they were deployed within the gallery.

As stated earlier, some boxes from Madge’s archive had already defined contents; pre-established taxonomies for amassing these vestiges of the unknown such as shoes. Other containers revealed masses of seemingly disconnected whatnot in the sense these were things mostly recognisable, but they were equally unknown. Initially we unpacked and placed without purpose or intent an assembled mix of beach flotsam and jetsam upon the tables and shelves.

Amid the mass of debris patterns emerged. We walked objects about the space inviting dialogue and found conversations. Some of these interchanges emerged between recognisable configurations. There were for example aesthetic classifications based on colour or complimentary forms or distinctions such as natural or manufactured. But there were also those objects or combines that resonated or presented contradictions and demanded a rethinking beyond apparent human-significance. There were synthetic objects that appeared somehow organic; a hefty nugget of expanding foam presenting as pumice; a piece of driftwood, stopped with a crew of yellow Rawlplugs and a pencil and paper sail that oscillated between coastline kitsch and the curiosities of outsider art; (a) a hedgehog formed from a cuddly toy dog laden with a backpack of the burrs of Pirri-Pirri, an invasive pest plant species endemic to Lindisfarne since its accidental introduction in the early twentieth century – a thing of unequivocal ‘thing power’. (b)

Figure 4. (a and b) Sally Madge: Acts of Reclamation(details), © Amy Madge and Lucy Madge, Photo: Colin Davison.

Amid the mass of debris patterns emerged. We walked objects about the space inviting dialogue and found conversations.

In the two weeks prior to the show, objects moved and located and relocated themselves. This process echoed Madge’s long-term connection with these things; these often-indeterminable things, had for her, moved between objects of meaning and inactive collections of stuff. In drifting through the gallery, objects were carried between shelves and tables and caught in the eddies of the tide. We introduced accumulated Shelter visitor books, teasing out the variously humorous, prophetic and poignant messages left by visitors. Early on in the research we had uncovered a Polaroid photograph of the shelter that had been reinserted into the empty cassette which, unassuming as it was, captured the structure without monumentalising it. Latterly we uncovered some video shorts, captured using an old digital camera. In these un-edited vignetted moments, time stood still, the wind continued eternal to motor a plastic beach windmill, the phone circled to panorama the stone-hide. Again this footage circumnavigated the shelter without edifying it; it offered a representation for those who had not been there, a means to imagine the context from which all these things originated or were associated with.

Scattering, sketching and configuring meaning

Madge was a prolific sketcher; she journaled, drafted and drew continuously throughout her life. This legacy was captured in a collection of over one hundred sketchpads that varied in size from hardback volumes to ring-bound watercolour pads and small jotters. Many operated like scrapbooks, crammed with six-by-four photographic prints, traces of visits to galleries and other inserts. Spines broken and bursting, they may have been sacrilege to a bookbinder, but in the digital age they were affirmations and evidence of an increasingly rare compulsion to physically record, collate and synthesise ideas; fascinating and privileged spaces to be allowed to enter; objects she valued greatly. A few of the books were dated and sometimes indexed to a particular place or occasion; in one case a sketchpad was acquired to fulfil that afternoon’s compulsion to draw, and not used again. The vernacular of the sketchpads freely roamed from the traditional – portraits of family, watercolours and pastel drawings documenting a lifetime of hours spent roaming the coastlines of north Northumberland and elsewhere – to unreserved evidence of artistic free-play. These different voices and traits of Madge’s practice all coalesced and crossed and connected the margins of the different sketchpads.

Curatorially these windows into the artist’s practice were at once conceptually insightful and materially precarious, and thus could not be universally and continuously handled. While to cast a book open on a particular page was to support links and connections between other objects and ideas, we chose not to incarcerate these creative tomes behind glass and in cabinets. To do so too often fetishes and celebrates an artist’s sketchbook not as a of vestige of creative ideas, but as a collectible entity. Better to highlight their agentic capacity, to focus on processes, to highlight their agency and speak to curiosity itself. This decision was itself symptomatic of the broader discussions, of not feeling that the apparatus of the white cube or museum fitted the exhibition format. Again, the art school context, the teaching and literally being-in the studios presented an alternative solution. Temporarily appropriated from an undergraduate space, a work-a-day plan chest furnished a more suitable mode of display.

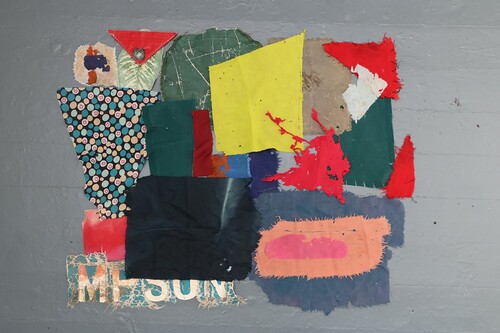

Plan chests are both agents of storage and structures designed for observation, and so using the horizonal plane of its drawers and top, we arranged the sketchpads to survey and look for emblematic themes and to table recurrent ideas. In one spread the notes underlying a series of photographs describes a process in which Madge painted reeds sprouting from sand dunes in bright colours, then harvested them and cut them into inch long batons before burying them in a circular pyre in the sand. This whole undertaking was instigated by her not knowing what to do that day, and yet it affirms a process in which from nothing, meaning is ascribed and re-found: a continuous curiosity. In other examples there were photographs in which Madge had arranged and re-arranged configurations of objects, there were abstract high colour oil pastel compositions and there were collaged landscapes and painted beach studies. () As mentioned earlier, the intent was to use the exhibition to explore this border-crossing instinct, and here the sketchpads intentionally spoke to that axis of site/studio/archive and gallery.

Figure 5. Sally Madge’s sketch books arranged in an appropriated plan chest, © Amy Madge and Lucy Madge, Photo: Colin Davison.

Plan chests are both agents of storage and structures designed for observation, and so using the horizonal plane of drawers and top, we arranged the sketchpads to survey and look for emblematic themes and to table recurrent ideas

As a project, Scatter was fittingly incomplete. Madge was still working through the project up to the time she passed away. () Scatter had seen, and moved beyond various possible incarnations, including at one point a geodesic dome, (another form of shelterFootnote6) in which the hemispherical structure was to be covered in a stitched together skin of these material fragments and tattered garments. Madge began and abandoned this process, unpicking the elements of the cloak before commencing on the current form. This process she did not however complete. In some cases patches of fabric were pinned in place, ready to be stitched, in others the forms were only partially assembled from the bag of scraps. Whilst the components themselves were incomplete, the sense of display, or the ways in which these objects would combine and interlace were even less developed.

Figure 6. Sally Madge: Acts of Reclamation, © Amy Madge and Lucy Madge, Photo: Colin Davison.

As a project, Scatter was fittingly incomplete. In some cases patches of fabric were pinned in place, ready to be stitched, in others the forms were only partially assembled from the bag of scraps.

In structure these abstract forms comprised two large tarpaulins, as yet undetermined as wall or floor pieces, and the eleven distinctly varied ‘cushions’. As fabric sheaths, infilled with padding, they were pillowy and filled out. Some took on the rectangular appearance of a cushion, others were elongated tubular forms, part bolster and part tentacle emerging from the deep sea. Collectively there were anthropomorphic associations between this family of forms. The use of fabric and upholstery of course reinforced their affinity with domestic furnishings, yet the surfaces themselves comprised swathes of colour and swatches of pattern and spoke another language: they were incredibly painterly.

As configured objects there was no blueprint, set of instructions or precedent for the presentation and display of the various compositional elements of Scatter. It was important that these contingent forms – assemblages bordering upon soft furnishings, painted structures and anthropomorphic limbs – were able to resonate between and across these identities. Again, the idea of a white plinth or any other more formal pedestal appeared both inappropriate and incongruous with the other display methods and the aforenoted gallery floor was too pervasive to offer any complimentary support to these structures. Whilst Scatter had come to settle in a series of forms and structures, the work spoke foremost of transitory states of being, and it is from these ideas of movement that we found our solution.

Having been temporarily resting the Scatter ‘cushions’ on box lids and other low-lying horizontal structures we were looking for something similar in scale and manner. From this position the idea of pallets emerged. Pallets speak or relate to a number of specific contexts: that of material goods moving around or being held in compounds awaiting transportation, but equally of allotments and other makeshift structures in which they are re-purposed and appointed new function. These analogies were appropriate and apposite to the work and the overall modes of display and in searching out these forms, we came upon a series of distinctive blue painted pallets on the university campus, which as a bridge between the dominant gallery floor and the objects of display met on equal and complimentary terms. Bringing these structures into the gallery and playing with different configurations and arrangements it was only latterly that we recognised a further layer of associate meaning. On top of the pallets, the vertical accent of the scatter cushions amplified their humanistic representation, they appeared like bodies on a raft, and that raft itself appeared to be surfing the wash of the blue gallery floor. ()

Conclusion

From the very beginning of our collaboration there were timely and audible political imperatives to be heard from the transgressive character of Madge’s work. Environmentalism of course sits at its core, and as discussed, the projects considered here speak directly of human waste, of left-over surplus washed up on beaches, and the core issues of value or lack thereof that is placed on material goods. Metaphorically in talking about care, value, cost and loss we are, as already noted, speaking directly to the ongoing migrant crisis. In the form that Scatter took within the gallery, however, the idea of lives lost at sea, of communities of refugees held in stasis or living by makeshift means and off the scraps of others became ever more apparent.

At the time of developing the exhibition, the looming Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) was dominating the news. Pledges and promises were being tabled and statisticians were crunching the numbers and rationalising the impact of different measures on the long-term prognosis. As the exhibition opened, the congress proceedings had begun in Glasgow and politicians, delegates and protestors were continuing to wrangle over frameworks, conventions and environmental impacts of policy or just doing nothing; all this taking place, somewhat ironically, under the banner of ‘Together for our Planet’. COP26, it is mostly agreed, delivered little consensus or enhanced understanding. By contrast, in Sally Madge’s practice, through care, compassion and imagination, the sense emerges of a potentially new, transformed existence to be achieved through overcoming and resisting borders and through collaboration and being- in- relation with human and more-than – human others. Understood as such, and through the interconnected axis of site/studio/archive and gallery, Madge’s work appears to us as boundary-defying, and defiant indeed, so giving powerful pause for thought and for a necessary re-imagining of place and forms of existence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ysanne Holt

Ysanne Holt is Professor in Art History in the Department of Arts at Northumbria University. She has longstanding interests in landscape and in imaginings and experience of the UK rural north, especially its islands and border regions as registered across forms of creative practice through the twentieth century to today. Recent publications include ‘Place on the Border and the LYC Museum and Art Gallery,’ in Tim Edensor, Ares Kalandides and Uma Kothari, eds., The Routledge Handbook on Place, Routledge, 2020 and Co-editor with David Martin Jones and Owain Jones, Visual Culture in the Northern UK Archipelago: Imagining Islands, Routledge 2018. She is currently completing a monograph on interrelations between artists and the material resources of the Anglo-Scottish borders. [email protected]

Matthew Hearn

Matthew Hearn is a curator and lectures in Fine Art at Northumbria University. In 2007/08 he worked with Interface, University of Ulster to develop and curate a programme of seminars and workshops, Performing the Archive and contributed to the resulting publication, Arkive City (2008). In 2009/10 he was ‘Writer in Residence’ for Sophia Yadong Hao’s project NOTES on a return. Supporting the research and development of the exhibition programme he developed a chapter, Forgetting to Remember: Remembering to Forget in the resulting publication which he co-edited. He has curated a series of large-scale painting exhibitions Riff/T (2013/14), unpainting / resurfacing (2015) and A Deceptive Cadence (2016). [email protected]

Notes

1 Borderlands presented works by artists engaged with issues of boundaries and border zones; with hard borders which circumscribe mobility and more symbolic regions such as the Anglo-Scottish border. Alongside Madge it included the artists Sandra Johnston, Laura Harrington, Mike Collier, Allan Hughes and photographer John Kippin.

2 And who also, coincidentally, wore the bear suit and played the role of Wojtek the bear in the installation mentioned earlier.

3 Parts of Scatter were subsequently completed by her close friends Sara Braithwaite and Paula Blair.

4 Transformations: Cloth and Clay, NAEA Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, 13 Jul–3 Nov 2019 https://ysp.org.uk/exhibitions/transformations-cloth-and-clay and Ruth Ewan & Oscar Murillo, Longside, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, 13 Jul–3 Nov 2019 https://ysp.org.uk/exhibitions/ruth-ewan-and-oscar-murillo.

5 E-mail to authors, 2/2/2022.

6 Aside from the shelter on Holy Island, this idea of home or a house also recurs in How Can I Tell What I Think Till I See What I Say? (2015) a project Madge developed for Customs House Gallery, South Shields.

References

- Balsom, Erica. 2020. ‘Shoreline Movements’ e-flux Journal, Issue #114 December 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/114/366065/shoreline-movements/.

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham, UC: Duke University Press.

- Beardsworth, Richard. 1996. Derrida & the Political. London/New York: Routledge.

- Bennett, Jane. 2010a. “The Force of Thing.” In Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, 1–19. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

- Bennett, Jane. 2010b. “The Agency of Assemblages.” In Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, 20–38. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

- Borderlands. 2015. Gallery North, University of Northumbria, 23 Apr 2015–08 May 2015.

- Buchi, Victor, and Gavin Lucas. 2001. “The Absent Present’.” In Archaeologies of Contemporary Past, edited by V. Buchli, and G. Lucas. London/New York: Routledge.

- Buskirk, Martha 2005. The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art, 186–198. Cambridge, MA/London: The MIT Press.

- Cowan, Leah. 2021. Border Nation: A Story of Migration. London: Pluto Press.

- Crimp, Douglas. 1997. On the Museum’s Ruins. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Davies King, William. 2008. Collections of Nothing. London/Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. 1990. “Resonance and Wonder.” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 43 (4): 11–34.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. 1991. “Resonance and Wonder.” In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, Smithsonian, edited by Ivan Karp. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northumbria/detail.action?docID = 5337767.

- Hao, Sophia Yadong, and Matthew Hearn2010. NOTES on a Return. Sunderland: Art Editions North.

- Haraway, Donna. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto, Dogs, People and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

- Hoffman, Jens. 2012. “The Artist’s Studio in an Expanded Field.” In The Studio: Documents of Contemporary Art, edited by Jens Hoffman, 12–17. London/Cambridge: Whitechapel Gallery & MIT Press.

- Holt, Ysanne. 2013. “A hut on Holy Island.” Visual Studies 12 (3): 218–227.

- Holt, Ysanne. 2015. “Performing the Anglo-Scottish Border: Cultural Landscapes, Heritage and Borderland Identities.” Journal of Borderland Studies 33 (1): 53–69.

- Interarchive: Archival Practices and Sites in the Contemporary Art Field. 2002. von Bismark, B., Feldman, H-P., Obrist, H., Stoller, D. and Wuggenig, U. (eds.) eds. Lüneburg/Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König.

- Patrizio, Andrew. 2019. The Ecological Eye; Assembling an Ecocritical Art History. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Ramos, Filipa. 2022. ‘Ecological Turns’ ART/AGENDA, January 25, 2022: https://www.art-agenda.com/criticism/444883/ecological-turns.

- Robin, Libby. 2018. “Anthropocene Cabinets of Curiosity: Objects of Change.” In Future Remains: A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene, edited by Gregg Mitman, Marco Armiero, and Robert S. Emmett, 205–218. London and Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Rogoff, Irit. 2008. ‘Turning’ e-flux journal, Issue #00. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/00/68470/turning/.

- Sally Madge: Acts of Reclamation. 2021. Gallery North, University of Northumbria.

- Sally Madge: http://www.sallymadge.com/work/shelter.html

- Sjöholm, Jenny. 2014. “The art Studio as Archive: Tracing the Geography of Artistic Potentiality, Progress and Production.” cultural Geographies 21 (3): 505–514. doi:10.1177/1474474012473060.

- Stallabrass, Julian. 2000. “Memories of Art Unseen.” In Locus Solus: Technology, Identity and Site in Contemporary Art, edited by Julian Stallabrass, and Duncan McCorquodale, 14–29. London: Black Dog Publishing.

- von Bismarck, Beatrice. 2002. “Artistic Self-Archiving: Processes and Spaces.” In Interarchive: Archival Practices and Sites in the Contemporary Art Field, edited by B. von Bismark, H.-P. Feldman, H. Obrist, D. Stoller, and U. Wuggenig, 456–460. Lüneburg/Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König.